#it was very well advertised and telegraphed through the narrative

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

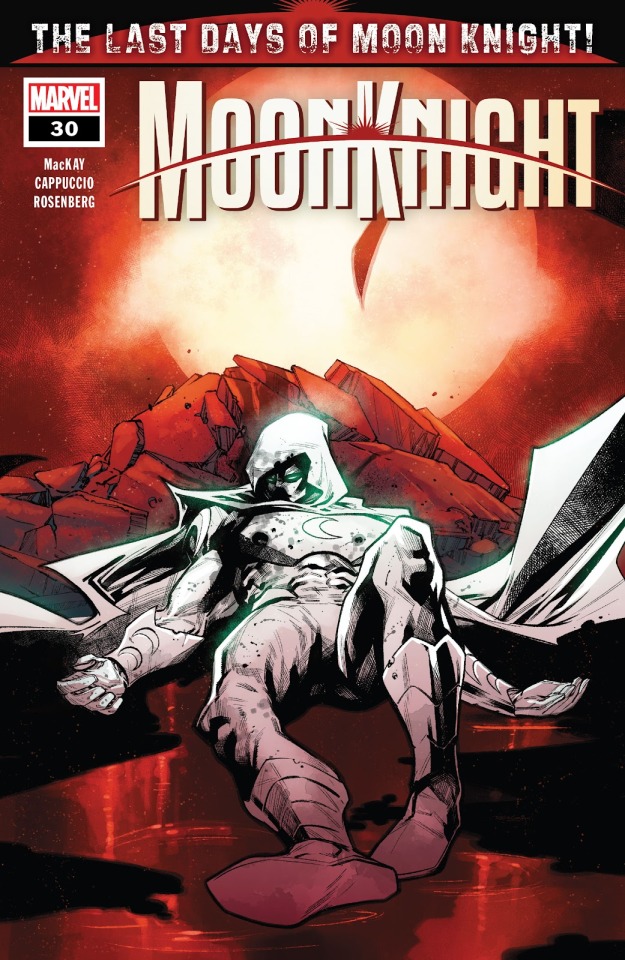

“The Terminal Seconds of Moon Knight,” Moon Knight (Vol. 9/2021), #30.

Writer: Jed MacKay; Penciler and Inker: Alessandro Cappuccio; Colorist: Rachelle Rosenberg; Letterer: Cory Petit

#Marvel#Marvel comics#Marvel 616#Moon Knight vol. 9#Moon Knight 2021#Moon Knight comics#latest release#let’s get this bread#Moon Knight#Marc Spector#first and most critically since I haven’t had a chance to say it yet: Happy Hanukkah!#it’s my hope that you have a lovely and safe holiday where ever you are!#secondly: hey what the heck is this in this comic (quite possibly the worst Hanukkah gift I’ve ever received)#to quit with the melodrama - like sure we saw this coming#it was very well advertised and telegraphed through the narrative#but still…ouch#I do love all things Moon Knight (so I’ll definitely be covering the new Vengeance of the Moon Knight volume#as well as that upcoming Timeless comic two weeks from now#which looks like it’ll have a Moon Knight in it) but…I think it’s pretty obvious that I’m rather partial to Steven Marc and Jake#I’ve been around the block with comics long enough to know that they’ll bring the boys back /eventually/#as only Uncle Ben (not even Bucky or Jason Todd) stays dead in comics#it’s just a bit of a gamble when that return will be :’) (;д;)#like for example I haven’t seen much in the way of interest in bringing Robbie Reyes back since Jason Aaron chucked him into purgatory#and goodness knows we haven’t seen hide nor hair of Nate Grey since that whole Age of X-Man debacle#and while Kaine gives me hope since he returned to comics after being MIA for a decade he’s also in a bit of a content desert at the moment#but hey…that’s comics babey#just gotta enjoy the ride where you can

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

maybe you or one of you followers has access to the telegraph article about Harry "Why does the world want Harry Styles to be gay" I don't know what to think about this headline and I really want to read it but its online only for subscribers

Here you go, Nons. (I hesitate to post this but…)

When Harry Styles played the O2 Arena in 2018, his fans illuminated the cavernous venue in the colours of the LGBTQ Pride flag. Coordinated by a social media account called The Rainbow Project, each seating block was allocated a different colour, so that when Styles played the song Sweet Creature, an enormous rainbow emerged from the crowd. I was there, and it was pretty magical. But it was also emblematic of how Styles’s fanbase views their idol: as a queer icon.

There’s arguably never been a better time to be an LGBTQ pop star. Acts such as Sam Smith, who came out as non-binary earlier this year, Lil Nas X, the first gay man to have a certified diamond song in America, Halsey, queer boyband Brockhampton, pansexual singer Miley Cyrus and Kim Petras, who is transgender, have all enjoyed an incredible year, bagging the biggest hits of 2019.

Still, when Styles shared Lights Up, the lead single from his forthcoming second solo album Fine Line, there was a collective intake of breath. The song and video - in which he appears shirtless in what looks like a sweaty orgy as both men and women grab at him - was heralded as a “bisexual anthem” by the media and fans on Twitter, despite not really making any explicit or obvious statements about sexuality or the LGBTQ community. Instead, Lights Up was just another example of the queer mythologising that occurs around Harry Styles.

As a member of One Direction, Styles was – aside from Zayn Malik – the group’s most charismatic and enticing member. From his first audition on The X Factor to the band’s disbandment in 2015, the teenager from Cheshire managed to elevate himself and his celebrity swiftly rose to the A list. Helping him along was speculation about his private life: during his tenure in the band he was romantically linked to everyone from Taylor Swift to Kendall Jenner.

But there were two other rumoured relationships that dogged Styles more than the others. The first was his close friendship with radio DJ Nick Grimshaw. Styles and Grimshaw were often photographed together, and there were anodyne showbiz reports about how they even shared a wardrobe.

Inevitably, rumours suggested they were romantically linked. In fact, so prolific was speculation that during an interview with British GQ, Styles was asked point blank if he was in a relationship with Grimshaw (he denied any romantic relationship) and, in a move that upset many One Direction fans, if he was bisexual. “Bisexual? Me?” he responded. “I don’t think so. I’m pretty sure I’m not.”

The second, and perhaps most complicated of rumours, was that he and fellow bandmate Louis Tomlinson were in a relationship. Larry Stylinson, as their shipname is known, began life as fan-fiction but mutated into a wild conspiracy theory as certain fans – dubbed Larries – documented glances, gestures, touches, interviews, performances and outfits in an attempt to confirm the romance. Even now, four years after the band went on “hiatus”, videos are still being posted on YouTube in an attempt to confirm that their relationship was real.

For Tomlinson, Larry was fandom gone too far. He has repeatedly rejected the conspiracy. Styles, meanwhile, has never publicly discussed it. In fact, unlike Tomlinson, whose post-1D career trajectory has seen him adopt a loutish form of masculinity indebted to the Gallagher brothers, Styles has largely leant into the speculation surrounding his sexuality. Aside from the GQ interview, Styles has told interviewers that gender is not that important to him when it comes to dating. In 2017 he said that he had never felt the need to label his sexuality, adding: “I don’t feel like it’s something I’ve ever felt like I have to explain about myself.”

Likewise, during his time touring with One Direction, and during his own solo tours, the image of Styles draped with a rainbow flag became ubiquitous. He has also donated money from merchandise sales to LGBTQ charities. His fashion sense, too, subverts gender norms: Styles has long sported womenswear, floral prints, dangly earrings and painted nails.

Nevertheless, Styles’s hesitance to be candid has met with criticism. He has been accused of queer-baiting - or enjoying the benefits of appealing to an LGBTQ fanbase without having any of the difficulties. I’ve written before about how queer artists, who now enjoy greater visibility and are finding mainstream success, have struggled commercially owing to their sexuality or gender identity.

