#even more hilarious when it's coming from diaspora in the West

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

that whole "East Asians are the white people of Asia" bullshit discourse a few months back reeks of sinophobia and I'm tired of pretending it's not

#ranting into the void#why did you think Dutch colonisers described us as the Jews of the East. For funsies issit#crazy how little the IJA was talked about#uwu I'm just a smol bean smol nation being bullied by big evil China which is big and therefore evil#ignore the pogroms#even more hilarious when it's coming from diaspora in the West#wypipo are not able to tell the difference lil bro#diaspora stfu challenge

1 note

·

View note

Text

Icon, Saints&Reading: Tue.,Nov.24, 2020

Commemorated on November 11_ Julian calendar

The Holy Great Martyr Menas (304)

The Holy GreatMartyr Menas, an Egyptian by birth, was a soldier and served in the city Kotuan under the centurion Firmilian during the reign of the emperors Diocletian and Maximian (284-305). When the co-emperors began the then fiercest persecution against Christians in history, the saint lost all desire to serve these persecutors and, having left the service, he withdrew to a mountain, where he asceticised in fasting and prayer. Once during the time of a pagan feastday he happened to arrive in the city, in which earlier he had served. At the climax of the festal games, which all the city had come out to see, rang out the accusing voice of the saint of God, preaching faith in Christ, the Saviour of the world.

At trial before the governor Pyrrhos the saint bravely confessed his faith and said, that he had come hither, in order to denounce all of impiety. Saint Menas spurned he suggestion to offer sacrifice to the pagan gods, and he was put to cruel tortures, after which he as beheaded. This occurred in the year 304. The body of the holy martyr as ordered to be burnt. Christians by night gathered up from the burnt-out fire the undestroyed remains of the martyr, which later were installed in a church in his name, built after the cessation of the persecution at the place of the suffering and death of the GreatMartyr Menas.

© 1996-2001 by translator Fr. S. Janos.

St. Martin the Merciful, bishop of Tours (397)

St patron of France

This holy and beloved Western Saint, the patron of France, was born in Pannonia (modern-day Hungary) in 316, to a pagan military family stationed there. Soon the family returned home to Italy, where Martin grew up. He began to go to church at the age of ten, and became a catechumen. Though he desired to become a monk, he first entered the army in obedience to his parents. One day, when he was stationed in Amiens in Gaul, he met a poor man shivering for lack of clothing. He had already given all his money as alms, so he drew his sword, cut his soldier's cloak in half, and gave half of it to the poor man. That night Christ appeared to him, clothed in the half-cloak he had given away, and said to His angels, "Martin, though still a catechumen, has clothed me in this garment." Martin was baptised soon afterward. Though he still desired to become a monk, he did not obtain his discharge from the army until many years later, in 356. He soon became a disciple of St Hilary of Poitiers (commemorated January 13), the "Athanasius of the West." After traveling in Pannonia and Italy (where he converted his mother to faith in Christ), he returned to Gaul, where the Arian heretics were gaining much ground. Not long afterward became Bishop of Tours, where he shone as a shepherd of the Church: bringing pagans to the faith, healing the sick, establishing monastic life throughout Gaul, and battling the Arian heresy so widespread throughout the West. Finding the episcopal residence too grand, he lived in a rude, isolated wooden hut, even while fulfilling all the duties of a Bishop of the Church. His severity against heresy was always accompanied by love and kindness toward all: he once traveled to plead with the Emperor Maximus to preserve the lives of some Priscillianist heretics whom the Emperor meant to execute. As the holy Bishop lay dying in 397, the devil appeared to tempt him one last time. The Saint said, "You will find nothing in me that belongs to you. Abraham's bosom is about to receive me." With these words he gave up his soul to God. He is the first confessor who was not a martyr to be named a Saint in the West. His biographer, Sulpitius Severus, wrote of him: "Martin never let an hour or a moment go by without giving himself to prayer or to reading and, even as he read or was otherwise occupied, he never ceased from prayer to God. He was never seen out of temper or disturbed, distressed or laughing. Always one and the same, his face invariably shining with heavenly joy, he seemed to have surpassed human nature. In his mouth was nothing but the Name of Christ and in his soul nothing but love, peace and mercy."

Icon: Iveron from Montreal

Today we commemorate one of the copies of the Iveron Mother of God Icon, called the Montreal Iveron Icon, a miraculously myrrh-streaming icon from which abundant grace poured forth to the Russian diaspora and many other Orthodox Christians. As God’s Providence and the Mother of God would have it, the man who was found worthy to receive this icon from Mount Athos and become its custodian was in fact a convert to Orthodoxy from Catholicsim—José Muñoz from Chile, now also known as “Brother José.” Archpriest Victor Potapov spoke with the icon’s custodian on one of his visits to Washington.

The Iveron Icon, which at present is preserved in a monastery on Mount Athos, was according to tradition painted by the Apostle and Evangelist Luke. In November 1982, a copy of the Iveron Icon of the Mother God began to stream myrrh in Canada. In 1983, the Icon was in Washington for the first time, and I then asked its guardian, the Spaniard José Muñoz, how he had received the Holy Object, and when it had begun to stream myrrh. Here are his own words, which were recorded during our conversation with him:

“Once during our pilgrimage on Athos, after several hours of walking, we got lost. It began to get dark. We needed quickly to find shelter for the night. Going along a path, we stumbled upon a small, poor skete. There the fourteen Greek monks of the skete were engaged in iconography. They received us very cordially. Having rested a little, we began to examine the icons of their work. One of my fellow travellers, who spoke Greek, got into a conversation with the monks and told them who we were and where we were from. I, though, taking advantage of the moment, began more attentively to examine everything round about. Suddenly my gaze stopped at an icon of marvelous artistry with dimensions of approximately fifteen by twenty inches. I asked a monk if he could not sell it to me. He refused, having explained that this image was the first to be painted in that skete and therefore could not be sold. I could not tear my eyes from that wondrous icon. We stayed the whole night in the skete and in the morning stood through the Liturgy. During the singing of “It is truly meet”, I begged the Queen of Heaven on my knees to let the Holy Image go with me... Bidding farewell in the morning, all the monks accompanied us, but the hegoumen [abbot.—O.C.] was not among them. And then at the last minute before our departure from the monastery we saw him: he quickly descended the staircase with the wrapped-up icon in his hands. He came up to me and said, “Take it. I am gifting it to you. It must be with you.” I offered to pay for the icon, knowing that the monks were needy; but the hegoumen said severely, “One must not take money for such a holy object!” I crossed myself, kissed the image and made a vow to myself that that image would never become the source of my enrichment..more to read

Luke 12:42-48

42And the Lord said, "Who then is that faithful and wise steward, whom his master will make ruler over his household, to give them their portion of food in due season?43 Blessed is that servant whom his master will find so doing when he comes.44 Truly, I say to you that he will make him ruler over all that he has.45 But if that servant says in his heart, 'My master is delaying his coming,' and begins to beat the male and female servants, and to eat and drink and be drunk,46t he master of that servant will come on a day when he is not looking for him, and at an hour when he is not aware, and will cut him in two and appoint him his portion with the unbelievers.47 And that servant who knew his master's will, and did not prepare himself or do according to his will, shall be beaten with many stripes.48 But he who did not know, yet committed things deserving of stripes, shall be beaten with few. For everyone to whom much is given, from him much will be required; and to whom much has been committed, of him they will ask the more.

Thessalonians 1:10-2:2

10when He comes, in that Day, to be glorified in His saints and to be admired among all those who believe, because our testimony among you was believed.11 Therefore we also pray always for you that our God would count you worthy of this calling, and fulfill all the good pleasure of His goodness and the work of faith with power,12 that the name of our Lord Jesus Christ may be glorified in you, and you in Him, according to the grace of our God and the Lord Jesus Christ.

1Now, brethren, concerning the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ and our gathering together to Him, we ask you, not to be soon shaken in mind or troubled, either by spirit or by word or by letter, as if from us, as though the day of Christ had come.

#orthodoxy#orthodoxchristian#ancientchristianity#originofchristianity#sacred texts#gospel#holyscriptures#wisdom#spirituallity

1 note

·

View note

Text

South-Asian Diaspora experience

So here’s the thing: a lot of people in the South Asian diaspora joke about being ‘coconuts’ (as in ‘brown on the outside and white on the inside’) - and usually that’s cool, it’s just bants. But lately that just hasn’t been sitting right with me. I guess I can only speak from personal experience, but being born and brought up in Britain as a child of the Indian diaspora instilled in me a constant need to blend these two dichtonomous identities within myself. I feel like when people think about diaspora, people are quick to assume that it’s just the mixing of two cultures in one person. Easy. But honestly, that’s never what it felt like. Most of the time these two cultures felt imiscible, and it felt as though the only way I could grapple with them was if I alternated between the two.

