#heinrich von treitschke

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Die Macht der Gemeinheit und Dummheit ist nur zu oft größer als die Macht der Ehrlichkeit und des gesunden Menschenverstandes.

The power of meanness and stupidity is all too often greater than the power of honesty and common sense.

Heinrich von Treitschke (1834 – 1896), German historian, publicist, politician, trailblazer of anti-Semitism in the German bourgeoisie

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw your post about using Judenhass/anti Jewish hate over the term antisemitism, is there a reason for the change?

Yeah.

So, "antisemitism" in its current popular usage was pioneered by Prussian nationalist historian Heinrich von Treitschke and German journalist William Marr as a means of distinguishing between old-school Judenhass & their new form of hating Jews. It was literally a way of dressing up their hatred of Jews in a way that was more "scientific" and "legitimate." It first appeared in print in Der Weg zum Siege des Germanenthums über das Judenthum (The Way to Victory of the Germanic Spirit over the Jewish Spirit, 1880). As a means of discussing prejudice, discrimination, and hatred, it has never been aimed towards anybody but Jews, full stop.

But, you know, lots of people on Tumblr (and elsewhere) have decided that this isn't actually what the word means, and are whipping out the old "Jews aren't the only Semitic people!" bit of bullshit. It's not a good-faith thing; it's meant as a "shut up while we're openly antisemitic, you don't get to define your own oppression, dirty lying Jews" refutation of really basic and really obvious shit.

So... let's just go back to the original word. "Antisemitism" can't be used bc Jews aren't the only Semitic people? Okay. From now on when I mean Judenhass, I'll just fucking say Judenhass.

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

Awful Peoples awfull retelling of history

So I wrote an Essay about Heinrich von Treitschke, a german historian in the 19th century. He was part of the borussianist school of thought, these are the historians who tried to legitimate a german unification without austria and under prussian rule (Which happened in 1871). And sometimes you read sources which try to not blast you with their Ideals and biases (of course they have such, but they try to not make them too obivous). But then you have those sources, which just scream I hate such and such.

A source like that is Heinrich von Treitschke. In his writing about the congress of vienna he wrote the following about the habsburger monarch: “Geistlos und denkfaul, wie die Mehrzahl seiner Ahnen, völlig unfähig [...]” (s.19). (translation: mindless and too lazy to think, like most of his ancestors [...])

And while I dont sympatize with von Treitschkes Ideals, which were 19th century national-liberal (liberal in this case means he wanted a consitutional monarchy and more rights for the Bourgeoisie). It made my day reading his accusations against the Habsburgs, for the first time.

Treitschke also was quite the unlikeable Character and a big antisemite, spending less tastefull words on jews. He was cited heavily during the Ns-Zeit of germany, a quote of his, which I dont want to cite here became very popular, being used in a big antiesmite newspaper. So while I encourage reading his works, be careful not to take his words without the context of his character and biases, there are far better recounts of everything he writes about by today, so perhaps read those if you want an accurate description of for example the congress of vienna or the Sattelzeit as a whole.

0 notes

Text

The quotation marks sjsbksmksnwk

#frederick the great#The Confessions of Frederick the Great And the Life of Frederick the Great: Frederick II and Heinrich von Treitschke

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

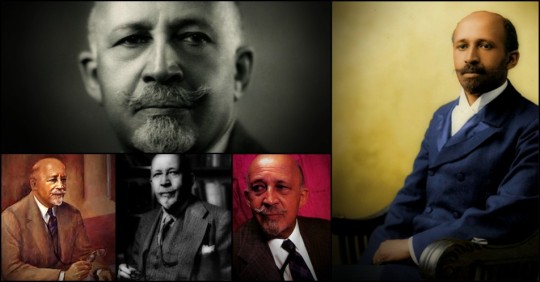

In 1903, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in the prophetic The Souls of Black Folk that “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.” Eventually, he became a stalwart friend of the Jewish people.

Studying at the University of Berlin in the 1890s, Du Bois absorbed the volkisch German nationalism of his teacher, Heinrich von Treitschke, who said: “The Jews are our misfortune.” Du Bois remembered that he had “followed the Dreyfus case,” and was aware of “Jewish pogroms … in Russia,” but had no deep sympathy for the Jews.

In 1903, Du Bois claimed, wrongly, that Russian Jewish immigrants to the southern US, together with the “thrifty and avaricious” Yankees, were “squeez[ing] more blood from debt-cursed tenants.” Du Bois’ attitude quickly changed when he worked with Joel E. Spingarn, Henry Moskowitz, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Lillian Wald, and other Jews prominent in forming the NAACP.

Zionism provided a model for Du Bois’ own pan-African ideology: “The African movement means to us what the Zionist movement must mean to the Jews.”

Holding up the Jewish people as a “tremendous force for good and uplift,” he reciprocated Jewish support by putting the NAACP on record against The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. He condemned antisemitism in Poland and Hungary, as well as in Germany, and commended Albert Einstein.

In May 1933, he editorialized about the dangers of Nazism: “It all reminds the American Negro that after all race prejudice has nothing to do with accomplishment. … It is an ugly, dirty thing. It feeds on envy and hate.”

Even after the passage of 1935’s Nuremberg Laws, street corner “Harlem Hitlers” in New York organized anti-Jewish boycotts. But visiting Hitler’s 1936 Berlin Olympics, Du Bois decided that Nuremberg was worse than Alabama.

In 1940, Du Bois warned against African-American antisemitism, inflamed by German and Japanese propaganda. Despite initial doubts about America entering World War II, Du Bois remained steadfast in denouncing Hitler’s war against the Jews and supporting Zionism. As the Nazi war machine rolled east in June 1941, Du Bois joined African-American intellectuals like Ralph Bunche warning of the threat of “a new slavery and barbarism, terrorism and darkness” engulfing the world.

As early as January 1943, Du Bois announced that the murder of three million Jews marked the end of Europe’s leadership of civilization. In September 1943, he reported on the unfolding Holocaust without using the word: “We rightly shrieked to civilization when American Negroes were lynched and mobbed to death at the rate of 400 to 500 a year. Today in Europe and among peaceful Jews, they are killing that number each day.”

Du Bois, in 1945’s Color and Democracy, gave what was an unusually accurate accounting of the loss of “6,000,000 souls … this is a calamity almost beyond comprehension.” In 1948, he called the Holocaust “a supertragedy.”

During World War II, he was an African-American Cassandra warning of an unmatched catastrophe that few Americans of whatever religion or race wanted to hear about or believe.

Historian Harold Brackman is coauthor with Ephraim Isaac of From Abraham to Obama: A History of Jews, Africans, African Americans (Africa World Press, 2015).

The opinions presented by Algemeiner bloggers are solely theirs and do not represent those of The Algemeiner, its publishers or editors. If you would like to share your views with a blog post on The Algemeiner, please be in touch through our

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the Russian pogroms of 1881 until the outbreak of World War I in 1914, over two and a half million Jews migrated westward from Eastern Europe. Although America was the intended destination of the vast majority, Germany was the main gateway to the West, and the passage of refugees through German borders provoked fear of mass immigration. Despite their relatively minor presence within Germany, the concentration of Ostjuden in urban centers such as Berlin's Scheunenviertel created the appearance of a strong presence. Anti-Semitic discourse amplified this perception. The historian Heinrich von Treitschke denounced the impoverished Ostjuden who, according to him, leeched off of the German economy and then climbed their way into wealth and power. Ostensibly a response to the influx of East European Jewish beggars and peddlers, Treitschke's critique actually obscured the difference between the immigrant Ostjuden and native German Jews.

The response of German Jews to the immigrant question — or Ostjudenfrage — was mixed. At the organizational level, German Jews acted charitably toward the refugees, establishing aid agencies to fight for their basic rights and economic improvement. But most regarded the Ostjuden as a hindrance to German-Jewish integration, and many aid organizations therefore encouraged their settlement abroad. Theodor Herzl defined political Zionism along these lines as "a kind of new Jewish care for the sick." According to Herzl, the goal of political Zionism was to eradicate the poverty-stricken ghetto by facilitating migration to Palestine. Whether contemptuous or compassionate, responses to the plight of East European Jewry demonstrate the extent to which German Jews had dissolved Jewish national moorings.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

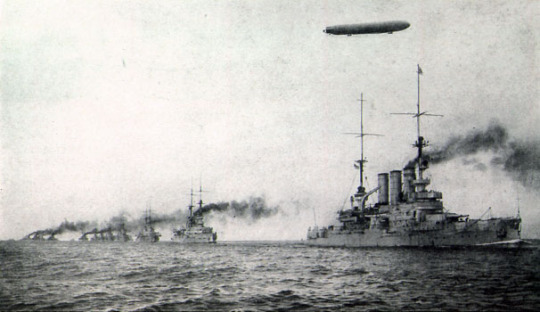

UNA ARMADA CREPUSCULAR: LA MARINA IMPERIAL ALEMANA (1872 – 1919 )

Héctor López Aréstegui

“….Los caminos de hierro nos conducirán solamente con mayor rapidez al abismo”

- François – Rene de Chateaubriand (1768 – 1848)

La guerra se nutre de equívocos y, acaso, el mayor de ellos resulte ser el concepto que la historia le escriben los vencedores. Y es que vencedor y vencido no son categorías absolutas, y que “todos somos vencedores y vencidos al mismo tiempo al describir en nuestros éxitos, pues también exponemos el arduo problema de no olvidar el alcance de nuestras fuerzas[i]”· Creemos que esta frase, tomada del prefacio de las memorias de guerra del almirante alemán Reinhard Scheer (1863 – 1928), describe con justicia el carácter de la guerra naval durante la Gran Guerra y, en particular, la existencia crepuscular de la Marina Imperial Alemana (1872 – 1919), cuya historia merece ser mejor conocida y trascender el alcance de la cita churchilliana que constituye su lapida ante el tribunal de la Historia, “la flota alemana es un lujo, no una necesidad nacional”.

