#in some way to hachi (who is specifically called hachi in this dream) the person takes me into the theater and calls for him. because hes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

dream log: movie theater. and hachi was there.

#leologisms#sprinting to record this down before i forget it forever.#in the desert or some otherwise hot sandy place. arrive at a theater. everyone goes in. i stumble back outside for water because i know#theres a dispenser outside. i am delirious with thirst and getting more and more delirious. a person outside at the dispenser tells me that#theres no water there (because they have to run the air con too high? i dont remember.) in my delirium i accidentally imply that im related#in some way to hachi (who is specifically called hachi in this dream) the person takes me into the theater and calls for him. because hes#there. in the theater. hes sitting near the back and he waves. i realise my mistake and walk up to sit close to but not next to him (hes#with a group and near to the group i was originally with.) the movie starts. its an animated something or other. i think hachi was there#because he was in the movie somehow? i woke up before finding out what happened next

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (48): (1587) Eighth Month, Twenty-fifth Day, Midday.

48) Eighth Month, Twenty-fifth Day; Midday¹.

It had been promised that [Imai] Sōkyu --

﹆ [would] bring the tea².

◦ 4.5-mat [room]³.

◦ [Guests:] Sōkyū [宗久]⁴, Yakushi-in [藥師院]⁵, Fujishige [藤重]⁶, Rōju [良壽]⁷, Sōmoto [宗本]⁸.

Sho [初]⁹.

﹆ Engo [圓悟]¹⁰: in accordance with [the guests’] request to bring [this kakemono] out [for their appreciation]¹¹.

The gedai [外題] was displayed in the toko¹².

◦ On a ko-ita [小板], the furo ・ unryū-gama [風爐 ・ 雲龍釜]¹³.

▵ Shiru saku-saku [汁 サク〰]¹⁴.

▵ Roast shigi [鴫] ・ kamaboko [カマホコ]¹⁵.

▵ Asa-zuke [アサツケ]¹⁶.

▵ Senbei ・ yaki-guri [センヘイ ・ ヤキクリ]¹⁷.

Go [後]¹⁸.

◦ The toko remained as it was¹⁹.

◦ Mizusashi Shigaraki [水指 シカラキ], on top of which was placed the hishaku [ヒシヤク]²⁰.

﹆ Sa-tsū-bako [茶通箱]²¹.

However, inside [the sa-tsū-bako] were the Shiri-bukura [尻フクラ] ・ ko-natsume [小ナツメ]²².

◦ Habōki [羽帚]²³.

Su [ス]²⁴.

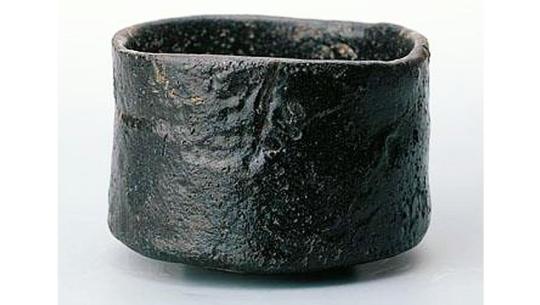

◦ Chawan kuro [茶碗 黒], ori-tame [折撓]²⁵.

_________________________

¹Hachi-gatsu nijū-go-nichi, hiru [八月廿五日、晝].

The Gregorian date was September 27, 1587, since the Eighth Month of Tenshō 15 had only 29 days.

This seems to have been another chakai given for influential machi-shū tea practitioners, probably intended to promote interest in Hideyoshi’s upcoming Kitano ō-cha-no-e [北野大茶の會]. It appears that the guests asked to inspect the Engo bokuseki -- perhaps as a sort of compensation for their taking part in the gathering.

There are several issues with the Enkaku-ji version of this entry that are contradicted by (all of) the other manuscripts (including Jitsuzan’s original copy, which was made with the Shū-un-an document in front of him), suggesting that Jitsuzan either mistook his earlier notes, or deliberately decided to change things for reasons of his own; and (in contradiction to Rikyū’s own writings on the subject) the premise on which the use of the sa-tsū-bako is based clearly derives from machi-shū practices that became mainstream, as a result of Sōtan’s influence*, during the Edo period -- rather than the way that Rikyū appears to have handled this kind of temae. These problems might be considered so significant that it is possible to doubt whether this was an actual chakai hosted by Rikyū -- or whether the entry is completely (or at least partially) spurious. ___________ *Ultimately, these were machi-shū practices that appear to trace their origins back to Jōō’s middle period (when the form of the cha-kai [茶會] was being codified -- based on, though increasingly distinct from, the Shino family’s kō-kai [香會]). Though later superceded by subsequent developments -- which were largely associated with Rikyū (and his influence on Jōō during the last year of the latter’s life) and his circle. A movement to return to the earlier forms appeared shortly after Rikyū’s seppuku, as part of a semi-official effort to repudiate Rikyū’s influence on chanoyu -- championed (with encouragement from at least some of the important daimyō surrounding Hideyoshi such as Date Masamune) by the group of machi-shū practitioners associated with Imai Sōkyū: It was under the influence of this group that Sōtan trained (he was some 14 years of age when Rikyū died); and it was their teachings that he disseminated when he ultimately rose to his position of influence on account of his fictive relationship to Rikyū -- a relationship that was especially important to the Tokugawa bakufu (since it furthered their efforts to turn Hideyoshi’s collection of famous tea utensils into cash).

²Yaku-soku ni te Sōkyū [h]e ﹆cha jisan [約束ニて宗久ヘ ﹆茶持參].

This words cha jisan [茶持參] are marked with a red spot in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, indicating the importance of Sōkyū’s agreeing to provide the tea. However, none of the other versions of this kaiki* are formatted in this way (suggesting that the emphasis -- provided by the red spot -- was added by Jitsuzan, rather than Rikyū).

