#koestler art

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

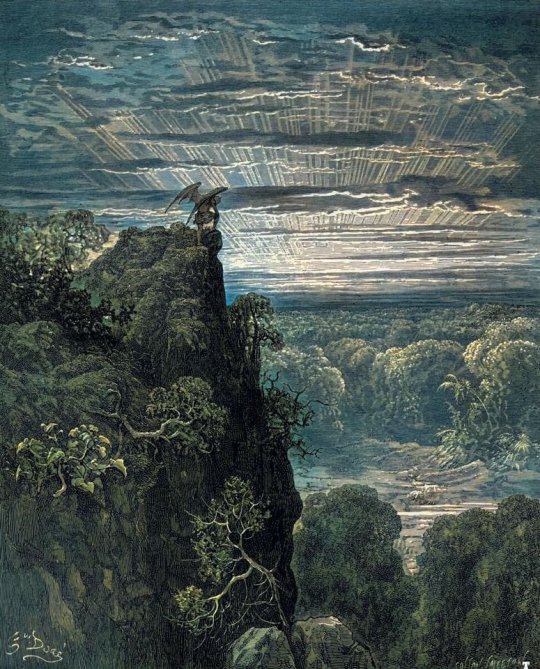

“Satan Overlooking Paradise” (1870) by Gustave Doré :: [Guillaume Gris]

* * * *

“Satan, on the contrary, is thin, ascetic and a fanatical devotee of logic. He reads Machiavelli, Ignatius of Loyola, Marx and Hegel; he is cold and unmerciful to mankind, out of a kind of mathematical mercifulness. He is damned always to do that which is most repugnant to him: to become a slaughterer, in order to abolish slaughtering, to sacrifice lambs so that no more lambs may be slaughtered, to whip people with knouts so that they may learn not to let themselves be whipped, to strip himself of every scruple in the name of a higher scrupulousness, and to challenge the hatred of mankind because of his love for it--an abstract and geometric love.” ― Arthur Koestler, Darkness at Noon

+

“It is wonderful how much time good people spend fighting the devil. If they would only expend the same amount of energy loving their fellow men, the devil would die in his own tracks of ennui.” ― Helen Keller, The Story of My Life

#Satan#gustave dore#Guillaume Gris#about art#quotes#Hellen Keller#Arthur Koestler#Darkness at Noon#The Story of My Life

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Invincible OC: 3/?

STATUS: Hero (active)

Ky Koestler, AKA Fifth Force

they're @sequids' oc!!

"Dear diary, today I've been thinking a lot about 'home'. What was the place I used to call home like? What kind of people lived there? It's frustrating not being able to remember, but I'll just have to trust the doctors and Agent Ferguson when they tell me I just need to be patient. I guess there is nothing I can do besides make a home of what I've got now. I think I can do it if I try hard enough."

#BABY BOY!! also all the kysmith art is so cute im higkey sobbing on how cute they are-#invincible#invincible oc#invincible fifth force#ky koestler#🧠💫#superhero oc#smmrdts: invncbl oc mdbrds

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

When I first read The Rebel, this splendid line came leaping from the page like a dolphin from a wave. I memorised it instantly, and from then on Camus was my man. I wanted to write like that, in a prose that sang like poetry. I wanted to look like him. I wanted to wear a Bogart-style trench coat with the collar turned up, have an untipped Gauloise dangling from my lower lip, and die romantically in a car crash. At the time, the crash had only just happened. The wheels of the wrecked Facel Vega were practically still spinning, and at Sydney University I knew exiled French students, spiritually scarred by service in Indochina, who had met Camus in Paris: one of them claimed to have shared a girl with him.

Later on, in London, I was able to arrange the trench coat and the Gauloise, although I decided to forgo the car crash until a more propitious moment. Much later, long after having realised that smoking French cigarettes was just an expensive way of inhaling nationalised industrial waste, I learned from Olivier Todd's excellent biography of Camus that the trench coat had been a gift from Arthur Koestler's wife and that the Bogart connection had been, as the academics say, no accident.

Camus had wanted to look like Bogart, and Mrs. Koestler knew where to get the kit. Camus was a bit of an actor - he though, in fact, that he was a lot of an actor, although his histrionic talent was the weakest item of his theatrical equipment - and, being a bit of an actor, he was preoccupied by questions of authenticity, as truly authentic people seldom are. But under the posturing agonies about authenticity there was something better than authentic: there was something genuine. He was genuinely poetic. Being that, he could apply two tests simultaneously to his own language: the test of expressiveness, and the test of truth to life. To put it another way, he couldn't not apply them.

