#ilana krausman ben amos

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

other recs:

Adolescence and Youth in Early Modern England - Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos

Mary I: England’s Catholic Queen - John Edwards

Elizabeth I: A Study in Insecurity - Helen Castor

Queenship at the Renaissance Courts of Britain: Catherine of Aragon and Margaret Tudor - Michelle L. Beer

The Politics of Female Alliance in Early Modern England - Christina Luckyj and Niamh J. O’Leary

Better a Shrew than a Sheep: Women, Drama, and the Culture of Jest in Early Modern England - Pamela Allen Brown

The Heart and Stomach of a King: Elizabeth I and the Politics of Sex and Power - Carole Levin

Mary and Philip: The Marriage of Tudor England and Hapsburg Spain - Alexander Samson

hello! I’m a literature/history student who knows next to nothing about tudor history or the english renaissance (beyond simple basics). I’ve gotten more into it because I’m taking a shakespeare class and that’s all relevant historical background, but I’d love to get more in depth. obviously you don’t have to answer, but I was wondering if you had any books/documentaries/articles that I could maybe start with? or some writers of the time that I could become acquainted with. I’d just like to get a better understanding of the era, so any help would be appreciated :)

hmm if you’re doing a shakespeare class, i would recommend focusing on elizabethan (and jacobean) research primarily, as that’s more contemporary to shakespeare! unfortunately, that is not really my area, so i don't have specific recommendations for you.

i haven’t read shakespeare on an academic level in years — but which plays you do will likely influence your reading list. so i don’t know how helpful my recommendations would be, but off the top of my head:

tudor england: a history, lucy wooding as a good overview - i don’t agree with everything in it, but i think it is a good, accessible, up-to-date summary of the period!

shakespeare and the italian renaissance, michele marrapodi is good! personally i would recommend reading about italy and the mediterranean; shakespeare himself clearly did not know much of italy, and the mediterranean often exists as a semi-fantastic, exoticised other world. but italy and tropes about italians were influential for early modern writers; so reading up on the renaissance — including petrarch as an example — might be helpful. (it might help to look into commedia dell’arte, too.)

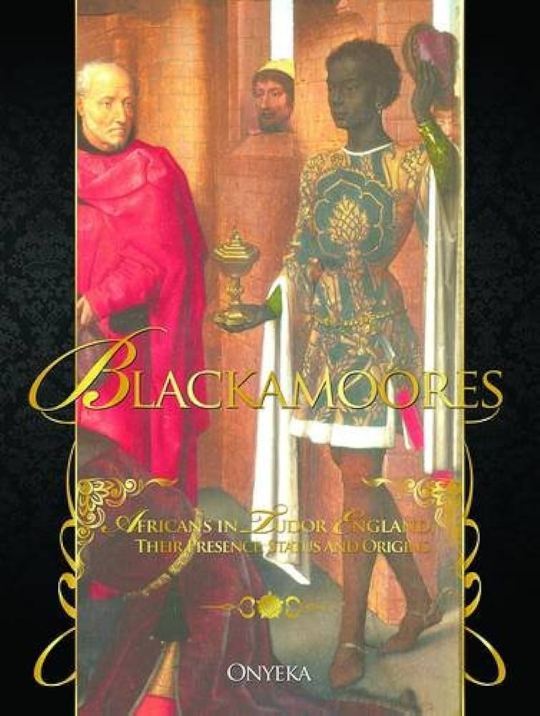

black tudors, miranda kauffman, and blackamoores, onyeka, for discussions of race and anti-black racism. i haven’t got a specific book to recommend but definitely be conscious of how prevalent antisemitism is in shakespeare’s works, alongside other racialised stereotypes and epithets.

gender in early modern england, laura gowing. gender and gender expression is played with a lot in shakespeare, and they had some genuinely interesting feelings regarding crossdressing, and subversions of gender roles. off the top of my head there isn’t a perfect book that covers everything, but gowing’s work is pretty good!

as for the english/northern renaissance specifically, i’ve not actually read many broader overviews (and not super recently), and i don’t know how specific you want to go:

the english renaissance 1500-1620, andrew hadfield or a companion to english renaissance literature and culture, michael hattaway were solid as starting points.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...Among the wealthier urban classes, women were more likely to stay at home than their counterparts lower down on the social scale; and overall there is some evidence to suggest that women in their teens were somewhat more likely than men to remain in their parental homes, especially if their mothers were widowed. Nevertheless, the majority of women did leave home, whether to advance themselves by finding a proper match, or, more frequently, to find suitable employment. Even among the middling and more prosperous classes such moves were hardly unusual.

…Most women probably left home because their parents lacked the means to support them and they had no proper employment at home, or because they were orphaned; among women apprentices in seventeenth-century Bristol, as we have seen, there were many orphans who were compelled to leave home and find suitable employment in the large town. Often these moves involved long-distance migration to towns, where women became lodgers in the houses of kin or domestic servants.

Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, most women migrants in London entered domestic service, and in Bristol well over a third of the women registered as apprentices for a long seven-year term were hired as housewives or serving-maids. Many more must have been hired on an annual basis to serve in the houses of merchants, mercers, grocers and numerous other craftsmen.

By the late seventeenth century the employment of domestic female servants among London's middling classes was virtually universal, and many provincial towns and smaller urban settlements also had a large sector of female servants. As David Souden has shown, by the later decades of the seventeenth century, when in the country as a whole long-distance migration contracted, migrants to the large towns were disproportionately female.

Most of these women were in their late teens and early twenties, and the distances they travelled to towns like Exeter, Salisbury, Oxford, Leicester and others were only slightly shorter than those travelled by men. In general, these young women tended to reside in the wealthier, inner parishes of towns, where the demand for domestic servants was high. From the late seventeenth century and throughout the eighteenth, there was a marked female domination - including many young migrants - of the growing populations of towns.

Life as a domestic servant was strenuous and physically very demanding, especially for those serving in the larger houses of the more affluent urban classes, where great effort went into cleaning, washing and scrubbing kitchens, stairs and floors. Kitchen work and cooking were especially arduous and dirty, and the workload, when families were entertaining guests, could be great. In small urban shops, too, the work of the domestic servant could be demanding, even when the house was small and living standards relatively modest.

As we have seen, by the seventeenth century Bristol's women apprentices were often employed in domestic services, as well as in textile work - knitting silk stockings or spinning. …The maids employed by a number of tobacco-pipe makers in Bristol might well have begun their work as domestic servants, and those who were hired as domestic servants must also have assisted in the shops of their masters - haberdashers, grocers, cheesemongers, chandlers, shoemakers, tailors and the like. Others helped in the inns, ale-houses and eating houses of their masters or mistresses.

…Like their male counterparts, domestic servants left service rather frequently. Marjorie K. McIntosh referred to a domestic servant near Romford, in Essex, who worked for three mistresses and a master, before migrating to London. In none of the households did she spend the full term of her contract. Once in the town, women not infrequently continued their moves. In some apprenticeships, a young woman was provided with a bond of security which allowed her to leave service if she saw fit.

Most women were not guaranteed with such bonds, but they nonetheless left their masters or mistresses at the end of their terms, and often before. In early seventeenth-century London, domestic servants sometimes spent long periods of service with single masters, but often they stayed in one household no more than a year or two, and occasionally even less. By the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, female domestics were notorious for their tendency to change places of employment, and the turnover in some households was quite remarkable.

