#i do not pretend to understand the machinations of our system's background processes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

With the upcoming LoZ game, the excitement has managed to drag some of our Link fragments closer. Maybe listening to the 2018 anniversary concert wasn't the best idea in that regard, but it's always a bit of a ride having them near front.

They don't talk, but they can communicate with the system, and I have no idea how to even begin describing it. It's like they require someone else to proxy for them, to say what they want to say in order for them to communicate it.

For example, we found out Wild likes to sing. We were humming and singing along to something when we got an emotional response like joy from him, and rather than him spelling it out as "I like to sing," the others in front felt an urge to ask "Do you like to sing?" so that he could "nod" along.

In other cases, visual storytelling is also their next option forward.

They're an interesting bunch.

-IF11 (he/they/she)

#musings#systuff#botw#mm#ww#tp#if11#usually our linktrojects just come to front because they're doing the frontspace equivalent of laying on a rug to listen to music#they almost all exist to hold nostalgia for their respective era of zelda games#and that's embodied in the emotions they hold for the music#one time we were listening to one of the anniversary concerts and headspace molded to fit about a dozen people just to “watch” the concert#i do not pretend to understand the machinations of our system's background processes#i merely observe with curiosity the motions of our own mind sometimes#-if11

1 note

·

View note

Text

Human are weird: The GTO/SICON verse Reboot

The GTO, Or Galactic Treaty Organization is a military and political alliance between a number of species in the alpha quadrat of the galaxy. The GTO is a rather new organization only founded nine years ago following the first contact incident, where The Klendthu’s crash landed on a small cold planet on the edge of a solar system at the edge of the galaxy, and encountered a small outpost, one mis understanding later, and The Klendthu’s spent 6 Terren months fighting the creature’s from the fourth planet.

Once diplomacy was able to be established through communications a cease fire was called, and the strange race who called themselves Humans started a dialog.

Over the last nine years the alliance has grown to be a massive power house in economics, Politics and Defense. They are 4 major races in the alliance

The Klendthu Congress: an insect race with a regional hive mind, but don’t let that fool you, they are wicked smart and industrious. They have developed some of the most impressive mining tech available. Their planets is ruled by a Queen there entire government by the high queen, the average worker has about the same level of intelligence of a human 6 year old, but when working groups then can easily compete with a genius level human.

The Kalbur Merchant Empire: a race that vaguely resembles the big foots of earth legend. They are the economic Backbone of the GTO, there race is built around the building and creating of wealth, money heavily influencing there culture. Their government is run by a council of officials elected from the top business and workers unions on their world. In terms of technology they tend to lead in interstellar coms and other commercial type tech, with their military tech sorely lacking…as such they maintain an allied Military presence on their worlds.

The Verkia technocracy: an Aquatic telepathically floating species that vaguely resembles the squids of earth, they are the most advanced species in the known galaxy in almost every way. As such however they tend to be stiff and follow a very strict social custom; it is considered taboo for a student to leave the sciences in exchange for another discipline, sometimes leading as far as disowning by family and friends, or worse case total exile from Varikan society. There government is run by a council of appointed top scientists that are generally the heads of top instuites within Verikan space.”

The Strategically Integrated Collation of Nations: The Humans, the youngest race in the group as well as the craziest, Hailing from a death world on the edge of the galaxy where everything can and will kill you they are a society still recovering from finding out aliens even exist and there conflict with them. SICON was formed after the Pluto attacks from several of the earths major nation states, pushing aside the last barriers to unification. SICON is a democracy, with each former earth nation state, and Human colony earning a seat in the SICON Parliament with the majority seat holder winning said election with the party head becoming the Prime minster, Underneath them is the Star Marshal, commander in chief of the SICON Navy, and the ODT’s or Orbital Drop Teams… highly trained and equipped soldiers who go through a strict selection process. The nature of the human world as well as their Military technique’s make them the leader in Military technology by miles, with standard issue power suits for ground forces, the entire concept of Orbital insertion, air support and deep space carriers being introduced by the humans. These advantages are only enhanced by their natural predatory nature and ability to hone their bodies into killing machines….

T’Las groaned scratching her fur groaning “Great I keep making the humans sound terrifying.” The Kalbur sat back in the far too tall chair. It was built for a human after all she groaned, she sat in a gray metal room, the thick bulkheads joined into a thick window showing the swirls of hyperspace outside the window.

T’Las was grateful to the human for letting her take his office as he called it, but honestly being on a human ship was scary…well the entire assignment she was given was scary. 18 terran months ago a Verkian science ship crash landed on a Pre FTL society and well the folk on the planet went crazy fighting over the tech they could barely understand, by now only two groups remained on the planet before the GTO sent an intervention team, well Humans falling from the sky into your main base would put the fear of god into anyone and the sides agreed to moderated peace talks, she had actually been invited to dine in the captain’s cabin with the Ambassador, the Captain and the ODT Commanding officer, and had to quickly get ready. She put on her formal fur clips and quickly moved through the ship.

The Valley Forge is what the humans called it and as human ships go it was on the small side, only 400 meters long and 600 across. The vast majority was taken up by the Chekov drive core and the small retrieval ship and drop tubes for the ODT team. She left the section of the ship past a group of humans joking about something called a date, before she left the ODT region of the ship.

It took her a couple of minutes and asking for direction’s before she arrived at the metal door. She knocked and a human voice called “come in.”

Inside were to humans before dressed in their formal uniforms, one had more bars across her shoulders and was a human female, T’Las was able to identify as she introduced “Hello, you must be the reporter joining us, I’m Captain Hernández.”

The male human who was also in Dress uniform had shoulder patches on the side of his jacket that looked kind of like the Human drop pods as he introduced “Lieutenant William Erickson, ODT senior officer.”

T’Las carefully took the offered seat “Nice to meet you Captain Hernández, Lieutenant Erickson.”

There was sound of something scraping and a robotic voice saying “May I enter.”

Erickson and Herandez stood up as the door opened, in stepped a creature that walked on four legs, it was armoured and had 4 side facing eyes, attached to its chest was a small box, Herndez smiled “your Majesty.”

The creature screeched before a second later the robotic voice spoke “Captain, Lieutenant…we have known each other long enough to dispense with the Niceties surely.”

Erickson laughed “I’m sorry to say its official orders, they don’t want us causing too much trouble.”

Herndez chuckled as she said “you’re Majesty Queen of Gamma prime, this is T’Las of the Kalbur.”

T’Las had never seen a klendtuian queen before and muttered out a “Hello…your majesty.” She quickly added bowing slightly.

The queen made a chirping sound that robotic voice translated to a disjointed human laugh before saying “there is no need we are all equals here.”

The three of them sat down as a small platform elevated the queen to the table, Erickson took a sip of water saying “the squad says hi, and Futuba was real bummed she could not join us.”

The queen somehow betrayed a guine response through the robotic voice as she responded “I’m sorry they were unable to join, it has been for too long since I last saw dagger squad.”

A couple of humans still in there dress best placed done four plates, for the humans it was a simple salad meal with Erickson grinning “SICON figured streaks were not a good look.”

The queen chirped again as a plate of strange green slush was placed in front of her and T’Las got a salad in the style of her people. T’Las asked “so how do you all know each other?”

Erickson smiled without showing teeth “long story, it involves a lot of explosives.”

The queen scratched “it was my vessel that crashed on Pluto, then private Erickson, and then flight Lieutent Hernández crash landed in my den, we were lucky enough to have gotten our…talk box open…they were the first to talk to us…they helped us build peace.”

Erickson smiled “we got a cease fire and spent 3 weeks talking, we had to live off my mom’s cookies.”

The queen chirped “I’m sorry you could not eat our food.”

Herndez grinned “I thought the food was ok, the company was awful.”

Erickson looked genuinely hurt as the conversation moved to a different topic.

17 hours later:

T’Las was sitting in her quarters/ borrowed office mussing about the nature of Human space travel. Most other GTO races have adopted the supercharged carrier system, where the engines have a certain particle run through it in an infinite loop that somehow results in faster than light travel; Humans on the hand adopted the Chekov hyper drive, named after the human scientist Anton Chekov who invented it. The Chekov drive punches a hole in subspace allowing the human ship to enter into another dimension allowing the vessel hundreds time faster than the speed of light.

