#examining bias in clinical studies

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

saw that there was a video on tiktok circulating about what people even do with womens studies degrees and I saw a nice little rebuttal video that gave a syllabus list and that’s really nice and informative and all but back to the point there are real jobs that are super important that people can do with humanities degrees and part of fighting the backlash against them is acknowledging they exist

#I mean in a capitalist sense sociology psychology etc are super useful when you’re trying to sell people shit#but like a good chunk of women’s studies is devoted to the political and medical sphere#everything from setting up workplace policies (yes HR more legal)#to studying pay disparities#examining bias in clinical studies#plus there’s the whole research field of doing studies into gender#and the combination of medicine and law like studying anti choice laws etc etc#there are people who do all this shit for a living and it’s all legitimate work

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Park Jongseong (Part One)

Author’s Note: Mayhaps, this is a long one. So, it might come in 3 parts. Let me know what you think! DON’T COPY MY WORKS ANYWHERE.

CEO! Jay x Estranged Wife! Black Reader

Synopsis: A one-night stand with a handsome CEO leads to an unexpected derailment in your life plans.

Content: Angst, talks of miscarriage, depictions of depression, bullying, neglect, pregnant reader, motherhood, smut, autistic child, ghosted friendships, Jay’s mother reaaaalllllyyyy needs to get a life, eventual happy ending

Word Count: 3.0k

Pt. 2

Obtaining a practicing license was no easy feat. It required long, grueling hours of studying and hard work for you to succeed. You had graduated from an accredited university with a doctoral degree in veterinary medicine. Then you had to pass the national assessment exam to even be eligible for a license. After long, countless nights with no sleep, you had passed that too. It was challenging, of course it was. People warned that it wouldn’t be easy. Then came the state requirements for licensure. And that was where the trouble began.

Some regional areas required additional examination to assess your clinical skills and make sure you were up to standard according to their practices. It’s not like it was unexpected. You knew this. But being blindsided by whatever the fuck was going on with the state board was not on your to-do-list. The people you had to deal with had a severe case of stick up ass syndrome. The smug bastards wouldn’t accept your scores. You had tried to turn in your application and exams numerous times. Each time, it was denied. You couldn’t even understand why it kept getting denied. They never quite specified in a way that made sense. So you went to handle business in person.

When you inquired about the dispute, the jackass behind the window just smirked and stated, “You just aren’t… up to our standards.” Application rejected. And you knew what he had meant, the harsh snicker of his colleague resounding in your ears. They held bias against your racial background. You were no stranger to looks of displeasure due to your race. While blatant racism angered you to high hell, sneaky discriminatory antics pissed you off further.

Where did people get the nerve to judge your capabilities, or character, based on the color of your skin? As if they themselves were any better. But it’s like your grandmother always said, right? “You have to work twice as hard to be considered half as good.” She was right. Not to worry though. You would hold your head up high walking out of this office, and best believe these people will hear a formal complaint from you. Were you going to file a discriminatory charge with the state? Absolutely. But for now, it was water off a duck’s back. No matter what, you would stay afloat.

Later that night, you would go out with your friends to let off steam. And that would be the night you meet him.

It had been completely coincidental. You were dancing with your girls when you stumbled your way to the bar for another drink. Tangerine whiskey sour. Your favorite. Apparently his too. From what you remember, he had been sitting in a private booth with friends getting drunk off the loss of his fiance. Apparently, she cheated and high tailed it out of there without so much as a single note. She just left the engagement ring sitting on the nightstand. And that was it. He had been nursing a broken heart. How did you find yourself privy to this information? He told you.

You had ordered your fifth whiskey sour, mistakenly picking up his when the bartender brought it out. It was no biggie to him though. Ever the gentleman, he let you have it as he waited for the one that was supposed to be yours. Intrigued by his sweet demeanor, you stood and chatted with him. It was the least you could do for accidentally stealing his drink. He just laughed though; he really didn’t mind. And that’s how you got to know businessman Park Jongseong. Though his friends call him Jay.

And heartbroken Jay, drunk out of his mind, let his friends convince him that the cure to any heart related ailment was finding somebody to sleep with. There you stood, laughing at his jokes, delighted at his humor and sympathetic at his loss. He was enamored with you. Your intellect shined in conversation. And he was absolutely obsessed with your legs in that dress. So, he took you to a five-star hotel, a deluxe suite. He had a membership. There, he worships your body. All. Night. Long. Because nothing was as poetic as physical intimacy to him. He knew exactly what he was doing. With his fingers, tongue, and dick. The whole nine yards really. Then the next morning came, and with it came the embarrassment of letting yourself loose to such an extent. So, with tail tucked between your legs in shame, you truck it out of there before he wakes.

Though you tried to erase the encounter from memory, the sinful nature of your lustful thoughts kept you craving for the ghost of his touch. Damn, he was a great lover. And his greatness continued to outdo itself weeks later when you encounter an even greater conundrum. Because there on your bathroom counter glaring at you in horrifyingly pink lines, are the revelations of several pregnancy tests.

All positive.

Your life felt like it was over. How could you possibly be pregnant at a time like this? You were still trying to obtain your license, fighting against a system hoping to oppress you. You had barely started your career. What even happened? The two of you had been careful, right? Maybe the condom broke. Or maybe somewhere around round three the two of you simply let that layer of protection slip. Either way, consequence was staring you in the face. Park Jongseong. You remembered the man alright. And you remembered the business card he gave you too. Tucked carefully in the seams of your wallet. Hidden away as a token of that sensual night. So you use it.

Calling the number on the card was simple. Getting a proper response was not. On the other end of the line, a woman answers the phone. “State your business.” Bluntly formal. Okay. No biggie, probably his secretary. But when she starts giving you the third degree, wondering how you obtained this personal number, the claws are ready to come out. “Don’t call this number anymore unless you have business to tend to.” Then the heifer hangs up mid call.

Which brings you to the lobby of Park Enterprises. The place is bustling with ambition and visionary prowess. Various displays repeat videos on loop. Showcasing the fundamental values and mission of his company. His entire business was founded on the principle of sustainable urban development to mitigate the effects of climate change. Impressive and smart. You suppose he wasn’t only well-endowed between his legs. But while that was impressive, larger issues were at stake. Like your lack of proper protection during sex. Shaking yourself from the lustful thought, you refocus on the objective.

“How can I help you?” The chipper, young woman at the front desk questions. “I’m here to see Park Jongseong.”

“What business do you have with him?” She continues typing away as if multitasking were a part of the job description.

“It’s kind of a private matter.” She pauses and properly looks at you. You know you aren’t dressed the part for a corporate environment, wild curls framing your face, vibrant yellow crocs paired with baggy sweats, forest green tote bag slung over your shoulder with a loose sweatshirt hanging haphazardly from your frame. You look like you just threw your clothes together. And in your rush to get here, you technically did. “Do you have an appointment?” Her eyebrow quirks.

You know she’s just trying to do her job. But you can tell by the slight lift at the corner of her lip that she already knows the answer to that question. Still, you push on. You’ve got better things to do than stand here all day debating about appointments. “Not necessarily. But he did give me this in case I ever needed to get in touch with him.” You pull the business card from your bag and slide it over the counter to her. She regards it impassively before a look of surprise dons her face. Then, like magic, she is quickly picking up her phone and calling a line. Guess that did the trick, you thought. You grab the card and slide it in your pocket.

