#hashtag trans anthology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

DISTURBING THE READER

A Comparative Looks at Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke (LaRocca) & Where Are You, Dear Hear? (Enriquez, trans. McDowell)

*CONTENT WARNINGS*

General Disturbing content, mentions of death (including infants & animals), mentions of suicide/self-harm, abuse & manipulation, brief mention of homophobia, descriptions of GBH, implication of sexual assault/abuse, kink play

*SPOILERS FOR*

Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke (2021), The Dangers of Smoking in Bed (2009), Saw X (2023), Saw 3D (2010), Happy Death Day (2017), Scream (1996)

It’s hard to say what a ‘good’ disturbing horror is. Is it a story that terrifies you to the point of being unable to sleep? Or one that leaves you feeling disgusted and makes your stomach churn each time you just think about it? Or where you’re left almost in a paralysed state as you’ve been forced to think of a wider picture you don’t have the theological prescription to see? It’s hard to say what a disturbing horror even is because at its core isn’t all horror disturbing? Is Saw more disturbing than a psychological horror like Get Out because it features more gore? Or is Get Out more disturbing because it features more difficult political and social topics? That’s not what we’re discussing in this essay - although I eventually do want to. Here we are discussing the art of doing disturbing horror and more importantly doing it well. I’ll be looking at two short stories for this - Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke from Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke & Other Misfortunes by Eric LaRocca & Where Are You, Dear Heart? from The Dangers of Smoking in Bed by Marianna Enriquez, translated by Megan McDowell.

Subjectivity is the root of a majority of arguments as we’ll all possess differing subjective opinions (for example, there are people who believe the Child’s Play franchise isn’t a masterpiece of modern horror and my subject opinion is that objectively those people are wrong).

But with my discussion of these books I will be heavily relying on my own opinions & readings of the stories as well as looking at the reviews & content other people have made about the books.

So with no further ado, let’s get into it.

I’ve been internally debating horror that sets out to truly disturb since reading Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke And Other Misfortunes. From Waterstones, to the author’s website it’s boasted as a viral TikTok sensation across all of its marketing and that’s more than accurate. The hashtag of the book title has 8.2 million views and the GoodReads page has 42,755 ratings alongside 12,469 reviews.

However, the reason it’s so viral it seems is due to its divisive nature - many preaching the book as far too disturbing, and even relishing in its own disgusting nature. It currently sits at 3 stars on GoodReads.

LaRocca is a fairly new author - the earliest of his work I could find only dated back to 2021 - and is a Bram Stoker Award nominee as well as won a Splatterpunk Award - both for Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke. I couldn’t find much on LaRocca except for an interview where they describe their work as “the dark and the absurd filtered through a decidedly queer lens,” as well as citing somewhat controversial films “High Tension, Martyrs, Inside, and A Serbian Film.” as influences due to their “frenetic intensity.” He also cites in this interview and in an afterword of their anthology book that a lack of belief in God he desperately attempted to achieve as well as a desire to fit in with the children around them is a major inspiration and driving emotion behind their writing.

I’d like to preface that I wanted to like Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke. I’m a big fan of horror and even more of psychological horror. I went in anticipating perhaps a gory version of Hereditary - another story that relishes in its own shocking macabreness in a way - as both indicated itself as a subset of gothic literature as well as being gory. However, I found I just couldn’t. The first story to greet you at the start of this anthology is the titular (and most ‘popular’) story, Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke. It’s easy to see why these collections of short stories are named after this specific one as it’s easily the best. The other two stories - The Enchantment and You’ll Find It’s Like That All Over are in my opinion significantly weaker.

Described as a “macabre ballet between two lonely young women”, we follow the rise and horrific fall of an online relationship between two women in a chat room in the 2000’s.

Warnings for spoilers now.

In Things Have Gotten Worse, we’re introduced into this world via an Author’s note - it's not LaRocca speaking in this author’s note however, it’s an in world character who we never see who is reporting on “… the untimely demise of Agnes Petrella.” They assure us of their detachment of the two characters (“… no way affiliated with Zoe Cross’ legal counsel or Agnes Petrella’s surviving family.”) before informing us due to the police report nature of what we’re about to read, “… certain elements of [Zoe and Agnes’] communication have been redacted or censored…”

Off the bat, I really liked this formatting of this story being pulled from a police report. Whilst it was a bit confusing - I had to go back in the book to check if this was indeed an author’s note from LaRocca and if the story was true if so - it wasn’t. It helps to build on the fetish themes as we feel voyeuristic reading these women’s conversations - and every time we see an “[Omitted.]” it reminds us we shouldn’t be seeing this and builds upon the suspense as your mind races; what could possibly be censored in a chat log that already details a masturbation instruction and then a detailed recount of the horrific murder of an infant? A lot of the omitted make sense - like the domain of the emails/ chat rooms the couple use. Almost like the companies didn’t want to be associated with a murder or get involved with a law suit. The framing of the police report that also tells us in the first page that the main character will wind up dead by the end also helps add to that feeling of dread and voyeurism. With every page, you feel yourself walking down a hallway and know no matter how slow or fast you walk (slash read), there’s no way to save Agnes from her fate. It’s a cruel dramatic irony we can’t escape.

Speaking of…

Agnes is a woman on a queer chat forum who lists an antique apple peeler for sale - circa 1897 to be exact - in an eloquent prose that touches on how much the antique peeler means to her family.

This isn’t your regular Facebook marketplace listing. Agnes writes for nearly 3.5 pages about this apple peeler and its history with her Grandmother.

It catches the attention of Zoe Cross, who emails offering to purchase the peeler for her elderly Grandfather due to the possible link to composer Charles Ives. Her email similarly is lavish with familial detail and the two women continue to email, Zoe eventually learning Agnes is financially and physically cut off from her parents due to being a lesbian. Zoe sends Agnes a thousand dollars, taking care of her rent and asking her to keep the apple peeler and not to sell it as it’s her last familial connection. Quickly - quite quickly actually - the two women start instant messaging in a chat room.

About the IMing. Due to the fact this story is the book version of found footage we have no author based description - everything in the book is basically digital based dialogue. World building is hard, especially in such a short space of page without this narrative description, and LaRocca is skilled in giving us just enough to build the world in our head without overloading us with exposition or scene setting. However, I struggle to believe the setting of 2000 - despite the use of a chat room that evokes memories of AOL and MSN, the ‘dialogue’ feels like it was written in the 2020’s. It almost reminds me of the first Fear Street in that regard. I adore the Fear Street movies, but even I have to admit the first one - set in 1994 - doesn’t really feel like it’s set in ‘94. Speaking of, the dialogue is another point of contention. Some of the criticism Things Have Gotten Worse receives relates to the elaborate prose Zoe and Agnes uses - and how it can often be somewhat hard to differentiate between the two voices? In my scriptwriting class at uni, one of the things we were taught is to make sure when writing dialogue, the voices are distinct. Make sure two characters don’t speak too similarly - they need some kind of a unique voice even if they have the same accent as another character. The similar prose styles of Agnes and Zoe does lead to a bit of a difficult time reading - it can take a while to realise who’s speaking, especially with the IM chat logs and when a character sends multiple emails in a row.There’s a take you can stand with that the similar prose between the two suggests why they found each other and were attracted to each other, but I feel like that would be supported more if there was another characters speech we could compare that to - but with the nature of the story and formatting we don’t have that. Even the author’s note uses lavish language and it does still make for a little bit of having to go back and forth to realise who’s actually talking - or, well, typing.

