#it's this paradoxical thing where the artists makes something for the sake of art and THAT'S what makes it personal for the viewer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Additional Thoughts About Ibara & Aesthetics

Using this image to indicate to you that I'm gonna be mentioning Rouge&Ruby a LOT.

Writing this post on Ibara and Tsumugi's dorm room, it reminded me of some more thoughts I’ve been microwaving in my brain for a while. From the dorm post we’ve pretty clearly established that Ibara… doesn’t express much of a personality in his sense of style 😂 he was born in a wet cardboard box all alone ok

HOWEVER… what I’ve found really intriguing about him (besides everything.) is that despite that lack of self expression in a personal space, he does have a strong sense for art and aesthetics in what he creates.

What tipped me off on this was actually his in-game office interaction with the whiteboard. He has the ‘good’ result of drawing a cute bird, saying he ‘knows a little about the arts’ (which probably means he knows a lot, he’s just being fake humble). When I first saw this, I was a little bit surprised.

So later on, when Rouge&Ruby confirmed that he does do costume designs and storyboards himself, I was pretty excited to see his artistic skills a little bit expanded upon.

And actually, he has said this interesting thing in relation to art:

Translation by Land of Zero

So clearly, Ibara has a sense for the value of art and thinks it’s important.

And it aligns with how he intended for Adam to focus on the art of performance (compared to Eve which is more popular and takes on more entertainment jobs).

What I’m trying to say is that while he obviously loves making money and business domination, he also has an understanding and skill for art and design. Business, art, aesthetics often come hand in hand I think, as having a good concept and attractive visuals is essential to selling anything...

Translation by Land of Zero

Considering he designed every part of Melting Rouge Soul + Ruby Love himself and contacted Hiyori for his connections to chocolate designers so that Eden's chocolates stand out, I feel his consideration for making something with 'artistic and financial value' really comes through in Rouge&Ruby.

Translation by Land of Zero

I think the whole point of that event is that within Ibara there is a passionate burning soul bursting with expression and creativity (even love) in pursuit of his ambitions, and it comes through so so much in those songs and his own performance. He’ll prove Eden’s superiority in every avenue possible, not just monetarily but also artistically.

Although all this is only applied to his work, which is what he’s most passionate about. To Ibara, his work IS him:

Translation by Land of Zero

Additionally, Rinne notes Ibara’s more 'poetic' (and nerdy 🤓) side with how the Minotaurs Labyrinth is designed in Ariadne (variety show Ibara traps Crazy:b in):

Not only do things have to look good, they have to be quite meaningful and conceptual too. I mean, this IS coming from the guy who bases his whole personality and image on one (1) book he read as a sad little kid (Art of War btw) and inserts very unsubtle Bible references everywhere.

And Ibara putting the most effort into his chocolates despite being annoyed at having to make chocolates past Valentine's Day and it having no relation to work:

Translation by Land of Zero. He loves to succeed and be impressive for the sake of it.

So where he doesn’t put much effort into his personal spaces or appearance outside of work, it’s all because Ibara’s personality is just one that’s extremely singularly focused on one thing - his passion and work. I think this creates another interesting and lovely paradox to his personality, just one of the many this guy has. It’s what makes Ibara so delightful as a character.

Tl;dr - Ibara is actually quite into art and aesthetics, and even artistically inclined himself.

87 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ok another thing!

I really like how... feminine Jack is. It's sort of an extension of his manic-pixie-dream-boy status. He's kind, soft-spoken and Rose generally makes him pretty nervous (though he's socially talented enough to work through that really well). This particularly stands out to me during their sex scene. I think it's my favourite sex scene of all time, actually. That may be a weird thing to have, but still. Rose is the one who initiates it ("Put your hands on me, Jack" is a GREAT line) and we immediately see Jack at the most nervous he's ever been. Then when they're done he's literally shaking so Rose asks if he's okay, and then SHE holds HIM as they (mostly Jack tho) calm down.

The movie is so conventional and so unconventional at the same time which speaks to its genius.

Reversal of gender roles isn't something that didn't exist before Titanic though. (and I KNOW that's not what you're saying here, but hear me out) LMA has done it in 1860s!!!!!!!! Greek mythology deals with gender themes (where do you think the term hermaphrodite came from?) In my opinion, Titanic didn't handle the concept in an innovative enough manner (and everybody knows I'm a BIG fan of that concept). It's cool! It's great! Blockbusters introduce the wider audience to great many things, but that doesn't mean they should be praised for every remotely unconventional idea that's a part of the story they're trying to tell. (making the already existing concept your own? that's another thing entirely and I LOVE IT!) What makes a good movie for me is taking what's already there and crowning it with your own unique perspective. What you're praising Titanic for is actually what I appreciate about Lady Bird (2017). It makes you think that it's all about tropes and cliches and everything that's stereotypically meant to speak to the female audience, but then it surprises you and does this fantastic spin on everything you've ever known without disregarding the tropes completely. But it's not just about simultaneously defying and celebrating the tropes (and here's the main difference), it's about this very personal viewpoint that Gerwig incorporated into the film. It's kinda like when you're adapting a book, you shouldn't try to make the movie resemble the source material (because that's NEVER gonna work, you simply can't meet everyone's expectations), you should make it resemble your own understanding of the source material. That's what makes it feel more personal to the viewer. Titanic didn't feel personal to me despite being meant to appeal to people. My point is: it's a movie that was made to be liked and appreciated which yes, isn't inherently a bad thing, but maybe I'm just too into modernism and avant-garde to appreciate that. It really is a personal preference! I like it better when the art I'm consuming doesn't make a big deal out of itself and ends up hitting the emotional mark without meaning to. (the main goal is usually to send some kind of message that tends to be controversial in some way) I don't like it when movie directors assume I'm going to relate to something because "everybody relates to it in some way". You CAN'T know that. (it puts a pressure on people, like you have to be a part of that specific circle or you're not human enough or whatever) This feels like that literature discussion about supposedly pointless overanalysing of motifs or claiming that classic lit is inherently difficult to read or whatever... Maybe it's not just propaganda coming from the male dominated world, maybe I LIKE long discussions on life and death and politics in my movies. (and just because something is problematic in one regard, it doesn't mean it has no significant value or worse, that it shouldn't be explored. you can always learn! from everything!) Which doesn't mean that I don't like a good coming of age story about a teenage girl. Or spend my time watching a teen soap. Or that somebody can't enjoy a romantic comedy if they love Dostoyevsky. Or that these art branches necessarily cancel each other out. (I'm referring to some of the points you made earlier, sorry for drifting away djsjdkkd)

What you can always do in film is present your own unique perspective and celebrate that uniqueness. That's something people can connect with, regardless of the topic. If it makes its way to the heart of ONE person, it's a winner. And Titanic is definitely a winner in that respect! It just didn't get to me. And that's fine too.

Also! The intention behind a certain line doesn't make the line itself good (same goes for film in general)!!!!!! "Put your hands on me, Jack" is just... it's funny. I laughed when I heard it. This movie is just... way better in theory. I LOVED what you had to say about the ideas that went into it, but I didn't really catch that on screen. Both the characters and their love story failed to be compelling in my eyes, the aesthetics got in the way of that even if it wasn't supposed to. That's what happened if you ask me. Oh and disliking traditionally feminine tropes and plot directions and things such as grand romantic gestures or melodramatic confessions of love doesn't immediately mean that you're sexist or have internalized misogyny? Society is responsible for giving those things a bad rep, but disliking them doesn't always have to go beyond disliking them.

I'm making a lot of points here and I'm not wearing my contacts, dear tumblr forgive me. (I don't need you to, I'm just trying to be polite dhjdjdi)

#💌restless wind inside a letter box💌#mal the writer wizard#sorry if i'm being annoying djdjdkkdkr#i've just always been into that 'idk i'm doing this because i like it and if it does something for people that's great!' energy#it's this paradoxical thing where the artists makes something for the sake of art and THAT'S what makes it personal for the viewer#i've felt it in the theatre a while ago#i was sitting there and these people really didn't give a damn about the controversy they were causing by performing that piece#and that's what made it seem like everything they were doing they were doing for me and me alone#titanic is a simple story that's supposed to be a simple story but you shouldn't assume everybody is gonna like it#your goal while making something should never be to please everyone and throw the people who disagree under the bus by using labels#mal the writer wizard 💜💫📝

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone brought up Serra's tilted arch at work yest and they had an interesting perspective. Well actually we both were kind of saying the same thing. It's funny how something can change depending on who you're explaining it to.

