#i think this is what the youth call environmental storytelling

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Here's your regular bird-themed video.

via taylor.munsell

#bird#birb#video#tik tok#parrot#orange winged amazon parrot#i think this is what the youth call environmental storytelling#what with “i bite” being bitten away

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Show, Don't Tell

WaterPomato's analysis of original artwork by @freneticwolf called Pals Just Chillin' about a friendgroup of four spending quality time together

Table of contents

1. Intro to my analysis

2. The flag of a nation

3. Fanatic materialism

4. The troubled youth

5. Hedeonistic youth

6. Concluding thoughts

7. Source to the artwork

Intro to my analysis

Greetings, and let's do this rodeo again. Remember to think before commenting. I'm not an art critic/artist. Are we clear? Excellent! Frencore has made a wonderful piece of art called Pals Just Chillin', which heavily relies on environmental storytelling. And that would be the focus of my analysis.

Environmental storytelling is based on the fundamentals of showing and not telling. We are shown an environment in which we are meant to interpret ourselves. There are different ways to read this environment. For example, a delightful time of friends hanging around. However, I see a more of a darker side~

Please get some drinks, plants, posters, boxes, and cushions... No, we need the guitar, alcohol, and bong to kill time... What do you mean there isn't enough space? Pff, you hear this guy? Just buy it already! Also, I'm having some pals over at some point... No, we won't cause a fuzz... Yeah, yeah, see ya at some point.

The flag of a nation

I might be obsessed with flags because the flag of an unnamed nation is quite eye-catching to me. The first thing to note about the flag is that it's a Nordic flag because of the Christian cross symbol. So, they live in a Christian nation? Maybe? I haven't read Frencore's book, which most likely explores the fictional nation.

Now, what do the blue, orange, and white colours represent in the flag? Well, the white colour hopefully represents peace. Blue represents loyalty, justice, and water in Swedish, Icelandic, and Finnish flags. However, orange is a bit of a mystery for me. Generally, it refers to sacrifice in a flag. However, in this case, I'm not sure.

Lastly, this flag has an intriguing detail. The Celtic symbol of Triskelion refers to the balance between three different affairs; the mind, body, and soul. This detail would advocate for a society based on spiritualism. However, look at the environment. Does that scream of spiritualism? No, it does not. I like to hear the reader's opinion on the symbol.

Fanatic materialism

Let me repeat myself here a little. The flag seems to refer to a nation that values spiritualism and keeping in touch with yourself. However, look at the environment. It's quite the polar opposite because this is more of a fanaticly materialistic society. There isn't any room for emptiness or space because everything in the environment is filled with crap.

What sort of crap is the environment filled with? The answer is products, goods, and foodstuffs. These are typical of a consumeristic society that has more than it needs. For example, there are Joja Colas, a Horizon video game series poster, and a gaming console. Yes, Frencore gets points for the references.

Is this an attempt to criticise our current way of living? You will be reading about it in the upcoming sections. I'm going to point to one example, the potted plants. Don't they look for specific sorts of plants that don't require any water to survive? Hmm? It's as if they are there to fill space and not to be taken care of full-time. Even still, those plants don't look healthy.

The troubled youth

What is Frencore showing us about the youth? For one, do they look happy? The guy on the sofa looks as if he's going through head pain or something with how he frowns with his eyes closed. And don't get me started on the canine on the right. Well, at least the sitting and laying guys look happy... or are they merely distracted by a video game?

They aren't even spending time together. It's more as if they are on islands of their own. They aren't talking, looking, or acknowledging each other. And isn't that the bare minimum for a conversation? It's more that the gaming console, drinks, and the sofa are spending time with them. And this is where I'm wondering if this is social commentary.

Seriously, how am I meant to ignore the fact that Frencore is portraying a moment in which none of them are interacting with each other? It's sad because the title is Pals Just Chillin'... It hits a spot because I see myself as one of those characters. Are we hanging out, or are we merely killing time? That's what I ask myself quite often.

Hedeonistic youth

Oh dear, this section doesn't help at all. The characters are killing boredom by drinking, gaming, and smoking. Boredom is your body's way of telling you to do something. A way to kill boredom is to indulge in liquid, physical, and virtual hedonistic tendencies like smoking with a bong. Note the bong on the table, readers.

And what effect does this have on themselves as individuals? Well, are they even individuals? To me, they seem like non-playable characters that you put on the side to give some artificial life to a video game. Sure, they like gaming, drinking, and smoking, but those aren't deeply personal affairs. What hobbies, dreams, and interests do they have?

Additionally, I couldn't tell about them as a group. They don't seem to hold shared goals, ideals, or interests. And don't tell me that the football and guitar could hint about a shared interest because those look like they haven't been used in years. I'm most likely reading too deep into this artwork that merely has pals hanging around.

Concluding thoughts

Show, don't tell is the heartbeat of environmental storytelling. And honestly, doesn't Frencore give us plenty of material to work with without saying a single word? The environment is filled with material that tells us about the society and people. And that is the beauty of art that I seek. Thank you for reading Show, Don't Tell.

Frencore, is this social commentary on the youth?

Readers, how do you read this artwork?

Source to the artwork

0 notes

Text

Hadestown

First off Hadestown was phenomenal. I legit almost cried at the end; even though I knew there wouldn’t be a happy ending, the musical did such a good job of creating and then destroying hope for the characters. It was probably the most religious experience I’ve ever had doing laundry, so props to that.

All of the songs were bangers, and the casting of the voices was really well done. Orpheus makes sense as a pretty boy with a gorgeous falsetto, Persephone sounds world-weary but has the capacity to harken back to a time of youth and innocence, and Hades sounds menacing without totally getting lost in the maniacal villain thing (except for the part where he yelled about the electric chorus that was a little much).

I love how this version made explicit the parallels between Hades/Persephone and Orpheus/Eurydice, and also how this version gave both women way more depth. This not only fleshes the story out and makes it feel a lot less misogynistic, it also just makes the story better. In the original story, Orpheus was just a stupid musical fuckboy who couldn’t follow orders for more than two minutes. Whereas in this version, while I was still like “why would you look around?” his doubt makes so much more sense. She left him once before, and so its natural and human for him to doubt her loyalty now.

At the same time, Orpheus turning around is extra tragic for Eurydice, who left him because of his inability to provide for her. We get the impression that Eurydice, who was doing all of the hard work, felt neglected materially but also emotionally — he was more focused on music than her. By coming to save her, he proves his love, but his inability to do the hard thing and not look back proves that he hasn’t really matured. The same impulse that led him to neglect food and shelter for his music also preventing him from following Hades’ instructions. So really they couldn’t be together, even if Eurydice had escaped — nothing had changed, they were caught in a cycle.

That cyclic feeling to this story is obviously thematically in conversion with Hades and Persephone, which is so cool and deepens the story. It also redeems the musical as a musical. From experience, it’s hard to practice and perform a musical over and over again if there is no sense of redemption at all, and if you don’t fundamentally enjoy the story, the characters, and the themes. The closing song, with Hermes talking about how it’s the same song, and we sing it over and over again, hoping it’ll change even though we know it won’t, is conversation not just with the nature of myth and storytelling, but also the nature of performance.

Myth and stories are told over and over again, and what Hadestown does it what all good retelling of myth do — they make the same story feel alive and vital again. I knew there wouldn’t be a happy ending, but I felt the tragedy as is if it could have ended another way. That ability to imagine what could have been is, according to Hermes, Orpheus’ true gift. Orpheus is generally just a metaphor for all artists, so it’s kind of also a statement about all art.

