#i also know that flatland houses don’t really look like this on the interior

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

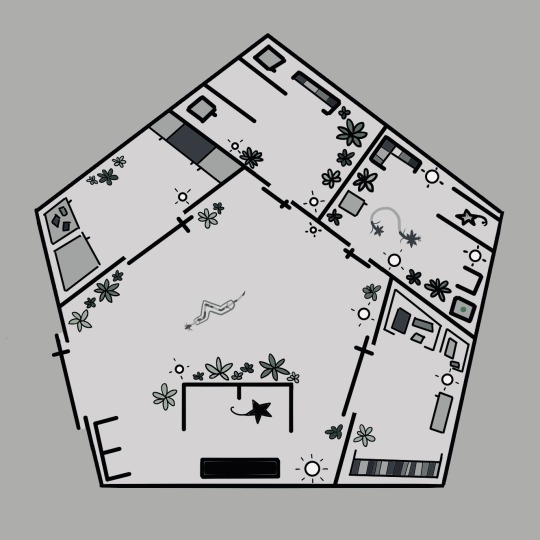

quick concept for ruth’s (and her loud roommate’s) cottage :

[Plain text ID: a digital monochrome drawing of a Flatland pentagon-shaped house with various rooms on a grey background. There are various pieces of geometric furniture inside the house, which include shapes like squares, rectangles, circles and flowers. There are four occupants of the house; two line-shaped creatures and two smaller star-shaped creatures. End ID.]

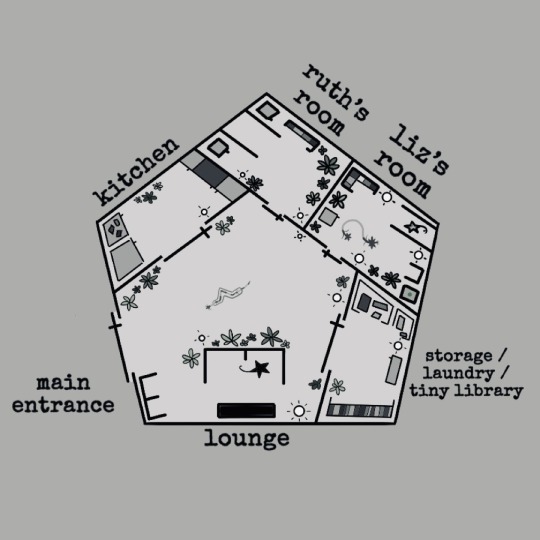

and with some room labels

[Plain text ID: the same drawing as above, but with labels added around the outside of the house. From the top centre going clockwise, the labels read as follows: "ruth's room", "liz's room", "storage / laundry / tiny library" "lounge", "main entrance" and "kitchen".

End ID.]

key under the cut

key :

✽ - houseplants

□ - closed boxes / storage structures (cabinets, etc.)

⊡ - liz’s locked box with a green colour sample

★ - cats (jinx (black cat) and socks (grey tabby))

◦ - glowpoints

▥ - ruth’s wardrobe (in ruth’s room) / liz’s wardrobe (in liz’s room) / small bookshelf (in storage / laundry / tiny library room)

E - sofa (large one) / cats’ side-by-side beds (smaller one)

▭ - television

┐and ╒╕ - open boxes / shelves

#i know half of those key symbols don’t match up to the drawing#i also know that flatland houses don’t really look like this on the interior#and that the beds are kinda their own room#but shhhhhh#drew the plants with reference to journal 3 instead of actual flatland plants like in the movie bc i am NOT doing that#forgot what tvs look like so it’s just a rectangle okay#flatland#elizabeth huntsworth#ruth galton#but i forgot the houses are pentagons and not hexagons#so i just went with it and i drew her entire house as a hexagon instead#i thought ‘wait are they actually hexagons or not’ ? NO APPARENTLY NOT#dw ruth and liz can read bc i said so <3#hence the ‘tiny library’ specifically#this has been sitting as a draft for a month now get out there girlie#will the circle be unbroken

13 notes

·

View notes