#eurasian woodcock

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Biro studies of a little woodcock I had the pleasure of meeting. Strangely, woodcocks’ ears are directly underneath their eyes!

#woodcock#Eurasian woodcock#biro#pen#drawing#sketch#animal art#artists on tumblr#sketches#bird art#bird ringing#bird

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

The American woodcock gets a lot attention online for being an insanely swag beast so I'd like to inform my fellow eurasians that we also have one of these guys over here

This here is the Eurasian woodcock everyone say hi Eurasian woodcock

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

a eurasian woodcock (scolopax rusticola) performing its roding display flight at dusk in ireland

#charadriiformes#scolopacidae#scolopax#eurasian woodcock#woodcock#birds#birdwatching#bird photography#display flight#SO HYPED ABOUT THIS!!!#only my second time seeing them roding#didn't capture its noise but they make grunts like a pig or frog and then a really loud squeak#they are sooooo cool i'm so happy to have seen this!!!

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

today, yet another poor unknowing soul has fallen for my eurasian woodcock propaganda trap

#have you heard of our lord and saviour eurasian woodcock ?#now you have! here’s a video#the way they’re called SLANKA here#these lil dudes bring me So Much Joy#eurasian woodcock#american woodcock

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

a story that happened a few days ago!

so i was coming home from a walk and saw this bird that i’ve only seen pictures of before near an apartment building, tried to approach him because i wanted to send a photo to my friends and ask them to remind me what he’s called, but i accidentally startled him. he tried to fly off but crashed into a window and fell down. me and another person rushed over to him, fearing the worst. thankfully, he was alive but seemed confused. we weren’t sure if he was hurt badly enough to not be able to fly away so we just carried him to a quiet wooded area where feral cats don’t roam (picture 1) and let him go. later i came back to check on him alone and found him in the same area, just walking around, but he couldn’t fly, it seemed like he was hurt after all. it was a really cold day so i decided that i wasn’t going to just leave him there and let him freeze to death, die of starvation or be attacked by some animal. i ended up contacting moscow animal control and they told me that i could try to carefully catch him and let them know of my location so they would send a person to come pick him up and bring him to a shelter where he would be nursed back to health and then released. i managed to catch him with my beanie so he would be warm while i carried him home (picture 2). then i called my grandmother, quickly explained the situation, asked her to get a cardboard box lined with something soft ready and headed home. thankfully, the bird was calm almost the entire time. i brought him home and we put him in a box with a towel in it so he would be as comfy as possible. i sat with him in the hallway for like an hour until the guy from animal control arrived to pick him up. he quickly checked the birdie for injuries, didn’t find anything life-threatening and said that he’ll be ok. i’m planning to call him and ask how the bird is doing :)

by the way, this bird is called a woodcock, i think that this is an eurasian woodcock (scolopax rusticola) specifically! it’s currently the migratory period for them and they often end up resting in cities when they get tired. unfortunately, this sometimes ends with them getting hurt for various reasons. but this one should be alright. i’m just glad that i could help this adorable little thing. hopefully i will get an update about him!

#what do i tag this#uhhhhhhhhh#bird#woodcock#eurasian woodcock#im sorry i need everyone to look at him because hes cute#felix meows#pic#long post

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

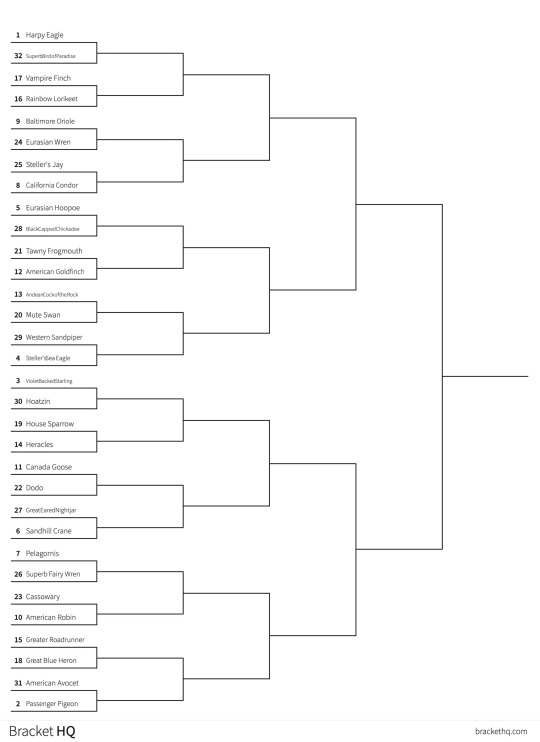

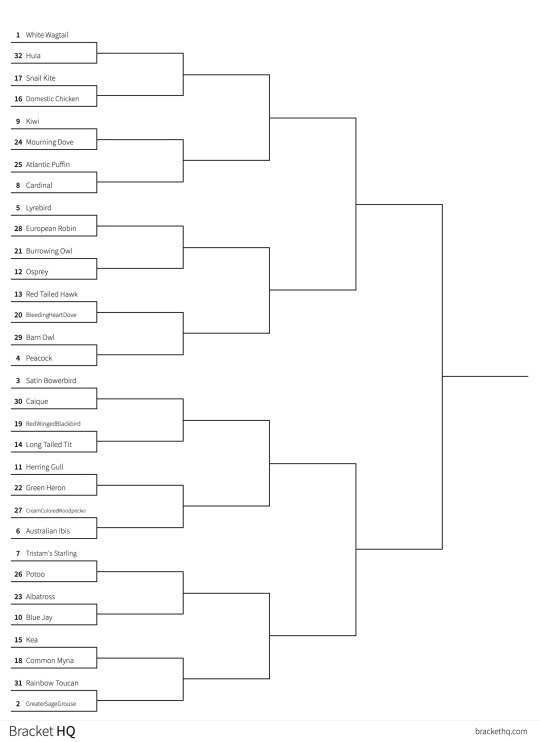

Alrighty and HERE ARE OUR CONTENDERS!!!

Tag for the polls: #bird battle

DISCLAIMER - I wrote the round one blurbs when I was very sick and half awake, so if you see any mistakes PLEASE TELL ME! Nicely, obviously, but I want to make sure they sound good for round 2. Thank you!

I know there’s a lot of them, but man there’s SO MANY GOOD BIRDS! There were a few times where people didn’t put what specific subspecies for some birds, so sometimes I’d have to choose one. I tried to choose one that represents that bird the best!

I don’t know when the polls will begin, I’m doing some research on the birds so that people can read about them before they vote.

If one of your favs didn’t make it in, don’t worry they’re a winner in my and your heart.

If you are wondering where the Pigeon (Rock Dove) is, THEY ARE THE FINAL CHAMPION! At the end of this bracket, the winner will face off against the mightily popular Rock Dove! Will they be able to beat such a tough challenger? We will see…

Also, a note on how I set this bracket up: I put all the birds in a numbered list and then used a number generator. I think the matchups we got were really interesting.