Movement between different masters necessitated the acquisition of a range of skills to suit the requirements of different households. Among the women who were apprenticed in Bristol in the seventeenth century, and who appear to have found places on their own, there were daughters of husbandmen and craftsmen from the countryside who had probably been employed as cooks, dairymaids or agricultural servants before their arrival in the town. By the time they had lived in the town and changed one or more households, they had acquired a range of household and other skills, and encountered divergent household economies.

While domestic service as such hardly prepared them for independent vocations, the experience entailed in living in various households could enhance their understanding of the economic strategies of different rural and urban families, and of the risks that were involved. When William Stout considered selling one of his shops to his former apprentice, he consulted his older sister, but also his maidservant. The maid was quite confident that such a decision was mistaken, and told Stout that he should not 'give over trade'. Stout took her opinion seriously, and eventually decided to withdraw from his plan.

…Marriages between domestic servants and apprentices, from the same neighbourhood if not the same household, were probably quite common. Women who married after several years in domestic service could offer invaluable household skills such as sewing, knitting, brewing, cooking, washing, and rearing children; they could contribute small dowries they had themselves saved; and they could also provide practical understanding in managing small trade, in supervising apprentices, offering advice, and managing shops when occasion required. Many couples must have begun a joint enterprise on the basis of the divergent skills and experiences obtained before marriage by both husbands and wives.

Perhaps above all, women brought with them into marriage the experience of long years during which they learnt to cope with many tasks, and to switch between different skills, masters and working environments. The ability to pull resources from a variety of jobs, to find new employment, to apply a range of skills when confronting uncertainties and hardship must have been pertinent to the maturation of most women, and not just among the very poor.”

- Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos, “Women’s Youth: The Autonomous Phase.” in Adolescence and Youth in Early Modern England

#adolescence and youth in early modern england#renaissance#history#servants#marriage#elizabethan#jacobean#caroline era#restoration#georgian#ilana krausman ben amos

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In many ways the decisions regarding marriage and the choice of a marriage partner reflected the past experiences of couples: their family relations and interactions, their material fortunes or disadvantages, their divergent gendered roles, and the independence - in actions and habits of mind - they had already gained.

Given the important role of parents and kin in providing security and assistance at critical moments throughout adolescence and beyond, it is hardly surprising if parents interfered with, or tried to exert influence on, matters concerning the marriage of their children. This was of course true of the upper classes and some families of the middling classes, among whom there was considerable parental influence in the choice of marriage partner. But lower down the social scale parents also had a say, and their consent was considered essential to successful marriage.

…The social and economic standing of prospective spouses were important considerations in the choices people made regarding their marriages. Many recognised the benefit of a good marriage, and social patterns of marriage during this period show many endogamous unions: people tended to marry within their own ranks. This was a consequence partly of the values inculcated in children at an early age - especially among the upper and more prosperous social groups - but also of the experiences they encountered during many years of service and labour outside home.

…Among more prosperous groups, young men chose women from their own social milieu, even when their parents were deceased and they were relatively free to pursue their own tastes and inclinations. …The independence of mind and the social skills the young had obtained by their mid-twenties were also evident in most of these decisions on marriage. Gender-related roles diverged quite dramatically: while men became heads of households and owners of shops and land, women entered matrimony in a subservient status, and legally lost whatever financial independence they had obtained.

Nevertheless, the skills and independence of judgement they had acquired in many years of service and other work were indispensable, and ensured a certain cooperation and mutuality between spouses. Women entered marriage as 'true help-meets . . . both inwardly and outwardly,' as George Bewley put it. Many autobiographies also point out the love and affection that drew two people into married life, and the autonomy with which both made their choice. Gervase Disney, the son of a gentleman, was offered the opportunity to meet a potential future wife, but was also assured that he could choose to decline the offer.

Lower down the social scale the independence in choice of spouse was more marked. Edward Coxere, who expected and obtained the permission of all the adults concerned, approached his parents and those of his future wife only after the matter was 'confirmed between us both'. Other autobiographies suggest similar procedures.' Social skills can also be seen in the interaction of youngsters with their parents. Marriage cases dealt with by the ecclesiastical courts show that some children boldly confronted parents who opposed their choice of spouse, and even took legal action against them, although they often lost their cases.

Most people, however, used means and tactics other than the law, and these are bound to have been much more effective. The autobiographies give a glimpse of the intricate ways in which children put pressure on their parents to obtain their approval, and so make their marriage economically successful and socially legitimate. Caution in approaching parents and in preparing the ground during the long months of open courting which preceded the marriage, persuasion, arguments and discussions, and negotiations and manoeuvring based on long years of acquaintance with parental tastes and habits of mind, were all involved.

Phineas Pett met with resistance from his kindred, but being 'determined resolutely' to marry his chosen woman, was able to persuade them, admittedly 'with great difficulty'. He was then 28 years old and already quite competent in his craft as a shipwright. Elias Osborn's father was opposed to his intention to marry a widow's daughter, who lived nearby, because of her religious persuasions. 'But I believed, and so did not make haste, but would wait Times when he was in a loving Temper, and then speak to him again.' Soon after, Elias's father realised that his son was 'grounded' in his decision, and so he gave in.

Such tactics often met with considerable success, for by the time they were in their mid- and late twenties the relationship between children and their parents had been transformed. People who reached this age - and who for many years had earned their own living, relied on a wide range of social ties, dealt and negotiated with masters and other adults - were likely to use, with a degree of sophistication, a variety of means to counter or circumvent parental opinion and achieve cooperation. And while considerable moral and financial pressure could be exerted by parents, their adult offspring were at times no less likely to use similar pressures.

When he was about to marry, Edward Coxere took parental cooperation and assistance for granted, for, as he himself explained it, there were wages and monies he had sent them while he was still an apprentice.' By the time most people - men and women - married, they had already achieved a delicate balance of power with their parents, and simple obedience to parental dictates was unlikely to occur. Nor was such blind obedience always expected, even by adults.”

- Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos, “Rites of Passage: Transition to Adult Life.” in Adolescence and Youth in Early Modern England

#ilana krausman ben amos#adolescence and youth in early modern england#marriage#history#renaissance#elizabethan#jacobean#caroline era#restoration#georgian

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...Everyday diversions occurred most frequently around the house, and often at the nearest ale-house, a place where many servants and apprentices, both male and female, congregated to pass the time in drinking, playing cards, talking, and just 'being merry,' as Roger Lowe referred to it. Lowe spent a great deal of his time with friends and neighbours at ale-houses, drinking, playing and talking. During the month of September 1663, for example, he mentioned in his diary going to the ale-house seven times, mostly on weekdays, but once also on a Sunday, from noon on. Lowe was a devoted Presbyterian who also spent a great deal of his time at prayer and religious meetings, so his experience may underestimate the frequency with which other youngsters attended the local ale-house.

Some holidays and other days in the year were also specifically associated with young people and with servants. Shrovetide and its customs of games, contests and cockfights, May Day with its maypoles, games and revels, were primarily festivals for unmarried young people, and they attracted many youths in both towns and countryside. In Gloucestershire in 1610, a maypole was set up at the parish church of Bisley, with piping and dancing by the 'youth of the parish'. Hiring fairs, especially from the late seventeenth century on, were occasions for the diversion and recreation of farm servants, who spent the day drinking, racing and dancing.

There was a variety of competitive, sometimes dangerous, games and sports in which the young men could display their physical prowess and masculinity: football and other ball games, skittles, archery, throwing the sledge, and cudgel and sword play. There are indications of customs involving coronation of lords of misrule: for example the young men who invaded the parish church in 1535 with pipes and minstrels, preparing to choose a lord of misrule to preside over the Christmas holidays.