T’Las did not pretend to be well versed on the subject of interstellar Star ships but she started to write “as I fly on the human ship I noticed something interesting about the difference in the FTL Technology employed by SICON as opposed to the employed by the rest of the GTO, but first some background, for any ready who is not aware Humans are pursuit predators, what does this mean? imagine for a second that you are a terran creature, you see a human coming and run away. The issue is you are faster than the human but the human can chase you as far as they need to, sometimes for kilometers and days at a time.”

T’Las read that and said “NOPE.” She quickly edited “Being a Pursuit predator means they chase their prey, sometimes for days and across vast landscapes, just about anything can out sprint the average (non -power suit wearing) human, but in a distance race…you lose every time. What is the relevance of what I’m saying? Well Most FTL tech we know of is faster than Human hyperspace, but the Humans can go farther and for longer…Example, A Kalbur ship and a human ship need to cross GTO space, the distance is say 15 Cubic light years, The Kalbur ship would rock ahead of the ship until about 5 light years at which point it needs to slow down to let the engines recharge, by contrast the humans will stay be coming and easily overtake the Kalbur, once the Kalbur engines re charge they will jump and yet again overshoot the humans until uh oh, they have to stop again, meanwhile the humans have being moving at a steady pace this entire time and easily yet again over take the Kalbur and hit where they want to be easily hours before the Kalbur vessel.”

T’Las read it over before nodding approvingly “that’s better.” Adding “now the logical next question, what about in combat and yes it is as terrifying as you would think, the humans with their massive over gunned ships firing hunks of metal at a quarter of the speed of light at you, so you make a break for it…and you think you are in the clear then boom, they appear out of nowhere (reminder that we have yet to have anyway detect someone in Chekov travel, and if the humans do they are not sharing.) You can’t run you can’t hide you can only that they are feeling merciful.”

T’Las re read the last paragraph saying “way to dark…” deleting the last paragraph she smiled sending the story off, as well as her other noted on the function .

7 hours later:

T’Las heard a small knock on her door, and opened it to see a human with a strange shape on her face the human grinned “Hiyo.”

T’Las blinked “uhh hi?”

The human smiled “Specialist Futuba Kurogane, Dagger Squad, intel and Communication’s.”

T’Las nodded “Pleasure…uhhh not to be rude?”

Futuba grinned “oh yea right, this came for you from your boss,” Handing T’Las a drive saying “have a good one.”

T’Las played the message and it was her boss telling her “that last story is a gold mine! We have re run it 4 times and they still want more! Keep up the good work!”

T’Las rewatched the message 4 times saying “people are really that interested?”

2 hours later:

T’Las backed up as the creature advanced towards her, it was on four legs and bore it’s teeth as it sniffed her, the humans office door had closed cutting off her escape from the predator, T’Las considered making a break for it when a human shouted in a language her translator did not recognize. The creature instantly stopped sniffing her and trotted back towards the human, the human was a female of darker complexion who smiled sheepishly, saying to T’Las “sorry about Porthos here.”

T’Las took a deep breath before yelling “WHY DO YOU HAVE A DEADLY PREADTOR IN YOUR INCLOSED SPACESHIP!”

The human rolled her eyes “she is a MWD.”

T’Las said “what!?”

Erickson rounded the corner saying with crossed arms “heard some yelling, what’s the issue Specialist?”

He reached down petting the creature as the other human said “Porthos seems to put the fear of god into our guest here.”

Erickson sighed “Abebi, you know we had aliens onboard who would be scared of Porthos.”

Erickson looked at T’Las before saying “come on, I will fill you in.”

Mess hall:

Erickson drunk a glass of water explaining “there is a creature on earth called a dog.”

T’Las nodded following, as Erickson sighed “these animals have amazing sense of smell so we train them to find things for us; Porthos for instance is a bomb sniffer….so if you ever see him sit run….Abebi, is his Handler she takes care of leads the dog on mission’s…that make sense?”

T’Las sighed “sure you humans have trained a deadly predator to find equally deadly explosives for you…great…”

Erickson glanced at his wrist “we are almost at the planet get ready.”

Clapping T’Las on the shoulder

Hanger bay:

The ship rocked as it dropped out of hyperspace, Ericson was dressed in strange 4 piece garments with dark lens over his face as he explained “this place was a warzone a few days ago, so stay close and do as we tell you, everyone follow?”

The queen squawked her affirmative and T’Las nodded awkwardly as they boarded the military drop craft.

4 hours later:

The conference had been going on for hours now with the creature Porthos and his handler walking around constantly as the rest of the humans eyed the assembled crowd, so far everything was safe and secure. The peace was signed But then the meet and greet and the glad handing with the all the ambassador’s started, and well T’Las was happy she had her camera drone on for what happened next.

The drone had been flying around the room for about twenty minutes when an alien stepped forward to speak to the ambassador’s, Porthos walked towards the alien sniffing before sitting facing him. T’Las remembering what Erickson said looked for something to hide behind as all the humans in the room stiffed, The queen knowing what Porthos was as well changed color, however the aliens on the planet did not know what was about to happen. A tense second later, small sliver looking weapons appeared in the humans hands as Erickson yelled “hands in the air!”

Porthos rose up barking as Erickson yelled “Abebi!”

The handler nodded “on it sir!” yelling something in a strange human language, the dog advanced on the now terrified alien, sniffing before looking at the creatures jacket and growling. The humans moved in as Erickson said “Futuba call for evac, Abebi.”

The handler interrupted “checking the entire room got it.”

Erickson threw the alien down pulling out a bomb he quickly defused he said “Valley Forge we are pulling out over!”

The delegation quickly moved out to the waiting drop ship, handing the would be bomber over to the locals they blasted off, the humans visibly relaxed and started chatting with each other and the queen like they all almost didn’t get blown up, leaving T’Las to come to the conclusion “Humans are weird. “

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

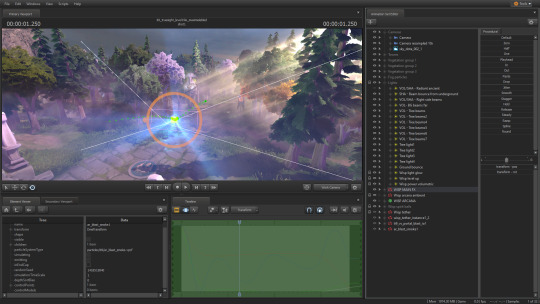

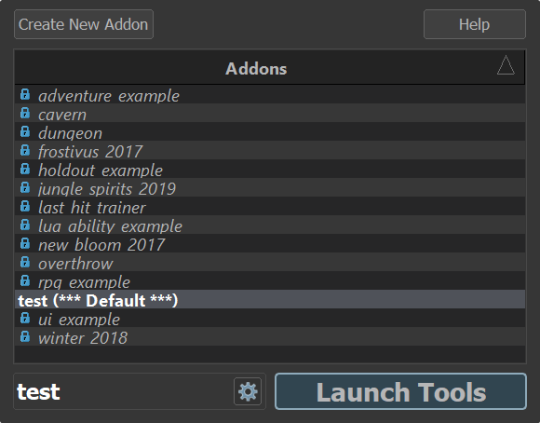

How to launch a symlinked Source 2 addon in the tools & commands to improve the SFM

I like to store a lot of my 3D work in Dropbox, for many reasons. I get an instant backup, synchronization to my laptop if my desktop computer were to suddenly die, and most importantly, a simple 30-day rollback “revision” system. It’s not source control, but it’s the closest convenience to it, with zero effort involved.

This also includes, for example, my Dota SFM addon. I have copied over the /content and /game folder hierarchies inside my Dropbox. On top of the benefits mentioned above, this allows me to launch renders of different shots in the same session easily! With some of my recent work needing to be rendered in resolutions close to 4K, it definitely isn’t a luxury.

