#i want to do an essay on race and accusations of witchcraft

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This is true.

Below is a New England newspaper editorial article, written by Boston to New York. The writer likens the 1741 slave conspiracy to the frenzy of the Salem Witch Trials where accusations were being thrown around and panic was being stirred up for no good reason. This editorial shows a pivotal moment in American rhetoric; the phrase "witch hunt" no longer meant a literal hunt for witches but rather its contemporary use of a metaphorical hunt marked by paranoia and wild accusations to uncover a supposed conspiracy.

The best account of the 1741 slave conspiracy is in the book New York Buring: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in the Eighteenth Century Manhattan by Jill Lepore.

The transcription below is taken from The New England Weekly Journal, September 29, 1741, pages 1-2. This passage has period-typical language that is now considered offensive; I have not censored it to preserve its historical accuracy.

"Province of the Massachusetts Bay, 1741. Sir, I am a stranger to you and to New York, and so must beg pardon for the mistakes I may be guilty of in the subsequent attempt, the design wherof is to put an end to the bloody tragedy that has been, and I suppose is still acting among you, in regard of the poor Negros and the whites too.

I observe in one of the Boston newsletters, dated July 13, that 2 Negros were executed in one day at the gallows, a favor indeed! For one the next day was burned at the stake, where he impeached several others, and among them some whites, which, with the former terrible executions among you upon this occasion, puts me in mind of our New England witchcraft in the year 1692, which, if I don't mistake, New York justly reproached us for and mocked at our credulity about. But may it not now be justly retorted, Mutato nomine, de te Fabula Narratur? What ground you proceed upon, I must acknowledge myself not sufficiently informed of. But finding that those five that were executed in July denied any guilt, it makes me suspect that your present case, and ours heretofore, are much the same, and that Negro and specter evidence will turn out alike. We had near 50 confessors who accused multitudes of others, alleging time and place and various other circumstances to render their confessions credible, that they had their meetings, formed confederacies, signed the Devil's book, et cetera. And as long as confessions were received and encouraged, accusations multiplied and increased: But I am humbly of opinion that such confessions and the evidences founded theron are not worth a straw, unless some certain overt act (that nobody else could preform) appear to confirm the fame. For many times they are obtained by foul means, by force or torture, by flattery or surprise, by over watch or distraction, by discontent with their circumstances, through envy or malice, or in hopes of a longer time to live, or to die an easier death, et cetera. For anybody would choose rather to be hanged that to be burned. It is true I have heard something of your forts being burned, but that might be by lightning from heaven, by accident, by some malicious person or persons of our own color. What other facts have been performed to petrify your hearts against the poor blacks, and some of your neighbors, the whites, I can't tell. Possibly there have been some murmurings among the Negros, and a few mad fellows may have threatened and designed revenge for the cruelty and inhumanity they have met with, which is too rife in the English plantations, and not long since occasioned such another tremendous and unreasonable a massacre at Antigua. But two things seem to me almost as impossible as for witches to fly in the air, or change themselves into cats, namely, that the whites should join with blacks; or that the blacks (among whom there are no doubt some rational persons) should attempt the destruction of a city, when it is impossible they should escape the just and direful vengeance of the countries round about, which would immediately pour in upon, and swallow them up quick. And therefore if nothing will put an end to the doleful tragedy till some of higher degree and better circumstances and characters are accused (which finished our Salem witchcraft), the sooner the better, lest all the poor people of your government perish in the merciless flames of an imaginary plot. In the meantime don't be offended if out of friendship to my poor countrymen, and compassion to the Negros (who are partakers of the same nature with us and ought to be treated with humanity), I entreat you not to go on to destroy your own estates by making bonfires of your Negros, and thereby perhaps loading yourselves with greater guilt than theirs. For we have too much reason to fear that the divine vengeance does and will pursue us for our ill treatment to the bodies and souls of our poor slaves, and the meaner sort of people. And therefore let justice be done whenever you sit in judicature about their affairs. All which is humbly submitted by a well-wisher to all human beings, and one that ever desires to be of the merciful side, et cetera."

in 1741 there was a pogrom against the enslaved black population of new york who made up around 20% of the city. this came during a time of economic decline in colonial new york, as white settlers began to feel threatened by the growing number of women and enslaved people in the workforce. reports of slave revolts in other american colonies and abroad fueled increasing paranoia among the white population of a large scale revolt or insurrection.