You don’t pick up much of the conversation she is having with whoever is on the line. All you hear is a chorus of “Yes sir’s” and “absolutely’s” before she is hanging up. She regards you with a look of curiosity before snapping out of her inquisitive gaze. “Secretary Kim Yeonmi has stepped out, but Mr. Park is upstairs and waiting. Floor 20. The elevators are that way.” Then just like that, her attention has shifted back onto the work she was tending to prior. Dismissed, you slowly make your way in the direction of the elevators. Butterflies swarm dangerously in the pit of your stomach. This very important man took you for a wild ride several weeks ago. And now you are catapulting back into his life with life changing news. Nervousness was an understatement.

You deliberate in the elevator the entire way up. It’s as if the universe is conspiring against you to speed things up for you to meet your fate. Because all too soon, the elevator dings, and you are stepping out of the metal box. Destiny beyond its doors. Everything about Park Enterprises is sleek. There’s a clean look to the environment. Black and white color scheme mixed with accents of mahogany wooden furniture. Modern regality permeates the atmosphere. The design did well to mimic his personality. Neat, well-kempt, simple, and sensible.

It was something you had noticed about him when you first met. Even in his drunken stupor, he carried a quality of elegant control. Which is a reason it excited you to see him let loose in the bedroom. Shaking those lustful thoughts once more, you cross the chasm between your present and future. Walking past the vacant secretary desk, you stand at a pair of closed mahogany doors. Hesitantly, you knock.

A few seconds of silence before the words, “Come in,” echo beyond the doors. That’s how you meet Jongseong again. Standing in front of his desk, in a heath gray suit with a black undershirt, is the man of your recurring fantasies. His jaw is tight, hands in his pockets. Body language seemingly tense. Rightfully so. This is an unexpected encounter. You gather your bearings to drop this bombshell.

Just as you cross the threshold, “What’s the urgency of the matter for you to go and brandish a card that doesn’t belong to you?” What… was that?

Baffled by his direct line of questioning, you stop shy of your destination. “Excuse me?”

“The card.” He acknowledges the nature of it with a nod. “It’s only given out to personal business associates and people I deem of importance.” Wow. This Park Jongseong was different from the one who let loose with a few drinks. He was rude and blunt. Maybe his ex-fiancé really did do a number on him.

“This card was specifically given to me by you.” He hums.

“Interesting.” And he says it like he doesn’t believe you at all. Which is strange considering he, in fact, did give it to you.

“Do you… not remember Club Daydream a month ago? We met at the bar. I mistakenly took your whiskey sour. Tangerine.”

He shrugs his shoulders with disinterest. “Vaguely. I’ve met a lot of women in the past few weeks.”

You continue, trying to drown out the thought of what that meant. “Okay… um. You took me to XO hotel after giving me your business card at the bar. You talked to me about your ex—”

“Stop.” He interjects, hand held up as a visual sign of his interruption. “Don’t speak about her like you know anything.” From the heat of his voice, it is clear he is still disgruntled from the nature of that relationship.

“Sorry,” You stutter, mind jumbled from the whirlwind of confusion. This version of Jay was giving you whiplash from the one you experienced. “I didn’t mean to overstep—”

“But you did, and I’m starting to think this conversation is useless. Get to the point.”

Scoffing, your frustration begins to rear its ugly head. “Well, I’m trying—”

“Try harder. I have a 4 o’clock meeting—”

“I’m pregnant,” you blurt out. “A few weeks along. It lines up perfectly with the timeframe of that night.”

“How do I know you haven’t slept with anyone else?” Ouch. As much as you understood his logic, it still offended you to know he could accuse you of that so easily. “I’ll try not to be offended by what you just said. But if you must know, I don’t typically sleep around. I’m just starting out in my career and don’t have time for relationships or children. Besides, you’re the first guy I’ve slept with in a long time.” He observes you for a moment, taking in your body language.

“And what about the pregnancy test? Where is it? Have you taken more than one? Have you gotten a professional opinion?”

Overwhelmed, you step back a little bit at the rapid fire questioning. Reading the room, he pauses once again to look at you. Reaching into your bag, you pull out four pregnancy tests. “I’ve taken four of these at home. All read positive.” You hold them out in the space between you two. Pushing off the desk he began to lean on mid conversation, he steps closer to observe the tests. As proof of your midnight tryst, 8 pink lines stare back at him. He curses softly under his breath. “Let’s say, hypothetically, the baby is mine.” You bristle at the skepticism lacing his voice. “Why haven’t you gone to a professional to confirm it? Sometimes pregnancy tests can be faulty.”

“By giving four false positives?” Bafflement was an understatement.

“I don’t know how these things work,” he hisses. “But what I do know is you need a professional opinion. Why didn’t you go to one to confirm this?”

“Because I literally just found out and didn’t want to freak out alone.” You rebut.

He chuckles under his breath in disbelief, then looks away. Sucking his teeth in frustration, he makes his way over to his desk where he picks up the phone. “Secretary Kim, cancel the rest of my meetings for the day.” Ah, he was calling the secretary who stepped out to run errands. There seems to be dialogue on the other side of the receiver. “Just do it.” He states, before hanging up the phone with finality. Damn, that was kind of hot. His eyes snap back to you. You stiffen at attention. His gaze sweeps over your form once more, before he sighs. “Let’s go. I’ll take you to my family doctor.”

Forty-five minutes later finds you in the care of Jay’s family doctor, Paik Sunjae. His results confirm without a shadow of a doubt that you are pregnant. The look on the young CEO’s face is unreadable underneath the fluorescent lighting. He thanks the doctor and gathers himself before walking out of the office. Grabbing your things, you swiftly follow after him.

In the car, you both sit in silence before you break it. “Believe me now?” The man in question shuts his eyes briefly, taking a deep breath to repress the negative emotion oozing out of him. “If the timeline of events is as you say, then the child has to be mine. Meaning I now have to take full responsibility for you both.”

“Well, you don’t necessarily have to. I didn’t really intend on being a mother.” At the revelation of your words, he turns to look at you. “What do you mean?”

“I mean I’m still working on obtaining my practicing license. Being a mother was not on my agenda at such a young age. You didn’t even seem happy about the baby. So, why should I sacrifice what I worked hard for?”

Immediately, he sits at attention. “You are not getting rid of my baby.” The conviction in his voice added more layers of confusion to the man you were getting to know. “I… didn’t intend to get rid of the child. What I meant was that we can take responsibility together up to a certain point. Once the baby is born, I can give them to you and move on with my life.”

“No. If we do this, we do it my way. I wasn’t raised to abandon the mother of my child. That being said, you’re moving in with me. And in a few days time, I’ll finalize our marriage certificate.”

“What?!” You exclaim. “Did you not hear what I just said? I’m too young to be a mother and my career is already on the line. Why should I pause that for you? And who said anything about marriage? We hardly know each other, and what little I do know about you isn’t exactly pleasant at the moment.” The man in front of you had done a 180 shift from the charming gentleman at the bar. And now he was demanding you marry him for the baby?

“Regardless of what you think you know about me, having a child out of wedlock is a huge scandal. One I’d like to prevent from reaching the media. Besides, a child needs its mother. I can’t care for an infant by myself. Since we created the kid together, we do the leg work together. My home and my resources are open for you to oversee proper nutrition and care during pregnancy. Being my wife should be seen as a perk, not a chore. Plenty of women would consider themselves lucky for that spot.”

“So call them since you wanna be braggadocious.”

He rolls his eyes with a smirk at the sarcasm dripping in your voice. “Trust me, this arrangement is for the best. You’ll see.”

A week later you were officially married.

