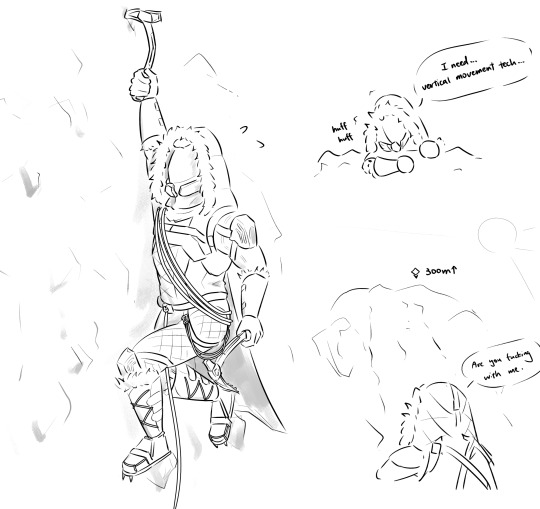

#i have no idea how ice / alpine climbing works

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

yay hunter climbing

#i have no idea how ice / alpine climbing works#i've never even seen snow irl before#i just wanna draw my hunter do something different#anyway i like this set a bit too much#i have zero resistence to fluffy clothes#destiny 2#destiny hunter#destiny 2 art#my art

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chasing Baker

My Nana was my greatest adversary.

In an otherwise charmed life, Nana was an immovable force and the only legitimate challenger to my willpower. Not without the warmth one would expect from a grandmother, Nana could be sharp - like a sun-warmed pane of glass. Lesser hearts might have bent to me when I requested accommodation - but not Nana. Nana set a firm bedtime, insisted on efficient tooth brushing, and rather than negotiate with hair tangles, made short work of them in single, swift wrenches when brushing your hair. No nonsense. When you stayed with her - in one of two twin beds in a room made precisely for grandchildren - you often found yourself in bed with the lights out, with no real memory of having gotten there, swept away in the tide of your sheets. Nana was uncompromising, and no arena was more suited to our mutual stubbornness as the dinner table.

I grew up a notoriously picky eater. After a weekend at my Uncle Jerry's, my mom received a hardcover copy of "The Strong-Willed Child" from him as a gift. He had spanked me for not eating chicken nuggets. As evident by its title, the book was meant to coach my mother on parenting strategies for mitigating my innate obstinance. This would not be the only copy of the book my mother received. Though, I think she could have written one by the time I turned 4. I simply refused to eat the things I didn't like, and that was a long list.

A relative once applauded - clapped his hands together in joy- upon learning that I had graduated from having the crusts cut off my bread to full-blown sandwich eating. The peanut butter and honey sandwich was my signature dish and an absolute staple. I'd like to say I've grown out of it - and I've certainly grown having tried llama steak in Peru, lamb heart at the table of a Lebanese family, and Greenland shark in an Icelandic cafe - but it took me a long time to let go of my habits and permit myself to try, and it took some coaxing. My preferences ran deep.

My diet from ages six through eleven included Eggo waffles, peanut butter and honey sandwiches, an assortment of cereals, a handful of specific fruits and vegetables, and the occasional steak when mom thought my iron was low. My mom - on the advice of a pediatrician who told her that if she force-fed me, I'd develop an eating disorder - catered to this preference. Nana did not. They must have been seeing different pediatricians.

Nana took the clear your plate approach - The approach driven by reward and consequence. Finish your plate, cookies delivered. Fail to try, become hungry and hungrier still as dessert passes you by. I took to swallowing food whole, and my mom took to sending me with granola bars on visitations. She'd line the interior of my suitcase like we were smuggling drugs. I'll admit it was an unusual form of contraband, but the measure seemed necessary in a divorced child's duplicitous world. What my mom saw as nourishment, my Dad might see as undermined parenting strategy even under the best of circumstances - which they often weren't. I was hungry, so decided it best to keep things a secret and wrappers out of the trash.

Despite Nana's apparent best efforts, I avoided the eating disorder. Thanks to my mom, I avoided most foods until my early 20s. I don't know who was right. What I know for certain is that I was loved.

When I sat down with Nana after my trip to Mt. Baker, she clutched her heart as she said. "Ally - to think about you as this little girl - and that you would only eat peanut butter and honey sandwiches - to think of you climbing mountains…" she shakes her head, "… well I just can't believe it."

I started to laugh and asked her, "Want to know the best part?"

She nodded, smile in her eyes, full of that sunny warmth - playful and kaleidoscopic.

"I ate peanut butter and honey sandwiches up and down the side of that mountain, Nana," I told her, laughing, and then we laughed together. Growing up is fun, I thought, especially in moments like this.

Laughing with your grandmother is a gift you receive in exchange for time, and it is a beautiful gift indeed. Here is a woman who bathed you, clothed you, fed you - and by the time you're old enough to understand the magnitude of the life she held before all that, she is often gone. I'm lucky to have this time. Nana is 90 years old now, and my mother's mother passed at 74. I never got to have the conversations I wanted to have with my grandmother, who died. To ask her questions like, 'Who were you?' 'What lifetimes made up the love you gave so effortlessly away?'

There is something about mountain climbing that makes you consider those kinds of questions in real-time. There is something about mountain climbing that makes you feel as if you are in the process of 'becoming.' So when, at the parking lot of Grandy Creek Grocery, I met my fellow climbers and our guides - there was a feeling of anticipation and nervousness about who I'd be sharing that story with. Dropping me off, my mom described it like the first day of kindergarten. The first person I met was Sharon.

I had been worried about Sharon. Weeks before, on the pre-trip Zoom call, she stood out from the digital crowd as the most visibly senior person there. Sharon did not look old - she looked undoubtedly the oldest. I think this is an important distinction - particularly to Sharon. I remember thinking - "I hope she is not on my trip because I'm worried she will show me down." A very judgmental thought and the universe saw to its reckoning. Sharon surprised the hell out of me.

She paced the parking lot, and I jumped out of my rig to greet her. We quickly began commiserating. Baker would be her first mountain. I had Mount St. Helens under my belt, but it's not much in the way of experience. We talked about our training plan, recounting long drives to taller places. Sharon was from Wisconsin, and she had to drive 45 minutes to get to peaks at 3,000 - the same as me in Eastern Washington. We had a lot in common. Where I ran, she had been hiking with weight and jogging. Sharon wasn't afraid of hard work. On our drive to the trailhead, I learned that she had just lost 75 pounds last year. I learned later that when Sharon signed up for this climb, she hadn't told anyone in her family she was doing it. She was 62 years old and had never once traveled alone. What on earth possessed her to climb a mountain? I'd be afraid of that question, too.

Sharon eventually fessed up to her family and made the trip official. That's how we found ourselves on the side of a mountain together. I'm embarrassed to have been so fundamentally wrong - but my confession is not without meaning, and I learned an important lesson. Never underestimate a Sharon.

When Melissa, our guide, described Mt. Baker for the first time, she called it by its indigenous name, Komo Kulshan. She then gave us its epithet - "The Great White Watcher." Having now met Kulshan face to face, I can tell you that's precisely how he feels. The summit looms as you navigate through the trees. Stoic in the face of the wilderness that surrounds him. Ice cold, he waits. In the Lummi language, he's called 'white sentinel.' He is persistent, vigilant, and watching.

I focused my nervous energy on preparing to meet this mountain by learning what I could about him. I learned that Mt. Baker is 10,781 feet tall, an active volcano, and the second most glaciated mountain in the continental united states (Rainier's got it beat, and you don't count Alaska). It's a formidable mountain, known - as nearly all alpine environments are - for its quickly changing conditions and the perils of its geology. This all, somehow, frightened me less than the thought of meeting Melissa Arnot-Reid. Her legend loomed not in the Cascades - where only a single peak resides above the threshold of 14,000 feet by which the Rockies measure their formidable "fourteeners." Melissa's legend loomed as large as Everest, on who's summit she has been six times - the only American woman to summit without the use of supplemental oxygen and survive. 29,032 feet. Melissa was someone I wanted to learn from, and I was scared shitless of her by reputation.