- Clive James, Cultural Amnesia: Necessary Memories from History and the Arts

#james#clive james#quote#albert camus#camus#philosopher#french#the rebel#style icon#literature#smoking#trench coat

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

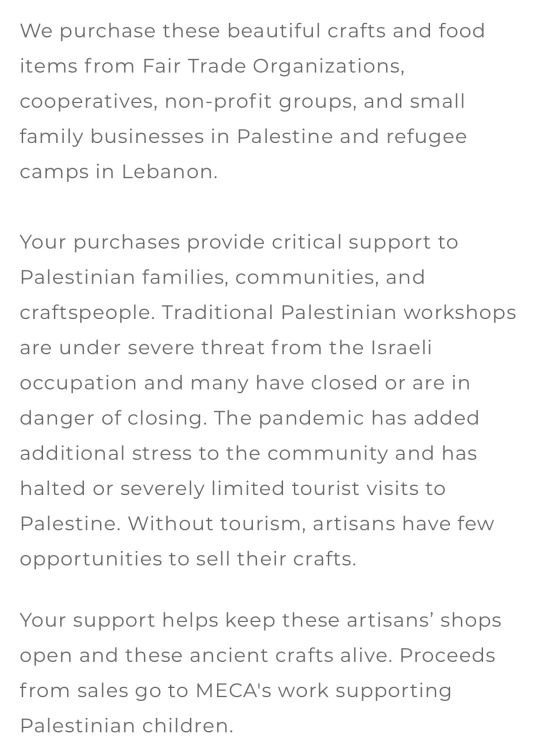

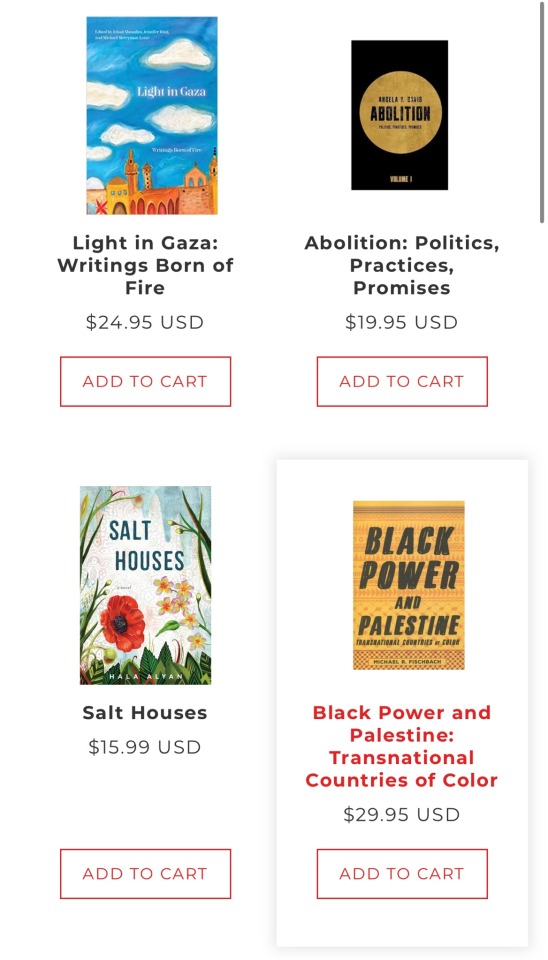

shoppalestine has a variety of items but I specifically wanted to highlight their books, and a few in particular.

Light in Gaza: Writings Born of Fire

Imagining the future of Gaza beyond the cruelties of occupation and Apartheid, Light in Gaza is a powerful contribution to understanding the Palestinian experience.

Light in Gaza is a seminal, moving and wide-ranging anthology of Palestinian writers and artists. It constitutes a collective effort to organize and center Palestinian voices in the ongoing struggle. As political discourse shifts toward futurism as a means of reimagining a better way of living, beyond the violence and limitations of colonialism, Light in Gaza is an urgent and powerful intervention into an important political moment.

Blood Orange

Blood Orange is a highly emotional, important and timely poetry collection by Mx. Yaffa (They/She), a trans Muslim displaced Indigenous Palestinian. Their writings probe the yearning for home, belonging, mental health, queerness, transness, and other dimensions of marginalization while nurturing dreams of utopia against the background of ongoing displacement and genocide of indigenous Palestinians.

On Zionist Literature

Interweaving his literary criticism of works by George Eliot, Arthur Koestler, and many others with a historical materialist narrative, Kanafani identifies the political intent and ideology of Zionist literature, demonstrating how the myths used to justify the Zionist-imperialist domination of Palestine first emerged and were repeatedly propagated in popular literary works in order to generate support for Zionism and shape the Western public's understanding of it.

A Child's View From Gaza: Palestinian Children's Art and the Fight Against Censorship

A Child's View from Gaza is a collection of drawings by children from the Gaza Strip, art that was censored by the Museum of Children's Art in Oakland, California. With beautiful, high-resolution print images of the exhibit, the book also features a special foreword by celebrated author, Alice Walker, as well as an essay by MECA Executive Director, Barbara Lubin, describing the struggle against the censorship.

Note: for obvious reasons, shipping can take over a month; in addition, they are currently unable to ship to the UK, and EU customers must spend at least €180; you may have to pay additional fees to get your package through customs.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Secret of Why the Dinosaurs Went Extinct

Prologue: It was the winter of 1993… [non-fiction]

Naturally, the K Literature Award was instituted for the commemoration of 'K's. The prize money is not much, but people all say that with the K Literary Award in hand, the Nobel is not far off.

Why K? Because K is the signpost of literary genius for our time: Kafka, Kawabata, Koestler, Kundera, Kureishi, Krasznahorkai, Kraus… The time of 'K' is Kommunistische Zeit, and the time of Kapital. Ke Xiangying is surnamed 柯, Kay E. He really was blessed by the ancestors.

