#especially considering the impacts to careers/educations people in other NY schools have had

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I did my presentation on Tatreez and Gauze yesterday at our student research conference. My two biggest. I guess I'd say things in proud of, are the Palestinian woman in the audience who said she really appreciated my work (I'm kinda trying to share more than suffering bc it's dehumanizing). The second is when, after another audience member asked the keynote speaker if there was anything "nonconsequential" we could do to help people in Gaza, I was able to suggest, to the audience at large, to purchase eSims; that they're relatively inexpensive and are a lifeline for people.

I don't think I'm very brave and quite frankly I wanted to cry as I stood there. But it took me less than a minute, and from the people who came to me afterwards to ask for details, I know I made some impact.

You have to try.

#the keynote speaker was presenting the writings of some women trapped in Gaza. a couple of which made reference to the poor telecom service#so the eSim bit maybe made more of an impact bc of that#I'm really grateful my school enables these kinds of conversations#especially considering the impacts to careers/educations people in other NY schools have had#bean speaks#free palestine

1 note

·

View note

Text

Intersectional Feminism In the Classroom

(Photo Source: These Are The Fierce Activists Leading The Women’s March On Washington)

On both January 21st and 22nd of this year, three women organized the country’s largest political demonstration, drawing in nearly half a million Americans to The Women's March on Washington and over 3 million nationally. These women - Linda Sarsour, Tamika Mallory and Carmen Perez – sought to amplify the voices of all those who find themselves at the mercy of patriarchy’s clenched fists. In addition to the typically advertised causes of feminism including reproductive rights and the gender wage gap, protesters rose signs calling attention to police brutality against black bodies, waved rainbow flags in support of LGBT identifying folks, and called out against the Dakota Access Pipeline. This was a demonstration of third wave feminism. This was intersectional. And despite the valid intra-community criticisms against the actual execution of the Women’s March, I ask what we as educators can take away from this major event and how can we bring what we learned into the classroom?

(Photo Source: Do I Have a Place in Your Movement? On Intersectionality at the Women’s March on Washington)

Intersectionality, coined by scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, is “ a concept to describe the ways in which oppressive institutions are interconnected and cannot be examined separately from one another”. All of us hold a multitude of identities that are consistently interacting with one another and with the institutions we come into contact with. I, for example, am a white-passing, Puerto Rican, cis gendered, bisexual, able bodied, middle class raised woman. All these identities have directly and indirectly contributed to the opportunities I have had, the worldview I hold of society and my place in it. Change any one of them, and those very opportunities and perspectives change. Even amongst those who share similar identities, we find diversity. And if we know anything about this country’s history, some identities are privileged over others for no reason other than institutionalized ignorance refusing to retire unearned power. As educators, we participate in what has historically been intended to further the oppression of marginalized people, pacifying youth with white washed, patriarchal narratives that erase the injustices forced against them and the generations before them. And as agents of this system, we are especially obligated to reflect on the power bestowed on us over the development of young minds.

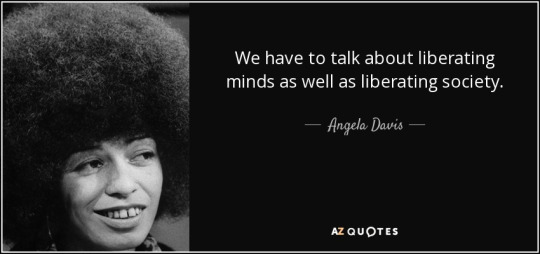

When approached to write this piece, I was prompted with the question: Why is it important for educators to understand what intersectional feminism is? The answer, for me, is simple: because we are responsible for the holistic development of youth that ought to not only be prepared to survive oppressive systems or excel in them, but to dismantle them. White feminism, also known as first wave feminism – a debatable term considering the ideology surrounding equality and equity amongst the sexes is one found well throughout history, not limited to white American women – has never represented the voices of women and non men whose gender identity is compounded by other systems of oppression (i.e., class, race, ability, sexual orientation). It is, therefore, incomplete and inapplicable to classrooms that seek to create a generation of liberated thinkers.