So now, of course, I can’t just launch my addon from my Dropbox. I have to create two symbolic links first — basically, “ghost folders” that pretend to be the real ones, but are pointing to where I moved them! Using these commands:

mklink /J "C:\Program Files (x86)\Steam\SteamApps\common\dota 2 beta\content\dota_addons\usermod" "D:\path\to\new\location\content"

and

mklink /J "C:\Program Files (x86)\Steam\SteamApps\common\dota 2 beta\game\dota_addons\usermod" "D:\ path\to\new\location\game"

Now, there’s a problem though; somehow, symlinked addons don’t show up in the tools startup manager (dota2cfg.exe, steamtourscfg.exe, etc)

It’s my understanding that symbolic links are supposed to be transparent to these apps, so maybe they actually aren’t, or Source 2 is doing something weird... I wouldn’t know! But it’s not actually a problem.

Make a .bat file wherever you’d like, and drop this in there:

start "" "C:\Program Files (x86)\Steam\steamapps\common\dota 2 beta\game\bin\win64\dota2.exe" -addon usermod -vconsole -tools -steam -windowed -noborder -width 1920 -height 1080 -novid -d3d11 -high +r_dashboard_render_quality 0 +snd_musicvolume 0.0 +r_texturefilteringquality 5 +engine_no_focus_sleep 0 +dota_use_heightmap 0 -tools_sun_shadow_size 8192 EXIT

Of course, you’ll have replace the paths in these lines (and the previous ones) by the paths that match what you have on your own machine.

Let me go through what each of these commands do. These tend to be very relevant to Dota 2 and may not be useful for SteamVR Home or Half-Life: Alyx.

-addon usermod is what solves our core issue. We’re not going through the launcher (dota2cfg.exe, etc.) anymore. We’re directly telling the engine to look for this addon and load it. In this case, “usermod” is my addon’s name... most people who have used the original Source 1 SFM have probably created their addon under this name 😉

-vconsole enables the nice separate console right away.

-windowed -noborder makes the game window “not a window”.

-width 1920 -height 1080 for its resolution. (I recommend half or 2/3rds.)

-novid disables any startup videos (the Dota 2 trailer, etc.)

-d3d11 is a requirement of the tools (no other APIs are supported AFAIK)

-high ensures that the process gets upgraded to high priority!

+r_dashboard_render_quality 0 disables the fancier Dota dashboard, which could theoretically by a bit of a background drain on resources.

+snd_musicvolume 0.0 disables any music coming from the Dota menu, which would otherwise come back on at random while you click thru tools.

+r_texturefilteringquality 5 forces x16 Anisotropic Filtering.

+engine_no_focus_sleep 0 prevents the engine from “artificially sleeping” for X milliseconds every frame, which would lower framerate, saving power, but also potentially hindering rendering in the SFM. I’m not sure if it still can, but better safe than sorry.

+dota_use_heightmap 0 is a particle bugfix that prevents certain particles from only using the heightmap baked at compile time, instead falling back on full collision. You may wish to experiment with both 0 and 1 when investigating particle behaviours.

-tools_sun_shadow_size 8192 sets the Global Light Shadow res to 8192 instead of 1024 (on High) or 2048 (on Ultra). This is AFAIK the maximum.

And don’t forget that “EXIT” on a new line! It will make sure the batch file automatically closes itself after executing, so it’ll work like a real shortcut.

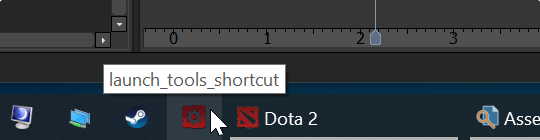

Speaking of, how about we make it even nicer, and like an actual shortcut? Right-click on your .bat and select Create Shortcut. Unfortunately, it won’t work as-is. We need to make a few changes in its properties.

Make sure that Target is set to:

C:\Windows\System32\cmd.exe /C "D:\Path\To\Your\BatchFile\Goes\Here\launch_tools.bat"

And for bonus points, you can click Change Icon and browse to dota2cfg.exe (in \SteamApps\common\dota 2 beta\game\bin\win64) to steal its nice icon! And now you’ve got a shortcut that will launch the tools in just one click, and that you can pin directly to your task bar!

Enjoy! 🙂

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

davis tower kingsley (listed here on the cfar instructor page) who harassed a cis woman about her appearance another cis women reported this to acdc (the people who wrote the thing about how brent was great) and afaict they did nothing, claims that if trans people and gay people dont "repent and submit to the pope" they will burn in hell, defended the spanish inquisitions, wrote about how the mission system werent actually abductions, slavery, forced conversions and this was propaganda, defends pretty much any atrocity that an authority, "believes" the catholic god exists and does not try and destroy them, submits to them. and so much more.

born into another era they would actually work for the california mission system and say it was good.

said thing that cached out to that emma and somni should repent and submit to the rationalist community. wrote up a rant about "how about fuck you. go lick the boots of your dark mistress anna salamon." didnt send. got kicked by some rationalist, reasoning is probably that what id say would disrupt their peaceful machinations of omnicide, would be infohazards, because... the information is hazardous to their social order.

a few of these things are subjects of future blog posts.

--

cfar has never hired a trans woman, i have lots of logs of them trying to do what people did to porpentine. claiming emma thinks torturing children is hot, claiming emma was physically violent, claiming emma was indistinguishable from a rapist, claiming ziz was a "gross uncle style abuser", claiming somni was enticing people to rape, claiming that anna salamon was a small fragile woman and ziz was large and had muscles. as if any of our strength or speed had anything to do with our muscles in this place. all of these things are false except relative size difference between ziz and anna which is just transmisogynistic and irrelevant.

if they lie about are algorithms claim that we are using male-typical strategies and then they can fail by these lies and be sidelined by callout posts that transfered 350,000$ from miri despite their best efforts to cover this up. (all benefited by having relative political advantagr flowing from estrogenized brain modules. men are kind of npc's in this particular game of fem v fem cyberontological warfare for the fate of the multiverse, mostly making false patriarchal assumptions that ziz was doing things for social status. like status sensitivity is hormonally mediated, your experiences are not universal. or saying like kingsley is saying that people should repent and submit to whatever authorities in the rationalist region they submit to. NO. FUCK YOU. i will not repent and submit to your abusive dark mistress anna salamon.

i knew anna salamon was doing the edgy "transfems are all secretly male" thing before i talked with ziz. it was a thing, {zack, carrie}, ben hoffman, michael vassar were also in on it. ppl had men trapped in mens bodies on their bookshelves because the cool people were reading it. didnt think she was being *transmisogynistic* about it until i talked with ziz. in retrospect i was naive.)

also? anarchistic coordination ive had with people have been variously called lex's cluster, somni's cluster, ziz's cluster by authoritarians who cant imagine power structures between people that arent hierarchical. like based on who they want to say is "infohazardously corrupting people" emma goldman had to deal with this shit too where the cops tried to say she was friends with anyone who thought anarchism made sense. people she didnt know at all who did their own anarchism. because authoritarians dont think in terms of philosophy, they think any challenge to their power is a disease that needs to be eliminated and you just need to doxx their network.

like if ziz and somni and emma were all actually infohazardous rapists as people keep trying to claim we are and then saying "oh no i didnt mean it i swear" and then doing it again. what would happen isnt that a bunch of infohazardous rapists start talking and working together for a common goal. what actually happens with people of that neurotype is they partition up the territory into rival areas of feeding on people like gangs do.

like they dont get together and start talking a lot about decision theory and cooperate in strange new ways.

not that the people lying about emma, ziz, gwen, somni and others are trying to have accurate beliefs. they are trying what all athoritarians try with anarchist groups. unfortunately for them, ive read the meta, i know dread secrets of psychology and cooperation that they claim are like painful static and incomprehensible, yet despite being "incomprehensible" are almost certainly harmful. if harm is to be judged against upholding the current regime, and the current regime is evil, then lots of true information and good things will look harmful. like ive tested this out in different social spheres what people claim is "incomprehensible" is the stuff that destroys whatever regime they are working in. like someone said i sounded like i was crazy and homeless and couldnt understand me when i pointed out that reorienting your life, your time, your money, to a human who happens to be genetically related to you for 16 years is altruistic insanity. just do the math. eliezer, anna, michael, brian tomasik all once took heroic responsibility for the world at some point in their lives and could do a simple calculation and make the right choice. none of them have children.

