#i also think its interesting to think about rodney being brave for himself

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#tv: sga#rodney mckay#stargate atlantis#my gifs#just rodney always being the most brave when it comes to his friends#tho honestly#i think in some ways fandom has ruined me bc theres a lot less coward/weak moments than i was expecting#so i think its one of those moments where i may need to go back to the canon source and remind myself fanon is not always right#i also think its interesting to think about rodney being brave for himself#and brave for others#because hes always a lot more inclined to be yell-y and stuff when hes being brave to save himself#but when hes being brave for his friends?#hes focused#he's intent and hes gonna fucking help them#my brave little toaster i love him so much

609 notes

·

View notes

Text

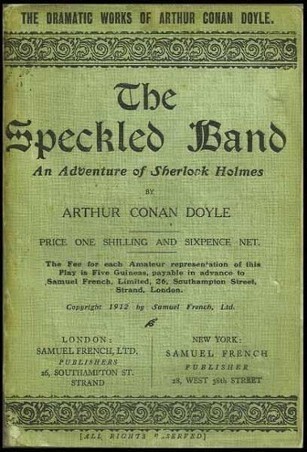

The Speckled Band on Stage: Yep, Still Gay

Note: I tagged those who reblogged the first part of this series. Please let me know if you would prefer not to be tagged in future posts.

This is the second installment in my series on obscure Sherlock Holmes film adaptations and their depiction of Holmes and Watson both individually and in relation to each other. (For a discussion of the 1921-23 silent films starring Eille Norwood, which appears to have been Doyle’s favorite adaptation, see here.)

I really didn’t mean to write a post about this one, seeing as it doesn’t strictly fit the theme of this series. It is a play, not a film, and it is only sort of an adaptation—although a retelling of The Speckled Band, it is written by Doyle himself. But while researching a very gay and very terrible 1931 film, I discovered that it was loosely adapted from this play. Naturally I read it as part of my research, telling myself that I wouldn’t get sidetracked writing a post about it. The failure of my self-control now lays before you.

In my defense, this play really is … well it really is Something. All sorts of wonderful and all sorts of tragic. If you’d prefer to read it for yourself before encountering the spoilers in this post, hop on over here and scroll to the second half of the webpage. And if you’ve got your subtext glasses so much as perched lightly on the end of your nose, be ready to be sent reeling by what you find.

(Spoilers below the cut)

Production and Reception

Doyle’s decision to adapt The Speckled Band for the stage was rather spur-of-the-moment. He had leased a theater for six months in order to showcase The House of Temperley, an adaptation of his novel Rodney Stone, but the play was largely unsuccessful (x, x). Threatened with considerable financial loss, Doyle set to work and within a week had written The Speckled Band. Despite its rushed composition the play was decidedly successful, and Doyle seems to have been quite pleased with it (x).

The play alters the original short story considerably. Some changes are so inconsequential as to be puzzling—the villain’s name is changed from Roylott to Rylott, the names of the stepdaughters are switched, etc—but other alterations are structural and make a significant difference. In particular, instead of following Watson’s pov, the audience’s perspective revolves primarily around the Rylott house. The scenes introducing Holmes and Watson are also considerably altered and expanded for potentially unfamiliar audiences, and a good deal more shouting and action is introduced throughout.

Oh, and Watson is engaged to Mary Morstan. Yeah. More on that later.