To me, it has always felt like I was half of those two half identities; my claim to being an Indian ‘in touch with her roots’ could always be derailed by that fact that I didn’t grow up there - most of my exposure to that culture was second handed in that it was inherited from my parents or that it was what I observed from other Indian migrant communities around me. The feeling of detachment from Asian culture was slightly subdued for me because I grew up in a pocket of London with a large and dominant South Asian community, and so the feeling of being a minority was almost unrealised until I started going to a school in another town (whilst still living in this one). Almost. As for being British; at home I spoke in my native language, we almost exclusively ate Indian food (the first time I ever had British roast was when I moved to the new school in year 9), and in many ways the way my parents ran the household was the way their parents and grandparents had run theirs in India - that culture was embedded in their upbringing in the way the embedded it into mine. Like I said, because the place I lived in was very South-Asian (with many of the foods, clothes and other products being sold in India being imported there too and therefore being accessible to us), my primary school wasn’t very racially diverse. I was surrounded by people that were also the children of immigrants, and so we had very similar cultural upbringings and a strong sense of ethnic identity that we shared with each other. When I moved school, there were significantly less South-Asian students (although it was still relatively racially diverse), and so I had more exposure to the typical ‘British suburbian’ experience. The were fewer kids that had parents that were immigrants (I’m a first generation British-Indian), and more ‘just British’ kids.

So when I got to this new school, it felt like a completely new world for me. It was just a very different cultural atmosphere, a more ‘British’ one. As a result, subconsciously I began to downplay my Indian one to fit in more, because that’s what the other British-Asian kids seem to do too. I began to acclimatise to alternating between a completely British persona when I was at school, and back to the more Indian version of myself when I was at home with my family. Looking back on it, we had a lot of cliques in that school, and a lot of them were composed of people from similar cultures - maybe because we related to the feeling of separating these two identies because it was so hard to find a way to express them at the same time? Idk? Don’t get me wrong, I was very lucky that all the schools I attended promoted a lot of cultural awareness and were very tolerant and willing to learn about them as well. Growing up in London was wonderful for just that reason.

My point is, I always felt conflicted about my identity. I knew that I was British, but that’s never what it felt like when I was at home, with my family where I felt most the most comfortable, where I wasn’t consciously trying to control the way I was perceived by my friends and felt my most natural. I didn’t feel very British when I was rarely ever represented on tv (I know things have gotten better but frankly there’s a long way to go and representation of racial minorities in the West is still a huge issue), but I felt embarrassed to be an Indian when the only time we were represented was within the context of stereotypical narratives; the stingy convienience store owner, the nosy and gossipy neighbour judging of the more liberal and western ways, the boring doctor who’s entire personality revolved around the fact that they were a doctor, the awkward and traditional schoolgirl hopelessly in love with the white boy that would never love her back because she didn’t exemplify western beauty ideals - wasn’t that hilarious? Maybe that’s why I subconsciously tried to disassociate myself from my ‘Indian-ness’ when I was around anyone that wasn’t South-Asian. It kind of felt like my Indian identity was lesser, alien even. And another part of me was like, ‘Look! I’m just as British as you are.’

It was so tiring trying to validate these identities to myself when I was younger. So now, in the age of social media, it’s so liberating so see more South-Asian figures being represented. I still don’t think it’s nearly enough, but it’s still amazing to see accounts on instagram sometimes dedicated to documenting their experience of being of a non-western identity in the West. To see people more comfortable wearing bindis, saris or cultural clothing to proms, wearing bangles, ethnic jewellery. To see people discussing it more. To see people refusing to conform to one identity by means of suppressing another. By no means am I an expert on what Indian culture is, like I said before, my knowledge and experience of it is very fragmented; it has been within a British context. That seemed like reason enough to shy away from embracing my heritage - I was an imposter in that world. My expression of it would come across as selective, as though I was fetishising this culture and appropriating it in the way it had been done countless times. How can I completely express something I am not completely familiar with?

And that’s not very fair.

My brother can’t speak our native language but I can. That doesn’t make him any less Indian. Some of my friends are of mixed race with one of the parents being Indian. That doesn’t make them any less Indian. The fact that I am Indian doesn’t make me any less British.

Our collective experience of culture is so varied anyway, how can you attempt to quantify our experience of our identity? How can you compare something that can’t be quantified? I guess for some people culture doesn’t matter a lot, and that’s okay, but for me it clearly does. And I’m sick of being labelled a coconut just because I wasn’t born in India. I’m sick of feeling the need to ‘prove’ my Indianess, being told that ‘I’m not *that* Indian’. I’m sick of trying to validate it in the eyes of others. Vice versa with my British identity to. I am so proud to be a British Indian. I know what that means to me, to you that may mean something else entirely, and that is still valid.

Our experiences of culture are just as diverse as we are; there are a myriad of cultures across both Britain and India, and the only thing uniting them are the places they originate from. There is so much to learn from culture, and so much to translate it to - art, music, or just your life. Whatever you resonate with, rings true.

#chelcoast#asian#south asian#diaspora#british#rant#london#culture#bollywood#ethnicity#nationality#i’m sorry but this was just bugging me for ages#embrace who you are!!!!#if you don’t resonate with the diaspora experience then that’s okay too

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

To My Sisters: Photographer Liv Latricia Habel On Her Resilient Self-Portrait Series ‘Diasporan Daughters’

Danish American photographer Liv Latricia Habel is the creator of the reflective visual diary ‘Diasporan Daughters’. It’s a moving series of self-portraits that explore her take on what it means to be a mixed Black woman, and what it is to be seen as a mixed Black woman in Denmark. Raised in Germany by her mum and currently living in Copenhagen, Liv’s series comments on her personal experiences of being one of the few brown faces in her community growing up. She also dives into her connections with America and her different relationships with religion. This interesting combination of personal lived experiences informs not only the style of her photographs but also the meanings behind them. Liv explores societal expectations, her personal views, representation and resilience through her images. I got the pleasure to sit down with her (over Zoom) and talk all things self-love, fighting spirit, sisterhood, alter egos, and the craziness that is code-switching.

RC: Hey Liv. how are you doing?

LH: I’m doing good, I’ve just moved to a new apartment.

RC: That sounds fun; you get to decorate a new space. Do you do all that feng shui stuff?

LH: I don’t really know anything about that [laughs]

RC: Neither do I! You just put what feels right wherever.

LH: Right, exactly. How are you?

RC: I’m doing good too, tired but good! I’m happy I got to hop on this call with you though, it’s a cool change of pace.

RC: So do you study film or photography or something else creative?

LH: Yeah, I study at Copenhagen Film and Photography School. It's a one year compact course and it’s ending this December. I also studied Visual Communications a few years ago.

RC: Ooh, that’s a good combo, they work together well.

LH: Right now I’m using my skills, but it's not really what I want to work with.

RC: What do you want to work with?

LH: Photography!

RC: [laughs] I like that.

LH: I like working with photography, but it’s not my main income.

RC: Sometimes you need a plan B to help your plan A.

LH: Yeah.

RC: So is the book Diasporan Daughters a project for school or a personal project?

LH: This is a personal project, my evaluation project for school is about young female and Black artists, which I’ve been photographing.

RC: That’s super relevant nowadays, it’s also nice to do a little showcasing because all this talent is there, but not a lot of people know about it.

LH: Yeah, exactly.

RC: I was wondering what made you come up with this project?

LH: [laughs] Okay the interview is starting!

I came up with it because of my own story. My mum is Danish and my dad’s Black American. I grew up in Germany with my mum who’s white and with my white family. My school and community were totally white, so I spent my childhood and adolescent life learning to look like everyone else. I couldn’t mirror myself in anyone around me, neither in my family nor my friends till I was 19 and moved to Copenhagen and found my own community and friends.

RC: Oh wow!

