#henry pickersgill

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Henry Pickersgill, A Young Greek Woman (detail)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry William Pickersgill (English, 1782-1875) A Young Greek Woman, 1829 Benaki Museum of Greek Civilization, Athina

#Henry William Pickersgill#english art#english#england#greek#greek maiden#a young greek woman#1829#1800s#art#fine art#european art#classical art#europe#european#fine arts#oil painting#europa#mediterranean#greece#southern europe#woman#female

168 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Art Details Series: Play for me

|| John Ferguson Weir, Henry William Pickersgill, Georges Antoine van Zevenberghen, Luis Álvarez Català, Thomas Wilmer Dewing, Jan Frederik Pieter Portielje, Lilla Cabot Perry, Michel Garnier ||

#women#women in art#art#art details#art detail#20th century art#19th century art#18th century art#17th century art#paintings#painting#oil painting#instruments#John Ferguson Weir#Henry William Pickersgill#Georges Antoine van Zevenberghen#Luis Álvarez Català#Thomas Wilmer Dewing#Jan Frederik Pieter Portielje#Lilla Cabot Perry#Michel Garnier#art series

645 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry William Pickersgill (English, 1782-1875)

A Syrian Maid

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nun, Henry William Pickersgill

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

1826 Georgiana Carolina Dashwood (1796–1835), Lady Hastings by Henry William Pickersgill (Seaton Delaval Hall - Seaton Sluice, Northumberland, UK). Probably from artuk.org.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry Hall Pickersgill - Mortal Remains of Jeremy Bentham, 1832.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Georgiana Carolina Dashwood (1796–1835), Lady Hastings Henry William Pickersgill (1782–1875) National Trust, Seaton Delaval

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carthage and its Ancient Origins

By Artist, Henry William Pickersgill - Engraved by D. H. Robinson - William Jordan - Autobiography, Volume 3, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65129435

Letitia Elizabeth Landon, more commonly known as L.E.L., lived from 1802-1838, was an English poet and novelist. She learned to read early and at age 5, attended a school taught by Frances Arabella Rowden, who was a poet herself and encouraged it in her pupils. In 1809, her family moved to the countryside so her education was taken over by her older cousin Elizabeth, who found that L.E.L. was above her level. She was close to her brother, two years younger than her, and began publishing when she was 18 to help pay for his university education. He became a minister and decided to repay her by spreading lies about her. Her poetry was well received by the public, with her initials becoming 'speedily…a signature of magical interest and curiosity' as one critic wrote. She took advantage of the trend of annually produced gift books to expand her career. During her career, she also wrote prose, publishing several novels in addition to her many poems and books of poetry. In 1835, John Forester, her fiancé at the time, became aware of rumors her supposed sexual activity and demanded she refute them. She told him to refute them himself. He did and she broke off their engagement, not wanting to be married to someone who didn't trust her. In 1836, she met George Maclean at a dinner party and saw him as a way to get out of England and they married that next year. In August 1838, they arrived in Cape Coast, Africa. In October 1838, she died of what was likely Stokes-Adams Syndrome which causes fainting due to cardiac irregularities that leads to inadequate blood flow, fainting, and possibly death and is exacerbated by stress and she had the medication for it near her.

By damian entwistle - originally posted to Flickr as tunis carthage museum representation of city, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9049084

Her poem Carthage, she addresses the fallen city of the Phoenicians that was the capital of the Punic empire. The Punic empire dominated Mediterranean trade in the first millennium BCE, prior to the end of the Third Punic War in 146 BCE, leading to the fall of the Punic empire. In her poem, Landon asks '[d]ust, the wide world's king,/where are now the glorious hours/Of a nation's gathered powers?' She points out that the fall of the Punic Empire was '[l]ike the setting of a star,/In the fathomless afar;/Time's eternal wing/Hath around those ruins cast/The dark presence of the past.'

You can read the poem here.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How A Teenage Girl Became Queen of England For Nine Days

The show My Lady Jane took creative liberties, but Jane’s real-life rise and fall were full of drama. Fourth in line at birth, she was unexpectedly Crowned Queen, only to face a devastating end.

— By Erin Blakemore | September 26, 2024

A portrait of Lady Jane Grey, who reigned as Queen of England for 9 days in 1554. This is one of the earliest surviving portraits of Lady Jane Grey, despite being made some forty years after her death. Photograph By CBW/Alamy Photos

Historic travesty or juicy royal soap? The now canceled series My Lady Jane was both, playing fast and loose with history even as it introduced a new generation to the saga of the doomed Lady Jane Grey, who was England’s queen for just over a week before her execution at age 17.