Like talking about it to a bunch of artists in art school who have collectively decided serra is someone to dislike (prob justified) you might have to argue if you liked the piece. But like, explaining it to a "non arts" person they thought it was really cool and interesting the way it disrupted everyday life and I think there's truth in that. And I kind of gave it a second chance as I was explaining it to them, like it made me realize how from an outside perspective it is kinda rad in a way, whereas within an art space we are more critical of art that finds itself more important than someones daily path to work.

Part of me finds it idealistic, like we live in a society where the most efficient path does matter. In a society where city efficiency doesn't matter as much there would be more of these architecturally disruptive decisions for the sake of art or meaning, and they'd be more acceptable therefore.

The paradox is in that society a the statement of a disruptive structure wouldn't be worth making, which to me proves it might have a worthy place in our world (some good concepts are edgy). So in a way that makes me like it, because it denies the current context and makes me think of some other society, so maybe it's forward thinking. In some way it's a brazen statement of wealth and success too though. I'm also just not remembering everything about it I guess but lemme stop before I give this too much space in my head.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2020 Summary of Art

Well, I can't do the traditional "Art of the Year" summary thing since I'm not a visual artist, but I figured, why not do something similar with my writing? A paragraph I worked on or posted during each month. January: Time isn't the only problem, of course, or even the main one. Your powers of telekinesis are pitiful, too—the only thing saving you out on the field currently is your, admittedly, impressive physical strength, but you can't depend on that forever. The best Pushers don't rely on pure brute strength like you do. How can you ever hope to reach the level of your hero, Xultan Matzos, without the mental powers to match? February: It was his picture. That was Ciel's first thought. Then he realized it couldn't be him—the boy in the picture was older, yes, but what drew Ciel's attention was the boy's eyes: both were visible and clear. Which was impossible—the contract showed up in photos, and he was bound to Sebastian until the demon consumed his soul. Looking closer, peering over Dipper's shoulder, Ciel noticed something far more alarming: the part in the boy's hair was opposite to his own. March: Motherfuckin’ paydirt. “He better be happy to see me,” you say, although it’s hard to say whether he actually will be or not. You two are bros, and you get along fairly well when you’re both not going out of your ways to be dicks to each other (ironically!), but he can be unpredictable. You know he isn’t going to like how much danger you’ve put yourself in for his sake. His poor self-hating heart just can’t accept that other people actually give a damn about him. It’d make you cry if you weren’t such a stone cold bad ass. “Where is he?” April: Klink wasn’t sure if he was more amused by this display or infuriated. That the American could sit there and say such ridiculous things with a straight face... Either Hogan was being fanatically naïve, or he thought that Klink was fantastically stupid. His hand clenched around the damp handkerchief. More likely than not, it was the latter. He didn’t know why the thought stung so much—it wasn’t anything he didn’t already know. “Victory?” he echoed, allowing Hogan to hear his scorn for the notion. “You think this,” he threw his hand out to indicate the space around himself, “is a victory?” May: “Well you’re looking older and dumber,” Karkat returned hotly. He didn’t turn his back on the adult human, but he backed up to the door. “You’re not my Dave, and I’m not the Karkat you know, so this must be paradox space fucking with me once again, because the universe loves nothing more than shitting on Karkat Vantas.” June: When Karkat pulls down his pants, Dave finds all thoughts of heat stroke leaving his mind. What the hell... It's a fucking tentacle. It's all Dave can do not to break down in hysterical laughter. Oh God. He gets it: this is a hentai. His life has become a fucking anime. Karkat is the eldritch horror, and he is the Japanese school girl about to get tentacle fucked within an inch of her life. This is his fate. July: "yea like we're peak middle school up in here passing notes to each other," Dave is clearly gearing up for a ramble, and Karkat smiles despite himself, "do you like me or like like me but weve got to keep it on the downlow so the teacher doesnt notice and find our note because our reps will never survive if she reads it to the class and she will because thats how teachers roll" August: Dave is still frowning into the mirror, his hands coming up to trace the lines on his chest. He's muscular, but in a wiry way. Trim like Karkat isn't. Pale in a way that begs for a tan. He's beautiful. Karkat has thought this before, but seeing him like this makes the thought rise up again: Dave is beautiful even if he's glaring at himself in a way which reminds Karkat uncomfortably of similar looks Karkat has directed towards a mirror more than once. September: “That’s not how you say those?” He shrugged, watching with barely contained glee as Karkat’s face darkened. “It’s like I told you, Kitbit, I don’t do that boujee shit.” And now, for the piece of resistance: “I’m just here puttin' in the time, spittin' my rhymes. You know I do this on a dime. It ain't work for me; it's play the way the insults fly, leavin' you with l'esprit de l'escalier when I say goodbye.” Then he lifted up his glasses and winked, enjoying the view of Karkat realizing he’d been being played in full color. October: Karkat’s head is pounding from all the thinking he’s had to do to learn Davuh’s words, but it’s a good pain--the kind of pain that means something is growing stronger. He enjoys the warmth of the human next to him, feeling drowsy. He doesn’t always sleep well… he rarely sleeps well. But it’s different with Davuh there. There’s something in his belly, his head aches, and Davuh is warm. November: It was… Xefros doesn’t have the words to describe it. Joey, going around, treating trolls like… like they were the same as her. Like they would just return her kindness and trust because she gave it to them first. Kind of incredible how often she was right. And then she was wrong. Very wrong. December: “No!” The boy’s anger should be frightening what with his sharp teeth prominently displayed in a snarl, but the combination of the drying, cracking green slime coating and the pure offense in his tone makes his posturing more funny than threatening. “No, you don’t get to break into my hive, drag me out of my recuperacoon, feel me up, make weird ass concuspiant passes at me, *and* tell me I need to *chill*! I am the perfectly sane amount of chill for this situation!” Homestuck features pretty heavily this year :D

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frederik Vanhoutte: Creative Coder

I have featured a selection of gifs by Frederik Vanhoutte on Cross Connect, (the link is here, Also, see more of his work on his Twitter feed and Instagram page

Frederik’s gifs are compelling to watch. The way he contrasts the black shape against dark grey with neon colored edges that are revealed as the shape expands and contracts is inspired and beautiful. He uses easing in his motion to great effect as his little machines, or systems, expand and contract in front of you

Frederik was expansive in his answers to my questions about his work and I publish the full interview below:

-----

Who you are and where you are from?

I’m Frederik Vanhoutte, and I’m a creative coder. I’m based in Flanders, Belgium, and currently living in Bruges.

What do you do for a living?

Professionally I’m a medical radiation expert (MPE), active in the radiotherapy department of the Ghent university hospital. What this means is that together with a team of radiation oncologists, nurses, technologist and colleague MPEs I’m responsible for the treatment of people with cancer, using radiation generated by high-energy linear accelerators.

Do you have a background in art?

My background isn’t art, it’s physics, lots of physics. I have a master in acoustics and thermodynamics, a second master in medical physics and a PhD in solid state physics.

How did you start making gifs?

My interest in creative coding grew more or less naturally from toy models, simple physics simulations we set up to test ideas. These are oversimplified and not entirely rigorous, the simulation equivalent of back of the envelope calculations.

In 2003, I came across Processing, a coding framework/application/community aimed towards designers and artists wanting to use computers in their practice. For me, the approach was from a different direction. I was familiar with the rigorous logic of programming and started using Processing for my old toy models. But unlike their original purpose, this time round I started playing around with the models for estethics sake. I didn’t know it then, but these were my first generative systems. In an “about”, I’ll typically say that creative coding fuels my curiosity in physical, biological and computational systems. And that isn’t just a sound bite. For me it represents an important way of thinking about things, of answering questions. I haven’t run out of questions yet, so it doesn’t look like I’m stopping soon.

