#fannie sellins

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

FANNIE SELLINS // UNION ORGANISER

“She was an American union organizer. After her husband’s death she worked in a garment factory to support her four children. She helped to organize Local # 67 of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union in St. Louis, where she became a negotiator for 400 women locked out of a garment factory. In 1913, she moved to begin work for the mine workers union in West Virginia. Her work, she wrote, was to distribute "clothing and food to starving women and babies, to assist poverty stricken mothers and bring children into the world, and to minister to the sick and close the eyes of the dying." She was arrested once in Colliers, West Virginia for defying an anti-union injunction. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson intervened for her release. Sellins had promised to obey the judge's order against picketing. She returned to Colliers from Fairmont, W.Va. and immediately broke her promise by challenging U.S. District Court Judge Alston G. Dayton to arrest her. He did .With the help of U.S. Congressman Matthew M. Neely, the UMWA waged a public relations campaign to obtain a presidential pardon for Sellins. The union printed thousands of postcards with a photo of Sellins sitting behind the bars of her jail cell in Fairmont. On the back side of the card was the address of the White House. When sheriff’s deputies and Coal and Iron Police were beating Joseph Starzeleski, Sellins intervened and was shot and killed. Deputies then used a cudgel to fracture her skull. A coroner's jury in 1919 ruled her death justifiable homicide and blamed Sellins for starting the riot which led to her death although other witnesses portrayed a different event than the deputies at the scene. The Union and her family hired a lawyer, and got three deputies indicted. The actual gunmen never actually appeared for his trial and was never seen again.”

0 notes

Text

Fannie Sellins

https://www.unadonnalgiorno.it/fannie-sellins/

Mi accusano di aver portato scarpe ai bambini di Colliers. Quando penso ai loro piedi scalzi, blu a causa del freddo pungente dell’inverno, sono ancora più convinta del fatto che, se è sbagliato aiutare quei bambini, continuerò a commettere un reato finché avrò mani o piedi per strisciare sino a lì.

Fannie Sellins, sindacalista statunitense, brutalmente uccisa nel 1919 durante uno sciopero di minatori.

Ha vissuto a cavallo tra Ottocento e Novecento, in un’epoca in cui uomini, donne e anche bambini, erano costretti a lavorare in condizioni inumane per sopravvivere. Non ha mai avuto paura di schierarsi e stare dalla parte degli ultimi, degli emarginati, dei miserabili, nonostante il carcere, nonostante le minacce, fino all’ultimo istante della sua vita, quando è stata ammazzata per aver difeso un minatore da un pestaggio della polizia.

Nata col nome di Frances Mooney a New Orleans nel 1867, si era trasferita a St. Louis col marito, Charles Sellins.

Rimasta vedova molto giovane ha dovuto lavorare duramente per provvedere ai quattro figli e figlie. Era operaia in una fabbrica di abbigliamento quando, i soprusi vissuti sulla propria pelle e l’alto senso di giustizia e equità, le ha fatto partecipare all’organizzazione del primo sindacato delle lavoratrici tessili negoziando per conto di 400 operaie. Nel 1913 venne chiamata a collaborare con gli United Mine Workers, nel West Virginia. Col suo fervore è riuscita a reclutare un numero ingente di minatori di diverse etnie.

Ha guidato importanti scioperi prodigandosi sempre per fornire assistenza a chi era in difficoltà. Aiutava le donne sole, le famiglie indigenti, dava cibo agli orfani, organizzava raccolte di cibo, abiti, medicine e coperte da distribuire a chi ne aveva bisogno.

Arrestata durante uno sciopero a Colliers, per sostenerla il sindacato organizzò un’ampia campagna per ottenere la grazia presidenziale.

Dopo aver ricevuto migliaia di cartoline che la raffiguravano dietro alle sbarre, il presidente degli Stati Uniti, Woodrow Wilson, si mosse per il suo rilascio.

In tutta la sua intensa attività ha continuato a ignorare i decreti ingiuntivi ed è rimasta in prima linea a picchettare e aiutare.

Nel 1919 venne assegnata al distretto di Allegheny River Valley, una regione piena di miniere e impianti siderurgici, chiamata la “valle nera”, per la violenza con cui le autorità reprimevano qualsiasi tentativo di emancipazione sociale. In poco tempo è riuscita a guadagnarsi la fiducia dei lavoratori e a organizzare diversi picchetti.

Il 26 agosto 1919, durante un’agitazione dei lavoratori delle miniere, una dozzina di uomini dello sceriffo, insieme ad un gruppo di guardie, avevano attaccato con una violenza inaudita.

Fannie Sellins si era lanciata verso i picchiatori cercando di proteggere un lavoratore in fin di vita e alcuni bambini, figli di scioperanti.

Riconoscendola, le guardie le diedero la caccia e, dopo averla atterrata con una mazza, le spappolarono il cranio e le spararono alla testa e alla schiena. Non contenti si fecero beffe del cadavere per intimorire gli astanti.Ai suoi funerali ha partecipato una folla di 10.000 persone per renderle omaggio.

Per il suo omicidio, una giuria della Pennsylvania decretò che l’unica colpevole era la vittima e gli assassini vennero assolti.

Nel 1920, gli United Mine Workers le hanno eretto un monumento commemorativo.

La storia del suo coraggio, altruismo e della brutale morte che le è stata riservata, deve continuare a essere raccontata per ricordare il suo importante ruolo nella lotta per i diritti di lavoratori e lavoratrici.

0 notes

Photo

On this day, 26 August 1919, former garment worker Fannie Sellins who became an organiser with the United Mine Workers of America was murdered by company thugs and sheriff's deputies during a coal strike in Pennsylvania. She attempted to intervene when a miner was being beaten, and was shot and killed. Her killers were never punished. Episode 7 of our podcast is about miners' struggles in the US at this time, check it out here: https://workingclasshistory.com/2018/06/09/wch-e7-the-west-virginia-mine-wars-1902-1922/ Pictured: Sellins during a previous arrest https://www.facebook.com/workingclasshistory/photos/a.296224173896073/1196896753828806/?type=3

149 notes

·

View notes

Note

Jonathan/Tommy, adjusting a neck tie :3

I don’t think your intention was to order some pining but here you are :D (also I cheated a little. It’s a bow tie, not a neck tie. But hey, still works :P)

_______

“I can’t believe you’ve talked me into this.”

“And I can’t believe you haven’t gone to formal hall once since the start of term!”

It’s hard to stare pointedly at Jon while they’re both walking rather briskly down the corridor, but Tommy makes a valiant attempt. Jon brushes it off easily.

“It’s just dinner, old chap. The only difference is that you get to wear subfusc and black tie and have dishes served to you. Oh, and there’s an after-dinner speech by someone the fellows will have invited and Wicker dared T. J. to throw a bread roll at Cherry when no-one’s looking.”

“Not really the best sellin’ point, mate.”

“Five shillings he gets cold feet?”

“Jon, I’m sacrificing an entire week’s worth of pints at the Oxford Arms to pay for one bloody dinner – do you really think I have five shillings to spare for a bet?”

Jon’s face falls, but to Tommy’s relief he doesn’t offer to cover expenses. He could, Tommy knows that, and he has in fact offered a few times before; but it’s a matter of pride. Besides, the fact that Tommy can’t afford to even be there without an income is getting him enough snide looks or open hostility. No need to make it worse by having to accept someone’s charity, even his best mate’s.

Still, formal hall is part of life at Oxford, Tommy supposes. And it’s an occasion to get his second-hand dinner jacket and bow tie out of mothballs. At least it’s clean and crisply pressed. Never let it be said that the son of Máire Ferguson walked around with clothes that are anything less than immaculate, even if they aren’t new.

Even though Tommy privately thinks the subfusc is a little ridiculous. And he’s fairly sure his bow tie is crooked.

“How do I look?” he asks Jon in the tone gladiators must have used before entering the Coliseum. Jon squints at him, then grins.

“As silly an arse as anyone here, I expect, including yours truly. Oh, hang on.”

He plants himself in front of Tommy, very close, and his fingers fly to Tommy’s bow tie. For just a second he looks serious, eyebrows knitted in concentration, and something tightens inside Tommy’s chest.

Tommy lets his gaze stray to Jon’s nose, his long lashes, his narrow mouth, and then has to wrench it past Jon’s face and into the distance. It’s been a while since the last time he felt his heart beat in that specific rhythm, the very, very rare cadence that draws him towards someone as though to a magnet.

