#japanese occupation of kiska

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

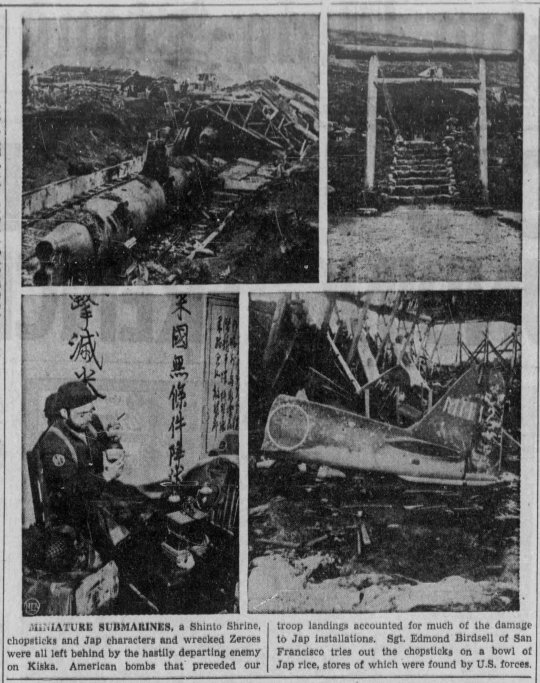

"MINIATURE SUBMARINES, a Shinto Shrine, chopsticks and Jap characters and wrecked Zeroes were all left behind by the hastily departing enemy on Kiska. American bombs that preceded our troop landings accounted for much of the damage to Jap installations. Sgt. Edmond Birdsell of San Francisco tries out the chopsticks on a bowl of Jap rice, stores of which were found by U.S. forces." - from the Kingston Whig-Standard. September 9, 1943. Page 2.

#kiska#aleutian islands campaign#アリューシャン方面の戦い#midget submarine#type A Ko-hyoteki#japanese occupation of kiska#pacific war#world war ii#united states army#imperial japanese navy

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My image on top from the Canadian Heritage Warplane Museum in Hamilton Ontario... An employee standing in front of a PBY-5A aircraft.

Bottom image:

A Consolidated PBY-5A Catalina Flying Boat of Patrol Squadron VP-61 in flight during a patrol in the Aleutians in March 1943. VP-61 was based at Otter Point Naval Air Facility, Umnak Island, Alaska (USA), at that time. In the Battle of the Aleutian Islands (June 1942-August 1943) during World War II (1939-45), U.S. troops fought to remove Japanese garrisons established on a pair of U.S.-owned islands west of Alaska. In June 1942, Japan had seized the remote, sparsely inhabited islands of Attu and Kiska, in the Aleutian Islands. It was the only U.S. soil Japan would claim during the war in the Pacific. The maneuver was possibly designed to divert U.S. forces during Japan’s attack on Midway Island (June 4-7, 1942) in the central Pacific. It’s also possible the Japanese believed holding the two islands could prevent the U.S. from invading Japan via the Aleutians. Either way, the Japanese occupation was a blow to American morale. In May 1943, U.S. troops retook Attu and three months later reclaimed Kiska, and in the process gained experience that helped them prepare for the long “island-hopping” battles to come as World War II raged across the Pacific Ocean. (Photo source - U.S. Navy 80-G-475409) (Colourised by Richard James Molloy from the UK)

1 note

·

View note

Quote

When a Japanese invading force struck at Dutch Harbor in early July 1942, in the war's first threat to the North American continent, it expected little or no opposition from land-based aircraft. The invaders were turned back after continuous attacks by fighters and medium bombers of the 11th Air Force operating from secret, advance bases. When the enemy had established positions out on the Aleutian Island chain the 11th moved after him, making its first attack on the enemy's main base at Kiska on June 11. The last attack came 14 months later, after strikes and sorties conducted in some of the worst weather in the world. So effectively did the 11th persist in its attacks on Jap bases that the enemy rarely had a score of planes operative at one time. Construction of advance bases on Adak and Amchitka permitted action at closer range and made possible air assistance to our surface forces when they occupied Attu in May 1943. After feeling the effects of 3000 tons of bombs, dropped by the 11th in 3609 sorties up to July 19, 1943, and after their supply lines had been cut by the occupation of Attu, the enemy evacuated Kiska without a struggle. Elimination of the enemy fro the Aleutians enabled the 11th to consolidate its hard-won gains, build up new bases, strengthen others and improve its supply lines. Operating principally from Attu, heavy bombers of the 11th began long range attacks on the enemy's bases in the Kurile Islands. By early 1944, despite unfavorable weather conditions, these attacks against the outer fringe of the enemy's homeland were increasing in intensity.

