#i only have three more days to decide and cast my extremely influential vote (it won't matter but still)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

So, you should vote for Bill/Heather. Why? Oh, i'm glad you asked. That's because

[id: supernatural screenshot that reads "Gay love can pierce through the veil of death and save the day. end id]

Need i say more?

.

.

.

Fuck yeah of course i do.

You see, i think that a ship is objectively good not because it's cute or beloved, but because the dynamics are interesting. The more fucked up the dynamic is, the better. And Bill and Heather are an incredible duo and it's a little bit insane when you think about it.

On the one hand we have Heather. Don't get me started on Heather i think she is a fascinating character. She is unhappy whenever she is, and any place and situation she's in - she wants to leave. As they say, you can run but anywhere you go you still bring yourself with you. She feels that she is both the labyrinth and the monster trapped in the middle of it. The only happiness she finds is when she stops being what she used to be, when she has the power to become literally whatever whenever, manipulate her own atoms on a whim, when she can spread herself across time and space like butter on warm toast and become one with the universe. Is it trans-coded or am i delusional? (not the time-space butter thing, but the rest - you know what i mean) (also, if something about it is somehow off-colour, forgive me, i try my best but i might miss some nuance).

And then on the other hand we have Bill. Who knows and loves herself so well that even the Doctor can't change her, for better or for worse. Her sense of self and her comfort in her own mind and body are so strong that she can resist extreme brainwashing. And even cyberconversion, which is not even about washing your brain. They literally took her brain, took it apart, assembled it into something else entirely, and she still came out on the other end as herself. And still gay. Good for her.

And somehow those two are into each other. It's the "I don't want to live, if i can't be me anymore" + "i am ready to rewrite my whole entire being and kill everything that i'm supposed to be if it gives me freedom" that does it for me. Bill is Heather's anchor, Heather is Bill's lifeboat. Notice the nautical/water theme.

Can we also talk about their respect for each other's boundaries tho? How Bill is not pushing when she thinks Heather is not interested in her and freaked out after the first puddle incident. Heather doesn't transform Bill without her consent, and later does it only in the very last possible moment before Bill's implied death inside of that cybersuit. (My personal headcanon is that the Pilot can only take those who want to leave - that's why it latched onto Heather - and that was the only moment when Bill actually, genuinely wanted to leave (die), because before that she had hope or purpose, but in that moment she shed the first tear of true desperation).

I like their little flirty interactions as well, those two are adorable

BILL: Can I come too? HEATHER: Maybe.

BILL: Am I dead? HEATHER: Does that feel dead to you?

BILL: How can you fly the Tardis? HEATHER: I'm the Pilot. I can fly anything. Even you.

Heather is so cheeky lmao.

And it's not all

They've spent like a year pining after each other and barely making a move, useless lesbians nation rise

They are the motiff of "Love is not an emotion. Love is a promise" reprising, but now gay

They are sun and moon sapphics, which i always love

And again! They are! Immortal sapphics! Flying through time and space! In canon!!! What else can you want???

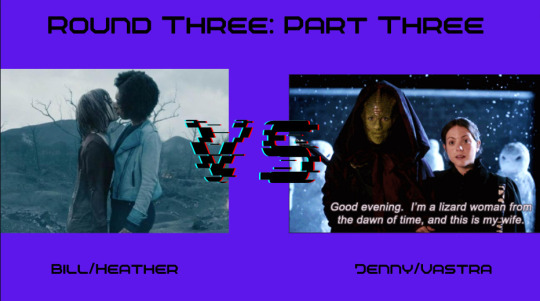

Which is the Better Doctor Who Ship?

Canon Lesbians vs Canon Lesbians! Who will emerge victorious for the semifinals?

[Image Description: A blue slide showcasing pictures of the competing ships, Bill/Heather and Jenny/Vastra It has a large VS between them]

#i'm writing this to convince myself lmao#because i still can't choose between those two ships i love them both too much#but i think i did a good job spread this so that someone can be swayed to vote for my girlies#or maybe so that someone gets so pissed on vastra and jenny's behalf that they write more propaganda for victorian wives#also someone please do write more propaganda for literally any of them two#i only have three more days to decide and cast my extremely influential vote (it won't matter but still)

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

All throughout this crazy year, I have been inviting people to vote. There are stark reminders every day of the difference between bad or absent or incompetent or self-serving “leadership”, and what’s possible under competent leaders. And so today I’d like to extend a special invitation to those who say “My vote doesn’t matter” with these responses…

My vote doesn’t matter; TLDR version: In short, this question: if your vote doesn’t matter, then why are they doing all they can to violate your right to vote, both in ability and in its impact? Whether it be by closing polling places, or implementing unnecessary and onerous voting ID and registration issues, or making information difficult to discover, or participating in extreme gerrymandering, or linking voting rights to the paying of fines and fees, or attacking mail in voting, or creating a false panic about fraud, or simply to engage in behavior that is designed to put you off voting, there is so a lot being done to decrease voter turnout. And they cement it in place by fostering that very feeling you have, that feeling that your vote doesn’t matter. They want you to think it doesn’t matter, that it’s too hard, that you’re better off staying home and just not vote. Because they know that the less people vote, the easier it is for them to influence the outcome. The more people they can get to tune out, and the more roadblocks they can throw in the way, the greater the impact of their fervent base upon which they can count on to show up while at the same time making it easy for their base to vote. Which, in turn, makes it easy to gain the power. By doing all this they get to break the system and choose their electorate, not, as it should be, the other way around. To that, I say no. Please vote.

My vote doesn’t matter: I’m just one person: Well, yes, that is true, you are just one person. And so am I. And so are they. And so is everyone else. And that’s just it… keep adding all the “one persons” and in no time you’ve got a serious mass of people. Again, it’s falling into their wishes, that many people feel insignificant and so they don’t vote, which suddenly becomes a mass of people that aren’t voting. But just as the single sheet of paper does not weigh much, yet a case of paper weighs a whole lot, there is power in numbers. Please vote.

My vote doesn’t matter; I’m just one person, part 2: In addition to the above, there are dozens and dozens of recent elections where the margin of victory was decidedly small, as in the in the single digit percentages small. The last USA presidential election itself was decided by .09% of all votes cast. And given only 55% of people cast ballots, there were plenty of “doesn’t matters” who could have mattered and made a difference. Please vote.

My vote doesn’t matter; I’m in a place that always votes X anyway: Well, maybe that’s the case for certain races, but it’s not likely the case for all races, especially as we drill down to the local level. And every single race is important – most of what affects your day-to-day life isn’t what the President or Prime-Minister does, it’s what happens on your local council. Or at the county level. Or what the local attorney general does. Or, moving up, what happens at your State/Province level. And even at Federal level if you live in the USA, there are three different races going on at the same time (senate/house/president) and your vote can be highly influential in one of those arenas even if the other two are ‘locked up’. Plus, again, even in ‘sure bet’ races, when all the “don’t matters” choose to vote and make their voices known, surprises can happen. Please vote.

My vote doesn’t matter; They don’t cater to my needs or listen to my wants: So, here’s the thing about campaigns – they are just like sports. There are plays and strategies that are known to work that have been honed through repetition and countless games. And the winning play is to focus on those you know will show up at the polls. If the candidates are not listening to your requests, it may be because they have little incentive to do so. (This happened to one of the major candidates during the recent primary – they made their bid on enticing young voters who did not show up to vote, which, unfortunately, reinforced the status quo of only listening to those who are the most likely to show up at the polls.) It may seem like a chicken and egg problem, but if you want them to listen you need to show that you are part of the game. You need to vote and to let them see that you vote. Once you’re on the field, you have leverage. Once in the game, you have their ear. Then you can direct things in the direction you want. That’s what voting is for: to have a voice. Please vote.