Styles, who is assumed to be a cisgender, heterosexual male, doesn’t carry any of the commercial risk laden upon Troye Sivan, Years and Years or MNEK, who all use same-gender pronouns in their music and are explicitly gay in their videos. His music – with its nods to rock’n’roll, Americana and folk – doesn’t feel very queer, either. Looking at it this way, the queer idolisation of Harry Styles doesn’t feel deserved.

“The thing with Harry Styles is that he often does the bare minimum and gets an out-sized load of credit for it,” says songwriter and record label manager Grace Medford. For Medford, who has worked at Syco and is now part of the team at Xenomania records, Styles’s queer narrative has been projected on him by the media and his fans. “I don’t think that he queer-baits, but I don’t think he does anywhere near enough to get the response that he does.”

Of course, Styles does not need to explain or be specific about his sexuality. As Medford puts it: “he’s well within his rights to live his life how he chooses.” However, he has also created a space for himself in pop that allows him that ambiguity.

It’s a privilege few pop stars have. Last year, Rita Ora was hit with criticism after her song Girls, a collaboration with Charli XCX, Cardi B and Bebe Rexha, was dubbed problematic and accused of performative bisexuality. Even though Ora explicitly sang the lyric “I’m 50-50 and I’m never gonna hide it”, she was lambasted by social media critics, media commentary and even her fellow artists until she was forced to publicly confirm her bisexuality.

But the same was not done to Styles when he performed unreleased song “Medicine” during his world tour. The lyrics have never been confirmed, but the song is said to contain the line: “The boys and the girls are in/ I mess around with him/ And I’m okay with it.” Instead of probing him for clarity or accusing him of performativity, the song was labelled a “bisexual anthem” and praised as “a breakthrough for bisexual music fans”.

Of course, there’s misogyny inherent to such reactions. But there’s also something more layered and complex at play, too. “There’s such a dearth of queer people to look up to, especially people at Harry’s level,” posits Medford. “With somebody who is seen as cool and credible and attractive as Harry, part of it is wishful thinking, I think.

“The fact is, he was put together into a boyband on a television show by a Pussycat Doll. And he has rebranded as Mick Jagger’s spiritual successor and sings with Stevie Nicks; he’s really done the work there. Part of him doing that work is him stepping back and letting other people create a story for him.”

One only has to look at how Styles’ celebrity manifests itself (cool, fashionable, artistic) in comparison to that of his former bandmates. Liam Payne (this week dubbed by the tabloids as a chart failure) has been a tabloid fixture since his public relationship with Cheryl Cole and relies on countless interviews, photoshoots and even an advertising campaign for Hugo Boss to maintain his fame.

Styles, meanwhile, doesn’t really engage with social media. He also rarely appears in public and carefully chooses what kind of press he does, actively limiting the number of interviews he gives. Styles’s reticence to engage with the media and general public – perhaps a form of self-preservation – has awarded him a rare mystique that few people in the public eye possess.

This enigmatic personal, along with his sexual ambiguity, his support of LGBTQ charities and his gender-fluid approach to fashion, creates the perfect incubation for queer fandom. It also provides a shield against serious accusations of queer-baiting. As Medford argues: “Harry’s queer mythology has been presented to and bestowed upon him by queer people whereas other acts feel like they have to actively seek that out.”

Ultimately, the way that Styles navigates his queer fandom doesn’t feel calculated or contrived. For Eli, an 18-year-old from Orlando who grew up with One Direction, seeing Styles “grow into himself” has been important. He suggests that Styles’ queer accessibility has helped to create a safe space for fans. “Watching him on tour dance on stage every night in his frilly outfits, singing about liking boys and girls, waving around pride flags, and even helping a fan come out to her mom, really helped me come to terms with my own sexuality,” he explains.

Vicky, who is 25 and from London, agrees: “To be able to attend his show with my pansexual flag and wave it around and feel so much love and respect - it’s an amazing feeling. I’m aware so many queer people can’t experience it so I’m very grateful Harry creates these safe spaces through his music and concerts.”

There’s appeal in Styles’s ambiguity, too. Summer Shaud, from Boston, says that Styles’ “giving no f—-” approach to sexuality and gender is “inspiring and affirming” for those people who are coming to terms with their own identities or those who live in the middle of sexuality or gender spectrums. “There’s enormous pressure from certain gatekeeping voices within the queer community to perform queerness in an approved, unambiguous way, often coming from people with no substantive understanding of bisexuality or genderfluidity who are still looking to put everyone into a box,” she argues. “Harry’s gender presentation, queer-coding, and refusal to label himself are a defiant rebuke of that “You’re Not Doing It Right” attitude, and that resonates so strongly with queers who aren’t exclusively homosexual or exclusively binary.”

Shaud says that the queer community that has congregated around Styles is another reason she’s so drawn to him. “Seeing how his last tour was such an incredible site of affirmation and belonging for queers is deeply moving to me, and as older queer [Shaud is 41] I’m so grateful that all the young people growing up together with Harry have someone like him to provide that.”

In fact, she argues that there’s a symbiotic relationship between Styles and his queer fans. She cites an interview he gave to Rolling Stone this year in which he said how transformative the tour was for him. “For me the tour was the biggest thing in terms of being more accepting of myself, I think,” Styles shared. “I kept thinking, ‘Oh wow, they really want me to be myself. And be out and do it.’”

All of the queer Harry Styles fans I spoke to agreed that it really didn’t matter whether their idol was explicit about his sexuality or not. “It’s weird that people scrutinise people who don’t label [their sexuality] when they have no idea what that person feels like inside or, in Harry’s case, what it’s like to be under the public eye,” argues Valerie, who is 18. “It’s an individual choice, not ours,” agrees Vicky.

Ollie, 22 and from Brighton, takes a more rounded view, however: “On one hand, I think that quite simply it isn’t any of anyone else’s business. On the other, if you place yourself in the public eye to the level of fame that he has then you should be prepared to be probed about every minute detail of your personal life, whether you like it or not – you should at least be prepared to be questioned about it.” Still, he says that the good that Styles does is what’s important: “He brings fantastic support and attention to the community, whether he is actively a part of it or not.”

Arguably, the ambiguity and mystery that surrounds Styles only allows more space for queer people to find safety in him and in the fandom.

Still, if fans are expecting a queer coming of age with new album Fine Line, they will be disappointed. Lyrically, he doesn’t venture into new territory, although there are some new musical flares. He also seems like he’s started to distance himself a little from the ambiguity, too. “I’m aware that as a white male, I don’t go through the same things as a lot of the people that come to the shows,” he told Rolling Stone. “I can’t claim that I know what it’s like, because I don’t. So I’m not trying to say, ‘I understand what it’s like.’ I’m just trying to make people feel included and seen.” Having said that, within weeks Styles appeared on Saturday Night Live playing a gay social media manager, using queer slang and even wearing an S&M harness.

And so the cycle of queer mythologising continues, and is likely to continue for the rest of Styles’s career. And maybe things will change and maybe they won’t.

“If you are black, if you are white, if you are gay, if you are straight, if you are transgender — whoever you are, whoever you want to be, I support you,” he said earlier this year. “I love every single one of you.” In a world where LGBTQ rights are threatened and there’s socio-political insecurity, perhaps, for now at least, that’s enough.

#I hope it goes without saying that I disagree with a LOT in this article#telegraph#not sure how else to tag this#asks#Anonymous

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Toxic positivity': Is there a dark side to self-help?

The Sussexes are the latest A-listers to follow Dr Brené Brown, the 'world’s biggest self-help guru' – but is her form of therapy effective?

By Miranda Levy

26 August 2020 • 6:00am

Dr Brené Brown has been described as the “world’s biggest self-help guru”

Until this weekend, the Harry and Meghan mental health effort had largely passed me by. I knew they had supported various causes and started a charity (The Royal Foundation? Archewell? Working out the politics of what it was called was reminiscent of the Monty Python’s People’s Front of Judea.)

