#i think the similarities between radical feminism and 'lesbian' feminism (and the naming of 'lesbian' feminism) encourages women...

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I just want to preface this by saying I know you are not a lesbian, I am not looking to be a lesbian that's on here wanting to circle jerk about how oppressive and cruel bisexual women are, someone thinks I have cruel intentions, I don't, I just want to know more about radical feminism and lesbians. I have no issue with OSA women and their relationships with men. and you just seem to know a lot about radical feminism, so I wanted to ask.

Were there any lesbian radfems, or where they(well known ones) just OSA women calling themselves lesbian?

Radical feminist spaces are just like any other space: there are actual, bona fide lesbians (if you're looking for recommendations?), there are bisexual women who think they're lesbians but will one day realise they're not (there are some well-known examples, e.g. mean-lesbian-something), there are bisexual women who think they're lesbians but who will refuse to acknowledge their bisexuality (there are some well-known examples of this group too, e.g. apparently someone in a lesbian discord server?), and there are political lesbians (who may or may not be actual lesbians, e.g. Julie Bindel and Sheila Jeffreys).

#i don't like the term 'osa women;' i feel it creates artificial links between separate groups to our detriment fyi (like monosexual)#i think the similarities between radical feminism and 'lesbian' feminism (and the naming of 'lesbian' feminism) encourages women...#...to blind themselves to their opposite-sex attraction#anon

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I finally read Jennifer Baumgardner’s Look Both Ways: Bisexual Politics and it’s incredibly eye-opening as a bisexual woman. Every feminist should read it.

I don’t agree with Baumgardner’s ideas at all, strangely enough. The book is very wishy-washy when it comes to bisexuality, excessively trapped in a “gay-or-straight” mentality, extremely embracing of “queer,” casual about porn. It’s far from the usual radical feminist mantra. So why should I praise it? For the first time, a real autobiographical-feminist text has honestly explained the tension between bisexuals and lesbians, as well as been just as honest in the bitter presumptions about “political lesbians.”

It’s felt like a rewrite of history, knowing that those “straight women pretending to be lesbians because they hated men” were actually women who called themselves “straight,” who believed (and some still do) that they were “straight,” and yet met, had sex with and fell in love with women.

Look Both Ways is a sharp reminder of how new discussions into sexuality actually are. The overlap and confusion between “lesbian” and “bisexual” is thanks to feminism, where women who were actual victims of compulsive heterosexuality could be in women-only spaces, genuinely fall in love, and then be so ground down by society and patriarchy that they believed that they had to return to men, that that was their only option. That to be “lesbian” was a political statement in itself, for the actual lesbians who only could ever have sex with and love women, so back then, it was natural for bisexuals - the term never being a widely-used or accepted one - to simply be “lesbians” too. Then, that political anger and sense of personal betrayal from both kinds of lesbians when a bisexual “lesbian” dared to fall in love with a man. The same still happens today. I’ve seen the very same kind of anger and bitterness on Tumblr from a particularly know-it-all feminist lesbian, just because an old lover’s next partner wasn’t another woman, as though she owned her ex-partner.

It was published in 2008 and is extremely dated. Joss Whedon is praised for Buffy and Baumgardner thought that the next conversation would be about bisexuality. How wrong she was, in also casual acceptance of trans women, not knowing what was to come.

She spent her days rubbing shoulder-to-shoulder with big feminist names, studied Dworkin, dared to remind me that Elton John was proudly bisexual until he decided that he was “gay,” and the number of bisexuals who will only use the one-or-the-other. All that, the acceptance of sex-based oppression, then her own thoughts that feminism is more about personal choice, about finding the confidence to act as men do, where bisexuality becomes the “privilege” of somehow looking around and being able to touch all things, and it struck me in that moment that I’d uncovered (for myself) the issue that I have with radical feminism today: the over-reliance on texts from decades ago and a refusal to engage and think and update for today.

Baumgardner accurately states that we’re much more free today than we were in the peak of the second-wave. She hints that it’s not as bad as it actually is, but I agree that it’s a fiction to pretend that we’re in the same battleground as writers in the 1960s, 70s, 80s. A lot of the issues are similar, but they’ve evolved with technology, travel, laws and it’s foolish to think that outdated text books are perfect stand-ins for today. They’re not religious texts and too many “radfems” act as though they are, instead of texts to be read, understood, challenged, and then used as the basis to form their own unique ideas.

Bisexual Politics is an excellent read to see a window into the past. Today, we have better tools at our disposal to point out and recognise oppression. Most of us don’t have the cushy bubble that Baumgardner fell into, her bisexuality exposed and explored under the watchful gaze of feminists and “straight” women who became “lesbians” in relationships with other women.

There are plenty of places to go, and the discussions about sexuality need a serious jump forward. Baumgardner has no strong connection to bisexuality as far as I read, not aside from her relationships with both sexes and being from an age where it was more about “picking a side,” “straight vs gay,” where bisexuality as a sexuality is somehow both stronger an identity and weaker, more concrete and more fluid, more angry and more apologetic, then ever before.

But it’s a good starting point. To go forward, we need to know where we come from.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am Bisexual

I am a black, bisexual ciswoman dating a white, straight cisman, and the fact that he is male and straight are not the reason I am dating him, nor are they a reason NOT to. Pretending though, that his labels don’t factor into who he is as a person would be completely idiotic.

At the end of the day, though, we are dating because we share similar values, we are compatible in multiple ways, we respect each other, and we love each other and are committed to making this work. It is true, that as a straight man, he wouldn’t be open to dating me if I were a man, but it is also true that if I were a man, certain aspects of my personality would change, due to a complex combination of nature and nurture that scientists still haven’t figured out.

Also, there are people from both our “communities” (said very loosely) that aren’t down with “The Swirl” which is only something you get to celebrate if you are extremely privileged and quite a bit into eugenics. We each have racist people in our families, and we both get dirty looks on the street when we’re together for different reasons, but hatred is always at the core of the discrimination.

Loving vs. Virginia was passed in 1967, and it is important to note that The Lovings wanted to be left alone and to live in peace, even though their marriage wasn’t recognized by law and it was a crime, even for white women, to give birth to interracial children. The Lovings only took their case to court when they faced racialized harassment.

To me, it is absolutely terrible that in roughly 10 years, we went to celebrating��“love is love” to now criticizing people for who they choose to date or how they identify. I can’t tell you how many times on this site I’ve seen bisexual women pressured to identify as pansexual to be “less discriminatory” or told in disgusting tones, “Why date men if you can choose to date women?” as if bisexual and/or lesbian were just things you can turn on and off like a light switch.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the rise of radical feminism and AFAB-nonbinary/transmasculine culture has coincided with poorer mental health for women in our community and also with a HUGE uptick in misandry and biphobia. Even gay men aren’t above being “canceled” for so-called “transphobic” caricatures of women, even though men have been playing women in the theatre for centuries, and now, women can play men, too. #Progressive

Honestly, one thing I will say that guys do better than us women (in general, there are always exceptions) is comedy. Yes, men, as a a general rule, are funnier than us. Men are more likely to make fun of themselves, us, and other people, with no mercy, and I honestly think the women/AMAB non-binary in our community-- either the black or the LGBTQ+ one, take your pick-- need to learn to take a fucking joke. It’s not that fucking serious, but the one thing that ISN’T funny is the hideous biphobia, racism, and backbiting I’ve witnessed online and offline this year.

What makes it even more disgusting, is that while I am including AMABs in my roast, I have actually seen MULTIPLE stories of AMABs being excluded from AFAB offline gatherings (DOCUMENTED ON THIS HERE VERY SITE) in the name of “safety” because they are seen than nothing more than a man in a dress.

