#except instead it's his husband and never shows his ugly mug during the day.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

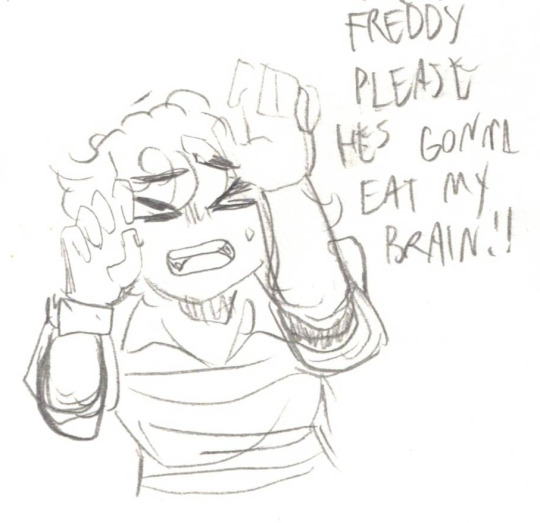

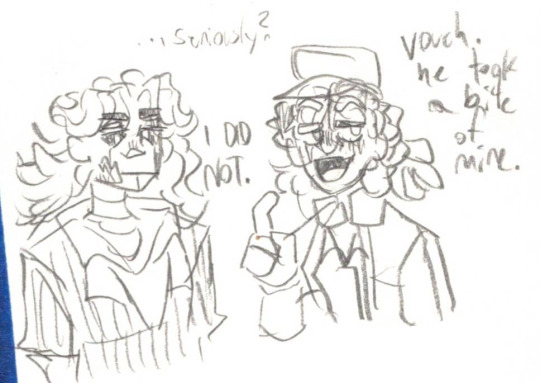

some more of my ennard michael/pizzaplex owner au

transcripts in alt text

#biggest thing to note is that this michael has ballora's eyes still :3#jeremy works as an overnight technician and reports happenings back to michael#biggest 'i have a bf but he goes to a different school' energy ever#except instead it's his husband and never shows his ugly mug during the day.#five nights at freddy's#jeremy fitzgerald#michael afton#jeremike#art.psd#gregory fnaf#fnaf security breach#fnaf sb#fnaf#fnaf art#fnaf fanart#mucking queue#fnaf au#pizzaplex owner au

236 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bride • Chapter 10

The Honeymoon: he’s heartbroken, she’s homesick, they both go hunting. what could go wrong?

in which everything is settled, until suddenly it isn’t

Prologue (if you haven’t read The Bride yet) • Chapter Eleven (not yet written) • on ao3

Although Tommy had insisted there was a bit of side business with the Chinese that needed wrapping up, Polly put her foot down and more or less kicked him out of the city.

"Honeymoon?" Esme said, just as displeased. "Where to? I'm not going to bloody France."

"I'm absolutely not fucking going to France," said Tommy.

"Not going to Italy, either," said Esme.

"And if we go to Ireland, we're likely to get our throats cut," said Tommy.

"The IRA."

"Exactly."

Polly put down her pen. "I pray every morning for the patience to get through the day, and every day, He fucking tests me. Esme, don't you want to be out in the countryside, with the grass and the rabbits and the shite?"

"Yes," Esme admitted.

"And Thomas, would you rather be shooting birds, or would you rather be dragged into the hellhole of social dilemmas that is planning a wedding between a Catholic Rrom and a Protestant prostitute, with all of Birmingham watching?"

Tommy gave her a look that expressed his willingness to die instead.

"It's all happening now," Polly said. "Better to get the wedding in sooner than later, otherwise she'll be showing the baby as she walks down the aisle. I'll handle it for a couple days. Now go and pack." She picked up her pen again.

Packing was simple: food, a horse, and a rifle each. A tent. The complicated part was figuring out how exactly she was going to bring herself to fuck him.

Yes, he hadn't betrayed his sister, and she still felt mildly guilty about fighting him so hard on it now that she knew the truth; and yes, he'd been blessed with the austere, savage beauty of a mountain god; but at the end of the day, there was nothing on the face of the Earth less appealing than the prospect of fucking a man who would be thinking of someone else the entire bloody time.