Do you think gifs are a unique art form?

We tend to talk about the intersection of art and science, two distinct areas that converge in a certain practice. There is something to be said for the idea that that art, even when using technology and scientific terminology, isn’t science; and that science, even if pursued with passion, isn’t art. But the truth probably is that the idea of two distinct regions meeting at an intersection is the wrong metaphor, that instead there is a huge territory where these two quintessential human endeavors flow into each other, mediated by technology, neither art nor science. For me the true intersection is where we meet from different directions, from different backgrounds.

Why gifs, ate least in part of my work? Digital art has many niches but a common thread in generative systems is the emphasis on the system, the dynamics, rather than on the frozen image, the static. But the threshold to share something dynamic is higher than that of a still image. And the platforms to share it on aren’t very stable, Flash is gone, the days of java applets are past, replaced by webgl and javascript, to be replaced by…

The animated gif seems to stand the test of time better, its simplicity undoubtedly part of its success. My first reaction to the question “are gifs a unique art form” was that I don’t see animated gifs as an art form in itself, or even a goal, but as a robust, low-threshold materialization of things which are hard to convey statically,a form of animation. But to be honest, having made more gifs lately, I need to reconsider. The medium of gifs introduces several constraints that impose themselves on the art, and in through those constraints, like any medium, shapes the art, adding its unique nature to it.

So yes, it is a unique medium, a unique art form. I find myself reducing my toy models to the bare essentials when writing them for gifs. Kill your darlings, purity, whatever you can call it, it invites a certain thoughtfulness that gets lost when presented with the basically unlimited possibilities we seem to have in digital art. I genuinely believe the restrictions make the art better.

What I strive to achieve is something architects call simplexity, a complex form that has an elegant, simple underlying structure. Simplicity without visual complexity can be rather dull. Raw, wild complexity is easy to achieve but impossible to control and can paradoxically end up dull. A pet peeve of mine is that generative art often prides itself on “infinite results, each unique”, yet somehow all looking, feeling the same. Simplexity represents the goldilocks zone, neither the dullness of predictability, nor the boredom of the purely random.

As a tool I mainly use Processing. And although tools undoubtedly influence the work, it really is about ideas and principles that can be embodied in various ways. Whether it’s Houdini or threejs, Processing or Excel, or pen and paper or computer, part of the art always transcends the medium.

I hope this answers some of your questions.

Frederik Vanhoutte’s Twitter feed and Instagram page

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Master and Apprentice: An Overview of Themes

Okay, so as many of you may have surmised, I adored this book. There’s so much to talk about in it and the ramifications of some of the themes play all the way up to the Sequel Trilogy.

To be honest, I’m not even sure where to start with everything I want to talk about, but I’m going start here with this basic outline of things I noticed and will dissemble from there over the next few days, weeks, whatever.

Lineage

“You inherit your parents' trauma but you will never fully understand it.”

So I will preface this part by saying that I am a huge fan of Bojack Horseman and this theme comes up again and again and again in this show. (As does the difficulty, but possibility, of breaking that cycle.)

This book is heavy on the behaviors and prejudices and patterns that get passed on through generations, or in this case, lineages. Dooku’s preoccupation with prophecy touches Rael, which touches Qui-gon, which touches Obi-wan, and of course, ultimately plays a huge role in Anakin’s life. Not only that, but Dooku’s restrained, demanding manner seems to have rubbed off on Qui-gon, who seemed to be constantly measuring up Obi-wan to an impossible metric and thinking it in his presence, which meant Obi-wan likely felt all of this and presto changeo we have a talented young Jedi who feels he is unworthy. This book really illustrates how Masters are as much parents as teachers, and how whatever issues the parent is dealing with gets passed down and processed, whether it be through rebellion, imitation, or a host of other reactions. Hell, the book mentions Yoda’s master (albeit not by name). I am *dying* to know who they were and what happened there.

Performance Art

Okay, so one of the initial main culprits is a group of performers who end up being branded as terrorists. First of all, this made musician-me CACKLE, period. But beyond that, there is a running theme of a performative aspect to government, to ceremony (Fanry perfects this), even to the Jedi themselves with their rituals, with their idealistic Code versus reality. Sidious was perhaps the best performance artist of the entire GFFA. And prophecy, to a certain degree, requires performance, requires actors to ingest a script and accept it as truth, and finally meet its demands of life’s stage. Is it foretold because the events must happen or because the actors choose to make them happen?

Prophecy

Which leads me into the thorniest topic of this book. Dooku was obsessed with prophecies. Qui-gon became obsessed with prophecy, to the point of breaking a thousand laws to get Anakin to Coruscant. And then Obi-wan was so devoted to Qui-gon, despite everything, that he told himself he had to believe in the prophecy, for Qui-gon’s sake (back to family issues there.)

How many of these prophecies ended up being self-fulfilling because of the actors involved? (Namely, Qui-gon.) Even when Qui-gon realizes his mistake is trying to control the future instead of accepting it, he goes ahead years later to manipulate circumstances so Anakin can be a Jedi. That’s not accepting the future, he cheated at dice to change the future, to control it. And that action set off an avalanche of consequences I doubt Qui-gon prepared for. In short, Qui-gon is a very fallible character here and shows a fair amount of egotism in terms of his relationship with prophecy.

I mean, the Force showed Qui-gon that he was “meant to misinterpret” his vision? I don’t even know where to start with the sheer audacity of that statement. Qui-gon doesn’t report his vision to the Council, because he thinks they won’t understand, thinks they’ll get mired in some minutiae of governance and not do anything substantial. And yes, the Council does dither, even Obi-wan notices it, but those controls are there for a reason and Qui-gon just runs roughshod over them, because he thinks he alone has the answers, that he alone can change the future.

And it kind of comes back to this whole Lineage issue where Dooku had this attitude that he alone knew the truth. I mean, he defects to the Sith partially to rid the Republic of corruption, and look at his Padawans - Rael and Qui-gon, both iconoclasts, both skirting the edge of...something, and it’s almost laughable that Qui-gon gets so upset with Rael’s disregard of certain parts of the Code (the killing of his Padawan part, of course, but also the celibacy part) because Qui-gon lies and cheats and pulls cons across the galaxy and disregards swaths of the Code at will. And you have to wonder, is this because Dooku was too independent, and if Dooku was that independent, how did Yoda’s training of Dooku play into that?

Then again, while family and upbringing play a huge part in a person’s actions and personality, they are not the only thing, they do not dictate the future. Nor do prophecies. And Qui-gon clings so much to these prophecies, just as Dooku did (and Dooku’s prophecy of choice, he who learns to conquer death will through his greatest student live again is just...it explains a lot as to why Dooku was so devoted to teaching, was so exacting on his students ((although I will never let go of the headcanon that Dooku actually enjoys teaching, because I feel that a personality like his needs someone to impart knowledge to)).

Prophecy, more often than not, becomes self-fulfilling prophecy, which is an interesting paradox. Prophecies are read, believed to be true, and are enacted by the actions of the very people (beings) who read them in the first place.

And thus they become prophecy.

I mean, no wonder Yoda wanted to burn the “sacred texts” by the time The Last Jedi rolls around. Prophecy becomes a way to abnegate responsibility for one’s actions, to deny, whether it’s Dooku seeking to avoid death, Qui-gon proclaiming he is a vessel for the will of the Force, or even Obi-wan claiming Luke as the Chosen One in Twin Suns. (Although, I wonder about that last one, as Obi-wan is naturally skeptical of prophecy. I mean, the Jedi do have the Force and are granted visions, but then again, they make decisions. They choose to turn to the Dark Side, choose to bend to the will of a hazy future which claims no specific actors...and I feel like Obi-wan’s references to prophecy are more an expression of familial love, of tribute to Qui-gon rather than a true belief that Anakin was "the” Chosen One. Obi-wan believed in Anakin himself above all else, even his better judgment.)

The Jinn-Kenobi Express

So...what is going on with these two?

In many ways, this is more of a Qui-gon book than an Obi-wan book, although we get plenty of insight to Obi-wan’s character. And one of the things I really appreciate about Claudia Gray is the fact that she seems aware of the Jedi Apprentice series, the kind of dynamic that created, and weaves this story in a way that does justice to those interactions and the limited time we see Qui-gon and Obi-wan together on screen.

