#how many times can my entire worldview change in 24 hours

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Another Life - Chapter 10

Fandom: What We Do in the Shadows

Pairing: Vladislav x Reader

Series Rating: M

Word Count: 1838

Chapter Summary: You clear the air with all four flatmates.

A/N: As always, cross posted to AO3.

Warning: Brief mentions of suicidal ideation.

You entered the lounge in your pajamas, your face already washed, and your hair messy. You collapsed onto the couch and started scrolling through your phone, making excellent progress on spending the evening in a near vegetative state.

“You’re not going out tonight?” Dawn asked.

You didn’t look up from your phone. “No. It’s been weeks. That guy’s not coming back; I scared him off for good. So I figured I might as well stay home until my depressive state killed me, quite possibly by my own hand,” you deadpanned.

“Y/N. That’s not funny.”

“Sorry.”

Changing the subject from your macabre exaggeration, Dawn suggested, “Let’s go out tonight.”

You threw her a look.

“No, really. Like actually out. Not just you sitting alone and sad at bar waiting for someone you may or may not have known to show up. Let’s go out, you and me, for a girl’s night. We’ll go out for drinks and dancing. Not Boogie Wonderland. You need a break from that place. Some other club.”

“Rain check?” You didn’t feel like going out. You didn’t feel like having fun. You felt like lying on the couch until you wasted away.

“I don’t think that’s a good idea. I’m really worried about you.”

You brushed off her comment, but you were getting sort of worried about yourself, as well. You’d stopped going to see your psychologist. Earlier in the day you found yourself wishing you would go to sleep and just not wake up. You were constantly miserable, surviving but not living.

“Well if you really don’t want to go out, why don’t we stay in and have a movie night? I’ll rent something online and then order a pizza, my treat, okay?”

You didn’t really feel like doing anything, but you recognized that Dawn was trying her best, and you appreciated it. And watching a movie and binging on pizza in your pjs seemed much more manageable that getting dressed up to go out and party.

You nodded. “Okay. Thanks.”

~

The kitchen table was much too small for all five of you. Your elbows bumped either Vladislav on your left or Petyr on your right every time you shifted. Petyr sort of gave you the heebie jeebies, so you found yourself leaning slightly away from him, putting you uncomfortably close to Vladislav. You suggested relocating to the dining room, but were told that it was currently covered in blood and had a corpse laying on the table. You weren’t sure what was more unsettling, the fact that that was the state of the dining room, or that that news was delivered to you so nonchalantly. Nevertheless, the dining room was to an option, so you were all squeezed around the tiny kitchen table.

Viago cleared his throat before beginning. “We are here to clear the air about our being vampires and discuss our living situation with Y/N. It might be helpful if we reintroduced ourselves, properly, this time. I’ll go first.” He turned to address you directly. I am Viago Von Dorna Schmarten Scheden Heimburg.”

You stared blankly.

“Oh, and I’m 379 years old,” he added as an afterthought.

You tried to do the mental math in your head, but quickly gave up and decided to figure it out later.

“Deacon Brucke. I’m 183 years old.”

“Vladislav the Poker. 862 years old.”

He might not have been kidding about the Middle Ages last night, after all. You turned to Petyr, anticipating his introduction.

“Petyr,” he rasped, his voice as cold and creepy as the rest of him.

You waited for his age, but he stared blankly at you with his pale eyes, not volunteering any further information.

“We don’t know how old Petyr is,” Viago explained. “He lost track. Over 8,000, though.”

Your jaw dropped. “For real?”

Your turned back to Petyr and he nodded once. Shit. Okay, then.

Viago continued, “Y/N, do have any questions about vampires in general or specifically about any of us?”

You figured a general ‘Tell me about vampires.’ was too open-ended, and you tried to think of a more specific question. You had a lot of questions, though, and you didn’t know where to start. You also had some vague ideas and assumptions about vampires, but you didn’t know which, if any, were true. “How about I just tell you what I’ve heard about vampires, and you guys can correct me where I’m wrong and fill in the gaps. Does that work?”

The four looked to one another before nodding.

“So, you-“ You realized you didn’t quite feel comfortable referring to them as vampires, so you restarted, more generally. “So, vampires need to consume human blood. They sleep in coffins, during the day. Sunlight, garlic, silver, and crosses are all bad for them.” You looked around to see that all four were still nodding along, so you continued, rattling things off a bit faster. “Not showing up in mirrors, turning into bats, flying, having to be invited in, wooden stakes, hypnosis, and whatever Deacon did with that guy’s backpack.”

“Teleportation,” Deacon clarified.

You nodded, but tried not to give it too much thought. Watching him crawl out of that backpack was easily the most horrifying thing you’d ever encountered, and you felt the ball of fear and anxiety in your stomach return just remembering it.

“Vampires also have quicker and superior healing ability than humans.”

“And it’s not just bats,” Deacon added. “Cats and dogs, too. But with practice it can be any animal. Vladislav is known for his transformation abilities.”

Vladislav smiled proudly. “That’s not practice, though, that’s skill.”

“Ja, some vampires have certain abilities that other vampires don’t. I once met a vampire who could become invisible,” Viago explained.

“It isn’t just crucifixes, either.” Vladislav glanced quickly to your chest where he knew your necklace hung. “It’s any religious icons or words.”

“Really? Words? Like even if I just say ‘god’-“

You were cut off by wincing and hissing from around the table.

“Don’t do that!” Deacon scolded you.

“Shit. Sorry.” As frightening as vampires inherently were, it made you feel better that they had their weaknesses. “So is it just vampires? That are real, I mean? Or is every mythological creature real? Do I need to be on the lookout for, like, ghosts?”

“Ghosts aren’t real,” Deacon scoffed.

“Of course ghosts are real,” Viago argued.

“Oh really? Have you ever seen a ghost?”

“Not technically. But the house I grew up in was haunted! There was a spirit who lived in the walls.”

“There was not. It was probably a rat.”

“You think I would confuse a rat for a ghost?”

“So, there’s no reason for me to change my thoughts on ghosts?” you interrupted.

“Ghosts are real,” Vladislav answered. You took it with a grain of salt, though. “Werewolves are real, too.” The rest of the group nodded. “I wouldn’t go out on full moons, if I were you. There is a pack that roams in Te Aro.”

That thought chilled you. You were sure you’d gone out in Te Aro on a full moon before. Then again, you’d gone out many times before unaware that there were vampires, including your current flatmates, out and about.

“Zombies and witches, too.”

“We’re not sure what all exists,” Viago told you. “Lots of myths are true, and lots aren’t. Some Maori myths are based on real creatures.”

“Oh! Petyr, remember the taniwha that attacked our ship when we came to New Zealand?”

Petyr nodded solemnly.

Vampires, werewolves, assorted creatures. Your entire worldview was being forcibly changed over these past 24 hours, but you just nodded. What else could you do?

“I’m safe, right?” you asked suddenly. “From you guys? I mean, there’s literally a dead body in the other room.” You were afraid it sounded more accusatory than you meant it, but you felt it was a fair question, all in all.

“We can control ourselves,” Deacon said, somewhat indignantly.

“You’re our flatmate and our friend. You don’t have to worry.”

“Thanks.” You thought it was odd to thank someone for not killing you, but you didn’t know what else to say. “Is there anything you guys need from me? As a human flatmate? Other than not slamming the doors and being quiet during daylight hours?”

“Don’t tell anyone we’re vampires,” Vladislav said sternly. “Not anyone. Not ever. Vampire hunters are also real and when word gets out that you are a vampire, you tend not to be around soon after.” He, as well as the other three, looked deadly serious.

You nodded quickly to reassure them. “I won’t tell anyone.” You looked around the table. Everyone was still seated, though it felt like the natural conclusion to the flat meeting. “About the dining room…?”

