#george bannerworth

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

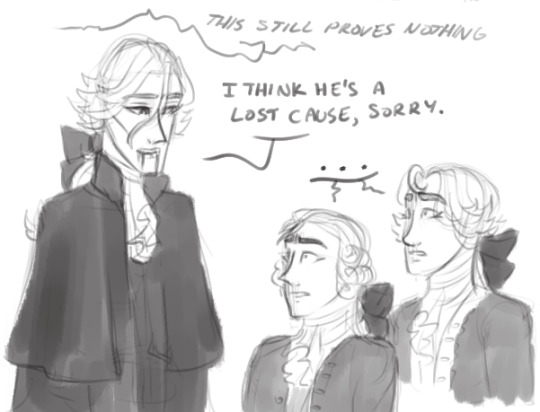

someone save flora

#varney the vampire#art#memes#george bannerworth#marchdale#flora bannerworth#edit: somehow managed to forget george's fuckin freckles fml

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

your character design for George Bannerworth is impeccable

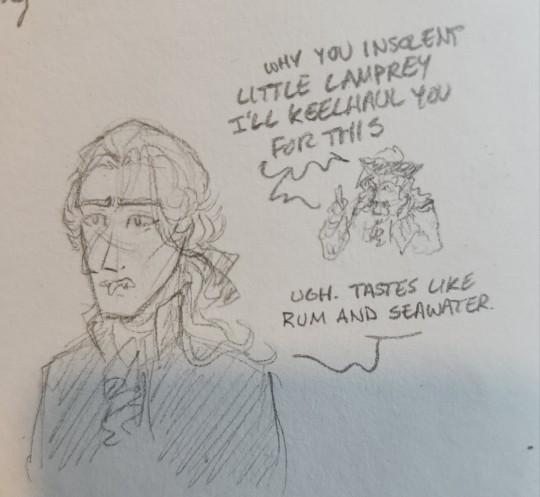

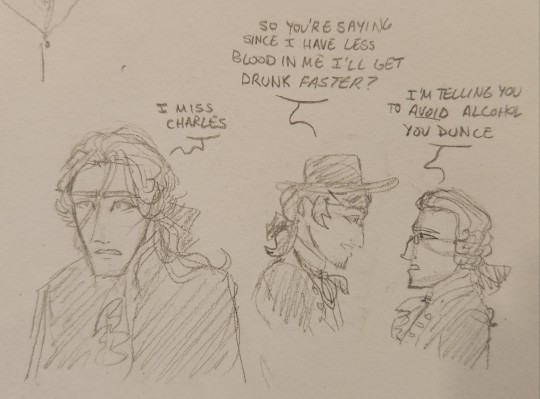

VARNEY POSTING PART 5: in which i finally make varney bite some characters who are not charles

in order: dr. chillingworth, henry bannerworth, marchdale, admiral bell, jack pringle, mortimer/montgomery, josiah crinkles (averted by surprise time-traveling jonathan harker appearance), jack seward (hitched a ride with jonathan), george bannerworth (averted bc it's unclear if chibi-style george even has a neck)

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Varney the Vampire: Chapter 15

Chapter 14: So anyway, when do we kill him

I need to start this off with a full Previously On, and you’ll see why in a minute:

Fair damsel Flora Bannerworth was attacked one night by a befanged, leaden-eyed vampyre. Her mother mostly faints about it; it’s her two brothers, Henry and George, who have been trying to protect her and figure out what the fuck is going on. Their allies are their housemate/kinda-uncle, Mr. Marchdale, who was once their mother’s sweetheart before she chose the brothers’ shitheel father (RIP) instead; Flora’s recently returned fiancé, the virtuous young artist Charles Holland; and a Mr. Dr. Chillingworth, who thinks vampyres are bullshit. Amid several incidents where various Bannerworths shoot the vampyre, Henry realizes that the ancestor in a spooky portrait in Flora’s bedroom is one and the same. But also, a mysterious new neighbor keeps offering to buy the family estate. In the last two chapters, Henry and Marchdale paid a visit to this Sir Francis Varney, only to realize that HE is the vampyre/ancestor. Henry said to his face, “HOLY SHIT, YOU��RE THE VAMPYRE.” And the vampyre said, “Nah.”

None of these characters and none of these settings are in this chapter. Instead, two entirely new characters are introduced (for 4800 words). You are either going to love this, or you are going to hate this.

Chapter XV.

THE OLD ADMIRAL AND HIS SERVANT. -- THE COMMUNICATION FROM THE LANDLORD OF THE NELSON'S ARMS.

We've already been told that the servants (both the ones who immediately quit after the vampyring, and the replacements who reluctantly agreed to start working at Bannerworth Hall) have run out and told everybody in the neighborhood everything; Henry's already had total randos ask him about The Horrors. We're told now that:

The servants, who had left the Hall on no other account, as they declare, but sheer fright at the awful visits of the vampyre, spread the news far and wide, so that in the adjoining villages and market-towns the vampyre of Bannerworth Hall became quite a staple article of conversation. [...] Everywhere then, in every house, public as well as private, something was being continually said of the vampyre. [...] But nowhere was gossiping carried on upon the subject with more systematic fervour than at an inn called the Nelson's Arms, which was in the high street of the nearest market town to the Hall. There, it seemed as if the lovers of the horrible made a point of holding their head quarters, and so thirsty did the numerous discussions make the guests, that the landlord was heard to declare that he, from his heart, really considered a vampyre as very nearly equal to a contested election.

Ahhh, contested elections. Sad lol. But now, we're told, on the very evening of the day that Henry accused Varney of being a vampyre, and Varney just shrugged, two new characters that we don't know shit about have arrived:

One of these people was a man who seemed fast verging upon seventy years of age, although, from his still ruddy and embrowned complexion and stentorian voice, it was quite evident he intended yet to keep time at arm's-length for many years to come. He was attired in ample and expensive clothing, but every article had a naval animus about it, if we may be allowed such an expression with regard to clothing. On his buttons was an anchor, and the general assortment and colour of the clothing as nearly assimilated as possible to the undress naval uniform of an officer of high rank some fifty or sixty years ago. His companion was a younger man, and about his appearance there was no secret at all. He was a genuine sailor, and he wore the shore costume of one. He was hearty-looking, and well dressed, and evidently well fed.

James Malcolm Rymer's favorite humor format is Characters Who Don't Talk Classy Lmao:

"Heave to!" [the younger man] then shouted to the postillion, who was about to drive the chaise into the yard. "Heave to, you lubberly son of a gun! we don't want to go into the dock." "Ah!" said the old man, "let's get out, Jack. This is the port; and, do you hear, and be cursed to you, let's have no swearing, d -- n you, nor bad language, you lazy swab."

Lol. Rofl, even.

The Younger Man is Jack Pringle, and he helpfully informs The Old Man, one Admiral Bell, that he has been his [the Admiral's] walley de sham on dry land for ten years. The Dictionaries of the Scots Language (before and after 1700) inform us that this term is derived from the French valet de chambre, a personal servant. (The search also turned up some British and Irish usage, and Jack does not otherwise sound Scottish, or even "Scottish.") Interestingly, when I googled this phrase, the image search tab pulled up nothing but Varney the Vampire illustrations. None of them had Jack or the Admiral.

I'm belaboring this point because about 85% of this chapter is just these two characters squabbling and it is draining my will to live.

"Be quiet, will you!" shouted the admiral, for such indeed he was. "Be quiet." [...] "Belay there," said Jack; and he gave the landlord what he considered a gentle admonition, but which consisted of such a dig in the ribs, that he made as many evolutions as the clown in a pantomime when he vociferated hot codlings.

"Hot Codlings" is a song from a Mother Goose pantomime. What evolutions are vociferating. Why are words doing this. Where are we.

Bruised and confused, the landlord of the Nelson's Arms is doing his best to be hospitable; finally, the Admiral reveals that he has been sent a letter asking him to stop at this very inn, here in Uxotter (which might be Uttoxeter), by one Josiah Crinkles:

"Who the deuce is he?"

I don't know, you're the one who just drove up! The landlord cannot seem to get anything useful out of his mouth for several lines, because James Malcolm Rymer gets paid more that way. Note: "d -- -- d" will show up several times; it's just "damned," censored, and it's the expletive these two mostly fall back on:

"I'll make you smile out of the other side of that d -- -- d great hatchway of a mouth of yours in a minute. Who is Crinkles?" [The landlord:] "Oh, Mr. Crinkles, sir, everybody knows. A most respectable attorney, sir, indeed, a highly respectable man, sir." [Several lines of banter] "To come a hundred and seventy miles to see a d -- -- d swab of a rascally lawyer!"

