#hundreds of mrs mills records in your lifetime

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

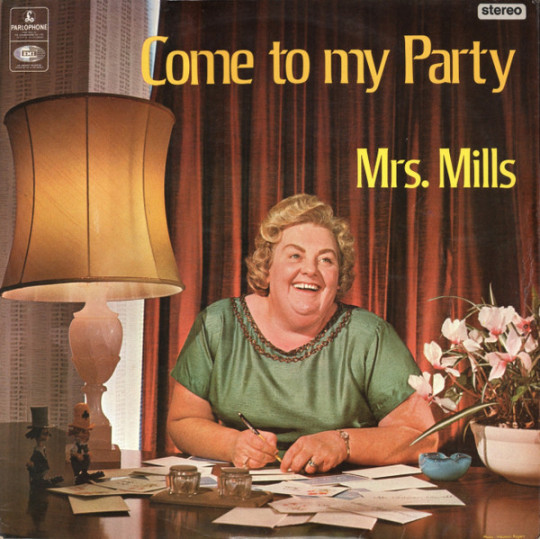

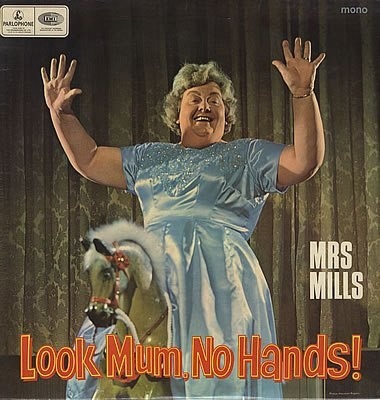

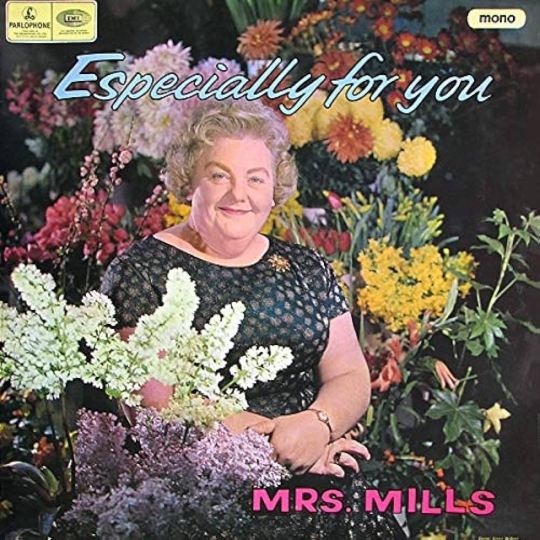

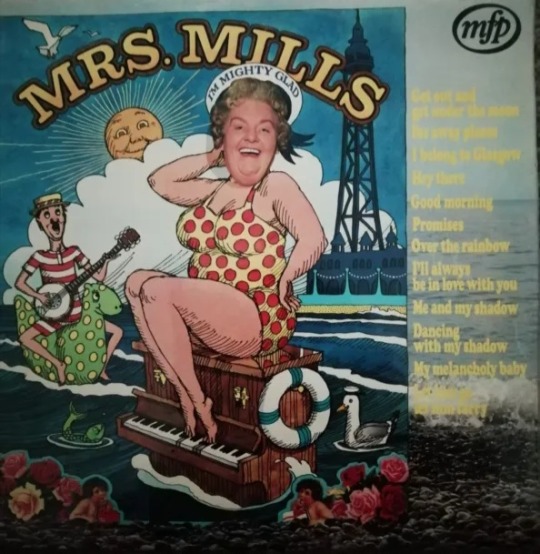

All caught up on Doctor Who now and i need fandom to know that the legendary Mrs. Mills piano that plays such a crucial role in The Devil's Chord, the one Fifteen talks about so rapturously, is a real thing and was most famously played by this woman ->

#doctor who#new who#the devil's chord#fifteenth doctor#doctor who spoilers#ncuti gatwa#doctor who series 14#mrs. mills#do not mistake me#i have nothing but love and affection for Mrs. Mills#if you're into vinyl in the uk and you've ever look for it in charity shops or cheapy junk shops then you have come across#hundreds of mrs mills records in your lifetime#the woman was a single handed recording empire‚ ludicrously prolific. her professional recording career only began in 1961 but by the end#of 63 she'd released six singles‚ three EPs and two albums; she'd release another 40 odd albums before her death in 1978#she made tv appearances‚ she was on chat shows‚ she was an institution and she was beloved!#i actually have a couple of the albums. they're............ eh. hum.#anyway. i just thought it was funny how 15 treated it like it was a holy grail of pop music (which i mean ig it is) but forgot to mention#it would be mainly used for novelty honky tonk albums for most of its working life

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lovecraft Country (2020) S01E01 “Sundown”

James Baldwin debates William F. Buckley (1965)

“Good evening,

I find myself, not for the first time, in the position of a kind of Jeremiah. For example, I don’t disagree with Mr. Burford that the inequality suffered by the American Negro population of the United States has hindered the American dream. Indeed, it has. I quarrell with some other things he has to say. The other, deeper, element of a certain awkwardness I feel has to do with one’s point of view. I have to put it that way – one’s sense, one’s system of reality. It would seem to me the proposition before the House, and I would put it that way, is the American Dream at the expense of the American Negro, or the American Dream *is* at the expense of the American Negro. Is the question hideously loaded, and then one’s response to that question – one’s reaction to that question – has to depend on effect and, in effect, where you find yourself in the world, what your sense of reality is, what your system of reality is. That is, it depends on assumptions which we hold so deeply as to be scarcely aware of them.

A white South African or Mississippi sharecropper, or Mississippi sheriff, or a Frenchman driven out of Algeria, all have, at bottom, a system of reality which compels them to, for example, in the case of the French exile from Algeria, to defend French reasons from having ruled Algeria. The Mississippi or Alabama sheriff, who really does believe, when he’s facing a Negro boy or girl, that this woman, this man, this child must be insane to attack the system to which he owes his entire identity. Of course, to such a person, the proposition which we are trying to discuss here tonight does not exist. And on the other hand, I, have to speak as one of the people who’ve been most attacked by what we now must here call the Western or European system of reality. What white people in the world, what we call white supremacy – I hate to say it here – comes from Europe. It’s how it got to America. Beneath then, whatever one’s reaction to this proposition is, has to be the question of whether or not civilizations can be considered, as such, equal, or whether one’s civilization has the right to overtake and subjugate, and, in fact, to destroy another. Now, what happens when that happens. Leaving aside all the physical facts that one can quote. Leaving aside, rape or murder. Leaving aside the bloody catalog of oppression, which we are in one way too familiar with already, what this does to the subjugated, the most private, the most serious thing this does to the subjugated, is to destroy his sense of reality. It destroys, for example, his father’s authority over him. His father can no longer tell him anything, because the past has disappeared, and his father has no power in the world. This means, in the case of an American Negro, born in that glittering republic, and the moment you are born, since you don’t know any better, every stick and stone and every face is white.

