#especially when they called RA per radicals

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Hi, hope you have been having a great day! Your posts have always been my favorite, and they never fail to brighten my morning. I'd say it's the perfect way to start the day for me ^^

Today I have a question! Penny for your thoughts on Law and the Revolutionary Army? What might his stance and opinions about them be, and if he wasn't a pirate, would he consider being in the RA? (since there's little to no chance he would want to become a Marine)

Oh, hi! Now I do have a great day, because I read your ask ❤ Sorry that lately I don't post every day. Sometimes something else steals my attention, like sudden inspiration for a fanfic or some of my friends in need of quality time together :D yesterday it was an impromptu pokemon battle on discord with self-invented pokemons lol. I will take this opportunity to (again <3) thank you so much for enjoying my posts, I'm always so excited to see your reblog tags each time! :D

Law and Revolutionary Army, okay, let's go! *rolls up sleeves* I actually watched some analysis and theory vids about RA before, and I had a lot of my own reflection on them lately, so I already have an opinion about it. At times this might go slightly political, so a fair warning!

First of all, let's start with Dragon and his Revolutionary Army. Thanks to Robin, we know their goal is most likely the World Nobles (Celestial Dragons) and we know they have some longterm goals planned. They're basically gathering supplies, allies, weapons and information, and waiting for a good moment to strike. I don't think their attack on Marie Geoise was one of their ultimate goals in itself, because we learned they did it just to get Kuma back (their valuable ally and friend). Everything else was an extra, but they made sure it counts: destroying the symbol of Celestial Dragons (to declare war), cutting them off the food supplies and getting rid of their stock, freeing as many slaves as they could.

They're apparently still making sure the food supplies can't reach Marie Geoise, which we learned from chapter 1126. Interesting thing to note here is that they actually have an agenda behind "riling up rebellion in nations": it's to limit nations that will pay celestial tribute and hand them resources, in other words: to weaken their enemy.

Dragon declares he literally wants to collect his own army to fight for the better world, whatever that might mean to him. He was part of the marines once, but "found no justice there", so he left and created his own army instead. We can't really talk about Revolutionary Army without taking into account his stance on justice.

Seeing from his reaction to Luffy becoming a pirate ("Not bad!") and him and Akainu disliking each other, we can take some guesses here. Dragon's goals are probably: freedom for people, not allowing innocent people to suffer, making sure people in power do not abuse it (an army for hire sure sounds like a good method to at least make them think twice before overusing their power).

And what's their modus operandi when trying to reach these goals? Many people in fandom are frustrated with Dragon and Revolutionaries, because it feels like they're "just there", waiting all the time and doing nothing. They don't go around the world freeing kingdoms and fighting oppressive reigns, after all. What they do instead, is reach out to normal citizens and "ignite the flame of rebellion" in their hearts.

That's because Revolutionary Army doesn't want to be the ones who will win the war, they want the citizens to be the ones who will win their own country and freedom back, and RA will simply help them achieve that, remaining as support.

They're so interesting exactly because they try to empower those that are on the lowest steps of the hierarchy's ladder, they want to give power back into their hands, but for this to work those citizens have to wish for that themselves, try to fight back, and it needs to be their own decision to do that. The power they give them is the power to fight back, defend themselves and demand their own rights and independence. Revolutionaries show to people that common folk are also part of the system and so they have the right to decide how they want the world to look like, even if it's only in their small kingdom. And those of them that want to join the cause and change the whole world to become a better place, are invited to join the Revolutionary Army. That's how Dragon operates. He even makes it clear that it's his rule not to assassinate kings or overthrow them himself, because that's not his job to do; it's up to the people of the nation.

We can deduce that Dragon would rather avoid direct conflicts, bloodshed and anarchy (after all regular kings are not his aim!). What he offers people in need instead is that: an army for hire, and for free! But only to those powerless people who are oppressed. Now we should ask this question: as much as this all sounds very good and noble, is it really a good thing to do? Let's look at the consequences of the attack on Marie Geoise. It was aimed at Celestial Dragons, but who suffers hunger as the result? The nobles?

No, their slaves and servants instead. They would have to go around hungry because there's no way CD would go around hungry instead (and they make a huge deal that they miss ONE meal a day and snacks). And they're still as spoiled as ever! If anything, this only angered them and nothing more. For now, Revolutionary Army achieved only this: to make the life of slaves in Marie Geoise even worse.

Now let's look at Lulusia. Sabo getting involved with them caused the whole kingdom to vanish from the map (yeah, it wasn't his fault, but the fact this kingdom was before freed by Revolutionaries had influence on Imu's/Gorosei's decision). And then let's look at what they did to help Dressrosa: oh wait, actually, they didn't help much. Yes, they supported ciitizens, helping the injured ones and gathering them in safe places (not that there were any real safe places in Dressrosa's disaster).

They also did research and gather evidence from the underground port Mingo was running, which is interesting. Does it mean RA is gonna present evidence in a court against World Government? Or do they just want to trace back their sources so they can steal it for themselves? Anyway, RA did not fight Donquixotes though and did not fight the Marines, with exception of Sabo (and he got heavily scolded for involving himself in the conflict). Was that really the correct course of action? Is that what heroes should be doing? What would happen to Dressrosa if Luffy lost? Would Revolutionaries just allow everyone to die, despite being right there?

Which points me to my own conclusion: Revolutionary Army has lofty, noble goals, they want to help people who are oppressed, but they're not heroes. And they can't be ones. If you have an army, you're automatically disqualified as a hero, because you fight violence with violence, power with power, no matter how you try to sidestep that fact. I'm not saying Dragon is in the wrong, but... what he kinda yearns for is a form of utopia. People should be encouraged to step up and fight for their own good, they should have the means to do that, but what if what they fight for is a mistaken cause? What if years of resentment will lead the people to just keep on oppressing others as the result? It's a logical conclusion to that: you don't want to be oppressed, be sure to raise to the top so everyone is below you (and now you can opress them back). What if those previously powerless people will start to get back on the class that used to oppress them, like what the common folks did to Homing?

Giving power to common people is great, but it will not erase their hatred they collected for centuries, their rage for all the pain they and their close ones had to experience. If you want the world to be truly a better place, then it needs also education, damn, a collective therapy, besides just manpower in an army. But, you know, it's at least *something*, that's why I'm personally not judging RA. They do what they believe is the best thing to do, a first step in the right direction and they mean well, but I think it will backfire, because it's definitely not enough to overturn the world. And power has a tendency to corrupt.

And then we also have Sabo, who kinda went against Dragon's principles when he accepted to be called a Flame Emperor and used the fake news of King Cobra's assassination to encourage people for rebellion.

This might seem insignificant, but it's anything but: Sabo is part of Revolutionary Army, his actions affect RA's public image. If he didn't deny that he killed King Cobra, then it means killing King Cobra was RA's aim.

We will see how it goes in the future, but the recent "fractions" double spread Oda did (above) foreshadows that Dragon and Sabo will kinda go their seperate ways. Sabo took his stance, he wants to fight, not only watch citizens fight. Even if he did that mostly for Luffy, the consequences of that will be longterm.

Now finally I can switch to the actual question you asked: what would be Law's opinion on Revolutionaries. Remember my analysis on how Law taught Luffy what's "the right thing to do"? It was a lesson to always think of the consequences of your actions, to see the big picture. If you want to liberate a whole nation, you need to choose your battles, to strategize the damage, recognize the oppressor's structure of power and strike down the fillars of it so it collapses on itself. Law is a fighter, a commander, a leader. He will not avoid a fight or a war if that's what needs to be done, he won't leave those people to their own fate and will fight with them for the cause (not just offer support!), and he will do what he can to lead them to victory. And he will never accept credit for it. Officially, it's like he was never there, or just part of a nameless "pirate" crowd, no one important.

But if he can, he will avoid conflict and arrange things in such ways it's not even needed. That's how he wanted to get rid of Doflamingo, simply forcing him to give up his warlord status which meant he would have to leave Dressrosa. Just like that, without any blood spilled. But for achieving that, he doesn't shy from doing things that RA would never approve of: kidnapping people, making ransom demands, forcing people to give up their titles by his own actions. Also Law doesn't rile up any citizens, he leaves that up to others. Dragon would not approve of Law's methods, we can be sure of that. And I think Law wouldn't approve of Dragon's actions over Marie Geoise either (starving off slaves), because Law's MO is to always care about the consequences of the actions. In other words, I think Law would think there are better ways to achieve greater results, without hurting oppressed people even more in the process.

Wait a second, you might ask now, but what about Dressrosa? We get the Wano, but in Dressrosa Law didn't care even for a second about the citizens! Well, actually, I think he did initially, his actions and plan were meant to avoid any harm to them, let's never forget that. Later on he did throw it all out of the window for Luffy's sake, I won't deny that. Law might be hero coded but he's not a hero, at the end of the day, and he knows that, he's not a naive idealist like Dragon is.

Dragon voices no regret about starving the slaves for his cause (at least for now), Law on the other hand seemed to make a guilty face expression at the end of Dressrosa, seeing the injured people and ruins everywhere. And that's actually a good thing, that "reality check" is what keeps Law aware that everything he does and every decision he makes will have consequences, and sometimes you need to choose between lesser evil, because world isn't a pretty place, especially the world in One Piece. And idealism often isn't afraid to kill people for it's cause and not only doesn't call it a wrong thing, but calls it A Right Thing To Do. Remember Death Note? That's your unrestricted idealism 101.

Law might tell the Strawhats to just ignore the assault on one of the Flower Capital's districts, but he will never call it A Right Thing To Do. In fact, when Sanji says he can make it work, Law instead trusts him to do his thing. He's flexible in his ways, he always questions, but when it's needed he's firm in his decisions. He just knows sometimes he isn't doing the right thing, but he never loses the direction he aims towards, because if he always questions and seeks and rethinks it from multiple angles it's always for that purpose: to make sure he isn't on the wrong path and if he is: to change it or do better in the future. And seeing the consequences of Dressrosa and how the waves from that spread over the New World, it actually caused a lot of good changes: wars stopped, underground black market took a huge blow, and in longterm: warlord status got erased. And all of that? Is actually thanks to Law and his plan, that was literally the catalyst here. That's why it's 1:0 for Law when compared to Revolutionaries.

Now we enter speculation territory. I do think Law actually might be supporting what RA is doing. Let's think about it: how did RA know that Dressrosa has an underground port?

We learn they sent agents to Dressrosa before, but "they were all turned into toys" (that's revisioning what actually happened - they wouldn't know anything about the toys, because the existance of their agents would be erased from their memories). And they never answer the question: why Dressrosa? And my answer here is: someone had to give them that intel (anonymous intel, most likely) in the first place. Coincidentally they arrive in Dressrosa exactly when Law's plan is taking the stage. I don't think it points towards Law being a Revolutionary, because Sabo has no reaction towards Law, and Revolutionary army has no reason to hide their identities from each other, that's not how they operate at all. And I don't think Law actually cooperated with them either, because the conclusion after Dressrosa clearly took RA by surprise. They got weapons, they gathered important information, it's like this all was gifted to them by someone. And I think it's likely Law was the one who send them the intel, anonymously, or through someone else. Maybe he does support their goal of declaring a war on World Nobles (even if I think he would be kinda disappointed at some of the results of their actions). We saw at Sabaody already that Law isn't really fond of Celestial Dragons, human auctions and slavery; he was pleased with what Luffy did and he also took a stance by freeing Jean Bart.

Would Law join them in the future? I think he doesn't like to work under anyone. Luffy might be also the only person Law ever worked on equal level with. He acts and behaves like a lone wolf, especially when he says things like this:

That doesn't sound like a person who's on a leash, be it Revolutionary Army's, Navy's or Government's. Being a pirate gives Law freedom. If he's somehow with any of those fractions regardless of my analysis, it's just to use them to reach his own goals, just like he took and discarded his warlord status.

And like I said, I doubt Dragon would like Law's methods so Law would have to change them to be part of the RA (and I doubt the main problem here is that he's a pirate, if he wanted to he could have joined them anyway, they did accept former slaves that were pirates before). Also Dragon is playing the long game, and it feels like Law doesn't have that much time to play along with it, because his plans are always moving fast and cause really big ripples. It's not that he's impatient, but it seems like he can't really afford the slow game here.

As for the question you didn't ask: I actually think Law might be part of the Marines, in some way or form. Let's consider this: if he is aiming to overthrow such a big organization, what's the best way to do that? From the inside. Assuming his hate towards government and marines would stop him is not taking his resolve seriously enough, imo. If he is out for revenge, he will stop at nothing, because he is the last person to carry the memory of what truly happened to Flevance. His own resentments would not stop him, he would do that even if he would end up hating himself as the result. "Everything was for that moment", he could declare at the end of it (just like he does in Dressrosa), when he pushes the final blow from the place the Marines expect it the least: their own most trusted people.

Thankfully though he still didn't lose his heart, that's why he does have at least some brakes intact. That's why he cares for people. That's why he cares for consequences of his own actions. That's why he would throw his own plans away or tuck people dear to him to safety over reaching his goals. But he can never forget those goals or throw them away for good. We will see where his storyline will take him in the end.

Of course that's only considering the somewhat popular theories that Law is a member of Sword. I do think those have some really good observations, but the interpretation part falls flat. They got the dynamics completely backwards imo, because Law would not be an underdog to Drake. There, I said it!

#one piece#trafalgar law#revolutionary army#monkey d dragon#sabo#actually the idea of Revolutionary Army reminds me of the Resistance movement in Akira#especially when they called RA per radicals#I bet this is the inspiration Oda took it from#but imo he made it so much better#I don't even like Akira but I appreciate it's impact and some themes really hit hard#and Oda is a declared Akira fan#ask#one piece theory

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

How Harry Styles Became A Modern Style Icon

by Phoebe Luckhurst - Evening Standard 15/11/19

A man wrought in the fires of teenage boyband hyper-stardom is not afraid of a little commotion. Still when Harry Styles — the One Direction matinée idol turned languid Gen Z icon — tweeted, at 1.01 pm GMT on Wednesday afternoon, that he would be taking his upcoming album Fine Line on tour, you could, if attuned to the correct demographic frequency, hear the howl echo around the internet: guttural, hungry, ululating. This was a pseudo-religious experience: one viral meme depicted the Pope holding a copy of his album aloft. The announcement has been retweeted almost 70,000 times.

The 25-year old is a tour veteran — he spent five years and five albums strapped to the thundering 1D juggernaut — but this new tour is his first as a bona fide solo brand. The album, his first in two years, is synth-soaked and soulful, the album’s aesthetic fever-dreamy. Granted, he’s not the first person to go to SoCal, try a few magic mushrooms and declare himself radically transformed, but the results are beguiling — and certainly a world away from his years as a Simon Cowell Ken doll. Since his last record, he has co- hosted t he Met Gala and been reborn as an Alessandro Michele muse. This is your Styles crib sheet.

Melody maker

Styles’s new album — written under a tie-dye mist after taking the aforementioned psychedelics, which also resulted in a mishap in which he bit off the tip of his tongue — is “all about having sex and feeling sad”, which, granted, as a topline, does not wildly differentiate the record from the genre of “al l other music ever”. Still, the early signs for Fine Line are encouraging. Its first single, Lights Up—which has been streamed almost 100 million times on Spotify —is synth-y, soulful, understatedly anthemic, very different to, and better than, the lead single on his last solo record, the Seventies, soft-rock Sign of the Times( it still, of course, hit No 1), and very, very different from anything he did with 1D. Many thousands of words have been written about whether there is a bisexual subtext to Lights Up. It has been noted that the song was released on National Coming Out Day, that Styles’s sexuality has been subject to frenzied speculation before, the video features an oiled-up, topless Styles gyrating around men and women, and that the lyrics (“Shine, I’m not ever going back/ Shine, step into the light”) could be interpreted as a meaningful revelation of sorts. Certainly, he has become a queer icon — especially with Gen Z — who are thrilled by his selection of genderqueer singer-songwriter King Princess as his support act for the European part of his tour. Speaking of collaborators, Styles worked on the album with producers Tyler Johnson, who has worked with Taylor Swift, Miley Cyrus and Ed Sheeran, and Jeff Bhasker, who has collaborated wit h Mark Ronson and Kanye West, and his friend, Tom Hull, aka Kid Harpoon, who co-wrote Shake It Out for Florence + The Machine. He has also been granted a fairy godmother: Stevie Nicks, who called him her “little muse” at Fleetwood Mac’s hyped Wembley headline gig i n J une. “S he’s a l ways there for you,” Styles has said in the past. “She knows what you need: advice, a little wisdom, a blouse, a shawl.” Sure.

Got Styles

Any young man raised in the white heat of a boyband spotlight must be granted the space to find his fashion path; Styles has done so with no missteps and exuberant pleasure. Once upon a time, he would semaphore his individuality with a bandana; now, he turns up to a cover interview with Rolling Stone in a white floppy hat, blue denim bell-bottoms and Gucci shades, his nails coloured pink and green. His favourite trousers, until he lost them on the beach, were a pair of mustard corduroy flares; this week, he wore a Lanvin sweater vest with a sheep design that sent a coterie of London menswear stylists into throes of ecstasy. He wears floral suits and Cuban heels, ruffled, New Romantic shirts, Charles Jeffrey jumpsuits and pussy- bow blouses. It is flamboyant, self-consciously Bowie/Jagger, and in Gen Z parlance, “very extra”. His stylist Harry Lambert is partial to an extravagant collar, dramatic neckline and a voluminous trouser.

Besides Lambert, another part of this evolution has been his relationship with Gucci’s creative director Michele, who has turned the Italian heritage brand into the ultimate post-gender luxury fashion label, the first to merge their menswear and womenswear, and dispatch male models down the catwalk in dresses and women in suits. A good look for a Gen Z idol.

With the brand

Notably, the branding on this album and its tour artwork is consistent with this new look Styles. The album cover features Styles i n white custom- made Gucci bell bottoms and a Pepto Bismol-pink shirt, open almost to the waist, shot by mod-goth Tim Walker with a fisheye lens (it is Walker’s hand in that S&M glove you can see in the left-hand corner). In the dreamy video for Lights Up he wears a glittery suit and suspenders, in a sort of hallucinatory version of Saturday Night Fever. Into it.

Stand up

Then there’s his voice — not the music, but the activism. Even as one-fifth of a boyband manufactured by Cowell’s algorithm, he was quick, quippy and itching to go off-message; but now that he controls his own, he is amplifying causes such as Black Lives Matter and End Gun Violence. He wore stickers for both on his guitar on his last tour, which might sound small, except that photographs of Styles gallop around the digital world at hyperspeed. At concerts, he has waved pride, bi and trans flags, and a Black Lives Matter flag. He once borrowed a flag from an audience member at a show in Philadelphia that read, “Make America Gay Again”. At a show on his last tour, he declared: “If you are black, if you are white, if you are gay, if you are straight, if you are transgender — whoever you are, whoever you want to be, I support you.”

A vocal, engaged fandom of teenage girls minted his multimillion-pound fortune; he is loyal and admiring of their zeal. “They’re the most honest — especially if you’re talking about teenage girls, but older as well,” he told Rolling Stone this summer. “They have that bullshit detector. We’re so past that dumb outdated narrative of ‘Oh, these people are girls, so they don’t know what they’re talking about.’ They’re the ones who know what they’re talking about. They’re the people who listen obsessively. They f***ing own this shit. They’re running it.” Obviously, he’s a feminist. “Of course men and women should be equal. I don’t want credit for being a feminist. I think the ideals of feminism are pretty straightforward.” An icon is born.

171 notes

·

View notes

Link

Holly Jean Buck | an excerpt adapted from After Geoengineering: Climate Tragedy, Repair, and Restoration | Verso | 2019 | 24 minutes (6,467 words)

December in California at one degree of warming: ash motes float lazily through the afternoon light as distant wildfires rage. This smoky “winter” follows a brutal autumn at one degree of warming: a wayward hurricane roared toward Ireland, while Puerto Rico’s grid, lashed by winds, remains dark. This winter, the stratospheric winds break down. The polar jet splits and warps, shoving cold air into the middle of the United States. Then, summer again: drought grips Europe, forests in Sweden are burning, the Rhine is drying up. And so on.

One degree of warming has already revealed itself to be about more than just elevated temperatures. Wild variability is the new normal. Atmospheric patterns get stuck in place, creating multiweek spells of weather that are out of place. Megafires and extreme events are also the new normal — or the new abnormal, as Jerry Brown, California’s former governor, put it. One degree is more than one unit of measurement. One degree is about the uncanny, and the unfamiliar.

If this is one degree, what will three degrees be like? Four?

At some point — maybe it will be two, or three, or four degrees of warming — people will lose hope in the capacity of current emissions-reduction measures to avert climate upheaval. On one hand, there is a personal threshold at which one loses hope: many of the climate scientists I know are there already. But there ’s also a societal threshold: a turning point, after which the collective discourse of ambition will slip into something else. A shift of narrative. Voices that say, “Let’s be realistic; we’re not going to make it.” Whatever making it means: perhaps limiting warming to 2°C, or 1.5, as the Paris Agreement urged the world to strive for. There will be a moment where “we,” in some kind of implied community, decide that something else must be tried. Where “we” say: Okay, it’s too late. We didn’t try our best, and now we are in that bad future. Then, there will be grappling for something that can be done.

Local Bookstores Amazon

This is the point where it becomes “necessary” to consider the future we didn’t want: solar geoengineering. People will talk about changing how we live, from diet to consumption to transportation; but by then, the geophysics of the system will no longer be on our side. A specter rears its head: the idea of injecting aerosols into the stratosphere to block incoming sunlight. The vision is one of shielding ourselves in a haze of intentional pollution, a security blanket that now seems safer than the alternative. This discussion, while not an absolute given, seems plausible, if not probable, from the vantage point of one degree of warming — especially given that emissions are still rising.

You may have heard something about solar geoengineering. It’s been skulking in the shadows of climate policy for a decade, and haunting science for longer than that, even though it’s still just a rough idea. But it is unlikely you imagined solar geoengineering would be a serious topic of discussion, because it sounds too crazy — change the reflectivity of the earth to send more sunlight back out into space? Indeed, it is a drastic idea.

We are fortunate to have rays of sunlight streaming through space and hitting the atmospheric borders of our planet at a “solar constant” of about 1,360 watts per square meter (W/m2) where the planet is directly facing the sun. This solar constant is our greatest resource; a foundation of life on earth. In fact, it’s not actually so constant — it was named before people were able to measure it from space. The solar constant varies during the year, day to day, even minute to minute. Nevertheless, this incoming solar energy is one of the few things in life we can count on.

Much of this sunlight does not reach the surface; about 30 percent of it gets reflected back into space. So on a clear day when the sun is at its zenith, the solar radiation might reach 1,000 W/m2. But this varies depending on where you are on the globe, on the time of day, on the reflectivity of the surface (ice, desert, forest, ocean, etc.), on the clouds, on the composition of the atmosphere, and so on. Because it’s night half the time, and because the sun is hitting most of the earth at an angle, the average solar radiation around the globe works out to about 180 W/m2 over land. Still, this 180 W/m2 is a bounty.

The point of reciting all these numbers is this: solar geoengineering amounts to an effort to change this math. That’s how a researcher might look at it, anyway.

From one perspective, it sounds like complete lunacy to intentionally mess with something as fundamental as incoming solar radiation. The sun, after all, has been worshipped by cultures around the world: countless prayers uttered to Ra, Helios, Sol, Bel, Surya, Amaterasu, and countless other solar deities throughout the ages. Today, many still celebrate holidays descended from solar worship. And that worship makes sense — without the sun, there would be nothing. Even in late capitalism, we valorize the sun: people search for living spaces with great natural light; they get suntans; they create tourist destinations with marketing based on the sun and bring entire populations to them via aircraft. Changing the way sunlight reaches us and all other life on earth is almost unimaginably drastic.

But there are ways of talking about solar geoengineering that normalize it, that make you forget the thing being discussed is sunlight itself. The most discussed method of solar geoengineering is “stratospheric aerosol injection” — that is, putting particles into the stratosphere, a layer of the atmosphere higher than planes normally fly. These particles would block some fraction of incoming sunlight, perhaps about 1 to 2 percent of it. Stratospheric aerosols would change not only the amount of light coming down, but also the type: the light would be more diffuse, scattering differently. These changes would alter the color of our skies, whitening them to a degree that may or may not be easily perceptible, depending on whether you live in an urban area. The distortion would also affect how plants and phytoplankton operate. Certainly, this type of intervention seems extreme.

And despite the extremity of the idea, it’s not straightforwardly irrational. First of all, solar radiation is already naturally variable; a single passing cloud can change the flux by 25 W/m2. What’s more, solar radiation is unnaturally variable. Global warming is caused by greenhouse gas emissions — the greenhouse gas molecules trap heat, creating an imbalance between the energy coming in and the energy going back out. Since 1750, these emissions have increased the flux another 2.29 W/m2. This disparity between incoming and outgoing energy is what scientists call “radiative forcing” — a measure of imbalance, of forced change, caused by human activity. That imbalance would actually be greater — just over 3 W/m2 — if not for the slight countervailing effect of aerosol emissions that remain close to the ground. Think about a smoggy day. The quality of the light is dimmer. Indeed, air pollution from cars, trucks, and factories on the ground already masks about a degree of warming. Total removal of aerosols — as we’re trying to accomplish, in order to improve air quality and human health — could induce heating of 0.5 to 1.1°C globally.

There will be a moment where ‘we’…say: Okay, it’s too late. We didn’t try our best, and now we are in that bad future.

So, from another perspective, because human activity is already messing with the balance of radiation through both greenhouse gas emissions (warming) and emitting particulate matter from industry and vehicles (cooling), it doesn’t sound as absurd to entertain the idea that another tweak might not be that significant — especially if the counterfactual scenario is extreme climate suffering. If you stretch your imagination, you can picture a future scenario where it could be more outrageous not to talk about this idea.

The question is, are we at the point — let’s call it “the shift” — where it is worth talking about more radical or extreme measures — such as removing carbon from the atmosphere, leaving oil in the ground, social and cultural change, radical adaptation, or even solar geoengineering?

Deciding where the shift — the moment of reckoning, the desperation point — lies is a difficult task, because for every optimist who thinks renewables will save the day, there is a pessimist noting that the storage capacity and electrical grid needed for a true renewable revolution does not even exist as a plan. For many people, it’s hard to tell how desperate to feel: we know we should be worried, but we also imagine the world might slide to safety, show up five minutes to midnight and catch the train to an okay place, with some last-minute luck. It can seem like the dissonance around what’s possible actually increases the closer we get to the crunch point; the event horizon. Some of this uncertainty is indeed grounded in the science. “Climate sensitivity” — the measurement describing how earth would respond to a doubling of greenhouse gas concentrations from preindustrial times — is still unknown. That means we don’t know precisely what impacts a given amount of greenhouse gas emissions will have.

However, basic physics dictates that this season of uncertainty is limited. The picture will become clearer as emissions continue, and as scientists tally up how much carbon is in the atmosphere. Nevertheless, examining the situation today provides useful insights that should be well known, but somehow are rarely discussed in venues other than technical scientific meetings.

At present, human activities emit about 40 gigatons (Gt) of carbon dioxide a year, or 50 Gt of “carbon dioxide equivalent,” a measure that includes other greenhouse gases like methane. (A gigaton is a billion tons.) Since the Industrial Revolution, humans have emitted about 2,200 Gt of CO2. Scientists have estimated that releasing another 1,000 Gt CO2 equivalent during this century would raise temperatures by two degrees Celsius — exceeding the target of the Paris Agreement — meaning that 1,000 Gt CO2 is, if you like, our maximum remaining budget (these are rough figures; it could be much less). Knowing that today roughly 50 Gt of carbon dioxide equivalent is emitted, it is evident that emitters are on track to squander the entire carbon budget within the next 20 years. Moreover, the rate of warming is still increasing. This means that if the rate of warming slows down yet emissions remain at today’s rate, in twenty years, two degrees of warming are essentially guaranteed.

What would it take to avoid this? To keep warming below two degrees, emissions will need to drop dramatically — and even go negative by the end of this century, according to scenarios assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Let’s consider a typical “okay future” scenario; one that would provide for a decent chance of staying within two degrees, like the one represented last year in Science magazine by a graph of median values from 18 “good” scenarios assessed in the IPCC’s 2018 special report on 1.5°C of warming.

First, a typical “good future” scenario has emissions peaking around 2020, and then dropping dramatically. Dramatic emissions reductions are key to any scenario that limits warming.

Second, in an “okay future,” emissions go net negative around 2070. “Net negative” means that the world is sucking up more carbon than it is emitting. How is that done? While emissions can be zeroed via the mitigation measures we’re familiar with — using renewable energy instead of fossil fuels, stopping deforestation, halting the destruction of wetlands, and so on — to push emissions beyond zero and into negative territory requires a greater degree of intervention. There are two main categories of approach: biological methods, including using forests, agricultural systems, and marine environments to store carbon; and geologic methods, which typically employ industrial means to capture and store CO2 underground or in rock. Some approaches combine these, though: for instance, coupling bioenergy with carbon capture and storage.

But here, note a third point: in a “good future” scenario, carbon actually starts to be removed in the 2020s and 2030s, when emissions are still relatively high. Industrial carbon capture and storage (CCS) — the practice of capturing streams of carbon at industrial sites and injecting it into underground wells — is a crucial technique for accomplishing these levels of carbon removal. As of 2019, the world has only around twenty CCS plants in operation, a number that is almost quaint in scale. To begin removing carbon at the level required for a “good future” scenario implies scaling up the current amount of carbon stored by something like a thousandfold. By 2100, the world would be sequestering ten or fifteen gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent. And the scale-up begins right away.

Kickstart your weekend reading by getting the week’s best Longreads delivered to your inbox every Friday afternoon.

Sign up

In the graph of the “okay future” scenario, the gentle slope of declining greenhouse gases looks so neat and calm. It is a fantasy described in clean lines; in the language of numbers, the same language engineers and builders and technocrats speak. This language lends weight to the image, making it seem less fantastic. However, this scenario relies on carbon removal technology at a scale far beyond the demonstration projects being planned today. As the IPCC warned in its special report on 1.5°C, reliance on such technology is a major risk. But the same report indicated that all the pathways analyzed depended upon the removal of between 100 and 1,000 gigatons of carbon in total. In short, limiting warming to 2°C is very difficult without some use of negative emissions technologies — and 1.5°C is virtually unattainable without them.

Does this mean it is impossible to avert two degrees of warming? No. For we know plenty of practices that can be used to remove carbon. We can store it in soils, in building materials and products, in rock. After all, it’s a prevalent element upon which all life is based. It would be difficult to scale these practices under our current economic and political logic, as we’ll explore this book. But it’s technically possible to imagine a future where the excesses of the past (our present) are tucked away, cleaned up, like a stain removed.

*

Geoengineering talk often focuses on one moment — the decision to “deploy,” and how or whether publics will be a part of this decision. But looking at prospective decision points muddies this notion of a discrete decision. It’s also not clear exactly who these “decision makers” are. In much of our conversation about climate action, the citizen becomes a witness to history, to decision ceremonies of the powerful. Out of view are the backstories, the tiny actions that accumulated into a formal decision. It becomes hard to imagine otherwise — that geoengineering could be carried out in conversation with civil society, much less led by us.

Right now, geoengineering doesn’t exist. Indeed, the concept is an awkward catch-all that bears little correspondence with the things it purports to describe. The UK’s Royal Society laid out the term in a 2009 report, which assessed both carbon dioxide removal and solar geoengineering, also known as solar radiation management. (For a deeper understanding of how the concept of “geoengineering” came about, Oliver Morton’s book The Planet Remade and Jack Stilgoe’s book Experiment Earth are excellent resources.) Subsequent policy and scientific research adopted the Royal Society’s framing, though it’s quite possible that in the near future, the marriage of these two approaches will dissolve: a 2019 resolution brought before the United Nations Environment Assembly to assess geoengineering failed in part because it combined such different approaches. My hope is that “geoengineering” is a word that future generations will not recognize — not because they’re living it and it’s become an ordinary background condition, but because it’s a weird artifact of the early twenty-first-century way of seeing the human relationship with the rest of nature. Instead, I want us to contemplate what comes “after geoengineering” in the sense that it extends an invitation to think toward the end goals of geoengineering. “After geoengineering” also aims to evolve the conceptual language we use to apprehend what it means to intentionally change the climate: once “geoengineering” is a retired signifier, how do we understand these practices, and what does the new language and new understanding enable?

Even though climate engineering is mostly imaginary right now, it’s a topic that’s unlikely to disappear until either mitigation is pursued in earnest or the concept of geoengineering is replaced by something better; as long as climate change worsens, the specter is always there. In fact, some of the scarier scenarios result when geoengineering isn’t implemented until the impacts of climate change are even more extreme, and is therefore conducted by governments that are starting to fray and unravel. Looking at these fictional scenarios as they unfold prompts some hard questions about the optimal timing of geoengineering. Climate policy at large has been influenced by a “wait and see” attitude, where policymakers wait and see what kinds of economic damage it will cause before taking action. Research shows that even highly educated adults believe this is a reasonable approach, possibly because their mental models don’t properly apprehend stocks and flows. Climate change is a problem of carbon stocks, not carbon flows: the earth system is like a bathtub, filling up (an analogy used by climate modeler John Sterman and educator Linda Booth Sweeney). Reducing the flow of water into the bathtub isn’t going to fix our problem unless we’re actually draining it, too: the amount of emissions can be reduced, but greenhouse gas concentrations will still be rising. Wait-and-see is actually a recipe for disaster, then, because more water is flowing into the bathtub every year. Carbon removal increases the drain. It doesn’t make sense to wait and see if it’s needed. Moreover, it is possible that our capacity to carry out carbon removal — economically, politically, and socially — could actually be greater now than it will be in a climate-stressed future.

Solar geoengineering is trickier. A wait-and-see approach makes intuitive sense: let’s wait and see if society gets emissions under control in the next couple of decades, and let’s wait and see if scientists can get better estimates of climate sensitivity and sink responses. However, there are two key limitations to note here. First, scientists anticipate that doing the research on solar geoengineering could take at least twenty years, and possibly many decades. Second, we won’t know about some of these climate tipping points until we’ve crossed them. Imagine implementing a solar geoengineering program in order to save coastal megacities from rising seas — a plausible reason a society might try something like this. It would be desirable to do the solar geoengineering before warming reached levels where the sea level rise was locked in. But that year might only be known in hindsight, given that it’s a nonlinear system. For some, this is a rationale for at least starting geoengineering research right away. A counterargument is that research is a slippery slope, and doing the research makes it more likely that solar geoengineering will be deployed.

In much of our conversation about climate action, the citizen becomes a witness to history, to decision ceremonies of the powerful.

Whatever conclusion one arrives at in this debate, the main takeaway, for me, is this: There are certainly scenarios in which global society does figure out how to cut emissions to zero, albeit with much climate suffering (in the near future as well as our current present). Yet, if one thinks it’s plausible that there won’t be a significant start on this in the next decade, and that the risks of climate change are significant, it could be reasonable to look into solar geoengineering. And naturally one would want to avoid the worst-case and go for the better-case ways of doing it. There are crucial choices to be made about how it is done. For most climate engineering techniques, what is outrageous inheres not in the technology, but in the context in which it would be deployed.

Those contexts vary, but they all have two important elements. One is the counterfactual climate change scenario: How bad is climate change turning out to be, on a scale from pretty bad to catastrophic? The second is what is being done at the time to confront climate change, whether that be carbon removal, mitigation, adaptation — or nothing. These are very different futures. If a solar geoengineering program is to be ended on a meaningful timescale, it will rely on mitigation and carbon removal. If a regime begins solar geoengineering, it needs to keep putting those particles up there year after year, until carbon emissions are brought down. Thus, the hard thing isn’t beginning the project, but ending it: ensuring that what comes after geoengineering is livable. This is a battleground that’s currently obscured in most discussions of geoengineering.

The definitive story of the twenty-first century, for people working to combat climate change, may be captured in one graph: the rise of greenhouse gas emissions. The line features a dramatic, tension-laden rise — and, ideally, a peak, followed by a dramatic and then gentle downslope, a resolution that accords a feeling of restoration and completion. From Shakespeare to the novel to the life course, the exposition–conflict–climax–resolution–moral story arc is a classic one. It maps nicely onto a temperature-overshoot scenario, where emissions are temporarily high but come back down. This story line lands us, the challenged yet triumphant protagonist, with 2°C of warming at century’s end. These established narrative forms are how we know how to locate ourselves in an overwhelming situation; how we manage to narrate the task at hand. In these imaginaries of managing an overshoot via carbon removal, we risk simply mapping our familiar narrative form onto the problem.

As philosopher Pak-Hang Wong argues, geoengineering needs to be seen “not as a one-off event but as a temporally extended process.” It’s not about the hero’s moment of action, the climax. I would add that this re-visioning of geoengineering must be directed not just into the future, but into the past as well, thereby placing climate intervention into historical context. Future processes of both solar geoengineering and carbon removal will entail dealing with compensation or insurance for people who suffer loss and damage, working out ways to protect vulnerable people, working out who pays for it — and all that requires a reckoning with history, particularly with colonial histories of land appropriation, dispossession, and exploitation. On the international level, negotiators will have to delve into the histories of uneven development, carbon debt, and, yes, colonialism. Carbon removal can be viewed in terms of debt repayment. The addition of solar geoengineering on top of carbon removal would therefore be like living with the repo man always in the sky above you, reminding you what happens if the debt isn’t paid back. Financially, we are already living in a world of debt peonage, as Marxist geographer David Harvey points out; most of the population has future claims on their labor. Now future generations are going to have a double debt. It’s not just the decision to do geoengineering that matters; it’s how this carbon debt and carbon cleanup operation is taken care of, too. The details are everything.

In reality, the resolution of this narrative curve is going to involve struggles all along the way. The latter part of the work, the last half of the curve towards completion, may be tougher than the first, because decarbonizing the electricity sector by switching to solar panels is simply easier than dealing with “hard to mitigate” sectors or deep cultural changes, like decarbonization of aviation and industrial production, or reduction of meat consumption. Deciding to start geoengineering is a bit like deciding to get married. It’s not saying the vows that is hard, but doing the work of the marriage. “Tying the knot,” in reality, doesn’t actually mean that you’re going to stay together forever, despite the metaphor. You have to keep choosing your spouse, or the marriage deteriorates. Solar geoengineering, in particular, would be more like a relationship than a ceremony: and yet much of the treatment in the literature and the press focuses on the expensive wedding. We should instead be thinking more about the world after geoengineering, because climate engineering could be a means to very different ends.

Indeed, it has been difficult for environmentalists and the left to engage with either carbon removal or solar geoengineering in a forward-thinking way. Part of this is due to a fixation on the immediate need to see emissions peak — but part of it also has to do with some serious limitations in how we think.

Copenhagen, December 2009, 1°C / 34°F

The banners unfurled under the dreary skies read “Hopenhagen.” I crossed the plaza, pigeons scattering. A historic brick building loomed above, its rooftop scaffolding bearing the logo: “i’m loving it.” On the ground floor were a Burger King and KFC. Between this fast-food sandwich hung a three-story advertisement sponsored by “corporate citizens Coca-Cola and Siemens”: two young, blonde boys, skinny and pale, with fists in the air, ready to heft a burden. “Earth’s Bodyguards,” read the caption.

I waited in the cold with hundreds of bundled-up delegates and protestors for a train to the Bella Center, where the fifteenth session of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s Conference of the Parties was taking place. We glided past a glassy office building with a several-story bright-green banner. “Stop climate change. Make COP 15 matter,” it instructed us in Helvetica Light, the logo of construction corporation Skanska beneath.

At the time, climate politics seemed haunted by the specter of green capitalism. We marched under the slogan System Change Not Climate Change. While I have only a few distinct memories of this summit, they portended something quite different than our green capitalist, ecologically modernized future.

Between breaks, delegates would spill out of the conference rooms and rush to treat-laden tables in the hallways in a near melee for the best desserts. A European diplomat in a suit and a young student both reached for the last chocolate on the table, and the man in the suit slapped the confection out of the younger man’s hand.

A retinue of men, dressed in suits, swept briskly through the corridor like a cold wind. The man in the center was the focal point; the rest flanked him, like a military formation. I flattened myself into the side of the hallway as they passed. It’s an unremarkable thing, people passing each other in a nondescript corridor, but I felt chilled. “Did you see Robert Mugabe? He’s here,” someone whispered to me a few minutes later.

A tent, in the rain, in the “free city” of Christiania. I listened to Naomi Klein and other activists muster the forces. We drank mulled wine to keep warm and waited for the police to sweep in with their water cannons and tear gas; there was a rumor that they were coming. (They came.)

There was a kind of power that crackled in the air. Every time it manifested, it surprised me. I was expecting a climate summit to be a rather stuffy and formal affair, filled with acronyms and technical jargon. The injunctions of green capitalism postered around the city seemed pleading, thin, compared to these older and more primal forms of power. Hugo Chávez, speaking at the summit, said that “a ghost is stalking the streets of Copenhagen…it’s capitalism, capitalism is that ghost.” Chavez declared, “When these capitalist gods of carbon burp and belch their dangerous emissions, it’s we, the lesser mortals of the developing sphere who gasp and sink and eventually die.” I can understand the sentiment — particularly when it comes to the unevenness of climate impacts and the brutality of the historical record. As ecological Marxist theory argues, capital accumulation and the treadmill of production is a central factor in global environmental degradation — a thesis I’m onboard with. Nevertheless, I don’t think that green capitalism was the ghost roaming those halls. Perhaps we were focusing on the wrong ghost.

Those of us schooled in keeping watch against green capitalism would naturally read geoengineering as capitalism’s next move in self-preservation. I’m skeptical of this, because I don’t see the evidence that capitalism is capable of acting in its own long-term benefit — especially not consciously, on the scale and temporality of mobilization that this intervention would require. But capital is something of a headless monster, incapable of this kind of macro-level, strategic, long-term thinking. In the face of what could be an existential crisis, innovation is flowing toward hookup apps and making sure porny advertising doesn’t get stationed next to famous brands. This is where capital’s attention and money is directed; as anthropologist David Graeber observes, technological progress since the 1970s has been largely in information technologies, technologies of simulation. Graeber notes that there was a shift from “investment in technologies associated with the possibility of alternative futures to investment in technologies that furthered labor discipline and social control” — in other words, it’s a big mistake to assume capitalism is naturally technologically progressive. In fact, he suggests, “invention and true innovation will not happen within the framework of contemporary corporate capitalism — or, most likely any form of capitalism at all.” I agree — we ’ve seen numerous terrific ideas since the 1970s in alternative energy, and even in carbon removal, but they’ve been constantly thwarted or shelved. Whatever form of capitalism we’re living in now, it doesn’t seem like a system in which carbon removal is going to evolve. The derivation of capitalism we’re coping with is predatory, inelegant, and fragmented, seemingly incapable of delivering fixed-capital tools like carbon capture and storage or transformative bioenergy to extend its lifespan.

Critical theorist McKenzie Wark asks: “We think within a metaphysical construct in which capital has some eternal inner essence, and only its forms of appearance ever change…But what if the whole of capitalism had mutated into something else?” Wark speculates on the emergence of what he calls the “vectoralist” class, a new postcapitalist ruling class that owns and controls the means of producing information: the vectors. This is actually worse than capitalism, Wark argues, because the information vector can render everything on the planet a resource.

If a regime begins solar geoengineering, it needs to keep putting those particles up there year after year, until carbon emissions are brought down. Thus, the hard thing isn’t beginning the project, but ending it.

So what does all this mean for geoengineering? If capitalism is focused on vectoral control and ineffective when it comes to ensuring the material conditions of its own existence, solar geoengineering would be done by states or not at all. As for carbon removal, the question is this: If zombified neoliberal capitalism isn’t going to build up CCS and carbon removal in order to save itself from planetary crisis, who’s going to do it?

We, the workers and voters, will have to decide to force the removal of carbon from the atmosphere. And we should — those of us living in the global North, in particular. A whole host of commonly accepted moral principles align with carbon removal: “clean up your own mess,” “the polluter pays,” the “precautionary principle,” and others. Moreover, doing carbon removal in a socially just and environmentally rigorous manner is not just morally desirable — it is actually a precondition for emissions going net negative.

There are basically two levels to carbon removal, as I see it. Level 1 involves niche, boutique, aesthetic, or symbolic removals. This is the biochar at your farmer’s market, the wool beanie grown with regeneratively grazed sheep, the shoes made with recycled carbon, water carbonated by Coca-Cola with carbon captured directly from the air. It is cool. Advocates see it as the first step toward reaching Level 2. You don’t want to knock its fragile emergence, because it’s important for generating momentum and raising awareness of carbon removal. But it’s geophysically impossible that it will “solve” climate change.

Level 2 is the gigaton-scale removals that could actually lower greenhouse gas concentrations. Call it “climate significant.” It’s waste cleanup; pollution disposal.

How does one get from Level 1 to Level 2? Some people think it will naturally happen, just as cleantech — renewable energy — “naturally” becomes cheaper and scales. But unlike cleantech, Level 2 is a cleanup operation; in general, these scales of storage and disposal don’t generate usable products. I asked Noah Deich, executive director of the nonprofit Carbon180, about these middle-range pathways from demonstration to disposal scales, because his organization has done significant work articulating policy proposals for carbon removal. In the near term, Deich sees a threefold approach, or a “stool with three legs.” One is moonshot research and development across the technology and land sectors. The second is supporting entrepreneurs to bring promising ideas to market. Lastly, he notes, “we need to change policy so that there’s sufficient funding for the research and development, but there are also large-scale markets, so that those entrepreneurs and those land managers can access those markets at a meaningful scale.” The near-term actions he identifies include engagement of universities in research and development, starting up an incubator for carbon tech, and policy work such as implementation of tax credits for CCS and the inclusion of carbon farming in the US farm bill.

When I remarked that the middle time frame seemed fuzzy, Deich replied, “The middle part will remain fuzzy, because I think it’s iterative.” You get started with technology in existing markets, which creates jobs and investment opportunities, he says. Success begets policy support, whether it be government or corporate, which begets more markets, and it becomes a reinforcing cycle that snowballs. “If we’re able to create incentives for taking that carbon out of the air, I think it’s reasonable that we’ll be able to ratchet up those incentives and build that broad political coalition that’s both durable and meaningful to do this at large scale.”

Yet I am less and less convinced that there is a clear route from Level 1 to Level 2, nor that the first would naturally progress to the next. Level 1 is what our current set of policies and incentives can accomplish, with a lot of work from think tanks, NGOs, philanthropists, and the like. Level 2 requires a massive transformation: economic, political, cultural. It implies that we decide to treat carbon dioxide as a waste product and dedicate a significant portion of GDP to cleaning it up, at the least. It would require profound state regulation — the same sort that’s needed for strong mitigation, and then some.

There is sometimes a hope among environmentalists and social justice advocates that confronting climate change will itself bring about social transformation — that it will flip us into a new narrative that could take on the climate pollution challenge. As cultural theorist Claire Colebrook writes,

From Naomi Klein’s claim that climate change is the opportunity finally to triumph over capitalism, to the environmental humanities movement that spurns decades of “textualist” theory in order to regain nature and life, to wise geo-engineers who operate from the imperative that if we are to survive we must act immediately and unilaterally, the end of man has generated a thousand tiny industries of new dawns.

However, I think there are plenty of scenarios where we deal with climate change in a middling way that preserves the existing unequal arrangements, leaving us not with a new dawn, but with a long and torturous afternoon. Replacing our current liquid fuels with synthetic, lower-carbon fuels produced with direct air capture and enhanced oil recovery would be one version. But those dawnless scenarios are not necessarily geoengineering scenarios, and vice versa. There are both horrifying and mildly likeable scenarios for how carbon removal might be accomplished. The horrifying ones are easy to conjure to mind, while the likable ones stretch the imagination. It would be easy to tag best-case carbon removal scenarios as utopias — even though they would actually be worlds that have failed to mitigate in time, representing at best a muddling through. That’s where we’re at: even muddling through looks like an amazing social feat, an orchestration so elaborate and requiring so much luck that people may find it a fantastic, utopian dream.

We can maximize our chances of muddling through by engaging proactively with both carbon removal and solar geoengineering. However, binary thinking about climate engineering has made it difficult for progressives to create a dialogue about how engaging with these emerging approaches might be done. Climate engineering has been stuck in the realm of “technology,” rather than understood as a variety of practices that include people in various relationships with nature and each other. To free ourselves of these binaries and imagine a different kind of strategy-led engagement, it’s valuable to articulate a best-case scenario for how these practices could unfold.

*

There’s an abyss in contemporary thinking about the role of industrial technology in coping with climate change.

On one side of this abyss are people who appraise the potential of technology optimistically, but fail to articulate any real historical awareness of how technology has developed in and through contexts that are often exploitative, unequal, and even violent.

On the other side of the abyss are thinkers who, on the contrary, have a deep understanding of colonialism, imperialism, and the historical evolution of capitalism, but dismiss technology as a useful part of responding to climate change.

This cleavage leaves little room for critical discussion of how technologies might be used to further climate justice. It makes it impossible to imagine, for example, democratically controlled industrial technology that doesn’t exist to “conquer” nature. Today, most left thinking has abandoned the “streak of admiration for the productive forces as the instruments of a conquest of nature that will ultimately usher in communist affluence for everyone,” as human ecologist Andreas Malm has observed. But this abandonment did not immediately lead to a coherent articulation of a view of technology that is collective or cooperative, or that works with nature.

I am not the first to observe this. A number of calls have emerged recently for the left to think differently about industrial technology. Geographer Matthew Huber, for one, suggests that “Marx believed that there is something inherently emancipatory about large-scale industrialization, and ecosocialists need not be so quick to dismiss this possibility.” He asks, “What if the phrase ‘development of the productive forces’ was not simply equated with the expansion of dirty industrial production based on coal, oil, and gas and instead represented the full development of industrial energy systems based on cleaner and renewable fuels?” Sociologist Jesse Goldstein, in Planetary Improvement, his critical ethnographic analysis of cleantech, observes that “the sociotechnical capacity is out there to transform the world in any number of ways,” but realizing emancipatory visions will require “killing the investor” in our minds, “thereby liberating our imaginations, our sciences, and our technologies from the narrowing logic of capital.”

These overlapping binaries — geoengineering versus real change — obscure the reality that there is a spectrum of ways of doing, enacting, practicing, deploying, or implementing climate intervention. The implementation does not inhere in the technology. Sticking rigidly to these binaries keeps us from seeing possible futures: it gives the terrain for shaping climate engineering over to the few.

* * *

From After Geoengineering, by Holly Jean Buck, recently published by Verso.

Holly Jean Buck writes on emerging technologies in the Anthropocene, with work appearing in journals like Development and Change, Climatic Change, Annals of the American Association of Geographers and Hypatia. Since 2009, she has been researching the social dimensions of geoengineering, including as a faculty fellow with the Forum for Climate Engineering Assessment in Washington, DC, as a member of the Steering Committee for the international Climate Engineering Conference in Berlin, and as a doctoral researcher at Cornell University, from which she holds a PhD in development sociology.

Longreads Editor: Dana Snitzky

0 notes

Text

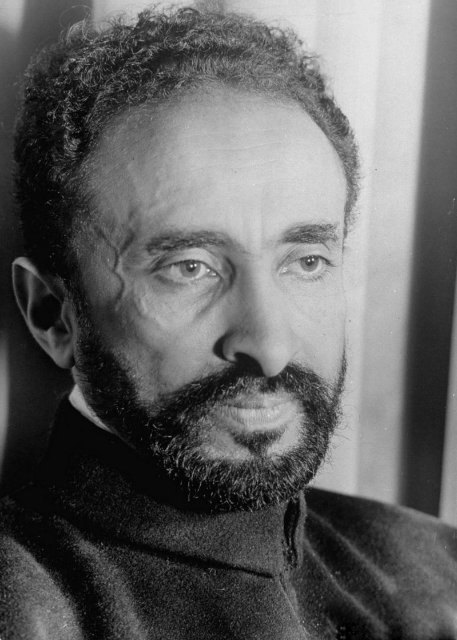

Emperor Menelik II born 17th August.

Lion Judah

Judah, thou art he whom thy brethren shall praise: thy hand shall be in the neck of thine enemies; thy father’s children shall bow down before thee.Judah is a lion’s whelp: from the prey, my son, thou art gone up: he stooped down, he couched as a lion, and as an old lion; who shall rouse him up?The sceptre shall not depart from Judah, nor a lawgiver from between his feet, until Shiloh come; and unto him shall the gathering of the people be.Binding his foal unto the vine, and his ass’s colt unto the choice vine; he washed his garments in wine, and his clothes in the blood of grapes:His eyes shall be red with wine, and his teeth white with milk. Genesis 49:8-12

The colonization of Africa the second ItaloEthiopia war.

These shall make war with the Lamb, and the Lamb shall overcome them: for he is Lord of lords, and King of kings: and they that are with him are called, and chosen, and faithful. Revelation 17:14

Negust Tafari coronation as Emperor Haile Selassie at the Cathedral of Saint George Coronation, His Imperial Majesty’s speech at the League of Nations.

And I saw heaven opened, and behold, a white horse, and He who sat on it is called Faithful and True, and in righteousness He judges and wages war.

His eyes are a flame of fire, and on His head are many diadems; and He has a name written on Him which no one knows except Himself. He is clothed with a robe dipped in blood, and His name is called The Word of God.

And the armies which are in heaven, clothed in fine linen, white and clean, were following Him on white horses.

From His mouth comes a sharp sword, so that with it He may strike down the nations, and He will rule them with a rod of iron; and He treads the wine press of the fierce wrath of God, the Almighty. And on His robe and on His thigh He has a name written, “KING OF KINGS, AND LORD OF LORDS.” Revelation 19:11-16

No man in heaven, nor in earth, neither under the earth able to open the book, loose the seven seals thereof neither to look thereon read it except from the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David.

And I saw in the right hand of him that sat on the throne a book written within and on the backside, sealed with seven seals. And I saw a strong angel proclaiming with a loud voice, Who is worthy to open the book, and to loose the seals thereof? And no man in heaven, nor in earth, neither under the earth, was able to open the book, neither to look thereon. And I wept much, because no man was found worthy to open and to read the book, neither to look thereon. And one of the elders saith unto me, Weep not: behold, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, hath prevailed to open the book, and to loose the seven seals thereof. Revelation 5:5

Description of Isaiah 63

The opening of the seven seals ‘Come and see’.

And I saw when the Lamb opened one of the seals, and I heard, as it were the noise of thunder, one of the four beasts saying, Come and see. And I saw, and behold a white horse: and he that sat on him had a bow; and a crown was given unto him: and he went forth conquering, and to conquer. And when he had opened the second seal, I heard the second beast say, Come and see. And there went out another horse that was red: and power was given to him that sat thereon to take peace from the earth, and that they should kill one another: and there was given unto him a great sword. And when he had opened the third seal, I heard the third beast say, Come and see. And I beheld, and lo a black horse; and he that sat on him had a pair of balances in his hand. And I heard a voice in the midst of the four beasts say, A measure of wheat for a penny, and three measures of barley for a penny; and see thou hurt not the oil and the wine. And when he had opened the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth beast say, Come and see. And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him. And power was given unto them over the fourth part of the earth, to kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth. And when he had opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls of them that were slain for the word of God, and for the testimony which they held: And they cried with a loud voice, saying, How long, O Lord, holy and true, dost thou not judge and avenge our blood on them that dwell on the earth? And white robes were given unto every one of them; and it was said unto them, that they should rest yet for a little season, until their fellowservants also and their brethren, that should be killed as they were, should be fulfilled. And I beheld when he had opened the sixth seal, and, lo, there was a great earthquake; and the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became as blood; And the stars of heaven fell unto the earth, even as a fig tree casteth her untimely figs, when she is shaken of a mighty wind. And the heaven departed as a scroll when it is rolled together; and every mountain and island were moved out of their places. And the kings of the earth, and the great men, and the rich men, and the chief captains, and the mighty men, and every bondman, and every free man, hid themselves in the dens and in the rocks of the mountains; And said to the mountains and rocks, Fall on us, and hide us from the face of him that sitteth on the throne, and from the wrath of the Lamb: For the great day of his wrath is come; and who shall be able to stand? Revelation 7

Ras Tafari in Jamaica.

In 1933 Leonard Percival Howell began to preach about the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie in the parish of Saint Thomas at largely attended meetings accused of ‘Blantant swindle selling pictures at 1s per piece to boost the sale of King RasTafari of Abyssinia son of King Solomon by the Queen of Sheba. Howell held meetings in Trinity Ville and Seaforth of 300 and in 1934 was trailed and sentence for two years sedition and even blasphemy and Robert Hinds ‘his disciple’ led astray by evil doctrine sentenced to one year at the Saint Thomas Circuit Court in Morant Bay by Chief Justice Robert Lyall Grant.

It was around this time that Leonard Percival Howell published the Promised Key under his alias Gong Guru Maragh, of which the front cover of also bore the name of post Nigerian President and Pan Africanist Nnamdi Azikiwe who was the then editor of the African Morning Post in Accra, Gold Coast.

The Promised Key was adapted from Fitz Balintine Pettersburgs Royal Parchment Scroll of Black Supremacy which was published in 1925, other Ras Tafarites such as the house of Nyahbinghi as well as Prince Emmanuel Charles Edwards in his Black Supremacy in Righteousness of Salvation stuck with this tradition of Black Supremacy as well as for using the titles King Alpha and Queen Omega.

meanwhile the second ItaloEthiopia war began over the Italo Ethiopia Treaty of 1928 similiarly to the first ItaloEthiopia war in 1895.

The Italians built a military post on within the border of Ethiopia in 1930 which caused the WalWal incident in 1934.

The members of the League of Nations especially France and Britain failed to comply with Article X of the covenant and did not act to assist Ethiopia under Italian aggression they wanted Italy as an ally against Germany it was Italys plan to make Ethiopia an East African colony along with Eritrea and Italian Somalian.

1935 January Pierre Laval and Benito Mussolini sign the Franco Italian agreement which gave Italy a part of bordering French Somliland (now Djibouti) as part of Eritrea as well as the Aouzou strip in French Chad in Italian Libya.

December Samuel Hoare Pierre Laval Pact was secretly agreed to sign Ogaden Tigray and Southern parts of Ethiopia away to Mussolini when this was found out they were forced to resign.

Stresa Front, Locarno Treaty, Adolf Hitler, Austria Satellite State remilitarization of Rhineland, Anglo German Naval agreement.

July 25 economic sanctions arms embargo was imposed on both Ethiopia and Italy however these were limited in regard to Italy, the United States of America who was not a member of the League exported to Italy.

August 12 Ethiopia also pleads for the embargo to be lifted.

September 2, 1935 - Amy Ashwood and the International African Friends of Ethiopia held a rally in London at Trafalgar Square. Afterwards, Amy posed for a photograph with two of the sons of the Ethiopian Minister Dr. Warqenah Eshete (aka Dr. Charles Martin), Benyam and Yosef (2nd and 3rd from the right). Both sons were Co-Founders of the radical and militant Black Lion Organization that was involved in liberating Ethiopia from Italian occupation and tyranny. Unfortunately, shortly after taking this photo the two were arrested in Ethiopia and summarily executed for the attempted assassination of the Italian Viceroy Marshall Rodolfo Graziani. — at Trafalgar Square.

The Honorable Amy Ashwood Garvey speaks before a London crowd at Trafalgar Square, denouncing the Italian invasion of Ethiopia.“No race has been so noble in forgiving, but now the hour has struck for our complete emancipation. We will not tolerate the invasion of Abyssinia." Mrs. Garvey said: "In this struggle, the black women are marching beside the men. You white people brought us out of Africa to Christianize us and civilize us, but all the Christianity and civilization you gave us for 320 years was slavery. You have talked of 'The White Man's burden.' Now we are carrying yours and standing between you and Fascism." She warned the British Government that if this became a struggle between the "Blacks" and the "Whites" that three quarters of the people of the Empire are colored. Jamaica Gleaner, September 11, 1935.

1936 May His Imperial Majesty boardS the train from Addis Ababa to Djibouti, with the gold of the Ethiopian Central Bank. According to Barker, A. J. (1971). Rape of Ethiopia, 1936. New York: Ballantine Books, Graziani suggested to Mussolini that he have the train bombed which however he didn’t see fit to do so.

The Emperor and hunting party in Ethiopia before the Italian invasion drove him into exile. It was taken on the Addis Ababa to Djibouti railway line in the early 1930s just after he’d been officially crowned as Emperor.

1936 May 4 H.I.M. sails from Djibouti in the British cruiser HMS Enterprise.

May 8 arrives at Haifa.

from Mandatory Palestine sails to Gibraltar on the way to Britain.

May 5th after the fall of Addis Ababa the sanctions are dropped.

Benito Mussolini also used poison gas and mustard gas which were exposed by International Red Cross.

June 7th The Emperor himself addresses the League of Nations in Geneva, Switzerland.

During the Ethiopian Crisis people from all other the world rallied support for the Emperor including The International African Friends of Ethiopia among whos members included Amy Ashwood Garvey, Jomo Kenyatta, C. L. R. James and George Padmore.

Mexico, China, New Zealand, Soviet Union, Republic of Spain, United States USSR also did not recognize Italys occupation.

New York, NY - Scene outside the offices in Harlem of the Pan-African Reconstruction Association, as some of Harlem’s male population studies the banners and posters before signing up for the possible war service in Abyssinia.

-picture-id2660743">

Mussolini and Hilter become allies during the Spanish Civil War, Mussolini declares war on Britain and France attacks British in Egypt Sudan, Kenya, British Somaliland.

1941 May 5th the Emperor returns to Ethiopia with the East African Campaign.

David the Israelite descended from the tribe of Judah and Goliath The Philistine.

And it came to pass as they came, when David was returned from the slaughter of the Philistine, that the women came out of all cities of Israel, singing and dancing, to meet king Saul, with tabrets, with joy, and with instruments of musick. And the women answered one another as they played, and said, Saul hath slain his thousands, and David his ten thousands.1 Samuel 18:6-7