LH: I was 20 when I had my first Black friend and started having contact with my family in the US, so it wasn’t that many years ago. I think of it as being a chameleon sometimes since I have so many identities that frame who I am today. I guess everyone has different identities and we can code-switch when we talk and adapt. Which is just superhuman! But for me, as a mixed Black woman, it's even crazier because of the way I grew up: I have so many identities. There are the ones that I’ve been living with, but also the identities society has given to me – which are a reflection of structural racism too. So you know, when I’m walking down the street in a specific neighborhood in Copenhagen, where there’s a lot of sex workers, and I’ve dressed up, and look good: men directly ask me how much I am.

RC: Really?!

LH: Or if it’s another situation where I might be confused for someone else, only because of my skin color.

RC: I definitely felt that through the book because there were a lot of photographs of you in different settings.

LH: Some of the portraits, I can definitely see myself in, I mean one of them is my alter ego.

RC: Ah which one is that one?!

LH: The one where I’m sitting with the pink bandana.

RC: Boss lady?!

LH: Yeah, its me when I’m the best me [laughs]

RC: That’s really cool, cause it's not only different identities you’re exploring but different versions of yourself as well.

LH: Exactly. It's different versions of myself, that’s what I mean by identities actually. Some of the images aren’t me, but what society thinks of me. Like my expereinces of being mistaken as a sex worker or cleaning lady. They’re stigmatized stereotypes of a Black woman in white society.

“There are the ones that I’ve been living with, but also the identities society has given to me..”

RC: I like that! It’s an ongoing story, you can add more as you go.

RC: Why did you decide to title your series Diasporan Daughters?

LH: Hmm, being part of the Black diaspora means everything in terms of my looks to me and society. It is also such a big part of who I am, and the title refers to all the women and girls who are part of the Black diaspora. That obviously includes the African diaspora, but for me, being part of the Black diaspora means more since my African roots are pretty far away [laughs].

RC: It felt like a love letter where you said ‘I’m writing this for me, but also for you’. That’s a sweet idea I think.

LH: It is! In the beginning of the book it says “For my Sisters”.

LH: Each one of us is unique with our individual experiences, but we have a lot in common. Especially when you’re living in the diaspora. I guess it's a different experience to be a Ghanian woman living in Accra for example, where you were born and grew up surrounded by a lot of other Black women. I imagine that experience differs to mine: living as a Black woman in a white dominated society. So the book is mainly for my sisters in the diaspora.

RC: I also saw one of your images was of you standing beside the Queen Mary statue in Copenhagen. She’s a very powerful woman, why did you feel it was important to take that photo?

LH: I wanted to add this archetype of a fighting personality. And for me, this picture has connections to the Black Panther movement. At the same time, this image also connects to the Black Lives Matter movement that has been expanding worldwide in 2020 after Breonna Taylor and George Floyd's murder. For me, the only public symbol fighting the Black struggle that exists here in Denmark, is the Queen Mary statue. She means so much because she led the labour riots of former slaves and plantation workers in the then Danish colonised West Indies. So, it’s all connected for me: fighting for your liberty as a Black person since slavery till today.

RC: She’s also powerful because of the scale. The statue is a lot bigger than many others in Copenhagen, so when you get there, you have to look up. I was almost thinking, is this really here? It is one of the only public images of a Black woman – there should be more!

LH: Definitely. For me, this image is not the strongest stylistically in the book, but its content definitely says a lot more than a lot of the other pictures because it has so much more depth.

RC: You’ve spoken about people of color’s experiences, not only in Denmark, but around the world too. There was one photo where you were wearing a red scarf, I was wondering if that had anything to do with the Burqa Ban in Denmark, or if there was any connection with that?

LH: That’s a good question. No, it doesn’t actually. My dad’s family is Muslim, so I got the whole outfit from my aunt. I grew up pretty nonreligious; I only went to church on Christmas, and I had a Confirmation because of the presents and because everyone else in my class had one – so that’s been my relationship with religion. Being in Philly and celebrating Eid made me experience a different religion that’s part of me. I’ll probably never get into Islam because I disagree with parts that I think can be problematic, as a lot of other religions around the world can be. As a Black woman wearing a sign of God means so much, because if you’re walking around in the streets as a brown or Black woman wearing a hijab, you’re looked at way more than if you’re not wearing a scarf. I’ve only worn a hijab once for Eid with my family, but when I’m wearing a scarf just for a bad hair day, I can get looked at differently.

RC: Yeah, I guess you can pick it up.

LH: Yes exactly, the photo comments on that, and also for the little part of me that’s Muslim too.

RC: That’s really nice, that you recognize these different dimensions and layers to yourself. It’s not just ‘I didn’t grow up with this, so I’m going to ignore it’, I think that’s quite a powerful photo in your collection.

LH: Thank you, there's also just so much stigma connected to being a Muslim woman and wearing a headscarf, niqab or burqa I find, especially here in Denmark, politically, it’s often connected to Islamophobia.

RC: The other thing I wanted to ask about was the types of text you include in your book. You have poetry from Maya Angelou and lyrics from Cardi B’s and Megan Thee Stallion’s song WAP.

LH: I’ve known the poem from Maya Angelou for some years, and I think it’s a very beautiful poem. I actually have to look up when it was written – it was published around 25 years ago. But it expresses how important it is to have self-worth, self-esteem, show who you are, and to be proud of who you are and every bit of yourself. That’s why I chose it, and WAP, I just think it’s a hilarious song, and I think since Lil’ Kim, Missy Elliott and other female pioneers in Hip Hop have been rapping about femininity, being in control of their own sexuality, and about sex in general. WAP is just the biggest 2020 example of how women should express that part of themselves. It’s a very extroverted song, whereas the Phenomenal Women poem is very ‘You have to stand up for yourself, but you don’t have to shout it out’. WAP, on the other hand, is ‘You shout it out!’- [laughs].

RC: I think that’s pretty interesting because they both talk about the strength and resilience of a woman just in very different ways.

LH: I also added an extract from the report of the African American Policy Forum. It is a list of all the African American women who have been killed by police brutality. And that’s a list of 48 women who have been murdered or died in detention because of the color of their skin. This is only the official list you know –

RC: Somethings aren’t documented…

LH: Yeah, exactly! Where have you actually seen the book?

RC: I saw a version of it online! So I did some stalking [laughs].

LH: Ahh okay, well done! I’ve actually changed a bit of the layout of those names from the online version. I’ve put the names of the women who have died in the same year in the same paragraph. Since 2011, there's been so many murders. The rate has been increasing, but I find that we don’t talk about it as much as the Black men being murdered in the US.

RC: Is that why you felt it was important to showcase it in your book?

LH: Yes, it's definitely a different rate when we talk about the US. In my experience, we talk a lot about men, and how they are targeted more in terms of police brutality. But after George Floyd, there weren’t that many people talking about Breonna Taylor in my circles, which happened three months before. Even my mum’s friend was like ‘Who’s Breonna Taylor?' and I was like ‘Yoo, educate yourself!’ So that’s why I added them. Also, I’m a woman myself!

RC: You gotta work in your own interest –

LH: Exactly! I can't relate to the men, but I can represent us.

RC: It’s a solidarity moment. What do you hope people take away from your book?

LH: So I hope that everyone who sees and reads it can get something positive, meaningful, and forceful out of it, which they can translate into something that drives them. Secondly, when I’m a bigger photographer and if..

no, when the book gets -

RC: Yes! WHEN! You have to manifest!

LH: [laughs] Yes, when the book is out there on bookshelves, I hope I can also be a representative Black face for young mixed Black kids and girls. Now I’m also saying mixed because I’m that myself, but it'd just be good to get more representation out there. My biggest dream as a child was just to see someone who looks like me in this Western world.

RC: Do you think that would have helped you when you were younger in Germany?

LH: For sure! That said, I’m also extremely privileged because I’m light skinned. Knowing that, It’s very much like standing in between two worlds especially when I’ve only grown up with one side. I’m always thinking I’m not white enough or not Black enough and trying to find an in-between. So with the book, I wanted to acknowledge that you can be as many different parts of yourself as you want to be

RC: You don’t have to choose.

LH: Exactly, you don’t need to choose!