And since you have not yet seen a mirror, you suppose that you are, too. It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, or 6, or 7, to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you. It comes as a great shock to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, when you were rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians were you. It comes as a great shock to discover that the country which is your birthplace and to which you owe your life and your identity, has not, in its whole system of reality, evolved any place for you. The disaffection, the demoralization, and the gap between one person and another only on the basis of the color of their skin, begins there and accelerates – accelerates throughout a whole lifetime – to the present when you realize you’re thirty and are having a terrible time managing to trust your countrymen. By the time you are thirty, you have been through a certain kind of mill. And the most serious effect of the mill you’ve been through is, again, not the catalog of disaster, the policemen, the taxi drivers, the waiters, the landlady, the landlord, the banks, the insurance companies, the millions of details, twenty four hours of every day, which spell out to you that you are a worthless human being. It is not that. It’s by that time that you’ve begun to see it happening, in your daughter or your son, or your niece or your nephew.

You are thirty by now and nothing you have done has helped to escape the trap. But what is worse than that, is that nothing you have done, and as far as you can tell, nothing you can do, will save your son or your daughter from meeting the same disaster and not impossibly coming to the same end. Now, we’re speaking about expense. I suppose there are several ways to address oneself, to some attempt to find what that word means here. Let me put it this way, that from a very literal point of view, the harbors and the ports, and the railroads of the country–the economy, especially of the Southern states–could not conceivably be what it has become, if they had not had, and do not still have, indeed for so long, for many generations, cheap labor. I am stating very seriously, and this is not an overstatement: *I* picked the cotton, *I* carried it to the market, and *I* built the railroads under someone else’s whip for nothing. For nothing.

The Southern oligarchy, which has still today so very much power in Washington, and therefore some power in the world, was created by my labor and my sweat, and the violation of my women and the murder of my children. This, in the land of the free, and the home of the brave.And no one can challenge that statement. It is a matter of historical record.

In another way, this dream, and we’ll get to the dream in a moment, is at the expense of the American Negro. You watched this in the Deep South in great relief. But not only in the Deep South. In the Deep South, you are dealing with a sheriff or a landlord, or a landlady or a girl of the Western Union desk, and she doesn’t know quite who she’s dealing with, by which I mean, that if you’re not a part of the town, and if you are a Northern Nigger, it shows in millions of ways. So she simply knows that it’s an unknown quantity, and she wants to have nothing to do with it because she won’t talk to you, you have to wait for a while to get your telegram. OK, we all know this. We’ve been through it and, by the time you get to be a man, it’s very easy to deal with. But what is happening in the poor woman, the poor man’s mind is this: they’ve been raised to believe, and by now they helplessly believe, that no matter how terrible their lives may be, and their lives have been quite terrible, and no matter how far they fall, no matter what disaster overtakes them, they have one enormous knowledge in consolation, which is like a heavenly revelation: at least, they are not Black.

Now, I suggest that of all the terrible things that can happen to a human being, that is one of the worst. I suggest that what has happened to white Southerners is in some ways, after all, much worse than what has happened to Negroes there because Sheriff Clark in Selma, Alabama, cannot be considered – you know, no one can be dismissed as a total monster. I’m sure he loves his wife, his children. I’m sure, you know, he likes to get drunk. You know, after all, one’s got to assume he is visibly a man like me. But he doesn’t know what drives him to use the club, to menace with the gun and to use the cattle prod. Something awful must have happened to a human being to be able to put a cattle prod against a woman’s breasts, for example. What happens to the woman is ghastly. What happens to the man who does it is in some ways much, much worse. This is being done, after all, not a hundred years ago, but in 1965, in a country which is blessed with what we call prosperity, a word we won’t examine too closely; with a certain kind of social coherence, which calls itself a civilized nation, and which espouses the notion of the freedom of the world. And it is perfectly true from the point of view now simply of an American Negro. Any American Negro watching this, no matter where he is, from the vantage point of Harlem, which is another terrible place, has to say to himself, in spite of what the government says – the government says we can’t do anything about it – but if those were white people being murdered in Mississippi work farms, being carried off to jail, if those were white children running up and down the streets, the government would find some way of doing something about it. We have a civil rights bill now where an amendment, the fifteenth amendment, nearly a hundred years ago – I hate to sound again like an Old Testament prophet – but if the amendment was not honored then, I would have any reason to believe in the civil rights bill will be honored now. And after all one’s been there, since before, you know, a lot of other people got there. If one has got to prove one’s title to the land, isn’t four hundred years enough? Four hundred years? At least three wars? The American soil is full of the corpses of my ancestors. Why is my freedom or my citizenship, or my right to live there, how is it conceivably a question now? And I suggest further, and in the same way, the moral life of Alabama sheriffs and poor Alabama ladies – white ladies – their moral lives have been destroyed by the plague called color, that the American sense of reality has been corrupted by it.

At the risk of sounding excessive, what I always felt, when I finally left the country, and found myself abroad, in other places, and watched the Americans abroad – and these are my countrymen – and I do care about them, and even if I didn’t, there is something between us. We have the same shorthand, I know, if I look at a boy or a girl from Tennessee, where they came from in Tennessee and what that means. No Englishman knows that. No Frenchman, no one in the world knows that, except another Black man who comes from the same place. One watches these lonely people denying the only kin they have. We talk about integration in America as though it was some great new conundrum. The problem in America is that we’ve been integrated for a very long time. Put me next to any African and you will see what I mean. My grandmother was not a rapist. What we are not facing is the result of what we’ve done. What one brings the American people to do for all our sake is simply to accept our history. I was there not only as a slave, but also as a concubine. One knows the power, after all, which can be used against another person if you’ve got absolute power over that person.

It seemed to me when I watched Americans in Europe what they didn’t know about Europeans was what they didn’t know about me. They weren’t trying, for example, to be nasty to the French girl, or rude to the French waiter. They didn’t know they hurt their feelings. They didn’t have any sense this particular woman, this particular man, though they spoke another language and had different manners and ways, was a human being. And they walked over them, the same kind of bland ignorance, condescension, charming and cheerful with which they’ve always pat me on the head and called me Shine and were upset when I was upset. What is relevant about this is that whereas forty years ago when I was born, the question of having to deal with what is unspoken by the subjugated, what is never said to the master, of ever having to deal with this reality was a very remote possibility. It was in no one’s mind. When I was growing up, I was taught in American history books, that Africa had no history, and neither did I. That I was a savage about whom the less said, the better, who had been saved by Europe and brought to America. And, of course, I believed it. I didn’t have much choice. Those were the only books there were. Everyone else seemed to agree.

If you walk out of Harlem, ride out of Harlem, downtown, the world agrees what you see is much bigger, cleaner, whiter, richer, safer than where you are. They collect the garbage. People obviously can pay their life insurance. Their children look happy, safe. You’re not. And you go back home, and it would seem that, of course, that it’s an act of God that this is true! That you belong where white people have put you.

It is only since the Second World War that there’s been a counter-image in the world. And that image did not come about through any legislation or part of any American government, but through the fact that Africa was suddenly on the stage of the world, and Africans had to be dealt with in a way they’d never been dealt with before. This gave an American Negro for the first time a sense of himself beyond the savage or a clown. It has created and will create a great many conundrums. One of the great things that the white world does not know, but I think I do know, is that Black people are just like everybody else. One has used the myth of Negro and the myth of color to pretend and to assume that you were dealing with, essentially, with something exotic, bizarre, and practically, according to human laws, unknown. Alas, it is not true. We’re also mercenaries, dictators, murderers, liars. We are human too.