1. ¿Qué es Alemania?

¡Alemania! ¿Qué es Alemania? El gran poeta Johan Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 – 1832) pensaba que era una entelequia en tanto los alemanes no superaran su sempiterna tradición de rivalidad y fragmentación[ii], basculando – desde el siglo XVIII – ora bajo la égida de Prusia, ora a la de Austria. A partir del efecto de las Revolución de 1848[iii], que barrió el orden europeo creado por el Congreso de Viena de 1814 – 1815, Alemania fue tomando forma, a golpes del cincel del nacionalismo, constituyendo la fase final del proceso las guerras de unificación contra Dinamarca, Austria y Francia (1864 – 1871). La victoria sobre Francia en la guerra Franco – Prusiana (1870 – 1871), fue el hecho político – militar que transformó la Confederación de Estados Alemanes surgida de la derrota austriaca de 1866 en el Segundo Reich[iv] alemán, constituyéndose Prusia en su estado director. El 18 de enero de 1871 en Versalles, Francia, iniciábase el proceso de convertir “un mosaico de curiosidades políticas y la idea medieval del Imperio resucitado[v]” en un estado a la par de los paradigmas de la época, Francia e Inglaterra.

El Reich era una idea medieval, difícil de definir y mucho más de traducir al lenguaje político de la época. Bajo su sombra coexistían – desigualmente – principios absolutistas de la monarquía prusiana y los democráticos de la Revolución de 1848. El nuevo Estado era una monarquía federal, “una reunión de Estados, bajo la legal y efectiva hegemonía de un Estado director, que es Prusia. Prusia, al crear con su esfuerzo el gran Imperio alemán, recibió el encargo de dirigirlo, obteniendo con ello ciertos privilegios sobre los demás, principalmente en todo lo relacionado con la política militar y comercial de la Confederación[vi]”. El Bundsrat (Consejo de la Corona) era la cima de su estructura del poder constituido, con competencia exclusiva en materia de defensa, legislación civil y penal, comercio y orden económico; los gobiernos estaduales lo eran para los demás asuntos dentro de sus límites territoriales. La administración imperial recaía en la Cancillería del Reich, que la ejercía el Ministro Presidente de Prusia. Descolgada de esta jerarquía, el Reichstag (Dieta Imperial), de elección popular, servía – en la práctica – de órgano consultivo para los asuntos de competencia del gobierno imperial[vii]. Este esquema de gobierno era el resultado de las maniobras políticas del canciller – ministro presidente de Prusia Otto von Bismarck, para quien la monarquía prusiana tenía el derecho y el deber de dominar el proceso de unidad alemana, lo cual excluía toda forma de gobierno parlamentario que controlara la acción del monarca. Así, pues, el artículo 4 de la Constitución de 1871 establecía que el soberano tenía el derecho “de convocar, abrir, prorrogar y cerrar el Reichstag y el Bundsrat[viii]”.

2. El llamado del mar

La nación alemana estaba obsesionada con sus fronteras, históricamente precarias y expuestas a la presión de sus vecinos. El geógrafo y politólogo sueco Johan Rudolf Kjellén[ix] (1864 – 1922), afirmaba que éstas podían calificarse de malas y eran la fuente de la inseguridad y vacilación de su política exterior e interior. Las postrimerías del siglo XIX añadieron al problema una nueva dimensión: la marítima. En su obra “Las Grandes Potencias de la Actualidad�� (1911) Kjellen describía la situación: “Si se tiene en cuenta los grandes intereses marítimos de Alemania, lo que el Rin ha llegado a representar en el interior del país como vía de comunicación comercial y la riqueza que se levanta sobre sus riberas, se comprenderá cuán penoso ha de resultar para Alemania el no poseer la desembocadura del Rin. En Oriente le pasa a Alemania con el Vístula lo que a los Países Bajos con el Rin: no posee nada más que su curso medio. Con el Rin es Holanda la que le roba a Alemania su natural con el mar; en el Vístula, Alemania es quien le roba la suya a Rusia. Lo mismo sucede algo más con el Este con el Memel; también con este río es Alemania la favorecida, con perjuicio de Rusia[x] ”.

Sin embargo Prusia estaba anclada en el brillo de la gloria de las guerras de unificación[xi]. La guerra era, según la definición uno de los intelectuales más reconocidos de la época, el historiador Heinrich von Treitschke (1834 – 1896), “el medio de grabar en la mente del individuo el binomio patria – nación, a fin de que trascienda de sí mismo y liberte a la nación del destino que había tenido hasta las guerras napoleónicas, ser el campo de batalla de casi todos los conflictos bélicos de Europa”. El almirante Reinhard Scheer (1863 – 1928), que creció en aquel ambiente de exaltado nacionalismo, dejó testimonio de ello en la introducción de sus memorias de guerra: “Del lado opuesto Prusia – Alemania. Toda su historia marcada por la lucha y la angustia, porque las guerras europeas tuvieron lugar preferentemente en su territorio. Era la nación del Imperativo Categórico, presta a las privaciones y al sacrificio, siempre levantándose una y otra vez, hasta que finalmente pareció haber alcanzado el éxito a través de la unificación del Imperio y ser capaz de cosechar los frutos duramente ganados de una posición de poder. La victoria sobre las adversidades solo pudo lograrse gracias a su idealismo y probada lealtad a la Patria bajo la opresión del gobierno extranjero. La fuerza de nuestro potencial defensivo descansaba sobre todas las cosas en nuestra conciencia e integridad adquiridas por la estricta disciplina[xii]”.

Así, al iniciar su andadura como estado unificado, en Alemania no se tenía en consideración la célebre máxima romana “Navegar es necesario, vivir no lo es[xiii]”. Prusia no era consciente de esta verdad porque había vivido casi toda su historia de espalda al mar. Por ser la más pequeña y la más joven de las potencias europeas surgidas de las guerras de religión de los siglos XVI y XVII, sus recursos financieros siempre habían sido escasos y, por ello, sus formaciones navales efímeras. Además, su vecindad con grandes potencias marítimas (Dinamarca, Holanda, Suecia, Francia e Inglaterra) abonaba a favor de la idea de invertir en un poderoso ejército en lugar de una débil armada. El único chispazo de tradición marítima alemana era el recuerdo de la Liga Hanseática (1358 – 1630), una federación comercial y defensiva de ciudades del norte de Alemania y de las comunidades de comerciantes alemanes en el mar Báltico, los Países Bajos, Suecia, Polonia y Rusia. El Margraviato de Brandeburgo – el antecedente medieval de Prusia – apenas participó en esta alianza. Así, mientras el Rey – sargento Federico Guillermo I de Hohenzollern (1688 – 1740) y su sucesor Federico II (1712 – 1786) creaban el ejército modelo del mundo europeo de la Edad Moderna, el dominio del mar se convertía en el elemento clave en la diferenciación entre los estados. No bastaba con proteger las costas de la flota enemiga sino ser capaz de explorar los mares allende de las mismas. La fuente de riqueza de las naciones era el comercio marítimo. Prusia – y posteriormente el binomio Prusia – Alemania a fines del siglo XIX – aún no habían dado ese paso, el cual que elevó – en su momento – a Portugal, España, Francia e Inglaterra como potencias mundiales.

Alemania hubo de esperar a que surgiese una figura que encarnase el llamado del mar. Este personaje fue el príncipe Adalberto de Prusia (1811 – 1873), fundador de la efímera flota de la Confederación de Estados del Norte de Alemania, la Reichsflotte[xiv] (1848 – 1852) y de la Marina Prusiana (1850 – 1867). No es fácil definir la personalidad del príncipe Adalberto, acaso lo más preciso es decir que fue para su patria en una sola persona lo que para Portugal significó el príncipe Enrique el Navegante (1394 – 1460) y para Inglaterra Samuel Pepys (1633 – 1703), el organizador de la Royal Navy. La voz del príncipe era la vocera de muchas otras que recordaban las razones por las que se debía contar con una armada que protegiera permanentemente las costas de invasores, bloqueara los puertos del enemigo en caso de guerra y salvaguardara el comercio exterior en aguas allende del norte de Europa. Convergían con su opinión las ideas de personajes como el economista Freidrich List (1789 – 1846), creador del Sistema de Innovación Nacional – léase, en términos contemporáneos, la Teoría del Desarrollo Económico –, quien señalaba que una flota permanente debía existir por y para un bien común, la defensa y la proyección de la identidad nacional alemana[xv].