Back in October, I did attempt to watch the documentary Harry & Meghan: An African Journey, until I’m afraid those sciroccos of self-pity forced me to switch off after 20 minutes.

But then, on Sunday, I was flicking through a newspaper when four quotations next to a photo of the Sussexes almost made me inhale my raisin bran.

“You either walk into your story and own your truth, or you live outside of your story, hustling your worthiness,” said one.

Then: “Vulnerability is not winning or losing; it’s having the courage to show up... when we have no control over the outcome.”

Advertisement

I was almost having a seizure by the time I read: “Only when we are brave enough to explore the darkness will we discover the infinite power of our light.”

The quotes were attributed to one Brené Brown. Dr Brown, a research professor at the University of Houston, has been described as the “world’s biggest self-help guru”. She has written a number of bestselling books, including The Gifts of Imperfection, Daring Greatly, Rising Strong, Braving the Wilderness, and Dare to Lead. And she has an A-list following including Reese Witherspoon and Jennifer Aniston. Gwyneth Paltrow has called her “one of the most influential people in our culture.”

Reese Witherspoon is a fan of Dr Brené Browns teachings Credit: private/CAPITAL PICTURES/private/Twitter

Now, she can count the Sussexes amongst her disciples. During a video call with the Queen’s Commonwealth Trust last week, Prince Harry revealed that the couple know Dr Brown, adding that they “absolutely adore” her. She wrote an essay on the cruelty of online comments, called ‘Speak Your Truth. Follow Your Wild Heart’, when Meghan guest-edited Vogue last year.

Of course, it’s not new for the stars to follow a spiritual guide. Perhaps the original was the Beatles’ Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (“guru” does, after all, mean “spiritual teacher” in Hindi). Princess Diana had Susie Orbach, who told us to “dare to be as physically robust and varied as you always were.” Battling it out with Dr Brown in the modern compassion-for-sale stakes is Glennon Doyle, a 44-year old former “Christian mummy blogger” and now a “thought leader” in the “inspiration industry”. Doyle’s book Untamed - a memoir of her struggles with bulimia and other mental health issues - hit the headlines this month, after the singer Adele wrote on Instagram: “this book will shake your brain and make your soul scream.”

Glennon’s 2013 TED talk ‘Lessons from the mental hospital” has been viewed three million times. Dr Brown’s own TED talk on “the power of vulnerability" has been viewed 50 million times.

So why am I such an out-of step curmudgeon?

A Telegraph reviewer called Untamed “jaw-clenchingly earnest,” and perhaps that's where it starts for me: the complete lack of humour and self-awareness in this psycho wafflespeak. And while it feels slightly out of date to talk about the British stiff upper-lip (though, compared with Californians, most Brits are as stoical as Marcus Aurelius), we do tend to laugh at ourselves, and salve pain with silly self deprecation, which is all quite un-American. We also love a good moan. Relentless optimism is exhausting. But my abhorrence towards this sort of twaddle somehow runs more deeply than that.

Thankfully, some people across the Atlantic seem to agree. Natalie Datillo, a clinical psychologist based in Boston, has a good term for it: “toxic positivity”.

“While cultivating a positive mind-set is a powerful coping mechanism, toxic positivity stems from the idea that the best or only way to cope with a bad situation is to put a positive spin on it, and not dwell on the negative,” she says.

I decide to canvass the opinion of an expert closer to home. Anthony Stone was my psychotherapist during a really bad period of my life about seven years ago. We are now friends. Stone is something of a Yoda-type figure in Hampstead Garden Suburb (no easy feat in a north London postcode that has more therapists than civilians) and probably the most spiritual person I know. He’s unfamiliar with Brené Brown, so I direct him to the “hustling your own worthiness” quote.

“What the f--- does that mean?” he asks.

Stone says these mantras are: “cheap shots, facile phrases that are just trotted out. They are not directed to the soul,” he says. “Therapy is all about change, and for a person to change, you have to touch their life force.” Stone calls the TED talks “extraordinary. This behaviour is the quintessence of narcissism. What sort of person wants to stand up in front of hundreds of people and reveal all?”

He continues: “I remember a supervisor of mine saying to me ‘if you think you have wisdom, forget it, you have no idea’, and he was right. Changing your life is hard work - as you well know.”

And I do know well. Perhaps my own experience comes into all my reaction to all this, because for several years in the 2010s - after a relationship breakdown, terrible insomnia, and resultant depression - I had my own brush with the world of “therapy”. At the sharp end. The real business of proper mental illness is tough, and mucky. At my very worst, in 2014, I spent five days in an NHS psychiatric hospital. Patients were double-locked in a fetid ward with the occasional shrieks from someone being forcibly-injected. You got 15 minutes of “fresh air” twice a day in a yard that resembled a large ashtray, so many cigarettes were lying around. I “slept” on a tiny bed with a rubber pillow, under a light that flickered all night long.

The ward smelt of cabbage, rather than Gwyneth Paltrow’s vagina candles. Therapy was almost non-existent. “Walking into our story” was certainly not encouraged.

Dr Brown’s pronouncements - and those who revel in them - just seem so… privileged. I know that word is bandied around everywhere these days, but Harry, Meghan, Oprah (another fan) and the denizens of Santa Barbara really don’t have it so tough. Natalie Datillo seems to agree. “Looking on the bright side in the face of dire situations like illness, homelessness, unemployment or racial injustice is a privilege that not all of us have,” she says.

Added to this, a 2018 study from the journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that people who habitually avoid acknowledging challenging emotions can end up feeling worse. “Accepting negative emotions, rather than just avoiding or dismissing them, may be more beneficial in the long run,” said lead author Brett Ford, an assistant professor as the University of Toronto, “People who tend not to judge their feelings and not think about their emotions as ‘good’ or ‘bad’, tend to have better mental health across the board.”

Brené Brown talks of “owning our story and loving ourself through the process.” Stone says that seeing your life as narrative can be helpful, but there are no silver bullets. “In my therapy groups, I have people who have made enormous strides, but over the course of years,” he says. “Meaningless words won't cut it."

0 notes

Text

Run ragged

It didn’t work. And while I wasn’t surprised by that, I did want to tease out why, at least for myself.

I honestly was openly skeptical of Blade Runner 2049 for a while, so I can’t hide my bias there. I wasn’t totally ‘salt the earth and never mention it again’ then and am certainly not saying that now. But each new trailer left me feeling more ‘uh...really?’ and the explosion of immediate praise from many critics even more so. I wasn’t contrarian, and neither did I think groupthink was at work, but I suspected a massive wish fulfillment was.

So I generally avoided reactions after that and figured I’d wait for things to die down a bit -- even more quickly than I might have guessed, seeing its swiftly collapsing commercial performance over here. My Sunday early afternoon showing near here was about maybe 2/3 full on its third weekend, so it’s found an audience, but I’m in San Francisco -- I expected an audience there. Enough friends have posted theater shots where they were the only person in the room to know this is dying off as an across the board thing, and never probably was.

I’m not glad it failed, but I’m not surprised -- in fact, being more blunt, I think it deserved not to be a hit. The key reason for me played itself out over its length -- it was boring. It’s a very boring movie. It’s not a successful movie except in intermittent moments.

