#i think my favourite of my recent writings is how the narrative of a dissociative person who is having an identity crisis just

Note

Nothing is better than reading about an artist's thought process so here's a free ticket to explain the symbolismor imagery you've put into one of your drawings and no one pointed out!

jesus christ okay so i dont post a lot of my art anymore, its usually hidden in ye ol friend discord server but a while ago i made these three drawings of freja loke and oden that fell under the radar as expected even though they were some of my most polished pieces in a LONG time (other than the syllvia painting which i believe i wrote about in a read more)

so heres the thing... i suck as visual symbolism, all my symbolism and allegory? straight to the writing, drawings are all straight up and down you see what you get and id love to talk about the tiny shit in A Knotted Embroidery Thread but im two chapters away from even publishing it so Pain yknow

anyways back to the drawings:

the freja drawing was the first one i did and the premise was simply to draw her in like Casual Clothed aka what i could find in swedish general clothing stores however comma heres some of the details; 1: people usually draw freja as blond which is bullshit and i made her dark brunette because i wanted her to embody the beauty of many people and even in sweden having very light hair in adulthood naturally isnt very common. 2: the most beautiful clothing item i know are hijabs however im aware enough to understand that it would be insensative to put a vana in a muslim headscarf so i went looking at russian headscarves and found a lot of interesting shit. 3: the background, though abstract, is a sunset behind snow. due to the phallic symbolism of midsummer and freja and frej being twin gods of fertility i personally believe that freja is the embodiment of wintertime fertility what with the amount of babies that will soon be born (re: midsummer traditions) and spring returning

the loke one i did second and it has just So Little Symbolism its great. most people would draw him as a dark haired green eyed shifty little bitch but i gave him the rat blond trash hair of your most common swede not yet brunette and dark blue eyes, my dude is exhausted and tired of being accused of shit, comfy as hell clothes because he fucking deserves it post snake venom all in his eyes for eons

the oden one im most proud of because it looks Ominous which is the way i feel about oden, i dont trust that motherfucker At All. I worked very hard with that piece to where he looked like a friendly grandpa that has all the hot gossip but also will take all your secrets and blackmail you if youre not careful, do not give him your real name. Hugin and munin are in that art and my greatest joy with them is that they show opposite eyes, they are odens eyes and thus they share a left ad right eye of the same icey fucking unshaded color with their master. i cannot express how little i trust oden

#i was gonna draw hel in that series too sadge#but yeah like all my symbolism goes into my writing where i cant actually Show what i want#like when i draw ill draw how i want it to look and feel#cant do that with words#i think my favourite of my recent writings is how the narrative of a dissociative person who is having an identity crisis just#the narration breaks down#the narration starts having major trouble refering to the character and thats my greatest feat i can remember rn#eats this ask i love it

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Princess Lavinia: Chapter One

Description: Roman projects his feelings onto a fictional character. Things get out of hand.

Pairings: Platonic prinxiety has a lot of focus in this chapter, but the real pairing here is Roman x depression

Warnings: Suicide, suicidal ideation, dissociation(?)

Notes: Seriously, don’t read this if you’re not in the appropriate frame of mind to read about suicide. Also, first fic on the new blog! Yay!

Roman’s adventures with Princess Lavinia started off fairly innocent. He’d made himself a small kingdom in the mind palace in which to conduct magical adventures, and, with the other sides frequently too busy to join him in his exploits, it wasn’t long before Roman saw the need to create an adventuring companion as well. She was the archetypal fairytale princess: pretty, kind, and able to fill any role that the narrative required of her. Because she was created by Roman, Lavina lacked the capacity to do anything that Roman’s own imagination could not conceive, but, as the embodiment of creativity, he didn’t feel at all restricted by this limitation. Lavinia quickly became one of Roman’s favourite hobbies: when he needed a break from his work, he would excuse himself to his kingdom. There, he would act out a variety of stories with Lavinia: saving her from dragons; exploring ancient ruins with her; defending their kingdom from armies of hostile elves. The many enemies they slayed left no corpses behind, instead exploding into red rose petals. Death was messy, and Roman thought it best to avoid dealing with it too directly.

“You’re my best friend,” he had Lavinia say after one particularly eventful quest, “and I would slay all the monsters in the world with nothing but a hand fan just to keep you safe.”

“Oh, that’s good,” he replied, writing the line down in his notebook. His adventures with Lavinia were an excellent source of dialogue. Later, he had her do exactly the thing she had described, and then did it himself just to see what it was like. It was wonderful.

