#it could also be stylistic choice/artist evolution

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Interesting detail is how Melinoe's red eye doesn't have a distinct pupil (it's red like her iris) whereas Zagreus has two black pupils. Even with having Hades's eye Zagreus still a little bit more like his mom.

#Melinoe#Zagreus (hades)#hades 2#hades game#hades II#this is corn plating but guess what. I don't care#it could also be stylistic choice/artist evolution#but nem also has the same eyes as thanatos so

511 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coptic Jewelry: broad collars

This is not a common example of jewelry in Coptic art or among material culture, but some depictions exist. These overlap with Byzantine imperial superhumerals and other design elements to a degree, but not entirely. For the purposes of this post, a broad collar is a necklace worn high on the chest that encircles the neck, designed to be of a width noticeably greater than that of a strand necklace. Commonly these may have beads or pendants on their bottom edge (true of both these and the Pharaonic broad collar).

I have no opinion on if these are an evolution of the Pharaonic broad collar, as I have no evidence for or against it. It is certainly possible, and I am curious as to where exactly the Byzantines got the superhumeral from (with Egypt potentially being an origin, as well as the cloud collar of East Asia. I consider the latter somewhat unlikely however, as the cloud collar was adopted in Persia and Turkey centuries later. Visually the styles are more strongly related to the cloud collar than the superhumeral and cloud collar- the aesthetic differences between the latter imply a degree of iteration that doesn't quite make sense given the trade routes and what I know of the material cultures of the trade intermediaries).

This gold one set with gems was reportedly found in Assuit, and has strong Byzantine artistic influences- it is thought the jewelry in the hoard it was part of was owned by someone with ties to the imperial court. It was made some time in the 3rd to 6th centuries AD, and probably hidden in the 7th century, never to be recovered by its owner.

This example was found along with the preceding one, and bears some resemblance to the modern bead net necklaces found in various parts of the world, including the bogma found in Egypt in Bahariya. The design elements here were present in Egypt for several centuries by the time the necklace was put in its eventual findspot.

This carved wood door is currently in the Brooklyn Museum, where it's dated to the 7th-11th century. The figure wears, among other things, a very large necklace of the type I defined. Interestingly, the necklace looks like it has a blue tinge- a common color for the Pharaonic broad collar was blue or turquoise, from faience beads. Coptic artifacts made of faience exist up until the 4th century, but are fairly uncommon compared to earlier periods. Potentially, I think her necklace could have been based on a depiction of a Pharaonic broad collar from a statue or temple- it is known Copts used the structure of temples into Christianization, sometimes carving over the walls or defacing pagan symbols. It's possible the artist saw a partial carving with remaining pigment and felt inspired. It is also possible this style of necklace was one worn at the time the door was made.

In addition to this, occasionally Coptic textiles depict necklaces that could be of the same style. Generally it is difficult to satisfactorily classify these necklaces as such due to the artistic limitations and stylistic choices- some may have been based on chokers, or jeweled decorative bands on the necklines of tunics.

Artifacts referenced:

https://colorsandstones.eu/2022/06/30/the-asyut-treasure-segmented-necklace-d-b/ & https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Asyut_Treasure- The Assiut treasure

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/29386- door

https://art.rmngp.fr/fr/library/artworks/bande-decorative-dionysos-et-d-ariane_tapisserie-technique_laine-textile - textile bust of Ariadne

https://www.doaks.org/resources/textiles/catalogue/BZ.1929.1 - Hanging with Hestia Polyolbus

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nasal Voice Debate: Is Himesh Reshammiya a Pioneer or a Trendsetter?

Himesh Reshammiya, a trailblazer in Bollywood’s music industry, is one of the most polarizing figures due to his distinctive nasal singing style. Whether you’re a fan or a skeptic, his voice has undeniably left an indelible mark on Indian music. While some hail him as a pioneer who dared to be different, others argue that his unique tone has had a mixed reception. In this article, we’ll dive deep into the “nasal voice” debate and explore how Himesh Reshammiya became both a trendsetter and a topic of endless discussion.

1. How Himesh Reshammiya’s Voice Became His USP

When Himesh Reshammiya transitioned from being a music director to a playback singer, his nasal tone was immediately noticed. It wasn’t common in Bollywood’s music scene, which traditionally celebrated deep, resonant voices like those of Kishore Kumar and Mohammed Rafi. Yet, Himesh didn’t shy away from showcasing his unique style.

His first major hit as a singer, Aashiq Banaya Aapne, became a chartbuster, with audiences hooked to its soulful yet unconventional delivery.

His choice to embrace this nasal tone instead of modifying it for mass appeal demonstrated his confidence in his craft.

2. Polarized Reactions to His Singing Style

Himesh Reshammiya’s singing immediately divided audiences and critics.

Supporters: Many applauded him for daring to experiment and breaking away from the stereotypes of Bollywood playback singing. His nasal tone added an emotional intensity to romantic and melancholic songs.

Critics: On the other hand, purists and some industry insiders critiqued his voice as lacking range or finesse. Memes and jokes about his nasal tone became common, but they only added to his popularity in a meme-driven world.

3. How His Voice Influenced a New Wave of Singing

Himesh’s success as a singer inspired a shift in Bollywood’s music scene.

His popularity encouraged other music directors and singers to experiment with unconventional vocal styles.

He proved that commercial success could come from distinctiveness, not just technical perfection.

Several new-age singers like Arijit Singh and Atif Aslam, while stylistically different, have also embraced unique vocal quirks that resonate emotionally with listeners.

4. Artistic Risks and Commercial Payoffs

The business of Bollywood music is deeply tied to numbers, and Himesh Reshammiya’s voice proved to be a lucrative asset for producers.

Songs like Jhalak Dikhlaja, Tera Suroor, and Hookah Bar not only topped charts but also dominated radio stations and party playlists.

Himesh’s music videos further amplified his popularity. His on-screen presence, paired with his signature voice, gave him a dual appeal as a singer and performer.

5. Why His Voice Resonates with Listeners

Himesh’s voice is more than just a nasal tone—it’s a combination of raw emotion and vulnerability. His tracks often focus on themes of heartbreak, love, and longing, which resonate deeply with Indian audiences.

His songs have a storytelling quality that makes listeners feel connected to the emotions he’s portraying.

Additionally, the simplicity and repeatability of his melodies make them easy for fans to hum and remember.

6. The Evolution of Himesh Reshammiya’s Voice Over the Years

Despite sticking to his nasal style, Himesh has continuously evolved his singing approach.

His recent tracks, like Teri Meri Kahani and Adhuri Zindagi, showcase a more refined, balanced use of his voice.

He’s also ventured into classical-inspired tracks, proving his versatility and growth as a vocalist.

Conclusion The debate around Himesh Reshammiya’s nasal voice is as enduring as his career. For some, he’s a pioneer who dared to bring individuality to Bollywood playback singing. For others, he’s a trendsetter who shifted the focus from perfection to authenticity. Regardless of opinions, Himesh Reshammiya’s contribution to Bollywood’s musical landscape is undeniable. His bold choices and unique voice have forever altered how we perceive and celebrate music.

0 notes

Text

To the Beat of a Different Drum MAWSB 9 MSD

According to Petru Moiseev, the author of the article The Specific Treatment of Percussion Instruments in Jazz Music from the 1950s, the style of hard-bop was created on the east-coast jazz scene (Moiseev, 2024). This type of jazz style was popularized by Philadelphian Philly Joe Jones, and Pennsylvanian/jazz legend Art Blakely (Moiseev, 2024). According to researcher/author David Rosenthal, what hard bop was, was an evolution of bebop Jazz that was informed by such artists as Lee Morgan and John Coltrane (Panetta, 1993). The music of hardbop, at least according to Rosenthal, was influenced by the harsh ghettos that the artists inhabited at the time, which resulted in more “sinister” and “darker” moods within its song structure and genre (Panetta, 1993). Rosenthal states that once these artists got popular, and could afford living in middle-class suburbs, that is when the genre started to die out in the 1960s (Panetta, 1993). Continuing on the themes of playing by ear and being self-taught from my previous blog, Philly Joe Jones, not to be confused with Count Basie’s accompanist Jo Jones, was largely self-taught (Gale, 2016). To not lead to confusion, Joe Jones took the moniker from his hometown to separate himself from the other Jo Jones (Gale, 2016). The drumming styles of these then up and coming percussionists would give way to modern jazz. This perhaps can be noted that both Pennsylvania and Philadelphia held a strong influence in the evolution of jazz.

