#erín moure

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

erín moure, unfurled and dressy

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

VB: Once, after listening to a text of mine mixing French and English, a first-year US student said reproachfully: “I didn’t understand the parts in French; I felt alienated.” I replied something like: “Relax! It’s okay, and liberating, not to understand sometimes and to realize that reality escapes in the form of languages one doesn’t know.” It’s also humbling to know that myriads of unknown or unidentified languages construct alternative realities. So, yes, there’s a need to reassert that opacité can be generative, totally! On the purely editorial side: Mosadeq pushed us to publish Recovery with some French in it, just like Récupérer had some English. The “tests” were written directly in English. EM: Understanding is vastly overrated! For one thing, it can make us stick with what we already know or “almost know”—that is, what coincides with our prejudices—and where’s the fun in that? I prefer the lostness, the sense of reinventing myself, that comes from reading cacophonically polylingual texts such as Recovery. These texts meet me where I actually “am,” where I am “being.” Can you comment on queer practice and its relation to translation, even within one language? Does being gay/queer/lesbo—as we both and each are—have an attentional effect on writing and language practice that makes verisimilitude already always suspect? VB: Although some say that queerness doesn’t change anything of the writing experience, I think that practicing opacité is in part linked with the experience of not fitting in because I’m gay/queer and often reminded that I don’t belong. Plus, there are things about queer desire—however that absolute singular and the singularity of that desire are antithetical to each other—and queer practices of total exhibition of the self while hiding it that fundamentally change our relation to fidelity, to the shifty contexts of language and languages, and to the way we build new techniques of the body for ourselves. Part of my writing comes from a fundamental need to make cheer because we’ve been and sometimes still are so close to the catastrophic social and mental consequences of being other. We’ve been through the melancholy of refusal, and so the urge is to free oneself from intimidations and intimations. Making cheer means a politics, questioning verisimilitude, finding ways to continue the fluidity that inhabits us, whoever we are.

Vincent Broqua Interviewed by Erín Moure, A book and its translation engage in a “serious lightness” across languages and categories.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

2. Thus seen, i took the temperature of the.

3. Ieri, in the present futuro

4. mijloc

5. Nimeni pe stradă. numai noi.

6. lilas, lilas.

Ring out the hours.

6. liliac: a blind bat holding up the roof of a cave with his blind feet, or an armful of lilacs

5. On the street no one to witness the street into a street. (Where are we?)

4. The middle of the story exposed like a bare belly.

3. Time kept unfolding tomorrow. (When are we?)

2. The word seemed alive: we began to pulse its temperature.

—Oana Avasilichioaei & Erín Moure, from “Living Pr...” (I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women, Les Figues Press, 2012)

#quotations#poetry#conceptual writing#oana avasilichioaei#erín moure#i'll drown my book#currently rereading

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Erín Moure’s Translation of Wilson Bueno’s Paraguayan Sea (Nightboat, 2017) — The Bind

0 notes

Text

Border Lyrics

"...within the playground of the multilingual lyric, which crosses borders with the flick of a code-switch, the hierarchies around gender and nation-states enforced by a monolithic approach to language may be temporarily dismantled."

Subsisters and Paraguayan Sea, two recent SPD titles in translation, reviewed by Henk Rossouw at Boston Review!

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

from Erín Moure’s RETOOLING FOR A FIGURATIVE LIFE (Vallum Chapbook Series No. 32)

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

You had no language.

History had sliced

the beauty of your lips

with a knife from inside.

—Lupe Gómez, Galician poet

translated by Erín Moure

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Each time, time’s rupture must be admitted, for every translation destroys time. This is not “an impossible sentence with no meaning.” It is the time or tense of all translation, all writing. Like the future anterior of the phrase “I died,” all translation appears as a monster in time itself.

Erín Moure, O Resplandor

1 note

·

View note

Quote

In some ways, writing poetry means to attend: to be attentive to everything to do with the senses, every type of traffic, desert, utopia, absence, thought, sensation, music, dream, darkness, love, life. Above all, it means hearing, listening to the other materials that lift a language toward suspension of its servitudes: toward the suspension of its passwords and impositions; suspension of the delusions of an ‘I’, the delusions of communication. The language of the poem has an osmotic relation with muteness, and it might be said that the absence of articulated language is its power, its possibility; this means stretching the ear, heightening the intensity of our attention.