What makes this link compelling is the fact that, for the performers in the musical, the have to literally tell this story over and over again, and in order to make each performance good that have to basically trick themselves into thinking it could end differently. That’s just what performing is, being able to replay these emotional beats over and over again and keep them fresh. So Hermes, who addresses the audience and is a really cool meta-textual character (which is stylistically very resonant with the way that ancient Greek poems started with 4th wall breaking invocations to the muses), is also making a commentary about the play itself. The fact that this is a performance is called out, but rather than weakening the story is strengthens it — it calls attention to how this story is an eternal loop of hope and pain, just like the seasons are eternal. So it explains the purpose of the musical in the same way these myths were explained in the past — they both do explanatory work about the world, and the cyclic nature of the seasons, and of love and loss. It’s just more abstract than literal explanatory work (which is probably more accurate to the ancient view of myth, honestly, than an overly literal one).

Hadestown also does what ancient myths did, which is reify abstract concepts in a way that makes reasoning about these concepts easier. Hadestown plays up Hades’ relationship with wealth, and so to me a lot of this reads as an interesting critic of capitalism in the face of environmental destruction. Hades’ constant industrial expansion is destroying his relationship with Persephone, who is emblematic of the natural world. The moments of beauty in this play are all related to nature and the natural — most poignantly, the description of Hades coming to the Persephone in “her mother’s garden,” and sleeping with her (which is an incredible finesse, mixing Christian and Greek spirituality pretty flawless and concisely, wow). A parable about success destroying a marriage that started beautifully is a perfect metaphor for the destruction of the planet by human beings that are uniquely situated to enjoy and appreciate its beauty. That’s the kind of thing that myth is excellent at, casting abstract struggles in personal terms that make those abstract struggles real.

Also, the whole wall thing is even more effective today than in 2016, and like makes the whole Hades=capitalism even more interesting and powerful

1 note

·

View note

Text

URC Youth Assembly (24-26 Jan)

Members of the Yorkshire Synod of the URC Youth (missing: Saskia, Nico) (image source)

I’m going to apologize in advance for the length of this post, and feel free to skim it as needed.

Last month, I attended the United Reformed Church’s Youth Assembly (URCYA) with the other members of Peter’s House, as a representative of the churches we’re working in. On January 24th we spent the afternoon traveling to Whitemoor Lakes Activity Centre via mini-bus, Going from Hull to Leeds (to pick up more people) to Lichfield took about 4 hours. Arriving at 7:30, we quickly ate dinner and then the weekend began!

We started with some icebreakers to get to know our small ��Buzz” group, who we would be discussing the panels with. The main purpose for this weekend, aside from gathering together, was to bring motions to the attention of the Youth, which, if passed, would then move on to change things for the future. The motion we started with was a mock motion, to help us understand how to vote properly and the setup of the different sections (like when to ask questions and when to discuss with your group). After the mock motion we then moved into a worship where we contemplated the things we left behind to attend (For example, I said work). The intentionality behind understanding that we had left some things behind to attend this gathering was very engaging for me, and set a good standard for how the weekend would go. Once worship was finished, we got to go to a campfire (where I broke out the graham crackers and Hershey’s chocolate that I had brought and made a s’more for myself and Ryan (another American YAGM volunteer who was there!)). Bedtime was scheduled for 1am both nights, but I was asleep no later than 11:30pm that first night.

The next morning after breakfast the first of three scheduled Panel discussions followed by a workshop started. This one focused on Politics, and a lot of the discussion circled around what is the role of religion in politics, especially given how intertwined the Church of England and the government are in the UK. Coming into this discussion as an American, I felt that I learned a lot in regards to that specific cultural difference, given that church and state are tried to keep as separate as possible (and, to be honest, my preferred method to run a country, but I’m biased). The discussion then moved over to whether we should be voting in the interest of Christian values, and how we classify what values are Christian. Following the panel discussion, the workshop I had the privilege to attend was titled “Where Would Jesus Sit Politically?” and centred around the types of policies Jesus would back or be involved in today. Some of the ideas that came up were protections for vulnerable people, advocacy for minorities, and better accessibility laws.

After that came the first business session, where the motions started. The first motion presented was to help integrate the use of an app that students can use to help find a local church while away from home, which was passed. Another motion instructed the URC to create a designated “Green Apostle” position to help with the current climate emergency and reduce the overall amount of waste and environmental footprint the URC creates. This motion also passed. After these motions, we got to have lunch within our Synod groups (that meant sitting with the Yorkshire Synod, for me), and got to get to know some of the more local URC Youth a little better.

After lunch and a brief break, we reconvened for the second panel discussion and workshop. This second discussion was on “Sex, Faith, and Relationships,” and to be honest, I was a little disappointed coming out of that panel. The main focus seemed to be on whether sex outside of marriage is fulfilling, and how everyone obviously desires to have a close, physical relationship with someone else. To me, that was exclusionary and at odds with the overall “Common Ground” theme of the assembly. There are people in the world who don’t want a physical relationship with someone else, and there’s others who won’t ever want to get married. I also think the mindset of “sex before marriage is necessarily worse than sex within marriage” is very old fashioned. The workshop I attended after that discussed Gaslighting (and if you’d like to learn more about that, please go here: https://www.vox.com/first-person/2018/12/19/18140830/gaslighting-relationships-politics-explained).

A short break later, and we reconvened to discuss more business. Some of these motions included the formation of a task group to look at celebrating the URC’s 50 anniversary (motion passed) and a letter written to the CTE in regards to their decision to sideline a chosen President Hannah Brock Womack due to her same-sex marriage (this motion also passed, and the letter can be found here: https://urc.org.uk/latest-news/3331-urc-youth-assembly-unanimously-condemns-cte-decision.html). After business was completed, we had dinner and then attended a sensory form of worship; we isolated our different senses to connect ourselves closer to our memories and discover different ways to engage our senses with our faith.

Once this was completed, we came back together to conduct elections (the results of which can be found in the link above). We then got to participate in a Ceilidh, which, to directly quote Google, is “a social event with Scottish or Irish folk music and singing, traditional dancing, and storytelling”. It’s fairly similar to a barn dance, and it was lots of fun. It takes a lot of effort, and I was exhausted afterwards, but getting to participate in the part of the culture here was amazing. The energy in the room the whole time was buzzing, and we ended the Ceilidh by dancing to and singing Auld Lang Syne, which is a celebration of the times we’ve enjoyed together (loosely translated from Scottish, it means [for] the sake of old times). We then proceeded to a late night communion service, which was a deep reflection and very personal. After communion, I think I stayed up almost until 2 in the morning, and most of that time was spent talking to others.

Sunday morning, after breakfast, we started in on our third (and final) panel discussion, on War and Peace. The discussion started off with a quote from a book called The Boy, The Mole, The Fox, and The Horse: “One of our greatest freedoms is how we react to things”. This is something that I think most of us take for granted. People stuck in situations like dictatorship often lose that freedom first. Another discussed topic included whether it is ever justifiable to go to war, and what the line there is. Is it ethical to keep out of war for the sake of peace, when staying out of the war could mean the deaths of millions? If you look at it from a purely utilitarian standpoint, war would only be justifiable if participating means the loss of fewer lives than not participating. Someone pointed out that God is always on the side of the oppressed, in which case people should get involved on behalf of the oppressed. One other point discussed was whether we believe world peace is achievable, and it was pointed out that world peace has to be achievable, or at least believed achievable, otherwise nobody would try to work towards it. The workshop I attended Sunday was on Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories. The workshop was lead by someone who has attended a URC lead trip where the goal was to learn more about the Palestinian perspective in order to enable a better understanding of how to help. I have a lot of thoughts on this workshop (that could probably fill another blog post, so we’ll see), but I want to say just two things: 1) the tour company they used stated that less than 1% of tourists that had used them visited the Holy Land to learn more about the Palestinian perspective. Less than one percent! 2) The person leading the workshop comes from South Africa, and he was very vocal on how similar the situation looks compared to Apartheid in South Africa.

The final part of the assembly was some final business which involved inducting the new URC Youth Executive! After this, the Assembly came to a close and everyone departed for home (although us PEter’s House members and the other TIme for God volunteers stayed at the activity centre because the Time for God BIG Conference started the next day at the same location. Finally, a big shoutout to Ryan (previously mentioned) and Aaron (one of the URCYA Yorkshire Synod attendees) for letting me bother them quite extensively so I could understand everything that was happening that weekend.