The knowledge of the genre of both bebop and hardbop jazz, how they culminated both on the east coast and Philadelphia as a whole, will inform my project. It is a epiphany that Philadelphia, and the artists that it fostered, were directly responsible for what we know as modern jazz today. It is eye-opening on how the Philadelphian neighborhoods influenced the moods and stylistic choices of playing within these artists. I guess one could surmise that the environment at the time, as well as the artists emotional resonance within their confines, could shape musically what they were feeling, and vice versa. I have seen this before with Detroit, Michigan shaping the sounds of Motor-city rock and roll with Bob Seger, MC5, The Stooges, Alice Cooper, and Ted Nugent, with its rough and tumble blue collar atmosphere at the time. I guess a guess a similar gestation occurred, albeit in a different form of music, in the 1950’s within Philadelphia’s sleepy ghettos. Perhaps a sense of pain, mixed with melancholia shaped the sounds of what we know now as hardbop and modern Philadelphian Jazz. Though I assume jazz-fusion has now been the new kid on the block, as far as where jazz is headed. I think these feelings will always be felt.

I was not able to get feedback from classmates this past Tuesday, as I had problems with my project. I did get feedback from Professor Zaylea, and while the cheap Amazon Headphone microphone did not seem to be the best, the Blue Snowball mic seemed to do a better job than expected. I also took away that maybe a podcast could be possible, in that I saw David Nevil’s podcast performance for initial media. David had great phrasing, used an Audio Technica mic, and produced some great results. David is blessed with a great voice tonality and phrasing. In order to step my game up. I might have to work on my voice tonality, and phrasing. Since David and I are doing different subject matter, as well as presenting in different formats, something needs to be considered. I may have to figure out the appropriateness of presentation regarding to subject matter, and how to exactly shape a voice and persona when it comes to the subject of Philly Jazz, and or a reflection/biography on an up-and-coming Philadelphian Jazz artist. It also might be wise to practice at home some read throughs, but then eventually find a set to produce some good results with the podcast going forth. That being said, it seems achievable and possible to produce good results from within my apartment.

Works Cited

Jazz: Modern Jazz, Be-Bop, Hard Bop, West Coast, Vols. 1-6. (1995). Notes, 51(3), 865. https://link-gale-com.libproxy.temple.edu/apps/doc/A34393566/AONE?u=temple_main&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=ca006928

Moiseev, P. (2024). The specifics of percussion instruments treatment in the jazz music from the 1950s. Studiul Artelor Şi Culturologie: Istorie, Teorie, Practică, 2(45), 41–44. https://doi.org/10.55383/amtap.2023.2.07

Shibboleth Authentication Request. (2024). Temple.edu. https://go-gale-com.libproxy.temple.edu/ps/i.do?p=BIC&u=temple_main&id=GALE%7CK1606006694&v=2.1&it=r&sid=summon

0 notes

Text

How Comic Books affected the Animation Industry

The history of comic books has significantly influenced the animation industry, leaving a lasting impact on the styles, techniques, and narratives that are now commonly seen in animated films and TV shows.

Early Foundations and Influence

Comic books and animation share a common origin in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, primarily driven by technological advances in film and printing. Pioneers like Winsor McCay, known for his comic strip Little Nemo, ventured into animation with his short film adaptations. His work demonstrated how comic-style storytelling could be translated into motion, inspiring future animators to explore the medium more deeply.

Inspired by his son's flick-books, he spent four years and produced four thousand individual drawings in making his first animated cartoon 'Little Nemo', completing it in 1911.

Narrative Techniques and Character Development

The Golden Age of Animation (1928-1969) saw a rise in the adaptation of comic book characters into animated formats, establishing animation as a viable medium for long-form storytelling. During this period, animated shorts and TV series featuring characters like Superman and Batman emerged, bringing the narrative richness of comic books to the screen. These adaptations not only popularized the characters but also influenced animation to adopt storytelling, a concept borrowed from comic books

Visual Style and Artistic Techniques

The influence of comic book art on animation is evident in the strong use of lines, exaggerated expressions, and dynamic poses, which became staples in animated cartoons. Animation techniques, such as those used by pioneers like Emile Cohl and J. Stuart Blackton, relied heavily on the visual storytelling principles established in comic books. The transition from static comic panels to animated sequences helped shape the visual language of animation, emphasizing the movement and expression that are key in both forms

Impact on Modern Animation

In the modern era, comic books continue to influence animation significantly, especially with the rise of superhero-themed animations. Shows like Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse have successfully merged comic book aesthetics with cutting-edge animation techniques, creating a hybrid style that celebrates both mediums. This blending of traditional comic visuals with digital animation showcases the ongoing interplay between comics and animation

Conclusion

The relationship between comic books and animation is one of mutual inspiration. Comic books have provided animation with a rich source of content, narrative structure, and stylistic choices that have shaped the evolution of animated films and television. This interplay has resulted in some of the most iconic characters and stories in pop culture, demonstrating the power of these visual storytelling mediums.

0 notes

Note

Are you willing to speculate about Yizhan? If not kindly ignore this ask. I'm just wondering from your perspective which of the "sharing clothes" pics on the internet is more likely to be actual personal choice between those two, if any?

Hello! Sorry for the delay in getting to this, been rather chaotic on my end of things as I adjust to being home from the hospital and establishing a new routine to manage my health from now on. I’ve been thinking on this ask for a while and how I wanted to approach it and think I have finally settled on a proper way to tackle it.

First, I am not unwilling to speculate on yizhan given that I am very keen on the developments of both their careers and their perceived relationship, whatever it may be. However, I will only be comfortable discussing them from the POV of my role as a stylist and fashion worker/enthusiast. I don’t want this blog to become another rumor mill or become a look-to for “proof” of things in regards to their relationship. There is no true way to prove whether they do in fact share clothes, gift each other accessories, or purposefully “match” their looks. To do so I would have to be their personal styling manager and, dream of exactly that as I may, I am merely a fan with the eyes of someone that works in the field and can therefore only offer my own thoughts and opinions on these so-called candies hidden through their styling choices.

To avoid any further chafing like my post about the DS2 jeans created I will only speak to what I know firsthand of the operations of the Asian fashion circuit and styling industry. I can provide insight into how their trends rise and fall on a cycle, how they often use fashion and style as a means to express not only their cultures but sometimes reflect the current climate of the entertainment world, and of how China specifically all but corners the market on underground fashion and streetstyle. This would then be laid over the context of, let’s say, Wang Yibo and Xiao Zhan’s evolution of style throughout their career and highlight the key features of how their looks tend to be tailored with a subtle nuance of their status combined with their country’s current trends. You can expect a post at a later time (after some thorough investigating and proper sourcing) which will look into exactly all of this and touch specifically on the best known looks they’ve been styled in with a breakdown on how those styles were framed, layered together, and then finally restyled to give emphasis to each of their unique features and overall image promotion.

I will also provide my insights on which features are almost surely items they themselves chose, brought in, or otherwise requested be included. These are mostly accessory pieces that, to my trained eyes, do not fit or flow with the overall intended aesthetic and yet have been properly enmeshed by the style as if to blend them into the final result. My own experience lends many points of reference for artists that have comfort items they refuse to part with that I have had to later find ways to make appear to be a legitimate choice which neither clashes with nor belongs to the finished look. This extends to this ask in that this is why my answer on what my perspective on yizhan “sharing clothes” will be short.

So, what is my perspective on them sharing clothes? It isn’t outside the realm of possibility, nor is it anything I can verify from my lack of personal interaction with them or any of the rumored articles of clothes. What I am willing to comment on is that celebrities and idols, no matter where they are located, overlap in a style and fashion sense both in public spaces and platforms and also in their private lives. It’s not uncommon to buy a brand or even exact style of something and later see that someone else has it as well, and from what I have seen I can say with some degree of certainty that Yibo and Zhan have similar tastes, though still incredibly diverse.

I will later make a post speculating on which brands they each frequent and, by extent, share preference for as well the alleged gifts of accessories they are often seen to be wearing which are widely talked about. I think less of the clothing they are rumored or thought to share and lean more into the idea of them having exchanged items which would be easier to wear under the watchful gaze of public interest and also the inherently personal or intimate nature of giving someone a necklace, ring, bracelet, or set of earrings. It is also much easier to talk a stylist into making an allowance for such items since they are small and can be properly incorporated into an ensemble, or even tucked away into a pocket or beneath the high neckline of a good shirt. As I said, many artists tend to have comfort items or good luck charms or any matter of small in size items that they are hesitant to leave behind when making public appearances. Artists are still people beneath the veneer we stylists mask them in and sometimes need that little bit of themselves to take with them and be grounding in the face of media being in their personal space and making assessments of the them that is being presented.

