#i love subcomandante marcos

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I was tagged by @sohelpmegod, by my @icedtabasco, to post the first 9 photos to show up on a Pinterest feed. I didn't have a Pinterest before now. These are some of the result after some time in that platform.

@brave-olive, @wa1kingcorpse, anyone (if you'd like to) :]

#i don't know how to use pinterest#i don't understand it either#i love subcomandante marcos#thanks for the tag

55 notes

·

View notes

Note

what's on your secret internal moodboard for your wake/g1d/pyrrha trifecta, esp with the first two (since pyrrha gets a lot of love as it is)? what are the biggest wellsprings you're drawing from/aiming for with everyone's favorite scourgin' mary and inverted brutus?

i could smack a big kissy on your face for such an apropos question !

wake

is everything to me. obviously. what matters to me with her is contextualizing her canonical violence and wrath (like achilles' wrath... HELLO... she's a mortal woman whose wrath dares to reach the heights of the gods and which ultimately destroys her...) in light of her role as the leader of a revolution. she's literally not purposelessly angry or purposelessly violent. I already blew up someone else's inbox about this today lol but imo the books portray BOE as a whole in kind of a clueless way from the liberal exterior viewpoint, that doesn't really get into what a revolutionary movement would themselves value and hold as their norms & ethics. and in regard to that, how and why they use violence, and how and why violence is so much a part of wake's language.

I'm reading the zapatista reader atm and have been for the last few months, not that i really see wake as a subcomandante marcos figure because she's not as much of a speaker/demagogue, more so that much like the indigenous resistance in chiapas the sheer cultural, linguistic, and political polyphony of any BOE organization must mean that wake is a brilliant, compelling figure that people want to follow. she's not a violent brute (one way she's often depicted in fandom too...) she's a POLITICAL LEADER who has united MULTIPLE WINGS THAT OPERATE COMPLETELY SEPARATELY to accomplish HUGE OPERATIONS THAT SEVERELY STRUCK AT THE ROOTS OF THE DEEPLY ENTRENCHED EMPIRE. like... she's 100% a compelling speaker and leader and someone you trust and want to follow into suicide missions, because you know she'll bring you success. and she had and did! you can't be stupid with how you use violence and achieve that level of success!

and the one thing you need to add to wake to make canon click with her humanity is literally just that—her internal truth and her humanity. the reason why she's doing what she's doing. because the cruelty of the empire broke her heart and she has enough life and fire overflowing in her to want to keep that from happening to anyone else. the rest all falls into place once you start writing her like that

I also see her as a figure of classical greek tragedy—she's the ultimate example of being destroyed by hubris (trusting a lyctor!!), and compared to the other two points of the triangle she's the most fragile and mortal, yet also the most explosive and larger-than-life. her life is a brief yet enormous blaze compared to g1deon's eternal stonelike misery and pyrrha's lone, flickering star. and because she pursued life so hungrily and overreached in striving with the gods for greatness (there we go with achilles again), she was always doomed to death. the domain of her lifelong hated enemy. wow someone should write some dactylic hexameter greek epic poem-style about her confrontation with her own mortality in the river and how her religious beliefs are thereby challenged and her rage is fanned enough to turn her into a revenant ^_^ ahem ahem

also i think because her main squeeze has a cock people are always making them fuck PIV style and i think that's boring tbh. i mean yes it's fun and sexy and we all love a good dicking down (well many of us) but i like having her and pyrrha fuck queer style because i think it's more reflective of her character to break boundaries, fuck with traditions, be a cunt who devours and circludes, violate the norms of cav-necro penetrative erotics, and aggressively top in pursuit of her own pleasure (in addition to which... well see the last paragraph of my pyrrha answer)

i also didn't even get into the virgin mary thing but in my BOE griddlehark fic i have kind of a marian ancestor worship cult around wake (props to @katakaluptastrophy for providing the thinking behind BOE's animist ancestor worship religion) and in my dactylic hexameter thing i have a big list of epithets by clarissa pinkola estés for the virgin mary/the madonna/the wild mother: obsidian blade... the undoer of knots... she who carries the soul across fenced frontiers... the shirt of arrows... the black madonna...

also listen to this impeccable wake playlist which I'm pretty sure is by @dve if i'm am not mistaken

g1deon

is ofc the dark horse in both the books and the resultant fandom. i've already written at length about what a disservice i feel both the books and fandom have done his character (try clicking 10 random wake/pyrrha fics and NOT finding a scornful comparison of how shitty a lover g1d is or what a douche he is generally as a tactic to differentiate him from pyrrha).

so for me what's important to him, and what defines his character, is the sacrifices he makes for john both pre- and post-rez. he's hector, he's the archangel michael, he's the archetype of warrior manhood !but! in an utterly self-abnegating way. this is one facet of the way john's necromancy takes everything positive (in the +-charged sense, not in the yay happy sense) and turns it inward, perverted, and starved.

unlike a man raised in a patriarchal warrior culture, g1deon has no pride or identity in his kills and the sacrifices he makes to accomplish them, and he has no brotherhood. the two people he truly loved were both women, and he killed them both for the sake of john's goals. and he used to have a brother, even, he and john used to be brothers, but john removed himself from that role w/ g1deon for the pursuit of power.

so any way i choose to depict g1deon will be as 1) someone with dignity and selfhood in a way that the fandom only rarely seems to think he deserves, and 2) someone with a heart who has loved and lost in the name of devotion. not that he's a soft man or that he hasn't done atrocious things in john's name. but it's just to counterbalance his book&fandom portrayal in a way i feel is more fair and interiorizing.

anyway stream swim good that's basically everything I wanted to say about him... i didn't write as much about him in this answer but we really don't get much of him in the books, SMH. I don't like to go too off-piste from canon but I want to take what's there and honor the humanity hidden within it. (I have to guess that we'll have more g1deon in alecto, right? it just wouldn't be fair otherwise, right? ... RIGHT?? T_T)

pyrrha

and you didn't say especially pyrrha but i think that my secret internal moodboard for pyrrha is important as well!!! in my 5 planned pyrrwakeon fics (3 currently pubbed), none are from pyrrha's POV, and that has a twofold purpose. 1) there are already a ton of fics from her POV, as you say, as well as a whole canon novel focused on her, and i want to explore the two under-served points of the love triangle, and 2) i actually really like her as an enigma.

e.g., something people neglect with her a bit i think is her suicidality. how else can you characterize someone who falls in love with landmines? the woman swallowed bleach for god's sake. jury's still out on whether she killed herself or g1deon killed her for their ascension (i have it as her killing herself in my g1dfic but i've been thinking and now i'm not so sure i want to go for that) but if there's one thing we know about pyrrha it's that she fucking loves doing shit that's very dangerous and a horrible idea, partially to feel alive, partially to feel dead and thereby free.

so therefore my theory on her caring for nona, and less so cam & pal, is an uncharacteristic break toward life and hope in the long long slide through samsara as a means of escaping soul death that has been her 9000-year undead existence thus far. but i find the depiction of this facet of her character to be far more compelling from the outside, such as, from wake's POV, or g1deon's.

ALSO SHE WOULD NOT WANT TO BE A MOM OR DAD AND DOES NOT GIVE A FUCK ABOUT BEING A PARENT SORREEEEEEEEE (her "why did you bring along the baby" is about her pity for a helpless creature suffering yet more needless death, not that it's specifically hers and wake's, and her care for gideon nav & nona are on a soft human level despite herself because no one else will and not demonstrative of a secret desire for parenthood STOP MAKING WOMEN CHARACTERS WANT TO BE PARENTS *panting & swallowing bile*)

anywayyyy very very very soon forthcoming to explore this final third of the triangle is my ultimate wake/pyrrha lying liars genderfic in which she, through the proxy of getting fucked by wake, wrestles with her grief over losing both her own body and losing g1deon as her lover/partner/friend. and you can bet wake just looooves being used as a proxy for someone else to work through their issues ^_^

...

in conclusion, wake/pyrrha/g1deon is a land of contrasts. let wake have political values, let g1deon be a fucking human being, and stop making pyrrha always top. thank u.

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Author Spotlight: Aida Salazar

What are your literary influences?