Suffering a bit of social awkwardness around celebrities, I prepared to meet Melissa by seeking to learn nothing about her at all. The antithesis of my mountain strategy - I told myself our experience would be what it was when we met on the mountain. My job was to learn - to ask my questions courageously - and be vulnerable and bold in seeking truth. I spent a fair bit of time wondering if she might be an ass hole, too. The age-old adage, "don't meet your heroes," drifted in and out of my mind.

In the last 15 minutes of our drive to Grandy's, my mom started reading Melissa's Wikipedia page aloud to me as I navigated the road, undoing months of my concerted preparation. I let her continue, greedy for information. "It says she trains by depriving herself of things - that she'll go without food and water."

"Probably a good idea if you're ever going to be stuck on the side of a mountain without it," I told her. I braced myself for a response. In the past few months, my mother had a growing sensitivity around topics that might suggest I could die on the side of a mountain. Admitting, so blatantly, that mountain climbing was a dangerous sport left me vulnerable to excessive mothering accompanied by exclamations of "Don't you dare!" Instead, my mom sort of nodded and continued, "I'm surprised her baby came out healthy."

My brow furrowed. I hated my mother for saying it. I had avoided a lecture from the mother of the mountaineer but failed to account for the mother of the daughter aged-almost-thirty. My uterus is a topic of conversation around my mother's table. Apparently, so was Melissas. Not wanting to discuss either, I let my mother's comment go unchecked as she continued to list accomplishments. "This article says she's focused on business, not emotions. That she is an incredible problem-solver." Now her reports felt more like cheating - it felt like an unfair advantage to meet someone armed with publicly available information about them. When you Google "Allyson Tanzer," you won't find much about my disposition under pressure. I told my mom it was time to focus and turned up the music.

When we parked, and I went to introduce myself to Melissa, three things happened. As I introduced myself, she first quickly let me know that she would not be giving out hugs due to the pandemic. Then, taking my hand in a firm grip, Melissa detailed that she and our other guide, Adrienne, had critical guide business to discuss and would be with us in a moment. She reported being thrilled to be meeting us as she quickly dropped my hand. Within thirty seconds, I was apologizing profusely and backing my way into the grocery. What can I say - first time formally climbing mountains, and I wasn't sure of the protocol. I fiddled with a bag of Cheetohs and continued to hope that she wasn't just an ass hole.

I went to the bathroom for something to do and remembered what my mother said. Task-oriented. I figured Melissa probably didn't hate me, after all. Despite my earlier misgivings, I was grateful to know a bit about her character, regardless of how 'honestly' that information was obtained. Thanks, Mom.

Our climb began. We left Grandy's in a caravan and parked near 3000' at the winter routes trailhead. On the first day, you ascend to 6000' and establish camp. You carry about 40 pounds, walking 1 mile and about 1000 vertical feet per hour, stopping for 15-minute breaks in those intervals. Conditions are warm, which means you're doing something the mountaineers call "post-holing" - ramming deep holes (as if for a fence post) into the ground as you step through snow that's washed out underneath. It's slow-going and rigorous. An hour and a half in, Melissa reports that we're standing in the location where she usually takes the first break. Unseasonably warm weather with a heavy snow accumulation has made for an exciting start.

You walk along a canyon ridge formed by a retreating glacier. You realize that time here is not measured in the same cadence that it's known to you. Mountains measure time in millennium, not decades. The formations of rock are carved by years, not minutes. The ground holds a history you can't conceive of - an ancient history of rock and ice. You are constantly struck by feeling small both physically and in your very chronology. I spent the first day happily in awe.

At camp, you maintain - guides (and playfully designated junior guides), boil snow, establish a base, dig a toilet. You assess whether or not you need to poop in a bag and carry it down the mountain with you as you try - for the first time - a rehydrated meal claiming to be chili Mac and cheese. Melissa teaches us how to walk on rope over a glacier. I try to mimic her knots. She redefines your concept of efficiency - breathlessly describing a packing order that accounts for calorie intake, warmth requirements and weight distribution - Every contingency considered. When I win the Ice Ax Rodeo by landing my thrown ax in a particular configuration - all is right in the world. Melissa is a drill sergeant giving instruction. She outlines the next minute - next five minutes - next hour - next day.

Her matter-of-fact nature reminds me of something. When I gave my parents a ride in an airplane for the first time with me as the pilot in command, I provided them near the same briefing as we were parked on the ramp. It ended dramatically with, "And if anything should happen, you have to exit the aircraft first in the following fashion." At which point I launched myself from the plane. I wanted them to be prepared to fight their instincts to protect me. I’m the only pilot on board - and my job is to protect my passengers, no exceptions. They both described a sense of foreboding and peace at the demonstration. It’s precisely how I felt when Melissa explained how she would be rescuing herself from a crevasse. “If you fall, I get you out. If I fall, I get myself out, but I need your help as an anchor to do so.” She took the approach of coaching us in only what we needed for the next challenge. We would learn crevasse rescue on a need to know basis. At Grandy’s, she told us to expect 48 hours of endurance. At camp, we’re at hour 9. She painted a picture of the following day.

"We'll begin between 11, and 2 am. Expect switchbacks up the glacier, a series of flats, and gains over the next hour. In 3.5 miles, we'll gain an additional 2000 feet - meandering a path through the glacier's crevasses, and it will gradually become steeper over time. About 1.5 miles to the summit, we'll hit the Easton glacier culminating in the Roman Wall. Then, because God has a sense of humor, you have a long flat walk to the summit after the steepest portion. All said it will take us between 5-7 hours to the top."

Frankly, it was just about as simple as that.

My eyes opened at 11:50 pm to the sound of movement outside the tent. Melissa had coached us here, too. "You may not be sleeping," she told us as we readied for 'lights out.' Days from the summer solstice, the sun burned brightly above us at 7 pm. "Remember that you don't need sleep; you need rest. That's what you're getting here at camp. You're horizontal; your feet are out of your boots. Close your eyes, and know you're getting what you need." Felt like a lie, but sure enough, with two hours of sleep, I couldn't describe myself as tired.

I did, however, feel cold. Chilly night temperatures had crept into our tent, and dressing for the day was arduous. I knew to keep my clothes in my sleeping bag. It was a trick I learned from a friend made trekking in the Andes for dressing in the cold. I knew to shorten my trekking poles while climbing, thanks to my guide on that same trek. I'd be leaving my trekking poles behind today, though. Ice axes only. We divide into rope teams. The race begins, but there's no starting pistol - only wind.

Fifteen minutes into our climb and we're struggling to find the rhythm. I'm still shaking the bleariness of the cold. The rope between climbers takes on an interesting dynamic. While it connects you to your fellow climber, it also isolates you from them. You have to maintain a certain distance away from one another while maintaining the same pace. It's a dance with crampons on in glacial ice - a delicate dance indeed - and it's where climbing feels like a team sport. You're all in it together.

Voices rang out in sequence like a game of telephone - one of our team would need to climb down. We said short goodbyes and waited as Adrienne (guide) descended with climber to camp. We were lucky - we hadn’t been climbing long which meant Adrienne could climb down and back to rejoin her rope. Guide redundancy is a safety net when groups of climbers work together.

Darkness continued. We continued. As you persist, darkness seems to persist along with you. In the first hour, it grows heavy. Your world begins and ends at the light of your headlamp, and that's where you find it—your rhythm. Crampons crunching, breath steady, and the gentle swish of your layers create a sort of timpani, a medley of percussion sounds. Clink, brush, crunch, and clink, brush, crunch, as ax bites ice, the movement of your clothes, and the toe of your boot kicks crampon into snow propelling you forward. There isn't much to think about in this grinding meditation. You're grounded in tugs from ahead or behind you as you march, slowly up. You can count steps, miles, feet of elevation - whatever keeps you moving. Whatever keeps you going up.

Moments before sunrise, we would lose another on our team. I listened to Melissa coach her. "What we're headed to is going to be harder than what we've just done. If how you are feeling is taking away from your ability to focus on your next step - I can only tell you that it's not going to get easier from here." That's when I saw the decision on her face. Another round of goodbyes - this one a bit more somber. She had worked so hard.

The decision to descend is a difficult one, but it’s one of the most important you can make. There are steep consequences to being in over your head in a place so remote. The summit is a siren, beware. Melissa - aware of the remaining teams intention to summit - advised us to plug our ears as she told the descending climber the Sherpa belief that a mountain won't let you summit for the first time if it likes you. Mountains bring you back. Further, she coached, the decision to go down can lift an entire team's chance of success if you feel you're a liability. Recognizing yourself and your limitations truthfully is a mountain in itself. That's the summit this person made in her decision to descend.