#enhypen#enhypen x reader#enhypen angst#enhypen jay#kpop x black reader#x black reader#enhypen imagines#enhypen scenarios#enhypen x black reader#enhyphen x reader#enhypen au#jay x reader#enhypen fanfiction#enha x reader#enha imagines#enha#park jongseong#park jongseong fic

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

While the Cass Review has been presented by the U.K. media, politicians and some prominent doctors as a triumph of objective inquiry, its most controversial recommendations are based on prejudice rather than evidence. Instead of helping young people, the review has caused enormous harm to children and their families, to democratic discourse and to wider principles of scientific endeavour. There is an urgent need to critically examine the actual context and findings of the report. Since its 2020 inception, the Cass Review’s anti-trans credentials have been clear. It explicitly excluded trans people from key roles in research, analysis and oversight of the project, while sidelining most practitioners with experience in trans health care. The project centered and sympathized with anti-trans voices, including professionals who deny the very existence of trans children. Former U.K. minister for women and equalities Kemi Badenoch, who has a history of hostility toward trans people even though her role was to promote equality within the government, boasted that the Cass Review was only possible because of her active involvement. The methodology underpinning the Cass Review has been extensively criticized by medical experts and academics from a range of disciplines. Criticism has focused especially on the effect of bias on the Cass approach, double standards in the interpretation of data, substandard scientific rigor, methodological flaws and a failure to properly substantiate claims. For example, although the existing literature reports a wide range of important benefits of social transition and no credible evidence of harm, the Cass Review cautions against it. The review also dismisses substantial documented benefits of adolescent medical transition as underevidenced while highlighting risks based on evidence of significantly worse quality. A warning about impaired brain maturation, for instance, cites a single, very short speculative paper that in turn rests on one experimental study with female mice. Meanwhile extensive qualitative data and clinical consensus are almost entirely ignored. These issues help explain why the Cass recommendations differ from previous academic reviews and expert guidance from major medical organisations such as the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) and the American Academy of Pediatrics. WPATH’s experts themselves highlight the Cass report’s “selective and inconsistent use of evidence,” with recommendations that “often do not follow from the data presented in the systematic reviews.” Leading specialists in transgender medical care from the U.S. and Australia emphasize that “the Review obscures key findings, misrepresents its own data, and is rife with misapplications of the scientific method.” For instance, the Cass report warns that an “exponential change in referrals” to England’s child and adolescent gender clinic during the 2010s is “very much faster than would be expected.” But this increase has not been exponential, and the maximum 5,000 referrals it notes in 2021 represents a very small proportion of the 44,000 trans adolescents in the U.K. estimated from 2021 census data.

7 August 2024

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Last month, the UK’s four-year-long review of medical interventions for transgender youth was published. The Cass Review, named after Hilary Cass, a retired pediatrician appointed by the National Health Service to lead the effort, found that “there is not a reliable evidence base” for gender-affirming medicine. As a result, the report concludes, trans minors should generally not be able to access hormone blockers or hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and instead should seek psychotherapy. While the review does not ban trans medical care, it comes concurrently with the NHS heavily restricting puberty blockers for trans youth.

The conclusions of the Cass Review differ from mainstream standards of care in the United States, which recommend medical interventions like blockers and HRT under certain circumstances and are informed by dozens of studies and backed by leading medical associations. The Cass Review won’t have an immediate impact on how gender medicine is practiced in the United States, but both Europe’s “gender critical” movement and the anti-trans movement here in the US cited the report as a win, claiming it is the proof they need to limit medical care for trans youth globally. Notable anti-trans group the Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine called the report “a historic document the significance of which cannot be overstated,” and argued that “it now appears indisputable that the arc of history has bent in the direction of reversal of gender-affirming care worldwide.”

Most media coverage of the report has been positive. But by and large that coverage has failed to examine extensive critiques from experts in the US and elsewhere. Research and clinical experts I interviewed explained that the Cass Review has several shortcomings that call into question many of its findings, especially around the quality of research on gender medicine. They also question the credibility and bias underpinning the review. I spoke with four clinical and research experts in pediatric medicine for gender-diverse youth to dive into the criticisms.

“I urge readers of the Cass Review to exercise caution,” said Dr. Jack Turban, director of the gender psychiatry program at the University of California, San Francisco and author of the forthcoming book Free to Be: Understanding Kids & Gender Identity."

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Editor's note:This is the first blog in our series that examines how social determinants influence gender biases in public health research, menstrual hygiene product development, and women’s health outcomes.

Worldwide, over 100 million women use tampons every day as they are the most popular form of menstrual products. U.S. women spent approximately $1 billion from 2016 to 2021 on tampons, and 22% to 86% of those who menstruate use them during their cycles, with adolescent girls and young adults preferring them. Tampons and pads are the most practical and common option for those who are working and have limited funds. Yet, a recent pilot study exposed concerning amounts of lead, arsenic, and toxic chemicals in tampons: 30 different tampons from 14 brands were evaluated for 16 different metal(loid)s, and tests indicated that all 16 metal(loid)s were detected in all different samples. This news comes as quite a shock to women who use these products. It raises many concerns and questions for those who do not have other viable options when they menstruate. We explore some of the major questions and concerns regarding the products on the market and their potential to increase the risk of exposure to harmful contaminants. It is clear that beyond this pilot study, further research is required to understand the potential health challenges.

Unpacking the potential risks for those who use menstrual products

Measurable concentrations of lead and arsenic in tampons are deeply concerning given how toxic they are. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies lead as a major public health concern with no known safe exposure level. Arsenic can lead to several health issues such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. There are three ways in which these metal(loid)s can be introduced into the product: 1) from the raw materials that absorbed the soil and air, like the cotton used in the absorbent core; 2) contamination from water during the manufacturing process; and 3) intentionally being added during the manufacturing process for certain purposes. No matter how these metal(loid)s are introduced into the product, the pilot study stresses that further research must be done to explore the consequences of vaginally absorbed chemicals given the direct line to the circulatory system.

On an institutional level, the public health system has historically been biased toward the male perspective, essentially excluding research related to women’s health. In 1977, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended that women of childbearing age should be excluded from clinical research. Because of this gendered bias, many women now experience delayed diagnoses, misdiagnoses, and suffer more adverse drug effects; eight out of 10 of the drugs removed from U.S. markets from 1997 to 2000 were almost exclusively due to the risk to women. In 1989, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) amended its policy to include women and minorities in research studies, but it wasn’t until 1993 that this policy became federal law in the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993. Then, in 2016, the NIH implemented a policy requiring the consideration of sex as a biological variable in research.

Historically, women haven’t been in control of the various industries that support their unique health needs and develop products that allow them to manage their health in safe ways. In spite of this, women-owned businesses have increased over time, with many of them supporting a range of products, services, and health and child care needs. Changes in these industries can lead to a better understanding of how certain products aid or impede women’s health trajectories.

Racialized and gendered bias in health research

The life expectancy of women continues to be higher than men’s. That does not suggest there has been universal nor equitable support for women’s health issues and women’s health care. Black women are three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related issues. They also experience racism and differential treatment in health care and social service settings. This reality becomes starker when stigma and bias influence negative behaviors toward Black women and other women of color, and socioeconomic status limits access to preventative care, follow-up care, and other services and resources.

Toxic menstrual products are just the tip of the iceberg for gender bias in health research. Gendered bias extends into how health care professionals evaluate men and women differently based on the stereotypical ideas of the gender binary. This results in those who are perceived as women receiving fewer diagnoses and treatments than men with similar conditions, as well as doctors interpreting women’s pain as stemming from emotional challenges rather than anything physical. In a study comparing a patient’s pain rating with an observer’s rating, women’s pain was consistently underestimated while men’s pain was overestimated. Women’s pain is often disregarded or minimized by health care professionals, as they often view it as nothing more than an emotional exaggeration or are quick to blame any physical pain on stress. This has led to a pain gap in which women with true medical emergencies are pushed aside. For instance, the Journal of the American Heart Association reported that women with chest pain waited 29% longer to see a doctor in emergency rooms than men.