0 notes

Text

Book Review: Satis Shroff Book Review-Kathmandu Blues: The Inheritance of Loss and Intercultural Incompetence by Satis Shroff 'My characters are purely fictional,' says Kiran Desai. In her book (The Inheritance of Loss) she has tried to do exactly that, namely to capture her own knowledge about what it means to travel between East and West, and to examine the lives of migrants who are forced to hypocrisy, angst of being nabbed, and have biographies that have gaps, and whose lives are constructed with lies, where trust and faith in someone is impossible, as in the case of Sai and Gyan. Migration is a sword with sharp blades on both sides. The feeling of loss when one leaves one's matribhumi is just as intensive and dreadful as having to leave a foreign home, due to deportation, when one doesn't have the green-card or Aufenthaltserlaubnis. Everyone copes with such situations differently. Some don't have coping solutions and it becomes a traumatic experience for the rest of one's life. Some pull up their socks, keep a stiff upper-lip and begin elsewhere. The problem of illegal migration hasn't been solved in the USA, Britain, France, Germany and other European countries. It is an open secret that the illegal migrants are used as cheap laborers according to the hire-and-fire principle, for these people belong to the underclass. In the USA it's chic to have Hispanics as baby-sitters, just as Eastern Bloc women are used by German families to do the household chores. Nepalis work under miserable conditions in India as darwans, chowkidars, cheap security personnel and the Indians have the same arrogance as the British colonialists. The judge, Lola and Noni are stereotypes, but such people do exist. It's not all fantasy. I'm sure the Gurkhas looking after photo-model Claudia Schiffer and singer Seal's house and guarding the palace of the Sultan of Brunei are well paid and contented, in comparison to other people in Nepal and the Indian sub-continent. What does a person feel and think when he or she goes from a rich western country to the East? And what happens when a poor Indian comes to the USA (land of plenty) or Germany (Schlaraffenland)? Is there always a feeling of loss? I've been living thirty years in Germany and I have met and seen and worked with migrants with biographies from Irak, Iran, Turkey, Nepal, India, Pakistan, Vietnam, Kosovo, Albania, Croatia and East Bloc countries. The worst part of it is that the Germans ignored the fact that it had already become, what they call 'ein Einwanderungsland.' They thought they'd invited only guest workers after World War II, with limited stay-permits, not realizing that they'd encouraged human beings with families and emotional ties, hopes and desires of a better future in the new Heimat with for their children and their grand-children. Kiran Desai flashes back and forth, between Kalimpong and New York, and she uses typical clich's and Indian stereotypes that have also been promoted by Bollywood. She's just as cynical and hilarious with her descriptions of fellow Indians in the diaspora, as she is when she describes the Gorkhalis in Darjeeling. Her portrait of the Nepalis in Darjeeling is rather biased, but what can one expect from a thirty-six year old Indian woman who has been pampered in India, England and the USA? Her knowledge of Kalimpong and Darjeeling sounds theoretical and her characters don't speak Nepali. She lets them speak Hindi, because she herself didn't bother to learn Nepali during her stay in Kalimpong. The depiction of a Gorkhali world might be true, as far as poverty is concerned, but she has no idea of the rich Nepali literature (Indra Bahadur Rai, Shiva Kumar Rai, Banira Giri to name a few), and folks music in the diaspora. Gyan's role was overdone, especially when Sai demands that he should feel ashamed of his and his family's poverty and so-called low descent. What is Gyan? Is he a Chettri, Bahun, Rai Tamang, or even a Newar? Describing a country, landscape is one thing, but creeping into the skins of the characters is another. The Gorkha characters remain shallow, like caricatures in Bollywood films, and she overdoes it with the dialogue between Sai and Gyan. For someone like me, who also went to school in Darjeeling, Kiran Desai's book was a pleasant journey into the past, where I still have fond memories of the Darjeeling Nepalis, their struggle for recognition and dignity among the peoples of the vast Indian subcontinent. I'm glad that peace prevails in the Darjeeling district, although I wish Subash Ghising had negotiated more funds from the central Indian government, and a university in Darjeeling. Gangtok (Sikkim) also does not have a university. The recognition of Nepali was a positive factor, but a university each for Darjeeling, Kalimpong and Kurseong would have given more Nepalis (pardon, Gorkhalis) the opportunity for higher education and better jobs, if not in the country, then abroad. To eat dal-bhat-tarkari at home and acquire MAs and PhDs within one's familiar confines would have immensely helped the Gorkhali men and women, even more than the recognition of Nepali. We can regard it as a small step towards progress. The description of Gyan's visit to Kathmandu was extremely superficial. Kathmandu is a world, a cosmos in itself, with its exquisite temples and pagodas and stupas and the culturally rich Newaris families from Lalitpur, Bhadgaon and Kathmandu. Kiran is, and remains, a supercilious brown-memsahib, like the made-over English characters of Varindra Tarzie Vittachi's fiercely satirical book 'The Brown Sahibs' in her attitude towards Gorkhalis and the downtrodden of her own country. I can imagine that the Nepali author D.B. Gurung is piqued about Desai's portrayal of the Nepalis in Kalimpong as 'crook, dupe, cheat and lesser humans' and his own emotional rejoinder regarding the Bengalis as 'the hungry jackals from the plains of Calcutta.' Since D.B. Gurung is known for his poetic vein, perhaps he can treat the long standing problems between Indians and Nepalis, or as Desai puts it, Bengis and Neps, in his lyrical verses. But please, less of the vitriol and more of tolerance, because even a poet and novelist can make or break human relations. I, for my part, am for living together, despite our differences, for variety is the spice of life in these days of globalization. Vive la difference. The story is served like a MacDonald's Big Mac for the modern reader, who has not much time, and there are multi-media distractions craving for his or her attention. As small morsels of information, like in a sit-com. I found the story-pace well timed and interesting, and she has a broad palette of problems that migrants face when they leave their homes, and when they return home. You can feel with Bijhu when he embraces his Papa in the end. A foreign-returned son, stripped of all his belongings. It was a terrific metaphor. I'm glad that there are women like Kiran Desai and Monica Ali (Brick Lane) who've traveled and experienced what it is like to be in the diaspora and try to capture the emotional and historical patterns in their lives as migrants. When you read the last page of the Desai's book you feel a bit dissatisfied because you wish that the unequal love affair between Gyan and Sai will go on and take a positive turn. There are so many Nepali-Indian couples who live happy conjugal lives with their families. I know at least three cases of Nepali women who're married to Bengalis. The Nepali women speak perfect Bengali, but their husbands don't speak Nepali, even though they live in Gorkhaland. They are proud that they can speak English instead. Nepali (Gorkhali or Khas Kura) is such a colorful and melodious language and we ought to listen to Sir Ralph Turner's when he says: 'Do not let your lovely language become the pale reflexion of a sanskritised Hindi.' Dinesh Kafle calls Desai 'schizophrenic.' Well, when you talk with an Indian he always praises the achievements of India in terms of the second Silicon Valley (Bangalore), the Agni and Prithvi missiles, the increasing nuclear arsenal, the expanding armed forces etcetera. But, Gott sei dank, there are Indians, who like Gandhi, are humble, religious, practice humility, are poor, deprived, castless, untouchables and, nevertheless, human and full of empathy, clean in their souls and hearts, and regard this world as merely a maya, an illusion, an earthly spectacle to be seen and felt---without being attached. D. B. Gurung is wrong when he assumes that Desai seems 'unable to acclimatize herself to either the western milieu or her own home.' But where is her home? She's a rootless, creative jet-set gypsy, who calls India, England and USA her home. The gypsies (Sintis and Romas) were originally from India (Rajasthan), weren't they? Even V.S.Naipaul (Half a Life, The Mimic Men), J. M. Croatzee (Youth), Isabel Allende (The Stories of Eva Luna) and Prafulla Mohanti (Through Brown Eyes) haven't gone so far in their description of a race or nation the way Desai has in her book. What is missing in her writing is the intercultural competence. Instead of taking the trouble to learn Nepali and acquiring background knowledge about the tradition, religion, norms and values, culture and living style of the Gorkhalis in Darjeeling and the Nepalese in Nepal, and comparing it with her own Indian culture, and trying to seek what is common between the two cultures and moving towards peace, tolerance, reconciliation---she just remains adamant , like her protagonist Sai. She does not make an ethnic reflection, but goes on and on, with a jaundiced view, till the bitter end. The dialogue between Neps and Bengis, between Neps and other Indians (Beharis and Marwaris and others from the plains) or between the British and Indians cannot be described as successful intercultural dialogues. The dialogues are carried out the way it should not, because there's always a fear that one is different in terms of social and ethnic status, even between her two main protagonists: Sai and Gyan. There is no attempt to reveal the facts behind an alien in a new cultural environment, no accepting of the problems of identity and no engagement for equality and against discrimination. If you're looking for frustrations-tolerance, empathy and solidarity with the Gorkhalis in the book, it's just not there. The characters necessary for intercultural interaction are joy in interaction with foreign cultures (not arrogance and egoism), consciousness of one's own culture, stress tolerance, tolerance of ambiguity, and bucketfuls of empathy. Had she shown empathy towards the Nepalis from Darjeeling and Kalimpong and made a happy-end love story between Gyan and Sai, the Nepalese would have greeted her with khadas and marigold malas. The way it is, she has only stirred a hornet's nest. Kiran just doesn't have empathy for Neps, despite the Booker Prize. Great women are judged by the way they treat the underprivileged and downtrodden. Perhaps it's time for meditation and self-searching in Rishikesh, like the Beatles. Pic of Kanchenzonga, courtesy: pixaby

