#iww dictionary

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

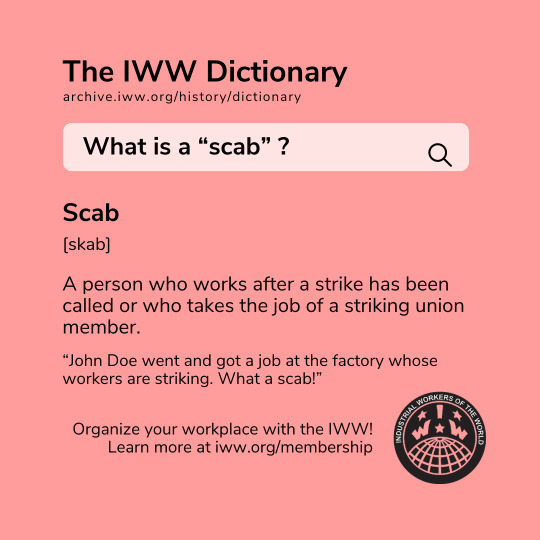

The IWW uses a lot of acronyms and terms you might not know, so the IWW Dictionary is here to the rescue! Today we're defining "scab."

#the iww dictionary#iww dictionary#originals#the iww#iww#industrial workers of the world#the industrial workers of the world#strike#union#unions#scab#scab workers#don't be a scab

626 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inside and Outside: Wolves and Punks

Early-twentieth-century observations of sex between prisoners were shaped by a burgeoning sexological literature whose conceptual categories proved useful in understanding and mapping prison sexual culture. But heightened attention to prison sex in the 1920s and 1930s, on the part of penologists, prison administrators, and prisoners themselves, is not explained simply by the availability of a new conceptual template. While sexologists puzzled over the etiology of same-sex practices performed by apparently "normal" people, those practices would have been more easily and readily comprehended in urban working-class communities of the period.

George Chauncey has documented the visibility of queer life in early-twentieth-century New York City and its integration in working-class and immigrant communities. In that world, Chauncey writes, "the fundamental division of male sexual actors... was not between "heterosexual' and 'homosexual' men, but between conventionally masculine males, who were regarded as men, and effeminate males, known as fairies or pansies, who were regarded as virtual women, or, more precisely, as members of a 'third sex' that combined elements of the male and female.

Prisons were enclosed communities that gave rise to and perpetuated their own distinctive cultures, but they were far from hermetically sealed. The attribution of sexual deviance or "queerness" to the gender transgression of "fairies" and the possibility of conventionally masculine men having sex with them without compromising their status as "normal" found an echo in men's prison populations. Prison vernacular, especially the terms used to denote participants in prison sex, overlapped closely with working-class vernacular and the roles and expectations it delineated, no doubt reflecting its importation into prisons by a disproportionately working-class inmate population and perhaps its exportation into working-class communities as well.

Prison sexual vernacular was part of a prison argot that attracted considerable attention more generally, from both prison insiders and outsiders. Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) organizer and prisoner Hi Simons was fascinated by prison language that seemed to him "full of swagger and laughter, because of the vivid if often violent and vile poetry that streaked through it.... To use it," Simons wrote, "made us feel bold and free." Simons acknowledged that "except for a few terms from the I.W.W. vocabulary," incarcerated labor organizers "added nothing" to the specialized vocabulary of prisoners, but he worked to compile a dictionary of "prison lingo" he learned while an inmate of the U.S. Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth and published it in 1933. Others in this period published glossaries of prison terms as well, testifying to the emergence of a collective consciousness and shared culture among prisoners.

Central to prison argot were the coded terms that delineated sexual types and declared expectations about sexual acts and roles, offering a vernacular analog to sexological taxonomies. Noel Ersine included eighteen terms referring to same-sex sex among the fifteen hundred entries in Underworld and Prison Slang, published in 1933. Simons imagined that "a complete prison dictionary" would constitute "an encyclopedia of all imaginable sexual deviations," rivaling the sexologists' ambitions in cata loging sexual variance."