If you’ve stuck around this far, thanks for reading! That was quite a lot to write, and if you have any questions please shoot them my way.

0 notes

Text

M: Message from the Trees

Tomorrow (Thursday July, 27th) an important event will be happening here in Durham. Check out Stories Happen in Forests at Motorco at 6pm. (Scroll down for details or click here.) In honor of this event and with apologies for the fact that I will not be able to attend, I am posting an excerpt from my forthcoming book M Archive: After the End of the World that is in the voice of the trees.

excerpt from M Archive: After the End of the World

(forthcoming from Duke University Press 2018)

when they cut us down they found our layers, obvious as orbit. there was the year with the blood in the groundwater. there was the year of the sulfur in the sky. there was the year of bark turned blue with freezing (in the middle) in the middle of july. there was the time we focused on waiting. there was the time we warned them with lines. there was the season of not enough ozone and way too much sunshine.

when they cut us down they found us open to what they easily could have known if they had paid attention to any one of those seasons through which we had grown. we offered ourselves to their breathing. we offered ourselves to their homes. we offered ourselves to their dull admiration, their need for protection, their forehead intuition, the walks they walked thinking they were alone. we chipped into pieces to soften their playgrounds, we bent in strips to ferment their drink. we made every component of their housing except the kitchen sink.

we watched and grew thick with the knowing, we bent with the load of their love. it’s not easy to be resilient when you feel from below and you see from above. we broke in the middle so often we thought we’d evolve past hearts. and we’d offer ourselves for release (but we want to see the next part.)

[i]“Trees remember and will whisper remembrances in your ear if you stay still and listen.” Jacqui Alexander in “Remembering This Bridge Called My Back, Remembering Ourselves”

STORIES HAPPEN IN FORESTS: A LIVE STORYTELLING EVENT

Join Dogwood Alliance at Motorco on July 27th, for an evening of storytelling and community-building in the spirit of forest protection and community justice. The night will feature 10 LIVE true, personal stories.

Our standing forests are awe-inspiring, critical for our well-being and survival, and hold an untold number of tales. Come listen to inspiring storytellers discuss forest protection, community action, and human connection to wild places.

For all you wanderers of the forests, stargazers, lovers of wild places, forest defenders, and folks that speak up for your community, this night is for you.

Tickets will be a suggested donation at the door for $10. Donate $10/month for a special “Forest Defenders” t-shirt and membership.

Visionary storytellers include: – Gary Phillips, poet laureate of Carrboro – TC Muhammad, Hip Hop Caucus – Dr. Thomas Easley, Forestry professor and Center for Diversity at NCSU – Reverend Leo Woodberry – Danna Smith, Dogwood Alliance – Jodi Lasseter, Climate Justice Program Director, NC LCV – Cole Rasenberger, youth activist – BJ McManama, the Indigenous Environmental Network – Margaux Escutin, Bear Afficionado and Durham Activist

via WordPress http://ift.tt/2vJ5lAV

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reading Notes

Ian Bogost wrote a piece in the atlantic, here are some of the notes I took on my second reading, as in-line replies.

A longstanding dream: Video games will evolve into interactive stories, like the ones that play out fictionally on the Star Trek Holodeck. In this hypothetical future, players could interact with computerized characters as round as those in novels or films, making choices that would influence an ever-evolving plot. It would be like living in a novel, where the player’s actions would have as much of an influence on the story as they might in the real world.

Okay straight off the bat that seems a pretty specific definition of story, which requires:

complex characters

Player Influencing plot

“Living in a novel” (which I’ll take for meaning complex simulated environments)

It’s an almost impossible bar to reach, for cultural reasons as much as technical ones. One shortcut is an approach called environmental storytelling. Environmental stories invite players to discover and reconstruct a fixed story from the environment itself. Think of it as the novel wresting the real-time, first-person, 3-D graphics engine from the hands of the shooter game. In Disneyland’s Peter Pan’s Flight, for example, dioramas summarize the plot and setting of the film. In the 2007 game BioShock, recorded messages in an elaborate, Art Deco environment provide context for a story of a utopia’s fall. And in What Remains of Edith Finch, a new game about a girl piecing together a family curse, narration is accomplished through artifacts discovered in an old house.

Okay so environmental storytelling is seen as an attempt at holodecking b/c it allows for rich environments, while artifacts imply or relate the life histories of complex characters, and player has influence in the sense that they move the plot along.

The approach raises many questions. Are the resulting interactive stories really interactive, when all the player does is assemble something from parts?

I think you doing the assembly rather than having someone assemble something for you is still a meaningful difference.

Are they really stories, when they are really environments?

I think I can only answer this when I understand what your definition of story is.

And most of all, are they better stories than the more popular and proven ones in the cinema, on television, and in books?

On this measure, alas, the best interactive stories are still worse than even middling books and films.

I’m a little confused by this standard. In terms of storytelling, are games falling short of the holodeck, or falling short of books and movies? b/c they seem like different questions to me. The holodeck question is about whether games meet the specific criteria to become the dreamed-of interactive movie. If the question is whether they measure to books/films, it’s more about whether games have equivalent ways to express characters and events but not necessarily whether it matches up to a linear, player-involved, immersive environment standard.

In retrospect, it’s easy easy to blame old games like Doom and Duke Nukem for stimulating the fantasy of male adolescent power. But that choice was made less deliberately at the time. Real-time 3-D worlds are harder to create than it seems, especially on the relatively low-powered computers that first ran games like Doom in the early 1990s. It helped to empty them out as much as possible, with surfaces detailed by simple textures and objects kept to a minimum. In other words, the first 3-D games were designed to be empty so that they would run.

An empty space is most easily interpreted as one in which something went terribly wrong. Add a few monsters that a powerful player-dude can vanquish, and the first-person shooter is born. The lone, soldier-hero against the Nazis, or the hell spawn, or the aliens.

Those early assumptions vanished quickly into infrastructure, forgotten. As 3-D first-person games evolved, along with the engines that run them, visual verisimilitude improved more than other features. Entire hardware industries developed around the specialized co-processors used to render 3-D scenes.

Ok so games are kinda doing the complex simulated environments part?

Left less explored were the other aspects of realistic, physical environments. The inner thoughts and outward behavior of simulated people, for example, beyond the fact of their collision with other objects. The problem becomes increasingly intractable over time. Incremental improvements in visual fidelity make 3-D worlds seem more and more real. But those worlds feel even more incongruous when the people that inhabit them behave like animatronics and the environments work like Potemkin villages.

But failing at the complex interactive characters part. True. (Some interesting experiments by SpiritAI and the game Event[0] however.)

Worse yet, the very concept of a Holodeck-aspirational interactive story implies that the player should be able to exert agency upon the dramatic arc of the plot. The one serious effort to do this was an ambitious 2005 interactive drama called Façade, a one-act play with roughly the plot of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. It worked remarkably well—for a video game. But it was still easily undermined. One player, for example, pretended to be a zombie, saying nothing but “brains” until the game’s simulated couple threw him out.

Also failing at the plot-influencing part and emergent events part (but some interesting experiments -- blood and laurels, for instance).

Environmental storytelling offers a solution to this conundrum. Instead of trying to resolve the matter of simulated character and plot, the genre gives up on both, embracing scripted action instead.

In between bouts of combat in BioShock, for instance, the recordings players discover have no influence on the action of the game, except to color the interpretation of that action. The payoff, if that’s the right word for it, is a tepid reprimand against blind compliance, the very conceit the BioShock player would have to embrace to play the game in the first place.

True, this is what 3D games do. But I’d argue that other games give up on the fully simulated environment in order to resolve simulated characters and/or simulated plots. All three of these things are happening they’re just not happening in the same games.

