#garingbal

Text

the botanist

away from brutes

away from this scurvy cork upon the sea

its wake so heavy on the water

like a scar that never heals

& I am barely saved

by water vigils

effervescent verses & furious tides

& the swimming troubadours of the grand azure

even the inanimate anchor

yes

I envy the anchor

baptised everyday

born again in the deepest solitude

once

I dreamt of impossible flowers

another life

a palimpsest under the skin

lost

in the sails

bound by tortured masts

stretched tight across the wind

the chest of an alpha male

dragging us into oblivion

each canvas

bleached in reckitt’s blue

omens of domestic servitude

to whiten the colonial world

a sentence of red earth

speaks across the shore

across the fine bones of coral

a last ochre breath

matrilineal kin

of the

bidjara

ghungalu

garingbal peoples

their precious dialect

an exquisite secret told by leaves

told by the clans of sixty thousand years

& if islands could send warnings

mulgumpin

& its dark dream of tea-tree stained lakes

would dispatch the osprey

prey in the talons of its tarsi

so they may notice something smaller than themselves

& something bigger

& the brevity in between

a ship in the harbour

gravid with exotic disease

its barbarian flag

blood red

corpse blue

& white so blinding

I have a book of sketches

filled with endangered species

©️david sichler

#writerscreed#rejectscorner#spilled ink#alt lit#poets on tumblr#poetry#free verse#twc#writers on tumblr

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

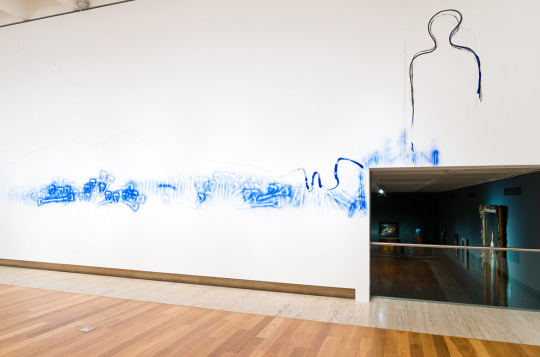

Dale Harding

The Leap/Watershead

2017

ochre on linen

180 x 240cm

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia and Tate

Acquired 2019

Notes: Harding is from the Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal people of central and western Queensland, and the Ghungalu red ochre and the Garingbal light ochre he has used in The Leap/Watershead are drawn from these lands. Harding has blown the ochres onto the linen canvas, adopting a painting technique used in the rock art galleries in the sandstone escarpments of Carnarvon Gorge, in central Queensland. Harding has described how the physical effort of using his breath so intensively left him exhausted, and he was unable to complete the task he had set for himself. Upon seeing the angular form that emerged from the haze of pigment, Harding was reminded of the form of Blackdown Tableland – a sandstone plateau of cliffs, gorges and waterfalls that rises from the plains below. The title of the work refers to the life-giving significance of this land, where the headwaters of major central Queensland river systems spring. The double-barrelled title refers to another landform of historical significance; The Leap, a locality in the Mackay region which was the site of a massacre of Aboriginal people in 1867. Fleeing from the rifles of the Queensland Native Police Force, the group leapt to their deaths from the cliff edge of Mount Mandarana.

Source: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

#indigenous art#contemporary art#dale harding#garingbal#bidjara#ghungalu#queensland#ochre#breath#abstract color field#abstraction#painting#rock art#remembrance#land#home#homeland#cliff

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artist Research -

“Wall Composition in Reckitt’s Blue” (2017) saw artist Dale Harding perform an adaptation of a mouth-blown stencil process used traditionally in Carnarvon Gorge rock art of central Queensland, the country of his Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal peoples. Harding replaced the traditional rock ochres for an ultramarine blue pigment made from the popular colonial frontier powdered laundry detergent called “Reckitt’s Blue”. Use of this bright blue pigment to stencil a found shovel handle in an iterative gestural process, shines light upon colonial histories of Indigenous domestic labour that had subordinated generations of Harding’s female ancestors due to racial legislation (QAGOMA, N.D). Further referencing these women in the top right-hand corner of the wall, through three spectral linework outlines representing the artist’s matrilineal line. Gouges into in the wall simulate natural landforms and the river systems that connected Aboriginal people throughout south-east and central Queensland. Harding’s performance casts a wide scope on art production in Australia through culturally activating a wall within the Queensland Art Gallery while attesting to the importance of an arbitrary object to his own recognition of Indigenous cultural protocols in public institutions (Lynch, 2019).

