#googbook

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

To save the news, shatter ad-tech

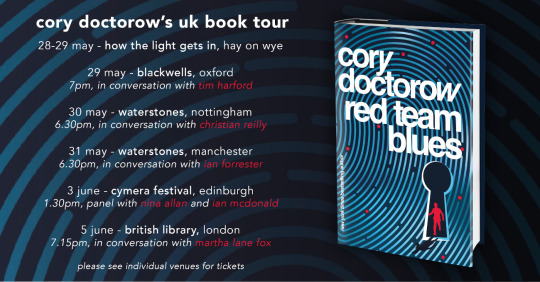

I’m coming to the HowTheLightGetsIn festival in HAY-ON-WYE with my novel Red Team Blues:

Sun (May 28), 1130h: The AI Enigma

Mon (May 29), 12h: Danger and Desire at the Frontier

I’m at OXFORD’s Blackwell’s on May 29 at 7:30PM with Tim Harford.

Then it’s Nottingham, Manchester, London, Edinburgh, and Berlin!

Big Tech steals from news, but what it steals isn’t content. Talking about the news isn’t theft, and neither is linking to it, or excerpting it. But stealing money? That’s definitely theft.

Big Tech steals money from the news media. 51% of every ad-dollar is claimed by a tech intermediary, a middleman that squats on a chokepoint between advertisers and publishers. Two companies — Google and Meta — dominate this sector, and both of these companies are “full-stack” — which is cutesy techspeak for “vertical monopoly.”

Here’s what that means: when an advertiser wants to place an ad, it contracts with the “demand-side platform” (DSP) to seek out a chance to put an ad in front of a user based on nonconsensually gathered surveillance data about a potential customer.

The DSP contacts an ad-exchange — a marketplace where advertisers bid against each other to cram their ads into the eyeballs of a user based on surveillance data matches.

The ad-exchange receives a constant stream of chances to place ads. This stream is generated by the “supply-side platform” (SSP), a service that represents publishers who want to sell ads.

Meta/Facebook and Google both the “full stack” of ads: they represent buyers and sellers, and they operate the marketplace. When the sale closes, Googbook collects a commission from the advertiser, another from the publisher, and a fee for running the market. And of course, Google and Facebook are both publishers and advertisers.

This is like a stock exchange where one company operates the exchange, while serving as broker and underwriter for every stock bought or sold, while owning huge amounts of stock in many of the listed companies as well as owning the largest companies on the exchange outright.

It’s like a realtor representing the buyer and the seller, while buying and selling millions of homes for its own purposes, bidding against its buyers and also undercutting its sellers, in an opaque auction that only it can see.

It’s a single lawyer representing both parties in a divorce, while serving as judge in divorce court, while trying to match one of the divorcing parties on Tinder.

It’s incredibly dirty. These companies gobble up the majority of every ad dollar in commissions and other junk fees, and they say it’s because they’re just really danged good at buying and selling ads. Forgive me if I sound cynical, but I think it’s a lot more likely that they’re good at cheating.

We could try to make them stop cheating with a bunch of rules about how a company with this kind of gross conflict of interest should conduct itself. But enforcing those rules would be hard — merely detecting cheating would be hard. A simpler — and more effective — approach is to simply remove the conflict of interest.

Writing on EFF’s Deeplinks blog this week, I explain how the AMERICA Act — introduced by Senator Mike Lee, with bipartisan cosponsors from Elizabeth Warren to Ted Cruz (!) — can do just that:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/05/save-news-we-must-shatter-ad-tech

The AMERICA Act would require the largest ad-tech companies to sell off two of their three ad-tech divisions — they could be a buyer’s agent, a seller’s agent or a marketplace — but not all three (not even two!). This is in keeping with a well-established principle in antitrust law: “structural separation,” the idea that a company can be a platform owner, or a platform user, but not both.

In the heyday of structural separation, railroad companies were banned from running freight companies that competed with the firms that shipped freight on their rails. Likewise, banks were banned from owning companies that competed with the businesses they loaned money to. Basically, the rule said, “If you want to be the ref in this game, you can’t own one of the teams”:

https://www.eff.org/es/deeplinks/2021/02/what-att-breakup-teaches-us-about-big-tech-breakup

Structural separation acknowledges that some conflicts of interest are so consequential and so hard to police that they shouldn’t exist at all. A judge won’t hear a case if they know one of the litigants — and certainly not if they have a financial stake in the outcome of the case.

The ad-tech duopoly controls a massive slice of the ad market, and holds in its hands the destiny of much of the news and other media we enjoy and rely on. Under the AMERICA Act’s structural separation rule, the obvious, glaring conflicts of interest that dominate big ad-tech companies would be abolished.

The AMERICA Act also regulates smaller ad-tech platforms. Companies with $5–20b in turnover would have a duty to “act in the best interests of their customers, including by making the best execution for bids on ads,” and maintain transparent systems that are designed to facilitate third-party auditing. If a single company operated brokerages serving both buyers and sellers, it would need to create firewalls between both sides of the business, and would face stiff penalties for failures to uphold their customers’ interests.

EFF’s endorsement of the AMERICA Act is the first of four proposals we’re laying out in a series on saving news media from Big Tech. We introduced those proposals last week in a big “curtain raiser” post:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/04/saving-news-big-tech

Next week, we’ll publish our proposal for using privacy law to kill surveillance ads, replacing them with “context ads” that let publishers — not ad-tech — control the market.

Catch me on tour with Red Team Blues in Hay-on-Wye, Oxford, Manchester, Nottingham, London, and Berlin!

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/25/structural-separation/#america-act

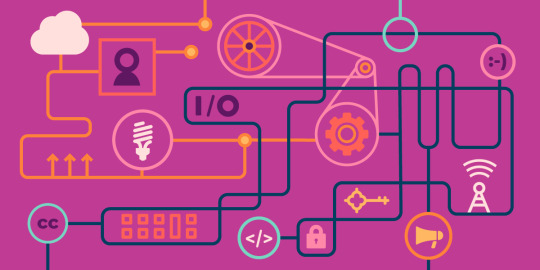

EFF's banner for the save news series; the word 'NEWS' appears in pixelated, gothic script in the style of a newspaper masthead. Beneath it in four entwined circles are logos for breaking up ad-tech, ending surveillance ads, opening app stores, and end-to-end delivery. All the icons except for 'break-up ad-tech' are greyed out.

Image: EFF https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/05/save-news-we-must-shatter-ad-tech

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#how to save the news#money talks bullshit walks#googbook#ted cruz#news#big tech#eff#monopoly#structural separation#america act#link taxes#mike lee#elizabeth warren#ad-tech

75 notes

·

View notes

Note

Bing is to Google as Tumblr is to Facebook I'm DEAD.

//Any guesses as to what the other three Google pairs might be??? 👀👀👀// - Cap

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

To save the news, ban surveillance ads

Tonight (May 31) at 6:30PM, I’m at the MANCHESTER Waterstones with my novel Red Team Blues, hosted by Ian Forrester.

Tomorrow (Jun 1), I’m giving the Peter Kirstein Lecture for UCL Computer Science in LONDON.

Then it’s Edinburgh, London, and Berlin!

Big Tech steals from the news, but what it steals isn’t content — it steals money. That matters, because if we create pseudo-copyrights over the facts of the news, or headlines, or snippets to help news companies bargain with tech companies, we make the news partners with the tech companies, rather than watchdogs.

How does tech steal money from the news? Lots of ways! One important one: tech steals ad revenue. 51% of every ad dollar gets gobbled up by tech companies — primarily the cozy, collusive ad-tech duopoly of Google/Facebook (AKA Googbook). If we can shatter the market power of the concentrated ad-tech industry, news companies would go back to getting 80–90% of the ad revenue their reporting generated, which would pay for more reporting.

There’s lots to like about fixing ads. For one thing, a fair ad marketplace would benefit all news reporting, not just the largest news companies — which are dominated by private equity-backed chains and right-wing billionaires who have repeatedly shown that any additional revenues will go to pay shareholders, not more reporters. Fair ads would also provide an income for reporters who strike out on their own, covering local politics or specific beats, without making themselves sharecroppers for Big Media.