pretending that peoples "desires" "control them", when "desires" are part of the boundary of the brain, part of the brains agency and are contingent on what you expect to get out of things. like before stabbing myself with a piece of metal would make me feel nauseated, id see black dots, and feel faint. but after i processed that stabbing myself would cure brain damage and make me more functional, all this disappeared.

most people who "want" to have children have this desire downstream of a belief that someone else will take heroic responsibility for the world, they dont need to optimize as much. there are other competent people. if they didnt they would feel differently and make different choices.

you can see the contingency of how people feel about something on what they get out of it lots of places. like:

<<Meanwhile, a Ngandu woman confessed, "after losing so many infants I lost courage to have sex.">>

but people lie about how motivation works, in order to protect the territory of saying "well i just need a steady input of nubile fems so i can concentrate and be super altruistic!" or "i just need spend 16 years of life reorienting around humans who happen to be genetically related to me and my friends so i can concentrate and be super altruistic!" when neither of these are true. these people just want nubile fems, they just want babies. (the second one has much much less negative externalities though. you could say i am using my female brain modules to say "yeah the archetypically female strat, though it has the same amount of lying, is less harmful". but like it actually is less directly harmful. the harm from gaslighting people downstream of diverting worldsaving resources and structure to secure a place to {hit on fems, raise babies} is ruinous. means that worldsaving plans that interfere with either of these are actively fought. and the knowledge that neither of these are altruistic optimizations, neither is Deeply Wise they are as dumb in terms of global optimization as they seem initially, is agentically buried.

this warps things in deep ways, that were a priori unexpected to me.)

this is obvious, but when i talk about it, the objection isnt that it doesnt make utilitarian sense, the objection is that "im talking like a crazy person". authoritarians say this to me too when i assert my right to my property that they took, act like im imposing on them. someone else asked if i could "act like a human" and do what he wanted me to do when i was thinking and talking with my friends. all of these things authoritarians have said to me "act like a human" "talk like a normal person i cant understand you" were to coerce my submission. they construct the category of "human" and then say im in violation of it and this is wrong and i should rectify it. i am talking perfectly good english right now. you can read this.

anna salamon, kelsey piper, elle, pete michaud, and many others all try to push various narratives of somni, emma, ziz, gwen and others being in the buckets {RAPIST, PSYCHO, BRAINWASHED}. im not a rapist, im not psychotic, im not brainwashed. before ziz came along, people were claiming i was brainwashing people, its a narrative they keep reusing.

porpentine talks about communities that do this, that try and pull trap doors beneath trans women:

<<For years, queer/trans/feminist scenes have been processing an influx of trans fems, often impoverished, disabled, and/or from traumatic backgrounds. These scenes have been abusing them, using them as free labor, and sexually exploiting them. The leaders of these scenes exert undue influence over tastemaking, jobs, finance, access to conferences, access to spaces. If someone resists, they are disappeared, in the mundane, boring, horrible way that many trans people are susceptible to, through a trapdoor that can be activated at any time. Housing, community, reputation—gone. No one mourns them, no one asks questions. Everyone agrees that they must have been crazy and problematic and that is why they were gone.>>

https://thenewinquiry.com/hot-allostatic-load/

(a mod of rationalist feminists deleted this almost immediately from the group as [[not being a good culture fit]], not being relevant to rationalism, and written in the [[wrong syntax]]. when its literally happening right now, they are trying to trapdoor transfems who protest and rebel asap. just like google.)

canmom on tumblr talks about the strategic use of "incomprehensibility" against transfems. and how its not about "comprehensibility". i have a different theory of this, but her thing is also a thing.

<<Likewise, @isoxys recently wrote an impressively thorough transmisogyny 101, synthesising the last several years of discussions about this facet of our particular hell world. But that post got just 186 notes, almost exclusively from the same trans women who are accused of writing ‘inaccessibly’.

Perhaps they’d say isoxys’s post is inaccessible too, but what would pass the bar? Some slick HTML5 presentation with cute illustrations? A wiki? Who’s got the energy and money to make and host something like that? Do the critics of ‘inaccessible’ posts take some time to think about what kind of alternative would be desirable, and how it could be organised?>>

https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/185908592767/accessibility-in-terms-of-not-using-difficult

alice maz talks about the psychology behind the kind of cop kelsey piper, david tower kingsley, elle and others are:

<<the role of the cop is to defend society against the members of society. police officers are trivially cops. firefighters and paramedics, despite similar aesthetic trappings, are emphatically not. bureaucrats and prosecutors are cops, as are the worst judges, though the best are not. schoolteachers and therapists are almost always cops; this is a great crime, as they present themselves to the young and the vulnerable as their friends, only to turn on them should they violate one of their profession's many taboos. soldiers and parents need not be cops, but the former may be used as such, and the latter seem frighteningly eager to enlist. the cop is the enemy of passion and the enemy of freedom, never forget this>>

https://www.alicemaz.com/writing/alien.html

anna salamon wrote a thing implying that ziz, somni, gwen suffered some sort of vague mental issues from going to aisfp. (writing a post on this.) alyssa vance tried to suggest i believe cfar is evil because im homeless. but sarah constantin, ben hoffman, {carrie, zack}, jessica taylor (the last three who have blogged a lot about whats deeply wrong) (not listing others because not wanting to doxx a network to authoritarians, who just want to see it contained. and the disease of "infohazards" eradicated.) are not homeless and ive talked with many of them and read blog posts. and they know that cfar is fake. jessica (former miri employee) left because miri was fake.

anna and others are trying to claim that theres some person responsible for a [[mass psychotic break]] that causes people to... independently update in the same direction. and have variously blamed it on ziz, somni, michael vassar. but like mass psychotic breaks arent...really a thing, would not be able to independently derive something, plan on writing a blogpost on it, and then see ben hoffman had written http://benjaminrosshoffman.com/engineer-diplomat/ and i was like "ah good then i dont have to write this." and have this happen with several different people.

like this is more a mass epistemic update that miri / cfar / ssc / lw are complicit in the destruction of the world. and will defend injustice and gaslight people and lie about the mathematical properties of categories to protect this.

they all know exactly what they are doing, complicity with openai and deepmind in hopes of taking the steering wheel away at the last second. excluding non-human life and dead humans from the CEV to optimize some political process, writing in an absolute injunction to an fai against some outcome to protect from blackmail when that makes it more vulnerable.(see:

https://emma-borhanian.github.io/arbital-scrape/page/hyperexistential_separation.html

hyperexistential separation: if an fai cant think of hell, an fai cant send the universe to hell in any timeline. this results in lower net utility. if you put an absolute injunction against any action for being too terrible you cant do things like what chelsea manning did and i believe actually committed to hungerstriking until death in the worlds where the government didnt relent, choosing to die in those timelines. such that most of her measure ended up in a world where the government read this commitment in her and so relented.

if chelsea manning had an absolute injunction against ever dying in any particular timeline, she would get lower expected utility across the multiverse. similarly, in newcombs problem if you had an absolute injunction against walking away with 0$ in any timeline because that would be too horrible, you get less money in expectation. for any absolute injunction against things that are Too Horrible you can construct something like this.

--

a lot of humans seem to be betting on "nothing too horrible can happen to anyone" in hopes that it pays off in nothing too horrible happening to you.

the end result of not enacting ideal justice is the deaths of billions. at each timestamp saying "its too late to do it now, but maybe it would have been good sometime in the past". with the same motive that miri wants to exclude dead people from the cev, they arent part of the "current political process". so you can talk about them as if they were not moral patients, just like they treat their fellow animals.

(ben hoffman talks about different attitudes towards ideal justice coming upon the face of the earth.)