Prison constituted a unique transfer point between expert and vernacular sexual discourses, the terms of one often inflecting the other. Those men typed by sexologists as "pseudo-homosexuals" or "semi-homosexuals" were known to male prisoners as "wolves" and "punks." Those were men whose participation in same-sex sex was presumed to spring not from their nature but from the exigencies of circumstance. Wolves, sometimes also referred to as "jockers," were typically represented as conventionally, often aggressively masculine men who preserved (and according to some accounts, enhanced) that status by assuming the "active," penetrative role in sex with other men. As Victor Nelson made clear, "The wolf (active sodomist)... is not considered by the average inmate to be 'queer' in the sense that the oral copulist... is so considered. " In contrast to many accounts by penologists and some prison officials who blamed fairies for prison seduction, those most familiar with prison life typically credited wolves with initiating sex behind bars.

That initiation was often aggressive. As their name suggested, wolves were understood to be sexual predators, wooing, bribing, and sometimes forcing other men to have sex with them. Wolves were "always on the lookout for a handsome boy with a weak mind, who had nobody to send them in some food and money," sociologist Clifford Shaw wrote in his 1931 case study of a young juvenile delinquent." Berg described the process by which the wolf secured a sexual partner as "a campaign in which all the luxuries of prison - candy tobacco, sweets, and choice foods - are pressed upon the newcomer." Once the object of the wolf's affection accepted the goods offered, "he is quickly given to understand that he must repay the favor in kind." Sometimes seduction by wolves was described as a deliberate and cold-hearted maneuver of engaging a younger inmate in a relationship of indebtedness, which could be repaid only by sex. Others offered examples of more heartfelt and romantic courtship. Nelson recalled "Dreegan," the "champion "wolf" at Auburn Prison," who

outrageously flattered the objects of his lust; he gave them cigarettes, candy, money, or whatever else he possessed which might serve to break down their powers of resistance; and otherwise courted' them exactly as a normal man 'courts a woman. Once the boy had been seduced, if he proved satisfactory, Dreegan would go the whole hog, like a Wall Street broker with a Broadway chorus-girl mistress, and squander all of his possessions on the boy of the moment.

Wolves may not have been motivated by "true" homosexuality, in the understanding of contemporaries, but the relationships they forged in prison were often far from casual. Jealous rivalries and violent confrontations among inmates were credited to the passionate feelings of some wolves for their partners. Inmate-author Goat Laven described "brutal fights," some fatal, that arose from sexual jealousies: "It means a kick in the back to steal another man's kid." Louis Berg seconded Laven account. "The unwritten law of the prison forbids any 'wolf" to make approaches to another's 'boy friend' once he is wooed and won," Berg observed. "But it is not to be expected that men who break the laws for lesser urges will hesitate when they are driven by passions that rock them to the roots of their being. Fights occur between 'wolves' over some boy which are sanguinary and even end in murder."

Berg went on to recount the murder of "Mildred," an inmate at Welfare Island, by her jealous ex-lover. "From all accounts, Berg observed, "Mildred' was the victim of jealousy caused by 'her' unfaithfulness. That 'she' paid with 'her' life partner. shows the seriousness with which such prison marriages' are regarded." To some, the jealous violence that prison relationships could spark testified not only to depth of feeling but also to their similarity to heterosexual relationships. In a disturbing comparison, Berg concluded that Mildred's murder "proves how completely such relationships are identified with the normal ones between men and women." Charles Ford described jealousies among female inmates that resulted in fist fights, "hair pullings," and "every other conceivable type of trouble making activity" and that were even more real than husband-wife jealousies."

One theory explaining the existence of prison wolves, enshrined in inmate lore by the early twentieth century, proposed that "a 'wolf' is an ex-punk looking for revenge!" The object of wolves' and jocker attentions were known as "punks" and "kids," often identified as younger inmates, unfamiliar with life behind bars and unable or unwilling to defend themselves physically. A type recognized in prison argot at least the early twentieth century, punks were understood to be "normal" men, vulnerable to sexual coercion by other inmates because of the combination of small physical stature, youth, boyish attractiveness, and lack of institutional savvy. A few accounts suggested that punks were potential homosexuals whose latent desires were nurtured and realized the prison context, but most saw them simply as the unfortunate victims of wolves.

The punk's fate was often attributed to naïveté and, especially, his ignorance of the inmate code and the consequences of indebtedness. Charles Wharton wrote in his 1932 prison account of a fellow inmate, "a mere boy" who "seemed to have come direct from a farm" who had "all the bewilderment of a child thrust into strange, frightening surroundings." The youth soon became the object of "pretended interest and sympathy" from other convicts, who showered him with presents, "silk hose, fancy underwear, food stolen from the kitchen, and best of all, cigarets [sic], the gold standard of prison barter." In the process, Wharton wrote, the boy "became a wretched victim of the most vicious circle in Leavenworth's convict population.