Stop that, he thinks sternly, you’re being ridiculous. Jon is a friend, for God’s sake, and a good one at that. They share books, they share pints, and they even share a bed on occasion when Tommy is too drunk or tired to crawl up the stairs to his own room. He’s not going to throw all that away for a bow tie.

Jon’s hands fall and he steps back, looking satisfied, like he hasn’t noticed anything amiss. Tommy lets himself smile.

“You don’t actually look silly, you know.” The words leave his mouth before his brain catches up. When it does he amends with a grin, “No more than anyone else, at least.”

It’s the truth. Absurd subfusc aside, Jon looks like Jon always does when he makes an effort: five feet ten of carelessly aristocratic poise, with a smirk lingering in his almost slanted blue eyes and a well-cut suit that mostly makes up for how lanky he is.

His own bow tie is impeccable. Tommy can’t help but regret that fact a little.

Jon appears a little taken aback, but his grin resurfaces quickly.

“Why, thank you for the compliment, old chap. Now,” he says, taking Tommy’s arm and steering him towards the doors to the Dining Hall, “let’s get to the feast or all the good seats will be taken, and I am not sitting next to Fanny. Have you seen him eat?”

Charles ‘Fanny’ Featherstonehaugh’s shirts tend to look like an impressionist painting after a meal. Sitting too close to him is running the risk of being a collateral victim. Besides, Tommy thinks as he follows Jon into the sea of black fabric lit up only by white shirts and the lamps on the long tables, it’ll be interesting to see if T. J. Plaskitt really does throw a bread roll at Cherry-Reaney, at the risk of getting it in the neck if caught in the act.

The day Tommy takes that kind of risk, it won’t be for the sake of throwing a bread roll at a classmate, that’s for sure.

_____________

Good thing Jonathan ended up taking that risk, huh :3

Subfusc (from the Latin subfuscus, “moderately dark”) is a gown, a kind of cross between a sleeveless jacket and a shawl. Oxford undergraduates’ version is short (it barely covers a suit jacket) and apparently colloquially known as an “arse-freezer” :P It’s worn over a suit, black or white tie, at occasions like formal hall or matriculating.

#thatsoneginger#ask reply#fanfiction#my stuff#mon OT3 à moi#minus one#Tom Ferguson#Jonathan Carnahan

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fannie Sellins was an American union organizer who on Aug 26 1919 witnessed guards beating Joseph Starzeleski, a picketing miner. When she tried to stop it, deputies shot and killed her with four bullets https://t.co/fBKfOh49DG https://t.co/OO3v924Epz http://twitter.com/ThisDayInWWI/status/1166007756995743746

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

It Seems Like Nothing Changes

Paul Cussen

August 1919

“A training camp for officers was held in Glandore in August, 1919. This camp was attended by the officers of the Barryroe Company. As far as I can recollect the camp was raided by enemy forces of Military and R.I.C. and had to be disbanded.”

- Lawrence Sexton, Courtmacsherry

Volunteer Michael Fitzgerald (a mechanic and mill worker as well as an active member of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union) having served three months for being part of the capture of Araglen RIC Barracks on Easter Sunday 1919, takes a leading part in the disarming of British soldiers at the Wesleyan Methodist chapel in Fermoy.

“It seems to me that England is gaily riding to ruin, unless there is some wonderful secret policy somewhere. I can’t see where it will all end. The futility and brainlessness of all leaders in every camp. With the exception of a few clever ‘doctrinaire’ socialist people who can state a case — they seem to be devoid even of common sense. The only way for an unorganised majority is to rush them in to doing things and to tell them what to do. Everybody seems to be splitting hairs about ‘direct action’ and other phrases, while one bit of liberty after another is taken from them. Lloyd George puts off and throws sops to Cerberus and every clique in England follows suit. They would sell their own souls for a few pence.”

- Countess Markievicz in a letter from Cork Jail, 14 August 1919

Earlier she had written "I have a lovely view over the River Lee, a garden full of pinks, constant meals sent in by local friends, and at night the most beautiful moths fluttering against the bars." And writing about the support she got from local ladies in the Cumann na mBan she said, ''I got lovely roses and such heaps of strawberries and cream too. Friends are so good to me. If you want to be really appreciated in Ireland, go to jail!"

The Irish Victory Fund appeal, which had started in February at the Irish Race Convention, raised just over $1,005,080 within six months.

James Joyce begins to write “Circe” and begins to copy “Cyclops” while a production of Exiles is mounted at the Munich Schauspielhaus and quickly closes due to harsh criticism.

The mayor of Liverpool enlists 700 troops from the local garrison to combat mass looting when the police go on strike.

“Dock rats reeling like ships in a storm from drunken spite within them, and brandishing a weaponry of axes, sticks and crowbars ... a pack of wild women, hair streaming over shawled shoulders, ready to back them with their talons, grasping bricks and broken bottles ... rodents, bloody rodents every one of them.” - opinion of looters by demobbed soldier employed on police force during strike

President Wilson at a parade to honour his return from the Paris Peace Conference

Józef Piłsudski fails to overthrow the existing Lithuanian government of Prime Minister Mykolas Sleževičius, and install a pro-Polish cabinet. One hundred and seventeen people are arrested and six receive life sentences.

1 August

Dave Creedon is born near Blackpool (d. 2007)

Stanley Middleton is born in Bulwell, Nottinghamshire (d. 2009)

2 August

14-17 people die in the Verona Caproni Ca.48 crash, Italy’s first aviation disaster.

3 August

Joyce writes to John Quinn that it takes him "four or five months to write a chapter" of Ulysses.

4 August

Sgt. Daniel Hayes dies of chronic bronchitis at the Central Military Hospital.

Constable Michael Murphy and Sergeant John O’Riordan are fatally shot while on patrol at Ballyvraneen, between Ennistymon and Inagh in County Clare.

The Rodin Museum opens in Paris in the Hotel Biron. It contains works by the sculptor which have been left to the state.

Béla Kun flees to Vienna after the Hungarian Soviet Republic is overthrown by the Romanian Army.

5 August

The RIC seize a letter from Michael Collins, Minister for Finance, Dáil Éireann, 6 Harcourt Street Dublin, to Terence Mac Swiney, T.D., Corcaigh Meadh (Mid Cork), regarding the arrangement for a meeting by each T.D. with the most prominent supporters of Sinn Fein in their Constituencies, with a view to forming a central committee for the entire constituency and certain local committees and the advancement of the Dáil Éireann Loan and requests ‘your loyal co-operation’.

6 August

The Denver Jewish Times reports on $5,000 donated to the Irish Victory Fund by Samuel Untermyer. This resulted in a high level of publicity in the Fund and the Irish Cause.

7 August

Charles Godefroy flies his Nieuport fighter under the arches of the Arc de Triomphe.

8 August

The Treaty of Rawalpindi is signed between Afganistan and the UK.

9 August

A secret week-long Volunteer training camp begins at Shorecliffe House, Glandore, Co. Cork for 35 battalion and company officers of the Cork No. 3 (West) Cork Brigade. The training officers are from Dublin Brigade and most lectures are given by Leo Henderson.

10 August

The Ukranian army massacres 25 Jews in Podolla. Massive pogroms are to continue until 1921.

11 August

Andrew Carnegie dies of pneumonia in Lenox, Massachusetts (b. 1835)

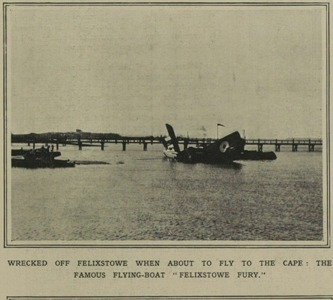

The Felixstowe Fury, while preparing for the 8,000 mile flight to Cape Town, side slips at low altitude and crashes. Wireless operator Lt S.E.S. McLeod drowns and the other six crew members are rescued.

The Green Bay Packers are founded and named after their sponsors, the Indian Packing Company.

12 August

Gearóid O’Sullivan (GHQ), Bernie O’Driscoll (Skibbereen), Seán Murphy (Dunmanway) and Denis O’Brien (Kilbrittain) are arrested at the training camp in Glandore which is surrounded by RIC and British military as some “incriminating documents or notes were found on them”.

http://www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie/reels/bmh/BMH.WS1493.pdf

14 August

Private John Waterfall dies at the Military Hospital from appendicitis/heart attack.

15 August

Benedict Kiely is born in Dromore, County Tyrone (d. 2007)

16 August

The Glandore training camp concludes. Six IRA Volunteers remove a section of track at Farganstown. The next train, however, is not carrying British troops, it is a goods train and it crashes into a nearby field. None of the train’s crew are injured

18 August

“... the hope that an army of military force might cowe the Irish into a frame of mind compatible with the eventual acceptance of some moderate measure of devolution has plainly miscarried”

- London Times

19 August

Afghanistan declares independence from UK.

