#instead of optical mineralogy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Those are absolutely beautiful!! And the different colors!! 🤩 is the blue caused by crystal defects then? Instead of a specific element?

Ohhhh I know nothing about zircon vs. cubic zirconia except, I assume cubic zirconia is in the cubic system? and zircon is… tetragonal? (if I remember correctly 😂) I’m definitely curious to know more!

Please know I would LOVE to see any microscope pictures!!!

And just for fun, this is the atlas of zircon textures (which I used to categorize my tiny zircons):

Some of the zoning is really pretty, especially in magmatic zircons.

just-thoughts-about-gems (this is the place to ask your gemstone questions)

#I think birefringence helped with differentiation between zircons and apatites?#but I don’t remember anything about DR#not to sound like a bad mineralogist#but i mainly used scanning electron microscopy for this project#instead of optical mineralogy#so i don’t remember much about the optical properties#ohhh I love rutile!! I’ve mainly seen it as an inclusion in quartz though#I have a big chunk that sits on my desk and the rutile sparkles when the sun hits it#also emerald inclusions? 👀#and thermochron is very fun!#i did thermal history modeling#using He profiles (since He is produced when U and Th decay)#and then the distribution of U and Th and He within individual grains#can be used to construct a thermal path#I had to learn A LOT about diffusion#but luckily I didn’t have to write the model 😂#also please know that I am so excited about these topics#anything you want to share I will gobble up#geology rocks#gemology time!

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mineral Swag Round 1: The Poll Maker's Favorites

More information under the cut (this is a long one, I love these minerals!)

Garnet and Peridot. These are literally my two favorite minerals and here I am pitting them against each other in round one. But it must be done. Their vibes are too similar for them to be paired with any other mineral.

Garnet is #1 on my list. She can be red or orange or green. The most well-known of the garnet species is probably pyrope garnet. She’s the one with that classic deep red color associated with garnet! (For more information about mineral species and what they are and why they form, see when I talk about olivine further down).

The picture above the poll is an almandine garnet and it’s probably my favorite garnet sample of ALL TIME. Those garnet crystals formed like that naturally. Someone did NOT go in and cut that up. They removed some of the schist (the rock matrix that the garnet crystals are stuck in) but garnet just looks like that naturally, babey! Garnet naturally forms as a dodecahedron.

I also love that garnet forms during the metamorphosis of rocks! Shale is a dull, mostly boring-to-look-at rock made of mud and clay. When it experiences high enough pressures and temperatures, it is metamorphosed into schist, a delightfully shinny slippery rock that sometimes has big old garnets in it, as shown above! The rock was smooth and boring, then the minerals recrystallized until it became a weirdly chunky rock!

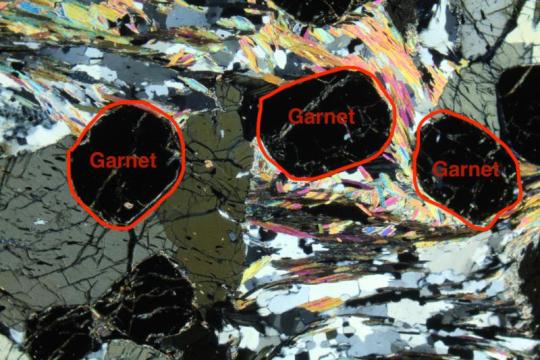

Another fun fact about garnet has to do with petrographic microscopes and optical mineralogy. Geologists can look at rocks on an outcrop (think big rocks and cliff faces on the side of the road) or in their hand. But to see the minute details of specific minerals, we use thin sections of rock. Thin sections are exactly what they sound like! Super super super thin (30 microns, or 0.003 centimeters thick) slices of rock. Geology students can make them! But if you want good quality ones, you usually send them to a company.

Anyway, when rocks are sliced that thin you can shine light through the minerals (using a petrographic microscope). Minerals have properties you can see and test when you’re holding a sample, but they also have optical properties when you shine plane polarized light (PPL) or cross polarized light (XPL) through it that can be used to identify it. One of garnet’s optical properties is that it looks clear in PPL, but completely dark in XPL and I think that’s a super neat trick.

The same sample in PPL (left) and XPL (right). Pictures from here, annotated by me.

Maybe if people are super geeked about petrology and mineralogy, I’ll talk about it more in another post, but this post is already long and I do not remember THAT much about mineralogy to write a concise summary about any of it!