In all of the other versions of this kaiki, this line reads yakusoku ni te Sōkyū cha jisan [約束ニて宗久茶持參] -- without the particle [h]e [ヘ]†, or the emphasis on the words cha jisan [茶持參]. __________ *Including Jitsuzan's original copy, which he made with the Shū-un-an documents in front of him.

†The particle [h]e [へ] confuses the sense of the statement -- making possible the interpretation that Rikyū was taking the gift tea to Sōkyū.

³Yojō-han [四疊半].

The 4.5-mat room in Rikyū's residence.

⁴Sōkyū [宗久].

This was Imai Sōkyū [今井宗久; 1520 ~ 1593], who was said to be “the other one” of Jōō’s two greatest disciples*.

Sōkyū was married to Jōō’s daughter, and assumed the guardianship of Jōō’s son Sōga [宗瓦; 1550-1614] (who was just six years of age at the time of his father’s death).

At the time of this chakai, the relations between Sōkyū and Rikyū were still more or less cordial, with their main source of contention restricted to their rivalry for Hideyoshi's favor†. ___________ *The other was, or course, Rikyū.

†The primary cause of the bad blood between Rikyū and Sōkyū seems to have arisen because Rikyū disagreed with Sōkyū over how he was managing Sōga’s (Jōō’s son) affairs.

Sōkyū seems to have taken charge of Jōō’s extensive collection of meibutsu utensils shortly after Jōō’s death, which he said was intended both to safeguard them (as Sōga’s inheritance), as well as (in certain cases) reimburse himself for the added expenses placed on his household by the boy’s upbringing. Rikyū, meanwhile, believed (and made it publicly known) that, in his opinion, Sōkyū was simply enriching himself -- both monetarily and with respect to his reputation as a tea master -- at the boy’s expense. (It must be remembered, with respect to meibutsu utensils, that ownership implied that the owner also had been initiated into the secrets of their use -- and, indeed, it was just this fact on which not only Jōō’s own reputation, but eventually that of Sōkyū as well, had been based.)

Rikyū’s own densho addressed to Sōga, meanwhile, suggests that, in his opinion at least, Sōkyū was not doing a very good job at educating the young man in the details of chanoyu that had been finalized by Jōō at the end of his life: rather, it seems that he was schooling him in Sōkyū’s own version of these teachings (which seems to have remained faithful to the style of chanoyu popularized by Jōō during his middle period -- before Rikyū returned from his sojourn in Korea) . Sōkyū’s way of practicing chanoyu (as the leader of the machi-shū faction that was increasingly opposed to Rikyū’s simplifications) can be identified with what is now called the machi-shū style of tea -- which passed into the modern world through Sōtan and his descendants. The difference between Sōkyū’s “machi-shū style” and Rikyū’s chanoyu can be seen clearly by comparing Rikyū’s densho with the practices advocated by the modern Senke schools.

After Rikyū’s death, Sōkyū was one of the leaders of the group that sought to eradicate all traces of Rikyū’s teachings from the practice of chanoyu -- and, given the subsequent and lingering animosity between the Sen families and Rikyū’s own writings, it might be said that Sōkyū was more successful in leaving his imprint on chanoyu than Rikyū, or than he (Sōkyū) could ever have dreamed possible.

⁵Yakushi-in [藥師院].

This was Rikyū's nickname for the man more usually known as Yakuin Zen-sō [施藥院全宗; 1525 ~ 1599]*. Formerly a monk from Ei-san [叡山]†, he was also a respected medical doctor of the period, and a close personal attendant of Hideyoshi's‡. __________ *He was also a chajin and had been a disciple of Jōō.

†This mountain is now usually called Hiei-san [比叡山]. It is one of the peaks in the mountain range between Kyōto and Ōtsu (to the east).

‡Perhaps occupying a position similar to a personal physician.

Hideyoshi was suffering from tertiary syphilis (which evolved into neurosyphilis in the second half of the 1580s) during the last years of his life (which accounts for his increasingly erratic behavior during this final decade), and so the near-constant attendance of a physician (who could at least offer a degree of palliative care) would have been important to him and those around him.

It is inferred that his increasing susceptibility to his delusions of grandeur – specifically that he could succeed in conquering China and having himself installed as Emperor (as suggested by the Korean expatriates in Hakata – whose actual goal seems to have been causing political instability on the Korean peninsula, thus potentially could have allowed for a restoration of the Han [韓] republic that was overthrown by the Ming military incursions aimed at reinstating the feudal system on the Korean peninsula, under the Lee family (as a Chinese puppet-regime), in the middle of the previous century) – increased in step with his developing neurosyphilis.

⁶Fujishige [藤重].

This was Fujishige Tōgen [藤重藤元; his dates of birth and death are not known], a famous lacquer artist from Nara. He was considered the greatest master of that period, and his list of patrons is said to have included both Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu.

⁷Rōju [良壽].

This seems to refer to the machi-shū of Sakai known as Akane-ya Rōju [茜屋良壽; his dates are unknown]. His name is also given as Akane-ya Dōju [茜屋道壽] (which would make him a fellow disciple of Araki Dōchin, together with the young Rikyū; perhaps these two were of a similar age).

His name appears as a guest several times in Rikyū's kaiki, but the details of his practice are not known.

⁸Sōmoto [宗本]⁸.

This was the man known as Noto-ya Sōmoto [能登屋宗本; his dates are not known], another machi-shū of Sakai, and apparently a chajin as well.

No further details have been discovered relating to his life and career.

⁹Sho [初].

The shoza.

With respect to the kane-wari:

- the tokonoma contained the kakemono, displayed rolled up on the floor of the toko, so that the guests could inspect the gedai [外題]*, and so was han [半]†;

- the room, meanwhile, contained the ko-ita furo, and so was han [半] as well;

- there was no tana.