For people of color, especially Black women, the pain gap, as well as the gap in diagnoses and treatment, is exacerbated due to the intersectionality of gender, race, and the historical contexts of Black women’s health in America. Any analysis must consider the unique systemic levels of sexism and racism they face as being both Black and women. They face a multifaceted front of discrimination, sexism, and racism, in which doctors don’t believe their pain due to implicit biases against Black people—a dynamic that stems from slavery, during which it was common belief that Black people had a higher pain tolerance—and women. A study found that white medical students and residents believed at least one false biological difference between white and Black people and were thus more likely to underestimate a Black patient’s pain level.

Intersectionality, as well as sexism, further explains why medical students that believe in racial differences in pain tolerance are less likely to accurately provide treatment recommendations or pain medications. A Pew study found that 55% of Black people say they’ve had at least one negative experience with doctors, where they felt like they were treated with less respect than others and had to advocate for themselves to get proper care. Comparatively, 52% of younger Black women and 40% of older Black women felt the need to speak up to receive care, while only 29% of younger Black men and 36% of older Black men felt similarly. Particularly among Black women, 34% said their women’s health concerns or symptoms weren’t taken seriously by their health care providers. This even happened to Serena Williams!

Restructuring the health system

On Tuesday, September 11, 2024, the FDA announced they would investigate the toxic chemicals and metals in tampons as a result of the pilot study. This comes after public outcry and Senator Patty Murray’s (D-Wash.) letter to FDA Commissioner Robert M. Califf asking the agency to evaluate next steps to ensure the safety of tampons and menstrual products. In her letter, she specifically asks what the FDA has done so far in their evaluations and what requirements they have for testing these products, ensuring a modicum of accountability within this market. As of July 2024, the FDA classifies tampons as medical devices and does regulate their safety but only to an extent, with no requirements to test menstrual products for chemical contaminants (aside from making sure they do not contain pesticides or dioxin). The pilot study on tampons containing harmful metals was the first of its kind, which sheds light on how long women’s health has been neglected. Regulations requiring manufacturers to test metals in tampons need to be implemented, and future studies on the adverse health impacts of metals entering the bloodstream must be prioritized. The FDA investigation will hopefully be a step in the right direction toward implementing stricter regulations.

For too long, the health field has been saturated with studies by and for men. Women’s health, on the other hand, faces inadequate funding, a lack of consideration for women’s lived experiences, and the need for more women leading research teams investigating women’s health. Women, especially those who face economic and social disparities, have the capacity to break barriers and address real issues that impact millions of women each day but only if they are brought to the table. With structural change, we can address how women’s concerns are undermined and put forth efforts to determine new and effective measures for women’s health.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Originally posted Jan 2023.

The medical community and the media hang their hats on the use of ‘double-blind, placebo-controlled, peer-reviewed studies published in legacy journals such as The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) and the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). In a future substack, I will go into detail about the fallacies, and even the scam, of peer review and why it should not be held out as sacrosanct.

For today’s discussion, let’s examine why all vaccine research should be questioned. Yes, ALL of it. If you read enough studies, you’ll see the patterns described below. For this substack, I’ll use this study on the safety of hepatitis B vaccination in children in India as an example. The vaccine used, Revac-B, contained both 0.5mg of aluminum and 0.05 mg of thimerosal, considered to be safe.

1. Vaccine trials can be quite small and include only healthy children.

Every study begins with ‘selection criteria’ that describe including only healthy individuals. This is from the hepatitis B study example:

All 60 subjects included in the study were in good health and had a negative history of hematological, renal, hepatic, or allergic diseases. All were screened and found to have normal blood panels, including normal liver enzymes.

When a vaccine trial has been completed and the vaccine is approved for use by the FDA, the vaccine is recommended for ALL children, regardless of their health condition, family history, or genetics. In fact, the new shot is most ardently pushed on children with underlying health concerns, such as seizure disorders, cardiac anomalies, and conditions such as cystic fibrosis or Down’s syndrome. These children become the next round of experimentation because the vaccines were never tested for safety on these groups and others.

2. Vaccine studies follow side effects for a short period of time.

Most clinical trials monitor for side effects for a paltry 21 days, often less. In some studies, such as in the example we are using, children were monitored for 5 days by study monitors and 5 days by cards given to parents. If no reactions occur, the shot is deemed to be ‘safe.’

However, it can take weeks to months for immune and neurological complications to appear. These arbitrary deadlines, allowed by the FDA, prohibit making the connection between vaccines with chronic health disorders. If an illness emerges later, of course, the doctors will say it has nothing to do with the vaccine.

3. Most vaccine safety studies do not use a true placebo.

The gold standard in medical research is the "placebo-controlled" trial. A placebo is an inactive or inert substance, such as a sugar pill or a shot of saline. In the trial, the placebo is given to one group, while the treatment group is given the experimental product. The placebo arm is used to ‘blind’ the study so the investigator doesn’t know if the subject received the Real Thing or the Inert Substance to minimize interpretation bias.

When reading a published vaccine trial, the substance used as the placebo is often not identified; it is simply called ‘placebo.’ For example, in this study for a new hepatitis B vaccine to treat chronic hepatitis B, the word ‘placebo’ is used 22 times, but we don’t know what placebo was used.

And that’s a problem. The substance used as a ‘placebo’ is often not inert; it may even may be another vaccine. For example, I remember reading a study where the meningitis C vaccine was used as a placebo because it was considered to be non-immunogenic and non-reactive. Or, in the instance of the Gardasil (HPV) vaccine, the ‘placebo’ was an injection of aluminum.

All studies for the Gardasil vaccine were said to be placebo-controlled and the total population that received a placebo included 9,701 subjects. The placebo was an aluminum adjuvant in all studies except study 018 (pre-/adolescent safety study), which used a non-aluminum-containing placebo [and we don’t know what that placebo was]

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

[”the divided self”, r. d. laing]

she said the trouble was that she was not a real person; she was trying to become a person. there was no happiness in her life & she was trying to find happiness. she felt unreal & there was an invisible barrier between herself & others. she was empty & worthless. she was worried lest she was too destructive & was beginning to think it best not to touch anything in case she caused damage. she had a great deal to say about her mother. she was smothering her, she would not let her live, & she had never wanted her. since her mother was prompting her to have more friends, & to go out to dances, to wear pretty dresses, & so on, on the face of it these accusations seemed palpably absurd

however, the basic psychotic statement she made was that 'a child had been murdered'. she was rather vague about the details, but she said she had heard of this from the voice of her brother (she had no brother). she wondered, however, if this voice may not have been her own. the child was wearing her clothes when it was killed. the child could have been herself. she had been murdered either by herself or by her mother, she was not sure. she proposed to tell the police about it

much that Julie was saying when she was seventeen is familiar to us from the preceding pages. we can see the existential truth in her statements that she is not a person, that she is unreal, & we can understand what she was getting at when she said that she was trying to become a person, & how it may have come about that she felt at once so empty & so powerfully destructive. but beyond this point, her communications become 'parabolic'. her accusations against her mother, we suspect, must relate to her failure to become a person but they seem, on the surface, rather wild & far-fetched (see below). however, it is when she says that 'a child has been murdered' that one's common sense is asked to stretch further than it will go, & she is left alone in a world that no one will share

now, i shall want to examine the nature of the psychosis, which appeared to begin about the age of seventeen, & i think this can best be approached by first considering her life until then