But then, Jack Pringle says something interesting:

"Well, but where's Master Charles? Lawyers, in course, sir, is all blessed rogues; but howsomedever, he may have for once in his life this here one of 'em have told us of the right channel, and if so be as he has, don't be the Yankee to leave him among the pirates. I'm ashamed of you."

Who in this story do we know named Charles? We'll get to that several hundred words from now. Meanwhile, a bit more of the rapport between Jack Pringle and the Admiral:

"You infernal scoundrel; how dare you preach to me in such a way, you lubberly rascal?" "Cos you desarves it." "Mutiny -- mutiny -- by Jove! Jack, I'll have you put in irons -- you're a scoundrel, and no seaman." "No seaman! -- no seaman!"

The fact that this line does not end with the dialogue tag "he ejaculated" is one of literature's great tragedies.

This goes on for so long that it starts to take on a nonsensical—dadaist? that can't be right? what is happening. I don't know—quality:

"Confound you, who is doing it?" "The devil." "Who is?" "Don't, then."

Over a couple hundred words, Jack and the Admiral demand grog and a private room at the inn, and for the landlord to send for one Mr. Josiah Crinkles ("and tell him Jack Pringle is here too"). After jawing a while about how they'll serve this rascally lawyer out howsomedever, Jack says something interesting again:

"And, then, again, he may know something about Master Charles, sir, you know. Lord love him, don't you remember when he came aboard to see you once at Portsmouth?"

And right when you think we might hear who Master Charles is, they start arguing again, this time about the time they were yard arm to yard arm with those two Yankee frigates (wait they were what now? when now? the War of 1812, maybe? they can't both be old enough for the American Revolution?) and "you didn't call me a marine then," which is insulting and distinct from "seaman" in some way,

"when the scuppers were running with blood. Was I a seaman then?" "You were, Jack -- you were; and you saved my life." "I didn't." "You did."

CHRIST ALMIGHTY THEY KEEP ARGUING ABOUT THIS (bickering is how they show they care) until finally the landlord, with a flourish, ushers in one Mr. Josiah Crinkles.

A little, neatly dressed man made his appearance, and advanced rather timidly into the room. Perhaps he had heard from the landlord that the parties who had sent for him were of rather a violent sort. "So you are Crinkles, are you?" cried the admiral. "Sit down, though you are a lawyer."

There is no respect for lawyers in the Admiral's house! Ship! Room! We are now about halfway through the chapter. God give me strength. The Admiral bids Josiah Crinkles read the full supercut of the letter from Josiah Crinkles, aloud. I will reproduce it in full whether you like it or not:

"To Admiral Bell. "Admiral, -- Being, from various circumstances, aware that you take a warm and a praiseworthy interest in your nephew Charles Holland,

CHARLES HOLLAND BABY

I venture to write to you concerning a matter in which your immediate and active co-operation with others may rescue him from a condition which will prove, if allowed to continue, very much to his detriment, and ultimate unhappiness. "You are, then, hereby informed, that he, Charles Holland, has, much earlier than he ought to have done, returned to England, and that the object of his return is to contract a marriage into a family in every way objectionable, and with a girl who is highly objectionable. "You, admiral, are his nearest and almost his only relative in the world; you are the guardian of his property, and, therefore, it becomes a duty on your part to interfere to save him from the ruinous consequences of a marriage, which is sure to bring ruin and distress upon himself and all who take an interest in his welfare. "The family he wishes to marry into is named Bannerworth, and the young lady's name is Flora Bannerworth. When, however, I inform you that a vampyre is in that family, and that if he married into it, he marries a vampyre, and will have vampyres for children,

Remember what I said about family stains and tainted bloodlines?

"I trust I have said enough to warn you upon the subject, and to induce you to lose no time in repairing to the spot. "If you stop at the Nelson's Arms in Uxotter, you will hear of me. I can be sent for, when I will tell you more. "Yours, very obediently and humbly, "JOSIAH CRINKLES." P.S. I enclose you Dr. Johnson's definition of a vampyre, which is as follows: "VAMPYRE (a German blood-sucker) -- by which you perceive how many vampyres, from time immemorial, must have been well entertained at the expense of John Bull, at the court of St. James, where nothing hardly is to be met with but German blood-suckers."

I was legitimately about five minutes from hitting post with this written as "I despair of figuring out who Dr. Johnson is," when suddenly I managed to dredge SAMUEL JOHNSON WITH THE DICTIONARY!! out of my covid-riddled brain. ~Dr. Johnson didn't define "vampyre" (any spelling), so whatever Rymer's on about here, he made it up himself with a wink to the reader.

I also wasn't going to deal with the fact that vampyres are suddenly German rather than Norwegian, or Swedish, or Levantine, or Arabian. But then I realized that this might be related to that time Empress Maria Theresa sent a guy out to deal with A Vampire Problem. (The fact that I'm the kind of person who would go, "Oh, right, the Austrian vampire problem" is why I'm recapping this godforsaken serial in the first place.) And you might refer to vampires as "German" because all the areas involved, including the Austrian Empire, were in the German Confederation at the time Rymer was writing in the 1840s. Referred to as "the 18th-Century Vampire Controversy,"

The panic began with an outbreak of alleged vampire attacks in East Prussia in 1721 and in the Habsburg monarchy from 1725 to 1734, which spread to other localities. [...] The problem was exacerbated by rural epidemics of so-called vampire attacks, undoubtedly caused by the higher amount of superstition that was present in village communities, with locals digging up bodies and in some cases, staking them.

I gotta refer you here back to Chapter 14 last week, in which we discussed a Romanian incident of this nature that happened in 2003. Meanwhile, back in the 18th century, some real-true vampire history is unfolding: this panic was the subject of Dom Augustine Calmet's classic Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants of Hungary, Moravia, et al. ("Numerous readers, including both a critical Voltaire and numerous supportive demonologists interpreted the treatise as claiming that vampires existed.") The hysteria spread to Austria, where Empress Maria Theresa sent her personal physician to sort this shit out; there is a movie somewhere to be made about Gerard van Swieten, Vampire Hunter. Except for the fact that he came to the conclusion that vampires were bullshit in his report, Discourse on the Existence of Ghosts; as a result, Maria Theresa decreed that her subjects must stop digging up corpses and doing unfortunate vampire-hunter things to them. (Or is that just what they wanted us to think??) "Dr. Johnson's" definition of vampyres as German could have been referring to any/all of the Controversy, and it has more real-life historical basis than Vampyres of Norway. So I'll allow it. *gavel*

by which you perceive how many vampyres, from time immemorial, must have been well entertained at the expense of John Bull, at the court of St. James, where nothing hardly is to be met with but German blood-suckers.

Wait, what?

Is this referring to young Queen Victoria's husband, Prince Albert, being German? Is this like the mystifying snark about "German princes" earlier? Have I finally cracked this? British citizens were chortling over their penny papers at such political humor, I guess?

Meanwhile, the Admiral is bellowing; the lawyer is stammering. What we come to understand, after all my digressions about German vampyres, is:

Josiah Crinkles didn't write this letter.

And he has no idea who did. He's only heard of Admiral Bell "as one of those gallant officers who have spent a long life in nobly fighting their country's battles, and who are entitled to the admiration and the applause of every Englishman." Well, when you put it that way: Jack and the Admiral decide that Josiah Crinkles, Esq., is a fine and honorable gentleman, even if he is a lawyer! I sure hope you didn't have anywhere you meant to go today!

"No. I'm d -- -- d if you go like that," said Jack, as he sprang to the door, and put his back against it. "You shall take a glass with me in honour of the wooden walls of Old England, d -- -e ["damn me"?], if you was twenty lawyers."

Uh, slow down with the false imprisonment there. What Josiah does know is a little bit about the Bannerworth family, by which I mean everything, and we're gonna hear all about it, again, because James Malcolm Rymer got bills.

There is still another 1700 words left in this chapter, by the way.

"Shiver my timbers!" said Jack Pringle, [...] -- "Shiver my timbers, if I knows what a wamphigher is, unless he's some distant relation to Davy Jones!"

Jack Pringle's interpretations of the word "vampyre" is maybe my favorite thing about the entire serial.