Their ride together didn't help. There was nothing romantic about hunting with a heartbroken Tommy; he was exactly the same, except surlier and more taciturn, to the point where Esme couldn't tell whether or not he was only generally angry at the world, or also angry at her specifically. By the evening, she was so irritated with him that she stopped trying to figure it out, and instead focused on the familiar pleasures of the sunlight and birdsong round them, the slight chill in the wind, the silent communication between herself and the roan mare beneath her.

The one pleasant surprise came when they settled in a relatively high spot, sheltered from the east wind by a small copse of trees. Esme was expecting the messy job of plucking the wood pigeon he'd shot, but he did it himself. After she'd rustled up the tent, she watched him still aggressively plucking away. It was a little funny, the childishness of it all.

Tommy glanced up and caught her smiling. "What?" he demanded.

"Nothing." But that settled it. He could be as sullen as he liked; she didn't take it personally. The night air was as crisp, the silence as full as she remembered. It was good to be halfway home, at least for a little while.

That peace slipped away when they slipped into the tent. It wasn't quite autumn yet, but it was cool enough that she was aware of his warmth beside her. The one thing the hill lacked, she thought, was a watch. Without a way to tell time, every excruciating moment of this fucking waiting rolled into the next with no warning of when it might be done, and he neither moved nor slept. How long? How long? How fucking--

"Alright," Tommy said roughly, turning on his side. For a moment, he hovered above her, pale eyes hard as flint, and then, as he came close, she put her hand over his mouth. He froze.

"We could lie," she said. "There's no way they could tell otherwise. There's years of lying in it before anyone begins asking questions about fertility. Then there's doctors, all kinds of tests. We have time."

His eyes moved over her face, and she thought she could read disbelief, then relief. Or possibly disappointment? How could relief and disappointment coexist? She lifted her hand.

"I thought you weren't leaving," he said.

"I'm not."

"Then why?"

"Because I'm not leaving."

Silence.

A smile flitted across her face.

"What?"

"'s just occurred to me that I may be the first woman who's ever said no."

He propped himself up, half-sitting against the saddlebags, and produced a cigarette. "Regan O'Donnell, fifth form."

"Your poor little heart."

He gave a wry smile, and offered her a cigarette. She took it, and he lit it.

"Good odds I'm not the first man," he said.

"The first man that's not wanted me? Is this another lovely Shelby tradition, telling your wife she's ugly?"

"Not the first man you've turned down."

"Ah." She went through her past quickly. "I wasn't so discriminating in my younger days, especially during the war. The number's lower than you might think."

He cocked an eyebrow, then settled back for half a cigarette's silence before saying, "Do you think you'll ever change your mind?"

She shook her head. "Just think of me as the blood relative that everyone's always reminding me I'm not."

"Don't think a blood relative would've kissed me like that," he murmured.

The corners of her mouth lifted. "A woman's entitled to a little fun on her wedding."

"And a husband's entitled to what?"

There was no threat in it, so she gave it genuine thought. "Don't think I've ever lied to you properly before. And I don't think I'll start. It's not what you're entitled to, it's just something you get."

Their cigarettes were spent, and Tommy took them both and ground them into the dirt with his boot before he lay back down on their bedroll.

Esme gave him a moment to counteroffer, and when he didn't, she prodded him. "What does a wife get?"

"A family, a room, a job. And when business permits, when she's getting choked by the factory smoke or when she thinks she wants to kill me, a ride on a horse of her own."

The offer was substantial and safe. It wasn't everything, but she acquiesced anyway. Some things could only be offered, never bargained for. "Sounds alright."

"I think it will be." With both of them on backs, in the darkness, she couldn't make out his face, but she thought he sounded satisfied.

"Goodnight, Tommy."

"Goodnight, Esme."

Esme woke panicked without knowing why. It was pitch dark and there were small unformed sounds, beside her, and fast breathing and oh. He has nightmares. She sat up, moved as far away as she could within the tent, and then pinched his shoulder. He awoke with a gasp, flailing under the blanket till he'd got it off, breathing hard and looking around him wildly. The moment he saw her, his surroundings became clear, and he visibly settled, at least a little, though there was a fear there she didn't understand until he spoke.

"Did I hit you?"

"No. I'm alright." She swallowed. Her hand moved on her knee, forwards a little, but no further. "I'm going to make some tea."

He rubbed his face and adopted his I'm-surrounded-by-mere-children voice. "We're in the middle of the woods, Esme."

"I brought a tin. What kind of a heathen do you think I am?" She reached out, palm warm and steady on the nape of his neck, as he took a deep breath in and refused to look at her. Then she ducked out of the tent.

