#friedrich de la Motte Fouqué

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

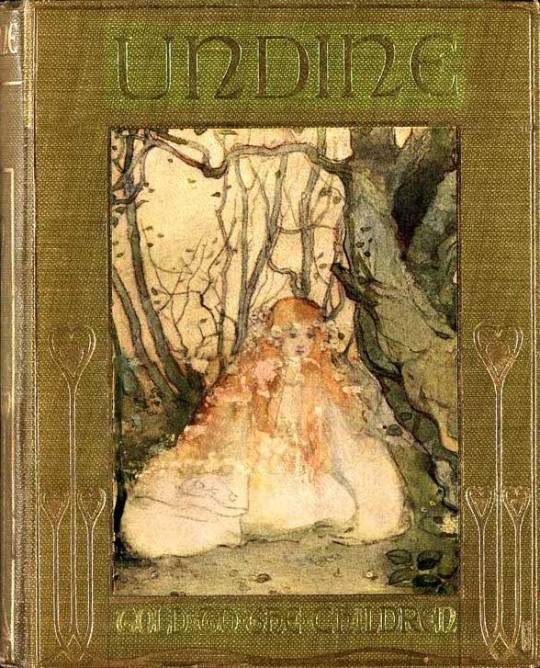

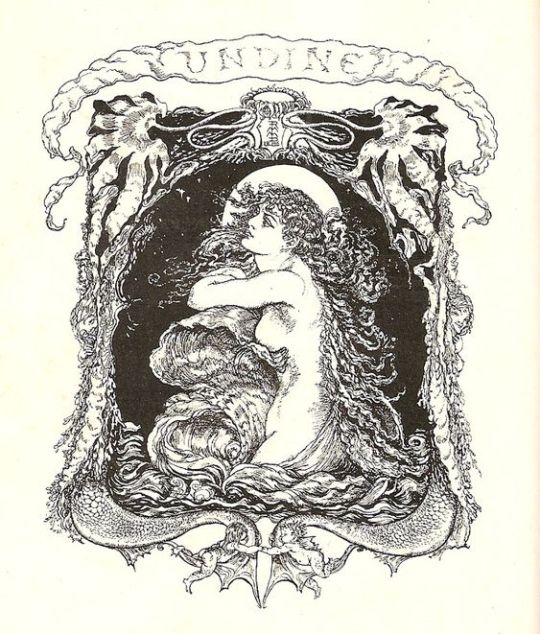

Undine by Arthur Rackham

#undine#art#arthur rackham#illustration#friedrich de la motte fouqué#fairytale#fairy tale#germany#german#water spirit#mythology#mythological#supernatural#soul#medieval#knight#europe#european#romance#paracelsus#esoteric#ondine#fairy tales#folklore#fairy#mermaid#history#romantic

