#i was going to expand on the bird metaphor initially but then I remembered that Arsay doesnt really do that. she just says shit

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

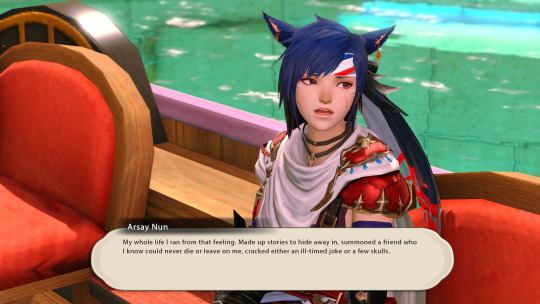

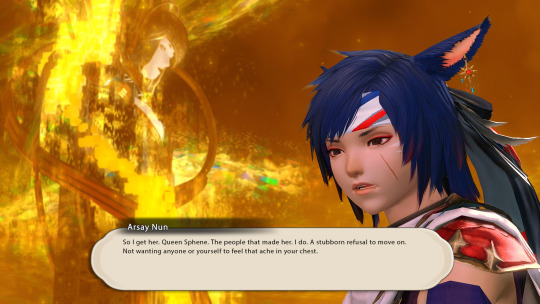

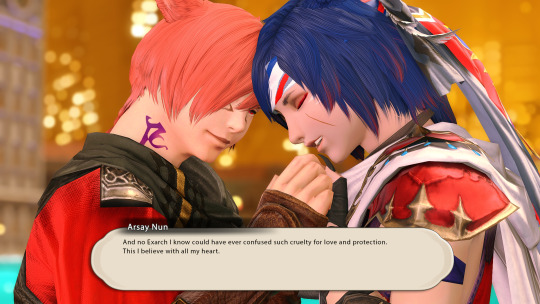

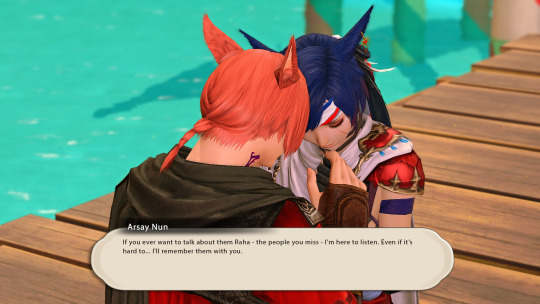

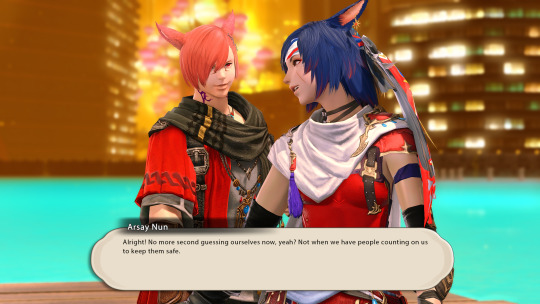

MiqoMarch Day 11 - Loss

#dawntrail spoilers#ffxiv#miqomarch#miqomarch2025#g'raha tia#arsay nun#wolgraha#dawntrail#ffxiv spoilers#oof this was a doozy to write and pose but i got through it 😭#i was going to expand on the bird metaphor initially but then I remembered that Arsay doesnt really do that. she just says shit#so you the viewer gets to decide what she means#I feel like its been a while since I've shown Arsay lifting her partner up in a conversation#shes been real baby since endwalker so its usually her who needed the support#im glad DT gave me a moment for Arsay to show her inspiring side now that shes gone through endwalker character development#were it any other character she would have said nothing tbh These are feelings she could only reveal to raha and shtola#so many people have done amazing takes on this scene and their wols replies i really hope this doesnt come off as reductive#or accidentally copying someone else#this part really hit me when I was playing because of irl reasons but even still i knew in the moment arsay would fight grahas doubt#because she believes so much in him and his kind soul. And shes seen it in action too. she sees a distinction between his actions-#- and that of others who claimed to do things for the good of their people#tbh arsay does kinda fall into the camp of 'would rather die than have to mourn another loved one' at this point#but if it came down to it I dont think shed be able to do anything but keep living- shes stronger than she believes herself to be

97 notes

·

View notes

Note

For your prompts: Mingjue is ace or demi, and somehow between taking over the sect at a very young age and never displaying interest in it, no one ever gave him The Sex Talk. All the aunts and uncles assumed someone else took care of it. Then Huaisang gets to that age. He seems to be very interested in sex. He needs The Sex Talk. Mingjue feels like that should come from him (he's taken care of all the rest pf raising him after all), but he doesn't have the info to do that.