My literary influences come from disparate sources. I studied a wide variety of theory in college and graduate school — everyone from Roland Barthes to Judith Butler to Gloria Anzaldua and Cherrie Moraga to Bell Hooks to Mikail Baktin to Subcomandante Marcos. I also read poetry voraciously including everyone from Waslowa Simbroska to Lorna Dee Cervantes, Audre Lorde, Rumi, Wole Soyinka, Juan Felipe Herrera. I was marveled by the fiction of Milan Kundera, Arundati Roy, Elena Poniatowska and all of the Latin American magical realists – Asturias, Garcia Marquez, Allende, Esquivel. But also, American writers such as Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Helena Maria Viramontes, Ana Castillo, Julia Alvarez and Christina Garcia. I was drawn to authors from the margin almost exclusively. In a sense, I created my own canon in this way.

It wasn’t until I became a mother that I truly started reading children’s literature. My children and I found an oasis in our weekly visits to the library. In Oakland, we are fortunate to have a comprehensive Spanish language collection at the Cesar Chavez Library and we often checked out the forty-book limit! However, many of the books were authored by non Latinx writers and were translated into Spanish. While these books served to reinforce the Spanish language in our family, I saw the huge lack of writings from Latinx creators. I wanted to be a part of filling that gap. I wanted for my children to not only see their language reflected in books but their cultures and their sensibilities. That is why I always praise the work of those Latinx authors who forged the way so that new Latinx kidlit authors could have a seat at the table. We stand on the shoulders of giants and I would be remiss if I didn’t mention their work. Authors such as Pura Belpre, Gary Soto, Sandra Cisneros, Alma Flor Ada, Pat Mora, Carmen Lomas Garza, Francisco X. Alarcon, Juan Felipe Herrera, and Victor Martinez really set the stage for us to be able to tell our stories to young audiences too.

What was the first book you read where you identified with one of the characters?

As a young child, I didn’t understand that I was missing in the narratives of books that I read. I loved Judy Blume. I loved Shell Silverstein. I loved Encyclopedia Brown and Choose Your Own Adventure books. I connected to those books by default, in a similar way that I connected to mass media that also didn’t include me in their blond-haired blue-eyed middle-class, English-only narratives. There was no other option. It wasn’t until I was eighteen and in college that I enrolled in a Latino (we called it that back then) literature course that I saw myself reflected in a book. I remember reading the short story “My Lucy Friend That Smells Like Corn,” in Sandra Cisneros’ Woman Hollering Creek and feeling a moment that I can only describe as grace. I realized that I had been missing in almost everything I had read up until that point. My experiences were alive and validated in that story. It was exhilarating.

Did that experience lead you to want to write books for readers with diverse backgrounds?

I was so inspired by reading all of the books in that Latino literature class. It was an awakening not only to the world of Latinx literature but to the possibility that I too could be a writer. I had been writing poetry and stories since I was a young teenager but those writings remained in my notebooks and journals. After reading their work, I began to take myself seriously and began to understand the writing that lived in my heart could be something I could aspire to do as a living someday. However, my awakening is one that should have not taken eighteen years and I want to be part of making sure that doesn’t happen to other children.

Your characters in The Moon Within have interesting intersections. Could you speak to why this was important to build into your book?

I did this intentionally. My children are multi-racial and bi-cultural like two of the characters, Celi and Iván. It is not uncommon to see many different mixed children in the San Francisco Bay Area where we live. I find it beautiful how they navigate multiple cultures – sometimes with a sense of wonder and pride and sometimes with neglect or shame and every feeling in between. It’s complicated and certainly isn’t always seamless given so much discussion over racial and cultural purity that is happening today. Through those characters, I wanted to show this negotiation, how they deal with these fusions. I wanted to show readers what it might look like for someone to celebrate and embrace all of who they are. Similarly, I wanted to show with the gender fluid character, Marco, the intersectionality of his identity as a gender fluid Mexican that happens to be in love with playing bomba (a Afro-Puertorican form of music). It was important to show readers that we could be queer and Mexican, Black Puerto Rican Mexican, and Black and Mexican. The range of identities are part of the beauty of who they are, and serve to strengthen and not weaken them.

Music infuses the whole world of The Moon Within …can you speak a little on that, a little on what role music plays in your own life?

Ironically, I am not a musician though I have a good ear and I love to dance. I am married to a musician and there has not been one day in the eighteen years since we’ve been together when we did not engage in some way with music – listening, playing, singing, dancing or just being in a house filled with instruments and an extraordinary recorded music collection. Our children were naturally born into this environment and took to music right away. I realized that this was a unique experience and that it could be a wonderful world to explore in this book. I wanted to normalize music and the arts as a way of life but also, wanted to inspire readers to seek out the arts as a way to find agency as the children in the book did through traditional music and dance. These are superpowers that unfortunately, with the cutting of the arts for decades now, we don’t have access to as much.

I made a playlist on Spotify that includes all of the styles of music that inspired The Moon Within – bomba, indigenous Mexican music, Caribbean music, and lots of moon related songs in Spanish and in English. It can be found here: https://spoti.fi/2FSnZgM . I hope that you enjoy it!

This Author Spotlight appeared in the April 2019 issue of the CBC Diversity Newsletter. To sign up for our monthly Diversity newsletter click here.

Aida Salazar is a writer, arts advocate, and home-schooling mother who grew up in South East LA. She received an MFA in Writing from the California Institute of the Arts, and her writings have appeared in publications such as the Huffington Post, Women and Performance: Journal of Feminist Theory, and Huizache Magazine. Her short story, By the Light of the Moon, was adapted into a ballet by the Sonoma Conservatory of Dance and is the first Xicana-themed ballet in history. Aida lives with her family of artists in a teal house in Oakland, CA.

#Aida Salazar#the moon within#Scholastic#kitlit#CBC Diversity#Diverse Children's Books#author illustrator spotlight

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cecilia Vicuña | Language Is Migrant

Language is migrant. Words move from language to language, from culture to culture, from mouth to mouth. Our bodies are migrants; cells and bacteria are migrants too. Even galaxies migrate.

What is then this talk against migrants? It can only be talk against ourselves, against life itself.

Twenty years ago, I opened up the word “migrant,” seeing in it a dangerous mix of Latin and Germanic roots. I imagined “migrant” was probably composed of mei, Latin for “to change or move,” and gra, “heart” from the Germanic kerd. Thus, “migrant” became “changed heart,”

a heart in pain, changing the heart of the earth.

The word “immigrant” says, “grant me life.”

“Grant” means “to allow, to have,” and is related to an ancient Proto-Indo-European root: dhe, the mother of “deed” and “law.” So too, sacerdos, performer of sacred rites.

What is the rite performed by millions of people displaced and seeking safe haven around the world? Letting us see our own indifference, our complicity in the ongoing wars?

Is their pain powerful enough to allow us to change our hearts? To see our part in it?

I “wounder,” said Margarita, my immigrant friend, mixing up wondering and wounding, a perfect embodiment of our true condition!

Vicente Huidobro said, “Open your mouth to receive the host of the wounded word.”

The wound is an eye. Can we look into its eyes?

my specialty is not feeling, just looking, so I say: (the word is a hard look.) —Rosario Castellanos

I don’t see with my eyes: words are my eyes. —Octavio Paz

In l980, I was in exile in Bogotá, where I was working on my “Palabrarmas” project, a way of opening words to see what they have to say. My early life as a poet was guided by a line from Novalis: “Poetry is the original religion of mankind.” Living in the violent city of Bogotá, I wanted to see if anybody shared this view, so I set out with a camera and a team of volunteers to interview people in the street. I asked everybody I met, “What is Poetry to you?” and I got great answers from beggars, prostitutes, and policemen alike. But the best was, “Que prosiga,” “That it may go on”—how can I translate the subjunctive, the most beautiful tiempo verbal (time inside the verb) of the Spanish language? “Subjunctive” means “next to” but under the power of the unknown. It is a future potential subjected to unforeseen conditions, and that matches exactly the quantum definition of emergent properties.

If you google the subjunctive you will find it described as a “mood,” as if a verbal tense could feel: “The subjunctive mood is the verb form used to express a wish, a suggestion, a command, or a condition that is contrary to fact.” Or “the ‘present’ subjunctive is the bare form of a verb (that is, a verb with no ending).”

I loved that! A never-ending image of a naked verb! The man who passed by as a shadow in my film saying “Que prosiga” was on camera only for a second, yet he expressed in two words the utter precision of Indigenous oral culture.

