#karuk indians

Text

Indigenous People's Day

DR. HENRIETTA MANN

Cheyenne

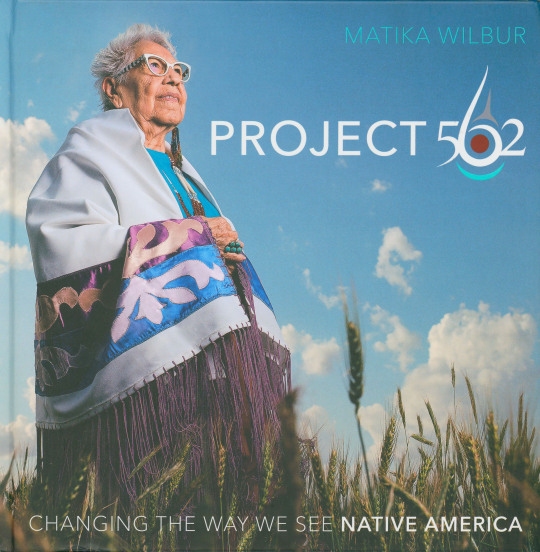

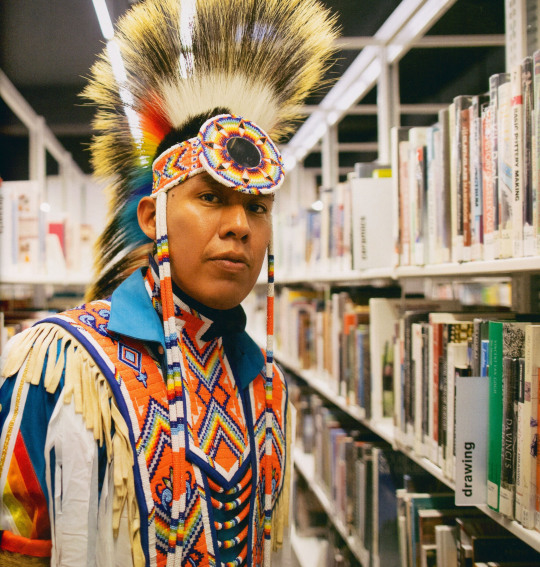

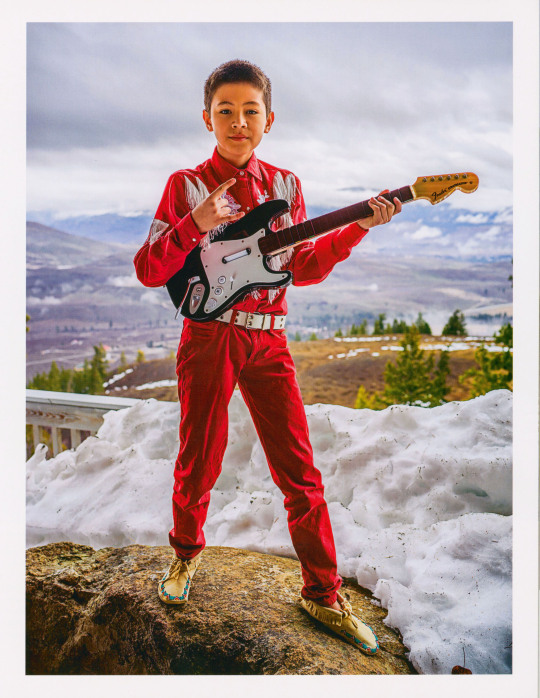

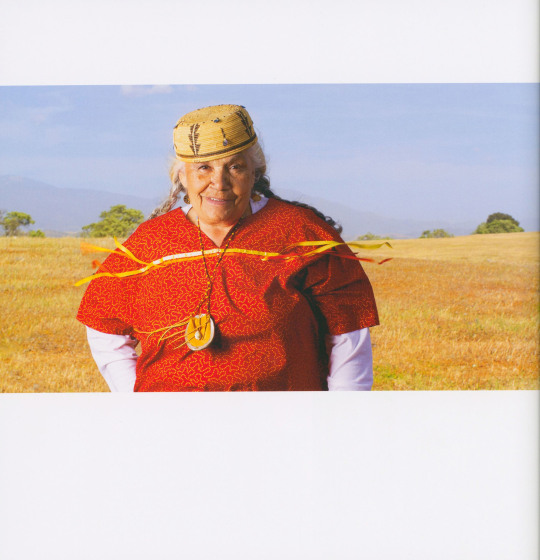

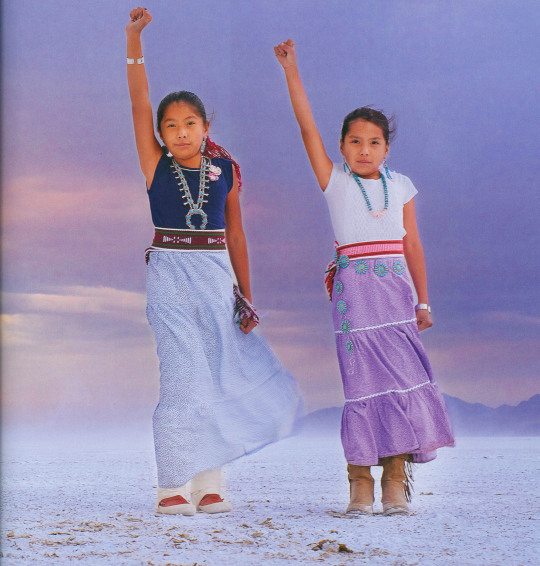

On this Indigenous People’s Day, we are featuring Matika Wilbur’s recent publication Project 562: Changing the Way We See Native America, published by Ten Speed Press in 2023. Wilbur (b. 1984) is a visual storyteller and member of the Swinomish and Tulalip peoples of coastal Washington. She holds a degree from the Brooks Institute of Photography alongside a teaching certificate that has shaped her style of educating through narrative portraits.

Project 562: Changing the Way We See Native America, a book born from a documentary project of the same name, resolves to share contemporary Native issues and culture. In 2012 Wilbur set out from Seattle to visit and photograph all 562 plus Native American sovereign territories in the United States.

Wilbur’s engagement with the communities she visited resulted in the creation of hundreds of dynamic portraits and documentation of conversations about “tribal sovereignty, self-determination, wellness, recovery from historical trauma, decolonization of the mind, and revitalization of culture.” She refers to her portraiture approach as “an indigenous photography method” that includes several hours and sometimes days of interaction with the participants, an exchange of energy and gifts, and asking sitters to choose their portrait location. The outcome is a stunning collection of Native narratives and portraits.