In 2013, three developers who had worked on the BioShock series borrowed the environmental-storytelling technique and threw away both the shooting and the sci-fi fantasy. The result was Gone Home, a story game about a college-aged woman who returns home to a mysterious, empty mansion near Portland, Oregon. By reassembling the fragments found in this mansion, the player reconstructs the story of the main character’s sister and her journey to discover her sexual identity. The game was widely praised for breaking the mold of the first-person experience while also importing issues in identity politics into a medium known for its unwavering masculinity.

Feats, but relative ones. Writing about Gone Home upon its release, I called it the video-game equivalent of young-adult fiction. Hardly anything to be ashamed of, but maybe much nothing to praise, either. If the ultimate bar for meaning in games is set at teen fare, then perhaps they will remain stuck in a perpetual adolescence even if they escape the stereotypical dude-bro’s basement. Other paths are possible, and perhaps the most promising ones will bypass rather than resolve games’ youthful indiscretions.

I love Gone Home but I certainly don’t think it shows the limits of what can be achieved at all, even within this palette of techniques. So far it feels like this article is trying to point out the weaknesses of games trying to holodeck, but Gone Home never felt like an attempt to. It felt like it was trying to glean which storytelling techniques come naturally to games and explore them.

* * *

What Remains of Edith Finch both adopts and improves upon the model set by Gone Home. It, too, is about a young woman who returns home to a mysterious, abandoned house in the Pacific Northwest, where she discovers unexpected and dark secrets.

The titular Edith Finch is the youngest surviving member of the Finch family, Nordic immigrants who came to the Seattle area in the late 19th century. It is a family of legendary, cursed doom, an affliction that motivated emigration. But once they arrived on Orcas Island, fate treated the Finches no less severely—all its lineage has been doomed to die, and often in tragically unremarkable ways. Edith has just inherited the old family house from her mother, the latest victim of the curse.

As in Doom and BioShock and almost every other first-person game ever made, the emptiness of the environment becomes essential to its operation. 3-D games are settings as much as experiences—perhaps even more so. And the Finch estate is a remarkable setting, imagined and executed in intricate detail. This is a weird family, and the house has been stocked with handmade gewgaws and renovated improbably, coiling Dr. Seuss-like into the air. The game is cleverly structured as a series of a dozen or so narrative vignettes, in which Edith accesses prohibited parts of the unusual house, finally learning the individual fates of her forebears by means of the fragments they left behind—diaries, letters, recordings, and other mementos.

The result is aesthetically coherent, fusing the artistic sensibilities of Edward Gory, Isabel Allende, and Wes Anderson. The writing is good, an uncommon accomplishment in a video game. On the whole, there is nothing to fault in What Remains of Edith Finch. It’s a lovely little title with ambitions scaled to match their execution. Few will leave it unsatisfied.

And yet, the game is pregnant with an unanswered question: Why does this story need to be told as a video game?

(This sort of conjures up the idea that game designers sit down with a linear plot and attempt to holodeck it, which I feel is less and less of a thing)

The whole way through, I found myself wondering why I couldn’t experience Edith Finch as a traditional time-based narrative. Real-time rendering tools are as good as pre-rendered computer graphics these days, and little would have been compromised visually had the game been an animated film. Or even a live-action film. After all, most films are shot with green screens, the details added in postproduction. The story is entirely linear, and interacting with the environment only gets in the way, such as when a particularly dark hallway makes it unclear that the next scene is right around the corner.

One answer could be cinema envy. The game industry has long dreamed of overtaking Hollywood to become the “medium of the 21st century,” a concept now so retrograde that it could only satisfy an occupant of the 20th. But a more compelling answer is that something would be lost in flattening What Remains of Edith Finch into a linear experience.

Yep, I would agree with that.

The character vignettes take different forms, each keyed to a clever interpretation of the very idea of real-time 3-D modeling and interaction. In one case, the player takes on the role of different animals, recasting a familiar space in a new way. In another, the player moves a character through the Finch house, but inside a comic book, where it is rendered with cell-shading instead of conventional, simulated lighting. In yet another, the player encounters a character’s fantasy as a navigable space that must be managed alongside that of the humdrum workplace in which that fantasy took place.

Something would be lost in flattening most “walking sims” and narrative investigation games and that’s the experience of space itself, perhaps the most prized thing holodecking adds to stories (after all, if you want to participate in an ever evolving, player influenced story, you could do d&d instead).

These are remarkable accomplishments. But they are not feats of storytelling, at all. Rather, they are novel expressions of the capacities of a real-time 3-D engine.

I disagree. “novel expressions of the capacities of a real-time 3-D engine” are the “telling” part of storytelling.

The ability to render light and shadow, to model structure and turn it into obstacle, to trick the eye into believing a flat surface is a bookshelf or a cavern, and to allow the player to maneuver a camera through that environment, pretending that it its a character. Edith Finch is a story about a family, sure, but first it’s a device made of the conventions of 3-D gaming, one as weird and improvised as the Finch house in which the action takes place.

Such repurposing was already present in earlier environmental story-games, including Gone Home and Dear Esther, another important entry in the genre that prides itself on rejecting the “traditional mechanics” of first-person experience. For these games, the glory of refusing the player agency was part of the goal. So much so that their creators even embraced the derogatory name “walking simulator,” a sneer invented for them by their supposedly shooter-loving critics.

But walking simulators were always doomed to be a transitional form. The gag of a game with no gameplay might seem political at first, but it quickly devolves into conceptualism. What Remains of Edith Finch picks up the baton and designs a different race for it. At stake is not whether a game can tell a good story or even a better story than books or films or television. Rather, what it looks like when a game uses the materials of games to make those materials visible, operable, and beautiful.

Right, so it rejects holodecking and tries to convey character, plot and space according to its own language. This feels like saying games are bad at holodecking, not necessarily bad at stories.

* * *

Think of a a medium as the aesthetic form of common materials. Poetry aestheticizes language. Painting aestheticizes flatness and pigment. Photography does so for time. Film, for time and space. Architecture, for mass and void. Television, for economic leisure and domestic habit. Sure, yes, those media can and do tell stories. But the stories come later, built atop the medium’s foundations.

What are games good for, then? Players and creators have been mistaken in merely hoping that they might someday share the stage with books, films, and television, let alone to unseat them. To use games to tell stories is a fine goal, I suppose, but it’s also an unambitious one.

lol

Games are not a new, interactive medium for stories. Instead, games are the aesthetic form of everyday objects. Of ordinary life. Take a ball and a field: you get soccer. Take property-based wealth and the Depression: you get Monopoly. Take patterns of four contiguous squares and gravity: you get Tetris. Take ray tracing and reverse it to track projectiles: you get Doom. Games show players the unseen uses of ordinary materials.

And if I take a story, shake it up and scatted it all over an environment? Is that the aesthetic form of storytelling?

As the only mass medium that arose after postmodernism, it’s no surprise that those materials so often would be the stuff of games themselves. More often than not, games are about the conventions of games and the materials of games—at least in part. Texas Hold ’em is a game made out of Poker. Candy Crush is a game made out of Bejeweled. Gone Home is a game made out of BioShock.

The true accomplishment of What Remains of Edith Finch is that it invites players to abandon the dream of interactive storytelling at last.

This doesn’t make sense to me. You’ve made a good case that games can convey character and plot well through “novel expressions of the capacities of a real-time 3-D engine”, and you’ve made a case that environmental storytelling doesn’t achieve holodecking, but I’m not going to rule out that other techniques might.

Yes, sure, you can tell a story in a game. But what a lot of work that is, when it’s so much easier to watch television, or to read.

A greater ambition, which the game accomplishes more effectively anyway: to show the delightful curiosity that can be made when stories, games, comics, game engines, virtual environments—and anything else, for that matter—can be taken apart and put back together again unexpectedly.