Chus Pato, Always Against the Idols: A Conversation with Chus Pato and Erín Moure

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Torre de Babel 5 - Erin Moure por Emma Villazón

Used by permission of House of Anansi Press (http://houseofanansi.com/products/o-resplandor) and Erín Moure.

EVOCATION

As beautiful as the idea of a shoulder,

the skin of a cup that mirrors the spine,

the spartan stone confesses

stubbornly in the dead limb.

It was not milled oats, it breathed.

It rubbed and pleaded with the sea’s tears

it was serrated and sandy

glad levity inviting the barbarian stranger.

It was beautiful as the shoulder of cattle,

between the grass and flies,

between the light of August as dreamed in April

and, and, it was only the palm of her hand.

EVOCACIÓN

Tan hermosa como la idea de un hombro,

la superficie de una taza que refleja una espalda,

la piedra espartana confiesa

tercamente desde el miembro muerto.

No era avena molida, esto respiraba.

Se frotó e imploró con las lágrimas del mar

estaba serrado y arenoso,

era una feliz levedad invitando al bárbaro extranjero.

Era hermoso como el hombro de un rebaño,

entre el pasto y los mosquitos,

entre la luz de agosto que dormía en abril

y, y, solo era la palma de la mano de ella.

GEOMETRICAL TRANSPORT

No way i stand still.

I’m a hazard.

No way i’m a pond,

i’m a cataract

penetrating the mortiferous mortar,

penetrating the pestilent river,

penetrating the drought’s stars,

penetrating white and dead incredulity

, admitting to stubbornness.

If it were only so easy. I’d be a lighthouse

at the pyramids.

I’d be a pyramid

to the stars.

TRANSPORTE GEOMÉTRICO

De cualquier manera que me quede quieta.

Soy el azar.

De cualquier manera soy un lago,

una catarata

penetrando un letal mortero,

penetrando el río pestilente,

penetrando la sequía de las estrellas,

penetrando la blanca y muerta incredulidad,

admitiendo la porfía.

Si fuera solo así de fácil. Sería un faro

en las pirámides.

Sería una pirámide

en dirección a las estrellas.

SELF-PORTRAIT

I was never as tall as you imagined.

My drop of blood

fell from a word.

AUTORRETRATO

Nunca fui tan alta como imaginaste.

El flujo de mi sangre

caía de una palabra.

SELF-PORTENT

It’s a tall order.

A raspberry crushes my hand

too. Some blood flows out,

some tries to get in.

ASOMBRO PERSONAL

Es una orden elevada.

Una frambuesa se enamora de mi mano

también. Cierta sangre fluye hacia afuera

mientras que otra intenta contenerse.

SELF-PORTRAYAL

I had never felt all visible.

A patch of blood,

a face, a word.

AUTODESCRIPCIÓN

Nunca sentí todo visible.

Una mancha de sangre,

una cara, una palabra.

SELFISH PORTRAIT

A bird in the rowan last winter.

I lowered my eyes

a moment, i was not animal.

The red clutch of berries, and me looking,

my skin pried upward.

I could not face a bird.

RETRATO VANIDOSO

Un pájaro en el serbal el último invierno.

Bajé mis ojos

un momento, no era un animal.

El rojo apretón de las cerezas, y yo mirando,

mi piel reclinada fue hacia arriba.

No pude mirar a un pájaro.

INITIAL ELEGY (two excerpts)

III

It’s not the love of no one

but that no-one had yet penetrated

the air of anyone daring far off

to face fully the air’s possible loveliness.

Air’s loveliness crowns her, and i am made to know

this, though it is something i so rarely know,

unless . . .

IV

Here when i sleep, i conjure her.

Totalities can be inversed totally.

There are gifts so naked i cannot oppose them,

their attachment so fi erce where they do not negate me:

To feel pain in the No, while

facing steadfast forward with a foot in Yes.

