#i still want to buy that knockoff lost cherry too....

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i think if i had money i would love to get into perfumes. i love me some good olfactory stimulation.

#anyways i looove sampling perfumes in makeup stores but i dont do it often bc i feel silly#there is one basil scented perfume im obsessed w that smells like freshly cut grass i neeeeeeed it soo bad#i still want to buy that knockoff lost cherry too....#also i love the smell of paint fumes and like. that stinky glue?? in another life id— no i shant finish the sentence#also i love the scent of tiger balm that camfor+eucaliptus combo is oughbhhh#piksla.txt#the only downside is i would also come across stuff that smells bad which isnt fun but tbh im a careful shopper

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Julien Baker, My Father, Two Decades of Noise, and the Quiet

Soda guns make a funny noise. Like a dozen dentists doing work all at once, some suction and a strange gurgle.

Usually, it’s also a noise that happens nonchalantly, especially in a place like this, the gurgle drowned out by the din and dissonance of the band and the crowd and the night.

Right now though, a couple songs into Julien Baker’s set at White Eagle Hall, the soda gun — and the cracking of a fresh beer, the opening and closing of the standard-issue industrial doors at the back of the room, everything — have become some kind of strange and unwelcome accompaniment, dropping in at all the wrong moments, a laugh-track mistakenly placed over A Very Special Episode.

This, of course, is partially my fault. I’m perpetually late and the kind of short where I’ve had to turn my annoyance at the dozens of phones shooting video that’s never gonna be revisited into an argument for how useful all those glowing screens are as periscopes. Too anxious to push my way to the front under some false “I’m looking for my friends” pretense, because I know my friends are not up there because they’re all at home because it’s Tuesday and we’re in our mid-thirties. And then what happens when I get to up there? Then I’m awkwardly planted next to a person who’s not my friends, inserting myself into this stranger’s night like I just hatched from my pod and am enjoying my first moments in this human body, cumbersome and lumbering, exploring the thing the earthlings call music.

Instead, I don’t move from the spot on the floor that I’ve acquired simply by ordering a beer at the bar and then turning and taking only the amount of steps required to get out of the way of the next person. But the hypothetical awkwardness stays, permeating the room in some other way. As I, from my tippy-toes, and the other 799 people packed into White Eagle watch Baker take the stage, it’s to a strange kind of silence.

The first live music I ever saw that wasn’t my father playing the organ in our house — like the first thing that involved a band and instruments, and an in-hindsight surprising lack of any kind of adult supervision — was a punk show at the Rockaway American Legion.

It was 1997.

I was the kid who wore Nirvana shirts to school every single day. A girl in my first period biology class was passing out flyers.

“I think you like music, I don’t know.”

She tossed the thing on my desk. I was never cool to begin with, but in this moment she was infinitely cooler than me.

I convinced my best friend to come, and my father happily volunteered to drive us, depositing two fifteen year-olds in some random parking lot with only a vague idea about when to return to collect us.

This, that he was so willing to do this, volunteered to do it, was a confusing thing about my father. He was angry and strict, though only about the small and specific things. I never had a curfew, but food falling off your fork at dinner as you awkwardly tried to get this adult-sized utensil into your child-sized mouth would launch some kind of international incident. It always ended with slamming doors and crying and him storming out and me climbing up into the treehouse to write some other life in my head.

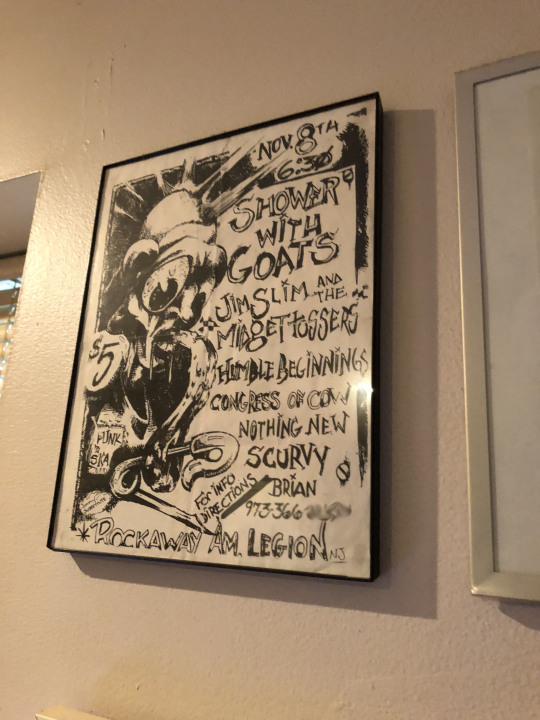

The flyer, because it was 1997, had a phone number to call “for directions or sex advice.” I blacked out that second part before I showed it to my parents, marching into our kitchen with this photocopied paper adorned with a giant hand-drawn, bug-eyed and bemowhawked creature with a safety pin through its tongue, the names of a bunch of bands they wouldn’t have known even if their entire record collection wasn’t The Kingston Trio, the soundtrack to The Big Chill and Donald Fagen.