Like a good Agatha Christie novel, our list of characters dwindled. We added layers and continued - five of the original eight. Melissa was right, again. After we lost the second climber, our ascent became a proper climb. From that point forward, if anyone decided to turn around - we would all have to. There was only one remaining guide, and she had to protect all her climbers, no exceptions - me in the cockpit all over again.

She didn't show it, but 62-year-old Sharon was genuinely frightened. She had realized the same thing I did. If she didn't make it - no one would. Sharon kept climbing. Remember when I was worried she would slow me down?

When the sun starts to rise, everything begins to feel possible again. I don't mean to say that things were hopeless, just that with the sun comes energy and a sense of renewal. Color returns to the landscape, and you can begin to be able to measure your progress concretely. The mountain casts a shadow across the earth, stretching miles. You can't believe that you are contained within that shadow, on the face of such a giant who stands so impossibly tall. Melissa stood there, and I took her picture.

She had turned out to be not an ass hole at all. Where I sought to be her student, she aspired to teach - at once brilliant and kind. Her stride - her sport - a work of art. The precise art of what she calls slow, uphill walking. Her shadow and the shadow of the mountain impressed upon me the power of legends.

As the Roman Wall came into view - I knew we had it. We short rope in and make one last push. If Mt. Baker is a joke from God, the ending of the Roman Wall is its punchline.

Atop the incline awaits a long, easy walk to a haystack peak some few hundred yards in the distance. I was bubbling with emotion as my heart rate settled and the view became clear. There wasn't much difference between where we stood and where we were going. We dropped our packs, unroped, and ran up the summit. I was in tears.

Melissa broke her no-hugs-in-the-pandemic rule and celebrated us each in turn. I snapped countless photos and spent each frozen moment smiling. I pulled Melissa and Sharon in close. I had felt something on my heart and only needed a moment's bravery to share it.

I started awkwardly.

"I'd like to say something to you and Sharon," I muttered, barely audible over the wind, as I tugged on Melissa's sleeve. I grabbed Sharon's arm and pulled her in too. I don't remember the exact thing I said or the exact way in which I said it. I remember pausing to make sure I got it right and wondering for a long time if I managed to do so.

I told them that I had come to the mountain expecting to be impressed by one person. Melissa promised an impressive education - on which she delivered. She is of that rare quality - the kind who’s presence improves you. I came to Baker with that expectation, I confessed, I expected Melissa. I paused before telling Sharon, her gloved hand in mine, “You?” I laughed nervously. “I wasn’t expecting. A 62-year-old woman….” I nodded back to Melissa, “And you, the mother of a 3-year-old…” I didn’t want to get this wrong. “You are two people who our society labels and confines. Yet, here you are - on top of a mountain. I have to tell you….” I was choked up in earnest here and struggled to continue.

"It matters.” I said. “What you do matters. It matters to have an example of what is possible. Both of you have provided that example to me and women like me. Thank you." I sobbed. "I am so grateful for it and grateful for you." Melissa smothered me in her jacket as she embraced me, once again, in a hug. Pandemic be damned. My tears froze. While I expected a "There's no crying in mountaineering" a la Tom Hanks in A League of Their Own (it was a climb of mostly women, after all) the admonishment never came.

Sharon grabbed hold of me next and we shared the alpine view. Before I knew it, we were the last two on the summit. The wind howled a steady cheer. Celebrations concluded, it was time to leave. I stayed for just a moment longer, watching Sharon as she left. They don't make anything more beautiful than a mountain, and it's a view worth savoring. I descended, joyfully, to my team.

I didn't bury Jake up there. In Ashes to Ashes, I told the story of taking my old farm dog's remains to the top of my first volcano. He's not so much a good luck charm as he is an omen of protection. I don't need luck as much as I need safety, and he serves his duty well. Jake stayed with me through our descent to camp. I needed a little protection coming down off the Roman Wall, I thought. I wanted him close until we were off the glacier. He lays now at the foot of my tent—a very good place for a very good dog.

There's a natural mindfulness to climbing. I often find myself living in the present step - not thinking about the route that lies below. You forget in moments that the trip up is accompanied by an equally long and perilous journey down. From the summit, your journey is far from over. Yet, time flies by even as you stop to admire the steam vents. The rainbow that surrounds the sun refracts joy and color the same.

You reach camp, celebrate, pack up. Miles and thousands of feet remain even from there. That's when you realize it's ending and when I realized I didn't want it to end.

We spent the next few miles getting to know each other in earnest, savoring time and mountain views, chatting in the way of long-form hikers - about the nature of things and through storytelling. Melissa regaled us with vulnerable truths and comedic parables. We laughed. I kept sipping at the wells of knowledge around me, drinking in the moments. Laughter distracted from hunger, from wet feet, and from the dull and dim realization that all good things must come to an end. We made our way to the bottom of the mountain. Just like that - we say goodbye.

Sharon drove me back to Grandy's. We chitter like school girls - adrenaline and nostalgia collide in our post-climb delirium. We talk about the future. I realize that we are good friends. I am humbled by just how wrong a person can be to believe something about someone for no good reason.

Mom picks me up, and with her embrace my adventure is over. I’ve come full circle - safe and sound, parked in the lot of Grandy Creek Grocery.

Melissa found us there and knocked on our window.

"Your daughter is really special. The MOST special,” my hero and friend told my mom. Mom beamed with a special pride reserved exclusively for mothers of strong-willed daughters. I had been misreading things - the adventure had only just begun.

There are eight years between Melissa and I. I’m not sure I’ll be chasing Everest in that time, but I know I won’t be finished. I’ve got thirty-three years to catch Sharon at 62. In the mountain blink of sixty-one years, I’ll be as old as my Nana and I hope at least half as wise. Good thing there are so many years - for there is so much left to climb.

#mountaineering#mountains#travel#adventure#adventurephotography#traveling#travelblogpost#mountainclimbing#mt baker

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unexpected.

Summary: You decided to cook a last-minute Christmas dinner for yourself when something unexpected happens on your way back home.

Characters: Bucky Barnes x Reader, Alpine.

Warnings: Some angst (blink and you’ll miss), just general FLUFF.

A/N: It’s been so long since I wrote any Bucky x Reader stories, so I hope you enjoy it! As usual, English is not my first language so be kind with the grammar mistakes. I would also love to know your thoughts on it!

Read it on AO3.

Snow covers the streets of Shelbyville as you try hard not to slip and fall.

Christmas isn't your favorite holiday, but seeing your neighbors decorating their homes, baking cookies and buying Christmas presents was making your heartache.

After the death of your parents and a terrible fight with your only aunt, you decided to start over away from everything you used to know. You were a single child and nothing was holding you back anymore. And what better place to start over than Shelbyville, Indiana?

The town was like any other small town in the country, but something about the place and the people made you want to stay and, five months later, you still don’t regret your decision.

The only decision you’re regretting at the moment is leaving your house in one of the coldest days of the year for a last-minute Christmas dinner shopping for yourself.

The supermarket was so crowded and people were so rude that you considered if hell would be like that when you died. But, hey, at least you got everything you need for a nice Christmas dinner for one! You knew that there was too much food for just one person and that it would last you at least until the New Year's Eve, but looking on the bright side, you wouldn’t have to go back to that place for a while.

And you bought some of the things that you loved and that reminded you of Christmas with your parents: chocolate, supplies to bake one of your mother’s favorite pies, a small turkey that would last you for a week, wine and even some cans of cat food for the white cat that liked to visit you sometimes.

You had no idea who she belongs to or where she lived, you just knew it was a female. One day, a few weeks after you moved in she was just sitting there on your couch, staring at you with curious, bright eyes. Her white fur was clean and she looked well-fed, so you assumed she had an owner, but she liked to visit you and slowly, you started to like her and wait for her visits.

And that was the funny thing about the cat - you’ve decided to call her Mimi - she was only visiting you and would appear at the most random times. She would usually show up at night, mostly the cold nights, and sleep a bit with you. By the time you wake up, she would be gone.