Full list under the cut

HARPY EAGLE

SUPERB BIRD OF PARADISE

VAMPIRE FINCH

RAINBOW LORIKEET

BALTIMORE ORIOLE

EURASIAN WREN

STELLER'S JAY

CALIFORNIA CONDOR

EURASIAN HOOPOE

BLACK CAPPED CHICKADEE

TAWNY FROGMOUTH

AMERICAN GOLDFINCH

ANDEAN COCK OF THE ROCK

MUTE SWAN

WESTERN SANDPIPER

STELLER'S SEA EAGLE

VIOLET BACKED STARLING

HOATZIN

HOUSE SPARROW

HERACLES

CANADIAN GOOSE

DODO

GREAT EARED NIGHTJAR

SANDHILL CRANE

PELAGORNIS

SUPERB FAIRY WREN

SOUTHERN CASSOWARY

AMERICAN ROBIN

GREATER ROADRUNNER

GREAT BLUE HERON

AMERICAN AVOCET

PASSENGER PIGEON

WALLCREEPER

GREAT TIT

MOA

EASTERN BLUEBIRD

AUSTRALIAN BUSHTURKEY

EMU

MALLARD DUCK

FLAME BOWERBIRD

MANDARIN DUCK

BELTED KINGFISHER

OILBIRD

FAIRY PENGUIN

LESSER FLAMINGO

AUSTRALIAN KESTREL

CARRION CROW

UMBRELLABIRD

LOGGERHEAD SHRIKE

PERUVIAN PELICAN

CALIFORNIA QUAIL

MACGREGORS BOWERBIRD

HARRIS HAWK

COMMON RAVEN

BEARDED VULTURE

PEREGRINE FALCON

ROSY LOVEBIRD

ROSEATTE SPOONBILL

LONG TAILED GRACKLE

AMERICAN WOODCOCK

KAKAPO

BLUE FOOTED BOOBY

RHEA

BEE HUMMINGBIRD

WHITE WAGTAIL

HUIA

SNAIL KITE

DOMESTIC CHICKEN

KIWI

MOURNING DOVE

ATLANTIC PUFFIN

CARDINAL

LYREBIRD

EUROPEAN ROBIN

BURROWING OWL

OSPREY

RED TAILED HAWK

BLEEDING HEART DOVE

BARN OWL

PEACOCK

SATIN BOWERBIRD

CAIQUE

RED WINGED BLACKBIRD

LONG TAILED TIT

HERRING GULL

GREEN HERON

CREAM COLORED WOODPECKER

AUSTRALIAN IBIS

TRISTAM'S STARLING

POTOO

WANDERING ALBATROSS

BLUE JAY

KEA

COMMON MYNA

RAINBOW TOUCAN

GREATER SAGE GROUSE

TURKEY VULTURE

TUFTED TITMOUSE

CRESTED AUKLET

EURASIAN MAGPIE

BUDGIE

SCREECH OWL

WIP-POOR-WILL

SECRETARY BIRD

AUSTRALIAN MAGPIE

CEDAR WAXWING

VICTORIA CROWNED PIGEON

HERMIT THRUSH

COMMON SWIFT

WHITE BELLBIRD

BROWN SKUA

EUROPEAN DIPPER

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Love Dick And Balls

The American woodcock (Scolopax minor), sometimes colloquially referred to as the timberdoodle,[2] is a small shorebird species found primarily in the eastern half of North America. Woodcocks spend most of their time on the ground in brushy, young-forest habitats, where the birds' brown, black, and gray plumage provides excellent camouflage.

The American woodcock is the only species of woodcock inhabiting North America.[3] Although classified with the sandpipers and shorebirds in the family Scolopacidae, the American woodcock lives mainly in upland settings. Its many folk names include timberdoodle, bogsucker, night partridge, brush snipe, hokumpoke, and becasse.[4]

The population of the American woodcock has fallen by an average of slightly more than 1% annually since the 1960s. Most authorities attribute this decline to a loss of habitat caused by forest maturation and urban development. Because of the male woodcock's unique, beautiful courtship flights, the bird is welcomed as a harbinger of spring in northern areas. It is also a popular game bird, with about 540,000 killed annually by some 133,000 hunters in the U.S.[5]

In 2008, wildlife biologists and conservationists released an American woodcock conservation plan presenting figures for the acreage of early successional habitat that must be created and maintained in the U.S. and Canada to stabilize the woodcock population at current levels, and to return it to 1970s densities.[6] Description

The American woodcock has a plump body, short legs, a large, rounded head, and a long, straight prehensile bill. Adults are 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) long and weigh 5 to 8 ounces (140 to 230 g).[7] Females are considerably larger than males.[8] The bill is 2.5 to 2.8 inches (6.4 to 7.1 cm) long.[4] Wingspans range from 16.5 to 18.9 inches (42 to 48 cm).[9] Illustration of American woodcock head and wing feathers Woodcock, with attenuate primaries, natural size, 1891

The plumage is a cryptic mix of different shades of browns, grays, and black. The chest and sides vary from yellowish-white to rich tans.[8] The nape of the head is black, with three or four crossbars of deep buff or rufous.[4] The feet and toes, which are small and weak, are brownish gray to reddish brown.[8] Woodcocks have large eyes located high in their heads, and their visual field is probably the largest of any bird, 360° in the horizontal plane and 180° in the vertical plane.[10]

The woodcock uses its long, prehensile bill to probe in the soil for food, mainly invertebrates and especially earthworms. A unique bone-and-muscle arrangement lets the bird open and close the tip of its upper bill, or mandible, while it is sunk in the ground. Both the underside of the upper mandible and the long tongue are rough-surfaced for grasping slippery prey.[4] Taxonomy

The genus Scolopax was introduced in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.[11] The genus name is Latin for a snipe or woodcock.[12] The type species is the Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola).[13] Distribution and habitat

Woodcocks inhabit forested and mixed forest-agricultural-urban areas east of the 98th meridian. Woodcock have been sighted as far north as York Factory, Manitoba, and east to Labrador and Newfoundland. In winter, they migrate as far south as the Gulf Coast of the United States and Mexico.[8]

The primary breeding range extends from Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick) west to southeastern Manitoba, and south to northern Virginia, western North Carolina, Kentucky, northern Tennessee, northern Illinois, Missouri, and eastern Kansas. A limited number breed as far south as Florida and Texas. The species may be expanding its distribution northward and westward.[8]

After migrating south in autumn, most woodcocks spend the winter in the Gulf Coast and southeastern Atlantic Coast states. Some may remain as far north as southern Maryland, eastern Virginia, and southern New Jersey. The core of the wintering range centers on Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.[8] Based on the Christmas Bird Count results, winter concentrations are highest in the northern half of Alabama.

American woodcocks live in wet thickets, moist woods, and brushy swamps.[3] Ideal habitats feature early successional habitat and abandoned farmland mixed with forest. In late summer, some woodcocks roost on the ground at night in large openings among sparse, patchy vegetation.[8]Courtship/breeding habitats include forest openings, roadsides, pastures, and old fields from which males call and launch courtship flights in springtime. Nesting habitats include thickets, shrubland, and young to middle-aged forest interspersed with openings. Feeding habitats have moist soil and feature densely growing young trees such as aspen (Populus spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and mixed hardwoods less than 20 years of age, and shrubs, particularly alder (Alnus spp.). Roosting habitats are semiopen sites with short, sparse plant cover, such as blueberry barrens, pastures, and recently heavily logged forest stands.[8]

Migration

Woodcocks migrate at night. They fly at low altitudes, individually or in small, loose flocks. Flight speeds of migrating birds have been clocked at 16 to 28 mi/h (26 to 45 km/h). However, the slowest flight speed ever recorded for a bird, 5 mi/h (8 km/h), was recorded for this species.[14] Woodcocks are thought to orient visually using major physiographic features such as coastlines and broad river valleys.[8] Both the autumn and spring migrations are leisurely compared with the swift, direct migrations of many passerine birds.

In the north, woodcocks begin to shift southward before ice and snow seal off their ground-based food supply. Cold fronts may prompt heavy southerly flights in autumn. Most woodcocks start to migrate in October, with the major push from mid-October to early November.[15] Most individuals arrive on the wintering range by mid-December. The birds head north again in February. Most have returned to the northern breeding range by mid-March to mid-April.[8]

Migrating birds' arrival at and departure from the breeding range is highly irregular. In Ohio, for example, the earliest birds are seen in February, but the bulk of the population does not arrive until March and April. Birds start to leave for winter by September, but some remain until mid-November.[16] Behavior and ecology Food and feeding American woodcock catching a worm in a New York City park

Woodcocks eat mainly invertebrates, particularly earthworms (Oligochaeta). They do most of their feeding in places where the soil is moist. They forage by probing in soft soil in thickets, where they usually remain well-hidden. Other items in their diet include insect larvae, snails, centipedes, millipedes, spiders, snipe flies, beetles, and ants. A small amount of plant food is eaten, mainly seeds.[8] Woodcocks are crepuscular, being most active at dawn and dusk. Breeding

In spring, males occupy individual singing grounds, openings near brushy cover from which they call and perform display flights at dawn and dusk, and if the light levels are high enough, on moonlit nights. The male's ground call is a short, buzzy peent. After sounding a series of ground calls, the male takes off and flies from 50 to 100 yd (46 to 91 m) into the air. He descends, zigzagging and banking while singing a liquid, chirping song.[8] This high spiralling flight produces a melodious twittering sound as air rushes through the male's outer primary wing feathers.[17]

Males may continue with their courtship flights for as many as four months running, sometimes continuing even after females have already hatched their broods and left the nest. Females, known as hens, are attracted to the males' displays. A hen will fly in and land on the ground near a singing male. The male courts the female by walking stiff-legged and with his wings stretched vertically, and by bobbing and bowing. A male may mate with several females. The male woodcock plays no role in selecting a nest site, incubating eggs, or rearing young. In the primary northern breeding range, the woodcock may be the earliest ground-nesting species to breed.[8] Woodcock chick in nest Downy young are already well-camouflaged.

The hen makes a shallow, rudimentary nest on the ground in the leaf and twig litter, in brushy or young-forest cover usually within 150 yd (140 m) of a singing ground.[4] Most hens lay four eggs, sometimes one to three. Incubation takes 20 to 22 days.[3] The down-covered young are precocial and leave the nest within a few hours of hatching.[8] The female broods her young and feeds them. When threatened, the fledglings usually take cover and remain motionless, attempting to escape detection by relying on their cryptic coloration. Some observers suggest that frightened young may cling to the body of their mother, that will then take wing and carry the young to safety.[18] Woodcock fledglings begin probing for worms on their own a few days after hatching. They develop quickly and can make short flights after two weeks, can fly fairly well at three weeks, and are independent after about five weeks.[3]

The maximum lifespan of adult American woodcock in the wild is 8 years.[19] Rocking behavior American woodcocks sometimes rock back and forth as they walk, perhaps to aid their search for worms.