La mano creadora de la Marina Imperial Alemana (Kaiserliche Marine) fue la del general Albretch von Stosch (1818 – 1896), quién imprimió en sus acciones un norte claro: una institución de unidad nacional, defensora de soberanía marítima y del comercio exterior. El desafío era inmenso. Corrían tiempos de cambio tecnológico y de la naturaleza jurídica de la guerra en el mar. Los mayores obstáculos eran, como ya lo hemos señalado anteriormente, la posición geográfica de Alemania y la falta de una tradición naval. A su favor Von Stosch contaba con el apoyo político del canciller Bismarck y de un generoso presupuesto para un programa naval de diez años según el cual se construirían ocho fragatas blindadas, seis corbetas blindadas, veinticuatro corbetas ligeras, siete monitores, dos baterías flotantes, seis avisos dieciocho cañoneras y veintiocho torpederos, parcialmente financiado con los pagos que hubo de hacer Francia al Reich como compensación de los gasto de la guerra de 1870 – 1871. En una década (1872 – 1882) Von Stosch creó una armada de la nada, formó a sus oficiales y tripulantes y dotó a Alemania de una industria naval propia. Lo hizo con pragmatismo, consciente de la incertidumbre reinante sobre el futuro del poder marítimo[xvi]. Así, el SMS Hansa (1872) y el SMS Preussen (1873) fueron dos buques exponentes de lo que significaba para Alemania el poder naval: respeto de su soberanía y una garantía para su comercio. El SMS Hansa fue el primer blindado construido en astilleros germanos y pasó la mayor parte de su vida útil en el exterior, protegiendo el comercio alemán. El SMS Preussen fue el primer buque de guerra teutón construido por un astillero privado – el astillero AGVulcan, en Sttetin[xvii] – , patrulló el Mediterráneo oriental durante la guerra ruso – turca (1877 – 1878) y participó en la ceremonia de transferencia del archipiélago de Heligoland al Imperio en 1890. La obra formativa de Von Stosch (1872 – 1882) y su sucesor, el general Leo von Caprivi (1883 – 1888) fue sumamente exitosa y, a fines de 1880, Alemania era la tercera potencia naval de Europa, solo superada en número de unidades por Rusia y la Gran Bretaña[xviii].

Además de crear de una armada, Alemania emprendió la tarea de dotarse de una continuidad litoral entre el Mar Báltico y del Mar del Norte y una plataforma de proyección sobre el Mar del Norte, el archipiélago de Heligoland[xix]. El primer objetivo se alcanzó con la construcción del Canal de Kiel. Las obras se iniciaron en Holtenau, cerca de Kiel, el 3 junio de 1887 y concluyeron ocho años después, el 20 de junio de 1895. El canal medía 62 metros de ancho en la superficie y 22 en el fondo, 9 de profundidad; en honor al monarca que inició el proyecto – Guillermo I, rey de Prusia y primer emperador de la Alemania unida – se le denominó Káiser Wilhem Kanal. No era la primera vez que se vinculaba el Mar Báltico y el Mar del Norte a través de un canal, pero sus predecesores eran, comparativamente, obras modestas. Así, pues, del Canal de Kiel se dijo que era una muestra “del orgullo alemán, pletórico de facultades de invención e imaginación, de iniciativa y de recursos, una audacia avisada y complaciente a la que se rinde homenaje y se sirve de una potencia industrial de primer orden y de personal altamente calificado[xx]”. Asimismo, la adquisición del archipiélago de las Heligoland (1890) – fruto del cuidado que puso el canciller Bismarck en las relaciones diplomáticas con Gran Bretaña – consolidó el dominio marítimo alemán y le dotó de una proyección al Mar del Norte.

3. La influencia de Mahan (1890 – 1897)

En 1888, al iniciar su reinado, el Káiser Guillermo II (1859 – 1941) declaraba con seguridad que “Al Imperio Alemán no le es menester nueva gloria militar ni conquistas, ahora que ha ganado el derecho a vivir como nación unida e independiente”. Esta prudencia fue decayendo a partir de 1890, tras la dimisión de Bismarck a la Cancillería del Reich. El voluntarioso emperador cayó bajo el influjo de las ideas de Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840 – 1914), autor del libro que se consideró como el más influyente de la última década del siglo XIX, “La influencia del poder marítimo en la Historia: 1660 – 1788”. La obra era una compilación de las clases dictadas por el marino norteamericano en la Academia de Guerra Naval de los Estados Unidos.

Mahan señalaba que el control de los mares era el factor más importante para la prosperidad nacional a lo largo de los siglos y que los componentes del poder marítimo de una nación eran los factores geográficos, los recursos naturales, el carácter nacional, el espíritu de su gobierno y su política naval y diplomática. Asimismo, deducía varios principios estratégicos relacionados con la concentración de fuerzas, la correcta elección del objetivo y la importancia de las líneas de comunicación. “La influencia del poder marítimo en la Historia: 1660 – 1788” resumía las razones por las qué una nación debía contar con una Armada cuyo principal objetivo fuera el tener la capacidad suficiente para destruir una flota de guerra enemiga. En Alemania “La influencia del poder marítimo en la Historia: 1660 – 1788” tuvo un gran éxito, constituyéndose el káiser Guillermo II (1859 – 1941) en su mayor propagandista, llegando a decir de él que “No estoy leyendo sino devorando el libro de Mahan y trato de aprovecharlo con el corazón y con la mente. Es un trabajo de primera clase y clásico en todos sus puntos. Está a bordo de mis barcos y es constantemente consultado por mis almirantes y oficiales”.

Sin embargo el Segundo Reich no encajaba con la geografía política que proponía el autor norteamericano. Y es que, tal como decía Kllejen, “Alemania era, en la constelación europea, la menos independiente de todas las potencias mundiales[xxi]”. Consciente de ello, Bismarck se había ocupado de mantener un equilibrio estratégico europeo en beneficio de la prosperidad y estabilidad de Prusia – Alemania y de la dinastía Hohenzollern. Así, al oeste contenía a los franceses y mantenía buenas relaciones con los británicos y, al este, era sumamente cuidadoso y hasta cordial con los rusos. Dicha política exterior le había permitido fortalecer la posición del Reich, dotándole de una costa continua y de una salida independiente al Mar del Norte. Conservador de corazón, Bismarck había dado autonomía al general Von Stosch en el desarrollo del primer programa naval (1872 – 1882), sabiendo que pondría énfasis en la construcción de una Armada protectora del comercio germano y no en experimentos para los cuales Alemania no estaba en condiciones de asumir por falta de recursos políticos[xxii] y económicos[xxiii]. Von Stosch eludió estos escollos y apostó por el torpedo como nivelador de las pequeñas y grandes armadas. Esta nueva arma, desarrollada por el ingeniero británico Robert Whitehead (1823 – 1905) con el apoyo de capitales austro – húngaros, respondía a la pregunta sobre cómo una marina modesta podía defenderse de una armada más poderosa.

4. La daga en la garganta de Inglaterra

El programa de torpedos de la Armada Imperial estaba en manos de un oficial quien había sido influenciado hondamente por las ideas de Mahan, Alfred Tirpitz (1849 – 1930). A pesar de haber sido promovido por Von Stosch, Tirpitz cuestionaba la misión que le había impuesto Von Stosch a la Marina Imperial. Para Tirpitz “la bandera debía seguir los pasos del comercio, como otros países habían visto antes de que nosotros nos diéramos cuenta[xxiv]”. Así, al asumir el cargo de Secretario de Estado en el despacho de la Administración Naval Imperial en junio de 1897, Tirpitz dio un golpe de timón presentando al káiser el proyecto de una gran flota de combate cuya realización implicaba graves consideraciones políticas y diplomáticas, porque constituía un peldaño más en la escalada de militarización de la política exterior y de seguridad nacional. Construir una gran flota era entrar en competencia directa – y, eventualmente, en conflicto abierto – con la Gran Bretaña por “el lugar bajo el sol”[xxv] que, según Tirpitz, le negaban los británicos a los alemanes.

Tirpitz pensaba que el flanco estratégico más desprotegido de los británicos era el Mar del Norte. La Marina Real privilegiaba el teatro de operaciones del Mediterráneo y el despliegue de sus unidades como gendarmes de las colonias y el comercio británico. Según Tirpitz, los británicos negociarían con Alemania un acuerdo sobre construcciones navales con el fin de mantener su presencia naval en el Mediterráneo y del resto del mundo. Por ello la Gran Flota Alemana debía ser una fleet in being (escuadra en potencia), es decir, una amenaza constante a la hegemonía naval británica. En medios periodísticos esta estrategia recibió un nombre más amenazante y perturbador, “la daga en la garganta de Inglaterra” que la prensa británica asumió y utilizó para advertir al gobierno y al pueblo del peligro alemán y de la complaciente política de esplendido aislamiento frente a los asuntos europeos.

La estrategia de Tirpitz se fundaba en supuestos erróneos. El Reino Unido no vaciló en responder al reto e inició un programa naval que duplicó en una década la tasa de construcciones navales alemanas y reorganizó su sistema de defensa global gracias al apoyo político y económico de sus dominios, Canadá, Australia, Nueva Zelanda, la India y África del Sur. En vísperas de la Gran Guerra, Inglaterra había triplicado su ventaja en el juego de correlación de fuerzas. En Alemania echaban raíces las dudas sobre la capacidad de la Armada Imperial para enfrentar a la Royal Navy y la validez de la idea de pretender hacer la guerra contra Inglaterra[xxvi]. La guerra ponía en peligro la prosperidad alcanzada por la marina mercante alemana. La divisa de la compañía naviera Hamburg – Amerika – Line – “mi campo es el mundo” – era una realidad de la que se enorgullecían todos los alemanes. Su director Albert Ballin (1857 – 1918) era consejero del káiser y mediador en las sombras en las crisis diplomáticas entre Inglaterra y Alemania gracias a su amistad con el consejero privado del rey Eduardo VII (1841 – 1910), sir Ernst Cassel (1852 – 1921). Siendo el principal armador de Alemania, Ballin temía por la seguridad de la flota mercante alemana y la pérdida de su posición preeminente en el comercio mundial. En 1914 era Inglaterra quien tenía preparada la daga para, cuando estallara la guerra, encajarla en la garganta de Alemania a través de un bloqueo a distancia aprovechando las desventajas geográficas del litoral germano. Asimismo, su presencia naval global borraría del mapa los buques mercantes alemanes[xxvii].