437 notes

·

View notes

Text

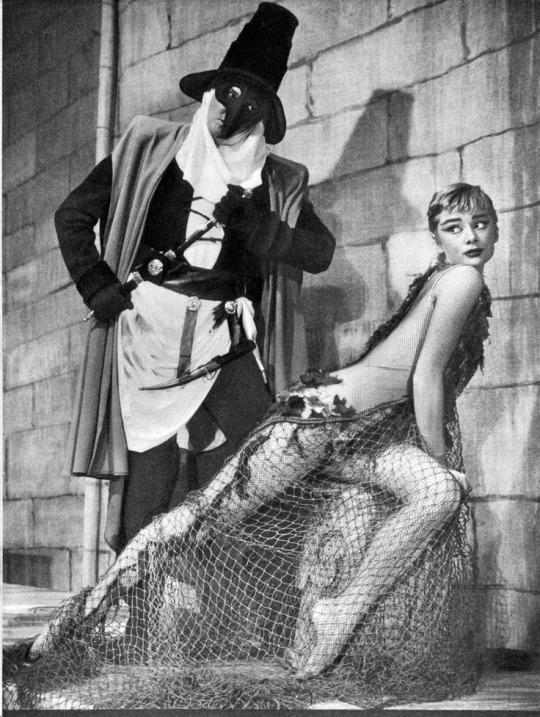

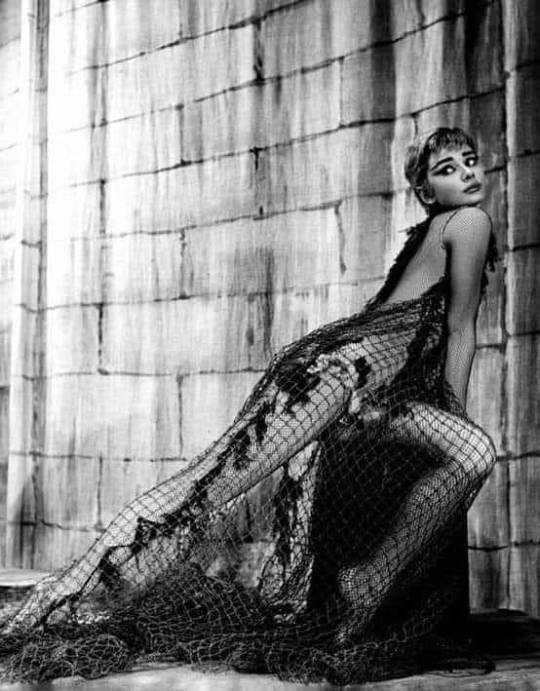

Audrey Hepburn photographed by Milton H. Greene on stage during a performance of “Ondine”, by Philippe Halsman.

New York, 1954.

.

.

#audrey hepburn#hollywood golden age#mel ferrer#ondine 1954#milton h greene#50s#1950s#l'Athénée#50s hollywood#jean giraudoux#friedrich de la motte fouqué#1950s hollywood#hepburn#philippe halsman

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

An illustration by Arthur Rackham for Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué's 1909 publication, Undine

Source: Wikimedia Commons

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Undine 🪸 🌊

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

De nimio a imprescindible #aperturaintelectual #vmrfaintelectual @victormanrf @Victor M. Reyes Ferriz @vicmanrf @victormrferriz Víctor Manuel Reyes Ferriz

#AperturaIntelectual#vmrfaintelectual#4 de marzo de 1877#@vicmanrf#@Victor M. Reyes Ferriz#@victormanrf#@victormrferriz#Alphonse Victor Marius Petipá#ópera “Undina”#Ballet Carmen#Ballet El cascanueces#Ballet El lago de los cisnes#Ballet La bella durmiente#Brujo Rothbart#Cine#Cisne blanco#Cisne negro#Cuento alemán Der geraubte Schleier” (El velo robado)#Cultura#De nimio a imprescindible#Doncella Odette#Fiódorovich Minkus#Friedrich Heinrich Karl de la Motte Barón Fouqué#Hija Odile#Johann Karl August Musäus#Julius Wenzel Reinsinger#Lebedínoye óziero#Lev Ivánovich Ivánov#Opinión#Pensamiento crítico

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

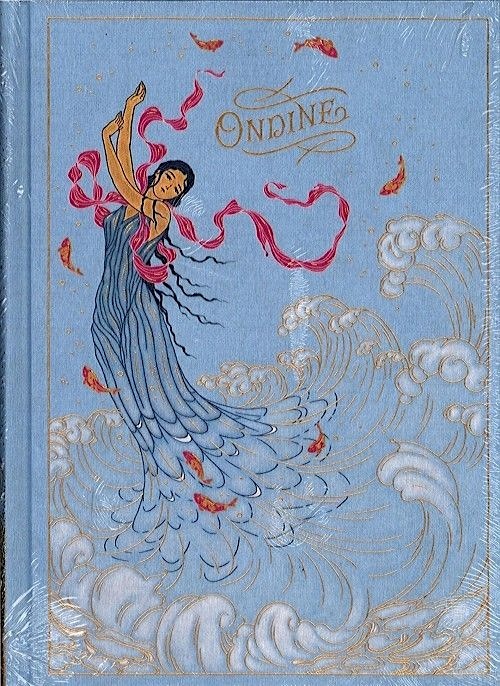

"Ondine" book cover written by Friedrich de La Motte-Fouqué and illustrated by Arthur Rackham (English artist, 1867-1939)

210 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did you just say that regulus black would not read Kafka…. Oh boy

respectfully... i think that recently kafka has become one of the main authors that people who don't actually read books think that "smart" people read. like he's overplayed in popular culture

and that fact would send Terminally Pretentious regulus black into a tailspin!! he always has to make a selection that is just mainstream enough to be inarguably good, but juuust niche & snobby enough that he can be a snooty little prick about it. he is reading Undine (1811) by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué. CRY ME A RIVER!!!!!