Jack and the Admiral bickering for another 300 words is maybe my least favorite thing about the entire serial. WOULDN'T YOU LIKE TO HEAR ABOUT THE VAMPYRE? "It appears that one night Miss Flora Bannerworth, a young lady of great beauty, and respected and admired by all who—Jack and the Admiral are still bickering. Nobly, Josiah Crinkles continues to recap chapters 1 and 2 for us (in fairness, this may have actually been helpful to penny dreadful readers in 1845). But what of the Admiral's nephew? Josiah knows nothing, much less what was written in the letter. You'd think it was Varney being nefarious, except that I don't know how he would know anything about Charles, either. One wonders who might.

[A couple hundred words of bickering]

The Admiral asks Josiah what he would do about a nephew who "has got a liking for this girl, who has had her neck bitten by a vampyre, you see."

[Josiah:] "Taking, my dear sir, what in my humble judgment appears a reasonable view of this subject, I should say it would be a dreadful thing for your nephew to marry into a family any member of which was liable to the visitations of a vampyre." "It wouldn't be pleasant." "The young lady might have children." "Oh, lots," cried Jack. "Hold your noise, Jack." "Ay, ay, sir." "And she might herself actually, when after death she became a vampyre, come and feed on her own children."

I did not remember any of this when I wrote the Consequences of Your Decision to Propagate the Family Stain section, and I'm starting to feel very smart for putting it in.

"Whew!" whistled Jack; "she might bite us all, and we should be a whole ship's crew o' wamphigaers. There would be a confounded go!"

For some reason, this bit is just absolutely fucking iconic to me. Indeed, Jack. In case of wamphigaers, the go would be confounded.

The Admiral steels himself to see "to the very bottom of this affair, were it deeper than fathom ever sounded. Charles Holland was my poor sister's son; he's the only relative I have in the wide world, and his happiness is dearer to my heart than my own." Having changed his mind about d-- -- d lawyers, Jack Pringle wishes Josiah Crinkles well, and he and the Admiral resolve to go find Charles at once—"our nevy," that is to say, "nephew," so—our nephew? Well, Jack and the Admiral definitely have an "argumentative life partners" vibe, be they employer and walley or not. So they'll go see Charles,

"see the young lady too, and lay hold o' the wamphigher if we can, as well, and go at the whole affair broadside to broadside, till we make a prize of all the particulars, arter which we can turn it over in our minds agin, and see what's to be done." "Jack, you are right. Come along."

As I've said, I did read halfway through the entire serial some ten years ago. These two are (give or take) 67% exhausting and 33% hilarious when deployed at just the right narrative moment. I'll run the numbers again once we're a few more chapters in.

Varney the Vampire masterpost

#varney the vampire#vampire studies#wampfaster wamplonger wamphigher#wamphigaers#a confounded go#vampires#long post#recaps

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

I gotta write a fanfic about the adventures of George Bannerworth & what he does after disappearing from the narrative

Like after a life of neglect he uses his forgettability for the better and is secretly behind all the bizzare unexplained plot points

Maybe he joins the townspeople in their LARKS

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Varney The Vampire Canon as Understood by the Antiques Freaks Patreon Exclusives:

Jack and Admiral Bell are gay married

Flora Bannerworth is her generation's Slayer but can't hear her calling because, as an upper class British woman, she lacks two braincells to rub together

Mister Chillingworth doesn't want there to be a vampire panic because he has been stealing bodies out of the cemetery for years

A vampire is a type of fish

The dead butcher is gay and also a vampire

The dead gay butcher returned just long enough to turn his boyfriend and possibly their adopted son. Either way, they are all living their best life in the next town over.

Sir Frances Varney doesn't have any special vampire abilities except leaving a bad situation so fast he can cut a perfect outline of himself in a building's outer wall

George Bannerworth slept through the Bannerworth's evacuation of their house and now lives like Kevin in Home Alone in the abandoned wing of the hall

Sir Frances is actually kind of hot

Let me know if I missed any

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

in Varney the Vampire, there is approximately 1 female lead per story setting, but discounting all the little vignettes there are 2 main ones (Clara Crofton and Flora Bannerworth). clara dies in her section, but flora lives, begging the question...

in dracula there is a cowboy and the female lead lives. in nosferatu there is no cowboy and the female lead dies. ergo, the existence of a cowboy is highly important for the survival of the female lead in a gothic vampire story.

#varney the vampire#memes#poll#other classic lit vampire stories bonus round:#the presence of a cowboy in The Vampyre could have saved ianthe#clarimonde should have gone after a cowboy instead of a catholic priest then maybe she wouldn't have gotten got#laura survives carmilla right? so there must be a cowboy in there somewhere#the widow in the black vampyre gets vamped but then turns back to human at the end#implying the existence of Schrodinger's Cowboy

33K notes

·

View notes

Link

Our friend Olivia @0bfvscate rejoins us for the chapter wherein the Bannerworths FINALLY LEAVE THE DAMN HALL! (Except for George, who is left behind Home Alone style.)

Check out Olivia's short speculative fiction and essays at ofcieri.com, and buy her spooky urban fantasy novel LORD OF THUNDERTOWN!

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Trick or treat

take good care of him

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Varney the Vampire, Chapter 35: And Another Thing

[Previous chapter] [Next chapter]

Flora attempts to explain to Henry what just happened, but he shakes her off and runs after Varney. George and Marchdale also show up. Varney appears to have vanished.

Suddenly, there is an explosion of gunfire from one of the windows of the house, and they hear the admiral shouting. Marchdale explains that the admiral has duct taped seven guns together to make one enormous supergun that can be fired with a single match, intending to use this weapon against the dastardly vampyre. Henry's response to this is, and I quote, "Well, well, he must have his way."

Henry conjectures that Varney must have run off into the forest, so he, George, and Marchdale all split up to search the woods for him. All intend to shoot to kill, although Marchdale expresses doubt that Varney can be killed by bullets since they've already shot him like 6 times. The author then pauses to explain for no less than 5 paragraphs how Henry came to wake up, discover Flora was missing, wake up the others, and go looking for her.

Flora, meanwhile, is psyching herself up to walk back to the house when Varney pops out of some bushes and resumes their conversation as though nothing had happened. It turns out the author forgot to have Flora ask him about Charles last chapter, so he wrote Varney back in for a second in order to deal with that plot thread. Varney assures Flora that Charles is fine probably, and will return to her once she has sufficiently distanced herself from Bannerworth Hall. He then fucks off Tuxedo Mask style before Flora can ask him any followup questions.

Henry, George, and Marchdale, having failed to find Varney since he was never actually in the woods, turn around and go back to the house. Henry and George resolve to destroy Varney at all costs; Marchdale urges them not to be rash, and they reply that he cannot possibly understand the strength of their feelings. Marchdale, hurt by this, tells them that he's not the stepdad, he's the dad that stepped up. He then advises them to listen to whatever Flora wants to do, which they agree to.

This chapter was so pointless. Nothing actually happened except that Rymer realized he forgot Charles existed when he was writing last chapter, and that he should probably put in an exchange between Varney and Flora that addresses him. "That's crazy," you may say. "How could he completely forget about one of his own main characters?" To which I say: lol, lmao even.

The admiral's insane gun setup is never mentioned again, which I think is a shame. He should have brought it to a duel.

The brief followup conversation between Flora and Varney that occurs in this chapter is utterly brazen in how transparent an ass-covering it is. Varney may as well have turned to look at the camera and said, "Sorry, readers! I almost forgot to address this plot point!"

"Have you anything to add to what you have already stated?" "Absolutely nothing, unless you have a question to propose to me—I should have thought you had, Flora. Is there no other circumstance weighing heavily upon your mind, as well as the dreadful visitation I have subjected you to?" "Yes," said Flora. "What has become of Charles Holland?"

"I was just wondering if you had any followup questions, Flora, maybe about a certain guy you were in love with who vanished under extremely suspicious circumstances and whose disappearance stressed you out so much that it was actually what caused you to sleepwalk out here? You know, in case you happened to have entirely forgotten about that last chapter for some reason?"

Flora is annoyingly passive (I am annoyed at the author, to be clear); when Varney all but confesses to being responsible for Charles' disappearance, she responds with joy and gratitude that he's promised her Charles will return, and not an ounce of suspicion or anger that he was the one responsible for indisposing Charles in the first place.

"Listen. Do not discard all hope; when you are far from here you will meet with him again." "But he has left me." "And yet he will be able, when you again encounter him, so far to extenuate his seeming perfidy, that you shall hold him as untouched in honour as when first he whispered to you that he loved you." "Oh, joy! joy!" said Flora; "by that assurance you have robbed misfortune of its sting, and richly compensated me for all that I have suffered."