American woodcocks occasionally perform a rocking behavior where they will walk slowly while rhythmically rocking their bodies back and forth. This behavior occurs during foraging, leading ornithologists such as Arthur Cleveland Bent and B. H. Christy to theorize that this is a method of coaxing invertebrates such as earthworms closer to the surface.[20] The foraging theory is the most common explanation of the behavior, and it is often cited in field guides.[21]

An alternative theory for the rocking behavior has been proposed by some biologists, such as Bernd Heinrich. It is thought that this behavior is a display to indicate to potential predators that the bird is aware of them.[22] Heinrich notes that some field observations have shown that woodcocks will occasionally flash their tail feathers while rocking, drawing attention to themselves. This theory is supported by research done by John Alcock who believes this is a type of aposematism.[23] Population status

How many woodcock were present in eastern North America before European settlement is unknown. Colonial agriculture, with its patchwork of family farms and open-range livestock grazing, probably supported healthy woodcock populations.[4]

The woodcock population remained high during the early and mid-20th century, after many family farms were abandoned as people moved to urban areas, and crop fields and pastures grew up in brush. In recent decades, those formerly brushy acres have become middle-aged and older forest, where woodcock rarely venture, or they have been covered with buildings and other human developments. Because its population has been declining, the American woodcock is considered a "species of greatest conservation need" in many states, triggering research and habitat-creation efforts in an attempt to boost woodcock populations.

Population trends have been measured through springtime breeding bird surveys, and in the northern breeding range, springtime singing-ground surveys.[8] Data suggest that the woodcock population has fallen rangewide by an average of 1.1% yearly over the last four decades.[6] Conservation

The American woodcock is not considered globally threatened by the IUCN. It is more tolerant of deforestation than other woodcocks and snipes; as long as some sheltered woodland remains for breeding, it can thrive even in regions that are mainly used for agriculture.[1][24] The estimated population is 5 million, so it is the most common sandpiper in North America.[17]

The American Woodcock Conservation Plan presents regional action plans linked to bird conservation regions, fundamental biological units recognized by the U.S. North American Bird Conservation Initiative. The Wildlife Management Institute oversees regional habitat initiatives intended to boost the American woodcock's population by protecting, renewing, and creating habitat throughout the species' range.[6]

Creating young-forest habitat for American woodcocks helps more than 50 other species of wildlife that need early successional habitat during part or all of their lifecycles. These include relatively common animals such as white-tailed deer, snowshoe hare, moose, bobcat, wild turkey, and ruffed grouse, and animals whose populations have also declined in recent decades, such as the golden-winged warbler, whip-poor-will, willow flycatcher, indigo bunting, and New England cottontail.[25]

Leslie Glasgow,[26] the assistant secretary of the Interior for Fish, Wildlife, Parks, and Marine Resources from 1969 to 1970, wrote a dissertation through Texas A&M University on the woodcock, with research based on his observations through the Louisiana State University (LSU) Agricultural Experiment Station. He was an LSU professor from 1948 to 1980 and an authority on wildlife in the wetlands.[27] References

BirdLife International (2020). "Scolopax minor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22693072A182648054. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22693072A182648054.en. Retrieved November 13, 2021. The American Woodcock Today | Woodcock population and young forest habitat management. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03. Kaufman, Kenn (1996). Lives of North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin, pp. 225–226, ISBN 0618159886. Sheldon, William G. (1971). Book of the American Woodcock. University of Massachusetts. Cooper, T. R. & K. Parker (2009). American woodcock population status, 2009. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, Maryland. Kelley, James; Williamson, Scot & Cooper, Thomas, eds. (2008). American Woodcock Conservation Plan: A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America. Smith, Christopher (2000). Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventures Press, pp. 28–29, ISBN 1885106203. Keppie, D. M. & R. M. Whiting Jr. (1994). American Woodcock (Scolopax minor), The Birds of North America. "American Woodcock Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved September 27, 2020. Jones, Michael P.; Pierce, Kenneth E.; Ward, Daniel (2007). "Avian vision: a review of form and function with special consideration to birds of prey". Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 16 (2): 69. doi:10.1053/j.jepm.2007.03.012. Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 145. Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 351. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4. Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 278. Amazing Bird Records. Trails.com (2010-07-27). Retrieved on 2013-04-03. Sepik, G. F. and E. L. Derleth (1993). Habitat use, home range size, and patterns of moves of the American Woodcock in Maine. in Proc. Eighth Woodcock Symp. (Longcore, J. R. and G. F. Sepik, eds.) Biol. Rep. 16, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. Ohio Ornithological Society (2004). Annotated Ohio state checklist Archived 2004-07-18 at the Wayback Machine. O'Brien, Michael; Crossley, Richard & Karlson, Kevin (2006). The Shorebird Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 444–445, ISBN 0618432949. Mann, Clive F. (1991). "Sunda Frogmouth Batrachostomus cornutus carrying its young" (PDF). Forktail. 6: 77–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 28, 2008. Wasser, D. E.; Sherman, P. W. (2010). "Avian longevities and their interpretation under evolutionary theories of senescence". Journal of Zoology. 280 (2): 103. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00671.x. Bent, A. C. (1927). "Life histories of familiar North American birds: American Woodcock, Scalopax minor". United States National Museum Bulletin. Smithsonian Institution. 142 (1): 61–78. "American Woodcock". Audubon. National Audubon Society. Retrieved October 5, 2023. Heinrich, Bernd (March 1, 2016). "Note on the Woodcock Rocking Display". Northeastern Naturalist. 23 (1): N4–N7. Alcock, John (2013). Animal behavior: an evolutionary approach (10th ed.). Sunderland (Mass.): Sinauer. p. 522. ISBN 0878939660. Henninger, W. F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60. the Woodcock Management Plan. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03. [1]Paul Y. Burns (June 13, 2008). "Leslie L. Glasgow". lsuagcdenter.com. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

Further readingChoiniere, Joe (2006). Seasons of the Woodcock: The secret life of a woodland shorebird. Sanctuary 45(4): 3–5. Sepik, Greg F.; Owen, Roy & Coulter, Malcolm (1981). A Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast, Misc. Report 253, Maine Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Maine.

External linksAmerican woodcock species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology American Woodcock – Scolopax minor – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter American Woodcock Bird Sound Rite of Spring – Illustrated account of the phenomenal courtship flight of the male American woodcock American Woodcock videos[permanent dead link] on the Internet Bird Collection Photo-High Res; Article – www.fws.gov–"Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge", photo gallery and analysis American Woodcock Conservation Plan A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America Timberdoodle.org: the Woodcock Management Plan Sepik, Greg F.; Ray B. Owen Jr.; Malcolm W. Coulter (July 1981). "Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast". Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Miscellaneous Report 253. vte

Sandpipers (family: Scolopacidae) Taxon identifiers Wikidata: Q694319 Wikispecies: Scolopax minor ABA: amewoo ADW: Scolopax_minor ARKive: scolopax-minor Avibase: F4829920F1710E56 BirdLife: 22693072 BOLD: 10164 CoL: 6XXHP BOW: amewoo eBird: amewoo EoL: 45509171 Euring: 5310 FEIS: scmi Fossilworks: 129789 GBIF: 2481695 GNAB: american-woodcock iNaturalist: 3936 IRMNG: 10836458 ITIS: 176580 IUCN: 22693072 NatureServe: 2.105226 NCBI: 56299 ODNR: american-woodcock WoRMS: 159027 Xeno-canto: Scolopax-minor

Categories:IUCN Red List least concern speciesScolopaxNative birds of the Eastern United StatesNative birds of Eastern CanadaBirds of MexicoBirds described in 1789Taxa named by Johann Friedrich Gmelin

The American woodcock (Scolopax minor), sometimes colloquially referred to as the timberdoodle,[2] is a small shorebird species found primarily in the eastern half of North America. Woodcocks spend most of their time on the ground in brushy, young-forest habitats, where the birds' brown, black, and gray plumage provides excellent camouflage.

