#it sounds like he's from around the same area as tommy lee jones?

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

youtube

#justified#doyle bennett#joseph lyle taylor#look#I never post 'original' content#but doyle needs to be on the interwebs so#I am doing my duty#I love doyle#I love joseph lyle taylor#also#his accent is so fucking great?#it sounds like he's from around the same area as tommy lee jones?#maybe?#anyway#I fucking love him#and he's 55?!#jesus h#apparently he does not age#so that's good to know#tv!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

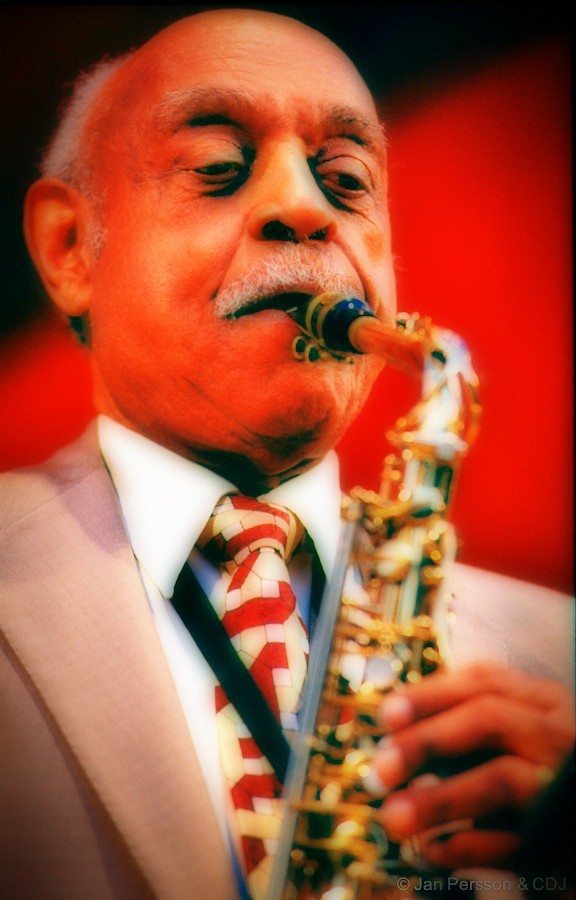

Benny Carter

Bennett Lester "Benny" Carter (August 8, 1907 – July 12, 2003) was an American jazz alto saxophonist, clarinetist, trumpeter, composer, arranger, and bandleader. He was a major figure in jazz from the 1930s to the 1990s, and was recognized as such by other jazz musicians who called him King. In 1958, he performed with Billie Holiday at the Monterey Jazz Festival - but, then, really, he performed with every major artist of several many jazz generations, and at every major festival you could possibly care to name.

The National Endowment for the Arts honored Benny Carter with its highest honor in jazz, the NEA Jazz Masters Award for 1986. He was awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1987, and both won a Grammy Award for his solo "Prelude to a Kiss" and received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1994. In 2000 awarded the National Endowment for the Arts, National Medal of Arts, presented by President Bill Clinton.

Biography

Born in New York City in 1907, the youngest of six children and the only boy, received his first music lessons on piano from his mother. Largely self-taught, by age fifteen, Carter was already sitting in at Harlem night spots. From 1924 to 1928, Carter gained valuable professional experience as a sideman in some of New York's top bands. As a youth, Carter lived in Harlem around the corner from Bubber Miley who was Duke Ellington's star trumpeter, Carter was inspired by Miley and bought a trumpet, but when he found he couldn't play like Miley he traded the trumpet in for a saxophone. For the next two years he played with such jazz greats as cornetist Rex Stewart, clarinetist-soprano saxophonist Sidney Bechet, pianists Earl Hines, Willie "The Lion" Smith, pianist Fats Waller, pianist James P. Johnson, pianist Duke Ellington and their various groups.