My vote doesn’t matter; It’s all rigged anyway: For one, I’ll point to the above and say again that in the myriad of races there are some where rigging is not possible, or at least more difficult, and your vote can very much swing things. For two, one of the reasons that they can rig things is explicitly because people tune out and not vote, which grants them the reins to game the system and control things like districting (leading to extreme gerrymandering) or to engage in corruption with no one watching or pushing back. For three, even when things have been massaged and suppressed people showing up in big numbers can overrun the rigging and put in place candidates who can undo the mess. Please vote.

My vote doesn’t matter; They’re all jerks or crooks anyway: This is one of the “funny” things about how things shake out. If no one cares to watch the henhouse, then the foxes move in and take all the positions of power. Moreover, if everyone says only jerks or crooks take the job, then the only people who choose to go there are either already jerks/crooks or are willing to be such. It’s drifted to this point. It can be pushed back. Please vote.

My vote doesn’t matter; They’re all jerks anyway, part 2: Plus, consider that being a jerk is actually an explicit part their strategy to stay in abusive power by getting you to not vote. They want you to think all politicians operate like them such that you get so disgusted with the whole process that you tune out. Again, so much the better for them because they know with less turnout they can win and therefore continue their crooked and corrupt and crook ways. Attention and sunlight kills all that. Please vote.

My vote doesn’t matter; It’s too hard and confusing and I can’t spare the time and energy to do and really it’s simply easier for me to think I don’t matter: Yeah, it is easier to think that, isn’t it? They’ve put so much friction in the way that why bother, it’s just too much to deal with on top of everything else we’ve got to do. To that, two things. The first is that, fortunately, there are dozens of resources out there to take the confusion and the “hard” out of the way. In the USA, there’s vote.org to check your registration, there’s the aptly named YouTube series titled “How To Vote In Every State”, there’s Ballotpedia.org that provides in-depth overviews about races in your area (choose “What’s On My Ballot” from the sidebar). Or Google your city name + Sample Ballot. All sorts of places to give you the skinny on what’s at stake, and how to ensure your voice is heard.

The second brings us back full circle to that first TLDR point, which is that the hardness and confusion and disgust is very much a part of their strategy. To summarize this post here:

https://elfwreck.tumblr.com/post/626732289397833729/lynati-tzikeh-daltongraham-toddreu

Voting originally belonged to a very small class of voters (primarily white male landowners) and they have fought like hell to keep it from being extended to anyone else. Every time voting gets subjected to a constitutional test and a new group gets the voice to vote, this small class has worked tirelessly to make it difficult for that new group to actually exercise that right.

Forget voting as our “duty.” Think of voting as “how can I annoy those jerks?” and keep at the front of your mind those jerks are hoping you won’t show up to do it. And that they’ll outright lie and work to suppress the vote through false narratives, closing polling places, futzing up the mail, all the way down to literally removing people’s names improperly from voting records (as just came to light in GA).

So don’t just vote to Make a Better City/State/Province/Country. Vote to make those asses scared of you.

Please vote.

(And please remember that if you plan to vote absentee or by mail, please request your ballot now, do the research while it’s on its way to you, and complete and send it out (or drop it off to an approved location) as soon as you can.)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Resurrection - A Response to “Ireland: An Obituary” by John Waters

In his article for First Things, which describes itself as “America’s most influential journal for religion and public life,” John Waters casts the vote to repeal the 8th amendment to the Irish constitution on May 25th as the death of his country. On that day, he writes, “history seemed to have gone into reverse: the Resurrection behind, Calvary in front. On Friday, the Irish people climbed Calvary backwards, in the name of progress.” I knew from that first line that the Ireland he knows and the Ireland I know must be two very different places. Like most Irish women at home and abroad, I went to sleep the night of May 25th, when exit polls showed that the referendum had passed with 68% of the vote, scarcely allowing myself to believe that I would wake up in a world where Irish women were free. The next morning, though I may have been curled up under my blankets half a world a way in Canada, I felt as though I was with the thousands of women at Dublin Castle who were weeping in joy and relief as the results were made official, alternating between chants of “Yes!” and “Savita,” the name of an Indian immigrant who died of septic shock as a complication of miscarriage in 2012, after being denied an abortion five days earlier and being told “this is a Catholic country,” before breaking into a tearful chorus of Amhran na bhFiann, the national anthem. I spent the next forty-eight hours crying off and on, and I’d be lying if I said the teary spells have stopped completely, almost five days later. Before I go on, I want to make my opinion on this matter perfectly clear. I am Catholic. Abortion is not an easy topic for me, and I do believe that on some level, it involves the taking of a life. In Canada, the country that sectarian oppression led my family to before I was born, abortion is legal for any reason up to birth. I do not agree with that at all. But in Ireland, the 8th amendment created the opposite extreme- in making the life of the mother and the life of the fetus equal in all respects, women could not even have a termination for medical reasons unless her death was imminent. I say that because a potentially life-threatening situation, such as a lengthy miscarriage, which can lead to sepsis, was not enough to merit a termination- you had to actually be experiencing sepsis in order to be allowed an abortion. This is what killed Savita Halappanavar, the catalyst for this referendum. Personally, I believe that abortion should be allowed if the pregnancy poses risk to the health, including mental health, of the mother; if the baby is diagnosed with a fatal foetal abnormality such as anencephaly; and in cases of rape and incest. However, because I do not believe that anyone should be forced to disclose that they have been a victim of rape or incest in order to access health care, I believe that there should be a period in the first trimester during which abortion can be accessed upon request. The 8th amendment, however, went beyond prohibiting abortion in all cases. The law undermined the agency of women carrying wanted pregnancies to term, as it prevented women from accessing any sort of health care that may hurt the baby. I read one story of a women who was denied chemotherapy and ultimately died, only for her baby to die three days later. In short, the 8th amendment was a draconian law that shames any nation that considers itself modern. With that in mind, I invite you to take my hand and dive into dissecting Waters’ article. I decided to write this response on a whim at one in the morning, because a lot of things have made me really angry in the last few days, but nothing as much as this article. Let me tell you why.