Apologies for the overall evasive answer, but this ask really did get me thinking and rather than leaving it to sit and idle in my box and make the person asking wait until who knows when, I chose to do it this way. The ask itself is the inspiration for why I want to make the posts I mentioned - it really tripped my thinking on all of this and the fashion enthusiast in me is frothing at the mouth with the prospect of real time breakdowns to expose the amount of work that went into some of your favorite yizhan ensembles. The accessories thing also sparked from a similar desire to be as thorough as possible before I give any careless answers.

You all are very dedicated and passionate and deserve to be treated with a sense of professional courtesy in that I can give you a glimpse into understanding the styles that rendered you speechless or blew you away. Likewise, I think the only responsible way to handle any of the candies that are trademarks of BJYX fandom would be to offer you a different type of breakdown that would adhere to why certain things that you tend to perceive as candy is given context of why some things, to me, look out of place and could truly be a personal touch. This would both exonerate me from having confirm or deny topics I have no means of knowing about while offering a gratifying alternative analysis that stands neutral.

Thanks for the question! I will surely be back with more and also to let everyone know more about these posts as I get nearer to establishing them!

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

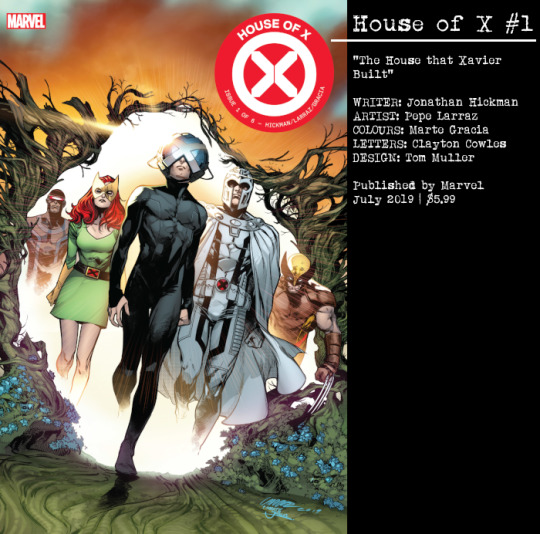

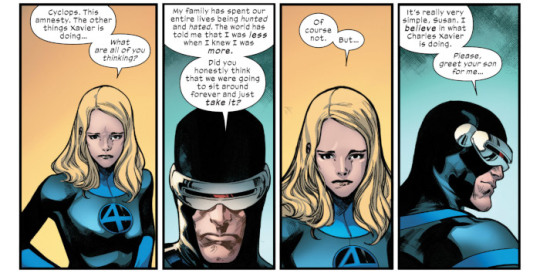

For the past few years, you could argue that the X-Men franchise has been working on trying to rediscover its identity. Since reality reasserted itself coming out of the Secret Wars event, they’ve been in a kind of flux. The initial relaunch set up the mutants in opposition to the ascendant Inhumans. When that was brought to a head, Marvel’s merry mutants then redefined themselves in part through nostalgic “back to basics”. In the past year and a bit, the mutants through a series of endings in “Disassembled” and Uncanny X-Men, while the Age of X-Man event traumatized them in a loveless utopia. It’s been an interesting ride.

You don’t really need to know any of that, or anything at all of recent or past history of the X-Men, in order to jump into House of X #1. This hits the reset button on the franchise and, while I expect that the past will inform some elements, it can largely be enjoyed coming in blind.

This is arguably the largest, most dramatic change to the X-Men since Grant Morrison, Frank Quitely, Tim Townsend, Brian Haberlin, and Comicraft took over back in New X-Men #114. Jonathan Hickman, Pepe Larraz, Marte Gracia, Clayton Cowles, and Tom Muller kick off a new era that is firmly built on a science fiction grounding. It frames the mutant identity in a new understanding and begins a new conflict with the rest of humanity as human governments and organizations react to the new status quo.

Without going into any details in this section, I can say that House of X #1 takes many of the common themes and elements of decades of X-Men stories and gives them a new spin, both familiar and strange at the same time. All of it is brought beautifully to life through astounding artwork from Larraz and Gracia, taking it to a completely different level. It’s brought together nicely through the design work of Muller, implementing a number of text pieces yielding further information, making it decidedly feel like a Hickman comic.

The digital edition on Comixology is also another instance of having “Director’s Cut” material, including Hickman’s redacted script for the issue, a wide array of the variant covers, and process pages of line art and coloured pages.

It’s a bold new era starting point for the X-Men and I’m excited to see what else is in store.

There will be spoilers below this image. If you do not want to be spoiled on House of X #1, do not read further.

SPOILER WARNING: Below I’ll be discussing the events, themes, and possibility of what’s going on in House of X #1 and beyond. There are HEAVY SPOILERS beyond this point. If you haven’t read the issue yet and don’t want to be spoiled, please stop reading now. You’ve been warned.

PREAMBLE | First Impressions

I had high expectations for House of X #1.

Jonathan Hickman is easily one of my favourite writers currently working in comics. He’s full of mad ideas that you look at and wonder why no one has implemented them in quite the same arrangement before. He’s great at execution and construction for the long game. While each story usually works on a micro individual story-arc/issue level, they also build a large tapestry that tells an even larger tale. One merely needs to look at his previous outing for Marvel telling one grand story that began in Dark Reign: Fantastic Four (with elements you could say were seeded even in Secret Warriors) and ended in Secret Wars. It was wonderful.

Pepe Larraz has been wowing me with his art since Uncanny Avengers. There’s a fluidity of motion and design that evokes the spirit of Alan Davis, Neal Adams, and Bryan Hitch, while adding what feels like an even more gargantuan attention to detail and sense of design. He elevated that even further with stellar showings on Avengers: No Surrender and Extermination. He’s easily become one of Marvel’s premiere artists to me.

When you combine Hickman and Larraz, and couple it with a marketing machine hyping this as the next big thing in the X-Men evolution, expectations were huge.

House of X #1 exceeded those expectations.

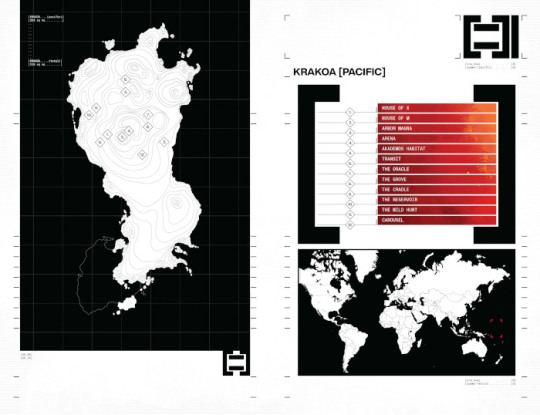

This first issue feels like a sea change for the X-Men, in terms of the team’s status quo and in the approach to storytelling. This is a science fiction story with heavy political leanings. With Xavier pushing the lead, Marvel’s mutants have staked a claim on a new mutant nation on Krakoa, with tendrils through Earth and beyond.

And it’s breathtaking. The artwork from Larraz and Marte Gracia is beautiful. The landscapes and vistas, the designs for the characters, the page layouts, and more, this is a visually stunning book. Larraz has truly outdone himself with the line art, but it’s taken even higher by the sheer beauty in Gracia’s colours. It’s very rich, emphasizing the beauty and wonder of this new world being birthed into existence.

There’s also an interesting choice here in Clayton Cowles’ letters, it’s mixed case. These days it’s not necessarily as unusual not to be in ALL CAPS, but it is different from what we’ve seen in Uncanny X-Men as of late and helps to foster that idea of this being something different. Similarly the text pages scattered throughout from Hickman and Muller that give this the stylistic feel of a Hickman comic and enriches the depth of this new world with more information.

ONE | X Nation

The idea of a mutant nation isn’t a new one. Magneto broached it before and attempted a kind of compound with Asteroid M. Genosha was set up as a mutant paradise for a while. The fallen remnants of Asteroid M served as the X-Men’s home repurposed as Utopia. A corner of Limbo was briefly carved out as a haven for mutants. There was that enclave with Xorn. And Jean Grey kind of set up mutantkind as an amorphous nation within nations given central home in Atlantis during X-Men Red.

