#hopefully discourse will die down in a week or two and we can get back to the other sorts of stuff I tend to post

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

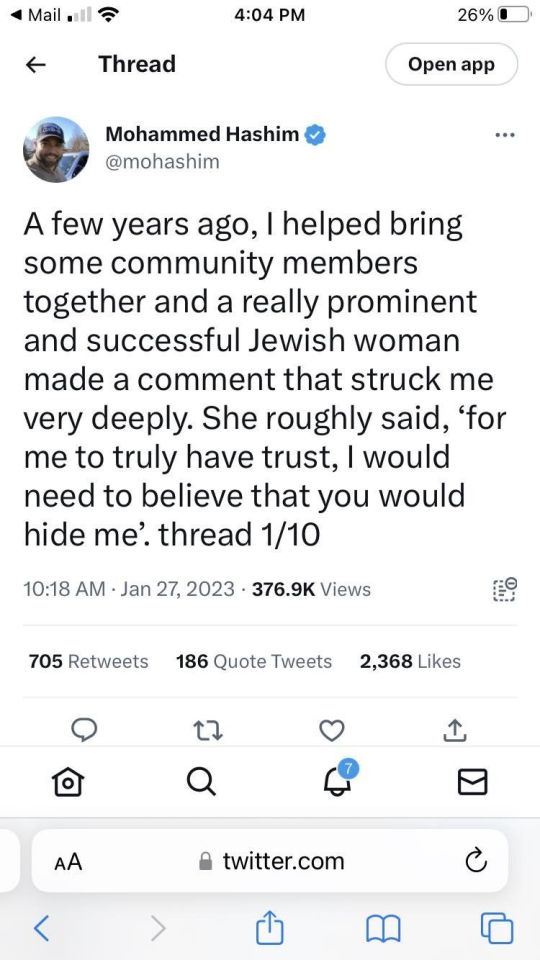

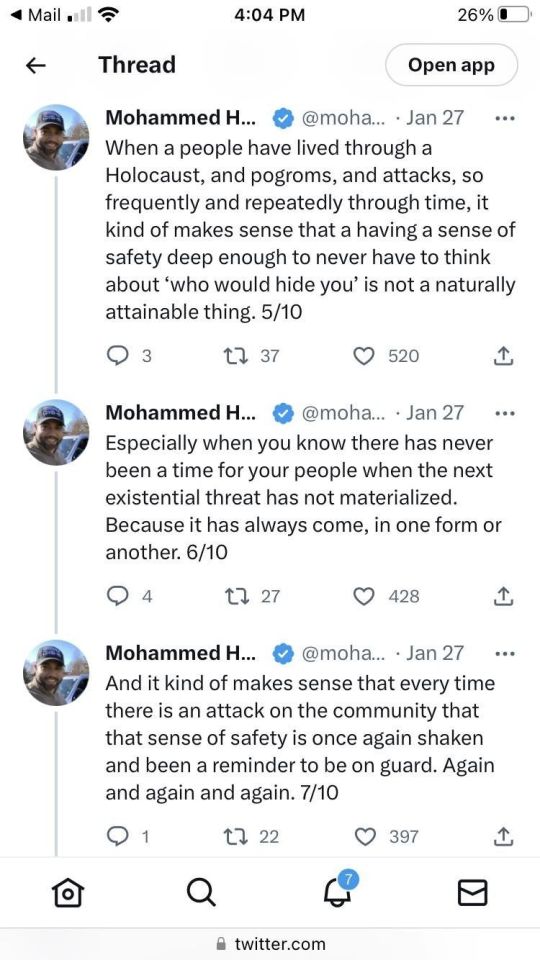

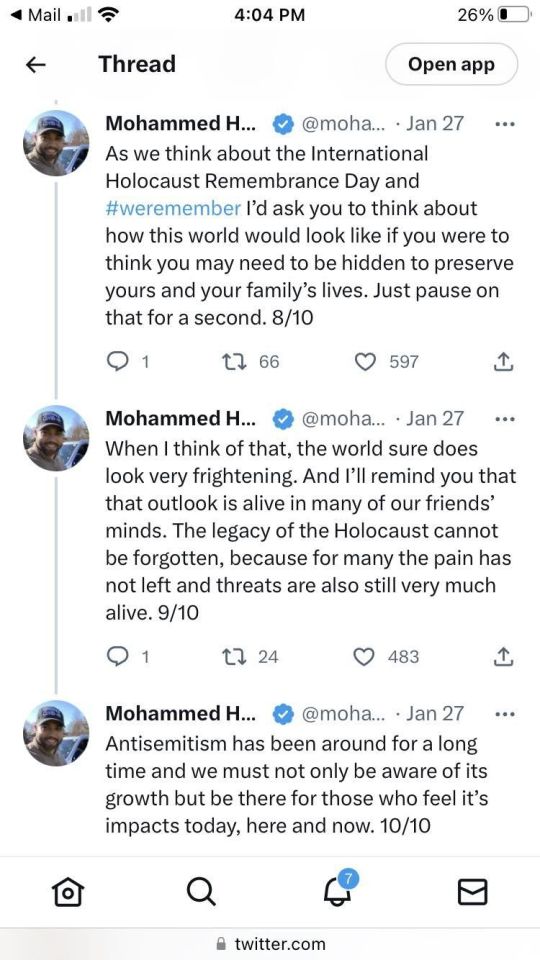

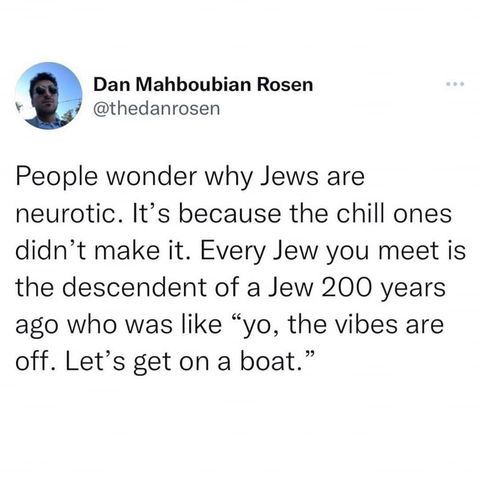

Would this person hide me?

Would this person turn me in?

Is it safe to tell this person I'm Jewish?

What is the plan for leaving? (Where am I going? How am I getting there? What's coming with me? How much of my life can I shove in a suitcase?)

What is the threshold for leaving? (Remember to err on the side of caution. If you wait too long you won't be able to go.)

All these things are questions that Jews ask themselves. And while obviously, the worst results of antisemitism are the actual attacks against Jews, especially those that result in the loss of life, I think that it is still pretty devastating that Jews can't feel safe in their own lives.

A person shouldn't have to think that the question "will this person hide me?" needs an answer. But Jews know that it has in the past often enough that it's reasonable to think that it might in the future, and that if it does, that answer is gonna be really important.

this sentiment is so true

#cw: antisemitism#I have a rough outline of an escape plan#I'm sorry for all the antisemitism posts this week#it's that damn game#and all the people who are saying that it's not that bad#hopefully discourse will die down in a week or two and we can get back to the other sorts of stuff I tend to post#I feel like I'm beating a dead horse

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

ok so… i wanna talk about the “sarawatine didn’t kiss and that’s bullshit” discourse that has been going around in light of the finale.

first, people who say they wished they had kissed are only valid if they aren’t disgusting fujoshis who want a kiss just for the sake of wanting it, without understanding the context and motivations behind such action. so if you are a fujoshi, get tf out of this post.

i think the major reason why so many people are upset we didn’t get a kiss is because of cultural differences. and i speak about this matter from my own point of view, since im literally from the other side of the globe.

as a south american, more specifically as a brazilian who was born and raised here, i can say that our way of showing affection is drastically different from how ive seen most asian couples show affection to each other. (disclaimer to say im in no way an expert on this matter and what i say is based on hearing about asian friends’ experiences and documentaries lmao so don’t come for my head and if i say something wrong please point it out!)

here in brazil, you will see people kissing, hugging, holding hands, and whatever other form of physical affection there is everywhere you go, whether it be a straight or queer couple. it’s just natural for us. we greet each other with a hug and a kiss on the cheek, it doesn’t matter if you know the person you just greeted or not. we even have a whole holiday that’s basically for partying, dancing and kissing (carnaval!). brazilians already flood each other with physical affection without being in a romantic relationship, so of course for me it’s weird when i watch a couple just establishing their relationship and a kiss doesn’t follow their confessions.

a standard brazilian love confession would consist of two people declaring their love for each other, happily smiling, and then they would kiss because they love each other and they are happy to be together, and a kiss is how we were taught to express such feelings. but that doesn’t apply only for brazil, or for south america, it’s a reality in a lot of cultures in many countries around the world. but i also know that’s not universal and it doesn’t apply to everyone.