In order to retrieve the award, Ke Xiangying had to cross the Atlantic Ocean, from the East Coast of the United States to Europe. After picking up the trophy (and not much prize money), the publishing house, anxious to sell books, did not let him go. Instead, he was taken on a grand tour of the developed capitalist nations of the West, giving readings, interviews, guest lectures, seminars. Paris was their last stop.

One afternoon after the signing, Ke Xiangying emerged from a bookstore rotating his sore wrists and saw that the streets from the Luxembourg Gardens to the Pantheon were packed with people.

"What's this about?" Ke Xiangying asked the on-site interpreter.

The interpreter hired by the bookstore was a young international student. He shook his head and said that it could be anything since people in France were always protesting. It was the French translator of Ke Xiangying's novel who answered in halting Mandarin: "These are workers from several state-owned enterprises opposing privatization reforms. The ones at the front, yes, under the red CGT balloons, those are railway workers. They're the most militant. How do you say this in Chinese again? '砸了铁饭碗' — smashing the iron rice bowl. I actually learned the phrase from Ke's book."

The young international student was quite shocked. "There are still state-owned enterprises in France?"

The French translator was also surprised. "Which country doesn't have nationalized industries? Water, electricity, the post, automotive manufacturing… Of course the state has to be the controlling shareholder."

"Then are you also opposed to privatization?"

The young French man laughed. "Well, take the SNCF, it was probably nationalized long before I was born."

Ke Xiangying stood at the door of the bookstore, and watched the people with red flags walking past in waves. He suddenly remembered when he was very young, Chinese people could still take to the streets in demonstrations, carrying Chairman Mao's portrait (he had never seen any with portraits of Lin Biao; Ke Xiangying was only one year old when the plane crashed in Öndörkhaan). During the National Day parade, there were floats, and the ones featuring ranks of the working class [brothers] were particularly eye-catching. It was beyond glorious, all the workers of The Big Four gallantly marching by.

When he was young, he had a boyfriend named Jiang Ming who was a worker. That's right, Ke Xiangying was a homosexual. This was expected. Why else would a jury give the award to someone from China? Just because his last name began with K? There must always be something else beyond the writing: being a sexual minority, of color, anti-Communist, a Commie-lover, anti-Unification, pro-Unification, a Croat, a Serb, a Jew, a Tutsi, a Native American … Third-World literature cannot avoid politics.

As a matter of fact, Ke Xiangying really didn't want to talk about all that. He always said in interviews, "I'm not a liberal. How can you discern ideology from a love story?" The academics in the Faculty of Arts just laughed and kept on writing their papers — "Although Ke refuses to acknowledge the political orientation of his novels, we see that in his writings, the authoritarian regime…" And if Ke Xiangying only had cock in mind when he picked up a pen? That was not their purview.

But the cock was not Jiang Ming's. He didn't dare recall it. Ke Xiangying pressed the Jiang Ming who was unlike anyone else in all of existence into the deepest little box in his heart. Even through the hard days of New York City when he only had the free Chinese church meals to eat, or when his manuscript was rejected by the 17th publisher, or when a Mexican gigolo robbed him of all his money, he didn't dare to take the lid off the box and think about Jiang Ming. He was afraid that his thoughts would make the memories fade, like sugar that melted away more and more with every lick.

Ke Xiangying knew that he had never loved anyone in his life the way he loved Jiang Ming. Only when he looked at Jiang Ming did his soul tickle as Plato said, become warm and moist, and grow the fine feathers that carried people into the sky. But now he no longer had wings, and he didn't dare try to remember Jiang Ming like it had been a previous life.

In this moment though, everything had to come rushing back in. He couldn't stop staring at the ranks of trade unionists in the demonstration. Some of them wore blue overalls. Some took off their shirts, revealing the slightly-tanned inverted triangles of their muscular bodies, just like Jiang Ming used to do. In the summer, he didn't bother wearing an undershirt, just walked around the house with his upper body bare. Ke Xiangying couldn't stand it anymore. He announced to the publisher with the self-righteous impulse prone to middle-aged men that he will return to China soon. The publisher nodded, as if to demonstrate his knowingness about the matter at hand — that of a triumphant return and all.

Ke Xiangying's brother, Ke Xianghai, drove to Beijing International Airport for the pick-up. In recent years, after a long period of estrangement, they had started contact each other more frequently again because Ke Xianghai's son was studying in the United States.

Sitting in the car, other than the grey-blue sky, Tianjin seemed very different from when he had left. Ke Xiangying made a sound of surprise when the car drove over the Hai River. He had never seen any of these skyscrapers and reconstructions of the foreign concessions that filled the night sky with light pollution. And the chimneys he was so familiar with, there was no trace left at all. Back then, the Tianjin Radio and Television Tower had not been built yet, and the tallest building in the city was that big chimney. Day and night, white smoke had floated out of it, like little white dragons bound for the high sky of the North China Plain, crossing en-route the Hai river, which had seemed much wider than it was now.

Having made an appearance at his brother's drinking party and fulfilled the role of hometown kid made good, Ke Xiangying could hardly wait to ask his brother to help him find and contact old friends.