20 August

Cathal Brugha puts a motion to the Dáil which is seconded by Terence MacSwiney that an Oath of Allegiance should be taken by all members and officials of Dáil Éireann, and all Irish Volunteers. The oath contains the phrase,

I will support and defend the Irish Republic and the Government of the Irish Republic, which is Dail Eireann, against all enemies, foreign and domestic…

22 August

Irish-American, John R. Shillaty is attacked and badly beaten by a mob in broad daylight in Austin, Texas. He is Executive Secretary of the NAACP. He is escorted to the train by the mob and the sheriff

“Your secretary, John R. Shilladay, reached Austin and was received by red blooded white men. As we didn’t need any of his kind (negro-loving white men) we have sent him back home to you. We attend to our own affairs down here, and suggest that you do the same up there” - Deputy Sheriff Gene Barbisch

23 August

15 year old Francis Murphy, a Sinn Féin scout of Glan, County Clare is shot dead by British Soldiers. He dies as a result of bullet wounds received while sitting by the fire reading a book. The inquest into his death concludes that the murder was carried out by the military as revenge for the shooting of Constable Michael Murphy and Sergeant John O’Riordan at Ballyvraneen.

24 August

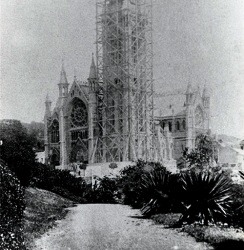

St Colman’s Cathedral, Cobh, is consecrated by the bishop of Cloyne, Robert Browne. In attendance is the primate of all Ireland, Michael Logue, the archbishop of Cashel, John Harty and the archbishop of Tuam, Thomas Gilmartin.

The Munster Final is held in Limerick’s Markets Field with the result:

Limerick 1-6 Cork 3-5

25 August

Volunteers start taking the Oath of Allegiance and using the name Irish Republican Army.

The world’s first daily international passenger air service commences when the British Aircraft Transport and Travel Company fly a deHavilland DH 16 from Hounslow Heath, London to Le Bourget airport, Paris.

26 August

Fannie Sellins (nee Mooney) witnesses guards beating Joseph Starzelski, a picketing miner from the Allegheny Coal and Coke Company, who is killed. When she intervenes, deputies shoot and kill her with four bullets then a deputy uses a cudgel to fracture her skull.

28 August

The amount of the national loan issued reaches £250,000.

30-31 August

The Knoxville, Tennessee race riot begins after Maurice Mays (pictured above) is arrested for the murder of Mrs. Bertie Lindsey. A 5,000 strong mob storm the county jail and free 16 white prisoners. They also attack the African-American business district, where they fight against the district's black business owners, leaving at least seven dead and wounding more than 20 people.

An all-white jury takes 18 minutes to find Mr. Mays guilty of Mrs. Lindsey's death. He dies at age 35 in the electric chair in 1922, declaring his innocence to his dying breath.

31 August

Amrita Pritam is born in Gujranwala, Punjab (d. 2005)

The White Army capture Kiev and the Russian tricolor is placed next to the Ukrainian flag already posted on the Duma.

The Ukranian Army kills 35 Jewish defense group members.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

TODAY'S LABOR HISTORY

TODAY’S LABOR HISTORY

This week’s Labor History Today podcast: Mother Jones and Fannie Sellins. Last week’s show: Scabby The Rat; Smoking at Work; Which Side Are You On? (Encore). August 30Delegates from several East Coast cities meet in convention to form the National Trades’ Union, uniting craft unions to oppose “the most unequal and unjustifiable distribution of the wealth of society in the hands of a few…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

TRANSCRIPT for EPISODE 7

Courtesy of Steph DiBona!

[music]

DYLAN HANWRIGHT: It’s not comfortable, but there’s a little bit of hope on the horizon, of how can we keep ourselves afloat personally, while also having money for the van, the trailer, the gear. Just striking that balance is really, uh, is a tough thing.

MIKE MOSCHETTO: What’s the old saying? If it wasn’t for a mic check I wouldn’t have a check at all? I’m Mike Moschetto, and this is Sellin’ Out.

[music: “I’m a casino that pays nothing when you win / Please put your money in”]

MIKE: Hey! Thanks for listening to Sellin’ Out. Proud to be the #1 rated podcast named “Sellin’ Out” that I am personally aware of at the present time. If you’re listening for the first time, welcome, thank you. I’m mike Moschetto. But if you’ve been along for the ride up through this point, it’s probably become clear by now that I’ve been sitting on the oldest episodes of this show for over six months, in some cases closer to a year now. Just waffling about it like a coward. And so once I finally embraced my more narcissistic side and mustered up the courage to releases this stupid thing, I was fucking mortified to find that another show called Selling Out, that’s with a ‘g’, had released its first episode literally a week before I started the submission process for this one.

I think the only course of action when it comes to being beaten to the punch in something like that is that they may have had the name first, but I will utterly crush them in ratings and reviews and buzz. So if you enjoy what you hear, please consider going to Apple Podcasts or your favorite podcatchers and help me bury these guys deep down in the search results with a nice review. I don’t know, I’m sure they’re nice but what can I say, I’ve got the spirit of a warrior.

Anyway, my guests today are Dylan Hanwright and Malia Seavey, and where do I even begin? Uh, Dylan was one of the primary songwriters in I Kill Giants, who, I know, they just had a big weekend of reunion shows, and no I didn’t talk to them about it, and yes, this episode was taped months before it was even announced, so, I’m trying to get about that. But you’ll just have to appreciate this episode for what it is.

You may also know Dylan from his various other projects including Great Grandpa, Trashlord, Apples with Moya, Logfella, Slothfella, there’s probably even more that I don’t know about. And I was also joined by his partner Malia Seavey, who plays in Salt Lick, Dogbreth, and a number of other bands herself. And she’s also active in design work and screenprinting, which is such a huge economic engine within this kind of music I could do a whole episode just on that, and maybe I will.

Anyway, uh, Dylan and Malia and I talked about the role of college and its value to people pursuing creative fields, the lure of the new startup job, geographical isolation, and making do in a major American City and so much more. So, I’m pleased now to give you Dylan and Malia.

[music: “it’s just the kids these days they make me feel so old / I don’t feel comfortable in my own skin / I think the best is only over / the night is slowly closing in / and I’m staring at my thighs / you watch an episode and nothing more / I think I'd rather not be sober”]

MIKE: I met you, Dylan, through mutual friends, while they and you were at Berklee College of Music. What were you studying there and, uh, you know, this might be a stupid question for anybody who's in the know, but why Berklee?

DYLAN: Uh, originally I went in for um, the major music production engineering, which is basically recording, it’s engineering, producing, all that. That’s what my draw was, I couldn’t really find that anywhere else. Yeah, I just wanted that specific, I, you know, I didn’t just want to study music or music history or something, I wanted like a specific sort of education. So, that’s why Berklee, and I had pretty much had Berklee in my sights since I was like 15 or so.

MIKE: Right, ‘cause you’re like a player and a musician, and there’s something about that school that appeals, I mean it’s obviously the most prestigious in a certain sense, unless you’re trying to something like really classical.

DYLAN: Right, right. It’s, it’s like the more contemporary of the like, the, you know, bigger music schools, and um, and that’s definitely where I, like I didn’t do jazz band or anything in high school. I didn’t really, I was more of just like playing punk shows and stuff like that. So, so even Berklee was, it felt like a little bit of a stretch but, uh, yeah. And so when I got in I kind of had explored a little more and found a different major that seemed a little more interesting to me which was called Electronic Production and Design. And that was a little more focused on synthesis and creating sound, sound design, um a lot of like EDM folks went into that major. Um, so kind of the more like lonely end of production, just the like, you know, programming and sort of using the computer to, to get what you want done in music. And it took me, took me three semesters of applying to get into that major. So I was-

MIKE: Whoa.

DYLAN: Yeah, I was pushing hard for it and finally got in.

MIKE: Wow. And uh, Malia, do you have a formal like college education, like a post-secondary, any kind of vocational music thing, or..?

MALIA SEAVEY: Not really, I went to school for like visual arts, mostly costuming and textiles.

MIKE: Oh, okay.

MALIA: I took like one music theory class, but I really, it didn’t click [laughs].

MIKE: That’s all fine too, and do you do anything in like costuming now? Visual, kind of..?