It wasn't long before he emerged from the tent and sat beside her. She'd hung the little camp pot directly over the fire, and was poking and blowing at the embers to get a new fire started.

"I don't need any," he said.

"Well I do."

They both looked into the eye-ache of a smoky orange fire, sitting cross-legged, his elbow resting on her knee.

"It was a good speech you had back there," he said.

"Which one? I think I've given you a few by now."

"The one about the war."

"Losing people."

"Yeah."

She leaned over to check on the water, found it hadn't boiled, and settled back closer than she had before, this time loosely hugging her knees. "I meant it at the time, but looking back, I think it's bullshit."

"Didn't sound like bullshit at all." Gentle, almost.

Esme hesitated to take his invitation. "It wasn't easier then. There's just more time to think about it now. All the ways they tried to kill us, and it filled the sky with noise, and it filled every bed with people, and I think it just crowded out time to notice that you'd lost anyone for more than a minute." She checked the water again. "Do you want lemon or orange pekoe?"

"Doesn't matter."

She handed him a tin mug and a teabag, then poured carefully from the pot.

"Where's your cup?" he said.

"Only packed for myself."

"I didn't anticipate the variety of beverages."

"Next time."

He sipped slowly. In the east, the sky was showed no signs of getting any lighter. "I heard you were a nurse," he said, "But I thought you were at some hospital in the city."

"No. I was an ambulance driver for a couple weeks, then was reassigned as a base nurse."

"Don't you need training for that?"

"There wasn't much technical subtlety in what they were having me do in the thick of my first big battle."

"Which was?"

"The Somme." Out of the corner of her eye, she saw him turn to look at her. "I know. But, Tommy, there were hundreds of thousands there. You can't expect to have a monopoly on a battle like that."

"I was thinking we could have met."

"You wouldn't have wanted to meet me then."

"You were in the surgery ward?"

"Mm-hm. One doctor per surgery. And because I was stronger than some of the other nurses, they had me in on amputations, when there were amputations."

"You had to make the cut?"

"No, that was the doctor, and they had something like a guillotine rigged up for it. I had to help hold the patient down."

"Fuck."

"Don't...I asked for the reassignment."

"Was ambulance driving so bad?"

"I didn't like talking to the people." He passed her his empty mug, and when she refilled it, he stuck his hands in the pockets of his jacket. So now it was her turn to drink. "How did you like it?" she said, between sips. "Come on, Tommy, I'm sure you've got yourself a pretty nurse story. Every soldier has a tale to rival the Iliad when he's got a free hour and he meets a pretty nurse."

"Oh, but those were always lies," he said.

"I know, but I liked them."

"All right, you want a story. Let me see." He leaned back, supporting himself with his arms. They were closer now. Esme leaned into it, a little. It was chilly out, and the tea was not enough. "I had a mate, Auerbach, a half-German boy. He was a card fiend, and he was terrible at it. I used to lose to him sometimes on purpose, that's how bad he was." Esme could hear the smile in his voice. "One day, Auerbach got a straight flush, won a bunch of money off of John and a few others, and by bad luck, that was the day that Big Jimmy came by. He used to sell us cigarettes, and trinkets, but his main racket was bottles, and Auerbach, fresh off the win, got absinthe."

"Oh no."

"Yep. I got distracted helping our captain, who had fucked up some regimental papers, and before you know it, there's Auerbach climbing up out of the trench and cutting our own fucking wire to get through No Man's Land."

"Was there a strafe on?"

"No, we'd just had the one in the morning, and this was mid-afternoon."

"Did he run across?"

"Like the devil was after him. Shouting the whole time. Shouting: it's gonna be over, lads! It's gonna be over! Almost believed him for a second, when he didn't get shot right away. He made it all the way to the other side, chucked the bottle--still half-full of absinthe--at some German, and then came running back home. Poor captain wasn't sure whether to court-martial him or give him a medal. Next morning, he swore he'd become a teetotaler. Never drank a drop since."

By now, somehow his arm was round her, her hand was on his knee, and her head rested on his shoulder. It was too comfortable, she thought, to bother moving. "I like your story," Esme said.

"Thank you."

"It's not a pretty nurse story, though."

"Of course not. In reality, he got caught in the wire halfway through and shot to pieces."