How does Mingjue give him The Sex Talk? Or alternatively, does Huaisang end up already knowing and giving The Talk to his big brother instead?

ao3

“All right,” Nie Mingjue said, sitting down and gesturing for Nie Huaisang to sit down across from him. “I guess we’re going to have to talk about this.”

“I knew this day would come,” Nie Huaisang said, looking unbearably tragic. “I’m going to die of embarrassment before the day is through, da-ge. Won’t you have pity?”

Nie Mingjue knew him too well, though.

“Okay,” he said.

Nie Huaisang frowned at him.

“If it’s too embarrassing to talk about sex, you’re not ready to talk about sex,” Nie Mingjue said with a casual shrug. “We can postpone the conversation to –”

“No! I want to hear about it!” Nie Huaisang scowled at him. “Da-ge, everyone else got the sex talk! You wouldn’t want me to fall behind, would you?”

Nie Mingjue blinked innocently at him. “But Huaisang, you said…”

“Never mind what I said!”

Nie Mingjue tried to maintain his façade of innocent neutrality but quickly cracked in the face of Nie Huaisang’s exasperation; he started laughing.

Nie Huaisang grumbled.

“There’s not much to say,” Nie Mingjue said, wiping his eyes. “And it’s not as if you can’t get by without it, you know. I mean, no one ever gave me the talk.”

Nie Huaisang frowned. “No one? What about A-die? I mean, before…”

“He was busy, and kept postponing it,” Nie Mingjue said, shrugging. “And then he died, and everyone assumed he’d done it already. It’s fine. Everything I needed to learn, I learned from books, and you’re going to do the same.”

“…books.”

“Yep, books.”

Nie Huaisang heaved a sigh. “You’re going to make me learn this incredibly important subject from textbooks? Really, da-ge?”

“I am,” Nie Mingjue said.

“You’re robbing me of a valuable life experience here.”

“I’m so sad for you,” Nie Mingjue said dryly, pulling out a box and spreading out the books he’d obtained just for this purpose. “Now, I know you hate studying, I know you think it’s boring and a waste of time, but I really think in this instance –”

“It’s fine,” Nie Huaisang said quickly. His eyes were fixated on the books in front of him, and for some reason he’d flushed bright red, even though it wasn’t all that hot in the room. “I don’t mind. I’ll study hard, da-ge.”

“I feel like I’ve heard that before once or twice,” Nie Mingjue remarked, then shook his head. “Anyway, I think just one or two –”

“I need all of them.”

Nie Mingjue blinked, sincerely this time. “All of them?” he said, and looked down at the books. “Huaisang, I don’t think you understand. I got a selection so that you could have your pick, but they’re by and large very repetitive; each one more or less describes the same basic acts –”

“I need all of them. For reasons.”

“…all right,” Nie Mingjue said, bemused but generally pleased by Nie Huaisang’s highly unusual enthusiasm for study. “I thought I was robbing you of a valuable life experience?”

“That was before! I didn’t realize the books were going to be spring books,” Nie Huaisang said. He’d grabbed one and flipped it open, staring wide-eyed at one of the illustrations.

“What type of textbook would there be for this subject other than a spring book?” Nie Mingjue asked, wondering – as ever – if he’d missed something. Raising children was hard, and raising Nie Huaisang was harder; everyone agreed. “Anyway, I’m given to understand that the art is a bit exaggerated, especially in terms of proportion, and the accompanying text can use some rather strange metaphors, but fundamentally the acts described appear generally consistent throughout the various sources. For example, if you look at this one, you can see that the woman has –”

“Yes, da-ge, I can see.”

“I’m just pointing it out,” Nie Mingjue said defensively. Nie Huaisang was being especially impossible to understand today. “Anyway, it’s all a bit weird, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” Nie Huaisang said. “Very weird. Incredibly weird. You know what, I think I need to think about this privately for a while.”

“I…are you sure?”

“Very sure.”

“If you insist.” Nie Mingjue stood up. “If you have any questions –”

“Yes I’ll be sure to ask you please leave now thank you good-bye.”

Nie Mingjue found himself outside the door to Nie Huaisang’s room, not entirely sure how his much smaller younger brother had managed to push him out so effectively. Maybe some of that saber training was actually having an impact, however spaced out and half-hearted Nie Huaisang’s efforts were.