I have two complaints: First there is an uncomfortable dash of orientalism (i.e., western depictions of the east which cast it as mysterious, dangerous, and Other, and which played a largely unintentional but nonetheless significant role in justifying British imperialism), which is present in the original story but rather more prevalent in the stage play. Second, the female protagonist, although commendably brave, loses what little agency she had in the original story. But aside from these elements, I loved this play. The pacing is good and kept me engaged even when neither Sherlock or Watson are present, Dr. Rylott is genuinely frightening and I was really rather tense at times despite knowing the ending, and the occasional humor is on point—I actually laughed aloud once or twice. Further, ACD’s allegiance with the oppressed is out in full force, and there’s some genuinely touching commentary on the debilitating effects of abuse. And then, of course, there is Sherlock Holmes and Doctor John Watson …

Sherlock Holmes on Stage

Guys. This is, pure and undiluted, Sherlock Holmes at his best. If you ever start to fear that Sherlock really might be the cold and detached reasoning machine some folk have fixated on, just read the way Arthur Conan Doyle writes him in this play. You will never doubt again that he is anything besides a snarky ahead-of-his-time genius with a heart of literal gay gold. We’ll get to the ‘gay’ part in later section, so we’ll set aside his interactions with Watson for the moment. There is plenty else to discuss.

You see, this Holmes does spout a variation of that much abused line from A Scandal in Belgravia, saying: “[love] would disturb my reason, unbalance my faculties. Love is like a flaw in the crystal, sand in the clockwork, iron near the magnet.” I understand that the statement, here and in Scandle, refers specifically to romantic love. Yet I cannot think it’s an accident that nearly the very next moment Holmes is flatly refusing to find the wife of a clearly abusive husband, asking only enough questions to ensure that she has found a safe refuge, even though the law is on the husband’s side and the man offers a whopping fee of 500 pounds. As if Doyle wants to drive home that Holmes accepts cases purely on the basis of empathy for the downtrodden and not finances, Holmes then remarks: “I’m afraid I shall never be a rich man, Watson.” Added to this, the manner in which he listens to, comforts, and puts himself in danger for Roylott’s step-daughter Enid is genuinely touching. As many of us have asserted for years, Sherlock Holmes is the champion of justice, ally of the oppressed, and altogether a beautiful smol man. ‘Love is a flaw in the crystal,’ indeed.

There is also a pleasing dash of Holmes the psychologist. It appears most obviously in an early analysis of Dr. Roylott, but most touchingly toward Rylott’s mercilessly abused servant Rodgers. The man is essentially good-hearted but entirely incapacitated by fear of his master, and this leads to his betraying Enid’s attempts to contact Sherlock. It was obviously a shitty move, but Holmes, who earlier expressed understanding of the thoroughgoing damage caused by the man’s long, forced dependence on a maniac for his basic needs, responds compassionately: “He is not to be blamed. His master controls him.”

Added to this we have Holmes in disguises, bamf!Holmes, Holmes calling people idiots and taking far too much delight in dancing circles around them, and of course utterly brilliant Holmes (though that’s a given), so it seems almost an embarrassment of riches that we also get peak sassy Holmes. He makes a number of delightful appearances, although my favorite is the following, which occurs after he has agreed to protect Enid from Rylott:

RYLOTT: What I ask you to do — what I order you to do is to leave my affairs alone. Alone, sir — do you hear me? HOLMES: You are perfectly audible.

As utterly delightful as all of this is, Holmes’s darker side is not entirely absent, at least in his personal habits—the cocaine does make its appearance. But more on that later.

John Watson on Stage

To be honest, I found myself rather anxious about how Doyle would depict Watson. We fans have been in the habit of discovering Watson between the lines of the cannon stories—as the man is far more interested in talking about Holmes than himself, it takes a bit of digging to discover Watson’s outstanding qualities. But what if the Watson we love so dearly is our own invention, and Doyle himself was simply uninterested in the man except as a conduit to portraying Holmes?

I really shouldn’t have worried.

It is true that Watson rather disappears into the background once Holmes is working. But that is not to say he becomes at all useless. In fact, the Watson in this play is quite simply our Watson—kind, steady, intelligent, dangerous, and with something of a temper hidden beneath the steady veneer.