Punks also suffered as a result of their youthful good looks. Jim Tully, author of the many books on his experiences on the road as a hobo and time in prison, recalled Eddie, a young inmate "with yellow hair and wondering hazel eyes" who was "too beautiful to be a boy." Eddie's life in prison as a result "was made a constant hardship by sex-starved men." Berg wrote that prison populations always include "boys at that uncertain age where they have a good deal of the feminine in them." Such boys, Berg wrote, "are in most prized in jails and prisons as virgins." Berg also attributed the fate of punks to "biologic inadequacy (another name for lack of guts)."

Whether understood to be the victims of their own attractiveness, their youth and small stature, or their cowardice, punks were never depicted as wholly willing participants in sex with other men. Although there was little attention to overt sexual violence in early-twentieth-century prison writing, many acknowledged that some form of coercion was often involved in sex in prison, in men's prisons especially. Like wolves, punks were also understood under the rubric of "acquired" homosexuality - they participated in sex with other men not because of a constitutional condition but because of the unusual circumstances of prison life. "Had they never gone to prison," Berg wrote ruefully, "most of them would today be normal men."

Prison sexual vernacular and the culture it delineated overlapped particularly closely with that of itinerant laborers, tramps, and hoboes who traveled the country's highways, rural byways, and railroad arteries in the early decades of the twentieth century. The association between tramping and homosexuality was strong enough by 1939 for a textbook on prison psychiatry to warn of "the possibility of homosexuality in prisoners of the vagabond type," since "this tendency among them appears to be very widespread." In his 1923 study The Hobo, sociologist Nels Anderson characterized homosexual practices among homeless men as "widespread and described relationships between older men, known as wolves or jockers, with younger men, referred to as punks, kids, or "prushuns." In transient communities, young men partnered with older, more experienced men who promised to protect them and teach them how to survive life on the road in return for domestic and sometimes sexual favors.

Judging from many accounts, those relationships were often predatory and abusive. Jim Tully, whose experiences as a "road-kid," hobo, circus worker, prisoner, and professional prize-fighter provided the material exper for his twenty-six books, characterized the jocker as "a hobo who took a weak boy and made him a sort of slave to beg and run errands and steal for him." Punks, he reported, "were loaned, traded, and even sold to other tramps." John Good recalled that the "criminal tramps or yeggs" who were his companions on the road in turn-of-the-century Denver "needed a boy to beg and steal for them, and to listen around for information." "These boys are degraded to unnatural uses," Good reported, "as well as trained in the arts of pickpocketing and sneak-thieving." Josiah Flynt, an early participant-observer of transient life, also described relationships between boys and their jockers, in which "abnormally masculine" men take "uncommonly feminine" boys as partners." Those attachments sometimes lasted for years, and boys remained with their jockers until they were "emancipated."

Men who lived on the road and on the economic margins were vulnerable to arrest, and incarceration in jails and prisons was a nearly inevitable experience for hobos, tramps, and transient workers. It is not surprising. then, that the vocabulary of prisoners would borrow closely from that of hobo culture, another nearly uniformly single-sex world populated by working-class men. Some prison terms revealed a direct etymology between hobo and prison terminology. When Jack London was arrested for vagrancy in Niagara Falls in 1894, he was locked up in the "Hobo." "The Hobo," he explained, "is that part of a prison where the minor offenders are confined together in a large iron cage. Since hoboes constitute the principle division of the minor offenders, the aforesaid iron cage is called the Hobo." Hi Simons defined the term "Bo" as both a "hobo" and "boy, catamite" in his dictionary of prison argot. The direction of influence was probably two-way, and some prison terms were no doubt ported into hobo and working-class vernacular as well.

The importation of sexual vernacular, customs, and assumptions about same-sex practices from transient men as well as from a larger ur-working-class world meant that some prisoners were familiar with the sexual culture they found behind bars. Fiction writer Chester Himes, who was sentenced to the Ohio State Penitentiary in 1928, claimed "that nothing happened in prison that I had not already encountered in outside life." Himes grew up in a middle-class African American neighborhood in Cleveland, but youthful desire for excitement drew him to the city's rougher side. In prison, he wrote, "all sex gratification derived sodomy, and I had encountered homosexuals galore around the Matic Hotel and the environs of Fifty-Fifth Street and Central Avenue Cleveland." The many incarcerated men with transient pasts would've been similarly familiar with wolf-punk relationships in prison, which mirrored man-kid relationships on the road.

