#i also went to the buddhist temple and rang the bell three times... but they don't allow pictures

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

being outside surrounded by happy strangers celebrating a cultural holiday was definitely a better use of my day than staying in bed... plus I got this cool pinwheel

#chatter#i also went to the buddhist temple and rang the bell three times... but they don't allow pictures

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

a/n: this is the first installment(?) of the Nori brain rot from ages ago w/a Studio Ghibli vibe, idk man this just happened word count: 2.2k tags: post!Shibuya arc, possible spoilers, blood, violence, cursing(?), heavily Hoizer inspired, kinda edited character(s): Noritoshi Kamo, fem!sorcerer reader pt ll

Curses stank.

In a metaphorical sense yes. But also in a literal sense for you.

These twisted beings permeated your senses like a rot that you could never rid. Unless exorcised they stuck around in your nostril for days. Each one a different smell but all of them stuck in your craw all the same.

Beasts of rancid nature in behaviors and looks. Nothing more than to be exorcised by sorcerers. You learned quickly that exorcising the curses was no different than taking out week old trash.

What you hadn’t planned on was someone doing more than dumping trash on the world. Whatever had happened. Suddenly you were faced with more than just dutiful tasks of keeping non sorcerers safe. A monsoon of trash had been dumped not only on you. But every human in this world.

Your nostrils burned. And you couldn’t be rid of these things quick enough. Each one you exorcised only meant two or three popped up in their place. Never ending. You couldn’t stomach this smell though. It wouldn’t kill you before you got a breath of fresh air.

Glancing around you take a deep breath. Mountain air on the outskirts of Kyoto during this time of year always meant a refreshing break from the city stank. What you smelled wasn’t refreshing. It was that same vile smell you could clearly recall.

A curse. One that was close too.

To thread carefully was to perhaps save your life. Every aspect of daily life ripped from you. As well of millions of others. You had done your part to try and protect those around you. Soon finding it in slight vain as you sought out some place to find your own breath of fresh air in this madness.

‘It’s close....I feel like I’m gonna hurl.’ Thoughts toying with where the curse might have hidden itself. You keep a firm grip on your hilt with every intent to draw it the second the creature made the mistake of slipping up.

Where you could smell it lurking. There was something else. Almost metallic in scent. You ignored it though. Nothing over powered the scent of a curse. You longed for just the sight of these things. Told over and over again how handy it was to have more than one sense open to curses. Each and every time you took a whiff of one, it made you wish nothing more than to just be able to see these creatures instead of smell them as well.

‘Wait-’ Every alarm in your body went off. Snapping around you couldn’t smell the rancid putridness of the curse anymore. That same metallic scent hung around though. You couldn’t identify it. It was something you’d never smelt before but also so familiar.

Each hair on the back of your neck rose. This was an old deserted Buddhist temple. No one should have been here except you and the curse ransacking the place. A safe haven or so you thought. When your instinct told you to step behind one of the structural beams. You were suddenly glad you did.

Mere inches from your face, the gust of an arrow whistled past you. Weapons were not used by curses. Now you understood. That smell was human.

Quick to defend yourself, with sword drawn, you didn’t expect the same arrow to make a hard one eighty back in the direction you were. No wooden pillar to save you now. You raise your sword just quick enough to sheer the object in half. Rendering what ever power it was imbued with useless. As it had sped past you though the faint smell of iron suddenly became strong. Whatever it was from had a source. Likely human.

Not ready to give up your ideal hiding place to some interloper. You take only a second to focus on the unfamiliar smell. Faint. And not like a curse. There was something towards the back of the temple though that hinted that they were lurking where you couldn’t see them.

With an idea of where the attack would come from. When another arrow came flying by you from a faceless source, you were ready. Smacking it down before the enchanted weapon could turn on you like the first had. This time though you’d seen what angle the projectile was fired from.

‘Gotcha,’ No shortage of ways around a deteriorated temple like this. You duck down through a few broken beams and make your way up to where the attack came from.

Expecting to have but a lowly sniper sitting with no way to guard themselves. You find no one. But the scent lingered. Scrutinizing it closer you decided maybe to use a different sense, “...Hey, I know you’re not a curse! Neither am I! Maybe if you just-” Words cut off by another arrow whizzing past you. There was nothing ruder than being interrupted. Glowering in the direction that the arrow came from now you tightened you grip on your sword, “Ok! I get it- Strangers we might not-”

Another arrow. This time too close to your head for comfort. You lost your patience with the third one.

Recklessly charging towards the assailant was clearly enough to throw their game off track. Swinging your weapon before seeing what it was to lie before you. It was a surprise when your blade met with the dull thud of the wooden limb of a bow.

“What the-” You attack deflected for the moment being. Your first instinct is to jump back from whoever deflected your attack. In close enough range you thought you had the upper hand to avoid the bow. But that was purely lazy thinking on your part as the cause of the stank of iron became clear.

“Slicing exorcism!” This nobody who reeked of iron shot what looked to be a shuriken made of blood at you.

No time to be disgusted. An overwhelming scent of blood made it apparent what you’d been smelling. It wasn’t a simple metal. It was blood.

“Oh- Oh!” You raise your blade up in the nick of time to just get the splatter of cold liquid on your cheeks. Disgusted in passing you have no time to dwell as the stranger before you makes to dart away. With their head of dark hair in your line of sight, you weren’t ready to try and re-find them once again in this maze of debris.

Lurching forward you feel the upper hand stall when they stopped your attack once more with the brute of their bow. Clear view of them now. The man who’d clearly fired the arrows was all but composed when shaking off your attack. No way to not suspect another sorcerer caught up in this giant trash heap of curse attacks. You still have no time to play nice when they hurl another blood conjured weapon at you.

In such suddenness you are less lucky than you have been. This one catching your cheek and causing a sting to spread throughout the skin of your face. Fed up with this game you don’t care if he’s a sorcerer or not. This was a one for all situation now that you intended to win.

Firm foot hold found. You realize the man has cornered himself at this point. Range attacks out of the question. Undoubtedly giving you the upper hand now. With a hefty swing of your sword and the first time you’d channeled any energy into at all. You bring it down like a guillotine. Ready to strike flesh. Instead the snap of the bow is your first sign of an upper hand.

All but trash the man throws it aside but too slowly. You’re on him before the range attacker can pull that weird blood trick again. Slight intent to kill as if he were a curse. You swipe your foot down and knock him down to the temple floor with a hard thud.

You waste no time between the moment his head hit the ground and your above him. Tip of your blade pressed to his neck. One breath too deep from him and the sharp tip would pierce his pale skin. Eyes fixated down on him you realize in the moments after your adrenaline fades that he’s staring right up at you.

Sharp tongue your words come out curt only to be interruped right away, “Who are-”

“Another sorcerer-” His eyes open from the slits they’d remained in the skirmish, “What are you doing here? How did you-”

“I get to ask the questions!” You snarl, jabbing his throat with your sword just enough to watch a crimson bead peak from under the tip of your weapon, “You attacked me, what are you doing up here? Why were you-”

“...you’re so pretty-” Suddenly his eyes open wide realizing what he said, “Wait I didn’t-”

“Shut up or I’ll cut your throat out!” Your sword pressing uncomfortably into the side of his neck now, “I asked you a question! Why are you up here!?”

“Kamo-”

“What? What are you-”

“Kamo family!” He quickly sputtered, “Head of the Kamo family!”

The name rang a bell somewhere in your frazzled brain.

“I’m the head-” He suddenly registered really the blade to his neck, “I’m looking for stragglers-”

“In an abandoned temple?” You weren’t buying it.

“My people live just down the hill,” He spoke earnestly, “I had to keep the stragglers safe when the curses released from their seals in the keep. Some where up here but-”

“I killed them,” You glared down at him, “I killed all but the one you shot. How long were you up here? Were you following me?”

