#hancockstories

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

1995 | Amy Bess Miller in her office at Hancock Shaker Village

Powerhouse. Demure demeanor and iron will. This is how Amy Bess Miller (1912-2003), founder and first president of Hancock Shaker Village, is remembered for her extraordinary effort to preserve the City of Peace as a living history museum. By many accounts, she saved the Village from certain destruction in 1960, when competitive bids for the property were placed by a youth correctional facility, the Pittsfield Airport, and a horseracing outfit with mafia connections that proposed to raze the entire campus except the iconic Round Stone Barn.

An intrepid and steadfast leader, Amy Bess and her husband Lawrence K. “Pete” Miller (1907-1991) struck an agreement with the Shaker Ministry in Canterbury, NH, to secure the future of Hancock Shaker Village in perpetuity. Together, they created a captivating setting to engage ideas and artifacts of the Shakers in a way that “breathes the spirit of the original culture.”

Amy Bess Miller served as president of Hancock Shaker Village from 1960 - 1991, and she continued to be an active presence at the Village until the early-2000s.

1 note

·

View note

Text

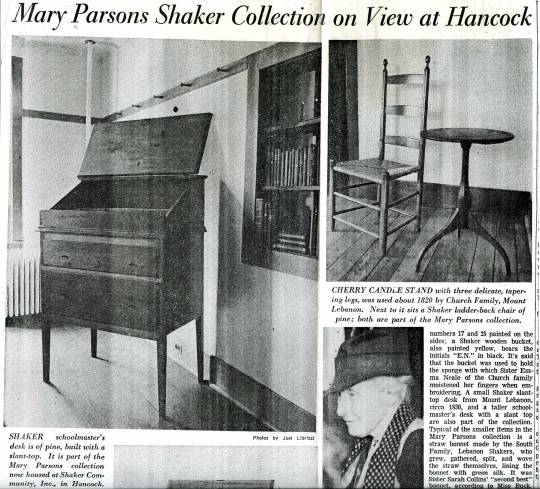

1962 | The Mary Parsons Collection

John E. Parsons died in 1915, leaving his fortune and property to his six children. To his two unmarried daughters, Mary (1863-1940) and Gertrude (1870-1927), he left Stonover Estate in Lenox, Massachusetts. The sisters, then in their 50s, immediately set out on adventures to China and Europe and remodeled the Victorian manor into a French country home with yellow stucco and a sprawling terrace for summer parties. The lavish parties they hosted included after-dinner lectures from academics, artists, and revolutionaries including Aleksandr Kerensky (1881-1970), a key figure in the Russian Revolution (1917).

After Gertrude’s death, Parsons threw herself into her passion for conservation and in 1929 she founded the 350-acre Pleasant Valley Sanctuary in Lenox. She opened the trails on her estate to fellow nature enthusiasts and in the 1930s reintroduced beavers to the state.

Between creating a sanctuary and hosting a weekly lecture series, Parsons befriended the brothers and sisters at the local Shaker communities. In 1938 she purchased a collection of furniture and objects directly from the Shakers to decorate a bird sanctuary barn on her property. Twenty years after her death Shaker Community, Inc. acquired 50 of those pieces. Parsons was fondly remembered by her friend Amy Bess Miller as having “not one pretense about her.”

0 notes

Text

1962 | The Vincent Newton Collection

Vincent Newton was a friend of the Millers and the Andrewses and an early supporter of Hancock Shaker Village. Like many collectors whose objects form the foundational collection of the museum, he knew the Shakers personally. He had a summer home in Charlemont, Massachusetts, and often visited Hancock. Newton continued to visit the Village after it became a museum and would often delight the staff and trustees with his personal stories of the Shakers.

The fledgling Shaker Community, Inc. was looking for artifacts to fill their numerous buildings and in 1962 a portion of Newton’s collection became available. A curated selection of objects, many with Hancock provenance, were chosen by Andrews and presented to the trustees for purchase. Upon approval, Andrews rented a truck and retrieved the new acquisitions himself.

Amy Bess Miller heard that Newton was looking to sell two gift drawings from his collection and she inquired about purchasing both. He told her that he had already promised one to the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum so instead she convinced him to let her pick first and selected "A Present from Mother Lucy to Eliza Ann Taylor" by Polly Jane Reed.

Photo: "A Present from Mother Lucy to Eliza Ann Taylor," by Polly Jane Reed. Collection of Hancock Shaker Village.

