#her entire character is trying to be her unapologetic self without the authority of her abuser😭

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Red has a higher rank than Chloe😭 Her villainy was less than a minute. I'm crying??

#girl did one thing and decided to go back in time#like i get 'omg she's so bad she steals and vandalizes' but they made her mom be a tyrant that abuses her#her entire character is trying to be her unapologetic self without the authority of her abuser😭#honestly if they gave chloe the 'the villain' role it would make more sense to me#considering how she believes black and white thinking#with red she knows it's more complicated than that#i dont even think she can be classified as a villain???#Glassheart#princess red#choe charming#ella accidentally threw red under the bus with her mother right there#she was already supposed to be punished but was interrupted by mads and honestly do you think Bridget would let it happen a second time?

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

The main theme of Stranger Things is summed up by Eddie: “Forced conformity, that’s what’s killing kids.” The central characters of Stranger Things are outcasts of society. They’re either poor, queer, black, “soft” men, unapologetic women, weird, crazy, or a mix of these undesirable traits.

The Byers and Nancy embody this explicitly enough for the general audience to understand every season. Jonathon and Will are pretty self explanatory. Joyce is always the social pariah of the town and her dynamic with Police Chief Jim Hopper the “Everyman” is draining at times. It’s draining because Joyce is right and we know she’s right but the rules, the laws, and “common sense” which Hopper is meant to represent, say otherwise. And every season Hopper’s resistance is broken down and he works with Joyce. If he doesn’t work WITH Joyce he nearly dies. If he doesn’t believe her at all, bodies start dropping. You have to go “behind the curtain” and accept the weird to survive or make progress as a general narrative rule, the entire show.

With Nancy, her motivations are justice (which the world is not ready for) and rebelling against the perfectly structured boxes society has put in place. These two go hand in hand, she can’t get justice because people don’t want a disruption to their neatly structured lives. Working around the common people is a nuisance for her. She talks often with Jonathon about how she can’t conform to the lifestyle her parents do (implied racist + homophobic without actually having to say/show it explicitly in the show through the support of Regan and Karen’s Thatcher convo) how the cookie cutter lives with reality shuttered out would kill her.

With Lucas in s4, he is trying to save himself from being othered by conforming in the most palatable way he can without sacrificing his own happiness. Him trying to be “better” isn’t framed as bad thing (which is how the audience seems to be taking it for some reason), it’s framed as a hopeless endeavor because it’s never going to be enough. Even if he’s not being targeted at the moment, people he loves are and regardless of what he does it’ll circle back to him eventually.

Eddie is the “worst of society”. He’s a poor good for nothing loud mouthed idiot, obnoxious, disrespectful to authority, crazy drug dealer, and gay (implied). But he’s idolized by Mike + Dustin and the narrative makes him very human and kind. He’s also the only one that gives any relief to Chrissy who is literally cracking under the pressure of acting normal. No one except Eddie and Max notice or says she’s acting weird, no one except Eddie and the counselor try to help her, and Eddie is the only one to make her feel even the slightest bit better. And the reaction to her cracking from her peers is to blame the crazy person instead of admitting she wasn’t perfect which is framed as a ridiculous and violent cult mentality.

This is all to say that every character we are meant to like is a social reject and have a sense of solidarity with other social pariahs… meaning that none of the central characters or “heroes” of Stranger Things are gonna be purposefully or blatantly homophobic or racist. It is the 80s (minorities still existed btw) but it is also a FICTIONAL show. They dropped the ball using a slur towards indigenous people of the arctic, but before that racism and homophobia were punished by the narrative.

Billy was racist. It’s not up for debate. He was racist, among other things, and he was punished dearly for it. The bullies are punished for being racist and homophobic and then never seen or mentioned again. Is that realistic? Nope, but they’re not important after they’ve been punished. The one character we’re meant to like that has been homophobic was immediately beaten up for it and after development has an arc accepting a queer woman.

Steve went from a perfect stereotypical jock and bully unhappy with his life and relationships, to a happy loser working in a video store with a weird kid and a lesbian for best friends. When he gave up trying to fit a mold, he became a better person and his life became infinitely better and he is consistently told how great it is that he’s changed. We don’t ever see his parents reactions or his old friends after he ditches them because their opinions don’t matter. We only see the praise he’s gotten and the fact he’s happier. Is that realistic? No. But it’s the narrative being made.

You know what is realistic though? A tight knit friend group that grew up being ostracized and bullied, witnessing their friend they’re devoted to being bullied for maybe being gay. Even more realistic is that the gay kid is still loved by those friends regardless of whether the bullies had some truth to their taunts. These kids are genuinely hated by most people and only have each other to depend on, every issue they’ve had they’ve gotten over. They apologize to each other ALL the time and they all have a surprising amount of emotional intelligence (yes even Mike, he’s a dick because of trauma + internalized homophobia and he’s aware he’s being a dick and takes responsibility for it when it’s not jeopardizing what he’s feeling is his safety).

In conclusion, none of the characters are going to be homophobic, sorry to ruin your fantasies. It’s unrealistic, out of character, and goes against the core themes of friendship and unconformity set up in the show.

#stranger things#lucas sinclair#nancy wheeler#byler#steve harrington#will byers#mike wheeler#dustin henderson#robin buckley#joyce byers#jim hopper#eddie munson#i wrote this at 3am this morning don’t judge to harshly lmao#long post

396 notes

·

View notes

Text

Afrofuturism in the work of Janelle Monáe

Ashley Clarke, a curator for the Brooklyn Academy of Music, defined Afrofuturism as “the centering of the international black experience in alternate and imagined realities, whether fiction or documentary; past or present; science fiction or straight drama.”

Themes of Afrofuturism can be found throughout the works of Janelle Monáe. Her previous albums like The ArchAndroid and The Electric Lady showcase this through the exploration of androids as a new “other.” Today I want to talk about one of her most recent projects, Dirty Computer, and the way it contributes to the conversation on Afrofuturism. Janelle Monáe released Dirty Computer as an album and a 48 minute long Emotion Picture to draw her audience into a visual and auditory world of her own making. The dystopian future she presents to us is very similar to our own current reality, except that the voices being amplified are those that have historically been silenced. People of color and the LGBT+ community are central in this story rather than pushed off screen. Dirty Computer is so powerful because it focuses on joyful rebellion, love, and freedom in an oppressive dystopian setting.

The project, as Monáe has shared, can be split into three parts: Reckoning, Celebration, and Reclamation.

Part I: Reckoning

gif credit: scificinema

gif credit: scificinema

The Emotion Picture begins with Monáe’s character Jane 57821 laying out how her society has begun to capture people deemed dirty in order to “clean” them of their supposed filth against their will. This is meant to produce beings that are stripped of all individuality and ready to conform to societal norms and expectations. Jane tells the audience that, “You were dirty if you looked different, you were dirty if you refused to live the way they dictated, you were dirty if you showed any form of opposition at all. And if you were dirty it was only a matter of time.” The dichotomy between dirty and clean has created a system where an entire class of people can be demonized and oppressed. This foreboding tone at the beginning prepares the viewer for the grim implications of the cleaning process in this universe.

Dirty Computers are strapped to a table and forced to undergo the “Nevermind” which is a program that deletes memories. It is a process that is horrifying because of what it symbolizes to the individual and entire communities of people. To erase someone’s memories is to erase who a person is. The character of Mary Apple 53, Jane’s love interest, shows us just how alien a person can become once their memories are gone. The horror of erasure is also something that marginalized communities have faced for centuries and continue to face today.

In an interview on Dirty Computer, Janelle Monáe said “I felt a deeper responsibility to telling my story before it was erased. I think that there’s an erasure - of us, and if we don’t tell our stories they won’t get told. If we don’t show us we won’t get shown.” Afrofuturism is a response to this erasure of black people and people of color in culture, history, and art. Monáe has made a deliberate choice to tell her story even if it might get erased because if she doesn’t do it then no one else will. Remaining silent would be to assist in that erasure and Afrofuturism is all about refusing to be erased.