Before going abroad, Ke Xiangying and Jiang Ming's family, or more precisely, his two sisters, were almost at each other's throats. And after Jiang Ming's family discovered Jiang Ming had unexpectedly titled the deed of his apartment to Ke Xiangying, he became the sworn enemy of the Jiang parents.

Now, with the passage of time, Ke Xiangying can even be in the inconceivable position of sitting in a cafe with Jiang Ming's little sister. Her name was Jiang Liang, and she was a senior engineer at the design institute. They sat there for about half an hour. Ke Xiangying had the distinct realization that as their conversation drew on, Jiang Liang's hatred for him was growing with every second. By the end, this middle-aged, middle class woman no longer cared to put up with the notion of respectable conduct. That rough and tumble childhood spent in the alleys of Tianjin was once again revived in her body. "You intellectuals…" she said. "I've figured it out now. You intellectuals are the most selfish and misanthropic people of all. It was my brother's curse to have met you. So jot this down: other people have the right to say whatever they want about my brother. But not you.

No one would be talking to him about Jiang Ming.

That night at home, Ke Xiangying tossed and turned, unable to fall asleep. Finally, he got up and turned on the computer. You all refuse to talk about him with me? Fine. I'll do it myself. He opened a new document, and the screen was as empty as the memories he now had. His fingers fell into the familiar shapes of typing on the keyboard.

"It was the winter of 1993…"

translated author's notes

[1] This work is named in honour of Antonia Pennacchi's debut novel "Mammut" or Mammoth. ["L’egemonia operaia? Ma per piacere… Siamo una classe estinta… Come il bisonte d’Europa. Come i mammut" — Workers' hegemony? Please… We are an extinct class… Like the buffalos of Europe, like the woolly mammoths.]

[2] The Big Four, or literally the "Four Heavens" refers to the four big enterprises in Tianjin that once 'built all of China' - the Tianjin tractor plant, the Tianjin heavy machinery plant, the Tianjin machinery plant, and the Tianjin engine plant.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books Read in 2023 - If you're curious about any of them, please ask! I love talking about books

Rebecca (Daphne du Maurier)

Introduction to American Deaf Culture (Holcomb)

The Colour of Magic (Pratchett)

The Autistic Trans Guide to Life

Luda (Morrison)

The Moon is a Harsh Mistress

Genderqueer: Voices From Beyond the Sexual Binary

The Mask of Benevolence: Disabling the Deaf Community

Between Two Worlds (Sinclair)

Under the Skin (Faber)

When Time Stopped: A Memoir of My Father’s War and What Remains

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

Portnoy’s Complaint

Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of An Disability Rights Activist (Judith Heumann)

Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality

This is Moscow Speaking (Arzhak/Yuli Markovich Daniel; tr by Stuart Hood, Harold Shukman, John Richardson)

The Call-Girls (Koestler)

The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For

Homintern

A Scanner Darkly

The Trauma of Caste (Soundararajan)

Shards of Honor (Bujold)

The Origin of Virtue

Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers

Dreadnought

Children of the Arbat (Rybakov; tr by Harold Shukman)

The Gay Metropolis: The Landmark History of Gay Life in America

Janissaries (Jerry Pournelle)

The Disability Studies Reader (Davis)

Fat Off, Fat On: A Big Bitch Manifesto

The Book of Dust: The Secret Commonwealth

Inseparable (de Beauvoir)

World’s End (T. Coraghessan Boyle)

American Melancholy (Joyce Carol Oates)

Transgender Children and Youth (Nealy)

Disgrace (Coetzee)

The Light Around the Body (Bly)

The Hangman’s Daughter (Pötzsch)

Encounters: Two Studies in the Sociology of Interaction (Goffman)

The Trouble with Tink (Thorpe)

Gender Advertisements (Goffman)

And the Band Played On

Fairy Dust and the Quest for the Egg

The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life

Old Norse Poems: The Most Important Non-Skaldic Verse Not Included in the Poetic Edda (tr. by Hollander)

Arts of the Possible: Essays and Conversations (Rich)

Ladies Almanack (Barnes)

Over the Hill (Copper)

Fairy Haven and the Quest for the Wand

The Poetic Edda (tr. by Bellows)

Paris Peasant (Aragon, tr. by Taylor)

Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration

Stigma (Goffman)

Rubyfruit Jungle

Fairies and the Quest for Never Land

Sight Unseen (Kleege)

The Homosexuality of Men and Women (Hirschfeld, tr. by Lombardi-Nash)

Bea Wolf

New Selected Stories (Thomas Mann, tr. by Searls)

Gay Bar (Jeremy Atherton Lin)

Patsy Walker, AKA Hellcat

Treatise on Style (Aragon, tr. by Waters)

Diana (Frederics)

The World I Live In (Keller)

Christopher and His Kind (Isherwood)

Put Out More Flags (Waugh)

Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man (Mann; tr. and introduced by Morris, Lilla, Rainey)

On Our Own (Judi Chamberlin)

All Boys Aren’t Blue

Artemis (Weir)

Goethe und die Demokratie

Dress Codes (Howey)

Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing

Forms of Talk (Goffman)

Sister Gin

The Decameron (Boccaccio; tr. by Musa and Bondanella)

Elric of Melniboné (Moorcock)

Paradiso (tr. by Hollander and Hollander)

My Mistress’ Eyes are Raven Black

Mademoiselle de Maupin (Gautier)

The Magic Mountain (Mann, tr. by Lowe-Porter)

Home to Harlem (McKay)

The Sailor on the Seas of Fate (Moorcock)

#books#books read in 2023#book reading#my reading list actually got longer this year#again#it's over 11 pages long#and some of the entries are just authors I want to check out

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Bernard Radfar, “CHICKEN GENIUS: Art of Toshi Sakamaki’s Yakitori Cuisine”, 2019.