5. Tiempo de pruebas

En vísperas de la Gran Guerra la Flota de Alta Mar Alemana se encontraba en una situación política sumamente complicada. Tras una década del gozar el favor imperial (1897 – 1908), las críticas comenzaron a llegar de todos los sectores políticos, incluso entre los nacionalistas que veían en el almirante Tirpitz encarnados todos los defectos de un estamento político – militar débil, elitista, ciego a las demandas de la nación y reaccionario. Las críticas más feroces venían del grupo que había sido el puntal del programa de Tirpitz, la Deutscher Flottenverein[xxviii] (Liga Naval Alemana) (DFV). Era irónico que esta institución, creada como freno al parlamentarismo y al Partido Social Demócrata (SPD), pasara a ser una feroz opositora de Tirpitz. El nacionalismo que había insuflado y sostenido la construcción de la Armada Imperial se escapaba del control del Reich. El SPD aprovechó la crisis de confianza en Tirpitz para cuestionar la política global del káiser y del nacionalismo y ganar predicamento más allá de su electorado tradicional, la clase trabajadora.

Atrapada entre dos fuegos, el nacionalismo desbocado y la prédica pacifista y antiimperialista del SPD, la Armada Imperial fue señalada por unos de bajar la cabeza ante los británicos y, por otros, de ser la responsable de las tensiones diplomáticas anglo – alemanas. La guerra estalló en plena crisis de credibilidad y ante ella el alto mando naval no tuvo otro camino que el de la improvisación. En este marco, “Alemania vio en el submarino un rayo de esperanza en el acoso mundial a que se encontraba sometida y apeló a él como pudo apelar al rayo de la muerte[xxix] si éste se hubiese inventado. Los aliados disponían de la hegemonía marinera tal y como se entendía hasta entonces, en el concepto clásico de la guerra marítima, de la guerra que hasta entonces era guerra plana. El submarino era la guerra en el espacio, completando el avión esta transformación que no es que origine una guerra nueva, como creen, o fingen creer, unos cuantos futuristas, pero que desde luego introduce otras modalidades como ha acaecido siempre desde que un arma o un adelanto sensacional ha cambiado los puntos básicos del planteamiento del problema[xxx]”.

Asimismo, Alemania se lanzó a una guerra de guerrillas en el mar (Kleinkriegs) utilizando corsarios cuyas hazañas y desventuras constituyen episodios apasionantes del desarrollo de la guerra naval como la del Westburn, en el Archipiélago Canario, en aguas españolas, es decir, en territorio de un estado neutral. Sobre ella, El Comercio informaba el 02 de junio de 1916 lo siguiente: “Acaba de llegar el vapor inglés Westburn, izando la bandera de guerra alemana, bajo el mando del oficial de marina Badewitz, llevando a bordo las tripulaciones de los vapores ingleses “Flamenco”, “Horace”, Edimborough”, “Clan Mactavish” y el belga “Luxemburg”, todos hundidos por el comandante alemán. El “Westburn”, cargado de carbón, fue apresado en su viaje de Inglaterra a Buenos Aires. Las tripulaciones de los cinco vapores serán puestas a disposición de sus respectivos cónsules.

El “Westburn” entró en el puerto de Santa Cruz [de Tenerife], mientras que un crucero inglés se hallaba anclado en la rada. Es de grandísimo interés hacer constar el hecho de que el vapor que acaba de fondear en [Santa Cruz de] Tenerife, tenía 199 prisioneros ingleses, mientras que la tripulación estaba constituida por sólo siete alemanes (…)

Mientras las tripulaciones de los barcos alemanes surtos en el puerto aclamaban a la heroica tripulación del “Westburn”, en cuyo palo mayor había sustituido la bandera británica por el pabellón alemán, abandonó la bahía el crucero inglés HMS “Sutlej”, cuya situación resultaba un poco ridícula. El “Sutlej” quedó vigilando, fuera de la bahía, en espera de que al transcurrir las veinticuatro horas de su entrada, en Tenerife, abandonará el puerto el “Westburn”, para entonces cazarlo o hundirlo a cañonazos (…)

Al cumplirse las veinticuatro horas de su llegada al puerto, el “Westburn”, a cuyo bordo no quedaba ni uno solo de los tripulantes y pasajeros que traía prisioneros, levó anclas y enfiló la salida del puerto. Los muelles y las alturas estaban repletos de curiosos que se disponían con gemelos y anteojos de largo alcance a presenciar qué iba a ocurrir en el mar tan pronto como el crucero “Sutlej” pudiese atacar a los corsarios alemanes.

El “Westburn”, con su corta tripulación germana, y arbolando el pabellón de guerra del imperio, salió valientemente fuera de la bahía. La expectación era extraordinaria, se había tocado zafarrancho de combate. Tan pronto como salió a la mar, el crucero británico se puso en movimiento para darle caza. El oficial alemán, que con sus siete hombres iba a bordo del “Westburn”, no se proponía escapar. Antes, al contrario, puso proa en demanda del enemigo y hacia él dirigió el buque capturado. Se detuvo entonces el crucero y rectificando su rumbo parecía aceptar el reto de los alemanes. Todo el mundo esperaba el primer cañonazo cuando, al costado del “Westburn”, se destacó un bote, en el que iban los marinos alemanes. El crucero inglés avanzó entonces, forzando la máquina pero una violenta y larga explosión a bordo del “Westburn” dio a entender a los marinos ingleses que se habían burlado de ellos nuevamente volado la presa en sus mismas narices. Los valerosos germanos ganaron rápidamente el puerto de Tenerife entre las aclamaciones de todos los que presenciaban la hazaña, Allí afuera quedaban los marinos ingleses devorando su fracaso. Los alemanes desembarcaron en el muelle, y seguidos del público que les felicitaba se presentaron antes las autoridades[xxxi]”.

No es nuestra intención ocuparnos del combate de Jutlandia (31 de mayo – 1 de junio de 1916), basta decir que fue un choque inútil: los británicos no aniquilaron a la Flota de Alta Mar Alemana y, ésta, a su vez, no pudo romper el bloqueo británico y justificar su existencia. Un comentarista español contemporáneo, Mariano Rubio y Bellve, concluía que “El problema en el mar queda planteado, después de la batalla, en los mismo términos que antes que ella. Solamente la muerte, con numerosas víctimas de la horrible tragedia de Jutlandia, es la que ha triunfado en toda línea[xxxii]”. Evidentemente Alemania reclamó para sí el resultado del combate como una victoria táctica, pero lo cierto es que no había variado la situación estratégica de Alemania. Un corresponsal del Daily Telegraph la resumía así: “La verdad es que, como isleños, no ignoramos lo que son los mapas de guerra, pero damos más importancia a los mapas sancionados por el tiempo. Olvida Von Bethmann – Hollweg que cerca de tres cuartas partes de la superficie de la Tierra están cubiertas de agua. Cuando se iniciaron las hostilidades, comenzaba una lucha mundial para los alemanes, que habían demostrado actividad en los mares y estaban practicando o preparando operaciones guerreras no sólo en cada de uno de los continentes, sino también en todos los países del globo. Para los germanos esto no es ya actualmente una guerra mundial. Alemania se halla casi tan completamente aislada del mundo exterior, como París en 1870. Aunque Alemania haya gastado 7,250 millones de francos en su Marina, y aunque tenía la primera marina mercante del mundo después de la británica, sin embargo la bandera germana ha desaparecido del mar, resultado singular para una nación marítima.

Durante varios siglos la guerra marítima, en la que se hallaron comprometidas las flotas de España, Holanda y Francia, nunca ocurrió que no mostraran sus banderas en el mar; pero la marina mercante alemana ha desaparecido; la marina de guerra está inactiva, el comercio transatlántico ha cesado y han desaparecido las colonias. Alemania no ha alcanzado victorias como las conseguidas por Napoleón en 1811, pero Trafalgar preparó Waterloo. El canciller alemán debe leer la vida de Napoleón[xxxiii]”.

La Hochseeflotte no tendría una segunda oportunidad de medir fuerzas con la Royal Navy. Sus pérdidas habían sido menores que las británicas, pero eran irremplazables. Ya no podía disputar el dominio del mar. Al respecto escribió Mateo Mille: “Pero Alemania no era una nación naval; la formidable potencia creada por el almirante Von Tirpitz, organizador genial al amparo de una industria colosal, no fue empleada adecuadamente[xxxiv]”.

En el invierno boreal 1916 – 1917 la moral de la flota se fue a pique. Como todos los alemanes, el fracaso de la cosechas hizo más severo el racionamiento alimentario. Las magras raciones potenciaron elementos como la inactividad, las rutinas sin sentido y el desprecio de los oficiales. En junio de 1917 una manifestación contra los privilegios alimentarios de los oficiales se tornó en una plataforma política a favor de una paz negociada. Los líderes del comité de marinos fueron detenidos. Dos de ellos fueron fusilados[xxxv]. En julio un alzamiento armado en las bases navales de la costa de Flandes dejó un saldo de cincuenta oficiales asesinados y la destrucción de las instalaciones de los zeppelines. Su líder, el segundo teniente Rudolf Glatfelder, declaró después, ya a salvo en Suiza, que este hecho probaba la capacidad de los alemanes para rebelarse[xxxvi]. En diciembre el desacato a la orden de reembarque de la dotación de buques de vigilancia que acababan de regresar de una larga y sangrienta patrulla degeneró en motín que fue develado con un saldo de cuarenta y cuatro muertes. Los sobrevivientes fueron condenados a trabajos forzados[xxxvii].