MALIA: Um, not really, I still sew, I make like um, accessories and like guitar straps and stuff like that, and fanny packs. But um, I don’t really costume anymore, yeah.

MIKE: Okay. And did you, you had like aspirations of that maybe, like for theater, or...?

MALIA: I did, yeah, for theater. Um, I did, I wanted to do movies and stuff to but it’s, you have to dedicate a lot of nights and weekends to that, and I like to play, and usually, you know, practicing ends up at those times, and shows and stuff end up during the weekends and stuff like that, so-

MIKE: So your like music habit kind of got in the, got the better of it?

MALIA: It did, yeah. Which is funny ‘cause it was definitely like more of a, just a fun side thing for a while, and then I took it more seriously, put the other stuff aside.

MIKE: I guess I’ll throw this to both of you, did, when you were going to school for something so, I mean I think a lot about hyper-specialization, so like, music production, electronic production, sound design. I went to college for audio post-production and sound design, which is so specific that it’s like everyone from my major went to LA to work in film and TV.

DYLAN: Sure.

MIKE: Except for me. Did you get any kind of push back before you went to college for something so specific that, you know, the chances of it being lucrative are so-so?

DYLAN: Um, I feel like I was incredibly lucky with my parents and like my support system, and even like friends and everyone I went to school was like yeah this is what Dylan wants to do, Dylan's the music guy, he’s gotta go do this. And my parents knew that's really you know, all I really wanted to do. My grandparents went with me to visit the school, and you know-

MIKE: That’s nice.

DYLAN: -that was a little like scary, I was like you know, what, what are they gonna think, and they came out thinking it was incredible, they loved it, they, they helped me fund my education, and uh, so yeah. I feel really lucky that I didn’t have that push back, ‘cause I feel like, you know, a lot of folks would and, I think that definitely helped me decide, like ok, I can do this. Like, people support that, and I don’t want to let them down, so.

MIKE: Of course, yeah.

MALIA: Mine wasn’t taken seriously, until I started to get work, I think?

MIKE: That’s, I mean, the best way to prove anyone wrong, definitely.

MALIA: Totally, yeah. And to be fair I did get like a art degree from a non-art school, so I think that maybe that had something to do with it, but um, yeah. Once I started making money off of it, then people were like, oh yeah cool!

MIKE: Yeah, there you go, yeah.

MALIA: It makes sense now!

MIKE: Yeah, yeah.

MALIA: ‘Cause, ‘cause people care about money apparently.

MIKE: There’s a lot to be said, I guess, especially in creative things, for the networking, uh, parts of it. Somethings I think, like I wish someone had said like, hey you don’t need to go to like a private college, like an extremely vocational school for this. Um, and I guess it depends on what you’re doing, right? Especially if it’s networking in the sense of like, the only way into an industry, definitely? But, you know, I also like met the woman I’m about to marry at that college so I can’t really complain that much, but I mean... is there anything that you can say about the value proposition of getting a degree, like an advanced degree in music, or art, or design, or whatever. Could you recommend it to anyone, or is it totally from situation to situation?

MALIA: I personally think that one of the major reasons to go to a school like that, is like how you said the connections that you’re gonna make with the people, so I think that if you can find those kind of connections elsewhere, and um like, intern and get like on-the-job experience, I think that that could be just as good and a lot cheaper.

MIKE: Absolutely.

MALIA: But I think that school offers a lot of opportunity to get jobs through professors or meet collaborators and stuff like that, that’s really what I took away from, from going to school.

MIKE: Oh, totally. For sure.

DYLAN: I think what helped me kind of break out of my shell was college, and, and like allowed me, like I, you know, I wouldn’t have met you had it not been for meeting all of my bandmates at college, and I wouldn’t have toured as heavily and like gotten that experience had I not gone to college. And like, the most I learned about myself musically um, was outside of the college playing in bands. So it was like, a lot of the experience I got outside of the schooling itself was the most valuable-

MIKE: Extracurricular.

DYLAN: Right, and...

MIKE: Right.

DYLAN: And I think I wouldn’t have done that, I wouldn’t have been so extracurricular had I just stayed, you know, tried, tried to like intern or tried to go to local venues and stuff and just gone that route.

MIKE: Yeah.

DYLAN: To, to like break into the music scene. But I think that it’s up to, it’s totally a personal thing. I think a lot of people totally have the ability to get that knowledge and expertise and experience just by getting their feet wet, getting in and doing it.

MIKE: Of course.

DYLAN: But I think college helped me kind of like have a community to like surround myself in, and get comfortable with, and, you know, we all, we all kind of held each other up, and helped each other out and, um, I think that’s something really valuable.

MIKE: And you still do, I’m sure, even, however many years later.

DYLAN: Yeah. Oh absolutely, yeah.

MIKE: And that’s actually, you’re kind of doing all my work for me here, and, uh...

DYLAN & MALIA: [laughs]

MIKE: So while you’re, while you’re at school, obviously you get involved with I Kill Giants, and I don’t think I really appreciated this until maybe after, but like that band got-

DYLAN: I don’t think anyone did.

MIKE: -got huge, it got huge! It got huge. And I, I don’t know if this is maybe what drove it home, but like the reunion set, the Broken World Fest thing?

DYLAN: Yeah.

MIKE: Was that a surprise to you? That, I mean obviously you put in the work for it, but, were you, was it kind of an unexpected response?

DYLAN: I think that I knew that it was gonna be a big show, I knew that it was, you know, that band was a big deal to a lot of people. You can’t really realize that until you’re, you know, on stage and experiencing and having a blast. But um, yeah it was a weird thing, ‘cause I know that when I left the band, I left Boston, it seemed like such an easier choice. It seemed like yeah, you know, we don’t, we don’t have that much going. Like, career is more important, but uh, you know, months later after I’d moved and kind of like saw the, the like legacy quote-on-quote? Um, that really like set in, and, it’s just like grass is always greener, you know it’s...

MIKE: Yeah, of course.

DYLAN: It, you don’t know what you got ‘til it’s gone, that sort of thing, so.

MIKE: ‘Cause you did a last EP and like a last tour, and then the reunion show and all that, do you think to tag something with that kind of finality has some effect on the response and…?

DYLAN: Oh absolutely, yeah. Yeah, um, giving people one last chance or whatever, I think, you know, it makes it a little more special, a little more memorable. It means we’re gonna try harder on our end, it’s not just another show, you know, I think, I think that, in any, in any capacity, any band doing that sort of thing is gonna see... it’s gonna feel a little more special for that reason.

MIKE: I mean Aviator never did like a last show, I think we kind of fizzled out with the understanding like, ah if you’re not riding with us now then like, we don’t wanna give anyone the pleasure, I guess, which is what-

DYLAN: [laughs]

MIKE: -what, maybe why we never really got there.

DYLAN: Sure.

MIKE: I do wanna, I wanna circle back to, uh, the reason that you left Boston, and I’ve always been curious about this. Tell me about the opportunity that brought you back to your home state of Washington.

DYLAN: It was kind of a classic start-up situation. Um...

MIKE: Okay.

DYLAN: Looking back, like, maybe a little naïve at the time, but, right as I was kind of finishing up school, someone who I had been in touch with for a long time, um, really talented game developer, programmer, who, we’d always talked about collaborating and stuff. We worked together on like, you know, a few small things throughout college. As I was finishing up, he hit me up and was like hey, I’m starting a startup, we’ve got investors, we are, you know, we’ve got this house in Redmond, WA that they’re paying rent for us, we’re just gonna turn it into a dev house. Um, you’re welcome to live there, set up a, you know, set up a studio, and basically make music for our, for, and they were working on this game, that looked amazing, felt amazing, it was a really, from my experience with it, it was a really great product that I really wanted to work on. Um, and so after, you know, a lot of like back and forth and a lot of figuring out what would be best, I decided I wanted to move back, join this startup, get into the creative world professionally. There’s that panic of being done with college and being like, oh God what do I do, I don’t wanna, don’t wanna go work at food service, you know, like... Like you’d kind of said before, going to college for something like that, you know, if you don’t have something like that afterwards, it’s like a failure.

MIKE: Oh yeah, I mean I delivered pizza, I was a mailman, I did all that stuff.

DYLAN: So, that’s kind of what made the decision for me, and uh, I told the guys I was gonna quit the band. They were all really cool with it, they were stoked for me. Um, we recorded our last EP, booked our last tour, did all the stuff, and then once we were done with that tour I pretty much got back to Boston and moved out. Moved right into the house in Redmond, and I think within like a month the startup tanked.

MIKE: Wow, I didn’t know it was that quick, I thought it was at least a...