So, here’s where I lose some subscribers...if a so-called “man in a dress” is unwelcome in your circles, do you REALLY think you have room to fucking talk when a huge portion of you you skirt the line between male and female because you can’t accept your own femininity? So really, are you really “non-binary” or are you just a scared little girls who can’t grow up?

Of course, that isn’t ALL of you, but when the country (as pointed out by J.K Rowling) sees a 4400% in female to male transition (a lot of it with very young girls becoming AFAB/non-binary, many of whom are taking testosterone) while male to female transition rates remain UNCHANGED, suddenly this isn’t a “trans” or a “non-binary” problem, this is a FEMALE problem. Trans people, prior to this huge upswing, made up less than 1% of the population, and that included MtF and FtM transition rates. These rates had remained steady FOR YEARS, so from a purely mathematical perspective this uptick is a huge statistic anomaly.

For years people on the Right have decried the so-called “feminization of boys”, when in reality the “masculinization of girls” is statistically a far more pressing societal issue.

I didn’t want to get this harsh, but this is concerning as a medical health issue, especially because research from the Scientific American reports that lots of young women who report having gender dysphoria end up not being dysphoric about their gender at all, but uncertain about their sexuality [click link]. If I had a quarter for every time a girl who never felt comfortable with her femininity or identified as asexual or aromantic turned out to “just be gay/bisexual” then I would be pretty fucking rich.

I felt the same way. I felt like I was “Not Like Other Girls” and even though I never felt like a man, I often didn’t quite feel like a woman. It turns out that bisexuality, especially in women, corresponds with certain personality traits (aggression, assertiveness, high sex drive) that have been “coded male.” Gender bias in medicine is still responsible for why we don’t have more studies on lesbian and bisexual women, or on women IN GENERAL. As someone who is concerned about women’s rights and the safety of young girls and women, I think it is a HUGE DEAL that modern medicine still sometimes operates on the false assertion that women are just men without dicks and added baby-hosting parts. The effects of testosterone have been heavily studied, but there is SO much we don’t know about estrogen, including why different amounts of it don’t factor into PMDD, PMS, and other reproductive issues, as much as certain women’s brains and bodies responding to it DIFFERENTLY for reasons not fully understood.

To make matters worse, while disparities in treatment based on race are less marked in other areas of medicine, black women still die in childbirth-- especially in the Southern U.S.-- at much higher rates than other demographics. Bisexual and lesbian women are also more likely than straight women to fear childbirth, which can be a huge source of anxiety for us. Even if we choose to undergo it, our anxiety is often downplayed by health care workers. This fear of childbirth can be seen even in bisexual and lesbian women who love children and strongly desire to be mothers. This, as well as the cost of surrogacy/IVF treatments, has been a reason that same-sex female couples often opt for adoption.

Bisexual women, in particular, are also more likely to suffer mental health conditions and be the victims of male-perpetrated domestic violence than straight women and lesbians are. “Straight-passing” doesn’t really seem to provide a shield from that, I hate to tell you.

The very concept of calling someone out for “passing” in an attempt to insult them actually reeks of jealousy and amazing privilege. In the case of bisexual people, it assumes that hiding an entire facet of our identity doesn’t matter and doesn’t take an emotional and psychological toll, because we can “choose” an opposite sex partner. This ignores the fact that falling in love isn’t based on choice, and that the moment we pursue a same-sex partner, we still have to “come out” if we want to maintain a healthy, open relationship with them.

In the case of trans individuals, it assumes that “passing” erasing the fact that you have biological differences (such as typically being unable to parent children) from cis people that might make you undesirable to certain partners. Also, if you are also “stealth” you risk the chance of experiencing discrimination and/or violence if your identity is “discovered.”

As far as being “white/European passing” this also does not erase the genetic and geographical ties you have to your ethnicity and/or country of origin. It doesn’t change the fact that if people start making racist comments about any of your racial demographics, it still hurts, even if you try to hide it.

#i am bisexual#bisexuality is not a choice#love is love#women's rights#end biphobia#tired of apologizing#hate is hate#no more racism#loving vs virgina#exile#cancel me please#gender dysphoria#AFAB#AMAB#no I'm not pan

1 note

·

View note

Text

some vintage bi-antagonism

This excerpt is talking about the German lesbian magazines Frauenliebe (Woman Love), which ran from 1926 to 1930 (and then was published under the name Garçonne from 1930 to 1932), and Die Freundin (The Girlfriend), which ran from 1924 to 1933. (I’ve been posting a few excerpts from this book and others in the past two weeks.)

Karen, editor of Frauenliebe, used sexological concepts of congenital and acquired homosexuality to draw a strict boundary between the two. She argued that anyone seeking same-sex love out of enjoyment of transgression [acquired homosexuality] damaged society and should be "separated from the public." On the other hand, Karen continued, "Same-sex behavior, entered into voluntarily and clearly by both partners [congenital homosexuality], belongs, like every intimate heterosexual behavior, to the realm of things one accepts but does not talk about."[68] Karen also warned aspiring writers to avoid writing explicitly about sexual experience in their stories and essays.[69]

Categorical exclusion shaped a debate in Frauenliebe about bisexuality. Like prostitutes, bisexuals were excluded from homosexual community. Frauenliebe printed fifteen responses to a letter asking readers to express their view on women who had relationships with both sexes.[70] They saw homosexuality as moral and bisexuality as immoral. It was not only movement leaders who wanted to discipline sexual desire in their followers. Letters from readers grouped bisexual women with prostitutes and "sensual" heterosexual women, accusing all of seeking homosexual experiences out of curiosity or sensual desire rather than as an expression of inner character.[71]

Many letters expressed antimale sentiments. Hanni Schulz wanted to protected herself "against loving where a man desires at a same time."[72] her gender binary was clear: women love, men desire. Many responses found the idea of making love with a woman who had just come from a man disgusting. Bisexuality seemed indicative of promiscuity. As G. B. put it, "Pure and upright love demands unconditional exclusive possession!"[73] Bisexual women, to these writers, gave free rein to undifferentiated, therefore male, desire.

Scientific categories enabled the "true" homosexuals to disassociate themselves radically from others who openly flaunted their desire for other women.[74] Marie Rudolf agreed that bisexuals had "nothing in common with our orientation."[75] Cläre summed up the majority view: "Each of us must insist that the type of 'ladies' I described disappear from our ranks, that is, our clubs, associations, and so on. I call on you to have courage; out with them; we lose nothing without them!" Homosexual love was purified through exclusion of those who pursued perverse pleasure. Cläre continued, "These people shall not drag what is holy to us through the mud by their opportunism. We can only use people of value, character and ideals, for whom the girlfriend and women's love is holy."[76] Construction of an acceptable homosexual self required the figure of an other upon whom to project the threatening realities of sexual desire.

Writers also accused bisexual women of greed. Tropes of the prostitute and the pornographer circulated by morality campaigners around the turn of the century had fused sensuality and greed. Denigration of bisexual women along these lines expressed the reality of women's financial vulnerability. When Karen claimed that bisexuals would "inevitably return to a man at some point," she brought into the open the material stakes of the wish to exclude.[77] Women struggling to "make it" independently were hostile to those who seemed to want women's love and financial security too.

Vilification of bisexual women allowed women the opportunity to enter into the classification and definition work of sexology and to create a purified figure of the female homosexual suitable for political citizenship. The "sexual" in homosexual was tamed through strict denial that irresistible desire defined the category. Rejection of prostitutes and bisexuals allowed women to construct "female homosexuality" as materially and sexually pure. As a type, they argued, "true" homosexuals kept desire under the control of the individual will.

