#i know i could import all my stuff to firefox directly

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

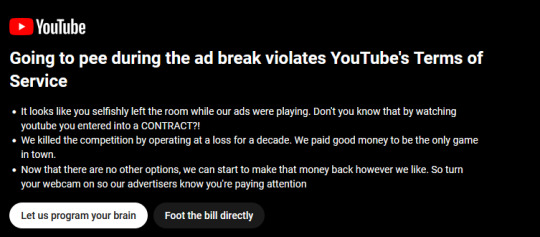

Wow, this blew up. This was a silly post i made before i'd had my coffee or meds but its a sentiment i've been thinking about a lot recently. ive been reading through the notes and theres way too many to reply to. but they mostly fall into these categories: apollo dodgeball / if you knock on enough doors asking for the devil: I think thats actually a big part of why i made this. Youtube (or any corporation) will do everything it can to make more money. they would implement this in a second if it were both technologically feasible and socially acceptable (or at least, acceptable enough to not cause too much of a backlash). a decade ago, this concept met neither criteria. now its dangerously close to meeting both.

The web was built on a model where the website sends you content and a suggestion of how to render it - to give users the freedom to interact with it however they choose. Since then, there's been a battle between corporations and this principle as they use every trick they can come up with to force you to render the content the way they want you to.

The most effective way that corporations have achieved this is with apps. Paraphrasing Cory Doctorow[1], an app is just a website that its illegal to mess with. So many of the notes are people saying "i wish i could block youtube ads on my phone/smart tv/game console". this is a problem, and a bad sign of what to come.

another thing that makes this concept technologically feasible and socially acceptable in my opinion is face id. Having a camera scan your face automatically before letting you progress has become normal. Its common to put tape over your webcam, but nobody puts tape over their phone camera. Somehow, we've been trained to view it differently. more broadly, I dont think the web is meant to be profitable. The old internet was full of small forums run at a loss fueled by the passion of their creators. When corporations moved in down the road with enough money to drive the forums away and take over, those corporations still didnt turn a profit. and they havent for a decade. Now they're getting desperate and they're going to extract as much as they can from their users to try and recoup those costs. Your outrage over the concept of this is important. Visible backlash to hostile practices works. its important that we all say Fuck That loudly and often. Youtube is adding a five second delay for firefox users: I read about this immediately after making the original post. this is such a brazen move by google. I hope they get in some serious shit for leveraging one monopoly to bolster another but im not familiar enough with international law to know if thats likely.

Regardless, google has been showing their hand lately with so many hostile decisions. Their only leverage is their user base. Don't help them. Switch to firefox. if you need to, you can make firefox pretend to be chrome for specific websites Ads are getting worse / loud ads in asmr videos / pragerU and other evil ads: Ad blocking still works! please use an ad block! install ublock origin! Youtube is working hard break ad blockers but the ublock devs are working harder to keep them working. you just need to update the filter lists every now and then. here's a guide I still want to support creators: Find a way to support them directly! youtube is a notoriously unreliable income source. Check how the creator you want to support would prefer you support them. Chucking them a few bucks once will go a lot further than watching ads.

Piss kink references: Thank you tumblr for being tumblr. A lot of the replies have been pretty heavy so these silly responses have been surprisingly refreshing.

----

I highly recommend Cory doctorow's defcon talk about the state of the web and how we can fix it. it put words to things i'd been feeling for a long time and introduced me to new ways of thinking about some of this stuff. Its linked at the bottom.

Its been wild having this post break containment like this. Tumblr is my place for shouting into the void and im used to most of my original posts not getting much traction (which is fine, or maybe even the point). the concept of over thirty thousand people reading something i wrote is hard to even conceptualize. I wasn't at all prepared for this but its touching that so many people resonated with my anger and frustration.

Okay, i'm going to go outside and remind myself that there is still so much good in the world. Fighting corporations is important but don't forget to also marvel at a cool bug or something to balance it out [1] - DEF CON 31 - An Audacious Plan to Halt the Internet's Enshittification - Cory Doctorow [Invidious link] [yt]

72K notes

·

View notes

Text

this is a daily reminder to stop the habit of opening chrome and getting more and more things to firefox

#i know i could import all my stuff to firefox directly#but the thing is i've been using firefox for business stuff for ages#so there are some accounts i'm leaving in chrome..... but i still wanna use firefox most of the time#i should also get gyazo here and install it on my phone mmm

0 notes

Note

Not to pry, but i saw your tags and i would love to hear any thoughts you have on what cornelia could have done w capricorn and basta instead of doing them like That, if you have any ideas/opinions?

really sorry for the late reply, but totally! ((and thank you for asking!!))

okay so, first off, Capricorn. I want to say that I’m not actually super upset by Capricorn’s death since the ending of Inkheart is great in my opinion, and narratively speaking it really ties everything up pretty neatly and cleanly in a satisfying way. it serves the story VERY well and is very gratifying since Capricorn is just nasty enough that we’re all very, very glad to see him get his just desserts.

I said that killing Capricorn off was a bad move, and what I mean is that, because of the way the other villains are written in Inkspell and Inkdeath, the stark contrast between them and Capricorn as a villain in Inkheart really grates on me, because I know Cornelia Funke can write really cool and intriguing yet blatantly evil and unsympathetic villains, but I don’t feel like the story delivers on that in the other books like Inkheart did, and it basically feels like we might as well have just kept Capricorn alive and let him do the cool scary stuff the rest of the story, lmao.

he’s such a good antagonist, but I don’t legitimately want his death undone or him to actually play a part post-Inkheart because I feel like Capricorn belongs squarely in Inkheart, in the real world, untouched by fantasy or magic or anything that delegitimizes how really, scarily, human Capricorn and his evils are. I feel like he really thrived in our world for a good reason, and I don’t rlly want to mess that up.

(also I think it’s interesting to note how the Inkworld trilogy is basically on a sliding scale of realness to pure story, and both of what I consider the strongest terrifyingly legit villains never make it to the last installment, where it directly crosses over into actual fantasy, instead of just nudging at it.)

what I’d have liked to see is actually maybe flashbacks of Capricorn. more mentions of him. some connections, more than just Mortola’s motivation in Inkspell or passing references to the former fire-raisers, you know? I stand by the fact that Capricorn is a villain fitted better to the irl world, but I also don’t like the feeling that Capricorn was just plucked out of thin air and never had a real impact on the Inkworld, which is what we get in Inkspell, to me. I want to know that the Capricorn that terrified us in Inkheart is the same Capricorn who used to have his own posse of men at his beck and call in the Inkworld.

also bit of a tangent but, this goes in general as well as a complaint I have for Inkspell. I want to feel like all of these supposed characters from the Inkheart book are real and their pasts matter, like Inkspell didn’t just drop us and the main characters into a world that doesn’t really exist and doesn’t really have any stakes, which is, unfortunately how it kinda feels to me. and I think Capricorn is a big part of that, given how huge a presence he has and how huge a part he plays in Inkheart. you can argue that it’s just foreshadowing in a way, that the Capricorn who made such a big impact in the very first story is only the tip of iceberg, he’s only a minor player in the real world of Inkheart, which is a very fair assessment, but I think it also has the unintended consequence of making the Inkworld feel less like a cohesive universe separate from ours and more like, well, a story, because of that.

my opinion about Capricorn’s past in the Inkworld also goes hand-in-hand with my opinions on Firefox–I would have loved to hear more about his past as a fire-raiser under Capricorn and what Capricorn was like then, what Firefox’s personal investment in that line of work was and how he was brought into it, his relationship with Capricorn and the others.

basically his stake in the story and his opinions of the old fire-raisers vs the new work under the Adderhead. I feel like Firefox would have been a really good way to connect the lore of Inkheart only mentioned in the first book and what we actually see stepping into the world itself in Inkspell. he has the right history to give us backstory and insight into the past we’ve heard of, while also bringing us into what the future of the Inkworld looks like right now and how it’s changed.

and Firefox is also an excellent way to fix my issues with Basta’s plot.

so my thoughts on Basta! I feel kinda the same about him as Capricorn, in a way, that his death is deserved and in it’s own way poetic (the fact that in the end, Basta is nothing more than an awful man whose death is only a footnote to the story at large) but his death is not very satisfying as a reader who’s been extremely invested in his role in the story up until that point. narratively I don’t think I actually have a huge problem with the decision to kill off Basta because it all checks out, but I also think it causes some other issues.

what I mean is, Basta is the most personal of the Inkworld trilogy villains, and I think serves an important role as sort of the bridge between the readers and more distant, high stakes of the story. AKA he is the very real, very intimate reminder of what exactly the heroes are fighting for and against, and what will happen if they lose–men like Basta will win. he also provides good interpersonal villainy that helps develop characters and move the story along in a way that a Bigger And Badder villain just can’t. and I think that taking him out of play while also not adding in anything else that serves the same role kinda takes away the tension in the story, I think.