What is crucial here is that unless we can manage to accept, establish some kind of dialog between those people whom I pretend have paid for the American dream and those other people who have not achieved it, we will be in terrible trouble. I want to say, at the end, the last, is that what concerns me most. We are sitting in this room, and we are all, at least I’d like to think we are, relatively civilized, and we can talk to each other at least on certain levels so that we could walk out of here assuming that the measure of our enlightenment, or at least, our politeness, has some effect on the world. It may not.

I remember, for example, when the ex Attorney General, Mr. Robert Kennedy, said that it was conceivable that in forty years, in America, we might have a Negro president. That sounded like a very emancipated statement, I suppose, to white people. They were not in Harlem when this statement was first heard. And they’re not here, and possibly will never hear the laughter and the bitterness, and the scorn with which this statement was greeted. From the point of view of the man in the Harlem barber shop, Bobby Kennedy only got here yesterday, and he’s already on his way to the presidency. We’ve been here for four hundred years and now he tells us that maybe in forty years, if you’re good, we may let you become president.

What is dangerous here is the turning away from – the turning away from – anything any white American says. The reason for the political hesitation, in spite of the Johnson landslide is that one has been betrayed by American politicians for so long. And I am a grown man and perhaps I can be reasoned with. I certainly hope I can be. But I don’t know, and neither does Martin Luther King, none of us know how to deal with those other people whom the white world has so long ignored, who don’t believe anything the white world says and don’t entirely believe anything I or Martin is saying. And one can’t blame them. You watch what has happened to them in less than twenty years.

It seems to me that the City of New York, for example – this is my last point – Its had Negroes in it for a very long time. If the city of New York were able, as it has indeed been able, in the last fifteen years to reconstruct itself, tear down buildings and raise great new ones, downtown and for money, and has done nothing whatever except build housing projects in the ghetto for the Negroes. And of course, Negroes hate it. Presently the property does indeed deteriorate because the children cannot bear it. They want to get out of the ghetto. If the American pretensions were based on more solid, a more honest assessment of life and of themselves, it would not mean for Negroes when someone says “Urban Renewal” that Negroes can simply are going to be thrown out into the streets. This is just what it does mean now. This is not an act of God. We’re dealing with a society made and ruled by men. Had the American Negro had not been present in America, I am convinced the history of the American labor movement would be much more edifying than it is. It is a terrible thing for an entire people to surrender to the notion that one-ninth of its population is beneath them. And until that moment, until the moment comes when we, the Americans, we, the American people, are able to accept the fact, that I have to accept, for example, that my ancestors are both white and Black. That on that continent we are trying to forge a new identity for which we need each other and that I am not a ward of America. I am not an object of missionary charity. I am one of the people who built the country–until this moment there is scarcely any hope for the American dream, because the people who are denied participation in it, by their very presence, will wreck it. And if that happens it is a very grave moment for the West.

Thank you.”

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

someone to watch over me, pg, 4664 words

A very happy holiday season and the best of New Years to you, @emeraldolverqueen! You said you liked soulmate fic, so I tried to do that. It’s less Christmassy than I’d intended, but I hope you enjoy it nonetheless.

—–

She knows them longer than it took to meet herself.

That this place where she died becomes the place where they learn to live is an understanding that comes only in time – and amidst many curse words spewed among missed sips of hard liquor. Because while she’s honored to Guard them – even as far from an angel as she is, was, or ever will be – even as much as the light within them, between them, acts as a uniting beacon between their souls, guidance and a reminder that sometimes stories don’t have endings such as hers, goddamn are they frustrating sometimes.

(Because, honestly. His coffee shop was in a bad neighborhood? He ran out of sports bottles? It’s like he’s not even trying sometimes. And what, exactly, does the man have against tennis balls? Or shirts? And while she’s at it, can she just mention the entire Napa Valley worth of red wine he’ll owe his partner-slash-wife-slash-best-part-of-his-always when all this is over? But she digresses. It becomes second nature, given the many stops and starts to Oliver Queen and Felicity Smoak she has to endure but still somehow wishes she could live through.)

There is a jubilance in her when she slides quickly, hungrily, through their line together for the first time, something light that lifts her even higher than her perch Above and that she hasn’t felt, well, ever. She feels the raindrops on the window he waves rather dorkily to her when she’s too scared to come to his house; smells the flowers she brings Walter Steele in the hospital when he introduces her as his friend. Her mouth waters for the fries they order at Big Belly Burger, and her head spins just as much as Felicity’s does – will – on the power of narcotics and Oliver Queen saying she’ll always be his girl. She feels the swooping stomachs of the leaps Felicity takes, literal and figurative, to save Oliver, from Lian Yu and Ra’s al Ghul and himself time and again. Her fingers itch for the contradiction of soft butter and coarse salt on popcorn when Felicity reconfigures Oliver’s systems, and wishes she could pass it to John Diggle – who, literally, bless that man – points out Oliver doesn’t have a problem with Felicity’s performance until Barry Allen shows up. Then she wants to throw it at the looks they give each other after she locates a shipment of weapons for “Mr. Queen,” and her “a you were right and an apology; I really should be recording this,” because, just, ridiculous.

She floats at the inevitability contained in the words there was no choice to make and the redux of I know two things; the number of times they say yes even when they don’t think the other one is listening.

She is ready light years ahead of them; knows everything while they know so little.

What she doesn’t realize is how much she still has to learn herself.

She’s an eternal twenty-something when she’s finally allowed Below and sees him in person for the first time, in the place his father brings him when the son becomes the scion at barely eight, the place the young boy doesn’t want to be but where the man will try to find himself in leaps and lifetimes, fingers fidgeting for his Gameboy where in too short a time they’ll be wanting a weapon. And for the first time in generations, this isn’t the underground speakeasy where she overheard one too many men speaking down to one too many of her girls and fought back, only to get a pistol to the chest for her trouble. It’s the first moment she’s in since her soul left this place, the first thing she Sees from within rather than Above, feels deeply and is tied directly to since her time ran out, and though her lungs haven’t worked for decades, it still takes her breath away a little bit. The stacticity of the inevitability, the moveable objects and unstoppable forces, the idea that this is finally, that this is the start of a – every – moment, leaves her buzzing.

It falters ever so slightly as she takes in how much greyer the reality is against the light she sees in him, the one that shines with and partly because of a Vegas-reared card shark he’s already destined to go all in with, and the contrast is heavy enough even in its haze that it makes her realize everything she’s going to try to help them do will be caught between black and white.

It’s a lesson, a harbinger of a constant reminder that they – Oliver, Felicity, and her own being, such that it is – will forever be caught between life and death, right and wrong, light and dark, yesterday and tomorrow. She stumbles slightly against the knowledge that even though she knows what, she doesn’t know how, and she glances up for an answer she somehow knows she’ll have to live – such that it is for any and all of them – to tell.

(“The things you’ll do here will be great.” Robert Queen might say it to his son, but the woman neither know is listening hears it just as loudly. “Your work is just beginning.”

It’s truer than any of them know.)

She returns to Above to Watch the first Hanukkah after Noah Kuttler leaves, and it’s her first and greatest failure, because she has to turn away from the little girl on her eighth night lighting her menorah and speaking hitched Hebrew as she tries to pray for anything other than her greatest wish: her father to walk in the door of the home that feels less like shelter now than it ever should. She almost misses the burn of the tears on her cheek; almost wishes she could take them from the sweet little girl with glasses that fall down her nose more than they help her see, and eventually she has to turn away because she’s just not as strong as Felicity Smoak is now and forever will be.