Who was Lady Jane‚ and why does the story of her disastrous reign still resonate today? Here’s how the teenager became queen and lost the throne in just a few fateful days in 1553.

A Struggle For Succession

When King Henry VIII died in 1547, his son Edward VI succeeded him at just 9 years old. A regency council ruled in his place until he came of age. Jane Grey, Henry’s niece, was the same age as Edward, her cousin, and had been fourth in line to the throne when she was born. When he was crowned king, she became third in line after Henry’s daughters (Edward’s half-sisters) Mary and Elizabeth.

Council members competed to influence Edward, who was seen as sickly and pliable. By the time Edward and Jane were teenagers, John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, had pushed his way to the top.

As the king’s most trusted advisor, Dudley was arguably the most powerful man in England. He was also destined to become Jane’s father-in-law.

Who Was Jane Grey?

The teenager was exceptionally educated for a young woman of her time. Multilingual and accomplished in both academic and domestic pursuits, she was known as pious, studious, and charismatic. But she had no choice as to her future: Like other daughters of nobility, Jane was expected to submit to an arranged marriage designed to consolidate power and bring prestige to her family.

An oil painting of a women in a green and beige dress sitting on a red bench reading a book. Windows placed behind her with trees and people gathered outside.

Lady Jane Grey painted by Frederick Richard Pickersgill in the 1800s, centuries after her death. Photography By The Fine Art Society, London/Bridgeman Images

Accordingly, her parents brokered a match to Guildford Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland’s son, and they married in 1553, when she was 16. Though historic accounts differ, Jane is thought to have opposed the match. One chronicle even states that Jane’s father beat her until she agreed to marry.

In the meantime, the King Edward had become gravely ill. As his death approached, the Duke of Northumberland played on fears that if she took the crown, Mary, a Catholic, would destroy the Church of England and that both Mary and Elizabeth might marry outsiders, diluting the power of the British throne. He convinced Edward to exclude them both from the line of succession, instead pushing the Duke’s new daughter-in-law, Jane, to the front of the line for the throne.

Despite quarrels over the legality of this arrangement, Jane was named Edward’s heir—and when the king died on July 6, 1553, Jane became queen.

Jane Becomes a Reluctant Queen

This was news to the teenaged Jane, who had apparently not been informed of the arrangements beforehand. As the men around her knelt in obeisance, she later recalled, she “[declared] to them my insufficiency” and “greatly bewailed myself.”

A black and white engraving of five men kneeling to a woman standing to the right of the frame, pleading for her to accept the crown of England.

An engraving depicts Lady Jane Grey's reluctance to accept the crown at Sion House, the west London residence of the Duke of Northumberland. Photography By Walker Art Gallery/Alamy Photo

Panicked and shocked, she prepared to move to the Tower of London, where new royals traditionally resided before their official coronation. On July 10, she traveled to the tower on a royal barge.

As the Holy Roman Emperor’s ambassador Jehan Scheyfve ominously noted, “No one present showed any sign of rejoicing, and no one cried: ‘Long live the Queen!’”

The new queen seemed deeply uneasy about her accession—she had to be convinced to don the crown. In a move that appeared to reflect her horror at the Duke’s attempt to gain power through her marriage, Jane refused to allow his son Guildford to be crowned king consort without approval from Parliament. This predictably infuriated the Duke.

Lady Jane Becomes a Prisoner

Within days, Mary sent an army to London to depose Jane. Though the Duke initially attempted to raise an army on her behalf, Jane’s royal council soon disbanded, leaving the teenage queen and her remaining supporters virtual prisoners inside the Tower of London. Meanwhile, the Mayor of London declared Mary queen.

Finally, Jane’s father came to the tower and told her to stand down, declaring that she “must put off [her] royal robes.” Jane reportedly replied, “I much more willingly put them off than I put them on.”

Just nine days had passed between Jane’s proclamation as queen at the Tower of London and her abandoning her claim to the crown on July 19, 1553. Though she relinquished it easily, Jane was already marked for death.

Mary triumphantly headed to London to take up the throne, and the Duke of Northumberland fled for his life. He was apprehended and brought back to the tower, where he was imprisoned with Guildford and his other sons. He was beheaded for treason soon after, despite hastily converting to Catholicism in a bid to gain favor with Mary.

Jane wrote Mary from prison, narrating the events leading up to her accession, apologizing for taking the crown and begging for her life. The letter portrays her as a pawn in her ambitious parents’ and in-laws’ game, and she writes that she was “stupefied and troubled” by how she was ushered onto the throne.

