#ignore me using the wrong orthography in several places

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

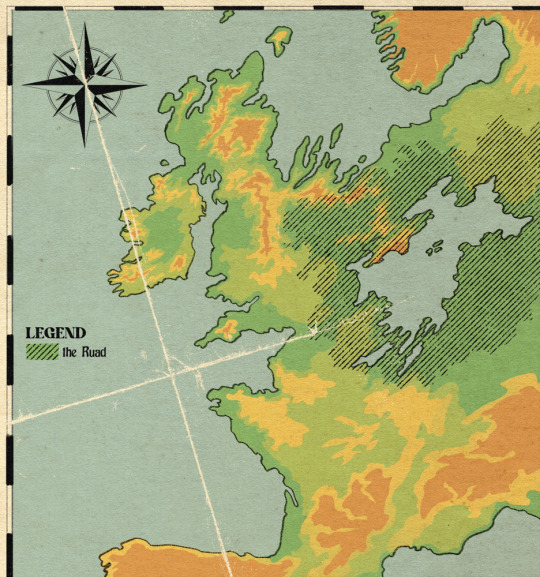

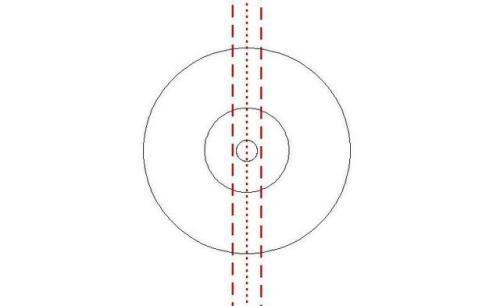

Inver - relief map relative to the continent with otherworld territory marked, broad habitat map, detailed local landmarks map, and political map of the northeast atlantic peninsula as of 1862

i was just having map fun for two days lol. i make habitat maps a lot already but the difference with this one is that i can't just download a handy shapefile and do some GIS magic. this was hand drawn (but obviously. somewhat traced over the actual irl map)

for the outline of the north sea coast i used bathymetry data to figure out where the true coastline would occur. the north sea recedes but the atlantic doesn't (to the same extent). because this landmass was formed through some ancient Event, i felt pretty okay about changing the bedrock because like, whatever, we can't be fully realist all the time. so the northern half of inver is mainly limestone, the southern half is silicaceous - so we got the bog/marl divide there, though lough cánamac (in volume slightly larger than any of the north american great lakes) appears to be the remnant of the north sea, it is freshwater with a relatively low pH. the water of the lough is black to dark brown due to the run-off from the southern bogs and swamps.

in the north, the mountain ranges are calcareous. calcareous grassland, scrubland, heaths and fens dominate with a largely alkaline profile. limestone marl lakes which regularly flood due to groundwater input make the region pretty unsuitable for crops other than rice.

the ruad is the name for a stretch of otherworld territory which contains the lough, though generally used to refer to the forested area. it is completely uninhabitable throughout the majority of its range due to the non-euclidian structure of the land making it impossible to navigate consistently, and the strange and frequently hostile creatures living there. the ruad is faery territory and belongs to an entity known as the Red King, who uses the symbol of a stag. so although inver may look like a large country compared to its neighbours, it has a relatively small population concentrated on the west coast.

however, sailing across the lough is the quickest way to trade with countries in the east, far quicker than trekking through the forest and over land. the trade route through the ruad from invergorken to the cánamac town is one of the most valuable in the continent. it consists of an old road with regularly-spaced ranger safehouses and patrols, and a newer pair of railway lines which can cut through the supernatural aura of the ruad due to their iron rails. the first and older line is no longer in regular use. it was constructed before the development of wrought iron and before the build crews learned how to blast through rock, so it takes a very slow and winding route and required a lot of maintenance. safehouses were constructed to board the workers while the tracks were laid. but without this original track, the construction of the second, far more advanced wrought iron track would have been impossible. workers for the second track were able to commute and sleep on the first track's train, keeping them from harm. the second track can fit two trains side by side and is in constant use ferrying cargo and passengers between the two towns

the country of inver, once The Event wiped out all of its original inhabitants a couple thousand years ago, was settled by hibernians and vikings from the north moving south, and aquitanians from the south moving north (thus the place names). the ruad mostly blocked incursions from the east. there was a long history of dispute over who truly owned the land, and that remained sort of up in the air for most of its history until the 1400s when armorican warlords (like Olivier) decided to make it theirs for realsies and waged war against their old hibernian trade partners (like Finbarr) for control of the land. the hibernians lost because finbarr fucked it up at the last second, and this cemented a ruling class of werewolves in inver until the 1860s

inver consists of three large duchies which cover 70% of the population. Moya in the west is the heart of lycanthrope rule, everybody worships a faery known as the immortal hound and the ruad is far enough away that it is not a fact of life as it is for everyone else. Inver duchy covers the capital city and the south-western farmland, the main sites of production in the country. And Cánamac duchy covers the trade port in the lough and surrounding territories, where forest clearing has led to new farmland and a thriving population. There was a fourth duchy in the north, Aber, but it was historically somewhat isolated and cut off from the south of the country and had developed its own customs and traditions, and its own form of the country's currency. In the 1840s, the duchy of Aber was dissolved and reconstituted into the king's lands, and southern customs were enforced in the north to prevent any more divergence. the palaces of the ruling families in each territory are shown in the local map alongside the family names.