DYLAN: It was pretty quick.

MIKE: So the project never was like, completed then?

DYLAN: Nope. No, it was uh, they had an issue with like, someone who originally was part of the team, and they decided they didn’t want to be, they didn’t want to have them as part of the team anymore, then this person threatened to sue, the investors got freaked out, were like nevermind, we’re out, and that was it. Pack up and get out of the house, and kind of moved back in with my parents, and just like started from ground zero, not, not two months after leaving Boston.

MIKE: I mean I don’t pay really, really close attention but it seems like there’s been kind of like, or maybe this was the start of an indie game development renaissance almost?

DYLAN: Yeah.

MIKE: Have you, is this something you’ve continued to try to pursue in the meantime?

DYLAN: I, it’s been, there’s been like an on and off, you know, I’ll get really inspired, I’ll get, you know, just get my shit together, and you know redo my website every you know several months, and decide now’s the time. I’m gonna write some game music. I’m gonna get some stuff out there. Let’s see what we can do. And then like, a few months later, decide it’s too hard, decide it’s just like so hard to break into, and be like, maybe another time, I’m just gonna focus on writing my own music right now. So I, I feel like I’ve gone back and forth between that for the past four years.

MIKE: Was it the major change at Berklee that kind of prompted you to get into composing for something so specific as video games? Because a lot of that has to be responsive, right, like it has to be, it’s like a totally different mindset of writing.

DYLAN: Right.

MIKE: I would think.

DYLAN: Yeah, it’s very different, and uh, I actually minored in video game scoring at Berklee, which was like, just the fact that they had a minor for that, I was like ok, this, this is doable, this is like what I want to do. Um, and I can be taught how to do it, so.

MIKE: Yeah, yeah.

DYLAN: Um, it is, and it’s, there’s, it’s a lot of tech-heavy sort of, um, knowledge that goes into it and understanding how to write for an interactive sort of experience. It’s different, but it’s something I always felt like I was good at, I’ve always loved video games, I’ve always listened to soundtracks obsessively, and...

MIKE: I mean it’s some of the most, kind of culturally memorable music for a whole, like a growing generation of people.

DYLAN: Sure, yeah absolutely.

[music: “What a gift to feel stroked off by a phrase / to be so simple and so happy and undoubting / I keep commission on the TV and I’m PKD / What a mercy we’re perpetually occluded / we crave the twangy void of the perfect diploid / I am irrational - an expert eraser”]

MIKE: Malia, are you from the Seattle area originally then, or..?

MALIA: I Grew up in Olympia, I’ve been in Seattle like eight or nine years.

MIKE: Tell me about your, your music, your bands.

MALIA: Um, I’m in a few projects. My main project that I write the most for is called Salt Lick, and it’s with a group of close friends that, a few of us have been making music together for, I don’t know, two or three years, although this project is pretty new.

MIKE: Same people, kind of reconfigured.

MALIA: Yeah.

MIKE: Okay.

MALIA: Yeah, totally. I sing in that band and like, write the words and stuff, and I joined Dogbreth last August, I think? So I drum in the band. We actually, I got home at 4:30 this morning [laughs] because we were recording for the last week or so, um, at the Unknown in Anacortes, so. Really excited about that.

MIKE: Wow.

MALIA: And, I’m in another project called Super Projection. So yeah, pretty busy, pretty busy with the tunes.

MIKE: And, do these all tour, I mean, it sounds like you were record, were you recording remotely, or somewhere nearby?

MALIA: Um, Anacortes is about an hour and a half away.

MIKE: Okay.

MALIA: It’s like this old church turned into a studio.

MIKE: Ooh.

MALIA: Um, it’s really great, loved it, I recorded there with Super Projection about a year ago as well.

MIKE: Oh cool, cool cool.

MALIA: We, we tour mildly, nothing like something people I know. [laughs] Like you know, a week or two here and there.

MIKE: Regionally, obviously.

MALIA: Totally, yeah, the coast kind of thing, maybe over to Montana, but nothing too big yet, hopefully someday, you know.

MIKE: Yeah, yeah of course. I mean you have to, especially in, in your part of the country it has to be so gradual that you get outside of your home base ‘cause everything is like, I don’t want to say we’re like lucky around here ‘cause it’s not always, results may vary, but you know, you can drive an hour and a half and you’re in like a different market.

MALIA: Yeah, I know, it’s crazy.

MIKE: I’m haunted by the three days I did in the northwest.

DYLAN: [laughs]

MALIA: Oh, long drives?

MIKE: Nobody, nobody told me that like you should really have a day in between Portland and San Francisco. So we did the whole thing-

MALIA: Oh yeah that’s a long one.

MIKE: We did an overnight drive, and we were just fucking zombies, and didn’t get to-

MALIA: Sleepy gig? [laughs]

MIKE: Oh, boy.

MALIA: Yep, been there.

MIKE: Just running off of fumes. Um, so take me through some of the, you know, you’re obviously playing in bands too, and trying to support recording and all of that, how are you making money? You said you got some work doing like costuming, and design and stitching, how else are you paying the bills?

MALIA: Um, so I worked at a sewing shop sewing and then eventually managing for like four years after school. And then eventually, about a year ago, I left to do some screenprinting, I started screenprinting on the side while I was working at that shop. So that’s mostly how I make money right now, is printing shirts for organizations and like bands and all sorts of different things. Shirts and um...

MIKE: You own all the, you own like the presses and all that stuff?

MALIA: No, no.

MIKE: NO? Oh, okay. Do you work out of a studio?

MALIA: Yeah, I work out of a couple studios, I work out of um, a place called Fogland for flatstock and then I um, I work out of the Vera Project for some t-shirts and other, other stuff like that. And then, I’m like a dogwalker, like I had a dog walk today. I do like random jobs like here and there like that, and I don’t know, we do some random like, pickup work and stuff like that.

MIKE: Sure, sure.

MALIA: Yeah, mostly that.

MIKE: Like gig economy stuff.

MALIA: Yeah, I guess so. And I, I do some sewing, freelance sewing for people. I also have a company where I sew like um, accessories and straps and stuff like that, and I sell them at like craft fairs and stuff like this, to friends. Fix people’s stuff.

MIKE: So, going from working for a company for several years, and uh, you know, at the time we’re recording this, it’s tax season, that surely won’t be true by the time this comes out but, have you, like what has been the difference between working for someone and working for yourself when it comes to that sort of adult responsibility shit?

MALIA: Totally. Well, it’s definitely hard at points, but then it’s, it’s really nice to have um, the freedom to decide what I want to do and when I want to do it.

MIKE: Yeah.

MALIA: Um, that can also be kind of scary though. It’s hard to stay motivated sometimes, but I feel like I, I do a really good job at keeping busy [laughs]. So, whether it’s something-

MIKE: That’s, I mean, you have to, yeah.

MALIA: Yeah, whether it’s something that’s making money or not. I do a lot of inexpensive things now, like um, creating art, and stuff like that, like, you know, playing music, but. I mean, traveling is expensive, but I, I feel more creative now that, you know, I’m not like drained all day at the sewing shop somewhere.

MIKE: yeah, I mean that’s, that’s worth everything if you can make your schedule work for you, then that’s, I mean, so, I was a, I was a, I mean I still kind of am, but I was only a recording engineer for, I don’t know, two years maybe? And I remember the first year that I filed taxes and I owed like $1000, and I was like AUGH!

MALIA: Oh yeah.

MIKE: And then I got a side job and that kind of all balanced out, and I was like ok, alright I can like surrender a little bit, and then you kind of just inch a little bit more toward giving more and more of your time.

MALIA: Mhmm.

MIKE: Um, is what you do kind of feast or famine? Are you like loaded with work at times and then there’s a dry spell for a while? Or is it fairly constant?

MALIA: It’s pretty even. It’s, yeah, I mean, there are definitely, it, I’m always working on a project but sometimes they do stack up. So. Sometimes it can be a little bit overwhelming in that sense, but um, I don’t know I think I strive off of being incredibly busy, so, it’s good for me [laughs].

MIKE: It’s good, I mean, there’s nothing worse than getting really busy and then having a drought and then having to kind of string yourself along financially through all of that. Um, I guess I should get back to, so take me through, you alluded to this Dylan, within two months of moving out, you’re kind of back to the drawing board. You’re freelance now, but how are you kind of stringing yourself along between then and now?

DYLAN: So, um, I moved back in with my parents, they live like an hour south of Seattle. And so, that was kind of when I was back there, it was kind of a scramble, I was, you know, broke, trying to figure out like well, do I move back to Boston? Like I spent so much money getting back here,. but maybe if I can get a job and raise some money, like I can get back to Boston, just kind of, just resume what I was doing. Um, and so I moved to Seattle ‘cause I got a job teaching children how to ride bikes.