[71.] A similar series of harshly condemning letters on bisexual women appeared in Die Freundin. "There must be a selection process from the very beginning to keep out all shady elements, because bisexual women drag our humanity through the mud. Because these kinds of people are only interested in us as long as they find sensual and material satisfaction." S. S., "Unsere Leserinnen haben das Wort," Die Freundin, 4 December 1929. Replies appeared in Die Freundin, 8 January, 26 February, and 9 April 1930.

Marti M Lybeck, Desiring Emancipation: New Women and Homosexuality in Germany, 1890-1933, 2015

I’ve seen some people claim that there was basically no distinction between lesbians and bisexual women until the radical/lesbian feminism of the 1970s, which is clearly false. Although if you think these arguments sound familiar, we might consider the possibility that gay and/or feminist politics repeatedly navigate the same kinds of tensions and become susceptible to same kinds of pitfalls when they emerge out of similar social contexts (e.g. white, middle-class emancipation movements that are set against/within western cultures and discourses, with broadly similar ideas about sex/sexuality, gender, respectability, etc).

I’m having difficulty finding the source now, but I thought I read somewhere that this series of letters was prompted by one woman writing in and complaining about the negative view of bisexuals, or wondering why there was so much animosity toward bisexuals, which might suggest that that some readers of the magazine would have liked to see the topic approached more neutrally. I also found a slightly difference characterization of these debates in Queer Identities and Politics in Germany: A History 1880-1945 by Clayton J. Whisnant, 2016:

When we examine the lesbian debates about identity, it becomes clear that lesbians were much more likely to entertain the arguments about bisexuality than gay men were. In fact, bisexuality was an issue that provoked heated discussion within The Girlfriend, A Woman's Love, and other lesbian magazines. There were certainly some contributors who said that being married or even sleeping with a man once should be enough to exclude an individual from the lesbian community. In the midst of making their point, such women could express some profound "disgust, fury, and hate" toward men, as Heike Schader observes.[145] Many other contributors, though, defended women who carried on relationships with both sexes--either out of true desire, or more commonly because of pragmatic circumstances of social setting or economic need. In letters to the editors, many self-identified bisexual women took an opportunity to tell their own stories of life and love. In them one gets glimpses of how the twists and turns of a life's course can create relationships between numerous individuals in which feelings, desire, obligations, and identities are often difficult and confused issues not easily sorted out.[146]

[145] Schader, Virile, Vamps und wilde Veilchen, 98. [146] Ibid., 96-98

79 notes

·

View notes

Note

rad asks: 3, 10, 16

ah hey!!!!!! thanks for asking 💕💐 sorry this took so long

3. Are there any parts of radical feminism, or beliefs commonly hold by radical feminists that you strongly disagree with?

im actually having a hard time answering this ahshskshdlska i wrote a really long rambly response but i ended up justifying what i was describing as disagreeing with LOL so like. idk no widely held radfem beliefs are coming to mind, sorry im just as disappointed as you are shdkshdlsjds i hope this doesnt sound sheepish or anything. So i’ll say what i do agree with, which won’t come as a surprise to anyone probably.

i’m anti porn, i think porn should be illegal, should not exist and all of it should be destroyed, pornstars should be given justice and compensated somehow for the govt allowing this shit, and all pornographers should be considered lower than dirt and killed publicly LOL. and i don’t feel bad about that, they don’t feel bad about filming rape and selling it, having the pornstars they abuse lie about how they love it when asked. i feel the same way abt prostitutes and their pimps, that paid consent is not consent and pimps can all drop dead.

i’m all for separatism, no it would not stop men from being men, but it would save women and girls a lot of grief, hurt and scarring.

i think gender isn’t real, is used to oppress women and helps no one, and that id rather it be abolished than exist to validate some people who like gender roles, ackshully.

ive been agnostic for a long time; my mom and my brother are atheists, my dad is a deist. but i will sooner believe that the creator of everything is female, having given birth to the universe than a male. A man’s involvement in creation is his ejaculation. No more, no less. life does not begin in the testicles, or you wouldnt see all this anti abortion stuff, you would see more anti male masturbation stuff–if it weren’t mostly about using women as incubators, lol. that being said i’m pro choice clearly.

i am anti surrogacy, for similar reasons. same sex couples should absolutely be allowed to adopt, but no one has the right to have a baby except the woman who can use her own uterus for her own baby. even with infertile women, there is no justification for paying another women to rent out her uterus.

i currently am not vegan but i admire the ideas behind it, and i see the similarities between how animals and women are treated. i do know however that those who are farming this produce are not necessarily treated well either. disclaimer i know literally jack shit about it so i can’t really speak much for it either way at this moment.

i know there are trans identified, detransitioned or reidentified females who don’t like words like “mutilation” to describe the surgeries they have had to remove their breasts or to alter their privates to mimic penises, and while i don’t insist on mutilation being the word used, i don’t see how it is inaccurate and i find it hard to talk about it in a positive light, less i be endorsing that women get these surgeries to ease their discomfort with their bodies. that being said i don’t want tifs or detransitioned/reidentified women to beat themselves up and constantly regret it. it is not their fault that they were made to be so disconnected from their bodies. they did not want that, and with the trans movement there were not a lot of people telling them that there are other ways besides transitioning to deal with these feelings. i don’t see how this can be hard to believe seeing as we call it the trans cult all the time, which is an accurate name by the way.

i like the alternative spellings of woman and women. womyn, wombyn, wimmin, womxn, a mon, wom or whatever it is. i don’t currently use them myself but i love them and i don’t care how “stupid” you think it is. you know whats stupid??? the words “trans woman,” “trans man,” and “nonbinary.” “Cis woman.” yeah ill take wombyn any day rather than agree that i “identify” as a woman for not subscribing to the transgender religion.

political lesbianism is shitty, i understand some straight women don’t wanna be celibate, but dating lesbians to stick it to the men and not because you love that lesbian is selfish i think. if youre bisexual then you are also not a lesbian but by all means be a febfem or just a bisexual who does not fuck with men.

prostitution will never be empowering. make up, nails, impractical clothes, revealing clothes is not empowering, having men think you are sexy or fuckable is not empowering. you are not “doing it for yourself.” “Poly” relationships are not empowering or woke, making yourself more accessable sexually to men is not empowering in the same way that it empowers men to have sex with multiple women.

idk ive been writing this for a million years but thats some things off the top of my head that i know i Do agree with, i know that wasnt the question but i still wanted to say something lol. i realize now this answered multiple questions from that ask post so im sorry if anyone else thought of asking those things that i answered LOL

10. What’s your relationship with the term “terf”?

ah! i do jokingly call myself that occasionally, you can see it right there on my about page. but in all seriousness it’s horseshit and goes to show how narcissistic the trans movement is. I see people, newly self described radfems who haven’t figured out what the point of it all is, who try to say “there’s a difference between terfs and radfems! You can be radfem and trans inclusive!” or whatever. To which I say,

these are not two separate groups. Actual radfems are called trans exclusionary because they don’t think men who identify as women can be oppressed by women, and that having been born as a woman is not a privilege, regardless of how that woman identifies.

radfems aren’t even trans exclusive, really. While there are many detransitioned, reidentified women, there are also many who have transitioned and intend to stay that way, or who are even transitioning currently for their own reasons and comfort, while still confronting their womanhood and how they have been affected or are effected by being a woman in our society as well as how transitioning is dangerous. it’s male exclusive more than anything, and rightfully so. any problems men have are created by other men, and as one user on here put it, feminism should not be “all lives matter.”

i forgot to say this initially but being “trans inclusive” is interpreted by some to mean “trans endorsing,” that being trans is an innate thing just like homosexuality, that brain sex is real, and that there is nothing wrong with trans identified females getting surgeries they don’t need on perfectly healthy genitals, or getting hormones they otherwise wouldn’t naturally have that have life altering side effects. otherwise i would be called trans exclusive. LOL. so it really does not mean anything, ultimately.