Beside her, facing totally steadfast her totality,

the No and the Yes are broken in the air.

So i sleep no more here,

integral and sheer with barbarity

in the face of no harbour but this port.

And how surely barbarity populates me

in the face of her shoulder. Surely as she bares

her shoulder’s face.

If Nietzsche had not looked. I am

the penalty faced with the void.

Better to turn ripening and sleep ––

here, yes,

in the variety of possible landings, sleep ––

my face incipient with cinema

and far off from fi lm,

having never dressed the Nietzschean dawn,

and never wanting more than now to reach out to the comet’s

tail.

ELEGIA INICIAL

III

No se trata del amor de nadie

sino que nadie ha penetrado todavía

el aire de cualquiera atreviéndose lo máximo posible

a encarar enteramente la posible belleza del aire.

La belleza del aire la corona, y yo he sido hecha para saber

esto, aunque es algo que raramente conozco,

a menos que…

IV

Aquí cuando duermo, la conjuro a ella.

Las totalidades pueden invertirse totalmente.

Hay regalos tan desnudos que no puedo oponerme a ellos,

su unión es tan salvaje que no me niegan:

Sentir pena en el No, mientras

se encara firme hacia adelante con un pie en el Sí.

Al lado de ella, encarando totalmente firme su totalidad,

el No y el Sí explotan en el aire.

Así que no duermo más aquí,

íntegra y pura con barbarie

en el rostro sin albergue aunque con un puerto.

Y cuán ciertamente lo bárbaro me puebla

en el gesto de su hombro. Seguramente tal como ella se desnuda

el gesto de su hombro.

Si Nietzsche no lo ha notado. Yo soy

la pena que encara el vacío.

Pero mejor será hacerse madura y dormir—

aquí, sí,

en la diversidad de los posibles aterrizajes, dormir—

mi rostro incipiente con el cine

y muy lejos de un film,

que nunca ha vestido un amanecer nietzscheano

y nunca ha querido más que ahora alcanzar la cola

de un cometa.

SOVEREIGN

My torso is throne for your somnolence

ô you who reign

My word is bread dark to your longing

ô you who reign

My eyes crown you where you

reign

You make my Saturday your Sunday

and oh you reign

The time in which i lie beside you is your gift

in which i’m reined

Your sadness lets me lift the chalk of dawn sky’s

rain

Your far prairie is my mortal grain

ô, you who reign.

SOBERANO

Mi rostro es el trono de tu somnolencia

o tú que reinas

Mi palabra es el pan oscuro de tu ansiedad

o tú que reinas

Mis ojos te coronan donde tú

reinas

Tú haces mi sábado tu domingo

y oh…! tú reinas

El tiempo en el que me inclino al lado tuyo es tu regalo

y en el que caigo bajo tus riendas

Tu tristeza me permite levantar la tiza de la lluvia

del amanecer

Tu lejana pradera es mi trigo mortal

o tú que reinas

Tradução do inglês para o espanhol: Emma Villazón

Erín Moure, poeta canadense, escreve em inglés, francés e galego. Traduziu autores como Andrés Ajens, Nicole Brossard, Chus Pato, Wilson Bueno Rosalía de Castro, Chus Pato e Fernando Pessoa. Os seus livros mais recentes são Kapusta (Anansi, 2015) e Insecession (BookThug, 2014).

0 notes

Text

O título desta intervención debería ser o mellor verso de John Ashbery

Karl Blossfeldt

Para escribir este texto leo por décima, undécima ou duodécima vez o Atlas de Alba. Teño esa sorte. Releo de novo algún poema, percorréndoo por sabe Deus xa que volta. Reléoo co mesmo xesto co que acendo a luz do cuarto, repetido, cotián e non por iso, se o desautomatizásemos, menos asombroso. Releo o Atlas como cando había poucos libros: podería falar do Medievo ou dos meus quince anos, tanto ten (aquela pequena biblioteca de poesía —menos de dez títulos— visitados unha e outra vez, os poucos versos que sei de memoria). Leo o Atlas como a poeta di que os cazadores inuit tallan ósos cuxas formas imitan as liñas da costa. E así, aos poucos, “os símbolos traballan o seu propio desxeo”. Vaia por diante que, mentres falo aquí hoxe e fago balance e cartografía dos poemas de Alba, non renuncio a falar como amigo, convencido como estou de que a amizade e a intelixencia son, co permiso da admirada Estíbaliz Espinosa, neuronas irmás.