♥♥♥♥♥♥

Gradually, Roman found himself spending more time with Lavinia than with the other sides or Thomas. He loved his friends, but his interactions with them didn’t quite sparkle the way his stories did. Nobody and nothing was dramatic enough, or emotional enough, or real enough, except for that one little piece of the mind palace and the make-believe Princess living in it. Everything else in Roman’s life felt unbearably boring, and although his friends made things a lot more tolerable, they could never compete with the products of his own imagination.

One afternoon, while they were enjoying a picnic after a successful battle, Lavinia turned to Roman with a frown. “Are you okay?” She asked. “Your heart didn’t really seem to be in it today.”

“Oh, it’s nothing.” He stared down at his untouched sandwich.

“It’s not nothing! You can talk to me about anything, Roman. That’s what I’m here for, I think.”

Roman sighed. “I don’t know,” he replied. “I guess the whole… fairytale adventure thing feels a bit hollow right now.” So does everything else, he nearly added. “I think right now I’d prefer something more…” he gestured vaguely, trying to find the right word.

“Mature?” Lavinia suggested.

“Maybe. I think what I want is emotional depth. Swordfights and dragons are fun, but I think I’m not really feeling it right now.”

“Hmmm…” Lavinia looked down and fidgeted with her hair, taking in this new information. After a few seconds, she met Roman’s eyes again, sorrow written clearly in her expression. “I’m cursed,” she announced. “Someone has taken my heart and locked it up in a faraway, secret place, so that I can never really be human again.”

Roman scribbled excitedly in his notebook, letting a wave of sorrow and pity wash over him. It felt beautiful. “That’s terrible. How can we break the curse?”

Lavinia stared at Roman in silence for a few seconds, and he suddenly felt as if she was looking directly into his soul. “I don’t think we can,” she said.

♥♥♥♥♥♥

For the next few weeks, Roman spent most of his time with Lavinia, fleshing out her backstory. He wrote it all down in his notebook for future reference: Lavinia’s villainous twin sister, exiled to a distant land for her crimes; her desperate desire to impress her father, the king—all of it was carefully summarized in neat, princely handwriting for incorporation in future creative projects. Roman felt genuinely passionate for the first time in a while. Meeting with Lavinia and learning more about her became the highlight of his day; the stab of sorrow he felt in his gut whenever she disclosed something particularly tragic was invigorating. It made him feel so much more alive than he had in weeks. And then—

“I shouldn’t be alive,” said Lavinia.

Roman had, on some level, seen it coming. After all, he was the one coming up with Lavinia’s lines, however passively. This did not prevent him from nearly dropping his notebook in shock. It hurt to hear her say that, and he loved it.

“Why?” He asked her.

“I’ve been thinking about the curse,” Lavinia explained, “and the more I think about it, the clearer it becomes that I was wrong. It wasn’t a curse at all; I had no heart to take because I was never real enough to have one. This body,” she ran a shaking hand along her arm, “people like to make up stories about it. They imagine that it is a princess, and that her name is Lavinia, and that she is kind and cheerful and brave,” Lavinia was crying, “but it’s a corpse, and I am a ghost who has stolen it.”

“What are you going to do now?” asked Roman. He noticed a small knife in Lavinia’s hand. How long had it been there?

“I don’t know,” Lavinia admitted, staring down at the knife. “Too many people think Lavinia is real. I don’t want to disappoint them.”

The knife quickly dissolved into rose petals, and Roman felt a strange sense of disappointment as he watched them slip through Lavinia’s fingers.

♥♥♥♥♥♥

It was three days before Lavinia went through with it. When she pressed the knife to her throat, Roman begged her not to do it. He didn’t mean it of course (the whole scenario was still his idea); he just felt like it would ruin the immersion for him to just stand around and do nothing. Inevitably, she cut her throat. Inevitably, Roman held her in his arms and watched blood flow from the wound with the detached voyeurism of an author writing a tragedy. Inevitably, she exploded into a shower of rose petals.

Roman stayed sitting on the floor for a while, blood on his clothes and rose petals in his hands. His heart was racing, and he felt like his whole body was soaked with sweat. That beautiful, overwhelming sword of pain was stabbing through his heart with an intensity he had never before felt. It was agonizing, and it was glorious.

Roman snapped his fingers, and Lavinia was back in front of him, unharmed.

She went for the knife immediately.

They went through the scenario five more times, trying out different lines, different actions on Roman’s part, different ways for Lavinia to hurt herself. Roman was preparing himself for another run-through when he felt himself being pulled out of the mind palace.

He rose up in his usual spot. “Roman—“ Thomas, who had evidently summoned him, cut himself off with a gasp. “Oh my gosh. Are you okay?”

Roman glanced around the room. Patton, Logan, and Virgil were all there in addition to Thomas, and all of them were staring at Roman with varying amounts of horror and concern. Roman abruptly remembered that he was covered in blood.