Arthur Koestler, “The Act of Creation”, 1964 was the topic of an earlier blog blog. Here I present: Bernard Radfar, “CHICKEN GENIUS: Art of Toshi Sakamaki’s Yakitori Cuisine”, 2019. INTRODUCTION. Arthur Koestler, “The Act of Creation“, 1964 book is a study in creativity in humor, art and science, It lays out creativity in (the diagram BELOW) as a moment of three “interjections” (defined as…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Hard To Be a God by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky

Gautam Bhatia

"You shouldn't have come down from the sky." (p. 217)

In his introduction to Danilo Kis's A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, a collection of chilling stories about the individual's mental and moral degradation under Stalinism, Joseph Brodsky writes:

"By virtue of his place and time alone, Danilo Kis is able to avoid the faults of urgency which considerably marred the works of his listed and unlisted predecessors [such as Arthur Koestler]. Unlike them, he can afford to treat tragedy as a genre, and his art is more devastating than statistics." (A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, p. xi)

For Brodsky, it would seem, distance is essential in order to effectively sublimate tragedy into art—distance of time and of place, which provides the necessary creative sanctuary that a writer needs.

But for Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, who lived and worked in the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War, neither kind of distance could be possible. It was, instead, their choice of genre that allowed them the "ironic detachment" that Brodsky thought necessary to transform statistics into literature. In a series of novels, set in the "Noon Universe," the Strugatskys imagined a future in which the Marxist theory of history had been vindicated, a classless utopia established, and humans were now a space-faring species in a peaceful galaxy. By exploring the dysfunctions of that world, the Strugatskys were able to create a subversive literature that escaped the censor's knife.

One of the central novels in the Noon Universe is Hard To Be a God (1964), which for the last fifty years has only been available in a double translation—from Russian to English via German. This deficiency has finally been remedied. In April 2015, Gollancz brought out a new translation, by Olena Bormashenko, as part of their SF Masterworks Series. The translation features an afterword by Boris Strugatsky in which he writes that the original plan for Hard To Be a God was that of a "fun story in the spirit of The Three Musketeers" (p. 244). But in 1963, when the Soviet Writers' Union was caught up in a wave of puritan-nationalistic fervour, a backlash against the thaw of the Khrushchev years, the Strugatskys realized that "the time of 'light things,' the time of 'swords and cardinals' seemed to have passed . . . the adventure story had to, was obliged to, become a story about the fate of the intelligentsia, submerged in the twilight of the Middle Ages" (p. 244).

The fault of urgency. Brodsky would have raised his eyebrows. And indeed, the plot of Hard To Be a God suggests all the pitfalls of allegory. An unnamed planet in the Noon Universe has not yet progressed beyond the Middle Ages. Anton is one among fifty "operatives" sent by Earth to implant themselves into the society and culture of that world. The operatives are commanded to be non-interventionist gods; while they take the roles of nobles and barons in the various petty realms and kingdoms, they may only observe. Despite their ability to wield the powers of a civilisation a millennium ahead, they are forbidden from interfering with the natural progress of history. "Natural," that is, according to the "basis theory" (which, although never explicitly stated, is the Marxist materialist conception of history), which—as the book's characters repeat almost like a litany—postulates the inevitable progress from feudalism to monarchic absolutism, to capitalism, and ultimately, the communist utopia. The pain and violence of feudalism must be suffered by its inhabitants, in order to pave the necessary way to utopia. Any intervention, no matter how benevolent the aim, would be a disastrous disruption. "We're gods here, Anton, and we need to be wiser than the gods from the legends the locals have created in their image and likeness as best as they could" (p. 39).

But then Anton's realm gradually begins to descend into a seemingly unscripted orgy of violence, directed primarily against writers, artists, and historians; and when Don Reba, a leader with distinctly fascist tendencies draws ever closer to absolute power, Anton begins to feel the conflict between the postulates of the basis theory, and his own instincts to intervene as his conscience dictates. As each episode casts a further strain upon his ability to endure inaction, Anton begins to understand how hard it is to be a god.

Although Hard To Be a God was written four years before Soviet tanks rolled into Prague to "correct" the natural progression of history, the allegory is unmistakable. But perhaps what saves the novel from remaining just that is that the parallels are not limited to one historical situation. Within the genre, the theme itself is a familiar one (although the Strugatskys probably got to it first). As Ken Macleod points out in his Introduction, the Noon Universe "anticipates Star Trek and Iain M. Banks' Culture novels" (p. vi). And the way the Strugatskys write, the book could just as well be a wry take on contemporary debates around humanitarian intervention and the responsibility to protect, or a critique of colonialism's "civilizing mission." Like Coetzee's Waiting for the Barbarians, it could be located in any time, any place, and in the history of any culture. And because it could be everything and nothing, it becomes easier to read Hard To Be a God as a good science fiction yarn than an unsubtle critique of Soviet hubris.