More often than not the nation merely serves as a backdrop for the X-Men’s interactions in the rest of the world. I mean, when mutants had their own homeland in Utopia, more stories took place in San Francisco even before the schism that drove half of them off to the Jean Grey School of Higher Learning in New York.

What’s presented in House of X #1 feels different.

Ostensibly, the new mutant nation is headquartered on Krakoa itself, but the implication is that it’s so much broader. The X-Men have seeded Krakoa flowers all over the Earth, on the Moon, and Mars and have grown what feel like embassies and external outposts of the fledgling mutant nation. And it’s the fact that these outposts are within other nations, with the potential of moving a superpowered army unseen and seemingly instantaneously, that has the government representatives met this issue nervous.

While it is a home and a haven for mutantkind, it’s also actively being treated as a political entity. Similar to how Jean argued her case for mutantkind in X-Men: Red, we’ve got ambassadors of sorts checking in with Magneto and two of the Stepford Cuckoos. There are some intrigue elements that sync up with other aspects of the story, but the fact that it’s being used as a tour, a show of force, and an ultimate in order to broker a deal recognizing Krakoa as a nation is an interesting development. It takes it from a place of superheroes playacting at being politicians to actually being politicians. Abrupt as it may be to have Magneto as the face of the operation.

But that’s part of the genius of this play. Like with Magneto siding with Scott upon the founding of Utopia, Xavier and Krakoa is a further fulfillment of Magneto’s dream. A mutant homeland with mutants in control. Every previous time this has happened it’s come to ruin, but it’s always fun while it lasts.

Also, it’s an impressive show of power to have Magneto as the liaison to the rest of humanity. Where Kitty Pryde or Jean Grey would likely be more diplomatic, that isn’t the intent here. Sending out not only one of the most powerful mutants as your face, but also someone who has been in direct conflict with humanity over the years, pushing a mutant independence angle, is a statement that the new mutant nation isn’t something to be trifled with.

TWO | Who are these X-Men?

With the release of titles, creative teams, and team line-ups for the forthcoming “Dawn of X” reboot following House of X and Powers of X, there have been a lot of questions about what’s going on. Characters who have died during recent issues of Uncanny X-Men are alive and well. Characters who were in different configurations and statuses seem to have been changed to more familiar versions and attitudes. So it raises the question for House of X, who are these X-Men?

This first issue doesn’t answer that. I don’t know if we’re going to get an explicit answer that, but I think we’re given a clue on the very first page.

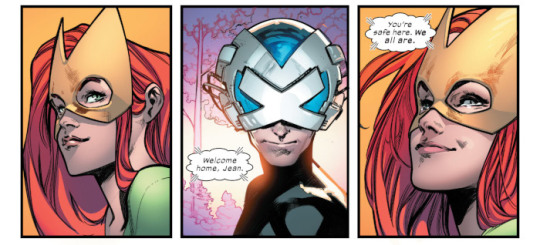

A key element in this first issue is the utilization of the mutant island Krakoa, both as a new home for the X-Men and as refined and adapted through application as portals, habitats, and medications. But in the opening scene, we see a central tree essentially acting as a birthing matrix overseen by Xavier.

The first born being Jean and Scott, I’d guess, then maybe that’s Bobby on the second page with some others. It’s possible that the one guy is even Gabriel Summers. It could be that they’re being rejuvenated, refreshed, and refined through healing properties heretofore unrevealed of Krakoa, but it may be more sinister. There’s a reaching, a yearning towards Xavier that makes me suspect. Are they the characters that we know? Or are they something else? I don’t even know if that’s a question we’re supposed to be asking.

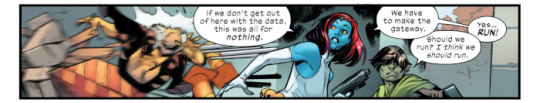

Other than Magneto working front and centre with the team, they’re also working with a number of other traditional villains/antagonists like Sabretooth, Mystique, and Toad. All three have had their dalliances back and forth between the sides of good and evil, but it’s interesting to see them in the fold here. One the one hand, it reinforces the idea that this initiative of Xavier’s is for all mutants and that they’ve come together. But it also raises the question further, how?

I think it’s worth noting that every X-Men character we see fully interacting in the real world has been a villain at one point. Cyclops included, since the last time the world at large saw him before his resurrection he was “Mutant Terrorist Most Wanted #1″.

With characters seemingly back from the dead, characters changed to different versions, characters rejuvenated and healed as it appears that both Cyclops and Banshee are, characters who’ve previously been at one another’s throats, there’s a lingering doubt of how Xavier achieved this. There’s also a happy Wolverine playing with kids, so just think on that for a bit.

THREE | Master of Puppets

Professor Charles Xavier died (again, but who’s keeping track?) during Avengers vs. X-Men back in 2012. Then was brought back in Astonishing X-Men, first as a disembodied psyche caught in the Shadow King’s web and then through the personality sacrifice of Fantomex, inhabiting his body. He referred to himself as “X”, as something new, despite repeatedly claiming that he is the one, true Charles Xavier. His actions, both in his initial appearances and in the subsequent Astonishing X-Men Annual wherein he reunited with the remaining original five X-Men (Cyclops was dead at this point), could be considered manipulative, possibly even evil, callous, and villainous. We’ve not seen him again until now.

With the uncertainty of the origins of the wide cast of characters on the team, whether or not they really are our X-Men we know and love, doubt is cast on Charles Xavier as well. And it’s not just because we only see part of his face. Larraz’s design for Xavier’s new large, portable Cerebro deliberately distances us from him. It’s alien and off-putting, and I believe that’s the idea. I’m unsure whether or not this was the intention, but it also evokes the memory of another villain that Hickman enjoyed using, The Maker. The visual similarities and implication of another hero turned villain can’t be missed.

Consistent with that idea is the portrayal of Jean here. From a real life perspective, there’s an argument that all of the X-Men in House of X and beyond are taking on the costumes and behaviours of their most popular incarnations. In that regard, it would kind of make more sense that Jean would be in a more Phoenix-inspired get up or something similar to her blue and yellow outfit from the ‘90s.

Instead, we get Marvel Girl. Which seems odd to me. It’s not only regressive, but it represents a time period that in-canon Jean supposedly hates. It was, however, a time where Xavier’s somewhat lustful intentions towards his student were more apparent (creepy and disturbing as they are). It further reinforces that maybe not everything is on the level with what’s going on.

FOUR | A New Religion

Religious symbolism and outright textual substance are rife throughout this issue. From the beginning of Xavier acting as a kind of god to the newly reborn mutants beneath a Tree of Life through to Magneto’s proclamation at the end of the story, this first issue is planting the seeds of a new mythology for mutantkind. It’s something that sets them apart from the rest of the superheroes on Earth, giving them an explicit framing as the overseers of the world, but with it, there’s a tie back to how this new nation feels different.

There’s a definitive feeling from House of X #1 of building an entire society. Religion as an aspect of that, both real and implied, but we also get a new language of Krakoan (the glyphs we’ve seen before and again in this issue) and the idea of a broader organizational structure to Krakoa. It’s not just a school any more.

FIVE | Dangerous Beauty

There’s an interesting dichotomy set up in this first issue as well between the mutants and humanity. Of nature versus technology. It’s one we’ve seen before in mutants being the natural evolution of mankind coming into conflict with the sentinels constructed in order to prolong mankind’s grip on power. It tends to lead to the kind of nightmare scenarios of post-apocalyptic futures as we see in Days of Future Past.

Krakoa is an inspired choice for the catalyst of mutant change in the world, delving into some of what was explored in Wolverine and the X-Men, but going steps even further. Creating pharmaceuticals, creating properties similar to Man-Thing’s ability to transport throughout the world, and the various habitats. It’s like the Weapon Plus application of The World in that everything is grown, organic, nature-based objects all ostensibly pieces of the greater Krakoa entity. I wonder if this gives Xavier and the X-Men effective “eyes” all over the world?

It’s also important to recall how dangerous Krakoa has been throughout X-Men history, acting as an antagonist that kickstarted the all-new, all-different era in Giant Size X-Men #1, built out even in Deadly Genesis with the lost team, and the problems had at the Jean Grey School with the baby Krakoa.

And then there’s the flip side.