The American woodcock is the only species of woodcock inhabiting North America.[3] Although classified with the sandpipers and shorebirds in the family Scolopacidae, the American woodcock lives mainly in upland settings. Its many folk names include timberdoodle, bogsucker, night partridge, brush snipe, hokumpoke, and becasse.[4]

The population of the American woodcock has fallen by an average of slightly more than 1% annually since the 1960s. Most authorities attribute this decline to a loss of habitat caused by forest maturation and urban development. Because of the male woodcock's unique, beautiful courtship flights, the bird is welcomed as a harbinger of spring in northern areas. It is also a popular game bird, with about 540,000 killed annually by some 133,000 hunters in the U.S.[5]

In 2008, wildlife biologists and conservationists released an American woodcock conservation plan presenting figures for the acreage of early successional habitat that must be created and maintained in the U.S. and Canada to stabilize the woodcock population at current levels, and to return it to 1970s densities.[6] Description

The American woodcock has a plump body, short legs, a large, rounded head, and a long, straight prehensile bill. Adults are 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) long and weigh 5 to 8 ounces (140 to 230 g).[7] Females are considerably larger than males.[8] The bill is 2.5 to 2.8 inches (6.4 to 7.1 cm) long.[4] Wingspans range from 16.5 to 18.9 inches (42 to 48 cm).[9] Illustration of American woodcock head and wing feathers Woodcock, with attenuate primaries, natural size, 1891

The plumage is a cryptic mix of different shades of browns, grays, and black. The chest and sides vary from yellowish-white to rich tans.[8] The nape of the head is black, with three or four crossbars of deep buff or rufous.[4] The feet and toes, which are small and weak, are brownish gray to reddish brown.[8] Woodcocks have large eyes located high in their heads, and their visual field is probably the largest of any bird, 360° in the horizontal plane and 180° in the vertical plane.[10]

The woodcock uses its long, prehensile bill to probe in the soil for food, mainly invertebrates and especially earthworms. A unique bone-and-muscle arrangement lets the bird open and close the tip of its upper bill, or mandible, while it is sunk in the ground. Both the underside of the upper mandible and the long tongue are rough-surfaced for grasping slippery prey.[4] Taxonomy

The genus Scolopax was introduced in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.[11] The genus name is Latin for a snipe or woodcock.[12] The type species is the Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola).[13] Distribution and habitat

Woodcocks inhabit forested and mixed forest-agricultural-urban areas east of the 98th meridian. Woodcock have been sighted as far north as York Factory, Manitoba, and east to Labrador and Newfoundland. In winter, they migrate as far south as the Gulf Coast of the United States and Mexico.[8]

The primary breeding range extends from Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick) west to southeastern Manitoba, and south to northern Virginia, western North Carolina, Kentucky, northern Tennessee, northern Illinois, Missouri, and eastern Kansas. A limited number breed as far south as Florida and Texas. The species may be expanding its distribution northward and westward.[8]

After migrating south in autumn, most woodcocks spend the winter in the Gulf Coast and southeastern Atlantic Coast states. Some may remain as far north as southern Maryland, eastern Virginia, and southern New Jersey. The core of the wintering range centers on Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.[8] Based on the Christmas Bird Count results, winter concentrations are highest in the northern half of Alabama.

American woodcocks live in wet thickets, moist woods, and brushy swamps.[3] Ideal habitats feature early successional habitat and abandoned farmland mixed with forest. In late summer, some woodcocks roost on the ground at night in large openings among sparse, patchy vegetation.[8]Courtship/breeding habitats include forest openings, roadsides, pastures, and old fields from which males call and launch courtship flights in springtime. Nesting habitats include thickets, shrubland, and young to middle-aged forest interspersed with openings. Feeding habitats have moist soil and feature densely growing young trees such as aspen (Populus spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and mixed hardwoods less than 20 years of age, and shrubs, particularly alder (Alnus spp.). Roosting habitats are semiopen sites with short, sparse plant cover, such as blueberry barrens, pastures, and recently heavily logged forest stands.[8]

Migration

Woodcocks migrate at night. They fly at low altitudes, individually or in small, loose flocks. Flight speeds of migrating birds have been clocked at 16 to 28 mi/h (26 to 45 km/h). However, the slowest flight speed ever recorded for a bird, 5 mi/h (8 km/h), was recorded for this species.[14] Woodcocks are thought to orient visually using major physiographic features such as coastlines and broad river valleys.[8] Both the autumn and spring migrations are leisurely compared with the swift, direct migrations of many passerine birds.

In the north, woodcocks begin to shift southward before ice and snow seal off their ground-based food supply. Cold fronts may prompt heavy southerly flights in autumn. Most woodcocks start to migrate in October, with the major push from mid-October to early November.[15] Most individuals arrive on the wintering range by mid-December. The birds head north again in February. Most have returned to the northern breeding range by mid-March to mid-April.[8]

Migrating birds' arrival at and departure from the breeding range is highly irregular. In Ohio, for example, the earliest birds are seen in February, but the bulk of the population does not arrive until March and April. Birds start to leave for winter by September, but some remain until mid-November.[16] Behavior and ecology Food and feeding American woodcock catching a worm in a New York City park

Woodcocks eat mainly invertebrates, particularly earthworms (Oligochaeta). They do most of their feeding in places where the soil is moist. They forage by probing in soft soil in thickets, where they usually remain well-hidden. Other items in their diet include insect larvae, snails, centipedes, millipedes, spiders, snipe flies, beetles, and ants. A small amount of plant food is eaten, mainly seeds.[8] Woodcocks are crepuscular, being most active at dawn and dusk. Breeding

In spring, males occupy individual singing grounds, openings near brushy cover from which they call and perform display flights at dawn and dusk, and if the light levels are high enough, on moonlit nights. The male's ground call is a short, buzzy peent. After sounding a series of ground calls, the male takes off and flies from 50 to 100 yd (46 to 91 m) into the air. He descends, zigzagging and banking while singing a liquid, chirping song.[8] This high spiralling flight produces a melodious twittering sound as air rushes through the male's outer primary wing feathers.[17]

Males may continue with their courtship flights for as many as four months running, sometimes continuing even after females have already hatched their broods and left the nest. Females, known as hens, are attracted to the males' displays. A hen will fly in and land on the ground near a singing male. The male courts the female by walking stiff-legged and with his wings stretched vertically, and by bobbing and bowing. A male may mate with several females. The male woodcock plays no role in selecting a nest site, incubating eggs, or rearing young. In the primary northern breeding range, the woodcock may be the earliest ground-nesting species to breed.[8] Woodcock chick in nest Downy young are already well-camouflaged.

The hen makes a shallow, rudimentary nest on the ground in the leaf and twig litter, in brushy or young-forest cover usually within 150 yd (140 m) of a singing ground.[4] Most hens lay four eggs, sometimes one to three. Incubation takes 20 to 22 days.[3] The down-covered young are precocial and leave the nest within a few hours of hatching.[8] The female broods her young and feeds them. When threatened, the fledglings usually take cover and remain motionless, attempting to escape detection by relying on their cryptic coloration. Some observers suggest that frightened young may cling to the body of their mother, that will then take wing and carry the young to safety.[18] Woodcock fledglings begin probing for worms on their own a few days after hatching. They develop quickly and can make short flights after two weeks, can fly fairly well at three weeks, and are independent after about five weeks.[3]

The maximum lifespan of adult American woodcock in the wild is 8 years.[19] Rocking behavior American woodcocks sometimes rock back and forth as they walk, perhaps to aid their search for worms.

American woodcocks occasionally perform a rocking behavior where they will walk slowly while rhythmically rocking their bodies back and forth. This behavior occurs during foraging, leading ornithologists such as Arthur Cleveland Bent and B. H. Christy to theorize that this is a method of coaxing invertebrates such as earthworms closer to the surface.[20] The foraging theory is the most common explanation of the behavior, and it is often cited in field guides.[21]

An alternative theory for the rocking behavior has been proposed by some biologists, such as Bernd Heinrich. It is thought that this behavior is a display to indicate to potential predators that the bird is aware of them.[22] Heinrich notes that some field observations have shown that woodcocks will occasionally flash their tail feathers while rocking, drawing attention to themselves. This theory is supported by research done by John Alcock who believes this is a type of aposematism.[23] Population status

How many woodcock were present in eastern North America before European settlement is unknown. Colonial agriculture, with its patchwork of family farms and open-range livestock grazing, probably supported healthy woodcock populations.[4]

The woodcock population remained high during the early and mid-20th century, after many family farms were abandoned as people moved to urban areas, and crop fields and pastures grew up in brush. In recent decades, those formerly brushy acres have become middle-aged and older forest, where woodcock rarely venture, or they have been covered with buildings and other human developments. Because its population has been declining, the American woodcock is considered a "species of greatest conservation need" in many states, triggering research and habitat-creation efforts in an attempt to boost woodcock populations.