So, what is the first step? We look at the syllabus. Often times when discussing feminism, the target audience is young girls and women (again, by default, typically white). But intersectional feminist thought centers the experiences of all non men, especially marginalized demographics such as women of color and trans women. It must be clear that middle class, cis het, able-bodied white men (and women) cannot be the only people that exist in our curriculums. They are not the only authors who have stories to be told. They are not the only inventors with contributions to be celebrated. They are not the only leaders to write essays about. They are not the only survivors of tyranny with pain that cannot afford to be ignored. Only when we actively and intentionally engage our students in material that reflects these realities, which may or may not reflect that of the students, are we using our position as educators to develop and liberate young minds.

What we teach, however, is not the only line of defense against a white supremacist, patriarchal, academic agenda. How we teach is what separates intention from impact, especially when educating vulnerable populations (i.e., non men of color). Intersectionality is primarily concerned with making visible and audible the narratives of non men typically and systemically ignored. For the past three years, I have served as the program director of the L.A.C.E. Youth Leadership Program, educating low income, inner city Puerto Rican youth grades 6-12. I learned rather quickly that my students are far more knowledgeable about their realities than any college textbook could prepare me for. I learned that my voice was not the most important in the room, that they are aware of what matters to them – and if intersectional feminism teaches us anything, it is that people are the experts on their own lives and it is their voices that ought to speak for their experiences.

But if we are honest, this is not an approach that most students are accustomed to. Educators hold a privileged position over students in that we are the decided expert in the classroom. This can be especially dangerous when educating non men of color, for example, whose voices are often interrupted, undervalued and invalidated. If we are intent on cultivating multiple perspectives, especially within the context of intersectionality, it is vital that educators make an exerted effort to create safe spaces for these students while also allowing for more privileged students (whether that be due to their race or gender) to actively listen to their fellow classmate. Whether that includes house agreements created by the students in the efforts of structuring fair and impactful discussions, or creating seating arrangements that de-emphasize a primary speaker, or encouraging students to make “I” statements so to not speak in generalizations and encourage interpersonal dialogue that builds connections, there are several ways to ensure that all voices are heard and, most importantly, that no marginalized voices are spoken over.

One of the best teaching methods I have found to promote an intersectional agenda – and therefore an agenda rooted in self liberation, equity and community – is to pose students as the teachers. If the goal is to cultivate multiple perspectives within the feminist group, the educators cannot always be the main one talking. I refuse to facilitate every group discussion, especially when the topic is of something that does not directly impact me. In discussions about racism, for example, I - a white passing Boricua woman – would do better to co-facilitate alongside my Afro Boricua female student who is directly impacted by the topic at hand. In addition to cultivating leadership and public speaking skills, both she and her classmates are able to see a young black woman, who not only experiences racism, but sexualized racism at that, at the center of a discussion that has material consequences in her life. In this space, if only in this space, she has the power to structure a conversation about misogynoir amongst a mixed group on her own terms. That is the kind of leadership I want my students to have. That is the kind of feminism I want my students to practice.

I do not see intersectional feminism as some theoretical ideology reserved for dissertations and stimulating conversation amongst the academic elite. It is a tool. One that seeks to personalize the human condition and, if executed properly in the classroom, allows everyone an opportunity to transform what is often a mechanical, academic environment into a space that centers community building amongst youth on the collective desire for self-determination.

MRM Guest Blogger: Roslyn Cecilia Sotero

Roslyn Cecilia Sotero is a graduate of the University of Connecticut with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Human Development and Family Studies. During her undergraduate career, she served as Vice President and President of the Latin American Student Organization (LASO), which provided an array of cultural events and services to students of the Waterbury regional campus.

LASO opened up professional opportunities for Ms. Sotero when she connected with the Hispanic Coalition of Greater Waterbury, Inc. who at the time was looking to create a new youth program. Excited to be working within the local Latinx community, Roslyn drafted a program curriculum that was used as part of a $60,000 state grant application. For the past three years as Program Director of the LACE Youth Leadership Program, Roslyn has catered to the academic, professional, personal and cultural development of youth of color throughout Waterbury's public school system. And as is the vision of the Hispanic Coalition for local youth, Roslyn led the creation of three local art exhibits in CT's first Latinx Art Center, El Centro Cultural, where LACE students took the lead in educating the public about Latinx histories.