“Don’t worry,” he assured Thomas. “It’s not mine.”

Nobody looked particularly comforted by the clarification. “Do I want to know?” asked Thomas.

“Probably not. Anyway, what’s the situation?”

“Recently,” Logan explained, “Thomas has noticed that many of his ideas are much more melancholy in tone than usual. Remus swears that he isn’t the one responsible, so, logically, it must be due to your influence that Thomas is having these ideas.”

Panic filled Roman’s chest. “I’m sorry—“

Thomas cut him off. “I’m not mad. I’m totally fine with using darker concepts in my work if that’s what you think is best. I just want to make sure you’re okay.”

“You haven’t been talking as much lately,” Patton added, “and some of the concepts you’re giving Thomas are a bit… out of the ordinary for you.” He made eye contact, looking noticeably concerned. “We just want you to know that you can talk to us if there’s something wrong.”

Anguish returned to Roman’s chest, feeling more agonizing than cathartic. He’d failed. He’d let his feelings get in the way of his work, and now everyone thought there was something wrong, and they were all looking at him with those kind, worried expressions that he knew he didn’t deserve.

What would they think if they knew what he’d been doing all afternoon? Roman glanced down at the blood on his clothes and decided that everything was fine. It had to be.

Roman laughed, perhaps a bit too loudly. “Thank you all, but I’m fine, really. I just wanted to try some new ideas. On a scale of one to ten, how much do you love them?”

Virgil stared suspiciously at him from across the room. “Do your ‘new ideas’ involve you rising up covered in blood and looking like you just saw a serial killer? I saw the look on your face when Thomas summoned you. There’s something you’re not telling us.”

“I was having one of my adventures just now, and things got a little intense,” Roman said, his heart racing. “Not everything has some deep hidden meaning behind it, The Smell Jar.”

“That was childish, even for you,” said Virgil, “but I like the Sylvia Plath reference.”

“Ah, Sylvia Plath,” said Logan. “Did you know that, in addition to her writing, she also made visual art?”

Roman’s strange behaviour forgotten, the conversation moved on.

♥♥♥♥♥♥

Over the next several weeks, Roman found himself with less and less motivation to do anything but run through stories with Lavinia. He told himself that he was still being productive—he continued to write things down in case they came in handy for a future creative project, even though his “adventures” in the kingdom were all far too violent and depressing to ever be turned into something useful for Thomas. Roman hardly ever wanted to tell stories about anything other than suicide. It was, of course, only a matter of time before things escalated further.

One day, after around the eighth time Lavinia had died, Roman realized that his usual routine was starting to get boring. That dazzling anguish in his chest was diminishing in intensity. He needed something more real, something more personal. He needed—

Roman snapped his fingers, and Lavinia appeared looking much more alert than she had in weeks.

“I want to die,” he told her.

♥♥♥♥♥♥

That day, Roman attempted suicide nine times. None of it was real, of course, but he did his best to make it feel real. Lavinia pulled him close, kept him back from the windowsill, repeated over and over again every reason Roman could think of for him to stay alive. He told himself it was only acting. By the third time, he felt as if he was on the verge of tearing in half: one part of him, his body made of shaking, warm metaphysical flesh, stayed with its feet planted firmly on the ground. The rest of him drifted in and out of sync with his body, bobbing and pulling up to the sky like a balloon tied to his wrist. At the time, it seemed overwhelmingly important to Roman that he find a way to cut the string: it was strange, being only halfway outside of his body. He would have greatly preferred to drift away entirely, to break into pieces and sail through the sky to places unknown.

He told himself it was only acting.

It was fairly late in the afternoon when Roman remembered his notebook. Head still spinning from the previous several hours, he reached into his pocket and found it empty. He’d forgotten the notebook. In its place, Roman summoned a slip of paper and a pen. He’d copy his notes down later.

♥♥♥♥♥♥

Roman headed back to his room a few minutes later. He still felt somewhat disconnected from his body, but the feeling was fading fast. He made an effort to notice the colours of things. White walls. Brown rug. Black shoes. Roman was still naming colours when he opened the door to his bedroom and saw Virgil pacing nervously around the room.

At the sound of the door opening, Virgil turned to look at him. His eyeshadow was smudged, and he looked like he’d been crying. He was holding his phone in one hand and Roman’s notebook in the other.

There was a long pause. Roman internally braced himself for yelling, or crying, or deeply awkward emotional conversation.

“You weren’t answering your phone,” Virgil said finally.

Roman gestured to his dresser, where his phone sat partially obscured by a small stack of loose paper. “I didn’t have it with me.” He watched Virgil quickly type something. “What are you doing?”

“I’m texting Patton. I was worried, so I asked him to go look for you.”