There were also, on occasion, initiation rites involved in becoming journeymen, perhaps apprentices, too. Some types of popular literature, especially romance and heroic stories and ballads, catered mostly for the young; and small, cheap 'merry' books - with jests, old tales, sometimes with woodcuts and pictures - were bought by 'young men laughing', 'maides smiling' and 'pretty lasses feeling in their bosomes for odde parcells of mony wrapt in clouts'.

Dancing, organised in the open space, the barn or the ale-house, attracted mostly the young. Patrick Collinson has shown that if there was one youthful activity which aroused the particular anxiety of moralists it was dancing, 'the vilest vice of all’. Compared with adults, young unmarried people were likely to spend more time in these types of diversion and recreation. William Lilly remembered that during the spring of 1624, dozens of boys would congregate near the house of his master in London, 'some playing, others as if in serious discourse' from about five or six o'clock in the afternoon and until 'it grew dark'.

Young people had fewer responsibilities than adults, and once they finished their daily routine of work, in the fields or in shops, they spent their time in leisure, play and talk. Urban apprentices were especially notorious for their habits of drinking, playing dice and cards, and gambling; Gervase Disney described how on Sundays he and other companions, all London apprentices, spent time in 'walking from place to place for pleasure'. Such leisurely excursions could continue throughout the night, as is suggested by ordinances of Bristol's merchant adventurers who forbade their apprentices to walk abroad late at night.

…Youths walking in the streets late at night, sitting in the front of shops during the days, walking in the fields, drinking at the ale-house, chatting, joking, perhaps engaging in some forms of cruising or loitering were a normal part of the urban and rural scene. As one disapproving contemporary summarised it: 'many lazy losels and luskish youths both in towns and villages. . . do nothing all the day long but walk the streets, sit upon the stalls, and frequent taverns and alehouse.’ Youths were also more liable to become unemployed. In between periods of an annual service, when their service contract was broken, when they were dismissed and left service and were unable to find a new master, some youths returned home and worked on an irregular basis, or failed altogether to find some form of work or service arrangement.

…Nevertheless, the cohesiveness of these forms was undermined by other, no less powerful, forces, and such cultural forms were an integral part of broader patterns of recreation and culture shared by youths and adults. The streets, the fields, the marketplaces and fairs, even the ale-houses, were seldom monopolised by the young. The ale-house catered for the young, but along with them came the craftsmen, the labourers, and other married men, young and middle-aged. Within the alehouse, youths sometimes congregated, but they also intermingled with married men, and at times with their own masters. The small numbers of people who attended the local ale-house on a single evening made the interaction of generations almost inevitable.

…Even dancing was often a community affair from which the middle-aged and the old were not wholly excluded. Sometimes dancing was an event designed specifically for farm servants, milkmaids and domestic servants from several villages in the area. But more often, organised dancing took place as part of festivities in which the whole community took part: parochial ales, which still flourished in some places, fairs, weddings, and a host of other celebrations. Midsummer celebrations frequently included feasting, singing and racing, as well as organised dancing, and harvest dinners and feasts could include masques and masquerading, as well as dancing.

On these occasions older people were generally spectators, but sometimes they participated as well. Even May Day dancing was not an event organised exclusively for or by the young. Richard Baxter, a keen observer of 'youthful' follies and young people's predilection for sin, noted how in his Shropshire village 'all the town did meet together' under a maypole, spending a great deal of their day in 'dancing'. His description of the event evokes the strong sense of a community event in which the ages intermingled; the piper, he recalled, was one of his father's tenants, probably an adult.”

- Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos, “Spirituality, Leisure, Sexuality: Was There a Youth Culture?” in Adolescence and Youth in Early Modern England

#apprentices#servants#history#renaissance#elizabethan#jacobean#caroline era#restoration#georgian#ilana krausman ben amos#adolescence and youth in early modern england

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...In 1700, as in 1500, the basis of the English economy was still agricultural, and most boys and girls were reared in a rural environment. Two factors influenced the recruitment and integration of children to work. On the one hand, children were bound to be drawn into the workforce early in their lives, since about one-third of the early modern English population was under the age of 15, and labour was the most important factor of production.

On the other hand, the economy was also characterised by chronic under-employment, and children, not to speak of those of tender years, were physically limited and less skilled than adults. So their work was also bound to have been irregular and characterised by a great deal of unemployment. All this meant that children were employed to carry out single tasks as they grew up, according to the needs and types of skill required by their families.

Some of the most common tasks allocated by families to children involved animal husbandry; most authors of autobiographies who made any reference to work they had performed in their childhood years mentioned some form of work with animals - for example, sheep, geese or draught animals. Sheep growing, rearing of cattle and horses, and dairy farming predominated in the western and the northern parts of the country, but enclaves of pastoral farming also existed in the south and the east, as well as in the less fertile soils of parts of Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Norfolk and Suffolk. Many yeomen in these regions kept large flocks of sheep to manure the soil, and children assisted in bringing sheep to the unploughed hill pasture during the day, and returning them to arable fields at night.

Moreover, until well into the sixteenth century, many households in the south and the east were self-sufficient and kept some animals to provide for their basic needs. In the midland plains, for example, households relied on cereal production, but also on animals; a few cows, pigs, or small flocks of sheep which children could tend to were kept to provide cheese, butter and clothing. In other regions within the mixed farming zone there were still large enclaves of pastoral farming, as in Cambridgeshire and the forests of Suffolk, Kent, Essex and the Midlands, where wood pasture predominated and shepherding by young children must also have been common.

Where crop farming predominated in the south and the east, children assisted in a host of other agricultural tasks. Although the work was more seasonal than in the pastoral areas, some tasks were allocated to children nearly every season of the year. One major job was ploughing, especially in the autumn season, but sometimes also in the winter and the spring, depending on the crop schedules adopted by individual farmer. Thomas Carleton, William Stout, Simon Forman and Josiah Langdale all remembered working at the plough in their young years. In other seasons, children assisted in “harrowing, scaring birds once the corn was sown, weeding, picking fruit, and spreading dried dung to manure the soil in the spring and summer.

During the harvest, children also contributed their share by bringing food to those working in the field, leading horses, and helping to bind the corn into sheaves. Older children also participated in haymaking and shearing.'' Among the very poor, children assisted during the harvest weeks by gleaning alongside their mothers. Even in winter, children provided some assistance: threshing, stacking sheaves, cleaning the barn and, in places and soils that required it in the winter, ploughing as well.'' Children carried out household tasks throughout the year: fetching water and gathering sticks for fuel, going on errands, assisting mothers in milking, preparing food, cleaning, washing and mending.

In some rural industries, which expanded in the north and the west, children were also taught to spin and card, and girls were trained in hand-knitting, lacemaking and stocking knitting; the latter became, by the late seventeenth century, a large industry. In some towns, domestic industries such as clothmaking and pinmaking also provided work for children. The pinmaking industry could employ younger boys and girls to put knobs on pins by hand, and from the 1570s, when pinmaking with brass wire became more widespread, in London it was a source of living for many poor adults and their children.

Gender differences in the tasks allocated to children were to some extent already apparent at young ages. William Stout remembered that while he and his brothers were required to assist in husbandry, his sister was 'early taught to read, knit and spin, and also needle work'. When she grew up, she continued to work alongside her mother, assisting in waiting on her younger brothers, and in preparing food and clothing. Girls also provided assistance in housework: in washing, preparing food and marketing. In an estate near Bolton, payments paid by the bailiff to labourers included those for washing to 'wife Turner and her folks'. Some of these folks were probably young daughters.