People watching the film today can’t believe it was not scripted, because in thirty-six years we seem to have forgotten the art of complex conversation. In the film people in the street improvise responses on the spot, displaying an awareness of language that seems to be missing today. I wounder, how did it change? And my heart says it must be fear, the ocean of lies we live in, under a continuous stream of doublespeak by the violent powers that rule us. Living under dictatorship, the first thing that disappears is playful speech, the fun and freedom of saying what you really think. Complex public conversation goes extinct, and along with it, the many species we are causing to disappear as we speak.

The word “species” comes from the Latin speciēs, “a seeing.” Maybe we are losing species and languages, our joy, because we don’t wish to see what we are doing.

Not seeing the seeing in words, we numb our senses.

I hear a “low continuous humming sound” of “unmanned aerial vehicles,” the drones we send out into the world carrying our killing thoughts.

Drones are the ultimate expression of our disconnect with words, our ability to speak without feeling the effect or consequences of our words.

“Words are acts,” said Paz.

Our words are becoming drones, flying robots. Are we becoming desensitized by not feeling them as acts? I am thinking not just of the victims but also of the perpetrators, the drone operators. Tonje Hessen Schei, director of the film Drone, speaks of how children are being trained to kill by video games: “War is made to look fun, killing is made to look cool. ... I think this ‘militainment’ has a huge cost,” not just for the young soldiers who operate them but for society as a whole. Her trailer opens with these words by a former aide to Colin Powell in the Bush/Cheney administration:

OUR POTENTIAL COLLECTIVE FUTURE. WATCH IT AND WEEP FOR US. OR WATCH IT AND DETERMINE TO CHANGE THAT FUTURE —Lawrence Wilkerson, Colonel U.S. Army (retired)

In Astro Noise, the exhibition by Laura Poitras at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the language of surveillance migrates into poetry and art. We lie in a collective bed watching the night sky crisscrossed by drones. The search for matching patterns, the algorithms used to liquidate humanity with drones, is turned around to reveal the workings of the system. And, we are being surveyed as we survey the show! A new kind of visual poetry connecting our bodies to the real fight for the soul of this Earth emerges, and we come out woundering: Are we going to dehumanize ourselves to the point where Earth itself will dream our end?

The fight is on everywhere, and this may be the only beauty of our times. The Quechua speakers of Peru say, “beauty is the struggle.”

Maybe darkness will become the source of light. (Life regenerates in the dark.)

I see the poet/translator as the person who goes into the dark, seeking the “other” in him/herself, what we don’t wish to see, as if this act could reveal what the world keeps hidden.

Eduardo Kohn, in his book How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human notes the creation of a new verb by the Quichua speakers of Ecuador: riparana means “darse cuenta,” “to realize or to be aware.” The verb is a Quichuan transfiguration of the Spanish reparar, “to observe, sense, and repair.” As if awareness itself, the simple act of observing, had the power to heal.

I see the invention of such verbs as true poetry, as a possible path or a way out of the destruction we are causing.

When I am asked about the role of the poet in our times, I only question: Are we a “listening post,” composing an impossible “survival guide,” as Paul Chan has said? Or are we going silent in the face of our own destruction?

Subcomandante Marcos, the Zapatista guerrilla, transcribes the words of El Viejo Antonio, an Indian sage: “The gods went looking for silence to reorient themselves, but found it nowhere.” That nowhere is our place now, that’s why we need to translate language into itself so that IT sees our awareness.

Language is the translator. Could it translate us to a place within where we cease to tolerate injustice and the destruction of life?

Life is language. “When we speak, life speaks,” says the Kaushitaki Upanishad.

Awareness creates itself looking at itself.

It is transient and eternal at the same time.

Todo migra. Let’s migrate to the “wounderment” of our lives, to poetry itself.

Images by Cecilia Vicuña (Karl Marx, 1972 & Lenin, 1972)

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

On #QAnon: The full text of our Buzzfeed Interview

Ryan Broderick of Buzzfeed just published an article on this #QAnon conspiracy bullshit titled It's Looking Extremely Likely That QAnon Is A Leftist Prank On Trump Supporters. The piece features quotes from an interview we gave via email. Here’s the full email exchange.

--

Can you tell me a bit about when and how your book Q was written?

We started writing Q in the last months of 1995, when we were part of the Luther Blissett Project, a network of activists, artists and cultural agitators who all shared the name «Luther Blissett». Luther Blissett was and still is a British public figure, a former footballer, a philanthropist. The LBP spread many mythical tales about why we chose to borrow his name, but the truth is that nobody knows.

Initially, Blissett the footballer was bemused, but then he decided to play along with us and even publicly endorsed the project. Last year, during an interview on the Italian TV, he stated that having his name adopted for the LBP was «a honour». The purpose of signing all our statements, political actions and works of art with the same moniker was to build the reputation of one open character, a sort of collective "bandit", like Ned Ludd, or Captain Swing. It was live action role playing. The LBP was huge: hundreds of people in Italy alone, dozens more in other countries. In the UK, one of the theorists and propagandists of the LBP was the novelist Stewart Home.

The LBP lasted from 1994 to 1999. The best English-language account of those five years is in Marco Deseriis' book Improper Names: Collective Pseudonyms from the Luddites to Anonymous. One of our main activities consisted of playing extremely elaborate pranks on the mainstream media. Some of them were big stunts which made us quite famous in Italy. The most complex one was played by dozens of people in the backwoods around Viterbo, a town near Rome. It lasted a year, involving Satanism, black masses, Christian anti-satanist vigilantes and so on. It was all made up: there were neither Satanists nor vigilantes, only fake pictures, strategically spread rumours and crazy communiqués, but the local and national media bought everything with no fact-checking at all, politicians jumped on the bandwagon of mass paranoia, we even managed to get footage of a (rather clumsy) satanic ritual broadcast in the national TV news, then we claimed responsibility for the whole thing and produced a huge mass of evidence. The Luther Blissett Project was also responsible for a huge grassroots counter-inquiry on cases of false child abuse allegations. We deconstructed the paedophilia scare that swiped Europe in the second half of the 1990s, and wrote a book about it. A magistrate whom we targeted in the book filed a lawsuit, as a consequence the book was impounded and disappeared from bookshops, but not from the web.

This is the context in which we wrote Q. We finished it in June 1998. It came out in March 1999 and was our final contribution to the LBP.

I've been reading up about it, and it's largely believed that it's underneath the book's narrative it works as handbook for European leftists? Is that a fair assessment? I've read that many believe the book's plot is an allegory for 70s and 80s European activists?

Although it keeps triggering many possible allegorical interpretations, we meant it as a disguised, oblique autobiography of the LBP. We often described it as Blissett's «playbook», an «operations manual» for cultural disruption.

The four authors I'm speaking to now are Roberto Bui, Giovanni Cattabriga, Federico Guglielmi and Luca Di Meo correct? The four authors of Q?

You are speaking with three of the four authors of Q, and you're speaking with a band of writers called Wu Ming, which means «Anonymous» in Chinese. In December 1999 the Luther Blissett Project committed a symbolic suicide - we called it The Seppuku - and in January 2000 we launched another project, the Wu Ming Foundation, centred around our writing and our blog, Giap. The WMF is now an even bigger network than the LBP was, and includes many collectives, projects and laboratories. Luca aka Wu Ming 3 is not a member of the band anymore, although he still collaborates with us on specific side projects. Each member of the band has a nom de plume composed of the band's name and a numeral, following the alphabetical order of our surnames, thus you're speaking to Roberto Bui aka Wu Ming 1, Giovanni Cattabriga aka Wu Ming 2 and Federico Guglielmi aka Wu Ming 4.

Can you tell me a bit about your background before the Luther Blissett project?

Before the LBP we were part of a national scene that was – and still is – called simply «il movimento», a galaxy of occupied social centres, squats, independent radio stations, small record labels, alternative bookshops, student collectives, radical trade unions, etc. In the Italian radical tradition, at least after the Sixties, there was never any clearcut separation between the counterculture and more political milieux. Most of us came from left-wing family backgrounds, had roots in the working class. Punk rock opened our minds during our teenage years, then in the late 1980s and early 1990s Cyberpunk opened them even more, and inspired new practices.

