#j@theuncannyprofessoro

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sand Man

Male gaze

The "male gaze" is a concept coined by feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey to describe the way visual arts and literature depict the world and women from a masculine point of view. In this perspective, women are typically portrayed as objects of male pleasure, desire, or fantasy, often emphasizing their physical appearance and sexual attractiveness. The gaze positions women as passive, often inviting voyeuristic or objectifying looks from the viewer. This concept highlights how traditional media and culture have been shaped by and for male audiences, reinforcing gender roles and inequalities. The male gaze can limit women's agency, reducing them to mere objects to be looked at rather than fully realized individuals with their own perspectives and experiences.

Analysis

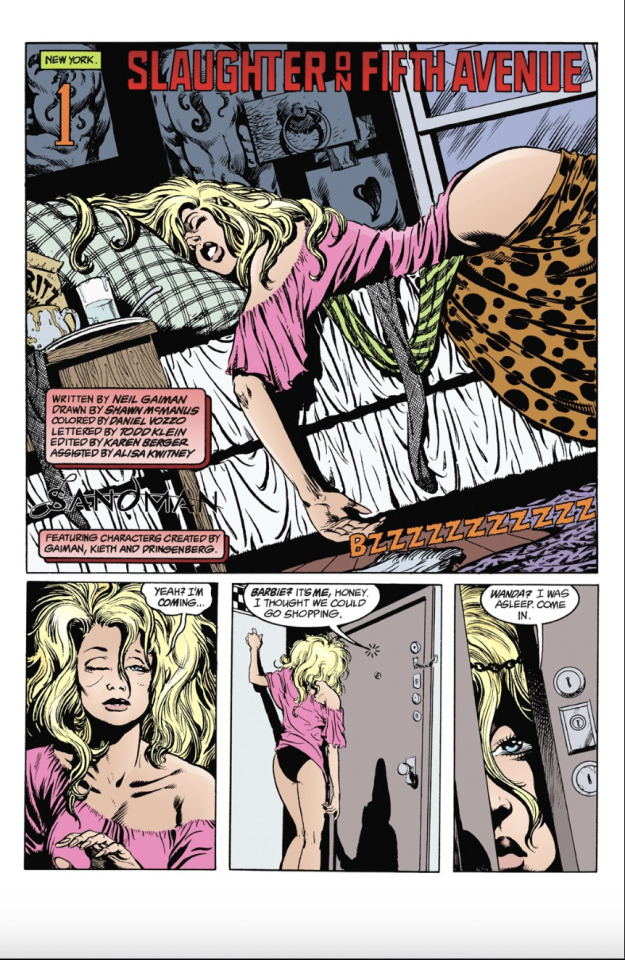

In Neil Gaiman's "The Sandman: A Game of You," the chapter "Slaughter on Fifth Avenue" opens with a representation of the male gaze. This cover introduces Barbie, sleeping on her bed just wearing underwear.

This cover operates on two key principles of the male gaze. Firstly, it positions the viewer as a voyeur. As Laura Mulvey states in Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, "The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed..." [1]. By showcasing Barbie in a vulnerable state, asleep and partially undressed, the image invites the viewer to objectify her. Her body becomes the focal point, divorced from any narrative context.

Secondly, the cover reinforces the power dynamic inherent in the male gaze. Barbie's state of unconsciousness strips her of agency, making her a passive object for the viewer's gaze. The choice of revealing sleepwear further amplifies this dynamic, suggesting her body exists for male pleasure, even in a private moment.

In conclusion, this cover prioritizes aestheticized femininity over plot development or relevance to attract a primarily male audience. This approach undermines the potential for a more nuanced narrative and reinforces the dominance of the male perspective in storytelling.

To-be-looked-at-ness

"To-be-looked-at-ness" is a term that complements the concept of the male gaze and was also introduced by Laura Mulvey in her influential essay on visual pleasure and narrative cinema. It refers to the passive role assigned to women in visual media where they exist primarily to be observed and looked at. She states, "In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness. Women displayed as sexual object is the leit-motiff of erotic spectacle: from pin-ups to striptease, from Ziegfeld to Busby Berkeley, she holds the look, plays to and signifies male desire." [2]. This concept emphasizes how women are often depicted in a way that prioritizes their visual appeal and objectification, rather than their agency or individuality. In the context of "to-be-looked-at-ness," women become objects of the gaze, serving as passive spectacles for the active male viewer. This term captures the idea that women are often framed and presented in visual media to fulfill a voyeuristic or fetishistic desire, reinforcing traditional gender roles and power dynamics. It underscores the reduction of women to mere visual objects, neglecting their complexity and relegating them to a subordinate position in narrative and representation.