Girl he kidnapped your fiance. At least yell at him a little bit.

"Adieu!" said the vampyre. "I shall now proceed to my own home by a different route to that taken by those who would kill me." "But after this," said Flora, "there shall be no danger; you shall be held harmless, and our departure from Bannerworth Hall shall be so quick, that you will soon be released from all apprehension of vengeance from my brother, and I shall taste again of that happiness which I thought had fled from me for ever." "Farewell," said the vampire; and folding his cloak closely around him, he strode from the summer-house [...]

Henry is making a valiant attempt to channel Jonathan Harker.

"He shall," said Henry; "I for one will dedicate my life to this matter. I will know no more rest than is necessary to recruit my frame, until I have succeeded in overcoming this monster; I will seek no pleasure here, and will banish from my mind, all else that may interfere with that one fixed pursuit. He or I must fall."

If only he had a giant knife that he could sharpen menacingly whenever Marchdale tries to talk him out of doing violence. That would really elevate this book, I think.

Marchdale advises Henry to submit to Flora's counsel, and I...am suspicious. Knowing that Flora is going to tell them to leave, playing right into Varney's hands, I can't help but wonder if there's intended to be a misogynist moral lesson packaged in here a la Marjorie Lindon in The Beetle (note: do not read The Beetle) where listening to Flora turns out to be A Bad Thing. Ultimately, due to the unplanned nature of this story, this never resolves into making a statement in either direction, so it doesn't really matter; but it's going to nag at me.

#varney the vampire#varney summary#henry bannerworth#george bannerworth#marchdale#flora bannerworth#sir francis varney#this is a rymer hate blog

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Congratulations on making it through the whole thing! Ten days is some seriously impressive speed-reading. I can answer at least a few of your questions, as tumblr's resident Guy Who Has Made Varney The Vampire Their Whole Personality.

Most of them can be answered with "no, this thing was not planned in the slightest, and the author clearly never once went back to read anything he'd previously written". I do think he may have had a vague outline of where he wanted the story to go at the very beginning, just because there are a few lines hinting at Marchdale's betrayal that feel glaringly obvious on a reread. But he starts to lose the plot around the same time the Hungarian nobleman (or Floyd Dracula, as I call him) is introduced, and by the time we cut away to Anderbury he's definitely lost the plot.

In fact, I'm fairly confident that the story's direction was changed last-minute in between the conversation Varney has with Charles in the empty house, and the one he has with the Bannerworths after he takes shelter in their home. Floyd was GOING to be relevant, and Varney almost had yet another backstory in which - as far as I can figure - Floyd was going to turn out to be the gambler Varney and Marmaduke killed, and Varney's vampirism possibly was going to have been a result of that incident. (I swear I'm not pulling this out of my ass, I have quotes to back me up.) For whatever reason, though, the author pivoted instead to "Varney was never a vampire, he just got Frankensteined back from the dead by Chillingworth", and Floyd, now left with nothing to do, was tossed aside. Incidentally, the various conflicting accounts of Varney's past and Marmaduke's death create a time discrepancy in which Marmaduke died either a year ago or like 10-20 years ago, depending which account you're listening to.

Once you start paying attention the inconsistencies rack up like crazy. George Bannerworth disappears about 40 chapters in. At the end of the book, Mrs. Crofton goes from "alive and present in the narrative" to "has been dead for years" in the space of a few chapters.

As for why only one of Varney's dead victims becomes a vampire, it appears to be because he has to raise them from the dead on purpose, which is why we get the scene in there of Varney doing a funny little ritual on Clara's body.

I too would like to know more about the vampire group. How do they assemble? How do they determine who becomes a new vampire? Why do they all carry matching shovels?

Somehow I was expecting the final mob count to be higher than that.

“You don’t know these people, do you?” [Varney] asked Ruthven on the way up.

“Not as far as I’m aware,” said Ruthven. “It’s entirely possible they might have read that godawful Polidori book; in which case this will be extremely embarrassing.”

“Not as embarrassing as Varney the Vampyre, or The Feast of Blood,” said Varney drily. “Practically nothing is as embarrassing as that. Polidori at least wasn’t being paid by the word.”

—Dreadful Company, Vivian Shaw

Who's more out of their mind: James Malcolm Rymer, for writing 667,000 words of Varney the Vampire, or me for reading all of them in ten days?

I have no idea how to feel or to surmise what I've just experienced. On the one hand, Sir Francis Varney may now be my favorite vampire in literature, and whenever this book got me interested, it was sometimes one of the most fascinating vampire stories I've ever read.

I wasn't expecting such an early installment in the vampire fiction genre to be so sympathetic toward the vampire. I definitely was not expecting the vampire to eventually befriend his victims, or to refuse on multiple occasions to kill, or to try and help those he had terrorized as a form of repentance.

Granted, even when I was fully on board with the story, it still had a number of baffling elements. The romantic dialogue of this novel is so atrocious that it makes the Star Wars prequels look like one of Shakespeare's love stories in comparison. The comic relief duo of the admiral and his valet consisted of two jokes only (they speak in sailor slang and fight all the time) which were promptly pounded into the ground. At least six times in this book, possibly more, the narrative stopped so the author could write a chapter just consisting of transcribing what the characters were reading. Because he was getting paid by the word.

Despite all of this, I was fully on board up until Varney's would-be wedding as the Baron failed. After that, we got treated to multiple instances, each spanning several chapters, in which Varney would again pass himself off as some rich guy, try to marry a young woman, and then get exposed and run away. I'm guessing those chapters sold really well and that's why Rymer kept doing those stories? Or else he was just out of ideas. I don't see why those chapters would have sold especially well because they were short on vampire nonsense and chock full of wedding preparations and negotiations. I don't know much about the target audience for penny dreadfuls, but I would imagine they would care more about action than the services hired for a wedding breakfast.

And then once the endless marriages stopped, we got several more chapters of Varney biting a woman, getting caught, and running away. The story only picked back up in the last ten percent of the novel, when Rymer finally did something new by having one of Varney's victims become a vampire herself. Unfortunately, she got finished off pretty quickly and then the novel just ended.

(I am not complaining about the ending. The ending was a hell of a thing and gave me all sorts of emotions. But we could have had Varney's exploits with a newbie vamp instead of Failed Wedding Attempt 875)

Also, I'm assuming that Rymer did not plot this story out before he began? Varney's past changes constantly, sometimes within maybe thirty pages of the last backstory we were given. He's a deceased ancestor of the Bannerworths who took his life a hundred years ago! He's an executed highway robber, resurrected maybe a decade ago at most by a doctor's experiments, Frankenstein-style! He's been a vampire for 180 years and became one by murdering an innocent woman! He lived as mortal during the reign of Henry the Fourth! He lived as a mortal during the reign of Charles the First, and became a vampire after accidentally killing his son by striking him in anger!

If it were just Varney's past that was inconsistent, I'd say he was lying or had lived and died so many times that he genuinely forgot which death was the first one. But there are weird inconsistencies throughout the novel. What was up with the document Varney and Marchdale tried to force Charles to sign? Does Varney have a scar on his forehead or his cheek? Why did one girl who died of Varney become a vampire and the other one didn't? And most importantly to me, the hell was up with the Hungarian nobleman?

Why bother to introduce another vampire if it's going to lead to nothing but a red herring where the reader briefly thinks that the baron isn't Varney, and rather that Varney is the vampire that the baron killed?

Granted, roughly two thousand pages later, when a brood of vampires assemble to resurrect a new vampire, then probably the Hungarian nobleman comes back to speak a whole two sentences to Varney, about how they met at an inn once and also Varney used to hang with people named Bannerworth.

(I need to know more about this vampire group that assembles to resurrect vampire newbs. How does that work? Do they just sense them? Do they get pulled there by vampire power?)

And what was up with that time skip? Did we need to introduce Mr. Bevan as a sympathetic character when the entire Bannerworth family already were sympathetic to Varney?

I just don't know, man.

Also, Rymer hates Quakers. And Jewish people. And Catholics. And evangelicals. And organized religion in general. And Scots. And Americans, I think. Now, this is not at all rare for the time. Stoker and Wilde and many other of their contemporaries would also write their prejudices into their stories decades later. But they didn't write a book longer than War and Peace that had big stretches of nothing except weird diatribes of whatever they disliked.