#a#I DO REALLY LIKE KAFKA 🙌 <- covering my bases. EVERBODY GO READ THE BURROW 1931. I WROTE A PAPER ABOUT THAT ONE#i just have interacted with enough english department snobs to know that regulus is THE english department snob#and they are not posting tiktoks like “omfg Kafka's Diaries <3” lmfao#he is trading saliva with harold bloom's litcrit on the western canon (derogatory)

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Audrey Hepburn in 'Ondine', a play written in 1938 by French dramatist Jean Giraudoux, based on the 1811 novella 'Undine' by the German Romantic Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué

Photo by Ryan Smith, 1954.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mermaids and Mr Freud...

What do you think when you hear the word “mermaid”? Chances are, you’ll imagine a beautiful girl with a sparkling fish tail, naked breasts, flowing hair, gazing into a mirror: a scene straight out of early 20th-century Golden Age illustrators Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac. Or perhaps you see Ariel, Disney’s 1989 cartoon version of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, with her cherry-red hair and purple shell bikini. That romanticized – and Disneyfied – picture of a mermaid seems fated to endure with this year’s live-action The Little Mermaid film (though the casting of Halle Bailey in the title role has prompted as much racist backlash as it has celebration. The mermaid of Andersen’s 1837 fairytale was white, say the purists.) But Andersen himself drew on a far older, stranger, and more subversive folklore to write his story. His tale of a mermaid who, falling in love with a human prince, is forced to sacrifice her tail and her voice in order to become human, was deeply influenced by Undine, the 1811 novella by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, which in turn was inspired by the 16th-century occultist Paracelsus, who coined the word “undine” to describe an elemental water spirit who can only gain a soul by marrying a human. And mermaid legends, like so many other fairytales, have been shared in many parts of the world for millennia. One of the earliest mermaid stories dates back to sometime around 1000 BC. In Assyrian mythology, the goddess Atargatis, who was venerated for thousands of years all over the Middle East, attains a half-fish, half-human form after throwing herself into a lake. The Yoruba spirit, Yemoja, who is represented as a mermaid, appears under other names as an ocean and river mother goddess – Yemaja, Yemanjá, Yemoyá, Yemayá – across half the world. Mami Wata – a water deity sometimes known as La Sirène - revered in Haiti and many parts of Africa, often appears as a mermaid, with a mirror that allows the passage from one plane of reality to another. And so it goes, from the ningyo of Japanese folklore to the sjókonar of Norse sagas. It is one of the most powerful archetypes in our shared dreaming. Nor were mermaids always understood to be mythological. Throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, European bestiaries and illuminated manuscripts portrayed mermaids as real creatures. On several occasions fishermen have claimed to have caught them in their nets. Early explorers reported mermaid sightings – although it is more likely that they were dolphins, seals or manatees, mistaken for mermaids by sailors expecting to encounter exotic beasts on their journey. Since then, humans have stubbornly continued to look for proof that mermaids are real (so far, without success). What does the mermaid mean? Why is the half-fish half-woman such a potent, enduring legend? At the heart of these stories is the question of women’s power. Fairy tales and folklore have played an important role in challenging societal roles and giving people opportunities to discuss difficult or taboo subjects through the safety of metaphor – in this case, through the image of a woman whose irresistible sexual power over men is balanced by her own inability to function sexually or to reproduce. And in the days when pregnancy and childbirth often proved fatal, that might not have been such a bad thing. The mermaid cannot be raped, or forced to give birth. Not being human, she is not bound by the conventions of human society or the laws of the Church. She enjoys both the freedom and the sensuality of her element without any of the attendant dangers or discomforts. In folklore, the mermaid has independence, and can exercise sexual power over men, which makes her ultimately dangerous, unnatural: a monster. Perhaps this is why so many ancient myths and medieval bestiaries depict mermaids as untrustworthy, deceitful creatures, leading sailors to their doom. Their bodies are all sexual promise, but no sexual reward; and their voices are so enchanting as to drive men to madness. Unable to fulfil what some believe to be a woman’s biological destiny, they are often portrayed as soulless. Because a woman who uses without being used, who seduces without being seduced, who moves through water and air – whereas men are doomed to drown if they venture into the mermaid’s world – is a challenge to God, to the patriarchy, and to order itself. In The Little Mermaid, Andersen tamed this older, more radical tradition. The moralism of his tale serves the dual purpose of mastering the mermaid – of making her fall victim to a human’s charms, rather than the more traditional way around – and taking away her power. The mermaid, made helpless by love of her prince, gives up her native element and the autonomy that comes with it, and exchanges it – via a witch’s spell – for a pair of feet, though walking causes her terrible pain. She also relinquishes the power of speech, which means that she is incapable of expressing her love in any way but the physical. And if her prince falls in love with someone else, then the mermaid is doomed to die on the instant, and to forfeit the soul for which she has sacrificed everything. Her entire being – her very existence – becomes dependent on the love and approval of her prince. Her independence, her challenge to the patriarchal status quo is gone. Though the ending of Andersen’s tale is – to a certain degree – redemptive (the mermaid, refusing to take the life of her prince in order to save her own life, is borne aloft by spirits of air and promised an eternal soul), it seems very cruel, especially as the heroine is only fifteen years old. A contemporary reader might well see in Andersen’s telling a warning to an emerging women’s movement – women’s power has often been seen as fragile, unnatural, and at the mercy of emotion. Unlike the tragedy of Andersen’s mermaid and prince (and of Fouqué’s Undine), the 1989 Disney film rewards Ariel and Eric with a happily-ever-after ending. And it tells their story in a cheery, colourful palette (a stark contrast to Kay Nielsen’s original dark, eerie concept drawings for the film), which while being pleasingly child-friendly, also reduces the mermaid’s essential alienness, and minimizes her sacrifice, thereby making her tale into little more than a love story with a little added jeopardy.