Back in the world of the story, the two’s conversations eventually result in a discussion into some fetishes of Zoe’s. The two enter an online master/slave relationship - Zoe’s demands of Agnes leading to her losing her job and killing a salamander under Zoe’s request.

This escalation of Agnes and Zoe’s relationship and eventual dynamic does kind of come out of nowhere. It’s effective for horror, but outside of the shock value it’s not very effective from a plot point of view.

To her credit, this untimely unaliving of the amphibian does prompt Agnes to leave but she ends up returning to Zoe and the two resume their relationship and dynamic. Agnes’ insistence on wanting a baby leads Zoe to instruct her to purposely contract a tapeworm by eating days old meat. Agnes does indeed contract a tape worm, referring to it as Zoe’s baby and even going as far as to ascribe a gender and name to the parasite.

This part is a point of major criticism shared by people online. A disclaimer, I am not a lesbian myself and therefore cannot be the voice of knowledge on the topic. However, I did some research. I found an article from 2020 that stated lesbian & bisexual women in WLW relationships were more likely to report a pregnancy ending in stillbirth. Lesbian women were more likely to report low birth weight infants and bisexual and lesbian women were more likely to report very preterm births compared to heterosexual women. A lot of queer women in queer relationships struggle with pregnancy and childbirth and as such this plot point has been criticised as a ploy of using something WLW couples actually struggle with as a horror plot point - especially since LaRocca is not a queer women (although they are a queer person I’m not trying to negate their identity). This delves into a larger discussion on representation and who gets to tell certain stories.

When Zoe realises how rapidly Agnes’ physical & mental health is deteriorating, she ceases their master slave contract and cuts communication. Agnes spirals and when she passes the tapeworm she ends up seemingly ending her own life by cutting out her own eyes with the antique apple peeler.

It’s a lot.

Most of all, the narrative feels unnecessarily cruel. Maybe I’ve been spoiled by horror movie villains having clear motives even in the most ridiculous of movies (heck, John Kramer has four throughout the Saw franchise) but I don’t understand why Zoe is insistent on torturing Agnes. (I will note Zoe isn’t an explicit villain but she’s definitely the antagonist to Agnes’ protagonist) Again, the story is short and can only get so much across in its 120 pages but the only explanation resembling a reason for Zoe’s abuse of Agnes is that she’s a domme, but that kind of excuse leads to some uneasy generalisations around kink play and those who engage in it.

Another general criticism I have of the story - and this is an opinion quite a few agree with - when LaRocca’s work isn’t relishing in its own shocking macarbness, it’s kind of boring. Maybe I don’t have the attention span for it, but at certain points I was feeling myself uninterested in what I was reading. This happens less with Things Have Gotten Worse to be fair, but I did find especially in The Enchantment I wasn’t interested and was actively getting frustrated.

And another reason I was getting frustrated was because of my other major criticism - I don’t like any of the characters. I do think this may be on purpose - as implied by LaRocca’s tweet here - “I promise you—reading horror fiction with complex, vile, yes even “problematic” characters will not impact the integrity of your moral character. Not every character in a FICTIONAL book needs to reflect your ethics and values. I will die on this hill because I know I’m right.”.

And, it’s true. Not every character has to be morally good. There are plenty of characters that horror fans love despite their morally dubious or even outright heinous actions. For instance, murderous doll Chucky. Love of my life Amanda Young. John Kramer. There are also morally dubious protagonists in horror, Gale Weathers is seen as narcissistic and power hungry in the Scream franchise, in Happy Death Day, Tree is - for lack of a better word - an asshole to everyone around her at the start of the film. But, at least for myself, my dislike of the characters in LaRocca’s work doesn’t come from a moral high ground. I don’t know who to root for. I simply don’t like any of them. Like I said, this issue is less present in Things Have Gotten Worse but in the other two short stories I genuinely didn’t root for anyone. I didn’t have a reason to. I didn’t have a reason to keep myself engaged in the world of these stories. There’s a reason slashers that set up 2 dimensional meatbags as their only ‘characters’ generally are critiqued and seen as ‘bad.’ If we’re given nothing to root for or relate to, what’s the point? In Scream, heralded as one of the greatest horror movies of all time, nearly every kill we get a chance to get to know the victim that dies and like them - and that’s not even mentioning Sidney who’s one of the best final girls of all time. If we’re not given anything to like or find interesting, what’s the point of the story? What’s the point of us as viewers/readers spending time in this world?

Take, for example, Saw 3D vs Saw X.

I promise I’ll stop mentioning Saw. Actually I can’t promise that.

In Saw X we’re mainly following John Kramer getting revenge on some people who scammed him by promising to cure his cancer. That’s not a spoiler, it was in the trailer. Despite being a morally horrific character, the film is garnering great reviews and people are willing to follow him in the story because we enjoy being around him.

Whilst in Saw 3D, that guy who lies about being in a Saw trap? Fuck that guy. Even though as a dislikeable character we see him getting tortured, we don’t enjoy seeing him getting tortured ‘cause there’s nothing there for us. What’s the point? Maybe this is because LaRocca cites A Serbian Film as an inspiration which is a red flag unto itself. A Serbian Film is once again mindless torture without the plot or any semblance of humanity within the filmmaking.

So, overall, do I hate this book? No. I think it’s an okay/good book depending on how much you agree with what I’ve mentioned. I don’t think it’s a bad book and maybe with a couple more revisions it could’ve been really great. I feel like LaRocca was maybe trying to evoke the delicate torment Black Swan evoked - “a macabre ballet” - but ultimately I feel it’s more aligned to a reddit horror story in its current state.

So can a disturbing horror short story be great?

The Dangers of Smoking in Bed - originally published in Spanish under the title Los Peligros de Fumar en la Cama - is a book I couldn’t help but keep thinking about when reading Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke and Other Misfortunes. Similarly to the latter mentioned book, The Dangers of Smoking in Bed is an anthology series composed of several short stories under the genre of psychological & supernatural horror.

Mariana Enriquez is an Argentinian author/journalist. The history and politics of Argentina are easy to see in her writing - especially in several short stories that feature ghostly children and children who return following disappearances. Being born in 1973, Enriquez was young but grew up in the time when “military officials carried out the systematic theft of babies from political dissidents who were detained or often executed and disposed of without a trace.” She describes herself as not “want[ing] to be complicit in any kind of silence; to be timid about horrifying things is dangerous too.” What she knows and what she believes is present in her work. Curiously, she also seems to pride herself in research - asking for clarification and feedback on any male love making scenes from her gay friends. I’d describe Enriquez work as horror that can sicken people that also has a delicateness and preciseness to it - everything is planned.

A story that is reminiscent of the themes of Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke is the 7th short story in The Dangers of Smoking in Bed; Where Are You, Dear Heart? We follow an unnamed woman who details over only 10 pages her journey with cardiophilia - or a fetish for heartbeats.