This first part of the Emotion Picture is all a reckoning with the Dirty Computers and how they are pushed to the margins. The lyrics in Crazy, Classic, Life speak about how the same mistake made by two people on different ends of the spectrum of social acceptability is punished unequally. Take A Byte follows it with a more upbeat tone, but even then the lyric “I’m not the kind of girl you take home to your mama” speaks to a feeling of being outside social norms.

There are moments of light and joy that are counterweights to the dire situation Jane is in. These come in the form of her memories which are played one final time before they are erased. Jane’s life before she was captured was filled with exploration, youth, love and celebration.

Part II: Celebration

Gif credit: normreedus

Gif credit: daisyjazzridley

Gif credit: nerd4music

Dirty Computers seem to recognize that they are living on borrowed time and that any day could be the day they are forcefully disappeared. This is why they fill each moment with as much fun, life, color, and joy as they can. There are many scenes at clandestine parties where Dirty Computers live freely and openly despite the threat of drones or police that could capture them at any moment. It is important to have these scenes of celebration though because Afrofuturism is also about providing hope.

The future must be a hopeful one if we are to strive for it and Afrofuturism allows us to be creative in crafting our visions of a hopeful future. Even though Monáe’s future is dystopian, there is still room for hope and joy because those are the things that make life worth living. These Dirty Computers have to live their lives joyfully because they don’t know when they’ll be sterilized.

In the interview mentioned previously, Monáe added that “I had to make a decision with who I was comfortable pissing off and who I wanted to celebrate. And I chose who I wanted to celebrate, and that was the Dirty Computers.” The LGBT+ community, people of color, black women, immigrants, and low income people have all been mentioned as people Monáe wished to celebrate. This celebration comes intertwined with images and themes of rebellion as expressed in Jane’s memories. Screwed, Django Jane, Pynk, Make me Feel, and I Like That are the songs that embody celebration the best. Whether it's a celebration of sexuality, femininity, unity, or of self love it is all encompassed in these songs. Jane is shown connecting with others and being unapologetically proud of herself. We also see her falling in love with two people, Zen and Ché, and we see them love her in return.

Gif credit: thelovelylights

Viewing these memories and interacting with Jane seems to encourage the questioning of authority. The employee utilizing the Nevermind process seems to question why he should be deleting Jane’s memories at all. Mary Apple 53, previously named Zen, also directly questions their matriarch after speaking with Jane and realizing that she’s connected to her. It all culminates in a nonviolent escape attempt where Jane, Zen, and Ché reclaim their names, bodies, and their lives.

Part III: Reclamation

Gif credit: thelovelylights

The Emotion Picture ends with Jane 57821 and Mary Apple 53 freeing themselves, and their recently arrived lover Ché, from the facility. They escape without harming others the way they themselves have been harmed. By leaving they are reclaiming their freedom and their right to be proud of being Dirty Computers. They refuse the new names that were forced upon them and leave to rediscover the memories of the life they lived before capture.

It is a hopeful ending that plays into the themes of Afrofuturism. Even though both Jane and Zen’s memories were erased they still have the ability to create new memories and stories. Their ability to recreate their past as well as create a new future was not taken away. As they escape the song Americans can be heard in the background. The lyrics subvert the typical American patriotism expressed by racist white southerners. The trope of preserving gender roles and being a gun carrying american are satirized in these lyrics. America as a whole is being reclaimed by Janelle as a place for the people who have been marginalized.

Janelle sings “Don’t try to take my country/ I will defend my land/ I’m not crazy baby/ nah I’m American.” This sentiment is typically espoused by xenophobic americans, but when it is sung by Janelle she is saying that she won’t be forced out of America due to the bigoted beliefs of the people who hate her. She also pleads for the listener to love her for who she is which is something that has been denied to black women for centuries. The song ends with a powerful message of reclaiming America by Rev. Dr. Sean McMillan who said “Until Latinos and Latinas don't have to run from walls/ This is not my America/ But I tell you today that the devil is a liar/ Because it's gon' be my America before it's all over.”

This also shows themes of Afrofuturism since Monáe is reclaiming her history and is refusing to be excluded from it. She is asserting her presence and that of all the Dirty Computers by saying that they too have a claim to America. The Emotion Picture and the album are both a masterpiece of Afrofuturism art and music. Monáe masterfully weaves various musical genres and visual storytelling to show her pride in being a black queer woman. There is no other artist like Janelle Monáe, and I am excited to see what new worlds she will take us to next.

#janelle monae#dirty computer#afrofuturism#dirty computer emotion picture#blog post#space is the place#analysis#media analysis

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

possibly underappreciated Good Omens fics I enjoyed once upon a time

Indirectly inspired by a video series about fanfiction I watched, I decided to pull together a list of Good Omens fics I have bookmarked as stories I enjoyed, but which have less than 250-300 kudos at the time I’m writing this. No particular order. They’re accompanied by short excerpts from my private fic reading notes (not originally intended to be read by anyone but me, mind), sometimes slightly edited for clarity—and, sometimes, the comments I left on the fics.

This list sat in my drafts for a long time and the recent S2 announcement reminded me of it. I’d love it if it inspired you to do something similar! Spread the love.

And mind the tags, please.

△ = general and teen ▲ = mature and explicit

thermodynamic equilibrium ▲ 7K the author has such an ear for dialogue and is unapologetic about what they want to write the characters like. They think of the characters as a mix of TV and book canon, but they feel like a homemade blend to me. (...) It’s very funny.

such dear follies ▲ 6K I can really picture this Aziraphale—Crowley as well, but her especially. She’s rather distinct. (...) Nice writing.

The Words Were With - △ 1.2K post-Blitz vignette, Aziraphale realizes what he feels and wonders if they're human enough for this. I liked it, and I liked the tag "transhumanism, but in reverse?", too—what an interesting idea. I'd say it's a vignette in a dire need of a follow-up, but, well, there's the show. The show is the follow-up. It fits very nicely within the canon and I totally believe it could have happened, like a deleted scene.

Gossip and Good Counsel △ 19K/? I love their companionship and how they're set up to be opposites by the management even though they get on pretty well. It feels very in keeping with the canon, but I feel like the fact that it's an F/F set in this particular time period adds a meaningful layer to the situation. It's women supporting each other in the world of men, working with the personas that are created for them, but, privately, being normal, well-rounded people. (...) and of course your writing is always a pleasure to read. (...) SDHDGDHDHDG Maisie is truly an Aziraphale.

Crowley Went Down to Georgia (he was looking for a soul to steal) △ 6K This was nice. Based on a song I didn’t know. Crowley goes to a funeral in the USA, one of a fiddler he knew and lost a bet to once. (...) The fic has not one but two songs composed for it and embedded inside it and that makes it even better. I really enjoyed the experience.

The Thing With Feathers △ 18K WARLOCK you'rE HORRIBLE AND I LOVE IT I would read an entire novel-length fic just of Crowley fighting his battles with Warlock. Written like this? It would be a blast. (...) The OCs are believably characterized and well-loved by the story. (...) Everyone seems to need a friend in this house. (...) This was so fun, and at the same time, their mission has weight here (...) We wonder about what the future holds even though we know it.

Here Quiet Find △ 11K This fic aimed for my head and the aim was sure precise. It was a story of Crowley sensing Aziraphale's distress and finding him in a self-quarantined English village in the seventeenth century, tired and anxious. It's hurt/comfort, so there was washing and bedsharing and I had to love it, so I did.

outside of time △ 2K Post-Almostgeddon, (...) nicely-written, short, but strung with a soft kind of tension and unspoken words. There's no drama, just "can we really", and "do you really" of sudden freedom. They fall into being inseparable. Book canon, which I like for this story (sitting on a tarmac). I liked the footnotes. There's a mention of Eliot. All in all, very much yes.

She'asani Yisrael △ 2K It’s Crowley going through a two-hour service and drinking blessed wine. He also keeps an eye on a boy he was asked to. It’s 1946. It was pretty good, so far the best Jewish GO fic, I think, from the ones I’ve read.

To Guard The Eastern Gate △ 11K I loved it. You really made Sodom feel lived-in; the description of Keret, Hurriya and Yassib's house and relationship were great. I got attached to both them and the city (...) Aziraphale and Crawley’s interactions were generally very entertaining. I laughed (...) Your rendering of their voices just lands so well (...) But then oh, the entire ending (...) hurt, hurt a lot, and your descriptions are so vivid.