Han + han is chō, which is proper for the shoza of a gathering held during the daytime. __________ *The gedai [外題] is a sort of title (actually, it generally contains the name of the artist responsible for the composition that is featured on the scroll), written on a small piece of paper that is glued to the back of the scroll near the upper roller. Thus, it was originally intended to allow someone to know what the scroll contained without going to the trouble of opening it up. Some of the earliest gedai were written by several of the great Higashiyama dōbō [東山同朋]; and, since they are verified by the writer’s seal, the gedai became an object of appreciation in its own right (this was especially important when many of the old paintings, which were often fragments of larger works salvaged from deteriorating specimens, lack their artist’s signature -- hence the gedai alone provides the viewer with the ascription, which was based on the dōbō’s expertise).

†Tanaka Senshō, unfortunately, confuses things by suggesting that perhaps the toko was empty when the guests entered the room, with Rikyū only bringing the scroll out from the katte after the guests had entered (they would therefore have had to all move to the tokonoma to view the gedai once the scroll was placed there). This, however, would confound the kane-wari -- as well as contradict Rikyū's own words (gedai wo kazaru [外題ヲカサル] -- that “the gedai was displayed [in the toko]”).

¹⁰Engo [圓悟].

This is the bokuseki now usually known as the Nagare Engo [流れ圜悟], formerly owned by Shukō (this, it is said, is the scroll that tradition holds was given to him by Ikkyū Sōjun, and before which he was encouraged to perform chanoyu), which he hung in his room when serving tea. Furthermore, this is said to have been the first bokuseki ever used for chanoyu*.

The scroll was written by the Chinese Chán monk Yuán-wù Kèqín [圜悟克勤; 1063 ~ 1135], the editor of the Bìyán Lù [碧 巖 錄] (Heki-gan Roku; the Blue-cliff Records).

This document was not intended (by Yuán-wù Kèqín) to be used as something like a scroll. It is actually a fragmentary part of Yuán-wù’s notes from one of his lectures (he traveled around China presenting lectures on the cases in the Bìyán Lù at various temples, and this is a fragment of the text of one of these lectures -- probably preserved originally by one of the auditors, as a sort of souvenir of the experience).

Precisely how this document made its way to Japan is unclear, though it seems most likely that Ikkyū Sōjun brought it with him when he immigrated from Korea at the beginning of the persecution of Buddhism (as both a monk, and the posthumous son of the last king of Koryeo, Ikkyū had double reason to fear for his life during this time of great trouble for the faith) on the Korean peninsula. ___________ *Before this, only paintings (almost always imported from the continent) were displayed in the tokonoma. The original intention was to recreate a scene of Amida’s Western Paradise.

¹¹Shomō-yue jisan [所望故持參].

This means that the reason (yue [故]) the scroll was brought out (jisan [持參]) on this occasion was because of a request (shomō [所望]) made by the guests. The request likely was tendered before, or at, the time when the guests accepted the invitation.

¹²Gedai wo kazaru [外題ヲカサル].

The gedai [外題], which is usually translated to mean “title,” refers to something written on the back side of the scroll, near the upper roller, that identifies the scroll’s contents. While the gedai is sometimes written directly on the mounting itself (as in the example shown below), since the Higashiyama period it has also been the custom to write this information on a small slip of paper*, which is then glued onto the back of the scroll.

Now, while there were various accepted times at which the gedai might be displayed†, on this occasion it seems that Rikyū displayed the rolled-up scroll on the floor of the tokonoma (oriented so that the gedai would be easy to read)‡; and after their silence indicated that the guests were finished, he entered and proceeded to hang the kakemono in the toko, so that the guests could then inspect Yuán-wù’s writing. ___________ *Writing the gedai on a separate piece of paper (that was then glued to the back of the scroll) allowed the ascription to be lodged without physically damaging or altering the scroll itself (the glue, which was made from sticky-rice, was water soluble, and could be removed without difficulty). This was the dōbō‘s intention (since the gedai itself was originally considered to be a sort of inventory or cataloging aid).

According to the commentary on the Chanoyu San-byakka Jō [茶湯三百箇條] (this work is usually ascribed to Jōō, though Jōō himself held that the core entries were set down by Shukō: the earliest surviving manuscript was created by Jōō’s disciple Uesugi Kenshin about ten years after Jōō’s death; and includes not only Kenshin’s extrapolations, but also additional interlineal material added by Sen no Dōan and Dōan’s disciple Kuwayama Sōzen -- the different layers of commentary are not separated, or even separable, from each other), the proportions of the slip of paper on which the gedai is written should be calculated in the following way: “if the [honshi [本紙] -- the paper on which the scroll was written -- of the] bokuseki is 1-shaku 1-sun from top to bottom or less, this length should be divided into thirds, and the length of the gedai should be equal to one of the thirds. The width of the gedai should be equal to a sixth-part of its length. This is a secret matter.

“If the scroll is long and wide, or if it is extremely narrow for its length, in general the proportions of the gedai are determined in the same way as above; however, the details are secret: “1) When [the honshi] exceeds 1-shaku 1-sun when measured top-to-bottom, that length is divided by four, and one of the fourths is discarded; then the remaining three are divided as above to give the length and width of the gedai. “2) In the case of extremely long and narrow scrolls, the rule is that the length of the honshi was divided into four parts, and one of these quarters is discarded. The remainder was divided into quarters again, and a further fourth was deleted. From the length of the remaining three, the above rules were followed to determine the length and width of the gedai.”

The above secret material was based on Nōami’s [能阿弥] and Sōami’s [相阿弥] gedai. Since, as mentioned above, these were often pasted onto the backs of scrolls which lacked any sort of artist’s signature at all (either works that were in a poor state of preservation, or panels of a long horizontal scroll that had been cut into individual pieces based on content), it became essential to be able to verify that the gedai actually belonged to the scroll to which it was attached (forgeries of paintings were not uncommon; and one of the easiest ways to pass off a fake was by attaching an authentic gedai -- removed from some other scroll -- to it). Thus, these details provided the assessor with a very good way of determining whether the gedai actually belonged to the scroll to which it was attached, or not. Further details can be found in the post entitled The Three Hundred Lines of Chanoyu (Lines 261 - 270: Part 1, Lines 261 - 265). The quote comes from footnote 5 under line 263 (“The way to inspect a bokuseki’s gedai”).