When did you start noticing similarities between Q and QAnon? I know you've tweeted a bit about this, but I'd love to get as many details as I can. I feel like the details around QAnon are so sketchy that it's important to lock in as much as I can here.

We read a lot about the US alt-right, books such as Elizabeth Sandifer's Neoreaction a Basilisk or Angela Nagle's – flawed but still useful – Kill All Normies, and yet we didn't see the QAnon thing coming. We didn't know it was growing on 4chan and some specific subReddits. About six weeks ago, on June 12th, our old pal Florian Cramer – a fellow veteran of the LBP who now teaches at the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam – sent us a short email. Here's the text:

«It seems as if somebody took Luther Blissett's playbook and turned it into an Alt-Right conspiracy lore. Maybe Wu Ming should write a new article: "How Luther Blissett brought down Roseanne Barr"!»,

After those sentences there was a link to a piece by Justin Caffier on Vice. We read it, and briefly commented on Twitter, then in the following weeks more and more people got in touch with us, many of them Europeans living in the US. They all wanted to draw our attention on the QAnon phenomenon. To anyone who had read our novel, the similarities were obvious, to the extent that all these people were puzzled seeing that no US pundit or scholar was citing the book.

Have there been key moments for you that made you feel like QAnon is an homage to Q? What has lined up the best?

Coincidences are hard to ignore: dispatches signed Q allegedly coming from some dark meanders of top state power, exactly like in our book. This Q is frequently described as a Blissett-like collective character, «an entity of about ten people that have high security clearance», and at the same time – like we did for the LBP – weird "origin myths" are put into circulation, like the one about John Kennedy Jr. faking his own death in 1999 – the year Q was first published, by the way! – and becoming Q. QAnon's psy-op reminds very much of our old «playbook», and the metaconspiracy seems to draw from the LBP's set of references, as it involves the Church, satanic rituals, paedophilia...

We can't say for sure that it's an homage, but one thing is almost certain: our book has something to do with it. It may have started as some sort of, er, "fan fiction" inspired by our novel, and then quickly became something else.

There will be a lot of skepticism I think that an American political movement like QAnon could have been influenced by an Italian novel, how do you think it may have happened?

It's an Italian novel in the sense that it was originally written in Italian by Italian authors, but in the past (nearly) 20 years it has become a global novel. It was translated into fifteen languages – including Korean, Japanese, Russian, Turkish – and published in about thirty countries. It was successful all across Europe and in the English speaking world with the exception of the US, where it got bad reviews, sold poorly and circulated almost exclusively in activist circles.

Q was published in Italian a few months before the so-called "Battle of Seattle", and published in several other languages in the 2000-2001 period. It became a sort of night-table book for that generation of activists, the one that would be savagely beaten up by an army of cops during the G8 summit in Genoa, July 2001. In 2008 we wrote a short essay, almost a memoir, on our participation to those struggles and Q's influence in those years, titled Spectres of Müntzer at Sunrise. A copy of Q's Spanish edition even ended up in the hands of subcomandante Marcos. It isn't at all unrealistic to imagine that it may have inspired the people who started QAnon.

Have you seen anything in the QAnon posts that leads you to suspect any activist group in particular is behind it?

No, we haven't.

You think QAnon is a prank? Without some kind of reveal it's obviously hard to see it as that. If you think it was revealed that QAnon was actually some kind of anarchist prank, would it even matter? Would its believers abandon it or would they just see it as a smear campaign?

Let us take for granted, for a while, that QAnon started as a prank in order to trigger right-wing weirdos and have a laugh at them. There's no doubt it has long become something very different. At a certain level it still sounds like a prank, but who's pulling it on whom? Was the QAnon narrative hijacked and reappropriated by right-wing "counter-pranksters"? Counter-pranksters who operated with the usual alt-right "post-ironic" cynicism, and made the narrative more and more absurd in order to astonish media pundits while spreading reactionary content in a captivating way?

Again: are the original pranksters still involved? Is there some detectable conflict of narratives within the QAnon universe? Why are some alt-right types taking the distance from the whole thing and showing contempt for what they describe as «a larp for boomers»?

A larp it is, for sure. To be more precise, it's a fascist Alternate Reality Game. Plausibly the most active players – ie the main influencers – don't believe in all the conspiracies and metaconspiracies, but many people are so gullible that they'll gulp down any piece of crap – or lump of menstrual blood, for that matter. Moreover, there's danger of gun violence related to the larp, the precedent of Pizzagate is eloquent enough. What if QAnon inspires a wave of hate crimes?

Therefore, to us the important question is: triggering nazis like that, what is it good for? That camp is divided between those who would believe anything and those who would be "ironic" on anything and exploit anything in order to advance their reactionary, racist agenda. Can you really troll or ridicule people like those?

It's hard to foresee what would happen if QAnon were exposed as an anarchist/leftist prank on the right. If its perpetrators claimed responsibility for it and showed some evidence (for example, unmistakeable references to our book and the LBP), would the explanation itself become yet another part of the narrative, or would it generate a new narrative encompassing and defusing the previous one? In plain words: which narrative would prevail? «QAnon sucking anything into its vortex» or «Luther Blissett's ultimate prank»?

In any case, we'd never have started anything like that ourselves. Way too dangerous.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

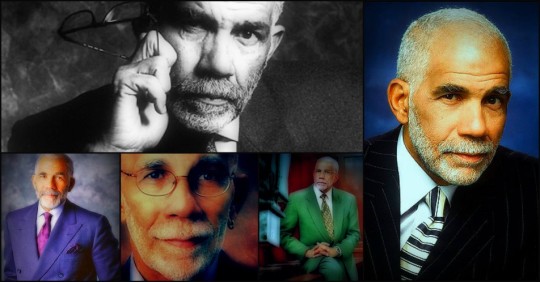

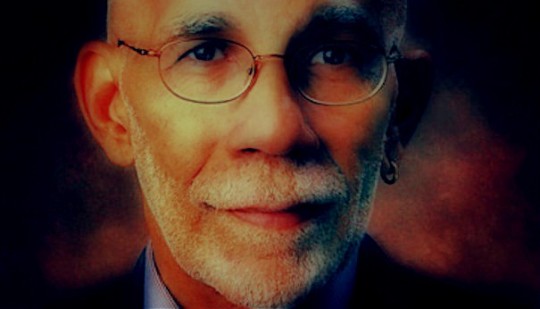

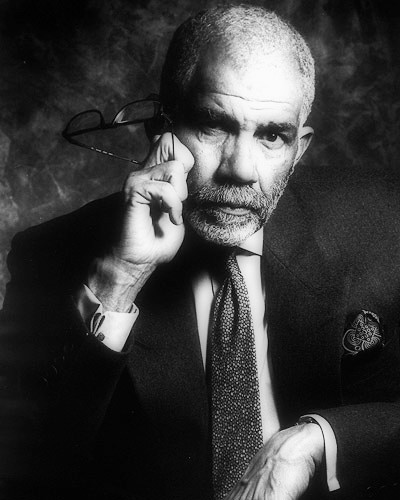

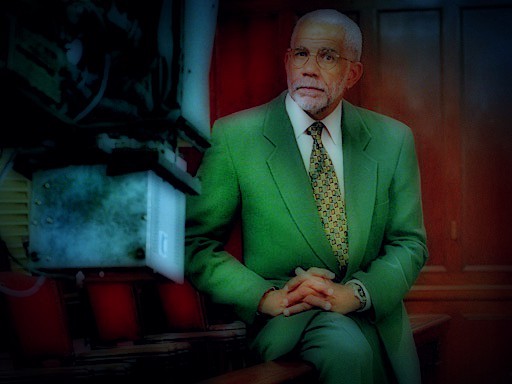

Ed Bradley

Edward Rudolph Bradley, Jr. (June 22, 1941 – November 9,2006) was an American journalist, best known for 26 years of award-winning work on the CBS News television program 60 Minutes. During his earlier career he also covered the fall of Saigon, was the first black television correspondent to cover the White House, and anchored his own news broadcast, CBS Sunday Night News with Ed Bradley. He received several awards for his work including the Peabody, the National Association of Black Journalists Lifetime Achievement Award, and 19 Emmy Awards.