Okay, so let’s acknowledge the significant differences between these stories; Things Have Gotten Worse has 121 pages whilst Where Are You, Dear Heart? only has 10 - which fun fact puts Where Are You, Dear Heart? officially in the short story region whilst Things Have Gotten Worse is in the novella territory. Things Have Gotten Worse follows a queer couple whilst the woman’s two partners in Where Are You, Dear Heart? are male. Where Are You, Dear Heart? takes place around the 70’s/80’s but it’s not explicitly made clear and is a more conventional narrative experience compared to the chat logs/emails of Things Have Gotten Worse.

So, why am I comparing these two? I think there’s enough similarities to warrant such. Hear me out! Both books focus on unconventional fetishes - yes cardiophilia is quite unconventional but also the length Zoe wants to control Agnes’ life & actions down to forcing Agnes to kill a small creature for Zoe is a bit more than your typical fetish. Both use this fetishistic relationship as a way to examine our character.

The story opens with a woman detailing seeing an older relative of her friend’s (supposedly the friend’s Dad) penis when she’s a young child as well as very briefly touching on the fact he potentially/more than likely sexually abused her.

I really chose a safe first topic, huh?

Right off the bat with Where are You, Dear Heart? we’re dealing with similarly upsetting themes of someone being taken advantage of. There’s more to be said on that but I’ll touch on that when we get to it. Off the bat Mariana grabs our attention - especially as the narrative voice or narrator - speaks about these incidents so nonchalantly. Similarly to how some victims can end up with amnesia after suffering abuse.

One of the few things our narrator remembers from this man isn’t his name or even his face. It’s the fact he died due to a failed heart operation. That night she scratches an X onto her chest with her nail. She continues to detail that she became attached to a sickly Helen Burns from the novel Jane Eyre - becoming attached because Helen is dying - even going as far as to view the scene where Jane sleeps in Helen’s bed on her last day alive as a love scene (That imagery will return later). She goes on to explore what arouses her even further - as many teenagers going through puberty do - and visits a friend’s brother when she learns he has an inoperable tumour between his heart and lungs believing she could fall in love with him. However, she finds he’s too sick for her to be attracted to him, so satisfies herself with medical books.

I find this plot point of the brother actually a bit funny - not the fact a kid is dying - but it almost seems reminiscent of that cliche of being attracted to the best friend’s brother, this is basically like that! But it’s his cancer that led her to being interested. And with this, we’re invited to view the narrator as a regular teenage girl figuring herself out. Plenty of girls have their first crush be a book character and a friend’s relative - it just so happens she’s not attracted to their looks but their ailments. I really appreciate this framing of our main character - we’re provided context for the fetish in the main storyline and allowed to find a way to relate it to our own lives. It feels like a mature way to handle this idea - it’s not a gruesome spectacle, it's a character study, we’re grounding the character in relatable reality with book crushes and the like.

We continue to experience the narrator developing her sexuality via the medical books she spends all her allowance on - even going as far to refine her interests such as knowing she isn’t a fan of tuberculosis, cancer or the suggested ‘eroticism’ of quietly dying characters in Victorian novels. She clarifies herself as being attracted to cardiovascular disease and purchases a CD that held recordings of different heart beats, murmurs and flutters that pleases her so much she ends up getting rid of the CD due to the power over her as well as makes her realises she’s not interested in traditional sex. She clarifies the moment she ‘lost control’ so to speak was when she found a website where heart beat fetishists could share and indulge in audio recordings of different heartbeats. Even the way she describes her ‘alone time’ is almost medical - brutal and bluntly descriptive to the point I couldn’t put the description in this video without fear of no one ever seeing this blog. I’d highly recommend reading both these books to not only get the full effect of the author’s words but also, make up your own opinion.

It’s a subtle bleed in - pardon the metaphor - of Enriquez showcasing how the fetish is taking over our narrator’s life. Gone are the emotive prose she used to describe the sickly Victorian characters she was attached to. Now she’s taking influence from the medical jargon.

On the heartbeat website, our narrator refrains from communicating, preferring to keep to herself. Until she locates an account where she cannot resist reaching out. Somehow, they live in the same city but choose to ignore the ideas of fate and become enamoured with each other - his sickly heartbeat and her stethoscopes against the world.

“We both knew how it would end, and we didn’t care.”

A statement that builds unto itself, it gives imagery of desperation. I instantly thought of the poster of Blue Valentine - a desperate intimacy between two lovers who no one else understands. It’s curious how the only people that get extended descriptions are the characters our narrator is attracted to or the prominent men in her life. We’re seeing the world through our narrator’s tunnel vision view - similarly to how we only see the world of Things Have Gotten Worse through what Agnes and Zoe give away in their communications. I really focused on the description afforded to this man our narrator becomes enamoured with. He’s described as sick - which isolates him from the rest of the cardiophilia community as they believe he takes things too far by playing with his illness to produce audio recordings. Our narrator also notes that he resembles the man from the start of the story - the friend’s parent with the scar and… penis. With this, I build this image of possibly she’s further being taken advantage of. Throughout, Enriquez doesn’t give any indication to how much time has passed between each event and as such it’s almost like we still have the original young girl in our minds as we read. With this visual reminder of her original abuser and the fact he’s known to their community as someone who takes things too far, it evokes the idea that this man is more sinister than the narrator might be recognising. And it’s a common theme for young inexperienced women in kink to be taken advantage of and I wonder if this is what Enriquez is portraying.

As the cardioplay grows more extreme - experimenting with items ranging from caffeine to drugs - our narrator grows frantic and begins to develop a desire to maim him so as to grow closer to the man and his heart.

“But I think I ended up hating him. Maybe I hated him from the start. Just like I hated the man that made me abnormal, who’d made me sick, with his tired penis in front of the TV, and that beautiful scar.”

The statements about her lover are short and punchy. Whilst the sentences about this original man - the one who now it seems more clear may have indeed sexually abused her in some way (“made me” “with his”) - build upon each other. What’s building? Her rage? Her general emotion? Her regret? I think that’s up to interpretation.

This hatred and association with her previous abuser seemingly influences our narrator to further push this man to his limits. More drugs, holding a bag over his head, even pleasuring herself in a toilet stall when he’s hospitalised due to their play. The story ultimately culminates in her insisting on wanting to see his heart - only referring to the heart as “it.” And he responds that they’re going to need a saw.

The actual line packs a punch, as we fill in the blanks of she is going to cut out his heart to satisfy herself. The ending reminds me of Midsommar - I spoil so many other things in this review of two books - whereas Dani’s ultimate fate is still debated on whether we should say 'good for her!' or 'oh shit, oh no' as she condemns her gaslighting boyfriend to death. In both cases the victim is not a great person but not deserving of being killed in a horrific manner. I believe both endings are using a surface level wrapping of 'good for her' to invite you to wade further into the analysis and realise how the cycle of abuse can lead those who are abused to lash out in retaliation, pain and an attempt to retrieve power.

Whilst not a perfect book objectively, I really adore Enriquez’ stories and the disturbing horror interlaced. As mentioned above, she uses what she knows and more importantly what she can learn from other people’s first hand experiences to create these stories that pull us in and shock us.