It doesn’t matter that she can See other Hanukkahs, the ones where Felicity teaches William how to play the dreidel, or the ones where Oliver starts a list on his phone in June for gift ideas to give their children across the holiday evenings. It doesn’t matter that in the seemingly endless in-between, she Sees the there and here, how the blended family time comes together, be it margaritas after a bomb-collar wielding psycho and a gold dress that starts and stops their Witness and Oliver Queen’s hearts in the same go, or six years later, when they finally return with their son from to Star City on the 23rd of December only to find that a longtime resident who wishes to remain nameless has bought a Christmas tree at one of the downtown lots and paid the owner for weeks to keep it healthy until the castoff-turned-castaway-turned-man with too many masks until he found his true self didn’t darken doorsteps again, but instead enlightened them all with his presence.

(She’s not allowed to See that she’s the longtime resident – because she will be just that for them, longer than she’s actually supposed to be – that it’ll be one of the only times They actually let her be seen by the living world. She doesn’t know that she’ll ponder over what to say in the note she’s asked if she wants to leave, and that in the end, she’ll write with a shaking hand the only thing anyone should ever say to either of them, the things she wants them to hear echo for eternity, which is thank you and I’m proud of you.

She isn’t allowed to See, but should still know, because she yells those very things through the wandering years – Lian Yu, Hong Kong, Russia, Boston, Starling when it’s built on bones and standing on secrets – when things are so dark they seem to blind. She knows she can’t interfere; can’t change course. She knows the things she Witnesses now are the things that make them who they are, perfectly imperfect and right even in their wrongs. But the pain of it all settles in her – Oliver will later talk about five years where nothing good happens, and she’s got five times that as she Watches how the world shapes and scars their stories, and goddamn it, she hasn’t felt this helpless since she realized there was a gun in a gangster’s hand; hasn’t felt this sharp a pain since the impact of a bullet beneath her skin.

She’d waited for the light then. Now she stares at the light she’s seen in them, hoping it’ll bring her home, too.)

She begs Them time and again to let her down, a plea in a second of the infinite to remind herself it’ll be okay in how it’s meant to be; desperately needs to soothe herself with the knowledge that their path is as long as it is alight, and that the pain of the wait will lessen with whispered words of transition from “you’re my partner” to “you are my always”; from “someone’s broken our coffee maker” to a failsafe code that includes “latte” among its inspirations.

She needs to breathe those moments from her Before and their After again; needs the reassurance among the ruins.

They eventually give in, but she can’t leave the steel mill, and it’s only then that she learns moments can’t just be wished into existence, but that they have to be breathed into life, even when they feel like they’re suffocating with their entirety. She bangs her frustration on the pipes; it’s like slamming a hand against glass, starkly painful in its multitude of reminders, as they’ll experience in Darhk’s chamber, as they will when Oliver is in prison, only she doesn’t feel the inevitability of reunion then. She feels nothing but lonely and lost, wanting anything to be able to be there for them, with them, because this feels far too much like saying goodbye before introductions are even made.

It’s in that moment that she realizes that for as much as they’re going to fall for each other, she’d Fall a hundred times for them. They don’t know it yet – they may never know – but she’s just as willing to sacrifice everything for them as they will in the name of their fight for their city and for each other; for the life and liberty she won’t know again and that they’ll find only with each other.

For the love that will sustain them individually, together, apart, wholly, triumphantly, expectantly, entirely.

She makes her mind up then. She’ll stop running her parallel path, trying to get to the end because she sees how it begins, and instead Guard theirs with everything she has in her – with as much love as they’ve been destined to have for each other since before the universes within and around them had names. She’ll believe in the midst of “I don’t want to be a woman that you love” as much as she will during “you will be the best part of me for the rest of my life.” She’ll fight when he runs time and again, when she doesn’t go after him, when there are no good choices and the only certainty is failure. She’ll hear the truth in his mother’s lies, trust during so much doubting, rebuild during the wreckage.

She will Guide when they are at their most alone; even if they can’t see or hear or believe her into existence, she will be with them every step of the way, even if she has to crawl herself to get there.

(She draws the line at wiping up Roy’s training water bowls, though. Even ethereal beings have standards.)

She’s waiting at the bottom of the foundry stairs when he makes an absolute racket dragging his trunk in; “I thought you were supposed to be the shadow of the night,” she mutters as he starts putting his headquarters together. “How do you not get caught, like, forty-seven times before John and Felicity cover your ass?”

He doesn’t answer, but then again, she doesn’t need him to.

He slides into this new life almost as easily as he guides his quiver on his back; her transition is less smooth. She’s not used to interacting with the physical world anymore; time and megahertz vibrate differently, and she worries she’s leaving too much resonance as she fights between remembrance and rediscovery. He doesn’t take notice, transforming fully into something he always knew was something else, something she knows he’ll eventually understand is more, and every time the suits up – such that it his “disguise” at the beginning; it’s a hoodie. The man wears a hoodie. – she hears her and Felicity’s voices answering the question he doesn’t dare ask but that either woman he doesn’t know exist at this point would hesitate in saying: he is a hero. That he’ll go from hiding shouldering a son’s promise beneath a bruised history and the crack of leather that echoes in his aloneness to kissing his soulmate as they stand among their future and in the thick of the fight is the thing that keeps her thriving in the dank darkness of the basement; keeps her believing, and Watching, and Following.

(Tommy Merlyn feels her, though. It’s instant and obvious, and he always looks over his shoulder as they begin to set up their business and she lingers as she Watches over Oliver. It takes a few weeks, but he whispers, “Mom, is that you?” after closing late one morning. She wishes so hard that she could say something – what, she doesn’t know; what would be better, saying yes or no? – that a literal light starts to emanate from her the same way it does from Oliver and Felicity’s souls. She stands in the middle of her old building, the speakeasy that killed her, now turned into a bar hiding the man giving them both a second chance neither thought they’d get, staring at her hand as she turns it over and over again in absolute shock and disbelief.

She’s not his Caretaker, but she reaches out to him nonetheless. Her hand lingers on his shoulder, and he shudders through a deep breath as he hears the unspoken message: I’m here.

He says goodnight to her every day after that, and for all the companionship her job is predicated on, she’d never really known just how alone she’d felt.

She’s there at his End even as the foundry cracks around Felicity – as the city breaks around them all in ways that cut so deep they won’t know for so much longer just how badly they’re bleeding – and Tommy watches her in wonder and horror, glancing between his body on the ground and the sobs emanating from his best friend as Oliver begs him to open his eyes. When her hand shakes this time, it’s not entirely because she’s reaching Through for Rebecca Merlyn, but because there are no words to thank her son for the quiet conversations he’d led even without reply while restocking the bar, or the Christmas music he’d introduced her to just a few months before that he’d called classic and that she’d never heard before.

He glances between the familiar face of his mother and the scene in front of him before focusing on her, the embodiment as the confusion at the conduit of it all, and all she can do is smile.

“Take care of him,” he requests, and she nods, saying the word Oliver and Felicity will redefine for each other – have already done for her.

“Always.”)

It’s a lifetime and a half of adagio, of Waiting, but the day finally comes when he shows up in Felicity’s cubicle with a bullet-filled laptop and a bald faced lie, and it’s just…so much funnier than she expects. Of course, neither knows the monumental shift their lives have just taken, but she feels it like the electricity Felicity will soon put in his cave – his world, his heart, and how he’ll route it all back back to the woman that was always so much more than an IT girl. The look on John’s face when he wakes from his poisoning and realizes the ne’er-do-well he was supposed to be guarding is in fact guarding him makes her laugh so much it would have been audible were the rushes of both men’s heartbeats, borne of fear and confusion, not absolutely deafening.