I mean, the stakes are still there, it’s kinda hard to NOT feel the weight of the mass-murder of children but tension (as in narrative tension) is really important in a story and I don’t really feel that as much in Inkdeath as in the first two books? and I do think the villains are responsible for that (or also the lack of certain villains.)

I just honestly feel like the pros of Basta’s death in the story don’t outweigh the consequences.

what I would have liked to have seen, that I think fixes all my issues, is a Basta and Firefox team up in Inkdeath. Firefox always seemed awfully dissatisfied with his new job working for the Adderhead to me, and there are just SO MANY villains in Inkdeath working at once, all with their own agendas and own little teams, the idea of them all being at odds with each other while all also trying to capture the main characters is VERY cool.

like, you have, of course, the Piper, with his high-ranking station in the Adderhead’s court, being The Dragon to the Adderhead’s Big Bad. the very classic, very regal and threatening villains who make up the serious problem in the big story, the ones who are driving the actual plot going on. they’re the ones who have the resources and who actually have to be defeated by the characters and not just avoided.

and then imagine you have, pitted against them, Basta and Firefox, and Orpheus and Mortola, all working for their own ends and own reasons. Orpheus and Mortola who are pretending to be allied with the Piper and the Adderhead while working their own sneaky underhanded schemes in the shadows, and Basta and Firefox who have publicly defected from the Adderhead and are in hiding just as much as the heroes, while still trying to make their moves.

like Inkspell gives so much basis for a Piper/Firefox rivalry with no delivery and that’s a shame!!! I really feel like he was wasted as a character, and the question is not about him, but I REALLY feel like fixing Firefox’ arc in the books would automatically tie together a lot of other stuff.

and we all also know how lost Basta is without a master to devote himself to, and we know how displeased Firefox is as the Adderhead’s servant.

Mortola has absolutely no ties to Basta other than he’s convenient and loyal to her as an extension of his former loyalty to Capricorn–he’s an easy tool to use. Inkdeath already has Mortola growing steadily more unhinged and illogical as she accepts her own irrelevance after Capricorn’s death, so it’s totally plausible she might abandon Basta completely to go about her own goals when she decides to work with Orpheus, and of course Basta would flounder.

and so Basta, unsure and looking for any anchor to give him a purpose, would look for some sort of familiarity and companionship, and there’s two options there: the Piper or Firefox. the Piper is steadfast in his own loyalty to the Adderhead if for no other reason than greed, and Basta can’t stand him nowadays and never liked the Adderhead.

Firefox was someone Basta used to work with who is still someone Basta can at least tolerate. Firefox has his own issues with the Piper and the Adderhead and those two would be able to find common ground in that, and their other issues with how things are nowadays in the Inkworld

I can very easily see Basta persuading Firefox into a mutually beneficial partnership, speaking about his own experience with the Bluejay and his allies, and convincing Firefox to jump ship entirely. and I feel like Firefox might thrive under the ability to work with his own rules, unchallenged.

like seriously. Firefox who comes into himself and really becomes his own leader and own serious antagonist to be reckoned with, and gaining Basta’s respect and loyalty. them having a very good working relationship together as mostly equals, where Basta gives advice and information as a henchman, and Firefox actually calls the shots and plans the strategy. and they serve the same purpose in Inkdeath that Basta and Mortola did in Inkspell, that Basta and Flatnose and Cockerell served in Inkheart.

and that ties back into the post-Inkheart Capricorn disappearance, because with two of his former best men becoming allies later in the story, there’s plenty of room for mentions of him and backstory with the fire-raisers and how Basta and Firefox (and the Piper!!) all knew each other, and then how they used to interact with the rest of the Inkworld (Dustfinger, the Black Prince, Cosimo, etc) under Capricorn’s orders.

I just. h. feel like it would have been really cool to see Mo and Meggie and Dustfinger and everyone struggle against so many enemies from all sides, each with their own special ways of causing issues that have to be overcome. I would like to see that Piper and Firefox rivalry and confrontation and the consequences. I would really like to see Basta’s arc have him devoting himself to someone else and what that means for him, as a character.

I REALLY would like the antagonist situation in Inkdeath to be a lot more personal and interesting and complex.

anyway uh.

TL;DR:

my main issue with Capricorn isn’t his actual death, but how his time as an antagonist contrasts with how the villain situation ends up later, aka Not As Cool In My Personal Opinion (And These Guys Wish They Could Live Up To The Standard Capricorn Set). still would LOVE to see backstory of him regarding other villains that ties the whole universe together.

Basta’s death is valid but unsatisfying and I honestly really really miss him as a character in Inkdeath and because he was fun and delightfully horrible and twisted and I think he served an important purpose.

I think the way to fix both of these issues is UTILIZING FIREFOX.

I hope this sums up all my feelings and ideas about this subject well!

#TRIED TO DO A READMORE BUT TUMBLR WON'T LET ME FOR SOME REASON SO RIP TO EVERYONE WHO FOLLOWS ME AND SEES THIS LONG POST ON THEIR DASH#oh man this is so long#i'm rlly hope i've adequately expressed how cool i think the separate villain team-ups and rivalries would be bc#that would be so fucking neat and interesting#like i rlly think villains make a story and. idk if controversial opinion. but they're really not bringing it in inkspell and inkdeath#firefox is just woefully underused and the piper is frankly. kind of bland from everything i've seen of him#which is sad!!! they're full of such potential and i know cornelia funke can do really interesting and satisfying villains!!!#basta is rlly knifing his little heart out carrying the entire good villain characterization in inkspell on his shoulders#also again i really really cannot reasonably ask for capricorn to live past inkheart because its SUCH a good ending#but hes also s U CH A GOOD ANTAGONIST#HES SO AWFUL BUT SO ENTERTAINING TO READ#and i miss him especially when the rest of the villain situation isn't as fun#why can't yall be capricorn#anyway i've rambled enough on this fsdlifhgsidgsd#mine#inkheart#inkheart (book)#inkspell#inkdeath#capricorn#basta#firefox#uhh#aus#long post//

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

968

Finally got around to installing xkit, and it sure does make it easier to add posts to my queue on theEmberFlare. It mainly took this long because the official add-on isn’t available from, like Firefox directly, so you have to get it from GitHub. But just that extra step is, like, scary to me. I don’t know; I guess it’s just that I have very little experience with GitHub. I vaguely understand that it’s where software developers can make their stuff available, but I’m, like, ignorant of whether or not anything from there can be malicious. I’m sure I can look it up, but that’s even more steps—that I’m not exactly confident in taking either, because I’m not confident in doing research and looking things up. There’s the “unofficial” version available through Firefox, but the fact that it’s unofficial is also scary.

As an aside, I’ve been using the word “scary” instead of “anxiety-inducing” or “stressful”, because I’m using it to explore my suspected paranoia. I feel like I’ve been downplaying it this whole time—not just on this blog, but ever since being aware of my own mental health issues—by lumping it in with anxiety and stress. It’s possibly more accurate that I experience crippling, paralyzing fear of... things. I don’t know, maybe “paranoia” isn’t even quite the right word, but it’s what I happen to know.