In conclusion, The Dangers of Smoking in Bed is not a perfect book. The length of the stories have led to criticism of corners being cut and characters lacking development. Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke and Other Misfortunes is not a bad book - whilst I personally didn’t enjoy reading it I can appreciate the book for what it is and what it was trying to do and I do think LaRocca has talent and the ability to continue in this industry. I’m just a horror fan on the internet with one opinion - you might have a completely different one so please check both of these books out and share your thoughts (be nice about it though please).

So, disturbing horror. We can be disturbed by gore. We can be disturbed by unconventional relationships with wildly imbalanced power dynamics. We can be disturbed by the chat logs between two lonely queer women. We can be disturbed by a young girl discovering her sexuality as it’s not what we’re used to. But what makes a horror truly disturbing? Maybe we’ll find out soon.

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SOURCES LaRocca, E. (2022) Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke and Other Misfortunes. London: Titan Books. Pastorella, B. (2021) Meet the writer: Eric Larocca, This Is Horror. Available at: https://www.thisishorror.co.uk/meet-the-writer-eric-larocca/ (Accessed: 13 September 2023). Q&A with author Mariana Enríquez (2017) Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/1c3facd2-28e6-11e7-9ec8-168383da43b7 (Accessed: 13 September 2023). Enriquez, M. (2022) The Dangers of Smoking in Bed: Stories Megan McDowell. Translated by M. McDowell. London: Granta. Cummins, A. (2022) Mariana Enríquez: ‘I don’t want to be complicit in any kind of silence’, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/oct/01/mariana-enriquez-our-share-of-night-i-dont-want-to-be-complicit-in-any-kind-of-silence (Accessed: 13 September 2023). LaRocca, E. @hystericteeth (2023) [Twitter] 5th July. Available at: https://twitter.com/hystericteeth/status/1676404563690045440 (Accessed: 13 September 2023). Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke (u.d.) GoodReads. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/57876868-things-have-gotten-worse-since-we-last-spoke?from_search=true&from_srp=true&qid=0KP3oz91cg&rank=1 (Accessed: 18 September 2023). The Dangers of Smoking in Bed (u.d.) GoodReads. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/53215250-the-dangers-of-smoking-in-bed?from_search=true&from_srp=true&qid=yUVz3vAmNQ&rank=1 (Accessed: 18 September 2023). Everett, B.G. et al. (2019) Sexual orientation disparities in pregnancy and infant outcomes, Maternal and child health journal. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6501574/ (Accessed: 25 October 2023). Williamson, K. (1996) Scream [DVD]. United States: Dimension Films. Lobdell, S. (2017) Happy Death Day [DVD]. United States: Blumhouse Productions, Universal Pictures. Melton, P. Dunstan, M. (2010) Saw 3D [DVD]. United States: Twisted Pictures, Lionsgate. Goldfinger, P. Stolberg, J. (2023) Saw X [DVD]. United States: Twisted Pictures, Lionsgate. Graziadei, P. Janiak, L. (2021) Fear Street Part One: 1994 [DVD]. United States: 20th Century Studios, Chernin Entertainment, Netflix. The Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke hashtag on TikTok.

#horror#analysis#horror books#Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke#The Dangers of Smoking in Bed#media criticism#tumblr essay#queer writer

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

september tbr yayyyyy

rereads are marked by a, new reads are marked by a ♡ , library reads are italicized and new acquisitions are bolded

physical tbr: 12

dune messiah - frank herbert - ♡

oedipus rex - sophocles - ♡

antigone - sophocles - ♡

medea - euripides - ♡

the way of kings - brandon sanderson - ♡

wuthering heights - emily bronte- ♡

switched - amanda hocking - ♡

the ghost and the goth - stacey kade - ♡

what artists wear - charlie porter - ♡

nick and norah's infinite playlist - ♡

circe - madeline miller - ☆

the immortalists - chloe benjamin - ☆

digital tbr: 1

the hundred years war on palestine - rashid khalidi - ♡

last months read books: 4

in the shadow of the sun - em castellan - dnf

boringg. i neeeeeeeedd to stop picking up romantasy it never works for me baksks.

98 - justin chin - dnf

author read too much shock fic as a child methinks. would have enjoyed a trigger warning.

pardalita - joana estrela - 4/5

a really sweet breath of fresh air. the art in this was really emotional and simple. i liked the use of environment shots, and 6 panel transitions. it was cool to watch the author blend things together. it felt quiet and calm, like a riverbank at night. you can kind of feel the waves lapping at your toes as you read. reccomend for sure, i might get the physical copy for myself.

grl2grl - julie anne peters - 2/5

uh. i'm always here for messy lesbians but this got kinda weirddddd. idk maybe it was a coincidence that the only two stories centering butch/trans masculine characters both had graphic sexual assault scenes. who knows. also the teacher one didn't make sense in the anthology sozzzz.

starman - the_widow_olivia on ao3 - 5/5

CUTEEEEEE i loved all of the little references to the show! read this right after rewatching sunshine (2007) which was an INSANE contrast. like hello.

vampires never get old - various authors - 3/5

good! i liked some stories better than others, but i enjoyed all of them :). hashtag vampires yippee

last months goal: read something off of my fall tbr

i didn't do this whoops. i got fun new shiny things i didn't want to....

this months goal: survive?

me when i'm job. i'm soooo eepy how am i meant to thrive in these conditions. would be nice to get that physical tbr number down tho cuz YIKES

#books#monthly tbr#god this month flew by. omg.#i might start bring a book to work to read on my lunch break.... hmm....

1 note

·

View note

Text

I Never Got to Be a Boy

*Record scratch*

*Freeze frame*

Yeah, that’s me. Bet you’re wondering how a shy introvert got to be standing up in front of hundreds of people, in the freezing cold, talking about being trans masculine and non-binary.

Public speaking scares the bejeezus out of me. I did it anyway.

I did it for the trans children that are now being attacked by our government for merely wanting to go to the bathroom. The right bathroom. The one that matches their gender identity.

I also did it for me. The past me, the “girl” who never got to be a boy.

No, I never got to be a little boy. I never got to have my first kiss as a boy. I never got to ask out a pretty girl (or boy) to the prom. I never got to have my first date as a boy. I never got to be a part of the men’s drill team in ROTC, or take part in anything other boys get to do. I was never a boy.

I had to have my first kiss as a girl. I had to wait to get asked to the prom. On my first date I had to wear a hated dress. Instead of being in the men’s silent drill team I was forced into the women’s drill team. We were basically Rockettes in military uniform. It was humiliating (for me).

I just didn’t know why, back then, I was so uncomfortable with my body, with my lot in life as a girl. At least I was lucky in one regard: it was the 90s, when wearing baggy flannels and jeans was fashionable, and for the first time in my life (and only time since) I was considered “in fashion.” I could cover my traitorous body in layers of flannel and a leather trench coat, be round-shouldered (to hide my breasts) and androgynous with my short hair and combat boots.

Back then, I didn’t know what being trans meant. I didn’t know there were trans masculine people. I barely knew there were trans women, and those only from shows like Maury Povich and Jerry Springer.

Because of this invisibility, it took me a long time to figure out my gender identity. I didn’t have anyone to look up to, to tell me what I was feeling was valid and real.