Population trends have been measured through springtime breeding bird surveys, and in the northern breeding range, springtime singing-ground surveys.[8] Data suggest that the woodcock population has fallen rangewide by an average of 1.1% yearly over the last four decades.[6] Conservation

The American woodcock is not considered globally threatened by the IUCN. It is more tolerant of deforestation than other woodcocks and snipes; as long as some sheltered woodland remains for breeding, it can thrive even in regions that are mainly used for agriculture.[1][24] The estimated population is 5 million, so it is the most common sandpiper in North America.[17]

The American Woodcock Conservation Plan presents regional action plans linked to bird conservation regions, fundamental biological units recognized by the U.S. North American Bird Conservation Initiative. The Wildlife Management Institute oversees regional habitat initiatives intended to boost the American woodcock's population by protecting, renewing, and creating habitat throughout the species' range.[6]

Creating young-forest habitat for American woodcocks helps more than 50 other species of wildlife that need early successional habitat during part or all of their lifecycles. These include relatively common animals such as white-tailed deer, snowshoe hare, moose, bobcat, wild turkey, and ruffed grouse, and animals whose populations have also declined in recent decades, such as the golden-winged warbler, whip-poor-will, willow flycatcher, indigo bunting, and New England cottontail.[25]

Leslie Glasgow,[26] the assistant secretary of the Interior for Fish, Wildlife, Parks, and Marine Resources from 1969 to 1970, wrote a dissertation through Texas A&M University on the woodcock, with research based on his observations through the Louisiana State University (LSU) Agricultural Experiment Station. He was an LSU professor from 1948 to 1980 and an authority on wildlife in the wetlands.[27] References

BirdLife International (2020). "Scolopax minor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22693072A182648054. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22693072A182648054.en. Retrieved November 13, 2021. The American Woodcock Today | Woodcock population and young forest habitat management. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03. Kaufman, Kenn (1996). Lives of North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin, pp. 225–226, ISBN 0618159886. Sheldon, William G. (1971). Book of the American Woodcock. University of Massachusetts. Cooper, T. R. & K. Parker (2009). American woodcock population status, 2009. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, Maryland. Kelley, James; Williamson, Scot & Cooper, Thomas, eds. (2008). American Woodcock Conservation Plan: A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America. Smith, Christopher (2000). Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventures Press, pp. 28–29, ISBN 1885106203. Keppie, D. M. & R. M. Whiting Jr. (1994). American Woodcock (Scolopax minor), The Birds of North America. "American Woodcock Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved September 27, 2020. Jones, Michael P.; Pierce, Kenneth E.; Ward, Daniel (2007). "Avian vision: a review of form and function with special consideration to birds of prey". Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 16 (2): 69. doi:10.1053/j.jepm.2007.03.012. Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 145. Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 351. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4. Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 278. Amazing Bird Records. Trails.com (2010-07-27). Retrieved on 2013-04-03. Sepik, G. F. and E. L. Derleth (1993). Habitat use, home range size, and patterns of moves of the American Woodcock in Maine. in Proc. Eighth Woodcock Symp. (Longcore, J. R. and G. F. Sepik, eds.) Biol. Rep. 16, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. Ohio Ornithological Society (2004). Annotated Ohio state checklist Archived 2004-07-18 at the Wayback Machine. O'Brien, Michael; Crossley, Richard & Karlson, Kevin (2006). The Shorebird Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 444–445, ISBN 0618432949. Mann, Clive F. (1991). "Sunda Frogmouth Batrachostomus cornutus carrying its young" (PDF). Forktail. 6: 77–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 28, 2008. Wasser, D. E.; Sherman, P. W. (2010). "Avian longevities and their interpretation under evolutionary theories of senescence". Journal of Zoology. 280 (2): 103. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00671.x. Bent, A. C. (1927). "Life histories of familiar North American birds: American Woodcock, Scalopax minor". United States National Museum Bulletin. Smithsonian Institution. 142 (1): 61–78. "American Woodcock". Audubon. National Audubon Society. Retrieved October 5, 2023. Heinrich, Bernd (March 1, 2016). "Note on the Woodcock Rocking Display". Northeastern Naturalist. 23 (1): N4–N7. Alcock, John (2013). Animal behavior: an evolutionary approach (10th ed.). Sunderland (Mass.): Sinauer. p. 522. ISBN 0878939660. Henninger, W. F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60. the Woodcock Management Plan. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03. [1]Paul Y. Burns (June 13, 2008). "Leslie L. Glasgow". lsuagcdenter.com. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

Further readingChoiniere, Joe (2006). Seasons of the Woodcock: The secret life of a woodland shorebird. Sanctuary 45(4): 3–5. Sepik, Greg F.; Owen, Roy & Coulter, Malcolm (1981). A Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast, Misc. Report 253, Maine Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Maine.

External linksAmerican woodcock species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology American Woodcock – Scolopax minor – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter American Woodcock Bird Sound Rite of Spring – Illustrated account of the phenomenal courtship flight of the male American woodcock American Woodcock videos[permanent dead link] on the Internet Bird Collection Photo-High Res; Article – www.fws.gov–"Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge", photo gallery and analysis American Woodcock Conservation Plan A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America Timberdoodle.org: the Woodcock Management Plan Sepik, Greg F.; Ray B. Owen Jr.; Malcolm W. Coulter (July 1981). "Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast". Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Miscellaneous Report 253. vte

Sandpipers (family: Scolopacidae) Taxon identifiers Wikidata: Q694319 Wikispecies: Scolopax minor ABA: amewoo ADW: Scolopax_minor ARKive: scolopax-minor Avibase: F4829920F1710E56 BirdLife: 22693072 BOLD: 10164 CoL: 6XXHP BOW: amewoo eBird: amewoo EoL: 45509171 Euring: 5310 FEIS: scmi Fossilworks: 129789 GBIF: 2481695 GNAB: american-woodcock iNaturalist: 3936 IRMNG: 10836458 ITIS: 176580 IUCN: 22693072 NatureServe: 2.105226 NCBI: 56299 ODNR: american-woodcock WoRMS: 159027 Xeno-canto: Scolopax-minor

Categories:IUCN Red List least concern speciesScolopaxNative birds of the Eastern United StatesNative birds of Eastern CanadaBirds of MexicoBirds described in 1789Taxa named by Johann Friedrich Gmelin

The American woodcock (Scolopax minor), sometimes colloquially referred to as the timberdoodle,[2] is a small shorebird species found primarily in the eastern half of North America. Woodcocks spend most of their time on the ground in brushy, young-forest habitats, where the birds' brown, black, and gray plumage provides excellent camouflage.

The American woodcock is the only species of woodcock inhabiting North America.[3] Although classified with the sandpipers and shorebirds in the family Scolopacidae, the American woodcock lives mainly in upland settings. Its many folk names include timberdoodle, bogsucker, night partridge, brush snipe, hokumpoke, and becasse.[4]

The population of the American woodcock has fallen by an average of slightly more than 1% annually since the 1960s. Most authorities attribute this decline to a loss of habitat caused by forest maturation and urban development. Because of the male woodcock's unique, beautiful courtship flights, the bird is welcomed as a harbinger of spring in northern areas. It is also a popular game bird, with about 540,000 killed annually by some 133,000 hunters in the U.S.[5]

In 2008, wildlife biologists and conservationists released an American woodcock conservation plan presenting figures for the acreage of early successional habitat that must be created and maintained in the U.S. and Canada to stabilize the woodcock population at current levels, and to return it to 1970s densities.[6] Description

The American woodcock has a plump body, short legs, a large, rounded head, and a long, straight prehensile bill. Adults are 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) long and weigh 5 to 8 ounces (140 to 230 g).[7] Females are considerably larger than males.[8] The bill is 2.5 to 2.8 inches (6.4 to 7.1 cm) long.[4] Wingspans range from 16.5 to 18.9 inches (42 to 48 cm).[9] Illustration of American woodcock head and wing feathers Woodcock, with attenuate primaries, natural size, 1891

The plumage is a cryptic mix of different shades of browns, grays, and black. The chest and sides vary from yellowish-white to rich tans.[8] The nape of the head is black, with three or four crossbars of deep buff or rufous.[4] The feet and toes, which are small and weak, are brownish gray to reddish brown.[8] Woodcocks have large eyes located high in their heads, and their visual field is probably the largest of any bird, 360° in the horizontal plane and 180° in the vertical plane.[10]

The woodcock uses its long, prehensile bill to probe in the soil for food, mainly invertebrates and especially earthworms. A unique bone-and-muscle arrangement lets the bird open and close the tip of its upper bill, or mandible, while it is sunk in the ground. Both the underside of the upper mandible and the long tongue are rough-surfaced for grasping slippery prey.[4] Taxonomy

The genus Scolopax was introduced in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.[11] The genus name is Latin for a snipe or woodcock.[12] The type species is the Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola).[13] Distribution and habitat

Woodcocks inhabit forested and mixed forest-agricultural-urban areas east of the 98th meridian. Woodcock have been sighted as far north as York Factory, Manitoba, and east to Labrador and Newfoundland. In winter, they migrate as far south as the Gulf Coast of the United States and Mexico.[8]

The primary breeding range extends from Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick) west to southeastern Manitoba, and south to northern Virginia, western North Carolina, Kentucky, northern Tennessee, northern Illinois, Missouri, and eastern Kansas. A limited number breed as far south as Florida and Texas. The species may be expanding its distribution northward and westward.[8]

After migrating south in autumn, most woodcocks spend the winter in the Gulf Coast and southeastern Atlantic Coast states. Some may remain as far north as southern Maryland, eastern Virginia, and southern New Jersey. The core of the wintering range centers on Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.[8] Based on the Christmas Bird Count results, winter concentrations are highest in the northern half of Alabama.