Now for my other favorite mineral, olivine, aka peridot. Peridot and olivine are the same mineral, but peridot is gem-quality olivine.

Olivine is the real forbidden rock candy. Most of the time it forms these little crunchy looking crystals instead of big impressive crystals like garnet. But it’s such a brilliant green color, and the texture is really very fun.

As for its geologic significance, most of the mantle is olivine! The gooey plastic rock that the tectonic plates float on is mostly this cool green rock. Also, olivine is a great example to use when learning about mineral species. Taken from the preliminary polls:

Olivine has two prominent "end members" or mineral species. The chemical formula for olivine is

(SOMETHING)2Si2O6

That (SOMETHING) is almost always magnesium (Mg) or iron (Fe) or some combination of the two. If an olivine sample has ALL magnesium in that spot, it is known as forsterite (one of the olivine "end members"). If it has ALL iron in that spot, it is known as fayalite (the other end member). And, of course, because nature is not perfect, there can be an olivine with any combination of mangesium and iron (between these two end members).

At their core, fayalite and forsterite are both olivine. They are both silicate minerals (see the part of their formula with Si) and regardless of whether they have magnesium or iron, their structure is the same. They have silicate tetrahedrons (the 3D shape that the molecule Si2O6 makes - think a d4 in D&D) bonded with some iron or magnesium atoms.

In this case, whether you vote garnet or olivine, you have chosen a wonderfully amazing mineral.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wednesday, October 2 2024

100 Days of Productivity: 16/100

🌲 School

- Chem study group

- Mineralogy lecture

- Optical mineralogy lecture and lab

- Chemistry lecture

- Worked on chem assignments

- Lab write-up

🌾 Other

- Dishes

- Commuted on bike, ~30 min

- Paperwork stuff

🌿 Notes

Wednesday is always really busy, but my lab wasn't too bad today. I accidently slept in and was almost late. Looking forward to the weather getting cooler, it's still pretty warm for October. Have an exam tomorrow I'm kinda worried about. Took a break and rewatched the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre instead of studying for some reason. Idk I had a good time.

⏰️ Study Time:

Chemistry- 75 min

Mineralogy- 0 min

Optical Mineralogy- 15 min

Trigonometry- 0 min

Research/Seminar- 0 min

0 notes

Text

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov

a Russian polymath, scientist and writer, who made important contributions to literature, education, and science. Among his discoveries were the atmosphere of Venus and the law of conservation of mass in chemical reactions. His spheres of science were natural science, chemistry, physics, mineralogy, history, art, philology, optical devices and others. The founder of modern geology, Lomonosov was also a poet and influenced the formation of the modern Russian literary language.

Catherine II of Russia visits Mikhail Lomonosov in 1764. 1884 painting by Ivan Feodorov.

In 1756, Lomonosov tried to replicate Robert Boyle's experiment of 1673. He concluded that the commonly accepted phlogiston theorywas false. Anticipating the discoveries of Antoine Lavoisier, he wrote in his diary: "Today I made an experiment in hermetic glass vessels in order to determine whether the mass of metals increases from the action of pure heat. The experiments – of which I append the record in 13 pages – demonstrated that the famous Robert Boyle was deluded, for without access of air from outside the mass of the burnt metal remains the same".

That is the Law of Mass Conservation in chemical reaction, which is well-known today as "in a chemical reaction, the mass of reactants is equal to the mass of the products." Lomonosov, together with Lavoisier, is regarded as the one who discovered the law of mass conservation.

He stated that all matter is composed of corpuscles – molecules that are "collections" of elements – atoms. In his dissertation "Elements of Mathematical Chemistry" (1741, unfinished), the scientist gives the following definition: "An element is a part of a body that does not consist of any other smaller and different bodies ... corpuscle is a collection of elements forming one small mass." In a later study (1748), he uses the term "atom" instead of "element", and "particula" (particle) or "molecule" instead of "corpuscle".

He regarded heat as a form of motion, suggested the wave theory of light, contributed to the formulation of the kinetic theory of gases, and stated the idea of conservation of matter in the following words: "All changes in nature are such that inasmuch is taken from one object insomuch is added to another. So, if the amount of matter decreases in one place, it increases elsewhere. This universal law of nature embraces laws of motion as well, for an object moving others by its own force in fact imparts to another object the force it loses" (first articulated in a letter to Leonhard Euler dated 5 July 1748, rephrased and published in Lomonosov's dissertation "Reflexion on the solidity and fluidity of bodies", 1760

Lomonosov was the first to discover and appreciate the atmosphere of Venus during his observation of the transit of Venus of 1761 in a small observatory near his house in St Petersburg.