In addition to her director position, Roslyn continues to educate Brown and Black communities on social justice issues by serving on several panel discussions across CT, MA and NY specifically in regards to issues close to WOC, education equity, youth-led activism and anti-blackness within Latinx communities.

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

The decision to close the four remaining New York locations effective April 19 highlights the uncertainty facing yoga teachers, especially during the coronavirus pandemic.

On Wednesday, an email from YogaWorks CEO Brian Cooper delivered the news that all four remaining New York locations of this popular yoga studio chain would permanently close effective Sunday, April 19, due to economic challenges.

YogaWorks, founded by teachers Maty Ezraty, Chuck Miller, and Alan Finger, first opened in 1987 in Santa Monica, California, and grew to more than 60 studios across the country. The YogaWorks school combined different styles of yoga, including Iyengar and Ashtanga, helping to create the vinyasa yoga trend and the careers of many of the yoga teachers students seek out today, including Kathryn Budig, Annie Carpenter, and Seane Corn.

See also Master Teacher Maty Ezraty on the State of Yoga Right Now

“As a region, YogaWorks’ New York operations have lost money for several years despite many initiatives to improve studio performance and reduce losses, including closing individual studios, as we have tried desperately to keep New York afloat,” Cooper wrote in the email. “Even after closing Westside and SoHo, the economic realities are clear that there is no path to reduce our losses and get the New York region to break-even.”

YogaWorks has endured substantial fixed costs and intense competition from trendier boutique studios, even as classes everywhere have migrated to online or livestream formats during the coronavirus pandemic. YogaWorks would not be the only studio to point out the financial struggles of operating within the New York yoga market, even well before coronavirus had arrived in the United States and forced studios to close. Jivamukti Yoga, an iconic yoga brand owned by Sharon Gannon and David Life, closed the doors to its last-remaining New York City studio on December 22, 2019.

See also The End of an Era for NYC Yoga

“Our only truly successful studio in New York, Eastside, is now closing as a result of losing our lease,” Cooper writes. “Losing Eastside leaves only three locations, which are each losing money and pushing the region deeper into the red.” In a follow up statement to Yoga Journal, the company said that despite its best efforts, its New York businesses had struggled financially for an extensive period of time. “This is certainly not the outcome we neither wanted nor anticipated, but these considerable obstacles, which were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, have unfortunately made it inevitable,” a YogaWorks spokesperson wrote.

The pandemic also shines a spotlight on the tenuous nature of trying to make a living teaching yoga. Most teachers make hourly wages as contractors, often depending on the popularity of their classes, and piece together a schedule among various studios, private clients, retreats, and workshops and trainings. Most studios do not provide health insurance and other benefits, and under normal circumstances, when you lose a class or job due to a studio closure or schedule change, you can’t apply for unemployment.

Teacher Unionization Efforts Come to a Halt

The shockwave associated with the YogaWorks announcement quickly circulated among teachers, staff, and Unionize Yoga, the first-ever yoga teachers’ union, which formed within YogaWorks NY in September 2019.

Unionize Yoga began just over a year ago in February 2019 as a small initiative among YogaWorks NY teachers who were discussing what job security, health insurance, equity, seniority, and even autonomy could look like for their profession. “We formed our union out of great care for our profession, for each other, and for our students,” reads an email from Unionize Yoga to its supporters in response to the New York closures. “We educated ourselves about our rights as workers. We educated our employer about those rights, too, and our profession has been impacted in important ways.”

Despite initial resistance to unionization, YogaWorks came to respect their teachers’ right to unionize last fall, when they organized under the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAMAW) and subsequently became formally recognized as a union by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Fast-forward to March 2020, just prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Unionize Yoga and YogaWorks conducted their first two rounds of negotiations. And now that studios across the country have closed and more than 17 million Americans have filed for unemployment, there has maybe never been a more pressing time than now to consider the possibility of a yoga teachers’ union. But, as Veronica Perretti, 37, a former YogaWorks teacher and former teacher manager in New York says, “You can’t successfully unionize when a company is losing money.”

See also Teaching Yoga: The Toughest Job You'll Ever Love

For some YogaWorks teachers like Perretti, who was among the minority group that voted against the union last fall, the news of the studio closures, as upsetting as it was to receive, didn’t come as a surprise. As the former NY teacher manager for nearly four years, Perretti says she was aware that the company had been losing money in the region for a while—at least since she held that position before leaving it in 2017.