One way to fix ads would be to break up the ad-tech “stacks.” Googbook both operate impossibly conflicted ad-placement businesses in which they bargain with themselves on behalf of both advertisers and publishers, with the winners always being the tech companies. The AMERICA Act from Senator Mike Lee would force ad giants to divest themselves of business units that create conflicts of interest. It’s popular, bipartisan legislation — and I do mean bipartisan; its backers include Elizabeth Warren and Ted Cruz! I wrote about the AMERICA Act and the role it will play in saving news from tech for EFF’s Deeplinks Blog last week:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/05/save-news-we-must-shatter-ad-tech

This week, I’ve got a followup on Deeplinks about another important way to unrig the ad market: banning surveillance ads:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/05/save-news-we-must-ban-surveillance-advertising

Even if we break up the ad-tech stacks, ads will still be bad for the news — and for the public. That’s because the dominant form of digital ads is “behavioral advertising” — the ad-tech sector’s polite euphemism for ads based on spying. You know these ads: you search for shoes and then every website you land on is plastered in shoe ads.

Surveillance ads require a massive, multi-billion-dollar surveillance dragnet, one that tracks you as you physically move through the world, and digitally, as you move through the web. Your apps, your phone and your browser are constantly gathering data on your activities to feed the ad-tech industry.

This data is incredibly dangerous. There’s so much of it, and it’s so loosely regulated, that every spy, cop, griefer, stalker, harasser, and identity thief can get it for pennies and use it however they see fit. The ad-tech industry poses a risk to protesters, to people seeking reproductive care, to union organizers, and to vulnerable people targeted by scammers.

Ad-tech maintains the laughable pretense that all this spying is consensual, because you clicked “I agree” on some garbage-novella of impenatrable legalese that no one — not even the ad-tech companies’ lawyers — has ever read from start to finish. But when people are given a real choice to opt out of digital spying, they do. Apple gave Ios users a one-click opt-out of in-app tracking and 96% of users clicked it (the other 4% must have been confused — or on Facebook’s payroll). The decision cost Facebook $10b in the first year. You love to see it:

https://www.cnbc.com/2022/02/02/facebook-says-apple-ios-privacy-change-will-cost-10-billion-this-year.html

But here’s the real punchline: Apple blocked Facebook from spying on its customers, but Apple kept spying on them, just as invasively as Facebook had, in order to target them with Apple’s own ads:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/14/luxury-surveillance/#liar-liar

The thing that stops companies from spying on us isn’t the strength of their character, it’s the discipline imposed by regulation and competition — the fear that they’ll get fined more than they make from spying, and the fear that they’ll lose so much business from spying that they’ll end up in the red.

Which is why we need a legal ban on ads, not mere platitudes on billboards advertising companies’ “respect” for our privacy. The US is way overdue for a federal privacy law with a private right of action, which would let you and me sue the companies who violated it, even if no public prosecutor was willing to go to bat for us:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/01/you-should-have-right-sue-companies-violate-your-privacy

A privacy law that required companies to get your affirmative, enthusiastic, ongoing, specific, informed consent to gather and process your personal data would end surveillance ads forever. Despite the self-serving nonsense the ad-tech industry serves up about people “liking relevant ads,” no one wants to be spied on. 96% of Ios users don’t lie.

A ban on surveillance ads wouldn’t just serve the public, it would also save the news. The alternative to surveillance ads is context ads: ads based on what a reader is reading, rather than what that reader was doing. Context-based ad marketplaces ask, “What am I bid for this Pixel 6 user in Boise who is reading about banana farming?” instead of “What am I bid for this 22 year old man who recently searched for information about suicidal ideation and bankruptcy protection?”

Context ads perform a little worse than surveillance ads — by about 5%:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/04/29/taken-in-context/#creep-me-not

So presumably advertisers won’t pay as much for context ads as they do for behavioral targeting. But that doesn’t mean that the news will lose money. Because context ads favor publishers over ad-tech platforms — no publisher will ever know as much about internet users as spying ad-tech giants do, but no tech company will ever know as much about a publisher’s content as the publisher does.

Behavioral ad marketplaces have high barriers to entry, requiring troves of surveillance data on billions of internet users. They are naturally anticompetitive and able to command a much higher share of each ad dollar than a contextual ad service (which would have much more competiition) could.

On top of that: if behavioral advertising was limited to people who truly consented to it, 96% of users would never see an ad!

So contextual ads will show up for more users, and more of the money they generate will land in news publishers’ pockets. If context ads fetch less money per ad, the losses will be felt by ad-tech companies, not publishers.

Finally: publishers who join the fight against surveillance ads won’t be alone — they’ll be joining with a massive, popular movement against commercial surveillance. The news business is — and always has been — a niche subject, of burning interest to publishers, reporters, and a small minority of news junkies. The news on its own is a small fry in policy debates. But when it comes to killing surveillance ads, the news has a class alliance with the mass movement for privacy, and together, they’re a force to reckon with.

My article on killing surveillance ads is part three of an ongoing, five-part series for EFF on how we save the news from tech. The introduction, which sets out the whole series, is here:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/04/saving-news-big-tech

The final two parts will come out over the next two weeks, and then we’re going to publish the whole thing as a PDF that suitable for sharing. Watch this space!

Catch me on tour with Red Team Blues in Manchester, Edinburgh, London, and Berlin!

[Image ID: EFF's banner for the save news series; the word 'NEWS' appears in pixelated, gothic script in the style of a newspaper masthead. Beneath it in four entwined circles are logos for breaking up ad-tech, ending surveillance ads, opening app stores, and end-to-end delivery. All the icons except for 'ending surveillance ads' are greyed out.]

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/31/context-ads/#class-formation

Image: EFF https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/05/save-news-we-must-ban-surveillance-advertising

CC BY 3.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#class formation#ad-tech#context ads#news#gdpr#big tech#eff#monopoly#how to save the news#link taxes

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

How monopoly enshittified Amazon

In Bezos’s original plan, the company called “Amazon” was called “Relentless,” due to its ambition to be “Earth’s most customer-centric company.” Today, Amazon is an enshittified endless scroll of paid results, where winning depends on ad budgets, not quality.

Writing in Jeff Bezos’s newspaper The Washington Post, veteran tech reporter Geoffrey Fowler reports on the state of his boss’s “relentless” commitment to customer service. The state is grim.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/interactive/2022/amazon-shopping-ads/

Search Amazon for “cat beds” and the entire first screen is ads. One of them is an ad for a dog carrier, which Amazon itself manufactures and sells, competing with the other sellers who bought that placement.

Scroll down one screen and you get some “organic” results — that is, results that represent Amazon’s best guess at the best products for your query. Scroll once more and yup, another entire screen of ads, these ones labeled “Highly rated.” One more scroll, and another screenful of ads, one for a dog product.

Keep scrolling, you’ll keep seeing ads, including ads you’ve already scrolled past. “On these first five screens, more than 50 percent of the space was dedicated to ads and Amazon touting its own products.” Amazon is a cesspit of ads: twice as many as Target, four times as many as Walmart.

How did we get here? We always knew that Amazon didn’t care about its suppliers, but being an Amazon customer has historically been a great deal — lots of selection, low prices, and a generous returns policy. How could “Earth’s most customer-centric” company become such a bad place to shop?

The answer is in Amazon’s $31b “ad” business. Amazon touts this widely, and analysts repeat it without any critical interrogation, proclaiming that Amazon is catching up with the Googbook ad-tech duopoly. But nearly all of that “ad” business isn’t ads at all — it’s payola.

https://pluralistic.net/2022/02/27/not-an-ad/#shakedowns

Amazon charges its sellers billions of dollars a year through a gladiatorial combat where they compete to outspend each other to see who’ll get to the top of the search results. May the most margin-immolating, deep-pocketed spender win!

Why would sellers be willing to light billions of dollars on fire to get to the top of the Amazon search results?

Prime.

Most of us have Amazon Prime. Seriously — 82% of American households! Prime users only shop on Amazon. Seriously. More than 90% of Prime members start their search on Amazon, and if they find what they’re looking for, they stop there, too.