To dream of the Holodeck is just to dream a complicated dream of the novel. If there is a future of games, let alone a future in which they discover their potential as a defining medium of an era, it will be one in which games abandon the dream of becoming narrative media and pursue the one they are already so good at: taking the tidy, ordinary world apart and putting it back together again in surprising, ghastly new ways.

But this sort of gets why games have stories at all, which is that they are necessities to explain and contextualise the weird things game engines produce. I’d argue that regardless of whether you feel game stories are as good as books, some “novel expressions of the capacities of a real-time 3-D engine” need narrative context to be understood and enjoyed by players. Rapture is less rapturous without its story.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Write Place: Where to Submit Your Work

Looking for the right advice on pursuing the writer’s life? You’ve come to the write place!

by Lisa Hiton

PUBLICATION SENSATION

For many, being a writer involves that ever-strange relationship between unknown readers and your work. You may never meet the people who’ve read your work or know what they think about it. After all, you’ve been that reader, falling in love with sentences, learning to empathize with the harshest of villains, and feeling that a protagonist in a story is a real friend of yours. There is a great power in the mystery of that intimacy, all fabricated from a writer’s mind and brought to you in the form of a printed or digitized page (or in some cases, as an audio retelling).

The point of writing is the writing itself. But after a lot of practice and knowing when a story is finally finished, there is an impulse to share stories. This impulse is human. We tell stories at our dinner tables. We go to the theater or the movies on the weekends. We listen to podcasts. We sit around campfires in the summer. All of this to dedicate time to thinking about being human. Storytelling is a form of entertainment, yes, but the shared experiences of stories–whether it’s reading a book in a classroom, seeing a story unfold on a stage or screen, or gathering at a dinner table–have the power to transcend history and time, to change us as individuals and communities. And so that impulse to share our work as writers is not just about fame or the permanence that comes with publication, but to participate in that grand collective of human consciousness.

As discussed in last month’s blog, you’re now ready with a cover letter and a piece of writing or two that you’d like out in the world. Now it’s time to figure out who might love it as much as you do and give it a space in the world of their magazine.

GETTING ORGANIZED

First you’ll want to get organized. The life of a writer is not an easy one. You’ll need to be prepared for overwhelming amounts of hard work in the forms of reading, writing, thinking, and imagining. You’ll also need to be prepared for hardships. Writers deal with rejection all the time–rejection letters from magazines, publishers, agents, college campuses. And for the writers lucky enough to get a book deal, there is always a critic waiting to take your book down with skepticism. But the lasting effects of reading and writing are what keep writers going forward. The best thing to do is expect many rejection letters and stay organized as a means to defeat this system of discouragement.

The first thing to do is come up with a way of keeping track of your submissions. You can do this digitally or by hand. I happen to do both. You’ll want to keep a log with pertinent information. It might look something like this to start:

NAME OF JOURNAL | NAME OF PIECE(S) SUBMITTED | DATE OF SUBMISSION | DATE OF RESPONSE | RESPONSE

Here are some recent submission entries of mine:

Denver Quarterly Ancestry, The Houses of Frankfurt, Portrait in a Jewelry Box, 2/23/2016, 12/28/2016 Acceptance

Poetry Magazine Intrusion, Patriot’s Day, Scoring the Death of the Firstborn 7/22/2016, N/A Submission Pending

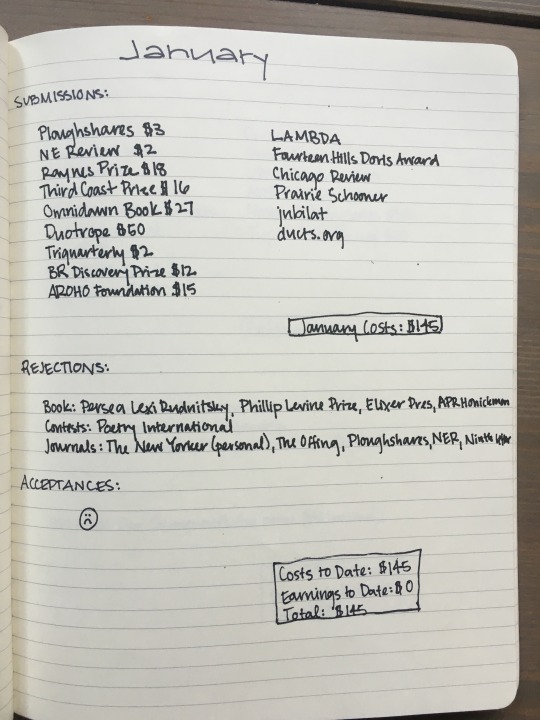

Like I said, this can be done digitally or by hand. Here is a screenshot of recent submissions, which I track using Duotrope:

I also keep a separate log by hand called “Poetry Has Value” which specifically tracks my submission costs month by month. I was inspired to do this after Jessica Piazza’s blog of the same name. Piazza and another poet friend decided to ONLY submit to magazines that paid poets for accepted poems (you poets out there, be prepared to not get paid much, if at all, for your beautiful poems). As you start submitting more work, you’ll see how quickly submissions, contests, and book contest fees can add up! While I don’t exclusively submit to markets that pay for poems, I did want to see just how much I was spending to get my poems and my first book into the hands of publishers (and what, if anything, I was making in return).

Another key organizing factor is to keep file folders of your submissions by magazines. These can by physical or digital. This way, you’ll always be able to reference what you’ve sent over the months and years it might take to get your work in a given magazine. I also keep a folder for submission responses. Otherwise, your mailbox or inbox can quickly become a flurry of papers that you aren’t sure where to put!

WHERE TO SUBMIT

The pleasure of submitting work comes when considering the magazines that might someday publish your work. The easiest way to see where your work might fit is to read lots of magazines and journals. See what you are drawn to and why. Think about if those pages influence your work. Can you get a sense of how the editors put an issue together? All of these ideas might help you figure out the publication path you’d like to take.

Of course, you’re at the beginning of the journey. It would be a pretty wild miracle to submit to, say, The New Yorker and get your work in right off the bat. But even that ultimate dream can be a guiding light to see a path your work might take over time. So let’s say you do hope to be in The New Yorker someday. What about that magazine makes you crave being in its pages? Where else did those writers first publish their work? You might find your favorite writer’s first book of short stories, essays, or poems and look at the acknowledgements page. Which magazines first published those works? For example, Crush by Richard Siken is one of my favorite books of poetry. When I first submitted poems, I looked at the acknowledgments page in that book and saw which magazines and journals first published those poems. I had never read the Indiana Review, but they had published one of my favorite poems in the book. So I took a shot and sent some of my finished poems to them. By some magic, they accepted one of them!

Write the World is made up of all kinds of writers at all stages of writing. Here are some magazines you might investigate based on what you’re working on now:

Adroit Journal: I love the Adroit Journal so much that I’ve become a recent poetry editor for this magazine. The journal was founded by Peter LaBerge when he was a high school student. The magazine is run by high school and college students. You can submit work in the “21 and under” section of the submissions page. Keep up with the Adroit Journal on social media or through their newsletter to hear about mentorship and contest opportunities for young writers as well! They also host an international contest for young writers each year.

Bazoof!: Bazoof! publishes works in all genres by young writers of all ages from all over the globe!

Canvas: Canvas is an online literary space for and by teens. The editorial team of teens accepts work in all genres and in hybrid genres–video poems, audio poems, visual pieces, fiction, poetry, and plays.

Cricket Media: Among other things, Cricket has a group of magazines for young people. Though not every piece is written exclusively by young people, they often take work in many genres by young people. Their magazines are Babybug, Ladybug, Spider, Cricket, and Cicada. These magazines are tiered by age group. Let’s say you have a few haikus that your three year old brother just can’t get enough of. Those would be perfect to submit. They also have branchout magazines that focus on history, science, and the like. The primary magazine for writers 14+ is Cicada. They also accept comic strips.

Ember: Ember is a semiannual journal of poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction for all age groups. Submissions for and by readers aged 10 to 18 are strongly encouraged.