Cheered by the thought, Nie Mingjue headed back to his office, feeling very good about himself: that wasn’t nearly as awkward as all the other people had made it sound. It’d been no problem at all!

Of course, a few months later, he found out that Nie Huaisang had started buying up spring books like he’d developed a mania for it.

“That seems fine,” he said to the disciple who’d reported it. “I mean, it’s a bit strange, yes, but he’s always been fond of hobbies that involve collecting things. Birds, weird rocks…that sort of thing.”

“I’m not sure it’s…exactly the same,” the disciple said carefully. “But if you’re not concerned, Sect Leader, we’ll just leave it be.”

“…I’ll talk with him,” Nie Mingjue decided, mostly because of the weird expression on the disciple’s face, and the disciple looked relieved.

Later that evening, he followed up on his word.

“Huaisang, I heard you’re buying spring books,” he said, and Nie Huaisang nearly choked on his soup.

“You can’t just bring that up over dinner!” he hissed.

“…why not?”

“You just – can’t!”

“I can, and did,” Nie Mingjue said. “Some of the disciples have expressed some concern about it.”

Nie Huaisang’s shoulders went up by his ears defensively. “Is it because I’m buying cutsleeve books as well as regular books?”

“They sell cutsleeve books? Really?” Nie Mingjue said blankly, temporarily distracted. “I wouldn’t have thought there’d be enough of a market to make the printing worthwhile. Aren't they supposed to be relatively uncommon? …anyway, no, it’s not about that.”

“…you don’t mind?”

“Why would I mind?” Nie Mingjue said, puzzled. “I’m glad you’re expanding your horizons.”

“You…are?” Nie Huaisang was blinking rapidly.

“I mean, you’re reading? Reading is good. I’m always happy when you advance your scholarly pursuits,” Nie Mingjue said. “I mean, I’d still like it if you spent a bit more time on your saber…”

“Wait,” Nie Huaisang said hastily, clearly wanting to avoid the subject of his saber training. “If you don’t mind the fact that I’m buying them, or the content, what is the concern?”

“Mostly quantity, I think?” Nie Mingjue hadn’t been able to figure it out either. “You’ve exceeded your allowance twice already, and really, how many books recounting the same exact content can you really need?”

“It’s not quite the same content,” Nie Huaisang said. “There are different…scenarios.”

“Yes, but it all leads to the same place in the end, doesn’t it? Hand, mouth, front, back, inside or outside; you read one, you’ve read them all. Though I guess the cutsleeve ones are different?”

“Not really,” Nie Huaisang admitted. “But maybe take a look anyway? Maybe you’ll like those better…here, come up to my room.”

Nie Huaisang had, apparently, started in on making quite a collection, and from the way he puttered around trying to find the right ones to share, seemed to be in the process of becoming a little connoisseur. It was pretty adorable, actually; Nie Mingjue couldn’t remember the last time he’d seen Nie Huaisang so enthusiastic.

“Having two spears involved does seem to make it a bit more awkward,” he concluded after paging through a few. “And obviously you can’t do it from the front in the same way, but other than that the mechanics generally seem the same. I suppose there’s really only so many ways you can twist the human body…”

“How about this one, then?” Nie Huaisang said, offering up a book about mirror grinders sharing a toy between them. “Twice the young ladies involved!”

“That seems even less efficient. If they wanted to be penetrated, why be a mirror grinder instead of finding a man?”

Nie Huaisang seemed somewhat taken aback by the question. “Maybe they just fell in love with another woman first?” he eventually suggested.

That seemed reasonable enough, so Nie Mingjue nodded agreeably. “Makes sense that they’d use a toy, then. Otherwise wouldn't they be stuck with using just mouths and hands? Though I suppose there’s always the eponymous grinding motion, too.”

Nie Huaisang reached over and put his hand in Nie Mingjue’s lap.

“Huaisang! What are you doing?”

“Just checking,” Nie Huaisang said, rubbing the back of his head. “You’re really not…Wait, let me find you some others. Maybe you’ll like these better – they have more scenario involved.”

Truly Nie Huaisang had a wide collection. There were solo stories, coupled stories, stories involved groups of three or more, stories involving people being tied up or doing the tying, one story involving whips and pinching nails that Nie Mingjue initially thought was a torture manual that had gotten mixed in by mistake except for how the receiving party seemed extremely enthusiastic about it. There was even one involving –

“Fish?”

“Tentacles.”