Due to The Event causing massive damage in this region of Europe, forbidding the development of britain and france etc as colonial empires, the last great Empire of this continent was the roman empire, and even that didn't manage to overcome the Ruad. technology is rudimentary in Inver and the people living there are largely considered to be weird backwards superstitious barbarians. aquitan has been threatening annexation for decades, led mainly by the church of suzette, which forbids interaction with otherworld entities. the church holds in disregard the nobility of inver and their cultish ways, and as a result has been banned from attempting to convert inver citizens. but the church is still allowed to make minor inroads into inver for one very important reason: penicillin and antibiotics are the sole creation of the church, and the secret of how they are made is unknown outside suzette. so for the sake of good, advanced healthcare, the church is allowed to set up clinics and hospitals, on the condition that nobody is converted, and members of the church are strictly banned from engaging in any business but importing and selling antibiotics

#ignore me using the wrong orthography in several places#setting: inver#northeast atlantic peninsula bro what happened to u... oh no.. he died...#none of that is spoilers under the cut it's just like. basic history everyone knows

532 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 5: an Introduction to the Fifth Book of the Nampō Roku, Daisu [臺子] ; and an Apologia that Explains the Way this Book Will Be Interpreted.

I. The historical -- and modern-day -- importance of the daisu.

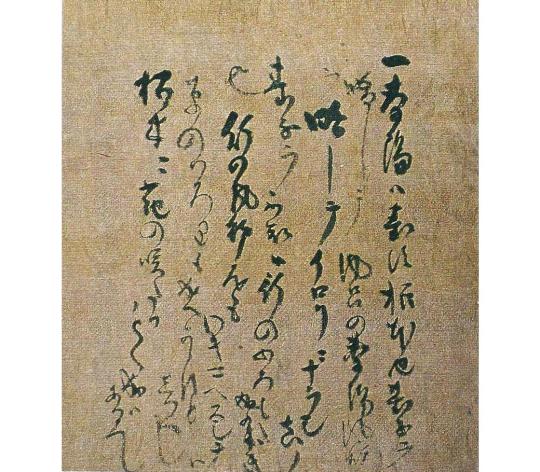

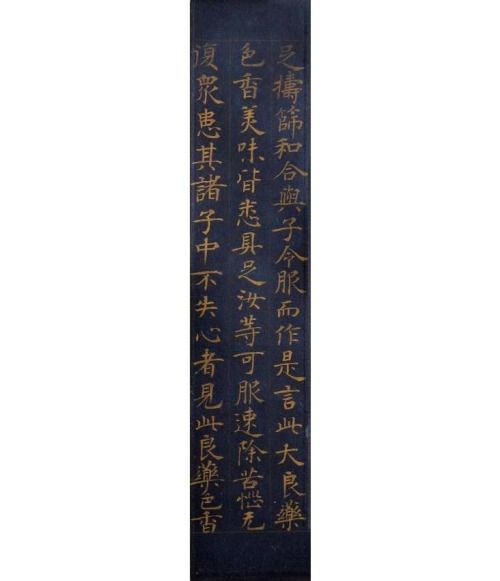

At the beginning of the densho known as the Tenshō ku-nen ki-mei densho [天正九年記銘傳書]¹, Rikyū wrote: “with respect to chanoyu, the daisu is its root. When the daisu is abbreviated, [it becomes] chanoyu with the furo. When the furo is abbreviated, it becomes [chanoyu with] the irori. If the ‘shin’ [眞] of the daisu is not understood, then [the correct way to use] the furo is difficult to do successfully; [and] if one can not discern [what is meant by] the ‘gyō’ [行] of the furo, then the ‘sō’ [草] of the irori is also impossible to bring forth, so you must understand. It should be like the flower, which blooms [upward] from its root².”

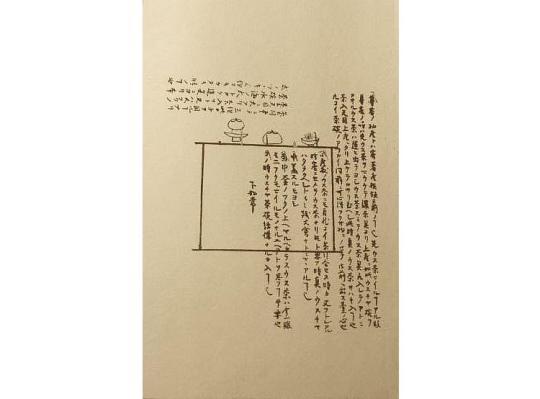

[Rikyū’s original manuscript of the passage that has been quoted in the text. ]

Rikyū, here, declares the essential nature of the daisu, not only from a historical perspective, but also with respect to its impact on the everyday temae. The “daisu” to which he refers means the collection of classical temae handed down from ancient times, that have been preserved in this book³, and to the idea of kane-wari [カネワリ]⁴ that was derived from them.