Waters opens with “If you would like to visit a place where the symptoms of the sickness of our time are found near their furthest limits, come to Ireland. Here you will see a civilization in freefall, seeking with every breath to deny the existence of a higher authority, a people that has now sentenced itself not to look upon the Cross of Christ lest it be haunted by His rage and sorrow.” From the get-go, he is casting Ireland as some sort of hellish wasteland of sin more akin to Las Vegas than to a country where the Angelus is still broadcast on national TV and every single person I’ve ever met went to a Catholic school. As the western world goes, Ireland is behind the times, and certainly one of the most pious countries among its peers. I’m not saying Ireland has the same levels of religiosity as it did even 50 years ago, but 85% of its citizens identify as Catholic, and the handprint of the Church is all over its laws. In 2009, the Dáil (Parliament) passed a law implementing a €25,000 fine for blasphemy, and children must be baptized Catholic to be admitted into school- that’s the kind of fundamentalism we use to justify bombing Muslim countries. So is Ireland shaking off some of the influence of the Church? Absolutely, and thank God for that. But is it “a civilization in freefall, seeking with every breath to deny the existence of a higher authority?” Absolutely not. Could not be farther from it. A later paragraph begins with “For the first time in history, a nation has voted to strip the right to life from the unborn.” Is this true? Technically, but only because Ireland is the only country (to my knowledge) to ever have had the legal equality of the life of the mother and her unborn child enshrined in their constitution. That in and of itself ought to tell you something about Irish society- that abortion laws had to be changed by referendum rather than by legislation because an absolute ban was literally enshrined in the constitution. He continues: “The tenor of the contest has been so nauseating that the deepest parts of my psyche had begun to anticipate this outcome. It was little things: the frivolity of the Yes side: “Run for Repeal”; “Spinning for Repeal”; “Walk your Dog for Repeal”; “Farmers for Yes”; “Grandparents for Repeal,” which ought to have been “Grandparents for Not Having Grandchildren.” This, like the same-sex marriage referendum in 2015, was a carnival referendum: Yessers chanting for Repeal, drinking to Repeal, grinning for the cameras as they went door-to-door on the canvass of death.” Apparently, Waters has a problem with the fact that Irish people live normal lives, and don’t just spend their hours alternatively praying the rosary and making babies, as borderline-Orientalist caricatures from Americans would have you believe. What hurts me the most about this - this denial of normalcy, of modernity, the eschewing of activities such as spin class or walking your dog as something somehow out of reach of the constantly-praying people of the Emerald Isle - is that it comes from an Irishman. Growing up in Canada, I’ve grown used to foreigners, especially Catholics, having this mythologized idea of Irish society, as though time stopped for us in 1849. And I’ve grown used to other Catholics going into hysterics when we step out of line from this fantasy. But seeing someone who describes Ireland as the only home he’s ever known perpetuating the infantilizing and, frankly, almost racist idea that Irish people aren’t, for lack of a better word, normal- I can’t lie, it hurt. This, for me, has been the crux of the issue as I’ve debated the referendum results with non-Irish Catholics, or (even worse) Catholics of some vague and distant Irish descent, who maybe had a great-great-great grandparent come over on the coffin ships during the Great Hunger. There are 500,000 people of Irish descent in Canada, which makes up 15% of our population; likewise, in the US there are 33 million people who claim Irish descent, which makes up 10.5% of their population and dwarfs the all-island population of Ireland, which is about 6 million. Most of these people, however, are descendants of people who came during the Great Hunger or shortly thereafter. First generation Irish-Canadians (or Irish-Americans) like myself are extremely rare. Because of this, though Irish culture is very strong and certainly privileged in North America, there are few people here with an actual connection to contemporary Ireland. For this reason, the image of Ireland that’s held by “Irish” Catholics here is not realistic. Not only is Ireland imagined as a place where having 10 children is considered the average and no one has heard of birth control, but they think we actually like it that way. Catholics in North America treat Ireland as a dollhouse; a plaything. Of course, when you base your admiration and connection to a country on nothing but its (imagined) religiosity, you’re apt to want to dissociate yourself from it entirely if its people step out of line. I kid you not- I saw a fully Canadian girl proclaim in light of the passing of the referendum “Today I am not Irish.” Sweetie, relax. You never were. Furthermore, it does not escape me that these attitudes carry a distinct air of colonialism, which is problematic when you consider the fact that many North Americans look at Ireland as a country that only became (mostly) free because the Brits took pity on us and handed us the 26 counties to shut us up. So it’s bad enough to hear this from people who have never set foot in Ireland, but from someone who lived their his whole life? I felt betrayed. Heartbroken. And like I needed to say something. Like I needed to get the truth about Ireland’s tumultuous and oppressive relationship with the Catholic Church out to as many people as I could. In that moment I felt it became my duty to show the truth that every woman in Ireland knows to the world.

I can only hope that Waters was purposely misleading his American audience and didn’t actually believe what he said when he wrote “The spiritual reconstruction of Ireland that took place after the Famines of the 1840s placed mothers at its center: the moral instruments by which Irish families were to be brought back to the straight and narrow. Women were placed on a pedestal, their actions or demands immune from questioning by mere men. Add two dashes of feminism and you have an unassailable cultural force, which has now attained its apotheosis. “Trust women,” one of the many fatuous Yes slogans demanded. Trust women to kill their own children?” Excuse me... WHAT? Placed mothers at its center, immune from questioning by mere men?? I think I need to give you folks a hard dose of truth here. As everyone knows, England occupied and oppressed the people of Ireland for 800 years (and is still occupying and oppressing the people of the North - tiocfaidh ár lá). But what many people don’t know is that, throughout the last hundred years of British rule, the Catholic Church, seen by so many as the vehicle for Ireland’s resistance, was available to the highest bidder, which was the colonial administration every time. During the Great Hunger, which was not in fact a famine but a purposely orchestrated genocide, the Church was more than happy to let the people of Ireland starve, with nothing in the way of help besides promises that you would spend eternity in Hell if you accepted a bowl of soup from the Quakers. When Ireland won independence for the 26 counties in 1921, its dreams of self-determination were dashed by the Church, which quickly stepped into England’s place of controlling every aspect of our lives. No one had to carry this burden more than Irish mothers. From the 18th century until 1996, women considered “fallen” were put into Magdalene laundries- homes run by nuns, ostensibly with the intention of rehabilitating these girls into better Catholics. After the 1920s, the laundries took a turn from bad to disgusting, essentially becoming prison labour camps for all sorts of women- disabled women, petty criminals, and girls who were considered “loose,” but mostly unwed mothers. Here, these women were forced to perform hard physical labour up until and immediately following birth. Their children were taken from them immediately and sold to American families. Many of these women and children never saw each other again. Unable to see their babies, women endured the torture of not being able to express their breast milk, and were beaten for crying or complaining. The babies who died were buried in mass graves on unconsecrated ground. At one Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, Co. Galway, 796 babies were discovered buried inside a septic tank. The Bon Secours Home in Tuam operated from 1925 to 1961- this is not something out of pre-Industrial history. This happened within my parents’ lifetime. The domination of the Church in all areas of life meant that up until the 1980s c-sections were not performed in Ireland. Instead, difficult labours were handled with symphysiotomies- essentially the surgical breaking of the mother’s pelvis. This was done widely throughout Ireland and without consent. Women often were not told that it had been done until after their babies were delivered. So much for women’s “actions or demands immune from questioning by mere men.” Ireland, I am proud to say, has come a long way in the last few decades. In 1980, condoms became legal, and within my lifetime, the last Magdalene laundry closed and divorce, gay marriage, and emergency contraception were decriminalized. But the 8th amendment, inserted into the constitution in 1983, remained a major roadblock to women’s liberation. I wish I could say that I am sure that the people who wrote the 8th amendment did so innocently, without realizing how many women would die because of it and how many families it would traumatize, but looking at Ireland’s history, I can’t say I have that much faith that our institutions care about women. Savita Halappanavar is the most high profile case of the damage caused by the 8th amendment, but she is far from the only one. The lead-up to the referendum was defined by stories like hers, some from women who were lucky to survive, and some from the families of women who weren’t. Another famous story is that of Miss P, a pregnant woman who in 2014 was declared clinically braindead, but whose doctors refused to unplug her from life support because it would kill her baby. Her family, having just lost their daughter, wife, and mother, was forced to appeal to Ireland’s High Court so that she could be removed from life support and die and be buried with dignity. The court ultimately ruled in the family’s favour, but only because her baby had no prospect of surviving- not because using a brain dead woman as a baby incubator is fundamentally wrong and disgusting. Another section of stories that particularly touched me were those of families who received the devastating diagnosis of fatal foetal anomaly. One woman, after discovering that her baby had anencephaly (the absence of a major portion of the brain and skull), was told by her doctor “it’s going to be a long 20 weeks.” Many of these women and families made the decision to travel to England for a termination- a lonely and harrowing experience, which more often than not involved getting back on a plane the next day or even that night, still bleeding from the procedure and receiving their baby’s ashes in the mail three weeks later.