Anyway.

Can I in good conscience recommend that anyone read this?

Not in its entirety. If someone wants to do an abridged version have at it I guess. Or read it in its entirety over the span of months instead of ten days like I did. My brain is going to explode.

The first half was good. The end stuff was good. I want to wrap Varney up in a number of blankets and feed him some of my blood. And thank God he's in the public domain, because he deserves better than an endless slog of miseries that quickly goes off the rails once he leaves the Bannerworths.

Final mob count: 11

Final failed vampire wedding count: 4

I should have kept track of all the times Varney died and/or got shot, but I forgot

Three stars

#varney the vampire#varney spoilers#lore#time knots and other fuckery#sir francis varney#floyd dracula#this is a rymer hate blog#long post

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Varney the Vampire, Chapter 2: A Conspicuous Lack Of Lizard Fashion

[Previous chapter] [Next chapter]

The other occupants of the house - two young men, their mother, and Some Guy - are awakened by a scream. They stand around talking about it for several minutes instead of taking action, but eventually conclude that By God, It Came From Flora's Chamber! We Must Investigate At Once! After Another Page Or So Of Pointless Dialogue, Of Course. And so, armed with pistols, a crowbar, and enough lines of pointless chatter to pay Rymer's rent for the week, the two young men (Henry and George) and the older gentleman (Marchdale) force the door to Flora's room. Henry rushes inside and is immediately tackled and bowled over by the vampire, who then rushes for the window. Marchdale whips out his 18th-century Glock 17 and fires on the creature; it's unclear whether the bullet connects. The vampire turns to look at them for just long enough for us to see that his face is now flushed with fresh blood; then he jumps out the window, cackling. The three men run after him; the mother, who is not named now or ever, runs into the bedroom and faints at the sight of the bloodied Flora.

They find the vampire trying and failing to jump over the garden wall, and spend several minutes watching him do this instead of doing anything to stop him. Finally, just as he manages to reach the top of the wall, Henry shoots him and he falls off the other side.

Chapter 1, for all its grammatical clumsiness, was decently engaging and fun to read. Chapter 2 rapidly introduces four new characters, gives the name of only one of them, and drops a solid wall of conversation between the four with almost no dialogue tags to distinguish them. The effect feels a bit like being dropped down an open manhole.

As Flora's line hinted in Chapter 1, Rymer has a remarkable anti-gift for writing dialogue. His plodding, stilted, meandering conversations sound like no human being who has ever lived, and frequently disregard the urgency of a situation in favor of being as wordy as possible. A small sample:

"Did you hear a scream, Harry?" asked a young man, half-dressed, as he walked into the chamber of another about his own age.

"I did—where was it?"

"God knows. I dressed myself directly."

"All is still now."

"Yes; but unless I was dreaming there was a scream."

"We could not both dream there was. Where did you think it came from?"

"It burst so suddenly upon my ears that I cannot say."

There was a tap now at the door of the room where these young men were, and a female voice said— "For God's sake, get up!"

"We are up," said both the young men, appearing.

"Did you hear anything?"

"Yes, a scream."

And on and on it goes. Boys, your sister is fucking under attack - you might want to move a LITTLE faster than this!

Eventually Mr. Marchdale, who is not their father but a family friend who is staying in their house for whatever reason, spurs the young men into action, and the three of them set to work prying open the locked door to Flora's room. Varney's feeding must be VERY loud, as they can hear it through the thick oak door:

"I hear a strange noise within," said the young man, who trembled violently.

"And so do I. What does it sound like?"

"I scarcely know; but it nearest resembles some animal eating, or sucking some liquid."

I will restrain myself from making the obvious joke.

The three men spend a few minutes forcing the door with a crowbar. Then, out of nowhere, the narration drops the following gem:

How true it is that we measure time by the events which happen within a given space of it, rather than by its actual duration.

Very ADHD of you, Rymer. I'm not about to armchair diagnose the man - I do not think this paid-by-the-line vampire story is particularly insightful of the way his mind works - but I will say that reading this story is what having unmedicated ADHD feels like. My brain, bereft of dopamine, is getting paid by the thought.

Anyway.

Henry runs into the room so fast that the candle he's holding nearly goes out; then Varney leaps at him from the bed like a cat with the zoomies and knocks the candle out of his hand, putting it out for real.

But Mr. Marchdale was a man of mature years; he had seen much of life, both in this and in foreign lands; and he, although astonished to the extent of being frightened, was much more likely to recover sooner than his younger companions, which, indeed, he did, and acted promptly enough.

Doesn't Rymer just have such a way with words.

Marchdale draws a pistol, which the narrator takes great pains to point out is a REAL gun, NOT a toy, and fires on Varney, which doesn't appear to do much except piss him off. Varney turns to him, and we see that his face is reddened with blood, and his eyes are now glowing and emitting little crackling lightning bolts. Yes, really. For a moment he seems about to pounce; then he changes his mind and leaps out the window instead.

"God help us!" ejaculated Henry.

I love reading 19th century books.

Marchdale gives chase, with Henry and George trailing behind him. At some point he manages to grab hold of Varney, tearing off a scrap of his clothing. The three of them find the vampire trying to jump over a 12-foot-high garden wall. For some reason, Varney's repeated failed attempts to jump over the wall are horrifying to them rather than comical, and they stand there watching him bound at the wall like a cat in a viral video, falling to the ground over and over again. It's not until he finally manages to reach the top of the wall that any of them think "hey wait, maybe we should try and stop him or something." At that point, Henry shoots him, and he falls down on the other side of the wall.

Next: We check back in on poor Flora.

#varney the vampire#varney summary#sir francis varney#henry bannerworth#george bannerworth#mrs. bannerworth#flora bannerworth#marchdale#this is a rymer hate blog

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Varney the Vampire, Chapter 8: Checkmate Atheists

[Previous chapter] [Next chapter]

The party looks around the vault. It's spoopy in there, creppy even, and Henry and George are creeped out. Everyone begins to examine the coffins in the vault, only to find that the older coffins are so fragile that they crumble to dust with a touch. Finally they find a coffin plate with the name of the ancestor they are looking for, who is now named Marmaduke instead of Runnagate for some reason. It's been detached from its coffin, so they scan the coffins with no plate to figure out which one it came from. Eventually, they find the matching coffin; the death date is off by a century, but no one comments on this, so it appears to be a mistake by the author.

The coffin opens easily, and appears to be empty except for a few rotten scraps of cloth. Chillingworth confirms that no dead body appears to have ever been placed in the coffin, at least not one that underwent any amount of decomposition. This news is greatly disheartening to Henry, George, and Marchdale, but not to Chillingworth, who makes the bold claim that he would not believe in vampires if one bit him on the neck. He goes on to say that he also does not believe in miracles, because he believes every phenomenon has a scientific explanation.

The group leaves the vault. Henry remarks that his family is cursed by Heaven, which Chillingworth scoffs at. As they close up the vault and leave the church, Chillingworth attempts to counsel Henry, telling him that the best thing to do is stubbornly refuse to accept his situation, and get really angry instead. Henry comments that this approach sounds a lot like defying Heaven, to which Chillingworth replies that it is nothing of the sort, because if God didn't want us to defy our circumstances He would not have given us defiance in the first place. He then makes the mistake of saying all religion which cannot be rationally explained is merely allegory, and Henry straightens up and gives a moving religious speech, God's Not Dead style, which stuns Chillingworth into silence. The narrator then soapboxes a whole bunch about how religious people always win arguments with atheists because their arguments are so much more true and correct.

My god this chapter is wild. Can you believe the part where they break into a grave looking for a vampire is the boring half of this chapter?

Last time I commented that Henry and George seemed not to know how decomposition worked. This time, it becomes obvious that Rymer himself does not know how decomposition works.

"Some of the earlier coffins of our race, I know, were made of marble, and others of metal, both of which materials, I expect, would withstand the encroaches of time for a hundred years, at least." [...] When, however, they came to look, they found that "decay's offensive fingers" had been more busy than they could have imagined, and that whatever they touched of the earlier coffins crumbled into dust before their very fingers.

How fucking old are these coffins, Rymer??

Next we get a stunning display of just how much Rymer Does Not Care about consistency. First off, Runnagate Bannerworth has changed names - he is now Marmaduke. I don't know how Rymer bungled the name this badly. The name "Runnagate" is never mentioned again.