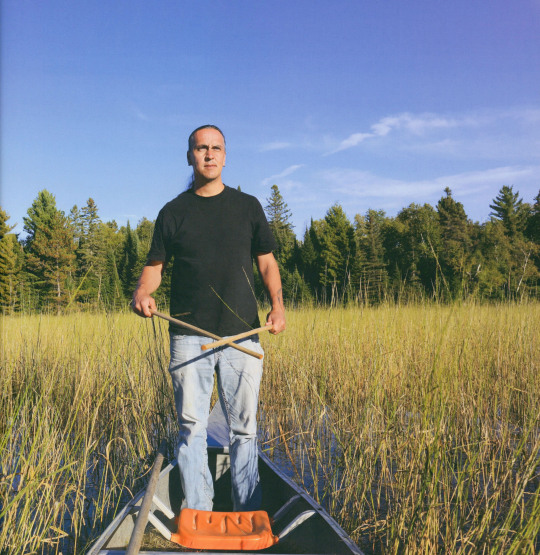

GREG BISKAKONE JOHNSON

Lac Du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians

HOLLY MITITQUQ NORDLUM

Iñupiaq

J. MIKO THOMAS

Chickasaw Nation

MOIRA REDCORN

Osage, Caddo

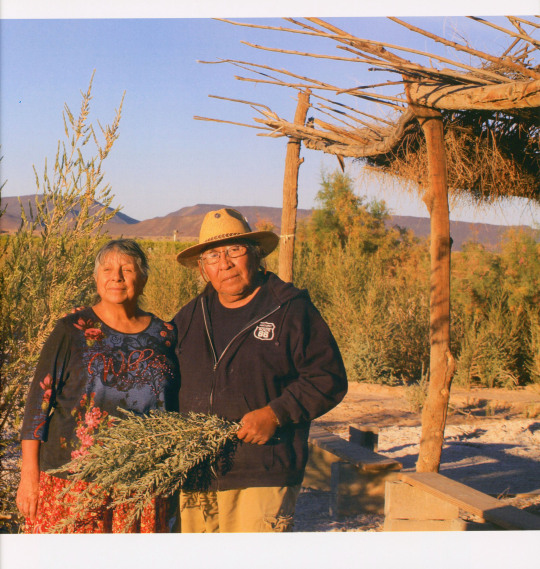

HELENA and PRESTON ARROW-WEED

Taos Pueblo/Kwaatsaan, Kamia

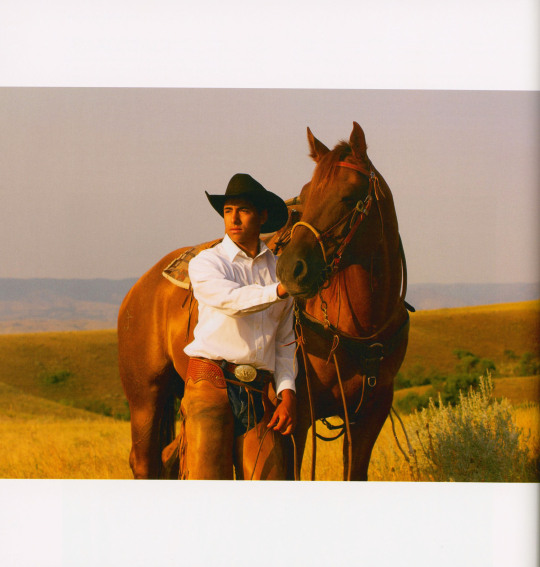

STEPHEN YELLOWTAIL

Apsáalooke (Crow Nation)

LEI'OHU and LA'AKEA CHUN

Kānaka Maoli

ORLANDO BEGAY

Diné

KALE NISSEN

Colville Tribes

GRACE ROMERO PACHECO

Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians

ISABELLA and ALYSSA KLAIN

Diné

NANCY WILBUR

Swinomish

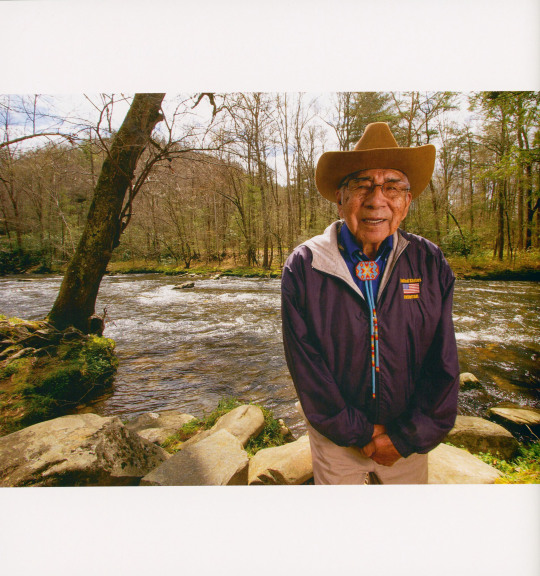

DR. JEREMIAH "JERRY" WOLFE

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

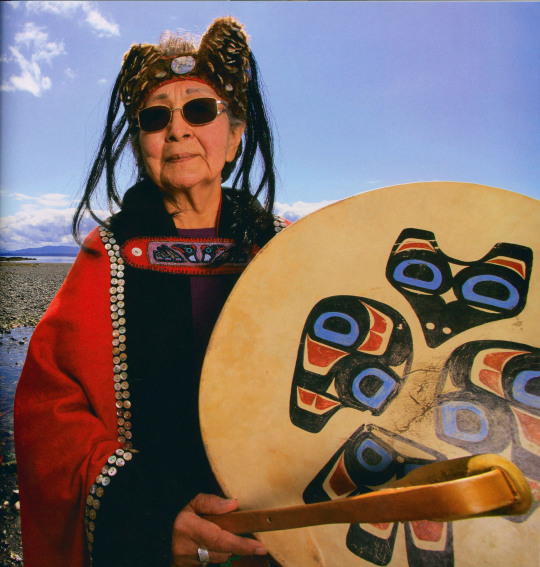

RUTH DEMMERT

Tlingit

MARVA SII~XUUTESNA JONES

Tolowa Dee-Ni' Nation, Yurok, Karuk, Wintu

Matika Wilbur will be speaking on UW-Milwaukee's campus Thursday, November 16 from 6-7p.m. in conjunction with her exhibition Seeds of Culture: The Portraits and Voices of Native American Women on view at the Union Art Gallery November 16 through December 15, 2023.

-Jenna, Special Collections Graduate Intern

We acknowledge that in Milwaukee we live and work on traditional Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, and Menominee homelands along the southwest shores of Michigami, part of North America’s largest system of freshwater lakes, where the Milwaukee, Menominee, and Kinnickinnic rivers meet and the people of Wisconsin’s sovereign Anishinaabe, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Oneida, and Mohican nations remain present.