I didn’t know the bands, either, really, but I knew I needed to go to this thing and see it. And so I also armed myself with an argument for why I should be allowed to go. Instead, I just got a “yes.” Simple. Too easy. My father, for all the other stuff, became his opposite self when it came to matters of music.

That November night in the American Legion, I found the thing I didn’t know I’d been looking for for all of the 15 years and four months of my life before it. My home, my people, my thing. My father came to pick us up at the end, and I surely got back in the car, tired and happy and smelling of cigarettes, but really, I never left.

Twenty-one years later that flyer hangs on the wall of my apartment.

Through the rest of my high school life, I’d check out the arts listings in the paper, picking out concerts and pulling out the phonebook so my parents could call Ticketmaster, using the money I’d made from working at the family business and then my job at the mall to finance these miniature adventures. And every time, my father would volunteer his services as driver, dutifully dropping us off somewhere in the middle of Manhattan so that we could enjoy a night with The Offspring.

Once I could drive, we’d spend weekends traversing the state following handwritten directions scribbled on a pick from the stack of flyers we’d been handed at the previous show. Living in all the wonder that comes with the kind of places willing to host an afternoon of complicated-looking kids too into something that was mostly dissonance and sometimes childhood music lessons repurposed into bad Bosstones knockoffs. Elks lodges, VFW halls, American Legions, firehouses, basements, the storefront of a diet food restaurant, high school gyms and random rooms in churches.

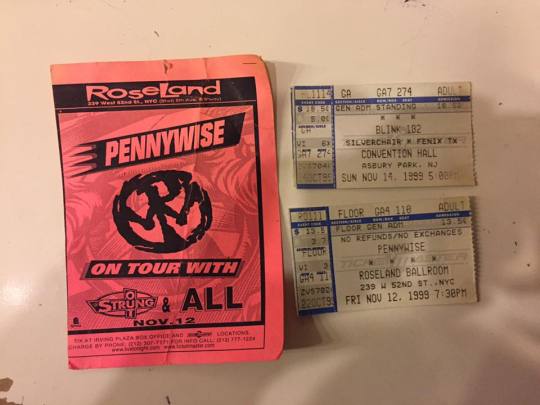

Then we’d take the train into the city and see the bigger touring bands that came through. Take a quarter for the payphone to call my mom from Penn and let her know the train didn’t derail on the way. Take the Midtown Direct from Dover for Pennywise, All and Strung Out in the city on Friday, drive to Asbury Park for Blink 182, Silverchair and Fenix TX on Sunday, go to school on Monday. Lars Frederiksen stealing my friend’s lighter outside a Dropkick Murphys show at the Wetlands. Smoking in the downstairs of Roseland as we browsed the tables of patches and buttons that lined the room. Summers with multiple Warped Tour dates, a car accident on the way to Asbury leaving the front passenger side door of my ’95 Golf in a permanent state of not closing right, our nostrils still filled with dust from Randall’s Island the day before.

Then, college, a degree I'd never get and mostly shitty jam bands in a small market city not on the way to anywhere. The other nights, more special. When Rainer Maria came to Higher Ground or AFI played at 242. River City Rebels with Catch 22 at a barn in rural Vermont or Bane in the middle of winter in some school gym. Kill Your Idols and Sworn Enemy and Agnostic Front and My Revenge and the show stopping to throw out some boneheads after they tried to rip a SHARP patch off a kid’s jacket. That night Death Cab played at UVM and someone from the band chased a kid who threw a disc golf disc onto the stage through the halls of whatever building that was. That same place where I saw Q and Not U and I think the only two times I was ever in that building. Our little NJ Scene expat crew, four people strong, watching some punk show on the second floor of the extra-strength hippie dorm.

Post-weird four year exile in Vermont, our little Jersey scene had shifted and died and grown up too much, but the city was still there. I’d learned by then never to take New York for granted. I went to shows.

So many.

Our Wilco/Ryan Adams cousins crew getting too drunk in Brooklyn bars and me as the only one over 21 buying bodega tallboys for everyone to drink from brown paper bags in Greeley Square. Getting lost in Macy’s and losing the car in midtown and getting actually lost on the way back from Camden. Perfect nights walking around Williamsburg and sunny Saturdays in Greenpoint and spending the night on Saint Marks after the War on Drugs got rained out. Happy hours at Matchless and tacos at that spot in Port Chester. The conversation before the Ty Segall show that started with me being excited for my friend and ended up with me on Uncle Einar’s first tour two months later. Too hyped after Run the Jewels and dropping my car key in a rest stop toilet because I hadn’t slept and went to see Rancid and Dropkick anyway. Too much whiskey and the side-effects of a tetanus shot and 13 staples in my leg and a Titus Andronicus show at Maxwell’s that I don’t remember. Getting a contact lens straight kicked out of my eye at that Vandals show at Irving Plaza. The lost weekend that was Punk Rock Bowling.