A shake of his head even as he stared at the glimmer of your sword, “No. I was looking for anyone who came up here. I didn’t expect to find another sorcerer. I felt your cursed energy and assumed you were a curse.”

Eyes narrowing you didn’t like the sound of something so simple to this pretty face, “...I don’t believe you. Give me a reason I shouldn’t kill you right now or else-”

“Noritoshi-” He blurted out, “Noritoshi Kamo. Head of the Kamo family. I can give you some place safe to stay. I don’t understand what’s going on but-”

You lift the blade from his throat. Something about the diligent tone in his voice. Like he’d introduced himself like that a million times. You could kill him but it seemed a waste. Weapon retracted but no offer to help him up. You stand above him with a confounded glare, “...do you know what’s happening?”

His head shook and your stomach dropped. Noritoshi didn’t get up. Only propping himself up slightly when he realized the back of his head was thumping from the impact, “....A special grade curse released a powerful seal in Shibuya about two weeks ago...I saw but....” His face became somber and he shook his head once again, “...I don’t know what’s been going on. I just know things are in disarray and it’s my duty to protect my people.”

Once more you were skeptical but with how little rest you’d gotten in the past few days due to the tremendous increase in curses. This man’s words seemed as solid as any other theory you’d heard. More so than the plea of non sorcerer’s you listened to day in and day out about the end of times.

“...Has the Jujutsu elders said anything?” You step off him completely. If he was speaking the truth maybe he knew what was going on as an actual heir to one of the clans.

Noritoshi looked up at you a moment longer, “No...there’s been a wide emergency notice to do what you can but our numbers....” He grew quiet, “...as many sorcerers seem to be dying as the rest of Japan.”

Perhaps the end of times were coming. You grip your sword hilt tight and take a deep breath, “....seems a angel of death is coming then whether we like it or not.”

“You’re a sorcerer.” He began to get to his feet, “Please, come with me. If anything to stay away from here. There is a grave yard on the other side of the thicket. More curses will come. No one should be here even as a sorcerer yourself.”

First hand you’d seen the influx he spoke of. From every direction. While out of the city provided some safety you knew that this place left you as vulnerable as any other if you stayed alone. With no words to be spoken of from the elders. And an age of curses threatening to crowd out humans. Like a trash pile reaching it’s capacity. You didn’t see much choice in this one.

“...I will kill you if I find out you’re lying to me.” Voice firm without breaking eye contact with him as you sheath your sword, “I smell one curse in this safe space of yours and I’ll-”

“Kill me, yes,” Noritoshi nodded with both busted ends of his bow in his hands as he looked on at you, “I am not lying but if you see fit, I’ll accept you as my angel of death then.”

a/n: I have one wine cooler in me as I finish this. This might be a multi part if the inspiration finds me. Anyways, um, yeah! This is an old idea coming so pls let me know if you liked it!

#jujutsu kaisen#jjk#kamo noritoshi#noritoshi x reader#noritoshi kamo x reader#jjk noritoshi#jjk x reader#jujutsu kaisen x reader

238 notes

·

View notes

Text

Akemashite Omedetou Gozaimasu!

New Years in Japan is an absolutely magical time of year, when the whole country shuts down and enters a period of reflection and celebration as one year ends and a new one begins. Businesses close, people travel to their hometowns to spend time with their parents and extended family, and family traditions bridge the Japanese culture of today back across the generations.

On New Years Eve, the celebrations begin. Many Japanese families will stay up until midnight, eating New Years Soba (toshikoshi soba) and mikan oranges, while watching annual competition shows such as the Red and White Song Battle! (Kouhaku Uta Gassen) or the annual Punishment Game comedy show (batsu game). Shortly before midnight, however, the shows conclude, and NHK presents footage of shrines and temples all over Japan, waiting for the midnight ceremonies. At Buddhist temples, the large temple bell is rung 108 times, once for each of the worldly desires central to Buddhism.

[pictured below: the inner courtyard of a Buddhist temple. A tree in the center is still showing the oranges and reds of autumn, and traditional Japanese buildings surround the tree.]

On New Years Day, families celebrate by eating traditional symbolic foods, much like they do in the rest of the world. In Virginia, for example, my family eats black eyed peas, collard greens, cornbread, and ham, and each item has a specific symbolism for the new year. Japan is much the same-- each item of the New Year’s Meal (Osechi Ryouri) is symbolic of things like longevity, luck, good relationships, and prosperity.

The house is decorated with traditional plant decorations meant to bring good luck, harmony, and safety over the coming year. Often included are items like pine and bamboo (kadomatsu), straw ropes (shimenawa and shimekazari), and special sacred rice cakes (kagamimochi). These decorations are placed around the home, with rituals that define when and where they are placed, as well as when and how they are removed.

[pictured below: A small kagamimochi decoration, consisting of two stacked mochi rice cakes and a small figure of a cow on top symbolizing 2021, year of the ox]

Afterwards, usually on New Years Day (but often on the 2nd or 3rd of January), the traditional first shrine visit (hatsumode) is performed. These three days are some of the busiest days of the year for the Shinto Shrines in Japan, as visitors come to pray for the new year, return their old charms and amulets (omamori) from the prior year for disposal, and receive their fortunes for the oncoming year.

[pictured below: The entrance to a Shinto shrine. A torii gate stands in the center with snowy stone lanterns at its base, and snow-covered stone steps rising behind it, a bamboo forest on both sides. A family climbs the steps in the background.]

For my own hatsumode visit, a Japanese friend and I went to Hanyu Gokoku Hachimangu in Oyabe. After climbing approximately eight million stairs, we went to the main shrine building, where I tossed a coin into the offering box and paid my respects to the kami. Then, we moved to the outdoor tents, where I purchased my omamori for 2021. Since my theme for the year is “belonging” (I want to focus on putting in the effort to make a home for myself in Japan), I chose a Sakura blossom charm that will attract good luck and happiness.

[pictured below: two examples of omamori amulets. The amulet on the left is made to look like a miniature pink backpack of the sort that Japanese elemetary school students carry, and is a charm for success in studies and safety in traffic. The amulet on the right is a bedazzled pink sakura blossom, and is a charm for good luck and happiness.]

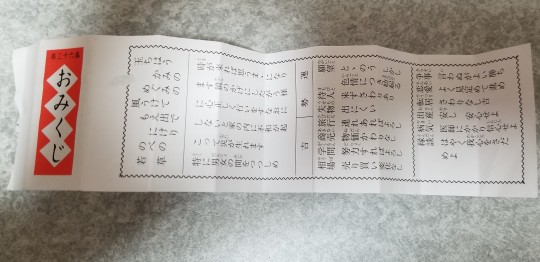

After purchasing my omamori, I visited the omikuji tent to learn my fortune for 2021. Omikuji fortunes are available year-round, but are a very important New Years tradition, providing guidance for the year ahead. They are pre-printed and piled in a large box, where the recipient draws their fortune from the pile after droppng a donation into the coin box.

[pictured below: an unopened omikuji fortune]

The contents of an omikuji, of course, cannot be determined before the fortune is opened. Generally, however, the overall fortunes range from extremely bad luck to extremely good luck, with at least twelve degrees of luckiness in between. In addition to your overall fortune, an omikuji will also include your luck pertaining to various categories of life, such as career, love, health, finances, major life events, babies, and more.

[pictured below: An opened omikuji. This one includes, from left to right, a section of a traditional poem, overall advice, the main fortune (this one is ‘blessing’, which is so-so but not bad luck), then fortunes and advice for different categories of life.]

Once you have read your omikuji, the traditional next step is to tie the fortune at the shrine, to prevent your bad luck from following you home, and to leave your good luck in the hands of the gods. This particular shrine provided a bamboo sapling to tie omikuji onto, which will later be burned along with all of the attached omikuji, to burn away the bad luck and allow the visitors’ wishes to reach the gods. After tying up our omikuji, we headed out of the tent, and on to our next stop.