El descontento también cundía en el cuerpo de oficiales. Von Tirpitz hubo de renunciar a la Secretaria de Marina en marzo de 1916, a causa de su postura favorable a la guerra submarina irrestricta[xxxviii]. Pocos meses después se convirtió en co – fundador del Partido de la Patria Alemana (DVP), un movimiento político nacionalista opuesto a una paz negociada. Corría el año 1918 y el poder real – el gobierno que apoyaban Von Tirpitz y sus correligionarios – era el de los caudillos del pueblo alemán, el mariscal de campo Paul von Hindenburg y el general Erich Ludendorff. En mayo de 1918 corrían fuertes rumores sobre la existencia de círculos secretos de oficiales conspirando contra Von Capelle y Scheer, con el fin de sacar de los puertos a la Hochseeflotten y combatir contra los ingleses[xxxix]. A finales de julio el crítico naval del Berliner Tageblatt, capitán de navío (r) Karl Ludwig Lothar Persius (1864 – 1944) declaraba abiertamente el fracaso de la guerra submarina[xl].

El 29 de setiembre de 1918 el alto mando del Ejército alemán reclamó al gobierno imperial el inicio de negociaciones para un armisticio con los aliados. Cuatro días después el nuevo gabinete, con el príncipe Max de Baden a la cabeza[xli], enviaba una nota al gobierno de los Estados Unidos solicitando el armisticio sobre la base de los Catorce Puntos del presidente Woodrow Wilson.

Entretanto el ejército y la marina imperial se ocupaban de los efectos de la derrota. El alto mando militar hábilmente inició una campaña de propaganda entre las tropas del frente. Esta fue el origen del mito de la “puñalada por la espalda”, en el cual se apoyarían los partidos de extrema derecha durante la República de Weimar, en particular los nacionalsocialistas. Entre la oficialidad naval las células nacionalistas clandestinas salieron a la luz y, en contra de la voluntad de paz del gobierno Baden, sus integrantes dictaron las órdenes pertinentes para el alistamiento de la Flota para forzar el combate decisivo contra la Armada británica. El 28 de octubre la marinería de Kiel y Wilhelmshaven se amotinaron, utilizando como pretexto el nivel crítico al que había llegado el racionamiento de las dotaciones. Cinco días después Kiel – la capital de la Armada imperial – era escenario de manifestaciones en las que se exigía, además de la mejora del rancho, la reforma política y la libertad de los encarcelados por los motines de 1917. El temor de que el motín fuese develado a sangre y fuego, al estilo de la sublevación en Flandes, ocurrida el verano pasado, dio motivo a los amotinados para armarse y organizarse en soviets. Así, pues, el pabellón imperial fue arriado e izada la bandera roja. El motín fue controlado por la moderación de las autoridades navales y la intervención del diputado socialista Gustav Noske, hombre de autoridad y sentido práctico. No hubo violencia contra los oficiales y los amotinados fueron licenciados, dispersándose por toda Alemania. Guillermo II seguía los acontecimientos desde el cuartel general del Ejército Imperial en Spa (Bélgica). Conmocionado, declaró que ya no tenía una marina y abdicó. En aquella hora amarga Guillermo II dijo: “Espero que esto será en beneficio de Alemania. No desesperemos por el porvenir”. Una vez más se había repetido un viejo axioma sobre los motines navales: estos se producen en las flotas que permanecen ancladas en puerto, y son mayormente consecuencia de una derrota.

6. Ocaso

El 15 de noviembre de 1918 el almirante alemán Hugo Meurer (1869 – 1960) firmaba con su par británico, Jellicoe, las clausulas del acuerdo de internamiento de la flota imperial. Tres días después el almirante Ludwig von Reuter (1869 – 1943) asumía el mando de la escuadra de buques destinados al internamiento provisional en Escocia. Conformada por diez acorazados, siete cruceros ligeros y cincuenta destructores, su derrota hacia Escocia tuvo un aire que recordaba tiempos convulsos, pues cada buque ondeaba dos enseñas, la imperial a popa y la bandera roja en el palo de proa. El lugar definitivo de internamiento fue Scapa Flow, la base de la Grand Fleet británica, en el archipiélago de las Orcadas. Durante las negociaciones del Tratado de Versalles los buques permanecieron fondeados y severamente custodiados, a tal punto que sus tripulaciones se encontraban incomunicadas y prohibidas de tocar tierra.

En vísperas de la culminación de las negociaciones de paz en París, a fines de junio de 1919, el Times de Londres informaba que los aliados habían acordado exigir a Alemania la entrega de los buques internados a través de un arreglo financiero. En caso que la respuesta germana fuera negativa, correrían tres días de plazo para la denuncia del armisticio del 11 de noviembre de 1918 y, con ello, la reanudación de hostilidades. Con la convicción que el destino de la flota internada era la de trofeo de guerra, el almirante Von Reuter activó el plan de hundirla. Aprovechando un descuido de sus custodios, los alemanes abrieron los grifos de fondo de los buques y arriaron los botes salvavidas. En cinco horas se fueron a pique diez acorazados, cinco cruceros de batalla, cinco cruceros ligeros y cuarenta y cuatro destructores. Un crucero de batalla, cuatro cruceros ligeros y catorce destructores fueron embarrancados por personal británico. Ludwig von Reuter había protegido, in extremis, el honor de la flota[xlii].

La Hochseeflotte pudo haber tenido un final diferente si se hubiera prolongado la guerra. En setiembre de 1917, el almirante David Beatty (1871 – 1936), comandante de la Gran Flota, autorizó un audaz plan según el cual 121 aviones del Real Servicio Aéreo Naval (RNAS) destruirían la Hochseeflotte y sus bases de Kiel y de Wilhemshaven[xliii]. Los torpederos despegarían desde porta aeronaves – – y los hidroplanos – bombarderos desde sus bases del Canal de la Mancha. Este plan de ataque sirvió de modelo para el bombardeo de la flota italiana surta en Tarento, Sicilia, el 11 de noviembre de 1940.

7. A modo de conclusión

En su biografía de juventud “Historia de un alemán. Memorias 1914 – 1933” el periodista alemán Sebastian Haffner (1907 – 1999) escribió: “Esta enfermedad – el nacionalismo – que en otros casos sólo afecta el aspecto externo, en el suyo – los alemanes – les carcome el alma (…) Un alemán que cae víctima del nacionalismo deja de ser alemán, apenas es persona. Y lo que este movimiento genera es un imperio alemán, quizás incluso un gran imperio alemán o un imperio pangermánico y la consiguiente destrucción de Alemania”. Considero que esta reflexión personal de Haffner puede aplicarse a la existencia de la Marina Imperial alemana. Su carácter nacionalista debe comprenderse como una imitación del sentimiento nacional de los ingleses y franceses de su época[xliv]. Al imitar se corre el peligro de tomar los defectos ajenos[xlv]. ¿Necesitaba Alemania una Armada como la concebida por la ambición del almirante von Tirpitz? Creemos que no. Incluso el káiser Guillermo II (1859 – 1941) declaró, en un momento de lucidez, que la seguridad del Imperio no descansaba en nuevas conquistas[xlvi]. En 1871 Alemania había ganado el derecho a vivir como nación unida e independiente. En 1888 contaba con una Armada digna de respeto, garantía de su soberanía e, incluso, con un modesto imperio colonial. En 1918 Alemania perdió todo lo ganado y sus marinos se amotinaron para salvar sus vidas, porque no querían ser sacrificados en un combate inútil[xlvii]. En cuanto a Scapa Flow, este hecho fue una tragedia redentora para una Armada destruida moralmente. El almirante Von Reuter y sus oficiales demostraron que todo se había perdido, menos el honor.

Scapa Flow fue el último acto de un fracaso que se recuerda con una cita churchilliana, “la flota alemana es un lujo, no una necesidad nacional”. Creemos que dicha frase es equívoca. Al dotarse de una Armada poderosa, Alemania demostró su voluntad de ser un pueblo fuerte y con vocación marítima. Equívocamente se creyó que la libertad de los mares sólo podía alcanzarse por medio de la fuerza. Aquel dogma era propio de la época y la derrota alemana probó su falsedad arrastrando en su magnitud a su poderosa adversaria, Inglaterra, a la luz del impacto humanitario que provocó el bloqueo de las costas alemanas. El orgullo y la ambición desmedida fueron la perdición de la Marina Imperial Alemana. Sus virtudes fueron el valor y la pericia de los tripulantes de submarinos, destructores y cruceros auxiliares. Aquellos que servían a bordo de los dreadnoughts y cruceros de batalla no tuvieron la oportunidad de demostrar su calidad. La obra de construir una flota como la Armada Imperial fue extraordinaria. En ella vemos la maestría y las debilidades de sus artesanos, Von Stosch, Von Caprivi y Von Tirpitz.

REFERENCIAS

[i] “But we are victors and vanquished at one and at the same time, and in depicting our success the difficult problem confronts us of not forgetting that our strength did not last out to the end”

[ii] Desde los tiempos de Julio César Germania – Alemania fue considerada más que un pueblo, una vasta comunidad que habitaba en un territorio pobre y peligroso.

[iii] Serie de motines, sublevaciones e insurrecciones que estallaron en toda Europa, en las que se mezclaron motivos políticos, sociales y nacionales que puso fin al predominio del absolutismo en el continente europeo desde el Congreso de Viena de 1814 – 1815. Se inició el 12 de enero de 1848 en Reino de las Dos Sicilias y llegó a Prusia dos meses después, extendiéndose por toda Alemania a partir del mes de mayo, con la constitución del Parlamento Federal de los Estados Alemanes. La asamblea se dividió entre los representantes partidarios de la Gran Alemania (con Austria) y los de la Pequeña Alemania (sin Austria). Si bien la Asamblea se desintegró el 28 de abril de 1849, a causa de la negativa del rey de Prusia, Guillermo IV, de aceptar la corona imperial de una asamblea revolucionaria, dejó claramente planteada la cuestión de la unidad alemana bajo la hegemonía prusiana o austriaca.