Highlights: Perhaps the most famous magazine for young people sitting in the waiting room of most dentist’s and doctor’s offices, Highlights accepts work in all genres.

Iris: Iris is an online magazine that exclusively publishes works on LGBTQIA themes for teenagers.

Lip Magazine: Publishes articles, essays, short stories, poetry, reviews and artwork on a variety of topics relevant to 14-25 year old females.

Merlyn’s Pen: This magazine was made with teachers in mind. Teachers understand the importance of young readers and writers in our culture. Merlyn’s Pen allows the world to see who teens are through what they read and write. The magazine accepts fiction and nonfiction on topics related to pop culture, media, advertising, and their impact on the lives of teens.

Moledro Magazine: This non-profit, global literary magazine is run by high school students and accepts work of fiction and poetry by teens.

Native Youth Magazine: Native Youth Magazine publishes works by those of Native American descent. More generally, the publication serves as a resource about Native American culture.

Parallax: Edited by the Creative Writing Department at Idyllwild Arts Academy, Parallax is one of the premiere student-run magazines in the world. They accept submissions from high school students all over the globe.

Sugar Rascals: This Canada-based literary magazine published twice a year features teen works of poetry, short fiction, and art. Submissions are accepted from teens all over the world.

Teen Ink: Teen Ink is a cultural magazine featuring writing by teens in all genres–literary and cultural! Publishing categories include: fiction, poetry, art, sports writing, opinion pieces, environmental pieces, health and lifestyle, travel and culture, reviews (books, music, movies, etc.), articles, and even interviews.

Voiceworks: Out of Australia, Voiceworks is a national, quarterly literary journal made up of work by Australians under the age of 25. From fiction, to poetry, to comic strips, Voiceworks relies on contributions from readers.

Write the World: Among other things, we at Write the World publish an annual print journal. We always call for nominations from all writing within the year written by you, dear writers!

There are many more magazines for young writers with different focuses. From history writing, to poetry, to writing by Jewish girls age 9-14, to writers of New England, there is a magazine out there for your work and NewPages is the most comprehensive resource to date for young authors looking for open reading periods and contest submissions–for homes for their work.

SHELF LIFE

The hardest part about submitting work is waiting to hear back from all of these magazines. During the wait time, you’ll want to be reading these magazines and supporting the work of your peers, writing new work, and keeping up with your homework. As you hear back from magazines, be sure to file their responses in an organized fashion. If you get a rejection letter, immediately send a new packet of work to that publication (maximize the number of submissions per open reading period at these places that you can!). And if you get an acceptance letter, celebrate big time! It’s rare that anyone gets work published and it’s important to celebrate your words whenever they make it through the slush pile and into print! I personally like to celebrate by treating myself to a cold-pressed juice and hugs from fellow writers. As I get magazines and journals with my work in them, I keep them all in the same place. Eventually, I hope to have a full shelf of magazines with my poems, and maybe someday a long time from now, a whole bookcase!

About Lisa

Lisa Hiton is a poet and filmmaker. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry from Boston University and an M.Ed. in Arts in Education from Harvard University. Her poems have been published or are forthcoming in Linebreak, The Paris-American, Hayden’s Ferry Review, and LAMBDA Literary among others. Her first book has been a finalist or semi-finalist for the New Issues Poetry Prize, the Brittingham & Felix Pollack Poetry Prize, the Crab Orchard Review first book prize, and the YesYes Books open reading period. She has received the AWP WC&C Scholarship, the Esther B Kahn Scholarship from 24Pearl Street at the Fine Arts Work Center, and two nominations for the Pushcart Prize. Her chapbook, Variation on Testimony, is forthcoming from CutBank Literary. She is the Interviews Editor at Cosmonaut’s Avenue and the Poetry Editor for The Adroit Journal.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Angie Thurston, MDiv ’16, and Casper ter Kuile, MDiv ’16

“The concept of meditation that I have is of there being a spark of God within, and so meditation for me is communion with God. And so, that's something that I do on a daily basis in a set aside way, but is also something that I strive to do all day every day.”—Angie

“We want to tell a different story about American culture, really. There seems to be so much decline, grief, and loss, particularly from a religious perspective, and actually, what we're saying is there's a really exciting, hopeful story about how people are being creative in how to come together and find meaning with their lives and engage in questions of social justice or create beauty or do all of these fabulous things. It's just happening in a slightly different way.”—Casper

Angie Thurston, MDiv '16, is a fellow at On Being, a ministry innovation fellow at HDS, and, along with Casper, the co-author of “How We Gather,” a cultural map of millennial communities. She is co-founder and past president of the HDS Religious Nones and associate trustee of the Urantia Foundation.

Casper ter Kuile, MDiv '16, is a ministry innovation fellow at HDS and a co-host of the popular Harry Potter and the Sacred Text podcast. With Angie Thurston, he is the co-author of “How We Gather.” He is also the co-founder of the UK Youth Climate Coalition and Campaign Bootcamp.

Background and Upbringing

Angie:

I grew up in Boulder, Colorado. Both of my parents were very intentional about cultivating a spiritual home life for me and my two younger siblings, and so we were constantly in creativity mode around the way that we celebrated holidays and the way we had family meetings. Every evening at the dinner table we would go around and tell our days and talk about what we were grateful for. That practice wasn’t necessarily as part of a larger religious community, but it was in conversation with other Urantia Book readers. That was the broader social fabric of my upbringing.

The Urantia Book is a 2,000 page book published in 1955 that tries to harmonize science, philosophy, and religion. I call it a textbook on the universe, because it goes from macro to micro about the way the universe is organized and the meaning of words like God, deity, divinity, reality, pattern, meaning, and value. Then it goes down to the micro of the life and teachings of Jesus, which it spends 700 pages on. It presents religion as the individual's relationship to God and striving to become more useful to others.

Casper:

I was born and raised in England, but both my parents are Dutch, and I had a secular upbringing. In all sets of my grandparents, no one went to church. It was not part of our family's history, even. But I went to a Waldorf-Steiner school. It’s a holistic education model that really stresses the arts and a learning community that sticks together over eight years with one teacher, so you keep a main lesson teacher you have every day in the morning, and you learn to read later because you're learning to act out the letters and all this kind of stuff. I went to that school until I was 10, and it was a very rich home life in lots of rituals and nature-based celebrations around the calendar.

The seasonal calendar was really important and is still really important to me. But then I left and went to a very posh English prep school and then a boarding school, which are obviously both Anglican in their heritage, and I learned the Lord's Prayer and hymns. I joined the Christian Union group when I was 13 because we got a Kit-Kat, and some physics teacher was there and we sang songs. But then it was made clear that that was not cool to be gay. So, I was very anti-religion for a long time, but I was very involved with activism, particularly environmental activism. And then I just kept engaging religion in a different way. First, it was a strategic place of "Look how good they are at telling stories. We can learn from that." Then wondering, "Oh, the bond here that's most engaged are often the more religious ones. What's that about?"

How We Gather

Angie:

I was working on “How We Gather” in a very lonely and meandering way until Casper came along. I was trying to keep track of communities that seemed to be offering people some sort of meaningful experience or belonging, and I was looking specifically outside of organized religion. That was in response to the significant disaffiliation trends that I was learning about and that I felt part of. It made me wonder: Where are all these people congregating if not religiously, and are they congregating at all?

Once we started working together, we had about 25 conversations with leaders in various communities around the country, and by around person 22 or 23 it got to the point of hilarity, because they were doing such different things functionally. This is everything from fitness communities to arts-based community development to you name it, and they were all using the same language to talk about the work they did, and they were all expressing these strange fanatic strands that ran through it. It got to the point where it was almost comical to us, and also seemingly a problem that they didn't know each other and that they didn't understand that they were, in some way, working on the same thing. That was what compelled us to write “How We Gather”—as a sort of invitation to them and to others to notice what we were noticing and to start a conversation about it.