She particularly delights in the moment when Felicity blurts out “I’m Jewish” and Oliver wishes her a Happy Hanukkah. She lingers in the QC offices as Felicity tilts her head back with an embarrassed groan once Oliver’s left the space, and can’t help but laugh as she leans against the blonde’s desk. “You marry him,” she says with utter glee and a delighted handclap not unlike the one Felicity will do when their firstborn takes her first steps toward the city Christmas tree her father once proposed to her mother by.

(She feels the shiver of the after of that moment, another cacophony of a gun and too close of a call, but she holds steadfast to the tomorrow she sees beyond it – the white lace dress and a look across a room, closeness that does not fade regardless of the distance they put between them.

She’s thought it before, but now she wonders aloud, her chin turned toward Above: why can’t this be easier for them? Why can’t the magic of a road trip summer and an unexpected home both in Ivy Town and each other last longer than a single solstice? Why can’t they have lazy Saturdays and non-burnt breakfasts instead of hostile takeovers and closing doors? Yes, they’ll have holiday plays in which one child plays the Christmas turkey on the stage and the other plays with the necklace their father gave their mother as the very first push present as they wiggle impatiently in the audience, and they’ll have William waking early one Christmas morning to mock up reindeer hoofprints in the snow, and they’ll have Hebrew school and Donna buying light-up menorahs so no flames are around her daughter or her daughter’s small children – because even at thirty, to their Nana, they’ll always be small – but words like Havenrock and Nanda Parbat and “maybe my code name could be Hot Wheels” seem to undermine the fact that he’s one of the few good ones, that she’s the last of the real ones, and she is just their Witness.

Because then they wouldn’t be Them. She hates how quickly the answer comes almost as much as she hates how true it is. But they’ve given so much up even before they have it, and it just doesn’t seem fair.

It isn’t. But it’s what makes them better.)

She stays with them after the foundry is discovered, first by Slade Wilson – and what a time she has with that madman; for all the times she’s wanted to reach out to Oliver or Felicity the way she was able to with Tommy, she is full-bodied and pissed off when he infiltrates the grave that has become the only home many of them acknowledge. He thinks she’s a figment of his imagination, a Mirakuru mirage, but instead she’s the first line of defense and the pawn in the chess game Oliver is gearing up to win.

She is red in her rage, seething in her skin – such that it is – and her voice is a hiss when it registers in his ears. “You’ve just gotten here, and you’ve already failed.”

He sets his traps, and she follows every step he stumbles through. “She’s already rebuilt this,” she says, motioning to the place that had felt like a coffin and now sings of comfort. “So has he. And they’ll do it time and again. You…” she laughs, humorlessly, hollowly. “What will you be in the end, other than a cautionary tale?”

She disappears when he swipes his sword at her, chases him around in a madness that registers a little too close for him, but she’d do anything to keep this sanctuary – the sanctity of united souls – safe. It’s why she lingers after the battle of the war no one saw coming and still somehow end one day; settles back as the unthinkable is not only spoken about but finally comes into being. Belief is truth, and it is beautiful. She enjoys those bright days even more than Oliver and Felicity will in their Porsche – Oliver Queen pretending to be confused about Ikea instructions just so Felicity will stay and help him set up the bed she insisted on buying for him is at once the dumbest and greatest thing she’s ever Witnessed, and damn it, why isn’t Caretaker popcorn an actual thing? – because it’s not just her Seeing the possibilities, the promise, the poetry even among the pain anymore.

They’re becoming them, slow and steady as it tries to be – syncopated when he makes it so, the stubborn ass; and yes, she does clang the pipes angrily – loudly – at him as he tries to settle down in the beds of his own making, cold and empty and alone – and she makes the first of her own choices.

She takes the light of that summer, of longing looks and walks for mint chocolate chip ice cream “just because” and holds it to her, even as she knows it means she can’t be there the way she wants to be, aware and awake and as alive as she can be; as she’s been for decades. She uses every ounce of energy they’ve imbued her with – both heavenly and human – and holds tight to that warmth, that belief, that righteousness, and uses it after Oliver’s own fall to soften Felicity’s descent. She uses it to fight through the biting coldness of Felicity’s despair, the pressing callousness of an empty foundry and the pain of dulled, departed souls. She clings to it while she Watches them make choice after impossible choice, after they fall apart and come together in the exquisite way only soulmates can.

She whispers it in their ears in too-empty lofts, in jail cells, in coffee houses operated alongside fake names and pink hair, and even a Dunkin Donuts in Cambridge, one Felicity frequented while at school that William makes his way to for a sense of home when he’s furthest from it.

They are her beacon as much as they are each other’s, and keeps it alight during the dark days and the navy nights.

(The second choice she makes – though doing so contradicts this ones made for her before the Beginning – is to stay long after Quentin Lance finds the foundry and shuts it down. She’s not tied to the place anymore, and should go back Above. She refuses, because if she’s learned one thing from them, it’s that you never abandon the fight. Though they don’t know she’s there, she’s still tied to them, and they have many miles to go before any of them can sleep.

There’s also a small part of her that wonders if they do know she’s there, because after the first date they both believed to be the last, Felicity appears in front of her, shimmering and shaking as brightly as the wedding rings she can’t see but that her Guardian won’t forget, bloody but beautifully aware in her red dress, even as her body lies unconscious and unmoving on a table.

“Is this…Heaven?” she asks brokenly. “Because that would be inconvenient on so many levels.”

She’s thought a hundred times – a thousand – about what she’d say to this beautiful creature if ever given the chance. Would she want to laugh with her; tease her a little bit about just how exhausting the will they/won’t they scenario was when the answer was most obviously duh. Would she be serious; speak about how for as much as she’d fought Oliver’s corner and is helping the world understand he’s a hero, she’s one in her own very big right, that she’s changed just as many lives as Oliver’s changed hers, that she’s as strong as anyone could hope to be and learned it only from herself? In the moment, she just stares, her mind racing to remind Felicity to believe when everything is broken, to relish the calm after the storm even as she loathes its furious existence; wants to beg her not to let either of them run unless it’s to each other. She wants to show her all the things she Sees – has Seen – how she’ll lose too much but find herself in the end, that she’ll hold her husband’s hand until he’s 86 and she’ll follow shortly thereafter with a smile on her face and peace in her heart because the only place they were ever supposed to be was together; wants to tell her how damn proud she is of all of them. How she’ll cheer when Felicity Smoak stares down every fool that dares cross her path, whether it’s the madman-hellbent-on-revenge du jour or her three-year-old who very clearly got into Oliver’s homemade cookies before bed and is shaking a familiarly curly head in denial even with chocolate chip smeared all over their face; how she’ll be shaking a pipe in celebration as Felicity cuts the ribbon on a building bearing her name, and how she’ll do the same at Oliver’s nonprofit office when it’s time for him to head home for dinner with his wife and family.

She wants to tell her the one thing she wishes she’d heard at her End: it’s all going to be okay.

She doesn’t say that, though, even if it’s true. Because what’s even truer – what’s even more important – is that it’s all going to be worth it.