Waters begins to wrap up his article by stating about the image of Ireland as the Land of Saints and Scholars, “We now know it to be a legend long past its use-by date. The Irish of today are more likely to be among the looters and book-burners, the barbarians who value nothing but what is expedient.” He is both right and wrong. Ireland is indeed no longer a land of saints and scholars- but why should it be? That was a title given to us based on our history before the year 1000 AD. No other country in the world is expected to stagnate as Ireland is expected to. No one chides France for no longer being a country of crusaders, or China for abandoning its emperor. It’s worth noting that the Land of Saints and Scholars is a title given to us by foreigners, not by us ourselves. No country is single-faceted. Ireland was never just a land of saints and scholars; we are, and always have been, like every other country, a dynamic place. A changing place. A living place. Where Waters is wrong is his second sentence- looters, book-burners, barbarians. The only people who ought to be ashamed to call themselves Irish, the only people who disgrace their ancestors, are those who speak of their own people in this way. Book-burners? Trinity College Dublin is one of the top universities in Europe, where anyone can go and view the immaculately preserved Book of Kells. Barbarians? In the last 100 years, Ireland has invented the defibrillator, the ejection seat, the nickel-zinc battery, and radiotherapy. Does finally shaking off the oppressive shackles of the Church make us, and us women in particular, book-burning barbarians? Is Ireland’s worth based entirely on the degree of control held over it by Catholicism? Ireland is doubtlessly changing, but anyone who thinks that that change is for the worse rather than the better needs to check up on their history. There is a reason that Irish women from Dublin Castle to the Midlands to the Aran Islands and from Ontario to New York to Australia greeted the 26th of May with tears in our eyes and joy in our hearts. Those who attempt to make this referendum about abortion on demand and attempt to paint us as celebrating the death of our children are being willfully ignorant to the fact that this referendum was centred heavily not on abortion on demand but on women like Savita Halappanavar, who came to our country seeking a better life only to die too young because of the stranglehold the Church has on our society. Waters mocks the slogan “Trust women,” but that is really what this was all about. For 200 years, Irish women have been entirely robbed of our agency and our voice. Like Taoiseach (a word that I, unlike Waters, am not embarrassed to utter) Varadkar made clear, this week Ireland spoke loud and clear, telling the world that we are a compassionate country, that we are a dynamic country, and that most importantly, we are a country that trusts women. According to Waters, this referendum was a backwards walk from the Resurrection towards Cavalry, from life towards death. He could not be more wrong. The promise of the Resurrection brings to us a new day, a new dawn, a future where we are free from the shackles that previously held us down. In my eyes, and in the eyes of the vast majority of Irish men and women alike, May 25th was the beginning of a new Ireland. We turned our back on centuries of pain, suffering, and death, and took our first steps towards the light of compassion. May 25th was not a backward walk to Calvary- May 25th was a Resurrection.

-

For Savita. I’m sorry we let you down.

-

Here’s the link to the original article: https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2018/05/ireland-an-obituary

#8th amendment#repeal the 8th#together4yes#repealed the 8th#savita#savita halappanavar#ireland#irish politics#first things#catholic#táformná#abortion#pro-choice#pro-life#feminism#timesup#futureisfemale

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet The Most Powerful Political Organization In Washington

This article was originally published in the journal Democracy. Subscribe to it here, because why not?

WASHINGTON — Coverage of the influence of money in politics tends to suffer from the same weakness that all horse-race politics writing does: it almost never connects day-to-day movements to any broader reality or purpose. We learn about the size of ad buys or overall spending plans, but there’s no so what? Following the 2012 presidential election, the political press decided, rather unanimously, that all the talk about the Citizens United decision had been overblown because, after all, Democrats more or less matched Republicans on the spending front, a Democrat was reelected to the White House, and the party even hung on to the Senate, so no rich conservative was able to buy the election. Sure, Republicans later took over the upper chamber in 2014, but plenty of Democrats still managed to win.

This focus on campaigns and elections tends to exclude coverage of the political agenda itself. In other words, what is it that Congress and the regulatory agencies are thinking about and, just as importantly, not thinking about? And so this focus has missed one of the most fundamental transformations within our political system: the way in which corporate interests have moved the playing field away from party politics and into the bowels of agencies, courts, and Congress. The media have yet to figure out how to keep score. Author and journalist Alyssa Katz, in her new book The Influence Machine, charts the history and measures the power of one of the leading drivers of this shift, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which she calls the “single most influential organization in American politics” (as would anybody else writing a book on it).

The Chamber, unique in American politics, is the only organization that simultaneously spends big money on elections, lobbies Congress heavily, drills into the regulatory process and, if all else fails, drags the government to court. As Katz keenly observes, the Chamber routinely promises to spend eye-popping sums of money on federal elections, but then in its tax documents several months later reports spending far less. Its critics suggest the Chamber does spend the money and somehow hides it from the IRS, but more likely the organization is following in the footsteps of Mark Hanna, the 19th century Roveian consultant who helped get William McKinley elected in 1896. Before the campaign was over, he returned a sizable contribution, telling the donor they had more than enough money to win. The goal of business in politics is not to win elections or run up the partisan score; the goal, rather, is to make money. If that goal can be accomplished for less, all the better.

Katz doesn’t deliver many groundbreaking revelations; close Chamber watchers won’t learn much new. But hers is the first book-length exposé of a phenomenon that is generally known only deep inside Washington: namely, that the Chamber is not what it appears. The nonprofit Chamber’s official mission is “to advance human progress through an economic, political, and social system based on individual freedom, incentive, initiative, opportunity, and responsibility.” Beyond that, it is thought to be a coalition of business groups that collectively push for a free-market agenda aimed at improving the climate for business broadly. It is also often assumed to be a partisan operation aimed simply at electing Republicans. But, in fact, it’s neither of those things. Rather, it is a gun for hire, a façade that corporations can use, for a price, to do work in Washington that they would rather not have associated with their consumer brand. All of this, Katz argues convincingly, has often flown brazenly in the face of tax law, but power in Washington trumps both the spirit and letter of the law.

The Chamber is a gun for hire, a faade that corporations can use, for a price, to do work in Washington that they would rather not have associated with their consumer brand.

In 2005, the Federal Election Commission cast a 4-2 vote finding “preliminary evidence that . . . [Chamber head Tom] Donohue had violated federal law by steering corporate campaign contributions directly to a federal campaign committee in order to influence an election,” Katz reports. Similar movements of money had destroyed the career of Tom DeLay, but the Chamber came out just fine. After the commission settled the case, three commissioners voted in 2008 to reject the settlement, deadlocking the panel. It has been so since. “Again and again, in state elections and in federal ones, including presidential races, the U.S. Chamber and its affiliated organizations were operating as political organizations and effective ones at that. But as far as the IRS was concerned, they remained educational groups, free to do what they would with their funds,” she writes.

The Chamber stands for whatever it wants to, whenever it wants to, depending on who’s paying.

Thinking of the Chamber as an organization at all winds up missing the point. Yes, it has a headquarters — a hulking one that stares down the White House from across Lafayette Square — an HR department, water coolers, and so on. But knowing what can legally be known about the Chamber gets you almost nowhere. The Chamber, instead, stands for whatever it wants to, whenever it wants to, depending on who’s paying. It has become an essential cloak for corporate special interests looking to get in and out of Washington without anybody seeing.

For decades, the Chamber tried to be what it seemed to be: a respectable coalition of businesses. But it found itself neutered by its need for consensus—companies are all in competition, after all—and easily outmatched by the combined might of labor and consumer advocates throughout the 1970s. It also was distracted by the anti-communist paranoia that consumed much of the politically active business community after World War II.

The new model was launched secretly, first uncovered on a day where the news wound up being utterly ignored. Jim VandeHei, then a reporter with The Wall Street Journal, broke it on September 11, 2001: The Chamber was selling its advocacy services to specific industries and companies at quite specific price levels. Drug makers paid for cover in a fight over pharmaceutical prices, Ford wanted to beat back legislation sparked by the deadly tire failures on its Ford Explorers, and so on. (For businesses without any particular interest at the moment, the dues paid to the Chamber are better thought of as protection money: Nice company you have there — would be a shame if a little congressional curiosity should happen to it.)