On the 5th and 6th of June 2012, a group of astronomers carried out an experimental reconstruction of Lomonosov's discovery of the Venusian atmosphere with antique refractors during the transit of Venus. They concluded that Lomonosov's telescope was fully adequate to the task of detecting the arc of light around Venus off the Sun's disc during ingress or egress if proper experimental techniques as described by Lomonosov in his 1761 paper were employed.

In 1762, Lomonosov presented an improved design of a reflecting telescope to the Russian Academy of Sciences forum. His telescope had its primary mirror adjusted at an angle of four degrees to the telescope's axis. This made the image focus at the side of the telescope tube, where the observer could view the image with an eyepiece without blocking the image. However, this invention was not published until 1827, so this type of telescope has become associated with a similar design by William Herschel, the Herschelian telescope.

Chemist and geologist

In 1759, with his collaborator, academician Joseph Adam Braun, Lomonosov was the first person to record the freezing of mercury and to carry out initial experiments with it. Believing that nature is subject to regular and continuous evolution, he demonstrated the organic origin of soil, peat, coal, petroleum and amber. In 1745, he published a catalogue of over 3,000 minerals, and in 1760, he explained the formation of icebergs.

In 1763, he published On The Strata of the Earth– his most significant geological work. This work puts him before James Hutton, who has been traditionally regarded as the founder of modern geology. Lomonosov based his conceptions on the unity of the Earth's processes in time, and necessity to explain the planet's past from present.

Geographer

Lomonosov's observation of iceberg formation led into his pioneering work in geography. Lomonosov got close to the theory of continental drift, theoretically predicted the existence of Antarctica (he argued that icebergs of the South Ocean could be formed only on a dry land covered with ice), and invented sea tools which made writing and calculating directions and distances easier. In 1764, he organized an expedition (led by Admiral Vasili Chichagov) to find the Northeast Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans by sailing along the northern coast of Siberia.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Time Machine. H. G. Wells

CHAPTER X.

The Palace of Green Porcelain.

This Palace of Green Porcelain, when we approached it about noon, was, I found, deserted and falling into ruin. Only ragged vestiges of glass remained in its windows, and great sheets of the green facing had fallen away in places from the corroded metallic framework. It lay very high upon a turfy down, and, looking northeastward before I entered it, I was surprised to see a large estuary, or an arm of the sea, where I judged Wandsworth and Battersea must once have been. I thought then—though I never followed the thought up—of what might have happened, or might be happening, to the living things in the sea.

"The material of the Palace proved, on examination, to be indeed porcelain, and above the face of it I saw an inscription in some unknown characters. I thought, rather foolishly, that Weena might help me to interpret this, but I only learned that the bare idea of writing had never entered her head. She always seemed to me, I fancy, more human than she was, perhaps because her affection was so human.

"Within the big valves of the door—which were open and broken—we found, instead of the customary hall, a long gallery lit by many side windows. Even at the first glance I was reminded of a museum. The tiled floor was thick with dust, and a remarkable array of miscellaneous objects were shrouded in the same gray covering. Clearly, the place had been derelict for a very considerable time.

"Then I perceived, standing strange and guant in the center of the hall, what was clearly the lower part of the skeleton of some huge animal. As I approached this I recognized by the oblique feet that it was some extinct creature after the fashion of the megatherium. The skull and the upper bones lay beside it in the thick dust, and in one place where rain water had dripped through some leak in the roof, the skeleton had decayed away. Further along the gallery was the huge skeleton barrel of a brontosaurus. My museum hypothesis was confirmed. Going toward the side of the gallery I found what appeared to be sloping shelves, and clearing away the thick dust, I found the old familiar glass cases of our own time. But these must have been air-tight to judge from the fair preservation of some of their contents.

"Clearly we stood among the ruins of some latter day South Kensington. Here apparently was the Palæontological Section, and a very splendid array of fossils it must have been; though the inevitable process of decay that had been warded off for a time, and had, through the extinction of bacteria and fungi, lost ninety-nine-hundreths of its force, was nevertheless, with extreme sureness, if with extreme slowness, at work again upon all its treasures. Here and there I found traces of the little people in the shape of rare fossils broken to pieces or threaded in strings upon reeds. And the cases had in some instances been bodily removed—by the Morlocks, as I judged.