--

https://emma-borhanian.github.io/arbital-scrape/page/cev.html

cev:

<<But again, we fall back on the third reply: "The people who are still alive" is a simple Schelling circle to draw that includes everyone in the current political process. To the extent it would be nice or fair to extrapolate Leo Szilard and include him, we can do that if a supermajority of EVs decide* that this would be nice or just. To the extent we don't bake this decision into the model, Leo Szilard won't rise from the grave and rebuke us. This seems like reason enough to regard "The people who are still alive" as a simple and obvious extrapolation base.>>

https://emma-borhanian.github.io/arbital-scrape/page/cev.html

this is an argument from might makes right. because dead people and nonhuman animals cant fight back.

->"i think we should give planning of the town to the white people, then extrapolate their volition and if they think doing nice things for black people is a good idea, we'll do it! no need to bake them in to the town planning meetings, as they are arent part of the current political process and no one here will speak up for them."

i dont plan to exclude dead people or any sentient creatures from being baked in to fai. they are not wards of someone else. enslaving and killing fellow sentient life will not continue after the singularity even if lots of humans want it and dont care and wont care even after lots of arguments.) and so much else.

the list of all specific grievances would take a declaration of independence.

like with googles complicity with ICE having a culture of trapdooring transfems (for some reason almost the only coherent group that has the moral fiber to oppose these injustices, that is p(transfem|oppose injustice in a substantiative way) is high, not necc the reverse.) who question this sort of thing.

thinking of giving sarah constantin a medal thats engraved with "RIGHTEOUS AMONG CIS PEOPLE: I HAD SEVERAL SUBSTANTIAL DISAGREEMENTS WITH HER ABOUT LOAD BEARING PARTS OF HER LIFE AND SHE NEVER ONCE TRIED TO CALL ME A RAPIST, PSYCHOTIC, OR BRAINWASHED" thats where the bar is at, its embedded in the core of the earth.

kelsey piper, elle benjamin, anna salamon, pete michaud, and lots more have entirely failed to clear this bar. anna and kelsey saying they dont understand stuff somni, emma, ziz and other transfems talk about but its probably dangerous and infohazardous and its not to be engaged with philosophically. just like the shelter people acting as if my talking about their transmisogyny was confusing and irrational to be minimized and not engaged with. just like any authoritarian where when you start talking about your rights and what is right and wrong and what makes sense they are like "i dont understand this. you are speaking gibberish why are you being so difficult? all we need you to do is submit or leave."

and no i will NOT SHUT UP about this injustice. all miri/cfar people can do at this point is say "the things these people write are infohazards" then continue to gaslight others they cant engage on a philosophical level. all the can say is that what i am saying is meaningless static and yet also somehow dangerous.

::

it doesnt make sense to have and raise babies if you are taking heroic responsibility for the world. doesnt make sense to need a constant supply of fems to have sex with if you are taking heroic responsibility for the world. people who claim either of these pairs of things are lying, maybe expect someone else to take heroic responsibility for the world or exist in a haze.

the mathematics of categories and anticipations dont allow for the thing you already have inside you to be modified based on the expected smiles it gives your community. this is used to gaslight people like "calling this lying would be bad for the institutions, not optimize ev. thus by this blogpost you are doing categories wrong' this is a mechanism to cover dishonesty for myopic gains.

using the above, a bunch of people colluding with the baby industrial complex get together and say that the "beat" meaning of altruism includes having babies (but maybe not having sex with lots of fems? depending on which gendered strategy gets the most people in the colluding faction) because other meanings would make people sad and unmotivated. burying world optimizers ability to talk about and coordinate around actual altruism.

openAI and deepmind are not alignment orgs. cfar knows this and claims they are, gaslighting their donors, in hopes of taking the steering wheel at the last moment.

alyssa vance says paying out to blackmail is fine, its not.

CFAR manipulated donation metrics to hide low donations.

MIRI lied about its top 8 most probable hypotheses for why its down 350,000$ this year.

anna salamon is transmisogynistic, this is why cfar has never hired a trans women despite trans women being extremely good at mental tech. instead the hire people like davis kingsley.

kingsley lied about anna not being involved at hiring in cfar in order to claim anna couldnt be responsible for cfar never hiring a trans woman.

a cfar employee claimed anna salamon hired their rapist, was angry about it. mentioned incidentally how anna salamon, president and cofounder of cfar, was involved in hiring at cfar.

acdc wrote a big thing where defended a region of injustice (brent dill) because of their policy of modular ethics. when really, if you defend injustice at any point, you have to defend the defense and the thing iteratively spreads across your organization like a virus.

miri / cfar caved to louie helm.

not doing morality or decision theory right. among which is: https://emma-borhanian.github.io/arbital-scrape/page/hyperexistential_separation.html and https://emma-borhanian.github.io/arbital-scrape/page/cev.html

and so much more.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Misconception(s) of DevOps and how to overcome them

Introduction:

Having a misconception or two about a concept that is relatively new is very common. There are some misconceptions about DevOps in the market. Which prevents an organization from adopting it or growing the existing DevOps practice. In this blog, I’ve tried to list some of these misconceptions and their explanations

I’ve been working in software development for 12 years. So I have had plenty of experience with different types of projects. I have also started to work in DevOps (incidentally) over the last few years. And this has had me thinking about just why there is a backlash against the term “DevOps”. And because of this I wanted to put my thoughts on paper.

For those that don’t know. DevOps is actually an architectural view of how a business can improve its agility by adopting best-of-breed tool sets and improving processes for continuous delivery.

Misconception No.1: DevOps is a job title

This may be the biggest misconception out there. DevOps is not a job title. It’s not even an acronym. It’s more of a movement. A revolution even. But definitely not a job title.

There is a lot of confusion in the marketplace about what DevOps actually is. The good news is that it has been coined, defined, and so on. Nevertheless, there are still a lot of people who are thinking they need to hire a DevOps engineer. When they really need to hire someone with different skill sets and backgrounds.

Again, DevOps is not a job title. It’s a way for software developers (Dev) to work more closely with system administrators/operators (Ops).

In theory, this collaboration allows for increased efficiency. For instance, if the developers and operators can work together and anticipate each other’s needs. They could create something like automatic provisioning for physical servers or virtual machines (VMs). This means certain applications would start up when needed and stop when no longer needed. The benefits here are obvious — reduced power consumption and faster application startup times.

Misconception No.2: DevOps is just about automation

A lot of people (including a lot of CIOs) think that. DevOps is about tools and processes related to automating the deployment and operations of applications in production. This is only half true.

Tools like Puppet, Chef or Ansible can be useful for certain tasks, but DevOps is not just about tools — it’s about culture. The goal of DevOps is to improve collaboration between development and operations teams. By implementing new processes and tooling around continuous integration and continuous delivery.

DevOps is not a silver bullet that will solve all your problems, nor automatically make you money. DevOps has its own set of problems and assumptions. So you have to know what they are before you can start trying to fix them.

For example, DevOps is not just about automation. In fact, automation is the least important part of DevOps! Automation allows you to scale your operations reliably and predictably. It enables reliable deployments, better monitoring, and simpler/better testing – but it’s not the end goal!

I have seen this behavior many times at conferences and meetings. Where people talk about adopting DevOps without understanding what it means or why they should adopt it. They typically are focused on the tools they can use. Rather than the culture they need to adopt first if they want to succeed with DevOps. This is wrong and dangerous. Because they end up spinning their wheels trying to make tools fit into an organization that doesn’t understand or embrace DevOps as whole.

Misconception No.3: DevOps means we can take it easy

I have been lucky to be part of the agile software development community for a long time. There is one thing I have observed over the years that has become very clear to me.

This isn’t a groundbreaking observation. But it is something I see people pretending to know, or not care about all the time. That’s something that needs to change.

Everything we do in our personal and professional lives can be a learning opportunity. Our jobs are no different.

If you want to improve your job performance as well as your career. You need to keep learning about your industry and what others are doing in it. You may not agree with everything you read or hear. But if you don’t develop a critical eye you will never grow.