i get it, that’s not how asians were raised and perhaps for them my culture can be an absurd, but i won’t lie and say a part of me doesn’t expect a kiss every now and then in asian shows, especially after asking each other to be boyfriends or laying down in the grass under a starry night, because that would be extremely realistic and natural in the cultural context im in.

i know it’s not fair to expect elements from my own culture to feature in shows and series from a country so far away from mine, but i do get where some people might be coming from when they demand a kiss like in sarawatine’s case. because for them that would be the utmost romantic gesture, that would show us, the audience, the characters really do love and care for each other.

sarawat and tine have other ways of showing their love for each other, and they are all just as beautiful and valid as a kiss, but i feel like, after everything they went through, especially in episode 12, after solving their problems and agreeing to go back to dating, the fact that they just high fived each other was so… out of place? you would high five your friend after winning a match, or high five a kid after they finished playing around, but would you simply high five your “ex” boyfriend who just wrote a whole song for and about you when you realised everything that happened was a misunderstanding and you are willing to give it another go????? im not saying they should’ve kissed right there in front of the crowd (because that would be out of character for them, esp tine) but… they should’ve at least kissed at some point (and i would die and kill for tine to initiate a kiss tbh), once they didn’t kiss ever since they started dating and moved in together. for me, it would have made sense and would fit the story and the characters, and also make it feel even more realistic. but it didn’t happen, and that’s ok.

people have the right to be frustrated about the lack of kisses in 2gether, but those same people (including myself) have to understand they are choosing to consume a piece of midia that depicts a culture that diverges so much from their own, and that culture has its own social behaviors, manners and values. if you are bothered with the lack of good kisses in bls in general, then i guess thai bl is just not the right genre for you, especially gmm shows (we all know gmm’s poor history of kissing, both straight and queer). and this isn’t much about the thai industry, but we can’t forget how queer affection on television can be censored over the tiniest of things on asian midia which ://

so please don’t go around spreading hate to the crew and director or even to the actors themselves because you feel robbed of a kiss (esp because you can tell it was a scene from the very beginning of the filmings when bright and win were still building the beautiful friendship they have today so perhaps that’s why it felt so awkward dbhdjsj). let’s not forget that 2gether is a show way beyond a simple kiss. it’s a show about love in its purest form, and all the hardships that come with it. it’s a show about self discovery and finding your own worth. it’s a show about growth in so so so many ways. do not let a tiny thing cloud your judgment to the amazing show 2gether was and to the incredible work everybody involved did, and the efforts bright and win did to portray such beautiful and raw characters to the best of their abilities.

i guess i just used this as an excuse to vent and try to deal with the fact that, sadly, 2gether has come to an end. i’ll miss this show so so much because i hold it very close to my heart and it has a really special place in my life rn. but yeah, it did end, liking it or not, and im just so thankful for bright, win and the crew of 2gether for these fantastic 13 weeks we had together and for all they’d done for us. but hopefully season two, or an ourskyy ep, or a special ep for the new book volumes await us………….. who knows

#dawn.txt#just a big rant about something that has been on my mind for a while now#the cultural divergences from my culture to asian culture are just SO BIG#like if 2gether was a br show EVERYTHING would be SO different its crazy to think about it#and im so sad:( just want 2gether back already:(#next friday is gonna be a blow on my head bc I Am In Denial. #2gether#2gether the series#sarawat x tine#dawn watches 2gether#last time ill use this tag:(

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Call Me by Your Name: Is it better to speak or to die?

Original text by Hristiana Hinova

Illustration: elysieeh

A ten-minute ovation follows the film’s screening at Sundance. Director Luca Guadagnino opens Twitter and reads about people jumping and dancing on the streets after having seen his film. It is one of those rarely made films which produce an incredible sense of euphoria that lasts for months to come. Last year that place was held by American Honey. Both films are a spectacle for the senses—gentle monsters whose visuals are electrifying and the feeling they leave behind is truly truer than the truth we witness every day. Call Me by Your Name is a film about Love, the kind that turns life into an event, and emitting such an emotional charge life itself becomes an event.

The 24-year-old American student Oliver is completing an internship at professor Perlman’s (his Jewish-American archeology professor with French and Italian roots; played by Michael Schulber, whose Oscar nomination hopefully becomes a fact soon) villa in the north of Italy. The atmosphere of the house is idyllic. The Perlmans are a dream family—highly educated, beautiful people who speak freely about philosophy, history and linguistics and kiss and hug whenever they pass each other on the corridors of the house. Elio, the professor’s son (an impressive debut starring Timothée Chalamet) is a 17-year-old spiritual and talented boy; he spends his days studying classical music, reading books, cycling and going out to bars in the evenings.

Call Me by Your Name starts straight off with the conflicting event: Oliver's arrival. Oliver is an imposingly handsome and confident guy; the ancient Greeks have a word for it—kalokagathia: a Platonic ideal consisting of the harmonious combination of bodily, moral and spiritual virtues. During the first few minutes of the film, he is the object of adoration by every one of the characters (apart from the Perlmans, there are also minor characters, the most prominent of who is Elio's girlfriend, the French Marcia, played by Esther Garrel).

What happens next is magic: Elio's love for Oliver goes through several recognisable stages, which are translated on screen with a masterful ease of the camera: it glides among the characters effortlessly, like a puff of wind. (Behind the camera was Thai Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, who has also worked with Apichatpong Weerasethakul on the dreamy, mysterious and visually perfect Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, awarded with the Golden Palm at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival.) Director Luca Guadagnino had the following to say in this regard: "We had a Buddhist behind the lens. And you can see it in every frame."

In order to convey my thoughts in a more organised way, I will divide the text into 5 parts. These 5 parts correspond to the 5 states of mind the main character Elio goes through during the 3 weeks in which the love between him and Oliver develops. This is an attempt to decode the power of the film, which I believe is rooted in the absolutely brilliant journey through the universal emotions of love. Call Me by Your Name wonderfully visualises the inner world of a person in love and the most elated, most intense states of mind that his enchanted soul can go through. I will include a few quotes from Roland Barthes’ A Lover's Discourse: Fragments which to me is the most poetic and refined translation of the love emotion into words. Not to show off but to present you the pleasure that is Barthes’ work. This film is the same kind of translation, slightly more accessible—but no less subtle and emotional.

For at least a year I hadn’t seen a love story that could move me so much with its genuineness. One of the best qualities of the film is its script: it lacks an antagonist and a conflict. According to textbooks, this is not how you write a script. It is risky—some might say even wrong. Since it doesn’t have the stereotypical Romeo and Julietesque problem where an external force interferes with the love of the two, nor is there a serious hesitation in some of the characters. Nobody dies. Nobody is less fortunate than the other, no one is whiter or darker than the other. We witness two people fall in love and thus create paradise, and—trust me—this is one of the most exciting stories to tell.

Desire This is the third and final instalment in Luca Guadagnino's thematic "Desire Trilogy”. The previous two being I Am Love (2009) and A Bigger Splash (2015). According to the director, the first one is a tragedy, the second—a farce, and the third one—a dream. While in both previous films there is some tragicomic element which works as a warning following the desire, Call Me by Your Name does not have one. Here, loving does not lead to anything bad. The pain after the loss is not harmful.

The film starts off with a half-naked Elio who must quickly vacate his room for it is to be occupied by the guest Oliver. Elio’s house is a spacious and cozy one (with doors open all the time and delicious meals being prepared in the kitchen); whichever room you enter, it is full with books you can read under the huge windows that let in the generous afternoon sun. Everyday life is a wasteful delight. The viewer sees this and sinks into his seat light-headed, dreaming of a similar life. Call Me by Your Name manages to strike a chord in us that is rarely touched; the melancholy for a paradise not yet lived, one ripen by the caress of the graceful nature, kissed by the sky, hidden from the dusty, sore city eye.

The sexual desire is not stated immediately. The scene in which Elio and Oliver meet for the first time, for example, is filmed in a rather unconventional way for this type of narrative. Typically, love at first sight is alluded at by showing the reaction of the main character, the one who is to fall in love first, in a medium shot or a close-up. Here, however, the scene is as follows: through a half-open door Elio and Oliver shake hands. Elio is showing us his back. On Oliver’s face we can read a polite smile tired from the long ride. BAM! Nothing special. No escalating music, nor an entertaining frame. Simple.

There is a reason for this. The story is based on a novel (written by André Aciman and adapted by James Avery). The novel is told in the first person, from Elio’s perspective. Therefore, by default, this is a story that comes from the inner world of the main character, ie. we would expect less eventful and more reflective storytelling. The director wanted to keep it as is in the book and translate it on screen. Hence, Elio’s ’slow’ falling in love (expressed at a later stage in the film with the regretful words: "We wasted so much time"). The ‘slow’ in question is really nothing more than a developing character, a man who grows before the eyes of the viewer, a man who loves and is loved for the first time.