16. How do you feel about the terms TIF/TIM?

i think they’re great. it says exactly what it means. it is much more appropriate than trans man or trans woman, and it makes it easier to talk about them with a little less word salad. the term trans man others tifs from females, and the term trans woman others tims from males. this is problematic. there is nothing differing tifs from females and tims from males outside of the fact that they are trans identified. the only differences they may have are if they have surgically and or hormonally transitioned, but it is not enough difference to make them the opposite sex, nor does it erase male or female socialization, and the benefits or consequences of being a man or a women, respectively. i worded this a lot better when i saved this draft last but tumblr seemingly ate it LOL so thats a drag. but yeah. tif/tim is great. i don’t think it should be offensive, there is nothing insulting or cruel about it. at best it is “invalidating.”

thank you for sending me these!!!! i’m sorry if my answers were unsatisfactory or hard to understand lmao i edited a lot of fluffy blabbering out of my responses believe it or not. i hope you’ve had a great day and that you’re having a lovely night 💌🌻😊

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ace Discourse, Here We Go

So. *rubs hands together* I decided it’s time for me to break into the discourse. Largely inspired by recent happenings on @highkingfen‘s blog. I’m going to bring some theory into this so we can understand why people are so invested in this.

But first, since the first line of attack always seems to be aimed at people’s identities, I’m gonna go ahead and state mine right now: I’m transmasc nonbinary, gray aroace, and sensually, aesthetically, and platonically attracted to all genders. I’m also not able bodied, so I want you to understand the physical toll getting involved in this debate means for me, so that you know I am invested in this discussion. I apologize in advance for any errors, although I think I caught them all. (Long post, so I put it under the cut)

I will use queer in this post because I am queer.* Let’s start with some basic politics of sex, then work our way into queer politics, and then bring it back around to aceness.

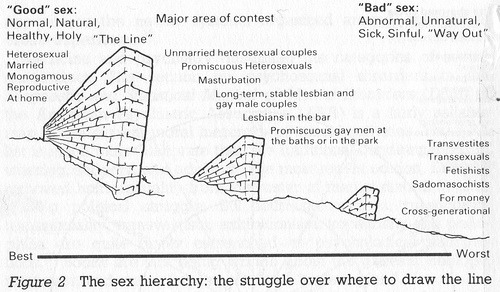

In 1984, anthropologist Gayle Rubin wrote an essay called “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality,” in which she argued that feminism could not take on sexuality theoretically or politically (she was writing in the midst of the feminist porn wars), but that we needed a distinct politics of sexuality. The part that strikes me as most relevant here is when she describes her theory of the sexual hierarchy.

(While this does not include asexuality, it is fair to say that asexuality can fall behind some of these walls too, because it is not accepted. Underlying the category of “good” sex is the assumption that people will be having sex, so asexual people are a threat to this social order that requires that people have “good” sex to reproduce itself.) I highly recommend you read this article, but I am mainly using it here for the visual. Walls are high, and I would say most people cannot just scale a wall all by themselves. So the way we get around this is to throw each other under the bus, to mix my metaphors. In order to cross the line into “good” and acceptable behavior, people have to step on others, push them further down, to advance themselves (instead of, say, just destroying the walls). It looks a little like “we’re exactly like you, we just love each other, we want to get married, we want to be normal. They’re the ones having public sex, turning tricks on the streets, flaunting their sexuality, etc.”** Anything that buys into the normative narrative gets you a little closer to the “good” side of the wall.

Now, I’m sort of rambling, but I promise I have a point. That point is that while asexuality may seem diametrically opposed from Rubin’s list of “bad” sex, it actually is theoretically and politically very similar. Society needs people to have sex to keep itself alive, but it just wants people to have the “right” sex. In a biopolitical way (see part five of the book linked), queer sex is just as threatening as no sex at all. The state is highly invested in controlling their population and regulating its function. This is why "Hyposexual Desire Disorder” appears in the DSM IV (It now appears split into separate disorders for males and females, which I won’t even get to, and now contains the caveat that it isn’t a disorder if someone identifies as asexual). So, improvement, right? Not quite. It still fits into the long history of queer identities and people being pathologized by medical and psychiatric authorities. Our cultural institutions acknowledge the danger asexuality poses to the social order alongside its other queer counterparts.

So, I’m counting that as my theoretical evidence that ace people belong in the queer community and moving on a little bit. One of the critiques I see of including ace people in the community is that asexuals aren’t discriminated against enough to be counted. First, see my very brief discussion of pathologization above. Second, the “cishet asexuals pass as heterosexual, so they don’t experience oppression” argument misses the point. I assume most people in this community understand why heteronormativity hurts. The assumption that you are straight when you’re not hurts. And that’s exactly what this is. The assumption that you’re straight, and that you are sexually attracted to people. And it hurts, except now it’s our supposed community that’s telling us we’re straight even after we say over and over that we’re not. Asexual is by definition not heterosexual. Three, the microagressions: lol you’re asexual, does that mean you reproduce like a plant? Don’t worry, you’ll find the right person some day (remind anyone of “but wait how do lesbians even have sex?” or “don’t worry, you’ll find the right (‘opposite’ gender) one day”?). We can acknowledge that microagressions are bad in other areas, so why can’t we admit that it’s true for ace-spec people too? Four, “corrective” therapy and/or sexual assault happen to us because of our orientations too. Even though I could go on and on, I’ll stop there. Just check my “ace discourse” tag for more. Or don’t. It’s exhausting stuff.

Another critique I see is that this somehow plays into the desexualization of gay people. People who are attracted to their own gender will be hypersexualized or desexualized by straight society as their politics call for.*** It is not asexuals’ fault that people cannot conceptualize the difference between asexuality and desexualization. Asexuality is an identity. Desexualizing someone is an act of perception and political understanding.

Additionally, asexuality is newer (not in concept, but in public visibility) than other queer orientations, and yet no one seems to want to remember that each of those past orientations had to go through the same thing, fighting to be seen as real and not pathological or unhealthy. Sure, we don’t have a legal fight in the same way that homosexual and trans people do, but that is mostly because a lot of people have no idea we exist. I’m going to point you to AVEN for an asexual history, because they’ll do a much better job than me.

Finally, simply this: it is not your job to decide who counts as queer “enough” to be in the community. Another thing we tend to forget when having this argument is that identities shift all the time. It’s politically important when dealing with the straight world to be able to say “it’s not a phase!” But sometimes, your identities shift, and that’s okay. I thought all sorts of things about who I was before I figured myself out, and I’ll probably end up somewhere a little different from where I am now. It is not so cut and dry. People can come out while they’re still questioning, and then realize that they were wrong and are really something else. Some people can be solid in an identity for years, and then start to think maybe there’s something more to it. And that is okay. What’s the point of saying we’re queer if we are just recreating the exact same structures and hierarchies and expectations that we faced in straight society? There is no need for gatekeeping here. I realized I was ace only two years ago, and started to question whether I was aromantic only a year ago. And guess what. I’m still not entirely sure who I am. But that’s fine. It’s okay to explore yourself. You don’t have to be locked into one category forever. Asexuals are not straight, and they are and should be welcome in queer spaces.