If you’ve been waiting (for falling in love) △ 14K AAAAA a good ending line. The whole paragraph, in fact. I love a good smattering of philosophy in my fics, and this was really nice. I can get behind Thomas Aequinus's and Crowley's view on eternity. It's (...) a pretty simple fic (...) - the courage to express yourself and take a risk is awarded with winning what was at stake by the virtue of reciprocity - but the way it was intertwined with a study of how they would experience a forever was done well.

Holy unnecessary ▲ 2.2K It's well-written. (...) this is my type of sexual humour if I have any. So subtle. Blink and you'll miss it. Lovely.

The Parting Glass △ 17K Through the ages, they're dancing around their relationship until after the Armageddoff. (...) Wow, this was really, really nice. Very simple in its concept and nothing I haven't read before, but very well-executed. (...) AAAAH I LOVED the first chapter. I always like abbeys as settings, that's a given, but the banter, the good writing, the moral ambiguity!

Name The Sky △ 33K This Crowley is different, but very intriguing. Without his sarcastic talk, and much more animalistic. (...) I love how expressive Crowley is. (...) This fic has a very nice balance of drama and levity. I don't love Crowley-before-the-Fall stories very much, but with this execution I can read about it. (...) Okay I've read Crowley offering fruits, and even Aziraphale biting fruits, but the two of them sharing the apple? Outstanding. Ingenious. What a take.

A Flame in Your Heart △ 5K post-Blitz (why are so many dance fics post-Blitz?), they go to the bookshop and have an actually believable conversation. Then they dance the gavotte. It was really nice! Believable writing, emotions, the dancing! (...) Of course it's too early for them, (...) but the author's note? yeah.

Put down the apple, Adam, and come away with me ▲ 32K At this point it's just reading original stories with characters with names and some personality traits that I recognize. (...) I really enjoy this, the careful dance, the opposition between their views. (...) This is well-written, wow. (...) it's not an easy read (...) this story feels very believably 50s, but also reaches out to the present time.

Liebestraum ▲ 10K/? It really is like music. I'm enjoying the writing a lot. (...) oh my actual god. This, this? Wow, uh. This came for my throat. (...) THE MUSICAL COMPOSITION, THE MOTIF RETURNING, THE AUTHOR KNOWS WHERE IT'S AT (...) Excellent. This hits the right beats so precisely, (...) and with feeling, too.

Down Comforter △ 2.4K and they lay down in angeldown, a soft rug ‘neath their heads– alright. Well, Crowley lies under Aziraphale's wing on a Persian rug after the Apocalypse, and they talk (...). It was sweet.

The Corsair of Carcosa △ 5K Crowley wakes up from a nap, visits Aziraphale for some drinking, and they read The King in Yellow that he happens to own. Good writing, so I'm bought. Aziraphale mentions Beardsley, so I'm bought twice over. My god, a discussion of etheral/occult madness? Caused by some wrong/true reading? Yes.

Very Good, Omens! △ 6K It's rather well-written, well-pastiched. People don't do that too often, nowadays - try to write in the style of a particular writer. (...) I love wordplay like this.

Reviving Robin Hood: The Complicated Process of Crème Brûlée △ 30K it's well-written (...), has a rhythm to it, and quiet humour. (...) Finally some nice, good, light writing. The attention to detail! (...) I'm still reading most of it aloud, the rhythm of it compels me to. (...) okay this does sound like Pratchett&Gaiman, the Good Omens itself (...) The fic is meandering, hilarious, sensitive in all the right places, and overall lovely.

my dear acquaintance △ 1K Oh. Oh. Yes, yes! Aziraphale in Russia, Russia I've never been in, but I can feel the snow and the evening of. Very real, and the bar, too. Attention to detail - vodka flavoured with dill, what on earth? Yes. He would totally have a distinct taste in operas and he would totally complain about a subpar one. I'm glad Tchaikovsky's there.

there is a crack in everything △ 1.8K This was good! Ah. Inspired by a comment (...), I went looking for Mr. Harrison and Mr. Cortese fics—really, what a big brain moment someone had and why have I never thought to look for them? This is Crowley getting suddenly anxious and Aziraphale going out of his way, through all his layers of not-thinking and denial, to console him. I also really liked how the Arrangement is a carefully unacknowledged partnership-marriage.

Scales And Gold And Wings And Scars △ 6K No conflict, no plot, one tiny arc like a ripple on the surface of water on a calm sunny day - of Aziraphale discovering Crowley’s scars. It's the South Downs and it's early summer. They bask and swim in a spring. Non-sexual nudity, love in the air like a scent. Nice.

Nineteen Footnotes In Search Of A Story △ 0.4K This is a Good Omens story told only through footnotes. Your mind can fill in the gaps. Fascinating (...). Also, it’s an experiment so apt for this particular fandom.

Hell on Earth △ 6.5K Oh, I loved it! How could I not love it: it's Beelzebub-centric, it's historical, it has classical painting, and even a hilarious scene with a cuneiform phrase, as if I didn't enjoy this story enough already. There are so few Beelzebub fics out there and I find searching for them very difficult (I accept recs if anyone has any), and it's such a shame, so this was really like a gift to the fandom. I absolutely adore the way you portrayed them, small, frightening, powerful, and confident. Also, it was super fun to see how different Crowley seems when we're not in his POV or in a story about him and Aziraphale. (...)

Go Up to Ramoth-Gilead and Triumph △ 24K Daegaer is... pure class. (...) hdhdhdh what pfttt why you so funny (...) I love this Crowley. (...) This got unexpectedly intense. (...) I love the little nods to the fact that Israelites, especially the poorer ones, still believe in other gods. I also really like that they sleep on roofs. It's just the kind of detail that grounds the story and shows that the author is, in fact, a historian.

#good omens#good omens fic rec#fanfiction#fic rec#idanit reads#i also have a multifannish F/F rec list in the works#all my bookmarks are private but i feel the need to share the love

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo

Author: Taylor Jenkins Reid

Genre: Historical fiction, Romance

When Monique is given a career changing opportunity to write biography of the very famous Evelyn Hugo, she was both surprised and delighted. But as she digs deep into her life there are some truth revealed that might not what Monique had ever imagined. So, what is the life of Hollywood Star Evelyn Hugo and how is Monique's life changed? Read the book to find out...

My thoughts: -

This book is charming, witty, and glamorous. It has every element that makes a book hit among the audience. And it is a big hit. I loved how complex the characters were especially Evelyn and how tragic and devastating the story was. All of this made the book a very interesting read. Oddly even though this book had everything, it felt underwhelming to me. It can be because it was made so perfect that it just felt too perfect to me (I hope it makes sense to y’all).

Plot: -

“Heartbreak is a loss. Divorce is a piece of paper.”

The plot is so thick with drama, you’ll just want to complete the whole book in one go. I liked how there was a transition in the story between Elevyn and Monique’s life. I also liked the concept of adding clippings of newspaper articles in between the story. It shows the audience of how the entire world had eyes on every movement of Evelyn, it gives a good effect to the book.

With the title of the book, I first thought that the Evelyn’s husbands will make a big part of the book, but as the plot continues you’ll quickly realise that it is not the truth. This story is about two women who are dealing with life while trying to make their dream come true. With Evelyn, you see her story divided in seven chapters according to her husbands, where we see her achieving her dreams, while her husbands just become the part and parcel of her life. With Monique, you’ll see how with every chapter she grows and decides to live a life on her own terms, to live a life freely. I enjoyed watching these characters grow.

Characters: -

“I’m bisexual. Don’t ignore the half of me so you can fit me into a box, Monique. Don’t do that.”

Evelyn Hugo is one of the best morally grey characters out there. Her drive and passion to be a successful actress, her love for her partner and friends and the way she stands up for herself makes her a very strong character. What I like about her is that she is unapologetically herself and makes no excuses for her actions, even the wrong ones. This is a very rare quality to find and that’s what makes her unique.