[pictured below: a branch of bamboo held up in a red stand, with folded omikuji tied in nearly every available spot.]

We were nearly ready to leave the shrine when I spotted a tent of street food. I am always, always down for almost anything if it is on a stick, so we bought ourselves an order of Mitarashi Dango-- grilled mochi balls slathered in soy sauce, and impaled on sticks. This traditional street food is very popular year-round, and was an excellent pick-me-up after climbing (and then descending) all of those steps!

[pictured below: a tray of Mitarashi dango]

Finally, we wrapped up hatsumode and headed home, the new year rituals complete. Now it is time for contemplation and preparation, before the world starts up again on Monday-- and my heated table (kotatsu) is calling my name.

#japan#japanese#japanese new year#new year#happy new year#japanese culture#japanese food#shinto#shinto shrine#traditional japan#buddhist temple#new years tradition

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Friday, February 7 / 2020 Today in Kl was for sure unexpected, fascinating, and inconvenient! After breakfast, we took a train to Batu Caves. I didn't know where to look. Crowds of Hindus dressed in yellow with trays of blessings and pots of milk (symbols of abundance) walking towards the caves wasn't just colourful and beautiful. It showed how strong their belief was! As we were getting closer to the place, the music and drumming was getting louder, and I saw a man, hooked from the skin of his back to a series of chains pulling a wagon all decorated with flowers. Another man walked by with dozens of fishhooks on his body, each one suspending a heavy bell and these rang as he walked. I couldn't believe my eyes! Incredible! In the distance, there was a giant gold Hindu deity beside the many stairs that led up to the cave. I saw another man with weights hooked to his back by spikes as a symbol of penance. Several others were carrying heavy ornate frames called Kavadi and a few of these were pierced throughout their faces. All of this weight was carried up hundreds of steep steps with teams of supporters chanting and fanning the overheating carriers' bodies. This was Thaipusam: an annual festival that falls on a full moon and it is tribute to the Hindu god of war. It was spectacular and colourful. We were planning to spend most of our day there, take photos and watch people. Unfortunately, we had to cut it short. Simon was targeted by three professional pickpockets that got all of his credit cards and about $100 in local currency. Simon said this was the cost of "a lesson well learned!" We spent two hours filling out crime reports in the police office. By the time we got back to our hotel and began reporting the cards stolen, they had cracked the PIN code on one card and run up a $12000 bill of jewelry and electronics. The other card PINs were not cracked. Fortunately, we will not be responsible for these fraudulent purchases. After eating, we went for a walk around the local area known as Brickfields (when KL was a mining town, this was the brick manufacturing area). We saw the diversity of religions (Christian, Buddhist, Sikh, Muslim, and Hindu) worshipping at various churches,mosques, and temples. We also stopped to enjoy a lion dance near several Chinese restaurants, but we got a little too close to the dancers at the end, while taking close up pictures, and failed to notice the massive amount of firecrackers they set off beside us. Thank god I was still half deaf.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

New Post has been published on https://fitnesshealthyoga.com/how-a-daily-meditation-practice-helps-you-find-trust/

How a Daily Meditation Practice Helps You Find Trust

To see yourself is the heart of what a spiritual discipline like meditation is all about.

After meditating with my first meditation teacher, Arvis, for some time, I decided to do a weeklong silent Zen meditation retreat. Arvis said, “I feel good about a teacher named Jakusho Kwong up at Sonoma Mountain Zen Center. Maybe that would be a good place for you to go.” I was excited to experience an authentic retreat in a Zen Buddhist temple with all the accoutrements — the bells, the robes, the rituals, the whole thing.

I got there in the late afternoon, and the retreat was scheduled to start in the early evening. After we had dinner, we went into the Zendo for the first meditation session. It was a very formal place, and I had no idea what the etiquette was. There was minimal instruction, so I learned what I was supposed to be doing by watching other people, which heightened my awareness right away. I sat down on my cushion with all my gleeful anticipation about this experience as the temple bell was struck three times to begin the period of meditation.

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

As soon as that bell rang, adrenaline flooded my body. It was not fear, but my whole system went into fight-or-flight mode. All I could think was, How do I get out of here? Let me out of here! which is silly because five seconds earlier I was thrilled about being there.

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

Fortunately, a small, quiet voice inside me said, You have no idea how important this is. You must stay. So even though I had adrenaline rushes twenty-four hours a day for five days and nights in a row, I did not sleep throughout the entire retreat, and I contemplated leaving many times, I managed to hang in there — barely — and finish. Not an auspicious beginning for a future spiritual teacher, but that is what happened. I never knew exactly why I had that reaction, but I have a hunch. When you undertake a retreat like that, something deep within you knows, Oh, boy, the jig is up now. This is not make-believe. This is the real thing. Something in me knew that this was going to be a complete life reorientation. I did not realize this consciously, but unconsciously my ego reacted as if threatened: This is it. This guy is considering the nature of his own being as far as the egoic impulse running the rest of life.

In some ways, my first retreat was a disaster. The only thing that got me through was a mantra I came up with on the second day. Thousands of times over those five nights and days, I said to myself: I will never, ever, ever do this again. That was my big spiritual mantra!

One of the things that impressed me during that retreat was that Kwong — the roshi, or teacher — gave a talk each day, and that talk was my respite because I got to sit and listen and be entertained. It was a relief from the bone-jarring meditation, the never-ending silence, and the pain in my knees and back. Kwong had recently returned from a trip to India that had a huge impact on him. I could tell because as he was recounting stories about his trip, tears streamed down his cheeks and dripped off the bottom of his chin.

See also Try This Durga-Inspired Guided Meditation for Strength

One story especially touched me. Kwong was walking on a dirt road through an impoverished area. There were some kids playing a game with a ball and a stick out in the middle of the road. One kid stood apart from the group, as if ostracized. This boy was watching the kids play and had a sad look on his face. He had a cleft palate, so his upper lip was severely deformed. Kwong walked up to the boy, but they did not speak the same language, so he did not know what to say. There was a moment of indecision, and then Kwong took the boy’s hand in his and with his other hand reached into his pocket and pulled out some money. He pointed to a little shop that sold ice cream and gave the money to the boy. I thought it was a sweet way of giving a little comfort and acknowledging this poor kid’s existence, his loneliness.

As Kwong did this, he gestured to the group of children that seemed to have rejected the boy as if to say, “Go get them and buy them ice cream.” He had given the child enough money to buy treats for all the kids. The boy waved to them and pointed toward the ice cream shop, and all the children joined this one kid who had been lonely and sad. Suddenly he was the hero! He had money and was buying ice cream for everybody. The kids were laughing and talking with him. He was included in their group.

Kwong sat in full lotus position on his cushion in his beautiful brown teacher’s robes and told this story in a resonant, soft voice, deeply touched by the poverty that he saw and by the loneliness of that child. He never hid his tears, and he never seemed embarrassed by his emotion. Watching another man embody this juxtaposition of great strength and tenderness taught me more about true masculinity than anything else in my life. Hearing him speak with such fearlessness was extraordinary. For a young, aspiring Zen student, to have this be my first encounter with a Zen master was a tremendous stroke of good luck and grace, especially since during this whole retreat, except for the talks, I was hanging on by a thread. I continued to study with Kwong, did some retreats with him over the years, and appreciated his great wisdom, but I never again saw him in the state he was in on that first retreat. His openness and dignity were a powerful teaching — it was like being bathed in grace.