#indigenous people's day#matika wilbur#project 562#Ten Speed Press#Native Americans#holidays#UWM Native American Literature Collecton

831 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just keep thinking about how it can actually be incredibly fucking hard to try to do research on your Indigenous family if you're trying to reconnect. When it came to my Métis side, because there's no recognition in any formal sense down here in the states, I didn't really know what anything meant at the beginning. I could see the names of Red River families and then find a map of St Vital where my family lived but then also made some rookie mistakes in thinking everyone on that side was Métis. A lot of the names on there are just French. When I found that out, I stopped saying my Métis names were Larance AND Nadeau because my specific Nadeau ancestor--despite being buried in Teton County Metis Cemetery--is just French. Not hard. There's a wealth of research still available but a lot of documents are in French and I don't understand.

I could go onto groups and be like "Hey this is my family" and they go "Yes, those are Métis people and you are Métis" and is that what it is to be claimed? Do I have to send my research to ST. Boniface to confirm? Do I have to get a card from MMF? Where does reclamation begin and end?

On my Yurok side it has been extremely challenging. There's no paper documentation prior to 1848/1849. The first state census was in 1852. I can go to the Index to the Census of California Indians and see my relatives listed as "Gold Bluff" tribe and then, after a few years of painstaking searching, infer from that knowledge that we are likely from Espeu. I can constantly comb through the 70+ DNA matches and whatever family trees are available to try to string together a hypothesis of how we're related because the genes do not lie, but I cannot actually prove any of them. Maybe if I travel there and talk to people face to face I can come closer but I lost hope years ago that I can solidly prove what village(s) my family is from. I know who some of my relatives are but I cannot explain in detail how we are related because our families were slaughtered. I could hypothesize that we are also probably Karuk because some of those DNA matches have largely Karuk relatives but the only information I know is that we are Yurok.

It has taken me years to even feel comfortable saying I'm Métis or Yurok because of the lack of knowledge. I have more now, and I still struggle. The best research I could do would be in person but that means money, travel, time off from work, and in the case of going north I need an updated passport. I can pull up Youtube to learn how to bead or listen to Yurok in 20 on Spotify. I can try to reframe my access to the internet and the ability to pay for an Ancestry subscription as a privilege even though it is a fucking shadow of what it actually means to learn the culture. All of this could crumble because maybe someday I might form a grudge with someone online who'll do the deep dive and point out the times my Indigenous ancestors were misrepresented on census or whatever.

There is a lot of art and a lot of stories in me that I am aching to create every day that intimately explore my relationship with my race vs my ethnicity vs generational trauma. I'm not sure if I ever will. Every time I try to put it out there I'm terrified because I don't know enough and I never will.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Xavnamnihitc-Woman

Story originally narrated by Phoebe Maddox a.k.a. Imkanvan, a Karok woman, originally published in “Karuk Indian Myths” by John Harrington (1932), under the title “How the Girl Got Even With The Man Who Made Fun Of Her Packing Fire”. Republished in The Way We Lived: California Indian Reminiscences, Stories and Songs by Malcom Margolin (1981) under the title “How The Woman Got Even”, with contextual notes before and after.

from Margolin’s pre-text notes: “For the Karok, as for the Hupa, marriage was basically a financial transaction rather than a romantic fulfillment. The woman who the Karok held out as an ideal was the one who got—not the man she loved—but rather the highest possible bride price.”

A woman was walking upslope to Ipputtatc; she was going for wood, and she was packing along a fire at the same time. Then all at once she saw somebody downriver coming in the upslope direction. he stopped; he looked. He was carrying his quiver, holding it high up. He said, “What are you packing fire for?”

She answered, “I am cold.”

“What, a quail is already hollering, and nobody is carrying fire; nobody will feel cold,” he said, laughing. “I am going to Amekyaram. They are catching salmon already at Amekyaram.”

He was laughing; he was making fun of her packing fire. Then he went on upriver. The woman too went upslope. She was going to get wood. After walking a little way, she looked up at the air.

“Behold it is going to rain. It is all clouded over.” Then she thought, “oh, how I wish it would rain. Oh, how I wish it would snow.”

Then she prepared the wood, chipping off dry fir bark with a wedge. After a while it was snowing, dry snow, it was snowing a big fall of dry snow. The girl made a big fire there, where she was getting the wood ready. Then she thought, “Just a little later now and I will go downslope.”

All she could think about was that man. She was mad at him because, “why did he laugh at me? That fellow said, ‘I will be passing back through here on my way back this evening, at sundown’.”

She thought, “I guess he is coming back.” Then she put the load on her back. The snow was up to her ankles. She was walking along. She carried the fire back again as she went downslope; she was carrying it in her bowl basket, and she had the wood, too, on her back.

Then all at once there was a noise behind her. It was the man who hollered: “Stop, I want to talk with you.” She stopped.

He said, “do something for me, make a fire for me. I am cold.”

The woman laughed. Then she said, “The quail is hollering, nobody ever feels cold. Nobody feels cold. You are not cold, I think you are telling a story.”

“Make a fire for me. I am carrying here in my hand a head-cut of salmon. Make me a fire for that. I am carrying here in my hand a head-cut of salmon.”

“No!”

“I have here a pair of hair club bands with woodpecker scalps on them.”

Then she said, “No!”

“Well then, I will give you my quiver, and all that is inside of it; all that I will give you.”

“No!”

“I will give you my fishery, Ickecatcip.”

“No!”

“I am carrying inside here a flint knife.”

“No!”

“Well, then, my armor; I will give you my armor.”

“No!”

“Well then, let me marry you then; you can make a slave out of me.”

“Well then, I will make a fire.”

So she made a fire, a fire. The man warmed himself. Then he was alright; he warmed himself thoroughly.

Then they went home, to Xavnamnihitc, to the woman’s house. She had him for her slave, and they were going to live at her house [not the man’s house, the more usual marital arrangement]. She was happy, she was laughing all the time. That is what Xavnamnihitc-woman did.

from Margolin’s post text notes: “Thus Xavnamnihitc-woman got a fine bride-price—not only treasure, but ownership of the man himself. No wonder she was laughing! She was the idealized Karok heroine: calculating, firmly insistent that her rights be respected, quick to take advantage of a situation, and always attentive to wealth and material possessions.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

As much as I love to picture Bigfoot whimsically walking through the forest patting all the animals as he walks by, he is not, of course, always depicted that way. In different witness encounters and oral history he is described much differently. Here’s some of his scarier stories from Native American history as written by Cowboys and Indians Blog. “The Yokut believe when you see a Bigfoot, it’s not a good sign. It means he’s coming to take somebody who’s going to pass over to the other side. There’s even a Hairy Man song that women sing during a funeral, to make sure he does take that soul over.” The Yokut aren’t alone either. You’ll find stories of Bigfoot-like creatures in the oral tradition of dozens of North American tribes under a slew of names — Sasquatch and Skookum among them — each ascribing slightly different qualities to the creature. For the Yurok and Karuk of northwest California, Bigfoot is just another denizen of the forest, worthy of cautious respect, just like a bear or a cougar.