0 notes

Photo

class notes

Dale Harding

Film #1

“what’s the point of doing art if you don’t do it with a connection to your family or your community?”

“Playing” in the studio… what he’d do on a Friday and Saturday nights!

Sets boundaries to look at ‘country’ and history - specifically his family’s history - similar to ideas of whenua - turangawaewae (“a place to stand”)

He considers the literal material of the work - as it relates to history.

Millet = food (these days often bird food… but actually a really good source of protein) > food as a commodity, which Harding compares to the way Aboriginal people were treated as commodities (“human resource”)

Lives of struggle by Aborigianal people - alienation of language, culture and land - Australian law only recognised Aboriginals as “human” (vs fauna) in the 1980s.

What is he celebrating?

The ability to make art about his culture now

Ability to share activity this with his family

The community itself

Belonging to culture, tradition, heritage

Connections with senior artists from the community

land/country - continuing traditional Aboriginal worldviews in the present.

Grandparents: Bidjara/Garingbal & Gundangara.

Bringing both father’s (non-Aboriginal) and mother’s (Aboriginal) sensibilities in use of materials and techniques eg. stencils with paint, embroidery and cross stitch (historically a feminine craft rather than masculine art technique), wood and forestry, millet sacks (unusual material)... gender politics...

How we conceive the spaces we use eg. Harding treats the gallery/studio as PART OF the landscape (rather than an isolated/hermetic space)

Harding works directly onto the walls - something that we can’t alway do… think about why not?!

Film #2

That might need a few watches…

‘Hypervigilant around protocols’ of making works - always stayed away from direct reference to ochre paintings - but this had changed as he learned more and was encouraged by community

Application/repetition of stencils to ‘tell the story of the object’ - how the object moves - rhythm (also appears when we think of kowhaiwhai, wharaiko, etc)

Different views - as ‘anthropological’ or ‘ethnography’ vs ‘art’. Seeing the works in landscape as composed art works.

Rickets Blue “open source” material - references “domestic servitude”

Technique of blowing pigment - either breath brush or spray cans?

Large figure - the image of the grandmother - on a pedestal - the role of holding the stories (and moving the culture forward). Aborginal communities are matrilineal

His need to ‘look into’ composition - using books and photos - how this changes the ‘in country’ quality of the composition.

Continually making shifts in material and technique eg. carving into gypsum (plasterboard) gallery wall - instead of sandstone cliff or cave; rickets blue laundry dye - instead of ochre pigments; stencils of shovel handles - instead of hands

0 notes

Text

notes

Rāpare (8.2)

Reviewing independent - discussion of ‘easy’ ways to get going with your independent work.

Methods

What does artistic methods mean?

How they do research - form concepts -

Their ‘protocols’ and ‘rules’ - eg. person rules for how to approach a piece/project

… are their rules for artists?

Perhaps these are processes?

How artists repeat or ‘iterate’ an idea through a body of work

Choices of MEDIUM (singular) or Media (plural)

Painting: acrylic, oil, watercolour, substrate (canvas, wood, concrete)

Sculpting: hard/soft, additive/subtractive

Why choose a technique?

What is the history of the medium - what is a material or technique tied to from the traditions we have inherited? eg. wood vs marble vs clay vs wax… ; oil paint vs earth pigments vs charcoal vs food….

What is a person’s/artist’s “worldview”?

… their worldview influences their method, eg. their ethical system

Hākari concept in relation to the artist… ?

Food and celebration

process/tradition/rituals

Transitions between tapu and noha, sacred and everyday… life and death?

Dale Harding

Film #1

“what’s the point of doing art if you don’t do it with a connection to your family or your community?”

“Playing” in the studio… what he’d do on a Friday and Saturday nights!

Sets boundaries to look at ‘country’ and history - specifically his family’s history - similar to ideas of whenua - turangawaewae (“a place to stand”)

He considers the literal material of the work - as it relates to history.

Millet = food (these days often bird food… but actually a really good source of protein) > food as a commodity, which Harding compares to the way Aboriginal people were treated as commodities (“human resource”)

Lives of struggle by Aborigianal people - alienation of language, culture and land - Australian law only recognised Aboriginals as “human” (vs fauna) in the 1980s.

What is he celebrating?

The ability to make art about his culture now

Ability to share activity this with his family

The community itself

Belonging to culture, tradition, heritage

Connections with senior artists from the community

land/country - continuing traditional Aboriginal worldviews in the present.

Grandparents: Bidjara/Garingbal & Gundangara.