First recordings

He first recorded in 1928 with Charlie Johnson's Orchestra, also arranging the titles recorded, and formed his first big band the following year. He played with Fletcher Henderson in 1930 and 1931, becoming his chief arranger in this time, then briefly led the Detroit-based McKinney's Cotton Pickers before returning to New York in 1932 to lead his own band, which included such swing stars as Leon "Chu" Berry (tenor saxophone), Teddy Wilson (piano), Sid Catlett (drums), and Dicky Wells (trombone). Carter's arrangements were sophisticated and very complex, and a number of them became swing standards which were performed by other bands ("Blue Lou" is a great example of this). He also arranged for Duke Ellington during these years. Carter was most noted for his superb arrangements. Among the most significant are "Keep a Song in Your Soul", written for Fletcher Henderson in 1930, and "Lonesome Nights" and "Symphony in Riffs" from 1933, both of which show Carter's fluid writing for saxophones. By the early 1930s he and Johnny Hodges were considered the leading alto players of the day. Carter also quickly became a leading trumpet soloist, having rediscovered the instrument. He recorded extensively on trumpet in the 1930s. Carter's name first appeared on records with a 1932 Crown label release of "Tell All Your Day Dreams to Me" credited to Bennie Carter and his Harlemites. Carter's short-lived Orchestra played the Harlem Club in New York but only recorded a handful of brilliant records for Columbia, OKeh and Vocalion. The OKeh sides were issued under the name Chocolate Dandies. His trumpet solo on the October 1933 recording of "Once Upon A Time" by the Chocolate Dandies (OKeh 41568 and subsequently reissued on Decca 18255 and Hot Record Society 16) has long been considered a milestone solo achievement.

In 1933 Carter took part in an amazing series of sessions that featured the British band leader Spike Hughes, who went to New York specifically to organize a series of recordings featuring the best Black musicians available. These 14 sides plus four by Carter's big band were only issued in England at the time, originally titled Spike Hughes and His Negro Orchestra. The musicians were mainly made up from members of Carter's band. The bands (14–15 pieces) include such major players as Henry "Red" Allen (trumpet), Dicky Wells (trombone), Wayman Carver (flute), Coleman Hawkins (saxophone), J.C. Higginbotham (trombone), and Leon "Chu" Berry (saxophone), tracks include: "Nocturne", "Someone Stole Gabriel's Horn", "Pastorale", "Bugle Call Rag", "Arabesque", "Fanfare", "Sweet Sorrow Blues", "Music at Midnight", "Sweet Sue Just You", "Air in D Flat", "Donegal Cradle Song", "Firebird", "Music at Sunrise", and "How Come You Do Me Like You Do".

Europe

Carter moved to Europe in 1935 to play trumpet with Willie Lewis's orchestra, and also became staff arranger for the British Broadcasting Corporation dance orchestra and made several records. Over the next three years, he traveled throughout Europe, playing and recording with the top British, French, and Scandinavian jazzmen, as well as with visiting American stars such as his friend Coleman Hawkins. Two recordings that showcase his sound most famously are 1937's "Honeysuckle Rose," recorded with Django Reinhardt and Coleman Hawkins in Europe, and the same tune reprised on his 1961 album Further Definitions, an album considered a masterpiece and one of jazz's most influential recordings.

Return to Harlem and a move to Los Angeles

Returning home in 1938, he quickly formed another superb orchestra, which spent much of 1939 and 1940 at Harlem's famed Savoy Ballroom. His arrangements were much in demand and were featured on recordings by Benny Goodman, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Lena Horne, Glenn Miller, Gene Krupa, and Tommy Dorsey. Though he only had one major hit in the big band era (a novelty song called "Cow-Cow Boogie," sung by Ella Mae Morse), during the 1930s Carter composed and/or arranged many of the pieces that became swing era classics, such as "When Lights Are Low," “Blues in My Heart," and "Lonesome Nights."

He relocated to Los Angeles in 1943, moved increasingly into studio work. Beginning with "Stormy Weather" in 1943, he arranged for dozens of feature films and television productions. In Hollywood, he wrote arrangements for such artists as Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, Billy Eckstine, Pearl Bailey, Ray Charles, Peggy Lee, Lou Rawls, Louis Armstrong, Freddie Slack and Mel Torme. In 1945, trumpeter Miles Davis made his first recordings with Carter as sideman on album Benny Carter and His Orchestra, and considered him a close friend and mentor. Carter was one of the first black men to compose music for films. He was an inspiration and a mentor for Quincy Jones when Jones began writing for television and films in the 1960s. Carter's successful legal battles in order to obtain housing in then-exclusive neighborhoods in the Los Angeles area made him a pioneer in an entirely different area.

Benny Carter visited Australia in 1960 with his own quartet, performed at the 1968 Newport Jazz Festival with Dizzy Gillespie, and recorded with a Scandinavian band in Switzerland the same year. His studio work in the 1960s included arranging and sometimes performing on Peggy Lee's Mink Jazz, (1962) and on the single "I'm A Woman" in the same year.