The Official World War II Guide to the Army Air Forces

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 Facts About The Japanese Invasion Of Alaska

10 Facts About The Japanese Invasion Of Alaska

Many people believe that World War II was fought in the cities of Europe and the islands of the South Pacific. It was, but what those people forget is that for about a year from 1942 to 1943, the Imperial Japanese Army occupied the Alaskan islands of Attu and Kiska.

This occupation shocked and terrified North America, and the subsequent events in the aftermath of the occupation set the stage…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

A little known fact of WWII is that Japan attacked North America several time. Aside from the Pearl Harbor attack, the other attacks were relatively unsuccessful

Below a summary of some of those attacks.

On June 3–4, 1942, Japanese planes from two light carriers Ryūjō and Jun’yō struck the U.S. military base at Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands, Unalaska, Alaska.

Originally, the Japanese planned to attack Dutch Harbor simultaneously with its attack on Midway but it occurred a day earlier due to one-day delay. The attack only did moderate damage on Dutch Harbor, but 78 Americans were killed in the attack.

On June 6, two days after the bombing of Dutch Harbor, 500 Japanese marines landed on Kiska, one of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. Upon landing, they killed two and captured eight U.S. Navy officers, then took the remaining inhabitants of the island, and seized control of American soil for the first time.

The next day, a total of 1,140 Japanese infantrymen landed on Attu via Holtz Bay, eventually reaching Massacre Bay and Chichagof Harbor. Attu’s population at the time consisted of 45 Native American Aleuts, and two Americans – Charles Foster Jones, a 60-year-old ham radio operator and weather observer, and his 62-year-old wife Etta, a teacher and nurse. The Japanese killed Jones after interrogating him, while his wife and the Aleut population were sent to Japan. The invasion was only the second time that American soil had been occupied by a foreign enemy, the first being the British during the War of 1812.

A year after Japan’s invasion and occupation of the islands of Attu and Kiska, 34,000 U.S. troops landed on these islands and fought there throughout the summer, defeating the Japanese and regaining control of the islands.

Bombardment of Ellwood

The United States mainland was first shelled by the Axis on February 23, 1942 when the Japanese submarine I-17 attacked the Ellwood Oil Field west of Goleta, near Santa Barbara, California. Although only a pumphouse and catwalk at one oil well were damaged, I-17 captain Nishino Kozo radioed Tokyo that he had left Santa Barbara in flames. No casualties were reported and the total cost of the damage was officially estimated at approximately $500–1,000. News of the shelling triggered an invasion scare along the West Coast.

Bombardment of Estevan Point Lighthouse

More than five Japanese submarines operated in Western Canada during 1941 and 1942. On June 20, 1942, the Japanese submarine I-26,

under the command of Yokota Minoru,fired 25–30 rounds of 5.5-inch shells at the Estevan Point lighthouse on Vancouver Island in British Columbia, but failed to hit its target.Though no casualties were reported, the subsequent decision to turn off the lights of outer stations was disastrous for shipping activity.

Bombardment of Fort Stevens

In what became the only attack on a mainland American military installation during World War II, the Japanese submarine I-25, under the command of Tagami Meiji, surfaced near the mouth of the Columbia River, Oregon on the night of June 21 and June 22, 1942, and fired shells toward Fort Stevens. The only damage officially recorded was to a baseball field’s backstop.

Probably the most significant damage was a shell that damaged some large phone cables. The Fort Stevens gunners were refused permission to return fire for fear of revealing the guns’ location and/or range limitations to the sub. American aircraft on training flights spotted the submarine, which was subsequently attacked by a US bomber, but escaped.

Lookout Air Raids

The Lookout Air Raids occurred on September 9, 1942. The only aerial bombing of mainland United States by a foreign power occurred when an attempt to start a forest fire was made by a Japanese Yokosuka E14Y1 “Glen” seaplane

dropping two 80 kg (180 lb) incendiary bombs over Mount Emily, near Brookings, Oregon. The seaplane, piloted by Nobuo Fujita, had been launched from the Japanese submarine aircraft carrier I-25. No significant damage was officially reported following the attack, nor after a repeat attempt on September 29.