Since then I have attended and led hundreds of retreats, but I still look back on that first one with Kwong as both the absolute worst and absolute best in my life. I did not know how powerfully it had affected me until months later. Staying with whatever arose for me despite being flooded with adrenaline, sitting with it in a raw way through all those hours of meditation instead of running away, was profound. When you are having that experience, when you are being pushed to your limit, you do not think of it as grace, but the real grace was that I was in that environment. I was in a place where I could not go anywhere, where I could not turn on the TV or listen to the radio or grab a book or enter a discussion. I had to face the entirety of my experience. Afterward, when I tried to describe the retreat to people, I would end up in tears — not tears of sadness or even of joy, but of depth. I had touched upon something that was so meaningful, vital, and important that it opened my heart.

See also This 6-Minute Sound Bath Is About to Change Your Day for the Better

Meditation Helps You Feel Your Feelings

As we go through life, we eventually have enough experience to see that sometimes profound difficulty can also be profoundly heart opening. When you are in a tough position, when you are facing something hard, when you feel challenged, when you feel like you are at your edge, it is a gift to have the willingness to stop, to sit with those moments, and not to look for the quick, easy resolution for that feeling. It is a kind of grace to be able and willing to open yourself entirely to the experience of challenge, of difficulty, and of insecurity.

There is light grace, and there is dark grace. Light grace is when you have a revelation — when you have insights. Awakening is a light grace; it is like the sun coming out from behind the clouds. The heart opens, and old identities fall away. Then there is dark grace, like what I had on that retreat. I do not mean “dark” in the sense of sinister or evil, but “dark” in the sense of traveling through the darkness looking for light. You cannot see the way through whatever you are experiencing and whatever the challenge is. One of the most amazing things that daily meditation has taught me over many years is to have the wisdom and grace to quietly and silently be with whatever presents itself, whatever is there, without looking for a solution or an explanation.

To see yourself is the heart of what a spiritual discipline like meditation is all about. When people come on retreat with me, we meditate for five or six periods a day. The idea of meditation is not necessarily to get good at it — whatever your definition may be of being “good” at meditation — but the most important thing, the useful thing, the reason we are meditating is so that we encounter ourselves. If you are not using your meditation to hide from your experience or to transcend it or to concentrate your way out of it, if you are being quietly present, meditation forces honesty. It is an extraordinarily truthful way to experience yourself in that moment. This willingness to encounter yourself is vitally important. It is a key to spiritual life and to awakening: being present for whatever is. Sometimes “whatever is” is mundane; sometimes it is full of light, grace, and insight; and sometimes it begins as a dark grace, where we do not know where we are going or how to get through it, and then suddenly there is light.

One of the nice things about meditation is that when we sit with these moments as they arise, we start to trust in them and in the dark grace. We realize that it is in feeling lost that our true nature finds itself. In meditation we encounter ourselves, and it elicits a real honesty if we are ready for it. You can read about things forever, you can listen to talks forever, and you can assume that you understand or that you have got it, but if you can be with yourself in a quiet way without running away, that is the necessary honesty. When we can do nothing and be extraordinarily happy and at peace with that, we have found tranquility within ourselves.

Through experience, we find we can trust the moments when we do not know which way to go, when we feel like we will never have the answers. We know we can stop there and listen. This is the heart of meditation: it is the act of listening in a deep way. You could boil all of spirituality down to the art and practice of listening to nothing and trusting in the difficulty. That is what I learned on that first retreat. It taught me that a direct encounter with challenge is a doorway to accessing our depth, coming face-to-face with our most important thing, and being able to trust in the unfolding of our life.

As a teacher, one of the things I see is the failure of people to trust their lives — their problems and sometimes even their successes. It is a failure to trust that their life is its own teacher, that within the exact way their human life is expressing itself lies the highest wisdom, and that they can access it if they can sit still and listen. If they can sink into themselves, their own nobody-ness, and allow difficulty to strip them of their somebody-ness, then they can do away with the masks of their persona. Spiritually speaking, this is exactly what we want: to remove the masks. Sometimes we take them off willingly, sometimes they fall away, and sometimes they are torn off.

Unmasking is the spiritual path. It is not about creating new masks — not even spiritual masks. It is not about going from being a worldly person to a spiritual person or trading a spiritual ego for a materialistic ego. It is a matter of authenticity and of the capacity to trust life, even if life has been tremendously tough. It is stopping right where you are and entering profound listening, availability, and openness. If you feel wonderful, you feel wonderful; if you feel lost, you feel lost, but you can trust in being lost. You can do this without talking to yourself about it and without creating a story around it. We must find that capacity to trust ourselves and to trust our life — all of it, whatever it is — because that is what allows the light to shine and revelation to arise.

See also Yoga and Religion: My Long Walk Toward Worship

We see it when we stop and listen, not with our ears and not with our mind, but with our heart, with a tender and intimate quality of awareness that opens us beyond our conditioned ways of experiencing any moment. My first retreat, as difficult as it was, taught me that the most amazing things can come out of the most difficult experiences if we dedicate ourselves to showing up for the situation. That is the heart of meditation and the heart of what it takes to discover who and what we are as we turn away from external things and toward the source of love, the source of wisdom, the source of freedom and happiness within. That is where you will find your most important thing.

TheundefinedMost Important Thing: Discovering Truth at the Heart of Life

Excerpted from The Most Important Thing: Discovering Truth at the Heart of Life by Adyashanti. Copyright ©2018 by Adyashanti. Published by Sounds True in January 2019.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function() n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments) ;if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n; n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0';n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script','https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js'); (function() fbq('init', '1397247997268188'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); var contentId = 'ci023c2437b0002602'; if (contentId !== '') fbq('track', 'ViewContent', content_ids: [contentId], content_type: 'product'); )();

Source link

#Benefits of Meditation#meditation#Namaste Blog#spirituality#Yoga 101#yoga for beginners#yoga poses#Yoga Exercises

0 notes

Text

How a Daily Meditation Practice Helps You Find Trust

How a Daily Meditation Practice Helps You Find Trust:

One of the nice things about meditation is that when we sit with these moments as they arise, we start to trust in them and in the dark grace.

To see yourself is the heart of what a spiritual discipline like meditation is all about.

After meditating with my first meditation teacher, Arvis, for some time, I decided to do a weeklong silent Zen meditation retreat. Arvis said, “I feel good about a teacher named Jakusho Kwong up at Sonoma Mountain Zen Center. Maybe that would be a good place for you to go.” I was excited to experience an authentic retreat in a Zen Buddhist temple with all the accoutrements — the bells, the robes, the rituals, the whole thing.

I got there in the late afternoon, and the retreat was scheduled to start in the early evening. After we had dinner, we went into the Zendo for the first meditation session. It was a very formal place, and I had no idea what the etiquette was. There was minimal instruction, so I learned what I was supposed to be doing by watching other people, which heightened my awareness right away. I sat down on my cushion with all my gleeful anticipation about this experience as the temple bell was struck three times to begin the period of meditation.

As soon as that bell rang, adrenaline flooded my body. It was not fear, but my whole system went into fight-or-flight mode. All I could think was, How do I get out of here? Let me out of here! which is silly because five seconds earlier I was thrilled about being there.

Fortunately, a small, quiet voice inside me said, You have no idea how important this is. You must stay. So even though I had adrenaline rushes twenty-four hours a day for five days and nights in a row, I did not sleep throughout the entire retreat, and I contemplated leaving many times, I managed to hang in there — barely — and finish. Not an auspicious beginning for a future spiritual teacher, but that is what happened. I never knew exactly why I had that reaction, but I have a hunch. When you undertake a retreat like that, something deep within you knows, Oh, boy, the jig is up now. This is not make-believe. This is the real thing. Something in me knew that this was going to be a complete life reorientation. I did not realize this consciously, but unconsciously my ego reacted as if threatened: This is it. This guy is considering the nature of his own being as far as the egoic impulse running the rest of life.

In some ways, my first retreat was a disaster. The only thing that got me through was a mantra I came up with on the second day. Thousands of times over those five nights and days, I said to myself: I will never, ever, ever do this again. That was my big spiritual mantra!