When it takes 30 years to figure out your gender identity, like it did for me, there’s a lot of guilt and pain that weighs heavily on you. The questions I ask myself the most are, “Why did I not figure this out sooner?” and “Why did I waste so much time in the closet?” The answer to both is because trans masculine people are not visible.

Trans masculine people just aren’t visible anywhere in the movement. Still, today, trans men are erased from the conversation around trans rights. Just last month, a trans boy was forced to wrestle girls instead of the boys he wanted to wrestle (and should be wrestling). He is taking testosterone, making it, frankly, unfair that he had to wrestle the girls. Parents were rightly upset, but not for the right reasons. The rules were intended to protect cis girls from losing to a trans girl, due to the erroneous idea that trans girls have some sort of unfair advantage in girls’ sports. No one considered what might happen if a trans masculine person was forced to wrestle the girls.

The bathroom bills are the same. Bigots want to put trans men (who often, but not always, pass as cis men due to testosterone) into women’s restrooms, because they fear “men” (i.e. trans women) in the women’s restroom. It’s because they forget that trans men even exist and don’t care how women would feel should a trans man enter a woman’s bathroom.

When people talk about trans men there is always at least one person who misunderstands and assumes trans women are being discussed. Because they just don’t know there is such a thing as a trans man.

Trans masculine people are told we’re just confused lesbians (considering I’m married to man this is funny to me) or that we have it “easy” because we can vanish into cishet-hood, which is laughable because many of us are not heterosexual at all. Nor would many trans men want to vanish into cishet society even if they could. I do not consistently pass, even after nearly 2 years on testosterone, and I’m very clearly married to a man. The question that follows is if we wanted to sleep with men, why transition at all? As though our gender identity had anything to do with our sexuality.

So when the opportunity came to be a voice for trans masculine people, I took it. I stood up for all those trans boys who don’t see themselves represented in media, who don’t see people standing up for them. I stood up so we can’t be ignored or erased or misunderstood, even by well-meaning allies.

I want trans boys to be able to be boys. I don’t want them to have to wait 30 years before realizing who they are inside. I don’t want them to miss out on the first kisses and first dates, and all the other experiences they should have as boys, not as girls. It makes me die a little inside every time I think about what life would have been like for me had I grown up a boy. I don’t want any other boy to ever have to go through that.

And so, there I was. Standing in the snow, shivering with fear and cold, to speak out and give voice to all the trans masculine kids who are invisible, who are suffering. I never got to be a boy, but I will do what I can to make sure they get to be one. Even if it means doing what terrifies me most.

If you want to know more about me and my story, I have an essay about how I discovered I was trans in the #Trans anthology. You can order it here (Amazon) or here (Smashwords).

This post is also part of a blog tour! Find out more about the anthology and the blog tour here. Please check out the next on the list, coming out on March 24th, Velvl Ryder.

#trans#nonbinary#bisexual#trans masculine#trans man#transgender#trans guy#hashtag trans anthology#trans anthology#trans writer#writer#non-binary

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

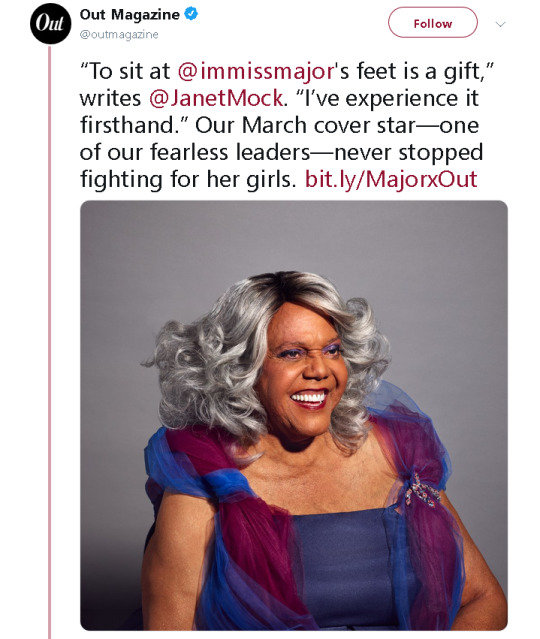

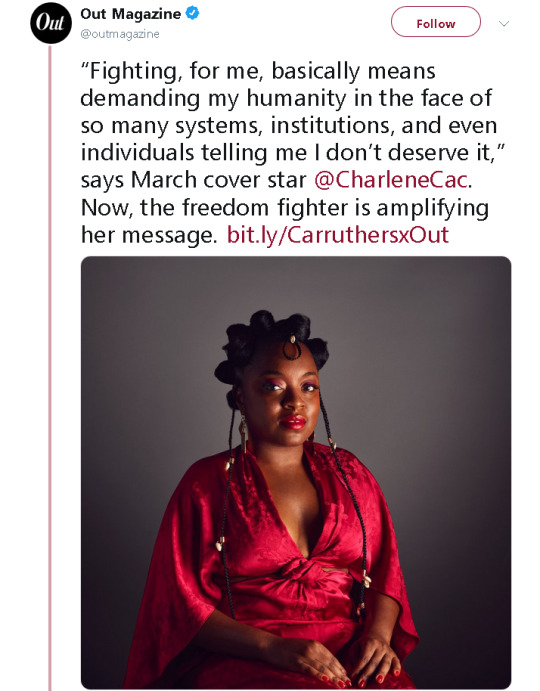

Five Black queer and trans women carrying our liberation forward, each of them representative of vital work around race, sexuality, gender, class, and beyond. For the occasion, Mock selected our “Mothers,” Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, who rose up at Stonewall and is still fighting, and Barbara Smith, legendary Black lesbian feminist from the ‘60s to today. Joining them are our Daughters — Tourmaline, the artist best known for immortalizing and honoring the icon Marsha P. Johnson; Alicia Garza, the queer woman who coined the term Black Lives Matter; and Charlene Carruthers, who’s literally writing the book on modern, intersectional queer feminism.

Miss Major has dedicated 50 years of her life to organizing for trans women of color. She is a veteran of the Stonewall riots, a survivor of Attica Correctional Facility, and the founding executive director of Transgender, Gender Variant, Intersex Justice Project (TGIJP), a nonprofit that centers and supports trans, gender-nonconforming, and intersex people in and out of prisons, jails, and detention centers. And when most wept at the election of Trump, Major persevered in her retirement, moving from the comfort of home in San Francisco to Arkansas, where she heard a call to help the trans community build a stronger movement. In Little Rock, she’s building the Griffin-Gracy Education Retreat and Historical Center, lovingly known as the House of GG.

Born and raised in Roxbury, Massachusetts, Tourmaline’s mother, Maureen Ridge, and late father, George Gossett, worked in the Labor and Black Power movements, respectively. With their influence, she developed a deep commitment to social justice and empowering marginalized people. As a college student, she became particularly drawn to the experiences of incarcerated, queer, and trans people. This led to her dedicating much of the last 15 years organizing with New York-based LGBTQ+ organizations like FIERCE and Sylvia Rivera Law Project, teaching at Rikers Island, and working with elders like Miss Major. “For a lot of trans, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming people of color, we didn't [initially] know about the prior generation of activists because their stories had been erased,” she says. “I think about not just people being pushed out of the movement, but how did HIV and AIDS — like criminalization, not just the epidemic — play into the erasure of us ever knowing of so many people who came before us?