She patted his knee by way of apology. She hadn't been looking to make him speak of reality. "I only meant that for this to be a pretty nurse story, it'd have to make you the hero."

"I'm never the hero in any war stories."

"The king seems to think differently."

"The king can kiss my ass. Why do you want this so much, eh?"

"I thought you might like to tell. Everyone knows you threw your medals in the Cut, and it takes a particular kind of man to both throw away his medals and let everyone know he's had them at the same time. The kind of man who tells stories."

Tommy made a noise of disgust. "That's Arthur's fault. He found out when I got the damn things and he never let me forget it. It's almost an insult. Or he's proud of it."

"Or both."

"Or both," he conceded.

"We keep doing this to each other," Esme said. "Have you noticed? Taking up spare pieces of information, and then making the worst out of them."

"See enemies in everyone, and you're bound to be right eventually," said Tommy. "In Birmingham more often than not."

"But we've been mistaken every time."

"Might have to do something about that."

"Hm." She looked to the east, in mild curiosity. The sky was starting to show streaks of indigo. "What do you suggest?"

"Maybe..."

Tommy said it half into her hair, and she turned to him and tilted her head back a little to get a look. What? she was going to say, but then she knew.

They kissed.

At first, it was slow and luscious, but then Esme made a small sound in the back of her throat and surged up, clutching at his coat collar, and his fingers tangled in her hair, and oh. Oh.

He laid her down on the grass, her head on his arm and his hand on her hip and the ache was still there but fuck, so was he, tender. He pressed kisses to her jaw, her neck, her shoulder, and at the exact second she opened her eyes and saw a golden eagle overhead, he reached down and lifted up her skirt.

"Tommy."

"Mm?" His hand paused, warm, on her thigh.

Esme pushed at him, once, twice. He rolled off, onto his side, as she sat.

"I have to take a walk." She sounded wrecked, even to her own ears.

He looked as wrecked as she sounded, sprawled out on the grass, one button nearly torn off his shirt. "Esme." That was his only concession to pleading, and she was glad of it. Begging wouldn't have suited either of them, anyway; his ragged breath was enough.

His blue eyes were left unguarded and she couldn't help it. She leaned down and gave him one more kiss.

"Fuck," she said, realizing that she was still holding his face in her hands, that this was the part where she'd have to let go. She did. She got to her feet. "Fuck." She looked around. "I have to take a walk."

"Where?"

"Anywhere." The copse of trees looked inviting enough, if only because it held shadows against the light of day that she'd very much like to hide in. Without looking back, she walked into it until she was able to stop and lean against a birch and catch her breath.

God, he was fit to break her heart and she was almost stupid enough to let him.

"Fuck."

Chapter Eleven • The Boy (unwritten): Just when Esme thinks she’s got the full story on the Shelby family, a brief conversation with a local shopkeeper proves her wrong.

Thank you so much to everyone who send asks and commented and liked and reblogged and replied! you have no idea how much I needed it. this one was a struggle to get out for some reason, but I’m so happy now that it’s out.

if you have a prompt for a fic or a vid that you would like, feel free to enter my 100 followers giveaway raffle by liking or otherwise interacting with this post. I’ll randomly pick 5 people and each person can ask for a one shot fic or a short vid with whatever they like in it (no smut). I wish I could make lovely things for all of you but I still gotta finish the fic at hand as well lol. anyways. tl;dr: I love all of you very much.

@blinder-secrets @peakystitches, @prettieparker86, @tommyshelyb, @sympathyfortheblinderdevil, @annaistiredofyourshit, @lolashelby, @peakyrach, @fookingblinders, @helloandreabeth, @b000ks, @pure-bastard-extract, @siobhanlovesfilm

#Esme Shelby#Tommy x Esme#Tommy Shelby#Peaky Blinders Imagine#Peaky Blinders fanfiction#Peaky Blinders#the Bride#mine

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

DOWNTON ABBEY: ANGLOPHILIA IS EMBARRASSING by Katherine Fusco

from Salmagundi, Summer 2017 [The TV Issue]

A little past the show’s midway point, I began having the same conversation with all my friends about Downton Abbey.

“Are you still watching it?”

“Ugh. No, we got stuck in the rape plot.”

Finishing the show’s final seasons required a committed fortitude.

Sitting next to my husband on the couch, I reached for some popcorn.

“Are we still in the rape plot?”

“Mmm, I think it’s a murder plot now,” he corrected me.