The URL for that post is:

chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/62296322423/the-three-hundred-lines-of-chanoyu-lines-261

†Sometimes the gedai was displayed first, and after inspecting it, the scroll was hung up so that the guests could view that as well; and sometimes the scroll was already hanging in the toko when he guests entered the tearoom, and the inspection of the gedai took place later in the za (such as immediately before they left the room for the naka-dachi). The latter form was mostly used when the guests subsequently asked to inspect the gedai, while the former was used when the request was tendered before the host began his preparations (as was the case on this occasion).

‡It is not clear who the gedai on this scroll was written by -- though Ikkyū Sōjun or Shukō would seem to be likely candidates. This scroll was never a part of the Higashiyama collection, hence none of the dōbō would have been involved. The hyōgu [表具] (mounting) seems to have been designed by Shukō.

¹³Ko-ita ni furo ・ unryū-gama [小板ニ風爐 ・ 雲龍釜].

For this special occasion, it seems that Rikyū borrowed the old Temmyō kimen-buro that had belonged to Yoshimasa (and, later, Nobunaga).

The kama would have been the first small unryū-gama, which Rikyū designed to be used with this furo.

I assumed (when creating my sketch showing the general arrangement of the room under footnote 3) that Rikyū placed the ko-ita furo on the right side of the utensil mat, since this was the orthodox way of doing things in a room that had a dōko. Nevertheless, in light of the shōkyaku’s relationship to Jōō, and in deference to his feelings*, it is possible that Rikyū decided to place it on the left, in the manner used by Jōō during the middle period of his career†. ___________ *Sōkyū was Jōō’s brother-in-law, and a known champion of the teachings emanating from Jōō’s middle period (meaning the period prior to Rikyū’s return from the continent -- after which Jōō incorporated numerous changes in light of the new material that Rikyū brought back with him from Korea).

†Locating the ko-ita furo on the left (as shown above) was also the arrangement preferred by Hideyoshi (perhaps under the influence of Sōkyū: this manner of arrangement also makes it easier for the guests to see everything the host is doing, whereas placing the furo on the right tends to hide many of the host’s actions behind its bulk -- Hideyoshi was perennially fearful of being poisoned, a method of assassination said at that time to be preferred by the followers of the Ikkō-shu [一向宗], the Amidist sect of Buddhism with which most of the Sakai machi-shū-chajin were at least nominally affiliated), hence it might have felt “less controversial” to employ this version of the arrangement on the present occasion (not only out of respect for Sōkyū’s sense of propriety, but because several of the other guests were also employed as Hideyoshi’s tea masters).

That said, it could have been precisely for this reason that Rikyū may have decided to locate the furo on the right -- in order to illustrate to the assembly the theoretically appropriate way of doing things (less the habit of doing things in the way preferred by Hideyoshi induce a state of forgetfulness).

¹⁴Shiru saku-saku [汁 サク〰].

This was miso-shiru containing coarsely chopped greens from the kitchen garden. The chopped greens were added just before the soup was served, so they would still be crisp when eaten (this is what the onomatopoeaic saku-saku means).

¹⁵Shigi yakite ・ kamaboko [鴫 ヤキテ ・ カマホコ].

Shigi [鴫] means snipe* -- a shore-bird; a type of sandpiper. While Rikyū does not go into the details of its “roasting,” cooking the birds in the senba-iri [船場煎り] style† seems likely.

Kamaboko [蒲鉾] is boiled or steamed fish-paste. in Rikyū’s day the kamaboko was probably formed into cylinders (possibly hollow tubes, which insured faster cooking times), or flattened into patties, and then deep-fried in oil (by the shop that produced it) -- it could be offered to the guests as it was received from the shop (warm to cold), or be reheated before being served.

These dishes would have been accompanied by the service of several rounds of sake. ___________ *Shibayama Fugen’s manuscript, however, has kamo [鴨], meaning the wild duck. The kanji are similar; and perhaps shigi seemed a bit too “exotic” for the late Edo-period palate of the gentleman responsible for producing his copy of the Nampō Roku. (We must remember that making copies -- or even writing down notes -- while in the Enkaku-ji, was strictly forbidden. Thus the material could be committed to paper only after the person -- I do not believe the name of the person who made the original copy is actually known -- took his leave.)

That said, shigi was also served at a gathering mentioned in the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki [利休百會記] -- albeit in that case, it was mashed and formed into dango [團子], and served in a clear broth.

†Senba-iri [船場煎り] refers to a style of cooking employed in the food stalls located along the wharves at Sakai. It was used primarily for preparing small birds (and, incidentally, prawns as well). In this case, the entire bird (plucked, and with the head, feet, and innards removed) was threaded or tied onto a spit and roasted over a small wood or charcoal fire in a brazier, while basting them with a mixture of sesame oil, soy-sauce (or iri-zake [煎り酒]), sake, mirin, and crushed garlic. (The wood fire added an interesting dimension to the food’s flavor -- since in Rikyū’s day most home cooking was done over charcoal.)

¹⁶Asa-zuke [アサツケ].

Asa-zuke [淺漬け] are a simple kind of home-made tsuke-mono (the type is often referred to as o-shinkō [お新香] today). Naturally crisp vegetables -- such as immature cucumbers, daikon, hakusai, Japanese eggplant, and the like -- are either dusted lightly with salt (usually small slivers of dried kombu [昆布] -- kelp -- are added during this step as well), kneaded with the fingers (to distribute the salt evenly), and then left to stand under a light weight (which helps to press out the water).

Alternately, the vegetables and kombu can be placed in a brine solution to pickle.

In either case, they are left to stand anywhere between several hours and overnight. The process removes the extra water, increasing the natural crispness of the vegetables.

¹⁷Senbei ・ yaki-guri [センヘイ ・ ヤキクリ].