MIKE: Whoa.

DYLAN: That was my first job in Seattle. Uh, did that for a summer, basically took that whole summer to just like catch up to my credit card and pay off debt. So at that point, I’m like, now I’m, you know now I’m maybe a little bit in the black, but still nowhere near able to move back to Boston. Even, nonetheless pay for a plane ticket. So, I was like well I guess I’m here in Seattle, I gotta get a new job. Um, you know, I worked at a hospital doing, like, sound and video for conferences, and then I worked for a game company for quite a while. And then during all this, just kind of let go of the idea of moving back to Boston. I started to like make friends, I Started to meet people, started a band. And just like in all of this, sort of working a day job, just kind of like doing music when I could. A year or two after, you know, I had to move back with my parents, it was like, I’m in Seattle now, this is where I'm at, this is what I'm gonna do. Because it’s a great city, and it/s, there’s still, it’s like you said, it’s kind of a, you know there’s a renaissance for indie gaming, and there’s always gonna, it’s always gonna be there so, you know, I might as well just grind and grind and see what this can do for me.

MIKE: Let’s, I guess let's talk about Great Grandpa, right? I mean that’s going pretty well, huh?

DYLAN: Yeah, uh, as well as anything has gone for me in a band.

MIKE: It seems like it anyway.

DYLAN: You know, we put out a record on a label, and we had a booking agent, and we were like cool, let's do this, let’s do this music thing full time. And that was in July of, uh, 2017.

MIKE: How has that been? How is that, how would you describe...?

DYLAN: It's a strange world because it’s just like, it’s not that you have a better job, it’s not like you have more of an income playing in a band. It’s that maybe down the road-

MIKE: Whaaat?

DYLAN: -you will, you really have no idea but the only way to find out is just to do it. And so, that’s kind of where we were at. We had finished recording this record, we spent a lot of time on it, we got a booking agent through it, Greg Horbal, who, you know, maybe that wouldn’t have happened had I not gone to school also. So it’s like all these things that just, all these experiences, all these people, all these connections just kind of like culminated in like, great! We got a booking agent, our booking agent helped us get on a label, the label is, you know, run by folks that I’ve known for a little while too. And it’s like, sort of a, all came together at once. And um, we’re like great, we’re ready to release this record, Greg got us on our first full US tour with the band Rozwell Kid, who are some of my favorite people that I’ve known for a little bit. And uh, so it all just, it worked out so perfectly, we all felt so like, you know lucky and blessed and just kind of went for it. So, ok, let’s quit our jobs, let’s tour, and during that tour we got our offer for the next tour, the Citizen tour. Um, and then during that tour, we got an offer for the Diet Cig tour, and just kinda like, you know, you just kinda keep going.

MIKE: It’s kinda rolling at this point.

DYLAN: Yeah, you just do it. Maybe it doesn’t really work out monetarily, you kind of flounder a little bit, but, you know, when we’re on tour, we get like daily per diems to eat basically, that’s just like what we’ve budgeted for ourselves based on how much we make per show. Um, everything else pretty much just goes back into the band fund, we don’t really see a lot of that, so, um, really I just kind of saved up enough at my old job as I was preparing to quit to really just help me get by those months when I was back home, or like you know, paying rent when I’m on the road. But really, it’s like we don’t see a whole lot from the band itself, it’s still just kind of an investment towards our own future. And recently we, like, we were like feeling you know pretty, like ok, we just kind of settled down, we’re you know, about to finish off this eight months of touring, what do we want to do as far as money? Like, we get our payouts every day, but you know...

MIKE: You still have like phone bills.

DYLAN: Right, exactly. Like, what, what should we do, and so we kinda looked at what we had and just like decided on a fair amount that everyone should get, just because we had just gone through all this, you know, stuff with the record, we got like a publishing deal, and, you know. And so they gave an advance that says like, as a a band you get paid when something gets placed and licensed and used, but when a publishing company, sorry and this was all new to me when this started happening. I learned pretty quickly.

MIKE: Right, this is all kind of stuff that I’ve heard peripherally about.

DYLAN: Right, right.

MIKE: It’s so alien to me that it’s never really made sense, but.

DYLAN: It’s bizarre. It’s just insane that someone would just give you money to, to have the rights to your record whether or not it’ll get placed, you know, they could potentially not make any money off of us, you know, and, but, they kind of put their faith in us and said here’s this advance. And, so anyway, without going into like, you know, too much further into like what we make as a band.

MIKE: Sure, sure.

DYLAN: It’s, it’s not comfortable, it’s still sort of like we’re grinding, but there’s a little bit of hope on the horizon of like, ok, this happened, you know, how can we keep making this happen. How can we keep making enough to like keep ourselves afloat personally, while also like having money for the band, you know, so many expenses. The van, the trailer, the-

MIKE: Oh my God.

DYLAN: -the gear, just, yeah it all adds up. So, it’s like striking that balance is really, is a tough thing, but.

MIKE: Is there anything that you, or your bandmates, either of your bandmates, uh, that you could do from the road and like kind of generate some income while you’re, while you’re out?

DYLAN: For most of us, it’s work, work, work while we’re home, have enough to like survive on the road and pay rent, but uh, Pat from my band, uh, he’s a 3-D environment artist. Um, he does, yeah he works on video games and like VR experiences.

MIKE: Wow.

DYLAN: And so, yeah he’s been able to do a ton of work from the road, um, you know he’s had like business calls in the van, and you know, [laughs] shit like that. So, uh, it’s possible, I think it, for me unluckily, it’s, I can’t really, I don’t have a, I don’t have like a laptop, I can’t really work on music on the road in that capacity. I really prefer to have like my whole setup. So yeah, it’s more of just kind of like marinating on ideas and stuff, if that counts, but other than that, no.

MIKE: Sure it does.

DYLAN: There’s not a whole lot of money to be made, you know, freelance-wise on the road. For me, personally, I don’t know.

MALIA: I do some like, poster design and stuff like that, and I can like prep artwork for screenprinting when I get back and stuff. Uh, that’s pretty much the extent of mine though.

MIKE: Yeah. Can you like-

MALIA: Do like some clerical stuff, Photoshop.

MIKE: Can you like book work while you’re out and take like deposits or whatever? That was like, that was my bread and butter for a while.

MALIA: Yeah, definitely. I don’t really take deposits on stuff, but um, just like, yeah having, having work ready when you get home is important, or when I, for me at least.

MIKE: Oh yeah, of course. If you can line it up in advance, then, it feels a little better to be like ok I got two more weeks, one more week.

MALIA: There’s money on the horizon! [laughs] Yeah.

MIKE: Before you start calling home for a handout or anything.

MALIA: Oh my God.

[music: “I never thought it’d be easy / I never wanted to see it / and I don’t want to need it / like I do anymore”]

MIKE: Dylan, you’ve spent time outside of Seattle, like I won’t pretend to know enough about the music scene here that I can make this comparison, but at least, talk me through maybe the differences between Seattle and Boston in terms of like, I don’t know, just the cost of living, the opportunities that you get.

DYLAN: You know, I think Boston’s definitely, it costs more, but I also have a, I like got lucky with my situation here, and you know, pay a lot less than average. So that’s, you know, just my experience. But uh, cost-wise, it’s definitely seems more expensive to live in Boston, however, the community, the music scene that I was involved with, and still like tangentially am, in Boston, feels a lot more supportive but at the same time kind of like tight-knit. And I feel like I, I luckily have that tight-knit community around me, and that was really, I was really fortunate for that, and I think that helped me sort of like, exist in the music scene and, and you know, um, succeed. Uh, whereas here, it’s there but it’s not as, it’s not as like close, it’s not as friendly, it’s like everyone in the scene are, they’re my acquaintances, and I have some very close friends in the scene, but it’s all kind of-

MIKE: IT’s almost counterintuitive to think that a bigger music scene that’s kind of centered on these institutions like Berklee for example would be more cooperative, ‘cause you’d think that kinda breeds competition in a way, and kind of like shitty attitudes. And I think there’s probably that, too, occasionally.

DYLAN: Right. Well and that’s the thing, I feel like, you know, I’m sure that in Seattle there are these tight-knit communities, you know, through the college, or you know, just, there’s so many different communities, and there are very close communities where people have positions where they can book at prevalent venues and like you know, help out, sort of the DIY scene and help kind of raise it up. I feel like Boston, I saw that a lot in Boston. I saw people got positions at these venues, people like moved up and used that to like try to help each other out, and I just saw people turn from DIY people to like music professionals, but they’re still grounded in DIY.