“People want to fuck fish?”

“It’s not – you know what, I don’t know, maybe they do,” Nie Huaisang said, throwing up his hands. “Octopi are a surprisingly popular subject along the coast, and some of the artwork from Dongying features it.”

“You have works from Dongying?” Nie Mingjue asked, impressed. It wasn��t every young man’s hobby that involved international commerce. “You’re really turning into a collector, Huaisang.”

“I’m not – it’s not –” Nie Huaisang grimaced. “You know what, maybe the disciples are right and I should cut down on purchasing so many.”

“Why? If you’re enjoying your new hobby –”

“There’s a difference between being known as the guy who has some good spring books and being known as the guy who collects spring books as a hobby. The latter just sounds pathetic.”

Nie Mingjue wasn’t entirely sure about that.

“Well, it’s up to you,” he said, and started to get up to leave, only to have Nie Huaisang tug on his hand.

“Da-ge, I have a question.”

Nie Mingjue sat back down.

“Have you ever…?” Nie Huaisang nodded at the books.

“No,” Nie Mingjue said, wrinkling his nose a bit at the thought. “It seems like more trouble than it’s worth, really.”

“What about…uh…” He gestured at one in particular. Nie Mingjue leaned over and checked; it was one of the ones featuring a single man touching himself. “Do you…?”

“Oh, sure,” Nie Mingjue said. “Every once in a while. Don't most people? But there’s rather a difference between doing that and having to get up close and personal with someone else’s genitals, isn’t there? We all wipe our own asses after we shit, but that doesn’t mean we do it for other people.” He gave Nie Huaisang a pointed look. “Present company excluded.”

“I was a baby, it doesn’t count,” Nie Huaisang hissed at him. “Never bring it up again.”

Nie Mingjue smirked at him.

Nie Huaisang rolled his eyes dramatically. “Da-ge, you’re hopeless. One day you’ll find someone you like enough to try it with!”

“Maybe,” Nie Mingjue said. “Maybe not. It doesn’t really matter, does it?”

“Uh, yes it does! You’re going to have kids, aren’t you?”

“I haven’t decided yet,” Nie Mingjue said, hesitating a little. “Huaisang, you’re my heir.”

“I know that! I’m in line until you have kids of your own to inherit…why are you shaking your head?”

“You’re going to inherit after me,” Nie Mingjue said, as gently as he could. “I’m probably not going to have kids, but even if I did, I’d arrange it so that they’d be part of the branch family, not the main line. I want you to inherit.”

Nie Huaisang’s eyes were going wide.

No, it was too early to tell him about the saber spirits, Nie Mingjue thought to himself. About their family's horrible temper and his private suspicion that the temper and the qi deviations fed into each other; his conviction that Nie Huaisang would be a better sect leader than him, a better continuation for their line than him, and his determination to make sure that the next generation of Nie sect leaders didn't have to fear a shortened life the way he did. He’d tell him that later, sometime. Today was a good day, there was no point in spoiling it.

“Is that going to be a problem?” he asked instead. “I mean, you have such a wide variety here; don’t tell me you’re solely interested in cut-sleeves…?”

“No,” Nie Huaisang said. “No, I like – everything.”

“Well, then,” Nie Mingjue said. “There should be no problem, then. If you end up with a woman, have some kids; if you end up with a man, take a concubine. Either way, you’ll get an heir.” He frowned. “Assuming you don’t mind –”

“No, da-ge,” Nie Huaisang said, and he sounded incredibly long-suffering. “I think I’ll manage to have sex, somehow.”

“Well, I mean, if you’re thinking about actually going ahead and trying it out, that’s a whole different conversation we need to have, as opposed to the talk about what it is. You need to be careful about it –”

“Ugh, da-ge, please, no –”

“I’m not going to lecture! Just don’t overdo it or anything. You don’t want to end up with a thousand bastards like Sect Leader Jin –”

“Gross! No!”

“– or with all sorts of diseases –”

“Da-ge!”

“– or with a reputation for being a dissolute or a –”

“I will only have sex with someone I love,” Nie Huaisang announced. “Or at least mildly care for. A nice clean person who likes me back. Okay? Is that what you wanted to hear?”

“More or less,” Nie Mingjue said, and glanced down at the books. “Say, Huaisang. You know so much about this. Have you ever…”

“Do you have a question?” Nie Huaisang scooted forward. “Ask away, da-ge!”