Hmm, briefly looking it up, “delusions” seem to come up a lot. I’m not sure if I could accurately describe my experiences as delusions, at least not in ways that line up with these examples. Though, it’s possible that this sort of stuff is going on in my periconsciousness. Like, I could have certainly learned to suppress thoughts that would clearly be indicative of delusions such that I experience them as very vague anxieties. But maybe, if I interrogate those anxieties deeply enough, I might find that they are rooted in some sorts of delusions.

I mean, one that I have confidently identified before already is this, like, persistent fear of people in the neighborhood being aware of me: as if any of them might come after me [for being queer or any other reason]. I don’t have any particular justification for this: at most, I can say that I live in the southern US.

Hmm, I do also experience these intrusive thoughts of how I could potentially get into accidents whenever I drive. I’d categorized it under “catastrophizing” as a term I learned in regards to depression and anxiety. But it probably also applies to paranoia.

Oh! And there’s the big childhood delusion that led me to have suicidal thoughts as early as the fourth grade: the idea that I was just, like, fundamentally “wrong” somehow and deserved to have terrible things happen to me. For most of the past decade, I think I’ve had that logged as being due to dysphoria, but—while dysphoria can totally be an influence—there can quite possibly be other things going on.

And I’m confident that I’m not romanticizing extreme mental illness/disorder and wanting that for myself for, like, clout somehow. It’s more likely to me that I’ve been severely downplaying my symptoms due to internalized ableism. This whole time I’ve wanted to believe that I can get a handle on things with just a ltitle bit of effort: just some journaling, philosophizing, and self care is all. That most of my problems just come down to capitalism.

But if I’m truly, seriously honest about the symptoms I’ve lived with my whole life, I’d probably still be messed up in an anarchist/communist society. Of course, such a society would likely better accommodate my issues, but that’s the thing: if I’m being honest, I must admit that I’d likely still need accommodations even without capitalism.

And being honest about these sorts of things is important for me to be able to accurately identify my own needs, such that I can better form goals around them.

0 notes

Text

How to Think Like a Front-End Developer

This is an extended version of my essay “When front-end means full-stack” which was published in the wonderful Increment magazine put out by Stripe. It’s also something of an evolution of a couple other of my essays, “The Great Divide” and “Ooops, I guess we’re full-stack developers now.”

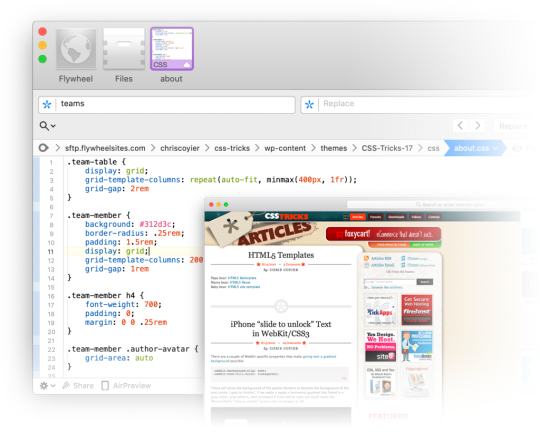

The moment I fell in love with front-end development was when I discovered the style.css file in WordPress themes. That’s where all the magic was (is!) to me. I could (can!) change a handful of lines in there and totally change the look and feel of a website. It’s an incredible game to play.

Back when I was cowboy-coding over FTP. Although I definitely wasn’t using CSS grid!

By fiddling with HTML and CSS, I can change the way you feel about a bit of writing. I can make you feel more comfortable about buying tickets to an event. I can increase the chances you share something with your friends.

That was well before anybody paid me money to be a front-end developer, but even then I felt the intoxicating mix of stimuli that the job offers. Front-end development is this expressive art form, but often constrained by things like the need to directly communicate messaging and accomplish business goals.

Front-end development is at the intersection of art and logic. A cross of business and expression. Both left and right brain. A cocktail of design and nerdery.

I love it.

Looking back at the courses I chose from middle school through college, I bounced back and forth between computer-focused classes and art-focused classes, so I suppose it’s no surprise I found a way to do both as a career.

The term “Front-End Developer” is fairly well-defined and understood. For one, it’s a job title. I’ll bet some of you literally have business cards that say it on there, or some variation like: “Front-End Designer,” “UX Developer,” or “UI Engineer.” The debate around what those mean isn’t particularly interesting to me. I find that the roles are so varied from job-to-job and company-to-company that job titles will never be enough to describe things. Getting this job is more about demonstrating you know what you’re doing more than anything else¹.

Chris Coyier Front-End Developer

The title variations are just nuance. The bigger picture is that as long as the job is building websites, front-enders are focused on the browser. Quite literally:

front-end = browsers

back-end = servers

Even as the job has changed over the decades, that distinction still largely holds.

As “browser people,” there are certain truths that come along for the ride. One is that there is a whole landscape of different browsers and, despite the best efforts of standards bodies, they still behave somewhat differently. Just today, as I write, I dealt with a bug where a date string I had from an API was in a format such that Firefox threw an error when I tried to use the .toISOString() JavaScript API on it, but was fine in Chrome. That’s just life as a front-end developer. That’s the job.

Even across that landscape of browsers, just on desktop computers, there is variance in how users use that browser. How big do they have the window open? Do they have dark mode activated on their operating system? How’s the color gamut on that monitor? What is the pixel density? How’s the bandwidth situation? Do they use a keyboard and mouse? One or the other? Neither? All those same questions apply to mobile devices too, where there is an equally if not more complicated browser landscape. And just wait until you take a hard look at HTML emails.

That’s a lot of unknowns, and the answers to developing for that unknown landscape is firmly in the hands of front-end developers.

Into the unknoooooowwwn. – Elsa

The most important aspect of the job? The people that use these browsers. That’s why we’re building things at all. These are the people I’m trying to impress with my mad CSS skills. These are the people I’m trying to get to buy my widget. Who all my business charts hinge upon. Who’s reaction can sway my emotions like yarn in the breeze. These users, who we put on a pedestal for good reason, have a much wider landscape than the browsers do. They speak different languages. They want different things. They are trying to solve different problems. They have different physical abilities. They have different levels of urgency. Again, helping them is firmly in the hands of front-end developers. There is very little in between the characters we type into our text editors and the users for whom we wish to serve.

Being a front-end developer puts us on the front lines between the thing we’re building and the people we’re building it for, and that’s a place some of us really enjoy being.

That’s some weighty stuff, isn’t it? I haven’t even mentioned React yet.

The “we care about the users” thing might feel a little precious. I’d think in a high functioning company, everyone would care about the users, from the CEO on down. It’s different, though. When we code a <button>, we’re quite literally putting a button into a browser window that users directly interact with. When we adjust a color, we’re adjusting exactly what our sighted users see when they see our work.

That’s not far off from a ceramic artist pulling a handle out of clay for a coffee cup. It’s applying craftsmanship to a digital experience. While a back-end developer might care deeply about the users of a site, they are, as Monica Dinculescu once told me in a conversation about this, “outsourcing that responsibility.”

We established that front-end developers are browser people. The job is making things work well in browsers. So we need to understand the languages browsers speak, namely: HTML, CSS, and JavaScript². And that’s not just me being some old school fundamentalist; it’s through a few decades of everyday front-end development work that knowing those base languages is vital to us doing a good job. Even when we don’t work directly with them (HTML might come from a template in another language, CSS might be produced from a preprocessor, JavaScript might be mostly written in the parlance of a framework), what goes the browser is ultimately HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, so that’s where debugging largely takes place and the ability of the browser is put to work.

CSS will always be my favorite and HTML feels like it needs the most love — but JavaScript is the one we really need to examine The last decade has seen JavaScript blossom from a language used for a handful of interactive effects to the predominant language used across the entire stack of web design and development. It’s possible to work on websites and writing nothing but JavaScript. A real sea change.