Elio’s desire for Oliver is shown with his long glances directed at Oliver from the distance: Elio watches from his widow how the object of his desire walks, goes for a bike ride, dances, hugs and kisses a woman. Elio experiences a moment of frustration: on the one hand, he knows what is going on inside him, but his body doesn’t know how to react. The boy seems to be overcome by a fever. This is why when Oliver touches him for the first time to massage his shoulder, Elio pulls himself to the side confused. Desire causes ambivalence: often, instead of pulling us towards the object of our desire, it pushes us away from it; and this reaction is a defence mechanism: “Do not enter the beast’s mouth, because there is no way out.”

Elio falls in love with Oliver also through the eyes of others. He knows that this is a man who his father, the professor, likes and respects. This is also a body that others talk about; watching him play volleyball, the girls whisper to one another that he is “more handsome than the guy from last year.” This is what Roland Barthes has to say on the subject:

The body which will be loved is in advance selected and manipulated by the lens, subjected to a kind of zoom effect which magnifies it, brings it closer, and leads the subject to press his nose to the glass: is it not the scintillating object which a skilful hand causes to shimmer before me and will hypnotise me, capture me? This “affective contagion,” this induction, proceeds from others, from the language, from books, from friends: no love is original. (Mass culture is a machine for showing desire: here is what must interest you, it says, as if it guessed that men are incapable of finding what to desire by themselves.) The difficulty of the amorous project is in this: “Just show me whom to desire, but then get out of the way!”

Anxiety When we cannot own something, we become obsessed with a fragment of it. After Elio becomes aware that he is in love with Oliver, he starts missing him. Oliver grabs his bike and disappears for a whole day. Elio is alone in the house. He goes back to his room and examines the beast’s dwelling. This is his very room, but changed forever—soaked in the presence of the one who is absent now. There are one or two marvellous shots where the camera focuses on Oliver’s swimming shorts hanging from the faucets in the bathroom. Elio grabs a pair of them, lies down on his bed and thrusts his head inside. This is the only thing he can possess. Just a fragment, and it isn’t even from Oliver’s real body. It upsets and scares him, but at the same time brings him incomparable pleasure. When else is pleasure confusing? Love is maddening: it tears you away from your own self and hands you over into the possession of something abstract like a Thought, Scent or Idea. Elio is lost in the labyrinth of the Other. And for the first time we can hear Sufjan Stevens’ amazing music in a moment of culminating anxiety. It is an exceptional scene: Elio’s face is blurred and it seems as though a film reel is passing through it. Elio is not a part of his own life—he is a projection of the collective, centuries old face of the One in Love: the one who has fallen victim to a spell.

The following scene: Elio is together with his parents and the three of them are sitting on a couch. He is resting his head on his mother’s lap. She is reading to them the story of a princess and a knight from some French romance; the knight is so much in love with the princess that he doesn’t know what to do about it. The horror that he experiences in regard to his feelings escalates in the lines: “Is it better to speak or to die?” This startles Elio, who realises that his choice is indeed ultimate. The scene represents a key dramatic situation. The one in love is faced with a moat: on the one side stands he himself, like a boy, bent with a frightened look over the abyss, on the other side stands a tall, noble man. Can he overcome the moat?

Heroism According to Joseph Campbell, in every story with a prominent protagonist there is a moment of initiation, i.e. the moment in which the boy takes on a challenge and thus embarks on a path towards maturity. For Harry Potter, for example, this is his departure to Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. In our Bulgarian folklore, on the other hand, the hero kills the three-headed snake which usually brings him great fame and the love of the greatest beauty.

What does Elio do to become a man?

Elio decides to speak. In spite of all the horror this action brings – putting yourself in a weak position, risking being misunderstood and humiliated, Elio exhibits courage and decides to confess. Courage, because confession is self-assertion and this is one of the manliest things to do: “I am here and this is how I feel. How about you?" As all the readers probably know, telling someone that you love them without knowing how they will respond to your feelings is a hard and painful thing to do. It can cost a lot of nerves, especially if one was brought up in the spirit of high classical values.

And Elio speaks. God, how good this scene is. I may even like it more than the last 10 minutes of the film. The scene is brilliantly conceived and filmed: Elio and Oliver are walking on the opposite sides of a monument commemorating the victims of the First World War. They are talking about history and Oliver is surprised by Elio’s vast knowledge. Then Elio, having gathered up the courage, says that he knows nothing. At least not about the things that matter. “What things that matter?” demands Oliver. “You know what things,” replies Elio after a thoughtful pause. He tells him everything by not telling him anything. Between them lies history – the stone monument, a symbol of suffering and heroism – and inside of them rages an equally important event: the Conversation.

Unity The fourth part of Call Me by Your Name shows the real relationship of the two after love has been established as a fact. It feels the longest. And this is how it is supposed to be, bearing in mind that this is a romantic film that is not specified by the genre restriction of either comedy or drama. The title of the film refers to exactly this part. Call me by your name are the words which Oliver gifts Elio and which actually carry all the charge of their relationship: true merging is when you don't differentiate yourself from the other, being so much in love that you’re sinking into the other. This is the moment of culmination: you are one with your Desire and your Desire is one with you. There is no conflict nor drama. The world is just a prolonged touch. Everything is simple and the pleasure is inexhaustible. A quote from A Lover's Discourse: Fragments:

Definition of the total union: that is “the one and only pleasure” (according to Aristotle), “joy without blemish and without impurity, the perfection of dreams, the limit of all hopes” (Ibn Hazm), “the divine splendor” (Novalis), this is: the inseparable peace. (…)

Dream of total union: everyone says this dream is impossible, and yet it persists. I do not abandon it. "On the Athenian steles, instead of the heroicization of death, scenes of farewell in which one of the spouses takes leave of the other, hand in hand, at the end of a contract which only a third force can break, thus it is mourning which achieves its expression here . . . I am no longer myself without you." It is in represented mourning that we find the proof of my dream; I can believe in it, since it is mortal (the only impossible thing is immortality). SYMPOSIUM: Quotation from the Iliad, Book X.FRANÇOIS WAHL: "Chute.”

Conclusion The fifth and last part, the one when Oliver leaves, has an almost instructive function. The father has the role of a sage, a teacher (figuratively and literally). He is supposed to evaluate the situation and interpret its meaning. He is the one who has studied art and the human nature throughout the centuries, the way in which humanity asserts itself. And yet, he is the man who admits that he has never been so close to the perfection of human relationships as his 17-year-old son has. The father’s revelation is striking: in the absence of love, one wears out. In the absence of courage to love, one withers away. Once again, this brilliant monologue deserves an Oscar nomination.

There are films that are magical. Do not doubt that Call Me by Your Name is one of them. And to put out the swollen pathos, I will tell you that the peach scene has been tested (in real life) both by Luca and by Timothée Chalamet. Seems like one can have fun in the most unexpected places!

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ruffnut + 💀

Hiccup looked worriedly out toward the tree line that surrounded the Clubhouse, shielding his eyes from the setting sun. “Okay, this might be bad,” he muttered, and the burble from his dragon nearby echoed his concern. “She’s been gone far too long.”

He walked from the balcony back to the fire pit table, where the other riders were watching a Maces and Talons game, Astrid versus Dagur. Tuff wasn’t scanning the horizon worriedly at all, more interested in the game.

He made a sound of disappointed protest when Hiccup tugged him slightly away from it.

“Aren’t you wondering where your other half is, Tuff? Ruffnut been gone all day.”

“Don’t fret, H,” Tuff shrugged easily, glancing over distractedly as Astrid exclaimed in frustration. “Ruffnut’s out on a soul searching errand, to find her inner nut. My poor sister has such a thick, hard shell, that could take days. If not weeks.”

Hiccup frowned. “That’s what I’m worried about. Remember what happened the last time you went searching for your ‘inner nut’? You came back bitten after a wolf attacked you.”

“Uh, no, it was a Lycanwing, remember?” Snotlout called over. He laughed and scooted closer to Dagur. “I totally convinced that knucklehead he was gonna turn into a were-dragon.”

“Really, Snotman? Then what happened?”

Snotlout opened his mouth and then shut it, remembering that tale hadn’t ended in his favor. “He got better,” the dark-haired boy muttered, sulkily.

“Fear not, Ruff is definitely rough enough to handle anything she may encounter out there. If not, well, we’d all hear her scr—“

Tuff stopped mid sentence and suddenly turned white as a sheet.

Hiccup was about to ask him what was wrong, but then all the dragons snapped their focus in the direction of the woods, Toothless growling warily. Just barely, over the sudden silence, there was a thin terrible sound - like a dying rabbit.