“Oh.” Roman suddenly felt very nervous. “I’m sorry. Does he know about…?”

“This?” Virgil held up the notebook. “No. I found it when I was in here looking for my nail polish.”

Roman walked over to a nearby drawer and produced a bottle of black nail polish with a little Jack Skellington face on its lid. He’d ‘borrowed’ it a few weeks prior for some now-abandoned photography project, and subsequently forgotten about it. “Here.” He handed it to Virgil.

“Thanks,” said Virgil, slipping the bottle into his hoodie pocket. “I’d remind you to stay out of my room, but it looks like we have more important things to worry about right now.”

There was another pause. “You probably want to talk about that, don’t you?” said Roman, gesturing to the notebook in Virgil’s hand.

“Yeah. Can we go somewhere else—I mean, if you’re comfortable—”

Roman waved a hand, and suddenly they were in the castle he’d created for Lavinia. The light of a full moon streamed through a floor length window, illuminating the antique-looking couch that was the centerpiece of the room. An archway opposite the window led out to a pristine, wallpapered hallway. “Is this good?”

“Yeah, thanks,” Virgil said nervously. He walked to one of the couches and sat down with strained formality. Roman quietly took a seat next to him. “So, um… first question: who’s Princess Lavinia?”

“She’s a character I created. This,” he gestured to the room around them, “is where she lives. I come here when I’m craving adventure.”

“So, she’s like an imaginary friend?”

“Basically. She’s upstairs, if you want to meet her.”

“I…” Virgil glanced down at the notebook. “No thanks. I want to talk to you. Second question: what’s the deal with this notebook?”

“That’s where I document my adventures with Lavinia, in case they come in handy for scriptwriting or something similar.

Virgil nodded. “Okay.” He took a deep breath. “I guess what I have to ask is… why all the suicide? Like, at least half of this notebook is just Princess Lavinia killing herself in different ways. That’s not exactly an ‘adventure.’ It sounds more like you’re having some kind of mental breakdown that you cope with by standing in an imaginary castle and watching a fictional character die over and over, which is honestly pretty concerning.”

“I am not having ‘some kind of mental breakdown,’” Roman insisted. “I am acting. What, am I not allowed to tell stories with emotional depth?” That last question came out a lot more aggressively than Roman had intended, but before he could apologize, Virgil was already responding.

“This isn’t emotional depth! This is the same emotion repeated over and over for, like, forty pages!” Virgil paused. “Is this what you were doing that day you showed up covered in blood?”

“Yeah. That was basically when it started.”

Virgil paused, taking in this information. “That was a month and a half ago,” he said, horrified.

Roman felt sweaty. “It’s not as bad as it sounds. You don’t need to worry—”

“Have you forgotten who you’re talking to?” snapped Virgil. “Of course I’m going to worry! I’m Anxiety, and you’ve been roleplaying suicide fantasies with your weird self-insert OC for—” he stood up and flipped frantically through the pages of the notebook. “Have you been doing this every day?”

Roman nodded, very much wishing he could escape the conversation.

Virgil swore quietly. “This explains so much.”

Roman stood up and awkwardly extended a hand to comfort him. “It’s really not that big of a deal.” He was suddenly aware of an inexplicable sense of urgency.

Virgil stepped backwards, avoiding Roman’s touch. “Not that big of a deal? Are you kidding me? You barely talk to anyone at all anymore, you give Thomas either weirdly depressing ideas or nothing at all, and you literally spend all your free time thinking about suicide. If you actually think you’re in any way okay, then you’re either deeply in denial or a complete idiot.”

“I’m not…” Roman trailed off. Somehow, he couldn’t think of a rebuttal. He went over the past few months in his mind and realized that Virgil was right. “I haven’t been myself,” he admitted, sinking back onto the couch. “I don’t think I’m even real, actually.” Roman buried his face in his hands, fighting back tears. He was suddenly very conscious of how exhausted he felt.

The room was silent for several long seconds.

“What do you mean?” asked Virgil.

Roman looked up, and saw that Virgil had quietly taken a seat next to him. What did Roman mean? Of course he wasn’t real—none of them were, but Roman’s words had meant something more than that. Looking at Virgil, he got an impression of existence that he hadn’t gotten from himself in a long time. Virgil was Virgil, in a way that Roman could never hope to be Roman. It occurred to him that perhaps he’d been projecting onto Lavinia a bit more than he’d realized.

“I’m supposed to be better than this,” said Roman. “I’m supposed to be Prince Roman, source of Thomas’ hopes and dreams. I’m supposed to be Creativity. I’m supposed to be kind, and charming, and brave, but I’m just…” he trailed off. “If I can’t give him anything to look forward to, what good am I? Why should I exist?”