Subliño o Atlas de azul e vermello. Cando remato, non podo evitar pensar nunha representación do sistema circulatorio: poemario convertido en manual de anatomía ou libro de texto. Pequenos fíos de veas azuis e arterias vermellas. Un tecido, vasos comunicantes. Nese sentido, a miña primeira tentación é facer de Atlas un despece, un tratado. Hai neste libro cinco ciclos, un polo e un ensaio final. Hai neses cinco ciclos tres historias apócrifas, unha nova denominación das especies, un mapa, unha carta de navegación... Porén, escollo ganduxar, escollo fixarme no fío que terma dos poemas, na voz que os convoca (penso aquí no son indeterminado do metal que golpeamos, no eco, no canón do Sil, no rastro da vea que aparece e marcha sobre a carne branquísima de quen se debruza día e noite no scriptorium). Falar da voz é falar do límite, non como término, senón como transgresión. Leo en Agamben: “O único contido da revelación é o en si pechado, o velado: a luz non é senón o porvir da escuridade en sí mesma”. Neste sentido, Alba escolle unha voz mesta con puntos de luz, un caudal que se vai cargando de materiais e que brilla baixo o sol do mediodía ou a lúa chea: nenas con bengalas nunha praia en Provincetown (así as fotografou Robert Frank e así mas fixo chegar Alba o pasado outubro).

Digo nenas e penso que quen fala é a miúdo a “pequena occidental” do primeiro poema (na paxinación e no tempo) deste libro: “Historia apócrifa dos tulipáns ou as alucinacións nos Países Baixos”. Unha nena que viaxa, que medra, aprende, retruca, inventa e nunca, nunca, nunca deixa de confiar na maxia. Neste sentido, Alba é digna herdeira da Penélope soñada por Xohana Torres, da súa liberdade. E éo tamén —herdeira— pola súa posición no campo literario. Permitiredes que afirme que nunca unha estrea editorial foi tan agardada coma esta, que poucas veces unha poeta inédita (aínda que na esteira de ata que punto pode ser inédita unha poeta na era de internet habería moito que dicir), pero poucas veces unha poeta inédita acadou tal nivel de influencia nas súas coetáneas e tan boa acollida dentro e fóra das nosas fronteiras. Penso, neste sentido, na curiosidade que os poemas de Alba espertan en tradutoras como Erín Moure ou Harriet Cook, no recoñecemento para a tradución ao inglés da “Historia apócrifa do descubrimento das migracións”, da man de Jacob Rogers, que se converteu no primeiro poema galego en abrir a sección “Poem-a-Day” da web da prestixiosa Academy of American Poets. Pero é que ademais, Alba é posiblemente a mellor crítica literaria da súa xeración, da miña xeración (tanto por escrito como nas ondas da Radio Galega); é unha das académicas que mellor ten pensado o suxeito poético en Galicia; unha das articulistas máis singulares (dende o seu “Gabinete de curiosidades” en Tempos Novos ata a serie “An octopus” na revista Cactus); e tamén unha das poetas máis difíciles de fixar, de situar, de clasificar. Esa manía que tanto parecía volver estilarse por estes lares hai dous ou tres anos e que, afortunadamente, foi esquecida xa.