All of it – the lies, the tears, the tribulations – will pale in comparison to vividity of the triumph. These days are long and hard, but the one thing that has never changed – will never change – is the light inside them. It’s not even just their souls anymore; not just them with each other. It’s a beacon, a road home. It’s a journey and a destination and a beginning and an ending, and it’s the most beautiful thing any of them will ever see.

She doesn’t say much, actually, because there’s just too many things to note. Instead, she follows the heart Felicity helped both her and Oliver realize they’d never lost, and the words that finally come out are instinctual. “No, my love,” she says softly, sweetly, and with a smile even as her heart bursts and breaks at the same time, because the woman in front of her really is remarkable. “It’s not.” She swallows, closes her eyes and reaches out for Felicity’s hand – not because she doesn’t know what’ll happen, but because this is something she needs to remember. “Your work is far from finished, but you’re doing great, great things.”

“I – I don’t understand,” Felicity says, glancing behind her, her body leaning toward Oliver in the same way their souls yearn for each other.

“That’s okay,” she replies. “I know enough for the both of us.”

The moment she touches the blonde, everything snaps back in place, and Felicity bolts upright with one name on her lips; the most important one.

The last one she ever says in the foundry, though, comes years and understandings later, after so much as fallen, but more importantly, has been reclaimed again. There’s a single rose in her weathered hand and an even older newspaper article folded in her pocket.

“Thank you, Millie,” Felicity whispers as she lays the flower on the spot the paper said the woman passed away on, stopping with a smile when the pipes clang noisily one last time.

“No, Felicity,” Millie whispers as she rises Above just as their souls have time and again, “thank you.”)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cumberland, Maryland Investment In Cryptocurrencies Could Guarantee A Bright Fiscal Future

This is a letter I submitted to the Cumberland Times News, my local newspaper, on October 5th, 2017 via email. I have neither heard back from them nor seen this in print unless I have overlooked something. I find it critically important to share this idea that I find as a very progressive solution two the possibility of financial issues in the future. If you want to have success in the future then you invest today !!! There has never been growth in any Marketplace like the record-setting growth of crypto currencies and if we had invested earlier this year at a little over $600 a piece, today we would own Bitcoins with a value each of roughly $4000 to $5,000 +, and quickly increasing. In fact, John McAfee, of the very famous McAfee Antivirus company and other fame, thinks that his statement that Bitcoin will reach $500,000 per each Bitcoin in 10 years or less is an absolute under estimate. Cryptocurrencies will eliminate banking as we know it today completely !!! You do not have to listen to a single thing I have to write hear about crypto-currencies cuz you can read all about it here from the original document. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf&ved=0ahUKEwjstpylmf7WAhVC4SYKHZtzA0gQFggmMAA&usg=AOvVaw05-4mYD7EyyKjwcHh8i0Vw [PDF] Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System - Bitcoin.org Bitcoin.org › bitcoin Don't be ignorant !!! Do your due diligence and understand that this is a critical move our city can make that can set a precedence across the world so that other municipalities, counties, jurisdictions, Etc can plan on making an Investment Portfolio that will Garner dividends in the future to offset shortfalls in the budget at a minimum. We consistently pay tens of thousands of dollars for studies that tell us stuff that we already know about our area. We pay these tens of thousands of dollars in studies so that we will have directives on paper to do the things you would think we should already know to be doing. Too often I see these types of reports to be just complete waste of money where the real money that could be the security and the further Rebirth of the city. ---------------------------------------------------------------- I am a city resident here in Cumberland, Maryland and have been since 2001 where I own my own home. I believe the city should invest a minimum consideration of $10,000 in crypto currency, if not substantially more!!! I believe we should sell public investment savings bonds, or some type of public bond we design to legal specifics, to our residents and county residents, as well as Maryland residents and anybody else who wants to buy them. We can have a 10-year investment plan, or so, maybe one for 5 and one for 10 years, for crypto currency investment, where it's kept under lock and key until we say it's mature in 10 years and we then want to use some of those funds towards the cities expenditures and more importantly future Investments as we build foundations with vision. You have to think about what I'm going to say below and who I got permission from as well as what John McAfee says and what he thinks one single Bitcoin will be worth (soon...not tomorrow), which is a half million dollars EACH... and today one Bitcoin as roughly $4,200. John says that's actually an underestimate. At the beginning of the year the price was just $620 per Bitcoin. Nothing has ever displayed such incredible growth in investing history!!! Nothing is ever displayed so much potential for future growth either and it is incredible to watch and equally nor such volatility. We cannot forget every coin has two sides as well as an edge which can later cut like a knife, not to ever be overlooked of course... and this is where and why some form of diversity must be considered. I went to school with Michael Novogratz in high school... Just look up Galaxy Investment Partners. You may do your own due diligence to see who he is and that he highly recommends crypto currencies, and that he would not do this without certain knowledge. I'm not claiming Mr. Novogratz as a close personal friend, however a definite acquaintance and alumni of the same high school with similar upbringings, we wrestled together and, most recently, just several years ago, he read some of my poetry at a rather large group. https://www.coinspeaker.com/2017/09/28/fortress-former-cio-michael-novogratz-establishes-worlds-biggest-crypto-hedge-fund/amp/ Mathematically $10,000 over 10 years will look insignificant as an investment and may garner this city several million, tens of millions, maybe even hundreds of millions of dollars in the coming decade when it matures !!! If indeed we could ever coordinate something like this, which always seems to be the biggest problem… “the inability to act swiftly with efficiency and without division”... well... maybe... we would indeed have an ace in the hole !!! Otherwise,... this might be our very epitaph as an incorporated city ! John Stephen Swygert Steve Swygert ----- Addition: The truth is I lied in my article above. I believe we should invest a million but the shock value of a million dollars to all of the taxpayers here would just blow the entire idea up before those that are ignorant would do their own due diligence to understand what crypto currency even is for to study the growth That it is on. I have studied these and depth and I am continuing to study crypto currencies and this is absolutely the most and credible investment opportunity that we will see for the rest of our lifetimes ! This will give Cumberland any type of future we desire to construct together if we make the investment and if we don't it might just be the end! We have a county that suggest giving up our city Charter. I have a VOTE that suggests that we have better representation that instead of slinging absolutely despicable remarks, would instead suggest a solution as I have! http://www.times-news.com/news/local_news/county-declines-to-fund-cumberland-s-requests/article_11c1392b-138c-5471-8d33-09b4592f4a69.html I believe in thinking outside of the box so I can stay out of the box a little bit longer! Here are some more facts. I am the one who coined this expression, "Be Bold, Embrace Change". #BeBold I offered my expression to be utilized but I did not know what it would be utilized for. Far before the rolling Mills project came to fruition I suggested personally face-to-face to our mayor that the most Progressive cities in the country, and indeed in the world today, invest in themselves and they buy entire city blocks two remove old Urban Decay so that there will be renewal. If the city will not invest in itself who will believe in that city? I understand this critically, and I also understand the criticalities of those in the Rolling Hills subdivision that did not want to leave their homes ! Personally, I would give my home up if I was made completely whole and offered another home in the city where I want to live. However what makes one completely whole versus another person complete a hole is two entirely different sets of Standards most often and of course we are now at this critical juncture where the city needs to decide if they want to use eminent domain to remove the remaining residents or to build around as you can read for yourself in this article and I don't want to get into these details as this has not been something I have ever been involved with other than my original suggestion, which I am not taking credit for the overall idea however it very well could be mine as you see my slogan is attached to the entire idea that was executed by the Cumberland Economic Development Commission. I'm not trying to make a penny off of anything, I am simply suggesting progressive solutions so that our area can indeed have a future and that future needs to be built upon solid foundations today and we are going to need finances for this solid foundations and right now we have crumbling infrastructure !!! Currently, via a leak of unknown origin, it's estimated that the sewage system in the city is leaking about 80,000 gallons of raw sewage into Wills Creek, for example, because we cannot find the leak. 80000 gallons of raw sewage a day into a creek EVERY DAY !!! http://www.times-news.com/news/local_news/city-leak-spewing-gallons-of-sewage-daily-into-wills-creek/article_3f54c6b4-6958-5651-93cf-2465bee413ba.html We consistently have to repair water mains because they break in the next one down the line which is of least resistance brakes or they break between the mains but typically at the mains and we continue to throw money at these things when what really needs to be done is the complete removal and replacement of entire systems of which it has been said there are no records of as they have been... well who knows what !!! I am frustrated and I'm sure some of that shines through here and I am sorry for that little edge of anger however again I am simply looking for Solutions and I am only looking towards Visionary plans that will guarantee in a sure that there will be a great future here in Cumberland because the people here deserve that !!! Perhaps for each person in the rolling Mills subdivision $5,000 in the Bitcoin can be invested and held for 10 years so that they can each be made whole as well (possibly as nothing is without risk) and I mean each and every single person displaced from that entire community. That means the deals already done and the deals that need to be done still. Imagine if after the fact the city gave gifts to the willing citizens that were made to make a very tough decision. I personally appreciate your bold choices to move forward and therefore let our city move forward too. #CumberlandCrypto #CumberlandCrypto #GalaxyInvestnents #CumberlandMarylabd #Bitcoin