But for the Me-Wuk of the Yosemite area, Bigfoot is a boogeyman — not unlike the witch from Hansel and Gretel — snatching children from their tribe and eating them. There’s even a place in the Stanislaus National Forest, Pinnacle Point Cave, where the tribe believes the Bigfoot consumed its victims. “This cave really did have human remains in it that were excavated back in the 1960s,” Strain says. “And what’s interesting is that you have to actually rappel down into this cave to see it. So how did a tribe, that didn’t have any climbing equipment, have a traditional story that the cave had bones in it?” If that’s not strange enough, the indigenous peoples of coastal British Columbia, nearly 1,000 miles to the north, share a nearly identical legend of the cannibal Dzunukwa, “The Wild Woman of the Woods” — often depicted on totem poles displaying a behavior that comes up time and time again in Bigfoot accounts: whistling. “I’ve had many tribes tell me, ‘If you hear whistling at night, don’t go outside,’ ” Strain says. “Because that’s a Bigfoot trying to lure you out.”

Art by Daniel Eskridge

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Building Community Engaged Scholarship: Dr. Melissa Leal

Thu, Apr 16, 2020

12:00pm - 1:00pm

Tune in here: https://www.facebook.com/UCDavisNAS/

Dr. Leal is an enrolled member of the Ohlone/Costanoan Esselen Nation. She earned her Ph.D. in Native American Studies from the University of California, Davis in 2012. Her research includes the reciprocal relationship between Hip Hop Culture and Indigenous Communities with an emphasis on performance, activism, and visual sovereignty.

Melissa is currently the Tribal Liason for Sierra College and the Story Producer for the alter-Native ITVS Series. She considers herself a community academic, a lightweight linguistic, a lifetime educator, and a passionate dancer who strives to assist young people in finding their voice in their community through activism, art, and scholarship. This event is part of the Building Community Engaged Scholarship series hosted on the Native American Studies UC Davis Facebook page.

Building Community Engaged Scholarship: Dr. Cutcha Risling Baldy

Thu, Apr 23, 2020

12:00pm - 1:00pm

Tune in here: https://www.facebook.com/UCDavisNAS/

Dr. Risling Baldy is Hupa, Yurok and Karuk and an enrolled member of the Hoopa Valley Tribe. She is Chair of Native American Studies at Humboldt State University. Her research is focused on Indigenous feminisms, California Indians, and decolonization. She received her Ph.D. in Native American Studies with a Designated Emphasis in Feminist Theory and Research from the University of California, Davis. Her book takes an in-depth and often personal look at the revitalization of women's coming of age ceremonies as a decolonizing praxis that (re)writes, (re)rights and (re)rites Indigenous epistemologies of gender and demonstrates how these ceremonies support self-determination.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

YUROK RESERVATION, Calif. (AP) — The young mother had behaved erratically for months, hitchhiking and wandering naked through two Native American reservations and a small town clustered along Northern California’s rugged Lost Coast.

But things escalated when Emmilee Risling was charged with arson for igniting a fire in a cemetery. Her family hoped the case would force her into mental health and addiction services. Instead, she was released over the pleas of loved ones and a tribal police chief.

The 33-year-old college graduate — an accomplished traditional dancer with ancestry from three area tribes — was last seen soon after, walking across a bridge near a place marked End of Road, a far corner of the Yurok Reservation where the rutted pavement dissolves into thick woods.

Her disappearance is one of five instances in the past 18 months where Indigenous women have gone missing or been killed in this isolated expanse of Pacific coastline between San Francisco and Oregon, a region where the Yurok, Hupa, Karuk, Tolowa and Wiyot people have coexisted for millennia. Two other women died from what authorities say were overdoses despite relatives’ questions about severe bruises.

The crisis has spurred the Yurok Tribe to issue an emergency declaration and brought increased urgency to efforts to build California’s first database of such cases and regain sovereignty over key services.

“I came to this issue as both a researcher and a learner, but just in this last year, I knew three of the women who have gone missing or were murdered — and we shared so much in common,” said Blythe George, a Yurok tribal member who consults on a projectdocumenting the problem. “You can’t help but see yourself in those people.”

The recent cases spotlight an epidemic that is difficult to quantify but has long disproportionately plagued Native Americans.

A 2021 report by a government watchdog found the true number of missing and murdered Indigenous women is unknown due to reporting problems, distrust of law enforcement and jurisdictional conflicts. But Native women face murder rates almost three times those of white women overall — and up to 10 times the national average in certain locations, according to a 2021 summary of the existing research by the National Congress of American Indians. More than 80% have experienced violence.

In this area peppered with illegal marijuana farms and defined by wilderness, almost everyone knows someone who has vanished.

Missing person posters flutter from gas station doors and road signs. Even the tribal police chief isn’t untouched: He took in the daughter of one missing woman, and Emmilee — an enrolled Hoopa Valley tribal member with Yurok and Karuk blood — babysat his children.

In California alone, the Yurok Tribe and the Sovereign Bodies Institute, an Indigenous-run research and advocacy group, uncovered 18 cases of missing or slain Native American women in roughly the past year — a number they consider a vast undercount. An estimated 62% of those cases are not listed in state or federal databases for missing persons.

Hupa citizen Brandice Davis attended school with the daughters of a woman who disappeared in 1991 and now has daughters of her own, ages 9 and 13.

“Here, we’re all related, in a sense,” she said of the place where many families are connected by marriage or community ties.

She cautions her daughters about what it means to be female, Native American and growing up on a reservation: “You’re a statistic. But we have to keep going. We have to show people we’re still here.”

Like countless cases involving Indigenous women, Emmilee’s disappearance has gotten no attention from the outside world.

But many here see in her story the ugly intersection of generations of trauma inflicted on Native Americans by their white colonizers, the marginalization of Native peoples and tribal law enforcement’s lack of authority over many crimes committed on their land.