Academia

In 1969, Carter was persuaded by Morroe Berger, a sociology professor at Princeton University who had done his master's thesis on jazz, to spend a weekend at the college as part of some classes, seminars, and a concert. This led to a new outlet for Carter's talent: teaching. For the next nine years he visited Princeton five times, most of them brief stays except for one in 1973 when he spent a semester there as a visiting professor. In 1974 Princeton awarded him an honorary master of humanities degree. He conducted workshops and seminars at several other universities and was a visiting lecturer at Harvard for a week in 1987. Morroe Berger also wrote the book Benny Carter – A Life in American Music (1982), a two-volume work, covers Carter's career in depth, an essential work of jazz scholarship.

In the late summer of 1989 the Classical Jazz series of concerts at New York's Lincoln Center celebrated Carter's 82nd birthday with a set of his songs, sung by Ernestine Anderson and Sylvia Syms. In the same week, at the Chicago Jazz Festival, he presented a recreation of his Further Definitions album, using some of the original musicians. In February 1990, Carter led an all-star big band at the Lincoln Center in a concert tribute to Ella Fitzgerald. Carter was a member of the music advisory panel of the National Endowment for the Arts. In 1990, Carter was named "Jazz Artist of the Year" in both the Down Beat and Jazz Times International Critics' polls. In 1978, he was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame and in 1980 received the Golden Score award of the American Society of Music Arrangers. Carter was also a Kennedy Center Honoree in 1996, and received honorary doctorates from Princeton (1974), Rutgers (1991), Harvard (1994), and the New England Conservatory (1998).

One of the most remarkable things about Benny Carter's career was its length. It has been said that he is the only musician to have recorded in eight different decades. Having started a career in music before music was recorded electrically, Carter remained a masterful musician, arranger and composer until he retired from performing in 1997. In 1998, Benny Carter was honored at Third Annual Awards Gala and Concert at Lincoln Center. He received the Jazz at Lincoln Center Award for Artistic Excellence and his music was performed by the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis, Diana Krall and Bobby Short. Wynton accepted on Benny's behalf. (Back trouble prevented Benny from attending.)

Carter died in Los Angeles, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center July 12, 2003 from complications of bronchitis at the age of 95. In 1979, he married Hilma Ollila Arons, who survived him, along with a daughter, a granddaughter and a grandson.

Songs composed by Carter

"Blues in My Heart" (1931) with Irving Mills

"When Lights Are Low" (1936) with Spencer Williams

"Cow-Cow Boogie (Cuma-Ti-Yi-Yi-Ay)" (1942) with Don Raye and Gene De Paul

"Key Largo" (1948) with Karl Suessdorf, Leah Worth

"Rock Me to Sleep" (1950) with Paul Vandervoort II

"A Kiss from You" (1964) with Johnny Mercer

"Only Trust Your Heart" (1964) with Sammy Cahn

Other songs by Carter include "A Walkin' Thing", "My Kind of Trouble Is You", "Easy Money", "Blue Star", "I Still Love Him So", "Green Wine" and "Malibu". Of course there are, literally, hundreds more - he truly was one of jazz's greatest composers.

http://wikipedia.thetimetube.com/?q=Benny+Carter&lang=en

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Legacy of John Carpenter’s Escape From New York

https://ift.tt/36u9a0g

Escape from New York came out 40 years ago this week. Released on July 10, 1981, director and co-writer John Carpenter’s sardonic sci-fi action thriller is set in a future United States where the rise of rampant crime has led to Manhattan Island being walled off and turned into a gigantic supermax prison.

When Air Force One is hijacked and forced to crash land on the island, the federal government turns to ex-Special Forces soldier-turned-criminal Snake Plissken (Kurt Russell) to get onto the island and rescue the President (Donald Pleasance) in under 24 hours.

At stake: the president’s life and his appearance at a critical peace summit with China and the Soviet Union. If Snake succeeds, he gets a full pardon for his crimes. If he doesn’t, a device attached to his neck explodes and kills him.

Carpenter and his friend Nick Castle (who played The Shape in the original Halloween) reportedly wrote Escape in 1974 as a response to both the Watergate scandal and the resultant distrust in government, plus the onslaught of crime during the 1970s in major cities like New York.

With crime on the rise again to some degree following the COVID-19 pandemic, Escape remains eerily relevant in some ways, even if American cities are not quite falling back into the chasm of crime from which they struggled to climb out in that turbulent decade.