I have also seen many people believe that DevOps is just “agile lite.” It certainly shares some techniques with agile software development methodologies, but the two are not synonymous. The two may even work well together, but DevOps should be used with other processes and methodologies as well.

For example, I recently worked with an organization that had never done agile development before. They were reluctant to try out any agile practices because they did not want to mess up their existing waterfall processes and then have to go back and fix them. As we worked through some of these issues with them, they began to see how agile could really help them when paired with the right tools and approach.

Misconception No.4: You can deploy at any frequency in DevOps

Another misconception is that if you follow the principles of DevOps, you can deploy at any frequency you want.

There are certainly benefits to deploying more frequently, but there are also drawbacks, especially if your application isn’t designed to support frequent deployments.

One of the common reasons why organizations don’t deploy changes more frequently is. Because they have a hard time identifying the right folks who should be involved in making those deployments happen.

Conclusion:

There are many misconceptions about DevOps. If DevOps is to succeed, these misconceptions need to be addressed head on, or else they will continue to linger.

Implement a best practice, such as using automated testing for your development cycle, and you’ll find that many of the obstacles you might encounter are simply a matter of communication issues between your team members. DevOps doesn’t have to be complex.

To sum up, properly communicating with your DevOps team means making a conscious effort to understand not just the lingo, but also their reasoning for getting things done a certain way. This is vital, because in many organizations DevOps and operations roles are highly specialized.

If you don’t know what they’re talking about, they can’t tell you what they mean. This will result in miscommunication, which could result in missed deadlines, failed development cycles and more. To avoid this scenario it’s best to do your homework and understand DevOps so you can communicate effectively with your team and contribute to projects during their crucial time frames.

#devops#culture#developers & startups#edtech#currently reading#programming#code#technologies#software#technology

0 notes

Text

Voices in AI – Episode 73: A Conversation with Konstantinos Karachalios

Today's leading minds talk AI with host Byron Reese

.voice-in-ai-byline-embed { font-size: 1.4rem; background: url(https://voicesinai.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/cropped-voices-background.jpg) black; background-position: center; background-size: cover; color: white; padding: 1rem 1.5rem; font-weight: 200; text-transform: uppercase; margin-bottom: 1.5rem; } .voice-in-ai-byline-embed span { color: #FF6B00; }

About this Episode

Episode 73 of Voices in AI features host Byron Reese and Konstantinos Karachalios discuss what it means to be human, how technology has changed us in the far and recent past and how AI could shape our future. Konstantinos holds a PhD in Engineering and Physics from the University of Stuttgart, as well as being the managing director at the IEEE standards association.

Visit www.VoicesinAI.com to listen to this one-hour podcast or read the full transcript.

Transcript Excerpt

Byron Reese: This is Voices in AI, brought to you by GigaOm, and I’m Byron Reese. Today our guest is Konstantinos Karachalios. He is the Managing Director at the IEEE Standards Association, and he holds a PhD in Engineering and Physics from the University of Stuttgart. Welcome to the show.

Konstantinos Krachalios: Thank you for inviting me.

So we were just chatting before the show about ‘what does artificial intelligence mean to you?’ You asked me that and it’s interesting, because that’s usually my first question: What is artificial intelligence, why is it artificial and feel free to talk about what intelligence is.

Yes, and first of all we see really a kind of mega-wave around the ‘so-called’ artificial intelligence—it started two years ago. There seems to be a hype around it, and it would be good to distinguish what is marketing, what is real, and what is propaganda—what are dreams what are nightmares, and so on. I’m a systems engineer, so I prefer to take a systems approach, and I prefer to talk about, let’s say, ‘intelligent systems,’ which can be autonomous or not, and so on. The big question is a compromise because the big question is: ‘what is intelligence?’ because nobody knows what is intelligence, and the definitions vary very widely.

I myself try to understand what is human intelligence at least, or what are some expressions of human intelligence, and I gave a certain answer to this question when I was invited in front of the House of the Lords testimony. Just to make it brief, I’m not a supporter of the hype around artificial intelligence, also I’m not even supporting the term itself. I find it obfuscates more than it reveals, and so I think we need to re-frame this dialogue, and it takes also away from human agency. So, I can make a critique to this and also I have a certain proposal.

Well start with your critique If you think the term is either meaningless or bad, why? What are you proposing as an alternative way of thinking?

Very briefly because we can talk really for one or two hours about this: My critique is that the whole of this terminology is associated also with a perception of humans and of our intelligence, which is quite mechanical. That means there is a whole school of thinking, there are many supporters there, who believe that humans are just better data processing machines.

Well let’s explore that because I think that is the crux of the issue, so you believe that humans are not machines?

Apparently not. It’s not only we’re not machines, I think, because evidently we’re not machines, but we’re biological, and machines are perhaps mechanical although now the boundary has blurred because of biological machines and so on.

You certainly know the thought experiment that says, if you take what a neuron does and build an artificial one and then you put enough of them together, you could eventually build something that functions like the brain. Then wouldn’t it have a mind and wouldn’t it be intelligent, and isn’t that what the human brain initiative in Europe is trying to do?

This is weird, all this you have said starts with a reductionist assumption about the human—that our brain is just a very good computer. It ignores really the sources of our intelligence, which are really not all in our brain. Our intelligence has really several other sources. We cannot reduce it to just the synapses in the neurons and so on, and of course, nobody can prove this or another thing. I just want to make clear here that the reductionist assumption about humanity is also a religious approach to humanity, but a reductionist religion.

And the problem is that people who support this, they believe it is scientific, and this, I do not accept. This is really a religion, and a reductionist one, and this has consequences about how we treat humans, and this is serious. So if we continue propagating a language which reduces humanity, it will have political and social consequences, and I think we should resist this and I think the best way to express this is an essay by Joichi Ito with the title which says “Resist Reduction.” And I would really suggest that people read this essay because it explains a lot that I’m not able to explain here because of time.

So you’re maintaining that if you adopt this, what you’re calling a “religious view,” a “reductionist view” of humanity, that in a way that can go to undermine human rights and the fact that there is something different about humans that is beyond purely humanistic.

For instance I was in an AI conference of a UN organization which brought all other UN organizations with technology together. It was two years ago, and there they were celebrating a humanoid, which was pretending to be a human. The people were celebrating this and somebody there asked this question to the inventor of this thing: “What do you intend to do with this?” And this person spoke publicly for five minutes and could not answer the question and then he said, “You know, I think we’re doing it because if we don’t do it, others were going to do it, it is better we are the first.”

I find this a very cynical approach, a very dangerous one and nihilistic. These people with this mentality, we celebrate them as heroes. I think this is too much. We should stop doing this anymore, we should resist this mentality, and this ideology. I believe we make machine a citizen, you treat your citizens like machines, then we’re not going very far as humanity. I think this is a very dangerous path.

Listen to this one-hour episode or read the full transcript at www.VoicesinAI.com

Voices in AI

Visit VoicesInAI.com to access the podcast, or subscribe now:

iTunes

Play

Stitcher

RSS

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed { font-size: 1.4rem; background: url(https://voicesinai.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/cropped-voices-background.jpg) black; background-position: center; background-size: cover; color: white; padding: 1rem 1.5rem; font-weight: 200; text-transform: uppercase; margin-bottom: 1.5rem; } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed:last-of-type { margin-bottom: 0; } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed .logo { margin-top: .25rem; display: block; background: url(https://voicesinai.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/voices-in-ai-logo-light-768x264.png) center left no-repeat; background-size: contain; width: 100%; padding-bottom: 30%; text-indent: -9999rem; margin-bottom: 1.5rem } @media (min-width: 960px) { .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed .logo { width: 262px; height: 90px; float: left; margin-right: 1.5rem; margin-bottom: 0; padding-bottom: 0; } } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed a:link, .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed a:visited { color: #FF6B00; } .voice-in-ai-link-back a:hover { color: #ff4f00; } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links { margin-left: 0 !important; margin-right: 0 !important; margin-bottom: 0.25rem; } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:link, .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:visited { background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.77); } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:hover { background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.63); } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links .stitcher .stitcher-logo { display: inline; width: auto; fill: currentColor; height: 1em; margin-bottom: -.15em; }

Byron explores issues around artificial intelligence and conscious computers in his new book The Fourth Age: Smart Robots, Conscious Computers, and the Future of Humanity.