Nie Mingjue flicked his forehead. “Not a substantive one. But have you ever thought about making your own? You’re a perfectly good artist, and you’re very imaginative; I’m sure you could come up with some scenarios of your own that might be very interesting.”

Nie Huaisang’s eyes were wide. “I could, couldn’t I?” he said, marveling, and then suddenly jumped up and dashed over to grab some paper. “Oh, I could! I could – and that – and – and..!”

Nie Mingjue decided to retreat, smiling proudly to himself.

Reading and writing, he thought happily. They’d probably never get a warrior out of Nie Huaisang, but there might be a scholar in him yet!

403 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greta Gerwig: 'I'm at peak shock and happiness'

by Tim Lewis, Sun 4 Feb 2018.

source: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/feb/04/greta-gerwig-lady-bird-interview-metoo-oscars

This year’s Oscar nominations were announced a couple of Tuesdays ago in Los Angeles at the frankly antisocial hour of 5.22am. Greta Gerwig, whose very personal, coming-of-age debut film Lady Bird was hotly tipped, lives in New York but happened to be in LA for work. She woke up first at 3.30am: “And I said, ‘No, it’s not time’ and I forced myself to go back to sleep.” When she eventually surfaced just before seven, the nominations were headlines around the world. Gerwig made herself a coffee, had a shower and ever-so-casually checked her phone. There it was: she’d made the cut for best original screenplay. And “achievement in directing”. Oh, and Lady Bird was in the running for best picture, too.

“I started crying and laughing and screaming,” says the 34-year-old Gerwig, who, until now, has been mainly known as an actor, often in comic roles. “And it sunk in… It’s still sinking in. It doesn’t quite feel real. You’re still getting me at peak shock and happiness.”

The Oscar selections were a personal triumph for Gerwig and for Lady Bird – its stars, Saoirse Ronan and Laurie Metcalf, who play a squabbling daughter and mother, are also nominated – but it was an important moment for female film-makers everywhere. Gerwig, scarcely credibly, is only the fifth woman ever to be shortlisted in the best director category at the Academy Awards in its 90 years. If she wins on 4 March, she will only be the second, after Kathryn Bigelow for The Hurt Locker in 2010, to take the honour.

“I remember very well when Sofia Coppola was nominated for best director and won best screenplay [for Lost in Translation in 2004] and what that meant to me,” says Gerwig on the phone from New York last week. “And I remember when Kathryn Bigelow won for best director and how it seemed as if possibilities were expanded because of it. I genuinely hope that what this means to women of all ages – young women, women who are well into their careers – is that they look at this and they think, ‘I want to go make my movie.’ Because a diversity of storytellers is incredibly important and also I want to see their movies. I want to know what they have to say! So I hope that’s what it does.”

These have been a seismic few months for women in the film industry. The allegations against the producer Harvey Weinstein and others, while monstrous in their scope and detail, have led to the most positive kind of backlash: through the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements, and the 50/50 by 2020 initiative, which aims to have male-female parity in the business world in two years. There’s an optimism that Hollywood has changed for ever.

“I think it’s going to shift much more quickly now,” says Gerwig. “When studios are looking to hire now, they’ll ask themselves – as they rightly should – ‘Is there a woman who is qualified for this job?’ That’s tremendously important. And again, if I were running a studio, I would think that it’s just good business. Because I look at the audience response to films made by women about women that have done incredibly well and I’d say, ‘Well, that’s a reason right off the bat.’”

As for whether there are any plans for a co-ordinated style protest at this year���s Oscars, in line with the black gowns at the Golden Globes or white roses at the Grammys, both orchestrated by the Time’s Up organisers, Gerwig is unsure. “I am not aware of a dress code,” she says. But if there is, she’s in: “I’m in awe of the people who are collectively working on this.”

Gerwig insists she hasn’t dared yet think about how it would feel to win an Oscar. But if the Golden Globes, where Lady Bird took the prize for best film (comedy/musical), is anything to go by, she might well struggle to hold it together. “I had an entire speech prepared but once I got up there, none of it came out,” she says with a laugh. “I was looking down and I saw Oprah and Steven Spielberg and I just went into a state of sublime happiness. I think I just said ‘thank you’ a lot. So my guess would be, I’ll prepare and probably I’ll not say any of it – if it should happen. Because that’s just how those moments seem to go for me.”

When I first talk to Gerwig, on an otherwise regulation Friday during the London film festival, there is a surreal, even comic, imbalance in London’s Soho hotel. Movie stars, it appears, outnumber the rest of us. Bill Nighy stands at a urinal in the men’s room, director Alexander Payne sweeps through the lobby. In the lift up to the suite where Gerwig is doing interviews, who else? The great Christoph Waltz.