Pero regresemos sobre o libro. Sobre o meu exemplar de Atlas e os seus subliñados en azul e vermello, a súa anatomía. Aparece entón de novo a pequena occidental receptora de historias, falando e rindo en múltiples linguas e linguaxes. Emerxe tamén a nena que rilla nunha mazá a carón dos cantís de Calais. E eu pregúntome se as dúas son a mesma nena ou só quedan para xogar. Para xogar ás Polly Pocket ou ao voleibol coas rapazas das montañas Karakorum. Porque hai nestes poemas unha vontade de xogo, de transparentar materiais, idiomas, expresións artísticas. Unha vontade por veces científica, académica, e, outras, puramente fantasiosa, imposible (como a mellor ciencia teórica). Direi tamén, se son fiel á miña relectura última, que o Atlas está non só cheo de límites rotos e dobres costuras, senón que o habitan tamén seres en constante cambio: adultos pel-de-cedro, homes-teixo, avoas cuxo xesto imita o da caléndula, Safo transmutada en cigarra que cae, ou os Asmat, ese tribo de Papúa Occidental que se autodenomina a xente das árbores. Eles poderiamos ser nós, lectoras. Neste sentido a transgresión, o que a voz dos poemas imaxina, non se detén no cruce e no tratamento de referencias históricas ou xeográficas, senón que o modifica todo, mesmo o propio libro, que devén dragón atrapado entre dúas eclipses. Dragón feito de escrita. Voz de dragón.

“intuir o bosque na dispersión das sementes”, dise. Penso entón na lectura, nas bibliotecas. En como a lectura nos interrompe e nos tranforma. Sáennos ao camiño no Atlas, explícitamente: Marianne Moore, Gertrude Stein, Anne Carson, Charles Dickens, Paul Celan, Ezra Pound, Claudio Rodríguez, Juan Andrés García Román, Charles Wright, Wallace Stevens, John Ashbery, Edgar Allan Poe, Jorie Graham, D. H. Lawrence. Todas elas, as febras do tapiz, a dama e mais o unicornio. Fago para vós a miña pequena escolla de flores. Dúas mestras recoñecidas na dedicatoria, certo parentesco, unha liñaxe. De Marianne Moore, a técnica, a intención, a vontade firme de escribir allea a todo, a independencia da muller que pensa o mundo mesmo se o mundo non pensa coma ela ou nin sequera pensa nela. De Anne Carson, a voz que un día foi, o fragmento, o ano en que lemos Homes nas súas horas libres, pero sobre todas as cousas a liberdade. Despois recoñezo a fascinación pola imaxe, polo torrente, velaí Jorie Graham, lida nunha biblioteca dun país estranxeiro. Era verán, escribiámonos, coma sempre, por messenger. Velaí La adoración de García Román ou, ocórreseme agora, aquela Julieta Valero que cantaba á anatomía dos príncipes escandinavos en Los heridos graves. Aí están, parellas, fascinantes, herdeiras desta alucinación luminosa, as mozas de Alba: “dúas rapazas que choraban diante dos espellos e usaban vaqueiros máis celestes / ca os seus iris” ou “as adolescentes do baño cruzaron a sala, recordo, / proxectando fugazmente a escena dunha marisma / cos reflexos dos seus cabelos rosa flamengo”. Está tamén, na lectura destes poemas, na dicción e no risco, a Chus Pato que escribe: “pregúntome se nesta frase caben todos os teixos da cidade libre de París” —París!— ou aqueloutra maís rebuldeira de m-Tala. E está, por suposto, Francisco Cortegoso, o contemporáneo co que mellor dialoga a poesía de Alba. Está en homenaxe (brillo de escama, reflexo celeste, columna vertebral), pero tamén antes de marchar, véxase o parentesco destes versos de Alba onde o pai “sabe despegar a sombra / do corpo / dos paxaros”, con aqueloutros de Cortegoso onde a árbore “Distánciase na altura, mídese / na sombra. // Sostena / o ceo. / Pode caer”. E eu digo: caemos. Imaxino unha santa en cuxa cabeza se abre un libro. Podería ser unha santa ou unha dama habitando a cidade de Christine de Pizan ou un cadro de Remedios Varo. Repito unha vez máis, no Atlas, tan libre, tanto ten. Digo santa ou dama e tanto ten porque Carson lembraríanos que todas elas son incómodas interrupcións no curso da historia. Ese poder outorgámosllo á lectura, ao verso, ao lugar onde todo encaixa e rompe. Onde é posible dicir: todo encaixa e rompe.