II. The format of Book Five.

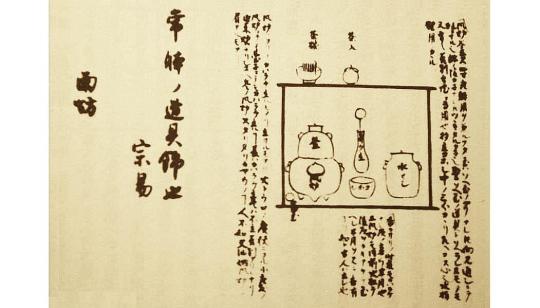

The contents of Book Five of the Nampō Roku largely consist of a series of sketches (each drawn on a separate sheet of paper), that apparently were given to Nambō Sōkei by Jōō⁵; with kaki-ire added to many of them at a later date⁶. Each entry (several of which extend across two, or even three, double pages) closes with a title, followed by Rikyū’s “Sōeki kaō” [花押]⁷, and then Nambō Sōkei’s name (“Nambō” seems to have been Rikyū’s nickname for Sōkei)⁸, as seen in the example shown below.

[The double page showing the first sketch, from the Enkaku-ji manuscript. The components are explained in the text.]

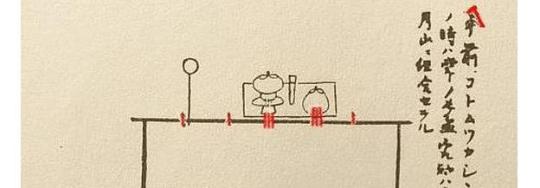

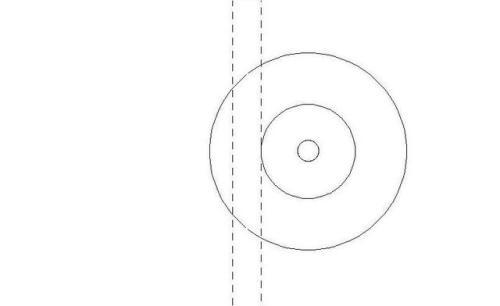

Many of the sketches are marked to indicate the relationship of the various objects to their kane, as may be seen in the example below. A single line means that the utensil in question is associated with a kane, but is not centered on it; three lines, however, indicate a mine-sure [峰摺り], where the object is carefully centered on the kane⁹.

[A detail of the san-shu gokushin (三種極眞) arrangement, showing the way that the mine-suri (峰摺り) are indicated.]

In this translation, all of the pages related to a single topic will be covered together in the same post. As will several other arrangements that have been lost from the Enkaku-ji manuscript, in their appropriate places (relative to Jitsuzan’s original version of the material).

The final 15 text entries will be segregated into several groups, based on their content.

III. An apologia regarding the shiki-shi [敷き紙], and the interpretation of kane-wari that will be used in this translation.

As I have mentioned before, Book Five really lays the foundation for kane-wari. Yet, if someone is ignorant of the shiki-shi, then the conclusions that they will draw are, put simply, wrong.