Orchis is a new organization introduced here comprised of a number of former agents of Marvel’s intelligence community, good and bad, ranging from SHIELD to AIM. And we’re brought aboard the Forge. There’s a fearful symmetry to it, a station close to the Sun building machines to counteract whatever it is that Xavier is ultimately doing. At the Forge’s heart what appears to be a new kind of Master Mold sentinel, decked out in some of the same colour schemes that we recently saw with the golden sentinels of ONE in Uncanny X-Men.

I can only imagine that this is going to wind up well.

We’re shown a face that we’ve not seen for a while (outside of solicitation covers), since I thought she was an “ordinary” human again, in Karima Shapandar. It’s kind of sad, though, as her Omega Sentinel protocols seem to have been reactivated.

SIX | We Can Be Heroes

The presence of the X-Men within the broader Marvel Universe framework can be problematic at times. It’s one of the reasons why they’ve often been shuffled off to parts unknown, set up as a rag tag band of fugitives, and limited in number to the point where they’re culturally, socially, and politically insignificant. Because the heart of mutant existence within the Marvel Universe is one of intolerance.

Mutants are feared and hated, hunted down, enslaved, or executed. While it works extremely well as an analogy for real life racial and sexual bigotry and prejudices, it takes on a different level of problem in the face of a world filled with superheroes. For superpowered people who aren’t mutants, you wonder about a couple of things, such as why the general populace even makes a difference and why non-mutant heroes don’t seem to care about mutant prejudice.

That latter one has been approached a few times previously, as recently as this latest volume of Uncanny X-Men, and it always seems strange. It’s like the question that you see raised in Swamp Thing and Marvelman and later The Authority of the realistic application of near limitless god-like powers as a force for change; if you’ve got these powers, why don’t you do something to change the world’s ills?

It really undercuts the heroism of teams like the Avengers and the Fantastic Four, because it eliminates them as defenders of a universal justice, but merely teams that fight for the status quo. And so eventually the X-Men get shuffled off to Chandilar.

I think it’s great that House of X #1 goes straight for that jugular. Cyclops’ confrontation with the Fantastic Four beautifully displays his integration and friendliness towards the other heroes, that he’s happy for Ben’s wedding, but still at odds with them when it comes to overall mutant rights. Including those of Sabretooth, who admittedly just robbed a place and probably killed a few dozen people. So, it’s not like the Fantastic Four are in the wrong in trying to apprehend Sabretooth, but it’s reinforcing bits of the laws of the state versus possible ethical or moral concerns.

This scene also reminds us that mutants are everywhere. They can be anyone within society, anyone’s husband, wife, mother, father, friend, daughter, family, neighbour...anyone’s son, including Franklin Richards, son to Reed and Sue. It helps underline that compassion, understanding, and fighting for what’s morally right is something that really should be at the forefront here. And that Cyclops and the rest of Xavier’s new nation of Krakoa are making it known that they’re not going to accept the intolerance any more.

It’s also interesting the incorporation of the broader Marvel Universe as a catalyst for this confrontation in that Sabretooth, Mystique, and Toad were stealing information from Damage Control. It’s a neat bit of the shared universe and presents something potentially nefarious about Damage Control appropriating broken Stark and Richards tech. Though, we are left wondering, what did they steal?

SEVEN | Nothing As It Seems

One of the central themes we’re presented with in the ambassadors’ tour through Krakoa as led by Magneto is that nothing is quite as it seems. It’s even mentioned explicitly through the dialogue when the ambassadors are discussing the deal as lain out by Xavier. Worrying about the drugs, but even more about the amnesty. The terms of the amnesty aren’t actually stated here, but the gist seems to be that all mutants, criminal or otherwise, need to be set free (and presumably allowed passage to one of the gateways to Krakoa), if the country is to take part in the life-saving drug aspect.

Now, there’s an in-story payoff to the ambassadors statement, in that they’re all plants of one form or another, working for different organizations in order to gain information or surveillance on one thing or another and in Magneto’s ulterior motive for gathering them, but it feeds back into that tingling suspicion from the first page.

Something feels off. Something feels wrong. But that could well be the point. The seeds of doubt may well be planted intentionally for Xavier’s plan and the appearances of the characters. It could well be that we’re supposed to think that something hinky is going on, just to keep us in suspense. And that everything we’re seeing, everything we’re being told, really is the truth.

CONCLUSION | A More Perfect Union

As I said previously, House of X #1 exceeded my expectations.

Hickman, Larraz, Gracia, Cowles, and Muller came together to produce what is one of the most exciting and intriguing first issues that I’ve read in a very long time. Every single element from dialogue to line art, colour to letters, to cover to design gels into one massive stroke of storytelling. Every single thing within the comic adds another layer to immerse yourself into this brave new world of mutant merriment.

This is an incredible start to this new era and I am very excited to see what comes next week in Powers of X #1. Especially in how it relates back to House of X #1. These issues are apparently meant to be paired, but how exactly remains to be seen. I find that interesting, since PoX is apparently set in a different time frame.

d. emerson eddy is not an island.

14 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

SELENA GOMEZ - LOSE YOU TO LOVE ME

[6.17]

We like it like a lose song, maybe...

Alex Clifton: I'm fascinated by songs where singers air their grievances and fans all know which specific people they are calling out. It's one of the reasons I fell in love with Taylor Swift's music way back in the day; I love a good gossip. Over the past eight years, I've worried about Selena with relation to Justin Bieber constantly. Not my relationship, I know, but he seemed like an immature asswipe when Selena could do much better. She's avoided discussing Bieber in much of her previous music. Even the songs that were definitely about him ("Love Will Remember," "The Heart Wants What It Wants") were written in abstract terms so you'd only really know the subject if you spent time following the Selena/Justin drama. Cut to "Lose You to Love Me," where she goes for the kill: "in two months you replaced us," a clear reference to Justin suddenly moving onto his now-wife Hailey. Such a vulnerable and specific track is a strong statement from Selena, who in the past two years has stayed relatively out of the public eye and is now ready to share parts of her story. There's no red scarf here, not that level of minutiae, but frankly she doesn't need it when much of her toxic and turbulent relationship with Bieber played out in the tabloids. And god it's so cathartic. It's an acknowledgement of hurt and anger but a phoenix move for Selena; she's rising from the debris stronger than before, and she wants you to know it. I'm so pleased for her. In the immortal words of her friend Taylor, "she lost him but she found herself and somehow that was everything." [8]

Wayne Weizhen Zhang: A decade into her career as one of the world's most popular artists, it's worth noting that Selena Gomez's ascent to fame was improbable. She didn't have the most powerful voice, dance skills, or even a number one hit -- but especially early in her career, she was able to leverage her very public personal life to fuel interest in her music: a Disney fan base, a feud with Demi Lovato which the media loved to cover, membership in Taylor Swift's entourage, and, of course, most significantly, an infamous on-and-off-again relationship. But over the past four years, Selena has developed an effective signature vocal style -- hushed, controlled whispers which burst into moments of pop brilliance -- which makes it clear that her music is more than capable of standing on her own. So it's all the more frustrating then, that after seeing how stellar her music can be removed from celebrity context, that the first song we get off her long awaited third solo album is yet another song about Justin Bieber. But while I initially rejected "Lose You to Love Me" as a regression into formulaic pop balladry, there's a surprising amount of depth. The song sounds like genuine healing, coming from an artist singing her truth. Her voice is soft but powerful, emotive but not overwrought, reflective but not nostalgic. A line like "now the chapter is closed and done" could land cliché and hollow, but Selena sings it like someone who finally took a breath of fresh air for the first time in years. This is all to say: if we have to listen to this one last song about Justin Bieber, at least it's the first genuinely compelling one, and a step in seeing her evolution as an artist and celebrity. [7]

Leah Isobel: When Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake broke up, he got to project his messy breakup feelings outward; he produced imagery about spying on her doppelganger and fantasizing about her death. But for Selena -- Timberlake's 2010s tabloid counterpart -- unrepentant sleaze is a much riskier proposition, at least on the charts. Instead, she sublimates her anger, returning to the baby-voiced Julia Michaels wheelhouse. The mass of vocal effects on the chorus is surprisingly effective, but for an artist who was briefly one of the more progressive voices on Top 40 radio, this defanged "Everytime" is a little disappointing. [4]

Katherine St Asaph: Piano ballads are to music what Joseph Campbell is to narratives. Not a song but a beat on a storyboard -- barely a storyboard, even, but tabloid kerfuffle. [1]