But Disney also perpetuated other tropes. It is meaningful that the sea witch who provides the mermaid with the spell fits the older-woman archetype well represented in fairy tales: embittered by age, envious of the little mermaid’s youth and beauty. She is the one who demands the mermaid’s voice as payment for her services: a potent image of an older generation, silencing the voices of youth. (In Andersen’s telling, she too is the one who demands that the mermaid’s sisters cut off their hair in order to save their sibling.) The older woman is filled with rage and contempt for the younger woman; taking pleasure in their humiliation and the loss of their power. And as the tentacled Ursula in the Disney version, she is especially monstrous.

Over the centuries, fairy stories have always been reinvented to serve the needs of the changing times. And people have often fretted about this. (In 1853, Charles Dickens criticised the trend for rewriting fairytales to fit didactic, contemporary concerns.) But perhaps that the meaning of the mermaid has drifted further and further away from its origins in ancient folklore should not be cause for too much concern. Today, the mermaid has become the symbol of the trans community, whose members often feel the generational divide especially keenly. And there are endlessly imaginative ways to retell the tradition. (In 2008’s Ponyo, Hayao Miyazaki spins his tale of a goldfish who longs to be human into a charming meditation on childhood.)

Like the ever-evolving traditions of fairytales, magic, too, is transformative. In stories, magic acts as a metaphor for the change we seek to effect in our lives, in ourselves, in the world around us. Perhaps that is why fairy tales resonate so deeply with us. Why else would we cling to them, retell them in so many ways? They teach us not that magic exists, but that change is possible. They teach us not that dragons exist, but that monsters can be overcome. And they teach us to hope, in the face of a world that seems to be getting harsher and more confusing by the day, that sometimes love can save us, and that, even in the face of the cruellest kind of tyranny, we can still keep control of our fate, and hope for a happy ending –not just a Disney wedding, but something perhaps more satisfying. In films like Moana - or more recently Ruby Gillman, Teenage Kraken – the love story is with the sea; a story of claiming, rather than giving up power. Mermaids – in all their aspects – are still working their magic on us. And now, perhaps more than ever, it’s time to listen to their song.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Be a Real Life Mermaid 🌊🧜♀️🐚

The Look

🐚 Wear sea foam green, aquamarine, teal, ocean blue, soft grey, lilac, periwinkle, emerald, pale gold, white, deep blue, and turquoise

🐚 Pick flowy fabrics such as taffeta, chiffon, linen, silk, muslin, and sequined fabrics that resemble fish scales

🐚 Choose garments like maxi dresses, flowy skirts, bandeau off-the-shoulder tops, tank tops, soft scarves used as tops, shell clutches, woven bags, and pretty beaded sandals

🐚 Accessorise with jewellery made from pearls, sea glass, seashells, turquoise, aquamarine, opals, gold that resembles the sun glinting on the sea, and silver that reminds one of the metallic sheen of fish scales. Examples of accessories you can wear are bangles, anklets, layered necklaces, and pearl earrings

🐚 Makeup Ideas: eyeshadow in nudes like a sandy beach, greens and blues like the sea, or lavender and pink like a coral reef, shimmery highlight, dewy skin, coral pink lipstick, and seashell pink lipgloss

🐚 Hair Ideas: loose curls that look like ocean waves, fishtail plaits, green and blue hair dye, pearl hairclips, and sea salt hairspray. Brush your hair with a pretty wide-tooth comb.

