#i find that when people from other countries blame this on tropical climate it distances us from them

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

for people who don't understand the causes of heavy rains in southern brazil. (for anyone who is even aware of it)

we don't have a tropical climate in the south. there is no rain or dry season or monsoons. our seasons are defined by temperature patterns, not lack or presence of rain, like those in other temperate climates. porto alegre is much closer geographically, culturally and climatically to buenos aires than to são paulo and even less so brasília.

the heavy rainfall does indeed have to do with deforestation in the amazon. but the amazon rainforest is only indirectly related to rainfall in the south of the country (as opposed to directly related in the southeast, such as rio - the amazon spawns rain clouds in the summer that cover all of central and nothern brazil - and this is called "SACZ", but these clouds don't cover the south or the northeast of the country).

what happened instead is that the degradation of both the amazon and other natural biomes in the country (such as the cerrado and the pantanal) has disrupted humidity patterns and contributed to the formation of dry heat domes in central brazil (including the state of são paulo) in autumn and spring, when that region of the country is no longer under the influence of SACZ and antarctic cold air waves are not strong enough to reach that far into the continent (and they would be in july and august, during the peak of the austral winter).

these new dry heat domes trap antarctic air in southern brazil in autumn and spring. since colder and warmer air both cause rainfall when moving through an area (and these are cold and warm fronts respectively), the atmospheric "shock" caused by the cold air trying to advance but being unable to break through the hot dome causes rain to pour over a single area. that's what's happening. central brazil is right now seeing very intense, record-breaking heat for autumn. but that is being muffled by what's going on in the south, which is incomparably worse.

so when people blame this on us for "chopping down the amazon"... well, would they say that about buenos aires if this were happening there instead? it's not about the amazon. these places - including the cerrado and the pantanal - are quite far from us and we have little control or awareness over what happens there. so it's part of something much worse that spans the entire globe. and also something related to brazilian culture - our apathetic, accustomed relationship with suffering, and our lack of foresight to avoid it in general.

#climate change#brazil#climate crisis#meteorology#i find that when people from other countries blame this on tropical climate it distances us from them#'oh it's that corner of the world it happens all the time'#no it's not#i've never seen it#neither have my parents#or people older than them#i get the feeling that this could happen anywhere#but maybe it's just me#because i'd never seen it happen close to me before#the climate crisis is here and it dawns on you when you see it before your eyes#and you feel it in your heart because it's people you know#places you know and cherish