Virtually all of the area’s Indigenous residents, including Emmilee, have ancestors who were shipped to boarding schools as children and forced to give up their language and culture as part of a federal assimilation campaign. Further back, Yurok people spent years away from home as indentured servants for colonizers, said Judge Abby Abinanti, the tribe’s chief judge.

The trauma caused by those removals echoes among the Yurok in the form of drug abuse and domestic violence, which trickles down to the youth, she said. About 110 Yurok children are in foster care.

“You say, ‘OK, how did we get to this situation where we’re losing our children?’” said Abinanti. “There were big gaps in knowledge, including parenting, and generationally those play out.”

An analysis of cases by the Yurok and Sovereign Bodies found most of the region’s missing women had either been in foster care themselves or had children taken from them by the state. An analysis of jail bookings also showed Yurok citizens in the two-county region are 11 times more likely to go to jail in a given year — and half those arrested are female, usually for low-level crimes. That’s an arrest rate for Yurok women roughly five times the rate of female incarcerations nationwide, said George, the University of California, Merced sociologist consulting with the tribe.

The Yurok run a tribal wellness court for addiction and operate one of the country’s only state-certified tribal domestic violence perpetrator programs. They also recently hired a tribal prosecutor, another step toward building an Indigenous justice system that would ultimately handle all but the most serious felonies.

The Yurok also are working to reclaim supervision over foster care and hope to transfer their first foster family from state court within months, said Jessica Carter, the Yurok Tribal Court director. A tribal-run guardianship court follows another 50 children who live with relatives.

The long-term plan — mostly funded by grants — is a massive undertaking that will take years to accomplish, but the Yurok see regaining sovereignty over these systems as the only way to end the cycle of loss that’s taken the greatest toll on their women.

“If we are successful, we can use that as a gift to other tribes to say, ‘Here’s the steps we took,’” said Rosemary Deck, the newly hired tribal prosecutor. “‘You can take this as a blueprint and assert your own sovereignty.’”

Emmilee was born into a prominent Native family, and a bright future beckoned.

Starting at a young age, she was groomed to one day lead the intricate dances that knit the modern-day people to generations of tradition nearly broken by colonization. Her family, a “dance family,” has the rare distinction of owning enough regalia that it can outfit the brush, jump and flower dances without borrowing a single piece.

At 15, Emmilee paraded down the National Mall with other tribal members at the opening of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. The Washington Post published a front-page photo of her in a Karuk dress of dried bear grass, a woven basket cap and a white leather sash adorned with Pileated woodpecker scalps.

The straight-A student earned a scholarship to the University of Oregon, where she helped lead a prominent Native students’ group. Her success, however, was darkened by the first sign of trouble: an abusive relationship with a Native man whom, her mother believes, she felt she could save through her positive influence.

Later, Emmilee dated another man, became pregnant and returned home to have the baby before finishing her degree.

She then worked with disadvantaged Native families and eventually got accepted into a master’s program. She helped coach her son’s T-ball team and signed him up for swim lessons.

But over time, her family says, they noticed changes.

Emmilee was uncharacteristically tardy for work and grew more combative. She often dropped off her son with family, and she fell in with another abusive boyfriend. Her son was removed from her care when he was 5; a girl born in 2020 was taken away as a newborn as Emmilee’s behavior deteriorated.

Her parents remain bewildered by her rapid decline and think she developed a mental illness — possibly postpartum psychosis — compounded by drugs and the trauma of domestic abuse. At first, she would see a doctor or therapist at her family’s insistence but eventually rebuffed all help.

After her daughter’s birth, Emmilee spiraled rapidly, “like a light switched,” and she began to let go of the Native identity that had been her defining force, said her sister, Mary.

“That was her life, and when you let that go, when you don’t have your kids ... what are you?” she said.

In the months before she vanished, Emmilee was frequently seen walking naked in public, talking to herself. She was picked up many times by sheriff’s deputies and tribal police but never charged.

The only in-patient psychiatric facility within 300 miles (480 kilometers) was always too full to admit her. Once, she was taken to the emergency room and fled barefoot in her hospital gown.

“People tended to look the other way. They didn’t really help her. In less than 24 hours, she was just back on the street, literally on the street,” said Judy Risling, her mother. “There were just no services for her.”

In September, Emmilee was arrested after she was found dancing around a small fire in the Hoopa Valley Reservation cemetery.

Then-Hoopa Valley Tribal Police Chief Bob Kane appeared in a Humboldt County court by video and explained her repeated police contacts and mental health problems. Emmilee mumbled during the hearing then shouted out that she didn’t set the fire.

She was released with an order to appear again in 12 days after her public defender argued she had no criminal convictions and the court couldn’t hold her on the basis of her mental health.

Then, Emmilee disappeared.

“We had predicted that something like this may ... happen in the future,” said Kane. “And you know, now we’re here.”

If Emmilee fell through the cracks before she went missing, she has become even more invisible in her absence.

One of the biggest hurdles in Indian Country once a woman is reported missing is unraveling a confusing jumble of federal, state, local and tribal agencies that must coordinate. Poor communication and oversights can result in overlooked evidence or delayed investigations.

The problem is more acute in rural regions like the one where Emmilee disappeared, said Abigail Echo-Hawk, citizen of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma and director of the Urban Indian Health Institute in Seattle.

“Particularly in reservations and in village areas, there is a maze of jurisdictions, of policies, of procedures of who investigates what,” she said.

Moreover, many cases aren’t logged in federal missing persons databases, and medical examiners sometimes misclassify Native women as white or Asian, said Gretta Goodwin, of the U.S. Government Accountability Office’s homeland security and justice team.

Recent efforts at the state and federal level seek to address what advocates say have been decades of neglect regarding missing and murdered Indigenous women.

Former President Donald Trump signed a bill that required federal, state, tribal and local law enforcement agencies to create or update their protocols for handling such cases. And in November, President Joe Biden signed an executive order to set up guidelines between the federal government and tribal police that would help track, solve and prevent crimes against all Native Americans.

A number of states, including California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona, are also taking on the crisis with greater funding to tribes, studies of the problem or proposals to create Amber Alert-style notifications.

Emmilee’s case illustrates some of the challenges. She was a citizen of the Hoopa Valley Tribe and was arrested on its reservation, but she is presumed missing on the neighboring Yurok Tribe’s reservation.

The Yurok police are in charge of the missing persons probe, but the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office will decide when to declare the case cold, which could trigger federal help.

The remote terrain where Emmilee was last seen — two hours from the nearest town — created hurdles common on reservations.

Law enforcement determined there wasn’t enough information to launch a formal search and rescue operation in such a vast, mountainous area. The Yurok police opted to forgo their own search because of liability concerns and a lack of training, said Yurok Tribal Police Chief Greg O’Rourke.