Fire balloon attacks

Between November 1944 and April 1945, the Japanese Navy launched over 9,000 fire balloons toward North America. Carried by the recently discovered Pacific jet stream, they were to sail over the Pacific Ocean and land in North America, where the Japanese hoped they would start forest fires and cause other damage. About three hundred were reported as reaching North America, but little damage was caused. Six people (five children and a woman) became the only deaths due to enemy action to occur on mainland United States during World War II when one of the children tampered with a bomb from a balloon near Bly, Oregon and it exploded. The site is marked by a stone monument at the Mitchell Recreation Area in the Fremont-Winema National Forest. Recently] released reports by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the Canadian military indicate that fire balloons reached as far inland as Manitoba. A fire balloon is also considered to be a possible cause of the third fire in the Tillamook Burn. One member of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion died while responding to a fire in the Northwest on August 6, 1945; other casualties of the 555th were two fractures and 20 other injuries.

Japanese attacks on North America A little known fact of WWII is that Japan attacked North America several time. Aside from the Pearl Harbor attack, the other attacks were relatively unsuccessful…

0 notes

Photo

"Decoy aircraft are laid out by occupying Japanese forces on a shoreline on Kiska Island on June 18, 1942."

(US Navy)

#Japanese occupation of Kiska#history#war#military#military history#ww2#wwii#ww 2#ww ii#world war ii#world war 2#world war two#second world war#plane#planes#aircraft#combat aircraft#ship#ships#pacific campaign#Japanese Imperial Navy#1940s#Aleutian Islands Campaign

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

"TINY JAP U-BOAT ABANDONED TO CANUCKS AT KISKA," Vancouver Sun. September 14, 1943. Page 3. ---- Examining the propellers of a miniature Japanese submarine, left in wrecked condition in Kiska harbor, are (left to right) Pte. George E. Verscheure of Chatham, Ont.; Pte. L. J. Bauerlein of Trenton, Ont., and L. Cpl. S. A. Kosior of Fillmore, Sask. They were among Canadians included in units of the task force which re-occupied the island.

#kiska#aleutian islands campaign#アリューシャン方面の戦い#midget submarine#type A Ko-hyoteki#japanese occupation of kiska#pacific war#world war ii#canadian army#imperial japanese navy#trenton#chatham

0 notes

Photo

https://pacificeagles.net/dutch-harbor-raid/

The Dutch Harbor Raid

Often described as a diversionary attack to draw American forces away from Midway, the Japanese attack on Dutch Harbor on the 3rd and 4th of June, 1942, was in fact a distinct operation. The Japanese Army had long desired a presence in the Aleutians in order to protect the Home Islands from any possible incursion by American aircraft and submarines from the north. By occupying the uninhabited but strategically located islands of Kiska, Adak and Attu, Japanese forces could detect any incoming air attacks that might attempt to reprise the Doolittle Raid, as well as basing anti-submarine forces there. More fanciful planners also thought that an offensive through the Aleutians might also lead to an invasion of Alaska and then the continental United States. For the Navy though, the mounting of Operation AL was primarily the price that had to be paid for Army support of the Midway operation.

Despite the bulk of the Japanese Navy being assigned to the Midway operation, substantial naval assets were available for Operation AL. Led by Rear Admiral Kakuji Kakuta, the Dai-ni Kido Butai, or Second Mobile Striking Force, consisted of the small carriers Ryujo and Junyo and their escorts. Ryujo had already seen extensive action, supporting the occupation of the Philippines and the Netherlands East Indies, as well as sortieing into the Indian Ocean in April 1942. Junyo however was brand-new, having recently completed conversion from a passenger liner. Between them, the two carriers were home to 40 A6M Zero fighters, 21 D3A Type 99s and 21 B5N Type 97s. the carriers were escorted by three cruisers and five destroyers, with other surface vessels tasked with supporting the landings on the three target islands.

The main American base in the Aleutians was at Dutch Harbor on the island of Unalaska. This small port was home to a small garrison of troops, including the US Army’s 206th Coast Artillery Regiment with several batteries of 3-inch anti-aircraft guns. There was a small seaplane base capable of hosting a few flying boats, but no airfield. Two airstrips had been secretly constructed at Cold Bay and Fort Glenn, respectively 180 miles and 60 miles distant from Dutch Harbor. These were home to fighters of the Eleventh Air Force, the newest and smallest of the USAAF’s overseas air forces. The Eleventh had a strength of just 4 heavy bombers (two old B-17s and a pair of LB-30s), 31 B-18 and new B-26 medium bombers, and several squadrons of P-40s – including a pair of squadrons from the Royal Canadian Air Force. The US Navy contribution to the air effort was in the form of Fleet Air Wing 4, consisting of VP-41 and VP-42 with twenty PBY Catalinas. All of the flying boats were equipped with the ASE radar, whilst the four USAAF heavies sported the similar SCR-521 – sets which would prove useful in the foul North Pacific weather.