The good maid Anna’s rape and its half-lives ended the show’s appeal for many.

It’s not that we’re so opposed to watching brutality on a weeknight. I’ve eaten many a taco salad while watching the women of Game of Thrones bent over the furniture; I’ve seen men shivved while coaxing the baby to nurse; and once, we watched a body dissolved in a bathtub while drinking boxed wine.

We watchers of quality television, we can stomach a rape.

And yet, Anna’s rape and the show’s many returns to the event throughout the later seasons elicit something ugly: “Why can’t they drop that?” “I’m so sick of the rape plot.”

The most justifiable version of our aversion to the rape is that we see the creators of Downton, along with the producers of the other, more violent television we consume, treating rape as a mere plot device.

And yet, I suspect it’s something else. My hunch is that Anna’s rape by a rakish footman felt like a betrayal to American viewers who had grown accustomed to the show’s other pleasures. Sometimes despite ourselves.

Ten or twenty years ago, I would not have watched Downton Abbey. I would have distanced myself from those who did.

On a recent visit to a grad school friend, I caught a flicker of that old feeling. She’d gotten herself on a mailing list that must have been taken from PBS or NPR donors, or the multitude of New Yorker subscribers, with issues perilously towered between toilet and sink. Maybe the targets were literature teachers like us.

The catalog sold Far Side “School for the Gifted” sweatshirts alongside mugs with the phrase “She who must be obeyed” lettering their shiny bellies. The kind of tchotchkes you might buy for your AB/Fab-watching mother for Christmas when you are a teenager and you don’t care to know anything very specific about your parents’ wants and desires. Have a Starry Nights umbrella; have a magnet of The David in a Hawaiian shirt.

My friend and I, too old, responsible, and inclined to acid reflux to drink and smoke as we did in school, lie on her living room floor, eating takeout, sipping beer, and playing a game wherein we have to pick one item from each of the catalogue’s embarrassing pages that we would be willing to own. Not surprisingly, amidst products both smugly literate and earnestly aspirational, a large Downton Abbey spread features a large cornucopia of goods we agree are the worst: lace-edged nightgowns, plated mirrors and hairbrushes, imitation jewelry, and DVD box sets detailing life in manor houses. “These are so horrible,” we whisper, “they aren’t even funny.”

The consumer of these Downton baubles, the glittering imitation brooches—she is everything I tried not to be as a young woman. When you are a girl and a bookworm, choices can feel limited.

Indeed, I still feel the limited possibilities for female identification whenever I watch a television show on which more than one woman appears. On the one hand, shows that pass the Bechdel test by presenting women with interests — as opposed to the singular “hot girl” amongst the boys — seem admirable, but I still feel the pressure of the typological when presented with a range of women: Are you a Carrie or a Samantha, a Marnie or a Shoshanna, a Lady Mary or, God forbid, a Lady Edith?

As a bookish girl, seeking others like me—readers of a serious sort—I was dismayed by the stereotype that came into focus: She loved kittens, wore dowdy pastels, ran to the mousy, would never be cool, never seem sexy or edgy. She was the girl who thought it would be fun to go to high tea. In my mind, there was one source and one icon to blame for the image of the female reader that so haunted me: England, and Jane Austen’s England in particular.

I became a student of American literature; like my country, I was too young and without enough of a sense of history to have paid much attention to either the cool or the ugly roughness that both had deep roots in England, or the pervasive and embarrassing middle-classness that was part of being an American. Instead, England remained to me the dreamland of girls who would never date.

My problem with England was a part of the sexually-anxious narcissism that accompanied my teens and twenties, so desperate was I to roll with the boys, to drink with the boys, and, once a literature major, to read with the boys: whether Palahniuk’s Fight Club, which was inspiring theme nights at the alternative frat—all whisky, Marlboro reds, and sloppy, scrambling boxing—, the strange macho sexuality of Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, or David Foster Wallace’s threatening challenge to all my would-be novelist friends. I remember people whispering intensely about Burroughs. Recently, novelist Claire Vaye Watkins has written about pandering to male writers through the tough, heartless, and heartbreaking prose of her short story collection. I see this period of my reading similarly, going shot-for-shot with the boys. But I wanted to be cool. American, edgy and cool.

This American cool continues, I think, in our recent prestige television, which offers bad boys you want to root for, the likes of Tony Soprano, Don Draper, and Walter White.