Michael Hong: Selena Gomez's career has long mirrored Demi Lovato's, from child acting stints on Barney & Friends to the release of their fifth studio albums within a week of each other in 2015. Here she goes for something similar to Lovato's "Sober," released last year as a sort of song-as-a-statement -- though Gomez's statement is more uplifting than heartbreaking. "Sober" was a rare instance where Lovato never pushed her voice too far, with its statement made more effective by the events that followed; her confession came across as authentically personal as it unfolded in real-time. "Lose You to Love Me," like "Sober," is stripped down to its bare bones for a more intimate feeling, but here, it's questionable whether the quiet dynamic is one of Gomez's stylistic choices or a symptom of her limited vocal range. There are interesting touches, like the echo-chamber effect on her voice for the line "in two months, you replaced us," which makes the following lines about being broken all the more devastating. But there are also moments like the choir vocals on the final chorus that are predictably overwrought. While "Lose You to Love Me" is a delicately gorgeous and uplifting track, its statement is diminished by how tiresome the Gomez-Bieber narrative feels. We're no longer watching her relationship end in the present, but instead seeing Selena Gomez finally claim closure on a relationship that has long since run its course (at least in the public eye). More interesting is the single released the following day, which features the offbeat personality she's carved out for herself over the past few years and is equally effective at demonstrating that Selena Gomez has moved on. [6]

Alfred Soto: In a tradition of self-reflexive love songs, she tells us she'll sing the chorus off-key (it sounds okay to me). Maybe this line represents one of Selena Gomez's contributions. If I see Julia Michaels, I think of phony uplift, of which the chorus has hints. Then Gomez counters with a slightly hoarse, un-melodramatic dropping of the line, "You promised the world and I fell for it. A performance with grandness in its bones, and it almost succeeds. [6]

Stephen Eisermann: I'm a sucker for big, cathartic choruses, but the verses really let me down here. Between Selena's weird vocal, the melodramatic strings, and the unintentionally funny lyrics (I'm not convinced that the whole singing off-key line isn't a bit that she's delivering with a wink), it's really hard to take the track seriously. But when that big booming chorus hits, backing vocals and all, you can almost feel Selena letting go of everything Bieber did to her. And that, that's lovely. It's also why the other track released after this is so much better. [5]

Joshua Copperman: A song that's perfectly in tune with 2019-type sad music yet unafraid to be huge. It doesn't have the stakes of "Praying" or the bounce of "It Ain't Me," but that's not a problem. The gang vocals that plagued so much of mid-to-late 2010s pop -- including Selena Gomez's own music -- blossom into a full choir, beautifully contrasting with her usual hushiness. It should be Real Music-y --even the lyrics are less playful and twee than Michaels and Tranter usually go, barring the "killing me softly" shoehorn and obvious title -- but because of how thin Gomez's voice sounds, it's not. (The most Michaels-y touch is the backing vocals going "to love, to love" instead of "to love me, love me" like I'd thought, as in "I needed to lose you to love again at all.") The pop most beloved non-mainstream artists are producing is proudly campy, and that's great! Gomez seems to be headed in that direction too with "Look at Her Now," but this unexpected pivot to pathos inexplicably works thanks to the strategic arrangement and lyricism. [9]

Kayla Beardslee: It's fascinatingly difficult to determine where Julia Michaels' style ends and Selena Gomez's begins, and the whispered melodies and "Issues" violins here don't help. Although Gomez's voice can sometimes be aggressively pleasant, she digs in enough to communicate real emotion here, and the choir backing vocals are surprisingly powerful. The song makes a poignant, if heavy-handed, statement about maturing and finding your identity, amplified by this being her comeback single: Ariana has "thank u, next," Miley has "Slide Away," and now Selena has "Lose You to Love Me." [7]

Jackie Powell: While Julia Michaels has commented that Selena Gomez is indeed a songwriter, I still don't believe that's the proper term to describe her contributions to music. Gomez is a storyteller first and foremost. That's the term: storyteller. Sometimes those can be interpreted as synonymous or givens of each other, but let's remember that Gomez has been telling stories since she was seven years old. Her art is most successful when she's in control of her narrative and knows exactly what story she's about to tell. When she has the opportunity to perform her stories, she goes all out and sells it exactly as someone who's been on stage since childhood can. That may sound like something Ariana Grande has done in the past year or so with "thank u, next," since both "Lose You to Love Me" and that highlight some of the most dramatic breakups in pop culture. But as Tatiana Cirisano pointed out for Billboard, Gomez's approach is the contrapositive to Grande's. Both cuts are relatable and have a commitment to empowerment and autonomy, but Gomez makes her track a moment without a teen movie pastiche. Her choice to emphasize and crescendo on the lyrics "In two months you replaced us" and "Made me think I deserved it" speak loudly. This track is all about its dynamics in its minimalistic glory. Imagine Gomez was performing a monologue. That's the type of choice a storyteller makes. Justin Tranter and Michaels provide the melody and the nuts and bolts, but the concept is clearly all Gomez. The backing vocals in each chorus from Tranter and Michaels are symbolic of what they've meant to Gomez over the years. They've been by her side every step of the way and have lifted her up. That's beautiful. What's also beautiful is if I ever wanted to learn more about Justin Bieber, the lyrics "Sang off-key in my chorus / 'Cause it wasn't yours" tell me all I need to know. [8]

Josh Buck: The Selena Gomez x Julia Michaels joints never miss. [6]

Abdullah Siddiqui: Selena Gomez's discography in the last four years has largely consisted of stylistic meandering and incomplete ideas. She hasn't quite been able to settle on a sound or a narrative. This feels like she's starting from scratch. It's a pretty solid place to start. [7]

[Read, comment and vote on The Singles Jukebox]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Nouvelle Vague: Rebels with a Cause

Over the course of its lifetime, cinema has undergone various degrees of evolution in technique, style and theory. From its starting years as a silent, black-and-white medium of spectacle to becoming a vehicle of social commentary, different eras populate the history of the art form— one of which is La Nouvelle Vague or the French New Wave, an art movement widely known for its stylistic experimentation and upending of conventional ideals. But to further understand why and how French New Wave came to be would require examining the previous generation of films and cultural subtexts, tracing its origins and development through the years, identifying essential intentions and theories borne out of its inception, and assessing its legacy since its passing.

Given that French New Wave’s creation was necessitated mainly as a response to the prevailing trends of the previous era, it is important to investigate the overall landscape before its arrival. Prior to French New Wave, mainstream films were heavily tied to the studio system restricting filmmaking within the walls of production houses. Not only in space, it limited films in terms of overall aesthetic— actions remained in stationary shots, artificial set designs mimicked the environment of theatre productions, plots had to be revisited to accommodate the rigid structures. Dominance of big studios also provided a challenge for aspiring directors during the period in the form of preference towards established filmmakers and their mastered craft (Grant, 2007). With such restrictions, a choice between technique and experimentation became a recurring dilemma and more often than not, prevailing trends pointed to the former.

Even a bigger motivator for the movement was the cultural climate of its belonged era. The question on whether Germany’s occupation of France could have been mitigated if not avoided lingered over the heads of the elite. Such proximity to the war and failure in avoiding its arrival brought upon the whole of French society an air of simmering political unrest continuously stifled by the public’s eagerness to regain normalcy. Fortunately, it wasn’t long before France started to incur financial recovery. Unfortunately, the rush towards economic stability meant a surge in capitalistic tendencies. Thus, consumerism made its expected return with little to no restraint forcing mainstream cinema to cater to the sensibilities of the bourgeoisie and their demands for movies steeped in romanticism and comedy. Coupled with growing materialistic attitude, television’s entry into the picture presented a shift on media consumption wherein it was no longer expected of the public to go out in search of entertainment, instead entertainment was supposed to find them (Crisp, 1993). With this, French cinema underwent a deep reevaluation regarding its place in France’s postwar cultural scene specifically whether it belonged in the upper echelons of “highbrow art” or was better off in the business of the bourgeoisie.