You wonder if she would show up tonight to expend Christmas Eve with you as you slowly walk back home, trying hard not to fall as you step onto the sidewalk when you see him.

His once black clothes are white from the snow, so you assume he must have fallen and you have no idea how he’s not freezing to death with the weather. His hair is also covered in snow and he’s making exasperated sings for something on the roof.

Bucky Barnes.

Everyone knew who he was, of course. Former Captain America sidekick and war hero, former Winter Soldier, former Avenger. He lived in his childhood home now, right across the street from you and mostly kept to himself.

You had heard rumors when you moved in, about him being your new neighbor, but had no idea what to expect. Maybe daily fights with bad guys? Random former Avengers stopping by? Was he friends with Thor? But none of that ever happened and your curiosity started to peak.

“Hey”, you call, surprising yourself, “Is everything okay?”

Bucky looks around at you, surprised.

“Oh… Hey”, he says slowly and looks back at the roof, “It’s nothing… Just Alpine playing a little Christmas game”.

He points to a white thing on the roof and you gasp.

“Mimi?! What the hell is she doing up there?”

“Mimi?”, Bucky repeats with a surprised tone.

“Yeah…” you feel yourself getting flustered with the way he looks at you, “she, hm, she visits me sometimes…”

“So that’s where you’re going?” Bucky asks the cat, now sitting at the roof, watching the conversation between the two of you with interest.

“I didn’t know she was yours”, you explain with a shrug. “She comes by sometimes and sleeps in my bed”.

Bucky laughs and your heart beats a little faster.

“I’m sorry, she disappears sometimes but I never really wondered where she could be”.

“It’s okay! I adore her, she’s adorable!”

There’s an awkward silence and you look at Mimi - Alpine - sitting on the roof. How is she not freezing too?

“How did she end up there?”, you ask not wanting the conversation to end.

Bucky sighs.

“I have no idea. I heard her meowing and tried to get her back down, but she just keeps going up and looking at me with that judgmental look of hers”.

You smile.

“Ah, the judgmental look. She usually gives me that look when I leave my bedroom window closed”.

“Yeah, sounds like Alpine”, he laughs.

You stare at each other, then at Alpine again. The cat meows and moves swiftly a little higher.

Slowly, you cross the street and approaches Bucky. He gives you a curious look.

“I’m guessing you tried to climb up there and bring her back?”

“Yeah…”, he indicates his snow-covered clothes, “but, obviously it didn’t work”.

“Okay… Maybe she’ll come down if I ask?” you question and turn in the direction of the house, moving your hands and calling Alpine.

You’re completely aware of Bucky looking at you as you make weird gestures and cat noises to try and bring the cat down, but don’t stop. Alpine lays in the snow-covered rooftop and stares at the both of you.

“I think she’s enjoying our humiliation”, you sigh.

“Guess she was bored and wanted to play with us a little”, Bucky replied and when you look at him, he quickly looks back at his cat.

“Okay… I have a stupid idea, but maybe it will work?” you shrug and walk back to the shopping bags on the sidewalk across the street.

Bucky watches with brows furrowed as you look around and pick a can of cat food.

“I don’t think she’s hungry…” he starts as you walk back.

“Hey! Alpine!” you exclaim and raises the can of food around in the air.

The cats raise her head and meow with curiosity.

“C'mon Alpine, stop playing games with our hearts and come down”, you continue to move the can around and the cat walks down the roof, and jumps back to the ground.

Bucky laughs incredulously and you smile, watching as the cat walks around his legs and stops in front of you, as if waiting for you to give her the food.

“Do you have any cats?”, Bucky asks, picking up Alpine and holding her in his arms.

“Nope”, you reply shily, “bought this for her. Christmas dinner”.

“Thank you. That’s really kind of you”.

Alpine moves around in his arms and jumps on your shoulder, making you both laugh.

“Would you like to share her custody for the holiday?”, Bucky suggests as his bright blue eyes look from you to his cat, trying to lay on your shoulder like you were the best of friends.

“Um… I mean” you mumble, scratching the cat’s head, “if it doesn’t bother you…”

“I think Alpine already made her choice”, his voice is light and the shadows of a smile played around his lips.

“That’s very nice of you, thank you”.

You both fall into a comfortable silence as you play with the cat on your shoulders.

“And, what about you? Do you have any plans for Christmas?” you ask, remembering the ridiculous amount of food you bought an hour ago.

“No… I don’t really like Christmas anymore. To be honest, I was planning to stay in, eat pizza and watch horror movies to avoid the general mood”.

You laugh, surprised.

“Been there, done that. I’m not a big fan of Christmas either. I was planning on binge-watching Lucifer to avoid the mood too”.

“Sounds like a good plan”.

“Yeah… But Christmas food is my favorite, so I decided to cook dinner last minute”, you stared at him, feeling yourself getting warm with the way he’s looking at you. “Would you like to come over?”

The way his cheeks turn pink with the invitation makes your heart beat faster.

“I can’t… I don’t mean to intrude!”

“You’re not intruding at all! I bought so much food that will probably last until the New Year, so there’s more than enough for both of us”, you give him a small smile, “Besides the holidays can be depressing enough without some good food or company and…”, you shrug, “Nobody should be alone for Christmas”.

You stared at each other as you wait for his reply. You can almost see the engines in his brain, considering the invitation.

As if on cue, Alpine jumps from your shoulder, crosses the street and sits next to your shopping bags making you both laugh.

“You are unbelievable”, Bucky sighs at the cat.

“So… Would you like to come in?”, you ask and Bucky smiles. You really love the way he smiles.

“Yeah, sure doll. Thank you”.

You cross the street together, careful not to slip on the ice and he picks up your shopping bags. Alpine follows and is the first to walk in when you open the door, so familiarized with your home that it’s almost like her own.

You watch as she jumps on the couch and lay down in one of your pillows, hoping that maybe, Bucky will feel just as comfortable with you too.

#bucky barnes#bucky barnes x reader#bucky barnes x you#winter soldier#alpine#reader insert#captain america fanfic#ficmas#kinda#just cuteness#fluff#christmas fic#christmas#textos#my writing

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arafef: kisses in the snow

The chilly December wind blew through the alpine forest, as giant footsteps crunched through the snow. The 156 foot tall redblood smiled gently as she cradled her seadweller matesprite Feferi in her palm.

Feferi: Aradia im glubbing FR-EEZING!!!! Why did you want to go on a date in the middle of now)(ere 38T!

Aradia: don’t you think it's gorgeous out here? the ice covered trees, the snow in your hair?

Feferi: It’s absolutely beautiful glub, but my fins are turning into icicles!!!

Aradia: hmmm... do you think some kisses would warm you up 0u0 ?

Feferi: Yes, I t)(ink that would do just the trick! 38D

Aradia slowly moved her palm up to her face, careful not to jostle her tiny lover. With Aradia's palm flush with her lips, Feferi ran forward to embrace them, as Aradia's fingers cupped around her to protect her from falling. Feferi realized that Aradia's lips were unbelievably soft as she pressed her face and hands into them. It felt like falling into a warm, freshly made bed after a long day out in the cold, and laying your head on an incredibly plush pillow. Aradia puckered her lips around Feferi's head for an even more intense kiss. Feferi's cheeks were flushed with fuchsia as she buried her face deeper between aradia's lips. As Feferi was savoring her kiss from Aradia, Aradia accidentally ended up savoring Feferi. She carelessly allowed her tongue to pass between her lips, unintentionally giving Feferi's face a small lick.