(Eagle eyed readers may note that I tagged Dad Bannerworth as "marmaduke bannerworth" a couple chapters ago. This is because Rymer later changed his mind on who Marmaduke is.)

The coffins in this vault consist of two layers, an outer and an inner coffin. The outer coffins are mostly wood, with coffin plates affixed to the top, while the inner ones are metal and have inscriptions engraved on them directly. The coffin plate and coffin inscriptions for Marmaduke Bannerworth are as follows:

"Ye mortale remains of Marmaduke Bannerworth, Yeoman. God reste his soule. A.D. 1540."

"Marmaduke Bannerworth, Yeoman, 1640."

Most probably one of these is a typo; I find it hard to imagine even Rymer forgetting which century a guy died in within the space of a single page. It could also be that he truly gave that little of a shit.

Chillingworth roots around in Marmaduke's coffin for a bit before dispassionately reporting that it contains no body, nor any signs of one having decomposed. It's at this point that the chapter really starts to get interesting, as Rymer takes Chillingworth's established character as a skeptic and dials it up as far as it will possibly go, culminating in a Christian-vs-atheist debate between him and Henry and a fairly lengthy editorial from Rymer himself. It isn't clear to me just what Rymer is trying to do with the character of Chillingworth; at all other points in the story, he appears to be a voice of reason and a cool head, with his viewpoints and actions largely considered to be sane and reasonable ones, examples worthy of emulation. Yet here, for a single chapter, Rymer puts him on a soapbox and uses him to make a point about how much he, the author, hates atheism. Evidently Rymer's careless inconsistency extends to the themes of the text and the treatment of the characters; Chillingworth is the model of reason until Rymer needs him not to be, then he becomes a strawman who believes in skepticism like a religion, and whose cold objectivity is evidently meant to come across as harsh and unreasonable.

"Then you are one who would doubt a miracle, if you saw it with your own eyes." "I would, because I do not believe in miracles. I should endeavour to find some rational and some scientific means of accounting for the phenomenon, and that's the very reason why we have no miracles now-a-days, between you and I, and no prophets and saints, and all that sort of thing." "I would rather avoid such observations in such a place as this," said Marchdale. "Nay, do not be the moral coward," cried Mr. Chillingworth, "to make your opinions, or the expression of them, dependent upon any certain locality."

Interestingly, Chillingworth is not a true atheist, professing to a belief in Heaven. I'm not sure if this is because true atheism wasn't really a Thing yet in the 1840s or Rymer just chickened out.

"I am satisfied," said Henry; "I know you both advised me for the best. The curse of Heaven seems now to have fallen upon me and my house." "Oh, nonsense!" said Chillingworth. "What for?" "Alas! I know not." "Then you may depend that Heaven would never act so oddly. In the first place, Heaven don't curse anybody; and, in the second, it is too just to inflict pain where pain is not amply deserved."

Oddly, even though the entire back half of this chapter is setting up Chillingworth's extreme skepticism for Henry to get a sick Christian dunk on at the end, the narrative still seems to want to position Chillingworth's point of view as an admirable one:

Mr. Chillingworth's was the only plan. He would not argue the question. He said at once,— "I will not believe this thing—upon this point I will yield to no evidence whatever." That was the only way of disposing of such a question; but there are not many who could so dispose of it[...]

Rymer is definitely trying to make a point in this chapter - he has all the subtlety of an elephant playing a church organ - but he's muddied it so much that it's difficult to know what to take away here. Am I supposed to like or dislike Chillingworth? Am I meant to agree with him or scoff at his viewpoints? The author himself seems unable to make up his mind.

As we approach the God's Not Dead Epic Dunk, Chillingworth imparts some advice to Henry which would be right at home on Twitter:

"Now, when anything occurs which is uncomfortable to me, I endeavour to convince myself, and I have no great difficulty in doing so, that I am a decidedly injured man."

He has a very high opinion of his own opinions.

"I know these are your opinions. I have heard you mention them before." "They are the opinions of every rational person. Henry Bannerworth, because they will stand the test of reason[...]"

And now we come to the climax of the chapter, when Henry finally speaks out in defiance of Chillingworth's opinions. With apologies for the long ass quote:

"I consider so, and the most rational religion of all. All that we read about religion that does not seem expressly to agree with it, you may consider as an allegory." "But, Mr. Chillingworth, I cannot and will not renounce the sublime truths of Scripture. They may be incomprehensible; they may be inconsistent; and some of them may look ridiculous; but still they are sacred and sublime, and I will not renounce them although my reason may not accord with them, because they are the laws of Heaven." No wonder this powerful argument silenced Mr. Chillingworth, who was one of those characters in society who hold most dreadful opinions, and who would destroy religious beliefs, and all the different sects in the world, if they could, and endeavour to introduce instead some horrible system of human reason and profound philosophy. But how soon the religious man silences his opponent; and let it not be supposed that, because his opponent says no more upon the subject, he does so because he is disgusted with the stupidity of the other; no, it is because he is completely beaten, and has nothing more to say.

I hope my flippant jokes throughout this commentary haven't given the wrong idea here; I have no desire to knock on religion as a whole. But Rymer's soapbox at the end of this chapter is laughably pathetic. Henry's "argument" really isn't arguing anything at all; he's just stating a declaration of faith. The author's two paragraphs of lecturing the audience directly read like bluster. This is a really sad defense of faith; whether you are a believer or not, I think we can all agree that this passage is pretty cringe.

Rymer has one last psychic gutpunch to deliver before he closes the chapter out:

Mr. Chillingworth, who was a very good man, notwithstanding his disbelief in certain things of course paved the way for him to hell,

"Chillingworth is a good guy. He's going to hell though."

What the fuck, Rymer.

Next: FLORA'S GOT A GUN, YOU BETTER RUN

#varney the vampire#varney summary#henry bannerworth#george bannerworth#marchdale#dr. chillingworth#time knots and other fuckery#this is a rymer hate blog#perhaps in this post more than ever before

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Varney the Vampire, Chapter 7: Much Ado About Matches

[Previous chapter] [Next chapter]

It's morning now, and Flora is awake and feeling much better. Henry and George agree to not tell her about the events of the previous night. Henry is fixated on the idea of investigating the family crypt, so George and Marchdale agree to accompany him on an expedition. Marchdale says they ought to go secretly in the dead of night, and the others agree that this is the sensible and reasonable thing to do. The only trouble is that all three of them going would leave Flora unprotected. Henry talks to Flora, without actually telling her where they're going, and she says she will be alright by herself. Henry gets the bright idea to leave a couple of guns with her, so that if the vampire comes by again she can blast him. Flora, who apparently has experience with firearms and is a good shot, agrees to this. Marchdale suggests they invite Chillingworth to come along, which they do.

That evening, Henry, George, and Marchdale set off for the church where the Bannerworth family vault is located, armed with tools for a break-in. However, Marchdale has forgotten to bring matches, even though it was his idea to visit the tomb at night. Fortunately, at the exact moment he realizes this they run into Chillingworth, who happens to always carry matches on his person. Convenient!

They reach the church, and the author pauses to complain for an entire paragraph about old buildings in Kent being pulled down to make way for modern ones. They set about breaking into first the church and then the vault. Chillingworth gripes extensively about there being no secrets to find here except the smell, which begs the question of why he tagged along on this mission in the first place.

Inside the vault, Marchdale pulls out the candles he brought along and realizes that he did bring matches after all, rendering a whole page of this story entirely pointless.

In this chapter, it begins to become clear that Flora is by far the most competent character in the cast. It's a damn shame, then, that she is never allowed to do anything. From a different author I might take this as commentary; however, in Rymer's case it's merely a symptom of poor writing. Flora is competent because she never gets to do anything, meaning the author does not have to hand her the idiot ball repeatedly in order to keep his plot going.

Henry and George have a long conversation about decomposition rates, during which they show an alarming lack of knowledge about how bones work. Boys, I'm pretty sure skeletons keep for more than a hundred years.

"What then, do you suppose, could remain of any corpse placed in a vault so long ago?" "Decomposition must of course have done its work, but still there must be a something to show that a corpse has so undergone the process common to all nature. Double the lapse of time surely could not obliterate all traces of that which had been."

We learn Marchdale went out to search the garden one more time, but found no trace of any vampire. Once again, he shies away from confronting the reality of the situation. All these characters actively shun being genre-aware.

"The fact is, that although at your solicitation I went to bed, I could not sleep, and I went out once more to search about the spot where we had seen the—the I don't know what to call it, for I have a great dislike to naming it a vampyre." "There is not much in a name," said George. "In this instance there is," said Marchdale. "It is a name suggestive of horror."