JavaScript is all-powerful in the browser. In a sense, it supersedes HTML and CSS, as there is nothing either of those languages can do that JavaScript cannot. HTML is parsed by the browser and turned into the DOM, which JavaScript can also entirely create and manipulate. CSS has its own model, the CSSOM, that applies styles to elements in the DOM, which JavaScript can also create and manipulate.

This isn’t quite fair though. HTML is the very first file that browsers parse before they do the rest of the work needed to build the site. That firstness is unique to HTML and a vital part of making websites fast.

In fact, if the HTML was the only file to come across the network, that should be enough to deliver the basic information and functionality of a site.

That philosophy is called Progressive Enhancement. I’m a fan, myself, but I don’t always adhere to it perfectly. For example, a <form> can be entirely functional in HTML, when it’s action attribute points to a URL where the form can be processed. Progressive Enhancement would have us build it that way. Then, when JavaScript executes, it takes over the submission and has the form submit via Ajax instead, which might be a nicer experience as the page won’t have to refresh. I like that. Taken further, any <button> outside a form is entirely useless without JavaScript, so in the spirit of Progressive Enhancement, I should wait until JavaScript executes to even put that button on the page at all (or at least reveal it). That’s the kind of thing where even those of us with the best intentions might not always toe the line perfectly. Just put the button in, Sam. Nobody is gonna die.

JavaScript’s all-powerfulness makes it an appealing target for those of us doing work on the web — particularly as JavaScript as a language has evolved to become even more powerful and ergonomic, and the frameworks that are built in JavaScript become even more-so. Back in 2015, it was already so clear that JavaScript was experiencing incredible growth in usage, Matt Mullenweg, co-founder of WordPress, gave the developer world homework: “Learn JavaScript Deeply”³. He couldn’t have been more right. Half a decade later, JavaScript has done a good job of taking over front-end development. Particularly if you look at front-end development jobs.

While the web almanac might show us that only 5% of the top-zillion sites use React compared to 85% including jQuery, those numbers are nearly flipped when looking around at front-end development job requirements.

I’m sure there are fancy economic reasons for all that, but jobs are as important and personal as it gets for people, so it very much matters.

So we’re browser people in a sea of JavaScript building things for people. If we take a look at the job at a practical day-to-day tasks level, it’s a bit like this:

Translate designs into code

Think in terms of responsive design, allowing us to design and build across the landscape of devices

Build systemically. Construct components and patterns, not one-offs.

Apply semantics to content

Consider accessibility

Worry about the performance of the site. Optimize everything. Reduce, reuse, recycle.

Just that first bullet point feels like a college degree to me. Taken together, all of those points certainly do.

This whole list is a bit abstract though, so let’s apply it to something we can look at. What if this website was our current project?

Our brains and fingers go wild!

Let’s build the layout with CSS grid.

What fonts are those? Do we need to load them in their entirety or can we subset them? What happens as they load in? This layout feels like it will really suffer from font-shifting jank.

There are some repeated patterns here. We should probably make a card design pattern. Every website needs a good card pattern.

That’s a gorgeous color scheme. Are the colors mathematically related? Should we make variables to represent them individually or can we just alter a single hue as needed? Are we going to use custom properties in our CSS? Colors are just colors though, we might not need the cascading power of them just for this. Should we just use Sass variables? Are we going to use a CSS preprocessor at all?

The source order is tricky here. We need to order things so that they make sense for a screen reader user. We should have a meeting about what the expected order of content should be, even if we’re visually moving things around a bit with CSS grid.

The photographs here are beautifully shot. But some of them match the background color of the site… can we get away with alpha-transparent PNGs here? Those are always so big. Can any next-gen formats help us? Or should we try to match the background of a JPG with the background of the site seamlessly. Who’s writing the alt text for these?

There are some icons in use here. Inline SVG, right? Certainly SVG of some kind, not icon fonts, right? Should we build a whole icon system? I guess it depends on how we’re gonna be building this thing more broadly. Do we have a build system at all?

What’s the whole front-end plan here? Can I code this thing in vanilla HTML, CSS, and JavaScript? Well, I know I can, but what are the team expectations? Client expectations? Does it need to be a React thing because it’s part of some ecosystem of stuff that is already React? Or Vue or Svelte or whatever? Is there a CMS involved?

I’m glad the designer thought of not just the “desktop” and “mobile” sizes but also tackled an in-between size. Those are always awkward. There is no interactivity information here though. What should we do when that search field is focused? What gets revealed when that hamburger is tapped? Are we doing page-level transitions here?

I could go on and on. That’s how front-end developers think, at least in my experience and in talking with my peers.

A lot of those things have been our jobs forever though. We’ve been asking and answering these questions on every website we’ve built for as long as we’ve been doing it. There are different challenges on each site, which is great and keeps this job fun, but there is a lot of repetition too.

Allow me to get around to the title of this article.

While we’ve been doing a lot of this stuff for ages, there is a whole pile of new stuff we’re starting to be expected to do, particularly if we’re talking about building the site with a modern JavaScript framework. All the modern frameworks, as much as they like to disagree about things, agree about one big thing: everything is a component. You nest and piece together components as needed. Even native JavaScript moves toward its own model of Web Components.

I like it, this idea of components. It allows you and your team to build the abstractions that make the most sense to you and what you are building.

Your Card component does all the stuff your card needs to do. Your Form component does forms how your website needs to do forms. But it’s a new concept to old developers like me. Components in JavaScript have taken hold in a way that components on the server-side never did. I’ve worked on many a WordPress website where the best I did was break templates into somewhat arbitrary include() statements. I’ve worked on Ruby on Rails sites with partials that take a handful of local variables. Those are useful for building re-usable parts, but they are a far cry from the robust component models that JavaScript frameworks offer us today.

All this custom component creation makes me a site-level architect in a way that I didn’t use to be. Here’s an example. Of course I have a Button component. Of course I have an Icon component. I’ll use them in my Card component. My Card component lives in a Grid component that lays them out and paginates them. The whole page is actually built from components. The Header component has a SearchBar component and a UserMenu component. The Sidebar component has a Navigation component and an Ad component. The whole page is just a special combination of components, which is probably based on the URL, assuming I’m all-in on building our front-end with JavaScript. So now I’m dealing with URLs myself, and I’m essentially the architect of the entire site. [Sweats profusely]

Like I told ya, a whole pile of new responsibility.

Components that are in charge of displaying content are almost certainly not hard-coded with data in them. They are built to be templates. They are built to accept data and construct themselves based on that data. In the olden days, when we were doing this kind of templating, the data has probably already arrived on the page we’re working on. In a JavaScript-powered app, it’s more likely that that data is fetched by JavaScript. Perhaps I’ll fetch it when the component renders. In a stack I’m working with right now, the front end is in React, the API is in GraphQL and we use Apollo Client to work with data. We use a special “hook” in the React components to run the queries to fetch the data we need, and another special hook when we need to change that data. Guess who does that work? Is it some other kind of developer that specializes in this data layer work? No, it’s become the domain of the front-end developer.

Speaking of data, there is all this other data that a website often has to deal with that doesn’t come from a database or API. It’s data that is really only relevant to the website at this moment in time.

Which tab is active right now?

Is this modal dialog open or closed?

Which bar of this accordion is expanded?

Is this message bar in an error state or warning state?

How many pages are you paginated in?

How far is the user scrolled down the page?

Front-end developers have been dealing with that kind of state for a long time, but it’s exactly this kind of state that has gotten us into trouble before. A modal dialog can be open with a simple modifier class like <div class="modal is-open"> and toggling that class is easy enough with .classList.toggle(".is-open"); But that’s a purely visual treatment. How does anything else on the page know if that modal is open or not? Does it ask the DOM? In a lot of jQuery-style apps of yore, yes, it would. In a sense, the DOM became the “source of truth” for our websites. There were all sorts of problems that stemmed from this architecture, ranging from a simple naming change destroying functionality in weirdly insidious ways, to hard-to-reason-about application logic making bug fixing a difficult proposition.