Plenty of solo trips, too, not wanting to miss what could be — because you never know — some band’s last time, and I’m not even going to bother trying to sell it to my friends. Sleater-Kinney five times in a week, the Piebald reunion, the sweatiest night ever when the AC broke at Webster Hall during the Bouncing Souls, and a fear of frostbite at Sonic Youth after putting a Chuck Taylor-clad foot into the depths of one of those curbside lakes the New York winter creates.

A thousand more that escape me now, but show me the ticket stub and I'll tell you the story.

The one constant is noise. There is always noise. The expected kind, of the band and the crowd cheering and singing along. And the annoying kind, of the full-on conversations everyone’s having as the band plays ten rows up, like the Bowery Ballroom is just an extension of their living room.

There is nothing better than a full-crowd singalong.

There is nothing worse than the people behind me at Sleater-Kinney’s first NYC show in nearly a decade having a full-on conversation — as the band was ripping through ‘Start Together’ or whatever — about an article one of them read about a Maraschino cherry factory that was illegally dumping whatever the byproducts of Maraschino cherry-making are into some Brooklyn waterway. It is a bonkers story that also involves a secret basement pot growing operation, but also, in the words of the great Sue Simmons, “the fuck are you doing?”

But both of those parts are also what make up the show. We’re in a room, simultaneously strangers and best friends. Together, doing a thing. That the gaps between songs are filled by this low mumble, that the band sometimes gets treated like nothing more than a backing track to an evening, because this is New York and we’re still too busy to even take this part out of our day to make it an actual part of our day.

There is some strange comfort in that noise, all of it, together.

This night, back at White Eagle, is different. It is silent. Starkly so. In an hour, I will be — we all will be — spit back out into New Jersey’s endless winter, down the steps and onto Newark Avenue, having learned no more about Maraschino cherries than we knew before we entered. I will hear nothing about who’s lunch Susan stole from the fridge at work today, or just how fucked up it was to get to Jersey from Ridgewood on a Tuesday night.

The only conversations I will hear are ones of faintly whispered commentary about how good this is. About “thank you for bringing me.” About “this is amazing.” And at first, it’s weird and jarring and uncomfortable, and every time another beer gets cracked at the bar the people all around me let out some barely audible groan, because for the first time at any show I’ve ever been to, we’re all sitting in that silence, and none of us know how to behave.

The show opens with ‘Over’ and ‘Appointments’ and no one even knows what to do when that’s over. Like, none of us know if we should even clap. Forever and ever, before and after this, the answer is obvious, but here, we’re all in some kind of silent agreement that there’s at least a question as to whether anything should pierce the quiet. Like we’d be as annoying as another person’s vodka soda order being fulfilled if we did.

Slowly, somewhere around the end of ‘Turn Out the Lights,’ we all agree to figure out if clapping is okay. Then light cheering. Eventually we’ve navigated it, all settled into a balance between the silence and the act of being at a show. Some of the people around me even risk a low singalong during parts of ‘Rejoice’ and that one part of ‘Everybody Does’, though the intermittent activity at the bar is still at least as loud.

And maybe, beyond the lack of talking, that’s why I’m so shaken and uncomfortable with this silence. Life is about noise, even in the background. A podcast, music, the TV I’m not watching. The fan that runs at night just so I can sleep. The silence outside my parents’ house makes me uneasy. I am home with sirens piercing the pre-dawn air. Stop the noise and the quiet can make things deafening in your head.

Shows are ringing ears and not knowing if you’re shouting at each other when you talk about how good it was on the way home. Why in some other social setting you’ll find me nodding in agreement even though I didn’t really hear what you just said. It is inherently about noise and sound taking over a room and taking everyone in that room with it.

Here, we’re trying to navigate that same journey with the quiet. Like turning up the volume on the car radio as you try to find your turn.

The thing I know about Julien Baker, because maybe I read The New Yorker while I’m brushing my teeth, is that she came up in some kind of punk scene that I imagine was similar to, though at least a decade and many states removed, from the one I did. Sonically, her music, just a guitar and some loops and piano and the occasional string accompaniment, is miles away from the basements and VFW halls and Elks lodges where I spent my teenage years. But it’s familiar somehow, too.

Maybe it’s because she’s here, on Tuesday night that’s too cold for April, mostly alone on stage, with just her songs and a couple guitars, a pedal board, a piano, and someone sometimes popping up to play violin, and she’s gotten this entire crowd to stop, to be quiet and sit in this silence and in these songs and find solace or something like it, in it, in them, in this. And that? That’s about as loud, and as punk rock, a thing as you can do.

1 note

·

View note