0 notes

Video

youtube

James Baldwin debates William F. Buckley on "Is the American dream at the expense of the American negro?" at The Cambridge Union in 1965. Buckley defends racism and bigotry as States Rights issues. Baldwin's thesis is favored by students: 540-160 (vote).

Baldwin's transcript:

Good evening,

I find myself, not for the first time, in the position of a kind of Jeremiah. For example, I don’t disagree with Mr. Burford that the inequality suffered by the American Negro population of the United States has hindered the American dream. Indeed, it has. I quarrell with some other things he has to say. The other, deeper, element of a certain awkwardness I feel has to do with one’s point of view. I have to put it that way – one’s sense, one’s system of reality. It would seem to me the proposition before the House, and I would put it that way, is the American Dream at the expense of the American Negro, or the American Dream *is* at the expense of the American Negro. Is the question hideously loaded, and then one’s response to that question – one’s reaction to that question – has to depend on effect and, in effect, where you find yourself in the world, what your sense of reality is, what your system of reality is. That is, it depends on assumptions which we hold so deeply so as to be scarcely aware of them.

Are white South African or Mississippi sharecropper, or Mississippi sheriff, or a Frenchman driven out of Algeria, all have, at bottom, a system of reality which compels them to, for example, in the case of the French exile from Algeria, to offend French reasons from having ruled Algeria. The Mississippi or Alabama sheriff, who really does believe, when he’s facing a Negro boy or girl, that this woman, this man, this child must be insane to attack the system to which he owes his entire identity. Of course, to such a person, the proposition which we are trying to discuss here tonight does not exist. And on the other hand, I, have to speak as one of the people who’ve been most attacked by what we now must here call the Western or European system of reality. What white people in the world, what we call white supremacy – I hate to say it here – comes from Europe. It’s how it got to America. Beneath then, whatever one’s reaction to this proposition is, has to be the question of whether or not civilizations can be considered, as such, equal, or whether one’s civilization has the right to overtake and subjugate, and, in fact, to destroy another. Now, what happens when that happens. Leaving aside all the physical facts that one can quote. Leaving aside, rape or murder. Leaving aside the bloody catalog of oppression, which we are in one way too familiar with already, what this does to the subjugated, the most private, the most serious thing this does to the subjugated, is to destroy his sense of reality. It destroys, for example, his father’s authority over him. His father can no longer tell him anything, because the past has disappeared, and his father has no power in the world. This means, in the case of an American Negro, born in that glittering republic, and the moment you are born, since you don’t know any better, every stick and stone and every face is white.

And since you have not yet seen a mirror, you suppose that you are, too. It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, or 6, or 7, to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you. It comes as a great shock to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, when you were rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians were you. It comes as a great shock to discover that the country which is your birthplace and to which you owe your life and your identity, has not, in its whole system of reality, evovled any place for you. The disaffection, the demoralization, and the gap between one person and another only on the basis of the color of their skin, begins there and accelerates – accelerates throughout a whole lifetime – to the present when you realize you’re thirty and are having a terrible time managing to trust your countrymen. By the time you are thirty, you have been through a certain kind of mill. And the most serious effect of the mill you’ve been through is, again, not the catalog of disaster, the policemen, the taxi drivers, the waiters, the landlady, the landlord, the banks, the insurance companies, the millions of details, twenty four hours of every day, which spell out to you that you are a worthless human being. It is not that. It’s by that time that you’ve begun to see it happening, in your daughter or your son, or your niece or your nephew.

You are thirty by now and nothing you have done has helped to escape the trap. But what is worse than that, is that nothing you have done, and as far as you can tell, nothing you can do, will save your son or your daughter from meeting the same disaster and not impossibly coming to the same end. Now, we’re speaking about expense. I suppose there are several ways to address oneself, to some attempt to find what that word means here. Let me put it this way, that from a very literal point of view, the harbors and the ports, and the railroads of the country–the economy, especially of the Southern states–could not conceivably be what it has become, if they had not had, and do not still have, indeed for so long, for many generations, cheap labor. I am stating very seriously, and this is not an overstatement: *I* picked the cotton, *I* carried it to the market, and *I* built the railroads under someone else’s whip for nothing. For nothing.

The Southern oligarchy, which has still today so very much power in Washington, and therefore some power in the world, was created by my labor and my sweat, and the violation of my women and the murder of my children. This, in the land of the free, and the home of the brave.And no one can challenge that statement. It is a matter of historical record.

In another way, this dream, and we’ll get to the dream in a moment, is at the expense of the American Negro. You watched this in the Deep South in great relief. But not only in the Deep South. In the Deep South, you are dealing with a sheriff or a landlord, or a landlady or a girl of the Western Union desk, and she doesn’t know quite who she’s dealing with, by which I mean, that if you’re not a part of the town, and if you are a Nothern Nigger, it shows in millions of ways. So she simply knows that it’s an unknown quantity, and she wants to have nothing to do with it because she won’t talk to you, you have to wait for a while to get your telegram. OK, we all know this. We’ve all been through it and, by the time you get to be a man, it’s very easy to deal with. But what is happening in the poor woman, the poor man’s mind is this: they’ve been raised to believe, and by now they helplessly believe, that no matter how terrible their lives may be, and their lives have been quite terrible, and no matter how far they fall, no matter what disaster overtakes them, they have one enormous knowledge in consolation, which is like a heavenly revelation: at least, they are not Black.