Front-end developers collectively thought: what if we dealt with state in a more considered way? State management, as a concept, became a thing. JavaScript frameworks themselves built the concept right in, and third-party libraries have paved and continue to pave the way. This is another example of expanding responsibility. Who architects state management? Who enforces it and implements it? It’s not some other role, it’s front-end developers.

There is expanding responsibility in the checklist of things to do, but there is also work to be done in piecing it all together. How much of this state can be handled at the individual component level and how much needs to be higher level? How much of this data can be gotten at the individual component level and how much should be percolated from above? Design itself comes into play. How much of the styling of this component should be scoped to itself, and how much should come from more global styles?

It’s no wonder that design systems have taken off in recent years. We’re building components anyway, so thinking of them systemically is a natural fit.

Let’s look at our design again:

A bunch of new thoughts can begin!

Assuming we’re using a JavaScript framework, which one? Why?

Can we statically render this site, even if we’re building with a JavaScript framework? Or server-side render it?

Where are those recipes coming from? Can we get a GraphQL API going so we can ask for whatever we need, whenever we need it?

Maybe we should pick a CMS that has an API that will facilitate the kind of front-end building we want to do. Perhaps a headless CMS?

What are we doing for routing? Is the framework we chose opinionated or unopinionated about stuff like this?

What are the components we need? A Card, Icon, SearchForm, SiteMenu, Img… can we scaffold these out? Should we start with some kind of design framework on top of the base framework?

What’s the client state we might need? Current search term, current tab, hamburger open or not, at least.

Is there a login system for this site or not? Are logged in users shown anything different?

Is there are third-party componentry we can leverage here?

Maybe we can find one of those fancy image components that does blur-up loading and lazy loading and all that.

Those are all things that are in the domain of front-end developers these days, on top of everything that we already need to do. Executing the design, semantics, accessibility, performance… that’s all still there. You still need to be proficient in HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and how the browser works. Being a front-end developer requires a haystack of skills that grows and grows. It’s the natural outcome of the web getting bigger. More people use the web and internet access grows. The economy around the web grows. The capability of browsers grows. The expectations of what is possible on the web grows. There isn’t a lot shrinking going on around here.

We’ve already reached the point where most front-end developers don’t know the whole haystack of responsibilities. There are lots of developers still doing well for themselves being rather design-focused and excelling at creative and well-implemented HTML and CSS, even as job posts looking for that dwindle.

There are systems-focused developers and even entire agencies that specialize in helping other companies build and implement design systems. There are data-focused developers that feel most at home making the data flow throughout a website and getting hot and heavy with business logic. While all of those people might have “front-end developer” on their business card, their responsibilities and even expectations of their work might be quite different. It’s all good, we’ll find ways to talk about all this in time.

In fact, how we talk about building websites has changed a lot in the last decade. Some of my early introduction to web development was through WordPress. WordPress needs a web server to run, is written in PHP, and stores it’s data in a MySQL database. As much as WordPress has evolved, all that is still exactly the same. We talk about that “stack” with an acronym: LAMP, or Linux, Apache, MySQL and PHP. Note that literally everything in the entire stack consists of back-end technologies. As a front-end developer, nothing about LAMP is relevant to me.

But other stacks have come along since then. A popular stack was MEAN (Mongo, Express, Angular and Node). Notice how we’re starting to inch our way toward more front-end technologies? Angular is a JavaScript framework, so as this stack gained popularity, so too did talking about the front-end as an important part of the stack. Node and Express are both JavaScript as well, albeit the server-side variant.

The existence of Node is a huge part of this story. Node isn’t JavaScript-like, it’s quite literally JavaScript. It makes a front-end developer already skilled in JavaScript able to do server-side work without too much of a stretch.

“Serverless” is a much more modern tech buzzword, and what it’s largely talking about is running small bits of code on cloud servers. Most often, those small bits of code are in Node, and written by JavaScript developers. These days, a JavaScript-focused front-end developer might be writing their own serverless functions and essentially being their own back-end developer. They’ll think of themselves as full-stack developers, and they’ll be right.

Shawn Wang coined a term for a new stack this year: STAR or Design System, TypeScript, Apollo, and React. This is incredible to me, not just because I kind of like that stack, but because it’s a way of talking about the stack powering a website that is entirely front-end technologies. Quite a shift.

I apologize if I’ve made you feel a little anxious reading this. If you feel like you’re behind in understanding all this stuff, you aren’t alone.

In fact, I don’t think I’ve talked to a single developer who told me they felt entirely comfortable with the entire world of building websites. Everybody has weak spots or entire areas where they just don’t know the first dang thing. You not only can specialize, but specializing is a pretty good idea, and I think you will end up specializing to some degree whether you plan to or not. If you have the good fortune to plan, pick things that you like. You’ll do just fine.

The only constant in life is change.

– Heraclitus – Motivational Poster – Chris Coyier

¹ I’m a white dude, so that helps a bunch, too. ↩️ ² Browsers speak a bunch more languages. HTTP, SVG, PNG… The more you know the more you can put to work! ↩️ ³ It’s an interesting bit of irony that WordPress websites generally aren’t built with client-side JavaScript components. ↩️

The post How to Think Like a Front-End Developer appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

You can support CSS-Tricks by being an MVP Supporter.

How to Think Like a Front-End Developer published first on https://deskbysnafu.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

The Widening Responsibility for Front-End Developers

This is an extended version of my essay “When front-end means full-stack” which was published in the wonderful Increment magazine put out by Stripe. It’s also something of an evolution of a couple other of my essays, “The Great Divide” and “Ooops, I guess we’re full-stack developers now.”

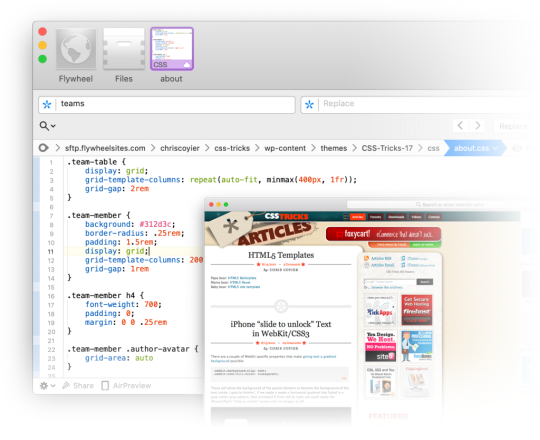

The moment I fell in love with front-end development was when I discovered the style.css file in WordPress themes. That’s where all the magic was (is!) to me. I could (can!) change a handful of lines in there and totally change the look and feel of a website. It’s an incredible game to play.

Back when I was cowboy-coding over FTP. Although I definitely wasn’t using CSS grid!

By fiddling with HTML and CSS, I can change the way you feel about a bit of writing. I can make you feel more comfortable about buying tickets to an event. I can increase the chances you share something with your friends.

That was well before anybody paid me money to be a front-end developer, but even then I felt the intoxicating mix of stimuli that the job offers. Front-end development is this expressive art form, but often constrained by things like the need to directly communicate messaging and accomplish business goals.

Front-end development is at the intersection of art and logic. A cross of business and expression. Both left and right brain. A cocktail of design and nerdery.

I love it.

Looking back at the courses I chose from middle school through college, I bounced back and forth between computer-focused classes and art-focused classes, so I suppose it’s no surprise I found a way to do both as a career.

The term “Front-End Developer” is fairly well-defined and understood. For one, it’s a job title. I’ll bet some of you literally have business cards that say it on there, or some variation like: “Front-End Designer,” “UX Developer,” or “UI Engineer.” The debate around what those mean isn’t particularly interesting to me. I find that the roles are so varied from job-to-job and company-to-company that job titles will never be enough to describe things. Getting this job is more about demonstrating you know what you’re doing more than anything else¹.