MIKE: The rising tide lifts all boats kind of deal.

DYLAN: Yeah, absolutely. And so like I said, I’m sure that exists here, I just, it’s, I’m part of the scene in a different way here, I’m just a different sort of...

MIKE: Tapped into a different vein of it.

DYLAN: Right, right.

MIKE: Malia, have you lived in this area you’re whole life?

MALIA: Um, I’ve lived in the Pacific Northwest for most of my life that I can remember [laughs]

MIKE: Sure, and is-

MALIA: But like I said, I moved here like eight years ago or so.

MIKE: Of the places you’ve traveled is there anywhere else you could kind of see yourself, like doing what you do in kind of, or is it really all about your social circles here?

MALIA: Um, I really appreciate the connections I have in Seattle, and I think that that makes it really difficult to imagine moving, but unfortunately, Seattle is getting um really expensive. So, I have lucked out in that I have a really affordable rent, but that is kind of, it’s not easy to find that, you have to kind of have an in to a house or something, or like, be willing to live with a bunch of people. So, eventually I’ll probably have to see myself in a different place. But I, I think my skills are transferable. I think I can do this kind of thing.

MIKE: Oh, no doubt.

MALIA: Live this lifestyle, you know, in a lot of different places so I’m not too worried about it.

MIKE: I mean anywhere there’s an artsy enough community to sustain it. But I guess in terms of the price of rent, like, that’s something that obviously Boston has down, um, well I should say up.

MALIA: Is it expensive there too?

MIKE: Oh my fucking God. It’s, it’s out of control, and it’s only, I feel like it’s only gotten worse since I initially lived here for college. Like you could find places for like $675 a month and now it’s [whistles] off the charts. Um, how close to the city are you?

MALIA: Dylan lives lieka five-minute walk to a light rail that brings you right in. ANd I, I live, it’s called the U DIstrict, it’s like where the University of Washington is, and it’s like a five minute bus to downtown, but, other than that, my neighborhood has, you know, a lot of what I need anyways. It’s like got a lot of, I got a lot of friends living around me and lot s of little house venues here and there.

MIKE: And how is that connected to, where do you practice with your bands, where does your, how far of a commute is the different places that you do screenprinting or whatever else?

MALIA: Um, I practice in Ballard, which is, you know, like a five-minute drive, without traffic from my house, so it’s not that bad. Or you know like, 15-20 minute bike ride.

MIKE: In like a rehearsal room, or uh, somebody's house?

MALIA: Yeah, I have a practice space. And then I practice at, um, my bandmate’s house, for Dogbreth, which is literally two blocks from mine so it’s like incredibly convenient.

MIKE: Oh, awesome. So all your gear lives there, and all that too?

MALIA: Mmhmm. Yep.

MIKE: Cool.

DYLAN: Yeah, and for me, I’ve kind of built, [laughs] built everything I need into my house. Uh, I, like I live with a bunch of people but I’m fortunate enough that they’re willing to, you know, have, let bands have practice here, and have me record here and all that stuff, so, um. Yeah luckily everyone comes to me for practice, in all three of my projects, so that’s pretty cool.

MIKE: Yeah it’s nice isn’t it?

DYLAN: Yeah, yeah. But like Malia said, I’m pretty close to downtown if I need it, you know, I think we’ve both just kind of set up our lives that, the stuff we need, you know the stuff about a city that you need, so like, you know, just accessible public transportation, accessible groceries, and somewhat of like a social scene. I feel like we've kind of got all those bases covered, sort of where we live, we kind of live on opposite sides of downtown.

MALIA: Dylan even brings the gig to him.

DYLAN: That’s true, yeah.

MALIA: [laughs]

MIKE: That’s right, you do.

DYLAN: We have shows here, and uh, yeah so really I don’t have to leave the house, ever.

MIKE: I mean, I’ve talked to, I’ve talked to folks who do gigs at their house before, and that’s a whole, that’s a whole ball of wax that, I mean there’s so much personal liability that comes into it. Like, you obviously know I had a house set up a little like yours, I didn’t share it with people, but um, you know, I, the night that I had to move out, like, somebody had said like when you get out of here, you should do a show and just like tear the place up. And that’s the only, that’s like the only outcome i can imagine, just like so much destruction. How do you, like, how do you navigate that? Is everyone pretty respectful generally? Do you find yourself putting a lot of rent money into like-

DYLAN: No, you know I kind of started out the venue, you know started booking shows with this sort of understanding that it’s like not a party house. We do shows here, and that’s it. You know, and, I want people to have fun and I want people to have a good time, but there is like, I’ve just seen, yeah, I’ve seen you know, what you’re talking about. I've seen some pretty rough DIY spaces in both audience kind of like unruliness but also sort of like promoter just kind of like, yeah we could have a show! And then they’re not there for an hour. You know, after bands are supposed to show up and they’re just drunk, or like whatever it is, so I think like my goal for the venue is to kind of like make it a place where people felt safe, where bands felt like they were communicated with, and like you know are willing to play here. And yeah for the most part it’s like kind of part of this venue now is that it, it is a pretty mellow, mellow place to see a show. And, I tend to even avoid like, you know, like louder punk bands, which part of me feels bad about, because that, you know, I still like that music. But, it’s also like-

MIKE: That’s sellin' out, dude. [laughs]

DYLAN: Yeah.

MALIA: A lot of thought goes into, um, like the promotion of the shows too, that’s like specifically respect the space, and I don’t know people are reminded that throughout the night sometimes by the bands.

MIKE: Doesn’t it suck to have to remind people of that?

MALIA: It does, I get it though. I think that people that don’t organize shows, they don’t really think about that, you know. They just go to this show and they’re like it’s a party! But um, you know, when you’re like hey this is our fuckin’ house, like, can you please [laughs] respect it, and like-

MIKE: Yeah, I see like, like pillows on couches and-

MALIA: -clean up after yourself, and you know.

MIKE: Yeah, of course. I, uh, in the interest of like journalistic fairness I should probably interview some like ornery landlords or something.

MALIA: [laughs] yeah.

MIKE: Uh, what’s your ideal situation, either of you? Like in terms of like earning, and making a living, like how does that, how does what you’re doing now play into it, into like a larger goal?

MALIA: I mean hopefully in the future my ideal would be like making a little bit more money, but like as for what I’m doing, like, I don’t really see myself wanting to anything much differently. Which is like a nice place to be in in life, I don’t, I feel really content with the activities that I do on a day to day so to speak.

MIKE: That’s great, that’s always nice to end on a high note.

DYLAN: Yeah, and it, to go off of that, I’d be stoked to like be similarly like, in any realm of possibility making more money off of music to support myself and, and be able to fund my insatiable need for video games and uh, and music gear. That’s all I need.

MIKE: Oh man, that’s a money pit right there.

DYLAN: It is, it really is, I don’t think anyone can really afford it.

[music]

MIKE: As always, if you liked what you heard today, I urge you to support Dylan and Malia in their numerous endeavors however you see fit. There is a veritable plethora of links and info in the description of this episode, including a link to the ever-growing Spotify playlist of songs featured on the show. You can find a transcript of this and every episode on my blog at sellinout.tumblr.com. If you want to support the show and get exclusive bonus content you can find out how to do that at patreon.com/sellinoutpodcast. Follow the show on Twitter, @SellinOutAD. Leave a nice rating and review on your favorite podcatcher, it helps others find the show. Or you can screenprint some bootleg Sellin Out merch, sell maybe two, and leave the rest to be eaten by moths in the attic.

Our theme song is “No Cab Fare” by Such Gold. Photography by Nick DiNatale. I’m Mike Moschetto, this is Sellin’ Out.