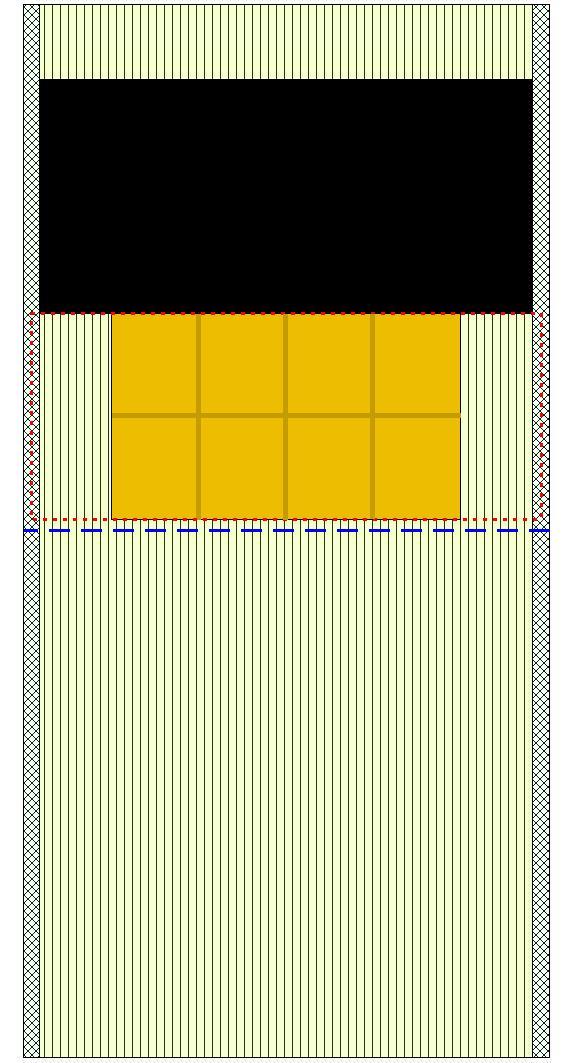

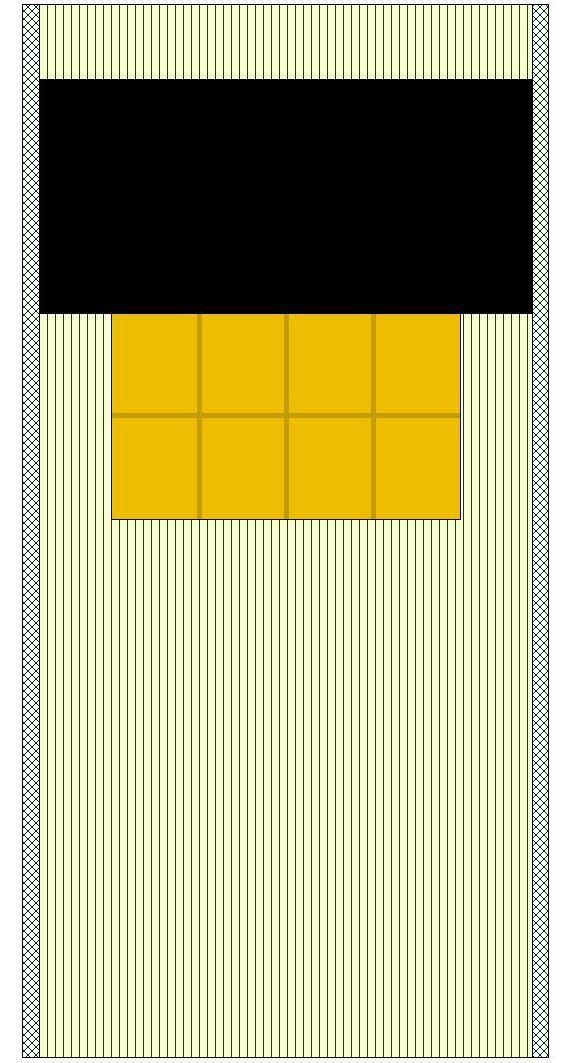

[The shiki-shi (敷き紙): one side is gilded, while the other is silvered. The fully opened shiki-shi determined the temae-za in front of the daisu (top), while the half-opened shiki-shi determined the temae-za in the small room (middle). The fully folded shiki-shi (bottom) measures 6-sun by 5-sun, which is a convenient size to be inserted into the futokoro.]

A textually unidentified sketch of the shiki-shi is included in Book Five, as entry 48. This is followed by two sketches showing the shelves of the daisu divided by the kane -- first (entry 49) the small daisu, which is divided by seven kane, and then the large daisu (entry 50), divided by the eleven kane (five yang-kane, interspersed with six yin-kane). While the sketches in entries 49 and 50 are clearly proportional to the dimensions of the ten- and ji-ita of the daisu in question¹⁰, that of entry 48 (which I suggest is the shiki-shi) is obviously not. Below is Jitsuzan’s sketch, on the left, and the modified sketch from Shibayama Fugen’s commentary (Fugen deliberately stretched this sketch horizontally, so that it conforms with the dimensions of the daisu). The five marks were added to the upper edge later -- whether by Jitsuzan, or by one of the other scholars affiliated with the Enkaku-ji, once it was decided that (contrary to the visual evidence¹¹) this was a sketch of the subdivision of the ten- or ji-ita of the daisu.

[On the left is the sketch from Tachibana Jitsuzan’s manuscript, while on the right is Shibayama Fugen’s version -- which he modified to conform with the dimensions of the ten- and ji-ita of the shin-daisu.]