It was July 2013 when the world encountered a brilliant, powerful assemblage of words that would come to define a generation. Alicia Garza gifted Black millennials the rallying cry #BlackLivesMatter in the aftermath of George Zimmerman’s acquittal in the murder of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin. She unleashed the power of digital activism to create a movement and revealed to us that a hashtag, a post, an image, and a video shared online could change the course of history.

Before joining forces with community organizers Patrisse Cullors-Khan and Opal Tometi, Alicia’s work had already spanned nearly two decades. Drawing inspiration from her childhood growing up in a household with a single mother, the lifelong Californian began her early work with an emphasis on reproductive justice. Since then, she has been able to see how the pieces of seemingly disparate issues like economic justice, students’ rights, and police brutality are all intertwined in the fight against state violence.

Last July, I witnessed Charlene Carruthers, drenched in sweat and filled with anguish, command the attention of a large crowd in response to the fatal police shooting of 37-year-old Harith Augustus, a Black Chicagoan. I saw the faces of so many activists — including attendees from that year’s Black Youth Project 100 convening — watching her as she chronicled the latest updates from Augustus’ family and friends. With determined eyes, a bullhorn, and an electrifying voice, she invited those who knew the slain man to share about who he was and why they loved him. After hours of rallying and gathering resources for protesters (like ice, milk, and first aid), it felt as if we all breathed a collective sigh of relief. She calmed us while spurring a fire in our hearts.

This was Charlene in action, demonstrating true, remarkable leadership in one of her last months as BYP100’s first National Director. After assuming the role in November 2013, she laid the foundation for the member-based organization to become a queer, feminist political home for young Black activists. She inspired robust dialogue on eschewing the patriarchy and rigorous praxis of accountability. And within its first five years under her leadership, BYP100’s membership (and leadership) swelled, resulting in eight chapters throughout the United States.

Like many feminists, I met Barbara Smith on the page. I read the “Combahee River Collective Statement,” which she co-authored, in a women’s studies course. I did not take note of her name. I was not compelled to research her beyond the merits of the collective, a group of Black feminists and lesbians who gathered and organized in Boston in 1974. She did not call attention to herself; instead, she did the work, as part of a team. Her work speaks to that mission: to bring her sisters to the page and the work, by creating platforms, documents, and publications that would remain long after they had gone.

In her 72 years, Barbara not only cofounded the Combahee River Collective, she helped build a visible Black feminist movement during a period when one did not exist. “Virtually everything I have done has been in service of that mission,” Barbara says, from teaching one of the first courses on Black women writers in the United States in 1973, to building the field of Black women’s studies by asserting that there was and could be such a thing, and cofounding Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press in 1980, the first United States publisher for all women of color to reach a large national audience, which published the second edition of the beloved and groundbreaking anthology This Bridge Called My Back. “Arguably, the history of Black women’s organizing would be very different if none of these interventions had occurred” .

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

(REVIEW) Tongues by Taylor Le Melle, Rehana Zaman and Those Institutions Should Belong to Us, by Christopher Kirubi

In this review, Rhian Williams takes a look at Tongues, a dazzling zine edited by Taylor Le Melle and Rehana Zaman (PSS, 2018), with* Christopher Kirubi’s pamphlet ‘Those Institutions Should Belong to Us’ (PSS).

*I [Rhian] use ‘with’ here in homage to Fred Moten’s use of that preposition in all that beauty (2019) to ‘denote accompaniment[]’. This pamphlet was interleaved in the review copy of Tongues that I received from PSS.

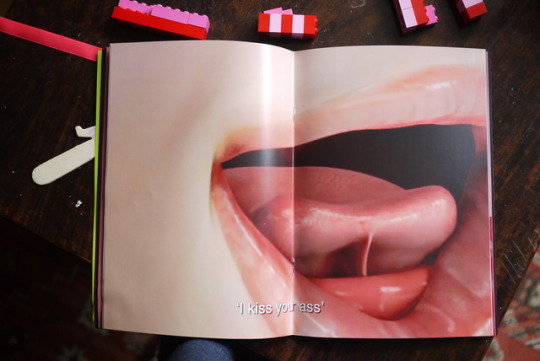

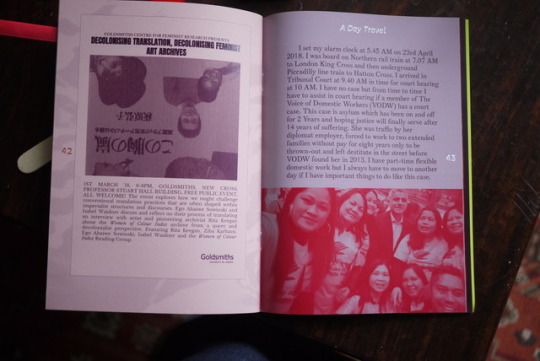

> Onions, lemons, chilli peppers, fractals, hands, patterns, palms pressing, tears, avocados, pomegranate, mouths, finger clicking, deserts. Screenshots, flyers, placards, transcripts, textures, temporalities. Tongues is an urgent gathering in, a zine-type publication that works as a space where Black and Brown women (bringing both their intersections and the tension of distinction) enact memorial, exchange, jouissance, resistance, collaboration, support, listening. Edited by Taylor Le Melle and filmmaker Rehana Zaman, whose work generates many of the dialogic responses interleaved in this collection, this ‘assembly of voices’ was brought together in this particular format in the wake of Zaman’s exhibition, Speaking Nearby, shown at the CCA in Glasgow in 2018. But, as Ainslie Roddick explains, in ‘an attempt to reckon with the trans-collaborative nature of “practice” itself’, Tongues resists academic mechanisms that fall into reiterating the violence of individualism, moving around the figure of the single author/editor to seek to capture ‘a process of thinking with and through the people we work and resist with, acknowledging and sharing the work of different people as practice’ (p. 3). As such, ‘[Tongues’] structure, design and rhythm reflect the work of all the contributors to this anthology who think with one another through various practical, poetic and pedagogical means’ (ibid.). Designed and published by PSS, this is a tactile, sensory production: its aesthetics are post-internet, collage, digi-analogue, liquid-yet-textural, with shiny paper pages that you have to gently peel apart, gleaming around a central pamphlet of matte, heavier paper in mucous-membrane pink and mauve, which itself protects the centrefold glossy mouth-open lick of ‘I kiss your ass’ between the leaves of Ziba Karbassi’s poem, ‘Writing Cells’, here in both Farsi and English (translated with Stephen Watts). Throughout, Tongues reiterates the sensuous, labouring body as political, as partisan.