#dylan hanwright#malia seavey#salt lick#dogbreth#i kill giants#great grandpa#trashlord#podcast#sellin out#transcript#transcripts

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Una vita per gli altri: il coraggio di Fannie Sellins, uccisa dagli uomini dello sceriffo perché difendeva gli operai e i loro bambini dalla violenza padronale “Mi accusano di aver portato scarpe ai bambini di Colliers. Quando penso ai loro piedi scalzi, blu a causa del freddo pungente dell’inverno, sono ancora più convinta del fatto che, se è sbagliato aiutare quei bambini, continuerò a commettere un reato finché avrò mani o piedi per strisciare sino a Colliers.” Era così Fannie Sellins, una donna coraggiosa che non aveva paura di stare sempre dalla stessa parte: quella degli ultimi, degli emarginati, dei miserabili. Non solo perché era anche lei immersa in quel carnaio di uomini, donne e bambini, che negli Stati Uniti a cavallo tra 800’ e 900’ erano costretti a lavorare in condizioni inumane per sopravvivere; non solo perché, giovane vedova, aveva dovuto tirar su quattro figli racimolando un salario da fame in una fabbrica di indumenti di St. Louis; ma anche perché riteneva che ognuno dovesse impegnarsi per gli altri: per i loro diritti, per la loro libertà, per la loro felicità. Per questo aderì al nascente movimento sindacale e guidò importanti scioperi ed agitazioni, in difesa dei lavoratori e delle lavoratrici, ma soprattutto si prodigò per fornire assistenza a tutti coloro che erano in difficoltà. Aiutava le donne sole, le famiglie indigenti, dava cibo agli orfani, organizzava raccolte di generi alimentari, di vestiario, di coperte da distribuire a tutti i bisognosi. Insomma Fannie viveva per gli altri. E questo suo sfrenato attivismo di certo non piaceva a chi sul lavoro, sul sudore, sulle fatiche degli altri costruiva i propri imperi economici. In particolare non piaceva ai padroni della valle del fiume Allegheny, una regione zeppa di miniere e impianti siderurgici. La chiamavano la “valle nera”, per la violenza con cui le autorità reprimevano qualsiasi tentativo di emancipazione sociale. Ma quando Fannie fu mandata nell’area dall’United Mine Workers, il sindacato dei minatori, riuscì in poco tempo a guadagnarsi la fiducia dei lavoratori e ad organizzare diversi picchetti. Fu proprio nel corso di un’agitazione che una dozzina di uomini dello sceriffo, insieme ad un gruppo di guardie, attaccò i minatori con una violenza inaudita. Fannie si lanciò verso i picchiatori cercando di proteggere Joseph Starzelsk, un lavoratore in fin di vita e alcuni bambini, figli di minatori in sciopero. Gli uomini dello sceriffo e delle guardie, forse riconoscendola, lasciarono Starzelsk in una pozza di sangue per darle la caccia. La raggiunsero e dopo averla atterrata, le spappolarono il cranio e le spararono alla testa e alla schiena. Per l’omicidio di Fannie una giuria della Pennsylvania decretò che l’unico colpevole era la vittima. Non avrebbe dovuto protestare, scioperare, aiutare chi era in difficoltà, avrebbe dovuto lasciare i minatori allo loro sorte. Ma Fannie non poteva farlo, Fannie era così, lei viveva per gli altri. (Cannibali e Re)

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

History fuckin repeats itself

1914, The Ludlow Massacre, where the Colorado National Guard and the guards from the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company attacked a camp of 1,200 striking coal miners, resulting in “the violent deaths of between 19 and 26 people; reported death tolls vary but include two women and eleven children, asphyxiated and burned to death under a single tent,” and sparking the Colorado Coal Field War

1917, Frank Little, a labor leader and member of the executive board of the Industrial Workers of the World, was beaten and abducted from his boardinghouse, dragged behind a car, and then hanged from the Milwaukee Bridge. No one was ever prosecuted for his murder.

1917, Bisbee Deportation, where 1,300 striking miners and union sympathizers in Bisbee, AZ were arrested, loaded into cattle cars, and “deported” 200 miles away into New Mexico by a 2,000 member deputized posse. The town mining company had provided a list of all citizens who were to be arrested, and closed down any outside communications with the town for several days.

1919, Fannie Sellins, a union organizer, shot to death by deputies when she tried to stop their beating of a picketing miner, who was also killed. She was shot 4 times and her skull was fractured by a cudgel; her death was ruled a justifiable homicide, and she was blamed for starting the riot which led to her death.

1920, The Battle of Matewan, or the Matewan Massacre, where 7 Baldwins-Felts detectives, 2 miners, and the mayor of Matewan were killed in a gun battle after the detectives had forcibly evicted several miners and their families on orders of the local mining company

1921, Sid Hatfield (ex-miner, union-supporter, and chief of police of Matewan who had resisted the Baldwin-Felts detectives in his town) went to stand trial, along with his friend Edward Chambers, for conspiracy charges in an unrelated incident. Both men, unarmed and accompanied by their wives, were shot to death on the McDowell County Courthouse steps by several Baldwin-Felts detectives.

“None of the Baldwin-Felts detectives was ever convicted of Hatfield’s assassination: they claimed they had acted ‘in self-defense.’”

1921, The Battle of Blair Mountain, sparked by Sid’s murder, where 10,000 armed miners marched to Logan County in an attempt to unionize the southwestern West Virginia coalfields against 3,000 ‘lawmen’ and strikebreakers backed by the coal companies. The fight went on for over 5 days and the US Army had to intervene on presidential order. It was the largest and most organized uprising in US history aside from the Civil War.

1922, Herrin Massacre; striking union miners killed 19 strikebreakers and mine guards after the coal company disregarded their union agreement. 3 union miners weer also killed in the fight.

1929, Loray Mill Strike, 1,800 mill workers from the Loray Mill walked off their jobs to protest intolerable working conditions, and demanded a forty-hour work week, a minimum $20 weekly wage, and union recognition; in response, management evicted families from mill-owned homes. Later, nearly 100 masked men destroyed the National Textile Worker’s Union’s headquarters, and the NTWU started a tent city on the outskirts of the town protected by armed strikers.

Also here’s a timeline of labor uprisings in the US and other countries

Know your history. This has been fought many times before. There is power in a union.

After a manager at a Dollar General asked about the unionization of a nearby store, the company fired her

Missouri, an overwhelmingly poor, GOP-dominated state, where a new “right-to-work” bill will face a referendum on the 2018 ballot, is at the heart of the battle over the nation’s surging trade union movement.

Despite the stacked deck against unions in Missouri, the employees of a Auxvasse, Missouri Dollar General store were able to unionize, defeating the company’s written commitment to being “union-free.”

Dollar General is one of many businesses that “promotes” workers to manager in order to force them to work unpaid overtime. Margeorie Nation was one such manager, of a Dollar General in Glasgow, MO, and she asked other store managers what they knew about the unionization drive in Auxvasse. Shortly thereafter, she was fired, despite never having been reprimanded and having led her store to win an award from Dollar General head office for sales and customer satisfaction.

Dollar General advised its investors that the company’s fortunes were looking good thanks to rising inequality in the US and the expansion of a poor underclass who can’t afford regular retailers. Nation has retained counsel to sue the company for wrongful dismissal. But of course, if she’d been unionized, they’d have protected her – a fact that can’t have escaped the notice of her erstwhile work colleagues.

https://boingboing.net/2018/01/08/is-an-injury-to-all.html

750 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kickass Women in History: Fannie Sellins

Kickass Women in History: Fannie Sellins

Thanks to a recommendation from Dennis, we have Fannie Sellins as this month’s Kickass Woman in History. Sellins was a labor rights activist who lived from 1872 to 1919. She was murdered while fighting for the rights of miners in Pennsylvania.

For much of her life, Sellins (born Fannie Mooney) lived a typical urban working-class life. Sellins was born in Cincinnati, but her family soon moved to…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

On this day, 26 August 1919, former garment worker Fannie Sellins who became an organiser with the United Mine Workers of America was murdered by company thugs and sheriff's deputies during a coal strike in Pennsylvania. She attempted to intervene when a miner was being beaten, and was shot and killed. Her killers were never punished. Episode 7 of our podcast is about miners' struggles in the US at this time, check it out here: https://ift.tt/2B3Mw2c https://ift.tt/2ocITgM

19 notes

·

View notes

Link

[August 26th 1919] (United States) United Mine Worker organizer Fannie Sellins was gunned down by company guards in Brackenridge Pennsylvania.

0 notes

Text

Fannie Never Flinched by Mary Cronk Farrell

Fannie Never Flinched by @marycronkfarrel #nonfiction #history #laborhistory #laborunions #womenshistory #biography #humanrights

Fannie Never Flinched: One Woman’s Courage in the Struggle for American Labor Union Rights by Mary Cronk Farrell. November 1, 2016. Harry N. Abrams, 56 p. ISBN: 9781419718847. Int Lvl: 5-8; Rdg Lvl: 7.3; Lexile: 1020. Fannie Sellins (1872–1919) lived during the Gilded Age of American Industrialization, when the Carnegies and Morgans wore jewels while their laborers wore rags. Fannie dreamed that…

View On WordPress

#biography#history#human rights#labor history#labor unions#Nonfiction#US history#women&039;s history

0 notes