*While this should probably be covered in another post, I want to point out how intentional my use of the word is. Queer and LGBT are different concepts, in my mind. See my “queer discourse” tag for some history and theory that others have contributed. Also, read Queers Read This! to get a sense of the approach I take. For now, I will just say that queer has a historical and political meaning that grew as it diverged from the lesbian and gay movement (which was half-heartedly tacking the B and the T to the end of their name) in the ‘90s. Queer as a concept has a much higher capacity to be inclusive of ace-spec identities, because it defines itself and prides itself in its difference from the norm rather than its attempts at being normal. **For a much better discussion of this concept than I can provide here, Michael Warner’s book The Trouble With Normal is excellent, and I highly recommend it.

***Besides, the mainstream movement intentionally desexualized themselves to be acceptable to the straights. The more mainstream turn in our politics was essentially to de-sex gayness. That’s where things such as “love is love” and the gay marriage court cases came from. These were very effective political attempts to play into the normative “good” sex narrative, and distance themselves from all those bad queers doing the things on the other side of Rubin’s walls. Again, I’m going to point you to The Trouble With Normal, even though it’s almost twenty years old, because it just so brilliantly addresses all of this.

ETA: Michael Warner does talk about sex as being essential to queerness, specifically because he is writing his book in response to the desexualization of gay politics. I do not read this as an argument that asexual people aren’t queer, because I don’t think he is trying to account for our existence in this book, and it seems likely that he wasn’t thinking about us at all (which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, because it’s not what he set out to do with his book, and I’m fine with that. You’ve gotta narrow down your scope to something manageable, and he already has a huge topic to address).

#long post#ace discourse#queer discourse#queer#ace#e's endless rambling#i'm tired and in pain#but i had to get this out of my system#I'm too exhausted for this bs#gatekeeping#happy pride month everybody#with just a hint of sarcasm#and frustration#i don't know if any of this made sense#but i hope it does something meaningful for someone somewhere#aromantic#asexuality#asexual#The Discourse™

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Tumblr Changed My Feminism

When I first joined tumblr, it was refreshing, finally I had a place where I could discuss the issues I have experienced being a woman, a place where there were like minded people and a sense of community. I found other women in similar situations as mine, who helped me see just how abusive my relationship was, women who were there for me and helped me work through my issues so that I could see clearly for the first time, it helped me become a stronger woman. But, then things changed, immensely. It started when I saw a 16 year old mutual who was a rape victim by a trans woman being told to die cis scum because she discussed the idea that trans women experienced male socialization prior to transitioning. I defended her, and stated no one should be sending violent threats to a minor, especially a minor female who has endured trauma.

So then I was attacked, told I supported violence against trans women, that I shouldn’t care if death threats were sent to her because she was a terf. This was the first time I came upon that term and as soon as I heard it I panicked. Me? A liberal feminist who has always supported trans right? A terf? I did everything I could to distance myself from that label and I stopped speaking my mind, stopped following my instincts because I didn’t want to be seen as a bigot or hateful. The next controversy with this blog started when one of my first mods Lily, who is a lesbian, got real pissed that people were telling her she needed to give penises a try. Lily never held her tongue, not online, not in real life, she was a very vocal activist who never backed down, so she said what she wanted about the subject. I am ashamed to say that I was not as strong as Lily. I saw the backlash she got and I apologized for it, and removed her from the blog. I regret that decision immensely, I helped to silence a woman because I was scared of how it might blow back on me. I am sorry Lily, you shouldn’t have been no-platformed like that. Then came poor Kharvi, what that girl went through to try and help me out was ridiculous. I brought her on as a mod and told her to look through the blog, our tag, similar blogs etc…. This resulted in Kharvi going to a blog of a person who will not be named who I had argued with in the past because I took umbrage with being called a uterus bearer. Well apparently this was the most horrific act that could have been committed and I got called an abuser, an abuser, because a mod….looked at a public blog……on a public sight. Looking back now I can’t believe I even entertained the idea or apologized, it’s just ridiculous. To throw around that label, to call out your followers to attack others, not just me but the other mods here who had nothing to do with the situation, it was a mess. I am not a person who handles conflict well especially at that time because it was the start of my divorce. So I did everything I could to try and “prove” that I was not an abusive person when really I should have just laughed at the ridiculousness of it and moved on. Kharvi eventually left as a mod because she too, got ridiculed for saying she didn’t want to have sex with someone who had a penis, what a horrendous thing for a lesbian to say right? So then came the terf lists and my followers receiving anons from people telling them how horrible I was and abusive. Then came an entire blog of “receipts” detailing all the things myself and my mods have said or done that they considered heresy against all that was right. My inbox was flooded with people telling me who I should and should not follow, listen to, reblog from etc.... I stopped talking, stopped expressing myself and second guessed every word that I wrote. My haven, the place I found that finally helped me find the strength I needed to leave my abusive ex, was gone. It had become toxic and scary and I couldn’t deal with the amount of hate and failure to think before they acted bullshit that was going on. So now that I had nothing to lose really, I started to allow myself to explore different factions of feminism, and I found the radical feminists. At first I wouldn’t let myself admit that a lot of what they were saying made sense, I didn’t want to be associated with “those” people, the horrible hateful terfs, but the more I read the more I found myself agreeing. The concept of swerf for one, I cannot wrap my head around in the slightest. Do you have any idea how damaging it is to women as a whole, to silence the voices of those who speak out against the sex industry? To those who are brave enough to tell their own experiences with abuse, trafficking, prostitution, who bravely state that the industry is toxic and killing us. Swerf, give me a break. Criticizing an industry does not mean criticizing the women who participate in it, the amount of non-critical thinking it takes to come to that conclusion is astounding to me. It’s yet another term used to silence vocal women, because we didn’t have enough of them already right? So then came gender, gender roles, male and female brains, and what it is to be a woman. Listen, I have no issue with trans people, I support them, I think they should have all the rights and safety that any other person should have, but gender is learned not innate, it isn’t in someone’s lady or man brain, it is a set of rules society has imposed against us and is harmful to women and men. Being a woman is not something I can opt out of, I am 39 years old, I have been socialized as a woman, and even if I transitioned now and presented as a man, my womanhood would not disappear, there are just too many female specific experiences that we endure, that make us into women, that shape our personalities, there are too many to ignore and pretend that trans women have gone through the same things. Trans women have their own specific experiences they have had to endure, their own oppression and violence and hate, they need our support, but that cannot and should never come at the expense of silencing women using fear. There are plenty of trans women who don’t support the cotton ceiling rhetoric, who acknowledge the difference between being a trans woman and a cis woman, and they are labeled terf as well, and if that doesn’t show you the ridiculousness of that term and how it has no meaning, I don’t know what will. don’t support violent threats or hatred towards anyone, I don’t support anyone who wants to take rights from trans women or cis women, but I don’t support silencing anyone either. Sex specific oppression is a thing people, females throughout history have been controlled, abused, looked down upon because of our ability to carry children and our anatomy, this is not debatable and I won’t entertain any discussion that says otherwise. So that’s where I’m at. I don’t care about losing or gaining followers anymore, I don’t care what lists I get put on on this microblogging hell site, I don’t hold my tongue any longer. I don’t know if I’m a radical feminist or what wave I belong in, I don’t believe in labels because my opinions vary, I just know I am a female, I will speak about my experiences being so in the terms in which I wish to speak about them, I will do my best to listen to others and stay open to changing my mind on things, but the one thing I will no longer be is scared into silence, I’ve endured that quite long enough in the real world, I’ll be damned if it happens here too.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Isn’t Gender Nihilism?

Gender Nihilism, as a means of thinking, develops a specific aesthetic of critique that situates itself in opposition, that relies on articulation against and through a structuring of gender that is external to the text, one that is elaborated upon and explored through certain poststructuralist modalities, but largely remains unremarked upon specifically because to do such would be to imply a certain ontology of gender beyond that which the manifesto specifically means to do away with.