One of the things that impressed me during that retreat was that Kwong — the roshi, or teacher — gave a talk each day, and that talk was my respite because I got to sit and listen and be entertained. It was a relief from the bone-jarring meditation, the never-ending silence, and the pain in my knees and back. Kwong had recently returned from a trip to India that had a huge impact on him. I could tell because as he was recounting stories about his trip, tears streamed down his cheeks and dripped off the bottom of his chin.

See also Try This Durga-Inspired Guided Meditation for Strength

One story especially touched me. Kwong was walking on a dirt road through an impoverished area. There were some kids playing a game with a ball and a stick out in the middle of the road. One kid stood apart from the group, as if ostracized. This boy was watching the kids play and had a sad look on his face. He had a cleft palate, so his upper lip was severely deformed. Kwong walked up to the boy, but they did not speak the same language, so he did not know what to say. There was a moment of indecision, and then Kwong took the boy’s hand in his and with his other hand reached into his pocket and pulled out some money. He pointed to a little shop that sold ice cream and gave the money to the boy. I thought it was a sweet way of giving a little comfort and acknowledging this poor kid’s existence, his loneliness.

As Kwong did this, he gestured to the group of children that seemed to have rejected the boy as if to say, “Go get them and buy them ice cream.” He had given the child enough money to buy treats for all the kids. The boy waved to them and pointed toward the ice cream shop, and all the children joined this one kid who had been lonely and sad. Suddenly he was the hero! He had money and was buying ice cream for everybody. The kids were laughing and talking with him. He was included in their group.

Kwong sat in full lotus position on his cushion in his beautiful brown teacher’s robes and told this story in a resonant, soft voice, deeply touched by the poverty that he saw and by the loneliness of that child. He never hid his tears, and he never seemed embarrassed by his emotion. Watching another man embody this juxtaposition of great strength and tenderness taught me more about true masculinity than anything else in my life. Hearing him speak with such fearlessness was extraordinary. For a young, aspiring Zen student, to have this be my first encounter with a Zen master was a tremendous stroke of good luck and grace, especially since during this whole retreat, except for the talks, I was hanging on by a thread. I continued to study with Kwong, did some retreats with him over the years, and appreciated his great wisdom, but I never again saw him in the state he was in on that first retreat. His openness and dignity were a powerful teaching — it was like being bathed in grace.

Since then I have attended and led hundreds of retreats, but I still look back on that first one with Kwong as both the absolute worst and absolute best in my life. I did not know how powerfully it had affected me until months later. Staying with whatever arose for me despite being flooded with adrenaline, sitting with it in a raw way through all those hours of meditation instead of running away, was profound. When you are having that experience, when you are being pushed to your limit, you do not think of it as grace, but the real grace was that I was in that environment. I was in a place where I could not go anywhere, where I could not turn on the TV or listen to the radio or grab a book or enter a discussion. I had to face the entirety of my experience. Afterward, when I tried to describe the retreat to people, I would end up in tears — not tears of sadness or even of joy, but of depth. I had touched upon something that was so meaningful, vital, and important that it opened my heart.

See also This 6-Minute Sound Bath Is About to Change Your Day for the Better

Meditation Helps You Feel Your Feelings

As we go through life, we eventually have enough experience to see that sometimes profound difficulty can also be profoundly heart opening. When you are in a tough position, when you are facing something hard, when you feel challenged, when you feel like you are at your edge, it is a gift to have the willingness to stop, to sit with those moments, and not to look for the quick, easy resolution for that feeling. It is a kind of grace to be able and willing to open yourself entirely to the experience of challenge, of difficulty, and of insecurity.

There is light grace, and there is dark grace. Light grace is when you have a revelation — when you have insights. Awakening is a light grace; it is like the sun coming out from behind the clouds. The heart opens, and old identities fall away. Then there is dark grace, like what I had on that retreat. I do not mean “dark” in the sense of sinister or evil, but “dark” in the sense of traveling through the darkness looking for light. You cannot see the way through whatever you are experiencing and whatever the challenge is. One of the most amazing things that daily meditation has taught me over many years is to have the wisdom and grace to quietly and silently be with whatever presents itself, whatever is there, without looking for a solution or an explanation.

To see yourself is the heart of what a spiritual discipline like meditation is all about. When people come on retreat with me, we meditate for five or six periods a day. The idea of meditation is not necessarily to get good at it — whatever your definition may be of being “good” at meditation — but the most important thing, the useful thing, the reason we are meditating is so that we encounter ourselves. If you are not using your meditation to hide from your experience or to transcend it or to concentrate your way out of it, if you are being quietly present, meditation forces honesty. It is an extraordinarily truthful way to experience yourself in that moment. This willingness to encounter yourself is vitally important. It is a key to spiritual life and to awakening: being present for whatever is. Sometimes “whatever is” is mundane; sometimes it is full of light, grace, and insight; and sometimes it begins as a dark grace, where we do not know where we are going or how to get through it, and then suddenly there is light.

One of the nice things about meditation is that when we sit with these moments as they arise, we start to trust in them and in the dark grace. We realize that it is in feeling lost that our true nature finds itself. In meditation we encounter ourselves, and it elicits a real honesty if we are ready for it. You can read about things forever, you can listen to talks forever, and you can assume that you understand or that you have got it, but if you can be with yourself in a quiet way without running away, that is the necessary honesty. When we can do nothing and be extraordinarily happy and at peace with that, we have found tranquility within ourselves.

Through experience, we find we can trust the moments when we do not know which way to go, when we feel like we will never have the answers. We know we can stop there and listen. This is the heart of meditation: it is the act of listening in a deep way. You could boil all of spirituality down to the art and practice of listening to nothing and trusting in the difficulty. That is what I learned on that first retreat. It taught me that a direct encounter with challenge is a doorway to accessing our depth, coming face-to-face with our most important thing, and being able to trust in the unfolding of our life.

As a teacher, one of the things I see is the failure of people to trust their lives — their problems and sometimes even their successes. It is a failure to trust that their life is its own teacher, that within the exact way their human life is expressing itself lies the highest wisdom, and that they can access it if they can sit still and listen. If they can sink into themselves, their own nobody-ness, and allow difficulty to strip them of their somebody-ness, then they can do away with the masks of their persona. Spiritually speaking, this is exactly what we want: to remove the masks. Sometimes we take them off willingly, sometimes they fall away, and sometimes they are torn off.

Unmasking is the spiritual path. It is not about creating new masks — not even spiritual masks. It is not about going from being a worldly person to a spiritual person or trading a spiritual ego for a materialistic ego. It is a matter of authenticity and of the capacity to trust life, even if life has been tremendously tough. It is stopping right where you are and entering profound listening, availability, and openness. If you feel wonderful, you feel wonderful; if you feel lost, you feel lost, but you can trust in being lost. You can do this without talking to yourself about it and without creating a story around it. We must find that capacity to trust ourselves and to trust our life — all of it, whatever it is — because that is what allows the light to shine and revelation to arise.

See also Yoga and Religion: My Long Walk Toward Worship

We see it when we stop and listen, not with our ears and not with our mind, but with our heart, with a tender and intimate quality of awareness that opens us beyond our conditioned ways of experiencing any moment. My first retreat, as difficult as it was, taught me that the most amazing things can come out of the most difficult experiences if we dedicate ourselves to showing up for the situation. That is the heart of meditation and the heart of what it takes to discover who and what we are as we turn away from external things and toward the source of love, the source of wisdom, the source of freedom and happiness within. That is where you will find your most important thing.

TheundefinedMost Important Thing: Discovering Truth at the Heart of Life

Excerpted from The Most Important Thing: Discovering Truth at the Heart of Life by Adyashanti. Copyright ©2018 by Adyashanti. Published by Sounds True in January 2019.