But the division of tasks between boys and girls, especially among the very poor, was anything but clear-cut. In a petition of the inhabitants of Hertfordshire to King James I it was claimed that young girls in that region were employed in 'picking wheat a great time of the year'. In some estates in the north of the country, there are records of payments for 'divers women' for turf-gathering and for weeding; and tasks such as fetching water and milk, gathering sticks, picking and spreading dung, and doing errands were performed by young brothers and sisters alike. The account of Henry Best, a yeoman in Yorkshire, shows that his 'spreaders of muck and molehills' were for the most part women, boys and girls.

The pace of entry of children to work was gradual. While younger children could assist in various jobs - fetching water and milk, gathering sticks for fuel, bringing food to those working in the fields, or picking dung - the more demanding agricultural tasks were normally not given to children before they reached their early teens. Thomas Shepard remembered that he was put to keep geese when he was no more than three years old; but tending flocks of sheep normally did not start until around the age of 10. Thomas Tryon, Samuel Bownas and William Stout all looked after sheep when they were 10, 11 and 14 respectively.

Ploughing, which required physical strength and an ability to direct the animals properly, was not normally given to youngsters before 11 or 12 years of age. In the harvest, children under 10 or 12 years of age carried food and assisted the binders; but only at about 12 years and upwards did they begin to drive loaded wagons and lead horses, while participation in haymaking was probably delayed until the mid-teens. If they were strong enough for their age, and the family was poor and in great need, a child could be recruited to plough or join the older shepherds as early as the age of nine rather than at ten. But overall, training in the more skilled and demanding tasks normally began when children reached about 10 years.

…It is doubtful that a very young child worked full days or very long hours in weeding or threshing. Nor was it likely that spinning would become a normal routine at the age of seven. Evidence from autobiographies written in the nineteenth century by people who grew up in families who relied on handloom weaving for their living suggests that their entry to work was gradual. At seven they spread cotton to help an older brother who spinned; then they began to wind, and at the age of 10 or 11, to spin. Nor was the winding of bobbins done full-time; it began with assistance to mothers, and alternated with going on errands, fetching water, and taking some time off. This was probably how a Lancashire 10-year-old boy, who testified in the 1630s that his mother had brought him up to spin wool, learnt his craft.

…The pace of entry into most tasks, in agriculture as well as industry, was bound to be adjusted to the physical and mental limitations of the youngsters; so that while child labour was widespread, it did not begin 'as soon as children could walk,' as J.H. Plumb put it many years ago. Nor did it start at a standard age of seven or eight years old. By their mid-teens many children had acquired some agricultural proficiency.”

- Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos, “Early Lives: Separation and Work.” in Adolescence and Youth in Early Modern England

#children#renaissance#georgian#history#farming#adolescence and youth in early modern england#elizabethan#jacobean#caroline era#ilana krausman ben amos

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...During the early part of their training, and sometimes well after, apprentices were required to do a wide range of demeaning tasks: cleaning, carrying, dusting, washing, sweeping, fetching coal, making up fires, and going errands of a variety of sorts. Complaints to the effect that apprentices were required to do household tasks instead of being properly trained in their trade reached the local courts, in London as well as in Bristol. Some youngsters, who were bound at a relatively young age, were employed in going errands for one or two years, and only then began their proper instruction. Overall, meaner tasks were particularly likely to be imposed on the newly arrived youth, whatever his precise age.

Simon Forman remembered that 'being the youngest apprentice of four' in his master's shop in Salisbury, he was put to do 'all the worst', and that 'everyone did triumph over me' - fellow apprentices, and also the kitchen maid, Mary Roberts. That sense of humiliation involved in the age hierarchy of the small shop was also conveyed in Francis Kirkman's account of his life as a London scrivener's apprentice, who was not only required to do the dirtiest and most burdensome tasks, but 'being the youngest apprentice was to be commanded by everyone'.

…In addition, not a few employed two apprentices, and they hired the second apprentice only after seven years, that is, after the previous one had left. Some of these carpenters and joiners probably died relatively young, and others possibly left Bristol after a few years of working there; but not a few among these many woodworkers had only one apprentice in their shop, and so the youngster entered a small shop with only a single master, a stranger with whom he was to begin an intimate routine of hard work. Some smoothing of the process of adjustment to a master and to the routine of the shop could be obtained through a period of trial during which a youngster could evaluate the character of his master and what life as an apprentice entailed.

Edward Coxere, an apprentice on a ship, Richard Davies, apprenticed in Welshpool in Wales, William Stout, apprenticed in Lancaster, and John Coggs, apprenticed to a London printer, all began their apprenticeship with a trial period - to be 'upon liking,' as some called it - of a few weeks. Some youths were able to withdraw from their contracts following a trial period, as the case of Adam Martindale, who returned home to his parents, suggests. But a period of trial was too short to reveal the full extent to which an apprentice could accommodate to his master and the new demands of assistance and work in the shop and the house; a proper alternative, especially for poorer apprentices, was not always available. There was something impractical about this procedure of a trial period, for when the apprenticeship had taken long to arrange, a youth could well find it hard to change his mind.

…Getting on with a new, unfamiliar master, in what immediately became an intimate routine of hard, sometimes humiliating, labour and life, was not devoid of strain and tension. Some masters turned out to be exceptionally brutal, but many more were probably simply difficult, stubborn or hard to please. Still others had burdens and responsibilities of their own, and a few were quite young, not altogether experienced in handling apprentices not much younger than themselves. To all of this, an apprentice, a youth in his mid- or late teens and not infrequently with definite ideas about his apprenticeship, had to adjust. Some youngsters were frustrated in their expectations, like James Fretwell, who in the course of the first weeks of his apprenticeship found out that his master was 'not unkind', but he was still apprehensive about not being 'so thoroughly instructed in my business as I could wish,' as he put it later.

…There was also the mistress of the house. In some towns, such as in Bristol, the wife was an equal party to the contract and her name was entered along with that of her husband in the Register of Apprentices. Even in places where this was not the custom, a mistress would have been in charge of the apprentice as soon as he entered the household. Some autobiographies convey a sense of strain, if not outright animosity, between male apprentices and their mistresses. Richard Oxinden and his fellow apprentices attributed everything that went wrong with their master to his new wife. 'Hee always telld mee that hee liked his master well,' his kinsman wrote in a letter to his parents, 'but his Mistris was somthinge a strange kynde of wooman.' His kinsman also thought that 'moste of London mistrisses ar strange kynde of woomen'.

Edward Barlow also appears to have had greater difficulties with his mistresses than with his masters. When he first came to London he was a servant in the house of his uncle and aunt. While he had little to say about his uncle's character in his autobiography, he recalled that he was displeased with his aunt, for she 'was a woman very hard to please and very mistrustful'. Later on he became apprenticed on a ship, and his recollections also convey the differences between his relations with his master and those with the mistress, with whom he lived in between voyages to the sea.

From the start, his master appeared to him a 'very loving and honest person', and so he remained 'for the most part'. His relations with his mistress, by contrast, were more sour. They scolded each other, had many disputes and 'fallings out' whenever he came back on shore and was required to do household tasks. These accounts remind us that there was someone else besides the master to whom the apprentice had to adjust, and that the relationship with new mistresses could be tenuous. If the master himself was a stranger to the new apprentice, the mistress was not only that, but also a woman, sometimes not much older than the apprentice himself.”

- Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos, “Urban Apprentices: Travel and Adjustments.” in Adolescence and Youth in Early Modern England

#adolescence and youth in early modern england#apprentices#renaissance#history#cities#elizabethan#jacobean#ilana krausman ben amos

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In the course of their teens, most young people gained a range of skills through working as annual servants, seasonal servants and labourers. Annual servants were normally hired to do the least seasonable tasks, mostly in animal husbandry - shepherding, carting - but also ploughing. So the agricultural servants hired between the years 1702 and 1711 by Nicholas Blundell, a landowner in Lancashire, worked as dairy maids, plough-drivers, cowmen and shepherds. When hired as servants for short periods, young people did such seasonal jobs as mowing; and when employed as daily labourers, they did a wide range of mainly seasonal jobs: weeding, threshing, planting and gathering, haymaking, hedging and ditching.

The range of skills required in these employments was diverse, demanding physical strength as well as manual skill, some agricultural knowledge and understanding, and a great deal of responsibility. Some jobs, like threshing, were relatively simple and were done indoors, but they still required skill in handling tools, and the work itself was monotonous and straining. To properly use the flail, for example, took some time to learn. Ploughing required strength, skill in directing the animals properly, in repairing, sharpening and taking care of the plough, and in horse-keeping.

Mowing, shepherding, cattle-herding, hedging and ditching each required its own range of skills. The long-handled scythe demanded both stature and the expertise to swing the scythe in steady movements so as to leave the corn in the least possible disorder. On some large estates, skilled mowers were brought from farther afield, and there were yeomen and gentlemen who were ready to look for good mowers 15 miles and more away.

Some tasks involved in annual service were quite specialised and demanded daily attendance of animals: watering and foddering cattle and horses several times a day, making sure animals were well and safely tied, keeping them in good condition, detecting ailments, applying cures and medications, setting broken legs or bones, bathing and oiling wounds properly. Shepherding entailed a great deal of responsibility in going great distances, making sure no sheep were lost, and guarding the sheep against other animals.

It was lonely work, and demanded independence and endurance; a shepherd had to protect the sheep in winter snows, assist the ewes in lambing, change damaged fold hurdles, wash, grease, and do the dusty and itchy work of shearing. In the late nineteenth century the older shepherd was still considered one of the most skilled and independent persons in a village community.

…Other evidence shows that some time between 16 and 18 years old, young people would have been recruited to do all the jobs done by mature men and women. Adolescents of 13 or 14 were already employed in carting and harrowing, but in haymaking and shearing their productivity was still considered only half that of adults; 'two of us at 13 or 14 being equal to one man shearer,' as William Stout recalled. By mid-teens, however, adolescents could already be considered 'three-quarter-men', as they were referred to in nineteenth-century Suffolk. A description of harvest work at that late date suggests the types of skill adolescents could acquire as they grew up in earlier centuries as well. At 10 and 12 years old, boys and girls assisted only in bringing the food to the fields and in tying the sheaves.

Then they turned 'lads', adolescents between 12 and 17, who began with lighter jobs, such as carting, and by about 16 years old were already considered 'three-quarter-men', doing all the jobs the 'full men' did except lifting the sheaves from the ground to the wagon, the heaviest job of all. A year or two later they were no longer considered 'lads'. Ploughing, too, was normally mastered at 16 or 17 years of age. As we have seen, some adolescents could plough alone by their mid-teens.

A year or two later, having worked as servants, they acquired a great deal of experience in driving two- and four-horse teams properly, and could obtain the reputation of being 'a good plowman', and a 'happen ladder, as Henry Best referred to them. Their wages could then rise substantially. Some time in their late teens servants also learnt to sow and mow, as well as hedge and ditch. In early eighteenth-century Westmorland the magistrates made a distinction between 'inferior servants only fit for husbandry', and older more experienced servants who could 'mow and reap corn, hold the plough, hedge and ditch.

…There must also have been variations depending on the size of agricultural holdings and the responsibilities demanded in them. Large landowners and prosperous graziers had hundreds of cattle and sheep and specialised in products such as mutton and beef for a wide market. On such estates, shepherding involved largescale marketing and management, and the job was given to adults rather than to younger servants. The shepherds of Nathaniel Bacon in Stiffkey, Norfolk, were four mature married men.

Yet on medium-sized and small holdings of husbandmen, clergymen, and rural craftsmen or traders, young unmarried servants could be hired as shepherds, and they were then given charge of small flocks of sheep on their own. In addition to the husbandman or craftsman and his wife, such holdings could include a servant in husbandry, one maidservant in charge of the dairy, and another servant-shepherd.

…Wage assessments from the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries also show that female servants systematically received only a fraction of the wages earned by men. But these divisions were not always rigid. Some young women, for instance, participated in reaping during the harvest in places where the sickle rather than the scythe was used. …Many young women were hired as haymakers, and although the jobs they did differed from those of adolescent males, they still acquired a range of invaluable skills. On the Stiffkey estate, women did not mow or cart, but they participated in weeding, haymaking, shearing, and tying sheaves, planting, picking and gathering.

Domestic servants were also sometimes employed in the hardest and more skilled agricultural tasks. When William Stout's father died, in 1680, his mother hired a female servant to do the hardest house service, and to harrow, hay and shear during the harvest. Women servants did specialised work involving poultry and cows; like their male counterparts, unmarried dairymaids must have gained a great deal of understanding and some responsibilities in animal husbandry.”

- Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos, “The Mobility of Rural Youth.” in Adolescence and Youth in Early Modern England

#renaissance#servants#farming#shepherds#history#georgian#adolescence and youth in early modern england#jacobean#caroline era#restoration#ilana krausman ben amos

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...That young people had a predilection to join or embrace new heresies is to some extent uncontested. Protestantism in its early phase made headway in university circles, and the audience for lectures by young masters were undergraduates, adolescents aged between 14 and 18. Among London apprentices, new religious ideas were probably disseminated with relative ease as well.' But there are difficulties in gauging the precise dimensions and significance of this phenomenon. Conversion to Protestantism was by no means an experience exclusive to the young; some of the leaders and most ardent followers of the early Protestants were in their thirties when they converted to Protestantism.

Moreover, it is impossible to know the precise age structure of either the first generation of Protestants, or any other religious group in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. If we include people in their mid- and late twenties among those described by contemporaries as 'young', it is hardly surprising that the young were the most likely converts to any religious doctrine - what appeared to contemporaries as a predominance of youths among these groups may have been no more than a reflection of the fact that the majority of the population in this period was under 30 years old.

…And despite occasional references to religious meetings designed especially for young people, there is no evidence that there were permanent associations exclusive to the young. Most other accounts of the sermons, preaching and gatherings in which writers of autobiographies took part suggest a lack of age segregation. Piety, religious observation and fraternity based on doctrinal persuasion appear to have transcended age differences and even to have cemented ties with adults rather than with peers and other youths.

…The descriptions of the profanity and sins of the playmates and young companions of these autobiographers accord well with the complaints of moralists, magistrates and clergymen about servants, apprentices and 'idle boys', who 'spen[t] much time in playing', swearing, cursing and disturbing the peace, and who passed their Sundays playing games in the churchyard and disturbing the preachers in their sermons. Patrick Collinson pointed out that preachers also accused ballad-singers of seducing the youth of the parish out of church and into the Sunday dances.

And S.J. Wright has shown that attempts to compel the young to practise their religious duties in the post-Reformation period were dilatory: many people escaped confirmation, and the enforcement of the duties to catechise children and of legislation regarding first communion varied considerably from place to place and over time. People over 14 years of age were required by law to attend morning and evening prayers, but this was enforced haphazardly at best.