These were the kashi:

- senbei [煎餅], rice crackers, which were usually obtained from a professional confectioner (and often, in the case of Rikyū’s chakai at least, received as a gift from one of the guests* -- rather than being procured for this purpose by Rikyū himself); and.

- yaki-guri [焼き栗], chestnuts roasted over a charcoal fire. ___________ *Unlike in the present, money was not considered an appropriate thank-gift for the guests to give to the host. Elegant senbei, or other things of that sort, were preferred. Since the guests were all chajin, they would likely have bought such a gift as a group, after consulting with each other.

¹⁸Go [後].

The goza.

As for the kane-wari:

- the scroll remained hanging in the tokonoma, and so it remained han [半];

- in addition to the ko-ita furo, the room contained the mizusashi (with the sa-tsū-bako arranged in front of it, and the hishaku resting on top -- all of which counted as a single unit), and so was chō [調].

Han + chō is han, which is appropriate for a gathering held during the daytime.

¹⁹Toko sono-mama [床其儘].

The kakemono remained hanging in the toko, as it had been since the guests finished inspecting its gedai during the shoza.

²⁰Mizusashi Shigaraki, ue ni hishaku [水指 シカラキ、上ニヒシヤク].

This was Rikyū's Shigaraki mizusashi.

The hishaku was placed on top, with the butt end of the handle touching the second kane, as explained in the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 2 (46): (1587) Eighth Month, Second Day, Morning*, under footnotes 14 and 16. ___________ *The URL for that post is:

http://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/184163345058/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-2-46-1587-eighth-month

²¹Sa-tsū-bako [棚ニ茶通箱].

This entry is marked with a red dot, indicating its importance. This would have been a futatsu-iri sa-tsū-bako [二つ入り茶通箱], a sa-tsū-bako made to hold two containers of tea (this is the kind usually seen today* -- though what kind of lid the box may have had cannot be verified: the box shown below has what is known as a yarō-buta [藥籠蓋]).

The sa-tsū-bako was probably placed in front of the mizusashi†. __________ *Based, apparently, on the precedent of this chakai -- though this chakai is, in fact, not representative of the way that Rikyū usually handled the sa-tsū-bako (when he was sending a gift of tea to someone else). Rather, it shows the way that Jōō may have been doing things during his middle period (this is where the machi-shū tea of Sōtan, on which modern day chanoyu is based, originated).

This anomaly has fueled certain suspicions that this chakai is at least in part spurious -- and was possibly modified or inserted into the kaiki to provide a Rikyū-based precedent for the way that the Sen family was handling the sa-tsū-bako and its (by that time, “secret”) temae.

†Shibayama Fugen, however, notes that if the chaire contained in the sa-tsū-bako (he seems to have believed it to have been Rikyū’s Shiri-bukura chaire [尻膨茶入]) was a meibutsu, then the sa-tsū-bako should be placed on the central kane.

In this case, rather than an ordinary ko-ita, which measures 9-sun 5-bu square (shown on the left in the following sketch), a specially made smaller one (measuring 8-sun square -- the arrangement of which is shown on the right) could be used. This smaller version of the shiki-ita was arranged according to the usual rules: 5-sun from the far end of the mat, and 9-me from the heri. The effect, then, was to move the furo diagonally away from the central kane, making it possible to place the chaire -- or, in this case, the sa-tsū-bako -- on the central kane (without any danger that the heat from the furo would be close enough to damage the tea).

As with the ko-ita, this smaller shiki-ita (which was Rikyū’s creation) could only be used with a large furo (meaning a furo measuring between 1-shaku 1-sun and 1-shaku 2-sun in diameter -- whether made of iron, or of lacquered clay).

Nevertheless, Fugen admits that, in this particular case, he is unsure where the box would have been displayed (and seems inclined, on second thought, to imagine that it was more likwly placed in front of the mizusashi).

Tanaka Senshō, meanwhile, suggests that the sa-tsū-bako might have been displayed in the toko (along with the scroll, which still remained hanging as it had been during the shoza) -- though doing so would have made the apparent kane-wari unworkable (and so Rikyū probably did not do this). Nevertheless, in such a case the host (immediately after bringing the chawan into the room -- which he temporarily placed on the left side of the mat) would go to the toko and retrieve the sa-tsū-bako (for this reason, the box would have been displayed on the side of the toko closer to the toko-bashira, so that the host would not disturb the shōkyaku when he went to pick up the sa-tsū-bako). After bringing the box back to the utensil mat, the host would cut the box open with a knife, as explained under the next footnote.

²²Tadashi, uchi ni Shiri-bukura ・ ko-natsume [但、内ニ 尻フクラ ・ 小ナツメ].

The chaire is generally assumed to be Rikyū's meibutsu Shiri-bukura chaire [尻膨茶入] (shown below). But if that was the case, the source of the tea it contained (whether matcha ground that morning by Rikyū, or the gift-tea that was received from Sōkyū -- over which Rikyū seems to have made quite a fuss) becomes a matter for confusion*.

According to both Shibayam Fugen and Tanaka Senshō, the Shiri-bukura chaire contained tea that would be served as koicha, while the ko-natsume contained tea intended for use as usucha -- and this is represented, by both of them, as being the traditional assessment of the contents of the sa-tsū-bako that was held by all of the scholars (since the time of Tachibana Jitsuzan himself, and so from the beginning of the study of this document) associated with the Enkaku-ji and the Nampō Roku scholarship.