The Lifestyle

🐚 Listen to songs such as Martha's Harbour by All About Eve, No Ordinary Love by Sade, Come Into the Water by Mitski, Pearl Diver by Mitski, Mariners Apartment Complex by Lana Del Rey, and Call of the Sea by Claudie Mackula (a longer mermaid playlist is here).

🐚 You can also listen to the sounds of the ocean, like whale song or waves crashing on the beach

🐚 Watch movies and TV shows such as Aquamarine, Splash, The Little Mermaid, H20: Just Add Water, Mr Peabody and the Mermaid, Miranda (1948), Mermaid Melody Pitchi Pitchi, Ponyo, Barbie in a Mermaid Tale, Barbie: The Pearl Princess, Neptune's Daughter (1914), A Daughter of the Gods (1916), Queen of the Sea (1918), Venus of the South Seas (1924), and Magic Island (1995)

🐚 Read books, fairytales, and poems such as The Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Andersen, The Mermaid Handbook by Carolyn Turgeon, Mermaids: The Myths, Legends, and Lore by Skye Alexander, A Daughter of the Sea by Amy Le Feuvre, Undine by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, The Mermaid by Alfred Lord Tennyson, and The Sea-Child by Katherine Mansfield

🐚 Mermaids are renowned for their beautiful siren song, so sing sweetly and brightly as often as you feel like it

🐚 Make your self smell like the ocean by using a deodorant like Old Spice Deep Sea, and perfumes like L by Lolita Lempicka, Acqua di Gioia, Salt Air by Skylar, Fleur de Corail by Lolita Lempicka, Seahorse by Zoologist, Nymphéas by Kismet Olfactive, Salina by Laborattorio Olfattivo, Alien Mirage by Mugler, Very Sexy Sea by Victoria's Secret, 20,000 Flowers Under the Sea by Tokyomilk, Nebbia Spessa by Filippo Sorcinelli, Tiziana Terenzi's Sea Stars Collection, Chant d'Extase by Nina Ricci, Sirena by Floris, Squid by Zoologist, and Orto Parisi Megamare (be aware that the latter two suit a dark siren who lures men to their deaths more than a sweet mermaid princess).

🐚 Make your home smell like the deep sea too, with sea salt scented diffusers and candles such as Yankee Candle Sea Minerals, Yankee Candle Seaside Woods, or Jo Malone Wood Sage and Sea Salt

🐚 Home Decor Ideas: silk sheets in blue, grey, and sea green, seashell jewellery trays, homemade terrariums, jellyfish embroidery, seashell candles, beaded curtains made from string and shells, paintings of maritime scenes, glass vases filled with layers of sand, seashells, and faux pearls, seashell shaped soap dishes, rattan furniture, woven baskets, treasure chests to keep your valuables in, mermaid figurines, a seashell or jellyfish mobile, a bowl filled with seashells, a glass bottle filled with ocean water or with a love letter inside to replicate a message in a bottle, mosaics with marine motifs like seahorses and shells, even an aquarium with colourful fish if you are able to care for them

🐚 Spend lots of time around near bodies of water, swimming in it to connect with your inner mermaid, or just walking in it and feeling the sand beneath your feet

🐚 Collect seashells and pretty pieces of sea glass thar wash up on the shore

🐚 Watch synchronised swimming, or even learn it yourself

🐚 Go diving, snorkeling, or mermaiding

🐚 Visit aquariums to see beautiful exotic fish and learn more about the ocean

🐚 Do your best to be sustainable; make the world a cleaner place for your fishy friends to live in. If possible, attend a beach clean-up group local to your area to help pick up litter

🐚 Carry a haircomb and hand mirror with you at all times (you can hotglue seashells and faux pearls on the back of the mirror to make it even more like a mermaid's treasure)