American woodcocks live in wet thickets, moist woods, and brushy swamps.[3] Ideal habitats feature early successional habitat and abandoned farmland mixed with forest. In late summer, some woodcocks roost on the ground at night in large openings among sparse, patchy vegetation.[8]Courtship/breeding habitats include forest openings, roadsides, pastures, and old fields from which males call and launch courtship flights in springtime. Nesting habitats include thickets, shrubland, and young to middle-aged forest interspersed with openings. Feeding habitats have moist soil and feature densely growing young trees such as aspen (Populus spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and mixed hardwoods less than 20 years of age, and shrubs, particularly alder (Alnus spp.). Roosting habitats are semiopen sites with short, sparse plant cover, such as blueberry barrens, pastures, and recently heavily logged forest stands.[8]

Migration

Woodcocks migrate at night. They fly at low altitudes, individually or in small, loose flocks. Flight speeds of migrating birds have been clocked at 16 to 28 mi/h (26 to 45 km/h). However, the slowest flight speed ever recorded for a bird, 5 mi/h (8 km/h), was recorded for this species.[14] Woodcocks are thought to orient visually using major physiographic features such as coastlines and broad river valleys.[8] Both the autumn and spring migrations are leisurely compared with the swift, direct migrations of many passerine birds.

In the north, woodcocks begin to shift southward before ice and snow seal off their ground-based food supply. Cold fronts may prompt heavy southerly flights in autumn. Most woodcocks start to migrate in October, with the major push from mid-October to early November.[15] Most individuals arrive on the wintering range by mid-December. The birds head north again in February. Most have returned to the northern breeding range by mid-March to mid-April.[8]

Migrating birds' arrival at and departure from the breeding range is highly irregular. In Ohio, for example, the earliest birds are seen in February, but the bulk of the population does not arrive until March and April. Birds start to leave for winter by September, but some remain until mid-November.[16] Behavior and ecology Food and feeding American woodcock catching a worm in a New York City park

Woodcocks eat mainly invertebrates, particularly earthworms (Oligochaeta). They do most of their feeding in places where the soil is moist. They forage by probing in soft soil in thickets, where they usually remain well-hidden. Other items in their diet include insect larvae, snails, centipedes, millipedes, spiders, snipe flies, beetles, and ants. A small amount of plant food is eaten, mainly seeds.[8] Woodcocks are crepuscular, being most active at dawn and dusk. Breeding

In spring, males occupy individual singing grounds, openings near brushy cover from which they call and perform display flights at dawn and dusk, and if the light levels are high enough, on moonlit nights. The male's ground call is a short, buzzy peent. After sounding a series of ground calls, the male takes off and flies from 50 to 100 yd (46 to 91 m) into the air. He descends, zigzagging and banking while singing a liquid, chirping song.[8] This high spiralling flight produces a melodious twittering sound as air rushes through the male's outer primary wing feathers.[17]

Males may continue with their courtship flights for as many as four months running, sometimes continuing even after females have already hatched their broods and left the nest. Females, known as hens, are attracted to the males' displays. A hen will fly in and land on the ground near a singing male. The male courts the female by walking stiff-legged and with his wings stretched vertically, and by bobbing and bowing. A male may mate with several females. The male woodcock plays no role in selecting a nest site, incubating eggs, or rearing young. In the primary northern breeding range, the woodcock may be the earliest ground-nesting species to breed.[8] Woodcock chick in nest Downy young are already well-camouflaged.

The hen makes a shallow, rudimentary nest on the ground in the leaf and twig litter, in brushy or young-forest cover usually within 150 yd (140 m) of a singing ground.[4] Most hens lay four eggs, sometimes one to three. Incubation takes 20 to 22 days.[3] The down-covered young are precocial and leave the nest within a few hours of hatching.[8] The female broods her young and feeds them. When threatened, the fledglings usually take cover and remain motionless, attempting to escape detection by relying on their cryptic coloration. Some observers suggest that frightened young may cling to the body of their mother, that will then take wing and carry the young to safety.[18] Woodcock fledglings begin probing for worms on their own a few days after hatching. They develop quickly and can make short flights after two weeks, can fly fairly well at three weeks, and are independent after about five weeks.[3]

The maximum lifespan of adult American woodcock in the wild is 8 years.[19] Rocking behavior American woodcocks sometimes rock back and forth as they walk, perhaps to aid their search for worms.

American woodcocks occasionally perform a rocking behavior where they will walk slowly while rhythmically rocking their bodies back and forth. This behavior occurs during foraging, leading ornithologists such as Arthur Cleveland Bent and B. H. Christy to theorize that this is a method of coaxing invertebrates such as earthworms closer to the surface.[20] The foraging theory is the most common explanation of the behavior, and it is often cited in field guides.[21]

An alternative theory for the rocking behavior has been proposed by some biologists, such as Bernd Heinrich. It is thought that this behavior is a display to indicate to potential predators that the bird is aware of them.[22] Heinrich notes that some field observations have shown that woodcocks will occasionally flash their tail feathers while rocking, drawing attention to themselves. This theory is supported by research done by John Alcock who believes this is a type of aposematism.[23] Population status

How many woodcock were present in eastern North America before European settlement is unknown. Colonial agriculture, with its patchwork of family farms and open-range livestock grazing, probably supported healthy woodcock populations.[4]

The woodcock population remained high during the early and mid-20th century, after many family farms were abandoned as people moved to urban areas, and crop fields and pastures grew up in brush. In recent decades, those formerly brushy acres have become middle-aged and older forest, where woodcock rarely venture, or they have been covered with buildings and other human developments. Because its population has been declining, the American woodcock is considered a "species of greatest conservation need" in many states, triggering research and habitat-creation efforts in an attempt to boost woodcock populations.

Population trends have been measured through springtime breeding bird surveys, and in the northern breeding range, springtime singing-ground surveys.[8] Data suggest that the woodcock population has fallen rangewide by an average of 1.1% yearly over the last four decades.[6] Conservation

The American woodcock is not considered globally threatened by the IUCN. It is more tolerant of deforestation than other woodcocks and snipes; as long as some sheltered woodland remains for breeding, it can thrive even in regions that are mainly used for agriculture.[1][24] The estimated population is 5 million, so it is the most common sandpiper in North America.[17]

The American Woodcock Conservation Plan presents regional action plans linked to bird conservation regions, fundamental biological units recognized by the U.S. North American Bird Conservation Initiative. The Wildlife Management Institute oversees regional habitat initiatives intended to boost the American woodcock's population by protecting, renewing, and creating habitat throughout the species' range.[6]

Creating young-forest habitat for American woodcocks helps more than 50 other species of wildlife that need early successional habitat during part or all of their lifecycles. These include relatively common animals such as white-tailed deer, snowshoe hare, moose, bobcat, wild turkey, and ruffed grouse, and animals whose populations have also declined in recent decades, such as the golden-winged warbler, whip-poor-will, willow flycatcher, indigo bunting, and New England cottontail.[25]

Leslie Glasgow,[26] the assistant secretary of the Interior for Fish, Wildlife, Parks, and Marine Resources from 1969 to 1970, wrote a dissertation through Texas A&M University on the woodcock, with research based on his observations through the Louisiana State University (LSU) Agricultural Experiment Station. He was an LSU professor from 1948 to 1980 and an authority on wildlife in the wetlands.[27] References