0 notes

Text

In which Jane turns 60 in the desert

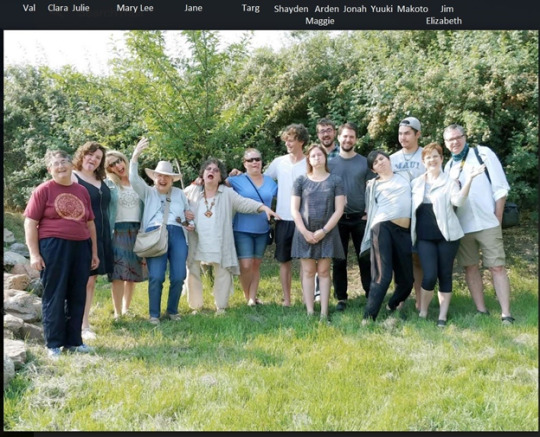

Thursday, July 25th, 2019 was the first day that we were all together, everyone present. On Wednesday, my cousin Targ (a nickname created from “Margaret”) and her mother, my aunt, my father’s only sibling, Mary Lee Lincoln McIntyre, had arrived in a rental car from Eugene airport and checked into a cabin at Summer Lake Hot Springs. My sister, Elizabeth Lincoln, drove my kids, Jonah and Clara, and two of her kids, Yuuki and Makoto, and her husband Jim, up from Reno, arriving just after noon. My cousin, Julie McIntyre, drove with her son, Shayden, all the way from Tucson, AZ. Valerie’s youngest, Arden, and his partner Maggie drove in from the Willamette Valley, and Valerie’s sister Karen arrived on Thursday from Chiloquin. Karen left on Friday, having to prepare a sermon for Sunday, so by Saturday morning, this was the assembled crew:

We had a more serious portrait shot but I tend to prefer the ‘act goofy’ photos. I look like a zombie, well fed after the apocalypse, Valerie is simply laughing. Mary Lee, age 86, is clearly game for anything. Yuuki is doing a pose. Maggie is blowing bubbles. Everyone was a good sport.

Months ago, realizing I was headed to the end of my 60th year on earth, I decided to invite the descendants of Ruth and Henry Lincoln to the Oregon Outback, Great Basin, High Desert land of Paisley to celebrate the fact of my existence. Not all could come, but a surprising number did. And the two relations of Valerie who were easily able to join us, got to meet more of my peeps.

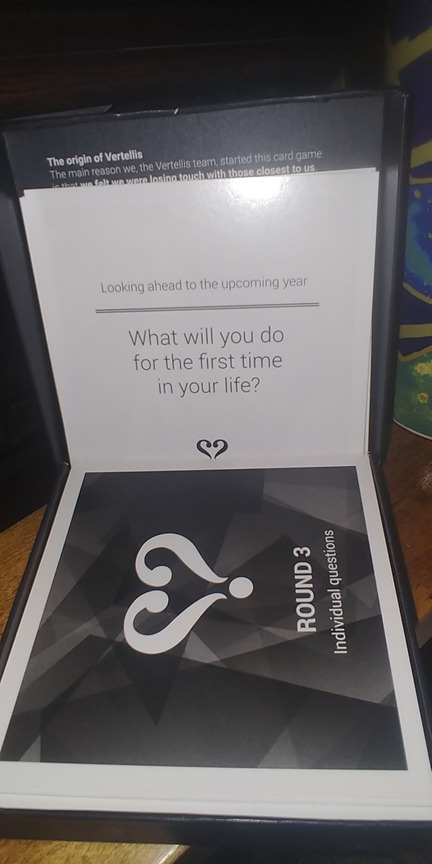

That Thursday, we enjoyed a Mexican themed dinner, accommodating the vegan and the beef-eating, the gluten free and the ‘organic-only.’ Since July 25th was the day I decided would be my designated birthday with everyone as my captive audience, we played “Vertellis.” It’s a Dutch card game that’s pretty simple: four rounds are organized into individual and group questions. I picked two categories of individual questions: Looking back on the year, what was good, crazy, interesting… and, looking forward to next year, what do you plan, hope for, find challenging? Everyone picks a card with a question, and you answer as honestly as you wish when it’s your turn.

I highly recommend https://vertellis.com/ for gatherings of people you don’t regularly see, especially around holidays. The answers can be hilarious, revelatory, and touching. When Valerie drew a card about picking something from the past year that she regretted, she told us: “I should have bought that primer bulb for the weed whacker way sooner!” Ever the practical gal, that Valerie! Clara hopes that the immigration hearing goes well for her husband, Jose. The answers spanned quite a range, and helped us to know each other a little bit better.

Why do we gather relatives only for funerals and weddings? Or for old people’s 90th birthdays? Why not age 60?

I did feel selfish about the whole thing, off and on. My family had to spend money on the flights, the rental cars, and then the cabins at Summer Lake Hot Springs. My friend and coworker, JD, and his husband Joey lent me their RV camper, so 4 of the young’uns could sleep in that for nothing’. There were 4 Lincoln/McIntyre/Matteuccis and 4 Lincoln/Frey/Saitohs in each cabin. There was a lovely symmetry to the housing. The inside of the cabins has a southwest, rustic feel:

They are not air conditioned, and it was quite hot during the day, although as we say out west, at least ‘it’s a dry heat.’ Here in the desert, it is also very dusty. Thank goodness the temperatures cool off at night to around 50 degrees F, and there’s almost always a breeze.

There are the fabulous hot springs pools, too: here is the pool house at dusk, run through a filter:

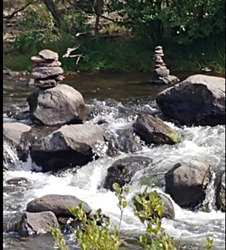

We managed to escape the heat by going to the swimming hole in the Chewaucan River, which I’d never been to. The water is cool but not freezing, and clear, so that I could sit in a shallow spot and pick out flat rocks for Clara to skip. Even my aunt went, situated in a camp chair, safe from the water, and an elderly chihuahua named Uddha came, too. He stayed well away from the watery fracas.

Valerie and Uddha

Mary Lee and Uddha

Someone stacked rocks in a lovely sculptural way:

We spent Friday schlepping to Picture Rock Pass to look at the petroglyphs, and then to Crack in the Ground, where I’d been wanting to go. That place is magical. Aunt Mary Lee sat comfortably in the shade on the picnic bench while the rest of us went one way or another, deep into the crevasses. My cousin’s son Shayden is a confident free climber and scaled all the way to the surface. We breathed in the moist, cool air and reveled in curious rock formations.

Shayden at Crack in the Ground

Where did this fern blow in from? Way to the west? I salute you, brave, flying little fern.

Looks like a path in the Holy Land, or a Roman ruin….

“Crack in the Ground is a volcanic fissure that formed at the western boundary of a small graben underlying the Four Craters Lava Field. The Crack and lava field were recently dated at about 14,000 years old. The fissure is about 2 miles long and 70 feet deep, and disappears into lake sediments at its southern end. Therefore, this supports an interpretation that Lake Fort Rock rose no higher than this level in the last 14,000 years.” http://www.fortrockoregon.com/Crack.html

Although impressing my family with the gorgeousness of high desert Eastern Oregon was deeply satisfying, the best part of the visit was the conversations. Family lore was reviewed by Mary Lee, who lived it, and Elizabeth, who brought a copy of a bound books she had made of her genealogy research on the Lincolns and the Smiths (my mother’s side.) Jonah was asked about The Future of Film, and Makoto shared that he’s looking forward to his semester in Japan where he can improve his Japanese and get a bit more feeling about the land of his father’s ancestors. I didn’t actually have any deep conversations. I felt a little bit like a bride: everyone’s gathered here to see me (and my beloved), and my job is to play my role and make sure everyone has enough seltzer to drink, and a comfy clean pillow. It was enough to create the event of gathering: I hope to continue conversations with my sister, cousins, and children by phone with more depth now that we’ve seen each other in the flesh.