[iv] El término Reich procede de una fusión ecléctica del Rix celta y el Rex latino, razón por la que se tradujo como imperio.

[v] FYFFE, Charles Alan (1845 – 1892), Historiador y periodista británico, corresponsal del Daily News durante la guerra franco – prusiana.

[vi] DOMINGUEZ RODIÑO, Enrique (1918, 13 de marzo), “Las Grandes Potencias: Alemania V”, La Vanguardia, Barcelona, p. 12

[vii] TENBROCK, Robert Hermann, “Historia de Alemania”, Paderborn: Hueber – Schöning, 1968, 344p, p. 218

[viii] PARK, Evan (2015), “The Nationalist Fleet: Radical Nationalism and The Imperial German Navy from Unification to 1914”, Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Volume 16, issue2, p. 125 – 159, p. 136

[ix] KLLEJEN, Johan Rudolf ((1864 – 1922), Geógrafo, politólogo y político sueco. Fue catedrático de ciencias políticas y estadística de las universidades de Gotemburgo y de Upsala. En 1899 acuñó el término “Geopolítica”.

[x] DOMINGUEZ RODIÑO, Enrique, (1918, 6 de febrero), “Las Grandes Potencias: Alemania II”, La Vanguardia, sección “La Guerra Europea”, p. 9

[xi] “Sólo en la Guerra se forja una nación. Sólo las grandes acciones comunes en nombre de la patria unen a la Nación. El individualismo cede y el individuo se difumina y se convierte en parte de un todo” – Heinrich von Treistchke

[xii] Online edition of Admiral Reinhard Scheer’s WW1 memoirs, published in 1920 http:// www.richthofen.com/scheer

[xiii] Esta frase, según el filosofo e historiador romano Plutarco (46/50 DC – 120 DC), había sido pronunciada por el caudillo Pompeyo (106 AC – 48 AC) arengando a sus marineros a embarcarse a pesar del amenazador estado de la mar, recordándoles que el deber está por encima de cualquier miedo o de cualquier circunstancia.

[xiv] La Reichsflotte (Flota Imperial) fue la primera marina unificada alemana. Fue creada el 14 de enero de 1848 por la Asamblea Nacional Alemana de Fráncfort, con el fin de contar con una fuerza naval en la Primera Guerra de Schleswig (1850 – 1852) contra Dinamarca. La fecha de su creación se considera, simbólicamente, como el inicio de la Armada alemana moderna. Ver: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reichsflotte

[xv] PARK, Evan (2015), “The Nationalist Fleet: Radical Nationalism and The Imperial German Navy from Unification to 1914”, Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Volume 16, issue 2, p. 125 – 159, p. 131 – 132

[xvi] “Necesitamos buques que sean apropiados para proteger a la marina mercante ofensivamente y escuadrones que estacionemos para fines de policía en lugares distantes. Considero que los acorazados son un error; son superfluos para nuestras condiciones porque no podemos combatir en un combate de largo aliento” – Albert von Stosch

[xvii] Actualmente Szczecin, Polonia

[xviii] El artículo 53 de la Constitución Imperial de 1871 decía que la Marina del Imperio se encontraba al mando del Emperador, correspondiéndole ocuparse de su organización y composición.

[xix] RUBIO Y BELLVE, Mariano (1916, 22 de octubre), “El Canal de Kiel”, La Vanguardia, Sección “La Guerra Europea”,

[xx] « Des facultés d’invention et d’imagination, un esprit d’initiative et de ressources une hardiesse avisée et souple auxquels il faut rendre hommage, servis admirablement par une puissance industrielle de premier ordre (…) et le dévouement passionné d’un personnel d’élite » GRANDHOMME, Jean – Noel, « Du pompon à la plume: l’amiral, commentateur de la guerre et de la paix d’inquiétude, 1914 – 1919 », Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains, 2007/3 Nº227, p.43 – 64 DOI :10.3917/gmcc.227.0043, p. 53

[xxi] DOMINGUEZ RODIÑO, Enrique, (1918, 6 de febrero), “Las Grandes Potencias: Alemania II”, La Vanguardia, sección “La Guerra Europea”, p. 9

[xxii] La ventaja de contar con el favor imperial constituyó, a la larga, al problema para la consolidación de la cadena de comando de la Armada.

[xxiii] A diferencia de Inglaterra, la Alemania imperial nunca tuvo un apoyo tributario que le permitiera con una fuente de financiación estable y permanente de su Armada. La Royal Navy disfrutaba de los ingresos producidos por una serie de impuestos y tasas al comercio colonial .

[xxiv] SCHEER, Reinhard (1920), “Germany’s High Seas Fleet in the World War”, Cassell & Co,, p. 176

[xxv] Esta frase es el elemento central del discurso del ministro de relaciones Exteriores, Bernhard von Bülow, del 6 de diciembre de 1897, en el cual anunció el golpe de timón de la política exterior alemana, de la política europea de Bismarck (europapolitik) a la global del káiser Guillermo II (Weltpolitik), es decir, del balance de poderes en Europa a la expansión mundial del poderío alemán.

[xxvi] En sus memorias Tirpitz niega que su intención fuera ir a la guerra contra Inglaterra. Por lo contrario, señala que la Armada Imperial tenía un carácter defensivo contra las intenciones bélicas de los británicos, amén de darles unas cuantas lecciones en política internacional.

[xxvii] La Vanguardia (29 de noviembre de 1914), página 16, segunda columna: “Londres, 28 – La Oficina de Trabajo ha publicado a los efectos de la guerra sobre las marinas mercantes inglesa y alemana. De dicho informe se desprende que el 97 por cien de los buques ingleses siguen prestando servicios mientras el 89 por cien de los alemanes han dejado de prestarlo, y que la mayoría de los que navegan son pequeños buques de cabotaje”

[xxviii] Fundada en 1898, la DFV – se definía “como una muestra de concordia entre el trabajador y el príncipe, la izquierda y la derecha, el norte y el sur, un movimiento popular fundado en el amor a la patria, sin distinción de ideas políticas y religiosas ni barrera social alguna”.

[xxix] El rayo de la muerte o rayo de tesla es un arma que permite disparar un haz de partículas microscópicas hacia seres vivos u objetos para destruirlos. Supuestamente fue inventado entre la década de 1920 y 1930 de manera independiente por Nikola Tesla, Edwin R. Scott y Harry Grindell Matthews, entre otros. El aparato nunca fue desarrollado, pero ha alimentado la imaginación de muchos autores de ciencia ficción y ha inspirado la creación de conceptos como la pistola de rayos láser, utilizada por héroes de ficción como Flash Gordon. Ver: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rayo_de_la_muerte

[xxx] MILLE, Mateo, “Historia Naval de la Gran Guerra 1914 – 1918”, Barcelona: Inédita Editores, SL, 2010, 548 p., p. 123

[xxxi] El Comercio (02 de junio de 1916), edición de la mañana, página 4, tercera y cuarta columnas

[xxxii] RUBIO Y BELLVE, Mariano (1916, 11 de junio), “En el mar”, La Vanguardia, sección “La Guerra Europea”, p. 14, 1 – 4 Col.

[xxxiii] La Vanguardia, (29 de mayo de 1916), página 6, tercera columna

[xxxiv] MILLE, Mateo, “Historia Naval de la Gran Guerra 1914 – 1918”, Barcelona: Inédita Editores, SL, 2010, 548 p., p. 11

[xxxv] PATERSON, Tony, (2014, 17 de junio), “A History of the First World War in 100 moments: My dear parents, I have been sentenced to death…”, The Independent

[xxxvi] La Vanguardia (20 de octubre de 1917), página 13, primera columna

[xxxvii] La Vanguardia (26 de enero de 1918), página 9, tercera columna

[xxxviii] El Comercio, (23 de marzo de 1916), edición de la mañana, página 1, tercera y cuarta columnas

[xxxix] La Vanguardia, (18 de mayo de 1918), página 9, cuarta columna

[xl] La Vanguardia (28 de julio de 1918), página 13, primera columna

[xli] El 03 de octubre de 1918 marca el inicio de una de serie de gobiernos concebidos entre cábalas y motines. La política alemana no se estabilizó hasta el año 1922, tras el asesinato del ministro de relaciones exteriores, el industrial Walter Rathenau (1867 – 1922). Su muerte unió, brevemente, a la mayoría silenciosa contra los radicalismos políticos.

[xlii] Fue testigo de estos hechos Claude Stanley Choules (1901 – 2011), el último de los últimos veteranos británicos de la Primera Guerra Mundial

[xliii] WILKINS, Tony (2015, 03 de agosto), “World War I’s abandoned Pearl Harbour Attack”, Ver: http://defence of the realm.wordpress.com/2015/03/08/world-war-Is-abandoned-pearl-harbour-attack/

[xliv] “Repróchese a los alemanes el que imiten unas veces a los ingleses y otras a los franceses, pues es lo mejor que pueden hacer. Reducidos a sus propios medios nada sensato podrían ofrecernos”.