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

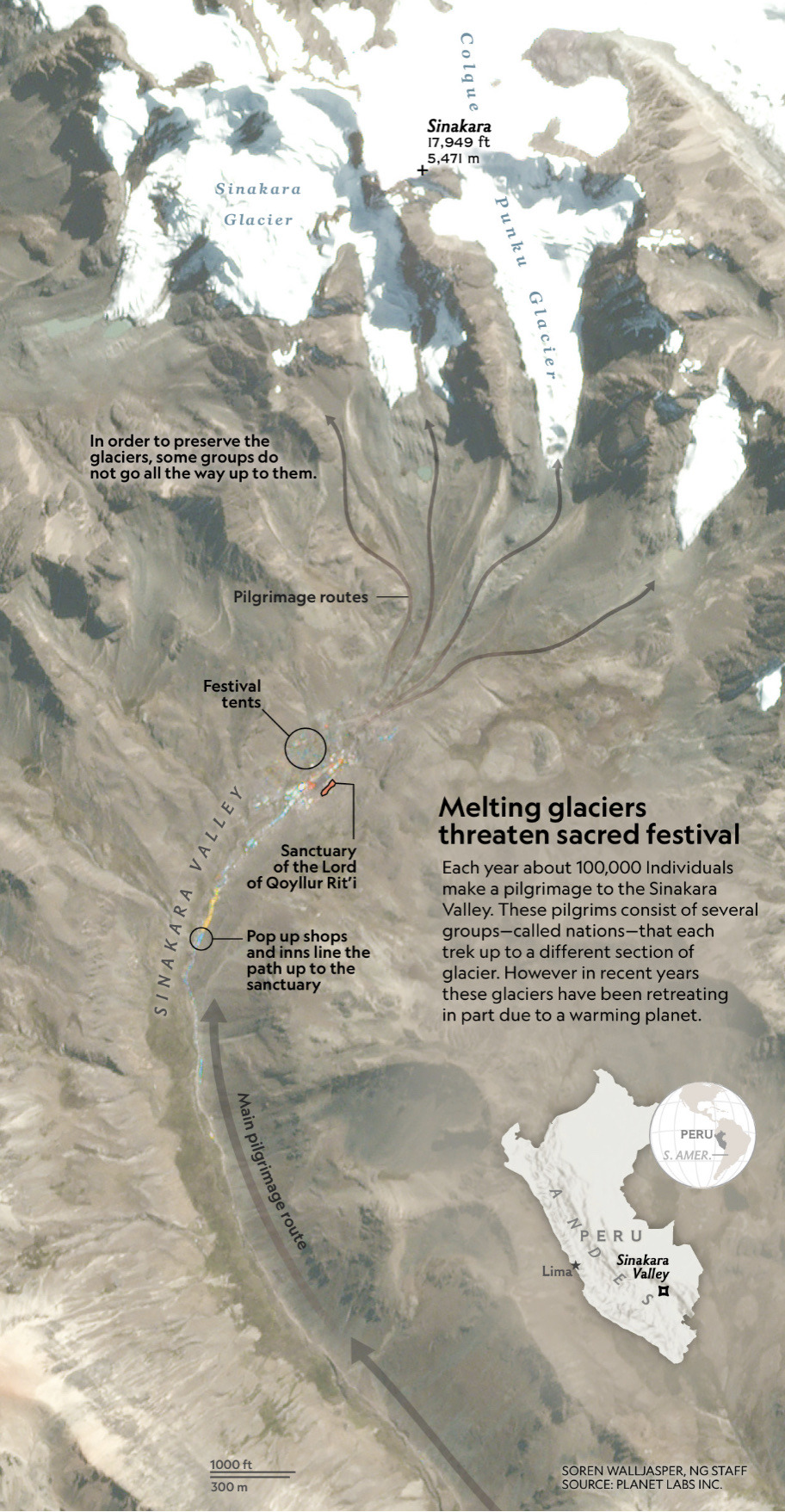

Andean glaciers are melting, reshaping centuries-old Indigenous rituals

The Snow Star Festival, an annual religious celebration, has been an integral part of Andean tradition and beliefs. But climate change and COVID-19 are threatening that.

— By Amanda Magnani | Photograph By Armando Vega | April 19, 2021

“It disappeared. And we asked ourselves, what happened?,” says Richart Aybar Quispe Soto, who has taken part in the pilgrimage for more than 35 years. “'Sin, it was sin,' they would say, and it wasn’t sin, it was global warming.”

At night, believers would use the reflection from the moon that cascaded atop snow-capped peaks as a guide to make their way up the sacred Colque Punku glacier. The tradition goes back centuries for pilgrims from various indigenous groups in the Andes who have made the journey through the Sinakara Valley in Peru during four days of religious festivities known as Qoyllur Rit’i, Quechuan for “the snow star.”

“When you go to Qoyllur Rit’i, you’re in a different space,” says Richart Aybar Quispe Soto, who has taken part in the pilgrimage for more than 35 years. “You get there, and you’re transformed. I go there to be in the snow, to be near the stars, to be close to the moon. I go there to see the first ray of the sun at dawn, to wait with great devotion, to return purified. Up there, we are reborn.”

Left: Dancers carry a cross at dawn as part of four days of religious festivities known as Qoyllur Rit’i, Quechuan for “the snow star.”

Right: Right: Only the oldest nations are allowed to climb the sacred Colque Punku glacier to perform some rituals. Dancers known as “Pablitos” who join the pilgrimage for the first time receive three lashes as part of longtime rituals.

Colque Punku glacier in the Sinakara Valley, Peru.

The Snow Star Festival has been an integral part of Andean tradition and beliefs. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, some 100,000 pilgrims would make their way to the Ocongate district in the southern highlands Cusco region of Peru. It is unclear if the festival will be formally held this year.

In recent years, the Colque Punku has lost some of its brilliance. The snow that turns into ice that forms the glacier is melting. Researchers have determined that tropical glaciers in the Peruvian Andes have decreased in size by about 30 percent in recent years.