I still sometimes visit with American bad boys; I write about and teach the cruel works of Nathanael West, Fitzgerald’s more cynical friend. But as I’ve aged, I find that I have less patience for them. They can be a fling, but not my constant companions. Especially when the little things of my life seem hard and the big things of the world seem even harder, I want to return again to the coziness that was my youthful idea of England. And maybe this is true of the millions of other Americans who turned off HBO and tuned in to public television; after trying so hard to be crass and edgy, perhaps we do want to be that kind of girl after all.

What is it that we Americans want from the English? We want them to be vaguely like us, but better: we see them as politer and fancier, but we also like to think we’re more democratic, not so snotty. We also want not to have to know too much about the differences. Tea and knights, yes. Elaborate details about entailment, no, as the differences between the PBS and BBC explanations of the family’s wealth indicate.

We Americans see England as fundamentally belonging to the past, and thus soft and rosy. When my husband’s friend from London visited us in Nashville, the debutants were no match for him, so taken were they by his accent. The cost for him came in the form of bewildering conversations about jousting and whether “y’all have gyms there” and the terrible imitations into which the women slipped when the bourbon was flowing.

My sister’s English accent is also bad, somewhere between Foghorn Leghorn and Eliza Doolittle. It is also identical to the accent she tried when I moved to Nashville. I remember an early phone call home during which she filled me in on the day’s business. She’d been out shopping: “I went to Target; wait, do you have Target there?” Her view of the South is not unlike the debutant’s view of England, a place distant spatially and perhaps temporally as well. My current students in Mountain West feel similarly; they explain to me that they could never go to the South because they are Mexican. Meanwhile, my Anglo students refer to the rapidly gentrifying Hispanic neighborhood in town as “sketchy,” “the ghetto.”

My sister’s bad accent isn’t unique. We all have them. In a theater class at my arts magnet high school we memorized a little poem to practice the two relevant English accents: high-class and Cockney. A room of fifteen-year-olds, we chanted together, “If to hoot and to toot a Hottentot tot were taught by a Hottentot tutor, should the tutor get hot if the Hottentot tot should hoot and toot at the tutor?”

Not high-class, working-class, or English, we middle-class white American children—progeny of good liberal parents committed to public school education, if not neighborhood schools—happily swallowed our “Hs” and gulped out the bit of nonsense, so far from our knowing as to be scrubbed clean of racism’s taint. With our sense of Englishness as accent, and feelings of Africa and Europe as far in time and space, the little rhyme seemed to have nothing to do with our sense of racism as a real and pressing American problem.

The vagueness of Anglophilia is, I think, at least part of why the series’ second half felt like such a betrayal. Belonging too much to the world of problems Americans consider “the real,” the rape of Anna left a bitter taste that lingered, curdling our feelings about the series.

With the exception of that troublesome rape, Downton has offered the coziness that is the American idea of Englishness, the one I once rejected but now seek. As a new mother, I gaze longingly at the teas in the library during which the nanny parades by babies in sailor suits and then sweeps them neatly away, leaving their parents to drink and chat. My Anglophilia, you see, is not just about class as well as cozyness—the upper-class comfort and self-assuredness towards which we in the American middle class doggedly strain.

My embarrassment at retaining an idiot Anglophilia is somewhat assuaged by the knowledge that my American ancestors have been similarly foolish and aspirational in their views. In her book Anglophilia: Deference, Devotion, and Antebellum America, scholar Eliza Tamarkin reminds us that even way back when, in what my students would call the olden days, “Anglophilia [was] about paying respects to the symbolic value of England.” Among the more bizarre aspects of antebellum Anglophilia was the abolitionist argument that the English had done away with slavery because it didn’t fit with their overwhelming politeness. Owning people simply wasn’t seemly.

Politeness and impropriety are similarly behavioral big tents in Downton, covering all manner of progressive and regressive attitudes. Rapes, murders, blackmailing, and defections aside, on Downton, breaking with good manners is the clearest marker that a character is a baddie.