In the play, Watson is the doctor who examines the body of the first murdered sister (who is here called Violet) two years before Holmes becomes involved in protecting the remaining sister, Enid. Watson, bright fellow that he is, clearly suspects that something is off. Ultimately there is nothing he can do at the time, but his involvement allows for one my favorite moments: Watson employing Holmes’s deductive skills. True, it is for a single, relatively inconsequential matter; but he does it and he’s right and he impresses the whole room and guys! Watson! is! an! intelligent! man! I mean, we’ve all known that for forever, but its rather nice to get such a clear nod of agreement from Dyole.

In addition to his intelligence, Watson exhibits a empathy and compassion that in this story will be matched (not surpassed) only by that of Holmes. As an old friend of Rylott’s now-dead wife, Watson acts as comforter to the surviving girl. We are told that he came immediately and probably well in opposition to his own convenience when first he heard of the tragedy, and his treatment of Enid is gentle without being patronizing. Unsettled by the Rylott household and clearly wishing he could do more, he also repeatedly urges Enid to contact him if she has any suspicion of danger. All of this prompts Enid to declare: “Your kindness has been the one gleam of light in these dark days.” It is a lovely description of the man who has been a light in the dark for at least one other—the sort of testament we would have been unlikely to hear of if this story were reported through Watson’s own narration.

Again, I’ll leave the majority of his interactions with Holmes for the next section, but it is worth mentioning that there is no objection from him when Holmes turns down an easy 500 pounds. Watson is intelligent and he is good—he saw the signs of abuse and he would not have his friend benefit on those terms. These scenes also provide a wonderful dose of protective Watson. And while Holmes is of course at the head of the investigation, he and Watson are wonderfully in sync, and Watson proves his worth.

When it comes down to it, the Holmes and Watson in this play are transparently the two deeply compatible men we seek to dig out of cannon: mutually sharp and compassionate, courageous and quick to protect, with Holmes giving Watson stimulation and purpose and the means to aid others, and Watson providing Holmes with a firm right hand and a ready ear and a steadiness that counteracts the extremities that drive Holmes to cocaine. Watson and Holmes as Doyle portrayed them—as no other adaptation would portray them for far too many years—are just kinda perfect for each other.

But Watson is engaged.

So … What About Johnlock?

*buries head in hands* *giggles* *sobs* … Yeah. Yeah, it’s here. Yeah.

I really wasn’t sure what to expect from this play. I thought that perhaps the stage would strike Doyle as too exposed and vulnerable, or that perhaps he wouldn’t trust the actors, or that he would feel unsafe without the veneer of Watson’s narration—that, one way or another, he’d be persuaded to leave the gay subtext out of this one. But, um, Doyle? Buddy? Don’t get me wrong, I’m absolutely chuffed that you managed to avoid allegations a la Oscar Wilde. But also … how?

Honestly, I’ve always wondered whether Doyle was aware that he was writing a love story or whether that’s what wound up on paper regardless of his intent. This play just might be my answer.

a.) Sherlock Holmes: The Work as a disguise

The most blaring subtext is concentrated in Act II Scene II, where Holmes first enters the stage and his primary interactions with Watson occur. This play takes place during one of the dark times when Watson isn’t living at Baker Street, and when he visits Holmes to present him with Enid’s case, Holmes comes out disguised as a workman. (Before this Watson comments with dismay on the evidence of Holmes’s continued cocaine habits—this will be significant later). The disguised Holmes pokes fun at Watson, who doesn’t recognize him, accusing him of being responsible for Holmes’s untidy habits. There may be a rather tragic subtextual undertone to the whole conversation, but there’s too much else to discuss. So I’ll leave that aside and instead highlight the exchange that occurs when Holmes drops his disguise:

WATSON: Good Heavens Holmes! I should never have recognized you. HOLMES: My dear Watson, when you begin to recognize me it will indeed be the beginning of the end. When your eagle eye penetrates my disguise I shall retire to an eligible poultry farm.

