#introducing Sidon and the fact that i was not very creative in coming up with a name

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

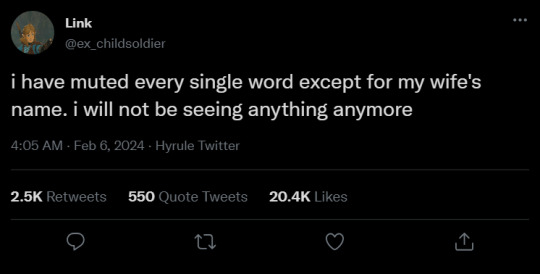

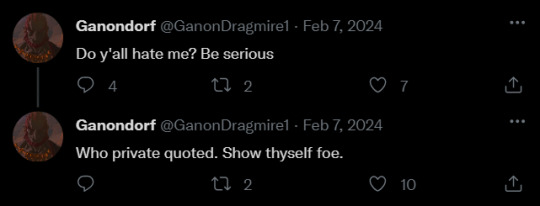

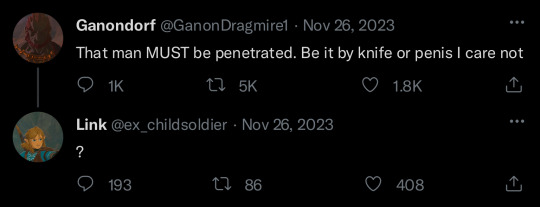

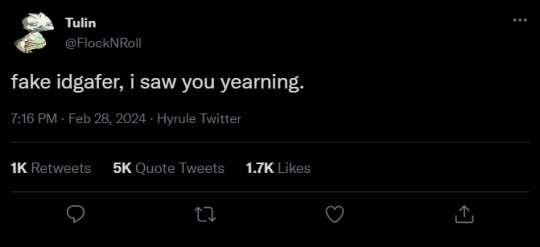

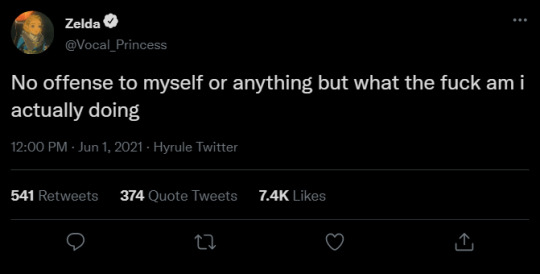

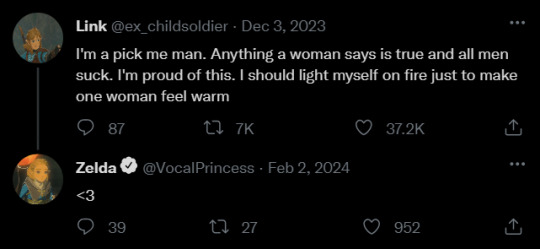

Hyrule Twitter Shenanigans pt3

—————

-1)

-2)

-3)

-4)

-5)

-6)

-7)

-8)

-9)

-10)

-11)

-12)

-13)

Hyrule Twitter Shenanigans pt1

Hyrule Twitter Shenanigans pt2

<3 Art semi-inspired by tweet #5

#and we're back !#guess who still doesn't know how to format these#Hyrule Twitter pt3 babyyy#decently link centric as per usual#introducing Sidon and the fact that i was not very creative in coming up with a name#fr if y'all ever has username ideas for characters i haven't done yet#feel free to slide them bc my head is empty#ganondorf being a menace#as per usual#triforce triad#tears of the kingdom#zelda#zelink#link#ganondorf#tulin#sidon#botw#socmed AU#Hyrule twitter AU

229 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Greek Novel Across the Centuries: A Comparison of Chariton and Achilles Tatius

The Greek novel is not a monolithic genre. It can be divided into an Early and Later Period, each with its own authorial characteristics and audience composition. To explore the differences between the first and later novels I will cite Chariton’s Callirhoe (c. 50 CE) and Achilles Tatius’ Leucippe and Clitophon (c. 110 CE). This exploration will illuminate what the inspirations for the genre were and how broader cultural shifts fundamentally altered, co-opted, and expanded the original functions of the genre.

The early Greek novel (and to a point the genre as a whole) has the spirit of Greek tragedy in the form of historical narrative. With the Mediterranean united by Roman arms and the Greek tongue, this period experienced a heightened demand for the written word. As power grew more centralized in Rome, the educated literati of the empire’s leadership responsibilities diminished and their interest in leisure and entertainment rose. Prospective writers needed to be engaging, and there were several options to consider. First, there was the epic, Greece’s oldest literature. Epic verse was still culturally important, but its relevancy was on the decline: it was tried, old, and imperfect for communicating the zeitgeist of the Roman Age. Scattered lines of epic poetry do appear in Greek novels, but writers turned elsewhere for their inspiration. The theatre of the ancient playwrights still embodied a powerful force for drama, but plays required actors, audiences, and stadiums to live up to their potential; plays were performed in a specific space at a specific time, and the demand was for texts meant to be read, not scripts meant to be performed. The pioneers of the novel borrowed from Greek drama dramatic structure and tension (much as the earliest English novelists did) but considered their search for an appropriate form.