Perretti told me she thought that unionizing within a company that was operating in the red would be the writing on the wall—and would lead to studio closures. ���I voted no on the union because I thought that was the best way to protect my job; that if teachers unionize it would be a great excuse for YogaWorks to say ‘this region is not profitable and we have to close,’” Perretti said. She says she didn’t speak out about it a year ago because her opinion was an unpopular one.

“There was so much support in the yoga community at large for this idea, and it made me angry that there were people who don’t even work at YogaWorks who were out there promoting it,” she says of the unionization efforts. “So for teachers like me who were against it, it made us feel like we couldn’t speak up—because it could result in us losing our jobs—and in hindsight, I probably should have.”

David DiMaria, 42, a representative of the IAMAW’s Eastern territory and advocate for Unionize Yoga, pointed out that the efforts to unionize didn’t add any costs to the company since they were still in the process of negotiating the first contract. “I would say there were much larger issues at play including the company’s inability to find a replacement location for the Eastside studio once the lease ran out, compounded by the effects of the current pandemic,” he says, adding that if the closure of the New York studios had anything to do with the teachers’ union it would be a violation of federal law. “It’s hard news for all involved, so I don’t want to discount anyone’s feelings—but with all the information we have we just don’t see it.”

As YogaWorks has openly expressed, the company had been struggling financially for quite some time. The Westside location in New York had closed in late-2018, and a source familiar with the downtown Brooklyn location has said that the studio had been struggling for years. By the time the SoHo studio closed in 2019—no doubt YogaWorks NY’s largest, most impressive, and quite likely, most expensive location—the financial strain in the region was mounting. Though a smaller SoHo space remained in its place and potentially saved the company in exorbitant rent costs, it failed to withstand the financial setbacks of COVID-19—particularly when only one out of the four remaining studios in the region, Westchester, was actually profitable. Meanwhile, YogaWorks’ other studios around the country (Los Angeles, Atlanta, Washington DC, et al) will remain fully operational (at least in online streaming format) for the time being.

“We cannot stress enough the levels of gratitude, appreciation and sympathy that we have for all of our New York City teachers and team members, and we thank them for their tireless dedication to YogaWorks and our students,” a spokesperson for YogaWorks said.

Unionize Yoga has been fighting for transparency surrounding studio revenue and financials.

On a group Zoom call late Wednesday night with the union and about 35 YogaWorks teachers, Perretti says that one of the teachers who had voted in favor of the union began to tear up when she expressed the possibility that the studio closures may have had something to do with the decision to unionize. That opinion, Perretti says, was not shared by the rest of the group. Following that call, Jodie Rufty, a senior teacher at YogaWorks for 20 years and the director of trainer development for the NY teacher training staff, sent an email to YogaWorks teachers. “It’s important to acknowledge these closures were eminent and not a result of the union,” she wrote.

What all of this means for the future of Unionize Yoga and for other teachers outside of YogaWorks who may want to form a union remains unclear, particularly in the age of coronavirus and a fast-shifting industry-wide landscape. “I don’t think it’s a great indicator,” Perretti says. “I'm not against unionizing—I'm against unionizing when you’re working for a company that’s already struggling to pay you.” (YogaWorks, an anomaly in the industry, employs its teachers as part-time employees rather than independent contractors, which gave teachers the right to organize as a legally recognized union. The company also offers benefits to employees like sick pay, workers’ compensation, and 401K. Health insurance is offered to full-time teachers who teach the equivalent of 10 classes per week.)

See also Want to Thrive as a Yoga Teacher? 5 Tips from a Yogi Who Cut Through the Competition with Grace

Unionize Yoga has said they plan to continue negotiating and bargaining with YogaWorks to ascertain what rights and concessions they can assert following the closures. But without a company to organize within, how can Unionize Yoga continue? On Friday, Cooper is hosting a virtual “town hall” meeting for all NY teachers on Zoom, which may—or may not—address teachers’ concerns about the union.