“Christoph Waltz is here?” she shrieks. The pair became friends when they were on the jury for the Berlin film festival and catch up every so often for dinner in New York. “He’s one of my favourite people; he makes fun of me the entire time,” says Gerwig. “On the jury, there was this one time where we had a meeting with Angela Merkel. So I wore something that felt appropriate for a daytime lunch with a head of state. And I showed up and Christoph looked at me and said – she slips into a strident Mitteleuropean accent – ‘Greta, are you applying for an internship with Angela?’” Gerwig cracks up. “‘Did you bring your resumé?’ I looked such a nerd.”

Payne she knows less well, but is an ardent fan. At the Telluride festival last September, there was a photocall for the film-makers in attendance and Gerwig collected a giant bruise on her leg trying to hurdle a bench to tell Payne how much she liked his latest movie, Downsizing. “I thought, ‘I must tell him it’s a masterpiece,’” she explains. “So as I’m jumping over the bench, it clipped my shin and I went sprawling. Everyone turned to look and I looked up at him and I said, ‘It was a masterpiece!’ And he said, ‘You could have just walked over.’”

Right now, there are plenty of people – rightly and properly, albeit metaphorically – tripping over furniture to tell Gerwig that she’s made her own masterpiece. Lady Bird is a beautiful, affectionate rumination on the mother-daughter dynamic that could well be this year’s Moonlight: an underdog that charms and surprises, and overshadows everything else.

It is not immediately clear how to square these achievements with Gerwig’s tendency towards self-deprecation. Physically, she mixes elegance with eccentricity. At 5ft 9in, with credulous sea-green eyes, and today wearing a pink, pleated cocktail dress with buckled black-and-white heels, she presents an image of impossible glamour. But she undercuts the effect by slouching a little, laughing unguardedly and demonstrating odd and endearing mannerisms, such as the stiff handshake of a Victorian industrialist packing his son off to boarding school.

“I arrived on a flight this morning at 6am, so this is all pretend,” she explains, smoothing an invisible wrinkle on her frock. “I don’t actually feel like this inside. People came to my room and made me look nice. I know, everyone needs it.”

In Lady Bird and before, Gerwig is drawn to dreamers: young women who believe they are destined for greatness, even when the audience finds plenty of cause to doubt that. The film follows Ronan as 17-year-old Christine McPherson, who’d rather you call her Lady Bird: when asked if it’s her given name, she clarifies: “It’s given to me, by me.” The year is 2002, the place is Sacramento, a mid-size city in California, and both these facts are a cruel disappointment to her: “The only exciting thing about 2002 is that it’s a palindrome,” Lady Bird sighs. She’s in her final year at an all-girls Catholic high school and, after graduating, she wants to move to the east coast to study, “where writers live in the woods”. This is one of many, though perhaps the most irreconcilable, point of contention with her mother, Marion (a heart-wrenching Metcalf).

It has been a common assumption that Lady Bird is Gerwig’s teenage diaries transcribed. She, too, grew up in Sacramento and attended a Catholic school there, before escaping to the other side of the country, to Barnard College in New York, where she studied English and wanted to become a playwright. But, Gerwig notes, not sniffily, that there are plenty of differences, as well. She didn’t dye her hair pink or assume a strange name or even argue that viciously with her mother.

“Even though it isn’t literally autobiographical there’s a core of emotional truth that’s very resonant,” says Gerwig. “Again, it’s not what literally happened, but it does rhyme with the truth. It’s close in a way. And it doesn’t bother me, because it’s the assumption people make and in a way maybe they make that assumption because it feels very real. So it’s not dissimilar to when people think a character is you. Which you could be offended by or you could also think, ‘Well, then I’ve done my job. You’ve believed it. You think that’s me.’

“But I don’t know,” she continues. “I think one thing about doing this for a period of time is that you learn how to live through either misconceptions or correct conceptions and just continue doing the work. Because then you figure, ‘Well, in the end, I’ll just be an old lady one day and then they’ll think, Oh, she’s an old lady.’ And they’ll be right!”

What, then, are some solid, hard facts about Gerwig? She is the eldest child of Gordon and Christine, a loans officer for a credit union and a retired nurse respectively. As a child, she was a diligent student with an obsessive streak: her first passion was dancing; later, she would become skilled in the sport of fencing.