“The decay of New York in the ’70s was pronounced then,” Carpenter told us earlier this year when speaking briefly about the film. “It was really bad.”

The idea of crime running out of control and leading to desperate measure by an authoritarian government is still seen today in films like The Purge and its sequels. In those, the U.S., now a reactionary theocracy, allows for one night every year in which all crime, including murder, is legally allowed. Carpenter himself cited the Purge series as a descendant in some ways of his picture.

James DeMonaco, who created The Purge, directed the first three films and written all five (including the recently released The Forever Purge), confirms the influence of Escape from New York on his franchise and acknowledges the film as one of his favorites.

“I’d still stand by it,” DeMonaco tells Den of Geek. “It’s in my top 10, because I was so blown away by it. I remember my dad got our first VCR, I was probably 13 or 14, somewhere around there. He brought tapes home and…I think they were bootleg even back then, but Escape from New York, First Blood, and Mad Max were in the first batch.”

DeMonaco continues, “I must have worn those things out, but of all the three, I think Escape from New York, I could probably recite every line. There was something about the way Carpenter shot it. This dystopian future of New York being walled off stayed with me to this day.”

Carpenter had just directed two horror films in a row — his 1978 breakout Halloween and the 1980 ghost story The Fog — and was at first going to possibly direct a time travel thriller called The Philadelphia Experiment. But when he parted with that project over creative differences, Escape from New York became his fifth feature film.

Initially the studio that backed the film, Avco-Embassy Pictures, was interested in casting either Tommy Lee Jones or Charles Bronson as Snake Plissken. “Charles Bronson had expressed interest in playing Snake,” Carpenter told interviewer Gilles Boulenger in the book John Carpenter: The Prince of Darkness. “But I was afraid of working with him. He was a big star and I was this little shit nobody.”

Read more

Movies

How Director John Carpenter Found His Second Career

By Don Kaye

Movies

What We Learned From the Escape From New York Novelization

By Padraig Cotter

Carpenter wanted Russell, with whom he had worked on the TV movie Elvis and would cast in three more films after Escape, including The Thing, Big Trouble in Little China and Escape from L.A. The actor himself was looking for a way to change up his image as the fresh-faced star of Disney family comedies.

“Yeah, he was, and I knew he could do it,” says Carpenter about Russell’s mission. “The studio was just not sure because he hadn’t done anything like this. People are scared if you’re starting something that hasn’t been done before. They want to make sure that it’s been done so they know what they’re getting. They weren’t sure about Kurt. He proved himself so that was great.”

Russell got himself into top physical shape for the role, telling Circus magazine in a 1980 interview, “Snake is a mercenary, and his style of fighting is a combination of Bruce Lee, the Exterminator and Darth Vader, with [Clint] Eastwood’s vocal-ness.” He added that although Plissken starts the film as a convicted robber, “His individuality makes him acceptable to the audience in a heroic way.”

Russell was joined in the cast by legendary Western star Lee Van Cleef, who plays police commissioner Bob Hauk, along with Pleasance as the Chief Executive and stars like Ernest Borgnine, Adrienne Barbeau, Harry Dean Stanton, and Isaac Hayes as denizens of the sealed-off Manhattan interior. But perhaps the toughest casting problem was finding a city to play Manhattan.

The real New York was out of the question because it would be too difficult to make it look semi-ruined on the film’s relatively paltry $6 million budget. So Carpenter, producer Debra Hill and production designer Joe Alves searched for a city that, to be brutally frank, already looked destroyed.

Location manager Barry Bernardi suggested East St. Louis, a rundown area sitting across the Mississippi River from the more affluent parts of St. Louis. There had been a tremendous fire in the neighborhood in 1976, with Hill telling Cinefantastique, “Block after block was burnt-out rubble.”

“Around the turn of the century New York City and St. Louis were very much the same architecturally,” Alves told Starlog in a May 1981 interview. “John and I eventually came [to St. Louis] to inspect a bridge…we looked around at the old buildings and thought they were fantastic. These were structures that exist in New York now, and have that seedy, run-down quality that we’re looking for.”

The movie was shot at night in East St. Louis, from 9pm to 6am, and Carpenter recalls it was a productive but difficult experience. “It was amazing, unbelievable. We were there in the summertime when it’s blistering hot. They had this big fire there in the ’70s. It burned out the place. But they were very cooperative. They turned off all the streetlights, and let us move stuff, and that was just great.”