This latter assertion, too, is problematic as well, since (at least in the time of Jōō and Rikyū) the ō-natsume [大棗] was generally used for usucha, while the ko-natsume (according to Jōō -- who created both of these kinds of chaki†) was supposed to be used for koicha. If, as some suggest, the tea in the Shiri-bukura was Rikyū’s own tea, then the tea in the ko-natsume being intended for usucha is equally odd -- since the tea used for usucha was either left-over koicha‡, or ground from the inferior-quality tea leaves that had been used as packing material in the cha-tsubo. In either case, for Imai Sōkyū to promise to send a container of matcha, and then send over such poor quality tea, would be almost insulting -- and, again, does not conform with what we know of Sōkyū’s character (since he was, if anything, inclined to be self-promoting, and very concerned about “face”: if anything, Sōkyū would have sent the highest-quality tea he had, and made quite sure that Rikyū respected it properly by preparing it as koicha -- especially if this were the only tea from Sōkyū that would be served during the chakai). Furthermore, if the matcha received from Sokyu had really been such poor tea, Rikyū would have hardly made such a fuss over it

Gift tea was (originally -- and this custom was still current in the time of Jōō and Rikyū) packed into the sa-tsū-bako by the person giving the tea, and that person then sealed the box by pasting a paper tape around the place where the lid joined the sides, and applied his name-seal to the place where the two ends of the tape met (which was considered the side of the box that would face toward the guests -- meaning that the container or containers of matcha were always oriented accordingly). The host opened this tape with a small knife, using three cuts: first he cut from just beyond the name-seal away from himself (and so around the box to the side opposite the name-seal); then from just beyond the seal and toward himself (the two cuts, then, meeting on the far side of the box from that were the seal had been impressed). Then the sa-tsū-bako was passed around for haiken (with the name-seal still remaining uncut -- to verify to the guests that the contents of the box were as packed by the giver), while the host dusted the utensil mat with the habōki. Then, after the box was returned, the host took the knife and cut through the name-seal, thus freeing the lid, and so allowing him to open the box and remove the container or containers of matcha. This process is clearly described in the Nampō Roku.

It is unlikely, then, that the sa-tsū-bako contained one kind of tea prepared by Rikyū (in his Shiri-bukura chaire) and another tea (in the natsume) prepared by Sōkyū. If any of the tea was from Sōkyū, then all of the tea in the sa-tsū-bako would have been from him (and the box sealed with his name-seal); and if Rikyū still intended to use his own tea (ground that dawn and put into his own chaire, the Shiri-bukura), then the gift tea in its sa-tsū-bako would have had to be placed elsewhere until the service of tea from the Shiri-bukura was finished (since the host’s tea always took precedence in such cases). Putting the tea containers together in the same box was simply not done during Rikyū’s period -- since this would have involved cutting off the donor’s seal beforehand, making the entire process of cutting off the tape nonsensical (Rikyū’s introductory remark that the tea had come from Sōkyū certainly implies that all of the tea that was served was from him -- that the sa-tsū-bako was from Sōkyū, and so would have been sealed with his name-seal).

As an separate comment added here, Shibayama Fugen adds that, if the chaire was a karamono piece (as was Rikyū’s Shiri-bukura chaire), then, after opening the box (and seeing what it contained), the host would quietly go out to the katte and bring in a chaire-bon, and so serve the first tea using the bon-date temae**. __________ *The idea was always to prevent the tea from coming into contact with the air. Thus, the containers of matcha were always tied into shifuku (or, for gift tea sent to someone in newly-made natsume, purple, fukusa-shaped furoshiki) and loaded into the box, which was then sealed with a paper tape. The seal was not broken until the box was opened, before the eyes of the guests (according to the Nampō Roku), during the koicha-temae.

Therefore, Rikyū could hardly have received two containers of gift tea from Sōkyū, and then transferred one of them into his own chaire (since that would expose that tea -- which would have been the better of the two -- to the air, potentially ruining it, and causing grave insult to Sōkyū). Neither could he have included his own chaire of tea in the box with the gift tea (in a ko-natsume), since the box would have been packed and sealed by Sōkyū (in his own home, immediately after grinding the tea). It may have been possible that Sōkyū borrowed Rikyū's chaire; but it seems that people of that period did not usually do such things -- since there would have been nothing to prevent the borrower from showing the chaire secretly to his friends (though, given Sōkyū's status -- and his personal commitment to maintaining his reputation -- it is unlikely that he would have breached Rikyū's trust in this way). Therefore, the most likely possibilities -- assuming that this kaiki is authentic (something which these particular details tend to make less likely) -- are either that Sōkyū used his own shiri-bukura chaire (which has not been identified) -- if, indeed, a shiri-bukura chaire even originally figured into this -- or that he borrowed Rikyū's chaire for this purpose.

However, all of that aside, if things were done “correctly,” the sa-tsū-bako would have contained two natsume (perhaps a ko-natsume of koicha and an ō-natsume of tea intended for usucha -- though it is also possible that it contained two ko-natsume, both holding koicha-quality tea), and that the words “Shiri-bukura chaire” were added by someone who wanted to make this sa-tsū-bako temae appear identical to what the Sen family was teaching.

Imai Sōkyū, it must be remembered, was married to Jōō's sister (I have said this before; but this point is extremely important if one wishes to understand Sōkyū and his motivations); and his practices tended to mirror Jōō's own usages from his middle period (during which time Jōō preferred using one variety of matcha for koicha, and a different, slightly lower-quality tea for usucha); he also had an extensive collection of high-quality tea utensils (a number of which had come from Jōō’s collection -- taken by Sōkyū to reimburse himself for the expenses of raising Jōō’s son Sōga). But I have never seen it alleged (in contemporary documents) that Jōō placed a chaire and a natsume together in the sa-tsū-bako; nor that Jōō taught that the sa-tsū-bako should be opened by the host (before the chakai began) and then repacked so that it would contain his own chaire along with the gift tea (whether the chaire also contained gift tea, or tea ground for the occasion by the host).

All of the documented instances of the use of a sa-tsū-bako from Jōō’s and Rikyū’s period clearly imply that:

- the sa-tsū-bako contained only the gift tea (never tea prepared by the host);

- that the gift tea was to be placed in newly made natsume (or other new lacquerware tea containers) of an appropriate size (this was done precisely so that it would be the tea that was important to the guests, not the container in which it had been sent);

- and, that the sa-tsū-bako was packed by the donor, and sealed with his name seal, and that the sa-tsū-bako was not to be tampered with until the box was cut open in front of the eyes of the guests, who would then be served the tea it contained (this because it was the reputation of the donor that was at stake, rather than that of the host: tampering with the box could make the donor loose face, if the tea proved to be bad).