Bringing both father’s (non-Aboriginal) and mother’s (Aboriginal) sensibilities in use of materials and techniques eg. stencils with paint, embroidery and cross stitch (historically a feminine craft rather than masculine art technique), wood and forestry, millet sacks (unusual material)... gender politics...

How we conceive the spaces we use eg. Harding treats the gallery/studio as PART OF the landscape (rather than an isolated/hermetic space)

Harding works directly onto the walls - something that we can’t alway do… think about why not?!

Film #2

That might need a few watches…

‘Hypervigilant around protocols’ of making works - always stayed away from direct reference to ochre paintings - but this had changed as he learned more and was encouraged by community

Application/repetition of stencils to ‘tell the story of the object’ - how the object moves - rhythm (also appears when we think of kowhaiwhai, wharaiko, etc)

Different views - as ‘anthropological’ or ‘ethnography’ vs ‘art’. Seeing the works in landscape as composed art works.

Rickets Blue “open source” material - references “domestic servitude”

Technique of blowing pigment - either breath brush or spray cans?

Large figure - the image of the grandmother - on a pedestal - the role of holding the stories (and moving the culture forward). Aborginal communities are matrilineal

His need to ‘look into’ composition - using books and photos - how this changes the ‘in country’ quality of the composition.

Continually making shifts in material and technique eg. carving into gypsum (plasterboard) gallery wall - instead of sandstone cliff or cave; rickets blue laundry dye - instead of ochre pigments; stencils of shovel handles - instead of hands

ADD EXTRA STUFF YOU FIND:

Eg. an extra film I found last night - too long to play in class but you might find it interesting:

Colour Theory with Richard Bell - 2013 https://vimeo.com/88723906

📷 project for the Sydney Biennale

📷

http://www.4a.com.au/4a_papers_article/dale-harding-tess-maunder/

📷

Yoko Ono

What do we know about her:

Wife of John Lennon… and she “ruined the Beatles”.. The mythology of Ono.

In bed for peace… a “love in”

Photographed by Annie Leibovitz

Performance artist

Instructional artworks (...sometimes as Conceptual Art)

Works on bodies

Multimedia artist including song writing, video, performance

Peace activist

Japanese & American

Film #1

Very diverse oeuvre

Upper middle class origins - “even their wealth didn’t protect them from WWII” eg. Hiroshima & Nagasaki - halt in the easy movement between USA & Japan (many Japanese were persecuted in the USA during WWII)

Engagement with viewers > viewers become artists within the work > “audience as author” (... Roland Barthes…”Death of the Author”)

Art starts in the gallery but goes beyond it… can exist anywhere

Performance Art

Fluxus (https://www.theartstory.org/movement/fluxus/history-and-concepts/)

Questions of authorship and collaboration

BODIES

unGendering

Bottoms

Feminisation of society

Taking away/ critiquing gender

Gender activist

Work celebrates what already exists… critique of ideas of invention and originality

Work to be light on the earth - physically but also conceptually. Eg. instructions are barely there.

Humour

Playful

Art as invitation > Interactive > Collaboration > art events (“happenings”) > improvisational performance.

Grapefruit > hybridity > Homi Bhabha (https://literariness.org/2016/04/08/homi-bhabhas-concept-of-hybridity/)

Aspirational (climb a ladder to look at a canvas on the ceiling that says “yes”)

Independent:

3 ½ hrs experiments responding to Dale Harding &

3 ½ hrs experiments responding to Yoko Ono

Set yourself up with fixed parameter (things or rules), and just one or two variables eg.

I have this room, this paint, this technique of repetition of this shape, this amount of time; my variable is what rhythms of composition I can create.

I have this story from my mum, I have these household products and these surfaces to put them on; my variable is how I tell the story.

I have my grandma on the other end of the phone telling me stuff which will become a collection of words which I will record; the variable is how I will put them on paper as a text/composition.

I have these flatmates willing to carry out this set of instructions; how will I document that performance?

I am interested in how we play a particular thing (eg. chess or cards or a musical instrument), I have a camera to record it. The variable is which photos I select.

I am interested in play as the unconscious manipulation of clay/fimo/playdough - I will play for 10 minutes at a time and see what comes out. I will repeat this 6 times, I will choose how to document/reflect on the results...

0 notes

Text

A Mother-And-Son Duo Telling Stories Of Central Queensland Through Quilts + Painting

A Mother-And-Son Duo Telling Stories Of Central Queensland Through Quilts + Painting

Art

by Sasha Gattermayr

Dale Harding holding ‘White Hill—looking for food at Clermont’ 2020, by Kate Harding. Photo – Carl Warner.