If you are a seller, you have to be on Amazon, otherwise no one will find your stuff and that means they won’t buy it. This is called a monopsony, the obscure inverse of monopoly, where a buyer has power over sellers.

But monopoly and monopsony are closely related phenomena. Monopsonies use control over buyers — the fact that we all have Prime — to exert control over sellers. This lets them force unfavorable terms onto sellers, like deeper discounts. In theory, this is good for use consumers, because prices go down. In practice, though…

Back in June 2021, DC Attorney General Karl Racine filed an antitrust suit against Amazon, because the company had used its monopoly over customers to force such unfavorable terms on sellers that prices were being driven up everywhere, not just on Amazon:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/06/01/you-are-here/#prime-facie

Here’s how that works: one of the unfavorable terms Amazon forces on sellers is “most favored nation” status (MFN), which means that Amazon sellers have to offer their lowest price on Amazon — they can’t sell more cheaply anywhere else.

Then Amazon hits sellers with fees. Lots of fees:

Fees to be listed on Prime (without which, your search result is buried at the bottom of an endless scroll):

Fees for Amazon warehouse fulfillment (without which, your search result is buried at the bottom of an endless scroll)

And finally, there’s payola — the “ads” you have to buy to outcompete the other people who are buying ads to outcompete you.

All told, these fees add up to 45% of the price you pay Amazon — sometimes more. Companies just don’t have 45% margins, because they exist in competitive markets. If I’m selling a bottle of detergent at a 45% markup, my rival will sell it at 40%, and then I have to drop to 35%, and so on.

But everyone has to sell on Amazon, and Amazon takes their 45% cut, which means that all these sellers have to raise prices. And, thanks to MFN, the sellers then have to charge the same price at Walmart, Target, and your local mom-and-pop shop.

Amazon’s monopoly (control over buyers) gives it a monopsony (control over sellers), which lets it raise prices everywhere, at Amazon and at every other retailer, even as it drives the companies that supply it into bankruptcy.

Amazon is no longer a place where a scrappy independent seller can find an audience for its products. In order to navigate the minefield Amazon lays for its sellers (who have no choice but to sell there), these indie companies are forced to sell out to gators (aggregators), which are now multi-billion-dollar businesses in their own right:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/02/10/monopoly-begets-monopoly/#gator-ade

This brings me back to the enshittification of Amazon search, AKA late-stage (platform) capitalism. Amazon’s dominance means that many products are now solely available on the platform. With the collapse of both physical and online retail, Prime isn’t so much a choice as a necessity.

Amazon has produced a planned economy run as capriciously as a Soviet smelting plant, but Party Secretary Bezos doesn’t even pretend to be a servant of the people. From his lordly seat aboard his penis-rocket, Bezos decides which products live and which ones die.

Remember that one of those search-results for a cat-bed was a product for dogs? Remember that Amazon made that dog product? How did that end up there? Well, if you’re a seller trying to make a living from cat-beds, your ad-spending is limited by your profit margin. Guess how much it costs Amazon to advertise on Amazon? Amazon is playing with its own chips, and it can always outbid the other players at the table.

Those Amazon own-brand products? They didn’t come out of a vacuum. Amazon monitors its own sellers’ performance, and creams off the best of them, cloning them and then putting its knockoffs above of the original product in search results (Bezos lied to Congress about this, then admitted it was true):

https://nypost.com/2021/10/18/jeff-bezos-may-have-lied-to-congress-about-amazon-practices-reps/

If you’ve read Chokepoint Capitalism, Rebecca Giblin’s and my new book about market concentration in the entertainment industry, this story will be a familiar one. You’ll recall that Amazon actually boasts about this process, calling it “the flywheel”:

https://twitter.com/rgibli/status/1561761732108107777

Everything that Amazon is doing to platform sellers, other platforms are doing to creators. You know how Amazon knocks off its sellers’ best products and then replaces them with its clones? That’s exactly what Spotify does to the ambient artists in its most popular playlists, replacing them with work-for-hire soundalikes who aren’t entitled to royalties.

You can learn more about how Spotify rips off its performers in the Chokepoint Capitalism chapter on Spotify; we made the audiobook version of that chapter a Spotify exclusive (it’s the only part of the book you can get on Spotify):

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/12/streaming-doesnt-pay/#stunt-publishing

Entertainment and tech companies all want to be the only game in town for their creative labor force, because that lets them turn the screws to those workers, moving value from labor to shareholders.

Amazon is also the poster-child for this dynamic. For example, its Audible audiobook monopoly means that audiobook creators must sell on Audible, even though the #AudibleGate scandal revealed that the company has stolen hundreds of millions of dollars from these creators. (Our chapter on Audiblegate is the only part of our audiobook on Audible!)

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/07/audible-exclusive/#audiblegate

Then there’s its Twitch division, where the company just admitted that it had been secretly paying its A-listers 70% of the total take for their streams. The company declared this to be unfair when the plebs were having half their wages clawed back by Amazon, so they fixed it by cutting the A-listers’ pay.

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/22/amazon-vs-amazon/#pray-i-dont-alter-it-further

Twitch blamed the cut on the high cost of bandwidth for streaming. If that sounds reasonable to you, remember: Twitch buys its bandwidth from Amazon. As Sam Biddle wrote, “Amazon is charging Amazon so much money to run the business via Amazon that it has no choice but to take more money from streamers.”

https://twitter.com/samfbiddle/status/1572667269284777984

As Bezos suns himself aboard his yacht-so-big-it-has-a-smaller-yacht, we ask him to referee a game where he also owns one of the teams. Over and over again, he proves that he is not up to the task. Either his “relentless” customer focus was a sham, or the benefits of cheating are too tempting to ignore.

Historically, we understood that businesses couldn’t be trusted to be on both sides of a transaction. The “structural separation” doctrine is one of the vital pieces of policy we’ve lost over 40 years of antitrust neglect. It says that important platforms can’t compete with their users.

https://locusmag.com/2022/03/cory-doctorow-vertically-challenged/

For example, banks couldn’t own businesses that competed with their commercial borrowers. If you own Joe’s Pizza and your competitor is Citibank Pizza and you both have a hard month and can’t make your payment, will you trust that Citi called in your loan but not Citibank Pizza’s because they had a more promising business?

Today, all kinds of businesses have been credibly accused of self-preferencing: Google and Apple via their App Stores, Spotify via its playlists, consoles via their game stores, etc. Legislators have decided that the best way to fix this isn’t structural separation, but rather, rules against self-preferencing.

Under these rules, companies will have to put “the best” results at the top of their listings. This is doomed. When Apple says it put its own ebook store ahead of Bookshop.org’s app because it sincerely believes Apple Books is “better,” how will we argue with this? Maybe Apple really does believe that. Maybe it doesn’t. Maybe it does, but only because of motivated reasoning (“It is difficult to get a product manager to understand something, when their bonus depends on them not understanding it”).

The irony here is that these companies’ own lawyers know that a sincere promise of fairness is no assurance that your counterparty will act honorably. If the judge in Apple v. Epic was a major shareholder in Epic, or the brother-in-law of Epic’s CEO, Apple’s lawyers would bring down the roof demanding a new judge — even if the judge promised really sincerely to be neutral.

https://marker.medium.com/moral-hazard-and-monopoly-42e30eb159a8

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter if Amazon’s enshittification is because Bezos was a cynic or because he sold out. Once Amazon could make more money by screwing its customers, that screw-job became a fait accompli. That’s why it’s so important that the FTC win its bid to block the Activision-Microsoft merger:

https://www.politico.com/news/2022/11/23/exclusive-feds-likely-to-challenge-microsofts-69-billion-activision-takeover-00070787

The best time to prevent monopoly formation was 40 years ago. The second best time is now.

Anti-monopoly measures are slow and ponderous tools, but when it comes to tech companies, we have faster, more nimble ones. If we want to make it easy to compete with Amazon, we could — for example — use Adversarial Interoperability to turn it into a dumb pipe:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/08/01/dumb-pipes/#original-asin

That is, we could let local merchants use Amazon’s ASIN system to tag their own inventory and produce a realtime database. Customers could browse Amazon to find the things they wanted, with a browser plugin that turned “Buy It Now” into “Buy It Now at Joe’s Hardware”:

https://doctorow.medium.com/view-a-sku-32721d623aee

But this only works to the extent that Amazon’s search isn’t totally enshittified. To that end, Fowler has a few modest proposals of his own, like requiring that at least 50% of the first six screens be given over to real results, not ads.