Feferi: )(e)(e, look out Aradia, you got my face all covered in saliva! 38P

Under normal kissing circumstances, getting some small tongue kisses might be expected, but things are very different when that tongue is roughly the size of a bus. Still, Feferi seemed to take it in stride, and the way she chuckled and smiled made aradia suspect that she enjoyed it. Despite this Aradia was careful to not let her tongue slip again, despite the fact that she really wanted to. As much as she didnt want to admit it to herself, Fef tasted absolutely delicious. We all know the typical 4 flavors foods come in- salty, sour, sweet, and bitter. But Feferi was best described by a flavor often forgotten, umami- the flavor of mushrooms, tomatoes, and seafood. Umami detecting tastebuds cover a larger section of the tongue than all other flavors combined, making umami one of the most powerful flavors as a result. With Aradia introduced to Feferi's delicious umami flavor she couldn't help but crave another taste of her small matesprite. Her mouth flooded with saliva as her mind flooded with thoughts of getting another lick. However, Aradia feared indulging her cravings could frighten her girlfriend. She held herself back, though her cheeks still flushed as deep red as her feelings for Feferi. After Feferi enjoyed her giant kiss a bit longer she pulled back, sat down on Aradia's massive palm, and gave her a big smile. Aradia smiled back, and the two silently communicated their love for each other as they gazed into each other's eyes. The red blooded giantess began strolling through the snow once again, leaving footprints the size of a small house behind her. Aradia gently cupped Feferi to her chest in a loving embrace. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ As Aradia strolled through the alpine landscape, she desperately tried to push the thought of how delectable Feferi was out of her head. Deep down, aradia was terrified of scaring her lover. Even though being god tier meant she could swallow Feferi and cough her up later without causing her any harm, Aradia knew she would never forgive herself if she frightened Feferi. When Aradia first met her other friends in person in SGRUB all those years ago, and they discovered the secret of her size, many of them became afraid of her, even if they tried not to show it. Aradia could recount by memory every night she stayed up crying after that, fearing that her friends thought that she was a monster. Until the fateful night on the meteor that feferi found her sobbing in her room. The sound of Aradia's cries had apparently traveled through the vents of the meteor and reached Feferi's ears. Feferi had consoled Aradia, showed her that she wasn't afraid of her, that she didn't think she was a monster! The friendship between Aradia and Feferi deepened over those three years on the meteor and blossomed into a matespriteship. When they finally arrived on Earth-c they promised each other they would spend the rest of their lives together, but Aradia often feared that she would make a careless mistake and Feferi would think she was a monster just like Aradia thought all the others did.

Aradia held Feferi a little closer to her chest as these thoughts passed through her head. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ After roughly 30 minutes of walking through the winter landscape Feferi called out to Aradia.

Feferi: Aradia, i'm cold again!! 38I

Aradia: how? I've been holding you to my chest for the past half hour!

Feferi: Ok, i'll admit, it's warm. But I want WARMER, glub!

Aradia: would some more kisses interest you?

Feferi: T)(at sounds nice...

Feferi: But I think i )(ave a better idea, glub!

Aradia Awaited Feferi's idea but only received a plethora of eyebrow wiggles. She stared at fef for a few minutes confused until fef opened her mouth and pointed in. The eyebrow wiggles intensified.

Aradia: uh.. wha..i..um

Feferi: Oh come on, don't bother playing coy, i know you liked it when you got a taste of me earlier, and )(onestly who could blame you? 38P

Aradia's heart was pounding out of her chest, and yet she really didn't know why. Feferi had just told her that WANTED to indulge her craving, but Aradia still felt scared and embarrassed.

Feferi: Aradia, I know already. You've been jittery and blus)(ing constantly since you got that lick! Also, giving you a better taste would double as a nice way to keep warm and cozy!

Aradia: i...i.. alright

Aradia: you caught me, you taste delicious and i've been craving another taste since when I gave you kisses earlier.

Aradia: i... was just really afraid of scaring you.

Feferi: Aradia! you don't have to worry about stuff like that! Were both god tier and you know i am afraid of glubing NOT)(ing!!!

Aradia: i know, .. i just get so nervous.

Feferi: Aradia, i will always trust you, there is no reason to be nervous!!

Aradia:.. thank you, that.. that means a lot to me.

Aradia: alright, are you sure about this?

Feferi: YEA)(!!!!

Aradia brought her palm up to her lips once again, and opened wide. Feferi stood before her lovers gargantuan maw, as fearless as ever. Aradia slowly outstretched her tongue, giving Feferi a massive lick in the process. As saliva coated fef's face she laughed and gave Aradia a gleeful smile.

Truth be told, fef was enjoying this just as much as Aradia. Earlier that day when Aradia had licked her on accident Fef had realized how soft and warm Aradia's tongue was, and wondered what it would be like inside her mouth. She was absolutely loving this.

Aradia lowered her tongue onto her palm to allow Feferi to climb on. The tiny seadweller stepped onto her lovers outstretched tongue and laid down on it, sinking into the warm grey muscle. Feferi gently massaged Aradia's tongue as she rested her head onto it.

Aradia was in heaven.

She gently pulled her tongue back into her mouth, curling it up a bit to cradle feferi.

For Feferi, if getting those kisses earlier was like falling into bed, being pulled into Aradia's mouth was like climbing under the deliciously cozy sheets. The tongue was so plush and warm, saliva soaked her entire body, and Aradia's throat slowly pulsed as her warm breath swept through her mouth. With feferi entirely inside her mouth, Aradia closed her teeth together with a click, sealing Fef in the darkness of the expansive maw. But Feferi's seadweller eyes allowed her to see perfectly in the dark.

Aradia began to gently slosh Feferi around inside her mouth, savoring her delicious umami flavor. Occasionally Fef would give her tongue a massage and it was one of the best feelings in the world.

Inside the mouth Feferi was extremely relaxed despite being slohed around and tasted. It was like a full body massage, working out all the tension within her muscles. After a while the sloshing stopped and Aradia opened her mouth, a gust of cold winter air mingled with her warm, steamy breath.

Aradia: are you ready to be swallowed?

Feferi: Go a)(ead!

Aradia clicked her mouth closed once again, and Feferi shuffled around and dangled her legs into Aradia's throat, her head brushing against the uvula. Aradia's tongue rose up like a massive wave, pushing fef deeper into the throat. Aradia gulped a few times until fef slipped fully into her throat and the muscles of her escoughgas began to pull her down. The giantess traced the bulge Fef made on the way down with her finger.

Inside Aradia’s esophagus, the seadweller received an even more intense massage as she descended deeper into Aradia's body. After a while she arrived at the sphincter which opened to drop her into the stomach.

To Fef, Aradia's stomach was like a massive aquarium. Due to the conjunction of her unique biology and being godteir, Aradia's stomach contained only warm water. Feferi swam around playfully, jumping in and out of the water like a dolphin before getting tired and drifting off to sleep in the back float position.

With Feferi safe inside her stomach Aradia sat down on a nearby rock ledge and patted her stomach. She could feel Feferi playfully swimming around inside her. Aradia closed her eyes and fell asleep, satiated with the knowledge that Feferi would always love and trust her.

#vorestuck#homestuckvore#safevore#softvore#willingvore#arafef#aradiamegido#feferiipiexes#homestuck#romnoms#aradia/feferi#MyArt

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trekking pole manufacturer/supplier

Millet mountaineering bag measured experience, a century-old outdoor brand

Today I will unpack this Millet PEUT INT 35+10 outdoor hiking bag.

Let’s talk about this outdoor brand! Millet was originally a canvas bag company. It sprouted in Lyon, France in 1921. Since the company moved to the foot of the Alps in 1928, it began to produce professional mountaineering backpacks in the 1930s. The two sons also inherited the family business and further cooperated with mountain guides to jointly develop higher-level and professional mountaineering backpacks.

Millet products are divided into six series, namely, Alpinism-Professional Mountaineering/Climbing, Climbing-Rock Climbing, Trekking Hiking-Hiking, Mountain lifestyle-Leisure Life, Ski-Skiing, TRAIL-Wild Running. And this backpack out of the box today is designed for year-round mountaineering. In addition to basic mountaineering settings, a lot of thoughtful designs for ice climbing or skiing are added to the details of the backpack. Let's take a look!

35+10 liters of flexible large capacity

I like this kind of backpack with elastic capacity the most, because storage is really hard work, especially in the mountains, it is inconvenient to pack, and some items that are light and need easy access (such as raincoats, down jackets, mobile food) sometimes I'm really too lazy to organize it. With flexible capacity, I just throw it all in.

The design of the bag is exquisitely equipped with a harness configuration at 35 liters and an additional 10 liters. With or without the 10 liters, the equipment can be compressed into a fixed shape. Although it seems to be a small design, it is not in use. It is very intimate and can feel the fineness.

In addition, there is another setting that has to be praised, see the picture below.