Integral to the establishment of the movement were the precursory dialogues among intellectuals and cinephiles about the state French cinema, most of which centered on the impact of external forces enumerated above. Cahiers du Cinema, a monthly French publication focusing on film criticism and theory, became the place of assembly to most of the leading voices of French New Wave which included the likes of Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette and through their writings, established core intentions carried by the movement. Francois Godard, a notable writer for the magazine, embodied much of what the movement essentially stands for— that, in spite of the iconoclastic reputation that has come to be associated with it, so much about French New Wave is rooted in the belief of preserving cinema’s artistic value. Throughout his career as a filmmaker, Godard translated his love of moviemaking through frequent acts of homage— he made in-film references to other works he held in reverence, borrowed trademarks from respected filmmakers, centered character-driven conversations on cinema and at one point, even gave Jean Pierre-Melville a cameo role (Wiegand, 2012). What these constant meta-discussions regarding cinema revealed was not an effort to destroy its very language but rather an intention to interrogate its grammar and meaning towards a more democratic expression. Such belief in freeing films and their methods of creation from constraints brought by big studio houses and the rule of market became the driving force which helped spur French New Wave into action.

Although Cahiers and its critics managed to develop a strong presence among film enthusiasts who echoed the same concern of liberating cinema, it was only after the publication of A Certain Tendency of French Cinema when French New Wave was propelled into the nation’s consciousness. The essay which voiced out grievances against popular cinema in uber-polemic writing became the unofficial manifesto of the movement. Francois Truffaut, the author of the essay, lambasted the prevalence of what he called “Tradition of Quality”, a tendency of French studio system to favor “…literary adaptation, which caused French films to become increasingly verbal and theatrical.” (Cook, 2016, p. 343). Moreover, he scorned the glorification of screenwriters over directors which he argued imposed rigid rules on filmmaking thereby diminishing the director’s vision for the film.

Out of the essay’s publication, politiques des auteurs or auteur theory was highlighted as a central argument in the push toward greater authority of directors over film productions. At its core, auteur theory championed the director as the principal creator of a film, above screenwriters and film producers, comparable to authors having full creative control of their literary works. Although not a new concept at the time, Truffaut’s use of auteur theory in the essay accompanied by his stark denunciation of the studio system facilitated auteurism’s transition from a mere form of critical theory to a practicable filmmaking approach. The effect of French New Wave and its promotion of auteur theory on contemporary French cinema was seen in the surge of films that employed location shooting and practical effects such as natural lighting and live sound— aspects of filmmaking directors were now able to dictate without third-party interference (Neupert, 2007). Such filmic language which puts emphasis on low-budget production and documentary style filmmaking afforded directors leeway in experimentation and would later dominate the film industry displacing studio houses from its norm status somewhere in the 60s (Crisp, 1993).

Further impact of the French New Wave was observed in the successes of its directors not only in the box office but also in film festival circuits. Such was the case of Truffaut’s directorial debut, The 400 Blows, in 1959 where he was awarded Best Director in Cannes Film Festival in spite of being banned as a critic from the same festival the year before. In years to come, French New Wave directors would go on to achieve varying degrees of recognition but more astounding about these achievements was the fact that most of these critics-turned-filmmakers were under the age of 30. In effect, the rise to prominence of these young directors lead to increased numbers of new talents being hired in the industry and more importantly, “…granted the young filmmakers an unconditional command over every facet of the creative process.” (Fournier-Lanzoni, 2002, p. 212).

Even worth investigating are the ramifications of French New Wave around its neighboring countries and across the Atlantic which began to adopt principles tied to it. For instance, familiar imprints can be recognized in successive New Waves and film movements most notably in American New Wave taking great inspiration from auteur theory and Dogme 95 whose strict obedience to bare-bones style of cinema invoked the realism of French New Wave. Arguably, a more long-lasting legacy left can be attributed to its use of radical filmmaking techniques. The utilization of jump cuts in many films from the era, particularly in Godard’s revolutionary Breathless, demonstrated innovative and playful approaches to continuity editing and storytelling (Sterritt, 2007). While deemed controversial at the time, jump cuts and long takes became staple trademarks in French New Wave films and would later flourish into a dignified form of creative expression employed in future works outside of the movement .

Perhaps the most apparent evidence of the movement’s influence is found in the longevity of careers of its pioneers post-French New Wave. Well into the 21st century, Cahiers directors sustained a prolific presence in the industry with Chabrol and Rohmer continuing to release films as late as 2007 before their retirement and subsequent passing. Godard, the last surviving member of the group, maintains an active career having recently released a film essay, The Image Book, in 2018 which competed and won a special prize in that year’s Cannes Film Festival. Future generations of filmmakers also remain indebted to French New Wave for paving the way to an environment more welcoming of young talent and more respectful of their creative vision. Directors being able to attach their names to their creations owe much of that privilege to the movement’s campaign for authorial role of filmmakers. Just by the mention of “Tarantino film” or “Fincher film”, one could expect a certain aesthetic or style unique only to those names— a custom made possible by auteur theory. In summary, the impact of French New Wave not only to filmmaking but also to the very industry it belongs to cements its place as a formative era in film history and while it had passed its peak many decades ago, the spirit of rebellion that energized lovers of movies into taking arms in defense of the art form continue to ripple in the whole of cinema.

Bibliography:

Cook, D. (2016). A history of narrative film (5th edition). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Crisp, C. (1993). The classic French cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Fournier-Lanzoni, R. (2002). French cinema: From its beginnings to the present. New York: Continuum.

Glenn, C. (2014). Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut: the influence of Hollywood, modernization and radical politics on their films and friendship. (Master’s thesis).Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina.

Grant, B. K. (2007). Schirmer encyclopedia of film (Vol. 2). Detroit: Schirmer Reference.

Grosoli, M. (2014). The politics and aesthetics of the "politique des auteurs". Film criticism, 39(1), 33-50. Retrieved August 7, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/24777962

Hillier, J. (1986). Cahiers du Cinéma: the 1950s: neo-realism, Hollywood, new wave. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Neupert, R. (2007). A history of the French new wave cinema. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Sterritt, D. (1999). The films of Jean-Luc Godard: Seeing the invisible. Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, K. & Bordwell, D. (2003). Film history: an introduction. (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Truffaut, F. (1976). A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema. In B. Nichols (Ed.). Movies and methods: an anthology (Vol. 1, pp. 224-236). Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. (Original work published in Cahiers du cinema 31, 1954).

Wiegand, C. (2012). French new wave. Harpenden, Herts: Pocket Essentials. (Original work published 2005)

0 notes

Text

Women’s Fashion Over Time

In its vast timeline, the history of fashion in art reveals a complex socio-economic system influenced by a culture of valuing individual collectives in a world of dynamic change. It is a unique system in that which its influences are found in close quarters; a grapevine of cultural impact showing people influencing people. The ensembles worn by subjects in various paintings and sculptures present us with a glimpse into the socio-economic conditions under which fashion became a commodification of social status and a symbol of societal and cultural value. As cultural events and new political climates rise, causing shifts in values and general rules of fashionable appearance tastes in fashion appears to change. Yet the relatively stable constant in notions towards fashion is a prescribed label of class, and therefore, your worth and position in society, associated with the clothing you wore. In a series of six costumes inspired by the Early Renaissance, the High Renaissance, the High Renaissance in Europe, Baroque art, Rococo to Neoclassicism, and Romanticism, I will break down the fashion trends of each period, focusing on iconic features of each fashion period and briefly explaining the cultural context of each garment.

The Early Renaissance

This costume is based on the ensemble worn by Giovanni Arnolfini’s wife in the painting Giovanni Arnolfini and His Wife by early Renaissance painter Jan Van Eyck. A popular staple piece in early Renaissance fashion was the houppelande which was carried over from the fashion of the middle ages. In The Concise History of Costume and Fashion by James Laver, he describes the general appearance of the houppelande as a garment that fitted the shoulders and was loose below, with a belt at the waist; the houppelande is what will later be known as ‘gown’.[2] This replication of a typical houppelande has a high collar and extremely long sleeves, fur trimming and fur lining, and hanging tippets from the edge of the sleeve to the back of the gown. The gown itself is extremely long, ballooning outward from the waist. The houppelande could be made in a selection of fabrics such as wool, silk, and velvet[3], and were could be dyed a rich, vibrant colour as seen in Jan Van Eyck’s painting. Since the middle ages, the use of fur in fashion had become symbolic of wealth and importance and was oft worn by nobility.[4] Since fur was difficult to come by, it was an elitist luxury used in excess by middle and higher class people, establishing a social distinction between them and the lower-class through their clothing. As for the headdress, at this point, not much has changed since the middle ages in terms of style. However, the custom of covering mature and married women’s hair was becoming less strict, and we see more women revealing their hairstyle beneath their headdress.[5]

The High Renaissance

This High renaissance costume is based on the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci. The During the High renaissance, many cultural trends such as the rise and spread of books, the expansion of trade and exploration, and the increase in power and wealth of national monarchies in France, England, and Spain influenced tastes in fashion and the dynamic changes fashion underwent, as well as the idea of the modern ‘trendsetter’.[6] The essential garment for the High Renaissance woman was the gown. Its general features were the bodice, a skirt, and sleeves. The complex ensemble of the gown during this period can be seen in da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. The gown could be made from luxurious materials such as silk, velvet, and lace, worn with lavish jewelry, and decorated with intricate patterns of stitching and embroidery.[7] While the gown silhouette was common across social classes, the distinction lies within the materials used. Although the wealthy and powerful used expensive textiles for their gowns, the lower-class was still capable of emulating the gown with the materials they had access to such as wool and cotton.