Today’s Chamber addresses a central problem for businesses in Washington: While business and business owners in general might be broadly popular — the business of America is business, after all — the particular things that individual businesses want tend to be extremely unpopular. Oil companies fighting the acceptance of climate change, insurers opposing health-care reform, tobacco companies opposing smoking regulations, gas companies opposing fracking laws, and trucking companies opposing driver-fatigue rules don’t exactly capture the public’s heart. Since the public might be broadly sympathetic to business but not individual businesses, the Chamber offers to cloak corporate self-interest in vague principles. That means that the Chamber is generally incapable of or uninterested in thinking strategically about the direction of the country. Instead, it simply moves from skirmish to skirmish, leaving behind a scorched landscape.

Katz, who is also the author of the well-received and timely Our Lot: How Real Estate Came to Own Us, is a policy writer, a cultural critic, and a member of the New York Daily News editorial board. Throughout her career, she has leaned more toward research and synthesis than banging the phones and surfacing scandal. This is not a Game Change-style book that will put you inside turbulent meetings or in the heads of officials. Neither embittered former employees nor mischievous insiders are gossiping or sharing damning emails. Nobody’s cell phone lights up while driving their Audi on the GW Parkway, or the other sorts of obscure narrative details that populate a certain genre of Washington insider literature. Her book is no less rigorous for it, but the lack of intimacy with the key figures does serve to remove a sense of drama from the narrative, and the book becomes more a compilation of facts and events, a point-by-point indictment rather than a page-turning tale. Katz’s approach yields a thorough piece of work, but the lack of tantalizing scooplets that are the currency of Washington and New York publishing today will diminish its impact.

That’s a shame, because Katz builds what is a very strong case brick by brick, and it’s remarkable to watch the Chamber’s power rise chapter by chapter. The Chamber’s first foray into the pay-for-play game came just after the November 1994 GOP takeover of Congress, from the kind of industry that desperately needed cover: tobacco. “The Chamber has been kind of a weak sister in recent times,” one Philip Morris lobbyist wrote in a memo Katz relays. “However, based on a meeting we had with Chamber staff last week (and reflective of our sharp reduction in dues), the Chamber is eager to regain its former position of policy influence AND regain its stead in our once upon a time good graces.” The memo continues, “If we go to them with a specific action agenda, I believe they will do their utmost to attempt to see it through.” So on behalf of cigarette makers, the Chamber challenged the science around addiction and the link to cancer, lobbied Congress, went to court, battled regulators, and waged a public-relations campaign — in short, the all-in-one Chamber playbook.

“My goal is simple — to build the biggest gorilla in this town — the most aggressive and vigorous business advocate our nation has ever seen,” Donohue told a tobacco executive in 1998. Katz quotes one tobacco exec memo describing the approach: “Chamber is the client, PM [Philip Morris] stays in the background, Chamber handles the day-to-day.” But what does fighting for smoking have to do with the broader business climate? The Chamber just kind of made up a rationale. “One can only imagine which industry will be next,” Donohue wrote to Congress members, pretending his work on behalf of tobacco was motivated by a “first they came for the cigarette-makers”-style solidarity, rather than the paid service it was. “The gaming industry? The beer and wine makers? Over-the-counter pharmaceutical companies? Fast food?” asked Chamber strategist Bruce Josten.

Chamber is the client, PM [Philip Morris] stays in the background, Chamber handles the day-to-day. — memo from a Philip Morris lobbyist

For decades prior to its tobacco epiphany, the Chamber had largely walked softly, without a stick, through the streets of Washington. It came into being at the urging of President Taft, who wanted a more efficient way of knowing just what it was business wanted from the government. Birthed largely at the request of the government, it was given special tax-exempt status, which the organization today deftly exploits to keep its sources of funding hidden (the Chamber and its legal arm spent more than $200 million in 2012 and 2013, the most recent years tax documents are available — a figure that will presumably grow in 2016). That the Chamber, America’s great voice of free enterprise, was created by the government is, depending on how colored your politics are by vulgar Marxism, somewhere between deliciously ironic and entirely unsurprising.

The Chamber was established to operate mostly by consensus, which, as veterans of Occupy Wall Street know all too well, means that for decades it did very little in the way of operating. When it did, it did so in collaboration with — brace yourself — Democrats. And not just any Democrat, but that man himself. “Chamber president Henry Harriman, a former textile manufacturer, spent much of the spring of 1933 across Lafayette Square from the Chamber of Commerce headquarters, collaborating with [Franklin] Roosevelt’s brain trust to develop the National Recovery Act,” writes Katz. When the Supreme Court struck down the parts of the act the Chamber liked, and FDR moved forward with New Deal programs it didn��t, it presaged a decades-long run of impotence, punctuated by panics about communism.

So while the Chamber spent the middle part of the twentieth century bickering and licking its New Deal wounds, Big Labor ran up the score. Katz relays that when an 8 percent hike in Social Security payments was being considered, the Chamber politely suggested a more modest increase. It’s hard to remember or imagine today, but there was a time when Congress bowed before the might of the consumer lobby, and businesses panicked at word that Ralph Nader’s band of raiders had an eye on their enterprise — a moment in time that Katz captures with the help of a “Mad Men” episode. “Roger Sterling is on the phone with a client,” Katz writes. “ ‘Oldsmobile. He wants to know if there’s any way around Nader,’ Sterling tells Pete Campbell, his hand on the mouthpiece. Responds Campbell, without hesitating: ‘There isn’t.’ ”

The president of the Chamber in those days, Ed Rust Sr., not only acknowledged Nader’s sway, but even made the argument in 1973 that business was better off because of him, that Nader and business ought to want the same things. Nader and the Chamber could agree, Rust said, on “products that work as they are supposed to, on warranties that protect the buyer at least as much as the seller, on services that genuinely serve.” It was a different kind of Chamber, but the forces that would create the new one were already bubbling. Rust lasted less than a year.

For Katz, it was Tom Donohue who played the pivotal role in executing the new strategy, and she lays out just how instrumental this one man has been in shaping the Chamber and, with it, Washington politics. Donohue was right for the job because he was not a businessman. Rather, he rose up as a university fundraiser, then deputy assistant postmaster general of the United States, then a lobbyist for the trucking industry, which perfectly positioned him to understand how Washington works, shorn of any pretense about free enterprise or a “pro-business climate.” For Donohue, the climate is irrelevant. What matters is who’s paying the Chamber, and what they want for it.

Some critics of the Chamber have argued that its efforts have largely backfired because the top priorities of business — infrastructure investment, comprehensive immigration reform, and a stable business climate not shaken by random threats of debt default and government shutdowns — have been foiled by the very conservative element of the GOP it helped fuel in 2010. But that assumes the Chamber cares about the overall business climate; instead, with its nihilistic approach to politics and the economy, the Chamber can fail only if its particular project fails. And in the event that happens, it’s really a failure only if the Chamber manages to get blamed and loses clients as a result.

Even readers familiar with the Chamber’s reach into the political system will be taken aback by the breadth and depth of its ability to shape the very legal structures of states where it has key business. While the stories Katz pulls together were not entirely unknown to the public at the time, the Chamber’s involvement, and its wholesale strategic assault on state judiciaries, are brazen enough that the chamber could come to define our era of corporate capture of the levers of republican government.

One instance, in Illinois, was an all-out war for a judicial seat in order to sway the outcomes of two particular cases. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance had been tagged with a $1.05 billion judgment for systematically ripping off and deceiving customers. And a jury had awarded $10 billion in a judgment against Philip Morris, a penalty for its marketing of “light” cigarettes in a way that suggested they were somehow less harmful. The Chamber needed a candidate who’d rule the “right” way on those cases and, sure enough, one was recruited by a State Farm lobbyist. The company and the Chamber pumped millions into the 2004 race. It would be an interesting judicial system that submitted verdicts to the democratic process, allowing companies on the losing end to take their case directly to the public on appeal. It would be a strange one, but at least there would be a logic to it.