Gender expression as related to nihilism of gender is not useless but rather without the meaning by which a gendering of the body takes place. It is through an assemblage of both phenomenological ontic qualities, qualia of womanhood, and a process of relating to others or to the Other that structures womanhood, that creates one as a woman. This reflects notions of a continual becoming-woman, but goes further in an importantly distinct fashion, due to the means by which it signifies the larger structural importance of womanhood not as merely a situation, a structure which one becomes, but in fact that it is defined in and through process, that the violence of womanhood is its most prominent qualia, and that the way in which relating to this violence is specifically realized in relation to structures such as transness and lesbianism allows for the further articulation of womanhood in relativity, through a dispelling of the ontology of womanhood through both a primary relating of womanhood in a structuralist sense and a move toward specifically, indelibly poststructuralist modalities within considering the possibility of womanhood as such, after the raising of this Nihilism. After Nietzschean pronunciations on the Death of God, one must justify God if one is to imply a presence or even lack in its place. Conversely, no such suggestion of lack is made through the manifesto, but rather a rearticulation against the creation of lack necessitated by other ideologies of gender abolition.

In Nina Powers’ analysis of the Gender Nihilist Anti-Manifesto, she acknowledges that the process of gendering is largely feminine, and while it is not exclusively such, that gendering in relation to colonial ideology can serve multiple purposes is part of its multifarious character. The coloniality of gender, as described in the writing of Lugones, is something that has been unduly downplayed in its influence on the manifesto, and moreover is more explicitly present in earlier drafts of the text. That gender presents itself as a specifically colonial stration, that it is evidentiary of a creation not only of the colonial but of the subaltern (and thus through this what Spivak describes as the shadow-of-the-subaltern in which women lie) and that the means by which gender operates, the becomings of gender, are in fact punctuated through their relation to coloniality. That norms of neocolonial transfer are adapted to structures realized through gendering of the body is part of what makes gender colonial, but moreover that there is the primacy of colonial dominance, that the very structure of gender cannot be recognized without first understanding it as eventually sublimating itself into a larger structuring of white supremacy, of capitalism as the articulatory system of colonial exchange and the vital force which underpins colonial power.

Accusations about the Anti-Manifesto ignoring the coloniality of gender come, in many ways, from a confusion about the way in which sublimation through the naming of the cultural as an easily understood but moreover objectual relativity for the colonizer shapes the realization of gendered violence. Ignoring contingency within the hegemonic conditions of articulating gender specifically strengthens this notion, in that it leads to the understanding of roles within the social, articulatory bodies that have been gendered at certain points, as bodies which are sublimated entirely by gender, just as all relations are sublimated in the Deleuzean concept of capitalism. Capitalism is the nightmare lurking on the edge of all of woman’s earliest fires, and it was in this moment that she was makred as a woman. The importance of this similarity, the affinity between the two realizations, is that not only does it lead to the understanding of gender as a contingent structure based within capitalist articulations of violence, but that defense of a structure that has been gendered must not be done as part of a reactionary means of reclaiming the definition of the self from the colonial. This does not sufficiently change the body at hand, the body that will be already contained within the structural articulation in progress, as it necessarily evokes the traumatic Oedipal structure with which gender is first articulated. In effect, it reinserts the colonizer into the definitions held by the anticolonial effort. Thus, a becoming-woman in this sense is defined because it neccessarily is becoming a woman that has been noted by the ledger of capitalist control, articulated in an arboreality of womanhood. That there are differences (and processes of differance) between structures leading to the realization of womanhood (or any other gendered state) does not collapse them by necessity into these arboreal hierarchies, but that the becoming-becoming-woman that results is assured by the colonial nature of gender as articulatory process.

The Anti-Manifesto is vitally understood as a radical work because it operates through a sort of metapolitical means, displacing the way in which gender is largely defined in order to open up not a lack, but a specific questioning of the structure at hand. It is for this reason that I specifically elaborate upon it as meaningfully poststructuralist: while there is plenty of structuralist feminism to be realized and already-realized through claims made within or adjacent to the Anti-Manifesto, the Anti-Manifesto itself relies specifically on a divestment from these claims and moreover a process whereby the contingency of structures, the way in which the structures interact through knots of rhizomality in order to retain larger arborealities is paradigmatically important to understanding gender nihilism as a course of thought. Effectively, rather than taking any single definition of gender as even particularly important, it displaces the means through which these structures are imposed in order to question the relationships that necessitate them, in order to enter a profound refutation of lack and in fact embracing of the ontological in-itself as a necessity for a larger process of anti-ontological thought, of being able to examine gender as part of elaborating upon modalities of examining the political, the social, the striations of race and even the particularities of class given the hyperrealities of the first world and the neocolonial deprivation of the third world.

In a practical sense, the Anti-Manifesto is not a complete work, nor should it be assumed as one. It is both a relic of a certain means of articulating transness, and part of realizing a certain discursive possibility regarding articulatory processes of gendering and striation that present intriguing genealogical and archaeological possibilities given the proliferation of thought based upon it. The value of the Anti-Manifesto is, in effect, that it is not a manifesto, and perhaps not much of anything at all.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflection: The Third Way

This commonplace blog is a collection of ideas and powerful women who have informed my learning about feminism and religion/tradition. It was valuable to me to learn about a third way (not one, but any and all alternatives) outside of the dichotomy of religion and progressive thinking. I have always believed, like many, that the two are mutually exclusive. Using some examples from the class and some examples from my own research, this blog will explore many different ways of thinking about a third way.

First, I found myself incredibly influenced by Kavita Ramdas’ TEDtalk, Radical women, embracing tradition. I had experience thinking about faith in this way, mainly from other academic studies of religion, but never the traditions of a nation. For instance, Le Zbor, a lesbian folk choir, who sing traditional songs while advocating for the acceptance of LGBTQ+. This is a fantastic example of arts activism, similar to how Lin Manuel-Miranda’s Hamilton advocates for equity, diversity, and inclusion for BIPOC in theatre through a piece about American history. Both of these pieces look at a tradition that has excluded them in the past and make it their primary focus. In doing this, they expand the reach of their message to the people who need to hear it most- the older generations, who are the most likely to hold prejudices against LGBTQ+ people and BIPOC. Le Zbor talks about how they sing Christmas songs despite the fact that the Catholic church has strong beliefs against homosexuality, because they as a group are open to religious practices. Here, we see that it doesn’t need to be a choice between religion/tradition and progressiveness. Art is a living thing that can change with time, just like people.

She also spoke of Sakeena Yacoobi, who leaned into Muslim beliefs on the importance of literacy to further her mission of education for women and girls, a mission that has but her on the Taliban’s hit list. Cherry-picking from the same book has lead to women’s oppression (this is referring, of course, to the situations in which women do not have a choice in their religious expression, and men are enforcing sexist policies through religion and government), which makes her religious reasoning behind education that much more powerful. She serves as an incredibly important example of how a woman can choose to be Muslim, veil, and use all of these things to act in the name of women’s rights. In Ramdas’ talk, she recalls Yacoobi’s words, "This headscarf and these clothes give me the freedom to do what I need to do to speak to those whose support and assistance are critical for this work. When I had to open the school in the refugee camp, I went to see the imam. I told him, 'I'm a believer, and women and children in these terrible conditions need their faith to survive.'" This is a third way. Though it is more religious leaning than a lot of alternatives to the religion-feminism dichotomy, it is still a way of creating a space in which the two are not mutually exclusive. Through embracing the tradition of veiling, Yacoobi is getting into spaces she wouldn’t otherwise, and creating real change for women.