Martin Ingram has also shown that the mobility of servants placed great limits on the ability of the church courts to enforce legislation on major sexual offences, such as fornication and bearing illegitimate children. He has established that those guilty of such offences were for the most part young, unmarried, and often in service, and some of them cared little about spiritual courts, sin, damnation or hell. Youth may well have been the stage in the life cycle when official religion had the least impact.

Yet it is doubtful that this in itself fostered the emergence of a youth culture based on distinct religious sentiments or values. Conduct books and books of advice and instruction for the 'pious prentice', 'youth' and 'young men and maidens' were sometimes purchased by adolescents and youths; and while many youngsters consumed chapbooks of romance and adventure, others must have bought the godly chapbooks and ballads that were sung, and listened to, by the young.

Clearly quite a few young men and women, servants and apprentices, did attend church. The evidence on new seating arrangements in parish churches shows some age segregation: young women were separated from their mistresses, and servants stood at the back, but clearly they all did come to church, and the servants stood among adult labourers, rather than being completely separated from the community at large. Some adolescents repeatedly disturbed their fellows at church, but there were apprentices who followed the sermon intently and even took notes.

And while many among the young rejected or avoided confirmation, not a few participated in this formal acceptance into the established church. Some were confirmed when they were in their early teens, but others entered church membership during adolescence and afterwards; that is, when they were older and quite capable of making up their own minds on such matters. It is difficult to know what motivated them; there were the social pressures and dictates of adults or preachers, but attachment to religion may have played its part as well. Moreover, many also took their first communion, and, if they were servants and earned wages on their own, they then began gradually to take up their religious duties, especially the obligation to assist in running parish affairs.

As with adults, it is difficult to know how widespread and with what regularly the young attended church. While some adults went to church regularly with their children, other parents themselves failed to attend. In some places, many of those presented at court for failing to take communion were married men and their wives rather than and, like their younger counterparts, adults sometimes went to church for company; nor did the always listen attentively to sermons on Sunday afternoon.

Still other adults cared little about their servants' whereabouts on Sundays, or were unable to send their children to church. Edward Barlow's father could not provide him with clothes 'fitting to go to the church', so he and his brothers and sister went very irregularly, if at all. Given what we know today about religious attitudes and practices in society in general, there was bound to have been not only leniency towards the young and their predilections, but shared values and beliefs as well.

Although historians differ in their assessment of the degree of piety and religious feeling of the vast majority of the population, the picture that emerges from their analyses is one in which most adults during this period adhered to a range of more or less pious ways, rather than to a strict discipline or deep devotion and religious zeal. A measure of laxity in religious practices, and occasional contempt for or indifference to religion, could be found, too. Despite some differences owing to age or to youthful preference, there was room for basic agreement between young and old in matters touching on religion and the church.”

- Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos, “Spirituality, Leisure, Sexuality: Was There a Youth Culture?” in Adolescence and Youth in Early Modern England

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...To many youths, the nuclear bond was of immense value in their first steps as servants or apprentices outside the parental home, and this bond continued to provide a great deal of assistance in the course of the period of service. We saw in Chapter 2 that parental guidance and advice in deciding what occupation to choose were important, not least because a youth relied on his parents' financial means in arranging some types of apprenticeship. In the case of youths who desired to become apprentices in major towns in the large distributive trades or one of the more lucrative crafts, entry without the financial assistance of parents was unthinkable; not only was the premium for these trades costly, but bonds of high amounts were sometimes required as well.

Even in the smaller crafts and trades, any assistance to cover the costs of at least a part of the premium, or the costs of travel to a large town, could be of critical value. When Edward Barlow became an apprentice in Manchester it was his father who 'made up the bargain'; and about a year later, when he decided to leave for London, he financed his trip partly with his own savings, but partly also with the little money he had been able to obtain from his father. Parents also provided the social contacts necessary for service and apprenticeship, in the countryside as well as in towns.

Although Edward Barlow lived only four miles away from Manchester, where he became an apprentice, and although he had before then been employed outside his home in nearby villages, nevertheless it was his father 'hearing of a man of a reasonably good trade', who provided Edward's initial contacts with his master. Of prime importance in these parental networks were ties based on occupations and on trade. George Bewley's apprenticeship in Dublin was arranged by two people who came from Ireland and lodged at his father's house in Cumberland, and Edward Barlow was also apprenticed, for a short while, with a Kentish vintner who was a guest at his uncle's inn in London."

Inns, ale-houses and local markets and fairs were foci of information networks through which parents found or assisted their sons and daughters in finding a master. Among apprentices in large urban centres, the preponderance of youths who had originally come from market towns was marked. In mid-sixteenth century London about a third of migrant apprentices were from market towns; and in early seventeenth-century Bristol the proportion was even higher, particularly among those who travelled longer distances to the town, among whom nearly half had arrived from market towns.

Urban apprentices tended to come from places and areas that had distinct trading connections with an urban centre: industrial regions in which cloth or metal was produced; coastal trade and coal routes which linked the countryside with large towns; or simply agricultural centres from whence the grain consumed in the town came. Patterns of apprenticeship as recorded in registers of apprenticeship reflect these parental occupational ties too, for nearly half the apprentices in all major industries and trades in a town like Bristol chose masters who had an occupation similar or closely related to that of their fathers.

Networks of adult friendships which extended beyond the village or town where they lived also facilitated the arrangement of service or apprenticeships for daughters and sons. Edward Barlow recalled that his uncle, a London innkeeper, had 'a friend, living in the country.. . who had a son which he was willing to send to London for to be prentice'. Soon after, the youth arrived and was bound an apprentice. As Steve Rappaport has suggested, since so many Londoners were themselves migrants, their links with the countryside are likely to have been strong. Jane Martindale left her home in Lancashire to become a servant in London through contacts she made with Londoners who came to stay with their friends in Lancashire during the plague of 1625.

In large towns themselves, parental links with fellow craftsmen, guildsmen, neighbours and other friends also helped a youth obtain an apprenticeship or a service placement. Bristol's shoemakers, coopers and other craftsmen often sent their sons to become apprentices with other shoemakers or coopers: friends, neighbours and fellow craftsmen of the same guild with whom the parents probably had more than a fleeting acquaintance. Next to parents, the assistance of older brothers or sisters in arranging service or an apprenticeship was often quite important. Sometimes brothers and sisters who had already left home and migrated to a large town assisted their younger brothers or sisters to find lodging or employment, or simply provided advice and first connections in and around a new place.

…Sometimes parents themselves went to visit their daughters or sons. John Gratton mentioned coming back from the field to his grandfather's home where he was apprenticed, 'and finding my father and mother were come over to see us'. Ralph Josselin and his wife both went to see their sons and daughters who served as apprentices and domestics in London, some 40 miles away from where they lived. Even the father of Edward Barlow, who was poor and must have found the trip to London a great financial burden, managed to make the long journey from his home in Lancashire to London, where he met young Barlow, then already an apprentice at sea.

When a master went into the countryside, he might go to see his apprentice's or servant's parents; and many parents, through the same social ties that had enabled them to arrange the service in the first place, were well informed about their sons and daughters. Parents themselves sometimes moved nearer to a son or daughter, and so the contacts with them were resumed; and letters were occasionally sent by parents, brothers, sisters, or their neighbours. For their part, some apprentices who had had to go to more distant towns kept their parents informed by writing letters. Not all youths could write, but among London apprentices, who were likely to be the furthest away from their parents, literacy rates were sometimes quite high.

This does not mean that they all sent letters home regularly, but it indicates that they could write letters if they so desired, or if they were in some sort of need. Richard Norwood wrote his father a very long letter at least once when he was an apprentice at sea; and John Woodhouse, a London apprentice whose parents were dead, wrote his uncle a long letter in which he asked for assistance. By the eighteenth century, manuals of letter-writing contained a substantial number of model letters which were exchanged between youths who were servants and apprentices, and their parents.