That said, of course not everyone agreed (I’ll recommend as an indirect counterpoint to my thoughts this piece by my friend Matt, which went up earlier today). And boredom is not the sole reason for me to crucify it -- there were a variety of things one can address. I’ll note two at the start since they could be and in a couple of cases I’ve seen were particular breaking points for others:

* The sexual politics of the movie, however much meant to be in line with the original scenario as playing out a certain logic, were often at least confused or hesitant within a male gaze context, at most lazily vile beyond any (often flatly obvious) point-making. I often got a mental sense of excuses that could be offered along the lines of ‘well...you know, it’s supposed to be like that in this world, it’s a commentary!,’ which is often what I’ve seen in positive criticism of, say, Game of Thrones. Maybe. That said: not that any sort of timing played into it, but the fact that Harvey Weinstein’s downfall began two days before release, and the resulting across-board exposure and on-the-record testimonials from many women against far too many men, couldn’t really be escaped. Further, since the fallout was first felt, after all, in the film industry, seeing any film, new or old, through the lens of what’s acceptable and who gets through what hoops -- and who is broken by the experience -- is always important. It’s not for nothing to note that the original film’s female lead Sean Young got shunted into the ‘she’s crazy’/’too much trouble’ file in later years where male actors might perhaps find redemption; the fact that she played a small part in the new film made me think a bit more on her fate than that of her character’s. (Another point I saw a few women brought up as well -- having a key to the whole story be pregnancy and childbirth as opposed to infertility wasn’t warmly received.)

* It’s a very...white future. Not exclusively, certainly. But people of color barely get a look in, a quick scene here, a cameo there. A black female friend of mine just this morning said this over on FB about the one African American actor whose character got the most lines, saying:

to have the only significant black character be this awful, creepy man who seemed to be an "overseer" type to the children, was really uncomfortable and another perfect example of scifi using an 'other' narratives or american slave narrative but within a white context. We all know what it's supposed to represent and so it's just straight up lazy writing at the end of the day and exploitative.

Meantime, another sharp series of comments elsewhere revolved around how a film perhaps even more obviously drenched than the original in an amalgamated East Asian imaginary setting for the Los Angeles sequences barely showcased anyone from such a background. Dave Bautista certainly makes an impact at the start, but after that? The fact that I can think of three speaking roles for actors of that (wide) background in the original, as in actually having an exchange with a lead character, and only one in this one, maybe two if you count the random shouting woman in K’s apartment building, is more than a little off. Add in a ‘Los Angeles,’ or a wider SoCal if you like, that aside from Edward James Olmos’s short cameo apparently has nobody of Mexican background, let alone Central American, in it, and you gotta wonder. My personal ‘oh really’ favorite was the one official sign that was written in English and, I believe, Sanskrit. Great visual idea; can’t say I saw anyone of South Asian descent either.

Both these very wide issues, of course, tie in with the business and the society we’re all in -- but that’s no excuse. And there are plenty of other things I could delve into even more, not least my irritation over the generally flatly-framed dialogue shots in small offices that tended to undercut the grander vistas, or how the fact that Gosling’s character finding the horse carving had been telegraphed so far in advance that it was resolutely unremarkable despite all the loud music, etc. My key point remains: boring. A sometimes beautifully shot and visually/sonically striking really dull, draggy, boring film.

The fair question though is why I think that. A friend in response to that complaint as echoed by others joked what we would make of Bela Tarr films, to which I replied that I own and enjoy watching Tarkovsky movies. Slow pace and long shots aren’t attention killers for me per se; if something is gripping, it will be just that, and justify my attention. Meanwhile, the original film famously got dumped on for also being slow, boring, etc at the time, and plenty can still feel that way about it. Blade Runner’s reputation is now frightfully overburdened and certainly I’ve contributed to it mentally if not through formal written work; it succeeds but is a flawed creation, and strictly speaking the two big complaints I’ve outlined above apply to the predecessor as much as the current film, it’s just a matter of degrees otherwise. But if you told me I had to sit down and watch it, I’d be happy to. Tell me to do the same with this one, I would immediately ask for the ability to skip scenes.

I’ve turned it all over in my head and these are three elements where things fell apart for me, caused me to be disengaged -- not in any specific order, but I’m going to build outward a bit, from the specific to the general, and with specific contrast between the earlier film and the new one. These discontinuities aren’t the sole faults, but they’re the ones I’ve been thinking about the most.

First: it’s worth noting that the new film brings in a lot of specific cultural elements beyond the famed advertising and signs. Nabokov’s Pale Fire is specifically singled out both as a visual cue and as an element in K’s two police station evaluations, for instance. Meanwhile, musically, I didn’t quite catch what song it was Joi was telling K about early in the film but a check later means it must have been Sinatra’s “Summer Wind,” featured on the soundtrack. Sinatra himself of course shows up later as a small holographic performance in Vegas, specifically of “One For My Baby,” while prior to that K and Deckard fight it out while larger holographic displays of older Vegas style revues and featured performers appear glitchily -- showgirls, Marilyn Monroe, Elvis in his later pomp, Liberace complete with candleabra. All of this makes a certain sense and on the one hand I don’t object to it.

But on the other I do. Something about all that rubbed me the wrong way and I honestly wasn’t sure why -- the Nabokov bit as well, even the quick Treasure Island moment between Deckard and K when they first talk to each other. The answer I think lies with the original film. It’s not devoid of references either, but note how two of the most famous are used:

* When Rutger Hauer’s Roy Batty introduces himself to James Hong’s Hannibal Chew, he does so with a modified quote from William Blake’s America: A Prophecy. (This fuller discussion of that quote and how it was changed from the original is worth a read; it’s also worth noting that Hauer brought it to the table, and wasn’t planned otherwise.) But he doesn’t do so by spelling out to the audience, much less Chew, that it is Blake at all. You either have to know it or you don’t. If, say, we saw Batty clearly holding a copy of the book -- or maybe more intriguing, a copy in Deckard’s apartment -- then that would be one thing...but it becomes a bit more ‘DO YOU SEE?’ as a result. Clunkier, a bit like how Pale Fire worked in the new film.

* Even in the original soundtrack’s compromised/rerecorded form, I always loved the one formally conventional song on the original soundtrack, “One More Kiss, Dear.” I just assumed as I did back in the mid to late 80s, when I first saw the film and heard its music, that it was a random oldie from somewhere mid-century repurposed, a bit of mood-setting. It is...but it isn’t. It’s strictly pastiche, a creation of Vangelis himself in collaboration with Peter Skellern, an English singer-songwriter who had a thriving career in his home country. It just seemed real enough, with scratchy fidelity, a piano-bar sad elegance -- which was precisely the point. You couldn’t pin it down to anything, it wasn’t a specifically recognizable element. It wasn’t Elvis, or Liberace, or Sinatra.

This careful hiding of concrete details -- even when the original film showcased other clear, concrete details of ‘our’ world culturally, but culturally via economics and ads -- is heavily to the original’s benefit, I’d argue. There’s a certain trapped-in-baby-boomerland context of the elements in the new film that, perversely, almost feels too concrete, or forced is maybe a better word. It’s perverse because on the one hand it makes a clear sense, but on the other hand, by not being as tied to explicitly cultural identifiers -- whether ‘high’ literature or rough and ready ‘pop’ or whatever one would like to say -- the original film feels that much more intriguingly odd, dreamlike even. I would tease this out further if I could, but it quietly nags -- perhaps the best way I could describe it is this: by not knowing what, in general, the characters, ‘human’ or not, read, listen to, watch in the original, what everyone enjoys -- if they do -- becomes an unspoken mystery. Think about how we here now talk about what we read, listen to, watch as forms of connection with others; think about how the crowd scenes in the originals feature people all on their own trips or in groups or whatever without knowing what they might know. We know Deckard likes piano, sure, but that suggests something, it doesn’t limit it. We know K likes Nabokov and Sinatra -- and that tells us something. And it limits it.