Clinical Biography of a Schizophrenic

it is never easy to obtain an adequate account of a schizophrenic's early life. each investigation into the life of any single schizophrenic patient is a laborious piece of original research. it cannot be too strongly emphasized that a 'routine' or even a so-called dynamically orientated history obtained in the course of several interviews can give very little of the crucial information necessary for an existential analysis. in this particular case, i saw the mother once a week over a period of several months & interviewed (each on a number of occasions) her father, her sister, three years older, who was her only sibling, & her aunt (father's sister). however, no amount of fact-gathering is proof against bias. Searles (1958), for instance, is i think absolutely correct to emphasize the existence of positive feelings between the schizophrenic & his mother, a finding that has been singularly 'missed' by most other observers. i have no illusions that the present study is immune from bias which i cannot see

father, mother, sister, aunt were the effective personal world in which this patient grew up. it is the patient's life in her own interpersonal microcosmos that is the kernel of any psychiatric clinical biography. such clinical biography is therefore self-consciously limited in scope. the socio-economic factors of the larger community of which the patient's family is an integral part are not directly relevant to the subject matter that is our concern. this is not to say that such factors do not profoundly influence the nature of the family & hence of the patient. but, just as the cytologist puts, qua cytologist, his knowledge of macroanatomy in parentheses in his description of cellular phenomena, while at the same time being in possession of this knowledge, so we put the larger sociological issues in parentheses as not of direct & immediate relevance to the understanding of how this girl came to be psychotic. thus i think the clinical biography that i shall present could be of a working-class girl from Zurich, of a middle-class girl from Lincoln, or of a millionaire's daughter from Texas. very similar human possibilities arise in the inter-personal relationships of people as differently placed within society as these. i am, however, describing something that occurs in our twentieth-century Western world, & perhaps not, in quite the same terms, anywhere else. i do not know what are the essential features of this world that allow of such possibilities to arise. but we, as clinicians, must not forget that what goes on beyond our self-imposed horizons may make a great difference to the patterns to be made out within the boundaries of our clinical interpersonal microcosmos

i have felt it necessary to state this briefly here because i feel that clinical psychiatry in the West tends towards what a schizophrenic friend of mine called 'social gaucherie', whereas Soviet psychiatry seems to be rather gauche in the interpersonal sphere. although a clinical biography must, i believe, focus on the interpersonal sphere, this should be in such a way as not to be a closed system which excludes the relevance in principle of what one may temporarily place in parentheses for convenience

now, although each of the various people interviewed had his or her own point of view on Julie's life, they all agreed in seeing her life in three basic states or phases. namely, there was a time when,

the patient was a good, normal, healthy child; until she gradually began

to be bad, to do or say things that caused great distress, & which were on the whole 'put down' to naughtiness or badness, until

this went beyond all tolerable limits so that she could only be regarded as completely mad

once the parents 'knew' she was mad, they blamed themselves for not realizing it sooner. her mother said,

I was beginning to hate the terrible things she said to me, but then I saw she couldn't help it ... she was such a good girl. Then she started to say such awful things ... if only we had known. Were we wrong to think she was responsible for what she said? I knew she really could not have meant the awful things she said to me. In a way, I blame myself but, in a way, I'm glad that it was an illness after all, but if only I had not waited so long before I took her to a doctor.

what is meant precisely by good, bad, & mad we do not yet know. but we do now know a great deal. to begin with, as the parents remember it now, of course, Julie acted in such a way as to appear to her parents to be everything that was right. she was good, healthy, normal. then her behaviour changed so that she acted in terms of what all the significant others in her world unanimously agreed was 'bad' until, in a short while, she was 'mad'

this does not tell us anything about what the child did to be good, bad, or mad in her parents' eyes, but it does supply us with the important information that the original pattern of her actions was entirely in conformity with what her parents held to be good & praiseworthy. then, she was for a time 'bad', that is, those very things her parents most did not want to see her do or hear her say or to believe existed in her, she 'came out with'. we cannot at present say why this was so. but that she was capable of saying & doing such things was almost incredible to her parents. all that emerged was totally unsuspected. they tried at first to discount it, but as the offence grew they strove violently to repudiate it. it was a great relief, therefore, when, instead of saying that her mother wouldn't let her live, she said that her mother had murdered a child. then all could be forgiven. 'Poor Julie was ill. She was not responsible. How could I ever have believed for one moment that she meant what she said to me? I've always tried my best to be a good mother to her.' we shall have occasion to remember this last sentence

these three stages in the evolution of the idea of psychosis in members of a family occur very commonly. good - bad - mad. it is just as important to discover the way the people in the patient's world have regarded her behaviour as it is to have a history of her behaviour itself. i shall try to demonstrate this conclusively below, but at this point i would like to observe one important thing about the story of this girl as told me by her parents

they did not suppress facts or try to be misleading. both parents were anxious to be helpful & did not deliberately, on the whole, withhold information about actual facts. the significant thing was the way facts were discounted, or rather the way obvious possible implications in the facts were discounted or denied. we can probably best present a brief account of this girl's life by first grouping the events together within the parents' framework. my account is given predominantly in the mother's words

Phase I: A normal & good child Julie was never a demanding baby. she was weaned without difficulty. her mother had no bother with her from the day she took off nappies completely when she was fifteen months old. she was never 'a trouble'. she always did what she was told

these are the mother's basic generalizations in support of the view that Julie was always a 'good' child

now, this is the description of a child who has in some way never come alive: for a really alive baby is demanding, is a trouble, & by no means always does what she is told. it may well be that the baby was never as 'perfect' as the mother would like me to believe, but what is highly significant is that it is just this 'goodness' which is Mrs X's ideal of what perfection is in a baby. maybe this baby was not as 'perfect' as all that; maybe in maintaining this the mother is prompted by some apprehensiveness lest i blame her in some way. the crucial thing seems to me to be that Mrs X evidently takes just those things which i take to be expressions of an inner deadness in the child as expressions of the utmost goodness, health, normality. the significant point, therefore, if we are thinking not simply of the patient abstracted from her family, but rather of the whole family system of relationships of which Julie was a part, is not that her mother, father, aunt all describe an existentially dead child, but that none of the adults in her world know the difference between existential life & death. on the contrary, being existentially dead receives the highest commendation from them

let us consider each of the above statements of the mother in turn:

1. Julie was never a demanding baby. she never cried really for her feeds. she never sucked vigorously. she never finished a bottle. she was always 'whinie & girnie'; she did not put on weight very rapidly. 'She never wanted for anything but I felt she was never satisfied.'

here we have a description of a child whose oral hunger & greed have never found expression. instead of a healthy vigorous expression of instinct in lusty, excited crying, energetic suckling, emptying the bottle, followed by contented satiated sleep, she fretted continually, seemed hungry, yet, when presented with the bottle, sucked desultorily, & never satisfied herself. it is tempting to try to reconstruct these early experiences from the infant's point of view, but here i wish to restrict myself only to the observable facts as remembered by the mother after over twenty years, & to make our constructions from these alone

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did you know that psychological testing was once biased against Black individuals? Dr. Herman George Canady (1901–1970) was a pioneering psychologist who changed the game!

As a clinical and social psychologist, Dr. Canady was the first to study how the race of an examiner could impact the performance of Black students on IQ tests. His groundbreaking research highlighted racial bias in standardized testing and helped lay the foundation for fairer psychological assessments.

Beyond his research, he was a dedicated educator and mentor, training future Black psychologists at West Virginia State College. His work paved the way for equitable practices in psychology and education.