The film also shot in New York (at Liberty Island), Atlanta (for an unused subway sequence) and on soundstages in Los Angeles before wrapping in November 1980. Upon its release the following July, it grossed $25.2 million at the box office — one of the bigger hits of Carpenter’s career. It also scored well with critics, and like many of Carpenter’s films, its stature has only grown over the years.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

Although the 1996 sequel, Escape from L.A., proved to be far inferior and less successful, Escape from New York has gained classic status and has been a candidate for a remake in recent years. 20th Century Fox hired Robert Rodriguez to direct it in 2017, although that never happened; The Invisible Man writer/director Leigh Whannell was tapped in 2019 to script it, but little has been heard on that either.

James DeMonaco says the remake came his way at one point — but it sounds like he’d rather break into the Manhattan prison and get back out again before touching that prospect. “I still think this is the greatest idea,” he says of the original. “I was offered the remake. I was like, ‘No, I can’t do it. No way. I’m not touching it. We should not touch. This is the perfect film. No one should go near this movie.’”

The post The Legacy of John Carpenter’s Escape From New York appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3wvXSn4

1 note

·

View note

Text

How to promote your album with a podcast

Podcasting as music promotion — including a how-to checklist.

Last NAMM, I attended an inspiring talk by Kevin Breuner, the VP of marketing for CD Baby. He talked about successful release strategies in a streaming world for us independent musicians. That talk gave me the confidence I needed to finally implement a CD-release plan I had hatched up a few months before.

Kevin’s talk wasn’t so much about what you do to promote the album itself, but rather the content you can create around the release of the album.You see, creating extra content to use as the vehicle to promote your record matters more these days than ever before.

Hitting “Publish” on your CD Baby dashboard and telling people you’re on Spotify isn’t enough anymore. You can only nag your friends to “check out my album” so many times before your friends get sick of you. You need to re-frame the conversation with more reasons to talk about it. And having more content than just the album itself gives you more reasons to bring it up in conversations.

As musicians, we are immensely proud of the musical baby we just made, but just like with normal babies, not everyone thinks yours is cute. Constantly asking your friends to listen to your album is similar to a toddler continually pulling his mom’s pant leg for attention. It’s just exhausting.

So what do we musical creators do instead?

Our Plan? Create a Podcast Season Around the Album

When you listen to an album, there’s a lot that goes unsaid. You might not understand all the lyrics. You can’t discern all the instruments that are playing. You don’t know what the songs are about. And since we’re all just throwing our songs on Spotify these days, there’s not a lot of emphasis on the liner notes to tell those stories.

Even if the album is a work of creative musical expression, the story behind the creation of the album gets lost. Behind the Music documentary filmmakers aren’t interested in us independent musicians, so it’s up to us to create the additional content for our fans.

To me, I was in a great position because I had joined the Carnivaleros, a band that was finishing their sixth album. After six records – all of which were released through CD Baby – the band has a lot of history and there are stories left untold that don’t need to go unnoticed.

So we decided to launch a podcast season in parallel with the release of the album. That way, we could tell the stories behind the songs and the creative process behind the record. We could talk about the songwriting, the production process and any fun things that popped up during the sessions. Plus, we could give more credit to some of the session players on the album, and we could draw people’s attention to specific parts of the songs that stood out.

In a nutshell, the podcast gives us an opportunity to promote the album in a new way. Instead of having only an album to promote, we now have 12 new pieces of content to talk about every week. We’ve managed to rephrase and reposition the way we approach our promotional efforts.

Instead of constantly asking,

“Have you heard our new album?”

…we can ask,

“Have you heard the latest podcast episode about the tragic death of Danny Lee? Or the story behind the duet that was inspired by Hilary Swank’s character in The Homesman with Tommy Lee Jones?”

Those are more interesting questions, wouldn’t you agree? And in our lightning-paced society where attention spans are fleeting, capturing interest is king.

Your Simple Checklist to Create Your Own Music Podcast

If you want to do anything creative, I’ve found the best method to be the following:

Visualizing what it looks like as a finished product and then work backward from there.

Now, I’m not talking about visualization in a hippie Yogi kinda way. No, what I mean is that once you know where the finish line is, you can work your way back through all the tasks that are necessary to get there.

Planning is key to achieving your goals, and creating a new promotional vehicle for your album is no exception.