Analysis

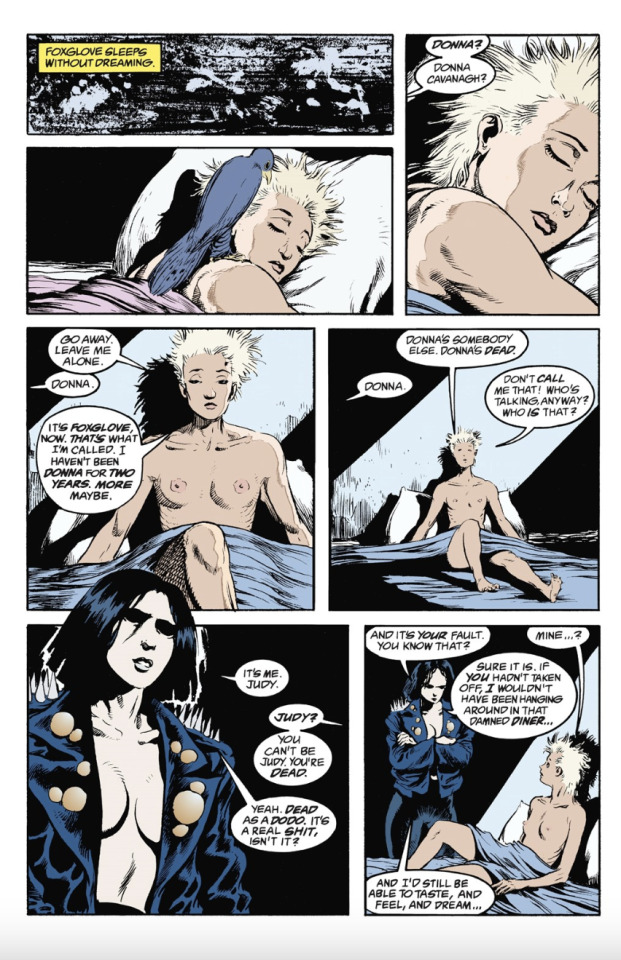

The scene of Foxglove waking up naked in bed blatantly illustrates the concept of "to-be-looked-at-ness." Her nudity is gratuitous, adding nothing to the conversation with Judy or the general plot. This prioritizes her physicality over narrative purpose, turning her into a visual spectacle.

Furthermore, Foxglove's startled reaction positions her as a passive subject caught off guard. This aligns with "to-be-looked-at-ness," where women lack agency and exist to be observed. The focus on her breasts further objectifies her, reducing her to a sexual object.

The scene's perspective, positions, us, the readers, as voyeurs. This reinforces the power imbalance of the male gaze, where the reader enjoys the "privilege" of gazing upon a vulnerable, undressed woman.

Ultimately, this scene prioritizes Foxglove's "to-be-looked-at-ness" over her character or story role. It reinforces the idea that female characters are defined by their bodies and exist for the male viewer's pleasure.

Women as spectacles

"Woman as spectacle" refers to the portrayal of women in media and culture primarily as visual objects to be observed and admired. In this representation, women's value is often equated with their physical appearance and how appealing or desirable they are to the viewer, usually from a male perspective. This concept ties closely with the idea of the male gaze and "to-be-looked-at-ness," where women are positioned as passive recipients of the gaze, existing primarily for visual pleasure. When women are presented as spectacle, their agency, emotions, and experiences are often overshadowed or ignored in favor of their visual appeal. Laura Mulvey explains in Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, "The presence of woman is an indispensible element of spectacle in normal narrative film, yet her visual presence tends to workagainst the development of a story line, to freeze the flow of action in moments of erotic contemplation." [3]. This portrayal can perpetuate stereotypes, objectification, and inequality by reducing women to superficial characteristics and limiting their roles to those that cater to or satisfy male desires. The concept critiques the ways in which media and culture prioritize and commodify women's bodies and appearances, often at the expense of their autonomy and individuality.