Instead, Yurok and Hoopa Valley police and sheriff’s deputies plied the rain-swollen Klamath River by boat and drove back roads.

Emmilee’s father, Gary Risling, says the sheriff’s office failed to act on anonymous tips, was slow to follow up on possible sightings and focused more resources on other missing person’s cases, including a wayward hunter and a kayaker lost at sea.

“I don’t want to seem like I’m picking on them, but that effort is sure not put forward when it becomes a missing Indian woman,” he said.

Humboldt County Sheriff William Honsal declined interview requests, saying the Yurok are in charge and there are no signs of foul play. O’Rourke said the tips aren’t enough for a search warrant and there’s nothing further the tribal police can do.

The police chief, who knew Emmilee well, says his work is frequently stymied by a broader system that discounts tribal sovereignty.

“The role of police is protect the vulnerable. As tribal police, we’re doing that in a system that’s broken,” he said. “I think that is the reason that Native women get all but dismissed.”

Emmilee’s family, meanwhile, is struggling to shield her children, now 10 and almost 2, from the trauma of their mother’s disappearance — trauma they worry could trigger another generational cycle of loss.

The boy has been having nightmares and recently spoke everyone’s worst fear.

“It’s real difficult when you deal with the grandkids, and the grandkid says, ‘Grandpa, can you take me down the river and can we look for my mama?’ What do you tell him? ‘We’re looking, we’re looking every day,’” said Gary Risling, choking back tears.

“And then he says, ‘What happens if we can’t find her?’”

1 note

·

View note

Text

In the Land of the Grasshopper Song, M. Arnold

Two young women spend 1908-1909 on the Klamath river in Northern California as Field Matrons for the US Indian Service.

Living close to nature is beautiful and scary

When there are so few people around, you build strong relationships

This area is very remote and the gold rush there only lasted 2 years, so the white influence was minimal in 1908 and still might be (relatively).

Karuk Indians

Sing and drum every day multiple times.

Dunk in the river twice per day.

Extended silences in conversation, no compliments, lots of teasing/joking.

0 notes

Photo

STILL HERE

Today we celebrate California Indian Day 🙌🏽 California is home to 100+ distinct Indigenous cultures + communities.

We honor the legacy and contributions of our California Native leaders, artists & innovators who have shaped the beautiful state we call our home

🎨: Lyn Risling (Karuk, Yurok, Hupa)

#first nations#genindigenous#indigenous#california indian day#decolonize#matriarchy#lyn risling#riseupasone

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Sharing knowledge this Native American Heritage Month"

I am a proud tribal member of Doyon, one of the 12 Alaska Native regional corporations. Unlike the “lower 48” states, Alaskan Native tribes are organized as incorporated entities. My family has lived and fished in Alaska for generations; we have a fish camp on the Yukon River where we come together every summer to live off the land, with no running water, no electricity and no access except by boat. Growing up each summer on the Yukon has taught me the importance of knowledge sharing—passing traditions and customs from one generation to the next.

As a Googler, I’ve never lost sight of this, and continue sharing knowledge with those around me. This October, I partnered with my tribe to create a robotics workshop with the Google American Indian Network, an employee resource group made up of Googlers from across the company who are passionate about making an impact for indigenous communities. Software engineers from Google traveled all the way from California to Fairbanks, Alaska to facilitate robotics lessons for a group of Alaskan Native high school students from villages across the Interior. Using robotics kits, these students coded and competed in four back-to-back competitions over the course of three days.

Benjamin Fate Velaise teaching robotics

The author, Googler Ben Fate Velaise, worked with student Shauna to build hardware designed to shield their robot from invaders in preparation for a “capture the flag” competition.

Googlers teaching robotics

Googler Chad Talbott works with student Dontae to code his robot’s trajectory. Dontae’s team won second place in the first competition.

Googlers and students

Googlers and Doyon employees stand with student attendees in the lobby of Fairbanks Pipeline Training Center toward the end of the three-day workshop.

This is just one of the several ways Google, and the people who work here, are honoring Indigenous communities, especially now during Native American Heritage Month. The Doodle team kicked off the month with a Doodle honoring Will Rogers, a Cherokee Nation member and champion of positive political commentary and aviation. The Google Arts and Culture team shared a story about Rogers’ legacy, and held a special interview with currently elected Cherokee Nation Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. at Google’s offices in Mountain View.

Just last month, we celebrated a partnership between the Google American Indian Network and Celilo Village, a Native American community on the Columbia River, where we were able to bring Wi-Fi to its residents. This project is a positive step forward to improve the digital divide between urban and rural communities, which is especially apparent for Native communities across the country.

Earlier this year, Google Earth launched a project enabling people to meet—and hear—more than 50 Indigenous speakers from around the globe, including a Cherokee speaker from Oklahoma and a Karuk speaker and Central Pomo speaker both from California. Yesterday, the Global Oneness Project and Google Earth released a lesson plan and activities to help teachers explore Indigenous languages vitality with their students. For Indigenous speakers interested in submitting their language to the collection, the Google Earth team is taking submissions through the end of this year.

I feel proud to be a part of two corporations: my heritage as a tribal shareholder of Doyon, an Alaska Native regional corporation, and my role as a Googler, where our mission is to make the world’s information accessible to all, extending knowledge beyond regions and customs. I’m excited to be a part of a new generation of knowledge sharing in the interior of Alaska, one that ignites a passion for education and helps build the next great generation of Alaskan Natives who like their ancestors, use the resources available to them to make an impact in their communities.

Ana Baasee’(thank you)!

Source : The Official Google Blog

via Source information

0 notes

Photo

Karuk art. Baskets by Elizabeth and Louise Hickox, early 1900s. American Indian Art. #Denver #DenverArtMuseum #Patterns (at Denver Art Museum)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

6 Reasons to Protect Northwest California #BLMWild Treasures

The Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) Arcata and Redding Field Offices in northern California are tasked with caring for about 400,000 acres of public lands in Mendocino, Humboldt, Del Norte, Trinity, Siskiyou, Shasta, Butte, and Tehama counties on behalf of the American people. The BLM is currently seeking public input on how these lands should be managed over the next decade or more. Why we should care about protecting #BLMWild places in the region:

1. These public lands are stepping stones for wildlife and are among the most untouched in the region. The surrounding areas have suffered a long history of logging, mining, road construction and other development activities. In some places, these lands are all that’s left of a watershed.

2. Tucked between National Forest lands and private property, these “wild islands” are treasures to the northern California way of life as important habitat for wildlife, the source of clean drinking water, areas of recreation and places with cultural significance to Native Americans.