🐚 Watch documentaries and read books on the ocean, marine life, and nautical myths and legends

🐚 Enjoy snacking on seaweed soup, coconut water, and Guylian seashell chocolates

🐚 Take luxurious baths with dead sea salt, seaweed masks, small white bath bombs that resemble pearls, a coconut scented candle, and calming music

#mermaidcore#life aesthetic#mermaid aesthetic#femininity#hyperfeminine#hyperfemininity#that girl#that girl aesthetic#princesscore#royalcore#elegantcore#fairycore#cottage#oceancore

88 notes

·

View notes

Note

As a fairytale for this summer, I recommend "Undine", the story that inspired Andersen's "The Little Mermaid". It's a less-known fairytale written by a less-known author, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, who was actually a German baron

It's about a water spirit who marries a human in order to gain a soul of their own, but that's all I'm gonna share so you can read the rest

Sounds neat! I'll have to check it out :D

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andersens "Kleine Seejungfrau" ist an einer langen Tradition von Wasserfrauen angelegt, die lang ins Mittelalter führt. Von ihnen ist die kleine Meerjungfrau die erste, die sich weigert, den Menschen, der ihr Herz zerbrach, zu töten, und damit von dieser Tradition abbricht. Darum hab ich mir diese Szene ausgedacht, wo die älteren Nixen versuchen die Jüngste zu überzeugen, auch ihren Prinzen zu töten. Hier eine kleine Verdeutlichung:

Links: Melusine, die Wasserfee. Ihr Sagenstoff ist bis ins 12. Jahrhundert verwurzelt und schon im 13. wurde er mit der Adelsfamilie der Lusignans in Verbindung gebracht. Melusine heiratete Raymund unter der Bedingung, er dürfe sie nie Samstags beim Baden zusehen. Natürlich konnte der Ritter der Neugier nicht widerstehen und als er seine Frau mit einem Schlangenleib sah, flog diese davon und nahm Großteil des Glücks, das sie ihm geschenkt hatte, zurück.

Rechts: die Meerfei aus Egenolf von Staufenbergs Rittermäre. Wie viele mittelalterliche Patenfeen beschützte sie den Ritter Peter Diemringer auf dem Schlachtfeld. Sie verliebte sich und nahm eine heimliche Ehe mit ihm auf, doch er ließ sich vom Kaiser überzeugen und verließ den Wassergeist für die königliche Muhme. Zur Hochzeit stieß die Meerfei ihren Fuß durch die Decke und sagte ihm seinen Tod vor. In vielen Verdichtungen wird auch sie Melusine genannt.

Oben: Undine aus Friedrich de la Motte Foucqués Erzählung. Name und Handlung stammen aus Paracelsus Buch um Elementargeistern, die auch sein Kommentar auf die Staufenberger Sage enthält. Undine ist die Nixe, die der kleinen Meerjungfrau am ähnlichsten ist und auch sie hätte ihren geliebten nicht umgebracht, wenn ihre Familie sie nicht dazu gezwungen hätte. Benjamin Lacombes Illustrationen davon sind unheimlich schön.

Andersen's "little Seamaid" is radicated in a long tradition of heartbroken waterwomen, that goes back to the Middle Ages. Of them the little mermaid is the first who refuses to kill the human that broke her heart, thus splitting from that tradition. That's how I came up with this idea, of the older nixies trying to convince the youngest to follow their example and kill her prince as well. Here some more info on them:

Left: Melusine, the water fairy. Her legend stems from the 12th century and was already connected to the family of Lusignan by the 13th. Melusine married Raymund under the condition, that he would never see her bathe on a saturday. Naturally he couldn't resist his curiosity, and thus saw her exposed snakebody, which made her fly away, taking with her all the luck she had gifted him.

Right: the Merfey, from Egenolf von Stauffenberg's chivalric poem. Like many medieval fairy godmothers, her job was to aid the knight Peter Dimringer in battle, yet she fell in love with him and married in secret. However the knight was convinced by the emperor to reject the water sprite and remarry the royal aunt/cousin. The Merfey burst with her foot through the ceiling at the wedding, and foretold Peter his death in three days. In many adaptations her name is given as Melusine.

Up: Undine, from Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué's novella. Name and plot are taken from Paracelsus book on elementals, which also contained his commentary on the legend of Stauffenberg. Undine is the closest related to the little mermaid, and she too would have refused to kill her love, hadn't her family forced her to. I was inspired here by Benjamin Lacombe's wonderful illustrations.