“I have to ask and be willing to be told no. I have to know my worth.”

I really wished we could have had more of Monique in the book. With high drama revolving around Evelyn, you will see quite less of Monique throughout the whole book. Despite of less appearance, she makes a good character to read. She is strong, knows what she wants and learns during this book to get what she wants. In this book, you will see her find her self worth and also herself.

Talking about other characters, I absolutely loved Harry, he is such a gem of a person. No wonder Evelyn called him her best friend. Because throughout the story you can see he is literally the best and the kindest character in the books. Celia was also one of the really good, strong female characters. One thing that I disliked about her was that she was really whiny. That’s all I can say without giving spoilers.

So, to wrap this up, I would say that this book would definitely be a good collection in your TBR. Especially if you want to see the drama of having a LGBT affair in the 60’s.

#the seven husbands of evelyn hugo#evelyn hugo#monique grant#celia st james#harry cameron#taylor jenkins reid#book review#booklr

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Get to know the author

Got tagged by @unfocused-notwriter AGES ago~ (thank you!!)

I’ll tag @breakeven2007, @elliewritesstories, and @amerraka, but only if you want to do this along with anyone else if you’d like~!

1. Is there a story you’re holding off on writing for some reason? I have a strong urge to write sci-fi someday, but I'm waiting to finish Mercy. It would be difficult to work on two complicated stories at once. 2. What work of yours, if any, are you embarrassed about existing? Probably this short story I wrote for a stupid creative writing class about a spiteful guy named "Dusty Wolf"... That explains a lot, doesn't it? 3. What order do you write in? Front of book to back? Chronological? Favorite scenes first? Something else? Front to back. I've attempted to write out of order and have also started from the ending-forward, but these do not work for me. If the beginning isn't solid, I can't move on for some reason. 4. Favorite character you’ve written? It's a tie between Joey and Edith. They're both fun to write because they have such bold, colorful personalities, and I'm introverted. They give me the chance to speak whatever comes to mind without holding back no matter how mean or inappropriate. 5. Character you were most surprised to end up writing? Rowan, because I actually hate her? Jessyka! She's got the most shocking motives and is relentless and unapologetic for the messed up things she does. In general, there's a lot to explore through her, even though she's not like the characters I normally write at all. 6. Something you would go back and change in your writing that it’s too late/complicated to change now? The origin story with the Creator. Originally, there wasn't an origin story at all and everything in Mercy just existed without a higher entity (besides angels and demons, but they didn't have a purpose) so I came up with a Goddess to balance out the emptiness and also provide a rational for everything that happens. I'll just say that there's a lot of simplifying that needs to be done, but its a lot to fix. 7. When asked, are you embarrassed or enthusiastic to tell people that you write? I'm enthusiastic until they ask me what I'm working on or if the questions "will you write this for me/will you add me in as a character" comes up. 8. Favorite genre to write? I've always been comfortable with fantasy, but I really want to write sci-fi and I wouldn't mind exploring horror (It just sounds difficult to create fear through words for some reason. Kudos to horror writers.) 9. What, if anything, do you do for inspiration? Listening to music, reading a book, watching a movie, watching an anime, talking to a friend, reading over old ideas, Ted-Talks/inspiration videos in general, and if possible going outside (whether it be going to the store or walking around) all help me get inspired. 10. Write in silence or with background music? Alone or with others? I always listen to music if possible, usually one song on loop. I normally write alone, but I don't mind being around others. Having company is comforting, but I don't write around my friends often enough to be affected. (I MISS THEM A LOT THOUGH :””^>) 11. What aspect of your writing do you think has most improved since you started writing? The character development has grown a lot, so its not writing with my characters is not like puppetry anymore. Also, the plot is driven by character actions and motives which was really hard to plan out, but worth it. 12. Your weaknesses as an author? Descriptions (especially with setting) and actually writing. I get stuck on opening easily, so I still have to learn how to move on and finish my drafts instead of starting over because of one sentence. 13. Your strengths as an author? I think I have succeeded with character creation and depth. I'm extremely attached to my children and I hope readers will feel the same way someday. They don't feel fictional to me, they are actual people. I love them a lot :^) 14. Do you make playlists for your work? I try to. The longest playlist I have for Mercy only has 10 songs on it and their more like...character theme songs if they were to have them. I have a huge playlist of my favorite songs that I listen through when I write, but I guess that isn't made for just writing so.... 15. When did you start writing? In third grade, we had a project to write a story in class, and I really liked the feeling of making something up as I sat in the coatroom. I also made a Deviantart in that same year and I started RP-ing before I got banned for being under-aged but that's where I really kicked off. (Around fourth or fifth grade, I made the initial premise for Mercy) 16. Are there characters that haunt you? Rowan. I'm just gonna name the ones I remember: Lyra, Haru, Kavanaugh, Avery, Iren, Zaire & Lucas, and Wisteria. 17. If you could give your fledgling author self any advice, what would it be? Keep. The. Beginning. Keep. Writing. Its. FINE.

and don’t feel bad for saying no to people when they ask to be/make characters for your story. 18. Were there any works you read that affected you so much that it influenced your writing style? What were they? No books off the top of my head, but anime wise, Cowboy Bebop has become a standard/major influence for me. I love the story line and the character and the theme behind the entire show. And the soundtrack is pure gold. 19. When it comes to more complicated narratives, how do you keep track of outlines, characters, development, timeline, etc? I just write everything down in writing notebooks or on new documents or whatever. Sometimes I can keep an idea in my head. Everything random and unorganized to be honest. I really should consider fixing that, but I don't have time. :"} 20. Do you write in long sit-down sessions or in little spurts? Both! Sometimes I can get into a deep writing kick for a few hours, and other times I write more within a 15 minute break. Just depends on my mood and if there are things stealing my attention. 21. What do you think when you read over your older work? Either "This is actually trash. Why did I write this? I'm so glad I've improved from this." Or "WHAT THE HECK THIS IS ACTUALLY REALLY GOOD WOW WILL I EVER BE ABLE TO REACH THIS LEVEL AGAIN? I'M GONNA PUT THIS IN THE NEW DRAFT!!!" 22. Are there subjects that make you uncomfortable to write? Romance and anything of the like. Its difficult for me, but for some reason I still try and the outcome is always disappointing. :"^) 23. Any obscure life experiences that you feel have helped your writing? I don't wanna get too detailed here, but pretty much my home environment is toxic and is not a fun place to grow up in, so Mercy is like my vent space. Silas is literally a punching bag if you didn't notice. I think he goes through as much as he does because its my way of releasing negative energy in a positive, harmless way. 24. Have you ever become an expert on something you previously knew nothing about, in order to better a scene or a story? My favorite thing to teach people is the difference between a graveyard and a cemetery because Silas is a grave digger. (P.S., a graveyard is connected to a church, and a cemetery is not. Silas works in a cemetery.) I also know a lot of cocktails (for Misha's sake as a bartender) even though I don't plan on drinking in the future. 25. Copy/paste a few sentences or a short paragraph that you’re particularly proud of. "It was clear from the air on his breath that he was a Jinx as well, but one who wasn't jaded. He told Silas one day that he was "too cold" to let hatred and bitterness consume him. At first, he thought that was a joke, but over the course of sitting next the boy at lunch and shivering in the middle of the summer, he found this to be true. He was the embodiment of ice, as Silas would say, but Dei insisted that he call him the host of winter instead. That was his magic ability."

#tag game#THANKS FOR TAGGING ME#I'm really short on time#but this was a fun destresser#get to know me#mercy#edith#silas#dei#joey

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

CONGRATULATIONS, PEYTON!

You have been accepted to play the role of LANA CHAMBERS with the faceclaim of IM JINAH. Please create your account and send it to the main in the next 24 hours. I know that there was no other application for this role, but even if it were, I can’t imagine anybody being able to capture who Lana is as a person better than you did. The application is immaculate, beginning to end, and you are clear proof of not only a talented writer, who twists words around with incredible skill, but also an amazing, vivid story-teller. Your paragraph sample caged my heart and it is yours forever, for you developed, with just the right amount of humor and snark, a balanced dynamic that I would sell my soul to read more of. Maybe soon. Anyway, I cannot wait to see the things Lana has to do that keep her too busy for love, for she already is such an asset and I believe you’ve only begun unfolding her.