Casper:

We want to tell a different story about American culture, really. There seems to be so much decline, grief, and loss, particularly from a religious perspective, and actually, what we're saying is there's a really exciting, hopeful story about how people are being creative in how to come together and find meaning with their lives and engage in questions of social justice or create beauty or do all of these fabulous things. It's just happening in a slightly different way. We try to see ourselves a little bit as storytellers and to shift the spotlight from congregations that are getting smaller to non-religious communities that are growing.

Angie:

The thematic commonalities that we found boiled down to six things that we saw over and over again. The umbrella was community as the priority and the way that all of this happened, and then underneath that was both personal transformation and social transformation, and then activating creativity, engaging in purpose-finding, and a big one was accountability—holding each other accountable. A large part of our work has been trying to notice and foster that kind of thematic consistency across very diverse, functional organizations.

Personal Spiritual Impact

Casper:

Doing this work has made me want to take my spirituality more seriously. It’s been interesting for me to think about my cultural Christian heritage, and an unexpected gift of this has been meeting all these fabulous bishops and Catholic or Jesuit brothers, religious leaders, or all these just amazing individuals who I have such respect and admiration for, who really model so much of what I want to live out in my own way.

Angie:

Something that I grew up with intellectually and carried here was the idea of seeking truth wherever I could find it. That has been a really imperative part of my spiritual life in large part due the work we're doing together, where we're getting to participate in so much of the religious and spiritual lives of others and to join in that. The invitation has been so open in a really beautiful way—from across a spectrum of belief and non-belief. So, to get to be invited into a community over and over again in different ways and with people, but with a kind of shared spirit of generosity and intention has been surprising, just because every time it happens something new unfolds that I couldn't have predicted. So, that has just been a really fun discovery process and has definitely enriched my own spiritual life.

On a daily basis I guess my version of the millennial cliché with regard to meditation is just in my own language, because the concept of meditation that I have is of there being a spark of God within, and so meditation for me is communion with God. And so, that's something that I do on a daily basis in a set aside way, but is also something that I strive to do all day every day.

Me striving to live love in my daily life is my religion. There is a very cohesive understanding of that and a commitment to this sort of everyday religiosity among Urantia Book readers—at least among those who have decided to sort of attempt to apply the teachings that are in there.

Moving Forward

We're focused on three areas. The first is supporting these innovators, these people who are trying to foster communities—both religious and secular. The second is supporting the transformation of religious institutions. We've been surprised by the level of interest from denominational leaders who are seeing a need for change within their structure and who are coming to us and expressing interest in understanding the landscape that we are studying. We’re working with them to try to adapt to what's happening and to be able to basically give their gifts to the people who are yearning for them. At the moment there is kind of disconnect there that we're hoping we can help to bridge. Then the third thing is sort of public storytelling and a bit of culture change around some of the language that we use to describe religiosity.

What's your favorite thing about doing this work?

Casper:

That we get to do it together.

Angie:

Definitely. We say that every week. I would not be doing this alone.

Photos by Laura Krueger

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apocalypse here: Why Colorado is such a popular setting for humanity’s downfall

In Wasteland 3, the latest entry in the influential role-playing game series, a group of militarized survivors fight through the frozen shells of Colorado Springs, Aspen and Denver during a nuclear winter that makes most blizzards look tame by comparison.

The choice of setting was easy for the video game’s art director.

“We’d done ‘brown and hot’ for two games in Arizona, and we needed a change, so we went with white and cold for this one,” said Aaron Meyers, who lived part-time in Denver during the game’s development. “Colorado seemed like the perfect place to give us that feel and those aesthetics, as well as a wealth of interesting lore and locations to mine for our story.”

Wasteland 3, which was released for the PlayStation 4, Xbox One and PC on Aug. 28, joins a long line of video games that have pictured Colorado as a blood-soaked landscape of zombies, foreign military invasions and robot dinosaurs, including acclaimed, multimillion-dollar earners like The Last of Us, Horizon: Zero Dawn, the Dead Rising series, Homefront, World War Z and Call of Duty: Ghosts.

Even those are just one category in a larger group of novels, TV series, films and comics that have mined Colorado for their apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic stories, from Stephen King’s “The Stand” — which imagined Boulder as the center of humanity’s resistance against a supernatural evil — to “Dr. Strangelove,” “Waterworld,” “Battlefield Earth” and “Interstellar.”

“You can really visualize Colorado when you mention it, even if you’ve never been here,” said Denver author Mario Acevedo, who has written wildly imaginative, urban-fantasy novels starring werewolves, vampires and zombies. “We’re shorthand for ‘mountains,’ but also the type of people who tend to live in the mountains. Scrappy people do what it takes to survive.”

But even as writers and artists paint Colorado with ashen skies, resource-driven riots and nuclear holocausts, the trappings of the post-apocalyptic genre have grown all too cozy in 2020.

Across the U.S., multi-state wildfires, a devastating hurricane, and civic unrest feel like cruel toppings on a summer already larded with misery in the form of a global viral pandemic that has killed nearly 200,000 Americans and left millions unemployed. As the line between depiction and prediction grows almost invisibly thin for post-apocalyptic storytellers, they’ve been forced to turn up the intensity to stand out from our increasingly grim reality.

“Over 40 years of popular culture, a lot of people have looked at what’s happening on a global scale and extrapolated these disasters that end up mirroring reality,” said Boulder novelist Carrie Vaughn, whose 2017 book “Bannerless” won sci-fi’s coveted Philip K. Dick award.

They just didn’t think it would arrive so soon — or all at the same time.

“The only thing that hasn’t happened yet is zombies,” Vaughn said with a laugh. “And I’m not going to make any bets against that.”

Related Articles

Denver leaders had big plans to curb youth violence in 2019, but a pandemic and bureaucracy got in the way.

Safe ways for your kids to socialize during COVID-19

Denver’s “Clone Wars,” “Phineas and Ferb” voice actor on working (from home) through a pandemic

For centuries, apocalypse stories centered around humanity’s punishment from angry gods. That changed after World War II as people woke up to the possibility of global nuclear annihilation. Since then, post-apocalyptic stories and dystopian sci-fi have spread out into every facet of popular culture.

But with the events of 2020, the genre seems to be eating itself from the inside out, particularly as the tropes and clichés of the genre continue to pile up. Is there anywhere else to go?

A perfectly terrible place

Yes, things are messed up everywhere. Few people are immune to the “historic convergence of health, economic, environmental and social emergencies,” as the Associated Press called our “turbulent reality” last week.

But even during good times, popular narratives did not usually depict Colorado as a fun, happy place. Westerns and horror were two of the first genres to capitalize on the state’s isolated, hardscrabble reputation in the 20th century through both novels and films. Harsh winters, brutal landscapes, cabin fever and cannibalism are built into the state’s history — and thus the way people continue to perceive Colorado.

“People who aren’t from here view it as a frontier because it still has this kind of Old West-aura to it,” Vaughn said. “Montana feels remote, but somehow, Colorado is very accessible. You’ve got mountains, prairies and lots of pioneer credibility.”

In fact, the rugged lawlessness and individualism of Westerns, as well as tales like “The Shining,” helped set the stage for today’s post-apocalyptic Colorado narratives, which found their lasting visualization in 1979’s ”Mad Max” and its 1981 sequel, “The Road Warrior.”

But movies such as 1984’s ”Red Dawn” — which imagines Calumet (a former mining town north of Walsenburg) as ground zero for a military invasion by the Soviet Union — also influenced a generation of storytellers.

“I was 11 or 12 when that came out and it was a big favorite of mine,” Vaughn said. “It’s just ridiculous, though. How realistic is an army coming in and trying to occupy the Rocky Mountains? And yet the movie was so iconic that it imprinted on a lot of people.”