3. Connecting Islands of Habitat — These islands of public lands range from approximately 30,000 acres to as little as 40 acres. But the importance of these lands is outsized. They help connect habitat for bald eagles, river otters, salmon and steelhead and many more species of wildlife.

4. Safeguarding Sources of Clean Water — The rivers and streams that originate or run through these public lands contribute to the region’s supply of water for drinking as well as what’s needed for municipal and agricultural use. Protecting these lands is an investment in the area’s water supply. These rivers and streams also provide habitat for salmon and steelhead and their conservation is critical for the region’s fisheries.

5. Experiencing the Outdoors — As the BLM updates their blueprint for the region, we have a chance to conserve sensitive public lands from development and enhance opportunities for people to experience the outdoors. These lands include places that are suitable for recreation activities like hiking, camping, mountain bike riding, horseback riding, kayaking, rafting and canoeing.

6. Recognizing Culturally and Historically Significant Lands — The public lands that will be considered during this process include places that are historically and culturally important for the region’s Native American tribes, including the Cahto, Karuk, Wintun and Yurok nations and the peoples represented by the Round Valley Indian Tribes. Input from these communities will be critical during this process.

If you care about how your public lands are managed, this is your opportunity to make your voice heard! Make your comments by February 3 on the California Wilderness Coalition’s action page, and learn more on our website.

- California Wilderness Coalition

#BLMWild#wilderness#california#water#habitat#wildlife#wildlands#public lands#outdoors#culture#history#recreation#landscape#nature#environment

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indian rhubarb (Darmera peltata) is a flowering plant that is the only member of its genus. It's named after Karl Darmer, a German horticulturist who appears otherwise lost to history. It grows in extremely wet environments, in silt or very rocky soil, on streambanks or sometimes right out of shallow, fast-moving streams. The flowers bloom first in the early spring, on long, hairy, alien-looking stalks, and the leaves, which surround the stems, come later in the season. While cultivated today as an ornamental, the Karuk people ate the peeled young stalks as a green vegetable, called kaaf, added them to soups and stews, and administered an infusion of the roots to aid women during pregnancy.

#plantstagram #canwestopnamingplantsfordeadwhitepeople

instagram

0 notes

Text

Native approach to controlled burns has multiple benefits

Using traditional techniques as a part of fire suppression could help revitalize American Indian cultures, economies, and livelihoods—and reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires, a new study suggests.

Researchers say the findings could inform plans to incorporate the cultural burning practices into forest management across an area one and a half times the size of Rhode Island.

Traditional baby baskets of Northern California’s Yurok and Karuk tribes made out of hazelnut shrub stems cost more than a new iPhone XS. They come at a premium not only because skilled weavers handcraft them, but also because the stems required to make them only grow in forest understory areas experiencing a type of controlled burn tribes once practiced but has been suppressed for more than a century.

“We must have fire in order to continue the traditions of our people,” says Margo Robbins, a Yurok basket weaver and director of the Yurok Cultural Fire Management Council who advised the researchers. “There is such a thing as good fire.”

“Burning connects many tribal members to an ancestral practice that they know has immense ecological and social benefit especially in the aftermath of industrial timber activity and ongoing economic austerity,” says lead study author Tony Marks-Block, a doctoral candidate in anthropology at Stanford University who worked with Lisa Curran, professor in environmental anthropology.

Traditional tribal fire treatments can increase production of high-quality raw materials for baskets while reducing the danger of uncontrolled wildfires. (Credit: Tony Marks-Block)

Cultural burns

The study, published in Forest Ecology and Management, replicates Yurok and Karuk fire treatments that involve cutting and burning hazelnut shrub stems. The approach increases the production of high-quality stems (straight, unbranched, and free of insect marks or bark blemishes) needed to make culturally significant items such as baby baskets and fish traps up to 10-fold compared with untreated shrubs.

Previous studies have shown that repeated prescribed burning reduces fuel for wildfires, thus reducing their intensity and size in seasonally dry forests such as the one the researchers studied in the Klamath Basin area near the border with Oregon.

This study was part of a larger exploration of prescribed burns being carried out by Stanford and US Forest Service researchers who collaborated with the Yurok and Karuk tribes to evaluate traditional fire management treatments. Together, they worked with a consortium of federal and state agencies and nongovernmental organizations across 5,570 acres in the Klamath Basin.

The consortium has proposed expanding these “cultural burns”—which have been greatly constrained throughout the tribes’ ancestral lands—across more than 1 million acres of federal and tribal lands that are currently managed with techniques including less targeted controlled burns or brush removal.

Tribes traditionally burned specific plants or landscapes as a way of generating materials or spurring food production, as opposed to modern prescribed burns that are less likely to take these considerations into account.

‘Fires with a purpose’

The authors argue that increasing the number of cultural burns could ease food insecurity among American Indian communities in the region. Traditional food sources have declined precipitously due in part to the suppression of prescribed burns that kill acorn-eating pests and promote deer populations by creating beneficial habitat and increasing plants’ nutritional content.

“This study was founded upon tribal knowledge and cultural practices,” says coauthor Frank Lake, a research ecologist with the US Forest Service and a Karuk descendant with Yurok family. “Because of that, it can help us in formulating the best available science to guide fuels and fire management that demonstrate the benefit to tribal communities and society for reducing the risk of wildfires.”

It would be easy and efficient to include traditional American Indian prescribed burning practices in existing forest management strategies, the authors write. For example, federal fire managers could incorporate hazelnut shrub propane torching and pile burning into their fuel reduction plans to meet cultural needs.

Managers would need to consult and collaborate with local tribes to plan these activities so that the basketry stems could be gathered post-treatment. Larger-scale pile burning treatments typically occur over a few days and require routine monitoring by forestry technicians to ensure they do not escape or harm nearby trees. As these burn, it would be easy for a technician to simultaneously use a propane torch to top-kill nearby hazelnut shrubs. This would not require a significant increase in personnel hours.

“These are fires with a purpose, says Curran, who is also a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. “Now that science has quantified and documented the effectiveness of these practices, fire managers and scientists have the information they need to collaborate with tribes to implement them on a large scale.”

The National Science Foundation, the US Joint Fire Science Program, Stanford’s anthropology department, the Stanford Office of the Vice Provost for Graduate Education’s Diversity, Dissertation Research Opportunity, and the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences Community Engagement funded the work.

Source: Stanford University

The post Native approach to controlled burns has multiple benefits appeared first on Futurity.