My second big point would also have to do with limits versus possibilities, and hopefully is more easily explained. Both films are of course amalgams, reflections of larger elements in the culture as well as within a specific culture of film. The first film is even more famously an amalgam of ‘film noir’ as broadly conceived, both in terms of actual Hollywood product and the homages and conceptions and projections of the term backwards and forwards into even more work. It is the point of familiar reference for an audience that at the time was a couple of decades removed from its perceived heyday, but common enough that it was the key hook in -- the weary detective called back for one last job, the corrupt policeman, the scheming businessman, the femme fatale, etc. etc. Set against the fantastic elements, it was the bedrock, the hook, and of course it could be and was repurposed from there, in its creation and in its reception.

2049 is not a film noir amalgam. Instead, it’s very clearly -- too clearly -- an amalgam of exactly the wrong place it should have gotten any influence from. By that I don’t mean the original film -- above and beyond the clear story connections, its impact was expected to be inescapable and as it turns out it was inescapable. Instead it’s an amalgam of what followed in the original’s wake -- the idea of dystopia-as-genre -- and that’s poisonous.

Off the top of my head: Children of Men. The Matrix. Brazil. Her. Battlestar Galactica, the 2000s reboot. A bit of The Hunger Games, I’d say. A bit of Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome (not a direct descendant of the original at all, of course -- George Miller always had his own vibe going -- but I caught an echo still). The Walking Dead. A fleck of The Fifth Element. Demolition Man, even, if we want to go ‘low’ art. But also so many of the knockoffs and revamps and churn. There could be elements, there could be explicit references, there could be just a certain miasma of feeling. But this all fed into this film, and made it...just less interesting to me.

Again, the first film is no less beholden to types and forebears. But the palette wasn’t sf per se, it was something else, then transposed and heightened and made even uneasier due to what it was. 2049 has to not only chase down its predecessor, it has to live with what its predecessor created. But did it have to take all that into itself as well? It becomes a wink and a nod over and again, and a tiring one, a smaller palette, a feeding on itself. And it’s very frustrating as a result, and whatever spell was in the film kept being constantly rebroken, and the scenes kept dragging on.

This all fed into the third and final point for me -- the key element, the thing that makes the original not ‘just’ noir, the stroke of genius from Philip K Dick turned into tangible creations: the replicants, and the question of what it is to be human. Humanity itself has assayed this question time and time over -- let’s use Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as a start if we must for the modern era, it’s as good as any. We as a species -- if we individual members can afford the time and reflection at least -- seem to enjoy questions of what makes us ‘us,’ and what we are and what we have in this universe. This much is axiomatic, so take that as read.

The replicants in the original film -- famously thought of differently by Dick and Ridley Scott, to the former’s bemusement when they met and talked for their only meeting before the latter’s death -- set up questions in that universe that are grappled with as they are by the characters in different ways. Between humans, between replicants, between each other, lines always slipping and shading. Their existences are celebrated, questioned, protested against. But we don’t live in these conversations for the most part, we tend to experience the characters instead; it’s often what’s unsaid that has the greatest impact. And if the idea of a successful story-teller is to show rather than tell, then I would argue that, again, flawed as it can be, the original film succeeds there be only telling just enough, and letting the viewer be immersed otherwise. (Thus of course the famous after the fact narration in the original release insisted upon by the studio, and removed from later cuts to Scott’s thorough relief.)

By default, that level of quiet...I would almost call it ‘awe’...in the original can’t be repeated with the same impact. The bell cannot be unrung, but that’s not crippling. What was crippling was how, again, bored I was with the plight of the characters in 2049. How unengaged in their concerns I generally was. One key exception aside, I never bought K’s particular angst outside of plot-driven functionality, and frankly they often felt like manikins all the way down from there. Robin Wright’s police chief had some great line deliveries but the lines were most often banal generalities that sounded ridiculous. Jared Leto’s corporate overlord, good god, don’t ask. As for Joi and Luv, Ana de Armas and Sylvia Hoeks did their best, and yet the characters felt...functional. Which given the characters as such would seem to be appropriate, but their fates were functional too. Of course one would do that, of course the other would do that, of course one would die the one way, of course the other would die that way, and...fine. Shrug.

So, then, Deckard? Honestly Harrison Ford had the best part in the film and while I found him maybe a bit more garrulous than I would have expected from the character, he did paranoid, wounded and withdrawn pretty damn well. Not to mention comedy -- the dog and whisky combo can’t be beat, and it’s worth remembering his nebbishy ‘undercover’ turn in the original -- and, in the Rachel scene, an actual sense of pathos and outrage. I bought him pretty easily, and it made everyone else seem pretty shallow. When K learns about the underground replicant resistance and all, the bit about everyone hopes they are the one was nice enough, but the rest of it, clearly meant to be a ‘big moment,’ was...again, dull, per my second point about the limited palette. A whole lot of telling, not much showing, and such was the case throughout. It was honestly a bit shocking -- but also very clear -- to myself when I realized how little I cared about humans or replicants or any of it at all towards the end. It all felt pat and played out, increasingly unfascinating, philosophy that was rote. It could just be me, of course -- maybe this is an issue where the stand-ins of replicants versus realities of robots and AI, along with the cruelties we’re happy to inflict on each other, means the stand-ins simply don’t have much of an imaginative or intellectual grip now.

Still, though, I’ll give the film one full scene, without Ford. As part of his work, and to answer the questions in his own head, K visits Ana Stelline, a designer of replicant memories. This, more than anything else in the film outside of certain design and musical elements, felt like the original, or something that could be there. It introduced a wholly new facet -- how are memories created for replicants? -- while extending the idea that instead of one sole creator of replicants there are multiple parts makers with their specialized fields in an unexplained (and unnecessary to be explained) economy. Stelline’s literal isolation allows for space and the limits of communication to be played out in a way that makes satisfying artistic sense, and Carla Juri plays her well. It builds up to an emotional moment that sends K into an explosive overdrive that is actually earned, and Juri’s own reaction of awe and horror is equally good. But -- even better -- the scene ends up taking a wholly new cast later in the film, when more information reveals what was actually at play, and what K didn’t know at the time, and makes the final scene a good one to end on in turn (and by that I mean back in her office, specifically).

The problem though remains -- one scene can’t make a film. One can argue that it’s better to reach and fail than not at all, but it’s also easily argued that one gets far more frustrated with something that could have worked but didn’t. I don’t think an edit for time would have fixed the film but it would have made it less of a slog while not sacrificing those visual/sonic elements that did work; it still would leave a lot of these points I’ve raised standing, but it would have gone down a little more smoothly, at least. But sometimes you’re just bored in a theater, waiting for something to end.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nem Kurutma | Nem Alma | Rutubet Kurutma | DYD 444 0 719

We have been frequently thinking about how precisely better to organise that which we need to state

We have been frequently thinking about how precisely better to organise that which we need to state

flip your presentation format

Conference presentations. We nearly also have one approaching someplace.

Now, there’s a complete great deal discussing seminar https://domyhomework.services presentations and exactly what can make a mistake together with them. People read dull papers. They usually have interminable and defectively designed slides. And additionally they come to an end of the time to have their key point around. You don’t might like to do any one of that. You desire visitors to be interested and also to pay attention.

It is beneficial to consider a seminar presentation to be an account – a tremendously specific kind of narrative – it is an account you will inform a real real time market regarding the work. So just how does the whole tale get?

Well, let’s have a look at exactly what many people do, the educational equivalent of when upon a period… a lot of people have a tendency to provide their empirical work with the exact same purchase that they normally use to write a journal article. They normally use sort of standard IMRaD framework which appears nearly the same as your order of things below.

This format is needless to say definitely fine. absolutely absolutely Nothing incorrect along with it after all. As soon as upon time will bring you going. And also this default framework is exactly what lot of men and women expect you’ll see in a presentation.

However the issue is that for those who haven’t got a whole lot of the time then you can end up rushing by the end to try and create your heavily weighed. You are doing IMR and hurry the advertising.