“Perhaps 50 percent sounds like a lot to you? But even that rule would force Amazon to show us at least some of the most-relevant results on the first screen of our device…Amazon wouldn’t comment on this suggestion.”

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't believe Obama's Big Tech criti-hype

Obama’s Stanford University speech this Thursday (correctly) raised the alarm about conspiratorial thinking, and (correctly) identified that Big Tech was at the center of that rise — and then (wildly incorrectly) blamed “the algorithm” for it.

https://thehill.com/policy/technology/3382803-obama-points-finger-at-tech-companies-for-disinformation-in-major-speech/

Obama was committing the sin of criti-hype, Lee Vinsel’s incredibly useful term for criticism that repeat the self-serving myths of the subject of the critique. Every time we say that Big Tech is using machine learning to brainwash people, we give Big Tech a giant boost:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/02/euthanize-rentiers/#dont-believe-the-hype

You may have heard that the core of Big Tech’s dysfunction comes from the ad-supported business model: “If you’re not paying for the product, you’re the product.” This is a little oversimplified (any company that practices lock-in and gouges on repair, software and parts treats its customer as the product, irrespective of whether they’re paying — c.f. Apple and John Deere), but there’s an important truth to it.

The hundred of billions that Google and Facebook (or Meta, lol) rake in every year do indeed come from ads. That’s not merely because they have a duopoly that has cornered the ad market — it’s also because they charge a huge premium to advertise on their platforms:

https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/online-platforms-and-digital-advertising-market-study

Why do advertisers pay extra to place ads with Googbook? Because Googbook swears that their ads work really well. They say that they can use machine learning and junk-science popular psychology (“Big 5 Personality Types,” “sentiment analysis,” etc) to bypass a user’s critical faculties and control their actions directly. It boils down to this: “Our competition asks consumers to buy your product, we order them to.”

This is a pretty compelling pitch, and of course, ad buyers have always been far more susceptible to the ad industry than actual consumers. Think of John Wanamker’s famous quote, “Half my advertising spend is wasted; the trouble is, I don’t know which half.” How wild is it that Wanamaker was convinced he was only wasting half his ad spending?!

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and the evidence for the efficacy of surveillance advertising is pretty thin. When Procter and Gamble decided to stop spending $100,000,000 per year in online advertising, they saw no drop in their sales:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/10/05/florida-man/#wannamakers-ghost

Every time someone tries to get an accounting of the online ad market, they discover that it’s a cesspit of accounting fraud — Googbook lie about how many ads they show, and to whom, and how much money changes hands as a result:

https://doctorow.medium.com/big-tech-isnt-stealing-news-publishers-content-a97306884a6b

This is where criti-hype does Big Tech’s job for it. It’s genuinely weird to look at Big Tech’s compulsive lying about every aspect of its ad business and conclude that the only time these companies are telling the truth is when they assert that their products work really, really well and you should pay extra to use them.

After all, everyone who’s ever claimed to have invented a system of mind-control was either bullshitting us, or themselves, or both. From Rasputin to Mesmer, from MK Ultra to pick-up artists, the entire history of mind-control is an unbroken chain of charlatans and kooks.

https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/11/rhodium-at-2900-per-oz/#hypernormal

It’s entirely possible that Big Tech believes they have a mind control ray. Think of Facebook’s hilarious voter turnout experiment. The company nonconsensually enrolled 61m users in a psychological experiment to see if they could be manipulated into voting in a US election rather than staying home.

The experiment worked! 280,000 people whom the experimenters predicted would not vote actually voted! 280,000 people is a lot of people, right?

Well, yes and no. 280,000 votes cast in a single precinct or even a single state would have been enough to change the results of many high-salience elections over the past couple of decades (US politics are generally balanced on a knife-edge and tip one way or another based on voter turnout). But Facebook didn’t convince 280,000 stay-homers in one state to vote: they convinced 280k people out of 61m to vote. The total effect size: 0.39%.

https://www.nature.com/articles/nature.2012.11401

US elections are often close run, but they aren’t decided by 0.39% margins! The average US precinct has 1,100 voters in it. In the most optimistic projection, Facebook showed that they could get 4.29 extra voters per precinct to turn out for an election by nonconsensually exposing them to psychological stimulus.

Now, it’s possible that Facebook could improve this technique over time — but that’s not how effects in psych experiments usually work. Far more common is for the effectiveness of a novel stimulus to wear away with repetition — to “regress to the mean” as we adapt to it.

https://locusmag.com/2018/01/cory-doctorow-persuasion-adaptation-and-the-arms-race-for-your-attention/

Remember how interesting Upworthy headlines were when they arrived? Remember how quickly they turned into a punchline? Remember that the first banner ad had a 44% click-through rate!

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/04/the-first-ever-banner-ad-on-the-web/523728/

So Facebook performed a nonconsenusal psych experiment on 61m people and learned that they could improve voter turnout by 4 votes per precinct, with an intervention whose effectiveness will likely wane over time. What does that say about Facebook?

Well, on the one hand, it says that they’re a deeply unethical company that shouldn’t be trusted to run a lemonade stand, much less the social lives of 4 billion people. On the other hand, it shows that they’re not very good at this mind-control business.

That’s where Obama’s Stanford speech comes in. When Obama blames “the algorithm” for “radicalizing” people, he does Googbook’s work for them. If Mark Zuckerberg invented a mind-control ray to sell your nephew fidget-spinners, then Robert Mercer stole it and used it to make your uncle into a Qanon, then Zuck must have a really amazing advertising platform!

But like I said, Obama’s correct to observe that we’re in the midst of a conspiratorialism crisis, and Big Tech has a lot to do with it. But Obama — and other criti-hypers — have drastically misunderstood what that relationship is, and their own contribution to it.

Let’s start with the ontology of conspiracy — that is, what kind of belief is a conspiratorial belief? At its root, conspiracy is a rejection of the establishment systems for determining the truth. Rather than believing that scientists are telling us the truth about vaccine safety and efficacy, a conspiracist says that scientists and regulators are conspiring to trick us.

We live in an transcendentally technical world. You cannot possibly personally resolve all the technical questions you absolutely need to answer to be safe. To survive until tomorrow, you need to know whether the food safety standards for your dinner are up to the job. You need to know whether the building code that certified the joists holding up the roof over your head were adequate.

You need to know whether you can trust your doctor’s prescription advice. You need to know whether your kid’s teachers are good at their jobs. You need to know whether the firmware for the antilock brakes on your car is well-made. You need to know whether vaccines are safe, whether masks are safe, and when and how they’re safe. You need to know whether cryptocurrencies are a safe bet or a rampant scam.

If you get on a Southwest flight, you need to know whether Boeing’s new software for the 737 Max corrects the lethal errors from its initial, self-certified, grossly defective version (I live under the approach path for a SWA hub and some fifty 737 Maxes fly over my roof every day, so this really matters to me!).

You can’t possibly resolve all these questions. No one can. If you spent 50 years earning five PhDs in five unrelated disciplines, you might be able to answer three of these questions for yourself, leaving hundreds more unanswered.

The establishment method for resolving these questions is to hold truth-seeking exercises, which we call “regulation.” In these exercises, you have a neutral adjudicator (if they have a conflict of interest, they recuse themselves). They hear competing claims from interested parties — experts, the public, employees and executives of commercial firms. They sort through these claims, come to a conclusion and publish their reasoning. They also have a process to re-open the procedure when new evidence comes to light.

In 99% of these exercises, we can’t follow the actual cut-and-thrust of the process, but we can evaluate the process itself. Honest regulation is a black box (because most of us can’t understand the technical matters at issue), but the box itself can be understood. We can check to see whether it is sturdy, honest and well-made.

The box isn’t well made.