Stalinist totalitarianism's sacrifice of individual freedom and autonomy to the iron constraints of the march towards an illusory utopia has served as the political backdrop for a number of science-fiction novels—from Yevgeny Zamyatin's We, written in the earliest years of the Soviet Union, to Orwell's 1984. What is unique about the setting of Hard To Be a God is that the internal destruction of individual freedom under Stalinism is transformed into an external set of constraints that are ultimately as morally destructive. Every time Anton is driven to act by a particularly egregious instance of violence, the "basis theory" stays his hand, causing ever-deepening crises of conscience. "I don't like that we've tied our hands and feet with the very formulation of the problem," he protests to his superior, at one stage. "I don't like that it's called the Problem of Nonviolent Impact. Because under my conditions, that means a scientifically justified inaction. I'm aware of all your objections!" (p. 37) Alexander Vasielivich's answer is simple: "Don't abuse terminology, Anton! Terminological confusion brings about dangerous consequences" (p. 40).

The primacy of terminology, the unwavering belief that history is—literally—universal, and that local situations must be interpreted to distortion, as long as they can fit within an a priori vision of historical progress, "developed in quiet offices and laboratories" (p. 45), immobilises Anton in another way: by cauterizing his very human tendencies towards moral judgment and the attribution of responsibility. In Broken April, the Albanian novelist Ismail Kadare describes the tribal law of the blood feud, the Kanun, thus: "Like all great things, the Kanun is beyond good and evil" (Broken April, p. 73). Broken April is a story about how the impersonal, amoral Kanun, which prescribes an endless cycle of revenge and counter-revenge for a crime committed time out of mind, absolves the characters of the burdens of choice, and the burdens of judging and being judged for those choices. But in Hard To Be a God, while the inevitability of the basis theory absolves Don Reba and his marauding soldiers of culpability, it casts an even more excruciating burden of choice upon Anton. "Grit your teeth," he tells himself, "and remember that you're a god in disguise, they know not what they do, almost none of them are to blame, and therefore you must be patient and tolerant" (p. 45). He is not convinced by that excuse, and neither are we.

The hubris of attempting to subject an aggregate of unpredictable, individual human actions into an iron law of historic inevitability is not new to science fiction. In Asimov's Foundation series, the scientist Hari Seldon invents the science of "psychohistory," which is predicated upon the assumption that group behaviour is as predictable and as exact as a "science." Of course, science is never predictable; and psychohistory meets (at least a temporary) failure in the shape of "The Mule," a mutant whose powers range beyond what Seldon could have imagined. When it comes to human beings, Asimov seems to be telling us, no law of necessity can ever truly account for individual variation. In a strikingly similar thought, Anton observes that "basis theory only concretely specifies the psychological motivations of the principal personality types, but there are in fact as many types as there are people; any sort of person could come to power" (p. 85). As his colleagues try—in increasingly strained ways—to fit Don Reba into a mould, into "the ranks of Richelieu, Necker, Tokugawa Ieyasu and Monck" (p. 220), Anton's suspicion grows that Reba's "psychological motivations" simply fall outside the scope of the theory. And if that is true, and as an apocalypse seems to be drawing even closer while Earth's operatives continue to theorise and temporise, will the theory's mandate of non-interference continue to hold?

As with other Strugatsky novels, that question is not answered until the very end of the book. The issue remains poised on the edge of a needle, and when we put the book down, it is simply impossible to judge which way it ought to have been decided. Like all the best science fiction, Hard To Be a God asks the most discomforting of questions, and denies us the comfort of a resolution.

1 note

·

View note

Text

MANUAL FOR SUPERIOR MEN by karen kellock (Author)

A new theory in social psychology: the tyranny of groups vs. the individual in unique presentation. Collective insanity, the contagion of lunacy. What does it take to be a champion standing out in a sea of sharks? That is the essence of the writings of Karen Kellock. Koestler [1962] has noted the blending of art and science marks all discoveries. “She is a maestro with words, all about the herds.” Mansell Pattison, Postdoctoral Chair, UCI School of Medicine. Cover design by Karen Kellock, inner page by Blaze Goldburst.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Centre for Poetry and Poetics presents: Angelina D'Roza, Gareth Gavin and Helen Mort. All warmly welcome.

28th of Feb, The Diamond, LT2, 6.30pm.

Angelina D'Roza lives in Sheffield. She was a writing mentor with the Koestler Trust and writer in residence at Bank Street Arts, collaborating with artists, writers, photographers. Most recently her work appears in Blackbox Manifold and Shearsman Press. Her debut collection Envies the Birds was published by Longbarrow Press in 2016. The Blue Hour is Angelina's new collection and was released by Longbarrow at the end of 2023.