0 notes

Link

One of the nice things about meditation is that when we sit with these moments as they arise, we start to trust in them and in the dark grace.

To see yourself is the heart of what a spiritual discipline like meditation is all about.

After meditating with my first meditation teacher, Arvis, for some time, I decided to do a weeklong silent Zen meditation retreat. Arvis said, “I feel good about a teacher named Jakusho Kwong up at Sonoma Mountain Zen Center. Maybe that would be a good place for you to go.” I was excited to experience an authentic retreat in a Zen Buddhist temple with all the accoutrements — the bells, the robes, the rituals, the whole thing.

I got there in the late afternoon, and the retreat was scheduled to start in the early evening. After we had dinner, we went into the Zendo for the first meditation session. It was a very formal place, and I had no idea what the etiquette was. There was minimal instruction, so I learned what I was supposed to be doing by watching other people, which heightened my awareness right away. I sat down on my cushion with all my gleeful anticipation about this experience as the temple bell was struck three times to begin the period of meditation.

As soon as that bell rang, adrenaline flooded my body. It was not fear, but my whole system went into fight-or-flight mode. All I could think was, How do I get out of here? Let me out of here! which is silly because five seconds earlier I was thrilled about being there.

Fortunately, a small, quiet voice inside me said, You have no idea how important this is. You must stay. So even though I had adrenaline rushes twenty-four hours a day for five days and nights in a row, I did not sleep throughout the entire retreat, and I contemplated leaving many times, I managed to hang in there — barely — and finish. Not an auspicious beginning for a future spiritual teacher, but that is what happened. I never knew exactly why I had that reaction, but I have a hunch. When you undertake a retreat like that, something deep within you knows, Oh, boy, the jig is up now. This is not make-believe. This is the real thing. Something in me knew that this was going to be a complete life reorientation. I did not realize this consciously, but unconsciously my ego reacted as if threatened: This is it. This guy is considering the nature of his own being as far as the egoic impulse running the rest of life.

In some ways, my first retreat was a disaster. The only thing that got me through was a mantra I came up with on the second day. Thousands of times over those five nights and days, I said to myself: I will never, ever, ever do this again. That was my big spiritual mantra!

One of the things that impressed me during that retreat was that Kwong — the roshi, or teacher — gave a talk each day, and that talk was my respite because I got to sit and listen and be entertained. It was a relief from the bone-jarring meditation, the never-ending silence, and the pain in my knees and back. Kwong had recently returned from a trip to India that had a huge impact on him. I could tell because as he was recounting stories about his trip, tears streamed down his cheeks and dripped off the bottom of his chin.

See also Try This Durga-Inspired Guided Meditation for Strength

One story especially touched me. Kwong was walking on a dirt road through an impoverished area. There were some kids playing a game with a ball and a stick out in the middle of the road. One kid stood apart from the group, as if ostracized. This boy was watching the kids play and had a sad look on his face. He had a cleft palate, so his upper lip was severely deformed. Kwong walked up to the boy, but they did not speak the same language, so he did not know what to say. There was a moment of indecision, and then Kwong took the boy’s hand in his and with his other hand reached into his pocket and pulled out some money. He pointed to a little shop that sold ice cream and gave the money to the boy. I thought it was a sweet way of giving a little comfort and acknowledging this poor kid’s existence, his loneliness.

As Kwong did this, he gestured to the group of children that seemed to have rejected the boy as if to say, “Go get them and buy them ice cream.” He had given the child enough money to buy treats for all the kids. The boy waved to them and pointed toward the ice cream shop, and all the children joined this one kid who had been lonely and sad. Suddenly he was the hero! He had money and was buying ice cream for everybody. The kids were laughing and talking with him. He was included in their group.

Kwong sat in full lotus position on his cushion in his beautiful brown teacher’s robes and told this story in a resonant, soft voice, deeply touched by the poverty that he saw and by the loneliness of that child. He never hid his tears, and he never seemed embarrassed by his emotion. Watching another man embody this juxtaposition of great strength and tenderness taught me more about true masculinity than anything else in my life. Hearing him speak with such fearlessness was extraordinary. For a young, aspiring Zen student, to have this be my first encounter with a Zen master was a tremendous stroke of good luck and grace, especially since during this whole retreat, except for the talks, I was hanging on by a thread. I continued to study with Kwong, did some retreats with him over the years, and appreciated his great wisdom, but I never again saw him in the state he was in on that first retreat. His openness and dignity were a powerful teaching — it was like being bathed in grace.

Since then I have attended and led hundreds of retreats, but I still look back on that first one with Kwong as both the absolute worst and absolute best in my life. I did not know how powerfully it had affected me until months later. Staying with whatever arose for me despite being flooded with adrenaline, sitting with it in a raw way through all those hours of meditation instead of running away, was profound. When you are having that experience, when you are being pushed to your limit, you do not think of it as grace, but the real grace was that I was in that environment. I was in a place where I could not go anywhere, where I could not turn on the TV or listen to the radio or grab a book or enter a discussion. I had to face the entirety of my experience. Afterward, when I tried to describe the retreat to people, I would end up in tears — not tears of sadness or even of joy, but of depth. I had touched upon something that was so meaningful, vital, and important that it opened my heart.

See also This 6-Minute Sound Bath Is About to Change Your Day for the Better

Meditation Helps You Feel Your Feelings

As we go through life, we eventually have enough experience to see that sometimes profound difficulty can also be profoundly heart opening. When you are in a tough position, when you are facing something hard, when you feel challenged, when you feel like you are at your edge, it is a gift to have the willingness to stop, to sit with those moments, and not to look for the quick, easy resolution for that feeling. It is a kind of grace to be able and willing to open yourself entirely to the experience of challenge, of difficulty, and of insecurity.

There is light grace, and there is dark grace. Light grace is when you have a revelation — when you have insights. Awakening is a light grace; it is like the sun coming out from behind the clouds. The heart opens, and old identities fall away. Then there is dark grace, like what I had on that retreat. I do not mean “dark” in the sense of sinister or evil, but “dark” in the sense of traveling through the darkness looking for light. You cannot see the way through whatever you are experiencing and whatever the challenge is. One of the most amazing things that daily meditation has taught me over many years is to have the wisdom and grace to quietly and silently be with whatever presents itself, whatever is there, without looking for a solution or an explanation.

To see yourself is the heart of what a spiritual discipline like meditation is all about. When people come on retreat with me, we meditate for five or six periods a day. The idea of meditation is not necessarily to get good at it — whatever your definition may be of being “good” at meditation — but the most important thing, the useful thing, the reason we are meditating is so that we encounter ourselves. If you are not using your meditation to hide from your experience or to transcend it or to concentrate your way out of it, if you are being quietly present, meditation forces honesty. It is an extraordinarily truthful way to experience yourself in that moment. This willingness to encounter yourself is vitally important. It is a key to spiritual life and to awakening: being present for whatever is. Sometimes “whatever is” is mundane; sometimes it is full of light, grace, and insight; and sometimes it begins as a dark grace, where we do not know where we are going or how to get through it, and then suddenly there is light.

One of the nice things about meditation is that when we sit with these moments as they arise, we start to trust in them and in the dark grace. We realize that it is in feeling lost that our true nature finds itself. In meditation we encounter ourselves, and it elicits a real honesty if we are ready for it. You can read about things forever, you can listen to talks forever, and you can assume that you understand or that you have got it, but if you can be with yourself in a quiet way without running away, that is the necessary honesty. When we can do nothing and be extraordinarily happy and at peace with that, we have found tranquility within ourselves.

Through experience, we find we can trust the moments when we do not know which way to go, when we feel like we will never have the answers. We know we can stop there and listen. This is the heart of meditation: it is the act of listening in a deep way. You could boil all of spirituality down to the art and practice of listening to nothing and trusting in the difficulty. That is what I learned on that first retreat. It taught me that a direct encounter with challenge is a doorway to accessing our depth, coming face-to-face with our most important thing, and being able to trust in the unfolding of our life.