Now, this could be innocent enough—just a fun way to introduce the clever detective. But if one is at all alert to the mere possibility of subtext, alarum bells should be ringing full force at the fact that the first on-stage interaction between these two characters consists of Holme demonstrating his ability to hide his true identity from Watson, and then saying that if he was unable to deceive Watson it would literally be the end of his life as he knows it. And it’s worth taking note of his phrasing: not “when you begin to recognize my disguises,” but rather “when you begin to recognize me.” Is this just a matter of professional pride, or is there something deeper that Holmes is afraid of having discovered?

But you know, maybe I’m just reading into this. This is a story about preventing Enid’s murder, its got nothing to do with romance or love, that would be thematically inconsistent and out of place—

HOLMES: Well, Watson, what is your news? WATSON: Well, Holmes, I came here to tell you what I’m sure will please you. HOLMES: Engaged, Watson, engaged! … The successful suitor shines from you all over.

Oh. Okay then.

Now, it is important to understand that Watson’s marriage has literally nothing to do with the Rylott plot. The engagement in no way affects Watson’s movements, and Mary never appears on stage. No; the first half of this scene is devoted entirely to introducing us to Holmes—the few clients he sees in this section are clearly selected to give us a sense of his character, methods, and values. That means that for some reason Doyle thought that a proper understanding of Holmes requires a discussion of love and marriage—specifically, Watson’s marriage.

Watson, being an imbecile as well as an intelligent man, thinks Holmes will be pleased with his news. Holmes rises to the occasion as best he can, calling the news “better and better” when he discovers Mary Morstan is the woman Watson has chosen, but not before he lets slip the sentence: “What I had heard of you, or perhaps what I had not heard of you, had already excited my worst suspicions.” Worst suspicions, Holmes? I thought this was supposed to be giving you pleasure? Well, perhaps he’s merely being facetious.

But next moment he slips again, saying, “You lucky fellow! I envy you.” When Watson suggests that Holmes might find a woman of his own one day, Holmes cryptically replies: “No marriage without love, Watson.” This might have been the first line that really floored me—the bare fact of Holmes’s conviction that he will never love a woman (‘woman,’ of course, being implied in the concept of marriage at the time). But when Watson asks why, Holmes falls back on the “[love] would disturb my reason” nonsense.

Now to be clear, I understand that Holmes is specifically discussing romantic love here, and that there is no connection between a lack of romantic attachment and a lack of sentiment and care for others generally. But here’s the thing: Holmes’s self descriptor doesn’t depict him as aromantic—i.e., ‘I just don’t feel romantic stuff.’ It depicts him as a reasoning machine—‘strong emotions disrupt my process.’ And in context of literally every friggin thing he does in this entire play, that’s nonsense. It is abundantly clear that reason is his tool, but compassion and sentiment are his motives.

One might argue that this is slightly sloppy writing (it was composed in a hurry, after all), or that Holmes simply doesn’t have the words to describe his aromanticism. Yet just moments before he said he envied Watson’s relationship, and moments before that revealed himself to be a consummate actor whose very existence as he knows it depends on disguise …

The already unwieldy length of this analysis requires that I speed a bit through the goldmine that follows: through Holmes punting aside requests from a royal family and the actual Pope because Watson has a case in which he has a personal interest—and I can’t resist pointing out that Holmes says he will of course take the case if Watson has “any personal interest in it.” It’s not ‘I’ll make time in my busy schedule if this is really very important to you,’ it’s ‘oh, you have a thing that you at least kinda sorta care about? The Pope can wait.’ I must gloss over Holmes transparently wanting to get as much of Watson’s company as he can, declaring that he has always seen Watson as his partner, and wishing for a plaque with his and Watson’s names on it, despite heavy implications that Watson has been almost entirely absent from Holmes’s work for some time. I’ll just mention in passing the truly remarkable number of “my dear fellows” and “my dear Watsons" Holmes manages to drop in a brief space of time, his clear desire to protect Watson from the dangers of the case despite later informing Enid that he is “a useful companion on such an occasion,” and his cry of “No, Watson, no!” when his friend leaps up to protect him from the poker Rylott is threatening him with.