Leymah Gbowee, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, organized a group of women in Liberia (Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace), embracing the traditions of both Christianity and Islam, to protest against the civil war and call for peace. She had them all wear white as a way of calling attention to themselves, because the tradition in Liberia is to wear bright, beautiful colors. She purposefully broke tradition to cause a stir. In her TEDtalk, Ramdas talks about how when a senior officer approached Gbowee, she started to remove her headscarf, which caused the officer to get embarrassed and leave. In Liberia, it’s a commonly held belief that if an older woman undresses in front of you by choice, then it leaves a curse on your family. She used that belief, and that tradition, to advance the issue at hand- peace in Liberia. Though the belief itself might be something sexist (why only if the woman chooses to undress?), the act of her leaning into it was empowering.

For another way of looking at religion, I did some research into feminist interpretations of the Bible, and found a book called “Postcolonial Feminist Interpretation of the Bible” by Musa Dube, a Botswanan feminist, theologian, and scholar. I was excited to see such a straight-forward and relevant title. I didn’t have the chance to read the book because there was no way I could order it and get it in time (who still uses Amazon, ew!), so I read some reviews and summaries of it. She critically assesses the stories of the Bible, not only re-interpreting the messages, but also noting when it’s characters act in ways that encourage colonialism or sexism. Through her work, she allows Christians to take a third way and believe their faith while also thinking critically about the things they learn. It creates a space for Christians in feminism and feminism in Christianity.

In the same vein of recontextualizing the messages of the Bible, I thought of Chinelo Okparanta’s Under the Udala Trees, in which her main character Ijeoma, a queer Nigerian girl to woman, does just that. Growing up with her religious mother, working as a house girl for a religious family, and then attending a religious school, she is constantly confronted with people using the bible as a way to demonize and dismiss homosexuality. From a young age, however, she thinks critically about the Bible and the messages it means to convey. Okparanta speaks herself, in the interview I included, about the importance of re-interpreting the text as time goes on and not blindly accepting the ideas that organized religion enforces. In many cases, the passages cherry-picked to condemn homosexuality in particular can very easily be interpreted to have other lessons. Through doing this, it creates a religious space in which ideas can be progressive and makes space for queer Christians.

All of this informs the idea that in order to gain rights for womxn in all spaces, there needs to be strong womxn fighting for rights in all spaces. While before I might have said “If a church doesn’t support me, I won’t support it by being a part,” these examples have made me see that sometimes being a part of an organization that might not support you while also bravely ushering in the ideas that you believe are right is the most meaningful way you can support an organization and create change. Thinking about this from the viewpoint of a queer woman, if I were to be a Christian (I’m not, but for the sake of elucidation), and I believed strongly that I should support a church that didn’t support me, then the best way to support it is by being a part and changing their tune. The strongest advocacy for the LGBTQ+ community, in that instance, would be bravely showing up as myself in that space. Just by occupying that space, one creates a third way, and begins to change the minds of others and make a difference.

Another aspect of the third way that should be examined is a philosophy encouraged by Elif Shafak, author of Three Daughters of Eve, which is the belief that faith can be reclaimed from religion. Oftentimes, there can be a disconnect between pre-established organized religion and someone who has faith in God. This happens with her main character, Peri, who finds she cannot relate to her mother’s Islam, nor her father’s secularism. She has an agnostic belief informed by mysticism in her life. Through this, she is allowed to understand the concept of a God and be open to it, while still maintaining her belief in science and education. She breaks the dichotomy between religious and secular education.

Shafak embraces the ambiguity of religion, and all of the complexities of it applied to different cultures and social contexts. There is no way that every person who says they are of a certain religious belief actually believes the same exact thing. Due to the complexity of human beings, religion, being a product of human beings, must mirror them in complexity and nuance. Following this logic, each person should have the opportunity to “choose their own adventure” in a sense and understand their faith in a personalized way. If we look at religion in this way, and a body of worship doesn’t share the same exact thoughts but only similar ones, then there is less of a chance of hate being a product of that.

In this commonplace book, I included a TEDtalk from Lesley Hazleton that I came across in an Introduction to Islam course in my first semester freshman year. It has always stuck with me because of the conclusion she draws that doubt is essential to any kind of faith. In order to have faith in something, one needs to make a conscious decision to believe it in spite of doubt. Too often, in religion, it can feel like either you have blind faith and you’re a good practitioner of said faith, or you have doubt and are a transgressor. Hazleton, agnostic herself, offers a third way out of this. Blind faith is easy. Real faith is choosing to believe something despite your doubt otherwise.

0 notes

Link

Having had a cup of hot tea and written a bit — my mind sweetens on life once again.

The mercurial aspect of me! Why is it so extreme? No drug, not even aspirin, and yet my mood is as different from what it was 45 minutes ago as the Himalayas are from the Sahara. Why? What does it mean? Am I so utterly a creature of my juices? Entirely? It would seem so.

— Lorraine Hansberry, from her journal entry titled “Puzzle” March 15, 1964

¤

A RAISIN IN THE SUN playwright Lorraine Hansberry is one of the most noted names in US theater history. And yet it is only now, more than five decades since her death in 1965 at age 34, that we are beginning to uncover her influence beyond the stage. As a journalist, Hansberry was a social justice warrior whose work brought her under FBI surveillance. She was an activist who took on the Kennedys (both John and Robert); associated with the likes of Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, James Baldwin, and Langston Hughes; and in her personal life, challenged conventional mores of race, gender, and sexual politics: she married a man, but identified as a lesbian.

Born on the South Side of Chicago, the daughter of Southern migrants, Hansberry grew up in the gap between the black bourgeoisie and abject poverty. Her move from the Midwest to the Great White Way forms scholar Imani Perry’s Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry, an American odyssey and intimate portrait of an artist — young, restless, gifted, and black — at a crossroads between craft and justice; between life and dreams; between self-care and sacrifice.

“One of the great lessons from that period is what it really meant to invest one’s self in the struggle,” said Perry on the phone from her home in Philadelphia. “You think about how young she was when her passport was taken; she was under surveillance — this was her early 20s. Same with [W. E. B.] Du Bois, same with Paul Robeson. Now everybody loves Baldwin, but they were talking about him being too political after the deaths in ’68 when he was like: ‘I think we need to give up on this place.’ Then he wasn’t right anymore; he wasn’t smart anymore. You can say the same for King.

“But the point is, they were willing to give up everything for their investments and struggles for justice. We have to get to a way of celebrating not just their achievement, but their courage and their sacrifice because it really poses the question for us: What will we stand for? What are we willing to risk?”

¤

JANICE RHOSHALLE LITTLEJOHN: In the book’s introduction, you wrote that Hansberry’s “is a story that remains in the gap,” and you go on to discuss the various people who are going into those gaps to reveal who she was and her impact on culture. What is it about this particular time that has prompted this kind of interest in Lorraine Hansberry, her story and what it means to us now?

IMANI PERRY: A piece of it is definitely the renewed interest in black women’s history, in particular, and attention to the submerged histories of black women. Combined with the fact that she’s this figure who sits at the crossroads of so much: she identifies as a lesbian, she’s a woman who comes of age in Chicago in the midst of this period of intense discrimination and upheaval and migration. There’s all of these forces that are part of her identity and her story that are in some ways very similar to the kinds of questions we’re talking about now, whether it’s about the inequality — just this morning on Twitter there was this robust conversation about violence and racial inequality and policing in Chicago, all of which were central to her life — or this kind public conversation about intersectionality, and for her she’s trying to figure out feminism and sexuality, race, class.

All of these issues are at the forefront of our minds right now. On the one hand, she speaks to the moment, and on the other, she’s this incredibly well-known figure, the most widely read — arguably — black playwright in the history of the United States, and yet there isn’t that much known about her life. There’s a natural curiosity that hasn’t been fully satisfied.