Analysis

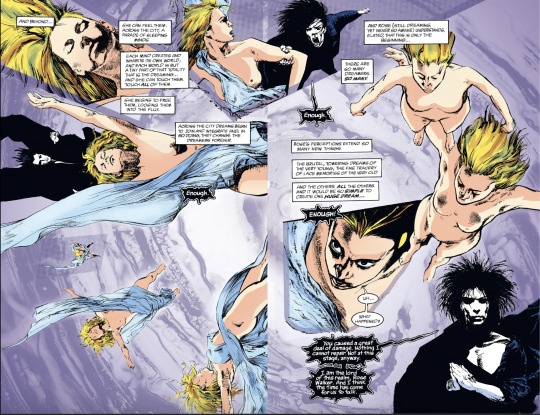

Within The Sandman, the panels showcasing Rose's dream state exemplify the concept of "women as spectacle." There's no narrative justification for her complete nudity. This choice prioritizes the visual display of her body over the dream or plot itself, reducing her to a spectacle within the fictional world, again, likely catering to a presumed male readership.

The scene's focus on her body largely intensifies by depicting Rose's nudity from multiple angles. This excessive focus on her naked body overshadows any potential exploration of her subconscious or the dream narrative. It reinforces the notion that her value lies solely in her physical appearance, feeding into the concept of female objectification. This emphasizes the power imbalances within the male gaze and highlight how female characters primarily serve one purpose in narratives like these, which is to entertain men and function as spectacles. Ultimately, this approach reduces Rose to an object defined by her body rather than her character or role in the narrative.

Gender norms

Gender norms are societal expectations dictating behaviors and roles based on perceived gender. These norms define how men, women, and non-binary individuals should behave, dress, and interact, often reinforcing binary distinctions of masculinity and femininity. Butler in Gender is Burning explains, "Identifying with a gender under contemporary regimes of power involves identifying with a set of norms that are and are not realizable, and whose power and status precede the identifications by which they are insistently approximated" [4]. Traditional norms can be restrictive, enforcing stereotypes and limiting individual expression. Masculine norms might expect men to be strong and unemotional, while feminine norms might prescribe women to be nurturing and appearance-focused. Challenging these norms is crucial for promoting gender equality and inclusivity, recognizing diverse gender identities and expressions beyond traditional categories. Breaking free from rigid gender norms allows for greater self-expression and acceptance, acknowledging the complexity of human identity.