Marchdale is very much in favor of visiting the tomb, reasoning that if they find no evidence of a vampire then they'll put their minds at ease, and if they do, then they'll only be in roughly the same place they were already. He then proposes that they conduct their mission in secret, in the dead of night, reasoning that since daylight cannot get into the tomb anyway, there's no harm in going at night. I would accept this logic in Minecraft, but here...well, see what I said about genre awareness. This is how you get eaten by vampires, dude. At the very least, you're going to psych yourselves out way more going at night. Don't you remember the daylight has literal physical properties of soothing the mind?

"There is ample evidence," said Mr. Marchdale, "but we must not give Flora a night of sleeplessness and uneasiness on that account, and the more particularly as we cannot well explain to her where we are going, or upon what errand."

In a better story, they would have told Flora what they were doing, and she would have insisted on coming with them, guns and all. Alas.

"Oh, I shall be quite content. Besides, am I to be kept thus in fear all my life? Surely, surely not. I ought, too, to learn to defend myself." Henry caught at the idea, as he said,— "If fire-arms were left you, do you think you would have courage to use them?" "I do, Henry." "Then you shall have them; and let me beg of you to shoot any one without the least hesitation who shall come into your chamber." "I will, Henry. If ever human being was justified in the use of deadly weapons, I am now."

This exchange still kind of rules though.

After some discussion of Flora by Henry, George, and Marchdale, during which they conclude that she is exceptional and that "most" women her age would never have recovered from what she experienced (this isn't even true in the universe of Varney the Vampire), we reach the tedious and pointless Three Stooges routine with the matches. What stands out most about this sequence is how unnecessary it is; it seems to only exist to pad the wordcount, and has the side effect of making all the characters look like incompetent clowns.

Many words are spent on describing the church; most of them are not very descriptive.

There were numerous arched windows, partaking something of the more florid gothic style, although scarcely ornamental enough to be called such. The edifice stood in the centre of a grave-yard, which extended over a space of about half an acre, and altogether it was one of the prettiest and most rural old churches within many miles of the spot.

Rymer briefly pauses the story to grouse about something in the present day, a habit he will return to throughout the book.

In Kent, to the present day, are some fine specimens of the old Roman style of church, building; and, although they are as rapidly pulled down as the abuse of modern architects, and the cupidity of speculators, and the vanity of clergymen can possibly encourage, in older to erect flimsy, Italianised structures in their stead, yet sufficient of them remain dotted over England to interest the traveller.

Holy comma abuse, Batman.

Now give it up for...character breaking a small pane of glass, reaching a hand through, and undoing a window clasp!

"The only way I can think of," said Henry, "is to get out one of the small diamond-shaped panes of glass from one of the low windows, and then we can one of us put in our hands, and undo the fastening, which is very simple, when the window opens like a door, and it is but a step into the church."

I told you Rymer loves doing this.

Chillingworth continues to be irritating.

"The secrets of a fiddlestick!" said the doctor. "What secrets has the tomb I wonder?" "Well, but, my dear sir—" "Nay, my dear sir, it is high time that death, which is, then, the inevitable fate of us all, should be regarded with more philosophic eyes than it is. There are no secrets in the tomb but such as may well be endeavoured to be kept secret."

He's referring to the smell of decay in that last sentence. I dunno, Chillingworth, I think tombs and graves frequently hold secrets. There are entire scientific and criminal investigative fields devoted to this. If you're so convinced there are no secrets to be uncovered here, then why the hell did you come along in the first place?

The chapter ends with the infuriating conclusion to the match saga.

"Why, these are instantaneous matches," said Mr. Chillingworth, as he lifted the small packet up. "They are; and what a fruitless journey I should have had back to the hall," said Mr. Marchdale, "if you had not been so well provided as you are with the means of getting a light. These matches, which I thought I had not with me, have been, in the hurry of departure, enclosed, you see, with the candles. Truly, I should have hunted for them at home in vain."

You didn't have to write it this way, Rymer.

Next: Several narrative inconsistencies are unearthed

#varney the vampire#varney summary#henry bannerworth#george bannerworth#flora bannerworth#marchdale#dr. chillingworth#this is a rymer hate blog

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Varney the Vampire, Chapter 18: Talk Shit Get Hit

[Previous chapter] [Next chapter]

The bell at the gate continues to ring wildly until George, annoyed, goes to answer it. It's Admiral Bell and Jack Pringle! They're here to see Charles, but they're very bad at explaining themselves and George is already pissed off.

While the three of them argue, Jack Pringle spots a commotion some distance away, which turns out to be Varney and Marchdale having an argument. Suddenly, Varney bitchslaps Marchdale in the face, and he falls to the ground.

Varney runs off, and Marchdale returns to the others. The Admiral and Jack reintroduce themselves in obnoxiously nautical fashion. Charles and Henry show up, and Charles is surprised to see his uncle. He promises to give him a full explanation once he's gotten permission from Henry to do so.

The narrative now goes on hold to explain Charles' situation in more detail. Charles has an inheritance waiting for when he turns 22; however, since the age of discretion (financial independence, I assume) is 21, his lawyer advised him to take a 2-year vacation in Europe to avoid being preyed on by money-lenders. This plan hit a snag when he met Flora while on his vacation, and fell for her so hard that he was unable to resist returning to England a little early to see her.

Charles meets with Henry, who grants him permission to tell Admiral Bell everything. He also asks Henry how Flora's doing; Henry replies that she's doing better, but could use something to distract her from The Horrors. Charles pulls a random short story out of his backpack and gives it to Henry to give to Flora.

Not much happens in this chapter; it's about two thirds sailor speak by volume. I'll skip right to the good part, which is MARCHDALE GETTING PUNCHED

HELL YEAH GET HIS ASS

Marchdale confirms for us another of Varney's precious few supernatural characteristics:

"I threatened to follow him, but he struck me to the earth as easily as I could a child. His strength is superhuman."

He can't lizard climb or shapeshift, but he sure can throw a punch.

The Admiral and Jack proceed to give Marchdale about the cartooniest introduction they can possibly muster:

"Oh, you may know my name as soon as you like," cried the admiral. "The enemies of old England know it, and I don't care if all the world knows it. I'm old Admiral Bell, something of a hulk now, but still able to head a quarter-deck if there was any need to do so." "Ay, ay," cried Jack, and taking from his pocket a boatswain's whistle, he blew a blast so long, and loud, and shrill, that George was fain to cover his ears with his hands to shut out the brain-piercing, and, to him unusual sound.

Jack Pringle's relationship to the Admiral is sort of clarified, sort of not? I for one am going to be gleefully misinterpreting the "not exactly a servant" line.

"Come in, sir," said George, "I will conduct you to Mr. Holland. I presume this is your servant?" "Why, not exactly. That's Jack Pringle, he was my boatswain, you see, and now he's a kind o' something betwixt and between. Not exactly a servant."

In another moment of surprising quality, I really like the first interaction between Charles and his uncle. The dynamic between them is a lot of fun.

"Your uncle!" said Henry. "Yes, as good a hearted a man as ever drew breath, and yet, withal, as full of prejudices, and as ignorant of life, as a child." Without waiting for any reply from Henry, Charles Holland rushed forward, and seizing his uncle by the hand, he cried, in tones of genuine affection,— "Uncle, dear uncle, how came you to find me out?" "Charley, my boy," cried the old man, "bless you; I mean, confound your d——d impudence; you rascal, I'm glad to see you; no, I ain't, you young mutineer. What do you mean by it, you ugly, ill-looking, d——d fine fellow—my dear boy. Oh, you infernal scoundrel." All this was accompanied by a shaking of the hand, which was enough to dislocate anybody's shoulder, and which Charles was compelled to bear as well as he could.

The banter between these two is delightful. Charles is less of a cartoon character than his uncle, and talks and acts accordingly, and the resulting conversational clash is incredibly entertaining.

"And here you see Admiral Bell, my most worthy, but rather eccentric uncle." "Confound your impudence." "What brought him here I cannot tell; but he is a brave officer, and a gentleman." "None of your nonsense," said the admiral.

The story now goes on hold in order to clarify what the deal is with Charles' two-year vacation.

A very few words will suffice to explain the precise position in which Charles Holland was.

By "a very few words" he means about 600, for the record.