Biography

Early life

Bradley was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His parents divorced when he was 2, after which he was raised by his mother, Gladys, who worked two jobs to make ends meet. Bradley, who was referred to with the childhood name of "Butch Bradley," was able to see his father, who was in the vending machine business and owned a restaurant in Detroit, in the summertime. When he was 9, his mother enrolled him in the Holy Providence School, an all-black Catholic boarding school run by the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament at Cornwells Heights, Pennsylvania. He attended Mount Saint Charles Academy, in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. He graduated in 1959 from Saint Thomas More Catholic Boys High School in West Philadelphia and then another historically black school, Cheyney State College (now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania) in Cheyney, Pennsylvania, graduating in 1964 with a degree in education. His first job was teaching sixth grade at the William B. Mann Elementary School in Philadelphia's Wynnefield community. While he was teaching, he moonlighted at the old WDAS studios on Edgley Drive in Philadelphia's Fairmount Park, working for free and, later, for minimum wage. He programmed music, read news, and covered basketball games and other sports.

Career

Bradley's introduction to news reporting came at WDAS-FM during the riots in Philadelphia in the 1960s. In 1967 he landed a full-time job at the CBS-owned New York radio station WCBS. In 1971, he moved to Paris, France. Initially living off his savings, he eventually ran out of money and began working as a stringer for CBS News, covering the Paris Peace Talks. In 1972 he volunteered to be transferred to Saigon to cover the Vietnam War, as well as spending time in Phnom Penh covering the war in Cambodia. It was there that he was injured by a mortar round, receiving shrapnel wounds to his back and arm.

In 1974 he moved to Washington, D.C., and was promoted to covering the Carter campaign in 1976. He then became CBS News White House correspondent (the first black White House television correspondent) until 1978, when he was invited to move to CBS Reports, where he served as principal correspondent until 1981. In that year, Walter Cronkite departed as anchor of the CBS Evening News and was replaced by the 60 Minutes correspondent Dan Rather, leaving an opening on the program that was filled by Bradley.

Over the course of Bradley's 26 years on 60 Minutes, he did over 500 stories, covering nearly every possible type of news, from "heavy" segments on war, politics, poverty, and corruption, to lighter biographical pieces, or stories on sports, music, and cuisine. Among others, he interviewed Howard Stern, Laurence Olivier, Subcomandante Marcos, Timothy McVeigh, Michael Jackson, Mick Jagger, Bill Bradley, the 92-year-old George Burns, and Michael Jordan, as well as conducting the first television interview of Bob Dylan in 20 years. Some of his quirkier moments included playing blackjack with the blind Ray Charles, interviewing a Soviet general in a Russian sauna, and having a practical joke played on him by Muhammad Ali. Bradley's favorite segment on 60 Minutes was when, as a 40-year-old correspondent, he interviewed 64-year-old singer Lena Horne. He said, "If I arrived at the pearly gates and Saint Peter said, 'What have you done to deserve entry?' I'd just say, 'Did you see my Lena Horne story?'"

On the show, Bradley was known for his sense of style. He was the first male correspondent to regularly wear an earring on the air. He had his left ear pierced in 1986 and says he was inspired to do it after receiving encouragement from Liza Minnelli following an interview with the actress. He is also thus far the only male 60 Minutes anchor to do so, though male correspondents from other network programs, including Jim Vance, Jay Schadler, and Harold Dow, later wore earrings on camera.

Personal life

Bradley never had children, but was married to Haitian-born artist Patricia Blanchet, whom he had met at a museum where she was working as a docent. Despite the age difference (she was 24 years younger than he), Bradley pursued her, and they dated for 10 years before marrying in a private ceremony in Woody Creek, Colorado, where they had a home. Bradley also maintained two homes in New York: one in East Hampton, and the other in New York City.

In the early 1970s, Bradley had a brief romantic relationship with Jessica Savitch, who at that time was an administrative assistant for CBS News and later became an NBC News anchor. After the relationship ended, Bradley and Savitch continued to have a non-romantic social and professional relationship until her death in 1983.

Bradley was known for loving all kinds of music, but he was especially a jazz music enthusiast. He hosted the Peabody Award–winning Jazz at Lincoln Center on National Public Radio for over a decade until just before his death. A big fan of the Neville Brothers, Bradley performed on stage with the bunch, and was known as "the fifth Neville brother". Bradley was also friends with Jimmy Buffett, and would often perform onstage with him, under the name "Teddy". Bradley had limited musical ability and did not have an extensive repertoire, but would usually draw smiles by singing the 1951 classic by Billy Ward and the Dominoes, "Sixty Minute Man".

Bradley died on November 9, 2006, at Mount Sinai Hospital, in Manhattan of complications from lymphocytic leukemia. He was 65 years old.

Legacy

Bradley was honored in April 2007 with a traditional jazz funeral procession at the New Orleans Jazzfest, of which he was a large supporter. The parade, which took place on the first day of the six-day festival, circled the fairgrounds and included two brass bands.

Columnist Clarence Page wrote:

Bradley had been a season ticket holder to the New York Knicks for over 20 years. On November 13, 2006, they honored him with a moment of silence. On the 60 Minutes program after Bradley's death, his longtime friend Wynton Marsalis closed the show with a solo trumpet performance, playing some of the music Bradley loved best.

In 1994, Bradley created the Ed Bradley Scholarship, which has since been offered annually by the Radio Television Digital News Association to outstanding aspiring journalists in recognition of Bradley's legacy and contributions to journalism.

Awards

Emmy Award 19 times

Peabody Award for his African AIDS report, "Death By Denial"

Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award

1979: George Polk Award for Foreign Television

2000: Paul White Award from the Radio and Television News Directors Association

2005: Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Association of Black Journalists for being one of the first African Americans to break into network television news

2007: Bradley posthumously won the 66th annual George Foster Peabody award for his examination of the Duke University rape case

2007: Bradley posthumously inducted into the Broadcast Pioneers of Philadelphia [2] Hall of Fame

Wikipedia

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Relationships: Part II – I’ve Heard You Shouldn’t Make Homes Out of People

Thinking more about the problems and questions I posed in the first part, I felt it necessary to make some distinctions. Although I condemn the use of pain to hurt others in person-to-person interactions, I do not believe the same can apply at other “levels” or “layers” of social and historical existence. When we speak of structural violence, we often refer to social institutions that perpetuate discrimination, exclusion and marginalization through various processes. These “processes” are composed of social practices and beliefs that, through their simultaneous operations, create the kinds of worlds in-and-through which we, as social subjects, come to see ourselves and others. The term “structural” can be interpreted as “networks” that coordinate themselves according to shifting condensations of economic, social, cultural and human capital – a “push” here, for example, might necessitate a “pull” there. In this way, no singular person could be said to serve as a point of absolute origin for the forms of violence that people experience in their day-to-day lives. Instead, power comes to embody the shape of conglomerations, of clusters, of interconnected nodes in network societies. Based on this particular understanding of power, authority and violence, the finger of blame cannot be pointed at a singular subject. Or, in other words, the problem does not necessarily lie with, for instance, “white people” themselves but with whiteness as a network of social institutions, ideologies and practices that maintains people who identify as (or even look) white in a structural position of relative privilege (whiteness also affords power to people who align themselves with these same institutions, ideologies and practices – of which my writing as an academic trained in elite institutions is complicit with).

So, what do we do with statistics such as these:

“In Australia, indigenous youth are 28 times more likely than non-indigenous youth to be detained (ABC News, 2011), while in the US black and Hispanic youth face harsher treatment at each stage in the criminal justice system (The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, 2000). While black youth represent 5 per cent and Hispanic youth 19 per cent of the juvenile population in the US, respectively they account for 45 per cent and 25 per cent of the incarcerated youth population (Saavedra, 2010).” (Andy Furlong, Youth Studies: An introduction, 2013, p. 191)

Clearly, there are groups of people that are structurally pre-dispositioned to be kept in certain social segments (e.g., physically in jail cells [issues of space/place]; migrants kept waiting for the right to have rights [issues of time/temporality]). There are specific histories of economic dispossession, social displacement and cultural genocide that help explain why brown and black communities (this isn’t exclusive to issues of skin color, though colorism can and does affect how people experience their lives) are over-represented in prison populations. To move from an individual level (the person-to-person engagements I addressed in “Part I”), to a structural level, means having to reckon with suffering and exploitation in ways that consider the larger contexts that inform how people think and act. At this level of social experience, attempts to count and leverage “coins” of pain in a group’s “historical jar” cannot be simply reduced to selfish acts of vengeance or egotistical demands for attention and care. At a structural level, socially afflicted communities are often cornered into political positions where there is little wiggle room to act “ethically” according to existing frameworks of morality and legality (morals and laws that often contribute structurally to more violence and marginalization, than to support or assistance).