BirdLife International (2020). "Scolopax minor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22693072A182648054. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22693072A182648054.en. Retrieved November 13, 2021. The American Woodcock Today | Woodcock population and young forest habitat management. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03. Kaufman, Kenn (1996). Lives of North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin, pp. 225–226, ISBN 0618159886. Sheldon, William G. (1971). Book of the American Woodcock. University of Massachusetts. Cooper, T. R. & K. Parker (2009). American woodcock population status, 2009. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, Maryland. Kelley, James; Williamson, Scot & Cooper, Thomas, eds. (2008). American Woodcock Conservation Plan: A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America. Smith, Christopher (2000). Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventures Press, pp. 28–29, ISBN 1885106203. Keppie, D. M. & R. M. Whiting Jr. (1994). American Woodcock (Scolopax minor), The Birds of North America. "American Woodcock Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved September 27, 2020. Jones, Michael P.; Pierce, Kenneth E.; Ward, Daniel (2007). "Avian vision: a review of form and function with special consideration to birds of prey". Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 16 (2): 69. doi:10.1053/j.jepm.2007.03.012. Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 145. Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 351. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4. Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 278. Amazing Bird Records. Trails.com (2010-07-27). Retrieved on 2013-04-03. Sepik, G. F. and E. L. Derleth (1993). Habitat use, home range size, and patterns of moves of the American Woodcock in Maine. in Proc. Eighth Woodcock Symp. (Longcore, J. R. and G. F. Sepik, eds.) Biol. Rep. 16, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. Ohio Ornithological Society (2004). Annotated Ohio state checklist Archived 2004-07-18 at the Wayback Machine. O'Brien, Michael; Crossley, Richard & Karlson, Kevin (2006). The Shorebird Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 444–445, ISBN 0618432949. Mann, Clive F. (1991). "Sunda Frogmouth Batrachostomus cornutus carrying its young" (PDF). Forktail. 6: 77–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 28, 2008. Wasser, D. E.; Sherman, P. W. (2010). "Avian longevities and their interpretation under evolutionary theories of senescence". Journal of Zoology. 280 (2): 103. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00671.x. Bent, A. C. (1927). "Life histories of familiar North American birds: American Woodcock, Scalopax minor". United States National Museum Bulletin. Smithsonian Institution. 142 (1): 61–78. "American Woodcock". Audubon. National Audubon Society. Retrieved October 5, 2023. Heinrich, Bernd (March 1, 2016). "Note on the Woodcock Rocking Display". Northeastern Naturalist. 23 (1): N4–N7. Alcock, John (2013). Animal behavior: an evolutionary approach (10th ed.). Sunderland (Mass.): Sinauer. p. 522. ISBN 0878939660. Henninger, W. F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60. the Woodcock Management Plan. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03. [1]Paul Y. Burns (June 13, 2008). "Leslie L. Glasgow". lsuagcdenter.com. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

Further readingChoiniere, Joe (2006). Seasons of the Woodcock: The secret life of a woodland shorebird. Sanctuary 45(4): 3–5. Sepik, Greg F.; Owen, Roy & Coulter, Malcolm (1981). A Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast, Misc. Report 253, Maine Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Maine.

External linksAmerican woodcock species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology American Woodcock – Scolopax minor – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter American Woodcock Bird Sound Rite of Spring – Illustrated account of the phenomenal courtship flight of the male American woodcock American Woodcock videos[permanent dead link] on the Internet Bird Collection Photo-High Res; Article – www.fws.gov–"Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge", photo gallery and analysis American Woodcock Conservation Plan A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America Timberdoodle.org: the Woodcock Management Plan Sepik, Greg F.; Ray B. Owen Jr.; Malcolm W. Coulter (July 1981). "Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast". Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Miscellaneous Report 253. vte

Sandpipers (family: Scolopacidae) Taxon identifiers Wikidata: Q694319 Wikispecies: Scolopax minor ABA: amewoo ADW: Scolopax_minor ARKive: scolopax-minor Avibase: F4829920F1710E56 BirdLife: 22693072 BOLD: 10164 CoL: 6XXHP BOW: amewoo eBird: amewoo EoL: 45509171 Euring: 5310 FEIS: scmi Fossilworks: 129789 GBIF: 2481695 GNAB: american-woodcock iNaturalist: 3936 IRMNG: 10836458 ITIS: 176580 IUCN: 22693072 NatureServe: 2.105226 NCBI: 56299 ODNR: american-woodcock WoRMS: 159027 Xeno-canto: Scolopax-minor

Categories:IUCN Red List least concern speciesScolopaxNative birds of the Eastern United StatesNative birds of Eastern CanadaBirds of MexicoBirds described in 1789Taxa named by Johann Friedrich Gmelin

#pro rq 🌈🍓#radqueer#rq#rq community#rq please interact#rq safe#rq 🌈🍓#rqc🌈🍓#transid#pro radqueer#radqueers please interact#radqueer safe