The High Renaissance in Northern Europe

My iteration of Northern European High Renaissance fashion is based on Hans Holbein the Younger’s Portrait of Christina of Denmark. This portrait demonstrates the conservative side of fashion that was flourishing alongside a bold, vibrant movement that was challenging established trends. The model adorns a dark, velvet gown with a high collar; underneath we see a glimpse of the ruffs from her high collared undershirt. The ruffs were a common feature of the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, typically characterized as an upright, stiff collar that ruffles around the neck; ruffs were commonly adorned by noblemen and noblewomen.[8] Now, Holbein’s Portrait of Christina of Denmark does not show the typical extravagant ruffled collar, which could have been a stylistic choice by Holbein to allow the fur lining and trim of the subject’s outer gown to stand out, and remain the statement feature representing her wealth in the painting. The large size of the outer gown appears to further imply how much fur the gown is made of.

Baroque Art

The Baroque artwork I’ve based this costume design on is Vermeer’s, Girl with a Pearl Earring. The Baroque period introduced innovations to the popular sixteenth-century gown. At the time Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring was composed, seventeenth-century fashion had already gone through several evolutions. Stomachers, which was either a v-shape or u-shape panel meant for decoration and structure, had become stiffer and flatter and elongated past the line of the waist.[9] Replacing the trend of using wired hoops, or farthingales, to give body to the skirt was the petticoat. The petticoat was a practical solution to the everyday issues of functionality women faced with farthingales. Petticoats made of cotton or wool were perfect for warmth, while more fashionable petticoats were made of taffeta, satin, linen, or a combination of starched fabrics.[10]

Rococo and Neoclassicism

This costume was inspired by Vigee Le Brun and her artistic style which can be described as being a mix of rococo colours with elements of the Neoclassic style. As a prolific French portrait painter, one of her prominent subjects for portraits was Marie Antoinette, the Queen of France who despite her tumultuous life in the public eye, was a fashion icon. The genius in Le Brun’s craft lies in her vast knowledge of current fashion and her awareness of the power of appearance.

I based this costume on Vigee Le Brun’s, Self Portrait in a Straw Hat. In the painting, Le Brun is wearing a variation of the robe en chemise which emerged during the late eighteenth-century period as tastes in fashion moved away from the early period’s penchant for fuller-bodied skirts.[11] While its design echoes elements of early Rococo style, the robe en chemise was a gown made simple. These dresses were usually made of sheer, white cotton, with high waists and wrapped with a decorative satin sash; its slender silhouette was inspired by the fashion of ancient Greece and ancient Rome.[12] These dresses could also come in various colours, such as the rose-gold coloured dress Le Brun is wearing in her self-portrait. With its sheer material and low-cut neckline, the robe en chemise gained widespread attention because of its revealing nature; until this point, the gowns we’ve seen have been voluminous and covered much of the female body. Yet, this scandalous fashion found its way into the wardrobe of royalty, and most likely, the wardrobe of some upper-class women who wanted to be revered for wearing the latest fashion. This portrait of Marie Antoinette wearing a robe en chemise was painted by Le Brun.

Romanticism

Based on Delacroix’s, Liberty Leading the People, this costume is an iteration of the symbolic fashion of the woman in his painting. She is Liberty; she represents freedom, in an image that evokes a triumphant revolution as she leads people on the battlefield. The Romantic movement differed vastly from the current situation in early nineteenth-century France, which was characterized by social unrest and civil war between the bourgeoisie and the working class.[13] Romanticism was mostly a reaction to the modern realities brought on by the industrial revolution; the romantic movement in art reveals a desire to escape these modern realities, a theme which Delacroix’s painting emulates perfectly.

Liberty Leading the People encapsulates the transitional period between Neoclassicism and Romantic sensibilities.[14] There are neoclassical elements in Liberty’s appearance, but most prominent is her dress. The painting feels reminiscent of the time of unrest during the French Revolution, which Liberty embodies in her wearing a robe en chemise, referred to simply at this point as ‘a dress’. In general, dresses of any kind were lighter and much sheerer than garments from the eighteenth-century but the general features of the dress were kept the same: made from any selection of fabrics and usually white or light in colour, short sleeves, high waists and long, straight skirts.[15]

From this brief overview of women’s fashion over time, it is evident that notions towards dress and appearance, and how we tend to associate certain styles of fashion to specific groups of people and/or cultures have not changed. Although fashion continues to evolve, the same old fashion trends appear and disappear, then reappear; reinvented or inspiring a consequent fashion movement. There is a romantic sensibility in the way we often tend to return to past fashion trends. It begs the question if there will ever be a completely fresh fashion movement, or will our futile attempts remain the shells of historic innovations in fashion from the past. Nevertheless, as one of few primary resources for contemporary fashion designers, these artworks reveal the true impact of fashion and art as they continue to influence fashion and social cultures in our modern world.

––––––––––––

Footnotes

[1] Ibid. 600.

[2] Laver, "The Concise History of Costume and Fashion: Laver, James, 1899-1975: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming." Internet Archive. January 01, 1969. Accessed July 17, 2020. https://archive.org/details/concisehistoryof00lave/mode/2up, 64.

[3] Pendergast, Sara, Tom Pendergast, and Sarah Hermsen. Fashion, Costume and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages. Vol. 3. Detroit: U.X.L, 2004, 450.

[4] Ibid. 624.

[5] Ibid. 488.

[6] Ibid. 469.

[7] Ibid. 477.

[8] Ibid. 482-483.

[9] Ibid. 521; 525.

[10] Ibid. 523.

[11] Ibid. 570.

[12] Ibid. 570

[13] Hurley, Clare. "French Romantic Painter Eugène Delacroix at the Metropolitan Museum in New York." French Romantic Painter Eugène Delacroix at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. December 20, 2018. Accessed July 22, 2020. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2018/12/20/dela-d20.html.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Pendergast, Sara, Tom Pendergast, and Sarah Hermsen. Fashion, Costume and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages. Vol. 3. Detroit: U.X.L, 2004, 622.

–––––––––––

Bibliography

Hurley, Clare. "French Romantic Painter Eugène Delacroix at the Metropolitan Museum in New York." French Romantic Painter Eugène Delacroix at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. December 20, 2018. Accessed July 22, 2020. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2018/12/20/dela-d20.html.

Laver, James. "The Concise History of Costume and Fashion: Laver, James, 1899-1975: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming." Internet Archive. January 01, 1969. Accessed July 22, 2020. https://archive.org/details/concisehistoryof00lave/mode/2up.

Pendergast, Sara, Tom Pendergast, and Sarah Hermsen. Fashion, Costume and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages. Vol. 3. Detroit: U.X.L, 2004.

0 notes

Text

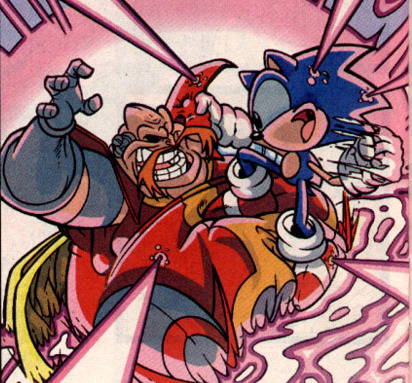

Robotnik Art Historia- Part One: The Early Days

Hey there folks! A while back, I made a post detailing the stylistic evolution of Archie Sonic artist icon Patrick Spaziante regarding his particular depiction of Robotnik. It went over a lot better than expected, and since that time I’ve been mulling over doing something of a sequel- and that time is now.