Charles' little backstory is rather contrived and not very interesting. It's one of those details where, had the author not brought it up, I would not have bothered to ask. It does clue us into one thing: Charles is set to be loaded in the near future.

Charles goes to ask Henry's permission to tell his uncle about all the vampire drama, which is frankly unnecessary because Henry already said he could earlier when Admiral Bell was being introduced. The real purpose of their meeting, however, is for Charles to give Henry this random manuscript he happens to have on him, so Flora can read it as a distraction from her troubles. Why all the fuss about this? Haha. Well. We shall see.

Next: Varney the Vampire will return after this short break

#varney the vampire#varney summary#george bannerworth#admiral bell#jack pringle#marchdale#sir francis varney#charles holland#art#memes#this is a rymer hate blog

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Varney the Vampire, Chapter 5: My God, He's...Unfashionable!

[Previous chapter] [Next chapter]

After learning some troubling new facts about vampires, Henry sits around dissociating for 15 minutes before being interrupted by George, who's brought him a mysterious letter from one Sir Francis Varney. Varney is his neighbor, who recently moved into the neighborhood and wants to be friends, but apparently not enough to get the family's name right. Henry and George are introverts and don't want to be this guy's friend, so they resolve to ignore him and hope he goes away.

The full moon rises, and the brothers and Marchdale gather in Flora's room to keep watch while she sleeps. Marchdale suddenly remembers that he tore the vampire's clothes while chasing him the previous night, and pulls out the scrap of cloth. It looks (and smells) like part of a hundred-year-old coat. They all agree to simply pretend this little piece of evidence had never come up, until a few hours into their watch when Marchdale realizes that the scrap looks a lot like the outfit the guy in the portrait is wearing. This idea is so troubling to them that Henry and Marchdale immediately run across the hall to compare the two, and sure enough they match exactly. Henry mentions that, funnily enough, the man in the portrait was buried in his clothes.

Just then, they're interrupted by the sound of footsteps in the garden outside. They rush out with the intention of shooting the intruder, who they assume is the vampire, but it turns out to be Chillingworth. Chillingworth is a huge busybody, and couldn't resist lying in wait near the house to see if the supposed vampire would turn up. After reconvening briefly with George, Henry, Marchdale, and Chillingworth decide to conduct a sweep of the grounds. They climb up on top of the garden wall in order to have a better vantage point, and from there they spot a human figure lying under a tree. As they watch, the light of the moon falls upon the figure, and it begins to sit up and move.

Immediately, Marchdale shoots it, and it falls to the ground once more. The three of them run to investigate the figure, which gets up again and runs away from them, managing to evade them in the woods. All three of them remark that the figure appeared to be wearing hundred-year-old clothes. This cinches it for Henry, who is now completely convinced that the figure is his ancestor risen as a vampire. Chillingworth, on the other hand, stubbornly insists there's no such thing as vampires. Marchdale proposes that, to put the matter to rest, they go and visit the family crypt and investigate the tomb of Henry's ancestor for signs of disturbance.

We have word from Varney! He's sent Henry a letter, in which he calls him "Mr. Beaumont", which is hilarious and probably not intentional on the part of the author. Rymer is, as we will see, hopelessly bad at keeping his character names consistent. Varney lives in an estate called Ratford Abbey, which he moved into a few days ago and is located very close to the Bannerworth house.

Henry makes explicit for the first time the Bannerworths' dire financial situation, which has previously only been alluded to. The family was once wealthy, but successive generations of irresponsible Bannerworth men have depleted the family fortune, and now they are so poor that Henry fears they may not be able to keep their house much longer. Due to these circumstances, Henry doesn't want to make any new acquaintances. He is sure that Sir Francis Varney, being a gentleman, will pick up on this and not push the matter. Sure, Henry, let's go with that.

Like every girl I knew in middle school, the men in this book insist on doing everything in groups, and sure enough, Henry, George, and Marchdale all end up keeping watch in Flora's room. George insists on joining because his nerves will keep him up all night otherwise, and Marchdale insists because he, being older, has a cooler head than the other two. Immediately after making this assertion he tells them that if he catches the vampire tonight he's gonna wrassle it. The three of them reason that a three-person watch is not overkill because that way, if something distracting happens, they can send two people to investigate it and leave the third behind to keep watch. And boy, can these gentlemen get distracted. First they simply HAVE to go across the hall to compare Marchdale's cloth scrap with the painting (can it not wait until morning?), and then when Chillingworth makes his appearance they make a spur-of-the-moment decision to search the grounds of the house, on the grounds that Chillingworth thought he heard something on the other side of the garden wall.

Themes of denial and aversion continue to crop up. As evidence of the vampire mounts, the men continually remind each other not to do anything so rash as believe in the obvious conclusion:

"Say nothing of this relic of last night's work to any one." "Be assured I shall not. I am far from wishing to keep up in any one's mind proofs of that which I would fain, very fain refute."

Henry tells us that the ancestor in the portrait committed suicide. While never directly stated as such by the text, this is another hint; one folkloric belief is that death by suicide could lead to a person becoming a vampire.

Hearing a noise from outside, they assume the vampire has returned, and in doing so nearly shoot Chillingworth:

"Among the laurels. I will fire a random shot, and we may do some execution." "Hold!" said a voice from below; "don't do any such thing, I beg of you." "Why, that is Mr. Chillingworth's voice," cried Henry. "Yes, and it's Mr. Chillingworth's person, too," said the doctor, as he emerged from among some laurel bushes.

You know, it's funny that it never occurs to anyone that Chillingworth might be the vampire. So far the guy has been behaving very suspiciously.

Chillingworth says he heard something, so naturally a search of the grounds is in order. They return to Flora's room to tell George their plan. George agrees to stay behind, but not before arming himself with a sword, which he was keeping in his bedroom. I assume that sort of thing was more normal in the 18th century.

Chillingworth continues to be suspicious, or at the very least incredibly nosy:

"You are, no doubt, much surprised at finding me here," said the doctor; "but the fact is, I half made up my mind to come while I was here; but I had not thoroughly done so, therefore I said nothing to you about it."

They fetch a ladder from the garden, and use it to climb to the top of the wall Varney spent five minutes failing to climb the previous night. From this vantage point, they catch sight of a mysterious figure lying underneath a tree. Is the implication that he's been lying there all night?

The moon slowly rises higher in the sky, until the moonlight falls on the ground below the tree. As the light falls over the figure, they see him move, convulse, and then slowly begin to get to his feet - at which point Marchdale shoots him, laying him low again. Rude, Marchdale.

Of course, as Marchdale points out, they could stand around shooting him all night - so long as the moon shines on him, he'll keep getting up again. And get up he does, just in time to evade Chillingworth running at him. Off runs the vampire into the dark woods, where none of the three men dare give chase. Henry has been greatly shaken by all this, and finally sheds the air of forced denial which the men had all adopted. I would think this sensible if it led to him taking any action - stock up on garlic, perhaps? - but that's not how this book works. Believer or skeptic, all are equally incompetent. Case in point: Chillingworth, quite the opposite of Henry, stubbornly refutes the notion that what they just witnessed was in any way supernatural. Does he have an explanation, then, for what just happened?

"True; I saw a man lying down, and then I saw a man get up; he seemed then to be shot, but whether he was or not he only knows; and then I saw him walk off in a desperate hurry. Beyond that, I saw nothing."

You saw a man wearing hundred-year-old clothes, matching the appearance of the one who broke into the Bannerworth house last night, who in turn matches the appearance of their hundred-years-dead ancestor. At the very least you should suspect foul play of some kind.

Marchdale winds up being the voice of reason, as the only one of these dumbasses to come up with an actionable suggestion: hey, if we think this guy might be Vampire Runnagate Bannerworth, why don't we go check on him and see if his grave's been disturbed? The chapter ends there, with the three of them reconvening with George and telling him of their new plan, and all four of them committing to carry it out.

Next: The author stalls for time with an entire chapter of exposition.

#varney the vampire#varney summary#henry bannerworth#george bannerworth#sir francis varney#marchdale#dr. chillingworth

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Varney the Vampire, Chapter 4: Guys I Think It Might Be A Vampire

[Previous chapter] [Next chapter]

Morning dawns, so bright and clear and beautiful you can practically hear the Peer Gynt suite in the background. Henry, who has been casting paranoid looks at the creepy portrait all night, is much relieved. Flora wakes up, and she's still freaked out from last night. Henry, after making a token attempt to comfort her, calls his mom in to deal with her Girl Feelings and leaves to confer with Marchdale.