"The place was very silent. The thick dust deadened our footsteps. Weena, who had been rolling a sea urchin down the sloping glass of a case, presently came, as I stared about me, and very quietly took my hand and stood beside me.

"At first I was so much surprised by this ancient monument of an intellectual age that I gave no thought to the possibilities it presented me. Even my preoccupation about the Time Machine and the Morlocks receded a little from my mind. The curiosity concerning human destiny that had led to my time traveling was removed. Now, judging from the size of the place, this Palace of Green Porcelain had a great deal more in it than a gallery of palæontology; possibly historical galleries, it might be even a library. To me, at least in my present circumstances, these would be vastly more interesting than this spectacle of old-time geology in decay.

"Exploring, I found another short gallery running transversely to the first. This appeared to be devoted to minerals, and the sight of a block of sulphur set my mind running on gunpowder. But I could find no saltpeter; indeed no nitrates of any kind. Doubtless they had deliquesced ages ago. Yet the sulphur hung in my mind and set up a train of thinking. As for the rest of the contents of that place, though on the whole they were the best preserved of all I saw—I had little interest. I am no specialist in mineralogy, and I soon went on down a very ruinous aisle running parallel to the first hall I had entered.

"Apparently this section had been devoted to Natural History, but here everything had long since passed out of recognition. A few shriveled vestiges of what had once been stuffed animals, dried-up mummies in jars that had once held spirit, a brown dust of departed plants, that was all. I was sorry for this, because I should have been glad to trace the patient readjustments by which the conquest of animated nature had been attained.

"From this we come to a gallery of simply colossal proportions, but singularly ill lit, and with its floor running downward at a slight angle from the end at which I entered it. At intervals there hung white globes from the ceiling,—many of them cracked and smashed,—which suggested that originally the place had been artificially lit. Here I was more in my element, for I found rising on either side of me the huge bulks of big machines, all greatly corroded, and many broken down, but some still fairly complete in all their parts. You know I have a certain weakness for mechanism, and I was inclined to linger among these, the more so since for the most part they had the interest of puzzles, and I could make only the vaguest guesses of what they were for. I fancied if I could solve these puzzles I should find myself in the possession of powers that might be of use against the Morlocks.

"Suddenly Weena came very close to my side, so suddenly that she startled me.

"Had it not been for her I do not think I should have noticed that the floor of the gallery sloped at all.[1] The end I had entered was quite above ground, and was lit by rare slit-like windows. As one went down the length of the place, the ground came up against these windows, until there was at last a pit like the 'area' of a London house, before each, and only a narrow line of daylight at the top. I went slowly along, puzzling about the machines, and had been too intent upon them to notice the gradual diminution of the light, until Weena's increasing apprehension attracted my attention.

"Then I saw that the gallery ran down at last into a thick darkness. I hesitated about proceeding, and then as I looked around me, I saw that the dust was here less abundant and its surface less even. Further away toward the dim, it appeared to be broken by a number of small narrow footprints. At that my sense of the immediate presence of the Morlocks revived. I felt that I was wasting my time in my academic examination of this machinery. I called to mind that it was already far advanced in the afternoon, and that I had still no weapon, no refuge, and no means of making a fire. And then, down in the remote black of the gallery, I heard a peculiar pattering and those same odd noises I had heard down the well.

"I took Weena's hand. Then struck with a sudden idea, I left her, and turned to a machine from which projected a lever not unlike those in a signal box. Clambering upon the stand of the machine and grasping this lever in my hands, I put all my weight upon it sideways. Weena, deserted in the central aisle, began suddenly to whimper. I had judged the strength of the lever pretty correctly, for it snapped after a minute's strain, and I rejoined Weena with a mace in my hand more than sufficient, I judged, for any Morlock skull I might encounter.

"And I longed very much to kill a Morlock or so. Very inhuman, you may think, to want to go killing one's own descendants, but it was impossible somehow to feel any humanity in the things. Only my disinclination to leave Weena, and a persuasion that if I began to slake my thirst for murder my Time Machine might suffer, restrained me from going straight down the gallery and killing the brutes I heard there.

"Mace in one hand and Weena in the other we went out of that gallery and into another still larger, which at the first glance reminded me of a military chapel hung with tattered flags. The brown and charred rags that hung from the sides of it, I presently recognized as the decaying vestiges of books. They had long since dropped to pieces and every semblance of print had left them. But here and there were warped and cracked boards and metallic clasps that told the tale well enough.