And the thing is, Qui-gon is kind of a jerk to Obi-wan. From page two of this book, his is questioning Obi-wan, wondering why he hasn’t reached a certain point in his abilities yet (all while deliberately holding him back in areas like lightsaber combat, which is an astounding illustration of Qui-gon’s complete obliviousness to his own actions and ramifications of his actions). And, let’s be honest, Obi-wan is an empath - he wouldn’t be such a talented negotiator and diplomat if he weren’t (because, before anything else, you need to be able to read people, to know and feel their emotions in order to succeed at deals, treaties, and diplomacy). Obi-wan knew Qui-gon was questioning him, could feel it and this harkens back to those JA books where Qui-gon is kiiiind of a total douche, at times. And Obi-wan - rebellious, independent, self-esteem-lacking, so wanting someone’s approval Obi-wan...just falls right into this. It’s kind of an unhealthy dynamic, which resolves itself after Pijal, only to relapse all over again when Qui-gon finds Anakin and pulls his BS on Tatooine.

Here’s the thing. Qui-gon is not a bad person. I don’t hate Qui-gon, he has good motivations, he wants to make things better. He cares about Obi-wan, seeks advice from his old Master (not knowing Dooku has fallen, my god), tries to free all the slaves he encounters, wants to buck every piece of Jedi and Republic law in order to make the galaxy right. And, you know, I get it. I really do. But there’s idealism and then there’s trying to do the right thing within the systems (no matter how terrible) we have created and inching forward to change because to do otherwise would be to fight yourself in a paper bag.

Qui-gon is the living embodiment of the phrase “the road to hell is paved with good intentions.”

And Obi-wan knows this, knows Qui-gon is fallible, knows that his devotion to idealism, to prophecy is dangerous and yet he goes along with it anyway because Obi-wan’s greatest failing is his attachment. Obi-wan (the empath) cares too much and he can’t let go - not of Qui-gon, not of Satine, and certainly not of Anakin.

"Let the past die. Kill it if you have to.“ I mean, I’m not a Kylo Ren-stan by any means, but he’s not wrong. At least, not in a broad sense, not in the way that might have allowed Obi-wan to make some clearer-headed decisions about everything from his relationship with Qui-gon to Anakin to the Council.

In Conclusion

Dooku cared about his students but possibly feared death and thus possibly made his students his vessels to achieve the goal of immortality, despite enjoying teaching.

Qui-gon cared about Obi-wan as much as he did the betterment of the galaxy but was terrible at expressing it and put too much faith in himself, the Force, and prophecy.

Obi-wan cared almost too much about everyone but himself, replacing self-esteem with rules and the Code, devoting himself to the memory of Qui-gon and his wishes in his guilt over his survival of the encounter at Theed.

And this writer cares waaaaaay too much about these characters and will most definitely be writing more about this book because, to quote Obi-wan flying a ship in the middle of a ship: AAAAAUUUUUUUUUGGGHHHH

#well#that went on way too long#meta#master and apprentice#master and apprentice spoilers#and more#good god#this got out of control#sorry guys#i just have a lot of FEELINGS about THE LINEAGE#and feel totally justified in some of my previous meta with this book coming out#obi wan kenobi#qui gon jinn#count dooku#NOTICE HOW THE ISSUE OF DOOKU'S REAL FIRST NAME WAS DEFTLY AVOIDED#ha!#can't wait for the audiobook to drop at the end of the month#my god between this endgame and the dooku book it's amazing i manage to get to work and do things for waaaaay too may hours a day#this isn't even touching on the republic government slavery rael's actions or pijal's leadership issues and child monarchs#there's...a lot to get through here#WOW

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

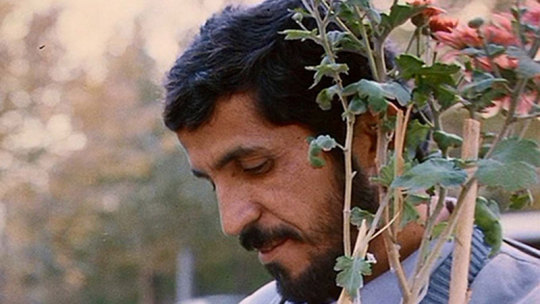

Doomed & Stoned in Iran with Roaring Empyrean

~By Billy Goate~

Photo Credit: Shahrokh Dabiri

It's fair to say that much of our view of the world is muddled by a cloud of politics, whether that comes from the strong opinions of family and friends, the news media, or our elected officials. When I heard such casual joking of bombing Iran during the 2008 US presidential elections, I cringed. Now more than 10 years later, the bluster of obstinate world leaders looms large once again, posturing with the weird flex of war. What most people are missing is real perspective on the people of Iran and, I would argue, the music of that country.

Hell, I was woefully uninformed myself, so when I started noticing more and more offerings from the heavy music community out of Tehran, I struck up a friendship with one doomedshinobi on Instagram, mastermind of the one-man band Roaring Empyrean, "a musical project aiming to create atmospheres where feelings in contrast meet, in a combination of funeral doom metal and New Age." Intrigued, I asked doomedshinobi for an interview and we exchanged words over oceans and breached the cultural divide for one of the more fascinating discussions about the joys and trials of being an artist I've encountered since starting Doomed & Stoned.

When I found doom, I was like someone who had reached his destination after a long journey.

What's it like being a heavy musician in Iran? Most of us have no clue about what's acceptable and not in the culture there.

When you are dealing with a radical ideological regime, you can't reason with them. All kinds of art are seen forbidden here, unless they preach Islam or government ideologies. Things get worse when you are dealing with some art that is Western in nature. Metal is, in nature, Western. And even there, it had its problems sometimes from church and common beliefs. Here, it doesn't matter what you make and what you sing. As long as you are metal, you are seen as Satanic!

I remember reading an article in some magazine about Metallica being black metal, just because they have an album called Black. The author claimed, "They are black metal artists and black metal is Satanic, so they are making music to take away our people from God and Path of Light." I remember reading somewhere that even Pink Floyd was labeled Satanic. So things are hard for you if you are an extreme musician, like metal. You are alone in the scene here. Producers and labels mostly refuse to work with you. Stores won't sell your physical releases and stages to perform are hard to get. There have been many cases when a band got a show and then right before the show or even in the middle of performance, it was forced to be canceled. Many musicians even get arrested afterwards.

In Iran, metalheads find interest more in death and black metal, as well as power and symphonic.

Now imagine you are a musician, a metal musician, a darker and extremer type of metal musician. You are mostly alone on your own to make your own studio, produce your music and release it. This leads to many Iranian bands using free social media to share their music and send the word mouth by mouth. Platforms like Bandcamp, Soundcloud, and YouTube are blocked by the regime and someone like myself has to bypass filters in various ways to get access to these platforms. Due to the poor economy and fall of Iran Rial value, getting a full set of proper equipment costs a fortune. Many young musicians leave all they have to pursue musicianship.

The good thing, though, is people. They are welcoming metal and heavier musical styles more and more with each passing day -- especially the younger generation. But as is all over the world, heavy and extreme metal styles have less fans than most other genres. And if you are to be a heavy style musician, you have to accept this. You either want to pursue money and fame or do what you like for its own sake. There you have something like pop and hip-hop, and doom metal is scarce.

Monuments (Remastered) by Roaring Empyrean

What are you thoughts about the band Confess being imprisoned recently?

Confess is just one example known to the rest of the world of a band that has been imprisoned. I didn't know of them until I read that article, but the things that happened to them are not something new or uncommon among artists of all kinds, and it clearly is unfair. This happens in the extreme to artists pursuing foreign styles of art.

There are some charges that each time they face an opposing idea, they declare it upon the person. Like speech against Islam, against supreme leadership, and against national security! And these charges bring high punishments. I don't want to talk politics and stuff, as I am in Iran. I just wish every artist freedom to express their minds and souls, which is hard to come by. Years of prison for some art is what only a stone age ideology can decide is fair!