Tuffnut ran for the stairs, nearly knocking Hiccup over. Toothless caught him from falling as he shouted and together they ran after Tuff, who was moving faster than Hiccup had ever seen him. Judging from the sound of the footsteps charging behind them, Hiccup figured everyone in the Clubhouse had come barreling after to see what was wrong.

They found Tuff embracing a shaking, babbling form. Ruff’s eyes were wild, hair all undone out of her braids, and there were twigs in it - making it look like she had antlers. She was half-shrieking something, as Tuff was trying to talk to her soothingly, not having much luck.

“We have to get off the island! We’re all gonna die!” She screamed, shaking her brother violently by the collar of his vest. He grabbed her in a hug that was part headlock.

“Calm down, sis! What in Loki’s name did you see out there?”

“Something awful! Something hideously terrifying! And it’s coming straight for us!” Ruff screamed in his ear. Tuff winced, and Hiccup decided to try and give him a hand.

“Ruffnut, whatever it is, you’re safe now. We can face this thing together.”

She angrily broke free, flipped her hapless brother to the ground and stepped over his body with a crunch to get in Hiccup’s face.

“Oh, oh, don’t you even think about patronizing me! You got us all into this mess in the first place - your adventuring, one-legged, tousle-haired shenanigans have finally doomed us all!”

Hiccup just blinked, completely at a loss.

Brushing himself off, Tuff flashed him an apologetic smile, but before he could try to diffuse her, Snotlout flew to Hiccup’s defense.

“Yeah right! I know an epic prank when I see one. You’re both totally faking this, and let me guess, somethings gonna come ‘charging’ out of these bushes to hit me in the face, but it’s gonna be attached to a wire, and it’s probably gonna be something lame like a stuffed bunny with deer horns on its head!

“And you’ll both laugh and say ‘Loki’d!’ and maybe one person will think it’s funny. There, I solved it, now can we all go back to the match already? This is all so predictable.”

Tuff and Ruff stared at him, then Tuff looked hopefully toward the bushes, grinning widely. When nothing jumped out to smack Snotlout in the face, he turned back to his sister and put his hands on his hips. “Well, now I’m disappointed.”*

“I’m serious, bro! This isn’t a joke! I saw our death itself reflected in that thing’s eyes, and it’s coming straight for us!”

“Neat!” commented Dagur, after a long tension-filled silence. Heather rolled her eyes and jabbed him in the ribs with an elbow.

At that point, something swept unseen across the leaves in the forest - the sound grabbing everyone’s attention - especially their dragons. Sleuther and Toothless took point as the others flanked their riders, baring their teeth and growling. The noise and small flurries of movement seemed like it was being gusted toward them until all at once it stopped.

A ball of white fluff with dove-like wings, rabbit-like ears and a tufted tail leapt out of the darkness, landing before them with large liquid black eyes glistening inquisitively. It tilted its head and the other dragons quieted but remained tense.

The fluffy dragon went rawr at them. It sounded more like a kitten sneezing than anything remotely threatening.

“Awww,” Heather and Fishlegs both cooed at once, but Ruffnut waved her hands in alarm.

“No, no, no, don’t fall for it like I nearly did! It’s a murderer! Every single one of them!” she yelled, half climbing onto her brother’s shoulders. “Murderers!” Ruff shrieked, clinging to Tuffnut’s face.

“Sis?” he whimpered. “Can’t breathe.”

“Ruff, it’s amazing! An entirely new class of dragons! I didn’t know they could grow feathers like birds! We’ve seen dragons with many different scale types, but never feathers!” Hiccup reached out his hand to the small dragon.

It trilled sweetly, sniffed his hand, then promptly launched itself at Hiccup’s face, mouth suddenly open too wide with far too many teeth. He shouted in alarm, falling back on his ass and Toothless jumped in to smack the thing away with his tail fin before it could bite Hiccup.

Suddenly the woods were full of ominous rustling, clicking, and angry chirps.

“Guys, I don’t say this very often, but - uh - RUN AWAY!” Dagur yelled and turned to follow his own advice, yanking both his sister and Fishlegs after him. The others followed suit, Tuff still carrying Ruff, as the forest seemed to explode.

An entire herd of angry murderous puffballs chased after the group as they took to their dragons and to the relative safety of the air and higher buildings. The little dragons couldn’t get very high with their cute cherub wings but they certainly made up for it by maliciously snapping at the air just beneath them.

“I told you so!” Ruff yelled, jumping from her brother’s back to Barf’s neck.

“Yeah, you did,” Hiccup sighed, while Toothless snarled and hissed at the frothing flock below. “So while we’re up here, who wants to name them?”

“Oh my gods, is he serious?” Snotlout asked flatly. Everyone’s expressions answered him in volumes.

“Ooh, I’ll start!” Tuff volunteered. He pointed below. “That one’s Monty, that’s Mr. Praline, we could name that one Python -“

“I vote for death-pigeons,” Astrid volunteered.

“Wensleydale, Mr. Badger, Arthur -“

Hiccup sighed, supposing he’d brought the resulting snark and discourse on himself. Well, at least they were all safe more or less, and hopefully the little dragons dispersed before too long.

“Ruff? Tuff? I hope you know neither of you are ever allowed to go searching for your inner nut again?”

The twins glanced at each other and sheepishly gave him two thumbs up.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading between the Vines Transcript

[Music]

Carrie Gillon: Hi, and welcome to the Vocal Fries podcast, the podcast about linguistic discrimination.

Megan Figueroa: I’m Megan Figueroa.

Carrie Gillon: I’m Carrie Gillon.

Megan Figueroa: How’s it going?

Carrie Gillon: Better. Yesterday I started to feel like maybe I was getting bronchitis. Then I used an inhaler and I feel better again today. But I always feel better in the morning. I don’t know.

Megan Figueroa: I always feel better at night.

Carrie Gillon: Yeah. Not with whatever this is.

Megan Figueroa: I wake up and feel terrible, usually, with things. Interesting.

Carrie Gillon: Me too! Not at all with this one. Not at all.

Megan Figueroa: Oh, could you imagine getting bronchitis from this right now? You don’t wanna go to the doctor if – you know.

Carrie Gillon: Well, I almost always get bronchitis anytime I get the flu after I moved to Arizona. Before that, I never had it in my life. Something about the dryness of the air here – and I’ve been trying to sit with my face over a steaming bowl of water but probably not doing it enough, frankly. Hopefully, I nipped it in the bud.

Megan Figueroa: I’m still COVID-free. This is the first week where I felt emotionally transitioned into this new normal a little bit. It’s been a little bit better. People are still assholes. That hasn’t stopped.

Carrie Gillon: No. Yeah. In some ways, they’re getting more asshole-ish, like full on eugenics.

Megan Figueroa: You’ve noticed that too? There’s a lot of that happening.

Carrie Gillon: There’s a lot. I mean, it was already in the air before. Somehow, eugenics was coming back, but it’s just gotten worse in the last month.

Megan Figueroa: Maybe because we’re all – I dunno. We’re thinking about health issues and bodies. I don’t know what it is.

Carrie Gillon: It’s because they want the economy to be back to normal, and so they want it to be okay that some people are gonna die. They’ve got it in their head that it’s only people with pre-existing conditions and only people over a certain age, but that’s not true. It’s, yeah, mostly the case, but it’s not 100% the case. It’s like anybody could die. The good thing is probably the death rate is a lot lower than we think because there’s just been so much under-testing.

Megan Figueroa: Wouldn’t that mean there would be more?

Carrie Gillon: A lot more cases, but the death rate’s lower.

Megan Figueroa: Oh, I see. Because the cases would go up. Got it.

Carrie Gillon: Part of the problem is we don’t know that all the deaths are being counted. Unfortunately, there’s uncertainly in both things, but the uncertainty is greater when it comes to the number of actual cases because the testing has been pitiful. But anyway.

Megan Figueroa: In the US.

Carrie Gillon: No, not just the US. The US is one of the worst offenders but, no, the UK’s been bad. I mean, it’s not great in most places.

Megan Figueroa: Well, all right. We know you all don’t wanna hear about Corona all the time.

Carrie Gillon: Forever and ever? I know. Unfortunately, it’s where we’re at and so we’re gonna be talking about it until – I dunno.

Megan Figueroa: I mean, how could you not? My brain is – I’m not functioning the same way I was before. It’s always there, so I dunno how people – I mean, if you can ignore it for some periods of time, that’s great. I can do that too. But it’s like, I’m not the same. I can’t think the same.

Carrie Gillon: I have noticed that I’ve stopped freaking out when people are hugging and touching each other on TV shows and movies. For the first week or two, it was really freaking me out. Now, I’m like, “Oh, it’s fine.” Because we will get back to, maybe not as touchy – maybe we won’t shake hands anymore, which I think would be good because I don’t really wanna shake people’s hands. But anyway, I feel like, “Oh, okay. Well, some of this will come back. We will get there. It’s just a matter of time.” I’m feeling a little less stressed about watching shows.