"Had I been a literary man I might perhaps have moralized upon the futility of all ambition, but as it was, the thought that struck me with keenest force, was the enormous waste of labor rather than of hope, to which this somber gallery of rotting paper testified. At the time I will confess, though it seems a petty trait now, that I thought chiefly of the Philosophical Transactions, and my own seventeen papers upon physical optics.

"Then going up a broad staircase we came to what may once have been a gallery of technical chemistry. And here I had not a little hope of discovering something to help me. Except at one end where the roof had collapsed, this gallery was well preserved. I went eagerly to every unbroken case. And at last, in one of the really air-tight cases, I found a box of matches. Very eagerly I tried them. They were perfectly good. They were not even damp.

"At that discovery I suddenly turned to Weena. ’Dance!' I cried to her in her own tongue. For now I had a weapon indeed against the horrible creatures we feared. And so in that derelict museum, upon the thick soft coating of dust, to Weena's huge delight, I solemnly performed a sort of composite dance, whistling 'The Land of the Leal' as cheerfully as I could. In part it was a modest cancan, in part a step dance, in part a skirt dance,—so far as my tail coat permitted,—and in part original. For naturally I am inventive, as you know.

"Now, I still think that for this box of matches to have escaped the wear of time for immemorial years was a strange, and for me, a most fortunate thing. Yet oddly enough I found here a far more unlikely substance, and that was camphor. I found it in a sealed jar, that, by chance, I supposed had been really hermetically sealed. I fancied at first the stuff was paraffin wax, and smashed the jar accordingly. But the odor of camphor was unmistakable. It struck me as singularly odd, that among the universal decay, this volatile substance had chanced to survive, perhaps through many thousand years. Is reminded me of a sepia painting I had once seen done from the ink of a fossil Belemnite that must have perished and become fossilized millions of years ago. I was about to throw this camphor on one side, and then remembering that it was inflammable and burnt with a good bright flame, I put it into my pocket.

"I found no explosives, however, or any means of breaking down the bronze doors. As yet my iron crowbar was the most hopeful thing I had chanced upon. Nevertheless I left that gallery greatly elated by my discoveries.

"I cannot tell you the whole story of my exploration through that long afternoon. It would require a great effort of memory to recall it at all in the proper order, I remember a long gallery containing the rusting stands of arms of all ages, and that I hesitated between my crowbar and a hatchet or a sword. I could not carry both, however, and my bar of iron, after all, promised best against the bronze gates. There were rusty guns, pistols, and rifles here; most of them were masses of rust, but many of aluminum, and still fairly sound. But any cartridges or powder there may have been had rotted into dust. One corner I saw was charred and shattered; perhaps, I thought, by an explosion among the specimens there. In another place was a vast array of idols—Polynesian, Mexican, Grecian, Phoenician, every country on earth, I should think. And here, yielding to an irresistible impulse, I wrote my name upon the nose of a steatite monster from South America that particularly took my fancy.

"As the evening drew on my interest waned. I went through gallery after gallery, dusty, silent, often ruinous, the exhibits sometimes mere heaps of rust and lignite, sometimes fresher. In one place I suddenly found myself near a model of a tin mine, and then by the merest accident I discovered in an air-tight case two dynamite cartridges; I shouted 'Eureka!' and smashed the case joyfully. Then came a doubt. I hesitated, and then selecting a little side gallery I made my essay. I never felt such a bitter disappointment as I did then, waiting five, ten, fifteen minutes for the explosion that never came. Of course the things were dummies, as I might have guessed from their presence there. I really believe had they not been so, I should have rushed off incontinently there and then, and blown sphinx, bronze doors, and, as it proved, my chances of finding the Time Machine all together into non-existence.

"It was after that, I think, that we came to a little open court within the palace, turfed and with three fruit trees. There it was we rested and refreshed ourselves.

"Toward sunset I began to consider our position. Night was now creeping upon us and my inaccessible hiding-place was still to be found. But that troubled me very little now. I had in my possession a thing that was perhaps the best of all defenses against the Morlocks. I had matches again. I also had the camphor in my pocket if a blaze were required. It seemed to me that the best thing we could do would be to pass the night in the open again, protected by a fire.