after various fires were found around the new york, white settlers quickly spread rumors that the enslaved people were planning to burn down city and kill its inhabitants. other unrelated incidents that happened around the same time, such as three enslaved people robbing a store owned by a white couple, were seen as proof of the conspiracy and fueled the racist hysteria.

the evidence of the 'conspiracy' was based mainly on the testimony of one 16 year old girl, mary burton, a white indentured servant. promised a reward for her cooperation, mary accused dozens people of taking part in the conspiracy. nearly 200 people were arrested, including 20 white settlers. despite the lack of evidence, the judge sentenced nearly 40 people to death and many others to exile and forced labor in slave plantations in the carribean. many of those executed were burned alive, tortured, and had their corpses left to rot in the public square. slavery wasn't outlawed in new york until nearly a decade later.

fuck this country 1000000 million times forever. very little has changed

#i want to do an essay on race and accusations of witchcraft#tw racsim#tw slavery#tw slur#witch#witchcraft#historical witchcraft#premodern art#artist talk

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

3Imcrucible

Fear is a very real thing all human beings have that sense. in America we suffer with terrorist attacks, as we have encountered them before in 9/11 and also messages have been sent to us threatening to disturb our peace. The fear of high tax, gas; many are afraid to loose their jobs or have a bad reputation ..Etc the list is endless. This relates to the book the crucible because Its obvious that everyone is afraid to be blamed for witchcraft. The character Abigail is a good example of a person who is afraid, she showed fear when she refused to answer questions concerning to witchery and having sexual relation with john proctor. The way she did to cope with not having john proctor was making up lies so that Elizabeth[john proctors wife] could be hung and she could have him all to himself. This also leads to her being afraid of not being good enough for someone. Even us here in the teenage America we come across trying to fit in with the right group and being afraid of not succeeding. Another example will be john proctor he had fear of loosing his job because of the accusations that Abigail made, now a days people can’t come and take the right for your responsibilities and seem to just make up lies to cover their mistakes. All the girls that were seen In the forest dancing and doing some kind of “ witchcraft” became afraid of being hung so they all lied and pretended that they saw things that weren’t really there. Fear in salem was always there but some came in front of it another example in America people are afraid of Mexicans and want them out because they think that they are bad and cause trouble here in America and that also goes for muslims, that relates to the crucible because people were accusing others of witchery just because by implying it when in reality it wasn’t true. You can make a judgment on someone because of the history of their race,its unfair and condescending.

Why didn't you finish? Let me know when I should re-grade. 5/20 Mrs. R.

2008 slacker essay

0 notes

Text

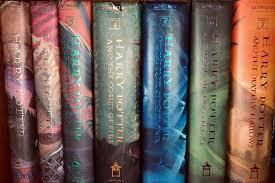

J. K. Rowling: Ruined or Revered?

By Cayleigh Pine

When I was in fifth grade, my overly-Christian mother finally allowed me to read the famous Harry Potter series, the same books that millions of children became avid readers of to the dismay of conservative church-goers against witchcraft. I distinctly remember being obsessed with the series, reading one book after another before bed, in restaurants and even during my brother’s basketball games. I became attached to the fictional wizarding world, and I admired author J.K. Rowling’s description of characters that any reader could fall in love with. And readers certainly did, with Harry Potter spanning a blockbuster film franchise, a theme park, a Broadway play, a video game, as well as several controversies regarding its creator. In an age where the fanbase of Harry Potter is stronger than ever, it seems that there are complexities beneath the surface of this fandom, with many furious at Rowling for adding new (and admittingly, strange) details to the Potter-canon, as well as problematic statements posted online. Going from an idolized billionaire authorial goddess to someone almost as hated as her Voldemort antagonist, Potter fans have changed over the years in their support of Rowling and how they view the series due to her many controversies. Due to this, many are conflicted on if they should still be fans of these works, or if they should allow Rowling’s influence to taint the positive message behind Harry Potter. All of this leads into the question: Should readers separate the author from their texts, or is their intent all-encompassing?