[xlv] “¡Bienaventurados nuestros imitadores, porque de ellos serán nuestros defectos!” – Jacinto Benavente, dramaturgo español (1866 – 1954)

[xlvi] Al Imperio Alemán no le es menester nueva gloria militar ni conquistas, ahora que ha ganado el derecho de vivir como nación unida e independiente” – Guillermo II (1888)

[xlvii] “Alemania en sí no es nada, pero cada alemán es mucho por sí mismo” – Goethe (1808)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Heinrich von Treitschke in the late 19th century, explaining the effects of war on the people:

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

sigh

alright fuck it here we go

according to the book Hamlet On A Hill: [very very long title] edited by Martin F. J. Baasten, August Ludwig von Schlozer used the term "Semitic Languages" in a 1787 essay, but in 1710 Gottfreid Wilhelm Leibniz allegedly had attempted to categorize world languages into categories based on the sons of Noah: Ham, Shem, and Japheth. there's a lot of academic discourse as to whether Leibniz coined the term or not but either way this was the 1700s. remember this.

according to Anti-semitism: A History and Psychoanalysis of Contemporary Hatred by Avner Falk (Israeli psychologist), as well as The Jewish Question: Biography of a World Problem by Alex Bein (German Jewish historian), in 1860 Czech* Jewish talmudist Moritz Steinschneider criticized Ernest Renan- French historian and scholar- for his "antisemitische vorurteile", his antisemitic prejudices, as Renan had proposed Aryan races were superior to Semitic races.

*ethnically Bohemian, culturally Austrian

according to The History of Anti-Semitism, Vol. 3: From Voltaire to Wagner by Leon Poliakov, Heinrich von Treitschke- Prussian or German but honestly who fucking cares because he's a nationalist imperialistic asshole who declared Africans inferior to Caucasians [a note on that later actually]- coined the phrase used by the nazi propaganda newspaper Der Stürmer, "Die Juden sind unser Unglück!", or "Jews are our misfortune". Falk also indicated in his book that Renan & Treitschke both regularly used the term Semitic, but while Renan used it to denote the Arabs, Hebrews, Canaanites, Akkadians, Phoenicians, etc, Treitschke used it to refer to Jews specifically. this is supported by Roots of Hate: Anti-Semitism in Europe before the Holocaust by William Brustein.

Jonathan Hess, author of Johann David Michaelis and the Colonial Imaginary: Orientalism and the Emergence of Racial Antisemitism in Eighteenth-Century Germany, quotes: "When the term "antisemitism" was first introduced in Germany in the late 1870s, those who used it did so in order to stress the radical difference between their own "antisemitism" and earlier forms of antagonism toward Jews and Judaism."

now let's talk about journalist Wilhelm Marr. he used semitismus and judentum to mean the same thing, and his prejudice against the jews was not based upon them based on their religion, but on how he perceived them culturally as a people. he is the one who coined "Antisemitismus", antisemitism. similarly to Lovecraft, his works centered around the concept of Jews "infiltrating" German culture.

James Murray, editor for the Oxford English Dictionary added Anti-Semitism to the English lexicon "officially" ie in the dictionary, indicated that he'd have done so sooner than 1881 since he thought fruitlessly that antisemitism would just blow over.

anti-semitism has always been used to indicate prejudice against specifically jews rather than the semitic peoples as a whole. however, so has antisemitische. they both mean the same thing. however as social trends go, the term semite was eventually used to separate jews from humanity, to "other" them in order to further exacerbate discrimination against them. because of advancements of cultural linguistics the hyphenated term has acquired negative connotations due to, well, the fuckin holocaust.

one last note to touch upon, about Göttingen? Johann Gottfried Eichhorn, a colleague of A L Schlozer, who regularly used Semitic as a term from an academic standpoint? he was also a colleague of Christoph Meiners and Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, the men who coined the term Caucasian. now an unfortunate lesson in the linguistics of human taxonomy, the term Caucasoid was used to separate from, uh... *tugs collar* Mongoloids and Negroids. :/ at the time many european scholars believed that Noah's Ark had landed after the flood in the Caucasus mountains, which is coincidentally where Prometheus crafted humans from clay (i'm legit learning that right now what the fuck). Meiners/Blumenbach both ranked Caucasians as being higher in both mental and physical capacities than both the Mongols and Negros, and measured them in difference by cranial measurements and bone morphology and skin pigmentation. which is, uh. fucked up. so yeah maybe Göttingen is not where we should derive ANY ethnic studies from because like. yikes.

regardless, there is no historical evidence that "german scientists coined antisemitism to replace judenhass" as op has indicated. it's all from historians, linguists, and journalists. 🙄

however, using the term Semitic in any context besides pre 18th/19th century academia is, uh. should we say... big oof? what with hitler n shit. jews don't like it. so maybe we drop the hyphen out of respect to the people who are alive now rather than clinging to old traditions of dead racist white men. ITS LITERALLY SHORTER TO SAY ANTISEMITE THAN ANTI-SEMITE. BRUH. doesn't matter than they both mean essentially the same thing or that hebrew-speaking jews technically are semitic from a purely linguistic standpoint, what matters is the respect.

so yeah, don't use the hyphen.

but also maybe don't spread misinformation on Tumblr?

RESEARCH TWEETS BEFORE YOU REBLOG THEM PLEASE JFC

I literally just accidentally reblogged a tweet from 2019 about a youtube boycott because I didn't look carefully at the dates. research the tweets especially when they're formatted in such an obnoxious manner.

tl;dr op is wrong but for all the right reasons

I’ve spoken up about this before, and it might seem nitpicky, but it’s the difference that lets people claim that being antisemitic isn’t even about Jews.

28K notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Die Gleichheit ist ein inhaltsloser Begriff, sie kann ebensowohl bedeuten gleiche Knechtschaft aller wie gleiche Freiheit aller.

Equality is a meaningless concept; it can just as well mean equal slavery for all as equal freedom for all.

Heinrich von Treitschke (1834 – 1896), German historian and political publicist, forerunner of political antisemitism

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Es bildet die Achtung, welche der Staat der Person und ihrer Freiheit erweist, den sichersten Maßstab seiner Kultur.

The respect which the state shows to the person and their freedom forms the surest standard of its culture.

Heinrich von Treitschke (1834 – 1896), German historian, publicist, and politician, forerunner of political antisemitism in Germany

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

PART A. Heinrich von Treitschke presents a vision of a world in which war is a

PART A. Heinrich von Treitschke presents a vision of a world in which war is a

PART A. Heinrich von Treitschke presents a vision of a world in which war is a glorious, even a beautiful, thing. It is the ultimate expression of nationalism. Wilfred Owen’s poem Dulce et Decorum est, offers a view of the ugliness of war as seen by a World War I soldier who had actually fought in the front lines. (He died there as well. Owen did not survive the war.) He shows that the old Latin…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Exposition Art Blog Helmut Newton - fashion photographer

Helmut Newton (born Helmut Neustädter; 31 October 1920 – 23 January 2004) was a German-Australian photographer. He was a “prolific, widely imitated fashion photographer whose provocative, erotically charged black-and-white photos were a mainstay of Vogue and other publications."Newton was born in Berlin, the son of Klara "Claire” (née Marquis) and Max Neustädter, a button factory owner.[2] His family was Jewish.Newton attended the Heinrich-von-Treitschke-Realgymnasium and the American School in Berlin.

More

1 note

·

View note

Text

Konservative Revolution

Unter "Konservativer Revolution" versteht man ein Netzwerk von Intellektuellen, die in der Zeit der Weimarer Republik, in schärfster Gegnerschaft zu ihr, antidemokratisches, antiegalitäres und antiliberales Denken entwickelten. Dazu gehören Intellektuelle wie Oswald Spengler, Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, Ernst und Friedrich Georg Jünger, Edgar Jung, Carl Schmitt, Ludwig Klages, Thomas Mann, Hans Freyer, Hans Zehrer, Ernst Niekisch oder Ernst von Salomon. Die paradoxe Wortbildung aus konservativ und revolutionär findet sich bei Thomas Mann, der nur zeitweilig ein Vertreter dieser Richtung war, Arthur Moeller van den Bruck und Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Sie weist darauf hin, dass die Exponenten dieser Bewegung kein rein restauratives Ziel wie die ursprüngliche Rechte verfolgt, die nur die wilhelminische Monarchie wiederherstellen will. Zum Beispiel will die Konservative Revolution eine neue Synthese zwischen Konservativismus und einem, autoritär gewendeten, Sozialismus.

Zu ihren Vorläufern gehören Vertreter der Romantik und Friedrich Nietzsche. Von Nietzsche erbt die Konservative Revolution vor allem ihr zyklisches oder sphärisches Konzept von Zeit, die ewige Wiederkunft. Konzepte der Konservativen Revolution finden sich vorgeformt bei dem Religionswissenschaftler und Orientalisten Paul de Lagarde, beim Komponisten Richard Wagner und dem Historiker Heinrich von Treitschke.

Fünf Strömungen sind der Konservative Revolution zuzuordnen

Die Völkischen haben als Zentralbegriff ihrer Weltanschauung die Rasse. Sie neigen zur Germanentümelei und haben überhaupt eine Neigung zum schwärmerisch-religiös-sektiererischen. Zu ihnen gehören beispielsweise Exponenten eines arisch-germanisch gewandelten "Deutschchristentums", eines germanophilen Neuheidentums, einer rassistisch-theosophischen Ariosophie oder die stark verschwörungstheoretisch ausgerichteteten Anhänger der Mathilde von Ludendorff.

Die Jungkonservativen haben ein stark autoritäres und elitäres Politikverständnis. In Strukturen wie dem Juniklub und später dem Herrenklub finden sich vor allem Vertreter der gesellschaftlichen Eliten aus Politik, Kultur, Wissenschaft und Wirtschaft zusammen, um über eine "organische" Alternative zur Republik zu diskutieren. Vertreter dieser Richtung sind Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, mit seinem Konzept des Dritten Reiches, und Edgar Julius Jung, die vor allem auch Einfluss auf Politiker zu nehmen versuchen. Ihnen stehen Zeitschriften wie das "Gewissen" oder der "Ring" zur Verfügung. Partiell treten die Vertreter dieser Denkfamilie für eine Orientierung an und ein Bündnis mit der Sowjetunion gegen den liberalistischen und rationalistischen Westen ein.