So if you want to create your own podcast, I’ve created a simple 14-step checklist for you in the form of the following questions. Make sure you have the answers to every single one before you start.

Who is involved in the podcast?

What questions are you asking during each episode?

Who is the host that keeps things going during the recording?

What is the structure of the podcast?

When are you recording the episodes?

What equipment are you using to record your podcast?

Are you allowing enough time before the album comes out to get your podcast edited and ready to go?

Where are you recording the podcast?

Who is responsible for the editing?

What website will the podcast live on?

Where are you hosting the podcast episodes?

Who knows how to publish it online to iTunes?

What’s the promotional schedule for the podcast episodes themselves?

Are you releasing everything at the same time or staggering them?

How We Structured the Podcast

I wrote the questions and led the podcast episodes most of the time. I structured the podcasts to tackle three main areas:

Songwriting – How the song was written and the story behind the music.

Arrangement – How it morphed from a simple song into a band arrangement, making sure to credit any and all musicians who appeared on each song.

Production – How we recorded each song, what studio tricks we used and how the sounds got made. I also help home studio musicians make their music sound better at Audio Issues, so it was a great way to keep the podcast even more relevant to my audience, allowing me to cross-promote the podcast to my email list of 30,000 people.

At the end of each episode, after sharing the stories behind the songs, we then play the song so that the listener can gain a deeper relationship with the music.

Here’s How We Tackled the Technical Duties

For the rest of the duties needed to launch the podcast, we each had our responsibilities. The singer/accordionist and songwriter/bandleader, Gary, took on a lot of the website stuff, and Karl, the bass player and mixing/mastering engineer, took on the finalization of the episodes.

We used Gary’s studio, Homestead Studios to record all our episodes. We recorded all 13 episodes in only two days, so we managed to be very efficient with our time. Gary then took care of the editing and Karl mixed them.

It was a great delegation of duties and a real team effort, so I recommend you figure out how to divide the tasks between your team if you have one.

For hosting the episodes, we created a new Soundcloud account, Carnivaleros Podcast – Tales from the Homestead, where we uploaded all the episodes. There are multiple different ways of hosting an publishing podcast episodes, but we decided on Soundcloud due to its ease of use. It also gives you an RSS feed that you can submit to iTunes so our podcast could be found natively through the Podcast app and directly on iTunes.

Our promotional schedule was a hybrid mix of maximum exposure for the binge-listening crowd while still stretching the lifespan of the podcast. We released five episodes at the start to give people a glimpse into what they could expect, as well as some sneak previews of songs we hadn’t released yet. Then we decided to release one episode every week for the rest of the songs off the album, giving us a solid eight weeks of promotional materials for our music.

At the time of writing, we’re only on episode six, and we’ve got over 500 listens on Soundcloud alone. iTunes is a bit stingy on the data so we can’t accurately predict listens there, but the ratings and reviews we’ve received means that we have some followers there as well. We’ve already had positive support from the local fans at our shows, and some journalists have even mined the podcast episodes for additional information for their CD reviews.

Best of all, we’re only halfway through the season so we’ve still got plenty of songs to talk about and plenty of stories to tell!

How Will You Promote Your Next Album?

I realize that making your album was hard enough. You ripped open your chest and bled your music into the world. And now I’m telling you that you need to do all this extra work as well!

I understand it’s a lot of work but as an independent musician the marketing rests squarely on your shoulders. There’s nobody else to help you promote yourself. The marketing should be at least 50% of the effort you put into your art if you ever want anybody to notice it. That’s the definition of marketing right there: “making people notice.”

So even if you don’t want to make a whole podcast season, think about what other types of content you can steadily create to promote your music.

Can you tell interesting stories about the album via blog posts?

Can you share live videos from the studio?

Can you write detailed articles about the meaning behind your lyrics?

Regardless of what you come up with, make sure that you spend as much time getting people to notice your music as you do creating it.

And if you need a break from the exhausting world of music marketing, I’ve got a podcast for you right here you can take a listen to.

I hope that helped!

Björgvin | Audio Issues | The Carnivaleros

The post How to promote your album with a podcast appeared first on DIY Musician Blog.