Roman hadn’t expected himself to say that. “This is a problem,” he said through tears, “isn’t it?”

“Yeah,” said Virgil. They sat in silence for a moment before he spoke again. “Look, um… it might not mean much, because our situations are kind of different, but I used to think that I didn’t contribute anything useful, and that everyone would be better off without me, and that it wouldn’t matter if I removed myself from the equation. Do you remember what happened when I actually left?”

Roman stared thoughtfully at the carpet. “Thomas became a complete fool with no inhibitions.”

“Right! Because I was wrong, and so are you.”

Roman considered this for a moment. The words were so simple, and yet, somehow, Virgil’s reassurance felt so much more comforting than any of the things he’d had Lavinia say to talk him down. “That… actually helps a lot. Thank you.”

“Anytime.” Virgil crossed his arms thoughtfully. “We should probably tell Thomas to see a therapist or something. If you’re… like this, he probably isn’t doing great either, whether he realizes it or not.”

Roman nodded. “That’s probably a good idea. Just…” he hesitated, “can we keep this a secret? The things I just told you about, I mean.”

“Are you sure?” asked Virgil. “It seems like something he should know about.”

“I’m sure.” Roman felt a surge of panic. He couldn’t let the others know. He wasn’t quite able to explain to himself why, but it felt crucial that everything he and Virgil had discussed should remain between the two of them. “I don’t want to have that conversation yet. Besides, maybe therapy will fix it. If Thomas feels better, I’ll feel better, and then we won’t have to bring it up at all.”

Virgil looked doubtful, but nodded anyway. “Okay,” he said. “I won’t tell anyone, but I’m holding onto the notebook. If you ever seem like you aren’t safe, I’m not keeping this a secret.”

Fair enough. “Deal,” said Roman, holding out his hand to shake. Virgil started to reach for it, but paused.

“Wait,” said Virgil. “One more thing. Actually, two more things. Number one: I want us to stay here tonight, because I really don’t feel comfortable leaving you alone.”

Roman thought back to the day’s events, neatly recorded on the slip of paper concealed in his pocket. He had a feeling that if Virgil knew the exact details of what he’d been doing, he would be requesting a lot more than permission to supervise him for a single night.

“That’s probably a good idea,” Roman admitted. “What else?”

“This is more of an offer than a request, but,” Virgil nervously ran his fingers along a seam on his sleeve, “I could join you here sometimes, if you want. Just so you won’t be spending all day alone with your thoughts.”

Roman thought for a moment. “Are you open to the possibility of magical adventures?”

“Sure,” said Virgil. “But only real adventures; no weirdly-emotionally-intense-and-bordering-on-self-harm adventures.”

Roman had a feeling that he might regret this later, but he had a much stronger feeling that Virgil’s offer was exactly what he needed. “Perfect,” he said. They shook hands.

Virgil gave a small, relieved smile, which Roman returned. He wondered how long it had been since the last time he’d genuinely smiled. A few days? A week? A month?

They fell asleep on the couch, listening to the Death Note musical on Virgil’s phone.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

SPAM Digest #5 (Feb 2019)

A quick of the editors’ current favourite critical essays, post-internet think pieces, and literature reviews that have influenced the way we think about contemporary poetics, technology and storytelling.

‘Terminology’ by Callie Gardner, Granta

I’ve lost track of the amount of times I’ve recommended Callie Gardner’s astonishing piece, ‘Terminology’, to friends and family. Sometimes you read something and it’s as though the world decided to refashion its atoms around the text, wear it like a brand new garment. I had to cry a little, admittedly, to realise this. I guess I was reading the essay in darkest November and found myself astounded by its honesty and light. It’s not all sunshine, but it’s definitely a form of waking up, of gradual awareness and loosening. ‘Terminology’ begins with a sleeper train, a world where people wake up in carriages and put on what they want to, unbound by the violent constraints of our usual distinctions. These people keep their differences, but the differences are no longer scars of history, privilege.

The sleeper train is going somewhere. This future is open, potential; this future is based on care. This world, this place we drift towards on the train (I say we now, because I too want in on this world), is named Iris, ‘after the Roman goddess of the rainbow’. Iris, perhaps, is without terminus, the people that live there ‘speak a language with a hundred pronouns’. If this is a utopia, it is ‘an unscientific utopia’ that nevertheless glows with what already exists, what is within our reach: the charge of a ‘queerness in everything’. It is a mantra, a lullaby world and ‘a wish given flesh’. I wish every essay began with a world like this, a speculative projection towards where we could be when we open up, seek some generous expanse to sink into, flexing our selves afresh.