"In the morning there was the Time Machine to obtain. Toward that as yet I had only my iron mace. But now with my growing knowledge I felt very differently toward the bronze doors than I had done hitherto. Up to this I had refrained from forcing them, largely because of the mystery on the other side. They had never impressed me as being very strong, and I hoped to find my bar of iron not altogether inadequate for the work.

0 notes

Text

`I found the Palace of Green Porcelain, when we approached it about noon, deserted and falling into ruin. Only ragged vestiges of glass remained in its windows, and great sheets of the green facing had fallen away from the corroded metallic framework. It lay very high upon a turfy down, and looking north-eastward before I entered it, I was surprised to see a large estuary, or even creek, where I judged Wandsworth and Battersea must once have been. I thought then--though I never followed up the thought--of what might have happened, or might be happening, to the living things in the sea.

`The material of the Palace proved on examination to be indeed porcelain, and along the face of it I saw an inscription in some unknown character. I thought, rather foolishly, that Weena might help me to interpret this, but I only learned that the bare idea of writing had never entered her head. She always seemed to me, I fancy, more human than she was, perhaps because her affection was so human.

`Within the big valves of the door--which were open and broken--we found, instead of the customary hall, a long gallery lit by many side windows. At the first glance I was reminded of a museum. The tiled floor was thick with dust, and a remarkable array of miscellaneous objects was shrouded in the same grey covering. Then I perceived, standing strange and gaunt in the centre of the hall, what was clearly the lower part of a huge skeleton. I recognized by the oblique feet that it was some extinct creature after the fashion of the Megatherium. The skull and the upper bones lay beside it in the thick dust, and in one place, where rain-water had dropped through a leak in the roof, the thing itself had been worn away. Further in the gallery was the huge skeleton barrel of a Brontosaurus. My museum hypothesis was confirmed. Going towards the side I found what appeared to be sloping shelves, and clearing away the thick dust, I found the old familiar glass cases of our own time. But they must have been air-tight to judge from the fair preservation of some of their contents.

`Clearly we stood among the ruins of some latter-day South Kensington! Here, apparently, was the Palaeontological Section, and a very splendid array of fossils it must have been, though the inevitable process of decay that had been staved off for a time, and had, through the extinction of bacteria and fungi, lost ninety-nine hundredths of its force, was nevertheless, with extreme sureness if with extreme slowness at work again upon all its treasures. Here and there I found traces of the little people in the shape of rare fossils broken to pieces or threaded in strings upon reeds. And the cases had in some instances been bodily removed--by the Morlocks as I judged. The place was very silent. The thick dust deadened our footsteps. Weena, who had been rolling a sea urchin down the sloping glass of a case, presently came, as I stared about me, and very quietly took my hand and stood beside me.

`And at first I was so much surprised by this ancient monument of an intellectual age, that I gave no thought to the possibilities it presented. Even my preoccupation about the Time Machine receded a little from my mind.

`To judge from the size of the place, this Palace of Green Porcelain had a great deal more in it than a Gallery of Palaeontology; possibly historical galleries; it might be, even a library! To me, at least in my present circumstances, these would be vastly more interesting than this spectacle of oldtime geology in decay. Exploring, I found another short gallery running transversely to the first. This appeared to be devoted to minerals, and the sight of a block of sulphur set my mind running on gunpowder. But I could find no saltpeter; indeed, no nitrates of any kind. Doubtless they had deliquesced ages ago. Yet the sulphur hung in my mind, and set up a train of thinking. As for the rest of the contents of that gallery, though on the whole they were the best preserved of all I saw, I had little interest. I am no specialist in mineralogy, and I went on down a very ruinous aisle running parallel to the first hall I had entered. Apparently this section had been devoted to natural history, but everything had long since passed out of recognition. A few shrivelled and blackened vestiges of what had once been stuffed animals, desiccated mummies in jars that had once held spirit, a brown dust of departed plants: that was all! I was sorry for that, because I should have been glad to trace the patent readjustments by which the conquest of animated nature had been attained. Then we came to a gallery of simply colossal proportions, but singularly ill-lit, the floor of it running downward at a slight angle from the end at which I entered. At intervals white globes hung from the ceiling--many of them cracked and smashed--which suggested that originally the place had been artificially lit. Here I was more in my element, for rising on either side of me were the huge bulks of big machines, all greatly corroded and many broken down, but some still fairly complete. You know I have a certain weakness for mechanism, and I was inclined to linger among these; the more so as for the most part they had the interest of puzzles, and I could make only the vaguest guesses at what they were for. I fancied that if I could solve their puzzles I should find myself in possession of powers that might be of use against the Morlocks.