Tachibana Jitsuzan, Shibayama Fugen,Tanaka Senshō, and the group of scholars affiliated with the Enkaku-ji, however, were all products of their age. Since they only knew the sa-tsū-bako temae taught by the Sen family (which holds that the sa-tsū-bako was prepared by the host, to contain a chaire of his own tea, plus a natsume or other container of gift tea), it seems that none of them were able to imagine anything different -- even though the differences are actually described elsewhere in the Nampō Roku itself. This kind of inflexible attitude remains the bane of Nampō Roku scholarship, even to this day.

†Since Imai Sōkyū was not only married to Jōō’s sister, but also the de facto guardian of Jōō’s son (and heir), he appears to have been a stickler for adhering to Jōō’s teachings and practices, at least in so far as he was aware of them. (Sōkyū, together with many of the machi-shū, had a sort of falling out with Jōō during the last year of his life -- after Jōō began to modify many of his teachings in light of the new information that Rikyū had brought back with him from the continent. This last one-year period is what saw the incredibly rapid evolution of the small room, along with the advancement of extremely wabi practices -- in contradistinction to what Jōō had championed for most of his professional life.) Thus, it is highly unlikely that Sōkyū would have so wantonly rejected one of Jōō’s basic teachings by using the ko-natsume for a purpose for which it had not been intended.

‡In other words, koicha-quality matcha left over from tea that had already been placed in a chaire and used to serve tea at an earlier gathering (it was considered rude for all of the tea in the chaire to be used, in case the guests wanted to drink more: thus, the host always selected a chaire that was larger than necessary, and the tea container was always filled fully, with the intention being that a certain amount should always remain in the container at the end of the temae, as a sign of the host’s courtesy and concern for his guests): such tea could only be used later for usucha, because it had already been exposed to the air too much -- meaning that the volatile constituents (which contribute heavily to both the aroma and taste of the tea) would have been lost, for the most part.

**Or, more specifically, a meibutsu karamono chaire (that had been paired with a tray). In Jōō’s and Rikyū’s period, only karamono chaire that had been paired with a tray were used for bon-date (by Rikyū’s day, ko-Seto chaire were also acceptably used in this way -- assuming that they had been paired with a tray) -- and, since the tray had to agree with the proportions of the chaire exactly (according to both Jōō and Rikyū), it would have been impossible for the host to simply bring out any “random” tray, historically speaking, at this point in time (the idea of using “any small tray” began with Sōtan and his followers, as a result of ignorance of Rikyū’s teachings -- or perhaps as a deliberate rejection of the way that Rikyū had done things), on the spur of the moment, after finding such a chaire in the sa-tsū-bako . This highlights (albeit inadvertently, so far as Shibayama Fugen’s comment is concerned) the difference between practices in Rikyū’s day and his own (which, as is also true of modern-day chanoyu , followed directly from Sōtan’s machi-shū style of chanoyu).

“For the record,” Jōō's chaire-bon was supposed to be (exactly) 3-sun 5-bu larger on all four sides than the chaire that would be used on it; Rikyū’s chaire-bon (which was notably smaller than Jōō’s tray), was 2-sun larger on all four sides. These measurements were supposed to be exact (the tolerence is less than 1-bu in the case of all of the old chaire and their trays that have survived), and even modest deviations were generally rejected. If one had a tray that conformed with the chaire, and that chaire was deemed worthy of being used on a tray, then one did bon-date. If either of these conditions were not true, then the chaire was supposed to be used without a tray.

²³Habōki [羽帚].

The habōki (which was a larger one, made from feathers that were between 9-sun and 1-shaku long -- the kind that is usually seen today) was placed on the left side of the mat, next to the heri.

According to Shibayama Fugen, it was used to dust the utensil mat just before the sa-tsū-bako was (finally) cut open and the first container of tea taken out.

²⁴Su [ス].

The utensils that follow this notation (the chawan; and, though not specifically mentioned in the kaiki, the koboshi and futaoki) were brought out from the katte at the beginning of the koicha-temae, rather than being displayed in the room when the guests entered the room for the goza.

Su [ス] is an odd modification of the kanji mata [又], used consistently in this book by Tachibana Jitsuzan. It is intended to mean “also,” “and again.”

²⁵Chawan kuro, ori-tame [茶碗 黒、 折撓].

Though usually assumed to be one of Chōjirō’s early black bowls, it seems more likely to have been the hiki-dashi-kuro chawan that Furuta Sōshitsu made for Rikyū the year before -- the chawan that is shown below (which bears Rikyū's kaō, as a mark of his ownership, on the bottom) -- since Rikyū would have been extremely sensitive to avoid any charges of self-promotion leveled after the fact by this group of guests.

Consequently, it does not seem that Rikyū would have used one of Chōjirō's bowls (since those bowls were known to have been produced under Rikyū’s watchful gaze -- and those not approved by him were destroyed), since a certain reticence would have seemed to be called for during this chakai. His own creativity would have been sufficiently demonstrated by the use of one of his own chashaku -- made to accompany the main tea container, Rikyū's meibutsu Shiri-bukura chaire [尻膨茶入] -- and the use of a take-wa [竹輪] as the futaoki (below) -- and the other unimportant (though necessary) utensils.

While nothing is said, it seems most likely that Rikyū would have used a take-wa [竹輪] as his futaoki, and a mentsū [面桶] as the koboshi.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 Anime Music Groups That You Need To Stop Sleeping On

What keeps you watching anime? For some it’s the thrill of seeing Hibiki punch God. For others, it’s unexpectedly nuanced character animation, or end-of-episode plot twists that make you desperate for the next. For me, it’s anime OPs and EDs. Every season I’ve been guaranteed a new avalanche of music videos, and at least one or two of them earn the coveted honor of me watching them every day six times in a row. But now what if I was to tell you that some of the music artists who’ve worked on anime have their own albums, and that some of those albums are very, very good?