“I loved ballet,” says Gerwig. “I always knew I wasn’t the most naturally gifted of anyone who was doing ballet. I didn’t have quite enough turn out, my feet weren’t quite right, but I did work harder than anyone else. And I think that’s something I have maintained. There’s no substitute for hard work.”

Gerwig acted a little at school but became more serious at college. She saw herself as a theatre person, but when she was rejected from graduate programmes in playwriting, she started working on films with her friends. These no-budget projects became notorious in arty, hipster circles and then beyond, where they were, somewhat derisively, called mumblecore; they were sketched out, but not scripted, and the makers were involved in every aspect of production.

“Those became kind of a makeshift film school for me,” says Gerwig, referring to LOL (2006), Hannah Takes the Stairs (2007) and Nights and Weekends (2008), which she made with Joe Swanberg. “When I went into pre-production for Lady Bird, I’d been working in films in different capacities for 10 years. Especially on the early little ones because it was an all-hands-on-deck situation. If you weren’t doing something on camera, you held the camera.”

These early films, too, led in a roundabout way to Gerwig’s acting breakthrough. Swanberg knew the director Noah Baumbach and he then cast her in his 2010 film Greenberg, opposite Ben Stiller. The film received mixed notices, but Gerwig’s performance caught many eyes. In the New York Times, critic AO Scott described her style as a method without method. “Ms Gerwig,” he wrote, “most likely without intending to be anything of the kind, may well be the definitive screen actress of her generation, a judgment I offer with all sincerity and a measure of ambivalence.”

Greenberg was a life-changing experience personally as well: after it wrapped, Gerwig and Baumbach began dating, for a while on the down-low, these days more openly, though Gerwig tends to refer to him as “Noah Baumbach” or “Baumbach” in our interview, suggesting they keep their work and private lives quite distinct. They soon began collaborating and their first film as a writing team was 2012’s Frances Ha, a warm-hearted, black-and-white comedy about a dancer, Frances (Gerwig), who doesn’t seem wholly cut out for the real world. They followed that with Mistress America in 2015, which has a similar vibe: Gerwig plays Brooke, who has a million creative ideas and a very low strike rate.

Gerwig’s writing, first with Baumbach and now on her own, has a naturalistic tone that is funny without having jokes, heartbreaking without being schmaltzy, highly specific and yet clearly universal. She is so particular about how the dialogue sounds – the “music” of speech – that there is a not a single line of improvisation in Lady Bird, not even an added “like” or “you know”.

“I like language that sounds quotidian but poetic,” says Gerwig – the perfect description. “Something that maybe the character doesn’t even know is as beautiful as it is. That’s something I was working through when I was writing with Noah Baumbach and I just kept moving in that direction. That was always what I liked. That quality of stumbling into beauty and then it’s gone.”

It is a timely moment for Gerwig to emerge as a director and for her debut to have such an assured, idiosyncratic voice. Despite the success of Lady Bird at the Golden Globes in January, Gerwig was a glaring absentee on the best director shortlist. Natalie Portman, presenting the award, made the point succinctly, announcing: “And here are the all-male nominees.” Likewise, the Baftas have a five-man shortlist.

Of course, this is just one facet of the soul searching that the film industry is now going through. In the week that I meet Gerwig, the first allegations of sexual abuse have been made against Harvey Weinstein, and it was clear that Gerwig found the revelations upsetting and deeply shocking.

“I felt so badly for all those women,” she says, “and I felt so understanding of where they were, especially the young women, the women who were in college, the women who were just excited about movies and film-making and found themselves in a position that they didn’t know how to say no, but they didn’t know how to leave and that they felt overpowered and then they felt scared to say anything.”

There are tears in her eyes; her voice cracks. “I’ve felt for so long that there just need to be more women in positions of power,” Gerwig goes on. “Not that women are magic or perfect beings, but that they need to have a seat at the table because then I would think that things like this would have far less chance of happening.”

When Gerwig realised she was writing about mothers and daughters, she started thinking about movies that covered a similar theme. There were hundreds of films on the father-son relationship, including some excellent ones by Baumbach, but she struggled to think of stories told from the female perspective: James Brooks’s Terms of Endearment (1983) and Mike Leigh’s Secrets and Lies (1996) were among the rare inspirations. “There are surprisingly few movies about it,” says Gerwig, “and I think that speaks to the fact that there are surprisingly few female film-makers.”