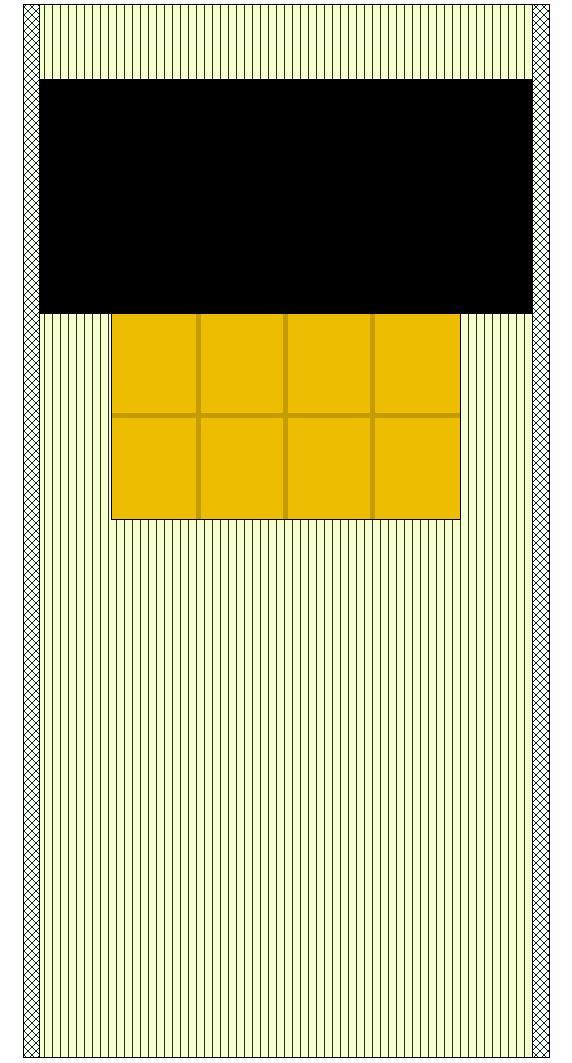

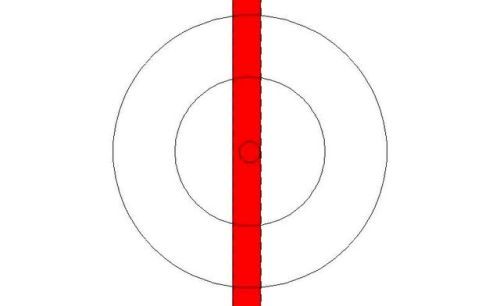

Here the shiki-shi is shown arranged in front of the large shin-daisu, on a kyōma tatami.

[This sketch carefully replicates the shiki-shi arranged in front of the shin-daisu on a kyōma tatami.]

The kyōma tatami (which measures 6-shaku 3-sun by 3-shaku 1-sun 5-bu) has a fraction more than 61-me between the heri (the width of the space between the heri is determined by the width of the shin-daisu, which is 2-shaku 9-sun 5-bu; the heri are always 1-sun wide), with the heri aligned with the edge of the first me on the side of the mat towards the guests’ seats -- in this case, on the right. Note that on that side the shiki-shi exactly matches the edge of the me, and that there are 9-me between the shiki-shi and the heri. Though the spacing is the same on the left, because the me do not exactly match the width of the mat, the left edge of the shiki-shi does not match the edge of the me on that side¹².

Because of the folds, the temae-za (which is determined by the shiki-shi) extends onto the two heri, as shown below, so that the uncovered spaces on the left and the right are equal to the panels of the shiki-shi itself.

[The temae-za is outlined with the dashed red line; the middle of the mat is shown by the dashed blue line.)

Meanwhile, the space between the front of the daisu and the middle of the mat was determined by the largest of the six meibutsu trays (which measures 1-shaku 3-sun in diameter). The space on the far side of the daisu is simply what remains, without any special reason.

Further discussion of these points will be put off until the commentary appended to the entries with which it is relevant (since Tumblr’s new format appears to be limiting the length of posts once again).

This introduction will be followed by an Appendix, wherein I will review Rikyū‘s own teachings on the use and arrangement of the daisu, from his densho.

_________________________

¹The person to whom this document was presented is unknown. It is believed that this version of the text was retrieved from Rikyū's personal archives, since similar densho (addressed to specific individuals) are known. It would appear that writing in Japanese was difficult for him, on account of his language dyslexia. Thus he wrote out a master copy of his densho, which he kept among his papers, making copies of them for presentation* (with situation-specific modifications) whenever these were needed.

Tenshō ku-nen [天正九年] was 1581. Consequently this densho was written at a time when Rikyū was moving in the higher circles of society, but before he was inducted into an official position within the government. __________ *One such surviving example of this particular densho was addressed to Nomura Sōkaku [野村宗覺; his dates of birth and death are not known], a machi-shū chajin from Sakai. His version of this densho was also dated 1581 in Rikyū's dedication.

²Hitotsu, chanoyu ha daisu nemoto nari, daisu wo ryakushite furo no chanoyu, furo wo ryakushite irori ni narashi, shin no daisu wo fu-chi ha gyō no furo mo nari-gataki nari, gyō no furo wo mo wakimaezu-shite ha, sō no irori mo nasu-bekarazu to shiru-beshi, nemoto ni hana no zakitaru gotoku nari ha shiru-beshi [一、茶湯ハ臺須根本也、臺子ヲ略しテ風呂ノ茶湯、風炉ヲ略しテイロリニナラシ、眞ノ臺子ヲ不知ハ行の���ろも成可たき也、行のふろをもワキマヘスしテハ、草のいろ里も成ヘ可ら須と知るへし、根本ニ花の咲たるコとく成ハ知るへし].