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Grrrr

If i mistake a brooklyn newsie for a manhattan newsie or miss any newsies out , please excuse it because there are just SO god dam many of them 😨😨😭😭😪😪

~~~

Birdsies ( Newsies "Bird + Newsies" )

Jack - Wood Pigeon

Davey - Eurasian Jay

Les - Eurasian Jay

Crutchie - Meadow Lark

Race - Rainbow Lorikeet

Albert - Cardinal

Finch - Finch

Tommy Boy - Pionus Parrot

Buttons - Kea Parrot

Elmer - Purple Martin

JoJo - White Bellbird

Splasher - Green-Cheeked Conures

Romeo - Great Bowerbird

Specs - American Woodcock

Blink - Sharp-shinned Hawk

Mush - SaltMarsh Sparrow

Skittery - Starling

Mike - Peregrine Falcon

Ike - Peregrine Falcon

Julian ( i know he isnt a real character BUT HE IS TO ME 😡 ) - Cape Penduline Tit

Henry - Ruby-Throated Hummingbird

Sniper - American Kestrel

Smalls - Bee Hummingbird

Snitch - Kookaburra

Itey - Goldcrest

Snoddy - Cockatiel

Swifty - Gyrfalcon

Dutchy - Great Spotted Woodpecker

Bumlets - Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker

Boots - Russet Sparrow

Snipeshooter - Little Owl

Guttersnipe - Mottled Wood Owl

Katherine - Kiwi

-

Brooklyn Scewsies ( Brooklyn Newsies "Scale + Newsies" )

Spot - Leopard Gecko

Hotshot - Chahoua Gecko

York - Tokay Gecko

Mack - Leaf-Tailed Gecko

Splint - Rhoptropus Afer

Lucky - Golden Gecko

Scope - Tarentola Chazaliae

Stray - Frilled-Necked Lizard

Ritz - Tree Crocodile

Pips - Crested Gecko

-

Defrogceys ( Delanceys "Frog + Delanceys" )

Oscar - Ranitomeya Frog

Morris - Ranitomeya Frog

( Wiesel - Phantasmal Poison Frog )

-

Others

Miss Medda - Tabby Cat

The Boweries - Siamese Cat

Pulitzer - American Shorthair cross Siamese cross Ragdoll Cat

Nunzio - Fire Salamander

Hannah - Red Ruffed Lemur

Bunsen - Proboscis Monkey

Seitz - Ladoga Ringed Seal

Snyder - Black Mamba

Mr.Jacobi - Shih Tzu

Roosevelt - Newfoundland Dog

Bill - Markhor Goat

Darcy - Buff-Tailed Bumblebee

- mystery anon

oh, this is my absolute favourite, and so detailed!!! so many fantastic choices!!!

mike and ike being told apart by a Very slight difference in their feather pattern. les is literally just like a tinier rounder davey. katherine being a fancy little kiwi!!! (although i do also love the idea of her being something super colourful to reflect her wardrobe)

also JULIAN IS REAL TO US!!! special little guy!!! there’s enough boys here that, truly, what is one more? throw him in there. he deserves it.

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

may i have a birb? 🐤

you got: eurasian woodcock!

"The Eurasian Woodcock utters a strange, weak, high-pitched “pitz” or “tswik” interspersed with low, deep, guttural “aurk-aurk-aurk”. These sounds are given during the display flight called “roding”, and the sequence is constantly repeated." - bird oiseaux

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discovering the Rich Birdlife of Bhutan: Your Guide to Bhutan Birding Tours Packages

Bhutan, often referred to as the "Land of the Thunder Dragon," is a country renowned for its breathtaking landscapes, rich cultural heritage, and commitment to conservation. Nestled in the eastern Himalayas, Bhutan is home to diverse ecosystems that host an impressive array of bird species, making it a premier destination for birding enthusiasts from the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, France, and beyond. With its stunning landscapes ranging from lush valleys to soaring mountains, Bhutan offers an unparalleled experience for those looking to explore its avian wonders through expertly curated Bhutan birding tours packages from Orrog, your trusted Bhutan travel agency.

Birding Tours in Bhutan, Bhutan Birding Tour Packages, best birding tours in Bhutan, birdwatching trips in Bhutan, bird watching excursions in Bhutan

The Avian Wonders of Bhutan

Bhutan's unique geographical position and varying altitudes create a rich diversity of habitats, from subtropical forests to alpine meadows, making it a haven for birdwatchers. The country is home to over 700 species of birds, many of which are endemic or endangered, including the elusive Black-necked Crane, which migrates to Bhutan during the winter months. Birding tours in Bhutan allow visitors to observe these magnificent creatures in their natural habitats while enjoying the breathtaking scenery that the country has to offer.

Orrog's Bhutan birding birdwatching trips excursions are designed to provide an immersive experience, focusing on key birding sites that promise a rewarding journey. Whether you are an experienced birder or a casual nature enthusiast, Bhutan's birding tours are tailored to suit all levels of expertise, ensuring that every traveler leaves with cherished memories and a deeper appreciation for Bhutan's avian life.

Popular Birding Locations in Bhutan

Phobjikha Valley: This glacial valley is famous for its wintering population of Black-necked Cranes. Visitors can enjoy watching these elegant birds as they dance and feed in the fields. The valley also hosts a variety of other species, including the Himalayan Monal and various pheasants, making it a must-visit location for birdwatchers.

Jigme Dorji National Park: Spanning over 4,300 square kilometers, this national park is a birdwatcher’s paradise. The diverse ecosystems range from subtropical forests to alpine tundra, providing habitats for species such as the Bhutanese Blue Robin and the Slender-billed Scimitar Babbler. The park is also known for its stunning landscapes and opportunities for trekking tours in Bhutan.

Bumthang Valley: Known for its rich biodiversity, Bumthang is another excellent destination for birding. The region's mixed forests and open grasslands attract various bird species, including the beautiful Golden-throated Barbet and the remarkable Fire-tailed Myzornis.

Trongsa and Wangdue Phodrang: These areas are known for their unique bird species, including the Rufous-necked Hornbill and the Eurasian Woodcock. The forests surrounding these regions are home to a myriad of bird species that are waiting to be discovered.

Why Choose Orrog for Bhutan Birding Tours Packages?

Orrog is dedicated to providing unique and enriching travel experiences, ensuring that every aspect of your birding journey is taken care of. Our Bhutan birding tours packages are meticulously planned to include:

Expert Guides: Our birding tours are led by experienced local guides who have an intimate knowledge of Bhutan's birdlife and ecosystems. They are well-versed in the behaviors and habitats of various species, ensuring that you have the best chance of spotting your target birds.

Customized Itineraries: We understand that each traveler has unique interests and needs. Orrog offers customizable itineraries that allow you to focus on specific areas or types of birds, whether you are interested in endemic species or simply want to enjoy the natural beauty of Bhutan.

Cultural Integration: While birding is a primary focus, Orrog's packages also incorporate Bhutan's rich cultural heritage. Our tours include visits to historical sites, traditional festivals, and opportunities to engage with local communities. This integration allows travelers to appreciate Bhutan's diverse cultural activities alongside its natural wonders.

Sustainable Practices: Orrog is committed to sustainable tourism practices that respect the environment and support local communities. By choosing our birding tours in Bhutan, you are contributing to the conservation of Bhutan’s unique ecosystems and the livelihoods of its people.

Beyond Birding: Bhutan’s Cultural Experiences

Traveling in Bhutan is not just about observing its avian life; it’s also about immersing yourself in a culture that values happiness and spirituality. Bhutan cultural tours and cultural trips are integral to your journey, allowing you to explore the country's rich religious heritage and traditions.

Visitors can explore ancient monasteries, attend local festivals, and experience the warmth of Bhutanese hospitality. Whether participating in a Bhutan festival celebration, exploring the architectural beauty of dzongs, or enjoying the local cuisine, travelers will find that Bhutan offers a holistic travel experience that nourishes both the body and the soul.

Adventure Beyond Birding: Trekking and Hiking

For those looking to combine birding with adventure, Bhutan’s extensive trekking routes provide a perfect backdrop. Trekking tours in Bhutan take you through breathtaking landscapes, from lush valleys to high mountain passes, where birding opportunities abound.

Orrog offers Bhutan hiking and trekking experiences packages that allow you to explore remote areas while enjoying the sights and sounds of Bhutan’s rich wildlife. These treks not only provide stunning views but also bring you closer to the country’s unique flora and fauna, enhancing your birdwatching experience.

Planning Your Birding Adventure with Orrog

To begin your birding adventure in Bhutan, consider the following tips for planning your trip:

Choose the Right Season: The best time for birdwatching in Bhutan is during the spring (March to May) and autumn (September to November) when migratory birds are present, and the weather is pleasant. Winter can be rewarding, particularly for those interested in the Black-necked Crane.

Select Your Package: Orrog’s Bhutan birding tours packages can be tailored to your interests and budget. Whether you prefer a short trip focusing on specific areas or an extensive tour covering multiple regions, we have the right package for you.

Prepare for the Altitude: Bhutan’s elevation can be significant, so it's important to acclimatize properly. Our guides will ensure that you have adequate time to adjust and enjoy your birding excursions.

Pack Accordingly: Bring along the necessary equipment, such as binoculars, a camera with a good zoom lens, and appropriate clothing for varying weather conditions. Comfortable walking shoes are also essential for trekking and exploring various birding sites.

Be Respectful of Nature: As you explore Bhutan’s incredible biodiversity, remember to practice responsible birdwatching. Maintain a safe distance from nesting sites, minimize noise, and leave no trace behind.

See more:-

bhutan tour packages, bhutan travel packages, bhutan holiday packages

Birding Tours in Bhutan, Bhutan Birding Tour Packages, best birding tours in Bhutan, birdwatching trips in Bhutan, bird watching excursions in Bhutan

Cultural Tours in Bhutan, culture trips in Bhutan, cultural activities in Bhutan, Cultural Sightseeing Adventures in Bhutan, Religious Heritage Tours in Bhutan

0 notes

Text

#aFactADay2024

#1317: the American and Eurasian Woodcocks bounce along as they walk sometimes. they rock up and down and a bit forward and backward as if they're vibing to music while they walk. nobody really knows why they do this though! it's been popularised that this is to get prey, because stamping rhythmically on the ground attracts worms and bugs, but there's very little evidence for that (they clearly just read Dune). they do the rocking thing when humans get close, on piles of leaves, even on snow, so it wouldn't be to get the worms. it's alternatively suggested that they rock to conspicuously show off their brightly coloured underfeathers (usually they're very drab), to display to predators that they're not worth hunting, like the white tail on a deer. maybe they're telling a potential predator that it's ready to fly off at any moment, without the actual effort of having to fly off.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Some original sketches done on the front pages of my little book 'Floodmeadow Sketchbook 01' a month ago.

Thank you to everyone who ordered a copy <3

#animal art#artists on tumblr#sketches#art#drawing#pencil#sketch#traditional art#tawny owl#woodcock#eurasian woodcock#bird art#bird#wildlife art

502 notes

·

View notes

Text

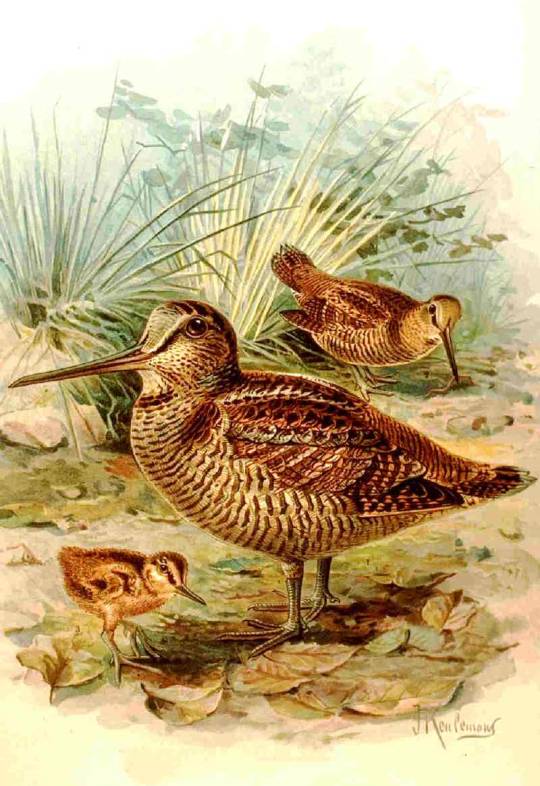

Painting of a Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola) family, by artist Johann Friedrich Neumann from the book 'Natural history of the birds of central Europe'

#posting this bc i just made a it my icon#birds#art#eurasian woodcock#other people's art#also its in the public domain so i have every legal right ro share this image wherever and whenever i please#and i think it should be seen by everyone. just everyone in the world needs to see this#just look at that woodcock. the way its looking at the viewer with that gentle kind expression

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

won camp nanowrimo for the first time ever. spent some time laying on my bed and watching videos of eurasian woodcocks walking. life is beautiful

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel they need a name relating to their little shuffle dance.

But also woodcocks (both American and European) have eyes so far back in their heads they are the only bird with a 360° field of vision, making them appear to be some sort of Terrestrial Octopus.

Also of note, woodcocks (Eurasian ones, at least), have white feathers that are 30% whiter and more reflective than any other bird. They use them for communication even at night.

There are about 7 or 8 species of Woodcock, but only the Eurasian and American are widespread. They're also closely related to the snipes, if you're one of the Americans like me who were ever taking snipe hunting. They're excellent birds.

863 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Whitest Feathers of Any Bird Have Been Found, And They're Dazzling : ScienceAlert

New Post has been published on https://petn.ws/EtXm7

The Whitest Feathers of Any Bird Have Been Found, And They're Dazzling : ScienceAlert

The bright, white tail feathers of the otherwise inconspicuous Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola) are the most reflective on record. An international team of researchers found that the woodcock’s white patches reflected up to 55 percent of light, making their feathers around 30 percent more reflective than any other bird previously measured. Woodcocks are mottled brown […]

See full article at https://petn.ws/EtXm7 #BirdNews

0 notes