“Jackie will be here to clean it up later tonight,” Deacon said.

“Is she a vampire, too?”

“No. She is my familiar.”

“Familiar?” To you, the word conjured images of black kittens following cartoon witches on broomsticks. You weren’t sure how the term applied to the woman you’d once met.

“Slave,” Vladislav clarified.

You looked at him in shock, and he returned your gaze, shameless and undisturbed. It wasn’t the first time something that had appalled you had entirely unaffected him. You wondered if that was a result of his being a vampire, his living for over 800 years, his being from the Middle Ages, or if it was just how he was as a person.

Undoubtedly sensing your discomfort, Viago clarified, “A familiar serves a vampire for a while in exchange for being turned into a vampire after service.”

You calmed a bit. That sounded better than ‘slave.’ “So you’re going to turn her into a vampire?”

“No,” Deacon snorted.

“What? Why not?”

“Familiars don’t get turned into vampires.”

“Well, sometimes, probably, they do,” Viago argued. “I’ve never actually heard of it happening, though.”

“You’ve lost me,” you told them honestly.

Vladislav sighed. “Familiars exchange their service for the promise of becoming a vampire. Then they serve their masters until they die of old age or are killed.”

You exclaimed in disgust. “That’s horrible.”

Vladislav shrugged, his sleeve brushing your bare arm. These guys all ate actual, live people to survive. You supposed their moral compasses would have to be a bit more skewed than yours was.

However, despite your clear distaste for it all, you felt relieved to know they were vampires. It was one thing to kill because you could, or because you wanted to, as you thought had been the case before last night. It was another to kill because you had to. Yes, innocent people still died, and yes, your flatmates seemed to enjoy it. Deacon’s manic laughter as he chased that man out of your room was sure to haunt you for a while to come. But no matter how awful it was for the victims, or or how little guilt they felt about it, they had to do it to survive. And that fact alone made you feel better, if only a bit.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spiritual Spoiled Brats

Bible study time! Just try and follow along this morning if you can. Good luck with this one. I've been trying to render my observations out into this status out over the last several hours. Still unsure if I managed to articulate it properly. LOL

First starting with what I was reading here:

https://www.wildbranch.org/teachings/hebrew-greek-mind/lesson8.html

The above link is very good read, as is the entire series by Brad Scott. You can find the 13 part series at his Wildbranch Ministries website (wildbranch.org), under the heading "Teachings" and the subheading titled "Hebrew vs Greek Mind". It is a very deep dive study into how the origins of the words and meanings as they would have been originally spoken, versus how the Greek way of thinking has, over time, altered the meaning of language through an entirely different way of perceiving meanings of words. (Greek ≠ Abstract / Hebrew ≠Tangible). I would recommend it for anyone who might be interested in seeing how the Greeks/Romans of the time, were able to dominate Hebrew/Judaic culture, along with many, many other cultures in ancient times and conquer them in a way that was ultimately more effective than warfare; which was to change/alter their language, and change the meaning of words to fit their Greek mindset and worldview. The pen is truly mightier than the sword.

This got me thinking about the differences between modern day Christianity and how they generally view scripture, versus how those of us who have drifted away from that mindset view it, and how those differences shape our individual spiritual convictions.

In particular, this quote from the link above by Mr. Brad Scott, in my opinion, gives a good example of one of the differences:

"To the scripturally spiritual man the other world is the reward, not the goal."

So that makes me ask, "okay, is that a Biblical principle? What does he mean by "scripturally spiritual man"? Does the Bible say how we are rewarded and/or what our "goal" is? If so, then why/how would one be rewarded according to the scriptures? What is the difference between having a goal, and getting a reward? Are we all rewarded, and are there different rewards? What do Christians say our reward is (not individual Christians, more, those who are Christian leaders/denominations)?

After answering those questions for myself through searching the scriptures, it brought me first to this general observation. Just my opinion, not directed toward any particular person, denomination, etc...

Conservatives in this country in general roundly object to when children are given rewards without earning it (winning), just because they happened to be present; many consider children who get rewarded without being found worthy of reward as being spoiled. Yet at the same time, the prevalently accepted spiritual belief system in Christianity does exactly that. It claims that you only need to have "belief" of worthiness (ie: accepting Christ in your heart, aka, "grace through faith") in order to reap the rewards. And while, I agree, that those who perhaps have become martyrs and died as a result of professing that belief will certainly be rewarded for that devotion, that in itself is "action/works + faith": ie: "proof" of their belief. Works + Faith. Being slaughtered by someone because you would rather die than denounce your love for Yeshua (Jesus) would be the ultimate "work". However, at least as of now, the majority of Western Christians (not all, but many) have not had their devotion tested to the point of actual martyrdom, and even then, I suspect, many would still be found "lukewarm", based upon their unwillingness to sacrifice personal comforts in order to live according to the "how", the actual instructions that the Scriptures inform us that God himself commanded us to live. Ultimately, God knows our hearts, yes. But are you willing to take the chance that your own heart has been tempted astray by false teachings that might incur His wrath when judgement comes? I know I am not. And I refuse to entrust my own salvation to any pastor, preacher, teacher, organization, institution, religion, tradition, interpretation, culture, practice, or society which thinks it is free to add to or take away a single word of the Scriptures in order to accommodate and excuse their own personal preferences, philosophies, or traditions. God was pretty clear on what he thought of those who preferred traditions of men over the instructions he sat down for us.

Consider our "Participation Trophy" culture of entitlement. Christianity itself is a "Participation Trophy" Religion. "You don't have to "do" anything--- EVERYONE gets salvation!" Suddenly "Jesus" turns into "Oprah", handing out salvation to anyone who simply happens to be in the room at the time, cheering for their own selfish desire, without any other stipulations.

Is that what the Bible actually says though?

I find it ironic that on one hand, Conservatives roundly condemn Liberal thinking based on how all that matters is intention, while at the same time, using the same logic to explain how they are saved based strictly upon grace through faith alone, and entirely leaving out the fruit of the spirit and the works that the FRUIT produces.

But first, let's study out the word "FRUIT" so we can find out what the original intended meaning of what "Fruit" is according to how the ancient Hebrew authors of the Bible, and those who lived at the time it was written would have understood it to mean and what that applied to, so we can better understand how that would have been relevant then, and why I believe it is relevant even until now. The English word "fruit" in Hebrew is spelled "פרי", which is "pry" in modern Hebrew (transliterated), and pronounced "per-ee/pr-ee" in English. (Keep in mind, Hebrew is read from Right to Left, which can be confusing to English readers.) The origin of the modern Hebrew letters, " פרי " starting from the first symbol from right to left, if we break it down into their ancient pictographic Hebrew meanings would be: פ (pey) meaning "mouth", "word", or "speak", ר (resh) means "head of", "beginning of/heart of" and י (yod/yud) means "arm/hand", or "work". So fruit, means what you say and what you do, according to your head (heart).

John 14:15- "If you love me you will obey my commandments". What commandments? How do you obey them if you do not know what they are? Would you be considered obedient to Yah's commandments if you only confess things with words without actions that prove it? In conclusion, I realize this is going to be a very unpopular opinion, nonetheless, I will be totally blunt: Our modern day Judeo/Christian culture has turned us into spiritual spoiled brats.

I myself, have lived most of my life as a spoiled brat, and in many ways am still a spoiled brat. But that is in part, why I am so convicted to pursue righteousness.

Proverbs 21:21

"He who pursues righteousness and loving-commitment Finds life, righteousness and esteem."

Mattithyahu (Matthew) 16:24, 27

24 "Then יהושע said to His taught ones, “If anyone wishes to come after Me, let him deny himself, and take up his stake, and follow Me."