They found it in historical narrative. History was the genre defined by long prose narrative, a form Herodotus was among the first to pioneer. His use of prose narrative in part challenged epic poetry’s monopolization on Greek storytelling, and it provided an easily imitable form for future authors to use. Its adoption by writers of the coming generations, starting with Thucydides, cemented the prose narrative as one of Greece’s written forms, on par with the meter of epic and drama. Since what the new literati was fundamentally entertaining stories, it comes as no surprise that the novel’s pioneers turned to the form for storytelling for their new works.

It is equally unsurprising that Callirhoe, the earliest known Greek novel, prominently features and references historical events and figures (albeit in a heavily fictionalized manner). To briefly summarize the story: Callirhoe is the daughter of Hermocrates, ruler of Sicily, and is the most beautiful woman in the world. Chaereas is similarly handsome, and the two fall in love. Shenanigans ensure, and Callirhoe is captured by pirates and sold into slavery. Increasingly powerful men begin to fight for Callirhoe’s marriage: first Dionysius, an aristocrat of Miletus, then the Persian governor Mithridates, and then even the Persian king Artaxerxes. All the while, Chaereas attempts to get his wife back in increasingly spectacular fashion that culminates in fielding Egypt’s army against the Persian Empire. They are finally reunited, and the novel ends. Obviously, the novel is set in the real world, specifically around Sicily after the Peloponnesian War (so post 404 BCE). There was a famous Syracusan general named Hermocrates, whose anonymous daughter married a Dionysius of Syracuse before dying young. That’s all the history that is in the novel, though. From this fact we can see that the novel is not meant to be a creative (or bad) reading of history but a story of love and adventure grounded in a familiar world. From a temporal perspective what Callirhoe does is very similar to a novel written in the present day that uses Queen Elizabeth I’s court as a setting and uses certain historical personages but makes no claims about actual history.

Chariton plays his novel straight: the text is not trying to be anything other than a novel. In other words, it is primarily a vehicle for reader enjoyment. The final section of the novel begins: “I think this last chapter will be the most enjoyable for my readers. It acts as a catharsis for the sorry events in the previous chapters. No more piracy or slavery or trials or fighting or suicide or war or captivity in this one, but true love and lawful marriage!” Because reader satisfaction is the point, Callirhoe is, from a dramatic perspective, well-built. All the conflict within the work arises and recedes from forces within the text. There is no deus ex machina within the novel’s organic and self-sufficient plot.

The mores of the Second Sophistic (c. 60 - 200 CE) leave a significant impact on the nascent genre. During this period, writers turned to the icons of Old, Classical Greece not just for inspiration but style and diction. In Callirhoe Chariton had introduced the story as his own: “I, Chariton of Aphrodisias, secretary for the lawyer Athenagorus, will tell a love story set in Syracuse.” The original narrativists, Herodotus for example, rarely spoke of their own authority, instead leaning on the testimony of others. Writers of the Second Sophistic followed their example: no longer could novelists relate their stories as their own. Achilles Tatius was another novelist, writing well into this period. He diverges significantly from Chariton in the opening to his Leucippe and Clitophon. He relates that while in Sidon, he saw a beautiful painting of a love story, and a young man nearby begins to tell Achilles his own adventures with love. The bulk of the novel is therefore framed in this context and that is to say not directly from the narrator.

The Second Sophistic commandeered the novel, so to speak. The new generation of novelists were learned men who used the popular genre to voice their own interests and thoughts. The novel shifted from a love story for the sake of a love story to a love story for the sake of rhetoric. In this period the novel is a vehicle for showcasing its author’s talents. The text is likely to feature lengthy treatments of philosophical, geographical, etc. knowledge and it is likely to engage in meta-textual dialogue with other novels. In the above example from Achilles Tatius, the text invites comparison with a contemporary Second Sophistic novel, Daphnis and Chloe by Longus. The text claims to be a description of a painting found on the island of Lesbos (the technical term for a lengthy description of art is ekphrasis). In Achilles Tatius’ novel, though, the text begins with an ekphrasis, but it then subverts this expectation; the narrative comes from another onlooker and not the painting itself. This sort of maneuvering is unknown in the early novelists and is the most noticeable change ushered in from the Second Sophistic. Under its auspices, the novel becomes playful, often to the point of parodic, and often at the integrity of the plot’s expense. Unlike Chariton’s well-made plot, later texts hang on the deus ex machina and similar devices. In Achilles Tatius, Clitophon and Leucippe fall in love, but Clitophon is already engaged to his half-sister Calligone and is soon to be wed. The dramatic buildup is dropped suddenly: a young Byzantine has heard of Leucippe’s famous beauty and comes to kidnap her but carries off Calligone by mistake. This plot point is not continued through the rest of the text, except at the end where he and Calligone do end up falling in love. Easy resolutions like this are pervasive in the later novels. Though more artistic and educated, these texts did not challenge the form of the novel to grow; it was an easy skeleton for novelists to line with what they really cared about. These Second Sophistic works deal with the Hellenistic novel form casually and without much respect. The decline and extinction of the Greek novel is partially explained by its limited purview during the Second Sophistic - its arrested development by this sudden literary movement meant that the novel could not grow to meet the challenges of its age.

3 notes

·

View notes