But the public debate in Illinois, of course, was not about whether the verdicts against State Farm and Philip Morris should stand. It was instead a standard political fight, fought over personalities with misleading-at-best claims made about each side. The Chamber won, and while the public might not have known what the reward would be for the victor, it soon became clear. Their candidate, now dressed in robes, cast the deciding votes to throw out the two verdicts. Were this merely a case of the Chamber finding a rare opportunity to exert outsized influence in one race, it would still be a remarkable turn of events. But it was just one of numerous cases documented by Katz, many of which only became exposed as Chamber projects long after voters had gone to the polls.

Katz does her level best to wind up on a hopeful note. The raw success of the Chamber’s model, she argues, could be replicated by progressive groups working in alliance with enlightened businesses toward a common goal:

The Democratic Party could use its own version of the Chamber of Commerce — an outside intervention to force dynamic change, and unite its own activists behind a common agenda and strategy that encompasses workers, consumers, and companies that care about their welfare. The Sustainable Business Council isn’t willing to wage a war in which money is the ammunition, but someone else will have to, and the world of dynamic new business powers is not impoverished. The combatants may end up being companies like Skanska and Apple that left the U.S. Chamber, disillusioned; perhaps Google will finally heed the ceaseless calls to drop its Chamber membership and find fresh avenues for influence. The same technologies that foster crowdfunding for emerging business à la Kickstarter also harbor tremendous potential to pull together funding for political action from a constellation of fragmented companies, empowering them to form their own lobbying and campaign-cash forces to disrupt legacy industries’ deep-pocketed lock on power.

As the Republican Party increasingly operates outside the realm of reason, it’s the Democrats’ turn to answer a call to duty, and to build a bridge for business to political power based on prosperity and social advancement.

We know the strategy works. After all, it’s been done before.

Setting aside the prospect of aligning Apple with workers’ rights groups, Katz’s prescription gets her own analysis wrong: The Chamber is not a real coalition, as she makes plain throughout the book. And the promise of secrecy it offers to, say, an oil company is not one needed by the Sierra Club. Environmental and consumer groups are just fine with the public knowing they are pushing for whatever they’re pushing for, and it does the project no harm for anybody to know it. They don’t need cover.

The prospect of crowdfunding in Washington has the potential to be real in some situations, but matching the scale of billionaire industrialists, who can easily chip in several hundred million per election cycle, is no easy task. What Katz finds is not that the Chamber has found a new way to win the game, but that it is, in significant ways, playing a different game entirely. While the parties jockey for position ahead of the next election, the Chamber plays for keeps.

from All Of Beer http://allofbeer.com/meet-the-most-powerful-political-organization-in-washington/ from All of Beer https://allofbeercom.tumblr.com/post/183299560867

0 notes

Text

Meet The Most Powerful Political Organization In Washington

This article was originally published in the journal Democracy. Subscribe to it here, because why not?

WASHINGTON — Coverage of the influence of money in politics tends to suffer from the same weakness that all horse-race politics writing does: it almost never connects day-to-day movements to any broader reality or purpose. We learn about the size of ad buys or overall spending plans, but there’s no so what? Following the 2012 presidential election, the political press decided, rather unanimously, that all the talk about the Citizens United decision had been overblown because, after all, Democrats more or less matched Republicans on the spending front, a Democrat was reelected to the White House, and the party even hung on to the Senate, so no rich conservative was able to buy the election. Sure, Republicans later took over the upper chamber in 2014, but plenty of Democrats still managed to win.

This focus on campaigns and elections tends to exclude coverage of the political agenda itself. In other words, what is it that Congress and the regulatory agencies are thinking about and, just as importantly, not thinking about? And so this focus has missed one of the most fundamental transformations within our political system: the way in which corporate interests have moved the playing field away from party politics and into the bowels of agencies, courts, and Congress. The media have yet to figure out how to keep score. Author and journalist Alyssa Katz, in her new book The Influence Machine, charts the history and measures the power of one of the leading drivers of this shift, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which she calls the “single most influential organization in American politics” (as would anybody else writing a book on it).

The Chamber, unique in American politics, is the only organization that simultaneously spends big money on elections, lobbies Congress heavily, drills into the regulatory process and, if all else fails, drags the government to court. As Katz keenly observes, the Chamber routinely promises to spend eye-popping sums of money on federal elections, but then in its tax documents several months later reports spending far less. Its critics suggest the Chamber does spend the money and somehow hides it from the IRS, but more likely the organization is following in the footsteps of Mark Hanna, the 19th century Roveian consultant who helped get William McKinley elected in 1896. Before the campaign was over, he returned a sizable contribution, telling the donor they had more than enough money to win. The goal of business in politics is not to win elections or run up the partisan score; the goal, rather, is to make money. If that goal can be accomplished for less, all the better.

Katz doesn’t deliver many groundbreaking revelations; close Chamber watchers won’t learn much new. But hers is the first book-length exposé of a phenomenon that is generally known only deep inside Washington: namely, that the Chamber is not what it appears. The nonprofit Chamber’s official mission is “to advance human progress through an economic, political, and social system based on individual freedom, incentive, initiative, opportunity, and responsibility.” Beyond that, it is thought to be a coalition of business groups that collectively push for a free-market agenda aimed at improving the climate for business broadly. It is also often assumed to be a partisan operation aimed simply at electing Republicans. But, in fact, it’s neither of those things. Rather, it is a gun for hire, a façade that corporations can use, for a price, to do work in Washington that they would rather not have associated with their consumer brand. All of this, Katz argues convincingly, has often flown brazenly in the face of tax law, but power in Washington trumps both the spirit and letter of the law.

The Chamber is a gun for hire, a faade that corporations can use, for a price, to do work in Washington that they would rather not have associated with their consumer brand.

In 2005, the Federal Election Commission cast a 4-2 vote finding “preliminary evidence that . . . [Chamber head Tom] Donohue had violated federal law by steering corporate campaign contributions directly to a federal campaign committee in order to influence an election,” Katz reports. Similar movements of money had destroyed the career of Tom DeLay, but the Chamber came out just fine. After the commission settled the case, three commissioners voted in 2008 to reject the settlement, deadlocking the panel. It has been so since. “Again and again, in state elections and in federal ones, including presidential races, the U.S. Chamber and its affiliated organizations were operating as political organizations and effective ones at that. But as far as the IRS was concerned, they remained educational groups, free to do what they would with their funds,” she writes.

The Chamber stands for whatever it wants to, whenever it wants to, depending on who’s paying.

Thinking of the Chamber as an organization at all winds up missing the point. Yes, it has a headquarters — a hulking one that stares down the White House from across Lafayette Square — an HR department, water coolers, and so on. But knowing what can legally be known about the Chamber gets you almost nowhere. The Chamber, instead, stands for whatever it wants to, whenever it wants to, depending on who’s paying. It has become an essential cloak for corporate special interests looking to get in and out of Washington without anybody seeing.

For decades, the Chamber tried to be what it seemed to be: a respectable coalition of businesses. But it found itself neutered by its need for consensus—companies are all in competition, after all—and easily outmatched by the combined might of labor and consumer advocates throughout the 1970s. It also was distracted by the anti-communist paranoia that consumed much of the politically active business community after World War II.