Native approach to controlled burns has multiple benefits published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

Incredible summer field course on fish and watersheds

Ecocultural Restoration and Salmon Science in the Klamath Basin

A field course co-generated with the Karuk Tribe’s Píkyav Field Institute

Cleo Woelfle-Erskine AIS 475 A / SMEA 550A & B| I&S, NW, DIV credit | SUMMER 2019

Field study in Northern California, June 30-July 11 | Data workshop at UW July 15-17

This course will immerse students into ecocultural research collaborations along

California’s Klamath River through ecological field work at restoration sites, cultural

presentations by Native and non-Native salmon protectors, and readings in Indigenous

studies, salmon ecology, river restoration, and watershed governance. UW students and

Karuk students in the Píkyav Field Institute will learn together while collecting scientific

data on salmon habitat projects with the Karuk Tribe, Quartz Valley Indian Community,

Mid-Klamath Watershed Council, and Scott River Watershed Council. Through

reflective multi-media field journals and collaborative data analysis projects, students

will understand how Native and non-Native science and ecocultural systems intersect

environmental governance projects like the Klamath dam removals. Group camping

equipment will be provided. A course fee covers all food, lodging, and travel costs.

UW students priority enrollment: April 15-17. Questions? Contact [email protected]

0 notes

Text

Women of Running Strong: Cheryl Tuttle

Cheryl Tuttle is principal at Round Valley Elementary/Middle School (“Home of the Mustangs and Colts”) in Covelo, California. She has also been the mentor for three Running Strong for American Indian Youth® Dreamstarters®-- Blaze Burrows (2016), Shayleena Britton (2017) and this year Lourdes Pedroza-Downey, all members of the Round Valley Indian Tribe.

In her message to students and parents on her school’s website, Cheryl writes that she and her staff “are honored to serve as educators in this beautiful valley for children we love and respect and feel blessed to serve.”

In addition to serving as principal at the elementary/middle school, Cheryl also teaches Wailaki language classes at Round Valley High School where she has inspired Blaze, Shayleena, Lourdes and many other students at the school to work to preserve their nearly-lost tribal language.

The Round Valley Native American Studies Program, their Dreamstarter mentor organization, has a very powerful mission statement: “Through teaching about traditional values,

Native American history, contemporary Native American issues, local culture and Native language, the Round Valley Unified School District’s Native American Studies Program will inspire a deeper understanding of ourselves and our Native communities, promoting self-growth and encouraging generosity through community service and education.”

The program serves an amazing 350 individuals with a full-time staff of only two and about a dozen volunteers. Numerous articles have been published about Cheryl’s innovative techniques in instilling a sense of cultural pride in hundreds, if not thousands, of her students over the years.

The Press Democrat of Santa Rosa, California, report in 2017 that the school’s Wailaki language project is the “brainchild” of Tuttle and teacher Rolinda Want, a Dreamstarter Teacher, who a few years earlier began talking about adding a Native American language course at Round Valley High.

However, when Cheryl and Rolinda decided they wanted to teach a local language, they had many to choose from; many different tribes were forced onto what is now known as the Round Valley Indian Reservation, historically the lands of the Yuki Tribe. Many families of all those tribes – including Yuki, Wailaki, Concow, Little Lake Pomo, Nomlacki and Pitt River Indians – have resided there for generations.

When Cheryl and Rolinda decided to teach a local language, “they had many to choose from,” the Press Democrat reported. “The original reservation was a babel of languages, each with distinct dialects. Many of the current residents claim relatives from multiple tribes.

But one thread seemed to be a connector – “Everyone is like Wailaki and something else,” Cheryl said.

However, as The Press Democrat reported, it would be no easy task resurrect the language. For one thing, it was never a written language, so they had zero original documents to refer to.

In addition, no audio recordings existed, and as far as they knew, there was no one who actually spoke more than a few words of Wailaki.

For help, they turned to an assistant professor in the University of California at Davis’ Native American Studies program who had experience in what is known as the Athabaskan language group, and, as luck would have it, they connected with a UC Berkley linguistics grad student (and native Hupa) who was doing her dissertation on Wailaki grammar.

Among the invaluable resources they came across was the work of Pliny Earle Goddard, who in the first decade of the 20th century transcribed 36 stories told to him by a Round Valley tribal member known as “Captain Jim.”

From those and other sources, they were able to piece together a solid core of Wailaki and the first year they taught the class in 2014-15, they learned along with the class and since then the database has grown and changed.

And where words don’t exist, they have been creative in devising Wailaki equivalents – such as “hand talk” for “phone.”

Cheryl has developed strong relationships with her Dreamstarter® mentees such as Blaze, a student in her Wailaki class whose Dreamstarter® project was to spread knowledge about how to play a traditional Wailaki stick game.

“Blaze and I get along well, know each other as teacher-student who want to make a difference in our Native communities,” Cheryl reported.

She noted the positive change in Blaze, who was only 16 when he received his $10,000 Dreamstarter® grant, saying “Blaze has grown up with this grant. He started out very shy and withdrawn. The Running Strong Dreamstarter® Academy in Washington, DC, really challenged him, but he met the challenge and came away a stronger public speaker and more confident.

“The community has welcomed the stick game, as evidenced through the invitations we receive from community organizations that want Blaze to put on trainings and games at their events,” she reported. “The males involved in the training love it. They find the sport to be fun, and love the opportunity to feel that their ‘maleness’ is accepted and honored.

“I am renewed in hopefulness and energy as a result of seeing Blaze’s dream become a reality in such a short period of time. As a member of a Native community, I’ve lived with disappointment and heartache all the time, but with this project, through the eyes and efforts of a youth, I can see that we don’t have to live in disappointment and heartache; instead, I can turn my energies towar our youth, listen to their dreams, help them realize their dreams, and see a brighter future.”

And, as a whole, Cheryl observed that the Dreamstarter® program benefited not just Blaze, and not just the school, but the entire community.

“The grant allowed our youth to shine and provided an opportunity to integrate Native culture within the school district. Implementing this program within the school district helped with public relations with tribal members that haven’t, in the past, seen.”

For Cheryl, who is Yurok and Karuk, the Wailaki classes are much more than a fun way to keep kids occupied, notes The Press Democrat.

“I think that the language is the mind of the people,” Cheryl is quoted as saying. “Inside of the language, even in the way things are spoken about, you know how people thought. How the ancestors thought about things, what was important to them.

“Their world view is wrapped up in language.”

0 notes

Video

youtube

highest mountain in California Cascade Range Oregon-California border Nevada border conical summit cap Mount Rainier and Mount Hood Geologists grassy tundra, large rocky scree fields glaciers Karuk Indians Úytaahkoo White Mountain Harriette Eddy and Mary Campbell

0 notes