Readers tend to become fans of not only their favorite books, but of the authors that write them, leading them into learning about the author’s personal background and writing process. However, others tend to ignore who the author is in favor of not letting them influence how they read a story. “Death of the Author” is a literary concept that was created by Roland Barthes in the essay La mort de l'auteur published in 1967 (Barthes). This theory spawned off of the New Criticism literary movement, delving into the idea that readers should not have the author’s intention influence their understanding of the work being read, acting as though the author is dead or non-existent. Barthes argues that giving a text a single interpretation from the author limits the creativity and imagination the readers can develop off of that work, and how interpretive tyranny only works to the detriment of the reader, forcing an idea on them instead of having the reader come up with their own understanding (Barthes 5). This theorist explains that instead of looking to our authors as god-like and creating something out of nothing, Barthes tries to explain through this concept that there are no original works since writers are influenced by multiple factors, such as: mythology, religion, and other authors. This means there should be multiple interpretations since there are various sources (Barthes 4). In Ancient Greece, playwrights were open to where the sources of their stories came from, re-telling the tales of Achilles and Electra and others and never proclaiming to be original. However, in 1960s society, authors liked to pretend they were the sole, divine creator of their literary universes, and this has continued to the present. The popularity behind the term “Death of the Author” has risen and fallen throughout the years, but the support behind this literary concept has since gained traction with the recent advent of social media. Authors are now posting on their Twitter about character's motivations or secrets that were never expounded upon in their books, leading fans into an uproar against authorial intent.

J.K. Rowling has always been an author in the public eye, her Harry Potter novels launching her into a celebrity icon due to how well-loved they are. With around 500 million copies sold world-wide, she became beloved by many who thought of her as their favorite author (Pottermore). One of the many reasons for this is due to the Barthes-like influence her readers hold in viewing Rowling’s work. Christian groups protested the series after every release, believing that what was in the books promoted Satanism and the occult (Halford 2). Despite Rowling being a Christian (Halford 3), these religious fundamentalists practiced “Death of the Author” to ignore Rowling’s background that is similar to theirs, instead viewing their own interpretation of the Harry Potter series as an unholy promotion of witchcraft for children, which is a very different perspective from what the author intended. However, this also worked in the reverse for readers of the same religion. Many other Christians that are fans of the series used Barthes’ theory to interpret many Christian allegories in the series that they could relate to their own backgrounds, a common example being Harry’s sacrificial death and resurrection in Deathly Hallows mimicking that of Jesus Christ’s in The Bible. Christians seem to find their religion in the stories Rowling created, intentionally or not, and use their interpretations as evidence to the series being in support of or against Christianity.

However, religious groups are not alone in using “Death of the Author” to interpret Rowling’s writing. According to the study: “The Greatest Magic of Harry Potter: Reducing Prejudice” published in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology, psychologist Loris Vezzali asked fifth graders to fill out a questionnaire about their attitudes toward minority groups, then had them read excerpts from the Harry Potter books that dealt with prejudice. Specifically, the blood prejudice that is a major theme in the books about how some “pure-bloods” consider themselves better wizards than “half-bloods” or “muggle-borns” due their different backgrounds. According to readers, this is an allegory for racism, and this theory shines through with how Vezzali’s study proved that young readers living vicariously through the characters in Harry Potter impacted their attitudes positively towards marginalized people in real life (Vezzali). Readers tend to use this as a basis for the series being progressive, interpreting the series to be against racism. Unfortunately, the series is not as cut and dry as this. According to the Midwest Quarterly, author Christine Schott argues that there is racism prevalent in this series, but fans ignore these instances. The house elves in this story are essentially slaves for pureblood wizard families and who “do not want to be freed” even when characters offer to help save them. Schott explains that the creation of creatures that desire to be slaves teaches readers a message that some beings are naturally inferior to others and want to be enslaved, which is a horrible message if these books are supposedly “progressive” (Schott). It seems here that Harry Potter can be, and has been, interpreted in various ways, all due to who the reader is and how they utilize “Death of the Author”.