The 2nd Kido Butai arrived south of the Aleutians late on the 2nd of June, 1942, and prepared to launch strikes early the next morning. The arrival of the Japanese was not unexpected – the American forces had been alerted by the same intelligence that warning of the impending Midway attack, and on the 2nd a patrolling PBY provided confirmation when it sighted the fleet 800 miles from Dutch Harbor. Japanese submarines were also busy flying reconnaissance missions: an E9W from I-9 overflew Kiska, Amchitka, Adak and Kanaga, another from I-19 reconnoitred Bogoslof Island, and an E14Y from I-25 flew over Dutch Harbor itself, reporting several cruisers and destroyers in the port.

The Third of June

The morning of the 3rd of June saw the Japanese carrier force mired in very poor weather which delayed the takeoff. Even when the weather did clear, one Ryujo B5N was lost on takeoff, but crew was recovered by a destroyer. Heavy cloud cover prevented regimented formation flying, requiring individual divisions to make their own way to Dutch Harbor. The Junyo contingent would never manage to find the target – the escorting fighters saw another PBY out on patrol and veered away to shoot it down, and then failed to re-join their bomber charges. The Ryujo attack group was then picked up on the SC radar of the seaplane tender Gillis, which radioed a warning to Dutch Harbor and prompted the six ships in port to get under way. Meanwhile, P-40s were scrambled from Cold Bay, 180 miles away, but they would not arrive in time to challenge the attackers.

The Ryujo force broke into clear air just south of Dutch Harbor, opposed only by the 206th’s anti-aircraft batteries. A PBY was just taxiing on the water before beginning the daily mail run to Kodiak, and it was attacked by strafing Zeros. Two passengers were killed and the pilot had to drive the aircraft onto a convenient beach to escape. A second PBY managed to get airborne, harassed by more fighters, and escape into a nearby cloud – but not before it damaged one of the Zeros, which would soon have important consequences. The bombers meanwhile concentrated on Fort Mears, the conspicuous Army base, and bombed a barracks building – 25 men within were killed. Another bomb hit the nearby Russian Orthodox church, which was thankfully empty, and the Navy radio station took a near miss which shook the occupants but did not affect their ability to communicate. None of the ships in the harbour were hit.

Despite what was reported to be ‘heavy’ AA fire, none of the attackers was brought down immediately. One of the three Zeros to arrive was damaged attacking the PBYs, in what would prove to be a momentous piece of fortune for the Americans. The fighter piloted by PO1c Tadayoshi Koga was holed in the fuel tank, and Koga realised he would not be able to make it back to the Ryujo. He elected to crash land on nearby Akutan island, hoping to be picked up by a nearby submarine positioned to rescue stranded pilots. However, on touchdown Koga’s fighter flipped on its back, and Koga himself suffered a fatal broken neck. His fighter remained undiscovered until 10th July, when a patrolling PBY sighted it. A recovery crew found that the Zero was almost intact, and it was soon shipped back to the United States for evaluation – an intelligence boon for the Allies.

The Junyo formation, having failed to find Dutch Harbor in the murky conditions, flew over a small group of American destroyers moored in Makushin Bay to the west. These ships had been positioned as a strike force to challenge any attempted landing on Unalaska. Lacking the anti-ship bombs and the fuel to make an attack, these planes flew back to Junyo to refuel and re-arm, before setting out in an attempt to re-locate the ships. To cap an awful day for the frustrated aviators, they again failed to find the target and returned to base empty handed. Even worse was the experience of four cruiser floatplanes from Takao and Maya, which were sent to reconnoitre Umnak Island. These got lost in the bad weather, and strayed near to the secret airfield at Cold Bay. P-40s were scrambled to intercept, and they shot down two of the scouts.

A flotilla of American warships, Task Force 8, had departed Kodiak under the command of Rear Admiral Robert Theobald in order to confront the attack. However, Theobald needed confirmation of the location of the Japanese carrier force before he could engage, and so Patrol Wing 4 was ordered out on a search mission. However the PBYs were mainly sent north into the Bering Sea to find the enemy, misled by the withdrawal of the Dutch Harbor attackers in that direction. Only two flew to the south west, both of which found the carriers. The first PBY was shot down by the combat air patrol, and although several of the crew escaped into liferafts, some of them died of exposure. Three survivors were later picked up by the cruiser Takao. A second PBY was also attacked by Zeros and forced to crash land, but the crew were rescued by an American patrol boat. Neither Catalina had managed to make a contact report.