‘Terminology’ is about the body. It is about appearance and disguise, about survival, performance, expectation. It is about the precarity of the genderqueer person in public space, the social ties they might make out of safety, necessity. It draws attention to the everyday actions the genderqueer person might make for the sake of their own survival. The fact that we occupy space radically differently, depending on how society chooses to stratify our identities and consequent vulnerabilities. ‘Terminology’ moves from the hypothetical experience of the genderqueer person to the author’s own encounters with daily microaggressions, media representation and social relations in public, creative and professional space. Gardner describes, acutely, the violence of misgendering, intentional or otherwise: its physiological effect on the body, akin to a kind of dissociative paralysis, abjection. ‘Maybe this makes no sense to you’, Gardner writes, ‘It doesn’t make much more sense to me’. This is an essay of admission, working through, coming to terms, learning respect.

The reason I constantly recommend ‘Terminology’ is that it states the fundamentals with absolute clarity: ‘language is not ours to use without consequence’. It asks for an ethics in which we question what our words might do in a certain context, how we make and shape reality with discourse. Recently, the songwriter Kiran Leonard put it so eloquently in an interview, arguing that tenderness and cultural responsibility is ‘about thinking through when I’m speaking in the world, speaking against a thing, what world am I looking at, what world am I creating when I say these things, and what worlds are other people creating’. The world of Iris is a world we might make with a more commodious language, one which permits an expanded, plural sociality.

Gardner tentatively imagines what Iris would actually look like, the features of its ecology and landscape. I am reminded of the work of Queer Nature, ‘a queer-run nature education and ancestral skills program serving the local LGBTQ2+ community’: a collective who make it their mission to make links between the survival skills queer populations have developed for themselves, ancestral wilderness skills and other forms of marginalised knowledge. Wilderness, conventionally the domain of dominant hetero-male, becomes a queer space in which collectivity and silenced forms of self-reliance map onto the terrain as an active, responsive, symbiotic space of wonder, vulnerability and healing: an ‘Ecology of Belonging’, as Queer Nature put it. There is, in queer ecology, a blurring of active/passive as a binary. Survival might be about avoidance or withdrawal as much as presence and action.

Walking through Gardner’s imaginary Iris, we realise we won’t reach this space without confronting questions of identity around capitalism, sexuality, culture and ‘nature’. What is it to feel something as natural at all? Since society likes to police what is considered ‘natural’, how do we frame queer subjective experiences of embodied reality in collective contexts, without essentialising? There is the beautiful admission that queerness is not just about who or how you do or don’t fuck, but also about how you live, how you need to live. The doing of gender and intimacy. And looking for a language, a vernacular, a cultural narrative through which you might play out that life, which is not defined essentially but perhaps intuitively, iteratively, interdependently. Gardner calls for the necessity for nuance in a world where the conditions of survival often confuse the bounds of romance or friendship. If ‘gender is only history’, then we have to really reflect on where we are here and where we are going. Sadly, we aren’t going to wake up from the sleeper train in a lovely, wholly unbound country. But this isn’t to say utopian thought is useless. For Gardner, wanting a place like Iris is not a weakness but actually ‘a resource’ for recalibrating the self within dead-end, heteronormative histories.

The question of queer futurity versus Lee Edelman’s ‘No Future’ is of course a complex and rich one, which I haven’t space to go into here. What’s more interesting is the fact that this essay celebrates the possible while recognising difficulties and limits within the imagining of a place like Iris, as much as reminding us what happens in lived spaces like queer communities. Ultimately, ‘Gender is at once a material condition and a psychical state’. This essay, ‘Terminology’, is one of those rare places where the actual extent of what that means is acknowledged. Nothing covered in this essay bears easy solution or simple resistance, position. Identity, standpoint, community and experience are entangled in questions of occupation, flux and, frankly, difficulty. I learn a lot within its gauzy bounds, I find clarity of a sort; I look at the world around me anew, and I feel an openness in myself that, for once, I lack words for. I realise this is okay, I just need to read on; there is so much more to understand. ‘Citation’, as Gardner reminds us, can be used ‘as transfeminist practice’. As such, I encourage your own turning to ‘Terminology’: to follow its list of transfeminist writers, to think about your own version of Iris; mostly, to read and to listen, to drape this warmth over your shoulders, share it with others, without condition.