(The middle picture is taken from Millet's official website)

Because it is designed for year-round climbing and climbing, a rope storage system is specially installed inside the top bag, which solves the inconvenience of rope storage at one go; at the same time, even if there is no ice climbing requirement, this buckle can be used as The secondary compression, or the perfect fixation of any equipment that needs to be fastened here (the Hanchor CINDER 18L top bag is shown on the right above), really greatly improves the storage performance of this bag!

Straight bag type

I didn't pay special attention to the shape of the bag before. Anyway, it is normal to occasionally hook on branches and get stuck on the path. But when I came back to do my homework, I found out: this bag is too thin!

The above picture is not obvious, please see the official website product photo below.

Maybe it’s because of the women’s backpack. It is also narrower in the shape of the backpack to match the shoulder width. The advantage is that when drilling some narrow mountain roads, it is not easy to get stuck on nearby branches or affect activities. Recall that when I was drilling before, I would be hitting everything. This time it seemed to be really unimpeded.

Since the backpack is a bucket type, a double-end zipper is opened on the side of the backpack to improve the convenience of picking up items. You need to make a small hole where you want to take the equipment, and you are not afraid that it will all fall out once you open it. (Later after thinking about it, I found out that it was this way that I used a double-end zipper, so sweet~)

Comfortable carrying system and super breathable back panel

Let's talk about the most important carrying system.

Because my favorite bag is the adjustable back length Mystery Ranch, this bag without a back length adjustment system may make people a little uncomfortable, but in fact, as long as the weight is fixed in a labor-saving position on the body, the carrying is very comfortable of.

At the beginning, I adjusted the elasticity of the strap with the tightness that Mysterious Farm is used to. After more than an hour of departure, I started to have waist and back pain. Later, on the suggestion of a friend, I tightened the belt and pinched my waist (more than when I was carrying Mystery Farm. Tight), so that the waist belt can be locked and fixed to the hip joint, and it will be improved immediately, and there is no back pain at all during the whole trip, which is very powerful in the carrying system!

Although many people admire Mystery Farm’s excellent carrying and user-friendly adjustment system, the empty weight of the backpack is indeed quite heavy. The choice of backpack still depends on the different needs and physical conditions of each person. This time I use Millet to find fun. PEUT INT, it is indeed obvious that the weight on the body has been reduced a lot, and when the backpack is back on the body, it is not as difficult as before. It is a very comfortable carrying experience.

Chest buckle with elastic rope track and adjustable position.

Millet's secret weapon is super breathable back panel!

then! What I want to introduce is the breathable backboard that I feel very good this time.

As a Virgo with a lot of sweat and a bit of cleanliness, at first a large part of the mountain climbing is not able to adapt to the sweat, wet and sticky, and can not take a bath. Every time the backpack upper body will obviously feel a whole piece of sweat on the back, It's terrible. But this bag won't!

Millet's Ariaprène Back technology, I don’t know how to translate it. In short, it looks like it’s hollowed out a whole piece of foam in a special form, so that the back panel foam can take into account comfort and breathability at the same time. The triangle doesn't look much, but it's a peach blossom on the back! Before starting to use, I did a little homework on this backpack, and I noticed the ventilation system on the back. I didn’t think much about it at the beginning, but it was really super comfortable to use. It was sunny and sweaty for three days and two nights. , When I go home and smell the backboard, it is still fragrant (I just smelled it again, um, it is still fragrant), this ventilation system I give a super high evaluation!

Magic large space, large top pocket and storage space

Do you like to keep holding things when climbing a mountain?

Can you take a trekking pole for me, can you take a fur hat for me, in the side pocket, wait a moment, I want to wear a coat, I am hungry, I want to eat... That’s right, it’s that annoying, but I’m lazy to take off the backpack , It’s the kind that when you’re shopping on the street and want to take things, you will reach out to the back to dig out your backpack for a long time, and you will always want to take things. How can you get it in the main bag?

This top bag is basically a big space, super three-dimensional square compartment, no problem to put a bunch of things, if you want to, you should be able to put a total of nine uniform big pudding in three rows, plus a raincoat in it. My own storage habit is to put all the rainproof equipment in the top pocket, which is the most convenient to take, and is not afraid of getting the equipment wet. Also, because the shape of the compartment is almost a cuboid, the shape of the top pocket still won’t run after stuffing so many things. It will even make it look better.

Top pocket, top pocket inner layer, side pockets, large main pocket, thick storage deep pocket on the front side, and water bag hanging ring.

In addition to the top pocket, other storage spaces are also worth mentioning. Excluding the oversized top pocket, there is also a small zipper pocket on the inner layer of the top pocket, which can hold some smaller items; the front side is a thick and deep pocket for ice climbing to place crampons, which is very high and stiff enough. You can also put some small flat objects without crampons; the inside of the bag has a water bag fixing ring configuration, which is quite intimate.

Infinitely possible plug-in settings everywhere

Did you discover it? His external ring is invincible!

As a professional camel beast, one of the bad storage habits is to love plug-ins. Some hiking bags don’t pay much attention to the external system (after all, I’m not happy to see crazy external systems, haha). Although they can be placed in the main backpack of the backpack, they don’t need external ones. (Such as camping lights, stereos, slippers, hats) hanging outside is a kind of hardcore game, handsome~ Then there are really a bunch of loops on the outside of this backpack for me to hang out, satisfying my little vanity.

(Do you know why I can’t resist the modular system of Mystery Ranch 2 Day Assault)

Did you find that even the top pocket has four loops? Because of those four loops, Zhi Jiayang can put the tent on top of the top pocket

Not only the webbing loop, but also because of the needs of ice climbing, there are additional straps, ice axe straps (trekking poles can also be used) and storage compartments. Take a look at the picture below. If it really looks like the right one... . It's too hardcore! ! !

Use experience sharing

It’s almost here when I open the box. Overall, I’m very satisfied with the use. Although some of the features are spoiled by the love bag: adjustable back length, three-way full-opening zipper, and many internal interlayers, which make it uncomfortable at the beginning. However, after these two uses, I can get started slowly, and PEUT also has some comforts that the love bag cannot provide (such as breathability, light weight and large capacity), and the carrying system is indeed no less than the love bag. In fact, after weighing it down, the longer reloading trip should still choose to take PEUT up the mountain.

The most obvious experience of this experience is probably the intimateness of the backpack design. In many cases, I have made thoughtful ideas for the inconvenience and discomfort of mountaineering. It is worthy of a century-old mountaineering equipment brand. There are many ingenuity in product design and delicate attention. Accompany us through every mountain.

Because I have not experienced too many mountaineering bags, I have only used Decathlon, Mystery Ranch 2 Day Assault and this Millet PEUT INT 35+10, plus the positioning of each bag is different, so there are not many here. Make a comparison~ I like it and recommend it!

The above experience is all sincerely shared and recommended. Although the speech is a bit exaggerated, it is really good to memorize it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

SLOVENIA

Slovenia 5/12/19 – 5/19/19 Republika Slovenija. The country is about the size of New Jersey but ever since I first visited in 2006, it left a big impression on me and I have always wanted to return. And especially with a bicycle. After a trip to Norway didn’t pan out I had committed myself to the idea of another bicycle trip and after a short think, Slovenia was it. Quite a bit of flight itinerary option analysis later, I had a free flight via American Airlines miles to Venice. I had about a month to plan out the trip so wasn’t too stressed. Then work got crazy, then I ended up in LA for the week before the trip, and then all of a sudden I was leaving the next day and I still had a route to plan and accommodations to book. That all somehow comes together no matter how unprepared I am and it would this time as well. So a long flight to Madrid, a short flight to Venice, and a 2 hour train ride later I was at the border town of Gorizia, Italy where I had the day before booked a hotel for the start and end of the trip. The hotel room turned into a bike shop and I re-assembled the Rick Jones that night and would leave the travel case with the hotel for the week. The following morning I pedaled across the border to Nova Gorica in Slovenia and started on my clockwise loop around western Slovenia.

The first day was grey and a little wet, which would prove to be a theme for the trip, but the riding started out pretty good, riding over one Italian hill before unknowingly crossing the official border at some unmarked spot and onto a bunch of small Slovenian farm roads.

Just before the town of Plave I hit a ripper of a descent and satisfied myself with my brakes ability to stop me, and then the Soca River first came into view. I had been waiting to see this river for 13 years, and it did not disappoint with amazingly clear turquoise blue water.