In the fifth season alone impoliteness covers, among other social failings, class snobbery (the aristocratic Merton boys), a genocidal rising power (Herr Hitler and his brown shirts, who will be revealed as the killers of Edith’s Michael, described in the show as beer hall unruliness), strident socialism (Miss Bunting), being a grouchy sad sack (Princess Kuragin), abuse of servants (Lord Sinderby), and anti-Semitism (Lady Flintshire, the Mertons again—naughty boys, those). Interestingly, the Dowager’s old flame Prince Kuragin also appears guilty of anti-Semitism and proximity to the genocidal murder of the pogroms when he bursts out at cousin Rose’s Jewish love interest, “you’re no Russian;” however, the show doesn’t present the outburst as something to hold against the man, perhaps because the transgression occurs in a soup kitchen, rather than a drawing room or library.

To be a hero, then, is to make others feel comfortable, to ease their embarrassment and smooth the way. A phrase I’ve learned to love from the show, “shall we go through?,” often comes from the wonderful Cora, the American matriarch committed to living lightly and lovingly, for whom guiding family and guests politely from potentially awkward conversation to pleasantly formal dining and drinking appears a life’s work.

“Shall we go through?” The show goes through with amazing rapidity, throwing forward plot twist after plot twist, the bulk of which are resolved neatly by banishing a rude interloper from the great house, or easing over unpleasantness, as when Cousin Rose pretends that her father-in-law’s mistress is an old friend, thus explaining away the uninvited guest. When the housekeeper Mrs. Hughes confesses to Mr. Carson that she has no money to retire with him because she’s been paying for her mentally disabled sister’s institutionalization, she worries, “Oh no, now I’ve embarrassed you.”

Coming from a nation with only loosely codified manners—which we occasionally boast of and are only occasionally shamed by—I find myself fascinated by a world in which all errors, all crises, all sins might be so beautifully papered over. Or, to put it otherwise, I long for a world in which I’ve been taught to behave beautifully and this beautiful behavior means that I am good.

This, too, as our own new rich fill TV screens: whether real housewives, basketball WAGs, or Kardashians, the idea of England as cozy past when people were polite stands as contrast. As does Kate Middleton, whose big shiny teeth and big shiny hair and tiny formal hats and tiny, tidy pregnancies make her a simulacrum of a princess. So too, The Great British Baking Show, which introduced Americans to a world of reality television in which no one declares “I’m not here to make friends” and the pastries are inscrutable. “Pudding,” “biscuit,” and “pie” take on strange new meanings.

The Anglophile’s imaginary England is a kind of mirror world. Like a grandfather—a relative in whom we see resemblance, but who clearly hails from another time. We feel affectionate toward him and maybe a little superior. Watching Downton, it’s lovely to see a plot in which the patriarch gets drunk, and rather than starting a brawl or bedding a scullery maid, he begins an awkward toast—a potential embarrassment that quick-witted chauffeur-turned-son-in-law Tom covers over by leading the household in rounds of “for he’s a jolly good fellow.” And the “good” characters’ foibles are so soft that it’s easy to feel a little wiser than those Granthams while also envying their outdated lifestyle.

A different program might show the wealthier classes’ predation upon the poor, but the violence within Downton Abbey remains reassuringly within class. And though we all hate the rape plot, what a relief that the storyline remains snugly downstairs. It allows the show’s commitment to the idea of noblesse oblige to remain an inviting temptation, leading to imaginings of how lovely we might behave if only we had a bit of nobility to be obliging with. Like Lady Sybil taking the red-haired maid under her wing. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a maid? Of course, one must not imagine being the maid.

With so much expansive politeness and correctness forming our idea of the English—“Keep Calm and Carry On!”—it’s surprising to hear missives from the real Britain, the one that exists in the now with us. The interviews during the Brexit vote give a nasty shock, as even good old England takes its place in a Europe increasingly Islamophobic and nativist. Grandfather has done worse than slip up and use the out of date “colored”—he’s said something truly awful and not cozy at all.

This is not how we like to think of our grandfathers. It’s not why we Americans turn our faces to gaze across the Atlantic. Instead, we wish to see the slightly fusty but well-meaning and well-mannered behavior of the Dowager Countess and Lord Grantham. Though they miss the old days (the first season features the Dowager cringing away from electric light), they are adaptable. Lord Grantham admits the nature of warfare has changed and nods to the feelings of his cook Mrs. Patmore, making a special monument off the beaten track for her nephew who was executed for defecting during the war.