"La Sirenetta" di Andersen va a pescare da una lunga tradizione di tragiche donne acquatiche, che ha le sue radici nel medioevo. Tra queste, la giovane sirena è la prima a rifiutarsi di uccidere l'uomo che le spezzò il cuore, rompendo così con la tradizione. Da qui mi è venuta l'idea per questa scena, dove le sirene più antiche cercano di convincere anche la più giovane ad ammazzare il suo principe. Ecco un po' di informazioni:

A sinistra: Melusina, la fata delle acque. La sua leggenda nasce nel XII secolo e già nel XIII fu ricondotta alla nobile famiglia di Lusignan. Melusina sposò Raimondo, a condizione che lui non la vedesse mai fatsi il bagno di sabato. Ovviamente lui non resisté alla curiosità e quando vide la moglie col corpo di serpente, lei scappò, portando via con se la fortuna che gli aveva donato.

A destra: la Fata Marina, dal poema cavalleresco di Egenolf von Staufenberg. Come molte fate madrine medievali, era incaricata di guidare e proteggere un cavaliere, Peter Dimringer, in battaglia. Ma si innamorò del mortale e lo sposò segretamente. Furono felici finché l'imperatore non convinse il cavaliere a lasciare lo spririto delle acque per sposare la zia/cugina di famiglia reale. La Fata Marina sfondò il soffitto della sala col piede al matrimonio e predisse allo sposo la morte entro tre giorni. In molte versioni della storia viene chiamata anche lei Melusina

In alto: Ondina, dalla fiaba d'autore di Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué. Nome e trama sono tratti dal libro di Paracelso sugli spiriti elementari, nel quale è anche contenuto un commento alla leggenda di Staufenberg. Ondina è la ninfa più simile alla sirenetta di Andersen, e infatti anche lei non avrebbe ucciso il suo amore, se la sua famiglia non l'avesse obbligata

#mermay#the little mermaid#art#digital art#mermaid#nixe#merfey#melusine#undine#legend#fairytales#fairy tales#folklore#folk tales#Meerfey#Meerfee#ondine#Sirene#la sirenetta#Die kleine Meerjungfrau#nixie#fairy#old art#my art#my artwork#digital drawing#digital illustration#Fee#mermay 2022

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

An illustration by Arthur Rackham for Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué's 1909 publication, Undine

Source: Wikimedia Commons

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Reviews #7 - Undine by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué

Undine is a novella from 1811 that tells the story of a water spirit who marries a knight, Huldbrand, to gain a soul. It's filled with poetic descriptions and a magical atmosphere. The plot is basically about marital affairs: one knight falls in love with a girl, then misses his previous girl, making one sad and then the other. It's more style than substance, really.

Narratively, it's fine—you have to take it seriously to feel the pain of the broken hearts and misery, but if we're being more cynical, it's just a story about a guy being terribly indecisive. Where the novella really shines is in its poetic descriptions and magical atmosphere. It feels like an epic poem in prose form. The two main girls are imperfect, and the characters aren’t exactly lovable, but the story blends fantasy in such a beautiful way that it makes me breathe in deeply. The idea of Undines is beautiful, and the mix of banal events with surreal storytelling makes it an immersive, charming read—kind of like Dracula, but with romance instead of terror.

6/10

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

In light of the "Little Mermaid" remake: do you think The Little Mermaid may be inspired by the Greek myth of Glaucus and Scylla? Both stories are about a merperson seeking a witch's help to win the heart of someone who can live on land.

Maybe. I've never seen that myth cited as one of Andersen's inspirations, but I wouldn't be surprised if he thought of it.

All I know is that the direct inspiration was Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué's novella Undine. Andersen didn't care for the fact that Undine gains a soul by marrying a human, so he wrote his own tale where a mermaid tries but fails to gain a soul that way, only to gain it through her own goodness and selflessness instead. But Undine doesn't include the detail of seeking a witch's help, so maybe that element did come from the Greek myth.

I should do more research about Andersen's inspiration for that story, and for his other works too,

#the little mermaid#hans christian andersen#greek mythology#glaucus and scylla#undine#friedrich de la motte fouque

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illustration by Rose M. M. Pitman. De La Motte-Fouqué, Friedrich (1897). Undine.

9 notes

·

View notes