My route for the day would follow small roads along the Soca River valley, hitting small towns, and transitioning between perfect pavement, gravel, and jeep track. The weather shifted from threatening to very threatening but luckily never rained more than a spitting. But what the weather lacked in rain it made up for in gusting wind, and blowing the wrong direction. I stopped for a picnic of leftover pizza from the night before, and though I was exhausted from the travels and jetlag, and despite the wind, made it to the town of Bovec to check in to the friendly hostel I booked. A good meal of trout, in the somewhat humorous and cartoonish Bovec style, and a couple glasses of local wine and I was out like a light.

The next morning my body still wanted to wake up on NY time so I got a late start but when I got intel on the route I had planned I found out my intended one-way foray up to the Mangart Saddle was not going to be possible as the road was closed because of snow. I thought about trying it out anyway, but it is a one way road 30 miles out and back, with 5000’ of climbing, and I’d have to return right back to where I started in order to continue on the overall route. So it was not hard to decide to skip that part and I now had a short 20 mile day. This worked out swimmingly as these 20 miles were stunning and provided reason to stop and take photos almost every 50 feet. The wind was back and working against me and I cursed not following the general advice of doing this route in counter-clockwise direction. I took a wrong turn somewhere and then coming back for a ½ mile with the wind sent me sailing along at 30 mph without a pedal stroke. The Soca cut through a limestone gorge and my path followed more small roads and easy mountain bike trails, with a few river crossings over these lovely bridges.

The mountains I had been pedaling towards started getting closer and closer and pretty soon I found myself at my destination of the Koča pri izviru Soče mountain hut.

The hut is part of the Planinska Zveza Slovenije aka the Alpine Association of Slovenia and I had become a card carrying member the day before my trip, which meant I could sleep in the hut dormitory for a friendly 10 euro fee. It was early so I went on a rainy hike for the afternoon and I was glad I had packed my non-cycling shoes as the hike had me scaling some vertical faces before finding the source of the Soca river, a fissure in the mountain with a bottomless blue hole. The host of the hut fixed me up nicely with a wild mushroom stew, a delicious cottage cheese struklji, and a glass of wine. I climbed up the ladder into the loft dormitory and tucked in with my kindle for a good night of rest.

On the morning of Day 3 I breakfasted with my host again and discussed my cycling plans. She did not like my plan to continue up and over the Vrsic pass. The same snow that had closed the Mangart Saddle had apparently unofficially closed the road over Vrsic, unless your vehicle was equipped with snow chains. My bike was not. She called a hut-friend up on the mountain who confirmed her fears and told me I should not make an attempt. The detour was just not an option I would consider and I had been daydreaming about this pass for weeks so I thanked them both for their worry, but I’d be going up, and walking the bike if I needed to. As I stepped outside in the morning it was cold and grey again but I started pedaling and immediately climbing. Not 30 minutes later I was blessed with bright blue sunny skies that came out of nowhere and I knew I had made the right decision. The Vrsic Pass road is a military road built by Russian prisoners of war during World War I and has 50 numbered hairpin switchbacks, 26 going up on Trenta side and 24 (cobblestoned!) descending on the Kranska Gora side. The road was also absolutely stunning and a pleasure cycling up. The feeling was incredible. I looked behind me to see the valley from where I had just came, the sharp bends of the road getting smaller and smaller as I climbed higher and higher, and the surrounding mountains getting closer and closer and just could not believe this was reality.

Somewhere around switchback 20 or so, I was nearly at the summit and the warnings came true. The temperature plummeted and the road surface was covered with a few inches of snow over a sheet of ice. I ran into an older Austrian couple I had spoken with the day before in their SUV as they were turning around because their vehicle couldn’t make it up the road. Despite the snow we shared this moment of excitement because of the beauty of the mountain peaks and the encouraging sunshine. They asked how it was cycling in the snow and I replied “it doesn’t matter. it’s beautiful” to which they replied in charming Austrian accents “IT IS SO BYOOTTEEEFULLLL”. I pedaled when I could and pushed the bike when I couldn’t and put on all my layers and both pairs of gloves and made my way across the 4 or 5 km of snow covered summit. A well placed hut provided a hot tea to warm myself back up before making the descent. The north side has cobblestones on each of the 24 hairpins which was not ideal for a bicycle moving way too fast, but maybe that extra caution kept me from flying off the road and off the mountain. In any case, the descent was over before I knew it and I paused at Lake Jasna to admire the morning’s accomplishment.

From here I would enjoy 25 miles of picture perfect solitary riding along a tiny perfectly paved road/path through the Triglavski National Park, all the way to Lake Bled.

And somehow this cycling utopia of a road provided me with my only puncture of the trip.

A quick lunch in Bled and a lap around the lake and I continued on my way. After a few km I turned off the paved road and onto a mountain bike trail and started on the 2nd big climb for the day. A much smaller one at 580 m, but a much harder one thanks to the dirt and varying 8 – 15% grade.

But the top would reward me well with this alpine meadow and a view the whole way down the other side of the mountain to Bohinjsko Jezero.

I was further rewarded with freshly paved and absolutely perfect tarmac which allowed me let the bike sing down the swoopy descent. There were a few shouts of excitement as I was having so much fun and my bike felt so good. A few minutes later I was down at the lake (Bohinjsko Jezero).

A quick pedal to look around town and then I had a 5 or 6 km ride back up into the woods to another Alpine Association hut where I planned to stay. I approached a closed looking hut but was happy to see there was a woman doing some work around the back. But unluckily she informed the hut was closed until the weekend. The day was too good to let this setback annoy me so I quickly turned around and another trip back down to town and I managed to find a lovely little hotel lodge to call home for the night with an excellent “Foksner” burger and great selection of Slovenian craft beers. I toasted to an unforgettable day on the bike and was drunk in one pint and asleep in two. The next morning I woke up high on the euphoria of such a good previous day. I didn’t have any epic alpine passes planned for the day but overall it was the biggest day of the trip I had planned. I looked out the window and saw a miserably grey sky and rain pouring down. I checked the forecast and it did not look good.

I reviewed my planned route and saw I had quite a bit of climbing and a lot of it was on mtb trails. This just did not sound fun in 40 degrees and rain all day so I decided to call an audible and re-routed myself to a more direct route on mostly pavement. This cut the day down to a more manageable 95 km. The rain never stopped aside from one hour of respite, and it was indeed cold, but I layered up, put some house music on my Bluetooth speaker on my handlebars, and got into a groove with my cadence and pedaled instinctively. It was great and miserable at the same time. The route would take me along some beautiful roads and some average ones, and eventually I reached my somewhat arbitrarily selected destination of Trojane.

From Trojane I had picked out another Alpine hut for my accommodation. This was about 10 km outside of town and seemed doable from my review of the maps. My confidence was shaken though, by the previous day’s surprise closed hut. I continued out of town towards the woods and the hut. I got to the last remnants of a village before entering the woods and saw a woman outside and asked if she had any idea if it would be open or not. She didn’t speak a lick of English but grabbed her son who did and he knew the hut and was fairly confident it was only open on weekends so would be closed. I knew that would be a pretty terrible thing to trudge up to this hut only to come right back down, all in the cold pouring rain, at the end of a long day, and I also really liked the idea of a hot shower at that point (no showers at the Alpine huts) so I accepted defeat and headed back to Trojane for a hot tea and to figure out accommodation for the night. I met Melita in the Trojane café and we made friends and she was thrilled that I chose Slovenia for my cycling trip. We took a photo on her ancient digital camera. I took advantage of the wifi and successfully booked another cheap room at the wonderfully Soviet-esque meets mid-century modern Hotel Trojane. The hot shower made it worth every single euro (not that many!) and I cranked the heat and used my bike as a drying rack to try to dry off my thoroughly soaked clothing.

After an excellent night’s rest, I had an easy route planned from Trojane to Ljubljana for two day’s in the city. But I wanted more bikes so I planned a big epic murderous ride up to the Austrian border, across three mountain passes, and then back down to Ljubljana. Then I checked on road closure conditions and two of the passes were closed because of snow so I settled for something in the middle with one mountain pass. But before that I had to go see Hut Dom dr. Franca Goloba na Čemšeniški planini, which was supposed to be my destination the night before. I headed back out of town, passed the woman and son whom I had spoken to the day before, and then started to climb up into the woods. I soon realized I had very much made the right choice as the roads up to the hut went from

to

to

And they got stupid steep. But eventually, after a couple miles that felt like an a couple hundred, I came to the hut.