I recently watched a bit of Manor House, a reality show in which modern people are cast as members of a grand Edwardian home. Some become the Lords and Ladies of the house; the tall and good-looking young man becomes First Footman, and the unlucky become scullery maids. The effects of a rigid upstairs-downstairs class system set in with breathtaking speed. After the initial meeting between the family and the staff, one of the maids confesses to the camera that though she knows her master and mistress are just normal twenty-first century people like herself, she hates them. In contrast, the mistress relates how lovely it is to be cared for; “it’s almost like I’ve slipped into childhood again,” she coos.

Such animosity between staff and family receives little screen time on Downton. Generally, class resentment is nothing but a misunderstanding, as when kitchen maid Daisy, who has been educated just to the point of dissatisfaction, misinterprets the characteristically vague kindness of Lady Grantham and tries to force a position for her tenant farmer father-in-law on the estate.

Instead, class hostility appears in the mouths of malefactors such as ladies’ maid O’Brien, a villain marked by truly terrible hair, or the blackmailing hotel maid who threatens Lady Mary and Lord Grantham with the prediction that her kind are coming up in the world. These instances of class outrage both come from maids and are directed at the eldest daughter Lady Mary for her sexual peccadillos, whether the ill-fated night with the exotic Mr. Pamook of the weak heart or her trial marriage hotel weekend with Tony Gillingham. Meantime, the matter of hygiene in manor houses’ downstairs extend to moral uprightness, to which the series nods, occasionally emphasizing the separate men’s and women’s quarters, but not to the near-prurient degree with which the sexual activity of maids would have been scrutinized, with the housekeeper examining their sanitary belts for evidence that the staff was staying chaste and not getting in the family way.

What comfort, then, in Downton’s somewhat relaxed morality. “We’re all becoming so modern!,” is a constant refrain. Lord Grantham, bless his ulcerous Lordship—what won’t he accept under the name of being a good host? He oversees one daughter’s marriage to a chauffeur, one daughter’s love child entering the household, and one daughter’s blackmail for her sexual intrepidness---not to mention his gay footman and multiply–murder-accused valet Mr. Bates. Downton is what Americans want from their betters, it’s what we see in the photographs of celebrities shopping at Trader Joes, playing on the beach with their children—Stars! They’re Just Like Us!! They are better looking, go on better vacations, and rich, but they use detergent!!! With Downton, we peek in on the nobility and see they make mistakes! Like us!

And I must admit, the more tired I am; the more panicked I feel as I forget to put sunscreen on the baby or to provide the daycare enough steamed finger foods diced into ¼ inch pieces; the more I long for time to work rather than time to spend with my husband and child; or the more I wish to spend time at home and quit my job, filled as it is with student emails and meetings; the more, stupidly and against what I know, I hunger for Downton.

The light touch of the series which makes it all come out right in the end—the deaths, the war, the murders, and yes, even the rape—it’s a warm blanket that feels wholesome even when that niggling voice reminds me of its near offensive flimsiness. It’s best not to think too seriously about the show. One is bound to have an unpleasant realization, like learning that eating bran muffins is just having unfrosted cupcakes for breakfast.

I recently heard the women of Another Round explain that only white people enjoy the “what past decade would you have rather lived in?” hypothetical. I get what they’re saying—and this is also Downton’s frivolous genius. Polite, like the Abbey’s denizens, the show doesn’t remind us of the footmen’s and maids’ more unpleasant tasks—the emptying of chamber pots, the pulling threads of hair from brushes to build elaborate false pieces—or that a hallboy gets his name because he has no room, and in fact sleeps in the hall. We don’t miss this granular detail because it’s not Daisy or Mrs. Patmore, or even good Anna, with whom the show means us to feel a likeness. We who play the game of transporting ourselves backwards through time don’t make that journey to light the morning fires for the big house or to do other people’s dishes. No, as we traverse the decades, running them backward, it’s the three lovely sisters we imagine as our kin and precursors.

Now I am mistress of my own house. (Lord Grantham, I too have a sweet old dog and I am sorry about Isis.) And I am, though I am loathe to write the phrase, its debunking as much a cliché now as its invocation, “having it all.” And my response to middle class life, motherhood, work, homeownership, marriage, is a low level panic I feel running up my spine, a fit on the verge of spilling out that is my constant companion, babyish and humiliating: But who is going to take care of meee?

And so, like many others of the American middle class, I fantasize about Downton. Together, America and I are over being cool and uncomfortable. We want to be cozy and rich. We want to turn on our TVs, gaze upon all that polished brass, and not think too hard about who is doing the polishing.

3 notes

·

View notes