The family came in from Brooklyn, DC, Philadelphia, Virginia, Delaware, Albuquerque and Tucson, all very urban places. The empty expanses, and the star lit night sky, will surely stay with our visitors. Arden, Valerie’s youngest, was a firefighter in Lake County and knows a lot of cool locations, like the dry Loco Lake. He took the youngest generation to check it out on at least two nights. I was too tired. But from the photos, it looks like yet another spooky, otherworldly piece of the Oregon Outback.

Yuuki is the most photogenic creature that ever was, and was beautifully lit at Loco Lake by Jonah.

Beautiful Clara, and Jonah making Alkali Angels??

Apparently Loco Lake was a highlight for the youngest generation.

For the oldest traveler, Mary Lee, I think the best part of the trip was just seeing everyone. She’s lived and visited most of the planet, and reared her three children in New Dehli and Lebanon. She knows world history and writes plays about strong women, including Eleanor Roosevelt. She survived being widowed in her early 40s, and again in her 70s. She loves Italy, travel in general, gems, and her children and grandchildren. She loves me enough to deal with flight delays and dusty heat. She is amazing.

I was born in the evening of August 15th when Perry Mason was apparently just starting on TV. My father had just turned 30 two weeks before my arrival, and my mother was just 23. My mother passed away when she was 55, and my father after 7 years in a nursing home following a devastating stroke at age 69. Neither lived long enough to know my life as a divorced lesbian, and would have wondered at my choice to live in Paisley. Hopefully they’d have come around to my being gay, and as long as I have a job and am self sufficient, my father would have relaxed about the move. He’d also loved all the gun-toting, horse-riding republicans and he’d have adored Trump. Mom would have romanticized the First Nation people, and asked me about all the churches we’ve tried in our futile search for another St. Stephen’s. In any case, their daughters, myself and Elizabeth, are doing fine, and so are our five children. Mary Lee has 5 grandchildren, too. The 10 great grands of Ruth and Henry.

Ruth Turner, the descendant of slave owners. Henry Lincoln, cousin to the Great Emancipator. In that tension lies most of American History.

One thing that I reflect on as I think about the descendants of Ruth and Henry, is that we are committed to the social good, and to the arts. My sister is learning Healing Touch for working with animals and humans. Cousin Julie is an expert on pollinators, working against all hope for the healing of the environment with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Her sister, Targ, is a middle school guidance counselor. Brother Andrew McIntyre, who couldn’t come to Paisley, is a professor of acupuncture. Yuuki is an artist, exploring gender and the biracial life as a Japanese-American hyphenated human, with courage and sass. I’ve been a social worker for 33 years, now psychotherapist to the bruised and broken-hearted of Lake County. My daughter Clara is in charge of a tutoring site in Prince Georges County for at risk Latinx youth, using her bilingual skills to bring children and grandchildren of immigrants more opportunity through education. My son Jonah makes music videos in Brooklyn, living in what Beverly Tatum Daniel calls the borderlands where cultures complement, challenge, connect and stimulate each other. I asked him recently why he only dates women of color, particularly women of the African Diaspora. He says, they can relate to being of two cultures. Since he grew up white in a non-white world, he feels like a code switcher, too.

We are all in our own way, justice-seeking.

The other part of the birthday extravaganza was letting people give to me. Receiving. Valerie had been reading a book called, It’s Not Your Money, by Tosha Sliver, who’s an amazing writer using humor and an ecumenical lens. I started reading it, and found this prayer, which I inhaled into my heart for the awkwardness of receiving all the love of my family for my birthday.

Here I go, headlong into my 61st year, giving with complete ease and abundance, wildly open to receiving.

0 notes

Photo

OK, so basically, in theory it’s a song contest between all of the countries registered in the European Broadcasting Union. Which, weirdly, you don’t need to be in Europe to be in. So there’s always a few entrants who aren’t really considered to be in Europe. It’s basically like Tumblr. Many of the songs are the equivalent of memes or dare I say it, shitposting. You’ve got strange cultural musical references that are hard to explain to outsiders, but are often better understood by countries with more similar cultures. Just like tumblr memes are impenetrable to people who haven’t spent time on this website, so European music is pretty darn weird to somoene who’s never flipped through some European music channels.There is stuff being churned out and listened to, all the time, almost as weird as anything on Eurovision. The West just isn’t exposed to it most of the time, so it comes as a shock during Eurovision. You can’t take it too seriously. There’s generally a huge spectacle with everyone trying to be as outlandish as they can, though the winners from the year before usually have a degree of influence on what gets put forward the next year. You don’t want someone boring winning, because next year it might all be guys wearing black t shirts and fedoras strumming on guitars. There may be a political element on top of that; there’s always something slightly controversial. However it’s often misunderstood by Western commentators who assume that half the countries are in cahoots with the other half, and often have a poor knowledge of sociopolitical relations between neighboring states. In reality, neighboring countries often have a large diaspora population from their neighbours, as well as similar languages and cultures to the point where they enjoy music by each others’ artists. It’s a time when people who can’t find half the countries on the map suddenly think themselves political experts, and as someone who hails from the other side of Europe, that aspect gets a bit tiring. The Brits, in particlar never seem to understand this, probably because their nearest neighbours are the French (who they hate) and the Irish (who hate them), and for the most part our cultural neighbours aren’t in Eurovision. Britain usually puts forward artists that nobody ever listens to in the UK, tells itself that we’re going to do well this year, takes it more seriously than it pretends, then is disappointed when the song even we wouldn’t listen to, isn’t particularly liked by the rest of Europe. Brits like to complain that nobody likes us. We invaded half the world, that’d probably be deserved, but it’s not true. It’s more that Britain rarely gets into the spirit of Eurovision. It’s not about winning through musical artistry or proving a political point, it’s about putting forward something weird and occasionally brilliantly weird (or somehow decent) that shows a little bit of the culture of your country. Then it gets written off as some kind of political voting conspiracy. Whereas the reality is that European music is varied, weird, sometimes bloody awful, and genuinely sometimes just a hilarious European equivalent to shitposting that shouldn’t be taken too seriously.

Eurovision really is a WILD time

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Year in Review - Books I Read In 2016

In between writing three books this year, I read a hundred or so book-equivalents of other people's work. About half of these were read while traveling; I read fast and spent a lot of this year on or waiting for airplanes. Most of these are extremely old and not many of them were great, but casting a wide net can produce unexpected results; 2017 just from what I already have available is going to likely be dominated by more Gutenberg-grinding, but I'm also going to try to get farther outside the box and continue to work on picking up more diverse and widespread influences.

John Buchan - Witch Wood Buchan took a long leap away from his typical hard-bitten inter-war suspense plots for this historical romance set in 17th century Scotland, a time of witch hunts, plague, and disputes between hardcore Calvinists and even-crazier hardcore Calvinists that occasionally flared up into actual civil war. The language is a little clunky, and there is a lot of impenetrable Scots dialect that isn't translated, but in terms of total quality it's not greatly different from his Hannay stuff. If you like Buchan's pacing, but tend to lose patience with the public-school-Toryism of a lot of his lead characters, you might want to take a look at this one, which is far enough removed from modern politics that he's out of that mode. He only did something like this the once, so it maybe wasn't a commercially-successful experiment, but it's an interesting one all the same.

Abraham Merritt - various short stories While cleaning up my pile of Gutenberg Australia texts, I read through a bunch of Merritt's stuff. The quality was kind of intermittent, but what really struck me was how relatively non-racist it was, for a guy in this time period writing through a bunch of east-Asian subjects. Edgar Wallace or Edgar Rice Burroughs would have been terrible on this stuff. The best one of these stories is probably "The Fox Woman", with "The Women of the Wood" being pretty solid as well. "The Drone" is a little disposable, "The People of the Pit" is a worse version of Lovecraft's "At The Mountains of Madness", and "Through the Dragon Glass" is trying too hard, dumping in a bucket of Orientalist cliches where a teaspoon would have been enough.