H. Gareth Gavin is the author of Never Was: A Novel Without A World (Cipher Press, 2023), which has been shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize, and of Midland (Penned in the Margins, 2014), which was shortlisted for the Gordon Burn Prize. His short story, 'Home Death', was longlisted for the Galley Beggar Press Short Story Prize. He is also interested in writing that moves between the creative and the critical, has written a monograph on free indirect style, and currently teaches a course on trans studies. He was born in Birmingham and lives in Manchester, where he works in the Centre for New Writing at the University of Manchester.

Helen Mort was born in Sheffield and grew up in Chesterfield. She is the author of three poetry collections with Chatto & Windus. Her most recent, ‘The Illustrated Woman’ was shortlisted for the Forward Prize in 2022. She has also published a novel and a non-fiction book ‘A Line Above The Sky’ about motherhood and mountaineering. She is a Professor of Creative Writing at Manchester Metropolitan and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

The readings will be followed by some social mingling time with the writers, an opportunity to talk to the three poets, buy books - Longbarrow Press with have a small book stall, ask questions and so on....

Event Link

https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/.../centre-for-poetry-and...

Recordings available now:

Part 1

youtube

Part 2

youtube

0 notes

Text

Books read in 2023

All the books I read in 2023, with a ⭐️ next to my favourites. You can also check my lists for 2020, 2021 and 2022.

Fiction

Red Star - Alexander Bogdanov Cryptonomicon - Neal Stephenson Ghostwritten - David Mitchell ⭐️ Keep the Aspidistra Flying - George Orwell A Psalm for the Wild-Built - Becky Chambers Darkness at Noon - Arthur Koestler ⭐️ Utopia - Thomas More & Ursula K. Le Guin Make Room! Make Room! - Harry Harrison The Terraformers - Annalee Newitz The Handmaid's Tale - Margaret Atwood Radicalized - Cory Doctorow Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow - Gabrielle Zevin A Canticle for Leibowitz - Walter M. Miller Jr. The Shadow of the Wind - Carlos Ruiz Zafón

Non-fiction

Gentrification Is Inevitable and Other Lies - Leslie Kern Uses of Disorder - Richard Sennett Radical Cities - Justin McGuirkn ⭐️ Moods of Future Joys - Alastair Humphreys Microadventures - Alastair Humphreys The Autonomous City - Alex Vasudevan ⭐️ Mindful Thoughts for Cyclists - Nick Moore Mismatch - Kat Holmes La anarquía explicada a los niños - José Antonio Emmanuel Company of One - Paul Jarvis Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Anarchy - Simon Read Something Should Be Done - Peter Good Ur-Fascism - Umberto Eco ⭐️ Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook - Mark Bray Bicycle Diaries - David Byrne Journey to Portugal - José Saramago Art for UBI - Institute of Radical Imagination La trinchera doméstica - Cristina Barrial Anarchy Works - Peter Gelderloos The Utopia of Rules - David Graeber FIRE - Dama de Ouros The Beach Machine - Kyklàda Machines Will Make Better Choices Than Humans - Douglas Coupland Off the Map - Alastair Bonnet Pirate Enlightenment - David Graeber

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: PAPAYA ART GREETING CARD- CREATIVITY.

0 notes

Text

Art Unleashed: A Winter Wonderland of Creativity Across London!

Experience the extraordinary this winter as London transforms into a canvas of creativity. From incarcerated imaginations to the boundless visions of iconic artists, immerse yourself in a world where art knows no boundaries. Here's your guide to the must-see exhibitions that promise to captivate, inspire, and transport you into realms of imagination and innovation. Koestler Arts: In Case of Emergency Embark on a journey through the artistic expressions of individuals within the criminal justice system. This annual exhibition by Koestler Arts at the Royal Festival Hall features over 8,000 artworks from prisons and young offenders’ institutions. Curated by poet Joelle Taylor, the showcase unveils the imagination and talents of those often overlooked by traditional galleries. When: 2 November - 17 December 2023 Where: Royal Festival Hall For more information: https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk David Hockney: Drawing from Life" and "Taylor Wessing Photo Portrait Prize 2023 Experience the resurgence of David Hockney's exceptional exhibition, "Drawing from Life," alongside the annual Taylor Wessing Photo Portrait Prize. From simple sketches to large-scale paintings, Hockney captures the personalities of his subjects. The National Portrait Gallery offers a captivating blend of Hockney's artistry and contemporary portrait photography. When: 2 November 2023 - 21 January 2024 (Hockney) | 9 November 2023 - 25 February 2024 (Photo Portrait Prize) Where: National Portrait Gallery For more information: https://www.npg.org.uk Blavatnik Galleries: Art & War Delve into the relationship between art and conflict at the Imperial War Museum's newly unveiled Blavatnik Galleries. Featuring over 500 works created from 1914 to today, the collection includes contributions from past greats like Henry Moore to contemporary artists like Steve McQueen. This impressive display is a testament to the diverse ways artists respond to and interpret war. When: Opens from 10 November 2023 Where: Imperial War Museum London For more information: https://www.iwm.org.uk/ Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Boundless Explore the artistic odyssey of Christo and Jeanne-Claude through monumental works at Saatchi Gallery's "Boundless" exhibition. Simultaneously, witness figurative masterpieces by Andrew Salgado in "Tomorrow I'll be Perfect" and a compelling collection by 29 female sculptors in "If Not Now, When?" It's a wrap of creativity at Saatchi Gallery! When: 15 November 2023 - 22 January 2024 (Christo and Jeanne-Claude) | 16 November 2023 - 7 January 2024 (Andrew Salgado) | 15 November 2023 - 22 January 2024 (If Not Now, When?) Where: Saatchi Gallery For more information: https://www.saatchigallery.com Tim Lewis: The Forest Visits Immerse yourself in the whimsical world of kinetic sculptures by Tim Lewis at Flowers Gallery. Using discarded objects, Lewis creates mechanical creatures that move in humorous and eerie ways. From an echidna made of Christmas trees to a lemur-like creature with a skeletal head, Lewis's creations are delightfully uncanny. When: 30 November 2023 - 6 January 2024 Where: Flowers Gallery, Cork Street For more information: https://www.flowersgallery.com Read the full article