Vaughn is a self-described military brat who first came to Colorado when her father was stationed in Colorado Springs. She believes our concentration of military bases plays a big role in the casting of the state. For decades, storytellers have returned to Colorado to visit the command center inside Cheyenne Mountain in Colorado Springs, which has been imagined as both a catalyst for a global nuclear disaster and the last refuge in an irradiated world (see “Dr. Strangelove,” the “Terminator” series, “Jeremiah,” “Interstellar,” etc.).

“I love it because of ‘WarGames’ and ‘Stargate SG-1,’ ” Vaughn said of Cheyenne Mountain’s recurring role in science fiction. “But I got to tour NORAD in high school through my Girl Scouts troop, and again in my current events class, and of course it looks nothing like the underground city you see in most movies. The big blast door, at least, is accurate.”

Some storytellers, such as Wasteland 3 art director Meyers, lean into their artistic license.

“We tend to parody cliché rather than avoiding it entirely, so a few of Colorado’s pop culture connections get a nod and a wink,” he said. “But we didn’t go out of our way to include or exclude any trope based on whether it was well known. If it worked for the story or added to the atmosphere, we put our own twist on it and used it.”

Like Meyers, Wasteland 3 senior concept artist Dan Glasl has lived in Colorado (in the latter’s case, growing up just west of Colorado Springs) and visited most of the iconic areas depicted in the game, from Garden of the Gods to downtown Denver’s Union Station, the Colorado State Capitol and even the former Stapleton Airport.

“We did try to pick locations and landmarks that would be iconic to Coloradans and interesting and visually appealing to outsiders,” Meyers said. “So you can visit places like the Garden of the Gods and the Denver (International) Airport, and see our takes on them, as well as lesser-known places like Peterson Air Force base, and then sillier places like Santa’s Workshop — which is in fact a front for a drug operation.”

Whose apocalypse?

While outsiders may see us a mono-culture, Coloradans know how radically different the conservative Eastern Plains or Western Slope are from ritzy ski-resort towns and liberal Front Range cities. Like Stephen King’s Maine, Colorado is diverse enough in geography and culture to welcome a variety of fictional interpretations.

But that doesn’t mean they’re accurate.

“If you say ‘Colorado’ to someone in the Midwest, they’ll have certain stereotypes about us,” Acevedo said. “And storytellers use that to their advantage. We’re remote enough that they can fill in the blanks and people will buy it.”

Most of these stories don’t reach beyond the history of European settlers as their implied starting points, whereas Colorado’s Native American, Spanish and Mexican history runs much deeper. Until the last century, birth rates in the mountain west were persistently low, Acevedo said, due to the persistently harsh conditions.

That led to constant, life-or-death clashes between indigenous tribes that were, for all intents and purposes, their own versions of the apocalypse. (And that’s not even considering the arrival of European settlers.)

“The Arapaho, Comanche and Utes all had low survival rates,” Acevedo said. “You can’t go to any one part of this land and say, ‘Well, this is the pure, original history of it,’ because everything is folded over everything else. When each previous civilization or society ended, it was truly their apocalypse. You have to look at the history of a people, not just the history of a region.”

For example, few Colorado stories — apocalyptic, western or otherwise — dig back to the Cliff Dwellers of Mesa Verde, whose civilization collapsed near the end of the 13th century due to drought. Despite their essentially Stone Age technology, the Ancestral Puebloans traded with travelers from all over the region and left spectacular marks on their environment.

“The people living in Colorado 1,000 years ago were a lot more aware of what was going on around them than we give them credit for,” Acevedo said. “But with oral history and no written language, it was harder to keep track of things. You could go back however far you want and find an interesting story about some of the early Cro-Magnons coming across the land bridge, and the onset of the Ice Age — that being an appropriately apocalyptic event for them.”

As in reality, not every fictional character is affected the same way by disasters. People with money and privilege tend to see the effects last, insulated as they are from the rusty clockwork of everyday life.

But when a story involves disasters that affect us all — climate change, water shortages, viral pandemics and zombie/alien invasions — there’s opportunity for pointed social commentary and personal reflection, authors say.

“There are 10 million stories about how computing is going to change our lives,” said Paonia-born Paolo Bacigalupi, a bestselling sci-fi author and Hugo award winner, in a 2015 interview. “I think we can have a few more about climate change, drought, water rights, the loss of biodiversity and how we adapt to a changing environment.”

Bacigalupi’s acclaimed sci-fi novel “The Water Knife” imagines a near future in which the Southwest is dramatically remade by clashes over water resources. Bacigalupi was inspired, in part, by watching the fortunes of the rural area he grew up in rise and fall over dwindling water resources.

“I’m constantly looking over my shoulder,” he said shortly before “The Water Knife” was published, “because it seems so glaringly obvious that someone else would be writing about this exact same thing.”

Too real?

Before the title screen for Wasteland 3 appears, players are shown a disclaimer: “Wasteland 3 is a work of fiction. Ideas, dialog (sic) and stories we created early in development have in some cases been mirrored by our current reality. Our goal is to present a game of fictional entertainment, and any correlation to real-world events is purely coincidental.”

The game’s art director, Meyers, declined to answer questions about the reasoning behind the disclaimer, but that’s understandable. Games like Wasteland 3 typically take several years, hundreds of people and millions of dollars to produce. Appearing too topical, or turning off potential players with real-world, political overtones, can limit a game’s all-important appeal and profits.

Legal concerns also trail post-apocalyptic games set in real locations. When the PlayStation 4 exclusive Horizon: Zero Dawn launched to critical acclaim and massive sales in 2017, its publicists pitched The Denver Post on an article exploring their high-tech location scouting, which resulted in stunningly detailed Colorado foliage, weather patterns and simulated geography.

However, game developers would only agree to an interview if trademarked names were not mentioned, given that the studio had apparently not cleared their usage. While The Denver Post declined to write about it at the time, other media outlets ran photos of the game’s bombed-out, overgrown takes on Red Rocks Amphitheatre and what would become Empower Field at Mile High, as well as various natural formations and instantly recognizable statues in downtown Colorado Springs.

That gives Wasteland 3 — which uses elements of parody — some leeway, in the same way that TV’s “South Park” has mocked local celebrities like Jake Jabs, Ron Zappolo and John Elway without getting sued.

“We did have to change a few things here and there, but the references should still be clear to those who know,” Meyers said of Wasteland 3 items like Boors Beer (take a wild guess). “We’re part of the Xbox Game Studios, so there are teams of folks involved in ensuring we have things like proper rights clearances for names.”

Of course, that’s part of the problem in 2020: Bit by bit, it’s beginning to resemble any number of fictional, worst-case scenarios for the collapse of modern society. Competing political factions often label each other as violent cults. People who don’t wear masks have been described as zombies. Police violence and gun-toting civilians are everywhere.

In that way, it’s getting harder for writers and artists of post-apocalyptic stories to stay one step ahead of the news. There’s a creeping feeling that we’ve seen it all before — even if only in our heads. But good writing can be its own virtue, regardless of subject matter, and the post-apocalyptic genre has always stood proudly on the wobbly, irradiated shoulders of others.

“We’re obviously inspired by others and we wouldn’t even be the first post-apocalyptic game set in Colorado, but we have pretty unique sensibilities,” Meyers said of Wasteland 3. “It’s a very serious and dark world, but we put a unique twist on just about everything, and we really enjoy dark humor. You’re going to have brutal ethical decisions to make about life and death, but there’s a lot of humor throughout as well.”

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, In The Know, to get entertainment news sent straight to your inbox.

from Latest Information https://www.denverpost.com/2020/09/02/apocalypse-here-why-colorado-is-such-a-popular-setting-for-humanitys-downfall/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Apocalypse here: Why Colorado is such a popular setting for humanity’s downfall

In Wasteland 3, the latest entry in the influential role-playing game series, a group of militarized survivors fight through the frozen shells of Colorado Springs, Aspen and Denver during a nuclear winter that makes most blizzards look tame by comparison.

The choice of setting was easy for the video game’s art director.