> Tongues’ multivalency is capacious, nurturing, dedicated to archiving that which is fugitive yet ineluctable; so, inevitably, its overarching principle is labour, is work. The entire collection of essays, response pieces, email exchanges, WhatsApp messages, poetry, transcripts, journaling, and imaginings are testimony to effort and skill, to the determination to keep spaces open for remembrance and for noticing within the ever-creeping demands of production. It is not surprising that this valuable collection is stalked by perilous attenuation, the damage of exhaustion. It is appallingly prescient of the first week of June 2020. Moving my laptop so that I can write whilst also keeping an eye on what I’m cooking for later, setting up my child to listen to an audiobook so that I can try to open up some headspace for listening and responding, nervous about how to spread my ‘being with’ across multiple platforms (my child, my writing, the news, other voices), I am taken by Chandra Frank’s meditative response piece to Zaman’s Tell me the story Of all these things (2017) and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (1982), which vibrates with ‘the potency and liberatory potential of the kitchen’ (p. 9) and movingly seeks to track and honour ‘what it means to both feel and read through a non-linear understanding of subjectivities’ (p. 10). But I only have to turn the page to realise my white safety. I am at home in my kitchen; my space may feel like it has turned into a laboratory for the reproduction of everyday life under lockdown, but it is manifest, it is seen in signed contracts, my subjectivity is grounded on recognition and citizenship. For Sarah Reed, searingly remembered by Gail Lewis in ‘More Than… Questions of Presence’, subjectivity was experienced as brutalisation, manifested posthumously in hashtags, #sayhername. (Reed was found dead in her cell at Holloway Prison in London in February 2016. In 2012 she had been violently assaulted by Metropolitan Police officer James Kiddie; the assault was captured by CCTV footage.) For the women immigrants engaged in domestic work in British homes, as documented here in Marissa Begonia’s vital journaling piece and Zaman’s discussion with Laura Guy, subjectivity is precarity and threat, their dogged labour forced into shadows. Lewis’s piece pivots around a ‘capacity of concern’ generated by ‘the political, ethical, relationship challenge posed by the presence of “the black woman”’ (p. 18), urging that such concern be of the order of care by walking a line with psychoanalysts D. A. Winnicott and Wilfred Bion in recognising that ‘in naming something we begin a journey in the unknown’ (p. 19). If that ‘unknown’ includes understanding how the British state is inimical to the self-determination and safety of Black and Brown women born within its ‘Commonwealth’ borders (#CherryGroce; #JoyGardner; #CynthiaJarrett; #BellyMujinga), and further, how its ‘hostile environment’ policies – named and pursued as such by the British Home Office under Theresa May – are designed specifically to threaten those born elsewhere, by reiterating Britain’s historical enthusiasm for enslavement of non-white labour (see the 2012 visa legislation, discussed here, that, for domestic workers, effectively put a lock on the 2016 ‘Modern Slavery Act’ review before it had even begun), then consider Tongues a demand to get informed. This is a zine about workers and working. It is imperative that we come to terms with what working life in Britain looks like (see the Public Health England report into disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19 – released June 2 2020, censored to remove sections that highlighted the effect of structural racism, but nevertheless evidencing the staggering inequality in death and suffering that is linked to occupation and to citizen status, and therefore tracks race and poverty lines). It is imperative that we scrutinise how ‘popular [and, I would add, Westminster] culture perpetuates a notion of working class identity as a fantasy’ (p. 52) that literally spirits away the bodies undertaking keywork in the UK. The title of Frank’s piece here, ‘Fragmented Realities’, is exquisitely apt.

> Bookended by Roddick’s and Zaman’s radical re-orientating of the apparatus of academia – the introduction that resists assimilating each of the forthcoming pieces under one stable rubric, instead simply listing anonymously a sentence from each contributor in a process of meditative opening up, and ‘A note, before the notes. The end notes’ that counter-academically reveals weaknesses and vulnerabilities, is open to qualification and reframing, is responsive – Tongues constitutes a politics and aesthetics of ‘shift’. Collated after a staged exhibition, anticipating new bodies of work to come, and ultimately punctuated by a pamphlet that segues from reporting on an inspiring event that took place at the Women’s Art Library, Goldsmith’s University of London to imagining a second one in paper (the ‘original’ having been thwarted by bad weather), the entire collection has a productively stuttering relationship with temporality and with presence. As Shama Khanna writes about working groups and reading groups, workshops and pleasure-seeking in gallery spaces, this is the moving ground of the undercommons. It is testament to its intellectual lodestars – Sara Ahmed, Fred Moten, Stefano Harney, and, especially, the eroto-power of Audre Lorde. Along with Christopher Kirubi’s pamphlet, ‘Those Institutions Should Belong to Us’, which comprises a series of seven short ‘prose poems’ documenting the anguish of writing a dissertation from a marginalised perspective, the entire project of Tongues with Those Institutions is to upend academic practice, to recognise the ideological thrust of academic method, to stage fugitive enquiry. Kirubi’s plain sans-serif black font on white pages rehearses the anxious dialectics of interpellation and liberation (‘there is a need to see ourselves reflected in position of agency power and self determination in a world which does not really wish to see us thrive at all’ (part 3)) afforded by their academic obligations, but inarticulacy is a higher form of eloquence:

Even though I know at some point I am going to have to yield to these demands I feel I have to say now that I want to take in this dissertation a position of defending the inarticulate, defending the subjective and defending the incoherent, without having to arrive at a point of defence through theoretically determined foundations, but to feel them.

> Since its structuring principles are those of women’s work, and of Black and Brown experience, nurturing and shielding within the exhaustingly cyclical nature of toiling for recognition, respect, and protection, Tongues dances in the poetics of circles, of loops and feedback, of reciprocity and exchange. Recognising, however, that circularity is also the shape of repetitive strain, Zaman leaves us with a spiralling gesture, in homage to the Haitian spiral, ‘born out of the work of the Spiralist poets’ (p. 61). This ‘dynamic and non-linear’ form insists on the mutuality of the past and contemporary circumstances, is ‘a movement of multiplied or fractured beings, back and forth in time and space demanding accumulation, tumult, and repetition, adamant irresolution and open endedness…’. We are in that spiral now. Such demands must be heard, power must be relinquished, established forms of control – enacted in the streets and on our pages – must be terminated. Writing in early June 2020, this feels precarious; no one is exempt from giving of their strength.

Please pursue further information here. If you are able, these organisations thrive (given the paucity of state support) on donation:

Voice of Domestic Workers: https://www.thevoiceofdomesticworkers.com/

Cherry Groce foundation: https://www.cherrygroce.org/

BBZBLACKBOOK (a digital archive of emerging & established black queer artists): https://bbzblkbk.com/

Reclaim Holloway: http://reclaimholloway.mystrikingly.com/

~

Text: Rhian Williams

Published: 16/6/20

1 note

·

View note

Text

Get to Know ‘AfroHouse’ at Rhythm of Afrika, a Diaspora Dance Party Here to Stay

OCTOBER 14, 2016 BY NICOLE DISSER

(Flyer via Rhythm of Afrika)

It’s rare when a music trend hits at all levels of the listener spectrum, but right now African music is resonating with everyone from pop junkies and passive, whatever’s-playing-at-the-club consumers to crate-diggers with eclectic collections and torrent combers with multiple hard drives devoted to the most obscure sounds they can find.

Drake’s hit song infused with Afropop beats, “One Dance,” was a collaboration with the Nigerian artist Wizkid. The blog Awesome Tapes From Africa has become a cultural phenomenon. And countless reissues, anthologies, even documentaries have appeared, offering a window into the rich histories of High Life, Afrobeat, Zamrock, Nigerian psych-rock of the ’70s, and the thriving punk and metal scenes of South Africa– you name it, really.