Besides there being many interpretations of this series, the majority of fans tend to look at the books as an allegory for sticking up for underrepresented groups. It seems that Rowling also gravitated to this positive interpretation, with how she began to make additions to her wizarding world in order to appear inclusive, but they all seemed to backfire. Her controversies began in a 2007 Q&A session at Carnegie Hall with fans of the recently released Deathly Hallows, where she stated Dumbledore was gay (Smith 2). This split the fandom into two groups: supporters who thought this was great representation for the LGBTQ+ community, and those that questioned why Rowling felt the need to reveal this if she never included Dumbledore’s sexuality in the books. The latter’s opinion has intensified over the eight years since this comment, and with Rowling’s new Fantastic Beasts film franchise—prequels including a young Dumbledore—that still do not explore his sexuality, fans are speculating that she has been using Dumbledore as a way to prove she is “progressive” with nothing to show for it, accusing her of the harmful marketing tactic “queer-baiting” in order to attract the queer audience while not offending conservative consumers (Bradley 3). This past comment led into more controversial statements, like her comparing her fictional werewolves to the AIDs epidemic in the US (Baillie 2). This shocked many people because most of the werewolves in her books were framed as villains that preyed on young wizards, so with Rowling’s commentary, this comment becomes a metaphor for gay people preying on children. Because of Rowling, the readers’ interpretation has shifted from viewing werewolves as mythological creatures to now gay predators in disguise. The add-ons do not end there, with Rowling beginning to use her characters to advance her political views, utilizing the titular character Harry Potter to say that he would support the boycott against Israel, so you should, too, as well as to deny describing characters’ races in her books in order to appeal to a more diverse crowd (Donaldson 4). She constantly uses her Twitter to inform fans of her new changes to her fictional universe, yet she disappoints them by not including her supposedly progressive ideals in her works outside of social media. Her race and sexuality-bending has become such a hot topic that it became a meme when a comedic article called, “J. K. Rowling Proves That You, the Reader, Were Gay All Along” was published in 2019 to The Hard Times, poking fun at Rowling’s new revelations about characters’ identities that are never shown in her books (Hernandez). Since then, thousands of social media users made Youtube videos, tweets, and memes, parodying her characters, and even her readers, finding out from her that they had an identity they never knew about. However, even with all of this, Rowling was never seen as a fully negative celebrity, at least until her most recent tweet.

In December of 2019, Rowling posted about supporting a transphobic woman named Maya Forstater in her mission on spreading the message that transwomen steal the jobs of ciswomen, repping the hashtag #IStandwithMaya proudly for all of her 14.5 million followers to see (@jk_rowling). This was met with huge outrage from fans, especially those in the LGBTQ+ community. Readers became upset because they felt if they liked Harry Potter, they were supporting a transphobe, and many began to attribute this series with a negative connotation (Donaldson 5). Her fans were mostly upset with the hypocrisy behind this tweet and how Rowling could disregard a minority group, even though her books supposedly stood up against prejudice. However, others argue that Rowling can say and do anything she wants with her characters and their identities, and even the overall message of her book, due to the fact that she is the creator of the series. Writer Natasha Troyka states that, “Barthes’ argument in The Death of the Author focuses on the impossibility of guessing the author’s intentions. If we can’t read an author’s mind, we shouldn’t fixate on authorial intent when reading a story” (Troyka 4). In the case of Rowling’s use of social media, her fans are almost able to read her mind about her intentions due to her excessive tweets. But even with her explanations, fans are rejecting her new form of Twitter-storytelling, using not only Barthes’ theory to ignore her authorial intent, but a rejection of social media in itself. Due to the fact that Rowling is not writing any more physical Harry Potter books and posting add-ons to her Twitter, fans do not count these changes as “canon”, and Troyka argues that that is largely due to the lack of respect fans hold of Twitter versus a book (Troyka 5). This writer mentions how with every sequel the wizarding world changed, with turning from bad to good (in the case of Snape) or even additions to the lore (The Deathly Hallows being created). Troyka asks: What’s the difference between a sequel and a tweet? Who decides the boundaries of works, if it is extra or canon? If it happens on Twitter, does it make the writing any less “real”? The argument here is that even if fans disapprove of Rowling’s quasi-progressive add-ons to Harry Potter, it is still her writing and she still is the creator, so they should count as part of the series, regardless of what platform they are released on. Despite this, it seems that fans are using Barthes’ theory to not only kill off the author, but also any disliked changes she wants to make to the series.