The new model was launched secretly, first uncovered on a day where the news wound up being utterly ignored. Jim VandeHei, then a reporter with The Wall Street Journal, broke it on September 11, 2001: The Chamber was selling its advocacy services to specific industries and companies at quite specific price levels. Drug makers paid for cover in a fight over pharmaceutical prices, Ford wanted to beat back legislation sparked by the deadly tire failures on its Ford Explorers, and so on. (For businesses without any particular interest at the moment, the dues paid to the Chamber are better thought of as protection money: Nice company you have there — would be a shame if a little congressional curiosity should happen to it.)

Today’s Chamber addresses a central problem for businesses in Washington: While business and business owners in general might be broadly popular — the business of America is business, after all — the particular things that individual businesses want tend to be extremely unpopular. Oil companies fighting the acceptance of climate change, insurers opposing health-care reform, tobacco companies opposing smoking regulations, gas companies opposing fracking laws, and trucking companies opposing driver-fatigue rules don’t exactly capture the public’s heart. Since the public might be broadly sympathetic to business but not individual businesses, the Chamber offers to cloak corporate self-interest in vague principles. That means that the Chamber is generally incapable of or uninterested in thinking strategically about the direction of the country. Instead, it simply moves from skirmish to skirmish, leaving behind a scorched landscape.

Katz, who is also the author of the well-received and timely Our Lot: How Real Estate Came to Own Us, is a policy writer, a cultural critic, and a member of the New York Daily News editorial board. Throughout her career, she has leaned more toward research and synthesis than banging the phones and surfacing scandal. This is not a Game Change-style book that will put you inside turbulent meetings or in the heads of officials. Neither embittered former employees nor mischievous insiders are gossiping or sharing damning emails. Nobody’s cell phone lights up while driving their Audi on the GW Parkway, or the other sorts of obscure narrative details that populate a certain genre of Washington insider literature. Her book is no less rigorous for it, but the lack of intimacy with the key figures does serve to remove a sense of drama from the narrative, and the book becomes more a compilation of facts and events, a point-by-point indictment rather than a page-turning tale. Katz’s approach yields a thorough piece of work, but the lack of tantalizing scooplets that are the currency of Washington and New York publishing today will diminish its impact.

That’s a shame, because Katz builds what is a very strong case brick by brick, and it’s remarkable to watch the Chamber’s power rise chapter by chapter. The Chamber’s first foray into the pay-for-play game came just after the November 1994 GOP takeover of Congress, from the kind of industry that desperately needed cover: tobacco. “The Chamber has been kind of a weak sister in recent times,” one Philip Morris lobbyist wrote in a memo Katz relays. “However, based on a meeting we had with Chamber staff last week (and reflective of our sharp reduction in dues), the Chamber is eager to regain its former position of policy influence AND regain its stead in our once upon a time good graces.” The memo continues, “If we go to them with a specific action agenda, I believe they will do their utmost to attempt to see it through.” So on behalf of cigarette makers, the Chamber challenged the science around addiction and the link to cancer, lobbied Congress, went to court, battled regulators, and waged a public-relations campaign — in short, the all-in-one Chamber playbook.

“My goal is simple — to build the biggest gorilla in this town — the most aggressive and vigorous business advocate our nation has ever seen,” Donohue told a tobacco executive in 1998. Katz quotes one tobacco exec memo describing the approach: “Chamber is the client, PM [Philip Morris] stays in the background, Chamber handles the day-to-day.” But what does fighting for smoking have to do with the broader business climate? The Chamber just kind of made up a rationale. “One can only imagine which industry will be next,” Donohue wrote to Congress members, pretending his work on behalf of tobacco was motivated by a “first they came for the cigarette-makers”-style solidarity, rather than the paid service it was. “The gaming industry? The beer and wine makers? Over-the-counter pharmaceutical companies? Fast food?” asked Chamber strategist Bruce Josten.

Chamber is the client, PM [Philip Morris] stays in the background, Chamber handles the day-to-day. — memo from a Philip Morris lobbyist

For decades prior to its tobacco epiphany, the Chamber had largely walked softly, without a stick, through the streets of Washington. It came into being at the urging of President Taft, who wanted a more efficient way of knowing just what it was business wanted from the government. Birthed largely at the request of the government, it was given special tax-exempt status, which the organization today deftly exploits to keep its sources of funding hidden (the Chamber and its legal arm spent more than $200 million in 2012 and 2013, the most recent years tax documents are available — a figure that will presumably grow in 2016). That the Chamber, America’s great voice of free enterprise, was created by the government is, depending on how colored your politics are by vulgar Marxism, somewhere between deliciously ironic and entirely unsurprising.

The Chamber was established to operate mostly by consensus, which, as veterans of Occupy Wall Street know all too well, means that for decades it did very little in the way of operating. When it did, it did so in collaboration with — brace yourself — Democrats. And not just any Democrat, but that man himself. “Chamber president Henry Harriman, a former textile manufacturer, spent much of the spring of 1933 across Lafayette Square from the Chamber of Commerce headquarters, collaborating with [Franklin] Roosevelt’s brain trust to develop the National Recovery Act,” writes Katz. When the Supreme Court struck down the parts of the act the Chamber liked, and FDR moved forward with New Deal programs it didn’t, it presaged a decades-long run of impotence, punctuated by panics about communism.

So while the Chamber spent the middle part of the twentieth century bickering and licking its New Deal wounds, Big Labor ran up the score. Katz relays that when an 8 percent hike in Social Security payments was being considered, the Chamber politely suggested a more modest increase. It’s hard to remember or imagine today, but there was a time when Congress bowed before the might of the consumer lobby, and businesses panicked at word that Ralph Nader’s band of raiders had an eye on their enterprise — a moment in time that Katz captures with the help of a “Mad Men” episode. “Roger Sterling is on the phone with a client,” Katz writes. “ ‘Oldsmobile. He wants to know if there’s any way around Nader,’ Sterling tells Pete Campbell, his hand on the mouthpiece. Responds Campbell, without hesitating: ‘There isn’t.’ ”

The president of the Chamber in those days, Ed Rust Sr., not only acknowledged Nader’s sway, but even made the argument in 1973 that business was better off because of him, that Nader and business ought to want the same things. Nader and the Chamber could agree, Rust said, on “products that work as they are supposed to, on warranties that protect the buyer at least as much as the seller, on services that genuinely serve.” It was a different kind of Chamber, but the forces that would create the new one were already bubbling. Rust lasted less than a year.

For Katz, it was Tom Donohue who played the pivotal role in executing the new strategy, and she lays out just how instrumental this one man has been in shaping the Chamber and, with it, Washington politics. Donohue was right for the job because he was not a businessman. Rather, he rose up as a university fundraiser, then deputy assistant postmaster general of the United States, then a lobbyist for the trucking industry, which perfectly positioned him to understand how Washington works, shorn of any pretense about free enterprise or a “pro-business climate.” For Donohue, the climate is irrelevant. What matters is who’s paying the Chamber, and what they want for it.

Some critics of the Chamber have argued that its efforts have largely backfired because the top priorities of business — infrastructure investment, comprehensive immigration reform, and a stable business climate not shaken by random threats of debt default and government shutdowns — have been foiled by the very conservative element of the GOP it helped fuel in 2010. But that assumes the Chamber cares about the overall business climate; instead, with its nihilistic approach to politics and the economy, the Chamber can fail only if its particular project fails. And in the event that happens, it’s really a failure only if the Chamber manages to get blamed and loses clients as a result.

Even readers familiar with the Chamber’s reach into the political system will be taken aback by the breadth and depth of its ability to shape the very legal structures of states where it has key business. While the stories Katz pulls together were not entirely unknown to the public at the time, the Chamber’s involvement, and its wholesale strategic assault on state judiciaries, are brazen enough that the chamber could come to define our era of corporate capture of the levers of republican government.