Now, I suggest that of all the terrible things that can happen to a human being, that is one of the worst. I suggest that what has happened to white Southerners is in some ways, after all, much worse than what has happened to Negroes there because Sheriff Clark in Selma, Alabama, cannot be considered – you know, no one can be dismissed as a total monster. I’m sure he loves his wife, his children. I’m sure, you know, he likes to get drunk. You know, after all, one’s got to assume he is visibly a man like me. But he doesn’t know what drives him to use the club, to menace with the gun and to use the cattle prod. Something awful must have happened to a human being to be able to put a cattle prod against a woman’s breasts, for example. What happens to the woman is ghastly. What happens to the man who does it is in some ways much, much worse. This is being done, after all, not a hundred years ago, but in 1965, in a country which is blessed with what we call prosperity, a word we won’t examine too closely; with a certain kind of social coherence, which calls itself a civilized nation, and which espouses the notion of the freedom of the world. And it is perfectly true from the point of view now simply of an American Negro. Any American Negro watching this, no matter where he is, from the vantage point of Harlem, which is another terrible place, has to say to himself, in spite of what the government says – the government says we can’t do anything about it – but if those were white people being murdered in Mississippi work farms, being carried off to jail, if those were white children running up and down the streets, the government would find some way of doing something about it. We have a civil rights bill now where an amendment, the fifteenth amendment, nearly a hundred years ago – I hate to sound again like an Old Testament prophet – but if the amendment was not honored then, I would have any reason to believe in the civil rights bill will be honored now. And after all one’s been there, since before, you know, a lot of other people got there. If one has got to prove one’s title to the land, isn’t four hundred years enough? Four hundred years? At least three wars? The American soil is full of the corpses of my ancestors. Why is my freedom or my citizenship, or my right to live there, how is it conceivably a question now? And I suggest further, and in the same way, the moral life of Alabama sheriffs and poor Alabama ladies – white ladies – their moral lives have been destroyed by the plague called color, that the American sense of reality has been corrupted by it.

At the risk of sounding excessive, what I always felt, when I finally left the country, and found myself abroad, in other places, and watched the Americans abroad – and these are my countrymen – and I do care about them, and even if I didn’t, there is something between us. We have the same shorthand, I know, if I look at a boy or a girl from Tennessee, where they came from in Tennessee and what that means. No Englishman knows that. No Frenchman, no one in the world knows that, except another Black man who comes from the same place. One watches these lonely people denying the only kin they have. We talk about integration in America as though it was some great new conundrum. The problem in America is that we’ve been integrated for a very long time. Put me next to any African and you will see what I mean. My grandmother was not a rapist. What we are not facing is the result of what we’ve done. What one brings the American people to do for all our sakes is simply to accept our history. I was there not only as a slave, but also as a concubine. One knows the power, after all, which can be used against another person if you’ve got absolute power over that person.

It seemed to me when I watched Americans in Europe what they didn’t know about Europeans was what they didn’t know about me. They weren’t trying, for example, to be nasty to the French girl, or rude to the French waiter. They didn’t know they hurt their feelings. They didn’t have any sense this particular woman, this particular man, though they spoke another language and had different manners and ways, was a human being. And they walked over them, the same kind of bland ignorance, condescension, charming and cheerful with which they’ve always pat me on the head and called me Shine and were upset when I was upset. What is relevant about this is that whereas forty years ago when I was born, the question of having to deal with what is unspoken by the subjugated, what is never said to the master, of ever having to deal with this reality was a very remote possibility. It was in no one’s mind. When I was growing up, I was taught in American history books, that Africa had no history, and neither did I. That I was a savage about whom the less said, the better, who had been saved by Europe and brought to America. And, of course, I believed it. I didn’t have much choice. Those were the only books there were. Everyone else seemed to agree.

If you walk out of Harlem, ride out of Harlem, downtown, the world agrees what you see is much bigger, cleaner, whiter, richer, safer than where you are. They collect the garbage. People obviously can pay their life insurance. Their children look happy, safe. You’re not. And you go back home, and it would seem that, of course, that it’s an act of God that this is true! That you belong where white people have put you.

It is only since the Second World War that there’s been a counter-image in the world. And that image did not come about through any legislation or part of any American government, but through the fact that Africa was suddenly on the stage of the world, and Africans had to be dealt with in a way they’d never been dealt with before. This gave an American Negro for the first time a sense of himself beyond the savage or a clown. It has created and will create a great many conundrums. One of the great things that the white world does not know, but I think I do know, is that Black people are just like everybody else. One has used the myth of Negro and the myth of color to pretend and to assume that you were dealing with, essentially, with something exotic, bizarre, and practically, according to human laws, unknown. Alas, it is not true. We’re also mercenaries, dictators, murderers, liars. We are human too.

What is crucial here is that unless we can manage to accept, establish some kind of dialog between those people whom I pretend have paid for the American dream and those other people who have not achieved it, we will be in terrible trouble. I want to say, at the end, the last, is that is that is what concerns me most. We are sitting in this room, and we are all, at least I’d like to think we are, relatively civilized, and we can talk to each other at least on certain levels so that we could walk out of here assuming that the measure of our enlightenment, or at least, our politeness, has some effect on the world. It may not.

I remember, for example, when the ex Attorney General, Mr. Robert Kennedy, said that it was conceivable that in forty years, in America, we might have a Negro president. That sounded like a very emancipated statement, I suppose, to white people. They were not in Harlem when this statement was first heard. And they’re not here, and possibly will never hear the laughter and the bitterness, and the scorn with which this statement was greeted. From the point of view of the man in the Harlem barber shop, Bobby Kennedy only got here yesterday, and he’s already on his way to the presidency. We’ve been here for four hundred years and now he tells us that maybe in forty years, if you’re good, we may let you become president.

What is dangerous here is the turning away from – the turning away from – anything any white American says. The reason for the political hesitation, in spite of the Johnson landslide is that one has been betrayed by American politicians for so long. And I am a grown man and perhaps I can be reasoned with. I certainly hope I can be. But I don’t know, and neither does Martin Luther King, none of us know how to deal with those other people whom the white world has so long ignored, who don’t believe anything the white world says and don’t entirely believe anything I or Martin is saying. And one can’t blame them. You watch what has happened to them in less than twenty years.

It seems to me that the City of New York, for example – this is my last point – It’s had Negroes in it for a very long time. If the city of New York were able, as it has indeed been able, in the last fifteen years to reconstruct itself, tear down buildings and raise great new ones, downtown and for money, and has done nothing whatever except build housing projects in the ghetto for the Negroes. And of course, Negroes hate it. Presently the property does indeed deteriorate because the children cannot bear it. They want to get out of the ghetto. If the American pretensions were based on more solid, a more honest assessment of life and of themselves, it would not mean for Negroes when someone says “Urban Renewal” that Negroes can simply are going to be thrown out into the streets. This is just what it does mean now. This is not an act of God. We’re dealing with a society made and ruled by men. Had the American Negro had not been present in America, I am convinced the history of the American labor movement would be much more edifying than it is. It is a terrible thing for an entire people to surrender to the notion that one-ninth of its population is beneath them. And until that moment, until the moment comes when we, the Americans, we, the American people, are able to accept the fact, that I have to accept, for example, that my ancestors are both white and Black. That on that continent we are trying to forge a new identity for which we need each other and that I am not a ward of America. I am not an object of missionary charity. I am one of the people who built the country–until this moment there is scarcely any hope for the American dream, because the people who are denied participation in it, by their very presence, will wreck it. And if that happens it is a very grave moment for the West.

Thank you. [h/t]

#1965#james baldwin#william f. buckley#william f buckley#video#youtube#debate#debates#rip#black excellence#racism#bigotry#amerikkka

0 notes