OUT OF CHARACTER INFORMATION

Name and pronouns: Peyton, they/them pronouns

Age: 19

Time-zone: EST/-5 GMT

Activity level: It’s actually the end of the semester for me so I have a lot of free time! I’d give myself a 7/10 though because I do have a job, but with summer right around the corner I’d love to get back into roleplaying.

Triggers: None!

IN CHARACTER INFORMATION

Desired character: Lana Theodora Chambers

I love Lana because she is more than the stereotypical mean girl trope, having many hidden layers that make her only more complex. She’s unassuming with her background and scholarship, yet a shark in the water that no one at Oxford could have ever prepared for. She’s smart, witty, and acts like the ground is blessed the moment she walks on it. I admired the fact that Lana is so great and unapologetic about it because I believe there needs to be more female characters like that. A character like her is so important as she stays true to herself (even if she isn’t the most moral human being) and breaks the stereotypes that come with her kind of character. Gender and pronouns of the character: Cis female. She/her/hers. A crystal clear idea of what is meant to be masculine and what is meant to be feminine was ingrained in her from a young age. With her parents holding their more traditional beliefs, sons were celebrated, considered to be a great honor and cherished by their families, while daughters were but a small happiness. As the only child of the Chambers family, there was extra pressure for Lana to prove that she is a child to be proud of and oh how she has rubbed it in their faces.

Changes: I was just wondering if I could change her faceclaim to Im Jinah?

Traits: a m b i t c h i o u s → To say Lana aspires to be at the top would be a severe understatement. If she wants something, she fights tooth and nail and takes it. One thing people can say about Lana is that she has the uncanny ability to never give up. She’s worked too hard, put in too much effort to allow herself to slip now. In her hungry, unyielding eyes, she has yet to take everything the world owes her. When she’s surrounded by those who get whatever they want served to them on a silver platter, her perseverance and her determination will bring her on top of all of them. i n t e l l i g e n t → She learned four languages by the time she was seventeen. Auditoriums full of people would applaud after she played during her piano recital. Her poetry left those in awe as the words flourished, dripping down her chin like honey. She’d leave teachers singing her praise as she excelled academically, top of her class in every class, and captain of as many clubs she could be in. It’s impossible to deny that Lana has an impressive mind and may be one of the brightest girls of her age. Although she does not stand out quite as much in Oxford as she did back home, she isn’t going to let that inhibit her showing off her intellect in any way. She’s worked three times as hard as the rest of them and she’s going to prove her worth. r a t i o n a l → Lana is a fairly realistic thinking person. She’s goal orientated while keeping the important things the same. When she’s angry there are no fires burning down forests, and when she’s upset there are no oceans flooding cities. She watches Gwendolyn and her other peers and sees them for what they are– entitled dreamers without a care in the world. She’s the first to come up with a solution under pressure, the one to go to for guidance if she is willing to give you it, the one who keeps going despite any hardships. Lana is the type who appears to never lose her cool or allow herself to get carried away, if her head is in the clouds then she will lose sight of the path she’s been taking, both feet on the ground. i n s e n s i t i v e → To put it plainly, Lana cares for few people, and none of her peers at Oxford have proved show they are worth caring about. She’s got a tongue sharp as a whip and has no problem cutting even those she is friendly with down to size. She didn’t get into Oxford University on scholarship to make friends or to try and turn herself around. Her whole life has been taking what is rightfully hers, leaving bodies in her self righteous wake as she adamantly bulldozes her way forward. From what she knows, and she knows a lot, the world is a cruel place. Call her a cynic, call her immoral, call her a heartless bitch, she’ll just examine her nails and ask if you said anything important. i c y → If Gwendolyn is fire then Lana is ice, cold and calculating just like the slow touch of winter. She is fresh fallen snow, beautiful but it’s best if you do not touch. She’s the type of person to stare at you blankly when you approach her, not so patiently waiting until you walk away if you take too long to get to the point. Lana can ignore someone or rip their head off if they made the wrong move and honestly it’s impossible to tell which reaction she will go for. She is cold and harsh and comes off as someone who cares for so little it’s actually fairly alarming. c o n t r o l l i n g → It is no mystery that Lana loathes being held back and makes her own rules as if it is her own divine right. The moment she walks into the room she radiates power, and like so many others, said power goes right to her head leading her to be controlling and manipulative. She’s extremely perceptive and will store up gossip while oozing charisma that leaves people in awe the moment she opens her mouth. Lana is self serving and power hungry and will not allow anyone to stand in her way or let them inhibit her with their own issues. No exceptions.

Extras:

headcanons.

She’s actually changed her major quite a few times upon getting accepted into Oxford. From political science major to mathematics major to classical studies to biomedical engineering, Lana was actually unsure what she wanted to do. With such a brilliant mind she knew she was perfectly capable of doing just about anything. Finally, she has settled on pursuing a law degree and got into Oxford’s graduate program with flying colors.

Lana is an excellent dancer. While she enjoys many of her extra curricular activities, she’s been attending classes since she was little and it has a special place in her heart. With a ponytail tied tightly on top of her head, she would walk in with the same air of authority she has to this day. Unlike what her personality and appearance may give off, she loves ballet with a passion (although she occasionally she does contemporary dance as well), she can practice it for hours and relieve her stress that way. Her routines are impressive, like everything else she does, and when she was small her dream was to be a dancer.

Her father had left the family when she was too young to remember, not that she cares if he ever comes across her mind. It isn’t something she’s supposed to feel guilty over all and she barely remembers him. Her entire life has been her, her mother, and grandmother all under one roof. Her halmeoni was born and raised in South Korea, and is a big inspiration for Lana as she is a proud woman who takes no shit and goes right for the jugular. Lana loves her and hates her at the same time, mostly because their temperaments are so similar. Her mother is not negligent, albeit distant from her one and only daughter. She’s worked everyday during Lana’s childhood in order to make ends meet. The dynamic between the three of them is not very close, but still they’re family and one thing she took away from her upbringing was how your own blood trumps everything else.

Lana is bisexual, with no particular preference for one or the other. She does get around, however, as human contact is important for the mind and she knows that. She doesn’t have the time or optimism for anything long term though.

here’s some incorrect quotes for lana because they made me laugh.

lana: gwendolyn and i have the kind of easy chemistry where we finish each other’s- gwendolyn: sentences lana: please don’t interrupt me

nicohlas: you read my diary? lana: at first, i didn’t realize it was your diary. i thought it was a very sad, handwritten book

jacob: you’re probably one of those beautiful women that don’t even know it lana: no, i know it

lana: sophia, thanks for agreeing to see me sophia: i didn’t, you just walked in and started talking lana: i don’t have time for a history lesson

jacob: can we talk, one ten to another? lana: i’m an eleven, but continue

also here is a pinterest board for lana!

PARA SAMPLE

Lana pools her hands into her bag for the pack of Marlboro reds, her mother’s words echoing in her head as she does so. That stuff’s poison, the more you smoke the more you’re killing yourself and me. She knows it’s a bad habit and she tells herself she’ll break it by the she graduates. Realistically, cigarettes don’t have an adverse affect on your health if you only smoke them for a few years. Besides, with Sophia failing to get back to her, she needed something to take the edge off. There was always some sort of edge to Lana, in her voice, her body language, her opinions, she supposed was always sort of high strung (or as she preferred to think, high maintenance).

She didn’t think there was anything wrong with it, she wasn’t out at parties snorting angel dust in the bathroom, craving a constant high she couldn’t handle the harshness of reality. She wasn’t like that. She wasn’t like them. Life is tough but so is she, tougher than anyone else she knew. A little self medication here and there so she could stay focused and grounded was not something to feel ashamed about. Lana was more concerned with the consequences if people found out, if the perfect ice queen turned out to not be so perfect. She couldn’t allow the scholarship she fought so viciously for to slip through her fingers like sand.