Analysis

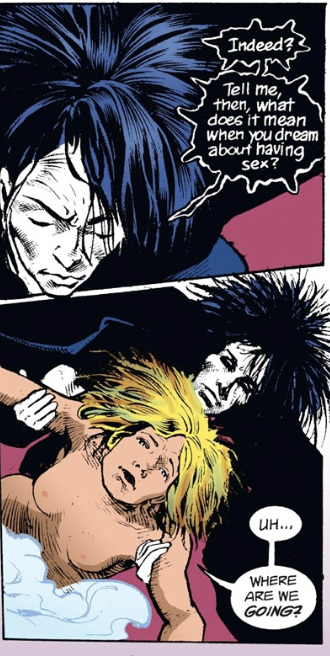

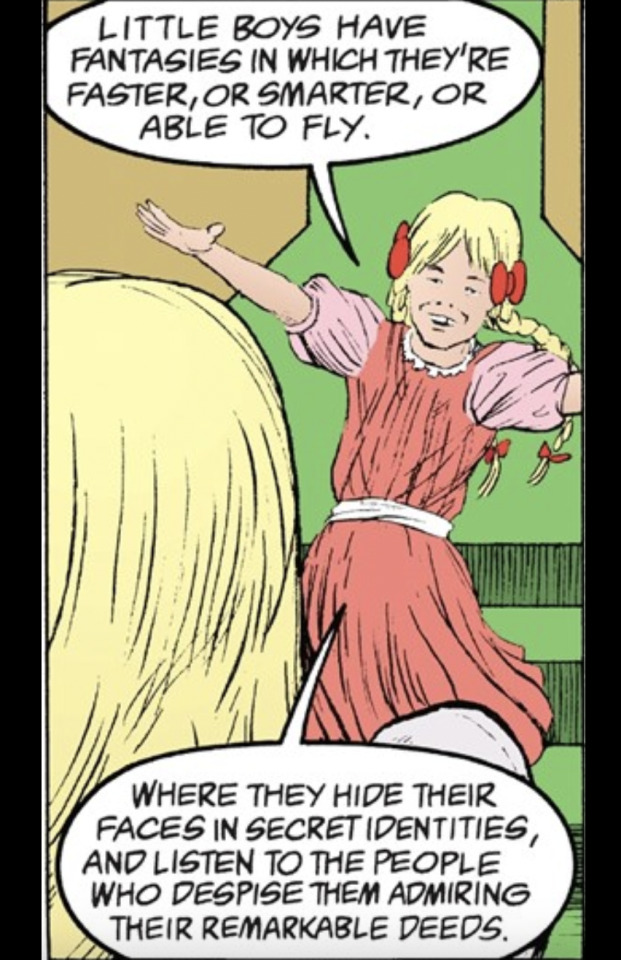

The dialogue between Barbie and Little Barbie in "The Sandman: A Game of You" illustrates traditional gender roles and expectations. During Little Barbie's monologue, little boys' fantasies are described as complex and varied, involving power, intelligence, and adventure. They dream of being heroes, facing challenges, and earning admiration through remarkable deeds. These fantasies encourage agency, ambition, and a sense of adventure, reflecting societal expectations for boys to be assertive, strong, and successful. On the other hand, Little Barbie's description of girls' fantasies is more simplistic and limiting. According to her, girls often fantasize about being princesses, awaiting rescue or recognition. This fantasy reinforces traditional gender roles where girls are passive, dependent, and defined by their relationships to others, particularly men. It perpetuates the idea that happiness and fulfillment for girls come from external validation or rescue rather than personal agency or accomplishment. The contrast between these two sets of fantasies highlights the rigid gender roles and expectations imposed on children based on their gender. It underscores how societal norms shape and limit the aspirations, dreams, and self-perceptions of individuals from a young age.

Positive images

Positive images refer to representations in media and culture that promote diversity, inclusivity, and empowerment, challenging traditional stereotypes and biases. These images showcase individuals from diverse backgrounds, abilities, genders, and orientations in a respectful and authentic manner. They highlight strength, resilience, and individuality, celebrating the unique experiences and contributions of each person. Positive images play a vital role in shaping perceptions and attitudes, fostering understanding, empathy, and acceptance. By portraying a range of identities and experiences in a positive light, they help break down barriers, combat discrimination, and promote social justice. Positive representation in media and culture can empower marginalized groups, inspire change, and contribute to building a more inclusive and equitable society.

Analysis

In the graphic novel, this particular panel featuring Wanda's conversation with the old lady offers a refreshing example of positive representation that challenges traditional stereotypes and biases surrounding older people. Wanda's admission about her identity as a trans woman and the old lady's response create a moment of understanding, acceptance, and empathy.

Instead of resorting to ageist stereotypes where older characters might react with bigotry or misunderstanding, the old lady responds with openness and kindness. She shares a personal experience about her "grandson" transitioning and her daughter's supportive perspective, which brings Wanda a sense of validation and happiness. This interaction counters Jack Halberstam's claims in Looking Butch where he argues that, "Positive images... too often depend on thoroughly ideological conceptions of positive (white, middle-class, clean, law-abiding, monogamous, coupled, etc.)..." by portraying a mentally unstable older lady as capable of acceptance, and understanding [5].

In essence, this panel exemplifies positive images by showcasing a respectful interaction between the old lady and Wanda. By presenting this positive representation, the graphic novel contributes to fostering a more inclusive and equitable society that doenst discrimination solely due to older age.

Works cited:

[1] Mulvey, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, 715.

[2] Mulvey, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, 715.

[3] Mulvey, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, 715.

[4] Butler, Gender is Burning, 339.

[5] Halberstam, Looking Butch, 185.

0 notes

Text

Ferdinand de Saussure and Roland Barthes, in their respective works "Course in General Linguistics" and "Mythologies," offer crucial insights into the intricate relationship between signs, symbols, language, and culture.

Saussure theorized about the arbitrary nature of the sign, suggesting that the relationship between a signifier (word) and its signified (semanticity or meaning) is arbitrary and culturally constructed. Unlike symbols, signs lack inherent connections between their form and meaning. Symbols are usually directly associated with form in some way or another (1). Language, according to Saussure, is the most characteristic of all sign systems due to its complex structure of signs and its widespread usage across cultures, making it a fundamental aspect of human communication and cognition (while still differing from symbols given the arbitrariness of the sign).