Por último, os “Ensaios”. Os ensaios de Alba coma unha sorte de poética. Notas a pé de páxina, a pé de ollo. Os ensaios en aberto, en Instagram, escritorio desordenado, colección de mostras. Penso que este libro se comezou a escribir daquela —2013— cando nos coñecemos e Alba investigaba sobre o poema en prosa, sobre a presenza do ensaio no poema. Lembro a primeira vez que a escoitei recitar, o poema contiña a humidade dos manglares. Despois, lembro ler con fascinación, “O corpo e as bestas”, unha serie da que permanecen vestixios no “Tríptico” ao xeito de Millet que contén este Atlas. Despois, Capadocia. Despois, os tulipáns. Ao final do ensaio sobre a Canna indica Karl Blossfleldt di, tras aparcar a un lado a bicicleta: “Se lle dou a calquera unha equisetácea, non terá problema ningún en facer un aumento fotográfico —todo o mundo pode—. Pero observala, prestarlle atención e descubrir as súas formas, iso, iso é un cantar distinto”. Nese cantar, na súa precisión, afina este libro.

Comezaba dicindo que o título desta intervención debería ser o mellor verso de John Ashbery, poeta querido pola autora e por quen fala. Esa é unha débeda que teño con Alba. Esa era a miña intención hoxe, estar á altura do Atlas, buscar palabras que o iluminen. Non atopei, por desgraza, ese único verso Ashbery. O que diga toda a miña admiración, todo o amor, toda a amizade. O único que agardo, e permítanme o extraliterario, é que a conversa onde busquemos ese verso dure todo o tempo do mundo.

[Este texto foi lido na primeira presentación de Atlas de Alba Cid, o 18 de decembro de 2019 na Libraría Couceiro de Santiago de Compostela]

1 note

·

View note

Quote

One intriguing aspect of Pillage Laud, a book of poems supposedly “written by a computer” (back cover), is that “Erín Moure,” the so-called “biological product in the usual state of flux” (109), not to mention in big scare quotes, is not alone in her little writer’s garret dreaming up these sexy mechanized cantigas for her lesbian lover. She has cohorts in the production, co-authors, you might say, one being the sentence-generator program MacProse, and the other being MacProse’s monster-father-programmer, Charles O. Hartman. We also can’t forget Pillage Laud’s originally accented “Erin Mouré” from 1999, and probably the other E(i)r(í)ns too, with or without scary quotes and accents, and, who knows, maybe even Elisa Sampedrín in utero.[iii] Truly a distributed cybernetic network is this pillaged laud to plugs, bottoms, whips, wanks, vaginas, and harnesses, a “powerful infidel heteroglossia,” as Donna Haraway, one of Erín’s continuous muses, would say in her infamous “A Cyborg Manifesto” (181). Or “I was a front” and “We are my veils,” as Pillage Laud would say (32, 14). Or, as perhaps only my friend Erín would get the engine to say, “My identity had grinned”

“Like plugging into an electric circuit”: Fingering out Erín Moure’s lesbo-digit-O! smut poems

0 notes

Text

Weekly Wrap Up

Tabletop & video-games:

Control, PS4.

Manga, manhwa, graphic novels, comic-strips, fic & books:

Furia do Corpo, João Gilberto Noll.

Erín Moure’s Translation of Wilson Bueno’s Paraguayan Sea (Nightboat, 2017) — The Bind

William Friedkin Unrealized Projects – IndieWire

Podcasts, playlists, JAMS, EPs & albuns:

[Caioverso] CAIOVERSO #117 - Anime Véio: Rayearth #caioverso

[Super Amibos] LIVE - Star Trek: Strange New Worlds (Episódios S02E06, S02E07 e S02E08) #superAmibos

[AoQuadrado²] Re:En² - Eden: it's an Endless World Vol. 05-08 #aoquadrado

TVshows, TVseries & movies:

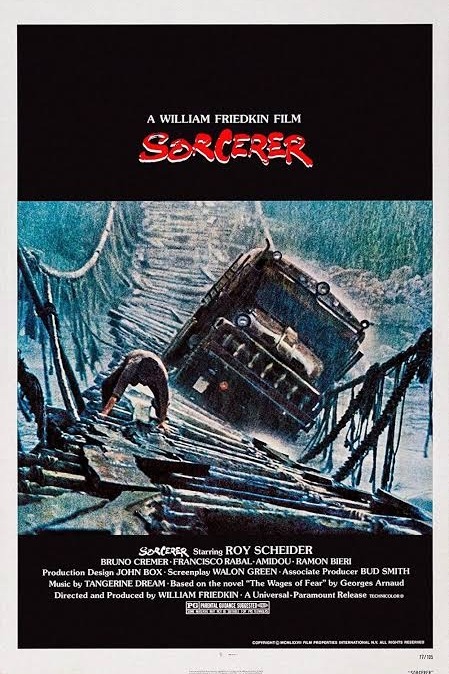

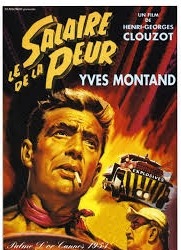

Filhas do fogo (1978)/ Sorcerer (1977) /The wages of fear (1953)

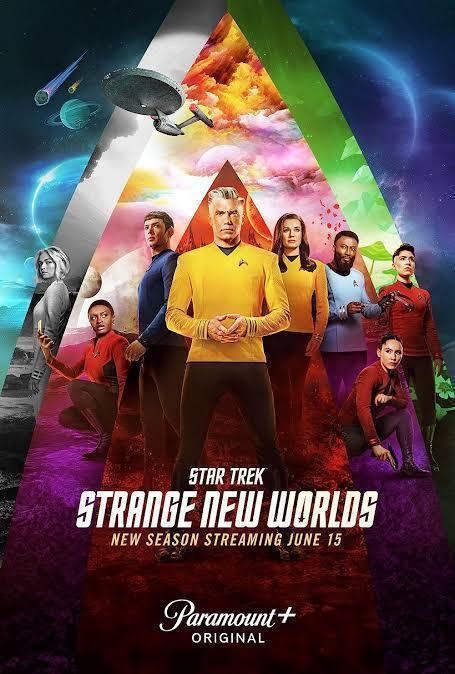

Star Trek: Strange New Worlds s2e6-10/ Kochikame s2e3,4 / Galaxy Express 999 s1e2-4

0 notes

Text

8 DEMANDS THAT WE MAKE OF SPD OPERATIONS DIRECTOR BRENT CUNNINGHAM: ILLUSTRATED IN SPD BOOKS

IN THIS WEEK’S SPDCLICKHOLE by Steve Orth, Ari Banias & Trisha Low

Dear Reader, you might know a lot about SPD, but it's likely that you don't know much about our Operations Director, Brent Cunningham. Some fun things about Brent.

1) He's very tall and large-so tall and large that just encountering him recently made a small child burst into tears.

2) He is remarkably efficient. So efficient that he often takes care of tons of SPD business silently in his office without a lunch break or even any kind of tiny complaint.

3) When he does eat lunch, he eats a lot of kidney beans from a can poured directly onto salad because this saves TIME while providing ENERGY.

4) He has a really cool post-it note holder on his desk in the shape of a green dinosaur.

And when he's not doing all that, Brent is dealing with a very fussy, finicky staff full of, as they say 'artistic temperament.' In other words, Brent has to deal with a bunch of workers who are constantly coming up with new and increasingly complicated demands that he, as Operations Director, is obligated to deal with. We have a lot of pity for Brent for being in this position. We do. But we also have a lot of love. And so, since this month's #SPDhandpicked theme is DEMANDS - we've come up with 8 SPD books to help you understand the DEMANDS that us SPD staffers place on long-suffering Operations Director Brent Cunningham - but also to celebrate him. THANKS BRENT!

1. An Anthology of Modern Greek Poetry ed. Nanos Valaoritis and Thanasis Maskaleris (Talisman House)

Today, I asked Brent a question about the Microsoft Excel thing, instead of answering my question directly, he told me about Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, inventor, and astronomer Archimedes. Did you know that Archimedes created a thing The Claw of Archimedes, which, I guess was this big claw that was supposed to pick up and remove war ships during sea battles? Brent knew. And then I was suddenly able to conquer my Microsoft Excel myself.