Some parents also provided direct financial assistance to their sons and daughters. The evidence on this is very sparse, but what there is suggests that there was nothing unusual about such financial provision. …More important was the assistance parents provided when an apprentice became ill or injured during service. As we have already seen in Chapter 4 and will emphasize shortly, masters were both obliged and expected to take care of their servants and apprentices when they became ill. Nevertheless difficulties could arise, and parents were sometimes called upon to assist. Adolescent illnesses and injuries while at work were common, and recovery was a painfully slow process.

Some masters were too poor and simply could not continue to provide for a youth until he recovered; sometimes the apprentice was incapacitated - soreness of leg, a limb injury, mental illness are mentioned in a number of petitions presented at the local court in Bristol - and it was decided by mutual consent that parents would take upon themselves the responsibility for the recovery of their child. Sometimes there was little hope of recovery, and parents took their sons back; sometimes it was decided that a youth should go back to the countryside to recover; and at other times parents themselves called their sons back, as when plague broke out in the town where their sons were apprenticed.

Occasionally youths themselves appear to have desired to return to the parental home: for example, when they had the smallpox, or when they contracted other diseases which threatened their lives. Benjamin Bangs headed towards his mother's home when he was not well; Ralph Josselin's daughter, Ann, returned home in the midst of her service in London, and shortly afterwards she died and was buried in Earle Colne. Adam Martindale's daughter, Elizabeth, was likewise 'desirous to come home' when she became ill during her service, so she was brought back; but although her parents took great care of her, she died soon afterward.”

- Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos, “The Widening Circle: The Social Ties of Youth.” in Adolescence and Youth in Early Modern England.

#adolescence and youth in early modern england#apprentices#servants#renaissance#history#elizabethan#jacobean#caroline era#restoration#georgian#ilana krausman ben amos

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...The apprenticeship system offered far less opportunities for women than for men. Where systematic evidence is available it shows that women who became apprentices were often a minority; in some places they were a tiny minority, and in others none were apprenticed at all. In London in the period between 1580 and 1640, not a single female apprentice appears in the records of fifteen companies. In Bristol, of about 1,500 apprentices enrolled between 1542 and 1552, only 50 (3.3 per cent) were women, and in the following decade the numbers were similar, 52 (2.8 per cent) out of about 1,800 apprentices registered.

In the seventeenth century the proportions of young women among all apprentices in Bristol remained low - only 43 (2.2 per cent) in a sample of 1,945 apprentices registered between 1600 and 1645. Yet women did become apprentices and were bound by indenture in various crafts, particularly where the market for male labour was less competitive. London was probably the single most attractive town for young men seeking apprenticeship; with a population reaching 200,000 by 1600, young women, as mentioned above, hardly appeared in the records of major companies. Male registrations, by contrast, numbered in the thousands every year.

…No less importantly, there were also variations in the market for male apprenticeships over time, and these had effects on the rate of entry of women into apprenticeships, as well as on the patterns of their recruitment and training. In fifteenth-century London, when population pressures were relatively low, young women found their way into formal apprenticeships with pursers, broiderers, mercers, tailors and silkworkers. In the following century, when the population began to grow and London itself expanded at an unparalleled rate, no women were registered in a wide range of companies.

But in the late seventeenth century a few women reappeared in company records: in the cordwainers company between 1657 and 1700 38 women were registered as apprentices; 14 women appeared as bakers' apprentices; and the turners company bound 9 women between 1671 and 1700 while none had been bound throughout the period from 1604 to 1671. This suggests that in the decades up to the mid-seventeenth century, when the population was growing and London absorbed thousands of male apprentices from all over the country, women were seldom considered for apprenticeships.

However, by the second half of the seventeenth century, when migration pressures eased and the overall numbers of apprentices formally bound dropped, the competition for training in the skilled crafts was less fierce. In addition, the plague of 1665 may well have contributed to a labour shortage - all of which allowed a few women to enter the apprenticed crafts.

…Nor did women altogether differ in their social background from their male counterparts: nearly half of the women apprenticed in Bristol were daughters of craftsmen and artisans engaged in a variety of industries and crafts, from the textile and clothing trades to leather or metal industries. Daughters of merchants, grocers, mercers, barbers, clerks and ship's carpenters could all be found among the women apprenticed in the town. A little less than a fifth were daughters of men involved in mercantile and retail trades, or in some profession; while about a third originated, as did male apprentices, from the landed and agricultural classes. Daughters of gentlemen were particularly prominent, comprising 7 percent of the women.

Among male apprentices, the proportion of gentlemen's sons, in the 1530s, was 3.6 percent. Daughters of yeomen also figured more distinctly among women apprentices than among the apprentice population as a whole, comprising 10 percent of the women, compared with 5.5 percent among men. On the other hand, daughters of husbandmen were somewhat less prominent among the women than were sons of husbandmen among the young men. Finally, a few daughters of labourers could be found among the young women, as was the case among men apprenticed in the town during the 1530.

- Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos, “Women’s Youth: The Autonomous Phase.” in Adolescence and Youth in Early Modern England

#history#apprentices#adolescence and youth in early modern england#renaissance#tudor#elizabethan#jacobean#caroline era#restoration#ilana krausman ben amos

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“On most agricultural holdings, the labour force consisted of two distinct groups: servants and labourers. Kussmaul defined the servant as a person who was hired by the year, lived with his or her master, and was unmarried. A labourer, by contrast, was hired for a shorter period of time, had his own residence, and was for the most part married. Other historians have suggested that this distinction is somewhat rigid, and that patterns of recruitment of servants, especially in the sixteenth and first half of the seventeenth centuries, were less formal than in the century that followed.

There is little evidence of hiring sessions during the sixteenth century, and many servants were hired for short periods of months and weeks rather than for a whole year. On the estate of a gentleman farmer in Stiffkey, Norfolk, servants were rarely hired for twelve months or more. In Romford, Essex, servants were also hired, on occasion, for periods of months rather than a year. A. Hassell Smith suggested a classification of the workforce on the Stiffkey estate into 'resident farm servants', who were hired for weeks, months and above; and 'labourers', who were hired by the day, and were divided into specialist and non-specialist labourers, according to level of skill and type of work they did.

These distinctions between service and labour did not reflect separate age categories. Some farm servants were married adults, and many labourers were youngsters in their teens and early twenties; that is, in the course of their adolescence and youth, young people were likely to move not only from one annual service term to the next, but between different types of labour arrangement; their work as annual servants was interspersed with periods, lasting sometimes many months, during which they were hired for the season or worked as daily labourers.

The detailed research by A. Hassell Smith on Stiffkey families who were employed on the estate of Nathaniel Bacon is illuminating in that it provides evidence on the ages and marital status of many of the employees. Smith has identified a total of 55 Stiffkey sons and daughters employed on the estate between 1582 and 1597. Two were farm servants on the estate, 4 more were employed as a kitchen boy, a cook, and household servants, and the majority (45) were day labourers employed in agriculture and in various crafts, especially woodwork and the building crafts.

The agricultural labourers were nearly all unmarried women, aged 18 years and upwards. The labourers in the building and wood crafts were adolescent males who worked alongside their fathers (carpenters, coopers, painters, masons, tilers, and so on). As Smith suggested, the women might well have been resident servants when they were younger; that is, they were employed as domestics or dairymaids in adjacent parishes when they were in their mid-teens, and returned home to become labourers when they were in their late teens. The males, on the other hand, probably moved on to some form of service or apprenticeship elsewhere after having worked alongside their fathers as day labourers for some time.