M.S

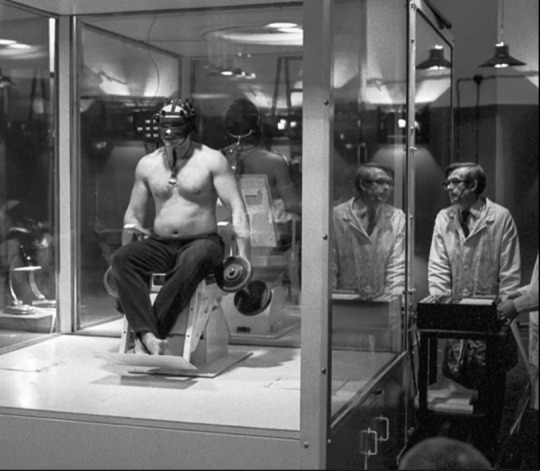

‘24 Hours Watching DAU, the Most Ambitious Film Project of All Time’, by Hunter Dukes and McNeil Taylor, Hyperallergic

This SPAM Digest might break the rules a little bit—it's a review of a review, and it has absolutely nothing to do with poetry—but do bear with me; I promise you I’m getting somewhere.

Last month, Mac Taylor and Hunter Dukes (yes, those are two real-life people; have you ever seen a better pair of names) went to Paris for the premiere of DAU, a film project of Tom McCarthian inclinations, and insane if not obscene logistic, aesthetic, and conceptual ambitions. Directed by the young Russian director Ilya Khrzhanovsky, DAU tells the story of Soviet physicist Lev Landau; Khrzhanovsky hired thousands of actors—or “participants”— as he refers to them, and deployed them to a custom-built set in Ukraine reproducing a research-facility. As Taylor and Dukes report:

From 2009 to 2011, the amateur actors stayed more or less in character. They lived like full-time historical reenactors, dressing in Stalin-era clothes, earning and spending Soviet rubles, doing their jobs: as scientists, officers, cleaners, and cooks. The film set became a world of its own. In all, 700 hours of footage were shot; this was eventually cut into a series of 13 distinct features, collectively titled DAU.

Apart from my obvious fascination with this Reamainder-like gargantuan re-enactment (did I mention I love Tom McCarthy), what really struck me was the format this project was shown in at the premiere:

To enter the [sprawling] exhibit, which runs through February 17th, you must apply for a “visa” through DAU’s online portal, choose a visit length (the authors of this article opted for 24 hours), and fill out a confidential questionnaire about your psychological, moral, and sexual history. Respondents answer yes or no to such statements as:

I HAVE BEEN IN A RELATIONSHIP WITH AN IMBALANCE OF POWER

IN THE RIGHT SITUATION, EVERYONE COULD HAVE THE CAPACITY TO KILL

Downloaded onto a smartphone, this psychometric profile becomes your guide to the exhibition. In theory, your device can unlock tailored screenings, concerts, and other experiences. In reality, none of this technology has been implemented in the theaters or museum. But it does not matter.

The premiere organisers chose to design and explicitly articulate the experience of a world around the experience of the world of the film; and to tailor this experience, in turn, around the premiere’s visitor themselves. Apart from sounding like a lot of fun, this exploitation and amplification (if not redoubling) of film’s world-building capacity made me immediately wonder: what would this practice would look like when applied to poetry instead of film? (I know, I have a one-track mind.)

One of the traits that poetry and film seem to me to share is the potential to conjure up alternative worlds that seems obey to their own logic and set of rules. Like film, long poems or poetry ensembles (pamphlets, collections, sometimes entire oeuvres, or to a lesser extent magazines) often seem to respond to aesthetic parametres of their own making, and to establish a certain unique space for experience that can only be accessed through the artwork itself. We all know what the world of David Lynch is, and what it is like—we know what it looks like, what it feels like, what is allowed and what is not allowed within its limits. And we know the world of Gertrude Stein or John Ashbery or Sophie Collins the same way; there’s not only a tone to this space of experience, but a also a flexible and entirely nebulous set of rules that seems to dictate—to code, if we want to throw in a sprinkle of the gratuitous post-internet buzzwords we SPAM people are suckers for—how the world behaves and how it responds to our attention.

Dukes and Taylor rightfully call DAU ‘a beguiling collection of moving images that call into question our basic assumptions about film production and consumption’, and I wonder what a poetry project with the same goal would look like. Apart from the cool re-enactment part, I imagine what it would be like if poetry could be tailored to one's history or personality; spending a day moving from venue to venue to take in bits of an orchestrations of poetry readings running 24/7. It probably wouldn’t work; it definitely wouldn’t work. But it got me thinking about what an alternative modality to deliver poetry IRL would look like. There has definitely been lots of experimentation (although never enough, IMHO) with the visual presentation of poetry: I’m thinking of Crispin Best’s pleaseliveforever, a poem that refreshes itself every few seconds into new L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E/lol combinations of words (what is the poem, then? The structure? The algorithm?); his poem that fades into lighter gray, only to darken into normal text as you keep scrolling down the page (what was it call? where did it go? Help @crispinbest). I’m thinking of video poems and surreal memes (yes you can @ me, those are poems). But readings are rarely stranger than a just a reading. We should get thinking about they could become weirder. Does anyone know how to make holograms?