It is very easy to do. You simply need to spend a few minutes a long time on the literature or concept or practices or in the outcomes, and also you end up abbreviating probably the most thing that is important want your market to learn – your point. Along with your market has received to wait patiently a reasonable time you then race through for you to get to that point which.

One alternative would be to flip your order regarding the narrative. Yes that’s right. Flip it. Get the part of very very very early. Grab your attention that is audience’s right the beginning.

The flipped narrative begins exactly the same way while the standard. You pose your issue or concern and explain why it is crucial. However now, you offer your solution instantly. After this you invest the rest associated with the right time showing your market the manner in which you reached that summary.

As well as the end that is very just require a few momemts to share with individuals whatever they – or someone else – has to do. It is possible to truncate the outcomes pretty effortlessly and proceed the to just what exactly.

When you flip the story, you might well keep down a little regarding the literature work (as above) – and perhaps that is not such a negative thing for a presentation. In the end, folks have started to hear your message that is big the way you surely got to it.

And when you come to an end of the time, at the least individuals understand what you researched and everything you claim, regardless of if they don’t understand all the information regarding exactly how and just why. When they understand the point, in addition to form of the argument, they might very well be more likely to adhere to up afterwards – presenting a lengthy preamble and telegraphing the punch-line may possibly not be therefore conducive to help expand research of one’s work.

Now, message first as above isn’t the way that is only flip a presentation narrative. You could try out different ways of moving the standard order around, taking into consideration the story line it is possible to build with every variation.

We usually do variants in the message first format whenever I’m keynotes that are doing generally weave relevant literatures through my narrative rather than provide them individually. We often perform some issue and practices ahead of the a key point and then explain exactly just just how this had become. This seems to be work nicely for big tasks with lots of information.

You additionally have a close friend in Powerpoint in contemplating tale. Slides are excellent for shuffling your presentation narrative order. And while you have fun with your order of activities in your tale, consider carefully your market and also the message you truly want them to listen to and get hold of using them. Rehearse the narrative in your mind you can use to make your information work best as you think about which order.

Give it a shot if the works that are flip you.

summer reading – or – not totally all reading is the identical

Academics frequently anticipate doing their very own operate in summer time – the task they can’t reach during term time. We compose bids, documents and publications during our . And something associated with the means we have ourselves in to the right writing framework of thoughts are to read – and look at the reading.

I’ve got a few things that are reading the look at summer time. I’ve a bid to publish, and a few documents. Indulge me personally while We describe exactly what this really means i’m doing. I really hope to demonstrate you that most reading just isn’t the exact exact same. We read things that are various different purposes, and as a result of that, we do various things using the texts.

The bid – reading for what’s not there

The bid Im focusing on has been a outside research partner. I have worked together with her a whole lot. We now have understood one another for approximately fifteen years but started really collaborating about eight years back. We’ve now done research that is funded written together and co-supervised. This will be a term that is long relationship and therefore means i’ve a reasonable concept of the types of items that she and her organisation are thinking about.

Recently, and without specially wanting to, I experienced concept for a study task. It simply is actually something that my research partner and I also have idly discussed over time. In a small Eureka minute, We realised that the idle conversation had been really a research-project-in-waiting. We emailed my colleague and sketched out of the concept. She ended up being enthusiastic, when I knew she will be. Then again she stated that she was especially enthusiastic about one facet of the concept. In reality, it absolutely was something that concerned her. Plus it had been something her organization is thinking about having examined.

It was feedback that is great. This is now our concept. I let her remarks sit for a time after which had another aha minute. We went back once again to her by e-mail once again and said “ Well why don’t we make that the research concern?” As well as a response that is affirmative straight straight back.

We ‘d started at that time to find yourself in the literatures. I wasn’t starting from scratch right right right here. We currently knew a great deal of areas and texts We had a need to consist of, and I also knew a number of the key article writers. But I could see that there was almost nothing about the very thing we were/are looking at as I systematically noted and mapped. (a hooray that is small. But there clearly was loads of material about associated topics which tellingly left it down. Therefore, for us to complete. once we thought, there was clearly one thing) we also discovered someone noting the gap – very useful. We could be confident in saying that there clearly was nevertheless an important in addition to of good use share we are able to make through our proposed task.

We delivered my initial scoping to my research partner. We then came across one on one to talk, decide whether or not to continue and in case so, to concur a possible research design. My research partner also promised to incorporate some more texts for me personally to consider. August my job now, as this IS my job, as my research partner has another job, is to write a draft by the end of.

Composing the bid will involve more reading thus. Only if half of that which we read goes into the bid text, that does not matter, we know the fields we are straddling and say that to the reviewers through carefully selected references as we have to be sure.

The reading and reasoning I’m doing listed below are to start up and place work that is new. We clarified an “industry” issue after which seemed to see just what research there currently had been. And right right right here, we had been looking just as much for just what there was clearly– that is n’t exactly what could possibly be – in addition to just just what there was clearly.

https://www.nemkurutma.com/we-have-been-frequently-thinking-about-how/

NEM KURUTMA HİZMETLERİ

0 notes

Text

Austin: A native of Chicago, Michael Smith emerged in New York in the late ‘70s, performing in both non-profit art spaces like The Kitchen and Artists Space, and in small nightclubs and cabarets. Smith is one of the first artists not to be afraid to confront the forms of television entertainment. His entire production revolves around Mike, his alter ego, the protagonist of performances, videos and installations that replicate the generic interiors of sitcoms.

Mike is the average American: clumsy, enterprising, motivated by the desire to succeed and excited by the taste for business. Smith shapes an aesthetics of failure, perhaps animated by the feeling of inadequacy towards TV that the artist confesses he felt as a child. Indeed, like all good comedians, the ability to make the audience laugh is to stage a farce in which the distinction between the fictional character and the real actor is never clear.

In his career, Smith has collaborated with other artists including Mike Kelley, Joshua White and William Wegman. His work has been presented and exhibited in galleries, theatres, universities, clubs, on television and in museums such as MoMA, the Metropolitan and the Whitney in New York, Le Consortium, Dijon, and the Kunstverein, Munich. He has taught at Columbia University and Yale and is currently a Professor at the University of Austin, Texas, where he spends most of his time in a small house full of rainbows.

How did you start collecting rainbows and why?

I needed a little hope in my life, not to mention a little colour in my home.

It started as kind of a fluke, a kitschy sort of gesture. Then I got into it. Friends started giving me rainbows. Not too long after, I learned that if you bring rainbows into your life, unicorns will follow.

You live between Brooklyn, where you also have a studio, and Austin, where you are a professor at the University of Texas. Which of the two places do you prefer?

To be honest, no matter where I am, it always seems like I am in my underwear in front of the computer. The reason I moved to Austin was because of my job. Much of my time there revolves around teaching and recovering from travelling, since I am on a plane every two weeks. When school is not in session, I go back to NYC, the place where most of my old friends and family live. I’ve lived there for 35 years, so it feels like my home.

Can you list all the places you’ve lived in?

I grew up in Chicago and lived there until I was 17. Then I went to college in Colorado and was there until I was 19. For the next five years I was between Colorado, NYC and Chicago. When I finished my studies in Colorado and earned my undergraduate degree, I knew that I was not ready to go back to NYC and moved back to Chicago to work for my father in his real estate business. That lasted four months and I made a lateral move to delivering pizzas and trying to figure out what to do next in the studio after realising I was no longer a painter. In 1976 I moved to NYC, and eventually to Brooklyn. Oh, and in 1997 I lived in Los Angeles for about six months when I was teaching at various art schools around the city.

What about the homes you’ve lived in? Do you have a favourite?

I lived in an office building in Chicago after college. Two other friends and I rented the entire second floor for $100 a month. There were about 10 offices and two bathrooms connected by a 120-foot-long hallway. Lots of windows and each of us paid only $35 a month. Oh, the good old days.