“None of us knows what the future will look like, but over the past year we have gotten a glimpse of how vibrant it can be when we all come together in mutual support and collective care,” a Unionize Yoga rep said in an email. “The organizing will continue.”

0 notes

Text

After Years of Financial Struggles, YogaWorks to Permanently Close in New York

The decision to close the four remaining New York locations effective April 19 highlights the uncertainty facing yoga teachers, especially during the coronavirus pandemic.

On Wednesday, an email from YogaWorks CEO Brian Cooper delivered the news that all four remaining New York locations of this popular yoga studio chain would permanently close effective Sunday, April 19, due to economic challenges.

YogaWorks, founded by teachers Maty Ezraty, Chuck Miller, and Alan Finger, first opened in 1987 in Santa Monica, California, and grew to more than 60 studios across the country. The YogaWorks school combined different styles of yoga, including Iyengar and Ashtanga, helping to create the vinyasa yoga trend and the careers of many of the yoga teachers students seek out today, including Kathryn Budig, Annie Carpenter, and Seane Corn.

See also Master Teacher Maty Ezraty on the State of Yoga Right Now

“As a region, YogaWorks’ New York operations have lost money for several years despite many initiatives to improve studio performance and reduce losses, including closing individual studios, as we have tried desperately to keep New York afloat,” Cooper wrote in the email. “Even after closing Westside and SoHo, the economic realities are clear that there is no path to reduce our losses and get the New York region to break-even.”

YogaWorks has endured substantial fixed costs and intense competition from trendier boutique studios, even as classes everywhere have migrated to online or livestream formats during the coronavirus pandemic. YogaWorks would not be the only studio to point out the financial struggles of operating within the New York yoga market, even well before coronavirus had arrived in the United States and forced studios to close. Jivamukti Yoga, an iconic yoga brand owned by Sharon Gannon and David Life, closed the doors to its last-remaining New York City studio on December 22, 2019.

See also The End of an Era for NYC Yoga

“Our only truly successful studio in New York, Eastside, is now closing as a result of losing our lease,” Cooper writes. “Losing Eastside leaves only three locations, which are each losing money and pushing the region deeper into the red.” In a follow up statement to Yoga Journal, the company said that despite its best efforts, its New York businesses had struggled financially for an extensive period of time. “This is certainly not the outcome we neither wanted nor anticipated, but these considerable obstacles, which were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, have unfortunately made it inevitable,” a YogaWorks spokesperson wrote.

The pandemic also shines a spotlight on the tenuous nature of trying to make a living teaching yoga. Most teachers make hourly wages as contractors, often depending on the popularity of their classes, and piece together a schedule among various studios, private clients, retreats, and workshops and trainings. Most studios do not provide health insurance and other benefits, and under normal circumstances, when you lose a class or job due to a studio closure or schedule change, you can’t apply for unemployment.

Teacher Unionization Efforts Come to a Halt

The shockwave associated with the YogaWorks announcement quickly circulated among teachers, staff, and Unionize Yoga, the first-ever yoga teachers’ union, which formed within YogaWorks NY in September 2019.

Unionize Yoga began just over a year ago in February 2019 as a small initiative among YogaWorks NY teachers who were discussing what job security, health insurance, equity, seniority, and even autonomy could look like for their profession. “We formed our union out of great care for our profession, for each other, and for our students,” reads an email from Unionize Yoga to its supporters in response to the New York closures. “We educated ourselves about our rights as workers. We educated our employer about those rights, too, and our profession has been impacted in important ways.”

Despite initial resistance to unionization, YogaWorks came to respect their teachers’ right to unionize last fall, when they organized under the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAMAW) and subsequently became formally recognized as a union by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Fast-forward to March 2020, just prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Unionize Yoga and YogaWorks conducted their first two rounds of negotiations. And now that studios across the country have closed and more than 17 million Americans have filed for unemployment, there has maybe never been a more pressing time than now to consider the possibility of a yoga teachers’ union. But, as Veronica Perretti, 37, a former YogaWorks teacher and former teacher manager in New York says, “You can’t successfully unionize when a company is losing money.”

See also Teaching Yoga: The Toughest Job You'll Ever Love

For some YogaWorks teachers like Perretti, who was among the minority group that voted against the union last fall, the news of the studio closures, as upsetting as it was to receive, didn’t come as a surprise. As the former NY teacher manager for nearly four years, Perretti says she was aware that the company had been losing money in the region for a while—at least since she held that position before leaving it in 2017.