`Suddenly Weena came very close to my side. So suddenly that she startled me. Had it not been for her I do not think I should have noticed that the floor of the gallery sloped at all. [Footnote: It may be, of course, that the floor did not slope, but that the museum was built into the side of a hill.-ED.] The end I had come in at was quite above ground, and was lit by rare slit-like windows. As you went down the length, the ground came up against these windows, until at last there was a pit like the "area" of a London house before each, and only a narrow line of daylight at the top. I went slowly along, puzzling about the machines, and had been too intent upon them to notice the gradual diminution of the light, until Weena's increasing apprehensions drew my attention. Then I saw that the gallery ran down at last into a thick darkness. I hesitated, and then, as I looked round me, I saw that the dust was less abundant and its surface less even. Further away towards the dimness, it appeared to be broken by a number of small narrow footprints. My sense of the immediate presence of the Morlocks revived at that. I felt that I was wasting my time in the academic examination of machinery. I called to mind that it was already far advanced in the afternoon, and that I had still no weapon, no refuge, and no means of making a fire. And then down in the remote blackness of the gallery I heard a peculiar pattering, and the same odd noises I had heard down the well.

`I took Weena's hand. Then, struck with a sudden idea, I left her and turned to a machine from which projected a lever not unlike those in a signal-box. Clambering upon the stand, and grasping this lever in my hands, I put all my weight upon it sideways. Suddenly Weena, deserted in the central aisle, began to whimper. I had judged the strength of the lever pretty correctly, for it snapped after a minute's strain, and I rejoined her with a mace in my hand more than sufficient, I judged, for any Morlock skull I might encounter. And I longed very much to kill a Morlock or so. Very inhuman, you may think, to want to go killing one's own descendants! But it was impossible, somehow, to feel any humanity in the things. Only my disinclination to leave Weena, and a persuasion that if I began to slake my thirst for murder my Time Machine might suffer, restrained me from going straight down the gallery and killing the brutes I heard.

`Well, mace in one hand and Weena in the other, I went out of that gallery and into another and still larger one, which at the first glance reminded me of a military chapel hung with tattered flags. The brown and charred rags that hung from the sides of it, I presently recognized as the decaying vestiges of books. They had long since dropped to pieces, and every semblance of print had left them. But here and there were warped boards and cracked metallic clasps that told the tale well enough. Had I been a literary man I might, perhaps, have moralized upon the futility of all ambition. But as it was, the thing that struck me with keenest force was the enormous waste of labour to which this sombre wilderness of rotting paper testified. At the time I will confess that I thought chiefly of the PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS and my own seventeen papers upon physical optics.

`Then, going up a broad staircase, we came to what may once have been a gallery of technical chemistry. And here I had not a little hope of useful discoveries. Except at one end where the roof had collapsed, this gallery was well preserved. I went eagerly to every unbroken case. And at last, in one of the really air-tight cases, I found a box of matches. Very eagerly I tried them. They were perfectly good. They were not even damp. I turned to Weena. "Dance," I cried to her in her own tongue. For now I had a weapon indeed against the horrible creatures we feared. And so, in that derelict museum, upon the thick soft carpeting of dust, to Weena's huge delight, I solemnly performed a kind of composite dance, whistling THE LAND OF THE LEAL as cheerfully as I could. In part it was a modest CANCAN, in part a step dance, in part a skirt-dance (so far as my tail-coat permitted), and in part original. For I am naturally inventive, as you know.

`Now, I still think that for this box of matches to have escaped the wear of time for immemorial years was a most strange, as for me it was a most fortunate thing. Yet, oddly enough, I found a far unlikelier substance, and that was camphor. I found it in a sealed jar, that by chance, I suppose, had been really hermetically sealed. I fancied at first that it was paraffin wax, and smashed the glass accordingly. But the odour of camphor was unmistakable. In the universal decay this volatile substance had chanced to survive, perhaps through many thousands of centuries. It reminded me of a sepia painting I had once seen done from the ink of a fossil Belemnite that must have perished and become fossilized millions of years ago. I was about to throw it away, but I remembered that it was inflammable and burned with a good bright flame--was, in fact, an excellent candle--and I put it in my pocket. I found no explosives, however, nor any means of breaking down the bronze doors. As yet my iron crowbar was the most helpful thing I had chanced upon. Nevertheless I left that gallery greatly elated.