27 "For the Son of Aḏam is going to come in the esteem of His Father with His messengers, and then He shall reward each according to his works."

Shabbat Shalom, Ya'll!

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Congratulations MIA! You’ve been accepted as HYDRA.

Mia, let me just say WOW. Reading your app for Hydra left me speechless in the best way possible. The depth you gave to Nana was showed just how many layers there are to someone with the ability to control knowledge. “Nana is the Oracle of Delphi creating self-fulfilling prophecies that heroes try in vain to avoid, only to fall prey to them because of the knowledge Nana whispered in their ears.” I mean, do I need to say more after this sentence? I think I speak for all of us when I say we can’t wait to have them on the dash!

Welcome to Mutants Rising! Please read the checklist and submit your account within 24 hours.

NAME/ALIAS: Mia

PRONOUNS: she/her

AGE: 21

TIMEZONE & ACTIVITY LEVEL: PST. I’m currently finishing up my semester so will be busy for the next week, but I couldn’t resist applying. After the week is through I will be much more free since I will be on break, but once next semester starts, I’d put my activity at a 7. I am taking a full load of classes and will be likewise working, but have time in the mornings and evenings for replies

In Character Information:

DESIRED ROLE: Hydra

GENDER/PRONOUNS: genderfluid, they/them or she/her

DETAILS & ANALYSIS: Siddhartha Guatama was a prince, he lived in a palace with peacocks, and he had only been exposed to that which was beautiful and wholesome. That was the reality he lived in and the reality he believed in. One day he left and looked upon a dying woman, and with that one small piece of knowledge his entire reality was shattered. Neve used to have a family in Benjamin, then she glanced at a manila folder and learned more and thus her former reality was forever gone. In this way, reality is constructed, it is fabricated, and it is impermanent. Every person constructs their own reality, but these realities are fragile creations and sometimes the smallest piece of information can fundamentally reshape them. Nana is that piece of information, the one which changes everything. They are not god, they do not create truth (if there even is such a thing), rather, they create cages and distractions that people trap themselves in. Nana is the Oracle of Delphi creating self-fulfilling prophecies that heroes try in vain to avoid, only to fall prey to them because of the knowledge Nana whispered in their ears. Nana is not immune to their own words though. While their mutation may not be involved, their preconceived notions trap them in their own constructed reality.

Nana understands the fragility of an individual’s sense of reality, the strings that are woven together to create it, and the threads that need to be pulled to unwind it. To them, knowledge is not stagnant, it is a forever moving a shifting field which they to some extent can control. There is no such thing as a fact on a page, merely one person’s opinion that may be changed if new or different information is presented.

Beyond their ability, to me, Nana used to be a creature of ambition who had nothing to lose, but this has started to change. They joined the King’s Collective out a combination of desire and necessity, and was willing to risk almost anything to make themselves non-disposable. Winning and competition was already ingrained in them, and their insecurities belayed into confidence and pride the longer they moved away from their parents. This drive pushed them into the high ranks of the King’s Collective. While in many ways they are still this creature, Neve is the pieces of information slowly changing Nana’s worldview. They have a family in Neve, they have a something still unspeakable in Ilie, and they have position. Once upon a time the idea of having a true family and other close bonds was beyond the realm of conception, but now it is within grasp and Nana will be hard pressed to give it up even if it means sacrificing things they would have previously deemed more important.

BIO: (TW: Emotional Abuse)

Nana grew up in an apartment full of ghosts. The items left scattered around the three rooms that made up their home indicated other people lived with Nana––a tube of wine red lipstick standing at attention near the bathroom sink, a pair of tattered shoes far too large for a small child like them––but there were no warm bodies willing to be hugged. Nana wasn’t an orphan, Nana had seen two adults walking in and out of the small apartment, but at the same time the two people who lived with them were hardly their parents. The woman had birthed them, the man would bring food for them, but neither was a parent. Rather, the two of them were systems of measurement through which Nana could understand their progress in life. They were echoes of fully realized people who critiqued and criticized.

The ghosts in Nana’s home were not simply restless spirts looking for a little amusement before moving on to the beyond, but instead were vengeful, erratic, and loud specters that would howl and shriek one night and be silent for weeks as if to say you are not even worth haunting. Then the two would materialize again and speak to Nana briefly, letting them know what they thought of Nana’s progress, before fading back into spirits which Nana could only faintly make out when looking closely. The ghosts didn’t need to touch Nana for them to feel the ghost’s hands around their neck and in their head, tugging at their hair all while whispering demands for perfection in their ear.

In its own twisted way this relationship dynamic somehow made sense to Nana because in the same way those two adults were not parents, Nana was not a child. Nana was a legacy. By this logic it made sense that Nana was not treated like their classmates––as something precious to be coddled and cared for––because their classmates were just kids. While Nana reasoned that legacies and children were not so dissimilar, as both had to be nurtured and cultivated, the way success was measured was vastly different. A legacy must succeed at all things to be considered a worthwhile endeavor: they must be always be the best, they must never be frightened by trivial things, and affection was granted only as a fleeting reward. On the other hand, children had high and low-points, they were hugged when they were scared, and they were loved unconditionally. Children were allowed to fail, but legacies were not. Children were raised to be cherished; Nana was raised to be admired.

Admired they were. Much like a swan swimming, all people saw was the graceful glide of a beautiful child who exceed in all they tried. They seldom saw the work, the agony, that Nana put themself through to present such an image of ease, of simple elegance. Success was met with fleeting affection by their parents––a small smile or a light shoulder pat––but it would leave Nana glowing for days. Failure would leave them verbally thrashed, followed by long periods of silence where their parents completely ignored them, isolating them. During these enforced interludes of solitude, Nana would pour over texts, comparing different accounts of the same battle to see the discrepancies between them all while laughing as both claimed to be the sole authority on what happened. Likewise, their mother’s old Buddhist texts brought over when she moved from Japan became a source of fascination. They sparked ideas of fabrication, impermanence, and constructed realities.

Nana has never been a flashy person, rather one who projected smooth dignity and grace, and it was not surprising that their ability would mirror this. There were no sparks, no loud claps of thunder, no tremors echoing through the earth when they discovered it. No, there was just a tone of conviction carried on steady words leaving no room for doubt. I was in class today, how could you forget? These were not words of honey; they were words of steel. They did not seduce or charm, they described and informed. The teacher nodded, fully convinced. Nana smiled politely and excused themselves, a new trick added to a rapidly expanding repertoire.

During the evenings they would leave the house, sneaking out of the window with the assurance their parents never checked on them in the night. They went into the streets, seeking out the type of knowledge that only the cover of night provides access to. It was on such a night they first observed the King’s Collective. Almost immediately they were entranced by the group of individuals that to them looked like freedom. No walls that entrapped or silence which suffocated. It took little time before they approached the group, meek only in comparison to who they are now. They joined shortly afterwards.

With a taste of life away from their household, things rapidly deteriorated within the family. The King’s Collective made Nana daring and defiant. Their accomplishments grew beyond just being something for their parents, but rather a creature of their own making. With this change resentment started to burn bright in their ribs, heart hardening in anger rather than fear at their mother and father’s harsh words. For once when screamed words echoed like a bell inside their head, they screamed back, escalating the situation into previously unexplored heights. Like knives the words were snarled out, poison lacing each one: I was never your daughter, you don’t even know me. They were meant symbolically, to illustrate a point, but they became oh so literal when their mother looked at them and asked who Nana was.

In that moment, it amazed Nana how much a person can both love and hate someone. How long had they longed to be free of their parents and yet, now that they effectively were, it felt like they couldn’t breathe. They were about the take it back, to reinsert the information they stole back into their parents’ heads, but Nana couldn’t. They didn’t know what they had erased, they didn’t know how their parents had looked at them, all they would be able to create was a upside down projection of a past that they might have imagined up. Some information was too unique and too individual to ever truly know. In a moment they had taken everything and created nothing out of it with no form of recourse.