The regulatory process has been thoroughly captured, and is now more auction than truth-seeking exercise. Regulators themselves are drawn from the executive ranks of the companies they are regulating. How could it be otherwise? 40 years of antitrust malpractice has led to incredible concentration in nearly every industry:

https://www.openmarketsinstitute.org/learn/monopoly-by-the-numbers

When five (or four, or two) companies control an industry, the only people who truly understand that industry are the executives at those companies. What’s more, all of those executives are awfully cozy with one another, even if they’re notionally bitter competitors. An industry with just a few companies is one in which most executives have worked at most of those companies at some point in their careers. They are godparents to each other’s children; they’re executors of each others’ estates. Hell, they’re married to each other.

https://locusmag.com/2021/07/cory-doctorow-tech-monopolies-and-the-insufficient-necessity-of-interoperability/

This coziness — between competing companies, and between industries and regulators — makes regulation incredibly susceptible to capture. And since the administrative agencies (not Congress) have the most immediate and profound effect on your quality of life, this matters.

How did the Sackler family start the opioid epidemic that has killed 800,000 Americans (and counting) and walk away with billions? Their regulator slept on their transparently bullshit claims that their blockbuster drug Oxycontin was effective and non-addictive.

When someone tells you they won’t trust vaccines because Big Pharma is full of profit-maddened murderers who don’t care who they kill to make a buck, and their regulators are in on the scam — they’re not wrong.

From aerospace to pharma, agriculture to transportation, labor to the environment, privacy to broadband, the administrative branch has failed us again and again — and every time, the process itself is grossly, obviously rigged.

In Anna Merlan’s excellent Republic of Lies, she illuminates the relationship of trauma to conspiratorialism. When you are injured — especially by a corrupt process — you are no longer able to trust the process. But you still need some way of resolving complex questions you yourself aren’t qualified to answer:

https://memex.craphound.com/2019/09/21/republic-of-lies-the-rise-of-conspiratorial-thinking-and-the-actual-conspiracies-that-fuel-it/

This produces a condition of epistemological chaos: you no longer trust the process, but you don’t have anything to fill it. Into this void rushes conspiratorialism, communities of people who attempt to answer the brutal logic of “caveat emptor” by “doing the research” themselves.

Obama presided over eight years of extremely consequential regulatory failings, starting with his decision to continue bailing out the banks instead of borrowers. That led to the foreclosure crisis, financial consolidation and the finance sector’s bid to corner the market on housing.

Obama’s FDA failed to stem the opioid crisis. Obama’s DoJ and FTC permitted waves of mergers and acquisitions, from Facebook/Instagram to Dow/Dupont to United/Raytheon to Heinz/Kraft.

Big Tech’s mergers and misdeeds during the Obama years were especially grave, and Obama himself was extremely deferential to Big Tech’s claims to be benign, efficient, and (especially) brilliant. When Obama accuses Big Tech of fueling conspiratorialism through algorithmic radicalization, he’s merely restating his belief in their genius.

But they’re not geniuses. As I explained in my 2020 book, “How to Destroy Surveillance Capitalism,” the role that surveillance plays in conspiratorialism is in finding people, not convincing people.

https://onezero.medium.com/how-to-destroy-surveillance-capitalism-8135e6744d59

That is the actual mechanic of Googbook’s advertising efficacy: by spying on us all the time, Big Tech is able to target ads. So if you want to sell cheerleading uniforms, Big Tech can show your ads to cheerleaders. That is a big change in advertising, but it’s not mind control.

The internet is a system that allows people to find each other — for better and for worse. If you hold a socially disfavored view (“gender is a spectrum,” “Black lives matter”), tech will help you locate others who share that view, without requiring you to go public with it and risk social sanction. Unfortunately, this also lets people who hold odious views (“Jews will not replace us”) do the same thing.

What’s more, the ad-tech parts of the system help grifters locate and target vulnerable people. If you want to sell anti-vax (which has its own line of products, from fake vaccine cards to quack remedies), ad-tech will put your message in front of people who participate in conspiratorial communities.

And yes, Big Tech makes people vulnerable to conspiratorial thinking — but not by bypassing their cognitive faculties to put outlandish ideas in their heads. Rather, Big Tech — like all monopolies — creates the conditions for epistemological chaos, by demonstrating, day after day, that our regulatory process is an auction, not a truth-seeking exercise. Every day that goes by without the US having a federal privacy law with a private right of action is a day that wins converts for conspiratorialism.

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2022/04/stop-forced-arbitration-data-privacy-legislation

Upton Sinclair said that “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.” Obama would prefer to believe that Big Tech has a mind control ray because the alternative is recognizing that deference to corporate power has plunged the world into political chaos.

This is where the centrist/liberal world overlaps with the far right. Recall that when England erupted with a racial uprising in 2011, Prime Minister David Cameron — a far right ideologue — insisted that the whole thing was down to “criminality, plain and simple.”

https://pluralistic.net/2021/07/05/ideomotor-response/#qonspiracy

This is effectively mysticism. “Criminality” in this view, is some kind of defect that naturally occurs. It has no causal relationship to the outside world. It can’t be measured (though maybe if it could, we could precrime all the people who have it and put them in jail?). As a political philosophy, the idea that problems arise from “criminality, pure and simple” is about as useful as blaming problems on demonic possession.

Likewise Obama’s thesis, that Qanons are the result of Big Tech mind-control, and not material circumstances. It poses Big Tech’s leaders not as mediocre, sociopathic monopolists, but as evil sorcerers who must be tamed. It forecloses on weakening the companies by denying them their illegitimate market power, and it deflects any inquiry into why people are vulnerable to conspiratorialism.

All of this is to Big Tech’s advantage. If you’re Google, Obama’s condemnation of your powers of mind control is something you can add to your sales literature: “We have a data-advantage that makes our ads unstoppable — even Obama says so!”

https://pluralistic.net/2021/04/11/halflife/#minatory-legend

Image: Shira Inbar https://shira-inbar.com/

Onezero https://onezero.medium.com/how-to-destroy-surveillance-capitalism-8135e6744d59

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Police Get When They Get Your Phone

It’s not surprising that the debate over digital rights is dominated by technologists — after all, spotting risks (and promises) of technology requires a technical understanding.

Likewise, it’s not surprising that technologists are accused of solutionism — they’ve got a hammer, and they’re gonna look for nails. The problem with this critique is that not every tech intervention is solutionism.

I mean, sure, social problems are caused by social relations, but tech can change social relations. Anyone who doubts it needs to study the Industrial Revolution, the printing press, the telephone… Solutionism is the idea that tech solves everything, but the inverse — that tech solves nothing — is just nihilism.

Solutionism isn’t the only incomplete theory of social change. How many times have you heard someone say that if you don’t like how a tech company acts, you should just boycott it, “voting with your wallet?”

That’s consumerism, and it, too, can’t solve a lot of problems. You can’t shop your way out of monopoly capitalism. You can’t opt out of Googbook when every app and page you visit has an ad-tech tracker on it.

But boycotts do work…sometimes. History is replete with moments when applying commercial leverage changed corporate behavior — or weakened corporate power to the point where it could be tamed regulation.

So what about regulation? I’ve got lot of first-hand experience being patronized by Hill Rats about how all the levers of power are in the legislature and the courtroom. There’s a name for this sin: it’s called proceduralism — the belief that the most important games are won by the last person to get bored and walk away.

But only a fool would say that laws and their enforcement don’t matter. The problem with the laws against wage-theft, pollution and discrimination is that they’re not enforced, not that they exist in the first place. Our society wouldn’t be improved by getting rid of those laws.

What about direct action, though? You can go on strike, chain yourself to a pipeline, call out your boss on social media. Sure, there’s lots of time that’s failed — but the whole history of the labor movement, from coal-strikes to #MeToo, tells us that “social justice warriors” get shit done…sometimes.

You’ve probably figured it out by now. The problem isn’t proceduralism, or consumerism, or solutionism, or social movements. The problem is in the insistence that only one of those tactics should be used — when really, they are all intensely complementary. Social media gives us a tool for reaching wide audiences, even for unpopular messages. Calling out your boss on social media for being a rapey asshole is a path to insisting on better anti-harassment laws and more enforcement of the laws we have. Boycotts and threats of boycotts can keep companies from seeking to block that legal enforcement.