I’ve heard that you shouldn’t make homes out of people.

My discussion of relationships in Part I begins to carve out the reasons why this statement might be true. “Hurt people, hurt people,” as the saying goes. The violence people embody often gets displaced onto others because they lack the capacity to hold the unbearable weight of histories (simultaneously distant and personal) that both connect and separate them. I think this is why we often “snap” at those whom we consider to be the closest and most intimate—we expect them to serve as our personal punching bags (after all, they love us, right?). This is also why people, amidst their busy schedules and right to live their lives, can sometimes only offer a share on Instagram or a status update on Facebook when confronted with global atrocities—including those sponsored by their “own” governments and countries (which also means, economically-speaking, their taxable incomes). The line that separates virtuous resistance from complicity to oppression is becoming increasingly thinner and thinner in social worlds where the clothes we wear and the foods we eat come to us from disparate locations, near and far, and often by exploitative means.

Is anyone innocent?

If one shouldn’t make a home out of people, perhaps it is in part because our insides mirror the wars taking place outside. There are terrible, invisible battles inside people’s hearts and minds that twinkle like guns fired all over the world—past and present. I believe change at a structural, systemic level requires social retribution for historical debts that persistently and perniciously feed current forms of inequity across differences of class, race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, ability and nationality. At an interpersonal level, however, I fear these same demands fuel further alienation, splinter coalitions and build a general distrust of people who are different from “us.” Is there a way to mediate the two positions without falling into extreme forms of nationalism and territoriality, or empty “inclusions” that simply reproduce and reinforce social hierarchies? I return to an often-cited quote by Subcomandante Marcos: “El mundo que queremos es uno donde quepan muchos mundos;” “The world we desire is one where many worlds can fit.” I highlight this demand not to romanticize indigenous Zapatista politics, nor to offer a solution to planetary disarray, but to suggest that a haunting question/reality remains with many communities today: Are people capable of letting “difference” live with integrity and on its own terms? Or are certain organizations of political and communal life automatically hostile to one another, preventing any “sincere” or “authentic” compromise from emerging? It is important to note that difference has many forms: ecological environments; non-human animals and plant life; cultural and political systems; spiritual and religious beliefs and practices; gendered and sexual diversities; and the list goes on.

My point, I suppose, is that even if we consider the brief, yet deeply complex scale that is a human life, an individual person’s biography, we will eventually reach a point where violence feels inevitable, even natural: to live in societies so entrenched with bloody histories, as is the case with the United States, can anyone truly say they exist free of charge? If we do, in fact, live in social networks, does this kind of (globalizing) cultural existence not implicate practically everyone? And if it does, are people touched by violence in the same way? I think the answer would be “no,” especially if modern histories of genocide, enslavement and dispossession are to be taken seriously at all. To equalize oppression, as when one claims that “All Lives Matter,” is to commit an error of magnitude and proportion, for people of color, women, and queer and trans* folks have served historically as collateral for the “civilized,” modern lifestyles that citizens, noncitizens and second-class citizens get to live in the here and now—whether they enjoy it or not, find it meaningful or not, is beside the point. It seems to me that across the tenuous spectrums of oppressor/oppressed, there runs a loud silence, a dazzling absence that grounds the very existences of people as social individuals: systematic death as a contemporary common origin – but not one from which everyone benefits equally.

Which brings me to another question: can trauma purify?

What does an inheritance of collective pain at an individual level do? Consider the following scenario: a third-generation indigenous girl accompanied by her Mexican-American father is called “Pocahontas” by an elderly white woman at a Whole Foods in Southern California. The woman looks down at the girl and repeats her observation with a warm smile – “You look like her [Pocahontas]” –, only to be met with an uncertainty that gleams from the girl’s eyes as to the significance of the claim, of the way in which she is being interpellated by the woman as looking “native” (I won’t go into the problematics of basing native and indigenous identity on Disney representations). So, what happened here? Are these innocent, everyday exchanges? Or has certain damage been done (again)? And, if so, who’s at fault? How ought one to respond? One way to reply to these questions—arguably the most obvious—would be to assume a binary approach: the woman is the oppressor and the girl is the oppressed; each is a symbolic condensation of histories of colonial violence. But we can also just as easily say that the woman is not a willful oppressor (her comment, from her perspective, was not meant to be offending). Likewise, the girl does not willfully assume the position of the victim or the oppressed (in fact, the woman’s comment might not even make an impression amidst other priorities and preoccupations). Rather, both are given to larger and deeper structures that, before they even happen to bump into each other at an aisle in a grocery store, already situate and render meaningful interactions in ways that seem to necessitate an implicit, and thus explicit, hierarchy.

This is the distinction that I highlight between the pain people wage on one another through interpersonal contact, and the suffering that people as communities depend on, and must therefore politically mobilize, in order to make claims for social justice. The two levels co-exist and constantly inform each other—this makes the problem of historical trauma particularly tricky to frame. Through this distinction, violence demonstrates the paradoxical and contradictory ways in which an emphasis on trauma might prove necessary on one level of social experience (the systematic nature of social institutions), while possibly detrimental on another (everyday encounters with people).

At the end, however, we are still left with questions of justice and ethics. How might the woman be made accountable for her supposed “innocent” remarks based on, and supported by, the structural privileges afforded to whiteness in the U.S.? Relatedly, how might the incident be made conscious to the girl in a way that does not propagate a victim mentality or an inferiority complex, but instead affirms the dignity of her identities and her right to exist as a person? I do not have answers to these questions. They might be questions for policy and lawmakers; for researchers and scholars; for grassroots activists and organizations. The issues I raise do not have singular, once-and-for-all remedies (or at least not any that I can personally identify) – they are symptoms of the immensity and the difficulty of existing in a world haunted by the debris of chance encounters gone terribly wrong, whether they happened in 1492 or last week.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Language Is Migrant By Cecilia Vicuña

Taken from: South Issue #8 [documenta 14 #3]

http://www.documenta14.de/en/south/904_language_is_migrant

Language Is Migrant By Cecilia Vicuña

Language is migrant. Words move from language to language, from culture to culture, from mouth to mouth. Our bodies are migrants; cells and bacteria are migrants too. Even galaxies migrate.

What is then this talk against migrants? It can only be talk against ourselves, against life itself.

Twenty years ago, I opened up the word “migrant,” seeing in it a dangerous mix of Latin and Germanic roots. I imagined “migrant” was probably composed of mei, Latin for “to change or move,” and gra, “heart” from the Germanic kerd. Thus, “migrant” became “changed heart,”

a heart in pain, changing the heart of the earth.

The word “immigrant” says, “grant me life.”

“Grant” means “to allow, to have,” and is related to an ancient Proto-Indo-European root: dhe, the mother of “deed” and “law.” So too, sacerdos, performer of sacred rites.

What is the rite performed by millions of people displaced and seeking safe haven around the world? Letting us see our own indifference, our complicity in the ongoing wars?

Is their pain powerful enough to allow us to change our hearts? To see our part in it?

I “wounder,” said Margarita, my immigrant friend, mixing up wondering and wounding, a perfect embodiment of our true condition!

Vicente Huidobro said, “Open your mouth to receive the host of the wounded word.”

The wound is an eye. Can we look into its eyes?

my specialty is not feeling, just looking, so I say: (the word is a hard look.) —Rosario Castellanos I don’t see with my eyes: words are my eyes. —Octavio Paz

In l980, I was in exile in Bogotá, where I was working on my “Palabrarmas” project, a way of opening words to see what they have to say. My early life as a poet was guided by a line from Novalis: “Poetry is the original religion of mankind.” Living in the violent city of Bogotá, I wanted to see if anybody shared this view, so I set out with a camera and a team of volunteers to interview people in the street. I asked everybody I met, “What is Poetry to you?” and I got great answers from beggars, prostitutes, and policemen alike. But the best was, “Que prosiga,” “That it may go on”—how can I translate the subjunctive, the most beautiful tiempo verbal (time inside the verb) of the Spanish language? “Subjunctive” means “next to” but under the power of the unknown. It is a future potential subjected to unforeseen conditions, and that matches exactly the quantum definition of emergent properties.