The King’s Collective became a home of sorts, a shambled together support system if nothing else. It helped Nana go to University of Chicago and study law. This was not out of pure altruism, but rather it increased her use within the King’s Collective. For them, knowledge was power and thus the more they could acquire the more use they could be. They were a tool to be used: first as a symbol of success for their family, and now as a weapon in the King’s Collective. Once they would have been angry about this, now though, they were resigned. Love and care had always been transactional and the only way to receive it was to make yourself worth receiving it. This was Nana’s reality. With this mindset they crafted themself into the perfect weapon, eyes alert and undistracted.

EXPANDED CONNECTIONS:

Neve Kaplan: Neve is the original wrench in Nana’s plans. While Nana is fully disillusioned with the idea of unconditional love, Neve provides it in the form of a familial bond, something they have never truly had. This is likely beginning to alter Nana’s rather cynical world view, but habit is a difficult thing to unlearn. Nana’s sister is, in many ways, the thing they hope to protect the most in the world. Perhaps it makes them weak and perhaps their normally impeccable logic becomes flawed, but they do not care. Learning of Benjamin’s history with Neve was only distressing to Nana because of the obvious pain and hurt it brought Neve. For a second, Nana almost wanted to take it away; they wanted to strike Neve’s newfound knowledge from her mind and let things continue as they were, but love had made them weak. Nana loved too hard and too much to be selfish in this moment. They listened to Neve’s plans, heart palpitating with each word. Her plans would destroy the fragile life that Nana had built for themself, and yet they could not bring themself to do anything about it. Instead they took a step back, refusing to directly involve themselves for the moment in favor of playing the large shadow looming behind Neve, ready to strike vengeance upon those who would dare hurt her.

They would destroy Benjamin if need be to protect their sister––the consequences be damned. That type of passion is born of love, something Nana has received a desperately small amount of in their life, and it terrifies them. At the same time though, they refuse to let it go, choosing instead to be willing to sacrifice what they once thought so important in favor of their sister.

Ilie Lacey: Ilie was a subconscious indulgence that desperately burned them if they thought about it too much. Ilie was a mistake, of this there was no doubt, but Ilie was a mistake that Nana may make again and again just to feel something for somebody else. Ilie invades their mind regularly, slipping through the cracks of carefully constructed walls Nana prided themselves on. It wasn’t love, it couldn’t be, but that hope of maybe it could be one day was enough to both make Nana want to never speak of it again and to desperately want a repeat performance. Never one to be weak to whims, they could tend towards the former opinion, carefully moving forward as if nothing had happened.

Abigail Imani: The two had a contentious relationship since their first meeting. Nana was already young, desperate to prove themselves in any way, and had a competitive streak a mile wide. This made them incredibly prickly towards anything that could be perceived as competition and Abigail was competition. Part of them felt a thrill at the challenge, there were few people who could go toe-to-toe with Nana, but another part felt threatened. It was rare somebody could challenge Nana, and for somebody trying to assert themself for the first time it was difficult to face. Now that Nana had effectively won, this need to champion has settled somewhat, but Abigail has a way of reminding Nana of youthful insecurities better left in the past.

ANYTHING ELSE: Nothing

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

David Simmons

David Simmons is a professor of Film Studies and Humanities at Northwest Florida State College (NWFSC) in Niceville, FL. That’s a very small town about half-way between Pensacola & Tallahassee in the Florida panhandle which is “the reddest of the red part of Florida.”

He attended BYU for both his Bachelor’s and Master’s degree, and taught at the Missionary Training Center during that time. While at BYU he performed in several operas and plays, and was in Concert Choir and BYU Singers. He earned his Ph.D. from Florida State University.

He makes a big impact in his north Florida community. He organized an on-campus Film Club, and a Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA). As faculty advisor to the GSA, he’s helped them organize the area’s first LGBTQ Masquerade ball, which was open to the public. He also organized the city of Niceville’s very first Pride Walk.

He attends his local ward where he’s the choir director. “It’s difficult being gay and being a member of the church. It shouldn’t have to be. The Gospel is for everyone. But sadly, some members don’t think that.” He describes his ward as “a very conservative, military ward” (there’s an air force base nearby).

Can you imagine being a queer kid in this conservative little town of 12,000 and all of a sudden, there’s someone openly gay who is making safe spaces and raising the profile of the queer community?

This past week he was invited by his bishop to speak on ministering to LGBTQ members during a joint 3rd-hour meeting (5th Sunday). He says “There was a lot of pushback after I finished the talk, but that’s OK. I want to help church to be more loving for those who come after me.”

—————————————————————

“By This Shall All Men Know Ye Are My Disciples” Dr. David C. Simmons Sep. 30, 2018

On the last night of his mortal life, Jesus invited Judas to leave so that He could give a special message to his remaining 11 apostles (John 13:27-31). In Jesus’ Final Sermon, He gave them a sign, a way to tell who are Jesus’ true followers and who are not: “By this shall all men know that ye are my disciples, if ye have love one to another” (John 13:35).

In other words, Jesus knew there would be some who would claim to be His followers, but are not. We can recognize them, both in and out of the Church, because instead of loving those who are different than they are, they put them down in a self-righteous way.

Jesus went to the outsiders of his local community: the sinners, the poor, the lame, the blind, the lepers. He was teaching His true followers, in both word and deed, how to develop the capacity to love like He does.

In our day, some of the ones who have been treated the harshest by Christian churches are members of the LGBTQ community. A few supposed-Christians use passages of scripture, or proclamations, or words from bygone leaders as weapons to harm the very natures of these children of God.

I work with LGBTQ students at the College. I’ve listened to their stories. I’ve heard time and time again how they have been rejected by their families, their churches, and their communities, just for being who they are.(1)

Many of their “Christian” parents, thinking they were “doing God service” (John 16:2), threw them out of their homes and families. Now these teenagers are homeless. LGBTQ youth are 120% more likely to experience homelessness than their peers.(2)

LGBTQ youth are also 5 times more likely to commit suicide than their peers.(3) Nearly half of all LGBTQ youth have attempted suicide more than once.(4) And rates are even worse among LGBTQ youth who are members of the Church. Teen suicide rates in Utah have doubled since 2011, while the rest of the country did not see an increase.(5)

Why is this?

I want you to imagine that you were born as a member of the LGBTQ community. You grew up in Primary singing, “I Am a Child of God.” But then, at some point you were told by those who are closest to you, by those whom you love and trust to tell you the truth, that God doesn’t love you—that He has no place for you in the plan of salvation.

What are your options at that point? It seems that none of them are very good:

1) You can remain in the Church and live a lonely, pain-filled existence.(6) While everyone around you is boasting about the joy of marriage and being part of a family, you are constantly reminded that that is not for you.

2) You can leave the Church and find love and a family. But then you are left without the great spiritual helps the Gospel of Jesus Christ can offer.