Do you you use to carry objects and furniture with you when you move, or do you find new stuff every time you settle in a new place?

It all depends on how far I’m moving, but for the most part, other than a mattress and some knick-knacks, I eventually get new stuff.

Currently, my favourite TV show is Storage Wars, a reality show where a group of people meet in front of storage units whose tenants have stopped paying the rent, and start bidding to win what’s inside without even seeing it. Are you familiar with that? Do you agree with me that storage has become a symbol of American culture?

I like that show a lot too. What fascinates me is how the people immediately calculate the value of their purchases, as if inventorying translates into immediate cash. It is really wishful, deluded thinking. As for becoming a symbol of American culture, I’m not so sure I see that, but I do think it is indicative of a precarious economic situation that the US and much of the world is experiencing these days.

Am I right in saying that the objects that people normally put in storage units play a major role in your artistic production?

Much of my work has been developed from and built out of discarded objects. Many of the props I use were things I collected. I cannot and do not try to assume what these things meant for others and try to figure out what they mean for me. Storage, however, plays a large role in my life; what to do with all the boxes of crap with the details for my immersive installations.

How did performance help you, through stand-up comedy, to question TV in the first place?

TV helped me to question performance art more than performance art helped me to question TV. I do not question TV. I accept that it exists, even though I may not like the majority of the content I see broadcasted or cablecasted. Stand-up comedy provided an interesting and totally different model to work off, rather than the serious performance art model in vogue around the art world back in the mid-‘70s. Also, stand-up allowed me to consider and accept non-sequiturs as a way to connect widely unrelated ideas.

‘Mike’ is a fake persona you’ve been using in most of your artworks. Is he your alter ego or, as you said in a conversation with Mike Kelley, a ‘vehicle’ for you, ‘an empty shell?’

Mike is a convenient vehicle that I still use today. It seems like we are getting old together. Much of my work is self-reflexive, like much of the television and art of my generation, and what better way to underline this idea than to use a persona that goes by the same name as yourself?

Please tell me the five adjectives that best describe Mike.

Hopeful, slow, innocent, oblivious and trusting.

You emerged in New York in the late ‘70s. Other artists started to question mass media and TV in those same years. I am thinking of Richard Prince, Jack Goldstein, Barbara Kruger and especially Dara Birnbaum. How different was your research in comparison with that of the Pictures Generation?

A big difference is that I made original television programs. They borrowed, copied, re-presented and repurposed old TV. I did this too, but primarily by using the formats and structures from old, well-worn and familiar TV genres.

TV was present in your work since the beginning, even when you were performing. In Down in the Rec Room (1979), at Artists Space, you tune in some TV programs within a reconstruction of a generic American domestic setting. How did you select them?

I think it was the embarrassment quotient of those shows that originally drew me to them, but also, their pop look and feel of each.

The documentation of that performance has been mounted as a narrative video. Has video helped you to add something to the performance?

It was the first video of a performance I reworked and re-purposed and also the video that allowed me to go further and produce Secret Horror. Video in general has allowed me to experience the limits of performance.

Secret Horror (1980) is constructed as a sitcom, like many other of your following videos. Mike has a nightmare in which some ghosts force him to take a TV quiz introduced by a voice-over saying ‘We moved his entire living room down to the studio’. Is that just a nightmare or is this what happens when we watch TV, that our living room becomes a TV studio?

It is set up as a dream and in relation to the story, it most likely telegraphs the idea that TV is a kind of opiate. But when writing a piece, a dream is a convenient device to move a story forward and to connect unrelated images and ideas.

A major role in Secret Horror is played by the grid, which is a planimetric model of how American cities and homes are built, but it is also symbolic of how lives are organised into preconceived structures. Is my interpretation too conceptual?

No, I thought of this, but it was also a very literal translation of experiencing my local bank renovate and convert a beautiful, old vaulted ceiling bank building into a bland, drop-ceiling office space.

What specific TV interiors mostly influenced the interiors where Mike lives?

‘50s and ‘60s American sitcom sets.

In 1983 you worked around the idea of the shelter, with a video, Mike Builds a Shelter, and an installation, Government Approved Home Fallout Shelter and Snack Bar. To me, it looks like another experiment on interiors, an exploration of what we need at home to be happy without going outside.

Happy? I think the shelter is more about feeling secure. If security means happiness, I agree with you.

Then you did Go For it, Mike (1984), with Mark Fisher, one of your most entertaining videos. It’s the story of a ‘regular guy’ from a small town who becomes first the most popular guy in the school and later a successful entrepreneur, which is also the story of the American dream, from the Far West to the Ford. What role have cinema and TV played in shaping this dream?

It is an understatement to say that cinema and TV have played a role in shaping the American dream. When I made Go For It, Mike, President Reagan was about to run his ‘Morning in America’ campaign ads, political advertisements showing bankrupt Americana images of the western range, the rugged individualist, family religion and the flag, together promoting a message that talked about simpler times in America.

The video Mike (1987) begins in black and white with Mike looking at the camera and saying: ‘It seemed to be another regular day, but a voice kept telling me: ‘this is going to be the first day of the rest of your life’’. Who’s voice is that?

It was my voice. I would have preferred to hire a professional voice-over person, but I never got it together. I wanted a voice that gave a feeling of authority and disengagement, kind of an omnipotent voice. I later learned that in voice-over terminology it is called the voice of God.

How much do you think what we see in TV influences the way we build our identity, both in private and in public?

I do not have a clue how much or little it influences our identities. However, as for me, when I was a young child, it succeeded in giving me a feeling of inadequacy. For others I hope it has sent a more positive message.

Mike’s clothes reflect the generic taste he has for furniture and decoration. Can we talk about the interiors in Mike’s videos as a living uniform?

Generic and bland, mixed with the homey and some splashes of colour, is what I hope to bring to the Mike mise-en-scène.

Do you think art should be entertaining?

It depends what you think entertaining means. I think art engages its audience on various levels. If it also means entertaining an audience, then sure: why not entertain? To say that a mandatory goal of art is to entertain… I do not think I agree with that.

In a conversation with Dan Graham for Artforum in 2004, you talk about Eric Bogosian and Laurie Anderson as ‘two artists who successfully made the transition’ from art to mass media. Have you ever been interested in doing the same?

Yes, I was very interested in trying to cross over at a particular time during my career. I figured if I am doing comedy, why not see how it worked in front of a more general audience. In the mid ‘80s to the early ‘90s I co-produced two variety shows, Mike’s Talent Show and Mike’s Big TV Show, at very mainstream NY nightclubs. I had a manager, an agent and my own cable special on Cinemax. In 1991-1992, I developed in workshops a children’s show called Mike’s Kiddie Show. It went nowhere. I realised I was not interested in producing TV for children, but was more interested in doing juvenile shows for adults. From 1992 to 1996, I did puppet shows with Doug Skinner called Doug and Mike’s Adult Entertainment. I thought it was the funniest material I’ve done over the years and thought for sure we would be able to find a larger audience but potty humour stopped us from moving more into the mainstream. South Park and Beavis and Butthead came around a little later and successfully explored and developed that niche. By the way, the video Mike was produced for Saturday Night Live.

Among the people you’ve collaborated with, a special place is occupied by Joshua White, known for his legendary Joshua Light Show, an environmental light show that used to accompany live psychedelic concerts in the late ‘60s and is still touring the world. When did your collaboration begin and how does he contribute to your work?

Our collaboration began in 1992 when he directed the Doug and Mike puppet shows. We first met a few years earlier, when he saw one of my variety shows in a club and offered his services on future projects. Later I got the idea for Mus-co (1997), after hearing his stories and experience as a famous light show artist. For many of our collaborations Joshua designed the installations, but he was also very involved with developing the concepts, directing all the videos and capturing a look and feel that was totally convincing, not to mention very successful. Our last project was Mike’s World in 2007.