But while prisons, then as now, were by disproportionately populated by working-class inmates, they drew prisoners from other demographic groups as well, some of whom were unfamiliar with prison sexual terminology and the roles and assumptions it described. The persecution of political radicals under the Espionage and Sedition Acts passed during the First World War and in the wake of the Palmer raids of 1919 resulted in the incarceration of activists in the 1920s, many of whom became vocal and articulate critics of the American prison system while behind bars. These spokespeople for the working class often betrayed their own distance from and naïveté about working-class sexual life in their prison writing, and many were shocked by the sexual life they witnessed behind bars.

Alexander Berkman, for example, was candid in detailing his own prison sexual education in a chapter on an encounter with another prisoner, "Red," a hobo who worked alongside Berkman. When Red announced to Berkman, "you're my kid now, see?" Berkman claimed not to understand him and asked him to explain. Bewildered by Berkman's naiveté, Red exclaimed, "You're twenty-two and don't know what a kid is! Green? Well, sir, it would be hard to find an adequate analogy to your inconsistent maturity of mind." When Red explained to him the practice he termed "moonology," which he defined as "the truly Christian science of loving your neighbor, provided he be a nice little boy," Berkman professed not to "believe in this kid love," and was deeply shocked, protesting that "the panegyrics of boy-love are deeply offensive to my instincts. The very thought of the unnatural practice revolts and disgusts me." The pedagogical question-and-answer structure of this chapter allowed Berkman to tutor his readers in "moonology" while maintaining claims to his own sexual innocence. He may also have intended to contrast Red's perverse sexuality with his own presumably platonic love for another inmate that he described later in the memoir. But Berkman was far from alone among early-twentieth-century inmate narrators in professing innocence of same-sex sexuality before life behind bars.

When attorney and former Illinois state congressman Charles S. Wharton was sentenced to two years in Leavenworth penitentiary in 1928 for conspiracy in armed mail robbery, he acknowledged his own pre-prison innocence. Prefacing his discussion of "the worst of all phases of prison life," which he attempted to describe "as delicately as possible," Wharton wrote that, "looking back, I felt that I had been everywhere, seen everything, done about all which the average man-about-town is expected to do, and I held that impression until Leavenworth made me feel like a country yokel staring slack-jawed at his first sight of urban sin."

Socialist and anti war activist Kate Richards O'Hare was similarly shocked and appalled by the homosexuality she witnessed as an inmate of the Missouri state penitentiary in Jefferson City in 1919-20. Scoffing at O'Hare's estimate that 75 percent of her fellow inmates were "abnormal" as "entirely too high," Fishman speculated that she was "naturally led into such an exaggeration because, having no previous personal knowledge of prisons, she was swept off her feet to find that such things existed. She was utterly amazed when I told her that homo-sexuality was a real problem in every prison."

Eugene Debs, who was convicted of violating the Espionage Law in 1918 and sentenced to ten years in prison, lamented that "every prison of which I have any knowledge... reeks with sodomy" and wrote with dismay about "this abominable vice to which many young men fall victims soon after they enter the prison." "I shrink from the loathesome [sic] and repellant task of bringing this hidden horror to light," Debs wrote. "It is a subject so incredibly shocking to me that, but for the charge of recreance that might be brought against me were I to omit it, I would prefer to make no reference to it at all." Debs wrote in near-apocalyptic language about the fate of the boy "schooled in nameless forms of perversions of mind and soul" and prison sexual practices that "wreck the lives of countless thousands and send their wretched victims to premature and dishonored graves."

Whether shocked or inured, prisoners of all stripes acknowledged sex in both men's and women's prison as nearly ubiquitous and its roles and customs elaborated to the point that it constituted a culture unto itself. That culture occupied a curious status in early-twentieth-century prisons. Officially, sex between prisoners was unequivocally forbidden. Prisoners who were found engaging in sex were punished, often by placement in solitary confinement and extension of their sentences. Some prisons took harsh and sometimes draconian measures to distinguish homosexual prisoners from the general population in order to humiliate them and punish their behavior. In the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, inmates were reportedly forced to wear a large yellow letter D (designating them as "degenerate") if they were discovered having sex.