The Fourth of June

The following day the search resumed. The weather was again terrible, and a PBY on night patrol in a notably stormy area failed to return, with no trace ever found of the crew. Another flying boat was more fortunate – at 0900 the radar operator got a contact, 160 miles south west of the seaplane base at Umnak. The plane was on its return leg and despite a dwindling fuel supply, the crew counted the contacts, reported them back to Umnak, and got an acknowledgement before heading back to Cold Bay with minimal fuel remaining in the tanks. This turned out to be the most important contact report of the day, pinpointing Ryujo and Junyo for the waiting strike force.

The first PBY sent out from Dutch Harbor to amplify the contact was loaded with a Mark 13 torpedo and a pair of 500lb bombs. This aircraft also relied on its radar to find the Japanese in the appalling weather. The pilot radioed a contact report and then began an attack run, but the aircraft was badly damaged by anti-aircraft fire and had to jettison its ordnance, returning to base on one engine. A third PBY also found the 2nd Kido Butai on radar, and intended to guide Army B-26 bombers in to the attack. Instead the aircraft was found by the combat air patrol and shot down.

Eventually, the Army bombers managed to find the Japanese carriers independently, although the bad weather meant that the formation was badly separated. A single B-26, with a Navy Mark 13 slung under the belly, attacked first. The pilot elected to drop the weapon like a bomb, and ended up missing the Ryujo by 200 yards. Next to arrive were the two old B-17s of the Eleventh, both fitted with radar sets which allowed them to see the enemy despite the terrible weather. Dropping down to low level, the B-17s made individual attacks that failed to hit any ships, but one of the bombers was shot down by anti-aircraft fire. Finally, three more B-26s arrived, again armed with torpedoes. They made runs on the Junyo and Ryujo but, despite claiming the sinking of a ‘cruiser’, managed to hit nothing at all.

Manoeuvring his fleet to avoid these attacks had cost Admiral Kakuta time, and he was unable to launch a second attack on Dutch Harbor until the afternoon of the 4th. A strike force of seventeen bombers covered by fifteen Zeros was launched to hit the town again. Whilst the aircraft were en route, Kakuta received a strange message ordering him to postpone the occupation of the Aleutians and take his fleet south to join up with the fleet then attacking Midway. Unable to comply until his aircraft returned, Kakuta elected to wait for amplifying instructions.

The strike force arrived over a ready-and-waiting Dutch Harbor an hour after leaving the carriers. All ships had left the port except for the Northwestern, an old troop transport that was permanently aground. She was hit by two bombs but her holds had been filled with concrete to make her more stable, and although she burned for three days the thirty-year old ship survived to provide electrical power to the town for months to come. Other bombs hit the hospital at Fort Mears, a nearby warehouse, and one of the anti-aircraft gun emplacements. Four oil storage tanks were destroyed, and almost a million gallons of fuel began to burn. 18 men were killed and 25 wounded. Eight P-40s from Umnak managed to intercept the Japanese on their way back to their carriers, but succeeded only in losing one of their number to the escorting Zeros.

By the time the Ryujo and Junyo planes landed back aboard their ships, Kakuta’s orders to move south had been revoked and he was ordered to continue the occupation of Attu, Kiska and Adak. Realising that Adak was far too close to the American air base on Umnak, he chose to cancel that landing but continued with those on Attu and Kiska. These islands, unoccupied except for small teams at weather stations, fell without loss to the Japanese on the 8th of June. Soon floatplane fighter and flying boat units arrived to defend Kiska from the expected assault by American bombers.

0 notes

Photo

A few days following the bombing of Dutch Harbor, June 6th 1942, the Japanese landed troops in the Aleutian Island chain, capturing Attu and Kiska. On Attu (above) the landing was unopposed, although one civilian was killed and 46 civilian inhabitants captured and eventually evacuated to Japan. Kiska was likewise unopposed, although two members of a military weather station were killed with the other eight captured.

#Japanese occupation of Attu#Japanese occupation of kiska#Japanese Army#Aleutian Islands Campaign#pacific campaign#black and white#1940s#Theme: Aleutians#history#ww2#wwii#ww 2#ww ii#world war ii#world war two#world war 2#second world war

118 notes

·

View notes