“Thank god.” She mutters under her breath, pulling the carton out, finding a lighter already nestled in between the cancer sticks. The flame erupts and she watches it briefly, before bringing a cigarette to her lips and lighting it. Lana feels the smoke enter her body, swirling around her lungs, before exhaling out the open window. Oxford University on a Friday night meant parties and the rich’s definition of mischief, something she wanted no part of. She leans on the window sill, eyes ice skating around her view of the campus. Drunk students stumbling around, party music blasting in the distance, and lights flickering all around, she couldn’t believe this was an esteemed private school sometimes.

Lana looks at the cigarette for a moment, letting it burn. She could think of something poetic here, something deeper and better than the thousands of bland male writers that describe how a woman is like a cigarette. It’s familiar and she can’t quite put her finger on it until her mind goes back to her tan, witty but not as witty as her, Romeo.

Perhaps not Romeo. Things did not end well for him and he was too much of a cliché for Lana’s liking. Anyone could be a romantic these days.

The homecoming ball was an event she reveled in, enjoying dressing herself up and enhancing the beauty she already possessed. Although there was only so much of Gwendolyn’s rambling that Lana could listen to before needing a break, causing the girl to escape and find solace on the marble steps of the building and curbing her nicotine craving. The architecture taking her breath away as she sat in blissful silence– until she was rudely interrupted by a handsome stranger. Not that handsome was that much of a compliment, he was conventionally attractive after all.

“Mind if I sit with you?”

“Depends. What’s in it for me?”

“A stimulating conversation.”

“Stimulating? I’m already starting to fall asleep, pretty boy.”

“You think I’m pretty?”

She was amused, something that was near impossible for anyone to do. Yet, as he sat down next to her she found herself to be more welcoming than usual. After much contemplation, Lana figures it was the champagne that had caused her to be friendly to the boy. There wasn’t anyone worthwhile at Oxford, no one that would come across her mind once or twice. None of the boys there were King Midas, she was golden without their touch. The girls were more tolerable, though ultimately just as entitled.

“These things are such bullshit.”

I rather like them.

“They’re just another way for the entitled elitists around here to prance around like everyone cares about their Dior suits and Versace bags. The champagne’s good, though.”

“I thought all girls liked Versace.”

“I thought boys thought of girls to be something more than their clothes.”

“Of course. We care about what’s underneath.”

“You’re a neanderthal.”

Despite herself, he had made Lana laugh. She allowed herself to get lost in the moment for once. He had this charisma to him and she found herself being pulled deeper into the water until she was drowning in the conversation. They talked about school and philosophy and this and that. Not that it got personal– Lana had the ability to make people feel as if they knew a lot about her without giving away any secrets. A lost and nosy Gwendolyn had found the two and she had to deal with the same warning the leader had told them since she was recruited into the Quarrel Club, stay away from the Riot Club.

She remembers leaving her half lit cigarette by his side as she was ushered back inside. Not that it mattered now. They didn’t even exchange names and perfect strangers came and went. Her grandmother always told her to stay away from things like love, and to focus on her future because she was going to be something great and couldn’t afford any distractions. Lana was convinced she’d never allow anyone to get close to her. She had things to do.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"We should allow an African curator to turn the whole thing on its head"

The haughty dismissals of this year's Venice Architecture Biennale by western critics overlook the welcome involvement of African architects, argue Kabage Karanja, Stella Mutegi and Patti Anahory.

It can be said that nothing important or thought-provoking lacks controversy. This year's Venice Architecture Biennale serves it in plenty if we go by the criticism directed at the curatorship of professor Hashim Sarkis and his team as well as the many works produced by a diverse range of participants.

These criticisms include articles such as Carolyn Smith's critique in the Architectural Review, titled Outrage: The Venice Biennale Makes a Mess and Oliver Wainwright's review in the Guardian, headlined A pick 'n' mix of conceptual posturing.

Edwin Heathcote's review in the Financial Times was titled Full of words, questions and stuff.

Roberto Zancan's piece in Domus, titled Biennale, Stop Making Sense! at least presents a more balanced reading of the event, but yet with a sobering conclusion.

Our unapologetic positioning as Africans in this response to these criticisms cannot be understated, especially when considering architecture's poor heritage of representation of diverse thoughts and practices of people seen to be "below" the enlightened global North.

This year's biennale discusses urgent topics that we, as a global society, need to address if we are to build a more egalitarian, inclusive and ecologically conscious world

Broadly speaking and without too much posturing, we present a collective counter-position that can be partitioned into five main headings, with the simple brief to balance the debate surrounding this exhibition and how it was all put together.

It sifts through the thoughts of a few participants in the exhibition, processed and consolidated into, yes, more words and readings that can help visitors take a fresh and deeper look at the exhibition. We then conclude with some free-radical thoughts about the Biennale's future.

Traditional models versus emergent models

Many of the criticisms fail to place enough gravity on the heterogeneity of contemporary practices, and the ongoing expansion of the architecture discipline. It seemed clear that some of the readings were locked in a nostalgic past where architecture is synonymous with construction.

This year's biennale set itself to discuss contentions and urgent topics that we, as a global society, need to address if we are to build a more egalitarian, inclusive and ecologically conscious world.

The answers coming from participants attest to the diversity of topics that need to be engaged with if we are to achieve such a future, which has to be the opposite from, if at least in addition to a homogeneous one.

Architecture's knowledge and strengths go beyond the beautiful practice of building that too often gets obsessively relied upon to address the questions of how indeed we will live together.

The value of research and the installation format as a medium to convey its message

The seemingly blatant disdain toward research and or the diverse range of research production is another telling point in some of the critiques.

Much of architectural knowledge is produced through research and the ways to display them demand formats other than the traditional instruments of architecture, such as plans, sections and models.

The installations mocked as "research" are serious works that try to bring to the foreground many of the pressing issues of our times.

If the criticisms were targeted to the medium through which such works got expressed, it would have been acceptable. What is not acceptable is the ridiculing of long-term, serious efforts to advance knowledge in specific areas by discarding them, after short bursts of analysis into the work.

The role of the curator

The figure of the curator was also attacked. This could not have been more apparent the moment statements such as "a good curator should mirror the practice of a museum curator" emerged.

This could not have been more anachronistic. Museum settings are one thing, international platforms such as the biennale are another, from the way works are produced to their meanings, audience and lifespan, which attests to the diverse role architectural exhibitions play today.

The museum model has long been challenged and, arguably, surpassed. Architecture and art exhibitions have been shifting in character while undergoing a significant self-critical revision. It is the role of the curator to work towards creating the conditions and pushing boundaries for this new model to emerge.

To not have bothered in the first place: fighting pandemic procrastination

According to the curatorial team, only a handful of participants were able to maintain their initial proposals without the need to change or adapt their installation due to the hardships and ideological shifts in thought that the pandemic brought, such as the loss of sponsorship or logistical challenges from shipping to production.

This in many ways made the exhibition all the more refreshing and current to not only consider the impact of the pandemic but, in the words of Roberto Zancan, to consider that this year's biennale marked the end of an era. It was an incredibly difficult series of moments in time when the curator and the whole biennale institution found it crucial to have the exhibition.

There is a great need to reignite the energy of the city but also that of the architectural world as a whole. A decision made to live and work with the trouble, without the luxuries and mirage of the post-pandemic comforts that may or may not come to look back at 2020 and 2021 with the crystal-clear vision that hindsight affords.

Participants addressing architecture's inability to grapple with the most difficult of issues and crises across the planet

We find it hard to avoid the stereotypical depictions of critics' aloof and often ambivalent to works by diverse communities – and this exhibition has a good supply of diverse projects. Many participants either received the gross broad-brushed grouping under the demeaning banner of Hashim's selection bag of candy, or in many cases, given overly surfaced critiques about their seemingly pseudo research, or as described by one critic, served as inedible "word salad" – a description that even made the proudest recipients of this criticism giggle inside.

The celebration of the many African participants seemed to be cut short by the clouds cast over such works as Alatise's Alasiri installation

It begs the question, however, how deep did the critics dig to understand the participants, as probed in the Yoruba proverb quoted by Nigerian artist and architect Peju Alatise in Alasiri, her project in the Among Diverse Beings section of the Arsenale.