Die Nationalrevolutionäre sind eine mehr aktivistische Strömung, deren Geist sich aus der Erfahrung des Ersten Weltkrieges speist. Ihr gehören Vertreter eines soldatischen Nationalismus unter Führung des Schriftstellers Ernst Jünger, dessen Texte den Krieg stark verklären, an. Zeitschriften wie "Standarte" und "Arminius" werben für diese Richtung. Verwandt ist der Nationalbolschewismus eines Ernst Niekisch und seiner Zeitschrift "Widerstand". Hier verbinden sich Konzepte eines autoritär gedachten Sozialismus mit einem antiwestlichen Affekt und einer daraus folgenden Orientierung auf die Sowjetunion, noch stärker als bei manchen Jungkonservativen. Eine Synthese aus linken und rechten Versatzstücken entwickelt noch mehr die "Gruppe Sozialrevolutionärer Nationalisten" von Karl Otto Paetel, die auf eine Querfront unter Einbeziehung der KPD hinarbeitet

Die Bündische Jugend stellt eine Kreuzung aus dem eher romantisch-anarchischen Wandervogel des Vorkriegs und disziplinierteren Gruppen wie dem "Bund deutscher Neupfadfinder" (BNP) dar. Die Bündischen sind im Gegensatz zu den bisher genannten Gruppen weniger theoretisch-politisch ausgerichtet. Gruppen wie die (autonome) deutsche Jungenschaft vom 1. November (1929) (d.j.1.11) sind relativ unpolitischer Ausdruck jugendlichen Lebens. Bünde wie die Geusen hingegen orientieren sich schon an der NSDAP.

Konkrete politische Aktion geht vom Landvolk aus. Bauern wehren sich, vor allem in Schleswig Holstein und Teilen Niedersachsens, Ostpreußens und Schlesiens, gegen ihre im Rahmen der Wirtschaftskrise immer unerfreulicher werdende soziale Situation. Die Bauern empören sich wegen der Untätigkeit der Politik, aber auch gegen den Versailler Vertrag. Sie leisten vor allem passiven Widerstand, zum Beispiel durch Steuerboykott, es kommt jedoch 1929 auch zu Bombenanschlägen. Schließlich enden viele Bauern im Lager der NSDAP.

An der Frage nach dem Anteil der Konservativen Revolution am Nationalsozialismus scheiden sich die Geister. Sehen Kritiker sie vor allem als Vorläufer und Wegbereiter so betont Mohler den eigenständigen Charakter dieser Denkfamilie. Ganz sicher ist es die historische Verantwortung der KR, die Weimarer Republik von rechts mit demontiert und ein Klima des Hasses gegen die demokratischen Institutionen begünstigt zu haben. Tatsache ist aber, dass es unter Vertretern dieser Strömung ein breites Spektrum an Haltungen zu Nationalsozialismus gab. Mit dem NS gemeinsam hat die Konservative Revolution natürlich den Affekt gegen den Parlamentarismus der Weimarer Republik, gegen die Gleichheit und den liberalen Gesellschaftsentwurf allgemein. Sie kritisiert am Nationalsozialismus vor allem seinen Massencharakter und teilweise seinen rassistischen Antisemitismus. Vertreter der KR wie Oswald Spengler hielten Abstand zu den neuen Machthabern. 1933 veröffentlicht er noch sein Buch "Die Jahre der Entscheidung", das deutliche Kritik an den Nationalsozialisten enthält. Ernst Jünger wählt den Weg der inneren Emigration, Sein Roman "Auf den Marmorklippen" enthält kaum verklausuliert ebenfalls Kritik am Nationalsozialismus. Der Staatsrechtler Carl Schmitt hingegen stellte sich dem Dritten Reich als "Kronjurist" zur Verfügung und rechtfertigte zu Beispiel die Terrormaßnahmen nach den Ereignissen des so genannten "Röhm-Putsches" im Juni/Juli 1934.

Der Einfluss, den Ideen der Konservativen Revolution auf die Attentäter des 20. Juli 1944 gehabt haben, darf nicht unterschätzt werden. Carl Friedrich von Stauffenberg entstammte dem Kreis um den Dichter Stefan George, der in den Zirkeln der konservativen Revolutionäre viel rezipiert wurde.

Nach 1945 konnten die Vertreter der Konservativen Revolution nicht mehr an ihre frühere Wirksamkeit anknüpfen. Zu sehr war der Konservativismus als Mitverursacher der deutschen Katastrophe diskreditiert. Mohler ist vorgeworfen worden, dass er zum Zweck der Reinwaschung der Konservativen die Konservative Revolution, weniger aufgefunden, als erst erfunden hat, dass sie also als relativ geschlossenes und eigenständige Denkrichtung in der Weimarerer Republik nicht existiert hat.

0 notes

Text

W. E. B. DuBois

William Edward Burghardt "W. E. B." Du Bois (pronounced /duːˈbɔɪz/ doo-BOYZ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, historian, civil rights activist, Pan-Africanist, author, and editor. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relatively tolerant and integrated community. After completing graduate work at the University of Berlin and Harvard, where he was the first African American to earn a doctorate, he became a professor of history, sociology and economics at Atlanta University. Du Bois was one of the co-founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

Du Bois rose to national prominence as the leader of the Niagara Movement, a group of African-American activists who wanted equal rights for blacks. Du Bois and his supporters opposed the Atlanta compromise, an agreement crafted by Booker T. Washington which provided that Southern blacks would work and submit to white political rule, while Southern whites guaranteed that blacks would receive basic educational and economic opportunities. Instead, Du Bois insisted on full civil rights and increased political representation, which he believed would be brought about by the African-American intellectual elite. He referred to this group as the Talented Tenth and believed that African Americans needed the chances for advanced education to develop its leadership.

Racism was the main target of Du Bois's polemics, and he strongly protested against lynching, Jim Crow laws, and discrimination in education and employment. His cause included people of color everywhere, particularly Africans and Asians in colonies. He was a proponent of Pan-Africanism and helped organize several Pan-African Congresses to fight for independence of African colonies from European powers. Du Bois made several trips to Europe, Africa and Asia. After World War I, he surveyed the experiences of American black soldiers in France and documented widespread bigotry in the United States military.

Du Bois was a prolific author. His collection of essays, The Souls of Black Folk, was a seminal work in African-American literature; and his 1935 magnum opus Black Reconstruction in America challenged the prevailing orthodoxy that blacks were responsible for the failures of the Reconstruction Era. He wrote one of the first scientific treatises in the field of American sociology, and he published three autobiographies, each of which contains insightful essays on sociology, politics and history. In his role as editor of the NAACP's journal The Crisis, he published many influential pieces. Du Bois believed that capitalism was a primary cause of racism, and he was generally sympathetic to socialist causes throughout his life. He was an ardent peace activist and advocated nuclear disarmament. The United States' Civil Rights Act, embodying many of the reforms for which Du Bois had campaigned his entire life, was enacted a year after his death.

Early life

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born on February 23, 1868, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, to Alfred and Mary Silvina (née Burghardt) Du Bois. Mary Silvina Burghardt's family was part of the very small free black population of Great Barrington and had long owned land in the state. She was descended from Dutch, African and English ancestors. William Du Bois's maternal great-great-grandfather was Tom Burghardt, a slave (born in West Africa around 1730), who was held by the Dutch colonist Conraed Burghardt. Tom briefly served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, which may have been how he gained his freedom during the 18th century. His son Jack Burghardt was the father of Othello Burghardt, who was the father of Mary Silvina Burghardt.

William Du Bois's paternal great-grandfather was James Du Bois of Poughkeepsie, New York, an ethnic French-American who fathered several children with slave mistresses. One of James' mixed-race sons was Alexander. He traveled and worked in Haiti, where he fathered a son, Alfred, with a mistress. Alexander returned to Connecticut, leaving Alfred in Haiti with his mother.

Sometime before 1860, Alfred Du Bois emigrated to the United States, settling in Massachusetts. He married Mary Silvina Burghardt on February 5, 1867, in Housatonic. Alfred left Mary in 1870, two years after their son William was born. Mary Burghardt Du Bois moved with her son back to her parents' house in Great Barrington until he was five. She worked to support her family (receiving some assistance from her brother and neighbors), until she suffered a stroke in the early 1880s. She died in 1885.

Great Barrington had a majority European American community, who treated Du Bois generally well. He attended the local integrated public school and played with white schoolmates. As an adult, he wrote about racism which he felt as a fatherless child and the experience of being a minority in the town. But, teachers recognized his ability and encouraged his intellectual pursuits, and his rewarding experience with academic studies led him to believe that he could use his knowledge to empower African Americans. Du Bois graduated from the town's Searles High School. When Du Bois decided to attend college, the congregation of his childhood church, the First Congregational Church of Great Barrington, raised the money for his tuition.

University education

Relying on money donated by neighbors, Du Bois attended Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee, from 1885 to 1888. His travel to and residency in the South was Du Bois's first experience with Southern racism, which at the time encompassed Jim Crow laws, bigotry, suppression of black voting, and lynchings; the lattermost reached a peak in the next decade. After receiving a bachelor's degree from Fisk, he attended Harvard College (which did not accept course credits from Fisk) from 1888 to 1890, where he was strongly influenced by his professor William James, prominent in American philosophy. Du Bois paid his way through three years at Harvard with money from summer jobs, an inheritance, scholarships, and loans from friends. In 1890, Harvard awarded Du Bois his second bachelor's degree, cum laude, in history. In 1891, Du Bois received a scholarship to attend the sociology graduate school at Harvard.