The orthography of this passage is discussed in the post entitled Rikyū Densho — the Private Writings of Sen no Rikyū: IIIa. The Tenshō Ku-nen Densho (A. The Daisu is the Root of Chanoyu).

The URl for that post is:https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/83456005982/riky%C5%AB-densho-the-private-writings-of-sen-no

³Though several of the arrangements illustrated in Book Five of the Nampō Roku have been appropriated by the modern schools, it must be understood that the original temae were very different from anything that the modern schools have conceived, or teach.

The classical temae was always essentially the same*. The way to fold the fukusa† -- which is one of the defining elements of the secret aspects of the modern “higher temae” (including those that employ the daisu), did not exist in ancient times: Rikyū was the first to fold the fukusa in the room, at the very beginning of the temae and before the eyes of the guests, and he did this in the most perfunctory manner possible. Prior to that, the fukusa was folded in the katte, at a time that the host deemed appropriate, and kept in the futokoro of his kimono. The fukusa was taken out for use, and then returned to the futokoro. It was never refolded, and discarded into the left sleeve at the end of the temae. __________ *There were two possible formats, depending on whether the host removed the shifuku from the chaire first, or whether he did this while the chawan was being warmed with hot water prior to the chasen-tōshi.

The decision turned on the importance (i.e., social rank) of the shōkyaku.

†The so-called shi-hō-sabaki / yo-hō-sabaki [四方捌き] ultimately derived from Sōtan's peculiar way of doing things, though in this case it was an attempt to discourage the government's interest by feigning incompetence: traditionally the fukusa was held with the wa-sa [輪差], the folded edge, on the right, before folding it diagonally into a triangle; Sōtan pretended that he could not even find the wa-sa, fumbling with the fukusa before “folding” it. His sons later “refined” this action into the shi-hō-sabaki. Consequently, any temae that features the shi-hō-sabaki -- or, indeed, includes the folding of the fukusa in the tearoom, in front of the guests -- could not be earlier than the chajin who initiated these practices.

⁴Kane-wari [カネワリ = 矩割り or 曲尺割り] is the system of subdividing the spaces used for chanoyu with five “lines.” While the original purpose was apparently intended as an aid to reproducing the arrangements elsewhere, this idea was also associated with balancing the “energy” of the system, so as to enhance the beneficial properties of the tea* that was prepared during the temae. __________ *According to the usual interpretation of the passage in the Medicine King Chapterᵃ of the Lotus Sūtra on which the idea of chanoyu was originally based, drinking tea cures the person who drinks it from the disease of saṃsāraᵇ.

As chanoyu came to be understood as an exercise in motion-meditationᶜ, furthermore, the impact of the environment will either enhance or impede the attainment and prolongation of samadhi, hence the energy generated by the arrangement of objects was considered to be of critical importance. __________ ᵃThis is usually chapter 22 or 23 in this sūtra, depending on how it has been subdivided.

ᵇThe relevant passage was translated and discussed in the post entitled Some Random Thoughts on the Practice of Chanoyu (3): the Origin of the Use of Tea as a Pious Device is Said to be Based on the Saddharmapuṇḍarīka Sūtra [the Lotus Sūtra].

The URL for that post is:

http://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/126804725203/some-random-thoughts-on-the-practice-of-chanoyu

ᶜThere was probably a certain degree of temporal separation between the association of tea with the “medicine with a beautiful color, wonderful aroma, and delicious flavor” of the Lotus Sūtra (this seems to have been the farthest the evolution progressed in China), and the recognition that the ritualistic method of preparation could, itself, be utilized as a pious device that would aid in the cultivation of samadhi (which appears to have arisen in Korea, possibly at the Ssang-gye-sa [雙溪寺] or one of the other temples standing near the site of the first tea fields, at Hadong).

⁵The sketches, on kiri-kami [切紙] (individual pieces of paper, rather than drawn on a long scroll of paper, or in a notebook), are executed in the same style, and observe the same conventions, as those found at the end of Book Three and Book Four.

The fact that Rikyū verified the contents of each sketch with his signature clearly indicates that (contrary to the assertion of certain scholars) the sketches did not originate with him.

Nor is there any reason to suppose that Nambō Sōkei was responsible for them, since Sōkei was a collector of antique teachings, rather than an innovator or creator of arrangements.

⁶The fact that the sketches document usages that were employed up to a century before Jōō‘s birth* shows that these arrangements could not have been created by Jōō. Rather, it would appear that he collected them from various sources, and passed the collection on to Nambō Sōkei, perhaps during his final illness.

Furthermore, since a number of the kaki-ire [書入]† were written over the original sketches indicates that they must post-date both the original sketches, and Jitsuzan’s copies (since if this material had been present when he produced his copies, he would surely have allowed sufficient space for the comments).

This example shows the extent to which the kaki-ire occasionally obscure the sketches themselves, as well as being added in an odd way (the kaki-ire above the chaire and dai-temmoku was written with the paper turned sideways).