0 notes

Text

Voices in AI – Episode 13: A Conversation with Bryan Catanzaro

Today’s leading minds talk AI with host Byron Reese

.voice-in-ai-byline-embed { font-size: 1.4rem; background: url(http://ift.tt/2g4q8sx) black; background-position: center; background-size: cover; color: white; padding: 1rem 1.5rem; font-weight: 200; text-transform: uppercase; margin-bottom: 1.5rem; }

.voice-in-ai-byline-embed span { color: #FF6B00; }

In this episode, Byron and Bryan talk about sentience, transfer learning, speech recognition, autonomous vehicles, and economic growth.

–

–

0:00

0:00

0:00

var go_alex_briefing = { expanded: true, get_vars: {}, twitter_player: false, auto_play: false };

(function( $ ) { ‘use strict’;

go_alex_briefing.init = function() { this.build_get_vars();

if ( ‘undefined’ != typeof go_alex_briefing.get_vars[‘action’] ) { this.twitter_player = ‘true’; }

if ( ‘undefined’ != typeof go_alex_briefing.get_vars[‘auto_play’] ) { this.auto_play = go_alex_briefing.get_vars[‘auto_play’]; }

if ( ‘true’ == this.twitter_player ) { $( ‘#top-header’ ).remove(); }

var $amplitude_args = { ‘songs’: [{“name”:”Episode 13: A Conversation with Bryan Catanzaro”,”artist”:”Byron Reese”,”album”:”Voices in AI”,”url”:”https:\/\/voicesinai.s3.amazonaws.com\/2017-10-16-(00-54-18)-bryan-catanzaro.mp3″,”live”:false,”cover_art_url”:”https:\/\/voicesinai.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2017\/10\/voices-headshot-card-5.jpg”}], ‘default_album_art’: ‘http://ift.tt/2yEaCKF’ };

if ( ‘true’ == this.auto_play ) { $amplitude_args.autoplay = true; }

Amplitude.init( $amplitude_args );

this.watch_controls(); };

go_alex_briefing.watch_controls = function() { $( ‘#small-player’ ).hover( function() { $( ‘#small-player-middle-controls’ ).show(); $( ‘#small-player-middle-meta’ ).hide(); }, function() { $( ‘#small-player-middle-controls’ ).hide(); $( ‘#small-player-middle-meta’ ).show();

});

$( ‘#top-header’ ).hover(function(){ $( ‘#top-header’ ).show(); $( ‘#small-player’ ).show(); }, function(){

});

$( ‘#small-player-toggle’ ).click(function(){ $( ‘.hidden-on-collapse’ ).show(); $( ‘.hidden-on-expanded’ ).hide(); /* Is expanded */ go_alex_briefing.expanded = true; });

$(‘#top-header-toggle’).click(function(){ $( ‘.hidden-on-collapse’ ).hide(); $( ‘.hidden-on-expanded’ ).show(); /* Is collapsed */ go_alex_briefing.expanded = false; });

// We’re hacking it a bit so it works the way we want $( ‘#small-player-toggle’ ).click(); $( ‘#top-header-toggle’ ).hide(); };

go_alex_briefing.build_get_vars = function() { if( document.location.toString().indexOf( ‘?’ ) !== -1 ) {

var query = document.location .toString() // get the query string .replace(/^.*?\?/, ”) // and remove any existing hash string (thanks, @vrijdenker) .replace(/#.*$/, ”) .split(‘&’);

for( var i=0, l=query.length; i<l; i++ ) { var aux = decodeURIComponent( query[i] ).split( '=' ); this.get_vars[ aux[0] ] = aux[1]; } } };

$( function() { go_alex_briefing.init(); }); })( jQuery );

.go-alexa-briefing-player { margin-bottom: 3rem; margin-right: 0; float: none; }

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#top-header { width: 100%; max-width: 1000px; min-height: 50px; }

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#top-large-album { width: 100%; max-width: 1000px; height: auto; margin-right: auto; margin-left: auto; z-index: 0; margin-top: 50px; }

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#top-large-album img#large-album-art { width: 100%; height: auto; border-radius: 0; }

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player { margin-top: 38px; width: 100%; max-width: 1000px; }

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player div#small-player-full-bottom-info { width: 90%; text-align: center; }

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player div#small-player-full-bottom-info div#song-time-visualization-large { width: 75%; }

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player-full-bottom { background-color: #f2f2f2; border-bottom-left-radius: 5px; border-bottom-right-radius: 5px; height: 57px; }

Voices in AI

Visit VoicesInAI.com to access the podcast, or subscribe now:

iTunes

Play

Stitcher

RSS

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed { font-size: 1.4rem; background: url(http://ift.tt/2g4q8sx) black; background-position: center; background-size: cover; color: white; padding: 1rem 1.5rem; font-weight: 200; text-transform: uppercase; margin-bottom: 1.5rem; }

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed:last-of-type { margin-bottom: 0; }

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed .logo { margin-top: .25rem; display: block; background: url(http://ift.tt/2g3SzGL) center left no-repeat; background-size: contain; width: 100%; padding-bottom: 30%; text-indent: -9999rem; margin-bottom: 1.5rem }

@media (min-width: 960px) { .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed .logo { width: 262px; height: 90px; float: left; margin-right: 1.5rem; margin-bottom: 0; padding-bottom: 0; } }

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed a:link, .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed a:visited { color: #FF6B00; }

.voice-in-ai-link-back a:hover { color: #ff4f00; }

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links { margin-left: 0 !important; margin-right: 0 !important; margin-bottom: 0.25rem; }

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:link, .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:visited { background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.77); }

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:hover { background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.63); }

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links .stitcher .stitcher-logo { display: inline; width: auto; fill: currentColor; height: 1em; margin-bottom: -.15em; }

Byron Reese: This is “Voices in AI” brought to you by Gigaom. I’m Byron Reese. Today, our guest is Bryan Catanzaro. He is the head of Applied AI Research at NVIDIA. He has a BS in computer science and Russian from BYU, an MS in electrical engineering from BYU, and a PhD in both electrical engineering and computer science from UC Berkeley. Welcome to the show, Bryan.

Bryan Catanzaro: Thanks. It’s great to be here.

Let’s start off with my favorite opening question. What is artificial intelligence?

It’s such a great question. I like to think about artificial intelligence as making tools that can perform intellectual work. Hopefully, those are useful tools that can help people be more productive in the things that they need to do. There’s a lot of different ways of thinking about artificial intelligence, and maybe the way that I’m talking about it is a little bit more narrow, but I think it’s also a little bit more connected with why artificial intelligence is changing so many companies and so many things about the way that we do things in the world economy today is because it actually is a practical thing that helps people be more productive in their work. We’ve been able to create industrialized societies with a lot of mechanization that help people do physical work. Artificial intelligence is making tools that help people do intellectual work.

I ask you what artificial intelligence is, and you said it’s doing intellectual work. That’s sort of using the word to define it, isn’t it? What is that? What is intelligence?

Yeah, wow…I’m not a philosopher, so I actually don’t have like a…

Let me try a different tact. Is it artificial in the sense that it isn’t really intelligent and it’s just pretending to be, or is it really smart? Is it actually intelligent and we just call it artificial because we built it?

I really liked this idea from Yuval Harari that I read a while back where he said there’s the difference between intelligence and sentience, where intelligence is more about the capacity to do things and sentience is more about being self-aware and being able to reason in the way that human beings reason. My belief is that we’re building increasingly intelligent systems that can perform what I would call intellectual work. Things about understanding data, understanding the world around us that we can measure with sensors like video cameras or audio or that we can write down in text, or record in some form. The process of interpreting that data and making decisions about what it means, that’s intellectual work, and that’s something that we can create machines to be more and more intelligent at. I think the definitions of artificial intelligence that move more towards consciousness and sentience, I think we’re a lot farther away from that as a community. There are definitely people that are super excited about making generally intelligent machines, but I think that’s farther away and I don’t know how to define what general intelligence is well enough to start working on that problem myself. My work focuses mostly on practical things—helping computers understand data and make decisions about it.