Song of the Seas (EP) by Roaring Empyrean

How did you first get into the darker, more expressive side of music? For example, what records have been most influential to you? When did you first start playing an instrument?

This is the most interesting question so far. As a child, I remember my father starting the day with some Pink Floyd, continue it with Metallica, sometimes going softer to Eagles or Eloy. This made me to not get into mainstream pop media even at an early age. He also listened to a lot of Kitaro and Enigma back then. And I got some Vangelis compilation from my uncle. Before 10, I was listening to rock and new age more than anything else, but I was always looking for the extremes in my life, in whatever aspect.

And so in music, I started listening to Linkin Park and System of A Down. They were fast, harsher, and wilder. But you know, there is always a loop. What is hotter than red? When you heat something, it turns red, then yellow and white. What's next? It turns blue! A cold color, but it’s even hotter. I liked to have this hotness of blue which is cold! So, instead of speed (red) I turned into slow (blue), which is more extreme.

I don't know if I make any sense at this point or not, but this is the real motivation for me to dig deeper in slower, heavier music. When I found doom, I was like someone who had reached his destination after a long journey. Doom is that hot blue. It is that extreme paradoxical matter to me. However, I didn't enter doom from the traditional door.

Many young musicians leave all they have to pursue musicianship.

In Iran, metalheads find interest more in death and black metal, as well as power and symphonic. It is hard to come by someone who started metal with stoner, sludge or psychedelic rock. Not impossible, but hard. I entered the doom from the gothic, folk, and death subgenres with acts like Empyrium and Saturnus. But now I appreciate every good metal, especially any doom I can find. That ache for extreme, however, made my primary taste to be funeral doom as we talk now.

Many records helped my musical imagination to go diverse. Vangelis' 'Direct' (1988) is amongst the most influential to me. Each track on that record is in a different style and different color. Vangelis has a diverse musical ground and his works have always been an inspiration to me. You can go right from electronic to orchestral and back to a more rockish sound all in one track! "Intergalactic Radio Station" is definitely my favorite track on that record.

On the metal side, I can't imagine anything more influential than Empyrium's LP, 'Songs of Moors and Misty Fields' (1997). The heaviness and agony in the sound, accompanying various folk and symphonic elements which lead to ever rising feel of the music. It's a rising agony. Truly a masterpiece. Many bands are cold and sad. Empyrium's music is warm and sad to me. This makes them unique. A folksy, symphonic, heavy doomy sound.

And it is not good of me to fail to mention Arvo Pärt, the Estonian classical composer. His minimal depressing compositions made me look at music from a whole new perspective. There is always that minimalist sadness in it, but a call is always moving you forth in his works. Then there is one sudden glorious, majestic rise and a tragic fall afterwards in most of his compositions. My more recent neoclassical elements are definitely due to his works.

Cosmic (EP) by Roaring Empyrean

How did you get inspired to start writing your own music?

I've always loved making music. Composing, rather than playing an instrument. And there was this other thing, called synesthesia. It is a kind of rare mental condition in which two or more of the five primary senses find a way to connect, which aren't connected normally. It has many types. I, however, can see the sounds. It makes me see every sound in my mind in terms of a shape, color, movement/direction, surface roughness, and brightness. I have had this condition since I can remember.

I don't see anything meaningful though, just some random shapes. Like the cello has a thick, dark green, rough line shape at lower notes and a bright, shining, thin green light at higher notes. So when I listened to music, there was a world of colors dancing in my mind and it fascinated me so much. I didn't know this was a thing until age 15.

You are alone in the scene here. Stores won't sell your physical releases and stages to perform are hard to get.

Being able to bring my own desired colors in music was something I wanted to do for a long time. I first started playing guitar back in high school, but that didn't give me the diversity I wanted. So I started creating instrumental tracks which were nowhere near metal -- mostly New Age music with synths. As time passed, my love for doom and heavier sounds found a way into my music. I used many instruments to paint my tracks: cello for green, piano for purple and blue, violin for yellow, sitar synths for shining red points, and guitar riffs for orange -- like a massive wall. My love for New Age and doom metal made me think of that paradoxical extreme once again. Why not try combining dark and heavy doom and funeral doom with bright atmospheric new age? This was when Roaring Empyrean came to life back in 2011.

As many New Age acts, I'd like my music to take the listener on a journey in their minds and make them think -- think about themselves and their existence. People today just follow what they are made to follow, and don't ask why. They don't think about why things are the way they are in this modern world. They lack thinking. They just obey and overfill themselves with whatever joys the unwritten rules are giving them.

What instruments, pedals, and amps do you have access to?

As for the gear, I'm afraid I rely so much on synthesizers and samplers -- not that I want to, but the poor economy here prevented me many times from getting the equipment and instruments I want. We don't produce any non-Iranian instruments, so everything is an imported product, and comparing the falling Rial to GBP or the US dollar, for someone like me, it is still impossible. But I have plans to leave Iran. Maybe then I can get the gear I want and make more lively sounds. But I can't keep quiet and not make music 'till then.

The Monarch (EP) by Roaring Empyrean

Have you had the opportunity to perform publicly?

No, never have I performed public. And I have no intention yet, unless I gather the gear I want. However, I've always liked to perform in a symphony once in my life. Maybe one day.

If you could play anywhere in the world, what would be your top scenes and would there any bands you'd love to be on the same bill with?

Interesting question! My doomy, metallic side likes to perform in the doomiest places. I'd like to perform in a sanctuary or a cave, as I have seen in some festivals like Doom Shall Rise, which is sadly is no longer going on. But there are many. Tokyo, London, and the US are generally places I'd like to perform. The other, non-metal side of me would like to perform at the Vienna Musikverein concert hall with a full orchestra and metal set together performing Roaring Empyrean.

These dreams surely seem impossible now, but there is this Persian saying: "Let the youth dream." I'd be honored to perform alongside Shape of Despair, Pantheist, Worship, Mournful Congregation, and Ankhagram more than others in the scene, but I'd be glad to play along any at all.

Mournful Congregation has a track called "The Rubaiyat" in which they sing translations of Hakim Omar Khayam's Rubaiyat -- short poems in a certain style. This makes them so respected in my heart, as I love Omar Khayam and we read those poems here as they are in native Old Persian. I'd like to play an opener for them.

Follow The Band

Get The Music

#D&S Interviews#Roaring Empyrean#Tehran#Iran#Atmospheric#Doom#Funeral Doom#Instrumental#Doomed & Stoned

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

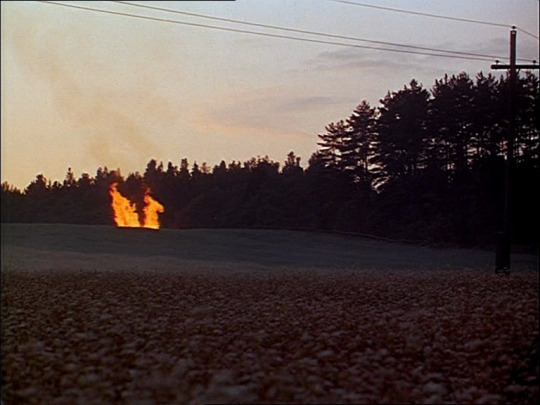

“Is She Real?” and Other Distant Dreams within Dreams: Fifteen Films Which Are Completely Their Own Thing

There are films which stick to one’s mind due to their greatness as well as those which do the same for their extreme inferiority. Mediocre films have a tendency to leave one’s mind like an uneventful day once the night falls. Then there are films which one keeps coming back to because they are completely their own thing. These are films which stay in memory due to their striking originality. They might be masterpieces, and thus greatness could be among the explanans for the phenomenon of preservation, but they do not have to be. In terms of quality or personal preference, these films might be somewhere in the middle. They elude the nightfall of oblivion on other grounds. Although their survival of the test of time can thus be explained by reference to uniqueness, it should be emphasized that uniqueness in this case does not mean any conventional weirdness or doing the extraordinary. The notion I am interested here is not what you might call in-your-face uniqueness (feel free to insert a list of contemporary “indie” directors). Rather, I am interested in the unique unique. I am talking about films which stay with you, but you can’t really point your finger at them and say why; they stay with you not because of quirkiness, of artistic mastery, of historical significance, of intricate story or peculiar characters, but because of an utterly original approach to cinematic discourse -- which might, of course, include all of these to altering degrees. Such originality might be less obvious, but it is there, it is real, and it is singular.