3) You can marry someone of the opposite sex and may not be fulfilled. The Church does not encourage this anymore(7) because divorce rates in mixed-orientation marriages are far higher—80%(8)—and then often involve children.(9)

Can you feel that none of these options are fulfilling? Perhaps this is why so many LGBTQ members of the Church lose all hope and purpose and then may choose to end their lives.(10)

The Church is concerned about this. Just last month, on August 9, 2018, ward councils all over the world received a document called “Preventing Suicide and Responding after a Loss.” It begins with: “Members of the Church everywhere are invited to take an active role within their communities to minister to those who have thoughts of suicide or who are grieving a loss.”(11)

The Church is changing considerably how it ministers with love to its LGBTQ members.(12)

When Dan Reynolds, the lead singer of Imagine Dragons, organized an Aug. 2017 concert in Provo called LoveLoud, to let LGBTQ members know they are loved,(13) the Church put out an official statement endorsing that event: “We applaud the LoveLoud Festival for LGBT youth’s aim to bring people together to address teen safety and to express respect and love for all of God’s children. We join our voice with all who come together to foster a community of inclusion in which no one is mistreated because of who they are or what they believe. We share common beliefs, among them the pricelessness of our youth and the value of families. We earnestly hope this festival and other related efforts can build respectful communication, better understanding and civility as we all learn from each other.”(14)

Just two weeks ago, on Sep. 17, 2018, the Church called Elizabeth Jane Darger, a longtime LGBTQ advocate,(15) to be on the General Young Women’s Board.(16) What a powerful voice to have advocating for LGBTQ youth in the Young Women’s program!

The Church also has an official website, Mormon and Gay (mormonandgay.lds.org). It features the stories of many LGBTQ members, which are helpful for putting yourself in their shoes, so you can grow in understanding.(17)

This Church website also teaches several important principles:

1) “God loves all of us. He loves those of different faiths and those without any faith. He loves those who suffer. He loves the rich and poor alike. He loves people of every race and culture, the married or single, and those who. . . identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual. And God expects us to follow his example.”(18)

2) “No true follower of Christ is justified in withholding love because you decide to identify [as a member of the LGBTQ community].”(19)

3) “God’s plan is perfect, even if our current understanding of His plan is not.”(20)

We don’t see the whole picture right now. As Paul taught: “For we know in part, and we prophesy in part” (1 Corinthians 13:9-13). Since we only “see through a glass, darkly” in relation to many eternal things, instead of pretending that we fully understand God’s will in all ways, shouldn’t we act on what He has called us to do: love? That was the Savior’s prime commission to His followers. Indeed, it’s how they would be identified by others as His true disciples.

The problem may lie in our understanding of our LGBTQ brothers and sisters. Some members may look at them as having a physical impairment that needs fixing. Both Elder Holland, in General Conference,(21) and the Church’s official website explain that this is not true(22). LGBTQ members are not choosing a “lifestyle”; it is how they are.

If we could learn to see our LGBTQ brothers and sisters like the Savior sees them, it would change our entire worldview and behavior. We would never make jokes about the LGBTQ community in our daily interactions. We would never express disgust at someone whose gender or sexuality was different than ours. We would never teach a child to turn off the TV when an LGBTQ person talks about their life.(23) Such actions not only contain unknowing bias and privilege, but are also doing untold harm to the lived lives of our brothers and sisters.

Statistically, at least 5% of the population is a member of the LGBTQ community,(24) with some recent surveys having this percentage far higher.(25) Even if we take the lower figure, that means that in a ward of 500 people, there may be at least 25 LGBTQ members. That so many of them are now less active is telling.

You and I both know multiple members, including young men and young women, who have passed through our ward, and been told they were “others,” or “less than,” or “outsiders” because of their gender or their sexuality. They sat through well-meaning but uninformed talks and lessons where a statement or teaching was weaponized against them. They were made to feel as though there was no place for them in the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Today, many of them have left the embracing arms of the Savior, His atonement, and His restored gospel. What a breathtaking, unbelievable loss for us, for them, and for God.

We still love them. But wouldn’t it better if they had these things to bless their lives too? Aren’t they better off inside the Church, rather than being forced away because of the unkind words and deeds of those who should be followers of Jesus Christ? Isn’t that what true ministering is all about? Reaching out with love to people no matter where they are on their spiritual journey?

Last month, speaking in a BYU Devotional, Eric D. Huntsman, a Professor of Ancient Scripture, explained our need to minister with love to our LGBTQ brothers and sisters: “We should never fear that we are compromising when we make the choice to love. . . . Accepting others. . .means simply that we allow the realities of their lives to be different than our own. Whether those realities mean that they look, act, feel, or experience life differently than we do, the unchanging fact is that they are children of loving heavenly parents, and the same Jesus suffered and died for them, as for us. Not just for LGBTQ+ sisters and brothers but for many people, the choice to love can literally make the difference between life and death.”(26)

Undoubtedly, there are those in this room who will have children, other family members, or friends who will come out to you. It will be one of the most painfully vulnerable moments of their life. Decide right now, that you will respond immediately with overwhelming love and kindness. That’s all you have to do. Just put your arms around them and say, “Thank you for telling me. I love you just like you are.”

Think to yourself, “How would the Savior reach out with love?” Then love like that. It may take having to unlearn some of the things your local culture has taught you in order to walk the higher way of the Law of the Gospel (loving like Jesus loved).

Seek out LGBTQ people in your circles of influence. Get to know them and their stories. Instead of correcting and instructing, just listen, feel, and love them for who they are. Become a powerful friend and ally.

If you don’t have the strength to do this yet, cry out to your God for strength, for courage, and for the ability to develop the capacity to love as He loves.

If you are a member of the LGBTQ community, try this experiment. Go home tonight and pray in secret: “Dear Heavenly Father, do you love me?” Feel God’s immense peace and love wash over you as He confirms this with certainty. You are His child and He loves you. The Gospel is for you too.

Conclusion The Holy Ghost bears record to our souls that God loves all of his children, not just his straight children. He loves his gay children, his lesbian children, his bi children, his trans children, and those who are still trying to understand the divine way he made them. The atonement of Jesus Christ is for everyone.

Nephi taught this sublime, eternal truth: “[The Savior] inviteth all to come unto him and partake of his goodness.” What does “all” mean? It means “all.”

“And he denieth none that come unto him.” What does “none” mean? It’s means “none.”

“Black and white, bond and free, male and female; and he remembereth the heathen [that means non-member]; and all are alike unto God” (2 Nephi 26:33, emphasis added).

It’s my testimony that the Savior’s atonement is for everyone. He wants us to establish Zion right here and right now. But that can only be done by partaking of the atonement, and allowing our natures to be changed so that we are filled with love for everyone, especially those whom our local culture deems as “outsiders.” Then we can’t wait to go forth, becoming the Savior’s hands to lift, to minister, and to love others.

In the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

[If you need someone to talk with about the ideas presented here, please email me (David Simmons): [email protected]]

Appendix 1: Scriptures, Quotes, and Resources for Further Study

“Mormon LGBT Questions.” Bryce Cook, March 17, 2017. This is the most profound resource on how the Church’s view on LGBTQ members has changed over time. I think every member of the Church should read it. If it’s too long, read a summary here:

“LGBT Questions: An Essay.” By Common Consent, March 19, 2017. This is a summary of Bryce Cook’s landmark “Mormon LGBT Questions” document.

Mormon and Gay. This is the Church’s official website. They recently changed the name from mormonsandgays to mormonandgay to acknowledge the many members who are both.

“Hard Sayings and Safe Spaces: Making Room for Struggle as Well as Faith.” Eric D. Huntsman. Aug. 7, 2018, BYU Speeches. A masterful talk given last month at a BYU Devotional about our need to love each other wherever we are on our spiritual journey.

“A Mission President’s Beautiful Response When a Missionary Came Out to Him as Gay.” LDS Living, Aug. 27, 2018. Cal Burke’s inspiring story about coming out to his mission president and being received with love.

“Mormon and/or Gay?” By Common Consent, Aug. 20, 2018. How we often unknowingly use “othering” language in our discourse about our LGBTQ brothers and sisters.

“To Mourn with Gay Friends That Mourn.” By Common Consent, Oct. 4, 2017. Why we often correct and instruct rather than listen and feel when we talk with our LGBTQ brothers and sisters.

“An Open Letter to Latter-Day Saints: When a Gay Person Shows Up at Church.” By Common Consent, Nov. 8, 2015. A discussion of the unbearable choice given to LGBTQ members.

That We May Be One: A Gay Mormon’s Perspective on Faith and Family. Tom Christofferson. SLC: Deseret Book: Sep. 2017. An apostle’s gay brother tells his experience of being unconditionally loved and supported by his family and bishopric after coming out to them. You can purchase it here.

President M. Russell Ballard • “I want anyone who is a member of the Church who is gay or lesbian to know I believe you have a place in the kingdom and I recognize that sometimes it may be difficult for you to see where you fit in the Lord’s Church, but you do. We need to listen to and understand what our LGBT brothers and sisters are feeling and experiencing. Certainly, we must do better than we have done in the past so that all members feel they have a spiritual home.”(27)

Elder Quentin L. Cook • “As a church, nobody should be more loving and compassionate. Let us be at the forefront in terms of expressing love, compassion, and outreach. Let’s not have families exclude or be disrespectful of those who choose a different lifestyle as a result of their feelings about their own gender.”(28)

Matthew 9: Loving Outsiders is More Important than Church Ritual • Matthew 9:10-11 “And it came to pass, as Jesus sat at meat in the house, behold, many publicans and sinners came and sat down with him and his disciples. And when the Pharisees saw it, they said unto his disciples, Why eateth your Master with publicans and sinners?” Here, church leaders and members are rebuking Jesus for being with tax collectors (a hated segment of society, that were often excommunicated from the synagogues) and sinners • Matthew 9:12-13 “But when Jesus heard that, he said unto them, They that be whole need not a physician, but they that are sick. But go ye and learn what that meaneth, I will have mercy [Greek: eleos, “love” or “compassion”] and not sacrifice.” Jesus is here quoting Hosea 6:6, where He once told the prophet: “I want you to show love, not offer sacrifices” (N.L.T. Hosea 6:6). In other words, showing love to the outcasts of society is more important than church rituals. It’s more important than partaking of the sacrament. It’s more important than going to the temple. If you don’t love others (especially the outsiders, like Jesus did) than none of the rituals • N.L.T. Matthew 9:13 “For I have come to call not those who think they are righteous, but those who know they are sinners.” Jesus is very clear with these church leaders and members who think they are following all the rules, but yet are looking on the outcasts of society, that they are in a far worse position than those they look down on. They are the greater sinners.

Humble Outsiders Will Go Into the Kingdom of God before SelfRighteous Members • Matthew 21:31 During His mortal ministry, the Savior had some of his harshest words to say to members of the Church who were afflicted by self-righteous-itis. They thought they were better than females, or the poor, or those outside certain family lines. To them, He said: “The publicans and harlots go into the kingdom of God before you.” • Matthew 22:1-14 Jesus also told the parable of the marriage of the king’s son, where those who were bidden to the marriage dinner “would not come,” so the king tells his servants to go out to the highways and gather as many of those the world deemed as outsiders, to come partake of the feast. He said to do this because “many are called [baptized members of the Church], but few are chosen [to live the way the Savior lives].” • The Savior Himself went to the poor, the lame, the leprous, the blind, to those whom society deemed outsiders. If we want to be like Him, we shouldn’t align ourselves with the self-righteous in our day and put down the vulnerable and the outsiders. We should instead follow His example and seek out those who may have been labeled “outsiders.”

The Outsiders Will Go Into Heaven Before Complacent Members • Luke 14:15 “And when one of them that sat at meat with him heard these things, he said unto him, Blessed is he that shall eat bread in the kingdom of God.” Since this teaching may not be absolutely clear, Jesus gives a parable to explain it—the Parable of the Great Supper. • Luke 14:16-17 “Then said he unto him, A certain man made a great supper, and bade many: and sent his servant at supper time to say to them that were bidden, Come; for all things are now ready.” What’s the supper? Feasting on the Gospel of Jesus Christ. This is such a beautiful image. When we take it inside of us, it becomes part of who we are (Schaelling, C.E.S. Institute Lecture, “Great Supper”). • How do we accept the invitation to the Supper? Through baptism (Schaelling, C.E.S. Institute Lecture, “Great Supper”). • Luke 14:18-20 “And they all with one consent began to make excuse. The first said unto him, I have bought a piece of ground, and I must needs go and see it: I pray thee have me excused. And another said, I have bought five yoke of oxen, and I go to prove them: I pray thee, have me excused. And another said, I have married a wife, and therefore I cannot come.” What excuses do people make not to come to the feast? New ground, new oxen, new wife. There are many reasons that people can give for not putting the Gospel of Jesus Christ first in their lives. Do we ever put possessions, or even family members, before the Savior? What does Jesus say about this in verse 26? “If any man come to me and [Greek “doesn’t love less”] his father, and mother, and wife, and children, and brethren, and sisters, yea, and his own life also; or in other words, is afraid to lay down his life for my sake; he cannot be my disciple” (J.S.T. Luke 14:26). This is tough. What do you do if your wife wants you to stay home instead of doing your home teaching? What do you do if your parents tell you they will disown you if you get baptized into the restored Gospel of Jesus Christ? When I was on my mission in Texas, there was an 18-year-old non-member girl named Letti who went to seminary with some of her friends, felt the Spirit of God tell her it was true, and knew she needed to join. But her parents told her that if she did, she would no longer be considered one of their family. What a tough choice for anyone to have to make. Yet, she went through with her decision to be baptized anyway, for she could not put other things—even family—before the Savior. Letti was being a true disciple of Jesus Christ. She put him first above all things, even her own family • Luke 14:21-24 “So that servant came, and shewed his lord these things. Then the master of the house being angry said to his servant, Go out quickly into the streets and lanes of the city and bring in hither the poor, and the maimed, and the halt, and the blind. And the servant said, Lord it is done as thou hast commanded, and yet there is room. And the lord said unto the servant, Go out into the highways and hedges, and compel them to come in, that my house may be filled. For I say unto you, That none of those men which were bidden shall taste of my supper.” What does this mean? • 1) Since the Jews, the Lord’s covenant people, were rejecting the supper, that great feast of the Gospel was just about to go to the spiritually poor, maimed, halt, and blind: in other words, the Gentiles, beginning at the time of Paul (Schaelling, C.E.S. Institute Lecture, “Great Supper”). • 2) For me, individually, it means I need to come and partake of the Savior, and his Gospel, and have this mighty value change in my life where I realize that earthly things are only here to be turned into eternal things by using them to help other people, so that my place at the eternal feast doesn’t go to someone else who is more giving, more loving, and more compassionate than I am. I need tobe like the Savior.

Matthew 19:30 The First Shall Be Last and the Last Shall Be First • Jesus said: “But many that are first shall be last; and the last shall be first.” • As Dr. Fatimah Sellah recently said: “I’ve long believed of the marginalized of this church and the world, that if the first shall be last and the last shall be first: I’d be careful if I were first right now. I’d be careful if I were the ones at the pulpits and held the power. God is a God of disruption and flips things on its head.”(29)

Ephesians 2:19 There Are No Outsiders in God’s Church • “Now therefore ye are no more strangers and foreigners, but fellowcitizens with the saints, and of the household of God.”

President Brigham Young • “The least, the most inferior person now upon the earth . . . is worth worlds” (Journal of Discourses 9:124).

President Dieter F. Uchtdorf • “Sometimes we confuse differences in personality with sin. We can even make the mistake of thinking that because someone is different from us, it must mean they are not pleasing to God. This line of thinking leads some to believe that the Church wants to create every member from a single mold—that each one should look, feel, think, and behave like every other. This would contradict the genius of God, who created every man different from his brother, every son different from his father. . . . As disciples of Jesus Christ, we are united in our testimony of the restored gospel and our commitment to keep God’s commandments. But we are diverse in our cultural, social, and political preferences. The Church thrives when we take advantage of this diversity and encourage each other to develop and use our talents to lift and strengthen our fellow disciples” (“Four Titles.” Ensign. May 2013).

Bishop Gerald Causse, First Counselor in the Presiding Bishopric • “During His earthly ministry, Jesus was an example of one who went far beyond the simple obligation of hospitality and tolerance. Those who were excluded from society, those who were rejected and considered to be impure by the self-righteous, were given His compassion and respect. They received an equal part of His teachings and ministry. • “For example, the Savior went against the established customs of His time to address the woman of Samaria, asking her for some water. He sat down to eat with publicans and tax collectors. He didn’t hesitate to approach the leper, to touch him and heal him. Admiring the faith of the Roman centurion, He said to the crowd, “Verily I say unto you, I have not found so great faith, no, not in Israel” (Matthew 8:10; see also 8:2-3; Mark 1:40-42; 2:15; John 4:7-9). • “In this Church there are no strangers and no outcasts. There are only brothers and sisters. The knowledge that we have of an Eternal Father helps us be more sensitive to the brotherhood and sisterhood that should exist among all men and women upon the earth. • “A passage from the novel Les Misérables illustrates how priesthood holders can treat those individuals viewed as strangers. Jean Valjean had just been released as a prisoner. Exhausted by a long voyage and dying of hunger and thirst, he arrives in a small town seeking a place to find food and shelter for the night. When the news of his arrival spreads, one by one all the inhabitants close their doors to him. Not the hotel, not the inn, not even the prison would invite him in. He is rejected, driven away, banished. Finally, with no strength left, he collapses at the front door of the town’s bishop. The good clergyman is entirely aware of Valjean’s background, but he invites the vagabond into his home with these compassionate words: “‘This is not my house; it is the house of Jesus Christ. This door does not demand of him who enters whether he has a name, but whether he has a grief. You suffer, you are hungry and thirsty; you are welcome. … What need have I to know your name? Besides, before you told me [your name], you had one which I knew.’ “[Valjean] opened his eyes in astonishment. “‘Really? You knew what I was called?’ “‘Yes,’ replied the Bishop, ‘you are called my brother.’” (Les Miserables 1:73). • “In this Church our wards and our quorums do not belong to us. They belong to Jesus Christ. Whoever enters our meetinghouses should feel at home. • “It is very likely that the next person converted to the gospel in your ward will be someone who does not come from your usual circle of friends and acquaintances. You may note this by his or her appearance, language, manner of dress, or color of skin. This person may have grown up in another religion, with a different background or a different lifestyle. • “We all need to work together to build spiritual unity within our wards and branches. An example of perfect unity existed among the people of God after Christ visited the Americas. The record observes that there were no “Lamanites, nor any manner of -ites; but they were in one, the children of Christ, and heirs to the kingdom of God.” (4 Nephi 1:17). • “Unity is not achieved by ignoring and isolating members who seem to be different or weaker and only associating with people who are like us. On the contrary, unity is gained by welcoming and serving those who are new and who have particular needs. These members are a blessing for the Church and provide us with opportunities to serve our neighbors and thus purify our own hearts. • “Reach out to anyone who appears at the doors of your Church buildings. Welcome them with gratitude and without prejudice. If people you do not know walk into one of your meetings, greet them warmly and invite them to sit with you. Please make the first move to help them feel welcome and loved, rather than waiting for them to come to you. • “After your initial welcome, consider ways you can continue to minister to them. I once heard of a ward where, after the baptism of two deaf sisters, two marvelous Relief Society sisters decided to learn sign language so they could better communicate with these new converts. What a wonderful example of love for fellow brothers and sisters in the gospel! • “I bear witness that no one is a stranger to our Heavenly Father. There is no one whose soul is not precious to Him. • “I pray that when the Lord gathers His sheep at the last day, He may say to each one of us, “I was a stranger, and ye took me in.” Then we will say to Him, “When saw we thee a stranger, and took thee in?” And He will answer us, “Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me” (Matthew 25:35-40). In the name of Jesus Christ, amen” (“Ye Are No More Strangers,” General Conference, October 2013).

ENDNOTES ——————————

(1) McKeon, Jennie. “NWFSC Students Hosting Inaugural Gay Ball.” WUWF. Sep. 20, 2018. http://www.wuwf.org/post/nwfsc-students-hostinginaugural-gay-ball

(2) Silva, Christina. “LGBT Youth are 120% More Likely to Be Homeless Than Straight People, Study Shows.” Newsweek. Nov. 30, 2017. https://www.newsweek.com/lgbt-youth-homeless-study-727595

(3) “Facts About Suicide.” The Trevor Project. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/resources/preventing-suicide/factsabout-suicide/#sm.001r5tfiv1doccqtqy6168cjea5zn

(4) http://www.speakforthem.org/facts.html

(5) Utah Department of Health, https://ibis.health.utah.gov/pdf/opha/publication/hsu/SE04_SuicideE piAid.pdf See also: Hatch, Heidi. “Is Utah’s Youth Suicide Rate Linked to Utah’s Culture Surrounding LGBT?” https://kutv.com/news/local/isutahs-youth-suicide-rate-linked-to-utahs-culture-surrounding-lgbt See also the Church’s official page on LGBTQ suicide: https://mormonandgay.lds.org/articles/depression-andsuicide?lang=eng

(6) “My Life at BYU-I as a Gay Mormon.” https://zelphontheshelf.com/mylife-at-byu-i-as-a-gay-mormon/

(7) “President Hinckley. . .made this statement: ‘Marriage should not be viewed as a therapeutic step to solve problems such as homosexual inclinations or practices.’” https://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/interview-oaks-wickmansame-gender-attraction

(8) Kort, Joe. “Mixed-Orientation Marriages.” GLBTQ. 2015. http://www.glbtqarchive.com/ssh/mixed_orientation_marriages_S.pdf

(9) Carol Kuruvilla, “Gay Mormon Who Became Famous for Mixed Orientation Marriage Is Divorcing His Wife.” Huffington Post. Jan. 29, 2018. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/gay-mormon-josh-weeddivorce_us_5a6f331be4b06e253269d34a

(10) Lang, Nico. “‘I See My Son In Every One of Them’: With a Spike in Suicides, Parents of Utah’s Queer Youth Fear the Worst.” Vox. March 20, 2017. https://www.vox.com/identities/2017/3/20/14938950/mormonutah-lgbtq-youth

(11) This document outlines the warning signs for suicide: • Looking for a way to kill themselves • Talking about feeling hopeless or having no reason to live • Talking about feeling trapped or in unbearable pain • Talking about being a burden to others • Acting anxious or agitated or behaving recklessly • Withdrawing or isolating themselves • Showing rage or talking about seeking revenge • Displaying extreme mood swings When you many of these there are three things to remember: Ask, Care, Tell.

1) Ask. Ask the person directly if they are thinking about suicide. If they say yes, ask: “Do you have a plan to hurt yourself.” If the answer is yes, call a crisis helpline. (The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255.) If the answer is no, move to step 2: 2) Care. Show that you care by listening to what they say. Give them time to explain how they are feeling. Respect their feelings by saying something like: “I’m sorry you are in so much pain. I didn’t realize how hard things are for you right now.” You might offer to help them make a Suicide-Prevention Safety Plan that helps people identify their personal strengths, positive relationships and healthy coping skills. 3) Tell. Encourage the person to tell someone who can offer more support. If they will not seek help, you may need to tell someone for them. You may want to say something like: “I care about you and want you to be safe. I’m going to tell someone who can offer you the help you need.” Respect them by letting them pick the resource, such as a someone on the free crisis helpline.