Perretti told me she thought that unionizing within a company that was operating in the red would be the writing on the wall—and would lead to studio closures. “I voted no on the union because I thought that was the best way to protect my job; that if teachers unionize it would be a great excuse for YogaWorks to say ‘this region is not profitable and we have to close,’” Perretti said. She says she didn’t speak out about it a year ago because her opinion was an unpopular one.

“There was so much support in the yoga community at large for this idea, and it made me angry that there were people who don’t even work at YogaWorks who were out there promoting it,” she says of the unionization efforts. “So for teachers like me who were against it, it made us feel like we couldn’t speak up—because it could result in us losing our jobs—and in hindsight, I probably should have.”

David DiMaria, 42, a representative of the IAMAW’s Eastern territory and advocate for Unionize Yoga, pointed out that the efforts to unionize didn’t add any costs to the company since they were still in the process of negotiating the first contract. “I would say there were much larger issues at play including the company’s inability to find a replacement location for the Eastside studio once the lease ran out, compounded by the effects of the current pandemic,” he says, adding that if the closure of the New York studios had anything to do with the teachers’ union it would be a violation of federal law. “It’s hard news for all involved, so I don’t want to discount anyone’s feelings—but with all the information we have we just don’t see it.”

As YogaWorks has openly expressed, the company had been struggling financially for quite some time. The Westside location in New York had closed in late-2018, and a source familiar with the downtown Brooklyn location has said that the studio had been struggling for years. By the time the SoHo studio closed in 2019—no doubt YogaWorks NY’s largest, most impressive, and quite likely, most expensive location—the financial strain in the region was mounting. Though a smaller SoHo space remained in its place and potentially saved the company in exorbitant rent costs, it failed to withstand the financial setbacks of COVID-19—particularly when only one out of the four remaining studios in the region, Westchester, was actually profitable. Meanwhile, YogaWorks’ other studios around the country (Los Angeles, Atlanta, Washington DC, et al) will remain fully operational (at least in online streaming format) for the time being.

“We cannot stress enough the levels of gratitude, appreciation and sympathy that we have for all of our New York City teachers and team members, and we thank them for their tireless dedication to YogaWorks and our students,” a spokesperson for YogaWorks said.

Unionize Yoga has been fighting for transparency surrounding studio revenue and financials.

On a group Zoom call late Wednesday night with the union and about 35 YogaWorks teachers, Perretti says that one of the teachers who had voted in favor of the union began to tear up when she expressed the possibility that the studio closures may have had something to do with the decision to unionize. That opinion, Perretti says, was not shared by the rest of the group. Following that call, Jodie Rufty, a senior teacher at YogaWorks for 20 years and the director of trainer development for the NY teacher training staff, sent an email to YogaWorks teachers. “It’s important to acknowledge these closures were eminent and not a result of the union,” she wrote.

What all of this means for the future of Unionize Yoga and for other teachers outside of YogaWorks who may want to form a union remains unclear, particularly in the age of coronavirus and a fast-shifting industry-wide landscape. “I don’t think it’s a great indicator,” Perretti says. “I'm not against unionizing—I'm against unionizing when you’re working for a company that’s already struggling to pay you.” (YogaWorks, an anomaly in the industry, employs its teachers as part-time employees rather than independent contractors, which gave teachers the right to organize as a legally recognized union. The company also offers benefits to employees like sick pay, workers’ compensation, and 401K. Health insurance is offered to full-time teachers who teach the equivalent of 10 classes per week.)

See also Want to Thrive as a Yoga Teacher? 5 Tips from a Yogi Who Cut Through the Competition with Grace

Unionize Yoga has said they plan to continue negotiating and bargaining with YogaWorks to ascertain what rights and concessions they can assert following the closures. But without a company to organize within, how can Unionize Yoga continue? On Friday, Cooper is hosting a virtual “town hall” meeting for all NY teachers on Zoom, which may—or may not—address teachers’ concerns about the union.

“None of us knows what the future will look like, but over the past year we have gotten a glimpse of how vibrant it can be when we all come together in mutual support and collective care,” a Unionize Yoga rep said in an email. “The organizing will continue.”