D.B.

Image from Internet Machine by Timo Arnall (2014). image credit: Timo Arnall.

Always Inside, Always Enfolded into the Metainterface: A Roundtable Discussion

Speakers: Christian Ulrik Andersen, Elisabeth Nesheim, Lisa Swanstrom,Scott Rettberg, Søren Pold

Having been fascinated by Søren Pold's writing on literature and translation in relation to the interface, I knew when I saw this new roundtable discussion that it would most likely be making SPAM's February Digest. This discussion, made available on the Electronic Literature Review website, brings together the above speakers to discuss many of the ideas explored in Christian Ulrik Andersen and Søren Pold's 2018 publication, The Metainterface: The Art of Platforms, Cities, and Clouds (The MIT Press).

Covering a diverse range of theorists, artists, designers and academics, the speakers take as their focus the idea of the metainterface, examining how interfaces have moved beyond the computer into cultural platforms, such as net art and electronic literature. Forming part of this analysis are considerations of how the computer interface, through becoming embedded in everyday objects such as the smartphone, has become both omnipresent and invisible. Through exploring the different relationships that form between art and interfaces, the authors note that whilst during many smart interactions the interface becomes invisible, it tends to gradually resurface, the displaced interface then creating a metainterface. Their argument is that art can help us to see this, with the interface becoming a site of aesthetic attention.

It is the question of aesthetic attention, in varying forms, that runs through this discussion, offering the reader a profusion of references of artists whose work examines the metainterface. One piece that stood out to me was Camouflaged Cell Concealment Sites by the Canadian-American artist, Betty Beaumont. This piece consists of a collection of photos taken of cell phone towers disguised as pine trees or Saguaro cactuses. As Lisa Swanstrom notes in the discussion, they're terribly disguised, but ones that you could still overlook if you weren't paying attention. Similarly, Nicole Starosielski's The Undersea Network, is a book that makes visible the materiality of the internet through mapping the global network of fibre optic cables that runs along seabeds. In bringing these works to our attention, Swanstrom notes how both examples are questioning the aesthetics of infrastructure, as both are trying to reveal something about the ways in which we experience it, not just know of it.

Responding to the question of what our role as critical users of the metainterface is, Pold draws our attention to the fact that we are always a part of the interface and have to work from the fact of being embedded, as there is essentially no outside. This invites the question of how the artists and writers can respond to the conditioning of self into the metainterface. As Andersen points out, whilst there is no safe haven 'outside' of the interface, there are certain tactics that can be developed as a user. The example given, a chapter entitled Watching The Med by Eric Snodgrass in his work Executions: Power and Expression in Networked and Computational Media (Malmö University, 2017), points to how real users operate in the Mediterranean Sea (now a highly-politicized landscape) by switching between different GPS technologies and Twitter to 'recombine media in a tactical way'. The key idea to take from this is that whilst a reconsideration of our approach to tactical media in the condition of the interface is necessary, it doesn't mean we cannot operate on platformed versions of tactical media such as Facebook or Twitter.

Another point of focus in this discussion I found especially captivating was the consideration of the posthuman machine in relation to the reformulation of labour, in particular Scott Rettberg's consideration of the interface as an intermediate layer between humans and machines. In questioning whether we are moving towards a system in which the interfaces themselves generate human labour for the benefit of corporate entities, Rettberg poses the question of whether we can be alienated from our labour if we are not conscious of being laborours? This leads into a contemplation on the condition of cultural tiredness, an awareness that a certain media platform, such as Facebook, is packed with problems regarding social interaction and data protection, but still we continue to use its service.

Cautious of covering more than needs to be said in this digest, I will close by returning to the fundamental question that Pold and Andersen put forward in their work: the role of art and literature in shedding light on the behaviour and ontology of the metainterface. I find it interesting to learn that Pold started out by studying literature, before moving into a study of digital aesthetics. Perhaps it was the combination of these two domains that allowed him to see the act of reading the everyday interfaces of life as a literary act. This seems to be echoed in Andersen's response to the question of art and literature's role in an age of environmental crisis and metaintertface, whereby he looks to Walter Benjamin's definition of an author as a producer. To see the artist or writer as 'someone who produces not only the narrative, but who is a realist in the sense that he or she reflects what it means to produce in the circumstances that you are embedded in. So, the role of the author in the 21st century is to 'not only to use the interface as a media for the production of new narratives, but also use the interface, and reflect the interface as a system of production'.

With questions such as 'how are we being written by machines?' and 'how have we become media?' still yet to be answered, I encourage anyone interested in posthumanism and digital aesthetics to make their way through the full discussion.

M.P.

0 notes