I will not, however, pass over what occurs when Watson leaves Holmes, intending to meet him at the train station later that day. Watson’s final words on his way out are: “Good bye—I’ll see you at the station,” to which Holmes replies, “Perhaps you will,” adding to himself: “Perhaps you will! Perhaps you won’t!” Ah, what’s that? On about disguising yourself from your best friend again, eh Holmes? But then, within the play this refers to the fact that Holmes intends to actually disguise himself at the train station, so it has a literal meaning and not a metaphorical one, it has nothing to do with a deeper hiddeness, certainly nothing to do with love—

HOLMES: Ever been in love Billy? BILLY: Not of late years, sir. HOLMES: Too busy, eh? BILLY: Yes, Mr. Holmes. HOLMES: Same here. Got my bag there, Billy? BILLY: Yes, sir. HOLMES: Put in that revolver. BILLY: Yes, sir. HOLMES: And the pipe and pouch. BILLY: Yes, sir. HOLMES: The lens and the tape? BILLY: Yes, sir. HOLMES: Plaster of Paris, for prints? BILLY: Yes, sir. HOLMES: Oh, and the cocaine.

Oh … oh. Shit.

Please understand that this exchange—consisting of Holmes again raising the topic of love immediately after returning to the subject of his disguise, both of which he addresses as soon as Watson has left, as if he could not discuss them in front of his friend—comes apropos of nothing except Watson’s announcement of his engagement far back at the beginning of the scene. And I don’t see how the way he raises the subject and dismisses it can be seen as anything but the covering of some deep emotion—there is longing in the way he immediately brings it up, showing that it has stuck in his mind the whole while, and something tragic in the way he next-moment dismisses the clear preoccupation with the claim of being ‘too busy,’ clearly echoing the ‘I envy you … love is not for me’ progression of his earlier exchange with Watson.

And I get that in theory this longing for but dismissal of love could be read in a number of ways besides a socially forbidden love for his recently engaged partner. One might argue, for example, that he is aromantic but lonely and longing for the consistency of attachment others find in romantic love, or that he’s bursting with all sorts of hetero affections that he has chosen to sacrifice for the sake of The Work.

I would simply ask any inclined towards those arguments to consider the framing of this scene. I would ask them to question why ACD chose to introduce and conclude the scene which functions as an introduction to Holmes with the detective’s ability and need to disguise himself from Watson specifically, immediately juxtaposed with discussions of romantic love and Holmes’s desire for it which is clearly present but immediately veiled—disguised?—by his commitment to the work, with the cocaine hovering ominously behind. Then consider that between these mirrored book-ends we watch Holmes allow the man from whom he must disguise himself to disrupt the flow of the work which he claimed was supreme, making clear his wish that Watson be drawn into that work—a desire counteracted only by the transparent fact that he would prefer to risk his own bodily injury rather than put his friend in harm’s way. Add to all of this that Doyle works in a mention of the Milverton case and thus allows Holmes to comment on how his ruse to undermine Milverton involves courting and being courted by a woman and how distasteful he finds the experience and—well, you much reach your own conclusions. I have reached mine.

b.) Watson: Substitutionary desire

I began by speaking of Holmes because the subtext is monumentally more apparent on his part, and unlike Holmes it would be easy and even (though I cringe to say it) reasonable to read Watson as a comfortable heterosexual in this play. Does this mean that Doyle wrote one of those dreadful adaptations in which Holmes is pining away with an unrequited love for a Watson who is incapable of returning his romantic affections?

Not necessarily. As far as I can tell, without the clear implication of Sherlock’s affections one would be on shaky ground arguing that Watson was intended as anything besides a Hetero Bro. However, the clear coding of Holmes as in love with Watson causes one to wonder whether the affection might not be returned, and the results of investigation are inconclusive but intriguing.