0 notes

Text

1842 | Holy Feast Days on Mount Sinai

Out of the woods just North of Hancock Shaker Village rises Shaker Mountain. One mile up the trail, over a stream and through lush greenery, lies a small clearing, known to the Shakers as the Holy Feast Ground, or Mount Sinai. In 1842, the Hancock Shakers began using this remote clearing in the forest for their Holy Feast Days. In the center, they erected a monument called the “fountain stone,” which offered “the water of life.” Family by family, the Shakers hiked up to this site to gather around the fountain and share a spiritual worship experience. The Shakers exchanged “spiritual gifts” -- songs, dances, and verbal testimonies inspired by the divine. They laid out a “spiritual feast,” not a feast of actual food and drink but, instead, a feast of exotic foods and wine sent from the spirit world.

This worship practice represents a brief shift in Shaker culture towards spiritual expression that occurred during the period of “Mother’s Work,” also known as the “Era of Manifestations.”

Image: David R. Lamson, Two Years Experience Among The Shakers (1848)

1 note

·

View note

Text

1943 | The Hancock Shaker Cemetery Monument

Sitting on U.S. Route 20, just opposite the Trustees’ Office & Store, perches a lone monument surrounded by a wrought iron fence. This is the Shaker Cemetery; however, it is not the *first* cemetery used by Hancock Shakers. Beginning in the 1780s, early community members were interred at the Shaker burial ground near the former site of the West Family. One of the earliest families to convert to Shakerism, the Tallcotts, brought with them their property and land, including their family burial plot. The Hancock Shakers were buried in this same plot until the “Winter Fever” epidemic of 1813 that, unfortunately, necessitated the establishment of a larger plot of land in which to bury the dead.

In 1943, the nearly 250 individual Shaker gravestones erected at the Hancock Cemetery were replaced with the single monument you can see here today. The monument honors all the Shakers buried there. Its inscription reads:

In loving memory Of members of the Shaker Church Who dedicated their lives To God and to the good of Humanity Passed to immortality.

Photos: Ben Garver

#hancockshakervillage#hancockstories#hancockfromhome#handstohancock#theshakers#thecityofpeace#deathrituals#cemetery

0 notes

Text

1962 | The Charles Sheeler Collection

Charles Sheeler (1883-1965) rose to fame in the 1920s as part of the Precisionism art movement. His realistic paintings and photographs of factories, turbines, and barns have minimal detail, focusing instead on the shape, simplicity, and geometry of architecture and industrial design. Along with fellow American modernists, Sheeler greatly admired the Shaker aesthetic. He described their architecture as examples of “utilitarian design” and “rightness of proportion,” often painting and photographing the Shaker sites at New Lebanon, New York, and Hancock, Massachusetts in the 1930s.

Sheeler also collected Shaker furniture for his home, and 15 of those pieces found their way into the collections of Hancock Shaker Village. The objects first arrived at the Village as part of a loan in 1962 and, subsequently, were purchased in 1963 for $10,000. When Sheeler’s gallerist offered to sell the collection to the Village, Amy Bess Miller raised the funds by calling on friends and collectors to donate -- notably the Rockerfellers. Though the Charles Sheeler Collection is small, the pieces are exceptional examples of Shaker design, and many have clear Hancock provenance. Unfortunately, Sheeler never saw his objects on display back home in the Brick Dwelling, he died in 1965 of a stroke before he could visit the Village.

Photo: The Sheeler Collection arriving at the Village in 1962. The handwriting is by Amy Bess Miller, who pasted this photo into one of her many scrapbooks.

#hancockstories#hancockshakervillage#theshakers#cityofpeace#charlessheeler#americanmodernism#handstohancock#shakerstyle#museumcollections#historichousemuseum

0 notes

Text

1925 | Eldress Caroline Helfrich and her Chickens

https://soundcloud.com/user-925329379/eldress-caroline-and-her-chickens

This memory of Eldress Caroline Helfrich (1837-1929) and the Hancock chickens was recorded by Olive Hayden Austin (1896-1987), who lived with the Hancock Shakers from 1903 to 1935.

1 note

·

View note

Text

1968 | Fire in the Ministry

The spiritual life of each Shaker community was overseen by two Elders and Eldresses who, together, constituted the Ministry. The Ministry Shop served as their workspace -- the Elders and Eldresses were under the same obligation to perform handwork as the brethren and sisters in their care. The Ministry Shop at Hancock is located on the north side of route 20. After the Hancock Ministry was abolished on June 18, 1893, the Shop served as home to a group of Shaker sisters who were relocated to Hancock following the closure of the Enfield, CT community.

In 1968, when the Ministry Shop was awaiting its museum-era restoration, a fire broke out. The Hancock and Pittsfield Fire Departments responded quickly but, even so, the north wing of the building was entirely destroyed. The Shop had been used as a carpentry and cabinet shop, and much of the material inside was turned to ash. Today, evidence of the fire can still be seen in the attic, where charred beams remind us of this significant occurrence.

#hancockshakervillage#hancockfromhome#handstohancock#hancockstories#theshakers#thecityofpeace#notesabouthome

0 notes