0 notes

Link

The decision to close the four remaining New York locations effective April 19 highlights the uncertainty facing yoga teachers, especially during the coronavirus pandemic.

On Wednesday, an email from YogaWorks CEO Brian Cooper delivered the news that all four remaining New York locations of this popular yoga studio chain would permanently close effective Sunday, April 19, due to economic challenges.

YogaWorks, founded by teachers Maty Ezraty, Chuck Miller, and Alan Finger, first opened in 1987 in Santa Monica, California, and grew to more than 60 studios across the country. The YogaWorks school combined different styles of yoga, including Iyengar and Ashtanga, helping to create the vinyasa yoga trend and the careers of many of the yoga teachers students seek out today, including Kathryn Budig, Annie Carpenter, and Seane Corn.

See also Master Teacher Maty Ezraty on the State of Yoga Right Now

“As a region, YogaWorks’ New York operations have lost money for several years despite many initiatives to improve studio performance and reduce losses, including closing individual studios, as we have tried desperately to keep New York afloat,” Cooper wrote in the email. “Even after closing Westside and SoHo, the economic realities are clear that there is no path to reduce our losses and get the New York region to break-even.”

YogaWorks has endured substantial fixed costs and intense competition from trendier boutique studios, even as classes everywhere have migrated to online or livestream formats during the coronavirus pandemic. YogaWorks would not be the only studio to point out the financial struggles of operating within the New York yoga market, even well before coronavirus had arrived in the United States and forced studios to close. Jivamukti Yoga, an iconic yoga brand owned by Sharon Gannon and David Life, closed the doors to its last-remaining New York City studio on December 22, 2019.

See also The End of an Era for NYC Yoga

“Our only truly successful studio in New York, Eastside, is now closing as a result of losing our lease,” Cooper writes. “Losing Eastside leaves only three locations, which are each losing money and pushing the region deeper into the red.” In a follow up statement to Yoga Journal, the company said that despite its best efforts, its New York businesses had struggled financially for an extensive period of time. “This is certainly not the outcome we neither wanted nor anticipated, but these considerable obstacles, which were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, have unfortunately made it inevitable,” a YogaWorks spokesperson wrote.

The pandemic also shines a spotlight on the tenuous nature of trying to make a living teaching yoga. Most teachers make hourly wages as contractors, often depending on the popularity of their classes, and piece together a schedule among various studios, private clients, retreats, and workshops and trainings. Most studios do not provide health insurance and other benefits, and under normal circumstances, when you lose a class or job due to a studio closure or schedule change, you can’t apply for unemployment.

Teacher Unionization Efforts Come to a Halt

The shockwave associated with the YogaWorks announcement quickly circulated among teachers, staff, and Unionize Yoga, the first-ever yoga teachers’ union, which formed within YogaWorks NY in September 2019.

Unionize Yoga began just over a year ago in February 2019 as a small initiative among YogaWorks NY teachers who were discussing what job security, health insurance, equity, seniority, and even autonomy could look like for their profession. “We formed our union out of great care for our profession, for each other, and for our students,” reads an email from Unionize Yoga to its supporters in response to the New York closures. “We educated ourselves about our rights as workers. We educated our employer about those rights, too, and our profession has been impacted in important ways.”

Despite initial resistance to unionization, YogaWorks came to respect their teachers’ right to unionize last fall, when they organized under the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAMAW) and subsequently became formally recognized as a union by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Fast-forward to March 2020, just prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Unionize Yoga and YogaWorks conducted their first two rounds of negotiations. And now that studios across the country have closed and more than 17 million Americans have filed for unemployment, there has maybe never been a more pressing time than now to consider the possibility of a yoga teachers’ union. But, as Veronica Perretti, 37, a former YogaWorks teacher and former teacher manager in New York says, “You can’t successfully unionize when a company is losing money.”

See also Teaching Yoga: The Toughest Job You'll Ever Love

For some YogaWorks teachers like Perretti, who was among the minority group that voted against the union last fall, the news of the studio closures, as upsetting as it was to receive, didn’t come as a surprise. As the former NY teacher manager for nearly four years, Perretti says she was aware that the company had been losing money in the region for a while—at least since she held that position before leaving it in 2017.