"Yara rebate gba Ogun omokunrin ti won ba afara denu", runs the proverb, which means "a small room can inhabit 20 young men if they have a deeper understanding for one another."

How much time was really afforded to actually review the work and research of the participants at the biennale, and by extension Hashim's curation of the entire exhibition? Surely the cultural barometers of our time might every so often need calibration to look in closer to read the longer climatic formations of such an event, rather than the immediate weather patterns of a press-day opening in isolation?

The celebration of the many African participants seemed to be cut short by the clouds cast over such works as Alatise's Alasiri installation. This is a continuous body of sculptural and architectural objects and readings, reigniting mythical figures of the past and present, all set within free-standing door openings linked to another African proverb that states: "Eniyan ri bi ilekun, to bagba e laye ati wole, o ti di alasiri" ("People are like doors; if they permit you in, you become their keeper of secrets").

"How will we live together is a poignant question, made more complex by the current Covid 19 crisis," said Alatise, whose body of work both creates and inhabits a space where both women and men are liberated through a phantasmagoria of feminist origins and infrastructures. "The answer begs for moral inclusion that I feel architecture alone cannot give."

Patti Anahory (who co-authored this piece with Kabage Karanja and Stella Mutegi of Cave_bureau) and Cesar Schofield Cardoso from Cape Verde present their project Hacking (the Resort): Water Territories and Imaginaries in the Arsenale in the As Emerging Communities section.

It features an exquisite artisanal fishing line floating plastic bottle wave installation, which in their own words "investigates a confluence of the possibilities where tourists and local labour meet in a choreographed strained dance of labour and leisure".

This project imagines a space and time where both disparities and possibilities are confronted in equal measure, with a continuous body of work that manifests in their built projects and digital artworks.

Separately, with the biennale in mind, Anahory emphasized the disparities in funding allocations to realise the exhibition. She asks what would happen if all participants were constrained to a capped budget as a way to balance the output from both an environmental impact perspective, and to squarely bridge the north and south global economic divide.

This project was also whitewashed under the broad-brush criticism of the entire exhibition

Our Nairobi practice Cave_bureau presents The Anthropocene Museum, "Obsidian Rain", an installation under Galileo Chini's fresco in the dome of the Central Pavilion in the Giardini, presented as part of the As One Planet section curated by Sarkis. This is a post-colonial architectural reading, representation and proposal to critique the anthropocene era.

This project was also whitewashed under the broad-brush criticism of the entire exhibition, dismissing the installation via comical depictions of moonstones and meteor showers, when in fact the hanging obsidian stones follow the shape of a cave used by Mau Mau freedom fighters during the colonial period and celebrated by Malcolm X.

Today, Cave_bureau uses this story to curate forums of resistance against the continuous neoliberalist expansions of geothermal energy extraction that is often done to the detriment of the local Masai community and the natural environment in Kenya.

The stones, sourced from the Great Rift Valley, reference mankind's earliest raw material, which was used to create stone tools. This is an ignored architectural heritage that catapulted the homo sapien species into the troubled brave new world that we find ourselves in today.

So here the floating cave structure is critically juxtaposed against Chini's fresco in the dome. This architectural refocusing is grounded further back beyond Plato's Allegory of the Cave; that is, the human race's collective heritage of cave inhabitation by our early ancestors. This is a heritage that is still caricatured right up to today, more so in the surfaced reading of this work.

Concluding together

We live in a deeply broken and divided world where many of the participants choose to work with the communities that are most affected by the global pressures that have their anthropogenic roots in slavery, imperialism and colonialism.

This is a continuous struggle lived through today, epitomized by the climate crisis movements, The Black Lives Matter movement and women's rights movements among many others. These pressures are intertwined and exacerbated by the present-day neoliberalist powers.

Architects can no longer ignore and leave this difficult work to politicians and activists to address these formidable global challenges

It was in fact the use of the hybrid counter powers of the contemporary arts within architecture that was heavily criticized, which in fact allows many to mould our place within the profession that often struggles to meet the current global challenges head-on.

As Sarkis intimates, architects can no longer ignore and leave this difficult work to politicians and activists to address these formidable global challenges, lest we all just remain as professional pawns aloof and marginalized from the pulse on the ground.

The question posed by Sarkis, "How will we live together?" in many ways remains both rhetorical and requiring an immediate space to grow and generate these answers together, especially when many voices and ideas continue to be silenced and ridiculed.

One could argue that the profession remains in the early sketching phase of confronting our impotence in the face of these pertinent global challenges of our time, while the hurried brick-and-mortar readings and spatial-planning remedies that seemed to be so desperately craved could very quickly lead us towards the mistakes of our forebears.

One welcome criticism was that future biennales can no longer remain the same: this one indeed marks the end of an era

This biennale was in fact a safe and open space, where we never felt overburdened to be the monolithic authors of a bright new future but instead allowed to creatively work with the cultural and physical matter that would in fact help us forge this new future together.

One welcome criticism was that future biennales can no longer remain the same: this one indeed marks the end of an era, where mountains of matter are shipped to Venice without confronting and justifying the carbon footprint. We should enact previous suggestions where carbon is sequestered by planting trees across the globe and through working with marginalized groups to do so.

We should be questioning if anything should be shipped in the first place? Maybe we should even be pondering over the observation by one critic to look at the accumulated knowledge and dexterity of many of the domestic biennale installers, subcontractors and artisans that could be curated in its own right.

Finally, we should allow an African curator to turn the whole thing on its head. Maybe the one wearing the latest Royal Gold nugget on his neck right now or, better still, his protege, Nigerien architect Mariam Kamara, whose contribution to this year's biennale was close to genius if you care to look and listen a little closer.

Kabage Karanja and Stella Mutegi are architects and spelunkers who founded Cave_bureau in 2014. They are natural environment enthusiasts, leading the bureau's geological and anthropological investigations into architecture and nature including orchestrating expeditions and surveys into caves within the Great Rift Valley in east Africa.

Patti Anahory is an architect, educator and independent curator and co-founder of Storia na Lugar, a storytelling platform and [parenthesis], an independent space for inter(un)disciplinary exchanges, creative experimentation and cross-disciplinary dialogue. Her work focuses on interrogating the presupposed relationships of place and belonging in reference to identity, memory, race and gender constructs. She explores the politics of identity from an African island perspective as a fugitive edge and radical margin.

The main image shows Cave_bureau's Obsidian Rain installation at the central pavilion.

The post "We should allow an African curator to turn the whole thing on its head" appeared first on Dezeen.

0 notes

Text

The Ongoing Problem With Trans Representation in Media

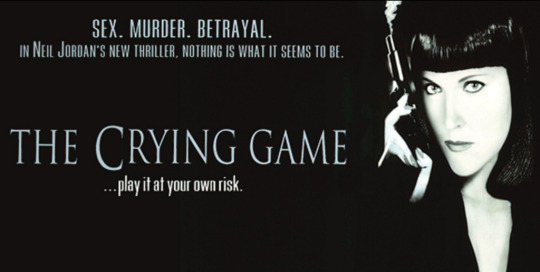

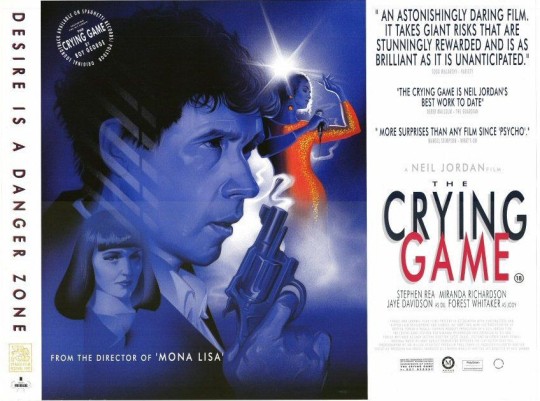

The Crying Game

In 1992, as a budding Transgirl who hadn’t yet heard the word “Transgender” nor knew anything about gender or sexuality, I watched an film by Neil Jordan called “The Crying Game.” It was dubbed “The Most Shocking Film Of The Year” by entertainment magazines. At the time, I had an insatiable longing for people I could relate to on film, and often had to substitute women as figures of my future intent; I wanted Richard Gere to sweep me away like he had Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman. I wants to slither around like Catwoman, with that brilliant confidence that was the perfect mix of bad ass girl power and unapologetic confidence. She was my revenge idol. I wanted to flip-flop, cartwheel and yoga pose into school and kick the shit out of my bullies while making them all love me at the same time.