If you google the subjunctive you will find it described as a “mood,” as if a verbal tense could feel: “The subjunctive mood is the verb form used to express a wish, a suggestion, a command, or a condition that is contrary to fact.” Or “the ‘present’ subjunctive is the bare form of a verb (that is, a verb with no ending).”

I loved that! A never-ending image of a naked verb! The man who passed by as a shadow in my film saying “Que prosiga” was on camera only for a second, yet he expressed in two words the utter precision of Indigenous oral culture.

People watching the film today can’t believe it was not scripted, because in thirty-six years we seem to have forgotten the art of complex conversation. In the film people in the street improvise responses on the spot, displaying an awareness of language that seems to be missing today. I wounder, how did it change? And my heart says it must be fear, the ocean of lies we live in, under a continuous stream of doublespeak by the violent powers that rule us. Living under dictatorship, the first thing that disappears is playful speech, the fun and freedom of saying what you really think. Complex public conversation goes extinct, and along with it, the many species we are causing to disappear as we speak.

The word “species” comes from the Latin speciēs, “a seeing.” Maybe we are losing species and languages, our joy, because we don’t wish to see what we are doing.

Not seeing the seeing in words, we numb our senses.

I hear a “low continuous humming sound” of “unmanned aerial vehicles,” the drones we send out into the world carrying our killing thoughts.

Drones are the ultimate expression of our disconnect with words, our ability to speak without feeling the effect or consequences of our words.

“Words are acts,” said Paz.

Our words are becoming drones, flying robots. Are we becoming desensitized by not feeling them as acts? I am thinking not just of the victims but also of the perpetrators, the drone operators. Tonje Hessen Schei, director of the film Drone, speaks of how children are being trained to kill by video games: “War is made to look fun, killing is made to look cool. ... I think this ‘militainment’ has a huge cost,” not just for the young soldiers who operate them but for society as a whole. Her trailer opens with these words by a former aide to Colin Powell in the Bush/Cheney administration:

OUR POTENTIAL COLLECTIVE FUTURE. WATCH IT AND WEEP FOR US. OR WATCH IT AND DETERMINE TO CHANGE THAT FUTURE – Lawrence Wilkerson, Colonel U.S. Army (retired)

In Astro Noise, the exhibition by Laura Poitras at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the language of surveillance migrates into poetry and art. We lie in a collective bed watching the night sky crisscrossed by drones. The search for matching patterns, the algorithms used to liquidate humanity with drones, is turned around to reveal the workings of the system. And, we are being surveyed as we survey the show! A new kind of visual poetry connecting our bodies to the real fight for the soul of this Earth emerges, and we come out woundering: Are we going to dehumanize ourselves to the point where Earth itself will dream our end?

The fight is on everywhere, and this may be the only beauty of our times. The Quechua speakers of Peru say, “beauty is the struggle.”

Maybe darkness will become the source of light. (Life regenerates in the dark.)

I see the poet/translator as the person who goes into the dark, seeking the “other” in him/herself, what we don’t wish to see, as if this act could reveal what the world keeps hidden.

Eduardo Kohn, in his book How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human notes the creation of a new verb by the Quichua speakers of Ecuador: riparana means “darse cuenta,” “to realize or to be aware.” The verb is a Quichuan transfiguration of the Spanish reparar, “to observe, sense, and repair.” As if awareness itself, the simple act of observing, had the power to heal. I see the invention of such verbs as true poetry, as a possible path or a way out of the destruction we are causing.

When I am asked about the role of the poet in our times, I only question: Are we a “listening post,” composing an impossible “survival guide,” as Paul Chan has said? Or are we going silent in the face of our own destruction?

Subcomandante Marcos, the Zapatista guerrilla, transcribes the words of El Viejo Antonio, an Indian sage: “The gods went looking for silence to reorient themselves, but found it nowhere.” That nowhere is our place now, that’s why we need to translate language into itself so that IT sees our awareness.

Language is the translator. Could it translate us to a place within where we cease to tolerate injustice and the destruction of life?

Life is language. “When we speak, life speaks,” says the Kaushitaki Upanishad.

Awareness creates itself looking at itself.

It is transient and eternal at the same time.

Todo migra. Let’s migrate to the “wounderment” of our lives, to poetry itself.

0 notes

Text

Finally, the Class War Is Out in the Open; or Why Trump Won the Election

APRIL 30, 2017

I was in Germany in November at the time of the American presidential election, and wrote the following essay on Nov. 9, the day after. I subsequently gave it as a lecture at the University of Mainz, but was unable to post or publish it because of lecture commitments I had made in Mexico for the spring of 2017. Those commitments have now come and gone, and so I'm free to post it at this time. Most of you will not find any surprises here, because we have been discussing these issues since Trump's victory. Nevertheless, I thought I would take the liberty of posting it; reviewing these things may possibly be of interest, even at this late date. Or at least, I hope so. Here goes:

A few months ago, I read in some online newspaper that the six richest people in the world owned as much as the bottom 50 percent, or 3.7 billion people. This is so bizarre a statistic that one would have to call it surreal. One wonders how we got to this state of affairs. As in the case of so many things, the United States is at the cutting edge of this development. Just for starters, most of those six individuals are Americans. But of course it goes deeper than this. The world economic system is fundamentally an American one, and is sometimes known as neoliberalism or globalization—fancy words for imperialism, in fact. And imperialism is a system in which the rich get richer, the poor get poorer, and the middle class gets slowly squeezed into oblivion.

American capitalism, of course, has been going on now for more than 400 years, as I describe it in my book

Why America Failed

. And yet one thing that can be said about social inequality in America is that it was relatively stable from 1776 down to about 1976, i.e. a period of 200 years. It existed, but for the most part it wasn’t harsh or extreme, save during the Gilded Age and the Depression, and it enabled Americans to believe that they were living in a classless society, or even that they were all middle class. As for the Depression, America pulled out of it due to the dramatic industrial development required by World War II, but Franklin Roosevelt was well aware that the nation needed something more viable than a war economy in order to sustain itself. And so in the summer of 1944, a conference on postwar financial arrangements was convened in a small town in New Hampshire called Bretton Woods, and the economic plan that was devised at that conference came to be known as the Bretton Woods Accords. The guiding light was the great British economist John Maynard Keynes, possibly the greatest economist who ever lived.

The Bretton Woods Accords put forward two key concepts. One, that the US dollar would be the international standard of exchange. All other currencies would be pegged to the dollar in value, and could always be traded in for dollars. Two, that the US Government would guarantee the value of the dollar, i.e. back the dollar, by means of gold bars kept in a vault in Fort Knox, Kentucky. The paper dollar, in other words, could be trusted completely. All of this was implemented as soon as the War was over, and it led to a remarkable period of prosperity, worldwide, for the next twenty-five years.

For a variety of reasons, Richard Nixon—not one of my favorite people—decided to repeal Bretton Woods, which he did in 1971. What this did was usher in a dramatic age of finance capitalism. Just to be clear, capitalism comes in three flavors. There is mercantile or commercial capital, in which wealth is derived from trade, and which flourished during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Then there is industrial capital, in which wealth is derived from manufactures, and which characterized the modern era, that is the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. And finally there is finance capital, in which wealth is not derived from trade or manufactures, but simply from currency speculation. This is what the repeal of Bretton Woods allowed, because with the removal of the gold standard, the currencies of the world had no intrinsic (dollar) value; they just floated against one another in a market place of constantly fluctuating exchange rates. Casino capitalism, we might also call it. Those who were rich could make huge amounts of money by speculating on currency rates, because they had large amounts of money to begin with. The rest of us—the so-called 99 percent—didn’t have the luxury of this, and were largely tied to a paycheck, if indeed we even had a job.

The effect of the repeal began to be noticed by 1973, and the gap between rich and poor began to widen noticeably thereafter. Ronald Reagan did his best to make it worse. His so-called “trickle down theory,” by which the wealth of the rich would supposedly spill over into the wallets of the poor and the middle class, was a farce. In a word, nothing trickled down. The rich decided to hang onto their wealth, rather than spread it around. What a surprise! And so today, in China as well as the United States, the top 1 percent own 47 percent of the wealth. In Mexico, thirty-four families are super-rich, while half the country wallows in poverty. And as I mentioned earlier, a handful of Americans own as much as the bottom 3.7 billion of the world’s population. As President Coolidge astutely remarked nearly 100 years ago, “The business of America is business.” John Maynard Keynes’ warning, that the economy was there to serve civilization rather than the reverse, was completely ignored.