‘Carnarvon’ 2020 (detail), by Kate Harding. The artist attached miniaturised pityuri bags she made from thread. Photo – Carl Warner.

‘Carnarvon’ 2020 (detail), by Kate Harding. Photo – Carl Warner.

Dale Harding holding ‘Cylinders’ 2020, by Kate Harding. Photo – Carl Warner.

‘Carnarvon underground water’ 2020 (detail), by Kate Harding. Photo – Carl Warner.

‘Carnarvon underground water’ 2020 (detail), by Kate Harding. Photo – Carl Warner.

‘Emetic painting (International Rock Art Red and white)’ 2020, by Dale Harding. Photo – Carl Warner.

Left:Emetic painting 2019–20, by Dale Harding. Right: Dale Harding holdingTribute to women—past, present and future 2019, by Kate Harding. Photo – Carl Warner.

‘What is theirs is ours now (I do not claim to own)’ 2018, by Dale Harding. Photo – Charlie Hillhouse.

In 2019, artist and Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal man Dale Harding made a copy of Sidney Nolan’s painting ‘Landscape Carnarvon Range Queensland’ on his studio wall after paying a visit to the site himself. Kooramindanji (the Carnarvon Gorge) is a site rich with ancient rock paintings, carvings and stencils that Western artists such as Margaret Preston, Mike Parr and Nolan had visited and represented in their work over the twentieth century.

After copying the Nolan painting to his wall, Dale began thinking about the act of temporary access to land, and what it means to be a local. This led him inevitably to ruminate on how much material was borrowed from Indigenous art practices and places to inform the Australian Modernist movement heralded by non-Indigenous artists. These questions that followed formed the basis for Dale’s new exhibition, Through A Lens of Visitation, which is on now at Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA).

Consisting of large-scale paintings by Dale and fabric quilt works by his mother, renowned textile artist Kate Harding, the exhibition pulls together materials and techniques from the pair’s ancestral country to represent details of the land and communities around Carnarvon Gorge and its surrounding plateau, which is part of the Great Diving Range.

Dale’s paintings bring together materials such as ochre pigments, laundry detergent, Chinese ink and gum made from acacia tree sap onto panels made from felted wool, linen or paper, while sculptural pieces made from botanical resin, glass and lead are among his other featured works.

Interspersed among these painted and sculptural works are Kate’s fabric art, which take the form of textile wall hangings. An active custodian of Carnarvon Gorge, Kate has been quilting since the early 80s – drawing on traditional teachings from her Catholic school and by watching her mother and grandmother’s sewing, crocheting and embroidery practices at home.

Generations of women on Kate’s mother’s side were engaged in domestic ‘service’, which adds a layer of settler influence to the craft. When she took up the craft in 2008, Kate began experimenting ways her quilt-making could be divorced from Western conventions. She uses ochre dyes from Country instead of prints to colour her fabrics, and taught herself how to sew miniaturised pityuri bags she had seen at a museum using traditional methods. She then sewed these tiny pouches sporadically into her quilts.

‘These ochre dyed fabrics are understood as exhibiting the colours imbued with the stories of Kate’s ancestral territories,’ says Dale. From all angles, Kate’s quilts represent the relationship between home, Country and art-making.

In the past, Dale’s work has been centred on telling oral histories and describing acts of violence against Australia’s First Nations people. Now, his shifted focus is on finding fresh ways to communicate ancestral knowledge through materials.

‘By making contemporary artworks that can be read by our families and communities on a cultural level, there have been ways of sharing Central Queensland perspectives with audiences around the world,’ says Dale. ‘My interest is to grow familiarity and visual literacy of Central Queensland art forms, in ways that strengthen them into the future for those who live and practice them.’

‘Through A Lens of Visitation‘ is on at Monash University Museum of Art from 28 April – 26 June 2021.

Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA)

900 Dandenong Road

Caulfield East

Ground Floor, Building F

0 notes

Text

Material Place: Reconsidering Australian Landscapes

https://artdesign.unsw.edu.au/unsw-galleries/material-place-reconsidering-australian-landscapesGreat exhibition on at UNSW Galleries at the moment.

Also, wonderful podcast from the IMA involving one of the artists Dale Harding (Bidjara, Garingbal and Ghungalu) in conversation with plant specialist Steve Kemp (Ghungalu).

https://soundcloud.com/instituteofmodernart/in-conversation-dale-harding-and-steve-kemp

0 notes