Chris Coyier Front-End Developer

The title variations are just nuance. The bigger picture is that as long as the job is building websites, front-enders are focused on the browser. Quite literally:

front-end = browsers

back-end = servers

Even as the job has changed over the decades, that distinction still largely holds.

As “browser people,” there are certain truths that come along for the ride. One is that there is a whole landscape of different browsers and, despite the best efforts of standards bodies, they still behave somewhat differently. Just today, as I write, I dealt with a bug where a date string I had from an API was in a format such that Firefox threw an error when I tried to use the .toISOString() JavaScript API on it, but was fine in Chrome. That’s just life as a front-end developer. That’s the job.

Even across that landscape of browsers, just on desktop computers, there is variance in how users use that browser. How big do they have the window open? Do they have dark mode activated on their operating system? How’s the color gamut on that monitor? What is the pixel density? How’s the bandwidth situation? Do they use a keyboard and mouse? One or the other? Neither? All those same questions apply to mobile devices too, where there is an equally if not more complicated browser landscape. And just wait until you take a hard look at HTML emails.

That’s a lot of unknowns, and the answers to developing for that unknown landscape is firmly in the hands of front-end developers.

Into the unknoooooowwwn. – Elsa

The most important aspect of the job? The people that use these browsers. That’s why we’re building things at all. These are the people I’m trying to impress with my mad CSS skills. These are the people I’m trying to get to buy my widget. Who all my business charts hinge upon. Who’s reaction can sway my emotions like yarn in the breeze. These users, who we put on a pedestal for good reason, have a much wider landscape than the browsers do. They speak different languages. They want different things. They are trying to solve different problems. They have different physical abilities. They have different levels of urgency. Again, helping them is firmly in the hands of front-end developers. There is very little in between the characters we type into our text editors and the users for whom we wish to serve.

Being a front-end developer puts us on the front lines between the thing we’re building and the people we’re building it for, and that’s a place some of us really enjoy being.

That’s some weighty stuff, isn’t it? I haven’t even mentioned React yet.

The “we care about the users” thing might feel a little precious. I’d think in a high functioning company, everyone would care about the users, from the CEO on down. It’s different, though. When we code a <button>, we’re quite literally putting a button into a browser window that users directly interact with. When we adjust a color, we’re adjusting exactly what our sighted users see when they see our work.

That’s not far off from a ceramic artist pulling a handle out of clay for a coffee cup. It’s applying craftsmanship to a digital experience. While a back-end developer might care deeply about the users of a site, they are, as Monica Dinculescu once told me in a conversation about this, “outsourcing that responsibility.”

We established that front-end developers are browser people. The job is making things work well in browsers. So we need to understand the languages browsers speak, namely: HTML, CSS, and JavaScript². And that’s not just me being some old school fundamentalist; it’s through a few decades of everyday front-end development work that knowing those base languages is vital to us doing a good job. Even when we don’t work directly with them (HTML might come from a template in another language, CSS might be produced from a preprocessor, JavaScript might be mostly written in the parlance of a framework), what goes the browser is ultimately HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, so that’s where debugging largely takes place and the ability of the browser is put to work.

CSS will always be my favorite and HTML feels like it needs the most love — but JavaScript is the one we really need to examine The last decade has seen JavaScript blossom from a language used for a handful of interactive effects to the predominant language used across the entire stack of web design and development. It’s possible to work on websites and writing nothing but JavaScript. A real sea change.

JavaScript is all-powerful in the browser. In a sense, it supersedes HTML and CSS, as there is nothing either of those languages can do that JavaScript cannot. HTML is parsed by the browser and turned into the DOM, which JavaScript can also entirely create and manipulate. CSS has its own model, the CSSOM, that applies styles to elements in the DOM, which JavaScript can also create and manipulate.

This isn’t quite fair though. HTML is the very first file that browsers parse before they do the rest of the work needed to build the site. That firstness is unique to HTML and a vital part of making websites fast.

In fact, if the HTML was the only file to come across the network, that should be enough to deliver the basic information and functionality of a site.

That philosophy is called Progressive Enhancement. I’m a fan, myself, but I don’t always adhere to it perfectly. For example, a <form> can be entirely functional in HTML, when it’s action attribute points to a URL where the form can be processed. Progressive Enhancement would have us build it that way. Then, when JavaScript executes, it takes over the submission and has the form submit via Ajax instead, which might be a nicer experience as the page won’t have to refresh. I like that. Taken further, any <button> outside a form is entirely useless without JavaScript, so in the spirit of Progressive Enhancement, I should wait until JavaScript executes to even put that button on the page at all (or at least reveal it). That’s the kind of thing where even those of us with the best intentions might not always toe the line perfectly. Just put the button in, Sam. Nobody is gonna die.

JavaScript’s all-powerfulness makes it an appealing target for those of us doing work on the web — particularly as JavaScript as a language has evolved to become even more powerful and ergonomic, and the frameworks that are built in JavaScript become even more-so. Back in 2015, it was already so clear that JavaScript was experiencing incredible growth in usage, Matt Mullenweg, the founding developer of WordPress, gave the developer world homework: “Learn JavaScript Deeply”³. He couldn’t have been more right. Half a decade later, JavaScript has done a good job of taking over front-end development. Particularly if you look at front-end development jobs.

While the web almanac might show us that only 5% of the top-zillion sites use React compared to 85% including jQuery, those numbers are nearly flipped when looking around at front-end development job requirements.

I’m sure there are fancy economic reasons for all that, but jobs are as important and personal as it gets for people, so it very much matters.

So we’re browser people in a sea of JavaScript building things for people. If we take a look at the job at a practical day-to-day tasks level, it’s a bit like this:

Translate designs into code

Think in terms of responsive design, allowing us to design and build across the landscape of devices

Build systemically. Construct components and patterns, not one-offs.

Apply semantics to content

Consider accessibility

Worry about the performance of the site. Optimize everything. Reduce, reuse, recycle.

Just that first bullet point feels like a college degree to me. Taken together, all of those points certainly do.

This whole list is a bit abstract though, so let’s apply it to something we can look at. What if this website was our current project?

Our brains and fingers go wild!

Let’s build the layout with CSS grid.

What fonts are those? Do we need to load them in their entirety or can we subset them? What happens as they load in? This layout feels like it will really suffer from font-shifting jank.

There are some repeated patterns here. We should probably make a card design pattern. Every website needs a good card pattern.

That’s a gorgeous color scheme. Are the colors mathematically related? Should we make variables to represent them individually or can we just alter a single hue as needed? Are we going to use custom properties in our CSS? Colors are just colors though, we might not need the cascading power of them just for this. Should we just use Sass variables? Are we going to use a CSS preprocessor at all?

The source order is tricky here. We need to order things so that they make sense for a screen reader user. We should have a meeting about what the expected order of content should be, even if we’re visually moving things around a bit with CSS grid.

The photographs here are beautifully shot. But some of them match the background color of the site… can we get away with alpha-transparent PNGs here? Those are always so big. Can any next-gen formats help us? Or should we try to match the background of a JPG with the background of the site seamlessly. Who’s writing the alt text for these?

There are some icons in use here. Inline SVG, right? Certainly SVG of some kind, not icon fonts, right? Should we build a whole icon system? I guess it depends on how we’re gonna be building this thing more broadly. Do we have a build system at all?

What’s the whole front-end plan here? Can I code this thing in vanilla HTML, CSS, and JavaScript? Well, I know I can, but what are the team expectations? Client expectations? Does it need to be a React thing because it’s part of some ecosystem of stuff that is already React? Or Vue or Svelte or whatever? Is there a CMS involved?

I’m glad the designer thought of not just the “desktop” and “mobile” sizes but also tackled an in-between size. Those are always awkward. There is no interactivity information here though. What should we do when that search field is focused? What gets revealed when that hamburger is tapped? Are we doing page-level transitions here?