As a teacher, one of the things I see is the failure of people to trust their lives — their problems and sometimes even their successes. It is a failure to trust that their life is its own teacher, that within the exact way their human life is expressing itself lies the highest wisdom, and that they can access it if they can sit still and listen. If they can sink into themselves, their own nobody-ness, and allow difficulty to strip them of their somebody-ness, then they can do away with the masks of their persona. Spiritually speaking, this is exactly what we want: to remove the masks. Sometimes we take them off willingly, sometimes they fall away, and sometimes they are torn off.

Unmasking is the spiritual path. It is not about creating new masks — not even spiritual masks. It is not about going from being a worldly person to a spiritual person or trading a spiritual ego for a materialistic ego. It is a matter of authenticity and of the capacity to trust life, even if life has been tremendously tough. It is stopping right where you are and entering profound listening, availability, and openness. If you feel wonderful, you feel wonderful; if you feel lost, you feel lost, but you can trust in being lost. You can do this without talking to yourself about it and without creating a story around it. We must find that capacity to trust ourselves and to trust our life — all of it, whatever it is — because that is what allows the light to shine and revelation to arise.

See also Yoga and Religion: My Long Walk Toward Worship

We see it when we stop and listen, not with our ears and not with our mind, but with our heart, with a tender and intimate quality of awareness that opens us beyond our conditioned ways of experiencing any moment. My first retreat, as difficult as it was, taught me that the most amazing things can come out of the most difficult experiences if we dedicate ourselves to showing up for the situation. That is the heart of meditation and the heart of what it takes to discover who and what we are as we turn away from external things and toward the source of love, the source of wisdom, the source of freedom and happiness within. That is where you will find your most important thing.

TheundefinedMost Important Thing: Discovering Truth at the Heart of Life

Excerpted from The Most Important Thing: Discovering Truth at the Heart of Life by Adyashanti. Copyright ©2018 by Adyashanti. Published by Sounds True in January 2019.

0 notes

Link

One of the nice things about meditation is that when we sit with these moments as they arise, we start to trust in them and in the dark grace.

To see yourself is the heart of what a spiritual discipline like meditation is all about.

After meditating with my first meditation teacher, Arvis, for some time, I decided to do a weeklong silent Zen meditation retreat. Arvis said, “I feel good about a teacher named Jakusho Kwong up at Sonoma Mountain Zen Center. Maybe that would be a good place for you to go.” I was excited to experience an authentic retreat in a Zen Buddhist temple with all the accoutrements — the bells, the robes, the rituals, the whole thing.

I got there in the late afternoon, and the retreat was scheduled to start in the early evening. After we had dinner, we went into the Zendo for the first meditation session. It was a very formal place, and I had no idea what the etiquette was. There was minimal instruction, so I learned what I was supposed to be doing by watching other people, which heightened my awareness right away. I sat down on my cushion with all my gleeful anticipation about this experience as the temple bell was struck three times to begin the period of meditation.

As soon as that bell rang, adrenaline flooded my body. It was not fear, but my whole system went into fight-or-flight mode. All I could think was, How do I get out of here? Let me out of here! which is silly because five seconds earlier I was thrilled about being there.

Fortunately, a small, quiet voice inside me said, You have no idea how important this is. You must stay. So even though I had adrenaline rushes twenty-four hours a day for five days and nights in a row, I did not sleep throughout the entire retreat, and I contemplated leaving many times, I managed to hang in there — barely — and finish. Not an auspicious beginning for a future spiritual teacher, but that is what happened. I never knew exactly why I had that reaction, but I have a hunch. When you undertake a retreat like that, something deep within you knows, Oh, boy, the jig is up now. This is not make-believe. This is the real thing. Something in me knew that this was going to be a complete life reorientation. I did not realize this consciously, but unconsciously my ego reacted as if threatened: This is it. This guy is considering the nature of his own being as far as the egoic impulse running the rest of life.

In some ways, my first retreat was a disaster. The only thing that got me through was a mantra I came up with on the second day. Thousands of times over those five nights and days, I said to myself: I will never, ever, ever do this again. That was my big spiritual mantra!

One of the things that impressed me during that retreat was that Kwong — the roshi, or teacher — gave a talk each day, and that talk was my respite because I got to sit and listen and be entertained. It was a relief from the bone-jarring meditation, the never-ending silence, and the pain in my knees and back. Kwong had recently returned from a trip to India that had a huge impact on him. I could tell because as he was recounting stories about his trip, tears streamed down his cheeks and dripped off the bottom of his chin.

See also Try This Durga-Inspired Guided Meditation for Strength

One story especially touched me. Kwong was walking on a dirt road through an impoverished area. There were some kids playing a game with a ball and a stick out in the middle of the road. One kid stood apart from the group, as if ostracized. This boy was watching the kids play and had a sad look on his face. He had a cleft palate, so his upper lip was severely deformed. Kwong walked up to the boy, but they did not speak the same language, so he did not know what to say. There was a moment of indecision, and then Kwong took the boy’s hand in his and with his other hand reached into his pocket and pulled out some money. He pointed to a little shop that sold ice cream and gave the money to the boy. I thought it was a sweet way of giving a little comfort and acknowledging this poor kid’s existence, his loneliness.

As Kwong did this, he gestured to the group of children that seemed to have rejected the boy as if to say, “Go get them and buy them ice cream.” He had given the child enough money to buy treats for all the kids. The boy waved to them and pointed toward the ice cream shop, and all the children joined this one kid who had been lonely and sad. Suddenly he was the hero! He had money and was buying ice cream for everybody. The kids were laughing and talking with him. He was included in their group.

Kwong sat in full lotus position on his cushion in his beautiful brown teacher’s robes and told this story in a resonant, soft voice, deeply touched by the poverty that he saw and by the loneliness of that child. He never hid his tears, and he never seemed embarrassed by his emotion. Watching another man embody this juxtaposition of great strength and tenderness taught me more about true masculinity than anything else in my life. Hearing him speak with such fearlessness was extraordinary. For a young, aspiring Zen student, to have this be my first encounter with a Zen master was a tremendous stroke of good luck and grace, especially since during this whole retreat, except for the talks, I was hanging on by a thread. I continued to study with Kwong, did some retreats with him over the years, and appreciated his great wisdom, but I never again saw him in the state he was in on that first retreat. His openness and dignity were a powerful teaching — it was like being bathed in grace.

Since then I have attended and led hundreds of retreats, but I still look back on that first one with Kwong as both the absolute worst and absolute best in my life. I did not know how powerfully it had affected me until months later. Staying with whatever arose for me despite being flooded with adrenaline, sitting with it in a raw way through all those hours of meditation instead of running away, was profound. When you are having that experience, when you are being pushed to your limit, you do not think of it as grace, but the real grace was that I was in that environment. I was in a place where I could not go anywhere, where I could not turn on the TV or listen to the radio or grab a book or enter a discussion. I had to face the entirety of my experience. Afterward, when I tried to describe the retreat to people, I would end up in tears — not tears of sadness or even of joy, but of depth. I had touched upon something that was so meaningful, vital, and important that it opened my heart.

See also This 6-Minute Sound Bath Is About to Change Your Day for the Better

Meditation Helps You Feel Your Feelings

As we go through life, we eventually have enough experience to see that sometimes profound difficulty can also be profoundly heart opening. When you are in a tough position, when you are facing something hard, when you feel challenged, when you feel like you are at your edge, it is a gift to have the willingness to stop, to sit with those moments, and not to look for the quick, easy resolution for that feeling. It is a kind of grace to be able and willing to open yourself entirely to the experience of challenge, of difficulty, and of insecurity.