Perretti told me she thought that unionizing within a company that was operating in the red would be the writing on the wall—and would lead to studio closures. “I voted no on the union because I thought that was the best way to protect my job; that if teachers unionize it would be a great excuse for YogaWorks to say ‘this region is not profitable and we have to close,’” Perretti said. She says she didn’t speak out about it a year ago because her opinion was an unpopular one.

“There was so much support in the yoga community at large for this idea, and it made me angry that there were people who don’t even work at YogaWorks who were out there promoting it,” she says of the unionization efforts. “So for teachers like me who were against it, it made us feel like we couldn’t speak up—because it could result in us losing our jobs—and in hindsight, I probably should have.”

David DiMaria, 42, a representative of the IAMAW’s Eastern territory and advocate for Unionize Yoga, pointed out that the efforts to unionize didn’t add any costs to the company since they were still in the process of negotiating the first contract. “I would say there were much larger issues at play including the company’s inability to find a replacement location for the Eastside studio once the lease ran out, compounded by the effects of the current pandemic,” he says, adding that if the closure of the New York studios had anything to do with the teachers’ union it would be a violation of federal law. “It’s hard news for all involved, so I don’t want to discount anyone’s feelings—but with all the information we have we just don’t see it.”

As YogaWorks has openly expressed, the company had been struggling financially for quite some time. The Westside location in New York had closed in late-2018, and a source familiar with the downtown Brooklyn location has said that the studio had been struggling for years. By the time the SoHo studio closed in 2019—no doubt YogaWorks NY’s largest, most impressive, and quite likely, most expensive location—the financial strain in the region was mounting. Though a smaller SoHo space remained in its place and potentially saved the company in exorbitant rent costs, it failed to withstand the financial setbacks of COVID-19—particularly when only one out of the four remaining studios in the region, Westchester, was actually profitable. Meanwhile, YogaWorks’ other studios around the country (Los Angeles, Atlanta, Washington DC, et al) will remain fully operational (at least in online streaming format) for the time being.

“We cannot stress enough the levels of gratitude, appreciation and sympathy that we have for all of our New York City teachers and team members, and we thank them for their tireless dedication to YogaWorks and our students,” a spokesperson for YogaWorks said.

Unionize Yoga has been fighting for transparency surrounding studio revenue and financials.

On a group Zoom call late Wednesday night with the union and about 35 YogaWorks teachers, Perretti says that one of the teachers who had voted in favor of the union began to tear up when she expressed the possibility that the studio closures may have had something to do with the decision to unionize. That opinion, Perretti says, was not shared by the rest of the group. Following that call, Jodie Rufty, a senior teacher at YogaWorks for 20 years and the director of trainer development for the NY teacher training staff, sent an email to YogaWorks teachers. “It’s important to acknowledge these closures were eminent and not a result of the union,” she wrote.

What all of this means for the future of Unionize Yoga and for other teachers outside of YogaWorks who may want to form a union remains unclear, particularly in the age of coronavirus and a fast-shifting industry-wide landscape. “I don’t think it’s a great indicator,” Perretti says. “I'm not against unionizing—I'm against unionizing when you’re working for a company that’s already struggling to pay you.” (YogaWorks, an anomaly in the industry, employs its teachers as part-time employees rather than independent contractors, which gave teachers the right to organize as a legally recognized union. The company also offers benefits to employees like sick pay, workers’ compensation, and 401K. Health insurance is offered to full-time teachers who teach the equivalent of 10 classes per week.)

See also Want to Thrive as a Yoga Teacher? 5 Tips from a Yogi Who Cut Through the Competition with Grace

Unionize Yoga has said they plan to continue negotiating and bargaining with YogaWorks to ascertain what rights and concessions they can assert following the closures. But without a company to organize within, how can Unionize Yoga continue? On Friday, Cooper is hosting a virtual “town hall” meeting for all NY teachers on Zoom, which may—or may not—address teachers’ concerns about the union.

“None of us knows what the future will look like, but over the past year we have gotten a glimpse of how vibrant it can be when we all come together in mutual support and collective care,” a Unionize Yoga rep said in an email. “The organizing will continue.”

0 notes