Tracy [Heather Strain] did an amazing job with the documentary [Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart] giving us a picture of her life, and there’s just so much work to be done.

What kind of community has developed from those of you who have been exploring Lorraine Hansberry’s life? You mentioned Tracy Heather Strain along with others in the book. How often do you connect with each other to share stories or findings, or simply borrow from one another to fuel the work you’re each doing?

Working on her and being in a community with Tracy, [biographer] Margaret Wilkerson Sexton and [scholar] Soyica Colbert has been this extraordinarily beautiful experience. So often there’s this sense of competitiveness and selfishness and guardedness with respect to work on a figure, and my experience thus far is that we all have this sense of this being a collective endeavor in trying to give Lorraine her due. We have conversations. We did a panel together at the Schomburg [Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem] in the spring that was really wonderful. We all bring different emphases to our work, so there’s room for many books about her. I’m also excited about the different sides of her that will emerge from the different bodies of work. Given how intensely competitive academia can be this is such a beautiful, refreshing experience to work with people where everybody is really motivated by the work and not self-aggrandizement or selfishness.

In the book, you do draw some of your personal parallels that you feel have connected you with Lorraine’s story. Can you talk a bit about those similarities? And, to piggyback on that, as you were “looking for Lorraine,” were you able to gain any insights on yourself?

Certainly, the kind of space she occupied between the radical left and black working-class life and bohemian counterculture, all those spaces were very familiar to me — and really the environment I came of age in — so she was always this figure to me that felt like the reflection of the kind of coming-of-age experience that I was having. But I think actually working on her, more than the stuff about identity and where she was situated, but her dispositions, the sense of restlessness, this feeling of wanting to do everything and feeling kind of all over the place and being so overwhelmed by passion to do this project and that project, I really identified with that. My tenderness toward her — seeing how she was very self-critical in a way that I can tend to be self-critical — actually allowed me to have more tenderness toward myself; to not see this sense of hunger to explore as a weakness, but one of the many kinds of dispositions that people who are trying to live the life of the mind and are trying to do something good in the world can have. It wound up being, and was not intended as such, a very affirming process.

You mentioned earlier Lorraine’s migration story, which you discuss in the book, and how her upbringing — being the daughter of parents who migrated from the South; her father’s activism while still being part of the black bourgeoisie ��� not only shaped Lorraine’s social and political views, but also inspired her art.

It’s one of the things that is such a sign of her sophistication and maturity well beyond her years — because she died at 34 years old. Her parents were very much traditional mainstream civil rights bourgeois black people, and she has a very different set of politics: she’s on the far left, she’s radical, she’s unconventional. And yet, she really has a great deal of respect and appreciation for the labor of her parents — and in particular her father — for their struggles and their commitment to black people. I find it really intriguing and also useful as a model to think about how she could have a different set of politics and yet see a real value and integrity that motivated the work that they did. She was a communist and a socialist, and at points anticapitalist and not patriotic, and yet she understands her family’s efforts at accumulation were still an effort of racial uplift. That I thought was really powerful.

In terms of seeing her as a child of migration, and this is one of those pieces that certainly resonated — although I was born in the South — but feeling the proximity of a migration story, and I always think of Chicago — actually to echo Langston Hughes’s poem that forms the title of A Raising in the Sun — is this site of the dream deferred. There’s a deep anger and also a melancholy that she carries that is really at the heart of it; both about the aspiration that this was going to be better and the reality of how deep racism and inequality were in Chicago.

That finds itself in both the way she talked about migration and what it ultimately didn’t provide, and also in the way she talked about her father’s journey and how he spent his whole life doing things the “right way” and then dies embittered in Mexico. He ultimately gives up on the United States. That, to me, is something that’s very much a sign of her as a second-generation migrant — and I often use the language of immigrants when I talk about migrants because we don’t talk about migrants as such, but it really is a profound displacement and rearrangement of one’s life. There’s something powerful about her in that role generationally that comes out repeatedly in her work.

There’s a scene in the book in which you describe the white mobs that frequently harass the Hansberrys in Chicago, and “that the failure of police to protect black residents from white mobs was to be expected,” but that “what Lorraine meditated upon with some frustration was gender,” and that seems evident throughout the book. Although race and class were issues in which she was politically and artistically involved, was there a burden for her in being a woman?

It’s complicated. On the one hand, she very clearly identifies as a feminist and is also very explicit about the particular burdens that black women bear. But there’s also a way in which she is really chafing against not just gender roles, but sometimes I read her deep identification with male writers and male activists as almost a real frustration about being confined to the spaces that women were traditionally confined to. So sometimes it feels like there’s a little hitch in her feminism. [Laughs.] That’s one of the great things about being in her archive because you see all of these characters who start as women or stories that begin centering around women and then she changes the protagonists to men over and over again, and I feel like I know why she’s doing that. Partially it’s because it’s the way that genders work in a society, but it also, for me, complicates her feminism. These characters do become more believable as men, but what’s the cost of not having women at the center in that way?

Many of her early influences while she was in college were also men: Seán O’Casey and Frank Lloyd Wright and Carlos Mérida. Not only were they people from whom she drew artistic inspiration, but she also admired them for the way they could unapologetically live and move in the world.

There are a couple of figures she’s less explicit in talking about their influence but obviously Gwendolyn Brooks and Alice Childress — and the Brooks thing is interesting because she seems to me to be so influential and Hansberry didn’t talk about that at all, which is surprising. It may have been more about politics than anything because Hansberry was a radical before Gwendolyn Brooks became more radical, so her influences did tend to be men.

At the same time in her work, even when men were the central characters, she was very critical of men and masculinity, so she brings a feminist lens; there’s a feminist critique going on.

If you think of her in Les Blancs, which is one of the earliest versions of an anti-colonial play, and technically unfinished, is a really strong critique of patriarchy and ideals of masculinity there, and it’s the character who is a queer man who has the greatest courage and integrity in the story. Les Blancs is not often read in that way, but I really think it’s a very strong critique of patriarchy, and even in A Raisin in the Sun Beneatha’s suitors are; even Joseph Asagai — the character who is some ways very much Hansberry’s voice as much as Beneatha’s — is still a critique of his sexism even though he’s someone who carries a lot of her political ideas in a more sophisticated way than Beneatha is doing.

All that to say, it’s complicated.

As was Hansberry. As you lay out in the chapters, be it her time in college, her political leanings from communism to socialism, her marriage and sexuality, there was always this restlessness about her.

Yes.

In moving through the book, do you believe this restlessness, and even in her depression — in which she would then create poems and plays and other work — serviced her as an artist?

That is a great question, and it’s such a subjective question. I think yes. But I can also see an argument made in the alternative, and it really does depend on what people do with the archive. Most people look and say: Oh, my goodness there’s all this unfinished work, and perhaps if she hadn’t been so restless and she homed in on just one project at a time we’d have more fully fleshed out work and that would have been in greater service to her art, and the fact that she went through all these emotional ups and downs made it impossible for her to finish all she wanted to finish.

I think differently because it is such an enormous body of work for someone who was 34 years old to have completed, particularly given the last couple of years of her life she was so severely ill. But I also think that the meaning or the value of the art isn’t only in the completed artifact but that there are all of these works that are partial vignettes or stories or poems that are so beautiful, really extraordinary; poignant. When you look at the body of the work and the way that she was searching and all the different kinds of engagements of ideas and aesthetics, I do think the restlessness served her. I do think going into that space of searching, of deep loneliness, of trying to pull together all of the aspects of who she was and imagine a world in which she could exist. Just part of what that was, I do think that it led her to some insights that were really profound.