Let’s talk about some of the bands featured in anime that easily hold their own weight off the screen.

youtube

“KIMI NO SEI KIMI NO SEI KIMI NO SEI DE WATASHI OOOH….OKUBYOU DE KAKKOU TSUKANAI KIMI NO SEI DA YO!” Once upon a time I was just like you, one who has not listened to the theme song of Rascal Does Not Dream of Bunny Girl Senpai. But then I watched the credits for the first time, and…well, it’s over. The song is lodged in the recesses of my brain and will pop back out, at the smallest notice, to play on end for the rest of the day at the least provocation.

"Kimi no Sei" is one of my top anime theme song bangers of the decade, and it was created by an all-female group from Kanagawa called the peggies. They’ve put out three albums so far, propelled by dreamy vocals and crunchy guitars. I tend to gravitate more towards the harder-rocking songs like "Kimi no Sei", but it’s all at least pretty good. And don’t just take it from me: their most recent single was chosen to accompany Kunihiko Ikuhara’s Sarazanmai, joining the ranks of Coaltar of the Deepers and J. A. Seazer in the director’s oeuvre.

Where to start?: Their most recent album is Hell Like Heaven, which features "Kimi no Sei"! But you may enjoy their first album, goodmorning in TOKYO, as well.

youtube

I loved the first ED for Dororo, performed by the great goth rock band amazarashi and animated by the fantastic Osamu Kobayashi. But I found the second ED to be excellent as well, a sad and fuzzy ballad set to an out-of-focus mess of sad and fuzzy colors. Months later, I began to see animation fans on Twitter excitedly sharing music videos featuring a J-pop artist known as Eve. So I’m embarrassed to admit that it wasn’t until a few weeks ago that I realized that the Eve hosting these music videos, and the Eve who sang the second ending theme for Dororo, are the same person! The videos on Eve’s channel are all quite different, featuring a murderer’s row of independent and more broadly known animators. But there’s a shared language of apocalypse and adolescent fear that hints at a shared universe connecting them.

Where to start?: You could do much worse than comb through Eve’s YouTube feed for videos that seem cool. I particularly enjoyed this one, which features art direction by Yuji Kaneko (who’s worked on the Little Witch Academia OVAs and Kill la Kill.)

youtube

I was excited for the first episode of Stars Align, the new project by Noein: To Your Other Self director Kazuki Akane. But what caught me most off guard in the first episode wasn’t the efficient characterization, or the shocking appearance of the protagonist’s abusive father, but the music. A kind soul on Twitter introduced me to the work of the show’s composer, a Kyoto-based group called jizue that is the best musical discovery I’ve made this year.

Not quite postrock, not quite math rock—music fans refer to them and their kin as “nujazz”—they’re an immediately distinctive band with an extensive back catalogue of work to explore. Of course, the kind of music they specialize isn’t for everyone, and can become wearying over sustained listens. But with their most recent album, Gallery, specifically aiming to spotlight individual members and pull themselves out of their musical comfort zone, there’s a lot of life in them yet. Either way, Akane’s use of their work immediately sets Stars Align apart from the sports anime pack.

Where to start?: Folks seem to really like their second album “novel” from 2012. You could also jump to Bookshelf from 2016.

youtube

It’s safe to say that Kenishi Yonezu is a big deal. Since being featured on My Hero Academia’s second opening, "Peace Sign," he’s contributed theme songs to March comes in like a lion, Children of the Sea and the TV drama Unnatural. He’s collaborated with hot artists like DAOKO. Heck, he even co-created an independent music label together with several other stars of the Japanese video site Nico Nico Douga. There’s the catch, though: Yonezu rose to prominence not just through his voice, but on the strength of his work as Hachi, an independent composer on indie videos featuring Hatsune Miku.

It’s a route to superstardom that simply did not exist a decade ago, and Yonezu as much as anyone represents the new paradigm of Japanese pop music. His most recent work is certainly a world away from the less polished, but spirited work that made his name. But his single for Children of the Sea is excellent, bridging the divide between Yonezu the pop star and Yonezu the master of subculture.

Where to start?: Why not go to “diorama,” the independent album he released in 2012?

youtube

There aren’t many bands out there quite like Shinsei Kamattechan. They earned their cult following online, posting freaky music videos on Nico Nico Douga. Since then they’ve released a handful of albums, and contributed to theme songs ranging from Ground Control to Psychoelectric Girl to Flowers of Evil to Attack on Titan. In recent years, their work has become a bit more accessible, sanding off the nastiness from their earlier work. But the appeal remains: fantastically catchy tunes coupled with bizarre, often disturbing lyrics.

Shinsei Kamattechan speaks to the same millennial angst that powers the work of manga luminaries like Inio Asano and Natsujikei Miyazaki. Listening to their work can feel like being trapped in the middle of a thunderstorm, but it can be weirdly exhilarating as well. Of all the bands on this list, these guys are my sentimental favorites. Check them out, if you dare!

Where to start: If you’re brave, begin with their sophomore album Tsumanne. You could also try out their later album Eiyuu Syndrome, which is much brighter and poppier but still has some incredible bangers on it.

Of course, there’s plenty of other artists we could talk about. What about Asian Kung Fu Generation and their legion of anime theme songs? What about legendary rock band the pillows, who gave FLCL so much of its personality? What about JYOCHO, who did a fantastic ending theme for Junji Ito Collection? Well, we’ll just have to talk about those next time. Until then, Shiina Ringo takes us out:

youtube

What are your favorite Japanese bands? Do you have any favorite bands from outside of Japan that have contributed music to anime? Let us know in the comments!

---

Adam W is a Features Writer at Crunchyroll. He wrote another post in this vein on the blog Isn't it Electrifying, which he sporadically contributes to with a loose collection of friends. Follow him on Twitter at: @wendeego

Do you love writing? Do you love anime? If you have an idea for a features story, pitch it to Crunchyroll Features!

0 notes