`I cannot tell you all the story of that long afternoon. It would require a great effort of memory to recall my explorations in at all the proper order. I remember a long gallery of rusting stands of arms, and how I hesitated between my crowbar and a hatchet or a sword. I could not carry both, however, and my bar of iron promised best against the bronze gates. There were numbers of guns, pistols, and rifles. The most were masses of rust, but many were of some new metal, and still fairly sound. But any cartridges or powder there may once have been had rotted into dust. One corner I saw was charred and shattered; perhaps, I thought, by an explosion among the specimens. In another place was a vast array of idols--Polynesian, Mexican, Grecian, Phoenician, every country on earth I should think. And here, yielding to an irresistible impulse, I wrote my name upon the nose of a steatite monster from South America that particularly took my fancy.

`As the evening drew on, my interest waned. I went through gallery after gallery, dusty, silent, often ruinous, the exhibits sometimes mere heaps of rust and lignite, sometimes fresher. In one place I suddenly found myself near the model of a tin-mine, and then by the merest accident I discovered, in an air-tight case, two dynamite cartridges! I shouted "Eureka!" and smashed the case with joy. Then came a doubt. I hesitated. Then, selecting a little side gallery, I made my essay. I never felt such a disappointment as I did in waiting five, ten, fifteen minutes for an explosion that never came. Of course the things were dummies, as I might have guessed from their presence. I really believe that had they not been so, I should have rushed off incontinently and blown Sphinx, bronze doors, and (as it proved) my chances of finding the Time Machine, all together into nonexistence.

`It was after that, I think, that we came to a little open court within the palace. It was turfed, and had three fruit- trees. So we rested and refreshed ourselves. Towards sunset I began to consider our position. Night was creeping upon us, and my inaccessible hiding-place had still to be found. But that troubled me very little now. I had in my possession a thing that was, perhaps, the best of all defences against the Morlocks--I had matches! I had the camphor in my pocket, too, if a blaze were needed. It seemed to me that the best thing we could do would be to pass the night in the open, protected by a fire. In the morning there was the getting of the Time Machine. Towards that, as yet, I had only my iron mace. But now, with my growing knowledge, I felt very differently towards those bronze doors. Up to this, I had refrained from forcing them, largely because of the mystery on the other side. They had never impressed me as being very strong, and I hoped to find my bar of iron not altogether inadequate for the work.

0 notes

Text

Mineral Swag Round 1: These are the Same Mineral

More information under the cut!

Quartz and Amethyst!

I feel like there isn’t a lot to say here because these are probably some of the best known minerals. Though, maybe I am overestimating peoples’ familiarity with geology! Roll the comic.

Quartz is a mineral made up mostly of silicon. It’s the second most abundant mineral in earth’s continental crust (so, not the stuff at the bottom of the ocean). It often forms six-sided crystals but don’t be fooled thinking this crystal shape is the same as cleavage! Quartz does not cleave along specific planes and instead fractures like glass, creating a conchoidal pattern:

Obsidian (which is just volcanic glass) also shows conchoidal fracture - flint knapping takes advantage of conchoidal fracture to form weapons (like obsidian knives).

Another variety of quartz I want to share is Herkimer quartz or Herkimer diamonds. These are especially clear quartz crystals that are pointed on either end (double terminated) instead of being a long six-sided crystal ending at one point and therefore look a bit like diamonds. These quartz crystals are found in Herkimer, New York.

And, from one submitter: idk if this count as rock or mineral in geology world but in my science world (optics) we use the word interchangably with silicon dioxide/silica. and the higher the purity, the better the optical glass it is. very hard. in the high purity form, can transmit UV light very well (down to 185 nm or so) whereas most borosilicate glasses can only maybe get you to 270 nm

NEAT!

Amethyst is the SAME MINERAL as quartz! Exact same, but a little less perfect which is why it’s purple. I love how in mineralogy, the imperfections at the atomic scale are what make such pretty colors. Amethyst can range from really dark purple to pale lavender and sometimes, it can change how dark the color is from the bottom to the top of the same crystal. Sometimes, as a mineral is growing, the chemical composition of whatever material it is growing in (water with things dissolved in it, a magma, etc) changes slightly and causes changes in color. See the fluorite poll for some really cool examples of this!

Other than that, amethyst is purple. What more could you want?

46 notes

·

View notes