There is light grace, and there is dark grace. Light grace is when you have a revelation — when you have insights. Awakening is a light grace; it is like the sun coming out from behind the clouds. The heart opens, and old identities fall away. Then there is dark grace, like what I had on that retreat. I do not mean “dark” in the sense of sinister or evil, but “dark” in the sense of traveling through the darkness looking for light. You cannot see the way through whatever you are experiencing and whatever the challenge is. One of the most amazing things that daily meditation has taught me over many years is to have the wisdom and grace to quietly and silently be with whatever presents itself, whatever is there, without looking for a solution or an explanation.

To see yourself is the heart of what a spiritual discipline like meditation is all about. When people come on retreat with me, we meditate for five or six periods a day. The idea of meditation is not necessarily to get good at it — whatever your definition may be of being “good” at meditation — but the most important thing, the useful thing, the reason we are meditating is so that we encounter ourselves. If you are not using your meditation to hide from your experience or to transcend it or to concentrate your way out of it, if you are being quietly present, meditation forces honesty. It is an extraordinarily truthful way to experience yourself in that moment. This willingness to encounter yourself is vitally important. It is a key to spiritual life and to awakening: being present for whatever is. Sometimes “whatever is” is mundane; sometimes it is full of light, grace, and insight; and sometimes it begins as a dark grace, where we do not know where we are going or how to get through it, and then suddenly there is light.

One of the nice things about meditation is that when we sit with these moments as they arise, we start to trust in them and in the dark grace. We realize that it is in feeling lost that our true nature finds itself. In meditation we encounter ourselves, and it elicits a real honesty if we are ready for it. You can read about things forever, you can listen to talks forever, and you can assume that you understand or that you have got it, but if you can be with yourself in a quiet way without running away, that is the necessary honesty. When we can do nothing and be extraordinarily happy and at peace with that, we have found tranquility within ourselves.

Through experience, we find we can trust the moments when we do not know which way to go, when we feel like we will never have the answers. We know we can stop there and listen. This is the heart of meditation: it is the act of listening in a deep way. You could boil all of spirituality down to the art and practice of listening to nothing and trusting in the difficulty. That is what I learned on that first retreat. It taught me that a direct encounter with challenge is a doorway to accessing our depth, coming face-to-face with our most important thing, and being able to trust in the unfolding of our life.

As a teacher, one of the things I see is the failure of people to trust their lives — their problems and sometimes even their successes. It is a failure to trust that their life is its own teacher, that within the exact way their human life is expressing itself lies the highest wisdom, and that they can access it if they can sit still and listen. If they can sink into themselves, their own nobody-ness, and allow difficulty to strip them of their somebody-ness, then they can do away with the masks of their persona. Spiritually speaking, this is exactly what we want: to remove the masks. Sometimes we take them off willingly, sometimes they fall away, and sometimes they are torn off.

Unmasking is the spiritual path. It is not about creating new masks — not even spiritual masks. It is not about going from being a worldly person to a spiritual person or trading a spiritual ego for a materialistic ego. It is a matter of authenticity and of the capacity to trust life, even if life has been tremendously tough. It is stopping right where you are and entering profound listening, availability, and openness. If you feel wonderful, you feel wonderful; if you feel lost, you feel lost, but you can trust in being lost. You can do this without talking to yourself about it and without creating a story around it. We must find that capacity to trust ourselves and to trust our life — all of it, whatever it is — because that is what allows the light to shine and revelation to arise.

See also Yoga and Religion: My Long Walk Toward Worship

We see it when we stop and listen, not with our ears and not with our mind, but with our heart, with a tender and intimate quality of awareness that opens us beyond our conditioned ways of experiencing any moment. My first retreat, as difficult as it was, taught me that the most amazing things can come out of the most difficult experiences if we dedicate ourselves to showing up for the situation. That is the heart of meditation and the heart of what it takes to discover who and what we are as we turn away from external things and toward the source of love, the source of wisdom, the source of freedom and happiness within. That is where you will find your most important thing.

TheundefinedMost Important Thing: Discovering Truth at the Heart of Life

Excerpted from The Most Important Thing: Discovering Truth at the Heart of Life by Adyashanti. Copyright ©2018 by Adyashanti. Published by Sounds True in January 2019.

0 notes

Text

How a Daily Meditation Practice Helps You Find Trust

One of the nice things about meditation is that when we sit with these moments as they arise, we start to trust in them and in the dark grace.

To see yourself is the heart of what a spiritual discipline like meditation is all about.

After meditating with my first meditation teacher, Arvis, for some time, I decided to do a weeklong silent Zen meditation retreat. Arvis said, “I feel good about a teacher named Jakusho Kwong up at Sonoma Mountain Zen Center. Maybe that would be a good place for you to go.” I was excited to experience an authentic retreat in a Zen Buddhist temple with all the accoutrements — the bells, the robes, the rituals, the whole thing.

I got there in the late afternoon, and the retreat was scheduled to start in the early evening. After we had dinner, we went into the Zendo for the first meditation session. It was a very formal place, and I had no idea what the etiquette was. There was minimal instruction, so I learned what I was supposed to be doing by watching other people, which heightened my awareness right away. I sat down on my cushion with all my gleeful anticipation about this experience as the temple bell was struck three times to begin the period of meditation.

As soon as that bell rang, adrenaline flooded my body. It was not fear, but my whole system went into fight-or-flight mode. All I could think was, How do I get out of here? Let me out of here! which is silly because five seconds earlier I was thrilled about being there.

Fortunately, a small, quiet voice inside me said, You have no idea how important this is. You must stay. So even though I had adrenaline rushes twenty-four hours a day for five days and nights in a row, I did not sleep throughout the entire retreat, and I contemplated leaving many times, I managed to hang in there — barely — and finish. Not an auspicious beginning for a future spiritual teacher, but that is what happened. I never knew exactly why I had that reaction, but I have a hunch. When you undertake a retreat like that, something deep within you knows, Oh, boy, the jig is up now. This is not make-believe. This is the real thing. Something in me knew that this was going to be a complete life reorientation. I did not realize this consciously, but unconsciously my ego reacted as if threatened: This is it. This guy is considering the nature of his own being as far as the egoic impulse running the rest of life.

In some ways, my first retreat was a disaster. The only thing that got me through was a mantra I came up with on the second day. Thousands of times over those five nights and days, I said to myself: I will never, ever, ever do this again. That was my big spiritual mantra!

One of the things that impressed me during that retreat was that Kwong — the roshi, or teacher — gave a talk each day, and that talk was my respite because I got to sit and listen and be entertained. It was a relief from the bone-jarring meditation, the never-ending silence, and the pain in my knees and back. Kwong had recently returned from a trip to India that had a huge impact on him. I could tell because as he was recounting stories about his trip, tears streamed down his cheeks and dripped off the bottom of his chin.

See also Try This Durga-Inspired Guided Meditation for Strength

One story especially touched me. Kwong was walking on a dirt road through an impoverished area. There were some kids playing a game with a ball and a stick out in the middle of the road. One kid stood apart from the group, as if ostracized. This boy was watching the kids play and had a sad look on his face. He had a cleft palate, so his upper lip was severely deformed. Kwong walked up to the boy, but they did not speak the same language, so he did not know what to say. There was a moment of indecision, and then Kwong took the boy’s hand in his and with his other hand reached into his pocket and pulled out some money. He pointed to a little shop that sold ice cream and gave the money to the boy. I thought it was a sweet way of giving a little comfort and acknowledging this poor kid’s existence, his loneliness.

As Kwong did this, he gestured to the group of children that seemed to have rejected the boy as if to say, “Go get them and buy them ice cream.” He had given the child enough money to buy treats for all the kids. The boy waved to them and pointed toward the ice cream shop, and all the children joined this one kid who had been lonely and sad. Suddenly he was the hero! He had money and was buying ice cream for everybody. The kids were laughing and talking with him. He was included in their group.