Megan Figueroa: Oh my god. I didn’t even think about that. I was, yeah, thinking about how I wasted some of my hours watching the Tiger King. There was a lot of touching in that show. I was like, “Eh, that’s not what’s bothering me.” [Laughs]

Carrie Gillon: Oh, well, yeah, that show – I have a lot of things to say about that show.

Megan Figueroa: That’s on our other podcast. [Laughter]

Carrie Gillon: I found it deeply unsettling, that show.

Megan Figueroa: So did many others.

Carrie Gillon: It got really dark.

Megan Figueroa: It did.

Carrie Gillon: There’s a new episode coming out today, I think. Even though I feel really dirty, I’m probably gonna watch it.

Megan Figueroa: I have to continue. It’s like, I dunno, it’s a little bit of my – the part of me that has to finish things that I’ve started. What am I saying?

Carrie Gillon: Completist. You’re a completist.

Megan Figueroa: Yes. There! Okay.

Carrie Gillon: I’m usually a completist. There are some things I have abandoned, but it’s pretty rare. I’m feeling the same pull. I’m like, “Well, if there’s another chapter” – even though I thought that what the filmmakers did was kinda reprehensible – yeah, I gotta watch.

Megan Figueroa: I know.

Carrie Gillon: Anyway, language stuff. Speaking of TV, last night I was watching part of the SNL – I didn’t watch the whole thing – but I watched the news part.

Megan Figueroa: The Weekend Update.

Carrie Gillon: First of all, it was very strange because no one could be in the same room together, right, obviously.

Megan Figueroa: Right. Oh, wait! We talk about this kind of today in the episode about humor about how things hit differently.

Carrie Gillon: Yeah! It’s true. It’s related to what we say about This Week Tonight. It ties into this episode. Also, it’s – the jokes land differently but, okay, with the news segment, what they did was they had a bunch of other people on the Zoom channel with them. They were all laughing. It was really weird and distracting and I hated it. What I really hated was one of the jokes that Collin Jost told. I just relistened to it, but I’ve already forgotten exactly what he said, but something like, “Dr. Fauci is the first person in a long time that has a thick accent and is still smart” or something like that.

Megan Figueroa: [Sighs]

Carrie Gillon: Yeah.

Megan Figueroa: There’s so many things wrong with that.

Carrie Gillon: Yep.

Megan Figueroa: For one thing, everyone has an accent. This “thickness” idea is, like, what?

Carrie Gillon: Is fraught.

Megan Figueroa: It’s so fraught.

Carrie Gillon: What does it even mean to have a thick accent? Please define it for me.

Megan Figueroa: Then, what is the opposite of that?

Carrie Gillon: A “thin” accent? [Laughter]

Megan Figueroa: I was gonna say, “A skinny accent?” How absurd.

Carrie Gillon: Also, what does that say about his particular accent? He’s an Italian American. He’s got an Italian New York accent, which we don’t hear that much anymore. It doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist, but it’s not on television that much unless you wanna code the person as –

Megan Figueroa: A gangsta?

Carrie Gillon: A gangster or working class or both.

Megan Figueroa: We have these preconceived notions about someone with his accent – absolutely. Absolutely we do. General “we,” not me and you.

Carrie Gillon: We’re susceptible to it as well.

Megan Figueroa: Oh, yeah! I definitely, when I was younger, the only experience I had with anyone from New York would’ve been from TV. I definitely grew up thinking they were all like The Sopranos. It’s just so fucking irritating that Collin Jost has this platform and he is using it to further this accent-based discrimination that left-leaning people are completely okay with still.

Carrie Gillon: Yep. Still. There’s certain things that are still acceptable and that’s definitely one of them.

Megan Figueroa: There’re a ton of people that we would probably consider people that we agree with on a lot of things are gonna find no issue with that joke. In fact, they will laugh and think it’s a good joke.

Carrie Gillon: Well, they definitely were laughing on the Zoom room.

Megan Figueroa: They were?

Carrie Gillon: Yeah. I was very disappointed in many ways with that Weekend Update.

Megan Figueroa: Yeah.

Carrie Gillon: Anyway, today’s episode is really fun. We talk about anti-hegemonic racial humor.

Megan Figueroa: Yes! And we get to talk about Vine and lots of other fun things that I actually don’t – I’m not a Vine person, so I was happy to learn about it even though it’s gone now.

Carrie Gillon: You can still watch Vines.

Megan Figueroa: It’s true. Enjoy!

[Music]

Megan Figueroa: Today, our guest is Kendra Calhoun, a PhD candidate at UCSB who is interested in socio-cultural linguistics, linguistic anthropology, language and race, online discourse and multi-modality, humor and activism on social media, language attitudes and ideologies, youth language and culture, and African American language. Thank you so much for coming on, Kendra. We’ve been wanting to have you for a while.

Carrie Gillon: Yeah! Thank you.

Kendra Calhoun: Oh, thank you. Thanks so much for having me.

Megan Figueroa: Absolutely. You have a paper out. It’s called “Vine Racial Comedy as Anti-Hegemonic Humor: Linguistic Performance and Generic Innovation,” which examines the discursive features and complex socio-political commentary of anti-hegemonic vine racial comedy. Let’s break that down. What are “discursive features”?

Kendra Calhoun: “Discursive features” basically is a fancier way of saying characteristics related to discourse. Usually, it’s when someone’s describing a particular type or genre of discourse, those are the features or characteristics that they’re focused on. Depending on what someone counts as discourse, or what they see as falling under that umbrella, those features could look a little bit different.

For me, discourse can be written language. It can be speech. It can be signed languages, which I don’t think anyone can really contest. For me, discourse also includes embodiment and visual communication, like images. So, the discursive features I would include in something, like I talk about in the paper, might be different from what someone else might include. I talk about phonological features, things like word choice, gesture, facial expressions. Those would all fall under the category of discursive features for me.

Carrie Gillon: What is “anti-hegemonic humor”?

Kendra Calhoun: Yes. Anti-hegemonic humor, as I came to understand it – Otto Santa Ana has a paper from 2009 where he looks at the anti-immigrant jokes that Jay Leno makes in one night of his stand-up comedy. Of course, there’s anti-hegemonic and then there’s hegemonic humor. Basically, the key distinction between those two is who’s the butt of the joke – who’s the humor targeted at?

Hegemonic humor is humor that targets already structurally or socially marginalized groups. Jokes that target people of color, queer people, poor people, homeless people – all of that would be hegemonic humor because, by making those people the butt of the joke, you’re upholding the status quo, upholding the systems where certain people already have structural and hegemonic power. That’s why it’s hegemonic in that sense.

The flip side of that is anti-hegemonic humor where the target or the butt of the joke is the people or the institutions or social structures that uphold power, have structural power. Anti-hegemonic humor would target rich people, white people, politicians, anyone who has that structural or existing power within society.

Megan Figueroa: What might be a mainstream example of anti-hegemonic humor?

Kendra Calhoun: One that I think is a really good, really clear example of this is Patriot Act with Hassan Minhaj on Netflix because he’s using humor as the means through which to make social commentary about things like political corruption, a government oppressing its people, wealth and equality, corporations contributing to global climate change. Humor is the means to make this social commentary, but who is being targeted is very clearly people in institutions with power and usually people who are abusing that power in some way.

[Excerpt Patriot Act]

Hassan Minhaj: Finish this sentence, “Canada will not sell any more weapons to Saudi Arabia. Period.” [Laughter] I’m sorry, I messed that one up. “Canada will not sell anymore weapons to Saudi Arabia, please.” That’s just a statement.

Justin Trudeau: That’s a good statement.

Hassan Minhaj: You said nine months ago you guys would be examining, and it takes about three months to study for the LSATs, so that’s a pretty good examination time. You could announce it right here, right now, “We’re cancelling the deal.” We got it right here, while on camera –

Justin Trudeau: We take our legal responsibilities and the breaking of contracts very seriously in this country.

[End excerpt]

Megan Figueroa: Then, would The Daily Show have been an example of this too even with – well, with Jon Stewart and then now with Trevor Noah?

Kendra Calhoun: Yeah. And kind of the – not necessarily the spin-offs – but shows that have been inspired by that like The Daily Show, Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, yeah, the humor-comedy news shows where they are making really important social commentary/political analysis, but it’s based through humor as a way of getting people to connect with that, those are all really good examples.