The following list of fifteen unique films will not include the obvious candidates from the first films which did this or that to the weird-for-the-sake-of-being-weird adventures. I have tried to resist the urge to go where the fence is lowest and make a list of “weird movies”; instead I have tried to focus on a more subtle notion of uniqueness. The challenge as well as the allure of list-making are the constant limitations one sets for oneself. That is also the reason why no director pops up twice in the list. Another yardstick for a unique film of this kind is that the film in question cannot really be compared to anything else. Or if it can, the comparison remains loose at best. Hence the absence of films from auteurs whose bodies of work form distinct unique wholes but precisely as wholes, not singular parts. Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Pierre Melville, Robert Bresson, Douglas Sirk, Howard Hawks, Yasujiro Ozu, Jean Rouch, Michelangelo Antonioni, you name it. All of them managed to craft an original cinematic discourse, but they developed the execution of that discourse in countless films that form an admirable whole of aesthetic consistency.

So, here, I am not interested in cultural peculiarity, a director’s originality, or uniqueness within a genre. I am interested in a slightly different kind of personality with regard to cinematic discourse. Although each of the following fifteen films exemplifying this unique uniqueness obviously belong to a director’s oeuvre, I believe that all of them stick out in one way or another. They have not been listed in order of personal preference or quality but in terms of uniqueness (which is, of course, a notion difficult to define, and which is a notion not completely free from personal preference and quality, I’m sure). As such, they tell another story, perhaps unique by nature, about the enigma of the seventh art.

15. Cria cuervos (1976, Carlos Saura, SPAIN)

It is an indescribable delight to witness Carlos Saura’s magnum opus Cria cuervos (1976) unfold before you for the very first time. Since the film, which tells the story about a young girl and her two sisters who try to cope with growing up after the death of their parents, was released one year after Francisco Franco’s death, it has become something of a standard interpretation to watch Cria cuervos as an allegorical tale of "the children of Spain” coping with the loss of their patriarchal leader in a new social reality. Yet any serious spectator will tell you that this is just one side of the film’s multi-layered coin of meanings. Its ambiguous structure might tie in with the prevalent narrative tendencies of Saura’s generation of left-wing Spanish directors, but it also works as a metaphor for the vague human mind. Not only cutting but also panning between the present, the past, and an imagined future, the film unfolds as a poignant story about loss and longing, the desire to be somewhere else, something else, some other time. One of the best films about childhood ever made, Cria cuervos denies romantic innocence without falling into the trap of naive pessimism. It embraces childhood as a part of being human, being mortal, being without something, being toward loss, being as always losing something.

The most famous scene from the film -- and an example of just this -- is definitely the scene where the young girl, played by the unforgettable Ana Torrent, listens to a pop song “Porque te vas” by Jeanette, a nostalgic love song about leaving that reminds the girl of her mother’s death. A touching moment beyond words that can only happen in the cinema, this scene exemplifies beautifully the tendency of children to cling onto seemingly insignificant objects that they will carry with them for the rest of their lives. The images where the girl quietly moves her lips in synchronization with the song are breath-taking and heart-breaking. The way how Saura executes this brief scene, in one sequence shot, is just so original, so inimitable, and so Saura. The emotions are not clearly visible on the child’s face, most likely because she is unable to understand let alone express them, but they come from another place that lies somewhere in between of sound and image. The context for this scene is her frustration with her aunt, who she briefly impersonates (”turn down the music”), which further pushes the obvious meanings and the obvious feelings outside. Maybe it is just a random pop song? What is left is the ambiguity of meaning and feeling. And that resonates. Powerfully. I have never seen anything quite like it. These are unique images which speak loudly about the power of cinema. Some might say that what makes Cria cuervos as unique as it is are Ana Torrent’s dark button eyes, but, in reality, it is how Saura frames them, how he lights them, and how he cuts from them. Cria cuervos has no single detail which would exhaust Saura’s style; yet his sense of composition, his choice of shot scale, his sense of color, sound, and movement are in every second of the film; they are characterized by the subtlest nuances which distinguish an ordinary beautiful object from a true work of art.

14. Nema-ye Nazdik (1990, Abbas Kiarostami, IRAN)

Abbas Kiarostami’s penchant for meta-cinematic discourse, which addresses enduring human themes through postmodern questioning of the possibilities of representation, reaches a peak in Nema-ye Nazdik (1990, Close-Up). Based on true events, it tells the peculiar story about a poor Iranian man, Hossain Sabzian (played by himself, like all the performers in the film) who pretended to be the famous Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf for the Ahankas, an upper-class Iranian family to whom Sabzian told that he wanted to use them and their house for his next film. When Sabzian’s hoax was revealed, the Ahankha family sued him only to drop charges after Sabzian’s intentions proved out to be more complex than those of a traditional impostor. Kiarostami mixes documentary footage with staged scenes of what happened to the extent that it is impossible for the spectator to make a distinction. Not because of slyness, or Kiarostami’s talent to cover his tracks, but precisely because the distinction disappears: when the people involved are placed in front of the camera, acting out what has happened in the not-so-distant past, there is no longer a sense of staging but of being.

In a marvelous moment of poetic intuition and cinematic genius, Kiarostami’s camera picks up an empty spray can rolling downhill on asphalt. In the spirit of the “phenomenological realism” of the Italian neorealists, Kiarostami’s objets trouvés, like the empty spray can, are not symbols for something else. It might be juicy to see meaning written in the code of the empty spray can, say, in terms of the looming void behind the roles we all play, but Kiarostami’s camera uncovers it as a mere abandoned tool. Heidegger would call it Vorhanden, a being present-at-hand, whose factual existence is obvious to us after it has lost its functional purpose in its appropriate context, its primordial being as Zuhanden, a being ready-to-hand that one surrounds oneself with in the everyday reality of practical life. Even if this coarsely rolling empty spray can was the postmodern alternative to Sisyphus’ rock, it would be more a metonymy than a metaphor. It is a desolate, cast-off tool whose lonely mundane being paradoxically charms us in its banality. It is, what we might call in the spirit of anticipation, the taste of cherry.

Here, in the peculiar zone between metaphor and metonomy, meaning and the lack of it (or independent meaning), inhabited by empty spray cans, lies the uniqueness of Nema-ye Nazdik. There is nothing holy or sacred in Kiarostami’s images. The material density of the rough texture of the depicted reality drains from them. The close-ups of the film -- whether in actual shot scale or in narrative intimacy achieved by precisely restrictive framing and extensive use of the off-screen space -- startle us with this banality of the facticity of being and the phenomenal surface of reality. The final close-up of the film shows us Sabzian, looking down, holding a bouquet at the gate of the Ahanka residence where Makhmalbaf has taken him to make amends. One senses the Chaplinesque tragedy of life in close-up. It is tragic because there is no comfort from contextualization; there is a factual detail thrown at us in its strange existential disclosure. A rolling empty spray can or a structured identity at ruins -- revealed, stripped, naked. The human theme of longing coalesces with the meta-cinematic theme of the possibility of representation as one feels the unquenchable thirst for escape, the yearning to be someone else in this banal world of objects-at-present. Where else in the cinema does one find all of this?

13. The Wrong Man (1956, Alfred Hitchcock, USA)

Although Hitchcock is definitely a genre director, meaning that he really devoted his whole career to the genre of suspense (whether in thriller, horror, espionage, or adventure), he made a lot of films which pushed the limits of genre aesthetics, conventional narration, and classical style toward unexplored territories in the land of film. Hitchcock’s legacy is in fact constituted precisely by his relentless desire to look for new ways of cinematic expression. The most obvious example would probably be the “trilogy” in which Hitchcock tested -- and, perhaps to popular opinion, failed -- the slow aesthetics of the long take: Rope (1948), Under Capricorn (1949), and Stage Fright (1950). Their uniqueness is admirable, and the two latter border on masterpiece, but the most unique of Hitchcock’s films is, I believe, The Wrong Man (1956).