The problem isn’t using hammers to drive nails. The problem is in insisting that only hammers should ever be used, irrespective of whether there’s a nail involved.

This is great news, actually. Because some of us are better at community organizing, and some of us have law degrees, and some of us are hackers, and some of us really care about where our dollars go. That just means that we have room for everyone in the fight.

A corollary: though organizations are often born to fight on just one of these fronts, over time, it’s likely that it will expand to work on multiple fronts. For example, EFF really began as a campaigning law firm (an “impact litigator”) with cases like Bernstein, which killed the NSA’s ban on civilian access to cryptography.

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2015/04/remembering-case-established-code-speech

But over time, as EFF ran up against limits on who it could sue or defend, its other arms — activism, community organizing, and tech projects — grew.

We shipped code, like Privacy Badger, the leading tracker-blocker:

https://privacybadger.org/

We organized worldwide activism campaigns, like the one that saved the .ORG registry from being sold to private equity robber-barons:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/12/how-we-saved-org-2020-review

And we created the Electronic Frontier Alliance, a network of independent, grassroots community groups:

https://www.eff.org/fight

This is a kind of “full-stack activism,” with a diversity of tactics. It gets stuff done.

EFF has just launched the new season of its podcast, How to Fix the Internet. As the show name suggests, the point isn’t just to moan about looming dystopia, it’s about making things better.

Take the debut episode, in which Harlan Yu of Upturn talks with EFF exec director Cindy Cohn and EFF special advisor Danny O’Brien about how they’ve successfully fought cop-tech:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/11/podcast-episode-what-police-get-when-they-get-your-phone

Cop-tech is a fungus, experiencing wild growth in the dark. Any small-town cop, it seems, can get access to milspec spying devices that follow you around and suck your phone dry during pretextual stops. These tools are generally acquired without disclosure or debate, and while their use is nominally regulated by cases like Riley v California, cops have figured out how to dodge those restrictions. It’s a free-for-all.

But it doesn’t have to be. As Yu describes, there are leverage-points in the regulation of cop-tech, places where small changes to the law and its application can bring oversight and accountability to high-tech policing.

This is the kind of podcast I love — I learned a lot about cop-tech that I didn’t know, much of it scary and disheartening. But I also learned what we can do about it — what the path of least resistance is to preventing this kind of dystopian hellscape.

That’s the best kind of technopolitics: one that draws on an understanding of social forces, markets, the law and technology to both analyze problems — and do something about them.

Here’s a direct link to the MP3:

https://archive.org/download/h2fti-ep1-harlan-yu-mix-vfinal/h2fti-ep1-harlan-yu-mix-vfinal.mp3

And here’s the RSS for the rest of this coming season of How to Fix the Internet:

https://feeds.eff.org/howtofixtheinternet

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monopoly power and political corruption

As antitrust awakens from its 40-year, Reagan-induced coma, there’s both surging hope that we will tame corporate power, and a backlash that says that antitrust is the wrong framework for reducing the might of giant corporations.

Competition itself won’t solve problems like digital surveillance, pollution or labor exploitation. If we fetishize competition for its own sake, we could end up with a competition to see who can violate our human rights most efficiently.

https://pluralistic.net/2021/08/24/illegitimate-greatness/#peanut-butter-in-my-antitrust

Even if we do care about competition, a lack of antitrust enforcement isn’t the sole cause of concentration: patent abuse, DRM lock-in, criminalizing terms of service violation and other anticompetitive tactics suppress rival market entrants, but don’t violate antitrust.

But I’m here to say that a lack of antitrust enforcement is the way to understand the source of harms like environmental degradation and labor exploitation, and anticompetitive tactics like copyright abuse.

To explain why, I’ve published a new editorial for EFF’s Deeplinks, called “Starve the Beast: Monopoly Power and Political Corruption.”

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/08/starve-beast-monopoly-power-and-political-corruption

Here’s my core thesis: monopolized industries have high profits, which they can spend to legalize abusive conduct.

And!

Monopolized industries also have a small number of dominant companies, which makes it easier to agree on a lobbying agenda.

In other words, when an industry is reduced to just a handful of companies, they have more ammo and it’s a lot easier for them to agree on their targets — deregulation, expansions of proprietary rights, and regulatory capture.

Which is why monopoly begets monopoly! Remember the Napster era, when tech had almost no lobbying muscle and got its ass routinely handed to it by the much smaller entertainment cartel, who were represented by a handful of wildly profitable companies with lobbying armies?

Tech was disorganized and dynamic, with today’s giants becoming tomorrow’s also-rans, more concerned with fighting each other than inter-industry rivalries.

Today, with the web reduced to five giant sites filled with screenshots from the other four, it’s easy for tech leaders to agree on a common agenda, and they have So. Much. Money. to spend on lobbying to make it reality.

https://corporateeurope.org/en/2021/08/lobby-network-big-techs-web-influence-eu

Think of the absolute tsunami of fuckery the telco industry unleashed to kill net neutrality, from sending 1m anti-net neutrality comments that purported to come from Pornhub employees (!) to having those comments counted by the world’s most captured regulator, Ajit Pai.

That was an expensive war, and the way Big ISP was able to afford it was because it uses regional monopolies to screw customers and workers and amass a vast warchest of lobbying dollars — and because the industry is composed of so few companies that they all can all agree.

If we want to smash corporate power and free our lawmakers and regulators to do the people’s business, without the corrupting influence of a flood of corporate money, we have to starve the beast. Corporations deprived of monopoly profits can’t afford to lobby.

What’s more, if we demonopolize our industries — smashing the oligopolies of 1–5 companies that dominate ever sector — so that each industry is a squabbling rabble of hundreds of companies, they won’t be able to agree on how to fuck us over anymore.

Critics of Big Tech antitrust are right that it’s not enough to attack Big Tech. If we demonopolize tech without smashing the rest of its supply chain — ISPs and entertainment — then those monopolists will divide Big Tech’s share among themselves.

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/09/bust-em-all-lets-de-monopolize-tech-telecoms-and-entertainment

But that’s not a reason to leave Big Tech alone. That’s a reason to expand the antitrust agenda to every industry, to treat the fight against tech monopolies as the start, not the goal, as a way to create momentum for smashing monopolies in every sector.

We can’t afford another mistake like the one that led to the passage of 2019’s EU Copyright Directive, with its Article 17, a rule set to destroy every small EU tech platform and replace them with a Googbook-dominated filternet with our lives at the mercy of copyright bots.

During that fight, advocates for creative workers made the mistake of assuming that by advocating for entertainment monopolies against tech monopolies, they’d improve their own lives.

That’s not how it works.

The only way to improve labor’s side of the bargain is to make capital weaker. Allowing Big Tech to consolidate its position by exterminating all EU competitors in exchange for sending a few billion to Big Content will not make creative workers any richer.

Rather, it makes both industries’ monopolies stronger, and further weakens creative workers’ leverage over corporate entertainment behemoths, guaranteeing that virtually all the windfall profits from the Directive will go to shareholders, not workers.

The world deserves better than being allowed to choose which giant, abusive corporations we support in inter-industry battles — none of the giants give a shit about us, except as human shields for their own battles.

For workers, users, learners and others to come out ahead, we don’t need to pick the right source of corporate power to ally ourselves with. We need to shrink corporate power — all corporate power — until it fits in a bathtub.

And then drown it.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

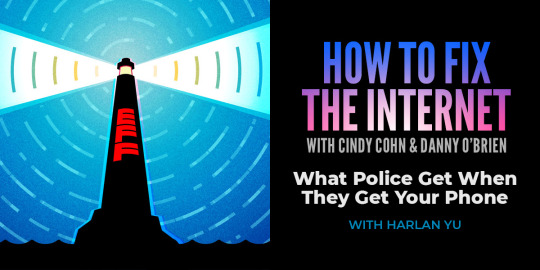

Consumerism won't defeat Georgia's Jim Crow

In the 1970s, progressives discovered a shortcut to political change: the boycott. Boycotts had been around for a long time, to be sure, but with industries in relatively weak states, with lots of competitors, the threat of lost business could spur fast action.