Ellis Parker Butler - Philo Gubb, collected More people should be more aware of the adventures of Philo Gubb, the determined-but-derpy detective and wallpaper-hanger from Riverside, Iowa. A lot of people parody Sherlock Holmes, but what Parker Butler's parodying here is Holmes mania. Step by step, Gubb actually does solve his mysteries like a less hilarious detective; he's just living in the universe of absurdity that comes with being a wallpaper installer with a correspondence-school detective certificate as a main character. The twist endings are all pretty clever, and the dialect in dialogue doesn't obstruct the humor; of these, the "Greatest Case" is probably the best, for both its extremely well-crafted setup, and then the hilarious end where Gubb literally falls ass backward into the resolution of the case.

Joseph Conrad - A Set of Six This was the first larger thing that I completely finished reading in 2016; if I recall correctly, I started Witch Wood at the very end of '15. There are some parts that felt like a re-read, but you read a lot of Conrad getting a reasonable education in the English-speaking world, so that might have been it; some of these are probably in Tales of Unrest, another collection I read back in '13. This is one of his classic collections, and it definitely earns it: "Gaspar Ruiz" is not the strongest, and is overwrought in the way that people who don't like Conrad frequently criticize him for being, but "The Informer" and "An Anarchist" should be mandatory, and "The Duel" is good not just for the psychological characterizations, but in the way that he weaves in and presents the whole Napoleonic era.

L. Roy Terwilliger - Cuban Folk-Lore My dad sent me this ethnographic thing at the end of January for little immediately-discernable reason, and since it was short and I had some time burning backups, I read it down. I got a couple ideas out of it, but it's wicked old (late 19th century, probably before the American conquest), as racist as anything from that time period and with the usual intermittent methodology and absent sourcing, and the actual content describing local practices is not enormously novel to someone who's even a little familiar with Afro-Catholic syncretic practices from the Caribbean. It's short, though, so that's maybe something.

Joseph Conrad - Twixt Land and Sea I finished this faster than I thought I would, again at the laundromat, and can heartily recommend it. "The Secret Sharer" is in here, for one, and that should be enough, but the final story, "The Lady of the Isles", is a damn masterpiece. It's still, as noted above, a little wrought in places, but Conrad's language, man, his knack of locating exactly the perfect word in his fourth goddamn language to build exactly the right impression -- even if his psychology can get a little wrought, it's worth reading Conrad just to read him. And -- and this sticks out especially in this last tale -- in Conrad as in very, very few of his contemporaries, stylistic or chronological, everybody in the story is always a fully-paid-up human being. The men, of whatever nation, the women, the "natives" -- they all have their foibles and their failings, but they're all fully human and always worthy of the reader or the narrator's respect. If Conrad in himself isn't enough to get you to read him, that bit ought to be: and the rewards will pay off, intensely.

Shelagh Delaney - A Taste of Honey I read this as a consequence of doing research for a Linksshifter story, and enjoyed it well enough, even though it really needs a director's hand to transform the lines and inconsistent, weirdly placed directions into an actual dramatic performance. While the hellish conditions of pre-slum-clearance Salford are no longer current, I've seen enough historical stuff from the bad parts of Glasgow at the time the play was written to fill them in, and I seriously know like all of the main characters in this story. Jimmie and Geoff are fairly stock and generic, but Helen, Jo, and Peter are real people I could easily cast just from the circles of people I know from the north of England and the Irish diaspora. Maybe that gives it more kick than it might have for other people, but at least from my perspective this is more than just a kitchen-sink drama.

Piotyr Kropotkin - Mutual Aid This took up most of February and nearly all of March at the laundromat, but is well worth the long, long read. Some of Kropotkin's zoology is a little shaky, and his ethnography and sociology are probably out of date, but this isn't a textbook, and wasn't even when it was written. If you don't take it too literally, though, this is a treasure trove of practical, well-referenced information supporting the now well-populated fields of inquiry into cooperation and altruism in biological evolution and human society. Not all of it is correct or complete, but the sheer volume of evidence crushes the life out of Spencerian/social-Darwinist arguments as not remotely correct or complete either. That this is normal and familiar instead of revolutionary is just an indication of how much better we've gotten, in the last hundred or so years, at not being dicks to each other out of misunderstood interpretations of science.

Piotyr Kropotkin - The Conquest of Bread The style of this tract has oddly aged better than the content. Kropotkin's rigorous anti-racism and anti-sexism put him streets ahead of nearly all his contemporaries, but his ideas about how agriculture works were at the trailing edge even at the time. The heart of the agro-mech revolution then in process -- admittedly not in Russia, where he did most of his field observation -- was that people who were specialists in their fields could increase production by knowing the fields and machinery inside and out, and Kropotkin wants to change that out for mechanics and professors and ditch-diggers working rotating part-time shifts. This is dumb, but the basic idea -- that work and production and opportunity should be spread as evenly as possible -- is still relevant. The moment of anarchism has probably passed, but the post-scarcity, post-employment society is still coming, and if we don't put in some kind of implementation of Kropotkin's ideas, we're going to be looking up at this book instead of down.

Piotyr Kropotkin - The Place of Anarchism In Socialistic Evolution A speech or tract rather than a full book, this still was on my Kindle this year and still got read. As always, Kropotkin glosses over how independent organization is supposed to guarantee fair distribution of stuff without turning into government or corporations, but the principles are sound and vital: that what we want to do is get away from a society where people devour each other and toward one based on being nice to other people via education and more cultural interconnections, to make sure that where there is no scarcity, no one is deprived, and to reduce crime and social problems by reducing inequality. There is still no implementation in any of this, but when capitalists and governments alike are seriously mooting the idea of basic income as a real, humane replacement for employment in automated-out jobs and the current paternalistic, judgy, inadequate safety net, it's definitely time for another look at Kropotkin.

Laurence Donovan - Moon Riders Stepping around actually naming the Klan, this novella is the FBI versus the Klan in a little town in the mountain West circa 1920; taut and relentlessly violent, it was a nice palate cleanser after nearly two solid months of academic anarchism. The characters are mostly cardboard, and the love interest is transparent, circumstantial, and virtually unnecessary, but this is pulp, and pulp gon pulp. It's pretty good pulp for all that, though, and a quick read regardless.

Laurence Donovan - Pin Up Girl Murders This story is too busy for its wordcount: ramming a spy heist, a murder, another incidental killing, and two love-affair betrayals into barely enough pages for a novella makes everything far too complicated, and there is too much twee drawing-room-detective bullshit in it to fit either the space constraints on the narrative or Donovan's two-fisted, red-blooded style. You can barely do a mystery where forensics are relevant in this little space, and dumping a bunch of wordcount on setting up the love triangles does not help. This is disordered crap that keeps tripping over its own feet.

Minna Sundberg - Stand Still, Stay Silent Book 1 As awesome as SSSS is on the internet, it is even more beautiful on the printed page -- and in this form, the prologue especially hits like a ton of bricks. This is barely the start of a story that continues to build and grow, but this tome doesn't need to wait for the rest of it to be complete. Sundberg's infinite passion for scene painting rules all and pops from cover to cover; the story, good as it is, is almost incidental to the art. SSSS isn't ideally perfect (that Washington Post award was a make-up call for passing on A Redtail's Dream, not for this still-unfinished work), and people coming into the story cold will probably notice a lot of stuff in the prologue that can be read much more darkly about author intent than is likely to be the case, but if you can get past that, there's a lot of reward waiting here.

Laurence Donovan - Whispering Death I have some longer-form Donovan that is not loaded up yet, and after this one, I really want to get to it and see what he can do when he doesn't have to go backwards. The constraint of pulp writing means that you have to start with a hook or sting -- like here, a shot-up patrol face-down in no-man's-land with German bullets whistling over their heads -- but in the middle of that action Donovan has to back up via flashback to do his love interest, and this really breaks up the flow of the narration. This one's good enough, but if there was more forward or just less backward, it would turn out better.

Marie Corelli - A Romance of Two Worlds I'd loaded Corelli's works onto my device for the Russia trip three years ago, but only gotten to the first of them, this one, just now. It's very easy to write off her style and subjects as overblown and tired theosophic crap -- the mystic, gnostic "Electric Christianity" in this one could have been written as a satire of the new religious movements between 1848 and 1914 -- but there's good stuff in here as well. Corelli wasn't writing a lesbian relationship between Zara and the narrator, but I defy modern audiences to read it as anything but; as a male writer, reading women writing women in love with women gives me a perspective that's distinctly outside my experience -- one reason among many that I need to read more women more often. I read enough crap male writers: not reading women writers because they happen to be mawkish theosophical women writers isn't going to wash. That said, this book is about three books glued together badly, and full of poorly-reasoned gnostic garbage and bad science. If you have better woman writers at your disposal, read their stuff first.