This Black History Month, we honor Dr. Canady's contributions to mental health and social justice!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

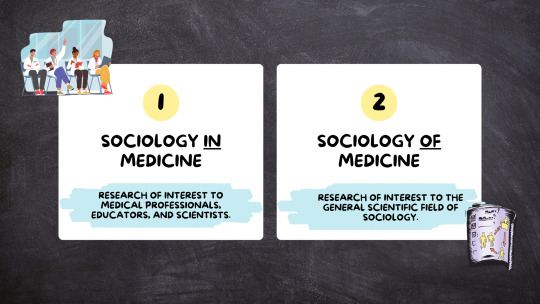

Compliance, per the two main approaches to medical sociology

Sociology in medicine is research that’s of interest to medical professionals, medical educators, medical scientists— things that are important to medicine as an institution.

Sociology of medicine tends to be research of interest to the general scientific field of sociology, not only sociologists who study matters of medicine, health, illness, healthcare, and disability. Importantly, it is not that medicine is simply disinterested in sociology of medicine, the institution of medicine sometimes has a vested interest in silencing or arguing against sociology of medicine. Sociology of medicine may not be useful to medical professionals, but if, for example, sociology of medicine is critiquing medical practice, as is often the case, it might move beyond useless to being perceived as offensive.

To further explore the difference between sociology in versus of medicine, let’s take the issue of compliance.

From the medical perspective, patient compliance is vital for successful medical practice and treatment. if your patient is not listening to you–for example, if they’re not taking their medication, and that medication is supposed to get them better, than you are going to have a much more difficult time treating that patient, and thus, a much harder time doing your job, than if the patient “complied” with your treatment plan. Same thing if your patient won’t have surgery. Well, if operating is the way that you do your job and the patient refuses, you cannot do your job as well. So, sociology in medicine would examine compliance with this medical perspective in mind. Sociology in medicine might investigate the barriers to patient compliance, and they might ask about these barriers in terms of patient behavior, asking something like "why are these patients non-compliant?" with the goal of identifying things that can be addressed to help patients better comply, so that medical professionals can have better chances of success when trying to do their jobs.

Now, moving to sociology of medicine—the greater field of sociology is interested in issues of power and inequality. When examining compliance in terms of power and inequality, we might look at something like physician control over patients, which would contribute to areas of sociology beyond medical sociology, such as the larger sociological literature on deviance and social control.

From this perspective, physicians offer something that patients cannot obtain on their own—prescription medications, surgery, imaging…these are all things that are considered both illegal and dangerous when obtained from non-credentialed entities. This means patients must be compliant to avoid severe consequences, like physical injury, disability, or even death. Healthcare providers hold power to help people feel better when they have few, if any, safe alternatives.

Instead of looking at compliance as inherently positive or necessary, we can critique the concept, and most importantly, the continued endorsement of compliance as “positive” and “necessary” by credentialed actors in medicine. So, sociology of medicine, similarly to sociology in medicine, may examine barriers to compliance, but because it does not assume compliance is necessary or helpful to the patient, it leaves room to explore the patient experience. Sociology of medicine can explore things like mistrust of medical professionals, experiences with bias and discrimination in the clinical encounter, and the patient’s understanding of a potential treatment as helpful versus their belief that the treatment is useless (independent of the science on said treatment’s effectiveness).

So, while sociology in medicine and sociology of medicine might both be interested in the question of “why do patients become noncompliant,” sociology in medicine might approach that question with the intent of identifying something that will lead to increased compliance, whereas sociology of medicine may approach the question in terms of medical harm, so not taking the assumption that compliance is positive, instead, taking the more skeptical view that compliance might be an exercise of power on the part of the healthcare provider over the patient and focusing on issues like the potential for patterns of exploitation and/or harm of certain groups of patients with shared characteristics. Sociology of medicine might ask whether healthcare providers, because they are powerful, are inherently good or right. Sociology in medicine would probably not ask this question at all, instead assuming the answer to be "yes"

youtube

#sociology#studyblr#phdblr#social science#medblr#health science#research#paradigm#medical sociology#sociology of medicine#sociology in medicine#compliance#power#inequality#deviance#social control#medical sociology 101#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Leor Sapir

Published: Nov 13, 2023

Few figures in the medical world generate more controversy than psychiatrist Jack Turban. An assistant professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, Turban is one of the leading figures promoting “gender-affirming care” in the United States. He is also regularly criticized for producing deeply flawed research and denying the significant rollback of youth gender transition in Europe.

The American Civil Liberties Union recently retained Turban as an expert witness—paying him $400 per hour—in its legal challenge to Idaho’s Vulnerable Child Protection Act, which restricts access to “gender-affirming” drugs and surgeries to adults only. On October 16, Turban submitted to a seven-hour deposition at the hands of John Ramer, an attorney with the law firm Cooper & Kirk, who is assisting Idaho in the litigation. In the course of the deposition, Turban revealed that, aside from churning out subpar research and misleading the public about scientific findings, he also appears not to grasp basic principles of evidence-based medicine.

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) refers to “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. . . . The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.” Because the expert opinion of doctors, even when guided by clinical experience, is vulnerable to bias, EBM “de-emphasizes intuition, unsystematic clinical experience, and pathophysiologic rationale as sufficient grounds for clinical decision making and stresses the examination of evidence from clinical research.” EBM thus represents an effort to make the practice of medicine more scientific, with the expectation that this will lead to better patient outcomes.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses sit at the top of the hierarchy of evidence in EBM. A key difference between the U.S. and European approaches to pediatric gender medicine is that European countries have changed their clinical guidelines in response to findings from systematic reviews. In the U.S., medical groups have either claimed that a systematic review “is not possible” (the World Professional Association for Transgender Health), relied on systematic reviews but only for narrowly defined health risks and not for benefits (the Endocrine Society), or used less scientifically rigorous “narrative reviews” (the American Academy of Pediatrics). One of the world’s leading experts on EBM has called U.S. medical groups’ treatment recommendations “untrustworthy.”

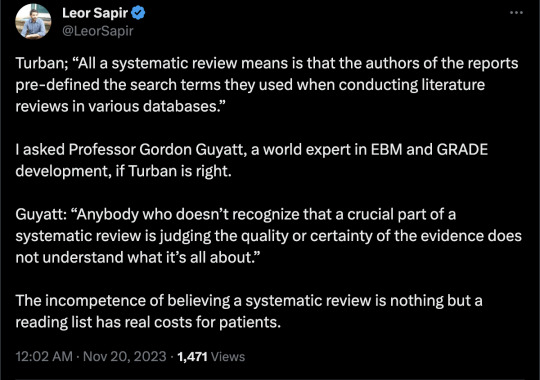

In the deposition, Ramer asked Turban to explain what systematic reviews are. “[A]ll a systematic review means,” Turban responded, “is that the authors of the reports pre-defined the search terms they used when conducting literature reviews in various databases.” The “primary advantage” of a systematic review, he emphasized, is to function as a sort of reading list for experts in a clinician field. “Generally, if you are in a specific field where you know most of the research papers, the thing that’s most interesting about systematic review is if it identifies a paper that you didn’t already know about.” Ramer showed Turban the EBM pyramid of evidence, which appears in the Cass Review (page 62) of the U.K.’s Gender Identity Development Service. He asked Turban why systematic reviews sit at the top of the pyramid. Turban responded: “Because you’re looking at all of the studies instead of looking at just one.”

Turban’s characterization represents a fundamental misunderstanding of what EBM is and why systematic reviews are the bedrock of trustworthy medical guidelines.