Politics were slow and unreliable. Lawsuits were expensive, slow and unreliable. Boycotts were fast, and involved direct, tangible steps that every person could take: redirect your spending from one company to another, make the change.

But as progressive movements ceded the political realm, reactionaries conquered it. Reagan and his successors (including pro-business Dems) enacted laws and policies that encouraged monopolies and weakened labor unions.

40 years later, boycotts are dead.

Hate excessive packaging?

Good news: the grocery aisle has minimal packaging alternatives you can vote your dollars on.

Bad news: these "alternatives" come from the same companies as the high-packaging products you're "voting against."

Boycotts only work when there's competition. As this Simpsons screenshot demonstrates - Duff Lite, Duff Dry and Duff all come from the same pipe.

Likewise: Fox Studios, who made the Simpsons, are now part of Disney.

Don't like Fox? Vote with your dollars on Disney!

Right-wing politics have a problem. If your fundamental belief is that a small number of people should have more (money, power, influence) than everyone else, then by definition, your politics only benefit a minority, and you win elections with majorities.

The right has three tactics to overcome this.

I. It relies on antimajoritarian institutions, like the Electoral College and the Senate. That's why the Dems should *absolutely* kill the filibuster, which protects Senate power, which is minority power, which is plute power.

II. It suppresses the votes and power of working people, through gerrymandering, poll taxes, voter-roll purges and anti-union rules that shatter the collective power of otherwise atomized and powerless workers.

III. It convinces turkeys to vote for Christmas. Performative culture-war bullshit, white nationalism, transphobic panics, etc - none of these are intrinsic to the right-wing project, but they bring a lot of scared bigots out to vote for dead-eyed corporate rule.

The new Jim Crow law just adopted in Georgia is a perfect example of how these three tactics deliver power to corporate power. It's a voter suppression law, passed by a gerrymandered statehouse that represents a minority of Georgians, which exploits white nationalism.

Remember, the reason corporate America is worried about Georgia is the Black, working-class-led political machine that threatens to enact majority rule in a place whose state and national leaders are essential to inequality-boosting, plute-enriching, worker-destroying rule.

The reason all these red states introduced nearly identical voter-suppression bills is that they all get their laws from the same place: ALEC, a business-backed thinktank that writes and pushes "model legislation" in state- and local governments.

https://www.salon.com/2021/03/27/conservative-groups-are-writing-gop-voter-suppression-bills---and-spending-millions-to-pass-them/

ALEC finds its wins in GOP legislatures, but it gets its funding from a broad cross-section of corporate America, including companies that publicly brief for racial and gender justice.

https://www.commoncause.org/democracy-wire/who-still-funds-alec/

Now, ALEC has faced something of an exodus, losing members like AT&T and Google, but that doesn't mean that they've divested from ALEC policies.

The politicians who carry water for ALEC are 100% dependent on campaign contributions from orgs like the Chamber of Commerce.

These politicians brief for policies that hurt the majority of Americans, and can only get elected through voter suppression, gerrymandering and appeals to bigotry. There's no other way to win electoral majorities while espousing antimajoritarian policies.

This doesn't mean that corporate execs and employees aren't horrified by Georgia's New Jim Crow law - it just means that they can't do anything about it. Companies that halt donations to the GA GOP will *still* financially support them, through their industry associations.

It's a perfect macrocosm of the consumer's dilemma: if you rely on money, rather than politics, to accomplish political change, you will never make a change that reduces the power of money in politics. It's impossible to spend your way out of monopoly capitalism.

At best, it's merely useless. At worst, it's a net negative, sucking up the hours you could spend on political change with comparison shopping. As Zephyr Teachout points out in BREAK 'EM UP, what you do matters more than what you spend.

https://pluralistic.net/2020/07/29/break-em-up/#break-em-up

If you're organizing to support union drives, don't waste time shopping to "buy local" for posterboard and markers - they're all manufactured by anti-union monopolists, no matter who sells them. Get whatever's easiest and then go fight the companies in the *political* realm.

Stop conceiving of yourself as an ambulatory wallet, whose only power comes from where and how you spend - if you only vote your dollars, you'll always lose, because the rich have more dollars than you and so they get more votes.

Keep your eyes on the prize: smashing corporate power. Far more exciting than the MLB boycott of Georgia is the Republican response: GOP hardliners want to take away baseball's antitrust exemption.

https://twitter.com/matthewstoller/status/1378103553437360131

If this happens, it will be the absolute best possible outcome - because it represents the shattering of the coalition that makes antimajoritarian politics possible. If the right starts siding with bigots and AGAINST companies, they'll cut their own supply lines.

The voter suppression, gerrymandering and bigotry that the GOP relies on is expensive. It can't exist without corporate power. The reason it exists in the first place is corporate power.

Reinvigorating antitrust as an act of performative culture-war bullshit is the political equivalent of pointing a gun at your own dick to own the libs and then blowing your actual dick off.

https://pluralistic.net/2020/05/27/literal-gunhumping/#youll-shoot-your-eye-out

These are the fracture lines we need to exploit. They've been proliferating for years. The modern antitrust revival comes out of these fracture lines.

It's an open secret that much of the money and energy for anti-Big Tech trustbusting comes from the cable industry.

Comcast and AT&T hate Google and Facebook, but not for the same reason you or I do. In their view, the billions Googbook make from surveillance, rent-extraction and manipulation have been misapproriated from the telecoms industry.

They have made the catastrophic blunder of betting that if they awaken the slumbering antitrust giant to smash Big Tech, that it will then go back to sleep - and that it *certainly won't turn on *them*.

This is such galaxy-brain idiocy. Like the public will watch a new army of trustbusters arise to rip apart Googbook and then say, "You know what? I just *fucking love Comcast*, so whatever you do, don't give them the same treatment."

A bet that after the dust settles, the hard-fighting lawyers, activists, politicans and workers who smashed corporate power in Big Tech will realize that they were only worried about "surveillance capitalism" but were totally cool with all the other kinds of capitalism.

Consumer power is a dead letter. Political power is a live wire. Boycotts are a distraction, even - especially - when giant corporations engage in them.

But the other stuff - strikes, trustbusting, ending financial secrecy - that's where change comes from.

The problem with the world isn't where you shop.

You're not an ambulatory wallet and don't let anyone convince you that you are.

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

Google's short-lived data-advantage

There's a lot of ways to think about the movement to tame Big Tech, but one of the more useful divisions to explore is the "Night of the Comet" people versus the "Don't Believe the Criti-Hype" people.

This is a division over the value of the data that Google, Facebook and other large tech firms have amassed over the years - data on their users, sure, but also data on the advertisers and publishers they serve with their ad-tech platforms.

Big Tech companies and their investors are really bullish on the value of this commercial data-advantage: they say that spying on us - the users - lets them manipulate our opinions and activities so that we buy or believe the things their advertisers pay them to push.

More quietly, their investors believe that the data-advantage extends to publishers and advertisers, a deep storehouse of data that makes it effectively impossible for anyone else to do the precision targeted that Big Tech manages, which is why they have such fat margins.

Night of the Comet tech criticism accepts these claims at face value: Big Tech's advantage, they claim, comes from having amassed this insurmountable data-advantage that allows it to both predict and shape what we - and therefore advertisers and publishers - will do.

The implication of this is that traditional antitrust remedies - breakups, say - won't be merely ineffective; they'll be terrifyingly harmful.

If Googbook invented a mind-control ray to sell your nephew fidget-spinners, then breaking them up will only make it easier for Robert Mercer to hijack that mind-control ray to turn your uncle into a Qanon racist.

Googbook's data-advantage, in other words, is like a planet-killing comet heading towards the Earth. If we break that comet up, it will turn into a killing rain of meteors that shower onto every part of the globe - we can't break up the comet, we have to *steer* it.

In this version of tech criticism, the answer is to leave Big Tech intact, but turn it into a utility, or some other highly regulated entity, bound by rules that limit its use of that mind-control system.

Bringing Big Tech to heel by deputizing it to serve as an arm of the state (and perhaps a national champion in the new Cold War with China), like the Bell System prior to the AT&T breakup in '82.