One instance, in Illinois, was an all-out war for a judicial seat in order to sway the outcomes of two particular cases. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance had been tagged with a $1.05 billion judgment for systematically ripping off and deceiving customers. And a jury had awarded $10 billion in a judgment against Philip Morris, a penalty for its marketing of “light” cigarettes in a way that suggested they were somehow less harmful. The Chamber needed a candidate who’d rule the “right” way on those cases and, sure enough, one was recruited by a State Farm lobbyist. The company and the Chamber pumped millions into the 2004 race. It would be an interesting judicial system that submitted verdicts to the democratic process, allowing companies on the losing end to take their case directly to the public on appeal. It would be a strange one, but at least there would be a logic to it.

But the public debate in Illinois, of course, was not about whether the verdicts against State Farm and Philip Morris should stand. It was instead a standard political fight, fought over personalities with misleading-at-best claims made about each side. The Chamber won, and while the public might not have known what the reward would be for the victor, it soon became clear. Their candidate, now dressed in robes, cast the deciding votes to throw out the two verdicts. Were this merely a case of the Chamber finding a rare opportunity to exert outsized influence in one race, it would still be a remarkable turn of events. But it was just one of numerous cases documented by Katz, many of which only became exposed as Chamber projects long after voters had gone to the polls.

Katz does her level best to wind up on a hopeful note. The raw success of the Chamber’s model, she argues, could be replicated by progressive groups working in alliance with enlightened businesses toward a common goal:

The Democratic Party could use its own version of the Chamber of Commerce — an outside intervention to force dynamic change, and unite its own activists behind a common agenda and strategy that encompasses workers, consumers, and companies that care about their welfare. The Sustainable Business Council isn’t willing to wage a war in which money is the ammunition, but someone else will have to, and the world of dynamic new business powers is not impoverished. The combatants may end up being companies like Skanska and Apple that left the U.S. Chamber, disillusioned; perhaps Google will finally heed the ceaseless calls to drop its Chamber membership and find fresh avenues for influence. The same technologies that foster crowdfunding for emerging business à la Kickstarter also harbor tremendous potential to pull together funding for political action from a constellation of fragmented companies, empowering them to form their own lobbying and campaign-cash forces to disrupt legacy industries’ deep-pocketed lock on power.

As the Republican Party increasingly operates outside the realm of reason, it’s the Democrats’ turn to answer a call to duty, and to build a bridge for business to political power based on prosperity and social advancement.

We know the strategy works. After all, it’s been done before.

Setting aside the prospect of aligning Apple with workers’ rights groups, Katz’s prescription gets her own analysis wrong: The Chamber is not a real coalition, as she makes plain throughout the book. And the promise of secrecy it offers to, say, an oil company is not one needed by the Sierra Club. Environmental and consumer groups are just fine with the public knowing they are pushing for whatever they’re pushing for, and it does the project no harm for anybody to know it. They don’t need cover.

The prospect of crowdfunding in Washington has the potential to be real in some situations, but matching the scale of billionaire industrialists, who can easily chip in several hundred million per election cycle, is no easy task. What Katz finds is not that the Chamber has found a new way to win the game, but that it is, in significant ways, playing a different game entirely. While the parties jockey for position ahead of the next election, the Chamber plays for keeps.

from All Of Beer http://allofbeer.com/meet-the-most-powerful-political-organization-in-washington/

0 notes

Text

Meet The Most Powerful Political Organization In Washington

This article was originally published in the journal Democracy. Subscribe to it here, because why not?

WASHINGTON — Coverage of the influence of money in politics tends to suffer from the same weakness that all horse-race politics writing does: it almost never connects day-to-day movements to any broader reality or purpose. We learn about the size of ad buys or overall spending plans, but there’s no so what? Following the 2012 presidential election, the political press decided, rather unanimously, that all the talk about the Citizens United decision had been overblown because, after all, Democrats more or less matched Republicans on the spending front, a Democrat was reelected to the White House, and the party even hung on to the Senate, so no rich conservative was able to buy the election. Sure, Republicans later took over the upper chamber in 2014, but plenty of Democrats still managed to win.

This focus on campaigns and elections tends to exclude coverage of the political agenda itself. In other words, what is it that Congress and the regulatory agencies are thinking about and, just as importantly, not thinking about? And so this focus has missed one of the most fundamental transformations within our political system: the way in which corporate interests have moved the playing field away from party politics and into the bowels of agencies, courts, and Congress. The media have yet to figure out how to keep score. Author and journalist Alyssa Katz, in her new book The Influence Machine, charts the history and measures the power of one of the leading drivers of this shift, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which she calls the “single most influential organization in American politics” (as would anybody else writing a book on it).

The Chamber, unique in American politics, is the only organization that simultaneously spends big money on elections, lobbies Congress heavily, drills into the regulatory process and, if all else fails, drags the government to court. As Katz keenly observes, the Chamber routinely promises to spend eye-popping sums of money on federal elections, but then in its tax documents several months later reports spending far less. Its critics suggest the Chamber does spend the money and somehow hides it from the IRS, but more likely the organization is following in the footsteps of Mark Hanna, the 19th century Roveian consultant who helped get William McKinley elected in 1896. Before the campaign was over, he returned a sizable contribution, telling the donor they had more than enough money to win. The goal of business in politics is not to win elections or run up the partisan score; the goal, rather, is to make money. If that goal can be accomplished for less, all the better.

Katz doesn’t deliver many groundbreaking revelations; close Chamber watchers won’t learn much new. But hers is the first book-length exposé of a phenomenon that is generally known only deep inside Washington: namely, that the Chamber is not what it appears. The nonprofit Chamber’s official mission is “to advance human progress through an economic, political, and social system based on individual freedom, incentive, initiative, opportunity, and responsibility.” Beyond that, it is thought to be a coalition of business groups that collectively push for a free-market agenda aimed at improving the climate for business broadly. It is also often assumed to be a partisan operation aimed simply at electing Republicans. But, in fact, it’s neither of those things. Rather, it is a gun for hire, a façade that corporations can use, for a price, to do work in Washington that they would rather not have associated with their consumer brand. All of this, Katz argues convincingly, has often flown brazenly in the face of tax law, but power in Washington trumps both the spirit and letter of the law.

The Chamber is a gun for hire, a faade that corporations can use, for a price, to do work in Washington that they would rather not have associated with their consumer brand.

In 2005, the Federal Election Commission cast a 4-2 vote finding “preliminary evidence that . . . [Chamber head Tom] Donohue had violated federal law by steering corporate campaign contributions directly to a federal campaign committee in order to influence an election,” Katz reports. Similar movements of money had destroyed the career of Tom DeLay, but the Chamber came out just fine. After the commission settled the case, three commissioners voted in 2008 to reject the settlement, deadlocking the panel. It has been so since. “Again and again, in state elections and in federal ones, including presidential races, the U.S. Chamber and its affiliated organizations were operating as political organizations and effective ones at that. But as far as the IRS was concerned, they remained educational groups, free to do what they would with their funds,” she writes.

The Chamber stands for whatever it wants to, whenever it wants to, depending on who’s paying.

Thinking of the Chamber as an organization at all winds up missing the point. Yes, it has a headquarters — a hulking one that stares down the White House from across Lafayette Square — an HR department, water coolers, and so on. But knowing what can legally be known about the Chamber gets you almost nowhere. The Chamber, instead, stands for whatever it wants to, whenever it wants to, depending on who’s paying. It has become an essential cloak for corporate special interests looking to get in and out of Washington without anybody seeing.

For decades, the Chamber tried to be what it seemed to be: a respectable coalition of businesses. But it found itself neutered by its need for consensus—companies are all in competition, after all—and easily outmatched by the combined might of labor and consumer advocates throughout the 1970s. It also was distracted by the anti-communist paranoia that consumed much of the politically active business community after World War II.