The above example is also important for another reason: this sketch (like several others) is not found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript of the Nampō Roku. Kanshū o-shō sama explained to me that, unfortunately, it seems certain people tore out pages as “souvenirs” in the past‡. The absence of these drawings in the Tankōsha edition of the Nampō Roku indicates that this was done prior to the 1950s, when the Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shu [茶道古典全集] was originally published. (It is interesting that Kanshū left me alone with the books on several occasions.) ___________ *The earliest datable of the sketches is the one illustrating the setup for the san-shu gokushin [三種極眞] temae, which (according to Book Six) was first performed publicly (in Japan) on the 18th day of the Sixth Month of Ōei 10 [應永 十年] (July 7, 1403). The performance shocked and awed the onlookers, who were members of the shōgunal court (as well as anyone who was able to peep in from outside), who had never seen anything of the like (which indicates that chanoyu was completely imported, rather than a locally evolved practice). What is also interesting is that the san-shu gokushin was a modified version of the gokushin temae (devised to allow for the use of a special celadon mizusashi), suggesting that the original of the original form was created much earlier (in Korea -- the appearance of chanoyu in Japan occurred shortly after the assassination of the last Koryeo king earlier the same year, following his forced abdication during the previous year).

†The language used in the kaki-ire in Book Five is identical to that used in the kaki-ire that were added to the sketches in Book Four -- which, Tanaka Senshō noted, his sources (among the group of scholars who gathered in the Enkaku-ji to study this document) revealed were known to have been added to the sketches during the second half of the Edo period, after Jitsuzan presented his manuscript to the Enkaku-ji. As a result, to then argue that the kaki-ire found in Book Five were approved by Rikyū is nonsense.

This is an important point, because many of the assertions bandied about regarding the teachings of the Nampō Roku -- and what they supposedly “reveal” about Rikyū’s “secret teachings” -- derive from these kaki-ire. (This is significant because some of these assertions directly contradict things found in Rikyū‘s own densho -- and this constitutes the “proof“ that the densho are spurious! In fact, what some of these kaki-ire actually reveal is that the group of scholars did not have a clue, and simply put their own speculations into Rikyū’s mouth.)

‡There was a certain vogue for mounting such fragments as kakemono during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

One of the maru-bon midare-kazari [丸盆亂飾] sketches still survives as a torn page. Alas, the remaining fragment is too small to enable us to reconstruct the missing content.

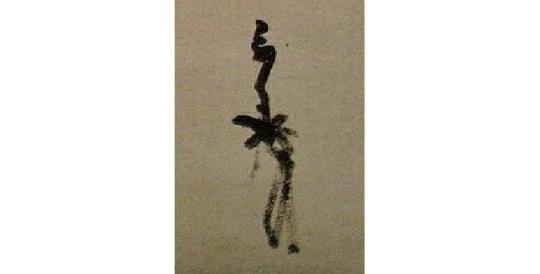

⁷A kaō [花押] is a stylized signature, added to a document as a seal. In this case, Rikyū’s kao certifies that he had reviewed the document, and supposedly verified its contents. A copy of Rikyū’s actual kaō is shown below.

Naturally, since the Nampō Roku consists of Tachibana Jitsuzan’s copies of the original documents, he chose to simply write “Sōeki” [宗易]*, rather than forge the actual kaō.

The appearance of this kaō -- and the reason for its appearance -- is problematic, because it appears to sanction the kaki-ire (which, of course, would have been impossible, since these were all added during the Edo period). This is one reason for much of the confusion that surrounds the contents of this book. ___________ *Sōeki [宗易] was the name that Rikyū was given when he “graduated” from his period of training (something in which most of the male population of Sakai participated during that period). He used this as his professional name thereafter (another common convention of the period).

⁸Nambō was apparently intended to indicate the recipient, in the same way that a letter concluded with the name of the person to whom it was addressed.

It is impossible to know when Rikyū reviewed documents (since the entries are undated). However, the introduction to the Nambō-ate no densho [南坊宛の傳書] mentions a previous correspondence between Rikyū and Sōkei, and it is entirely possible that Sōkei had submitted these sketches to Rikyū for his comments, and Rikyū’s reply sufficiently impressed Sōkei that he submitted additional questions that were answered in the above-mentioned densho.

Subsequent to the Nambō-ate no densho, Rikyū addressed two further documents of the sort to Sōkei. Though undated, the first of those (which may be referred to as the Tsuri-dana no densho [釣棚の傳書] -- both are usually included in modern versions of the Nambō-ate no densho without comment) must have been presented in 1582 or 1583 (since the tsuri-dana was created in the summer of 1582), while the second (Shin no dai temmoku, onaji daisu no koto no densho [眞の臺天目、同臺子の事の傳書]) was written around 1586, perhaps just prior to Hideyoshi’s prohibition on the unauthorized dissemination of information related to the gokushin temae. The text of the latter will be appended to this post, since it will give the reader a better idea of Rikyū’s teachings on the subject of the gokushin daisu temae.