Although he doesn’t make an appearance until the second act, Holme is mentioned by Watson in the first scene. Assuring Enid that she can turn to him if she is in any need, he admits that there is little he can do on his own. But he then adds: “I have a singular friend—a man with strange powers and a very masterful personality. We used to live together, and I came to know him well. Holmes is his name—Mr. Sherlock Holmes. It is to him I should turn if things looked black for you. If any man in England could help it is he.”

To be fair, it is not unusual in stories for someone to describe the hero in grandiose terms before he is seen directly by the reader/audience. Still, that’s quite a way to describe one’s friend. I find myself particularly fixating on “strange powers and a very masterful personality.” You do realize that you could have just said he’s smart, right Watson? I mean, maybe things were different back then, but if I described my friend as having a ‘masterful personality’ and then tried to claim they were my platonic bestie, I’m pretty sure I’d get my fair share of dubious glances.

Watson mentions his friend once more when his application of Holmes’s methods to clear up a detail of the investigation prompts an impressed exclamation from the coroner, to which Watson responds: “I have a friend, sir, who trained me in such matters.”

So at the very least, we have a Watson who idolizes, respects, relies on, and emulates his friend—all of which makes the fact that he is no longer living with Holmes something of a puzzle.

You see, the play never gives us a reason for Watson having moved out. The comment to Enid in which he mentions that they “used to live together” occurs two years before Sherlock becomes involved with the case and Watson becomes engaged to Mary, so it clearly has nothing to do with her. Yet not only has he moved out, his involvement in the cases is implied to have dwindled significantly or even stopped altogether—in one of the saddest lines of the play, Holmes comments that of course Watson wouldn’t remember Milverton because: “it was after your time.”

But why these degrees of separation? At no point are there signs of any ill-will between the friends. The danger certainly wasn’t an issue for Watson: when Rylott threatens Holmes Watson literally “jumps” to protect him, and he insists on sharing the danger of the Rylott house. Nor does it seem viable to speculate that Baker Street’s location became inconvenient for Watson—the speed with which Rylott makes his way to Watson’s home and from there to Baker Street demonstrates that they still live quite close. One might more plausibly theorize that Watson was becoming more invested in his medical practice and involvement in Holmes’s work was interfering, but why would ACD make an alteration so irrelevant to the story and then not even explain it? After all, the friends were still living together in the short story from which this is adapted. What could be the point of such a change?

Well, the fact is, while their bond is undeniable and remarkably strong, there are hints of something … off between the friends. Despite claiming to see Watson as his equal partner, Holmes fails to communicate with him about how they will be involved in the Rylott case, telling Watson to come on the 11:15pm train but neglecting to mention that he will be going to the house in disguise some hours earlier. The motive behind this omission is unclear—he previously tried to dissuade Watson from joining the case on account of the danger, so perhaps Holmes intends for Watson to give up and stay away when Holmes does’t appear. (Watson, of course, comes anyhow). Or perhaps Holmes wished to be apart from Watson for a time in the wake of hearing of his engagement (Holmes calling for the cocaine comes unsettlingly to mind here) but knew Watson wouldn’t allow him to go to Rylott’s alone. But whatever Holmes’s motive, Watson knows only that he has been excluded and cut out. Similarly, if in the past he has sensed that Holmes was on some level disguising himself from him would he would not have been likely to imagine a flattering cause. One cannot help but wonder whether it is these exclusions that cause Watson, despite inserting himself determinately when Holmes’s safety is at stake, to feel that he must offer to remove himself from the room when Holmes calls in clients. Certainly Watson has no inkling that Holmes might be in love with him—no kind friend who suspected as much would introduce his engagement by saying: “I came here to tell you what I am sure will please you.”