If Hitchcock, the great manipulator of his audience whose “buttons” he loved to push, is placed in the group of directors who mastered formalist montage over realist mise-en-scène, following a heavily Bazinian distinction, we might conclude that The Wrong Man is the closest Hitchcock ever got to cinematic realism. Although the film does manipulate the spectator, guiding their gaze throughout rather than giving them the freedom of deep focus and multiplanar composition (the cardinal virtues of Bazin’s theory), its austere mise-en-scène, economic narration, and minimalist editing make it Hitchcock’s most Bressonian film. Interestingly enough, and this will bring us to the film’s uniqueness in a moment, Hitchcock’s biggest fan and André Bazin’s most famous disciple, François Truffaut first expressed great appreciation for The Wrong Man when it came out and later disowned the film in his famous interview book with Hitchcock [1].

The passage where Truffaut challenges Hitchcock, not in order to humiliate him but in order to get him to defend his artistic choices, is among the best parts of the whole interview book. Their discussion concerns the scene where the protagonist, played by Henry Fonda, is taken to his prison cell where he does not belong to because he really has not committed the crime he is being accused of committing. There is no dialogue or voice-over narration to tell us what the character is going through, but Hitchcock’s cinematic narration still visually focalizes into his internal, first-person point of view, while switching to an external, non-focalized third-person perspective in medium shots of the character in captivity. Hitchcock cuts between these medium close-ups of the character’s face as he is looking at something and point of view shots of the austere cell that serves as the object of his gaze. There is no music, no sound -- just stark images of a narrow, grey space. The calm cutting between these two types of shots manages to reflect the character’s inner life which becomes, so to speak, externalized by cinematic means. It is as though his mind extended to the space whose austerity became to articulate his experience of imprisonment, isolation, and, ultimately, loss of self. The non-subjective space turns subjective; its concrete features start to channel the character’s mental states in ways which contemporary directors like Lucrecia Martel have mastered.

The problem Truffaut has with the scene is its ending. The scene concludes with a medium shot where the protagonist leans against the wall of his cell, eyes closed, distraught, powerless. Suddenly, non-diegetic music starts playing on the soundtrack and the camera begins swirling in a circular loop around the character. As the movement of the camera accelerates, the music intensifies and finally reaches a crescendo coinciding with a fade-to-black to the next scene. Truffaut disliked this shot because it seemed to break with the Bressonian asceticism that Hitchcock had been practicing prior to it. It is also noteworthy to add that never again is there anything like this in the rest of the film (and thus the shot does break against the norm of consistency): The Wrong Man returns to its minimalist, Bressonian roots, letting go of the striking expressivity of such camera movement (which is not used to follow a character or reveal further details of narrative significance in the diegetic space). One might recall, for example, the unforgettable shot which dissolves the praying protagonist’s face with the “right man’s” face, and what a completely different feel that shot has to it -- it is something Bresson would never do, but it is something the Bressonian side of Hitchcock does.

Despite Truffaut’s challenge, Hitchcock refused to defend his film, disappointingly noticing that it was not that important to him. That might be the case, but it might also be that Hitchcock was not sure of his artistic choice, or he didn’t know how to explain his intuition, or he didn’t want to argue about such matters. Maybe he thought he had failed in his experiment. Either way, it is this moment which always gets me. It feels a little awkward, and it always pushes me just a little away from the film, to a strange borderline zone of cringe -- but, at the same time, it feels wonderful. It’s the moment where one can so clearly see Hitchcock’s legacy as an innovator and a re-generator, looking for new ways to make films -- and not always with success. It’s the moment when you realize that you are not watching Un condamné à mort s’est échappé (1956, A Man Escaped) but The Wrong Man. It goes against the realist style which avoids blatant and outspoken expression, but it goes so well with Hitchcock’s own style where a sudden cut to an extreme long shot from an extreme high-angle on the top of the United Nations building is completely natural. It’s also one of those moments, definitely alongside the great dissolve of the two faces, where one can sense the presence of cinematic uniqueness. Although I think Un condamné à mort s’est échappé is a better film, there is really nothing like The Wrong Man. From Hitchcock’s startling opening monologue to the inexplicable happy end, bordering on Sirkian irony, The Wrong Man is really its own idiosyncratic thing.

12. Lola Montès (1955, Max Ophüls, FRANCE)

Master director Max Ophüls’ final film and cinematic legacy Lola Montès (1955) is the definitive cult film. It’s strange, it’s wild, and its off-the-rails uniqueness made it a massive flop. It’s the stuff that dreams are made of... the dreams in cult film land. A lavishly told story about a woman with hundreds of lovers, who is now presented to us as a circus attraction, did not resonate with contemporary audiences. With the exception of the new film critics of Cahiers du Cinéma, who were to define the cinema of the following decade, everybody hated the film. To those who understood the magic, however, it was wonderful. To those who still do, it is beyond divine. The combination of box-office and critical failure with a huge budget and an unprecedented desire to challenge convention from the 50-year-old director, who was soon to pass away, turned Ophüls into a martyr figure for the new generation of French filmmakers. Like Orson Welles, Ophüls was -- to them in their own land -- a misunderstood genius, a maestro who died two years after the release of his final film that found too few kindred spirits.

What makes the case of Ophüls’ martyrdom so fascinating is the fact that on paper Lola Montès sounds like everything Truffaut et co. hated. It is based on a novel, its script has other writers in addition to Ophüls, it has an all-star cast (and without the obvious choice, the Ophüls favorite of the 50′s, Danielle Darrieux!), and it has lavish production values backed by a big budget. Does this not sound like le cinéma de qualité par excellence?

The fact that Lola Montès sounds like dull quality cinema on paper, however, does not mean that it looks like it on celluloid. And that’s what makes it unique. Known for his penchant for sumptuously elaborate camera movement (to the extent that a camera which is not moving on tracks simply looks naked in the Ophüls universe), Ophüls went an extra mile to make his forward-tracking dolly shots work in a wide circus arena without revealing the tracks. Resonating with the width of the diegetic space and the volume brought to it by such cinematography, Ophüls also widened his film into color and the CinemaScope aspect ratio for the first time in his career. Unlike anyone prior to him and few after, during a time when CinemaScope had not been around for longer than two years, Ophüls made the unexpected decision to play with the aspect ratio. For most of the screen time, we see the events unfold in 2.55:1, but, every now and then, when mood or character identification so requires, Ophüls narrows the aspect ratio back to the Academy ratio by placing curtains on both sides of the lens. The peculiar technique of altering the aspect ratio within shots in itself is enough to make Lola Montès unique, but the way it connects to the theme of the theater -- not only as the circus milieu but also as the publicization of the private sphere -- and the surprising yet accurate (which never feel too much on-the-nose) choices Ophüls makes in using it turn Lola Montès into a bizarre marvel.

11. Daisy Kenyon (1947, Otto Preminger, USA)

On paper, again, Otto Preminger’s Daisy Kenyon (1947) seems like nothing but a love triangle done to death. Joan Crawford plays a woman who is having an affair with a married man, played by the impeccable Dana Andrews, but in the middle of their troubled affair -- that would suffice to constitute a love triangle -- enters a returning war veteran, played by Henry Fonda (the only actor to appear twice on this list!), who also catches the woman’s eye. The film unfolds as a series of moments which push the female protagonist to the embrace of one man or the other. What makes the film so unique, however, is its original cinematic discourse, its use of style and narration. In his admirably insightful new book on 40′s Hollywood, Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling (2018), professor of film studies, David Bordwell calls Daisy Kenyon “one of the most psychologically opaque films of 1940′s” [2]. Preminger’s cinematic narration is characteristically restrictive of narrative information. There is no voice-over, which would provide the spectator information about the characters’ inner motivations and feelings, but this is only made more ambiguous by the dialogue where the characters keep making contradictory statements about themselves and others. It is difficult to keep track of their mood swings as well as their cognitive discontinuities, and make any cohesive conception of their true motivations and feelings. This was yet to become the dominant characteristic of modern European cinema (mainly Antonioni, above all), but here it blends with classical Hollywood.