First, even if the only thing that makes a review systematic is that it “pre-defines the search terms,” Turban failed to explain the relevance of this. A major reason systematic reviews rank higher than narrative reviews in EBM’s information hierarchy is that systematic reviews follow a transparent, reproducible methodology. Anyone who applies the same methodology and search criteria to the same body of research should arrive at the same set of conclusions. Narrative reviews don’t use transparent, reproducible methodologies. Their conclusions are consequently more likely to be shaped by the personal biases of their authors, who may, for instance, cherry-pick studies.

To achieve transparency and reproducibility, systematic reviews define in advance the populations, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes of interest (PICO). They search for and filter the available literature with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Authors register their methodology and search criteria in advance in databases such as PROSPERO. These steps are meant to minimize the risk that authors will change their methodology midway through the process in response to inconvenient findings.

Turban acknowledged that pre-defining the search terms “makes it a little bit easier for another researcher to repeat their search.” However, he did not seem to grasp that the additional steps introduced by systematic reviews are designed to reduce bias and improve accuracy. Turban, one should note, endorses the American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2018 narrative review—a document that, with its severe flaws, perfectly illustrates why EBM prefers systematic to narrative reviews.

Second, Turban is incorrect that the “primary advantage” of the systematic review is to generate a comprehensive reading list for (in this case) gender clinicians. Systematic reviews also assess the quality of evidence from existing studies. In other words, they avoid taking the reported findings of individual studies at face value. This is especially important in gender medicine because so much of the research in this field comes from authors who are professionally, financially, and intellectually invested in the continuation of gender medicine—in other words, who have conflicts of interest. Financial conflicts of interest are typically reported, but professional and intellectual conflicts rarely so. Conflicted researchers frequently exaggerate positive findings, underreport negative findings, use causal language where the data don’t support it, and refrain altogether from studying harms. In short, assessing the quality of evidence is especially important in a field known for its lack of equipoise and scientific rigor.

In EBM, quality of evidence is a technical term that refers to the degree of certainty in the estimate of the effects of a given intervention. The higher the quality, the more confident we can be that a particular intervention is what causes an observed effect. It was only in response to Ramer’s prodding that Turban addressed “the risk of bias associated with primary studies”—namely, one of the key considerations for assessing quality of evidence.

During the deposition, Ramer read Turban excerpts from Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature, a highly regarded textbook of EBM published by the American Medical Association. Ramer asked Turban to explain what the Users’ Guides means when it says that narrative reviews, unlike systematic reviews, “do not include systematic assessments of the risk of bias associated with primary studies and do not provide quantitative best estimates or rate the confidence in these estimates.” Turban responded that systematic reviews do sometimes assess the quality of evidence, but that this is not a necessary condition for a review to be called systematic.

I asked Gordon Guyatt, professor of health research methods, evidence, and impact at McMaster University, what he thought of Turban’s answer. Guyatt is widely regarded as a founder of the field of EBM and is the primary author of Users’ Guides. “The primary advantage of a systematic review,” Guyatt assured me, “is not only not missing studies, but also assessing quality of the evidence. Anybody who doesn’t recognize that a crucial part of a systematic review is judging the quality or certainty of the evidence does not understand what it’s all about.”

Ramer asked Turban to explain the GRADE method (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluations), a standardized EBM framework for evaluating quality. “GRADE generally involves looking at the research literature,” Turban explained. “And then there’s some subjectivity to it, but they provide you with general guidelines about how you would—like, great level of confidence in the research itself. Then there’s a—and then each of those get GRADE scores. I think it’s something like low, very low, high, very high. I could be wrong about the exact names of the categories.” Turban is indeed wrong: the categories are high, moderate, low, and very low. It’s surprising that someone involved in the debate over gender-medicine research for several years, and who understands that questions of GRADE and of quality are central, doesn’t know this by heart.

Ramer asked Turban what method, if any, he uses to assess quality in gender-medicine research. Turban explained that he reads the studies individually and does his own assessment of bias. GRADE is “subjective,” and this subjectivity, Turban said, is one reason that the U.K. systematic reviews rated studies that he commonly cites as “very low” quality. Turban’s thinking seems to be that, because GRADE is “subjective,” it is no better than a gender clinician sitting down with individual studies and deciding whether they are reliable.

I asked Guyatt to comment on Turban’s understanding of systematic reviews and GRADE. “Assessment of quality of evidence,” he told me, “is fundamental to a systematic review. In fact, we have more than once published that it is fundamental to EBM, and is clearly crucial to deciding the treatment recommendation, which is going to differ based on quality of evidence.” Guyatt said that “GRADE’s assessment of quality of the evidence is crucial to anybody’s assessment of quality of evidence. It provides a structured framework. To say that the subjective assessment of a clinician using no formal system is equivalent to the assessment of an expert clinical epidemiologist using a standardized system endorsed by over 110 organizations worldwide shows no respect for, or understanding of, science.”

At one point, Ramer pressed Turban to explain his views on psychotherapy as an alternative to drugs and surgeries. Systematic reviews have rated the studies Turban relies on for his support of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones “very low” quality in part because these studies are confounded by psychotherapy. Because the kids who were given drugs and improved were also given psychotherapy and the studies lack a proper control group, it is not possible to know which of these interventions caused the improvement.

Turban seemed not to grasp the significance of this fact. If hormonal treatments can be said to cause improvement despite confounding psychotherapy, why can’t psychotherapy be said to cause improvement despite confounding drugs?

The exchange about confounding factors came up in the context of Ramer asking Turban about an article he wrote for Psychology Today. The article, aimed at a popular audience, purports to give an overview of the research that confirms the necessity of “gender-affirming care.” Last year, I published a detailed fact-check of the article, showing how Turban ignores confounding factors, among other problems. Four days later, Psychology Today made a series of corrections to Turban’s article. Some of these corrections were acknowledged in a note; others were done without any acknowledgement. In the deposition, Ramer asked Turban about my critique, to which Turban replied that he “left Psychology Today to do whatever edits they needed to do,” and that, when he later read the edits, he found them “generally reasonable.”

In sum, though Turban says that “there are no evidence-based psychotherapy protocols that effectively treat gender dysphoria itself,” the same studies he cites furnish just as much evidence for psychotherapy as they do for puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones—which is to say “very low” quality evidence.

Other remarkable moments occur in the Turban deposition. For instance, when asked whether he had read the Florida umbrella review (a systematic review of systematic reviews) conducted by EBM experts at McMaster University and published over a year ago, Turban said that he hadn’t because he “didn’t have time.” When I mentioned this confession to Guyatt, he seemed taken aback. How could a clinician who claims expertise in a contested area of medicine not be curious about a systematic review of systematic reviews? “If all systematic reviews come to the same conclusion,” Guyatt told me, “it clearly increases our confidence in that conclusion.” (My conversation with Guyatt dealt exclusively with Turban’s claims and how they stack up against EBM. I did not ask Guyatt about, and he did not opine on, the wisdom of state laws restricting access to “gender-affirming care.”)

I believe that Turban is being honest when he says he didn’t read the Florida umbrella review. He doesn’t seem interested in literature that might call his beliefs into question. He has staked his personal and professional reputation on a risky and invasive protocol before the appearance of any credible evidence of its superiority to less risky alternatives. Turban regularly maligns as bigoted and unscientific anyone who disagrees with him. Some gender clinicians in Europe now admit that the evidence is weak, the risks serious, and the protocol still experimental. Turban, however, would seemingly rather go down with the sinking ship than admit that he was too hasty in promoting “gender-affirming care.”