Stand-up comedy, currently and historically, has also been a really good source of this. I think now, especially that there are more women comedians, comedians of color, queer and trans comedians who are now being essentially given space that they’ve been denied. If you look across Netflix and HBO, just the diversity of people who have comedy specials has really expanded. I mean, a lot of humor scholars have written about how people from marginalized backgrounds are more likely to include that kind of social and political commentary in their comedy, in their humor. Now that people from these groups are able to take the stage and make this commentary in their comedy, we’re seeing it a lot more visibly or a lot more publicly than before. I think that’s really good to see.

Carrie Gillon: I’m just gonna go back to Last Week Tonight because this last episode was kind of interesting because there was no audience and it felt very serious but, at the same time, he was still making the same kinds of jokes, but they landed differently because there was no audience. Anyway, we just live in interesting times.

Megan Figueroa: It really did. He was making jokes about hamster on TikTok.

Carrie Gillon: Yes. Which we will get to.

Megan Figueroa: Yes. But it’s true that they land differently when you don’t hear the audience laughter or their reaction. It’s really interesting. So, you’re talking about space opening up for more people to have Netflix shows and all of this. Does this – I’m guessing that anti-hegemonic racial humor has been around forever – but is this giving rise to that in a different way or giving it more of a platform?

Kendra Calhoun: I think in some ways, yes. To go back to your first point, yeah, anti-hegemonic racial humor – so many words – has been around for a long time. Glenda Carpio has a book from 2008 called “Laughing Fit to Kill” where she traces this history of African American humor from the time of enslavement. She has, actually, a whole chapter on Richard Pryor and Dave Chapelle. She’s also looking at different texts and literary forms about how we can trace this tradition, essentially, of using humor as a way of coping and undermining structural power in these ways.

I think now there’s maybe more types of racial humor or different ethnoracial communities. People with different ethnoracial identities are being able to create humor that’s more specific to their experiences. There’s, of course, gonna be some similarities where – maybe not necessarily white people – but whiteness or white supremacy as a social structure is a shared theme of what people are making the target or the butt of the joke within this humor but then grounding it in their very specific cultural experiences and usually very individual experiences of what it was like growing up in their household, the neighborhood they lived in, what their family was like, things like that.

Carrie Gillon: How about Vine? How did Vine producers use Vine to create this kind of comedy and how is it different from other ways of making anti-hegemonic racial humor?

Kendra Calhoun: Vine – I am a self-described Vine groupie. Anyone who looks at my Twitter will see that that’s in my bio. One of the things that I loved about Vine was how creative people could be with it. On the surface, it seems really simple or almost this 6–7-second limitation would really limit people’s creativity, but I think in a way it forced people to think outside the box and be creative in ways they wouldn’t have otherwise.

Vine has a lot of parallels with – or Vine comedy has a lot of parallels with stand-up comedy, also sketch comedy in a lot of ways, since it is this audio-visual platform. In the article I talk about – I think I use the term “semiotically dense” videos. “Semiotic” is just referring to meaning. Because the videos are so short, they basically have to use any and every meaning-making resource that they have available to get the joke across in this short period of time.

A lot of times there are multiple people in the video. They could all be playing a different character. Sometimes, one person might play multiple characters. They might have costumes on. They could use props. Vine had the function where you could upload a video that was already edited so people could do sound effects, visual effects, voice-overs, add music. There were lots of different resources people were using to make meaning in these videos.

One thing that was really prominent, particularly in these racial humor videos, was the use of stereotypes, which can be tricky, right, because if someone doesn’t have all of the cultural or shared knowledge that you need to understand what’s happening in the video, what the stereotype is supposed to be doing, it can seen as reinforcing these stereotypes as opposed to the stereotypes being used as a way to make social commentary or undermine what these stereotypes supposedly tell us about these groups. That did happen sometimes. People are gonna interpret these videos in different ways.

Drawing on these racial stereotypes, and because of the way race functions in the US and elsewhere, touching on race also means that you’re gonna touch on gender and class and education and language and lots of other things that happen. One example that I really like – I talk about in the article – is one by King Bach called “What THEY Hear when WE Talk” I feel like it’s just a really good and clear example of how this can all come together.

[Excerpt “What THEY Hear When WE Talk”]

King Bach 1: How are you two fine gentlemen doing this evening? I was wondering if you’d like to – King Bach 2: Ay man, I – shush – I would knock yo fat ass /wəˈnɑʔ joʊ ˈfæ: ɾæ/ bruh. I came. I was like, shit. you gon gimme yo number, bruh.

[End excerpt]

In that one it’s actually fairly – I don’t wanna say “simple,” but it actually doesn’t use as many of these other resources that Vine videos often do. It’s three people standing in what looks like a parking garage, is where this happens. They’re just having a conversation.

Megan Figueroa: Can you tell us then how – I’m guessing this is very language-based – how are they using language in this Vine?

Kendra Calhoun: One of the reasons I like this one is because there’s lots of other ones where sometimes there’s no dialogue at all. It’s all very visual. That’s where things like the costumes and the props come in. In this one, it really is almost exclusively language-based and there’s a lot of embodiment that happens as well. Basically, it’s King Bach, who’s a black man, and then there’s two other white guys who are standing in this parking garage or wherever they are. They’re also actors. They’re collaborators on the Vine.

He walks up to them, extends his hand for a handshake, uses this very formal, standardized way of speaking. He’s like, “How are you two fine gentlemen doing this evening?” They shake hands. Then, there’s a perspective shift, which it’s a thing that if you aren’t familiar with Vines you might not recognize right away, but you can tell by the camera work and what happens that it’s meant to be a change in perspective. Basically, the same interaction replays, but it’s from the perspective of the white people now. King Bach is now using morphological and phonological features of African American Vernacular English, but it’s also really exaggerated. He’s really loud now. His speech is kind of slurred. There’s lots of profanity. Also, his embodiment changes. He’s flapping his limbs around really wildly.

The video, in combination with the title – so this is something interesting that King Bach does a lot is where the title tells you how you should interpret what you’re viewing. This title of “What THEY Hear When WE Talk” sets up this dichotomy of “them” being white people; “We” or “us” being black people. Essentially, he’s getting at this idea of no matter how quote-unquote “good” or “proper,” no matter how standardized your language is, no matter how, essentially, linguistically “white” you sound in an interaction, you’re still always going to be viewed through the lens of what you look like.

I can plug H. Samy Alim and Geneva Smitherman’s book “Articulate While Black” that looks at Barack Obama’s speech and this phenomenon of no matter what kind of structural power you have, you can never escape the way that people view you ethnoracially, phenotypically, linguistically – the idea basically being you are always going to be expected to speak a particular way and, even when you don’t speak that way, people still might perceive or interact with you as if you did.

At the same time that he’s doing that in second version, it switches back and forth between King Bach and the two white guys who are there with him. They’re making these expressions almost like they’re scared and confused and just can’t really figure out what’s going on. It’s the idea of him just being this indecipherable, mumbling, bumbling caricature despite the fact that in reality he is this very polished, speaking with very standardized English doing this quote-unquote “professional” interaction.

I think to contextualize the ideology or the practices that he’s trying to get at, it’s the same idea as if someone tells a black person or another person of color after a presentation or a speech like, “Oh, that was really good. You were so articulate.” It sounds like a compliment, but it’s grounded in this expectation that you wouldn’t be able to articulate yourself clearly or wouldn’t be able to express your ideas very well based on the fact that you are a black person who they then expect to speak in this African American Vernacular English which they would expect to be unintelligible or less professional.

Carrie Gillon: You used the word “phenotypically” and, just in case, what does that mean?

Kendra Calhoun: Basically, physical appearance – eye color, hair color, skin tone, physical build. I won’t get into all of the how does the phenotype relate to the social construct of race but, basically, the idea of your physical appearance and how people map that onto ethnoracial categories.

Megan Figueroa: That’s definitely something that is being used when people are announcing surprise by saying people are articulate. “I am surprised by the way that you look and that that came out of your mouth.” But then this is King Bach is telling this – what is it called? – “What THEY Hear When WE Speak” is basically saying that you’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t because there’re gonna be some people that still won’t perceive you as quote-unquote “articulate.” They’ll still see a stereotypical – or they’ll hear something different than what is actually being produced.

Kendra Calhoun: Yeah. It’s related in some ways to this phenomenon of imagined accents. I believe it was Carmen Fought who did that experiment playing the same audio clip for students but then, based on the picture or the image of the professor who was speaking, if a person phenotypically looked East Asian, they said that the person was more difficult to understand or they perceived them as having an accent. Our expectations based on people’s physical appearances can really drastically shape the way that we think that we hear them or perceive them. Then, we actually interact with them accordingly.

Megan Figueroa: Who was the audience for King Bach’s Vines?

Kendra Calhoun: It’s kind of a tricky question because I think, based on the content of the Vine, a lot of it is insider or culturally specific black humor. From that perspective you could say, “Well, black Vine viewers were his primary audience” – North American black viewers, to be more specific. I think this gets into the same question as stand-up comedians or sketch comedy where, even if that’s maybe your target audience, that’s not their only audience. As content producers, I’m sure they’re also very aware of the numbers, like who’s the largest, numerically, in terms of the population of people watching your video. Even if you’re making content that would be most relatable to black people or other people of color, that’s not necessarily the only people who are watching.

Something that was interesting with the Vine platform and phenomenon was the way that it functioned as a launching pad for a lot of people. A lot of the really popular context creators were on there – they liked Vine. They had communities there. But they were also very publicly trying to become known in the entertainment business. They wanted to be actors. They wanted to be producers. They wanted to be models or whatever it was. It was this dual function of like, oh, I get to express myself creatively but then I can also use this as a way to, essentially, gain celebrity, become famous or well-known in some way. I think that’s a – I dunno – something I’m always keeping in mind when I think about who they’re making these videos for. I think it was probably different earlier on as opposed to later, like when Vine was really just kind of picking up and it really was just this creative community platform versus once people started getting famous from it.

Carrie Gillon: Is King Bach doing anything now outside – because Vine no longer exists, right? Is he on a different platform now? Is he still doing his comedy?

Kendra Calhoun: Before he was on Vine, he had a YouTube channel where he did sketches on there. As far as I know, that’s still going on. I know he still had it after Vine shut down. He’s also been on – so Nick Cannon has a show on MTV called “Wild ‘N Out,” which has a bunch of different comedians on there. He’s been on there. He was actually a guest character on “To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before” on Netflix.

Megan Figueroa: Really?

Kendra Calhoun: Yeah. I don’t remember his name, but he plays a friend of Peter Kavinsky.

Megan Figueroa: Peter Kavinsky. [Laughter]

Kendra Calhoun: Yeah. He plays one of his friends. Which I was kinda struck by because he was like – you know they always cast people who are older for high school and college, but I was like – to me he felt noticeably older than the other characters, but that’s beside the point.

Megan Figueroa: Someone was a fan. Someone was like, “We need to have him here. I wanna meet him.”

Kendra Calhoun: I was really surprised to seem him in there. But the character that he plays in that film is pretty on-brand I feel like. [Laughter] I think he probably has an Instagram channel as well.

Carrie Gillon: All right Instagram.

Megan Figueroa: Because they have videos now too.

Kendra Calhoun: Someone told me recently that he’s on TikTok.

Carrie Gillon: That’s what I was expecting. [Laughter]

Megan Figueroa: But that’s so different, right, because that’s, what, like three times as much time as what Vine had.

Carrie Gillon: A minute.

Megan Figueroa: Oh, a minute? Oh, I thought it was like 24 seconds or something like that. Wow.

Carrie Gillon: No, a minute. You can be shorter.

Megan Figueroa: Sure. Yeah. Wow. That would be a lot of discursive features, wouldn’t it? You also talk about /jɪfs/ or /gɪfs/, or “G-I-Fs” as my mom says because she doesn’t wanna say either one. [Laughter]

Carrie Gillon: That’s hilarious.

Megan Figueroa: I’m like, “Wow. That’s the cleverest cop out I’ve heard in a while.” Can you tell us a little bit about how they’re used and how they’re doing similar things as Vine videos?

Kendra Calhoun: So, I’m Team /gɪfs/. I would say that GIFs and Vine videos I think have a lot of similarities in terms of structure – what they look like visually. Functionally, I think they’re doing slightly different things. Reaction GIFs, as I see them being used – and as different media scholars and stuff have talked about them – in order for them to be widely used, they have to be decontextualized. You might look at them and know where the original film, reality TV show, music video, wherever it originally came from, but that’s not necessarily relevant to how the GIF is used.

There’s a couple where having – more than a couple. There’s some where having that extra information makes it funnier how someone uses the GIF, but you don’t necessarily have to know that in order to use it. But I think with Vines, especially the #relatable ones – when those were really popular – people were doing this slice of life, let me show you something that happens that everyone can relate to. The titles or the captions for the videos would be “When Whatever Happens” – “When X Happens,” “When Blank Happens.” They were similar in terms of being in response to a specific situation, the way that you use reaction GIFs.

But Vines generally have some sort of plot or storyline to them. Whether it’s some sort of action that happens, you can at least say there’s a beginning, middle, end – or beginning and end. One that I think of that is just – it’s this absurdist Vine humor that existed in parallel with this very making serious social commentary Vine humor also by King Bach. If I remember correctly it’s called, “When you trip and your spaghetti falls out your pocket.” [Laughter] It’s just him. And he walks out of an elevator or something, and he trips and falls, and then a bunch of spaghetti falls out of his pocket. The last couple seconds are just him kneeling on the ground, holding this spaghetti in his hands.

If you want to turn that into a reaction gif, you could take the last couple seconds where he’s kneeling on the ground crying and holding the spaghetti. But, again, in order for that to become a reaction GIF, you’re having to decontextualize it from the rest of the video. I do think that this idea of making a whole Vine video that captures a reaction to a specific moment or interaction is definitely in dialogue with what people are doing and have been doing with reaction GIFs, if that makes sense.

Carrie Gillon: What does Vine tell us about comedy more generally, do you think?

Kendra Calhoun: I think Vine shows us that – and this isn’t a novel claim – but that comedy and that humor more broadly is always in dialogue. It’s never created in isolation. Because I think, as I talk about in the article, when you look at Vine, particularly this racial comedy, you can see this through line of stand-up comedy, of sketch comedy like Key and Peele. Now, we can see continuations of this after Vine. Things like A Black Lady Sketch Show or Astronomy Club on Netflix. All of these things, they address similar issues in slightly different ways but also just some of the conventions of the language they use, the types of characters they portray, we can really see these connections.

Vine also shows us how creative people can be working within these same genre conventions. I think when people are given different types of tools that they’ll find very unique ways to use that to meet these similar sorts of social goals. I think that’s one of the things that I just absolutely love about Vine so much was seeing all of the different ways that people could use the same tools from this platform to create such drastically different things from each other or very similar things to each other, but everyone had their own unique flavor or take on it. Then, also something that seems, on the surface, to be so structurally very different from something like stand-up comedy, when you really get into the meat of it, you really see how similar these things are. Yeah. I think Vine shows us that through line for comedy.

Megan Figueroa: You are a Vine groupie. Have you hopped over to TikTok?

Kendra Calhoun: That’s always the question that comes up. As of yet, I have not.

Megan Figueroa: Is there a reason for that?

Kendra Calhoun: Not necessarily. I mean, at first I was kind of on the like “Oh, TikTok is just trying to be the new Vine,” but like, “It’ll never be the same. It’ll never be as good.” Then, mostly it was like I don’t have time to look at TikToks.

Megan Figueroa: Watch a minute?

Kendra Calhoun: Yeah. I mean, as much as I truly loved watching Vines, it really was a time-intensive thing in order to really understand just, all of what was happening on that platform. I do see TikToks. I see them on Twitter. I see them on Instagram. I am familiar with what people are doing – the dances, the different types of memes that people create. I know that there are TikTok teens who are now famous and going all over the place.

I mean, eventually I will get over there. The more that I’m seeing I think there’s a lot of, I guess I could call it “parallel analyses” to be made. Because you could immediately identify whether something was a Vine or a TikTok, even if you hadn’t spent a lot of time on the platform. Even if you see a TikTok that’s six seconds long, you could look at that and say, “No, no. That’s a TikTok and not a Vine.” It might be an intuitive thing at first. You might not be able to pinpoint it. I think I could pinpoint it.

Carrie Gillon: You could.

Megan Figueroa: I was like, “You could!”

Kendra Calhoun: That’s something I think is really fascinating, especially thinking about particularly really young teenagers who are on TikTok right now might not have been part of the Vine phenomenon at all. But there are people who were on Vine and then went to TikTok. Now, actually, there’s a platform called “byte” that was released recently by one of the creators of Vine. People are calling it essentially Vine 2.0, but it’s the same structure of the six – I think it’s six seconds – the looping structure. A lot of people who were on Vine are on that platform now. People are already using a lot of the same popular sound effects and video effects – video structure. When it first came out, there were a lot of videos that were basically like, “This isn’t TikTok. Don’t post your TikToks here.” This adversarial relationship already, which is kind of interesting.

Megan Figueroa: It’s called byte?

Kendra Calhoun: Byte. B-Y-T-E.

Megan Figueroa: Oh, B-Y-T-E. Okay. Again, with the six second limitation – and for some Vine producers, language is really, really crucial – what can your paper tell us about language in general?

Kendra Calhoun: I think one thing that’s really telling with Vine and King Bach and also just comedy more broadly is that even when people don’t have an academic lens on language, everyone is still very acutely aware of how our language use helps us or hinders us in navigating our social worlds –the ways that other people interact with us and we interact with other people based on our language practices, right. Because this “Why THEY Hear When WE Talk” is based in the reality that people have expectations of black people based on how we speak that black people style shift, and code switch, and are able to speak multiple varieties, but people don’t always necessarily recognize that.

I think that, broadly speaking, it shows us that, I mean, language as a way that people – I guess as a proxy for race and all these other social characteristics that people can use to discriminate against each other – but also particularly through the lens of comedy that language becomes a tool for bringing attention to these social problems and social phenomena and language as a tool for combatting them or undermining them. I think that’s also a common thread through things like Patriot Act and Last Week Tonight and all these different comedians is they’re using their linguistic repertoires, whatever that looks like, in order to share stories and make commentary about things that happened to them and other people but also talk about what can we do about that. What does it look like to change the situation? How do we imagine a society or an interaction that goes differently? A lot of that is through language and embodiment and all these other things that go with it.

I think, especially through humor – and I’ve seen this in teaching and just in conversation – is that because, especially in the US, race and racism is such a touchy topic that people either don’t want to talk about or are afraid to talk about because they feel like they’ll say the wrong thing and they don’t wanna come off as being racist, or being called racist, and all of that that goes with it. I feel like humor helps to take the edge off a little bit. If someone can bring attention to something you said but frame it as a joke of like, “Oh, haha! Next time, maybe don’t use that word” or “Be careful about the way that you frame that” or “Oh, actually there’s a history to this word and that makes it kind of problematic.” It feels less like I’m directly targeting you as an individual who did this thing and more so like, “I’m making general commentary about this word or this way of interacting with each other.”

I think, particularly in more intimate or close interpersonal relationships where that can get really tricky, being able to point to someone else’s comedy bit or sketch and say, “Hey, maybe watch this couple of minutes of comedy and maybe you’ll have a better understanding of why that’s not a good thing to do” or how we can go about changing our behaviors. I think a lot of times comedians – sometimes subtly sometimes not so subtly – really are making suggestions for, how do we change our behaviors? How can we be more cognisant of the way that we interact with people?

A lot of stand-up comedy, and Vines too, are not imaginary but they’re imagining or they’re constructing these situations that might not have happened or replaying how I would’ve liked something to go if I had a better answer at the moment or could think on my feet at the time. I think that is this really interesting creative practice of reimagining our social worlds and what they could look like. That’s one reason I personally really love comedy and other forms of humor.

Carrie Gillon: I like the point that you made earlier, Kendra, about how maybe it’s a way for people to see what they’re actually doing in a softer way. Like, “Haha! Isn’t this a funny thing?” And then you think about it, and you think, “Oh, man. Maybe I’ve done that. Maybe I should stop doing that.” You don’t feel so directly attacked, which we know people are sensitive. It's actually a really smart strategy for anti-racism or anti-whatever-ism. I think obviously maybe this should be obvious to us, but I don’t think it always is obvious to us what humor is actually doing because we’re just laughing in the moment.

Megan Figueroa: That is the humor I gravitate towards too. Like Last Week Tonight, I watch things like that all the time. Do you think that social media can tell us something similar or can function similarly as humor does?

Kendra Calhoun: Especially as far as the platforms that I’m on a lot – so Twitter and Instagram are my big two right now – I think Twitter in particular is a really good example of how social media can have these similar sorts of functions, especially thinking about how much of social media discourse is meant to be humorous in some way or another. Thinking about something like Twitter and just the number of videos and GIFs and memes that people post – visual memes, textual memes – but how much of that, especially in a moment like this, is tied to or based around social issues, political issues.

Corona virus has already been turned into a meme. People are using it as a way to spread information. Whereas, I’ve seen some people call it “crowd shaming,” saying, “You know, if you go out to that bar, Miss Rona’s gonna be at the bar too, and Miss Rona’s gonna come home with you,” using it as a way of pointing out this is – we can use humor to make very important points of this is serious. You shouldn’t be going out to bars. You could contract Corona virus and take it home and infect other people. People doing that with political figures. People doing that with police officers. There’s always something happening in the news.

I’m thinking more specifically of black Twitter and how it’s, again, this long-standing tradition of using humor to bring attention to these social issues. As I said, a laugh to keep from crying kind of practice. I think another thing with social media, even regardless of whether or not what someone’s posting is humorous, is a lot of times social media is where people turn to find community, to find resources, to access people and information they might not otherwise connect to in their day-to-day life. They might not be able to turn to their family or their neighbors or the people who are immediately around them.

From what I’ve seen and what people have studied, people will share a lot on social media, particularly if it’s anonymous. I think it offers this window into seeing what people are really dealing with in their day-to-day lives. Sometimes, it’s more just a thing of “Here’s a thing that happened to me,” but also sometimes talking about how they combatted experiences of discrimination or talking about the resources that they need to get through the issues that they’re facing. I think someone who’s on social media a lot is absorbing that, but you can also do it strategically of getting on a social media platform and scrolling through or searching for specific key terms and seeing what people are talking about and learning in that way.

Yeah. I think it has some similar social functions in that way of sharing information and doing so in a way that points to larger structural issues as well as more localized and individual experiences.

Megan Figueroa: I like that idea of cultivating empathy. This is what we have access to more people’s lives in this way that they’re willing to share. It can help us cultivate empathy for other people.

Carrie Gillon: I definitely think it works. I mean, obviously, there are people one there who are just not going to give two shits about anybody else, but I have definitely seen people change their minds about things because they’re like, “Oh, wait. This is really happening.” The first time I saw someone talk about it on Twitter, I didn’t believe it. The 10th time I saw it, I was like, “Oh, this is real.” I’ve seen it with sexual assault. I’ve seen it with violence against black people. I’ve seen people actually change their minds. It’s helped me. I have learned some things that I would not have known otherwise without Twitter in particular, less so other social media.

Kendra Calhoun: I know for me being on Twitter – I started following a lot of disability activists. Even within linguistics Twitter, I’m following more people who do deaf studies and sign languages and thinking about issues of accessibility. For me, just thinking about in my day-to-day life, in my teaching, the language that I’m using, but also how am I structuring my lessons? Am I including sign languages? Am I including non-Indo-European languages? Just making me think reflexively and critically about my own social practices.

Even if I didn’t doubt that ableism and things like that existed, really seeing it put into concrete terms and seeing how I could be participating in that in my own day-to-day life that I didn’t realize and opening my eyes to changes that I can make and, as I was saying before, not feeling like I’m being attacked as an individual but saying, “Oh, people are talking about this because it’s a common thing.” That means me and a bunch of other people have some changes that we need to make and how can I start doing this on an individual level.

Megan Figueroa: Do you have one last message for our listeners?

Kendra Calhoun: I dunno. I guess, now that we’re all hopefully doing some social distancing, I guess my message would be to watch some good comedy. See if you feel like it’s hegemonic or anti-hegemonic, why you feel that way. Think about what’s the takeaway message from that. Is it something that you can adopt in your own life? Have you learned something new from watching this comedy? I guess that’s something that my students always tell me because I always incorporate comedy and social media and all this stuff in my teaching and they’re like, “This is really cool that we can apply this to what we see in our everyday lives. Now, we can’t unsee it. I can’t just watch comedy anymore.”

Carrie Gillon: Right. We’ve talked about this before how, once you know something, it’s really hard to just watch a movie. You’re just like, “Oh. What message is this giving me?”

Kendra Calhoun: I think comedy’s one of those things where even while you’re aware that there is or might be this important socio-political message, you can still enjoy it. It always fluctuates, right? It’s not like 40 minutes straight of really intense social commentary. It switches between being really lighthearted, sometimes being absurdist, sometimes it’s crass, but in the end a lot of times you get a really good takeaway message.

Carrie Gillon: Thank you so much! This was a really fun conversation.

Kendra Calhoun: Yeah. Thank you. I really enjoyed it.

Carrie Gillon: I didn’t start coughing.

Megan Figueroa: I know! You suppressed it for an hour. It’s great. Wait another four hours.

Carrie Gillon: Oh, god. Anyway, let’s all tell our listeners – don’t be assholes!

Megan Figueroa: Don’t be an asshole. Stay healthy, while not being an asshole.

Kendra Calhoun: Stay healthy!

Megan Figueroa: Thank you, Kendra.

Kendra Calhoun: Thank you.

[Music]

Carrie Gillon: We would like to thank two new patrons for this month.

Megan Figueroa: Yay!

Carrie Gillon: Daniel Greeson.

Megan Figueroa: Thank you, Daniel.

Carrie Gillon: And Duncan Wane.

Megan Figueroa: Duncan, thank you. Two Ds.

Carrie Gillon: Two Ds, yes.

Megan Figueroa: Duncan and Daniel.