The film is filled with strange moments of peculiar, recurring pauses in dialogue which enhance an ambiguity that starts to feel bigger than the characters and their petty worries. Fonda’s character suddenly ends a moment of conversation with Crawford’s by saying “my wife’s dead” without receiving a response of any kind from his romantic interlocutor. Similarly, he nonchalantly proclaims his love to her -- “I love you” -- but gets no response in another passing moment of indifferent quietude. There are no typical responses nor are there typical initiatives. There are only words that try to grab onto something but most often miss their targets that perhaps never even existed.

The lack of conventional non-diegetic music, the use of deep-focus cinematography, deep space compositions, and lingering shots create a mood of emptiness and despair, which reflect a deeper difficulty in expressing oneself. This theme is articulated on the formal level of style and narration, but it also becomes knitted into the story world toward the end when the courtroom sequence plays with the ideas of illogical human behavior and the impossibilities of finding out what people have done and felt. When one of the two men and the Crawford character embrace one another in the film's final shot, it is equally impossible for the spectator to believe that this is the stable, happy end of a typical Hollywood romance. It is merely another dumbfounded pause, another pointless initiative, another unnoticed response, which will soon be followed by quietude, distance, and alienation.

10. Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975, Peter Weir, AUSTRALIA)

Australian director Peter Weir has made a lot of weak films (I am not a fan of the sentimental Dead Poets Society [1989] or the pseudo-intellectual The Truman Show [1998] -- though I do have a little thing for Fearless [1993]), but his breakthrough film, based on the novel by Joan Lindsay, Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) is a real treat. A fictional account of the disappearance of three schoolgirls and their teacher during an all-girls boarding school’s picnic on St. Valentine’s Day in 1900, Picnic at Hanging Rock begins with a quasi-documentary opening text and concludes with an extra-diegetic voice-over discussing the case, making it seem as if the story was true. More than fooling the audience, this device guides them into another world, where something like this might have happened, and into the hypnotic trance of a mystery, all of which is enhanced, of course, by the first images of a foggy landscape and the girl’s words in voice-over:

What we see and what we seem are but a dream, a dream within a dream.

Weir’s greatest film leaves a lasting impression with its unique, impressionist aesthetics of pale colors, quiet sounds, soft focus, lush cinematography, eerie panpipes music, and an often strictly limited field of focus. It is as if the film had been shot through lace or a veil, giving the effect of the faded fantasy image of the romantic belle époque. The final jaded slow-motion shots of the group before the disappearance have an otherworldly quality. They bear a resemblance to impressionist paintings, but the jaded pace of the visual stream of the images emphasizes their mechanic artificiality as though these were paintings made with the first motion picture cameras. Weir’s narrative structure is likewise closer to poetry or painting than to prose as the focalization of the narration is constantly switching, the characters remain a mystery with their inner world and their psychological motives left completely in the dark, the relations between the diegetic events are vague to say the least, and Weir cuts between them in an unconventional fashion. It is nothing short of cinematic uniqueness which stays with the spectator for the rest of their life. One of the most sensitive and clever mystery films of all time, Picnic at Hanging Rock keeps astonishing with its whimsical combination of mystery and reportage, impressionism and mystique, the fantastical and the real.

9. A Canterbury Tale (1944, Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger, UK)

Made in the days of Capra’s wartime propaganda series Why We Fight (1942-1945), whose patriotic spirit spread across the Atlantic to films calling for Anglo-American solidarity, Powell and Pressburger’s A Canterbury Tale (1944) defies tired cliches and patriotic sentiments in its utterly unique rhythm and tone. Taking Chaucer’s classic as an inter-textual framework, A Canterbury Tale focuses on three characters who, on their way to Canterbury, stop at a small village where a mysterious “glue-man” is terrorizing young women who dare to date soldiers. In contrast to most of the wartime productions of the time, Powell and Pressburger’s film turns its gaze from the grandiose to the minuscule, a small village that is unafraid to show its quirky silliness but as such grows into a metaphor for western civilization.

One of the famous director duo’s biggest critical and commercial flops, A Canterbury Tale defies easy classifications. What makes the film unique in a timeless sense lies in its tone and rhythm that are hard to describe. The set-up could mark the beginning of a frivolous farce, and the film is definitely not lost on moments of genuine hilarity, but, as a whole, A Canterbury Tale develops toward the area of peculiar pathos, humanistic tenderness, and profound melancholy. The mythic and the mundane, the romantic and the realist, the everyday and the sublime, the eternal and the transient all find their strange fusion in the film’s rendez-vous of distinct tones, moods, and ideas. Classical studio artificiality gets mixed with on-location authenticity, which is characterized by historical uniqueness as the contemporary spectator realizes that these places are no longer there, creating a tone like no other. In terms of rhythm, the film is always flowing without a hurry, yet never too slowly to announce itself as different or weird. The film’s uniqueness seems so simple, encapsulated in the smallest of things (the co-presence of the past and the present, the smell of the countryside that is imagined through the images, the allure of the any-space-whatevers), but it is so difficult to describe let alone achieve. It must be seen to be believed...

8. Dong (1998, Tsai Ming-Liang, TAIWAN)

The late 1990′s attracted some filmmakers to imagine eschatological scenarios and project them on the big screen. The approaching arrival of the new millennium generated visions of both anxiety and hope, but man’s relentless tendency toward end-of-the-world nightmares drew him closer to the former. These cinematic efforts on the brink of the new millennium usually vary between downright awful (Armageddon, 1998; End of Days, 1999) and surprisingly tolerable (12 Monkeys, 1995), but Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-Liang’s -- who had made a reputation for himself with the understated tale of eroticism Ai qing wan sui(1994, Vive L’Amour), whose final shot in itself might earn its own prize of uniqueness -- Dong (1998, The Hole) shows not only genuine originality and imagination before new times but also a unique tonal combination of both emotions associated with the historic transition: fear and hope.

These emotions are tied together in the film’s thematic nexus of encountering something new, a theme that is treated by Ming-Liang appropriately in an utterly novel fashion. The story takes place in a block of flats in the semi-urban outskirts of a Taiwanese city where people live in quarantine due to the lack of clean water, a problem that has some dire consequences, fitting for the new millennium: without water, people turn into cockroach-like entities that crawl in the dark spaces of moist dirt and dry trash. Two people, a man and a woman, who try to survive in this situation, are united when a hole appears on the man’s floor (being the woman’s roof) due to plumbing renovations. This hole, which is both physical and emotional -- concrete to the point that we can sense its material urgency and abstract to the point that words are not enough to express it -- begins to generate unprecedented intimacy between the two. The characters rarely communicate. At best, they might yell at each other when the woman, the neighbor beneath, finds her ceiling leaking. But there is a more tender connection, one that cannot be expressed by them. In a stroke of charming genius, Ming-Liang uses 50′s-style musical sequences, where well-dressed characters sing Grace Chang’s songs and perform dance numbers that convey the introverted characters silent feelings in a manner that obfuscates more than it clarifies (there is no aha-moment tailored for the spectator). As these musical sequences take place in the same desolate urban spaces where the characters exist, Ming-Liang’s realist aesthetics of the long take, deep space compositions, and a detailed naturalist mise-en-scène of faded colors and flickering lights are challenged by romantic artifice. The space, which turns into its own character, starts dreaming. It dreams of becoming something else, somewhere else, far and away, safe from the arrival of the new.

As the world prepares for never-before-seen destruction, the holes in the characters’ souls become tangible in the form of a narrow gap, not only the grey chasm between the two apartments but also the distinction between these two diegetic dimensions (the world of song and the world of silence). As the new both anxiety-inducing and hope-awakening millennium approaches, the two characters encounter love, something they had not expected, something they had forgotten, something that appears in a totally unprecedented form -- to them as well as to us, the audience. This unique story provides us with an interlude to reflect. Where are we going? New times are coming. We can always look back to the past. We can find solace in its embrace. What is collapsing? What can be recovered? What will the abyss of the hole engulf? And what will it bring about in times of chaos? A new connection, a new intimacy, a new cinema?

7. Herz aus Glas (1976, Werner Herzog, GERMANY)