What an amazing place. The host was there doing some sprucing up and though she spoke no English I was at least able to confirm she was there the night before. I didn’t regret my decision but I sure was glad I still came to see the hut. The view off the mountain and across the valley below was breathtaking and the grounds of the hut were charming as possible. Picnic tables covered in snow with the sun shining and an incredible view meant I had to enjoy a morning beer.

I enjoyed my beer and went back in the direction I had came but took another trail I thought might be more bike and less hike. It was not. But it eventually spit me out onto another dirt road which was a very fast way back down off the mountain.

I passed through Trojane one last time, grabbed a few snacks, and then quickly turned off the pavement and onto a forest road which was one of my favorite sections of the whole trip. I had the whole forest to myself and enjoyed beautiful and tranquil dirt roads in great shape as I climbed up and down the undulating hills. This heavenly dirt road brought me to another secondary paved road, a small mountain pass, and through a few small villages. I made a friend, enjoyed the rolling hills and perfect pavement, and soon found myself at the base of the Trobelkski Vrh climb. At 460 meters the climb was not insignificant but with grade hovering around 15% it was a worthy challenge, especially on my loaded bike. Luckily it rewarded my effort with another set of amazing views of my surroundings.

At the summit I turned onto a paved main road and had a thrilling 7 mile long descent back down to the Kamnik River. The asphalt was freshly laid and I raced a Subaru WRX down the hairpin turns. Towards the bottom there was a section of road work and the roadworkers were working on laying more of that sweet glass smooth asphalt. I yelled as I passed :chef kissing fingers: “IT’S BYOOTIFULLL” pointing the asphalt and they loved the appreciation and cheered me on with a round of ALLEZ ALLEZ ALLEZ. It was a great moment and made my already ear to ear smile stretch even bigger. I followed my route on into Ljubljana and easily found my hotel and settled in for two days of espresso, beer, and great food. Ljubljana is a lovely little European gem. The River Ljubljanica runs right through it with beautiful buildings and cafes running along it. The food is good, the beer is good and cheap and plentiful, the good espresso is really good, and everyone seems to be happy and friendly. It was a lovely little rest off the bike for two days.

After two days of relaxing, eating, and drinking, it was time to get back on the bike. I called ahead this time to make sure the Alpine hut was open and promised the host I would be there by late afternoon. Then I loaded all my belongings back onto the Rick Jones and headed west out of the city.

After 25 km of flat, boring riding I turned onto a dirt road and climbed a few hundred feet. Then another stretch of flat riding before I started up a really great 400 meter climb to the village of Podkraj. It started to rain along the way which put a bit of a damper on the long and fast descent, especially the -17% portion. I managed that ok but wished for disc brakes and cursed my luddite-ness. I entered into Slovenian wine country and cycled up and down and alongside numerous vineyards.

And then shortly after the village of Dolenje I was gingerly descending around a series of hairpin turns and all of a sudden I was on the pavement with a painful thud. I’m not sure what happened but my tire slipped out from under me as I was making my way around the curve, even though I was doing so really slowly. I crawled off the road and lay out in the grass moaning and groaning. I checked my bike and had to push the brake lever back into position and do my best to re-align the bent derailleur hanger. As I was laying there a car or two passed by, veeerryyyy very slowly and both checked to see that I was ok. A couple came cycling by on mountain bikes in the opposite direction as me and stopped to check on me and we chatted for a while. They were locals and told me everyone knows that road and especially that turn are dangerous and extremely slick.

Once I collected myself I had no choice but to continue on. From there I had 25 km to get to my hut. Luckily my bike worked well enough, even without perfect shifting. The rain started to come down hard with about 20 km to go so I gritted my teeth and pushed on, up into the woods again. The last 8 km or so were really gorgeous but there was no time for photos with the rain so I pressed ahead, anxious to make it to the hut and looking forward to a hot meal and a drink. Some time around 4 pm I got to the Hut Stjenkova koča na Trstelju and looked forward to drying off and going to sleep very early.

As I entered dripping wet I saw two men and a beautiful but terrifying German Shepherd. Then a third man bolted up from behind a table. He was the host, Bostjan, and I had just woken him up from his afternoon nap. “YOU! NEW YORK!?” he yelled out and I confirmed. He commanded I sit down and placed a beer in front of me straight away. From there it would turn into absolutely the most fun night of the trip. Bostjan, and his friends Dragan the casino craps dealer and Miha the former motocross champion of Yugoslavia and the beautiful blue-blooded lineage purebred German Shepherd called Siri welcomed me into their Saturday night party. The beer flowed non-stop, I fortified myself mid-way with a hearty stew, and then again with a late night pancetta party, Bostjan brought out home-made grappa from his fellow communist (“NO, SOCIALIST”) comrades, Dragan brought out his homegrown Slovenian mountain kishkish, we toasted to Tito’s portrait multiple times, and some time around 1 am we had drunken 20 L of Laško beer and the keg was kicked. I couldn’t have asked for a better last night in Slovenia. I will never forget those guys and the fun time we shared.

I woke up the next morning in a haze and hurting just as much from the crash the day before as from the drinking. Bostjan stumbled to the kitchen and prepared me a breakfast of scrambled eggs with beer, along with more pancetta and then I had a short last day to finish out the trip and return to Gorizia.

I was able to enjoy the mountain roads without so much rain this time and after a quick 50 km I was back in Italy and the whole town was closed since it was Sunday. I checked back into the hotel I had started the trip at, went through the tedious process of disassembling and packing my bike back into the s&s case, wandered aimlessly on foot until I eventually found something open ending up back at the same pizza place I had visited 7 days previous (very good pizza!), and got a night of rest before waking up early for the long travel journey of a train to Venezia, bus to the airport, 13 hour flight to Philadelphia, 6 hour layover which worked out perfectly for a happy hour reunion with friends, and then a one hour flight back to LaGuardia where I and thousands of other people would deal with the hell that is LaGuardia construction and transportation. At 2 am I walked back in the door of my Brooklyn apartment, dropped all my things at the front door, and collapsed into bed for a few quick hours of sleep before waking up for work and re-entrance into the real world.

Before I sign off, what sort of bike nerd would I be if I didn’t nerd out on my bike and gear selected for the trip. I wanted this to be a non-camping inn-to-inn or hut-to-hut in this case tour to keep the bike relatively lightweight and make the riding more fun. My Rick Jones has served me well for 7 years now and did not fail on this trip.

-Even with the front rando bag, frame bag, and saddle bag adding on about 15 or so lbs, the bike was spry and handles like a dream.

-Braking is, well…its as good as you can expect from cantilevers I suppose. Pretty decent when dry and alarmingly inadequate when wet, which happened to be most of the trip.

-I refreshed the drivetrain a couple months ago with new 11 speed Ultegra which proved as reliable as expected. I changed out the compact gearing for 46/30 sub-compact chainrings mounted onto my White Industries VBC cranks and really appreciated that choice at many times throughout the trip, both going up the alpine passes in the 30 tooth and cruising along on the flats and downhills in the 46.

-The way-too-complicated electrical system, yes electrical system, consists of the SonDelux dynamo hub powering an IQ-X front headlight, as well as a taillight, and a Sinewave Revolution usb charger. The setup got complicated when I had to make it demountable for packing into the S&S case with quick-disconnects all over the place. One ripped out as I was taking the bike apart, requiring a last minute solder and leaving me not all that confident in the system holding up to the travel and the trip. But it turned out to not be an issue and worked the entire time and survived the disassembly and trip home with no problems or re-soldering required.

-Tire selection was the do-it-all goldilocks of a tire Compass aka Rene Herse Bon Jon Pass 700c x 35 mm. Everything is tubeless compatible but I ran tubes due to the packing wheels tightly into a suitcase a little smaller than the wheels are round. Aside from that sudden crash which probably can’t be blamed on the tire, they were great and gave me the road and gravel performance I wanted, while still being able to handle some rough stuff when the route turned more towards mtb trail.