Even though fans hate Rowling’s new additions, considering them more fanfiction than canon, she has always been supportive of fans using her work to create their own fanfiction, with her spokesperson saying she is, “... flattered people wanted to write their own stories based on her characters” (Waters 1). This is not always the case with many authors, such as author Anne Rice (The Vampire Chronicles) threatening to sue her fans if they write anything involving her characters. And then you have former-Youtuber-turned-author John Green, who not only supports whatever fans want to do with his work, but the concept of “Death of the Author” itself (“Death of the Author.”). Green became a famous author off of social media, gaining a fanbase through informational literary videos that analyze classic novels, and then finally releasing a book of his own. In his book, The Fault in Our Stars, the protagonist Hazel gets to meet her favorite author, and learns he’s a reclusive alcoholic whose personality ruins his works for her. This is a commentary on how much influence an author can have on their works, and how an author can ruin their own books for their fans with their wrongdoings that can taint their art. In 2014, Green tweeted, “Books belong to their readers” (@johngreen), agreeing with Barthes’ theory that fans get to hold the interpretation of the work and ignore the author behind it, which is probably a stance he later regretted when he started suffering backlash from fans about his portrayals of teenage girls (“Death of the Author”). In a Tumblr post, a fan described Green as, “...a creep that panders to teenage girls to amass a cult-like following”, wherein Green responded saying he never sexually assaulted anyone (Jusino 3). It was an odd response considering the post never mentioned him doing this, so fans immediately were suspicious. This uproar faded into nothing, but it left many readers feeling uncomfortable with his writing, and in recent years, many posts online shame Green’s portrayal of teenage girls for being two-dimensional. This has led to many using fanfiction as a way to fix what Green created, having the readers utilize their own interpretations “for good”. This is also seen with Rowling’s fans creating fanfiction that they deem better than Rowling’s books simply because it follows their interpretations instead of hers. From this, it is made apparent that when readers begin to dislike the author, they either step away from their works, separate the art from the artist, or they rewrite it to better suit their own interpretations.

Rowling seems to bank on the fact that her fans are so besotted by Harry Potter that none of her controversies can get in the way of people’s love for the wizarding world. Even with all of her problematic statements, Potter fans are still around, shown in how her recent prequel films racked up around $814 million worldwide (Mendelson 3), and the Harry Potter and the Cursed Child play based on the franchise breaking monetary records on Broadway (Chellman 3). It seems that even though there are those that are against Rowling and her political stances, the majority are not against her work and will not be boycotting Harry Potter any time soon.

Overall, it appears that J.K. Rowling remains one of the most famous authors in the world, and her problematic comments throughout her career have not done much to bring down her rule other than turn her into a comedic meme. Personally, I believe that it would take a lot more than problematic tweets to shut down this massive franchise, especially since Rowling has not faced any real-world consequences monetarily-wise. This goes to show just how much people love Harry Potter since they are willing to pay the bills of someone who may hold harmful beliefs that readers do not agree with. It has become such a phenomenon that people simply cannot leave this series due to a problematic author, and unless Rowling Avada-Kedevra’s someone, I believe that fans will keep separating her from her work in order to enjoy it without a guilty conscience. Fans are comfortable using “Death of the Author” to ignore Rowling’s controversial past, and even I am guilty of this. I used to automatically associate Harry Potter with Rowling, but now I view the series as its own entity with no relation to its creator in order to feel as though I am not supporting Rowling. It seems that there is no clear answer on whether separating the author’s work from them is morally correct or not, however it appears to be a popular choice for fans that want to take their own interpretation of the series and do as they please with it, even if that means blocking out—or just blocking on Twitter—the very creator of the wizarding world they love.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my mother for eventually letting me read Harry Potter, J.K. Rowling for writing the series, as well as for being such a fascinating topic, and Professor MKB for supporting me and this paper with her wonderful feedback.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. La mort de l'auteur (Death of the Author). Aspen Journal, 1967.

http://www.tbook.constantvzw.org/wp-content/death_authorbarthes.pdf

Baillie, Katie. "JK Rowling says Remus Lupin’s condition as a werewolf is ‘a metaphor for

illnesses with a stigma, like HIV and AIDS’ ." Metro News, 9 Sept. 2016, metro.co.uk/2016/09/09/jk-rowling-says-remus-lupins-condition-as-a-werewolf-is-a-metaphor-for-hiv-and-aids-6118903/.

Bradley, Laura. Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald and Dumbledore’s Vexing

Sexuality, 16 Nov. 2018, www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2018/11/fantastic-beasts-the-crimes-of-grindelwald-dumbledore-gay-queerbaiting.