A Voyage of Growth and Discovery (2009) is a video/installation/performance project that you and Mike Kelley presented at the Sculpture Center, New York. It features videos of you, dressed as a baby, wandering through the desert at the Burning Man Festival. What did you guys find there?

We were looking for a very colourful and active backdrop for the baby, a character who for the most part does very little. The baby basically wandered through the festival looking for distraction and/or something to put in his mouth.

Did you think about the way you presented that work in sculptural terms?

Mike [Kelley] was responsible for designing the installation. I was more responsible for producing the videotape at the festival. Mike did not go and that was probably a good thing. He was not the best traveller. For the installation, we used video on multiple screens to recreate the atmosphere and intensity of the original festival. We wanted it to be immersive for the viewer.

People use to refer to your work as parody. However, most of it doesn’t necessarily look critical. Isn’t it more as if you’re trying to understand how that mechanism of media entertainment works?

I use parody and also satire. At times I hope to reveal the mechanism of media but it depends on the project. All in all, I hope my work operates on various levels and the viewer is able to engage in one way or another.

I think your work is more relevant than ever today, in the age of digital media and the Internet. Indeed, your research was never just about TV, but about the way we use fictional narratives to create our identity, which is something people are still doing online, now that they have the means to create their own entertainment.

Thank you.

0 notes

Text

Staging the Lure of the East: Exhibition Making and Orientalism

Christine Riding is now Senior Curator and Head of Arts at the National Maritime Museum. Her essay on the Staging the Lure of the East: Exhibition Making and Orientalism was written in 2011 during her time as Curator of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-century British Art at Tate Britain.

The text centres the curatorial process of exhibiting Orientalist art as well as marketing to attract a wider audience. The aim was to provide a British platform for varying artistic interpretations of the subject in order to mirror a culturally diverse London. Furthermore, through art, the intent to shift the Western portrayal of Eastern culture is informed by the socio-political climate both before and after 9/11 and the July 7th bombings.

Leila, Frank Dicksee (1853-128) - (Photo - http://www.peramuseum.org/Exhibition/The-Lure-of-the-East-British-Orientalist-Painting/108)

The Curator made a conscious decision to highlight the painter’s adaptation of conventional techniques by assembling artwork according to production rather than chronological order. Riding elaborates on her approach

‘focus on nineteenth and early twentieth-century artists who had travelled to the eastern Mediterranean’

This immediately changes the readership, emphasising who the artists were and how their journeys and diverse experiences defined their work. This avoids merely naming an overarching theme, which governs the work. Furthermore, using alliteration in titles such as Genre and Gender or Harem and Home served a tone so as not to downplay French over British interpretations of landscape and portraiture.

Edfu, Upper Egypt, John Frederick Lewis (1860) (Photo - http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/lure-east-british-orientalist-painting/explore-exhibition/lure-ea-4)

The purpose of postmodernist art is to challenge and provoke whether right or wrong. It should breathe life into discussion and debate for this very reason. By removing Latham’s God is Great deeming it offensive, the curator immediately shuts down any conversation about religion so as not to offend. Riding describes the installation

‘The work, a freestanding sculpture comprising large glass panel with three used editions of the Bible, the Qur’an, and the Talmud was judged to have been too sensitive to be exhibited in the immediate aftermath of the London bombings on July 7.’

Here, we see evidence of government organisations folding under pressure from the Muslim Public Affairs Committee. Given that their voice didn’t represent the reaction of an entire community, I feel that the Tate’s motive sought to preserve a public image through social justice rather than a humanitarian interest. In short, it is an effort to avoid open debate, which ultimately affects successful sales. This notion has been prevalent since Labour’s victory in 1997, whereby government directives and initiatives concerning multiculturalism and diversity were imposed to force this narrative through public art institutions. Exhibitions such as Discover What We Share focused on raising an awareness of commonalities between Abrahamic faiths as opposed to differences.

© John Latham Estate, courtesy Lisson Gallery, London, License this image ( Photo - http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/latham-god-is-great-no-2-t11969)

Successful sales however, must occur in order to have a profound and lasting social impact. Therefore, advertising this exhibition in an appropriate manner is a necessary evil. Riding divides the target audience

the kind of people reading this essay, people who are curious about, knowledgeable of and alive to the complexities of the subject matter of Orientalism—and everybody else.

In order for both archetypal audiences to encounter this promotional material, they were strategically placed both in public areas of transport and in popular reading material. Furthermore, promotional images varied, depending on the target audience profile. Riding recognises this by selecting the ‘user friendly’ image of Leila to grasp the conservative readership in The Daily Telegraph. Whilst conjunctively promoting the Arab Interior as the general poster design to temper clichéd associations with the East, to the masses.

To conclude, this exhibition achieved its goal to convey a rich culture and civilisation, which pre-dates ours. In a review from June 2008, Jonathan Jones from the Guardian opens ‘It provokes a complex response to a complex history.’ With a technologically interconnected news network, groups are more divided than ever and attitudes of East and West tend to be formed based on what we watch, not what we experience.

Questions:

What was the overall turnout of this exhibition during its opening week in comparison to its last?

Did it resonate with the audience in the intended manner for which it was meant?

0 notes

Text

Final Outcome: Prep for day 1

Plan

For my final outcome, I first need to conduct a new shoot so that all my photos are not ones I have used in previous experiments. I first need to decide on a location that my shoot will take place. My model will be amongst natural elements so will be best to shoot in a forest, park or woods but due to living in a city this may be difficult to capture with no buildings etc. disturbing the mise en scene. Therefore before I can take my shoot I need to go location scouting in preparation for the shoot that will be used in my final outcome.

Shoot Preparation

Location Scouting:

First I decided to consider shooting at our school fields or the small garden at school, the fields had a lot of open space to be able to shoot wide images, however, there was not much else around to create an interesting composition and after taking some shots of the school garden I noticed the building could be seen through the gaps in the bushes which looked very out of place. I then decided to visit the local park Telegraph Hill as it is one of they very few green areas local to me where I would be able to take all the things I need for this shoot. It has few tree’s which would work to add depth in the image, however, I needed to be able to shoot varying images within one location and Telegraph Hill did not offer enough versatility. I decided that inspired by a particular shoot from Luca Meneghel an Italian photographer who specialises in fashion and advertising photography but creates quite dramatic images which clearly illustrate a narrative of some sort. One of his well-known works is shot in a graveyard which mixes eerie with beauty that has a powerful effect. I chose to next visit Nunhead Cemetery where I was able to find multiple shooting locations. There were many places within the cemetery where the greenery was very overgrown and had created little coves perfect for the fantasy effect I am hoping to create, this draws on the artificial element of the theme quite conceptually as all fantasies are imagined, made up, not real i.e. artificial but also by shooting in this natural environment it quite literally draws on the natural part of the theme.

Outfit:

If my model is wearing a hoodie and trainers it will completely ruin any element of fantasy inspired by the Victorian fairy images. My artist research back at the start of this project on Lissy Larcchia showed me the importance of what your model wears if her subjects were not dressed in clothing which is clearly identifiable to the character she was intending to create in each image the overall photographs would have been weaker and out of context. I decided to draw some sketches of what my model could wear and then have a look as to what I could find to fit my sketches.

I decided on my model wearing a tutu style white skirt as this resembles a fairy relating to the floating images in the final outcomes. Also, she will wear a lace top as lace as it is a very delicate material which appears well in photographs.

Equipment:

To actually pull off the shoot to a high standard I firstly need a tripod to ensure that when I take the image without my model in and then with the model in that the placement, height or framing does not change as I need it to be the same for ease when editing during the first 5 hour session. I will be shooting digitally on a ‘Canon EOS 1300D’ . I will also need a stool for my model to balance on to create the floating outcomes.

0 notes