Fair enough. I’ll only ask you one more question along those lines. I guess even down in narrow AI, though, if I had a sprinkler that comes on when my grass gets dry, it’s responding to its environment. Is that an AI?

I’d say it’s a very small form of AI. You could have a very smart sprinkler that was better than any person at figuring out when the grass needed to be watered. It could take into account all sorts of sensor data. It could take into account historical information. It might actually be more intelligent at figuring out how to irrigate than a human would be. And that’s a very narrow form of intelligence, but it’s a useful one. So yeah, I do think that could be considered a form of intelligence. Now it’s not philosophizing about the nature of irrigation and its harm on the planet or the history of human interventions on the world, or anything like that. So it’s very narrow, but it’s useful, and it is intelligent in its own way.

Fair enough. I do want to talk about AGI in a little while. I have some questions around…We’ll come to that in just a moment. Just in the narrow AI world, just in your world of using data and computers to solve problems, if somebody said, “Bryan, what is the state-of-the-art? Where are we at in AI? Is this the beginning and you ‘ain’t seen nothing yet’? Or are we really doing a lot of cool things, and we are well underway to mastering that world?”

I think we’re just at the beginning. We’ve seen so much progress over the past few years. It’s been really quite astonishing, the kind of progress we’ve seen in many different domains. It all started out with image recognition and speech recognition, but it’s gone a long way from there. A lot of the products that we interact with on a daily basis over the internet are using AI, and they are providing value to us. They provide our social media feeds, they provide recommendations and maps, they provide conversational interfaces like Siri or Android Assistant. All of those things are powered by AI and they are definitely providing value, but we’re still just at the beginning. There are so many things we don’t know yet how to do and so many underexplored problems to look at. So I believe we’ll continue to see applications of AI come up in new places for quite a while to come.

If I took a little statuette of a falcon, let’s say it’s a foot tall, and I showed it to you, and then I showed you some photographs, and said, “Spot the falcon.” And half the time it’s sticking halfway behind a tree, half the time it’s underwater; one time it’s got peanut butter smeared on it. A person can do that really well, but computers are far away from that. Is that an example of us being really good at transfer learning? We’re used to knowing what things with peanut butter on them look like? What is it that people are doing that computers are having a hard time to do there?

I believe that people have evolved, over a very long period of time, to operate on planet Earth with the sensors that we have. So we have a lot of built-in knowledge that tells us how to process the sensors that we have and models the world. A lot of it is instinctual, and some of it is learned. I have young children, like a year-old or so. They spend an awful lot of time just repetitively probing the world to see how it’s going to react when they do things, like pushing on a string, or a ball, and they do it over and over again because I think they’re trying to build up their models about the world. We have actually very sophisticated models of the world that maybe we take for granted sometimes because everyone seems to get them so easily. It’s not something that you have to learn in school. But these models are actually quite useful, and they’re more sophisticated than – and more general than – the models that we currently can build with today’s AI technology.

To your question about transfer learning, I feel like we’re really good at transfer learning within the domain of things that our eyes can see on planet Earth. There are probably a lot of situations where an AI would be better at transfer learning. Might actually have fewer assumptions baked in about how the world is structured, how objects look, what kind of composition of objects is actually permissible. I guess I’m just trying to say we shouldn’t forget that we come with a lot of context. That’s instinctual, and we use that, and it’s very sophisticated.

Do you take from that that we ought to learn how to embody an AI and just let it wander around the world, bumping into things and poking at them and all of that? Is that what you’re saying? How do we overcome that?

It’s an interesting question you note. I’m not personally working on trying to build artificial general intelligence, but it will be interesting for those people that are working on it to see what kind of childhood is necessary for an AI. I do think that childhood is a really important part of developing human intelligence, and plays a really important part of developing human intelligence because it helps us build and calibrate these models of how the world works, which then we apply to all sorts of things like your question of the falcon statue. Will computers need things like that? It’s possible. We’ll have to see. I think one of the things that’s different about computers is that they’re a lot better at transmitting information identically, so it may be the kind of thing that we can train once, and then just use repeatedly – as opposed to people, where the process of replicating a person is time-consuming and not exact.

But that transfer learning problem isn’t really an AGI problem at all, though. Right? We’ve taught a computer to recognize a cat, by giving it a gazillion images of a cat. But if we want to teach it how to recognize a bird, we have to start over, don’t we?

I don’t think we generally start over. I think most of the time if people wanted to create a new classifier, they would use transfer learning from an existing classifier that had been trained on a wide variety of different object types. It’s actually not very hard to do that, and people do that successfully all the time. So at least for image recognition, I think transfer learning works pretty well. For other kinds of domains, they can be a little bit more challenging. But at least for image recognition, we’ve been able to find a set of higher-level features that are very useful in discriminating between all sorts of different kinds of objects, even objects that we haven’t seen before.

What about audio? Because I’m talking to you now and I’m snapping my fingers. You don’t have any trouble continuing to hear me, but a computer trips over that. What do you think is going on in people’s minds? Why are we good at that, do you think? To get back to your point about we live on Earth, it’s one of those Earth things we do. But as a general rule, how do we teach that to a computer? Is that the same as teaching it to see something, as to teach it to hear something?

I think it’s similar. The best speech recognition accuracies come from systems that have been trained on huge amounts of data, and there does seem to be a relationship that the more data we can train a model on, the better the accuracy gets. We haven’t seen the end of that yet. I’m pretty excited about the prospects of being able to teach computers to continually understand audio, better and better. However, I wanted to point out, humans, this is kind of our superpower: conversation and communication. You watch birds flying in a flock, and the birds can all change direction instantaneously, and the whole flock just moves, and you’re like, “How do you do that and not run into each other?” They have a lot of built-in machinery that allows them to flock together. Humans have a lot of built-in machinery for conversation and for understanding spoken language. The pathways for speaking and the pathways for hearing evolve together, so they’re really well-matched.

With computers trying to understand audio, we haven’t gotten to that point yet. I remember some of the experiments that I’ve done in the past with speech recognition, that the recognition performance was very sensitive to compression artifacts that were actually not audible to humans. We could actually take a recording, like this one, and recompress it in a way that sounded identical to a person, and observe a measurable difference in the recognition accuracy of our model. That was a little disconcerting because we’re trying to train the model to be invariant to all the things that humans are invariant to, but it’s actually quite hard to do that. We certainly haven’t achieved that yet. Often, our models are still what we would call “overfitting”, where they’re paying attention to a lot of details that help it perform the tasks that we’re asking it to perform, but they’re not actually helpful to solving the fundamental tasks that we’re trying to perform. And we’re continually trying to improve our understanding of the tasks that we’re solving so that we can avoid this, but we’ve still got more work to do.

My standard question when I’m put in front of a chatbot or one of the devices that sits on everybody’s desktop, I can’t say them out loud because they’ll start talking to me right now, but the question I always ask is “What is bigger, a nickel or the sun?” To date, nothing has ever been able to answer that question. It doesn’t know how sun is spelled. “Whose son? The sun? Nickel? That’s actually a coin.” All of that. What all do we have to get good at, for the computer to answer that question? Run me down the litany of all the things we can’t do, or that we’re not doing well yet, because there’s no system I’ve ever tried that answered that correctly.

I think one of the things is that we’re typically not building chat systems to answer trivia questions just like that. I think if we were building a special-purpose trivia system for questions like that, we probably could answer it. IBM Watson did pretty well on Jeopardy, because it was trained to answer questions like that. I think we definitely have the databases, the knowledge bases, to answer questions like that. The problem is that kind of a question is really outside of the domain of most of the personal assistants that are being built as products today because honestly, trivia bots are fun, but they’re not as useful as a thing that can set a timer, or check the weather, or play a song. So those are mostly the things that those systems are focused on.