0 notes

Photo

Country Star Phil Vassar plays a double header at the Sellersville TheaterBy Rob NagyWhen country artist Phil Vassar embarked on his musical journey in the late ‘80s he could never have imagined he would evolve into a hit songwriter let alone a highly successful performer. More than three decades later, with nearly a dozen solo albums under his belt and an impressive list of hit songwriting credits, Vassar is living the dream.Influenced by traditional country music, pop, rock and soul, Vassar has a deep passion for the artists that continue to fuel his creative journey.“I love country, pop, rock. I just appreciate great music, I really do,” says Vassar from his home in Nashville, Tennessee. “I’ve always loved it whenever that Billy Joel or Elton John record came out or whoever it was. I’ve always loved the artists that are true to themselves and true to what they do. Being a piano player, I always gravitated to the guys like Elton John, Billy Joel and Jackson Browne and Bruce Hornsby. I love that music and the way it sounded. There was such a point of difference and a lot of the music just sounds the same now. There are some good artists but the way the system is now, it can be really hard to find them.” “Country music is a different thing,” adds Vassar. “We try to keep it simple. I write songs about real people, real life and real love, real heartache or whatever. There’s not a whole lot of gray area there. I was given advice a long time ago that you better write songs that you love because you’re going to sing those songs the rest of your life.”Vassar’s TV production “Songs from the Cellar,” a series filmed in his wine cellar that features artists talking about music and wine, has been picked up by PBS and will be airing early spring 2018. “We’ve had Tommy Shaw from Styx, Big & Rich, Old Dominion, Hunter Hayes, not to mention songwriters like Tony Arcata, Jeffrey Steele, Mike Reid and Tom Douglas. It’s a really cool thing,” says Vassar says of the web series. “Steve Cropper, who is my neighbor, told stories of writing “(Sitting’ On) The Dock of the Bay” and “Midnight Hour” as well as Brenda Lee talking about how ‘Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree’ was brought to her.”Spending the better part of the ‘90s as a songwriter, co-writing singles for Tim McGraw, Jo Dee Messina, Collin Raye and Alan Jackson among others, Vassar’s talents rapidly became in demand. His efforts did not go unnoticed earning him accolades from the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) as Country Songwriter of the Year in 1999.Signed to a recording artist contract by Arista Records Nashville, Vassar released his self-titled album in 2000 yielding five Billboard country chart hit singles, “Carlene,” “Just Another Day in Paradise “Rose Bouquet,” (his first #1 hit) “Six-Pack Summer” and “That’s When I Love You.” It was also his first gold record (sales of 500,000). Follow-up albums “American Child” (2002), “Shaken Not Stirred” (2004), “Greatest Hits Vol. 1” (2006), “Prayer of a Common Man” (2008) and “Traveling Circus” (2009) yielded an impressive string of hit singles that included “This Is God," “Ultimate Love,” “I’ll Take That as a Yes (The Hot Tub Song),” “Good Ole Days,” “In A Real Love,” “Last Days of My Life,” “The Woman In My Life,” “This Is My Life,” “Love Is a Beautiful Thing,” “Bobbi With an I,” “Everywhere I Go,” “Let’s Get Together,” “Love Is Alive,” and “I Would.”Perplexed by the direction country music continues to take and its lack of individuality, Vassar is quick to offer his observations.“The country music I listened to was Buck Owens, Merle Haggard, Glen Campbell, Ronnie Milsap and George Jones because that’s what my dad listened to,” recalls Vassar. “There are so many I love that I could go on and on. Back in the day you could hear a Kenny Rogers song and a Boston song on the same radio station, which was so cool. Today it’s the same song about the same truck and the same girl and the same drink.”“I think artistically, everybody is trying to do what everybody else is doing,” adds Vassar. “Country is trying to be more rap and more hip and more pop or whatever, trying to appeal to the main stream. Garth Brooks never tried any of that. I’m not sure I like it or not. I think that people are just going to make the music that they make.” “I’m just a normal dude that gets to play music for a living, I mean, how lucky am I. I’m blessed to do what I do and I love it. I have more fun playing now than I have ever had in my life, ever! I just get to concentrate on what I love to do, sit at my piano and play my songs. Fans keep coming out and as long as they do I’ll keep playing and give them what they paid for. That’s what it’s all about.”As a follow-up to his American Soul album in 2017 look for a new U.K. album release from Vassar this spring.Phil Vassar will perform at the Sellersville Theater; located at 24 West Temple Ave., Sellersville, PA, February 16, 2018 at 6:00 P.M. and 9:00 P.M. Tickets can be purchased by calling 215-257-5808 or on-line at www.st94.com. To stay up to date with Phil Vassar visit www.philvassar.com

0 notes