0 notes

Quote

The term “the ghost in the machine”, popularized by Arthur Koestler (1967), originally referred to the cartesian body/mind dualism. However, the term has since taken on new meaning, referring to the agency, “black box” quality, and impenetrable inner workings of new technologies. With the advent of technology with the capability to remake 1930ies Berlin with unparalleled fidelity, create complex fantasy worlds and populate them, compose new pieces of music, or replace actors with avatars, the term is more relevant than ever. The opportunities provided by these technologies raise a plethora of ethical, artistic and philosophical dilemmas, relating to the nature and core of art, reality and originality. Whether by the use, non-use or misuse of technology, artists today must make a choice on the interrelation of art and technology, as they aim to challenge our perceptions and expand our understanding. New and emerging technologies represent a reservoir of possibilities and opportunities, but they also embody a Pandora’s box of deepfakes and reality distortion and are perceived by many as a threat to human artistic creativity. Together with ethical issues, technology also influences traditional aesthetics and raises both artistic and philosophical questions - e.g., what is art, reality, and originality? Do all arts/artists embrace/respond positively towards technology, and if not why? Where is the line between new technologies as gimmicks and their artistic application?

Call for Contributions AR@K24: The Artist, The Ghost, and The Machine | Kristiania

0 notes

Text

The AM: October 30, 2023

It's the post-Funding Drive, pre-Halloween episode of the AM—a mix of a deep breath of recovery, and scattered spookiness building to an hour of Halloween-themed goodies.

Thanks again to everyone who helped CJSW reach its $200,000 goal last week, and here's to another year of offbeat sounds and independent culture at 90.9FM.

Listen on Soundcloud

Stream from CJSW

Spotify playlist

Hour One

Friends Joseph Shabason • Welcome To Hell

Death Markus Floats • Fourth Album

Data Driven Pidgins • Refrains of the Day, Volume 1

Terms of Desertion Michael Peter Olsen • Narrative Of A Nervous System

Orion Bridge Lunar Lemur • Sifting Stars

Pwintiques Land of Talk • Performances

Midi Sans Frontieres (Avec Batterie) Squarepusher • Lamental EP

Head Down Rooster37 • In Deep Water

If You Could Be Doing Anything Contagious Yawns • Intramental

A Barely Lit Path Oneohtrix Point Never • Again

Hour Two

Blue Loving • Single

Reflections of Now Tommy Guerrero • Amber of Memory

Open Yourself SHEBAD • show us it's real EP

Koestler Ivan the Tolerable • Under Magnetic Mountain

Like Coconut Water BALTHVS • Single

The Shame Holy Hive, featuring El Michels Affair, Fleet Foxes • Big Crown Vaults Vol.3 – Holy Hive

Ghost Flyers in the Sky Jenny Omnichord • Cities of Gifts and Ghosts

Skeletal Love Song Jenny Omnichord • Cities of Gifts and Ghosts

Raven Fades Various Artists, featuring Dark Time • Palomino Smokehouse: Smokeout #7

Humdinger The Space Lady • The Space Lady's Greatest Hits

Hula Girl on a Tropical Beach Orange Crate Art • Cinema Exotica: The Imaginary Films of Ryan Simpson (Original Soundtrack)

The Sky Was All Diseased Black Market Karma, Tess Parks • Friends in Noise

In the Dark MISZCZYK, featuring Lætitia Sadier • Thyrsis of Etna

Hour Three (Halloween Special)

Dracula Cha Cha Bruno Martino • Single

The Seventh Seal Scott Walker • Scott Four

Bury Me Deep Chance Halliday • Single

Dracula’s Daughter Screaming Lord Sutch • Screaming Lord Sutch & The Savages

Come With Me to Transylvania Zacherley • Spook Along with Zacherley

The Boogie Man Todd Rollins & His Orchestra • Single

Dr. Lovecraft's Asylum Serpent Power • Serpent Power

Monster Chad VanGaalen • Shrink Dust

Necronomania The Vampire Sound Inc. • Vampyros Lesbos OST

Children of the New Dawn Jóhann Jóhannson • Mandy OST

Häxsabbaten The Garrys • Häxan

Witch's Game Cool Ghouls • Cool Ghouls

0 notes