Perley Poore Sheehan - Captain Trouble A marginally bearable hodgepodge of orientalist crap written at about a fourth-grade level that will frequently sound hilarious to the modern ear (if you know, like, anything about China and/or central Asia at all), the Captain Trouble stories are not quite at the Dan-Brown "The famous man looked at the red cup" level of shittiness, but an author who can put up "The Chuds ate human flesh. The Chuds lived in caves. The Chuds were a cross of bears and bats." as consecutive sentences is getting pretty damn close. You will get a brain cramp if you read too much of this; as far as I can tell, the correct order (I got these from Gutenberg and had to re-collect them) should be something like: The Fighting Fool Where Terror Lurked The Red Road to Shamballah The Green Shiver Spider Tong The Black Abbot The Chinese in use throughout these stories is somewhere between "archaic", "geographically inappropriate", "mistranslated", and "plain wrong", but occasionally you can see what Sheehan was going for and how he got it right, or almost did in his poorly-preserved pinyin. The racism is mostly of the "funny foreigners" type rather than the kick-em-while-they're-down shit; these features combine for a story cycle that is today still antiquated and problematic, but was a goddamned model of progress and equality in its time and pulp context.

Perley Poore Sheehan - Monsieur de Guise A bare sketch of fantasy, this space-filling creeper is probably not worth your attention. Sheehan is not great at description generally, and his American swamp feels less real than his Chinese deserts. This does not have a lot going for it other than being short and probably can be safely skipped.

Perley Poore Sheehan - Kwa and the Ape People On the surface, this is yet another wannabe Tarzan, thoroughly possessed of the racist conceit that white people are so super-awesome that, if brought up in "savage" circumstances, they will necessarily become super god-heroes in that world. And yet, this is infinitely better than Tarzan on the axes of taking Africans seriously as human beings, and of not treating African animals as monsters or an inexhaustible font of murder victims. The fight with Sobek that opens the book is a great piece of naturalistic writing, from observation and from the literature on crocodilians, and later parts that are more spoilery to discuss here show that Sheehan was willing to put in the work on at least some bits of African folklore and language rather than just making shit up. Burroughs got in first and poisoned the well, but of the lesser Tarzans, Kwa is the best I've encountered so far.

Perley Poore Sheehan - Kwa and the Beast Men Well, that didn't last too long. This shorter Kwa adventure is purer Tarzan-ripoff shit, probably from commercial considerations; pulp audiences didn't want to read about real animals or real anthropology, they wanted to see White Dudes kicking the shit out of Darkest Africa. Sheehan's patent inability to describe things leaves you with zero picture of the Beast Men from the title, despite the huge role they play in the narrative; the lack of any kind of structure in the animal-telepathy bits is similarly unhelpful. Ignore this garbage, re-read ...Ape People.

Stanley G. Weinbaum - Parasite Planet I was initially pretty hot about some bad mistakes in the science up front (Venus is not tidally locked to the Sun), but got over it (this wasn't discovered until radar astronomy came in in the '60s) and eventually warmed up to this formulaic but well-done adventure of life on the rocket frontier. The world-building is good and seldom overruns the narrative, and while the gender roles are pretty '40s, at least it's not '20s. If I can keep getting relatively solid science and relatively good writing, it's going to be a good thing I've got more Weinbaum on the stack.

Stanley G. Weinbaum - Proteus Island Back on earth, Weinbaum can't avoid the taint of the racism of his day, which may make the start and the abuse of the Maori guides a little hard to take. However, if you fight through it, you get a really neat story about biological variation with some, as usual, nearly correct science at the foot of the science fiction. I'm not a fan of the "explain everything in the epilogue" school, but it does tie up a lot of the mystery here; if more of this could have been done in-narration and a harder climax hit, this story would probably work better. Maybe back in the day people put up with more falling action generally, dunno.

Stanley G. Weinbaum - Pygmalion's Spectacles A really neat story, this one takes advantage of multiple psychological elements -- set up, significantly, by reading a lot of contemporary SF and fantasy (in particular H.G. Wells) -- to become significantly better than it appears to be by a very cool twist ending. If you need an in to Weinbaum, this isn't a bad place at all to start.

Stanley G. Weinbaum - Redemption Cairn If you know LITERALLY ANYTHING AT ALL about how narrative works, you will figure out the important part of this rocket noir's ending pretty much as soon as it's introduced. That said, it's a fun read after you accept the relentless sexism as just going with the territory, and Weinbaum's trademark Almost Correct Science is well-built-out here to furnish an alien world and a moderately hard vision of rocket mechanics. It could be more progressive, sure, but this is of an age with Radar Men From The Moon, where women went to space literally because the men needed someone to cook for them.

Stanley G. Weinbaum - Shifting Seas If a lot of Weinbaum has aged poorly -- overtaken by more modern science and more modern ideas about people who aren't white males being fully qualified humans -- this has if anything improved. The ending gets a little into Wellsian utopianism, but the immediacy of the climate-change and geoengineering plot could have been ripped from tomorrow's headlines. More of the science is right here than in many other parts, and the telling of the tale doesn't lack either.

Stanley G. Weinbaum - The Adaptive Ultimate I am the wrong person to unpack Weinbaum's rather deep weirdness about women; if this sort of thinking was general back in the day, it is no wonder that a herd of neuroses flourished and psychotherapy became popular. This tale is less sexist than most of his other ones, the science approximately correct, and in its own way it's probably the most self-sufficient of these... ...but, owing to that weirdness, should not be the only Weinbaum story you read.

Stanley G. Weinbaum - The Brink of Infinity Send this one to your high school math students. This is less a story than a logical exercise, a parable like Einstein's teachers used to explain algebra. I've written stories like this one to test job applicants on their background in algorithms; this one provides the answers to that test, and is a pretty neat study in mathematical thinking by exclusions. The terminology may be a little out of date, but the fundamentals are all right, and they make the story pop the way it's supposed to.

Stanley G. Weinbaum - The Circle of Zero In the modern day, this story would be spun up from many-worlds quantum and make dumb references to Roko's Basilisk. This is marginally more right than the interpretation of the laws of probability used to set the stage here, but that's not the point. The trick works as well in either context, and Weinbaum's hand for the eerie in the narrator's visions doesn't fail. Another good one.

Stanley G. Weinbaum - The Ideal Weinbaum has some good characters in this one, but the early-20th-century sexual weirdness has the narrative tripping all over itself from a modern perspective, twisting and mutilating into desperately strange corners. There's some good stuff in here, but a lot of Weinbaum's work is a lot better than this.

Stanley G. Weinbaum - The Lotus Eaters If you can make it through the negging field in here (seriously, did people use to act like this on purpose?), you will find probably Weinbaum's best work. The exobiology is, in light of modern cladistic ideas, pretty dumb and wrong-headed, but the plot and the particulars are rock-solid and relentlessly imaginative. Read this after Parasite Planet for narrative reasons; it's a rare example where the sequel's better than the original.

Stanley G. Weinbaum - The Mad Moon Weinbaum's world-building, good elsewhere, is absolutely excellent here, a jewel of alien environments and future society that would be worth reading even if he hadn't managed to dial the usual sexism down to levels approaching those of modern content. The story in amid the setting is good too, and if you're paying careful attention, you can see the elements and corners of other parts of Weinbaum's ouevre; he'd obviously plotted out his solar system of tomorrow outside the printed pages, keeping everything consistent to make sure things linked up right, and that all of these stories had a common base to build from. The craft is awe-inspiring; the art built on it covers joy.

Stanley G. Weinbaum - The Point of View Another van Manderpootz comic adventure, this one works better than "The Ideal", and clarified the points in that one that seemed missing; there's a predecessor to both of these stories, hopefully in the queue somewhere, and both Dixon and the Professor gain by being repeating characters reacting to different situations. This one is good enough to justify reading the rest of them in order -- and in that progression, perhaps, we may find Weinbaum working his way out to less mental attitudes about women in full.

Stanley G. Weinbaum - The Worlds of If That first van Manderpootz adventure? Well, here it is, and a much better start it makes than "The Ideal". Maybe some of this is coming back with the formula in mind, and it's not as good as this series got as late as "The Point of View", but the quantum is nearly correct, the sexual politics not unduly problematic, and the writing just as comic as Weinbaum can be at his best.