Put another way, Turban has intellectual, professional, and financial conflicts of interest that prejudice his judgment on how best to treat youth experiencing issues with their bodies or sex. European health authorities are aware of this problem; that’s why they chose to commission their evidence reviews from clinicians and researchers not directly involved in gender medicine. For instance, England’s National Health Service appointed physician Hilary Cass to chair the Policy Working Group that would lead the investigation of its Gender Identity Development Service and its systematic reviews. The NHS explained that there was “evident polarization among clinical professionals,” and Cass was “asked to chair the group as a senior clinician with no prior involvement or fixed views in this area.”

Unfortunately, in the U.S., personal investment in gender medicine is often seen as a benefit rather than a liability. James Cantor, a psychologist who testifies in lawsuits over state age restrictions, emphasizes the difference between the expertise of clinicians and that of scientists. The clinician’s expertise “regards applying general principles to the care of an individual patient and the unique features of that case.” The scientist’s expertise “is the reverse, accumulating information about many individual cases and identifying the generalizable principles that may be applied to all cases.” Cantor writes:

In legal matters, the most familiar situation pertains to whether a given clinician correctly employed relevant clinical standards. Often, it is other clinicians who practice in that field who will be best equipped to speak to that question. When it is the clinical standards that are themselves in question, however, it is the experts in the assessment of scientific studies who are the relevant experts.

The point is not that clinicians are never able to exercise scientific judgment. It’s that conflicts of interest for involved clinicians need to be acknowledged and taken seriously when “the clinical standards . . . are themselves in question.” Unfortunately, the American propensity for setting policy through the courts makes that task difficult. Judges intuitively believe that gender clinicians are the experts in gender medicine research. The result is a No True Scotsman argument wherein the more personally invested a clinician is (and the more conflict of interest he has as a result), the more credible he appears.

Last year, a federal judge in Alabama dismissed Cantor’s expert analysis of the research, citing, among other things, the fact that Cantor “had never treated a child or adolescent for gender dysphoria” and “had no personal experience monitoring patients receiving transitioning medications.” Turban’s deposition illustrates why this thinking is misguided. It is precisely gender clinicians who often seem to be least familiar, or at any rate least concerned, with subjecting their “expert” views to rigorous scientific scrutiny. It is precisely these clinicians who are most likely to be swimming in confirmation bias, least interested in the scientific method, and, conveniently, least concerned with evidence-based medicine.

==

Jack Turban is frequently a star "expert" in so-called "gender affirming care" enquiries. Aside from being a pathological liar, we can now also conclude he's dangerously unqualified.

#Leor Sapir#Jack Turban#Gordon Guyatt#evidence based medicine#gender affirming care#gender affirmation#gender affirming healthcare#dangerously unqualified#gender ideology#queer theory#conflict of interest#confirmation bias#medical scandal#medical malpractice#ideological corruption#gender activism#religion is a mental illness

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Smartest Path Begins with the Best Medical Scholarship Exams

A career in medical science needs the right foundation. In India, the dream of thousands of aspiring students starts with the completion of Class 12, which comprises Physics, Chemistry, and Biology. Nonetheless, medical and allied health science programs offered in private colleges often come with excessive college fees. This turns out to be an obstacle to many deserving students.

To fill this gap, well-organized and trustworthy scholarship platforms have appeared. The programs provide a golden opportunity to get financial assistance regarding professional programs such as B.Pharma, B.Sc. Nursing, B.Sc. Biotechnology, B.P.T., Paramedical, B.Sc. Agriculture (Hons), and B.M.L.T. The meritorious students are given these scholarships in a way that they are able to access quality education without fearing the impact of a lack of financial support.

Unlocking Opportunities in Medical Education

Students who complete Class 12 are focused on career-oriented programs with good employment opportunities and career development. Medical and life sciences are considered some of the most preferred courses. However, there are not many seats in the government institutions, and the fees in the private institutions are too high, which limits the options for the student.

That’s where the best medical scholarship exams come in. These competitive exams are also a means to enter good private institutions. The scheme awards partial or complete waivers of college fees to students through performance-based selection. This changes their career track and allows them to concentrate fully on academic and clinical excellence.

Academic Fields Covered

These scholarship programs are open to students pursuing undergraduate degrees in:

Bachelor of Pharmacy (B. Pharma)

B.Sc. in Nursing

B.Sc. in Biotechnology

Bachelor of Physiotherapy (B.P.T.)

B.Sc. in Agriculture (Hons)

B.M.L.T.

Various Paramedical Science disciplines

The incorporation of various streams allows students an option to select a stream of interest. The platform facilitates the practice of skills-based, industry-oriented education with funding assistance.

Fair and Transparent Selection Process

The criteria used in making the selection are purely based on merit. The students are required to apply online and take the entrance test at a national level. They are given a scholarship depending on their performance. This system appreciates academic ability and promotes fairness.

Key Advantages:

Scholarships covering full or partial college fees

Equal opportunity for all Class 12 PCB students

Transparent result declaration

No bias based on region, board, or background

Scholarship amount applied directly to college fees

Such a process creates trust among students and parents. It makes everything clear and eliminates any financial strain when making the admission.

Student-Centric Application Process

It has an easy and quick application process. Students should undergo an online registration using valid academic credentials. Once they make the submission, they are provided with all the updates they would need to know, such as syllabus information, exam dates, and study materials.

Guidance is offered throughout to keep the students informed and focused. There are also study materials and practice tests distributed to give confidence in the examination.

Why Choose These Exams?

As the competition increases and the seats in government colleges decrease, private institutions are increasingly becoming a viable option for many. Nevertheless, this alternative is unaffordable to many due to the lack of financial support. The best medical scholarship exams give these students the support they need to follow their dreams.

Not only do these exams reduce the burden on finances, but they also identify talent and reward it. Thousands of students in India have already benefited and are now studying their medical education with confidence.

This is an opportunity that students aspiring for a career in healthcare, biotechnology, or life sciences can not afford to miss. These exams provide all that a student requires, including fairness, recognition, affordability, and access to the best institutions.Start your educational career today and walk a step closer to your future. Secure your seat through the best medical scholarship exams.

0 notes

Text

Exploring the Ethics and Impact of Clinical Research

An In-Depth Look at the Future of Medical Innovation and Career Opportunities

Clinical research plays a pivotal role in shaping the future of healthcare. From developing life-saving drugs to evaluating innovative treatment approaches, this field has become the backbone of modern medicine. As clinical research continues to evolve, it brings with it a range of ethical considerations and career opportunities, particularly in India where the demand for trained professionals is steadily growing. In this article, we explore the ethical dimensions, educational pathways, and job prospects in clinical research while examining the broader impact it has on society.

The Foundation: Basics of Clinical Trials and Study Designs

Before diving into the ethics and career landscape, it's essential to understand what clinical trials are and how they're structured. Clinical trials are systematic investigations involving human participants to assess the efficacy and safety of medical interventions such as drugs, vaccines, or treatment protocols.

Key elements in clinical trial design include:

Phases of trials: Ranging from Phase I (safety) to Phase IV (post-marketing surveillance)

Control groups: Used to compare the test drug with standard treatments or placebos

Randomization: Minimizes bias by randomly assigning participants to treatment groups

Blinding: Ensures that participants and researchers do not know which group a participant belongs to

Understanding the basics of clinical trials and study designs is crucial for anyone entering the field, as these elements lay the groundwork for ethical and accurate scientific evaluation.

Ethics in Clinical Trials: A Moral Compass for Research

The importance of ethics in clinical trials cannot be overstated. Human life and dignity must remain at the core of all clinical investigations. Ethical guidelines ensure that participants' rights are protected, risks are minimized, and informed consent is obtained.

Major ethical principles include: