#essanay comedy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"By the Sea" 1915

By the Sea (1915) Charlie Chaplin

271 notes

·

View notes

Text

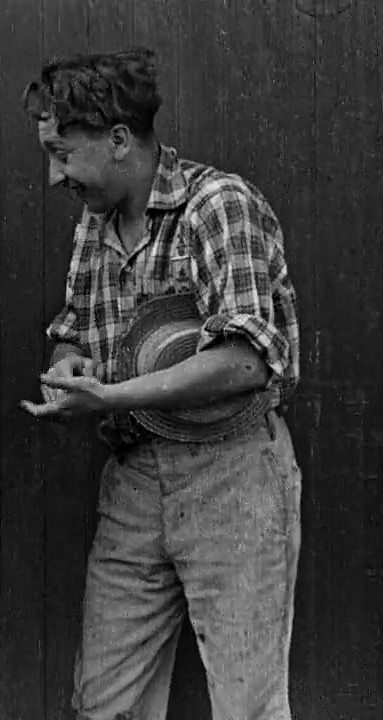

Of Paresis and Paddy McGuire

Irish-American comedian Paddy McGuire (born ca. 1884) died this day in 1923 — a century ago today. McGuire’s career was short but prolific: nearly 80 films in a little over five years. But it’s likely that the cause of his death (syphilis, a common one in that day) had interfered much earlier. The front half of his career (1915-17) showed lots of promise. By the last couple of years he was down…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

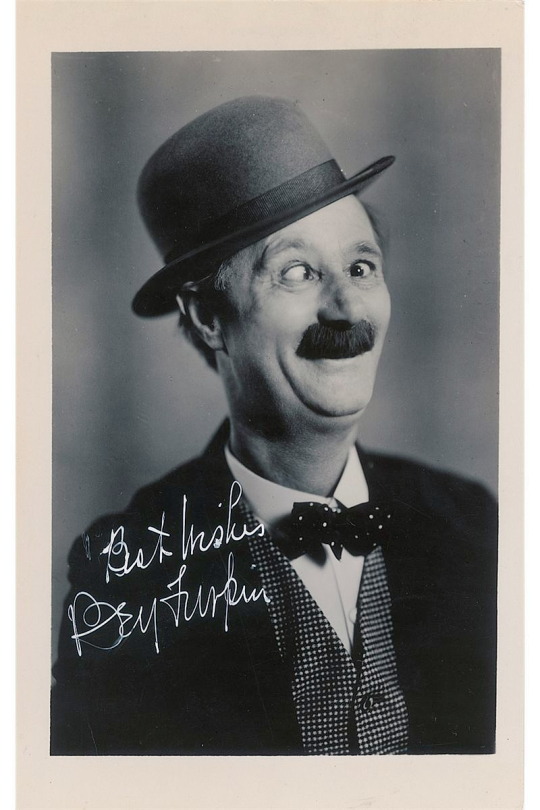

Bernard "Ben" Turpin (September 19, 1869 – July 1, 1940) was an American comedian and actor, best remembered for his work in silent films. His trademarks were his cross-eyed appearance and adeptness at vigorous physical comedy. A sometimes vaudeville performer, he was "discovered" for film while working as the janitor for Essanay Studios in Chicago.

(Wiki)

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

In The Park (1915) Charlie Chaplin

In the Park is a comedy film directed, written and starring Charlie Chaplin . Chaplin's third film produced by Essanay , In the Park picks up on the intrigues already underlying Chaplin's earlier films at Keystone: the Tramp wanders through a park among beautiful girls, jealous boyfriends and patrolling policemen, just as he did in Twenty Minutes of Love . It was his penultimate one-reel film before By the Sea , thereafter Chaplin would turn to more complex plots with more elaborate characters, where every gag was studied in detail and less and less room was allocated to improvisation.

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

When you got style and you can’t help but show it off.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Floorwalker" was the first of twelve films Charlie Chaplin made for Mutual Studios between 1916 and 1917.

While the Essanay films were a key milestone in his development as an artist, most critics credit Chaplin's move to the Mutual Film Corporation as the beginning of the classic era. With creative control as writer, producer, director, and star, Chaplin was able to begin to realize his full potential, and the twelve two-part shorts he made at Mutual remain among the most famous films ever made. The films he made at Mutual show Charlie Chaplin's genius for combining comedy with pathos. It's hard to believe that these films are almost 100 years old, but the quality and comedy genius of Charlie Chaplin are truly timeless!

In the movie "The Floorwalker" Charlie used two new gags: the escalator and the mirror effect, which have become a permanent part of cinema history.

Charlie Chaplin played these roles with Eric Campbell and Lloyd Bacon.

#charlie chaplin#eric cambell#the floorwalker#1916#lloyd bacon#mutual film company’s lone star studio#silent film#classic film#classic hollywood

0 notes

Text

"Shanghaied" 1915

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

E. Mason Hopper: From Snakeville to Sunset Blvd.

E. Mason Hopper: From Snakeville to Sunset Blvd.

Vermont native E. Mason Hopper (1885-1967) performed in vaudeville and with stock companies, played pro baseball, and studied at the University of Maryland before becoming a successful film director.

Hopper began directing silent comedy shorts for Essanay in 1911, including several Alkali Ike/ Snakeville comedies. Just as Essanay was collapsing in 1916, he went into directing features, some of…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gloria Josephine May Swanson (March 27, 1899 – April 4, 1983) was an American actress, producer, and businesswoman. She first achieved fame acting in dozens of silent films in the 1920s and was nominated three times for the Academy Award for Best Actress, most famously for her 1950 return in Billy Wilder's Sunset Boulevard, which also earned her a Golden Globe Award.

Swanson was born in Chicago and raised in a military family that moved from base to base. Her schoolgirl crush on Essanay Studios actor Francis X. Bushman led to her aunt taking her to tour the actor's Chicago studio. The 15-year-old Swanson was offered a brief walk-on for one film as an extra, beginning her life's career in front of the cameras. Swanson was soon hired to work in California for Mack Sennett's Keystone Studios comedy shorts opposite Bobby Vernon. She was eventually recruited by Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount Pictures, where she was put under contract for seven years.

In 1925, Swanson joined United Artists as one of the film industry's pioneering women filmmakers. She produced and starred in the 1928 film Sadie Thompson, earning her a nomination for Best Actress at the first annual Academy Awards. Her sound film debut performance in the 1929 The Trespasser, earned her a second Academy Award nomination. After almost two decades in front of the cameras, her film success waned during the 1930s. Swanson received renewed praise for her comeback role in Sunset Boulevard (1950). She only made three more films, but guest starred on several television shows, and acted in road productions of stage plays.

#gloria swanson#silent era#silent hollywood#silent movie stars#classic hollywood#golden age of hollywood#old hollywood#1910s movies#1920s hollywood#1930s hollywood#1940s hollywood#1950s hollywood#hollywood legend

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Colleen Moore (born Kathleen Morrison; August 19, 1899 – January 25, 1988) was an American film actress who began her career during the silent film era. Moore became one of the most fashionable (and highly-paid) stars of the era and helped popularize the bobbed haircut.

A huge star in her day, approximately half of Moore's films are now considered lost, including her first talking picture from 1929. What was perhaps her most celebrated film, Flaming Youth (1923), is now mostly lost as well, with only one reel surviving.

Moore took a brief hiatus from acting between 1929 and 1933, just as sound was being added to motion pictures. After the hiatus, her four sound pictures released in 1933 and 1934 were not financial successes. Moore then retired permanently from screen acting.

After her film career, Moore maintained her wealth through astute investments, becoming a partner of Merrill Lynch. She later wrote a "how-to" book about investing in the stock market.

Moore also nurtured a passion for dollhouses throughout her life and helped design and curate The Colleen Moore Dollhouse, which has been a featured exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, Illinois since the early 1950s. The dollhouse, measuring 9 square feet (0.84 m2), was estimated in 1985 to be worth of $7 million, and it is seen by 1.5 million people annually.

Moore was born Kathleen Morrison on August 19, 1899, (according to the bulk of the official records;[4] the date which she insisted was correct in her autobiography, Silent Star, was 1902)[5] in Port Huron, Michigan,[6] Moore was the eldest child of Charles R. and Agnes Kelly Morrison. The family remained in Port Huron during the early years of Moore's life, at first living with her grandmother Mary Kelly (often spelled Kelley) and then with at least one of Moore's aunts.

By 1905, the family moved to Hillsdale, Michigan, where they remained for over two years. They relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, by 1908. They are listed at three different addresses during their stay in Atlanta (From the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library city directories): 301 Capitol Avenue −1908; 41 Linden Avenue – 1909; 240 N. Jackson Street – 1910. They then lived briefly — probably less than a year — in Warren, Pennsylvania, and by 1911, they had settled in Tampa, Florida.

At age 15 she was taking her first step in Hollywood. Her uncle arranged a screen test with director D.W. Griffith. She wanted to be a second Lillian Gish but instead, she found herself playing heroines in Westerns with stars such as Tom Mix.

Two of Moore's great passions were dolls and movies; each would play a great role in her later life. She and her brother began their own stock company, reputedly performing on a stage created from a piano packing crate. Her aunts, who doted on her, indulged her other great passion and often bought her miniature furniture on their many trips, with which she furnished the first of a succession of dollhouses. Moore's family summered in Chicago, where Moore enjoyed baseball and the company of her Aunt Lib (Elizabeth, who changed her name to "Liberty", Lib for short) and Lib's husband Walter Howey. Howey was the managing editor of the Chicago Examiner and an important newspaper editor in the publishing empire of William Randolph Hearst, and was the inspiration for Walter Burns, the fictional Chicago newspaper editor in the play and the film, The Front Page.

Early years

Essanay Studios was within walking distance of the Northwestern L, which ran right past the Howey residence. (They occupied at least two residences between 1910 and 1916: 4161 Sheridan and 4942 Sheridan.) In interviews later in her silent film career, Moore claimed she had appeared in the background of several Essanay films, usually as a face in a crowd. One story has it she had gotten into the Essanay studios and waited in line to be an extra with Helen Ferguson: in an interview with Kevin Brownlow many years later, Ferguson told a story that substantially confirmed many details of the claim, though it is not certain if she was referring to Moore's stints as a background extra (if she really was one) or to her film test there prior to her departure for Hollywood in November 1917. Film producer D.W. Griffith was in debt to Howey, who had helped him to get both The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance through the Chicago censorship board.

"I was being sent to Hollywood - not because anybody out there thought I was any good, but simply to pay off a favor".

The contract to Griffith's Triangle-Fine Arts was conditional on passing a film test to ensure that her heterochromia (she had one brown eye, one blue eye) would not be a distraction in close-up shots. Her eyes passed the test, so she left for Hollywood with her grandmother and her mother as chaperones. Moore made her first credited film appearance in 1917 in The Bad Boy for Triangle Fine Arts, and for the next few years appeared in small, supporting roles gradually attracting the attention of the public.

The Bad Boy was released on February 18, and featured Robert Harron, Richard Cummings, Josephine Crowell, and Mildred Harris (who would later become Charles Chaplin's first wife). Two months later, it was followed by An Old-Fashioned Young Man, again with Robert Harron. Moore’s third film was Hands Up! filmed in part in the vicinity of the Seven Oaks (a popular location for productions that required dramatic vistas). This was her first true western. The film’s scenario was written by Wilfred Lucas from a story by Al Jennings, the famous outlaw who had been freed from jail by presidential pardon by Theodore Roosevelt in 1907. Monte Blue was in the cast and noticed Moore could not mount her horse, though horseback riding was required for the part (during casting for the part she neglected to mention she did not know how to ride). Blue gave her a quick lesson essentially consisting of how to mount the horse and how to hold on.

On May 3, 1917, the Chicago Daily Tribune said: "Colleen Moore contributes some remarkable bits of acting. She is very sweet as she goes trustingly to her bandit hero, and, O, so pitiful, when finally realizing the character of the man, she goes into a hysteria of terror, and, shrieking 'Daddy, Daddy, Daddy!' beats futilely on a bolted door, a panic-stricken little human animal, who had not known before that there was aught but kindness in the world." About the time her first six-month contract was extended an additional six months, she requested and received a five weeks release to do a film for Universal's Bluebird division, released under the name The Savage. This was her fourth film, and she was only needed for two weeks. Upon her return to the Fine Arts lot, she spent several weeks trying to get her to pay for the three weeks she had been available for work for Triangle (finally getting her pay in December of that year).

Soon after, the Triangle Company went bust, and while her contract was honored, she found herself scrambling to find her next job. With a reel of her performance in Hands Up! under her arm, Colin Campbell arranged for her to get a contract with Selig Polyscope. She was very likely at work on A Hoosier Romance before The Savage was released in November. After A Hoosier Romance, she went to work on Little Orphant Annie. Both films were based upon poems by James Whitcomb Riley, and both proved to be very popular. It was her first real taste of popularity.

Little Orphant Annie was released in December. The Chicago Daily Tribune wrote of Moore, "She was a lovely and unspoiled child the last time I saw her. Let’s hope commendation hasn’t turned her head." Despite her good notices, her luck took a turn for the worse when Selig Polyscope went bust. Once again Moore found herself unemployed, but she had begun to make a name for herself by 1919. She had a series of films lined up. She went to Flagstaff, Arizona for location work on The Wilderness Trail, another western, this time with Tom Mix. Her mother went along as a chaperone. Moore wrote that while she had a crush on Mix, he only had eyes for her mother. The Wilderness Trail was a Fox Film Corporation production, and while it had started production earlier, it would not be released until after The Busher, which was released on May 18. The Busher was an H. Ince Productions-Famous Players-Lasky production; it was a baseball film wherein the hero was played by John Gilbert. The Wilderness Trail followed on July 6, another Fox film. A few weeks later, The Man in the Moonlight, a Universal Film Manufacturing Company film was released on July 28. The Egg Crate Wallop was a Famous Players-Lasky production released by Paramount Pictures on September 28.

The next stage of her career was with the Christie Film Company, a move she made when she decided she needed comic training. While with Christie, she made Her Bridal Nightmare, A Roman Scandal, and So Long Letty. At the same time as she was working on these films, she worked on The Devil's Claim with Sessue Hayakawa, in which she played a Persian woman, When Dawn Came, and His Nibs (1921) with Chic Sale. All the while, Marshall Neilan had been attempting to get Moore released from her contract so she could work for him. He was successful and made Dinty with Moore, releasing near the end of 1920, followed by When Dawn Came.

For all his efforts to win Moore away from Christie, it seems Neilan loaned Moore to other studios most of the time. He loaned her out to King Vidor for The Sky Pilot, released in May 1921, yet another Western. After working on The Sky Pilot on location in the snows of Truckee, she was off to Catalina Island for work on The Lotus Eater with John Barrymore. In October 1921, His Nibs was released, her only film to be released that year besides The Sky Pilot. In His Nibs, Moore actually appeared in a film within the film; the framing film was a comedy vehicle for Chic Sales. The film it framed was a spoof on films of the time. 1922 proved to be an eventful year for Moore as she was named a WAMPAS Baby Star during a "frolic" at the Ambassador Hotel which became an annual event, in recognition of her growing popularity.[13] In early 1922, Come On Over was released, made from a Rupert Hughes story and directed by Alfred E. Green. Hughes directed Moore himself in The Wallflower, released that same year. In addition, Neilan introduced her to John McCormick, a publicist who had had his eye on Moore ever since he had first seen her photograph. He had prodded Marshall into an introduction. The two hit it off, and before long they were engaged. By the end of that year, three more of her films were released: Forsaking All Others, The Ninety and Nine, and Broken Chains.

Look Your Best and The Nth Commandment were released in early 1923, followed by two Cosmopolitan Productions, The Nth Commandment and Through the Dark. By this time, Moore had publicly confirmed her engagement to McCormick, a fact that she had been coy about to the press previously. Before mid-year, she had signed a contract with First National Pictures, and her first two films were slated to be The Huntress and Flaming Youth. Slippy McGee came out in June, followed by Broken Hearts of Broadway.

Moore and John McCormick married while Flaming Youth was still in production, and just before the release of The Savage. When it was finally released in 1923, Flaming Youth, in which she starred opposite actor Milton Sills, was a hit. The controversial story put Moore in focus as a flapper, but after Clara Bow took the stage in Black Oxen in December, she gradually lost her momentum. In spring 1924 she made a good but unsuccessful effort to top Bow in The Perfect Flapper, and soon after she dismissed the whole flapper vogue; "No more flappers...people are tired of soda-pop love affairs." Decades later Moore stated Bow was her "chief rival."

Through the Dark, originally shot under the name Daughter of Mother McGinn, was released during the height of the Flaming Youth furor in January 1924. Three weeks later, Painted People was released. After that, she was to star in Counterfeit. The film went through a number of title changes before being released as Flirting with Love in August. In October, First National purchased the rights to Sally for Moore's next film. It would be a challenge, as Sally was a musical comedy. In December, First National purchased the rights to Desert Flower and in so doing had mapped out Moore's schedule for 1925: Sally would be filmed first, followed by The Desert Flower.

By the late 1920s, she had accomplished dramatic roles in films such as So Big, where Moore aged through a stretch of decades, and was also well received in light comedies such as Irene. An overseas tour was planned to coincide with the release of So Big in Europe, and Moore saw the tour as her first real opportunity to spend time with her husband, John McCormick. Both she and John McCormick were dedicated to their careers, and their hectic schedules had kept them from spending any quality time together. Moore wanted a family; it was one of her goals.

Plans for the trip were put in jeopardy when she injured her neck during the filming of The Desert Flower. Her injury forced the production to shut down while Moore spent six weeks in a body cast in bed. Once out of the cast, she completed the film and left for Europe on a triumphal tour. When she returned, she negotiated a new contract with First National. Her films had been great hits, so her terms were very generous. Her first film upon her return to the States was We Moderns, set in England with location work done in London during the tour. It was a comedy, essentially a retelling of Flaming Youth from an English perspective. This was followed by Irene (another musical in the style of the very popular Sally) and Ella Cinders, a straight comedy that featured a cameo appearance by comedian Harry Langdon. It Must Be Love was a romantic comedy with dramatic undertones, and it was followed by Twinkletoes, a dramatic film that featured Moore as a young dancer in London's Limehouse district during the previous century. Orchids and Ermine was released in 1927, filmed in part in New York, a thinly veiled Cinderella story.

In 1927, Moore split from her studio after her husband suddenly quit. It is rumored that John McCormick was about to be fired for his drinking and that she left as a means of leveraging her husband back into a position at First National. It worked, and McCormick found himself as Moore's sole producer. Moore's popularity allowed her productions to become very large and lavish. Lilac Time was one of the bigger productions of the era, a World War I drama. A million dollar film, it made back every penny spent within months. Prior to its release, Warner Bros. had taken control of First National and were less than interested in maintaining the terms of her contract until the numbers started to roll in for Lilac Time. The film was such a hit that Moore managed to retain generous terms in her next contract and her husband as her producer.

In 1928, inspired by her father and with help from her former set designer, a dollhouse was constructed by her father, which was 9 square feet with the tallest tower 12 feet high. The interior of The Colleen Moore Dollhouse, designed by Harold Grieve, features miniature bear skin rugs and detailed furniture and art. Moore's dollhouse has been a featured exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, Illinois since October 30, 1949, where according to the museum, it is seen by 1.5 million people each year and would be worth $7 million. Moore continued working on it and contributing artifacts to it until her death.

This dollhouse was the eighth one Moore owned. The first dollhouse, she wrote in her autobiography Silent Star (1968), evolved from a cabinet that held her collection of miniature furniture. It was supposedly built from a cigar box. Kitty Lorgnette wrote in the Saturday, August 13, 1938 edition of The Evening News (Tampa) that the first dollhouse was purchased by Oraleze O'Brien (Mrs. Frank J. Knight) in 1916 when Moore (then Kathleen) left Tampa. Oraleze was too big for dollhouses, however, and she sold it again after her cat had kittens in it, and from there she lost track of it. The third house was possibly given to the daughter of Moore's good friend, author Adela Rogers St. Johns. The fourth survives and remains on display in the living room of a relative.

With the advent of talking pictures in 1929, Moore took a hiatus from acting. After divorcing McCormick in 1930, Moore married prominent New York-based stockbroker Albert Parker Scott in 1932. The couple lived at that time in a lavish home at 345 St. Pierre Road in Bel Air, where they hosted parties for and were supporters of the U.S. Olympic team, especially the yachting team, during the 1932 Summer Olympics held in Los Angeles.

In 1934, Moore, by then divorced from Albert Parker Scott, returned to work in Hollywood. She appeared in three films, none of which was successful, and Moore retired. Her last film was a version of The Scarlet Letter in 1934. She later married the widower Homer Hargrave and raised his children (she never had children of her own) from a previous marriage, with whom she maintained a lifelong close relationship. Throughout her life she also maintained close friendships with other colleagues from the silent film era, such as King Vidor and Mary Pickford.

In the 1960s, Moore formed a television production company with King Vidor with whom she had worked in the 1920s. She also published two books in the late 1960s, her autobiography Silent Star: Colleen Moore Talks About Her Hollywood (1968) and How Women Can Make Money in the Stock Market (1969). She also figures prominently alongside King Vidor in Sidney D. Kirkpatrick's book, A Cast of Killers, which recounts Vidor's attempt to make a film of and solve the murder of William Desmond Taylor. In that book, she is recalled as having been a successful real estate broker in Chicago and partner in the investment firm Merrill Lynch after her film career.

Many of Moore's films deteriorated, but not due to her own neglect, after she had sent them to be preserved at the Museum of Modern Art. Some time later, Warner Brothers asked for their nitrate materials to be returned to them. Moore's earlier First National films were also sent, since Warners later acquired First National. Upon their arrival, the custodian at MOMA, not seeing the films on the manifest, put them to one side and never went back to them. Many years later, Moore inquired about her collection and MOMA found the films languishing unprotected. When the films were examined, they had decomposed past the point of preservation. Heartbroken, she tried in vain to retrieve any prints she could from several sources without much success. In 1956, the material from WB and FN was sold to Associated Artists Productions, later to MGM/UA and then, Turner Entertainment.

At the height of her fame, Moore was earning $12,500 per week. She was an astute investor, and through her investments, remained wealthy for the rest of her life. In her later years she would frequently attend film festivals, and was a popular interview subject always willing to discuss her Hollywood career. She was a participant in the documentary series Hollywood (1980), providing her recollections of Hollywood's silent film era.

Moore was married four times. Her first marriage was to John McCormick of First National Studios. They married in 1923 and divorced in 1930. In 1932, Moore married stockbroker Albert P. Scott. This union ended in divorce in 1934. Moore's third marriage was to Homer Hargrave, whom she married in 1936; he provided funding for her dollhouse and she adopted his son, Homer Hargrave, Jr and his daughter, Judy Hargrave. They remained married until Hargrave's death in 1965. In 1982, Moore married her final husband, builder Paul Magenot. They were married until Moore's death in 1988.

On January 25, 1988, Moore died from cancer in Paso Robles, California, aged 88. For her contribution to the motion picture industry, Colleen Moore has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1551 Vine Street.

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote of her: "I was the spark that lit up Flaming Youth, Colleen Moore was the torch. What little things we are to have caused all that trouble."

#colleen moore#silent era#silent hollywood#silent movie stars#1910s movies#1920s hollywood#golden age of hollywood#classic movie stars#classic hollywood#1930s hollywood#flapper#roaring 20s

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charlie Chaplin’s Chubs Series

Bud Jamison

Big 19yo Bud joined Essanay Films shortly after Chaplin did in 1915 appearing in 11 comedies with Charlie while he was there. Chaplin fine-tuned his little tramp character using less makeup so his expressions could be seen and making him a more sympathetic character while being such a stinker. He also gained more and more creative control as his films were always a hit. He would, write direct, act and cast his films. He was able to form a troupe of comedy players which he used in his movies while there and that included Jamison. Bud Jamison later went on to Three Stooges comedy shorts, often unfairly not credited.

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

“When a movie character is really working, we become that character. That’s what the movies offer: Escapism into lives other than our own.” ~ Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times film critic from 1967-2013

Although Chicago’s 1863 World’s Columbian Exposition was home to the world’s first movie screening, the storied history of the Chicago film industry officially dates back to the early 1900s. At that time, Chicago was a world leader in the rental of moving picture films and general patronage of motion pictures. By 1907 more than 15 film exchanges were in operation in Chicago, controlling 80% of the film distribution market for the entire country. Even after Chicago studios departed for Hollywood, Chicago remained an important distribution market. The 800 to 1500 blocks of South Wabash in the Loop housed high-profile distribution offices for MGM, Columbia, Warner Brothers, Republic, Universal, RKO, and Paramount.

During the early 1900s, Chicago also had more film theaters per capita than any other city in the U.S., with five-cent theaters or nickelodeons playing a significant role in commercial development throughout its neighborhoods. The Balaban and Katz chain was the largest theater chain in the studio era (1919-1952), with 50 theaters in Chicago alone. They were known for building beautiful movie palaces to show movies and present popular stage shows. Among these are the still thriving Chicago Theatre (formerly Balaban and Katz Chicago Theatre) which opened in 1921 and the James M. Nederlander Theatre built-in 1926 (formerly Oriental).

Early Chicago Movie Studios

Based in Uptown, Essanay Studios (originally The Peerless Film Manufacturing Company) was founded in 1907 by George Spoor and Gilbert Anderson. The studio released more than 2,000 shorts and feature films in their 10 years in Chicago, most notably 15 comedy shorts starring Charlie Chaplin. The studio produced silent films by other great stars such as Gloria Swanson, Wallace Beery, and Gilbert “Broncho Billy” Anderson, who won honorary Academy Awards for his time at the studio. While Essanay packed up and moved to Hollywood in 1917, the building at 1345 Argyle Street was designated a landmark in 1996. The original Essanay lettering and terra cotta Indian head Essanay trademarks still greet visitors.

In 1907, William Selig, a former magician and theatrical troupe manager founded the Selig Polyscope Company at 3900 N. Claremont. Bordered by Irving Park Road and Western Avenue, the studio covered three acres, employed more than 200 people, and specialized in animal productions. When Thomas Edison’s motion picture patents became a barrier, Selig “borrowed” technology from the competing Lumiere Brothers. In 1909 when legal issues caught up with him, Selig moved to Los Angeles, where he created the first Hollywood movie studio. Selig stopped film production in 1918, transitioning from an animal and prop supplier to other studios and a zoo and amusement park operator.

The Windy City is Home to Many Film Productions

The Chicago Film Office, a division of the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, has been instrumental in attracting the production of feature films, television series, commercials, and documentaries. Since 1980, more than 1,100 feature films and television productions have been shot in Chicago, including the popular and award-winning films Ordinary People, Risky Business, Sixteen Candles, The Color of Money, The Untouchables, Home Alone, A League of Their Own, Groundhog Day, Chicago, and The Dark Knight. Together, these 10 films won 14 Oscars. Recent television programs filmed partially or entirely in Chicago include Chicago Fire, Chicago PD, Empire, and the fourth season of Fargo.

Famous Chicago Movie Locations

A beautiful lakefront, Lake Shore Drive, the Loop and “L”, landmark architecture, attractive suburbs, and more offer enticing backdrops for movies and television shows. Here are a few locations you’ll likely recognize if you’re a movie buff who calls Chicago home.

The Dark Knight: Lower Wacker Drive, LaSalle Street

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off: Chicago Board of Trade, Wrigley Field, Art Institute of Chicago

High Fidelity: Wicker Park

Home Alone: Winnetka, Oak Park

My Best Friend’s Wedding: Lake Shore Drive, Comiskey Park, Union Station

Public Enemies: Biograph Theater

The Untouchables: Union Station, Chicago Cultural Center, Blackstone Hotel, Chicago Theater, etc.

In the long tradition of movies and filmmaking in Chicago, ScanCafe is proud to offer film digitizing services in the Windy City. Converting old movies is the best way to preserve celluloid memories for posterity.

The post History of Chicago Film and Movies appeared first on ScanCafe.

via ScanCafe

1 note

·

View note

Photo

"The Bank" 1915

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In the Park" 1915

Sitting beside him, Ernest Van Pelt, he also plays Edna’s father in “A Jitney Elopement” & “The Tramp”.

16 notes

·

View notes