In preparation for shooting Lady Bird, Gerwig created dossiers for her lead characters. Timothée Chalamet, for example – who plays Lady Bird’s crush Kyle and is also Oscar-nominated this year for his role in another coming-of- age drama, Call Me By Your Name – was directed towards the films of Éric Rohmer and a collection of theoretical essays, The Internet Does Not Exist. Kyle is a pretentious mansplainer: he lectures Lady Bird on how mobile phones are tracking devices for the government and that clove cigarettes have fibreglass in them. At one point, he puts down Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States to announce, “I’m trying to live by bartering alone”.

Kyle’s a pseud, but Gerwig clearly has a soft spot for him. “I am not a fan of phones,” she explains. “I talked for a long time with Timothée about his character’s beliefs, and he said, ‘The funny thing is that everybody is going to think you’re Lady Bird, but you’re Kyle’.” Gerwig laughs, “And I was like, ‘I know! I am secretly Kyle.’ I have all of the same paranoias as Kyle does.”

Gerwig is technically a millennial, but not spiritually so. She grew up pre-internet and has no social media presence: “Sure, I’ll lurk. But I don’t participate. I’m just a Peeping Tom.” Part of the reason for setting Lady Bird in 2002 is that it’s not “cinematic” to shoot screens. She longs for the pre-phone era when you couldn’t get hold of someone instantly, and the only way to find them would be to drive around to all the locations they might be. We rarely allow ourselves to become properly bored, Gerwig believes, and the internet and smartphones are in part responsible.

On the wall of her bedroom, Lady Bird has the Leo Tolstoy quote, “Boredom: the desire for desires.” “Boredom is, I think, pretty useful,” says Gerwig. “You need to reach a level of boredom to make anything. Because I don’t know if you remember, being bored as a kid, just so bored. You were at a grocery store with your mom and you were like, ‘It’s just excruciating!’ But then you get to a point where you start making up a game for yourself or you’ll start imagining things or whatever it is. But I worry that we’ve lost that capacity, which I think maybe erodes some creativity as well.

“I’m just as bad as anyone,” she admits. “Because it’s like your flitting brain can be completely satisfied by this machine that can give you feedback for all of your passing thoughts. Like, ‘Where can you grow avocados?’ I don’t know, let’s find out. And then, ‘Oh, how much water does an avocado tree take every year?’ Let’s look at that. And then, ‘Different crops and the water usage for each of them.’ You are creating this weird feedback loop for yourself.”

This is a very Gerwigian conundrum: hem-hawing about restricting access to the internet because she’s worried she’ll waste time Googling avocados. But she’s not saying it to be cute. It clearly concerns her. One of the strict directives on the set of the Lady Bird was that it was entirely phone-free. “And not just for the actors, for the crew,” she says, “because it’s quite depressing for an actor to be doing an emotional scene and look over and see someone checking Instagram. It’s a real bummer. But it was quite impressive, because I had a lot of young people in this movie and none of them ever brought their phones to set. Saoirse set the tone: I never saw her on her phone, never once.”

Gerwig is effusive about her two stars, Ronan and Metcalf. Everything in the film, she says, comes back to “the central love story” between Marion and Christine, mother and daughter. “For all of time it’s probably been the most rich, fraught relationship. Something with Laurie and Saoirse that I loved was that they were the same height and I gave them the same haircuts so that when they were in profile, you say: ‘Oh, you’re so at odds with each other but actually you’re the same. And that’s why the fighting is so intense because you guys can both bring it.’

“So I knew I needed actresses who could punch the same weight class,” Gerwig adds. “They give extraordinary performances and they should get all the statues and prizes. Work like that should be rewarded.”

For her part, whatever happens, Gerwig insists that little will change. She will keep acting – when the project and specifically the director is right – and she wants to collaborate with Baumbach again: “I hope Noah and I will write another movie together because it’s really, really fun.” She also wants to start her own production company one day. “It’s important that if you have any kind of a platform and it matters to you that you should figure out how to bring other people along,” she says.

As for the Oscars, she is not about to pretend that she’s not freaking out a little. “I grew up watching all the award shows and I’d put on a fancy dress and watch it with my friends,” Gerwig recalls. “It’s thrilling and it’s also part of what the dream of making films is.”

Then Gerwig’s eyes narrow; these are defining moments both for her personally as a director and also as an inspirational member of the too-small band of female film-makers. “But awards are not important in terms of whether or not I’ll make another film,” she says. “I’ll keep making films, no matter what.”

0 notes