Barthes views myth as a semiological system in various ways. A semiological system is a framework through which the aforementioned signs and symbols convey cultural meanings and ideologies, often perpetuating dominant beliefs and values within society (2). Myth, for Barthes, operates as a system of signs that conveys deeper cultural meanings and ideologies through seemingly innocent or naturalized representations. This semiological aspect of myth transforms ordinary objects or concepts into symbols imbued with cultural significance, shaping collective beliefs and values (Ibid). Ultimately, Barthes suggests that myth functions as a system of communication, encoding and perpetuating cultural norms and ideologies through its symbolic representations.

Saussure's concept of the arbitrary nature of the sign highlights the constructed relationship between signifiers and signifieds, with language standing out as the most intricate and pervasive sign system. On the other hand, Barthes's exploration of myth as a semiological system underscores the role of signs in conveying cultural meanings and ideologies. Together, their perspectives deepen our understanding of the complex interplay between signs, symbols, and culture in shaping human communication and perception.

1) Ferdinand de Saussure. Course in General Linguistics. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1966, 1-122.

2) Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. London: J. Cape, 1972.

@theuncannyprofessoro

Reading Notes 3: Saussure to Barthes

In “Course in General Linguistic” and “Mythologies,” Ferdinand de Saussure and Roland Barthes set the groundwork for our studies in semiotics and structuralism.

What is the arbitrary nature of the sign, how is the sign differentiated from a symbol, and why is language the most characteristic of all sign systems?

In what ways is myth a semiological system?

@theuncannyprofessoro

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Power and privilege clearly play a role in how people who are oppressed in different or compounding ways interact with each other. In "Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference," Audre Lorde describes how Black queer women are often shunned by both white women and Black women, though for different reasons. She says they are "caught between white women's racism and Black women's homophobia."[1] It is due to the way white women are allowed to interact with the privileges of the patriarchy because of their proximity to whiteness, and the deeming of queerness as "un-Black"[2] that causes Black women to separate themselves from Black queer women. These power structures inform how each group sees the other's differences. Lorde writes that we must begin to undo the structures implanted in our minds while also bringing down the institutions in our society in order to build new ones that allow our differences to be seen and accepted rather than ignored or destroyed.[3]

There are a variety of representations that support gender performativity, such as the color-coded toys we buy for our kids, appropriate hairstyles for each gender (this varies by culture, of course), and the tropes and stereotypes we see actors performing in film. Judith Butler says in her work "Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion" that it is due to the repeated acts done by people attempting to emulate a gender that actually creates the illusion of this gender.[4] With this, she also asserts that there is no such thing as a "natural" man or woman; rather, we have created this strict binary for ourselves--which is funny because the rules we must follow for each gender change every so often. Butler then continues on to say that heterosexuality, like gender, is "a constant and repeated effort to imitate its own idealizations."[5] In this sense, the natural order of the world, as dictated by a hegemonic heterosexual society, is also an imitation of what is thought to be "correct" or "societally acceptable."

Bibliography:

Lorde, A. 1997. “Age Race Class and Sex : Women Redefining Difference.” Dangerous Liaisons S.

Butler, J. 2000. "Gender is Burning: uestions of Appropriation and Subversion." In Feminist Film Theory. Edited by Sue Thorman. p. 336-348.

[1] Lorde, "Age, Race, Class and Sex"

[2] Lorde, "Age, Race, Class and Sex"

[3] Lorde, "Age, Race, Class and Sex"

[4] Butler, "Gender is Burning"

[5] Butler, "Gender is Burning"

[6] Butler, "Gender is Burning"

@theuncannyprofessoro

Reading Notes 8: Lorde to Butler

In our continued discussions, Audre Lorde’s “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” and “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” and Judith Butler’s Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” provide further introspection into systems and definitions of gender and sexuality.

How do power and privilege impact the relations people have with each other and with institutions, and how can we acknowledge, examine, and remedy oppression and marginalization using oppressive and marginalized systems?

How do cultural, societal, and media representations support gender performativity and in so doing complicate gender norms, and in what ways is heterosexuality a performance?

@theuncannyprofessoro

17 notes

·

View notes