I could go on and on. That’s how front-end developers think, at least in my experience and in talking with my peers.

A lot of those things have been our jobs forever though. We’ve been asking and answering these questions on every website we’ve built for as long as we’ve been doing it. There are different challenges on each site, which is great and keeps this job fun, but there is a lot of repetition too.

Allow me to get around to the title of this article.

While we’ve been doing a lot of this stuff for ages, there is a whole pile of new stuff we’re starting to be expected to do, particularly if we’re talking about building the site with a modern JavaScript framework. All the modern frameworks, as much as they like to disagree about things, agree about one big thing: everything is a component. You nest and piece together components as needed. Even native JavaScript moves toward its own model of Web Components.

I like it, this idea of components. It allows you and your team to build the abstractions that make the most sense to you and what you are building.

Your Card component does all the stuff your card needs to do. Your Form component does forms how your website needs to do forms. But it’s a new concept to old developers like me. Components in JavaScript have taken hold in a way that components on the server-side never did. I’ve worked on many a WordPress website where the best I did was break templates into somewhat arbitrary include() statements. I’ve worked on Ruby on Rails sites with partials that take a handful of local variables. Those are useful for building re-usable parts, but they are a far cry from the robust component models that JavaScript frameworks offer us today.

All this custom component creation makes me a site-level architect in a way that I didn’t use to be. Here’s an example. Of course I have a Button component. Of course I have an Icon component. I’ll use them in my Card component. My Card component lives in a Grid component that lays them out and paginates them. The whole page is actually built from components. The Header component has a SearchBar component and a UserMenu component. The Sidebar component has a Navigation component and an Ad component. The whole page is just a special combination of components, which is probably based on the URL, assuming I’m all-in on building our front-end with JavaScript. So now I’m dealing with URLs myself, and I’m essentially the architect of the entire site. [Sweats profusely]

Like I told ya, a whole pile of new responsibility.

Components that are in charge of displaying content are almost certainly not hard-coded with data in them. They are built to be templates. They are built to accept data and construct themselves based on that data. In the olden days, when we were doing this kind of templating, the data has probably already arrived on the page we’re working on. In a JavaScript-powered app, it’s more likely that that data is fetched by JavaScript. Perhaps I’ll fetch it when the component renders. In a stack I’m working with right now, the front end is in React, the API is in GraphQL and we use Apollo Client to work with data. We use a special “hook” in the React components to run the queries to fetch the data we need, and another special hook when we need to change that data. Guess who does that work? Is it some other kind of developer that specializes in this data layer work? No, it’s become the domain of the front-end developer.

Speaking of data, there is all this other data that a website often has to deal with that doesn’t come from a database or API. It’s data that is really only relevant to the website at this moment in time.

Which tab is active right now?

Is this modal dialog open or closed?

Which bar of this accordion is expanded?

Is this message bar in an error state or warning state?

How many pages are you paginated in?

How far is the user scrolled down the page?

Front-end developers have been dealing with that kind of state for a long time, but it’s exactly this kind of state that has gotten us into trouble before. A modal dialog can be open with a simple modifier class like <div class="modal is-open"> and toggling that class is easy enough with .classList.toggle(".is-open"); But that’s a purely visual treatment. How does anything else on the page know if that modal is open or not? Does it ask the DOM? In a lot of jQuery-style apps of yore, yes, it would. In a sense, the DOM became the “source of truth” for our websites. There were all sorts of problems that stemmed from this architecture, ranging from a simple naming change destroying functionality in weirdly insidious ways, to hard-to-reason-about application logic making bug fixing a difficult proposition.

Front-end developers collectively thought: what if we dealt with state in a more considered way? State management, as a concept, became a thing. JavaScript frameworks themselves built the concept right in, and third-party libraries have paved and continue to pave the way. This is another example of expanding responsibility. Who architects state management? Who enforces it and implements it? It’s not some other role, it’s front-end developers.

There is expanding responsibility in the checklist of things to do, but there is also work to be done in piecing it all together. How much of this state can be handled at the individual component level and how much needs to be higher level? How much of this data can be gotten at the individual component level and how much should be percolated from above? Design itself comes into play. How much of the styling of this component should be scoped to itself, and how much should come from more global styles?

It’s no wonder that design systems have taken off in recent years. We’re building components anyway, so thinking of them systemically is a natural fit.

Let’s look at our design again:

A bunch of new thoughts can begin!

Assuming we’re using a JavaScript framework, which one? Why?

Can we statically render this site, even if we’re building with a JavaScript framework? Or server-side render it?

Where are those recipes coming from? Can we get a GraphQL API going so we can ask for whatever we need, whenever we need it?

Maybe we should pick a CMS that has an API that will facilitate the kind of front-end building we want to do. Perhaps a headless CMS?

What are we doing for routing? Is the framework we chose opinionated or unopinionated about stuff like this?

What are the components we need? A Card, Icon, SearchForm, SiteMenu, Img… can we scaffold these out? Should we start with some kind of design framework on top of the base framework?

What’s the client state we might need? Current search term, current tab, hamburger open or not, at least.

Is there a login system for this site or not? Are logged in users shown anything different?

Is there are third-party componentry we can leverage here?

Maybe we can find one of those fancy image components that does blur-up loading and lazy loading and all that.

Those are all things that are in the domain of front-end developers these days, on top of everything that we already need to do. Executing the design, semantics, accessibility, performance… that’s all still there. You still need to be proficient in HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and how the browser works. Being a front-end developer requires a haystack of skills that grows and grows. It’s the natural outcome of the web getting bigger. More people use the web and internet access grows. The economy around the web grows. The capability of browsers grows. The expectations of what is possible on the web grows. There isn’t a lot shrinking going on around here.

We’ve already reached the point where most front-end developers don’t know the whole haystack of responsibilities. There are lots of developers still doing well for themselves being rather design-focused and excelling at creative and well-implemented HTML and CSS, even as job posts looking for that dwindle.

There are systems-focused developers and even entire agencies that specialize in helping other companies build and implement design systems. There are data-focused developers that feel most at home making the data flow throughout a website and getting hot and heavy with business logic. While all of those people might have “front-end developer” on their business card, their responsibilities and even expectations of their work might be quite different. It’s all good, we’ll find ways to talk about all this in time.

In fact, how we talk about building websites has changed a lot in the last decade. Some of my early introduction to web development was through WordPress. WordPress needs a web server to run, is written in PHP, and stores it’s data in a MySQL database. As much as WordPress has evolved, all that is still exactly the same. We talk about that “stack” with an acronym: LAMP, or Linux, Apache, MySQL and PHP. Note that literally everything in the entire stack consists of back-end technologies. As a front-end developer, nothing about LAMP is relevant to me.

But other stacks have come along since then. A popular stack was MEAN (Mongo, Express, Angular and Node). Notice how we’re starting to inch our way toward more front-end technologies? Angular is a JavaScript framework, so as this stack gained popularity, so too did talking about the front-end as an important part of the stack. Node and Express are both JavaScript as well, albeit the server-side variant.

The existence of Node is a huge part of this story. Node isn’t JavaScript-like, it’s quite literally JavaScript. It makes a front-end developer already skilled in JavaScript able to do server-side work without too much of a stretch.

“Serverless” is a much more modern tech buzzword, and what it’s largely talking about is running small bits of code on cloud servers. Most often, those small bits of code are in Node, and written by JavaScript developers. These days, a JavaScript-focused front-end developer might be writing their own serverless functions and essentially being their own back-end developer. They’ll think of themselves as full-stack developers, and they’ll be right.

Shawn Wang coined a term for a new stack this year: STAR or Design System, TypeScript, Apollo, and React. This is incredible to me, not just because I kind of like that stack, but because it’s a way of talking about the stack powering a website that is entirely front-end technologies. Quite a shift.

I apologize if I’ve made you feel a little anxious reading this. If you feel like you’re behind in understanding all this stuff, you aren’t alone.