On the other side, you have the Don't Believe the Criti-Hype school. Lee Vinsel coined the term "Criti-Hype" to describe a kind of criticism that actually hypes its subject - say, by repeating Big Tech's self-serving claims.

https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/02/euthanize-rentiers/#dont-believe-the-hype

These claims aren't just self-serving, they're also highly dubious. Everyone who's ever claimed to be able to read - or control - our minds was lying (to themselves, or to everyone else, or both).

The "psychometrics" that all this behavior-modification depends on is - to quote *Nature* - a "scant science." From Big Five Personality Types to microexpression/sentiment analysis, we're deep into the realm of irreproducible results and junk science.

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-03880-4

The Criti-Hype school posits that the supernormal returns to capital for Big Tech aren't driven by awesome ad-tech capabilities, but rather, by monopoly (buying or crushing all competitors) and the fraud it enables (the industry has nowhere else to go).

That is, Big Tech makes money the same way hedge-fund managers make their own stunning returns: by cheating so they get paid whether or not they're any good at their jobs. The mere existence of a profitable industry is not proof that the industry is run by competent people.

And to be clear, there is a *lot* of fraud in ad-tech. Tim Hwang calls it a "Subprime Attention Crisis," where the ads are fake, the clicks are fake, the publishers' inventory is fake, the whole thing *riddled* with fraud.

https://pluralistic.net/2020/10/05/florida-man/#wannamakers-ghost

As Aram Zucker-Scharff wrote, "The numbers are fake, the metrics are bullshit, the agencies responsible for enforcing good practices are knowing bullshitters profiting off the fake numbers and none of the models make sense at scale of actual human users."

https://pluralistic.net/2021/01/04/how-to-truth/#adfraud

It's a "bezzle" - a con whose mark hasn't twigged to the ruse...yet.

And while the Night of the Comet side relies on the irreproducible claims of self-proclaimed Svengalis, the Criti-Hype side has an increasingly corpus of cold, hard facts about the bezzle's operation.

Take last November's "Why Google Dominates Advertising Markets," Dina Srinivasan's superb and detailed dissection of Google's crooked ad-markets, in which they steal from advertisers and publishers by rigging the bids on both sides of the exchange.

https://pluralistic.net/2020/11/20/sovkitsch/#adtech

Srinivasan proves you don't need mind-control rays to explain how Big G makes fantastic returns from the ad-tech market. That prospect is further explored in the UK Competition and Markets Authority's 437-page report on "Online platforms and digital advertising" (Jul '20):

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5fa557668fa8f5788db46efc/Final_report_Digital_ALT_TEXT.pdf

Here's where it starts to get *really* interesting. In May 2020, Yale's Fiona Scott Morton and Omidyar's David Dinielli used preliminary CMA data to publish their "Roadmap for a Digital Advertising Monopolization Case Against Google."

https://omidyar.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Roadmap-for-a-Case-Against-Google.pdf

Morton and Dinelli zero in on the actual mechanism of Google's data-advantage, the thing it commands a lion's share of, which advertisers genuinely prize: location data. If I know you're around the corner from my cafe, I might spend a *lot* to show you an ad for my pasties.

This location data advantage is undeniable, but man, it has a short half-life. Thing is, I might spend a lot of money to show you an ad for my coffee shop when you're around the corner, but once you've moved on, you can go to hell as far as I'm concerned. You're dead to me.

This short half-life tells us that we're not living the Night of the Comet nightmare scenario. Break up Google, starve it of location data, and within *hours* most of its location targeting advantage is gone...forever.

As the antitrust cases against Google proceed, more and more of these technical exposes of rigged markets emerge, showing us how monopoly and fraud are at the heart of the data-advantage, and how contingent, time-bound and fragile that advantage really is.

The latest is the bizarrely named "Project Bernanke," a formerly secret ripoff that was exposed when Google forgot to redact a document it filed in its Texas antitrust case:

https://twitter.com/KhushitaVasant/status/1379955848118726659

Google used data from recent ad-auctions to help advertisers shade their bids for ad-placements, exploiting the information asymmetry so the ads it brokered won the auctions, ensuring that rivals ad-brokerages were frozen out.

https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/googles-secretive-project-bernanke-reportedly-093732134.html

Though Google insists that this was just an industry practice, the leaked document reveals that Google kept this a secret from publishers. Its internal presentations claim that they made $230m in 2013 alone from this practice.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/googles-secret-project-bernanke-revealed-in-texas-antitrust-case-11618097760

All together, this constitutes a highly specific account of how a data-advantage worked - and what its weak-point is. Project Bernanke was not grounded in longitudinal market data from ad-sales - it exploited *recent* data to deliver a $230m+/year advantage.

The multisided market - a multisided bezzle - exploits the monopolist's data advantage to harm readers, publishers and advertisers, not by predicting and shaping their behavior by bypassing their critical faculties with spooky, advanced psychometrics.

The bezzle requires fresh data - it's a flywheel that uses the monopolist's god's-eye-view to freeze out competitors and entrap publishers and advertisers to get more data to rig the market to entrap the publishers and the advertisers.

It's not a comet. It's a monopoly. It's not terrifying supergeniuses using machine learning to turn us into clicking zombies: it's garden-variety monopolists using anticompetitive, underhanded, dishonest and (probably) illegal tactics to maintain their monopoly.

Bust the trust, ban the conduct, and the data-advantage evaporates with the half-life of that extremely time-bound data. The criti-hype that says that the data-advantage is a deadly, unstoppable comet is just Google's own sales-patter, flipped on its head.

Don't believe the criti-hype.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Help news, not news-barons

More often than not, when I encounter a proposal to address monopoly power, I return to that old Irish joke: "If you wanted to get there, I wouldn't start from here."

Today, it's the proposal to save American news media by granting an exception to antitrust law so the news companies can form a cartel to bargain with the ad-tech duopoly represented by Googbook.

Let's start with the sleaziness of Googbook's ads. The ad-tech markets are rigged from asshole to appetite. Googbook defrauds buyers and sellers, collude to rig prices, and trouser billions for their trouble. It's not just sleazy, it's criminal.

https://pluralistic.net/2020/11/20/sovkitsch/#adtech

Publishers are victimized by this fraud. The ad-tech duopoly uses funny accounting to shift billions from publishers of all kind to their own balance sheets (advertisers also suffer, but we're talking publishers at the moment).

The news industry deserves our sympathy for this, but they keep squandering it by saying stupid things like "Google steals from us by linking to our websites." These stupid things are credulously repeated by both the left- and right-wing press.

https://prospect.org/blogs/tap/will-google-stop-stealing-content-from-the-media/

Google and Facebook don't steal from publishers by sending them traffic. They don't steal from them by including short snippets from their articles. Neither of those things are stealing.

Googbook steals from publishers through ad-fraud and price-rigging.

It is frankly baffling to me that the news media has decided to ignore the vast, multi-billion-dollar fraud that is ad-tech in favor of the nonsensical proposition that directing readers to your articles and engaging in fair use quotation are crimes.

Writing for EFF's Deeplinks blog, my colleagues Katharine Trendacosta and Danny O'Brien describe the flaws in the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act, which proposes antitrust exemptions to news organizations to help them push back against Googbook.

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/03/antitrust-exemption-news-media-wont-take-us-back-time-big-tech

To understand why this proposal is before the Congress, you have to understand that the dominant school of antitrust enforcement in the west is the "consumer harm" standard, popularized by Robert Bork when he was serving as Ronald Reagan's court sorcerer.

Bork was the Qanon of antitrust. He insisted that if you read the US's four founding antitrust statutes closely enough, you'd learn that despite the *explicit* language saying monopolies were bad because *they are monopolies*, Congress only intended to shut down *bad* monopolies.

What's a bad monopoly? A monopoly that raises prices. If you can't prove that a merger will lead to higher prices, it should be permitted. If you can't prove that higher prices after the merger were caused by monopoly, they should be forgiven.

Of course, Bork determined whether high prices could be attributed to a monopoly through complex economic models that only he and his friends at the University of Chicago economics department could create and interpret, and the models always said monopolies were fine.

Thus monopolies began to form in every industry, taking over one part of the supply chain or another. Once that happened, that element of the supply chain started to gouge everyone else. Every other part of the supply chain had to monopolize in self-defense.