But the Character of Dil in “The Crying Game” was most accurate to who I knew I was becoming. This androgynous, beautiful woman captivated me. Dil was the lover of a soldier, Jody, played by the incredible Forest Whittaker, a man held prisoner by the IRA who pleads with a fellow solider and friend, Fergus, to protect Dil. She unwittingly becomes the subject of both fascination and affection of Fergus.

Through the course of the film, the two fall in love, and when it comes to the pivotal moment where the characters start becoming intimate- it takes a dark turn.

As Fergus begins to disrobe Dil in the bedroom of her bedroom, he gets on his knees, expecting to find female genitalia and instead reveals a penis.

Yes, right there. A penis. And if you saw it in the cinema, a 12 foot tall image of a penis. On a woman. Fergus twisted away in disgust and proceeds to vomit immediately. Then, he hits her.

I remember being horrified- my breathe caught in my throat- not because she had a penis, but because he acted with such sudden and unexpected repulsion over someone he was just kissing and intending to bed.

The film was marketed on the Trans “Surprise.” Studios launched campaigns for audiences not to give away the ending.

In the afterglow of The Crying Game, Transphobic rhetoric became more aggressive than ever in cinema. Who can forget Ace Ventura, played by Jim Carey, belllowing “Einhorn is a man?!” in reference to the character played by Sean Young, and then heaving into the toilet at the very notion an attractive woman might not have a vagina.

youtube

Transwomen were reduced to bawdy, comedic or grotesque twists by lazy writers in Hollywood. The go-to joke. The trend continued throughout the 90’s and well into the 2000’s. With what little Trans characters there were on screen, they were always the subject of comedy or villainy. Because, for some reason, it’s still an outrageous knee-slapper to see a sexy woman you suddenly discover has male genitalia or much easier to hate her, so they make her the freakish bad guy, such as in Sleepaway Camp, like some dangerous modern day Frankenstein who will curl their hair, twirl their penis then sit your throat.

More recently, the Trans representation in film has changed in context- with sweeping period dramas like “The Danish Girl” — which won an Oscar for the cisgender actor, Eddie Redmayne, playing the role of a Trans woman. Or, the “Dallas Buyers Club” — which won an Oscar for the cisgender actor, Jared Leto, playing the role of a Trans woman. However, the year that Redmayne won his Oscar for putting on a dress and pretending to be Trans, a film that had been far better received critically, Tangerine, which featured two actual Transwomen played by Transwomen, was snubbed, despite receiving nominations or awards by every other organization the entire awards season. The Academy demonstrated they’d rather give an award to a man tepidly playing a Transwoman, than a Transwoman giving an incredible performance.

Of course, those Transwomen were playing sex workers. I have it on good authority from my Trans identifying actress friends that it’s almost impossible to get roles for anything else. “All I get offers for are prostitutes,” one accomplished actress told me. “If we want access to work we either have to be a prostitute, a mistress, a self-hating trans person, dead or dying of AIDS, or willing to be ridiculed for comedic value. That’s where we are. In 2018.”

But, some will argue the merits of “Transparent,” The Amazon series that features a middle aged man, portrayed by Jeffery Tambor, who transitions from male to female later in life. It is the first television show to take viewers on that journey, one which details the experiences of those in the orbit of the transitioning main character, including her children and ex wife, without exploiting it as sensationalist. “Transparent” features a plethora of Trans identifying artists, both in front of the camera and behind it. While the primary stars are all cisgender performers, Alexandra Billings, Trace Lysette and the iconic Candis Cayne are all series regulars. Zackary Drucker and Our Lady J feature as producers. It appears to be our staple; our one single thing we’re allowed. Unfortunately, although heavily awarded, it’s not got very broad appeal. It’s a series by Transgender people, about Transgender people… so mainstream remains a little stand-offish. It’s “That Transgender show.”

That’s not surprising. We Trans people working in media have to pave our own way, create our own projects, self produce them, star in them. If we try to intermingle cisgender society within our works, we’re typically turned away. As a writer, I’ve had my screenplays turned down by many companies exclusively because, despite having a cisgender lead, it has a trans character. In a fantasy film I wrote which was a finalist in Outfest International’s Screenplay competition, the response I received from interested production companies wanted me to turn the Trans girl into a “traditional” girl. Every film I write has a Trans character, not just because I’m politically advocating the normalizing of Trans people in everyday society, but because I refuse to create worlds in which we do not exist simply for the comfort of mainstream audiences. “Why does she need to be Trans?” An agent once asked me.

“Why not?” I answered.

Orange is the New Black was lauded for it’s inclusion of a Trans character, played by a Transgender woman, Laverne Cox. Because gender diverse characters in media are so rare, it catapulted her well beyond the boundaries of performance into the realm of social activism. That same attention and expectation destroyed Caitlyn Jenner who was no longer just allowed to be the tabloid mainstay by proxy of the Kardashians, but now had to be our fearless leader, our ambassador to cigender tribes. There are about five Trans figures that cisgender audiences can name: Caitlyn Jenner being the most notable along with Cox on a lesser scale. Others paying attention know that the Wachowskis, directors of the successful Matrix franchise both transitioned and Jazz Jennings, the teenager with her own reality show on that channel that also shows My 600 lb Life and Sister Wives. Cis people don’t know Janet Mock, although her work is invaluable, but they heard a Transgirl took on Rose McGowan at a book signing. Our names cross their facebook feeds when the news reports our deaths. Beyond that, we’re people not allowed to use bathrooms in certain states, a word that is banned by the CDC, and reduced to that one Transgender person who did something that one time which the media loves to exploit for a headline in a fleeting story. Especially when it’s salacious. When former Playboy Playmate, Kendra Wilkinson’s basketball star husband, Hank Baskett, had an alleged affair with a woman, the media latched on like a thirsty tick to the ass-end of a fat dog because that his mistress was Transgender. Of course, despite evidence, he denied it, and the couple leveraged the scandal to maximize ratings and profits by following the controversy on their reality show. They even starred in their own one-hour special to discuss it. Similarly, the media pounced at the opportunity to reveal the alleged affair that Jennifer Lopez’s then boyfriend, Casper Smart, was having with a Transwoman he met on Instagram. Then there was the story of Michael Phelps, the olympic gold medalist who had an ongoing, but secret relationship with an intersex woman- one which he never denied, but ignored instead. In every case, the transwoman is vilified by the media, like some sexual predator; A succubus who cast a spell of seduction on innocent men. That’s when the media pays attention.

That’s problematic. The fact that mainstream society possesses more general awareness of cis actors who play Trans characters, or random Transwomen involved in scandals does nothing to improve our actual visibility, or integrate us into mainstream culture. It alienates us further onto the fringes of society.

We’re like the unicorns of media. When one of us pops up and garners any attention for something other than simply being Trans or scandalous, people react with; “Wow, you really do exist.”

Far and few are the opportunities for Trans actors and actresses, filmmakers and film writers. It’s not because there are too few of us, it’s because when Hollywood looks at us, they don’t see our potential, they see a political cause. An embattled, marginalized person. When we disclose our trans status to people, they suddenly lose sight of our face and instead see the last anti-trans headline they read splashed across out forehead- and maybe they feel sad. Maybe they feel that if they’re uncomfortable or distracted exclusively by the fact that we’re trans, moviegoers, television viewers and the greater cisgender community will be too.

Perhaps this is why we haven’t really seen a transgender performer portray a non-trans role- unless you count Candis Cayne playing a fairytale creature in The Magicians. Cayne is such a brilliant performer she could play anything. She’s stunning, she’s captivating onscreen, she’s a staggeringly talented actress…

But apparently, despite the multitude of cisgender actors playing trans in media, she isn’t allowed to play a ciswoman… just trans, and maybe a unicorn.

Powered by WPeMatico