The superintendent of the Ohio prison at Chillicothe boasted to the director of the Bureau of Prisons, in response to a question about how he handled the problem of "sex perversion" at the institution, that he had found a way to deter such practices through the use of humiliation. "By this I mean that all known perpetrators or anyone anyway connected with sexual perversions be been compelled to sit at a certain table at the mess hall." A report from Kentucky noted that inmates convicted of sexual offenses had one side of their heads shaved to identify them. These practices of marking prisoners as homosexual were forms of punishment for sexual transgression; they also suggested the need for the production of a legible marker of homosexuality that ran counter to the notion that homosexuals, inside and out, were easily identifiable by their gender transgression.

Homosexual prisoners were also dealt physical punishments. A photograph from a Colorado prison depicted two African American prisoners wearing loose dresses, perhaps as another form of stigmatizing market of sexual deviance, and pushing wheelbarrows filled with heavy rocks as a form of punishment for same-sex sex. Kentucky physician F. E. Wylie proposed sterilization and "emasculation" that would "make it impossible for degenerates to commit sex crimes," adding that "surgery might even be used as a punishment" for homosexuality. The authors of an investigation of the Oregon state penitentiary in 1917 moved further to argue that "in cases of congenital homo-sexuality in the penitentiary," the more radical surgery of castration was necessary, to deprive offenders not only of the ability to procreate but of their libido as well. By the 1920s, more than half of the United States had adopted sterilization laws and some targeted "moral degenerates and perverts" specifically. Those laws were most easily and readily applied to people in prisons, mental asylums, and other carceral institutions.

Sex in prison was officially prohibited and sometimes harshly punished. But because of the difficulty of detection and the belief in its inevitability, prison officers often seemed to take it in stride. Joseph Wilson and Michael Pescor criticized prison officers who "regard homosexual practices as only another kind of dirty joke" and wrote that it was "essential that "this question shall always be considered gravely-never with smiles smirks, and a shrug of the shoulder" in their 1939 text on prison psychiatry, suggesting that this was often precisely how it was treated. Berg confirmed that to officials at Welfare Island, "the 'fairies' were, for the most part, simply the butt for lewd jokes. When they spoke of perverts it was with the kind of indulgence that one uses toward children whose peccadillos are amusing rather than serious." He added that "sex indiscretions" were "rarely detected and still less frequently punished."

If prison guards could not be relied on to maintain a properly vigilant and condemnatory attitude regarding prison homosexuality, the some hoped, prisoners themselves would rise to this role. "Only the co-operation of the decent element will ultimately weed them out," Sing Sing warden Lewis Lawes speculated in 1938. Wilson and Pescor went so far as to suggest that if homosexuals "received a reasonable dose of violence" at the hands of prisoners "known to be aggressively heterosexual," it would "help build up a correct prison community attitude towards this question."

But the community attitude in men's prisons, to the extent that it is possible to generalize, seemed often to be characterized by a rough tolerance, even by those who presumably did not participate in same-sex sex. Samuel Roth, who spent several years in prison for publishing what was considered obscene material, noted that "one thing happened immediately," on his incarceration; "I lost my horrors of [homosexuality] as a vice." He was far from alone. Recalling his experience on a Georgia chain gang in the 1930s, George Harsh had "too many other things to think about to care what two consenting adults do between them." "Under the conditions," Harsh wrote, "I think such a situation was inevitable, and I could understand it and condone it." Indeed, the institutional culture of some prisons recognized the established place of prison fairies. Though fairies were segregated in Welfare Island's South Annex, they were allowed to stage a bawdy Christmas show called the "Fag Follies." In later decades, prisons would sponsor football and baseball games that pitted queens against jockers.

- Regina Kunzel, Criminal Intimacy: Prison and the Uneven History of Modern American Sexuality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008. p. 61-73

#prison slang#convict code#wolves and punks#history of homosexuality#history of heteronormativity#sex in prison#life inside#research quote#reading 2021#hobos#tramps#working class culture#history of crime and punishment#american prison system#victor nelson#chester himes#samuel roth#hi simons#penology#prison administration#queer history

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phrases from My Youth

There was a lot of Wobblie influence on the words people used in Trego when we moved from the coast in 1960 – and the IWW Dictionary, at https://archive.iww.org/history/dictionary/ lets me realize how common phrases from the “One Big Union” were. Some of the terms I learned are listed in the IWW dictionary: Scissorbill – A worker who is not class conscious; a homeguard who is filled with…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Anakin asked that his starfighter be painted yellow, allegedly in tribute to the Podracer he flew as a youth, but perhaps to call attention to himself in battle.