Jane Grey's Execution

Jane seemed to have convinced Mary to spare her life, even after she and Guildford were both tried and found guilty of treason. But the new queen’s patience broke when Jane’s father participated in a short-lived rebellion in opposition to Mary’s planned union with a Spanish king. The ascendant Mary sentenced both Jane and Guildford to death.

Jane might have been able to save herself by converting to Catholicism, but she refused. She also refused to see her husband, whom she had apparently come to love, citing the “misery and pain” that would come with a meeting and telling him they would be forever linked in death.

Oil painting of a woman in a white dress and a white blindfold being prepared for execution. There are two men to the right of the frame preparing her for the execution and two women in distress to the left.

The execution of Lady Jane Grey, painted in 1833 by Paul Delaroche. Photograph By Bridgeman Images

On February 12, 1554, Jane was killed shortly after her husband’s execution. “I am come hither to die,” she reportedly said to the assembled crowd before the axe fell, confessing her guilt, reading a prayer, and begging the executioner to be quick. Then she was beheaded—a casualty of ambition, greed, and a historic struggle for the throne.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry William Pickersgill (English, 1782-1875) A Young Greek Woman, 1829 Benaki Museum of Greek Civilization, Athina

0 notes

Photo

Dress in the Age of Jane Austen

This book by Hilary Davidson comes to us through Yale University Press, so it is a deep dive into the clothing of the era, both men’s and women’s. I got it right before the Art Institute of Chicago was about to do a show on late 18th Century fashion, right before the Regency which is technically 1811 to 1820 but which is often thought of as very late 18th century to the 1837.

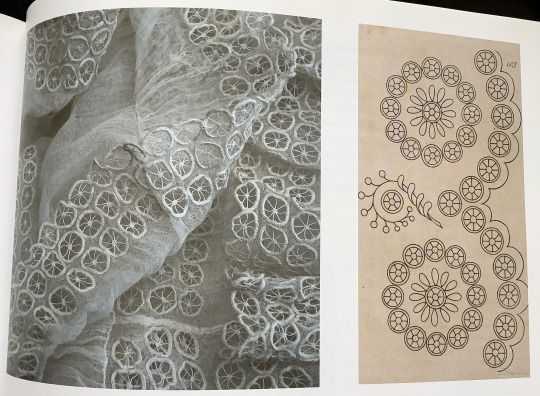

This book is organized thinking geographically, so it starts with a chapter called Self which is really about the body and how it was or was not on display, then goes through Home, Village, Country, City, Nation, and ends with World which gives us the great global trade which brought Indian and other textiles from across the seas. Along the way, we have plenty of images as you can see above and Davidson traces fashion construction and the sources that influenced it, all while referencing what we know about Austen and about what she wrote.

So you see lots of global influences in the saucy women in the gold coat with military trimming was made of Merino cloth from Spain and Astrakhan fur and her cap was styled after an Algerian helmet according to the caption that went with it in 1811. Then, you see how a woman of 77 would appear in the portrait of Hannah Moore from 1822 by Henry William Pickersgill who wore an abundance of ruffles near her face. A nice softening effect near older skin. Then you see a close-up detail of the fabric of an evening gown, all hand-embroidered, and a pattern for a similar kind of embroidery. Davidson draws attention to both the enormous amount of time and the fine skill needed to pull such a creation off.

There is plenty on men from their fancy waistcoats to their military uniforms--remember when the regiment meant to much to the Bennets? --to their caped coats. The book ends with the Austen family tree, a time-line of changes in gowns, and a full glossary of the technical terms. In short, lots to see and learn, and plenty of references to the many ways fashion shows up in Austen’s books and in the age of Regency.

You can find it here: https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300218725/dress-age-jane-austen

#jane austen#regency era#regency fashion#Dress in the age of jane austen#hilary davidson#vintage fashion#women's fashion#men's fashion#global trade#history of fashion#fashion history#dress history#costume history#dress history book#fashion history book#costume history book#yale university press#hannah moor#henry william pickersgill#vintage embroidery#fashion in fiction

238 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Henry William Pickersgill (English, 1782-1875) Emily Maria Pickersgill, later Mrs George Hebberd Cable (1837 -1924) in Spanish Costume, 1850

#Henry William Pickersgill#english#england#Emily Maria Pickersgill#Mrs George Hebberd Cable#art#spanish#europe#european art#european#brunette#female portrait#woman#18th Century#19th Century

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charlotte Williams-Wynn in c. 1840, by Henry William Pickersgill

1 note

·

View note

Text

Henry William Pickersgill (English, 1782-1875)

A Young Greek Woman

163 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Edward Bulwer-Lytton, 1831, Henry William Pickersgill

123 notes

·

View notes