“The effects of climate change today are not only compromising our survival but our ability to find meaning,” says photographer Armando Vega, who has been documenting the Qoyllur Rit’i tradition since 2017. “I hope the pilgrims' display of reverence to an element of Mother Earth can change people's perception of nature not only as a resource to be exploited for our communal gains, but as a gift that must be preserved, as a window to the human spirit.” (Some of the world's biggest lakes are drying up. Here's why.)

The Snow Star Festival, traditionally in late May or early June, mixes Roman Catholic and indigenous beliefs, honoring both Jesus Christ as well as the area’s glacier, which is considered sacred among some indigenous people. A central part of the pilgrimage is a sanctuary at the base of the mountain where a boulder features an image of Jesus Christ known as the Lord of Qoyllur Rit’i (pronounced KOL-yer REE-chee). Believers dance and pray long into the night, seeking health, peace and prosperity.

“We are not losing the ground we walk on. We are losing our mother,” Hélio Regalado, who has participated in the pilgrimage for 10 years as a Wayri Chunchu dancer, says of melting glacier.

Aybar Quispe, another one of the indigenous dancers known as the guardians of the glacier, says he is saddened by the knowledge that the melting ice means future generations will not experience the same kind of cleansing from the snow he was blessed with growing up.

“If the glacier were to disappear, I wouldn’t lose my faith if I couldn’t go to Qoyllur Rit’i, but I would be heartbroken,” he says. “A part of me would disappear.”

Left: Alejandro Quispe Huaman, an elder, poses for a portrait. Right: “When I walked up years ago, we didn't need, as we do today, lanterns to find the way,” says Richart Aybar Quispe Soto. “We had enough light from the glacier. When we arrived there at night, the moon began to rise—the mother moon—and little by little the area looked as if it were daytime. It was like heaven; it was a dream.”

The Andes, the longest mountain range in the world, spans seven countries — Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina and Peru. Seventy percent of the world’s tropical glaciers are in Peru and various studies have raised alarms at the rapid rate of melting ice in the region. (These Swiss villagers prayed for their glaciers to recede. Now they want them back.)

That has changed some of the longtime rituals.

In 2004, in an effort to slow down the rate of the melting glacier, festival organizers banned the practice of cutting blocks of ice to share with the community, believing the melted water had healing powers. “Many have cried. They broke down in tears, for this was a tradition of hundreds of years—but we had to make the decision to stop,” says Norberto Vega Cutipa, chairman Council of Nations of the Brotherhood of the Lord of Qoyllur Rit’i.

Road to the sanctuary of the Lord of Qoyllur Rit'I through the Sinakara Valley, Peru. On horseback or on foot, pilgrims carry their supplies, musical instruments, tents, bedspreads and everything else they will need during the four-day celebration.

Marcelino Lopez Ancali, of the Wayri Chunchu nation, stands before the Colque Punku glacier on which he was baptized as a child. The rocky area was once covered with ice. "Over the past five or seven years, the climate has changed. The cold and the heat are very different.” He blames pollution for the changing climate. “I do not know how we can prevent it. Sometimes people do not have the conscience to collect or recycle these plastics and we throw them anywhere polluting the environment…Now the sun is no longer as it should be. It is so strong, it's burning you. The cold too. It is not how it should be anymore."

Pilgrims remember the thick layers of ice from years past when the glacier was just a short distance from the site of the sanctuary and the moon illuminated the way. (Indigenous protectors of Colombia's sacred peaks have kept others out—till now.)

“When I walked up years ago, we didn't need, as we do today, lanterns to find the way,” says Quispe. “We had enough light from the glacier. When we arrived there at night, the moon began to rise—the mother moon—and little by little the area looked as if it were daytime. It was like heaven; it was a dream.”

“Describing how the glacier used to be is like trying to explain colors to a blind man,” says Quispe’s son, José Isaac Quispe Peralta,” also a dancer. “It’s impossible.”

“When I walked up years ago, we didn't need, as we do today, lanterns to find the way,” says Richart Aybar Quispe Soto. “We had enough light from the glacier. When we arrived there at night, the moon began to rise—the mother moon—and little by little the area looked as if it were daytime. It was like heaven; it was a dream.”

— The National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, funded Explorer Armando Vega’s work. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers working to inspire, educate, and better understand human history and cultures.

4 notes

·

View notes