(12) For the best, most-thorough examination of the how the Church’s position regarding LGBTQ members has changed since the days of President Kimball, see: Cook, Bryce. “Mormon LGBT Questions.” March 17, 2017. I think every member of the Church should read this. https://mormonlgbtquestions.com/2017/03/17/what-do-we-know-ofgods-will-for-his-lgbt-children-an-examination-of-the-lds-churchsposition-on-homosexuality/

(13) A documentary called Believer (2018) tells the fascinating, dramatic story of the lead-up to this concert: https://www.hbo.com/content/hboweb/en/documentaries/believer/a bout.html Here’s how you can watch it: https://heavy.com/entertainment/2018/06/watch-believerdocumentary-online/

(14) Official Church Statement, August 16, 2017, https://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/church-statement-loveloud-festival

(15) Cynthia L. “New YW and RS Boards Include Two Black Women, ‘Common Ground’ LGBT Inclusion Advocate.” Sep. 18, 2018. https://bycommonconsent.com/2018/09/18/new-yw-and-rs-boardsinclude-two-black-women-common-ground-lgbt-inclusionadvocate/#more-106875

(16) https://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/new-latter-day-saintgeneral-board-members-named

(17) https://mormonandgay.lds.org/stories?lang=eng

(18) https://mormonandgay.lds.org/articles/church-teachings?lang=eng

(19) https://mormonandgay.lds.org/articles/who-am-i?lang=eng

(20) https://mormonandgay.lds.org/articles/gods-plan?lang=eng

(21) “I must say, this son’s sexual orientation did not somehow miraculously change—no one assumed it would.” Holland, Jeffrey R. “Behold Thy Mother.” Oct. 2015 General Conference. https://www.lds.org/general-conference/2015/10/behold-thymother?lang=eng

(22) “A change in attraction should not be expected or demanded as an outcome by parents or leaders.” https://mormonandgay.lds.org/articles/frequently-askedquestions?lang=eng

(23) Nick Einbender, Post on “Mormons Building Bridges,” Sep. 18, 2018. https://www.facebook.com/groups/mormonsbuildingbridges/permali nk/1513907792043410/

(24) Steinmetz, Katy. “How Many Americans Are Gay?” Time. May 16, 2016. http://time.com/lgbt-stats/

(25) It is likely a much larger percentage. In another study, 20% of Millennials (ages 18-34) self-identified as LGBTQ; 12% of Generation X (ages 35-53); 7% of the Baby Boomers (ages 52-71). The discrepancy likely arises from an increase in acceptance and safety in the culture the Millennials are growing up in. This makes them more likely to come out as LGBTQ. There are probably equal numbers throughout history, but it wasn’t as safe for older generations to come out for fear of violence, rejection, loss of job security, and loss of standing in the community. See Gonella, Catalina. NBC News. March 31, 2017. https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/survey-20-percentmillennials-identify-lgbtq-n740791

(26) Eric D. Huntsman, “Hard Sayings and Safe Spaces: Making Room for Struggle as Well as Faith,” Aug. 7, 2018, BYU Speeches, https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/eric-d-huntsman_hard-sayings-andsafe-spaces-making-room-for-both-struggle-and-faith/

(27) “Questions and Answers.” BYU Speeches, Nov. 14, 2017. https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/m-russell-ballard_questions-andanswers/

(28) https://mormonandgay.lds.org/articles/love-one-another-adiscussion-on-same-sex-attraction

(29) Dr. Fatimah S. Salleh, Affirmation Conference, July 22, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dyoXa9z76v0

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Government is pleased to announce that they have secured CRYSTAL COHEN, that possess the power of LIGHT MANIPULATION. There is no doubt that Lake Grimstone will offer CRYSTAL the necessary help they need to learn to master their power.

Welcome to Lake Grimstone, PATSY! Anyone who so much as glances at your app can tell you put a lot of thought into Crystal and her development as a character! It’s clear that you are a wonderful writer and we look forward to having you on the dash! Your FC change is accepted. Now that you’ve been accepted, take a look at OUR MEMBER CHECKLIST. Please send in the account within 24 hours!

OUT OF CHARACTER

NAME / PRONOUNS:

patsy (but goddess of death is also acceptable) / she/her

AGE / TIMEZONE:

22 and i’m in pst !!

ACTIVITY LEVEL:

in all truth, my activity will vary - that is mostly because i currently work from home which might sound nice in theory but leaves me a little all over the place. that being said, i can gaurantee 4-5 days a week of activity, although i expect it’ll be much more than that! i’m currently a working writer so so long as i keep up with my deadlines, i’d like to spend the rest of my time doing writing i actually enjoy, so!

IN CHARACTER:

DESIRED CHARACTER:

Crystal Cohen

SECOND CHOICE:

despite the fact that crystal does not have any other apps, i’ll give this an answer just in case - rhea yates, although if it came down to the second choice i’d like to write a new app for her, if that’s alright!

WHY WOULD YOU LIKE THIS CHARACTER?:

when i was reading through all of your characters’ bios, i was falling in love with so many, and i really kind of started to freak out because i had opened up at least six bios in another tab to consider applying for. when i got to crystal’s i felt like i was being delivered curveball after curveball and that was so exciting.

one of my favorite qualities about crys is her honesty, and where it probably comes from. i imagine she’s always been this way, but i feel as though it likely increased tenfold after being turned in by her father - i think this really effected her ability to trust others around her and as a result she blurts out the truth. she says exactly what she’s thinking, i think in the hopes of getting some semblance of honesty in return. i think that this blunt honesty, though sometimes maybe too blunt, really goes to show that she’s trustworthy as a friend. you can’t expect the world to stop lying to you if you don’t stop lying to them, right?

i’m also interested in the really important detail of her being so observant. i think that this really opens the door to crystal being able to really empathize with others - which was probably also effected by the fact that her mother was a psychiatrist. i think that, in general, she loves human beings. humanity, maybe not, certain people, certainly not - but when someone observes people as much as she does, it’s almost inevitable.

which brings me to the absolute heartbreak of her mother’s death, and its result on crystal life. i think crys has a natural desire and inclination to help people, like her mother did - but one of the people her mother was trying to help murdered her, and i think an act of such violence from someone who shouldn’t have a reason to commit it would shake crystal’s entire worldview. it’s not surprising at all that she stopped writing - how could it be when something like that would almost halt her concept of people around her? to write is to understand people and after something like that, she probably doesn’t think she understands people at all like she used to.

now all of this combined brings me to her relationships with daniel and courtney. i think her relationship with courtney exhibits all of that caring and that empathy and, most importantly, her overwhelming desire to help people, even when they don’t ask for it. i just love that about her. her relationship with danny is more complicate dand i think it hurt her more than she’s willing to let on - after struggling so much with trust already, after her father and her mother’s patient, having her trust hurt on a smaller and personal scale, too, would have probably had a profoudly negative effect on her. i imagine that’s why she ended up back with danny at all - because she’s trying to mend her trust in people - but to have it broken again would be like breaking all over again, and it’s getting harder and harder to put herself back together.

so, i think that’s where she’s at right now. she’s trying to re-configure her understanding of the world and put together the pieces of who she used to be. i think she has to come to terms with the fact that she is a different person, though, and that she can never be the old crystal (why? cause she’s dead!) again. if she can adapt to this i think she can find what makes her happy again and start to trust people again - albeit much more carefully than before.

1 note

·

View note

Text

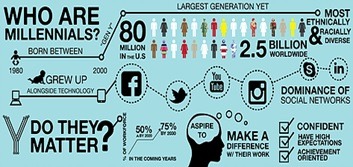

Things Boomers and Gen X Can Learn From the Millennials