#star wars#anakin skywalker#revenge of the sith#star wars visual dictionary#clone wars#clone wars era#so anakin did something similar to real life Red Baron from IWW#to catch attention to himself during battles#wonder how many clone pilots get alive from those battles when all enemies were busy#trying to shot down anakin

364 notes

·

View notes

Text

Playing with Modern Design

The Wobblies show their wobbliness, which is cleverly illustrated on their box by faint wavy blue lines. Interestingly, there are two definitions of the word wobbly. The first is “inclined to wobble; shaky.” A Wobbly (capitalized) is also “a member of the Industrial Workers of the World, an international, revolutionary industrial union founded in Chicago in 1905.”[1] Although this toy bares no obvious connection to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) or to their radical social cause, there is nonetheless a sense of radicalism in the Wobblies’ highly modern design, whose reductive colorful forms recall the visual vocabulary used by the European avant-garde during the early twentieth century.

The Wobblies’ colorful geometric bodies recall the spirit of the modern movement immediately following WWI. In many countries designers and artists alike integrated progressive concepts of play, childhood, and creativity into their artworks, designs, and ideologies.[2] The early 1920s offers several examples: Giacomo Balla’s and Fortunato Depero’s Italian Futurist toy and furniture designs, Dutch architect and designer Gerrit Rietveld’s furniture designs for children, and in the Weimar Bauhaus’ first preliminary course leader Johannes Itten’s pedagogical exploration of play and games. Nearly two decades later, the Wobblies bring these concepts to American postwar consumer culture.

The Wobblies were manufactured by the New York–based company Paul Bon Hop, Inc.; there is little information today about the company or their products. Two photographs of the company’s toy designs appear in a 1949 issue of the Minneapolis’ Walker Art Center’s Everyday Art Quarterly, however. The issue focuses on “well-designed objects for everyday use” and features objects shown in their annual exhibition “Useful Gifts.” The first photograph is of Molly Kewls, a female figure created from a set of free-form plastic balls and rectilinear connectors. The second is a “Trail-a-way” painted wooden train similar in design to the Wobblies. Browsing recent eBay sales shows that the Molly Kewls toy is not uncommon. A photograph from a previous sale of the toy shows the lid of her black metal container, which has an illustration of her abstract and geometric body on it. Next to her image is her name, the company’s name, and the slogan “TOYS ARE TOOLS FOR LEARNING,” which not only states Molly’s purpose, but also echoes the progressive sentiment of the twentieth-century modern movement’s fascination with childhood, creativity, and play.

[1] Webster’s New World College Dictionary, 5th ed., s.v. “wobbly.”

[2] For an extended discussion about the complex relationship between modern design and childhood see Century of the Child: Growing by Design, 1900–2000. Edited by Emily Hall and Libby Hruska. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012. Exhibition catalog.

Catherine Acosta is a graduate student in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies program offered jointly by the Parsons School of Design and the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She is a Fellow in the museum’s Product Design and Decorative Arts Department.

from Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum http://ift.tt/2noevBz via IFTTT

1 note

·

View note

Text

The IWW uses a lot of acronyms and terms you might not know, so the IWW Dictionary is here to the rescue! Today we're defining "Wobbly."

355 notes

·

View notes

Text

The IWW uses a lot of acronyms and terms you might not know, so the IWW Dictionary is here to the rescue! Today we're defining "BST."

#originals#the iww#iww#the industrial workers of the world#industrial workers of the world#iww dictionary#the iww dictionary#unionize#union strong

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

The IWW uses a lot of acronyms and terms you might not know, so the IWW Dictionary is here to the rescue! Today we're defining "class war."

#originals#the iww dictionary#iww#the iww#industrial workers of the world#the industrial workers of the world#join the iww#unionize#union strong

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

The IWW uses a lot of acronyms and terms you might not know, so the IWW Dictionary is here to the rescue! Today we're defining "FW."

#originals#the iww#iww#industrial workers of the world#unions#union strong#anticapitalist#anticapitalism#labor union#labor unions

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

The IWW uses a lot of acronyms and terms you might not know, so the IWW Dictionary is here to the rescue! Today we're defining "branch."

#iww#the iww#industrial workers of the world#the industrial workers of the world#join the iww#originals

176 notes

·

View notes