In fact, I don’t think I’ve talked to a single developer who told me they felt entirely comfortable with the entire world of building websites. Everybody has weak spots or entire areas where they just don’t know the first dang thing. You not only can specialize, but specializing is a pretty good idea, and I think you will end up specializing to some degree whether you plan to or not. If you have the good fortune to plan, pick things that you like. You’ll do just fine.

The only constant in life is change.

– Heraclitus – Motivational Poster – Chris Coyier

¹ I’m a white dude, so that helps a bunch, too. ↩️ ² Browsers speak a bunch more languages. HTTP, SVG, PNG… The more you know the more you can put to work! ↩️ ³ It’s an interesting bit of irony that WordPress websites generally aren’t built with client-side JavaScript components. ↩️

The post The Widening Responsibility for Front-End Developers appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

You can support CSS-Tricks by being an MVP Supporter.

😉SiliconWebX | 🌐CSS-Tricks

0 notes

Text

Transcript of The Talk Show Episode 4

Title: James Duncan Davidson & Digital Photography

Hosts: John Gruber, Dan Benjamin

Special guest: James Duncan Davidson

Release date: 28 July 2007

Description: Special guest James Duncan Davidson joins us to talk about digital photography. JDD is a pro, and shares his experience as a professional photographer for WWDC and O’Reilly.

Dan Benjamin: So where are you right now, Duncan, what conference are you at this week?

James Duncan Davidson: I’m actually at two conferences simultaneously. Today, tomorrow, and the next day is the Ubuntu Live conference. And then, starting tomorrow and going for the rest of the week is the Open Source Convention.

Benjamin: And you’re covering these, you’re photographing them?

Davidson: Yeah, I’m shooting them both.

Benjamin: That’s what we’re here to talk about. Last week, John and I said we gotta get you on here.

Davidson: Oh, I know, and I heard that actually. I was listening to the podcast while I was riding the MAX, and I think I was going over the bridge right about that point, and it was a very freaky feeling to be volunteered to do something while you’re listening to yourself on public transit. But I’m down with it, it’s pretty cool.

John Gruber: For those of you who don’t know, we’re talking to James Duncan Davidson. James Duncan Davidson is right now primarily — is that your primary source of income, you’re a conference photographer? I mean, most of your time is spent on photography now.

Davidson: Yeah, this year will be the first year it’s crossed the 50 percent line.

Gruber: But your background is very, very varied, and you’ve done everything from Java to Ruby on Rails, a lot of programming stuff. You’ve written books on Cocoa programming.

Davidson: Yep.

Gruber: So you go to these tech conferences, but you could easily not just be attending them, you could be and in the past have actually spoken at them.

Davidson: Oh yeah, yeah.

Benjamin: You spoke at Rails conference last year, right?

Davidson: Yeah, and they actually wanted me to speak this year, but I didn’t think I could actually do the job of shooting, and the conference, and get the talk ready. And even more tricky, photographing myself speaking, I thought that might be a little hard.

Benjamin: With all those strobes flashing all over the place, that’s a full-time job just setting those up.

Davidson: The conferences really have turned into — I mean, when I’m at a conference, it’s more than a full-time job. Like today, you’re catching me, it all worked out where I can find a break, but it’s going to be a 14-hour day. But it’s precisely because I spoke at tech conferences for so long that O’Reilly first picked me up to do the photography. They had the theory, and I agreed with them at the time and still do, that since I knew most of the people in this environment and knew what was going on, I probably would have a decent enough eye for understanding what would be important to take pictures of and what wouldn’t be at a tech conference. And that’s how the professional photography career got started.

Benjamin: As far as actually learning to be a photographer, you don’t just show up at a conference and start taking pictures, and now all of a sudden O’Reilly is hiring you to shoot everything. It can’t work like that.

Davidson: No, no, I’ve been shooting pictures since I was six or seven years old. My grandmother taught me how, and I’ve been shooting ever since.

Benjamin: You don’t have any formal training or educational background in photography though?

Davidson: No. All my formal training was in architecture actually. So, lots of design work, but no specific classes in photography, just lots and lots of experience.

Benjamin: So you said you grandmother taught you, Duncan, what did you start — because when I was a little kid, maybe this is how you started, when I was a little kid, we took a little — I guess it was some construction paper, and we folded it up into a little box, we painted it black, and then you took a little pinhole, and you just poke a pinhole and this little piece of tinfoil — and I understand now it’s aluminum foil — which was taped to a cut-out piece in the front of a thing, and there was like a little flap, and you would open up the flap, and just on the back of this thing you had one of those — you remember the old style 35 mm or whatever, the little pocket cameras that you would give to kids that had the little plastic U-shaped film thing that would fit into the back of the camera.

Davidson: The 110 cassettes, yeah.

Benjamin: Exactly. And you would crank that with a quarter, and then you would open the front of the thing, count to three, and then close it, and your picture would come out. That’s actually still how I photograph today.

Davidson: For some people, that would be the purest expression of photography because you’re directly manipulating aperture and shutter and everything right there. But no, I didn’t learn with a pinhole camera. You actually have a better background than I do then.

Benjamin: Well, my whole experience pretty much ends there though.

Davidson: [laughs] My grandmother shot 35 mm film on Leicas and I quickly picked up a — I had my own little 110 camera, I had one of those disc cameras. You remember those?

Benjamin: Oh yeah, that was really — if you had one of those — wow.

Gruber: Yeah, they were crazy cool because they were such an odd form factor because they were, like, up vertical. They were so thin in terms of front to back.

Benjamin: Yeah. They had these teeny-tiny lenses on them because they had such a small negative.

Gruber: And they took such crap pictures.

Davidson: They did.

Benjamin: [laughs]

Gruber: I should —

Benjamin: What — oh, go ahead, John. That’s John Gruber, by the way.

Gruber: I was just going to mention, for everybody who doesn’t know, you’re listening to The Talk Show. I’m John Gruber. I’m here hosting the show with my friend Dan Benjamin. We have some sponsors to thank this week, I would like to thank them, that’s why this show is here. And first up, I’d like to mention 37signals.

Benjamin: Can you believe that? How did we get them?

Gruber: They’re sponsoring The Talk Show. They have a bunch of great web apps, they do great software. The one that I want to talk about is Ta-da Lists. You guys use Ta-da Lists? It’s sort of like the list feature from Basecamp, broken out into its own little app. It’s free, you just go there, you make like a to-do list. And the reason — I never used it, I checked it out, I used it, it’s pretty good. But all of a sudden now I use it every day because what they did — and it wouldn’t an episode of The Talk Show if we didn’t bring up iPhone. They have an iPhone-optimized version of Ta-da List. You go to tadalist.com, you sign up, you get your own username. So I have one, I share it with my wife, we do all of our shopping lists on Ta-da Lists now. You get the regular Ta-da List interface when you go to it in Safari or Firefox, your regular web browser on your computer, so we can share shopping lists. We just do one for each store we go to. Then I go to the store, take out my iPhone, go there, and I get an iPhone-optimized view of the website. It’s not a little thing I have to pinch down in Safari, it’s just perfect. Every time I buy something, you just tap it, click “done”, it’s off the list, and I never — I’m the most absent-minded person in the world. We live about two blocks from a Whole Foods here in Philadelphia. I will leave the house and my wife can say, “Don’t forget to buy soy milk.” And I will say, “Okay.” And I will go there and I will see, oh, look, a new kind of chips! And I’ll buy these chips, come home, and she’ll be like, “Where is the soy milk?” And I’ll be like, “Oh.” And she’s like, “That’s the whole reason you went.” Never happens anymore. So, Ta-da Lists from 37signals.

Benjamin: Saved the marriage, it sounds like.

Gruber: No, it just saved me extra trips back to the grocery store.

Davidson: So it saved you frustration.

Gruber: And it also makes me feel like my iPhone is useful.

Benjamin: That justifies the purchase, I think.

Gruber: Oh, absolutely.

Davidson: Of course.