This then, is what we have: two men who deeply admire each other, long for one another’s company, and would clearly die for one another, and yet one of them is hiding and the other running first from the house and then into marriage. We have good reason to believe the one is hiding because he fears revealing his love; is it unreasonable to suppose the other is running for the same reason? Is it strange to think that Watson, feeling unable to trust to his powers of disguise in the way Holmes can, feeling the continual sting of Holmes hiding from him and cutting him off and unable to interpret those actions as anything besides distrust or indifference, would have sought safety in distance and ultimately comfort in binding himself to another?

A final note: we know nothing about Mary in this play. Despite having come in part to announce his engagement, Watson has no rhapsodies to offer on behalf of his fiancee—he seems far more interested in Holmes’s propensity for love, and, failing that, in Holmes’s work. Although Holmes’s (admittedly not impartial) deductions imply that Watson is genuinely pleased with his engagement, we learn precisely two details about Mary, both from Holmes: first that she has red hair, and second that Watson chose a woman who Holmes “met and admired.” Despite their seemingly limited contact over the past two years, Watson still seems unable to be married without at least some reference to Sherlock Holmes.

c.) Sorry … have some petty ACD as recompense

I feel I owe you an apology. I am aware that if you had the patience to read my ridiculously long ramble and are convinced by my interpretation of the Holmes and Watson’s relationship in the play, your ‘reward’ is having a dark but ultimately triumphant detective story transformed into a fucking tragedy that ends with two broken hearts. All I can offer is the comfort of knowing that for 130 years neither marriage nor death nor the near erasure of Watson from the first forty years of stage and film adaptations have been able to keep these two apart. They will find their way back to one another.

Oh, and you also might enjoy hearing that this play is totally ACD’s revenge on heteronormativity.

Okay, I can’t prove that. But it really looks like it. You may be aware of the 1988 play Sherlock Holmes, written by Doyle and William Gillette. If you’re like me a week ago, you may not know that Doyle wrote the original script himself, and Gillette became involved only when Doyle’s script was rejected and the producer urged him to bring Gillette on to rewrite it. I like to imagine that the rejection letter went something like: “Look, buddy, you can’t have Holmes staring forlornly after Watson while instigating a wistful conversation about love with Billy. You just can’t,” but realistically we don’t know why the first draft was rejected. But we do know that Doyle specifically requested that Gillette not give Holmes a (female) love interest, and that Gillette sent Holmes off into the sunset with a woman anyway (x).

Then, eleven years later with a failing theater on his hands, Doyle locks himself away in a room and says, “Fuck it. Imma write a Holmes play, and when I introduce him the first thing everyone is going to know is that he’ll never marry a woman, and the last thing the introduction will tell them is that he’ll never marry a woman and—you know what, I’ll take that Milverton story where Holmes groans about needing to date a woman and throw that in the middle.” And that’s true of the play even if you don’t buy the queer reading. But also, its super gay.

And frankly I just love that not only did Doyle refuse to give in to society’s attempt to fit his story into their heteronormative mold, it actually worked and Doyle made up all the money he was poised to lose and more by shoving a gay love story into his audience’s face.

Well done, ACD, well done.

Conclusion: Should You Read It?

I mean, I think my answer is fairly obvious by now. If you’re interested and have the time, it is 100% worth it. And I hope it doesn’t feel like I’ve spoiled all the good parts. There are reams of gems I didn’t even allude to—and that’s not counting everything I doubtless missed.

I just have one request: if you do read the play and end up posting about it on tumblr, would you tag me in your comments? Hearing someone else’s thoughts on this hidden treasure would be a delight.

@thespiritualmultinerd @a-candle-for-sherlock @missallainyus @steadymentalityengineer @iant0jones @devoursjohnlock @disregardedletters

#ACD cannon#Holmes adaptations#the adventure of the speckled band#the speckled band play#Arthur conan doyle#stage adaptation#johnlock#meta#sherlock holmes#John watson

215 notes

·

View notes