Admittedly the current trend– a reductive way of describing what’s really more like a movement, anyway– has been building for a while (Pitchforkcalled it back in 2008). And, yes, “African music” is a massive thing. It encompasses a whole universe of diverse sounds from across an entire continent, after all. But it works in this case because what we’re seeing is a cross-cultural, multi-genre trend that transcends pigeonholing based on tradition, instrumentation, and international borders.

STA7CK (pronounced “Stark”), or Mathieu K., a Cote d’Ivoire-born DJ/producer, is one artist at the forefront of it all, and he can attest to the upswing. “People are really picking up on it. If you pull up the hashtag #Afrobeat or #AfricanHouseMusic on Instagram now, you see people even in Europe dancing to it, people in Russia dancing to these songs,” he said. “It’s crazy. A few years ago you wouldn’t think this would be possible. Now they have Drake doing remixes with Davido, Wizkid.”

(Courtesy of Sta7ck, Rhythm of Afrika)

Mostly recently, he’s played host to Rhythm of Afrika, a monthly dance party that features a rotating cast of other DJs and producers working in a similar vein. The various iterations have gone down at Trans-Pecos and Williamsburg’s the Hangry Garden, and the next one’s happening tomorrow (Friday October 14) at Knockdown Center. This time around, STA7CK is sharing the bill with BLM (Brian Lee McCloud).

The party has been a success both on the ground and amongst critics, having earned a great deal of praise, including a recent shout-out from The New Yorker. The party’s also launched STA7CK’s career both as a musician blending House music with African sounds and, in some ways, a cultural ambassador.

“Things are changing now, people are starting to see these African creators now and African artists, African-American artists, Afro-Euro artists,” he explained.

Even during our conversation this week, STA7CK still seemed to be recovering from the shock of this mega-boost popular reception. But his own life reads like a recipe for the perfect DJ– Mathieu comes from a diverse cross-cultural background which can be traced from Abidjan to Paris, then the Bronx before the Rockaways, and now Bushwick, and has a deep and long-held passion for both West African traditional styles of music and new forms coming from the continent and the diaspora alike.

What STA7CK said he’s most excited about are the endless possibilities for cross-cultural exchange and innovation. Just look at grime music, a varied electronic/jungle genre that started out in East London in the early-aughts and counted influences from Afro-Caribbean and African music such as dancehall and reggae. Grime has grown from a UK phenomenon to an international one, with an active scene in South Africa, which has in turn started a whole new back-and-forth with African cultures.

“So the whole idea behind the event is that we cater to…” he paused. “We cater to everybody, you know?” he laughed.

But the cool thing about the influx of artists like STA7CK is that it’s not a free-for-all expression of globalization, or worse, cultural appropriation. Rhythm of Afrika, in addition to being a dance party, is a network of social media outlets that share content by and about “young Africans in New York City representing Africa and disrupting the stereotype.” Their Facebook calls itself, “A Page About Africa, Africans & The Diaspora* Told by Africans, not the media.”

“I was using Instagram a lot to promote the culture in Africa, because what I was seeing on TV and in the media, I really didn’t like what I was seeing,” STA7CK explained.

This gap between STA7CK’s own experience growing up in West Africa and what he saw and heard about the continent traces all the way back to his childhood after his family moved to Paris and then New York.

“I saw that a lot of Afro-Americans who were born here, they don’t really understand Africa like that,” he said. So when I was a 13-year-old kid, I was just trying to educate people. When I was hanging out with my friends, they’d say, ‘Oh, you live in teepees over there right?’ And I’m like, ‘Yo, we got cities over there! We have dance parties! We have music culture! We have comedy culture! We have everything just like here.’”

(Courtesy of STA7CK, Rhythm of Afrika)

Mathieu missed hanging out at his uncle’s record store back in Cote d’Ivoir, where, he recalled, “Every weekend, he would get new music– music from France, the Caribbean, a lot of traditional African music, so I would pick up that vibe.” But he found new music that he loved right here in New York. “I just grew into the whole hip-hop culture, I really loved R&B, the whole Afro-Caribbean culture, then I also had my cultural background— one of my visions was to put all these things together.”

After a few fits and starts, including founding a talent agency that failed, he decided to focus on his own music, as opposed to promoting that of others. Eventually DJ’ing small private events, including birthday parties, payed off.

He recalled one event where guests kept approaching him with requests that were along the lines of the more predictable dance music heard in clubs all over the city. “And I was like, ‘I don’t know that song.'” Eventually, he fulfilled some of the requests but compromised by blending it with his own style. “Once I finally gave in, the whole crowd went crazy,” STA7CK said. “I noticed that nobody was doing this kind of party, and I was like, Hey, I’m going to pull this African House together, I’m going to put Afrobeat together and traditional African music, and music of the diaspora.”

Now, STA7CK said: “DJs usually beg me for my setlist, I tell them, ‘That’s not how it works, you have to go dig some crates, bruh,'” said.

His protectiveness is understandable since Mathieu’s been preaching this stuff for years, praising West African performers and a vast array of music with firm roots in the continent only to fall on deaf ears. Even then, he kept at it. “Yes, I work 24/7,” he admitted.

Instead of wasting his energy calling out other performers for appropriation or bandwagoning, STA7CK is focusing on his own projects. Eventually, he said, he even wants to organize a “Burning Man in the jungle.” If they’re willing to go all the way out to the middle-of-nowhere hot-ass desert once a year and face tech bros and dust storms for debauchery, psychedelics, and maybe cool music (I’m not even sure, really), then a few would probably be willing to schlep it out to another kind of steamy locale to drown in AfroHouse music and drool on parrots.

Clearly, the scene created by STA7CK and other artists through Rhythm of Afrika is much more than a trend. While big pop names have recruited artists from the diaspora and picked up on the “nowness” of Afropop, Afrobeat, and now AfroHouse (and in some cases co-opted it) the hit songs they’re churning out haven’t overshadowed the more legit artists who have a real cultural interest and lasting devotion to these musical traditions.

(Courtesy of STA7CK, Rhythm of Afrika)

That’s partly owed to a Brooklyn/NYC music scene with outlets, venues, and individuals that are working for real inclusivity and true experimentation. People like STA7CK are ensuring that this “trend” is actually super resilient, and more so that it remains a two-way street. On the one hand, the unfamiliar get some excellent opportunities to learn about musical cultures different from their own in ways that go far deeper than simply owning a Witch record (guilty) and being “super into” Nigerian psychedelic rock right now (double guilt). On the other hand, Rhythm of Afrika acts as a platform for others to share their own culture and encourages the blending and collaboration of various musical styles, as opposed to building protective wall around them or outright stealing them.

This cross-cultural, cross-generational, boundary-less sort of exchange can only continue in STA7CK’s view, since he believes that the well of talent here is almost bottomless: “The more I play, the more like-minded dope, young New Yorkers I meet.”

#music#fashion#lifestyle#Interviews#Arts & Culture#business#videos#news#film#sports#events#ArtAndCultures

0 notes