⁹The different kinds of associations with the kane were discussed in an appendix to the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 3 (18.5): Arrangements for a Meibutsu Futaoki, and for a Karamono Chaire.

Put simply, ordinary objects are associated with their kane by placing them so that their foot is immediately to one side of the kane. This is shown, in the Nampō Roku, by the kane located to one side of the object.

Important objects (usually meibutsu pieces) are aligned so that their center is located within the 3-bu wide space of one of the inner three kane (this 3-bu wide space is a consequence of the shiki-shi). This is shown in the Nampō Roku by the object being centered on a single line.

Mine-suri [峰摺り] objects, pieces of the highest rank (usually when being used to serve tea to an extremely important -- high ranking -- shōkyaku) are exactly centered on the 3-bu wide space. This is indicated by the object resting on three lines (the outer two indicate the edges of the 3-bu wide space, while the inner line shows the object aligned with the center of that space).

For additional information, please consult the post mentioned above. The URL is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/187172815712/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-3-185-arrangements-for-a

¹⁰In the Enkaku-ji version of the Nampō Roku, the quality of Jitsuzan's drafsmanship cannot be surpassed. Everything is drawn so carefully, that the intentions of each arrangement can be understood at a glance. Unfortunately, this is not true with any of the published editions, which use either re-drawn sketches, or sketches that were not reproduced carefully (so that they are usually more confusing than helpful).

The dimensions of the sketch of the shiki-shi in the Enkaku-ji manuscript exactly matches the actual shiki-shi; while the other two exactly match the two daisu. Consequently, it is impossible to conclude that the first was intended to show a daisu -- though Jitsuzan himself may not have been aware of this (he seems to have made careful copies of everything -- even when he did not understand what he was drawing).

¹¹This argument is really indefensible: in addition to the anomalous dimensions of the sketch, nowhere else in the Nampō Roku is this division of the daisu into eight sectors mentioned, and it adds another (and irrelevant) note of confusion into the subject of kane-wari.

Precisely why the scholars in question could not trust their eyes is at least partly a consequence of a sort of mentality that developed during the Edo period, as a consequence of “artistic purity” being held out as a goal. Because the shiki-shi was used by practitioners of incense, it could not possibly have any connection with chanoyu. Even though there is no other object that conforms to the sketches the way the shiki-shi does.

We must remember that, even in Rikyū's period (as well as in the decades before), none of these arts were truly distinct, the way they became in the Edo period. Rikyū practiced chanoyu, certainly, but he was also a skilled floral artist. And also well versed in incense. Jōō was as much a classically trained poet as he was a devotee of incense, and, only later, one of chanoyu. This sort of mindset was hardly unique to Japan. Indeed, it appears that this was also exactly the case on the continent, and describes the environment in which all of these arts evolved -- together.

How I came to identify the shiki-shi from the sketch is the result of circumstances to which I was exposed long before I ever went to Japan. A friend of mine had spent a year in Japan with her husband and children; and because her husband was a famous researcher, when they returned to the USA they were showered with all sorts of presents. One of the things that she was gifted was an antique shiki-shi (one that could never be used for chanoyu, since it had delicate watercolor paintings on both sides that would have dissolved at the slightest trace of water -- indeed, there is no evidence that the shiki-shi was ever used for chanoyu in Japan). One day she put her shiki-shi in front of the naga-ita on which her tea utensils were arranged, as a decoration (her level of chanoyu training was sub-basic -- at that point she could not even do the ryaku-bon temae -- and she had had only one experience of participating in an incense gathering; still she had seen the shiki-shi spread out in front of the kō-dana [香棚], and decided to do that in her own home.) This, and the unique shape of the object, stuck in the back of my mind somewhere; and when I first saw the sketch that is entry 48 in the Nampō Roku, the shiki-shi immediately came to mind (this was before I was able to read the text at all).

Serendipitous, perhaps. But I have found no other way to explain kane-wari -- especially the difference between this apparent system, and what Rikyū taught: while the shiki-shi seems to form the basis of the daisu arrangements (when objects are placed on the large trays, the trays always align the objects with the position they would have occupied on the shiki-shi), Rikyū's system reduced the three inner kane to simple lines, thus pulling the temae-za inward from the heri, so that it ends at the heri, rather than rising onto them on either side. And, as if to prove this true, when the large trays are moved inward, the objects placed on them then correspond with Rikyū's system.

More will be said about this later, in the commentary appended to the individual arrangements.

¹²To create the illustration, the dimensions of each of the elements were fixed separately, and then they were simply super-imposed on top of each other. Nothing was adjusted to fit afterward. In the absence of an actual kyōma tatami, this was the best evidence that I could give for the credibility of the assertion that kane-wari is based on the shiki-shi.

In a setting where the guests are seated on the host’s left, the orientation of the utensil mat will be reversed -- as shown below.

To understand this, the reader should look carefully at the me.

2 notes

·

View notes