Chellman, Jack. "The Gay Romance In The Cursed Child: A Letter To JK Rowling." Huffington

Post, 4 Aug. 2016, www.huffpost.com/entry/the-gay-romance-in-the-cursed-child-a-letter-to-jk_b_57a2a99de4b0c863d4002748?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAKENG0nWy3.

Donaldson, Kayleigh. " J.K. Rowling is the Exemplification of Why We Need the Death of the

Author." Pajiba, 24 Dec. 2019,

www.pajiba.com/miscellaneous/jk-rowling-is-the-exemplification-of-why-we-need-the-death-of-the-author.php.

Ellis, Lindsey. “Death of the Author.” Youtube, 31 Dec. 2018, https://youtu.be/MGn9x4-Y_7A.

Halford, Macy. Harry Potter and Religion, The New Yorker, 4 Nov. 2010,

www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/harry-potter-and-religion.

JK Rowling (@jk_rowling). “Dress however you please. Call yourself whatever you like. Sleep

with any consenting adult who’ll have you. Live your best life in peace and security. But force women out of their jobs for stating that sex is real? #IStandWithMaya.” 19 Dec 2019, 12:57 PM. Tweet.

Jusino, Teresa. "What John Green Needs to Learn About Having a Dialogue With Female YA

Readers." The Mary Sue, 2 July 2015, www.themarysue.com/john-green-female-ya-readers/.

Mendelson, Scott. "'Crimes Of Grindelwald' May Have Destroyed The 'Fantastic Beasts' Saga."

Forbes, 19 Nov. 2018, www.forbes.com/sites/scottmendelson/2018/11/19/box-office-crimes-of-grindelwald-may-have-killed-the-fantastic-beasts-saga-jk-rowling-johnny-depp/#483bd42122a2.

Pottermore (@pottermore). “However, when Hogwarts’ plumbing became more elaborate in the

eighteenth century (this was a rare instance of wizards copying Muggles, because hitherto they simply relieved themselves wherever they stood, and vanished the evidence)…" 4 Jan 2019, 1:34 PM. Tweet.

Pyrocynical. “J.K Rowling just ruined Harry potter.” Youtube, 3 Apr. 2019,

https://youtu.be/n3fwERuvEqI

Romano, Aja. "The Harry Potter universe still can't translate its gay subtext to text. It's a

problem." Vox News, 4 Sept. 2016, www.vox.com/2016/9/4/12534818/harry-potter-cursed-child-rowling-queerbaiting.

Rowling, and John Tiffany. Harry Potter and the Cursed Child: Parts One and Two. , 2016.

Print.

Rowling, J.K., author. Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them: The Original Screenplay. First

edition. New York, NY: Arthur A. Levine Books, an imprint of Scholastic Inc., 2016.

Rowling, J. K., author. Harry Potter And the Sorcerer's Stone. New York :Arthur A. Levine

Books, 1998.

Seamus Gorman. “J.K. Rowling's Decline... (from the perspective of a harry potter fan).”

Youtube, 25 Mar 2019, https://youtu.be/CSXFdb_G4C8

Schott, Christine. “The House Elf Problem: Why Harry Potter Is More Relevant Now Than

Ever.” Midwest Quarterly, vol. 61, no. 2, Winter 2020, pp. 259–273. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=141673717&site=eds-live.

Smith, David. "Dumbledore was Gay, JK Tells Amazed Fans." The Guardian, 21 Oct. 2007,

www.theguardian.com/uk/2007/oct/21/film.books.

Troyka, Natasha. "J.K. Rowling and the Assassination of the Author." Medium, 3 June 2019,

www.medium.com/@natashatroyka/j-k-rowling-and-the-assassination-of-the-author-49a66a756983.

Waters, Darren. "Rowling Backs Potter Fan Fiction." BBC News, 27 May 2004,

news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/3753001.stm.

Wimsatt, W. K., and M. C. Beardsley. “The Intentional Fallacy.” The Sewanee Review, vol. 54,

no. 3, 1946, pp. 468–488. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27537676. Accessed 27 Feb. 2020.

Vezzali, Loris, et al. "The Greatest Magic of Harry Potter: Reducing Prejudice." The Journal of

Applied Social Psychology, 23 July 2014, doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12279.

0 notes