“Reaganomics,” as it was called, got further entrenched with the fall of the Soviet Union. This event was taken, in the United States, as definitive proof that what was called the “Washington Consensus”—a neoliberal, globalized economy—was not merely the wave of the future, but indeed the

only

wave of the future. Political scientist Francis Fukuyama wrote a very famous, and very stupid, book declaring that we were now living in a unipolar world; that America, in short, was the end of history. It’s actually a very old idea, going back to 1630, that America would be the model for the rest of the world—“a city upon a hill.” American politicians love to quote that line. Meanwhile, the light of that city was getting dimmer for most of the American population.

And yet, in the face of all this, Americans continued to believe that they were living in a classless society, or that everyone was middle class. You wonder how stupid a nation can be, really; other nations are hardly so deluded. The author John Steinbeck famously remarked that socialism was never able to take root in America because the poor saw themselves as “temporarily embarrassed millionaires.” As I argue in

Why America Failed

, everyone in the US is a hustler; everyone is just waiting for their ship to come in.

In any case, Bush Sr. continued the pattern, as did Bill Clinton. The passage of NAFTA benefited the US at the expense of the so-called Third World, with economic bailouts from the IMF tied to austerity measures that sent peasants in Chiapas, for example, into starvation—and rebellion. The rise of Subcomandante Marcos, and the Zapatistas, was to be expected. But the machinery rolled on. Bush Jr. correctly referred to the super-rich as “my base,” and the Obama presidency, despite a lot of flowery language, was a continuation of Bush Jr. After the crash of 2008, Obama didn’t bail out the poor or create jobs; not at all. He bailed out his rich banker friends to the tune of $19 trillion dollars, while the middle class lost their jobs and their homes and lined up at soup kitchens for the first time in their lives. Tent cities for them, and the working class, blossomed across the country, and Obama did nothing. As for Hillary—and this is a crucial point—what she was essentially promising was an extension of the neoliberal regime that had been in place since her husband took office in 1993. When Trump pointed at her, during the presidential debates, and said to the audience: “If you want a continuation of the last eight years, vote for her,” the people whom globalization had destroyed heard him loud and clear.

Trump seemed clumsy and boorish during the debates; in fact, he knew what he was doing. “What does Hillary have to show for thirty years of political involvement?” he cried. “Everything she is telling you is words, just words. She has nothing to offer you.” He was right, and millions of Americans knew it. Her slogans, like “Stronger Together,” were meaningless. He was speaking about reality, while she was reading from a script. She also

looked

as though she were programmed. Unfortunately for her, she tended to smile a lot, and it was so forced that she occasionally came across as insane.

In any case, things had changed since she was First Lady. After twenty-five years of neoliberal economics, the white working class understood that politics as usual had nothing to offer them; that Hillary was just a variation on the Obama regime, which had hurt them badly. There was now a realization that their ship would never come in, that they would never be able to participate in the American Dream; that they were

permanently

embarrassed

non

-millionaires. They had a deep, and justifiable, resentment against Washington, Wall Street, the

New York Times

, and all such establishment symbols, and their desire was to say to that establishment, and to the American intellectual elite—pardon my French—go fuck yourselves. Precisely by being vulgar and blunt, and not coming across as a smooth operator like Obama, Trump was winning a large part of America over to his side. Even his body language said “fuck you.”

Trump’s authenticity was also noticeable in his adoption of a declinist position, the first presidential candidate in American history to do this in a serious way. After all, if your campaign slogan is “Make America Great Again,” you are saying that the country is in decline, and that’s exactly what Trump was saying. Our airports resemble those of Third World countries, our roads and bridges are falling apart, our inner cities are filled with crime, our educational system is a joke—and so on. All of this is absolutely true, while Hillary could only come up with a feeble, and hollow, rejoinder: “When was America not great?” Give me a break.

Let me return a moment to the matter of the resentment of the American intellectual elite, the so-called liberal or professional class, which includes much of the Democratic Party. This is a largely untold story, and yet I regard it an absolutely crucial factor in the election of Trump. The same year that Nixon repealed Bretton Woods, 1971, a prominent Washington Democrat by the name of Fred Dutton published a manifesto called

Changing Sources of Power

. What he said in that document was that it was time for the Democratic Party to forget about the working class. This is not your voting base, he declared; the people you want to court are the white-collar workers, the college-educated, the hip technologically oriented, and so on. Forget about economic issues, he went on; it’s much more a question of lifestyle than anything else. This was the key ideology in the rise of the so-called New Democrats, who in effect repudiated their traditional base and indeed, the whole of Roosevelt’s New Deal, which had historically provided a safety net for that base. Bill Clinton was part of that wave, and during his presidency we saw not only a widening gap between rich and poor, but NAFTA, the abolition of welfare, and the so-called “Three Strikes” law, which put huge numbers of black men into prison for as much as twenty years for minor crimes, thereby destroying their families’ ability to survive. Hillary was also part of that wave, and as Trump and his supporters understood, she was going to court the chic and the hip, not the folks that neoliberalism had ground into the dirt. As it turned out, 53 percent of white women voted for Trump; they were not taken in by Hillary’s gender politics. (For more on this see Nicholas Lemann, “Can We Have a ‘Party of the People’?”

New York Review of Books

, 13 October 2016, pp. 48-50)

Which brings me to the final point. If the liberal class abandoned their traditional working-class base; if they had stopped, from the early 1970s, fighting for the New Deal ideology; then what ideology did they adopt? This is the saddest, and most ridiculous, chapter in the history of the left in the US: they became preoccupied with language, with political correctness—the sorts of things that not only could do nothing to improve the condition of the working class, but which were actually offensive to that class. God forbid one should say “girls” instead of “women,” or “blacks” instead of “African Americans,” or tell an ethnic joke. Left-wing projects now consisted in rewriting the works of great authors like Mark Twain, so that their nineteenth-century texts might not give offense to contemporary ears. The children of the rich, at elite universities, had to be protected from any kind of direct language. When some students at Bowdoin College in Maine, in 2016, decided to hold a Mexican theme party, complete with tequila and mariachi music, the rest of the campus was in an uproar, calling this “cultural appropriation.” Apparently, only Mexicans are allowed to drink tequila, in the politically correct world. Personally, I regarded this party as a

tribute

to Mexican culture; what does “appropriation” mean, anyway? In 2015 I published a cultural history of Japan, called

Neurotic Beauty

. Am I not allowed to do this, because I’m not Japanese? Should Octavio Paz have never written about India? All of this is quite ridiculous, and amounted to a callous neglect of the working class on the part of people who had traditionally fought for that class, for its survival. So while the working class and the middle class found itself confronted with real problems—no job, no home, no money, and no meaning in their lives—the chic liberal elite was preoccupied with who has the legal right to use transgender bathrooms. Well, I’d be angry too.

Just as a side note: In 1979, Christopher Lasch wrote a book called

The Culture of Narcissism

, in which he argued that during the sixties, we discovered that we were powerless to change the things that really mattered, namely the relations of class and power. As a result, in the seventies we decided to pour our energies into the things that didn’t matter at all, and political correctness is a good example of this. It’s not really politics, in other words; it’s a substitute for politics, and thus a waste of everyone’s time.

In any case, Hillary never understood this. She attacked Trump in the debates for being politically incorrect, when it was precisely that incorrectness that was the source of his appeal. She called his followers—many millions of Americans—“a basket of deplorables.” They didn’t appreciate being looked down upon, especially since the liberal elite had gotten wealthy at their expense. In her pathetic concession speech, on November 9, she still kept appealing to “Diversity,” to “Stronger Together,” and said how she hoped she would be an inspiration to little girls—apparently, in her politically correct world, little boys don’t count. The only one thing she got right in that speech was her observation that the nation was deeply polarized—“we didn’t realize how deeply,” she added. No kidding. The “deplorables” proved to be not so deplorable after all. They knew who their friends were, and they knew she wasn’t one of them.