In addition, there were resident servants on Bacon's estate who were hired for the season, and they, too, were young and unmarried for the most part. They travelled longer distances, and were hired as mowers, to do the hardest and most skilled job in harvesting. Wage labour was likely to be widespread in the corn-growing areas, where demand for seasonal labour, especially during the harvest, was high. By contrast, annual farm service was more suitable to pastoral farming and areas where livestock husbandry predominated, and where work in tending sheep, horses and other animals was required throughout the year. Moreover, throughout the sixteenth and first half of the seventeenth centuries, annual farm service was in decline, and hiring by the day, the week or the season became common.

Population growth, the surplus of adult labourers, rising prices and lower wages, were more conducive to daily labour or short-term service than to annual farm service. Abundance of labour ensured the farmer a continuing supply of workers, rising prices secured the flow of cash to pay daily and weekly wages, and lower wages also made daily labour a more attractive option." Overall, the incidence of service began to rise only in the century following the 1650s. Contemporaries sometimes made quite clear the advantages of hired labour over the resident servant. When Robert Loder calculated the annual costs of his servants, he remarked in his account book that 'it were best course to keep none'. This was in 1613, in Berkshire, and Loder's farming was based largely on wheat and barley malt.

All this had a number of implications for the working lives of the young. First, young people living with parents and working on the basis of day and week wages, or going out for short terms of a few weeks of residence elsewhere and then returning home with their earnings, were anything but a rarity. In contrast to annual service, where nearly half the wages were paid in kind and the money wage was paid at the end of the annual term or after long intervals of three to six months, short-term hirings and daily labour provided a daily or weekly wage. When they worked as daily labourers or seasonal servants, young people either lived at home or returned to their families at the end of the harvest, and they were likely to contribute to their families at least part of their wage.

Once they passed their mid-teens, their contribution could increase substantially. On the Stiffkey estate, boys working alongside their fathers were paid 2d. and 4d. a day; but adolescents above 15 years old already received 9d., 8d. and 10d. a day, only slightly less than their fathers. This wage was the equivalent of the 8d. standard daily wage earned by the non-specialist labourer who worked in the fields. In the late nineteenth century, wage-earning youth were believed to be independent, self-supporting, and half grown up; their parents were often described as fearful of exercising their authority 'lest the lad should take his earnings and go elsewhere'.

There is no reason to doubt that, given the variation in individual temperaments and families, earning a wage in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries gave young people a similar independence. We have already referred to Edward Barlow who, as a boy, bought clothes for himself with wages he was already earning on his own. When he decided, against his parents' wishes and plans, to leave his village and travel to London, he had already been saving part of his wages from work as a labourer.

Although his father eventually accepted his decision, and even gave him some money, this only complemented the money young Barlow had saved towards his long journey to the capital. Working intermittently as labourers and moving between different types of service arrangement also confronted the adolescent with the burdens involved in having to subsist on irregular work and a variety of makeshifts, and, among the poorer sections of society, having to survive near or on the verge of subsistence.

Joseph Mayett was forced to trick his master into taking him back as a resident servant, having been released from service and forced to subsist, during three months in the famine winter of 1800, on work as a labourer and on a very poor diet. Such an existence fostered flexibility in adjusting to several types of work, in eking out a living by alternating between assistance to parents at home, casual day labouring, and farm service. It also necessitated the acquisition of a wide range of skills, some of them quite specialised. Often it involved migration into areas and villages where opportunties for industrial employment and craft apprenticeships were available as well.”

- Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos, “The Mobility of Rural Youth.” in Adolescence and Youth in Early Modern England

#servants#farming#economy#adolescence and youth in early modern england#history#renaissance#jacobean#caroline era#georgian#ilana krausman ben amos

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...In the course of their early lives, many children were placed outside their parental home and thus forced to part from their parents. The duration of these separations could vary between a couple of days or weeks and a number of years. About a quarter of the autobiographers mention some form of boarding out during their early and late childhood before they departed for service or the university.

The experience of Simonds D'Ewes, who, until the age of 16, was separated from his parents five times for periods totaling no less than twelve years, was to some extent unusual but not altogether unique, both among children of a similar social background - D’Ewes's father was a wealthy lawyer - as well as among those less well off. Thomas Shepard, the son of a small grocer in Towcester, Northamptonshire, was sent away to live with his grandparents when he was three years old, and after a couple of weeks he was placed with his uncle. Following his return to his parents, he was again boarded out for three years, between the ages of six and nine.

Oliver Sansom, the son of a trader, was placed with his aunt between the ages of seven and ten, while Mary Rich, a gentleman's daughter, boarded with a gentlewoman from the age of three until she was eleven years old. John Whitting, Anthony Wood, Frances Dodshon, James Fretwell, Edward Coxere, Edward Terril, Simon Forman, Joseph Oxley, Phineas Pett, George Bewley and William Johnson all spent one, two, three or four years away from their parental homes, at least once, in their childhood, before they reached their mid-teens and, in the case of males, before they began a career as university students or apprentices.

The reasons for these early separations between children and their parents varied greatly. Among autobiographers, the most common reason given was the schooling of children. As is by now well known, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries witnessed a substantial increase in the number of schools available for elementary and higher education. Some schools, such as Eton and Winchester, were well-established institutions designed for the preparation of sons of the aristocracy for a career at Oxford or Cambridge; others among the great endowed grammar schools which had also gained in reputation became more fashionable among gentry and yeomen families.

In most cases, sending a son to a prestigious school dictated boarding him away. The practice of 'tabling out' in towns was already well established in the sixteenth century, and the few dozens of major endowed grammar schools must have included substantial numbers of students who came from far away and who were tabled out during their studies, at times for quite substantial amounts of money. But even when a child was not sent to a particularly prestigious school, he was often boarded away from home for the purpose of schooling, and at times at a very young age.

The most common reason for boarding one's son during his school years was the sheer distance of schools, any school, from one's home. The increase in the number of schools spread such institutions geographically, so that most market towns and many rural parishes had a school and only a small proportion of the rural population had no access to any kind of schooling. Nonetheless, even if this meant that there was a school approximately every twelve miles, many parents would still have found this distance too great, and would have boarded their children nearer to school. In large towns, and especially in the rapidly expanding capital, going to school might still require boarding out if the school was not located within walking distance of home.

…Finally, since the single largest category of schools was that of the feepaying unendowed schools, some parents found the local school simply too expensive and were forced to seek an alternative arrangement. Scattered around the country were women and schooldames who taught, without licence, reading and basic literacy, and as some autobiographies suggest, these women could offer boarding to sons of relatives and kin.

…Outbreaks of plague could also bring parents to send their children away. In 1610 a plague broke out in Towcester, where Thomas Sheppard's parents lived, and young Thomas, who was three years old, was sent away the same day the plague broke out to live with his grandfather and grandmother in a remote place in the countryside. Later on he was placed with his uncle, and returned home only when the plague disappeared from Towcester.

…While wealthier families could afford to travel and escape the disaster together, among poorer families separations of parents and children during times of plague must have been common. Plague occurred frequently, and its impact was often random, striking one community disastrously and avoiding another. Since most people recognized this randomness, sending one's child away, even only a few miles to another village, might have been a reasonable strategy; it could save a child from being infected. Moreover, the disease spread slowly and over a long period, so parents could be aware of the approaching danger the moment it arrived in a nearby parish or town, and react to protect their children.