2. A Mystery's No Problem by Lou Rowan (Equus Press)

Work is a real mystery to me. You show up to some place that is not your home and someone is supposed to tell you what to do and then you're supposed to do it. What? What a ridiculous concept? Why are we even doing this? It's a mystery. And when I express these concerns to Brent, he is able to solve this riddle. He's like "uh we're trying to sell poetry books because they're awesome. And you need to pay your rent." And I'm like, "oh, okay. That makes sense." 3. Sign You Were Mistaken by Seth Landman (Factory Hollow Press)

I don't usually make mistakes at work. But when I (very rarely) do. Brent doesn't scold me. He doesn't chastise me. He shows me the error of my ways and how moving forward how can make sure I am making the correct decisions. And then locks me in the broom closet overnight, so I can get a real sense of how my mistake has affected Small Press Distribution. Sometimes spending a night in the box is just what the doctor ordered. JK about the broom closet!

4. Riddles, Etc. by Geoffrey Hilsabeck (The Song Cave) Do you know how many post-its we go through here at SPD? So. Many. We don't really use notebooks, just these loose little colored squares that we scribble full of order numbers, names, phone numbers, everything. Sometimes, you'll find these totally illegible post-its on your desk telling you you're supposed to do something that you can't even read. Anyway. I joked once that we would just get post-its with all in caps, JUST ASK BRENT printed in them. Which honestly, is the answer to any SPD riddle anyway. Brent can solve the problem. 5. My Dinosaur by Francois Turcot, trans. Erín Moure (BookThug) Brent might have a dinosaur-shaped post-it holder on his desk, but the truth is his life is full of real dinosaurs. The chaos here at SPD is basically just Jurassic Park. From Trisha, the Publicity Manager, who stomps into his office demanding money to buy new ads, to warehouse associates and interns who require guidance with minute tasks, to the staff who collectively yell 'BRENT' any time there's a problem with the internet, the dinosaurs are real. But the true little dinosaurs in his life are the two adorable children who he will often drop everything for - from pick ups from karate class to emergency runs to Target, only Brent can keep the velociraptors at bay. 6. Gates & Fields by Jennifer Firestone (belladonna*) Because SPD is full of super rare and valuable items that any one might want to break in and steal - poetry books - its very important that we have an adequate security system. Brent is in charge of this security system, but it is extremely troublesome because it involves someone arming the alarm before we all leave for the day. But here is the thing: we not only demand that Brent be charge of teaching us all how to arm the alarm, but also locking the gate and being the contact person for whatever happens if someone gets in and sets off the alarm and steals all the books and the computers, um, basically we demand that Brent is responsible for all our security. And also that our first line of defense after the doors and the gates is Brent, armed with a mini-golf club. Sorry Brent. It's on you.

7. Responsive Listening: Theater Training for Contemporary Spaces, ed. Camilla Eeg-Tverbakk and Karmenlara Ely (Brooklyn Arts Press)

Some of us are well versed in listening. Others, not so much. To listen truly responsively though is a rare gift. Brent's office sits on the opposite side of the SPD kitchen, but he can somehow hear us muttering over here. And when he offers answers to pressing questions we ourselves haven't yet found language for -- in a booming, yet reassuring voice, as if from the firmament -- what else would you have us call this but "responsive listening"?

8. A Piece of Work by Annie Dorsen (Ugly Duckling Presse)

Actually it's uncommon that any of us ask Brent for more work. 9. Handholding: 5 kinds by Tracie Morris (Kore Press)

To suggest Brent might only provide five kinds of handholding would be like saying there are only five kinds of sandwiches in the world. What an insult that would be to the abundant variety of handholding that we, the SPD staff, demand of Brent. We haven't yet demanded sandwiches but it could happen.

All #SPDhandpicked books on DEMANDS are 20% off all month w/ code HANDPICKED

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

EXCERPT from Introduction:

Some may ask: Why poetry? Why respond in a kind of language where meaning is not always transparent, when the subject matter of sexual abuse might rather invite language that states categorically the terms of the experience, that does not allow for misinterpretation or ambiguity? Shouldn’t this be language that gets straight to the point rather than travelling slant, arriving wonky or misshapen? But, we ask, whose point would that language be arriving at? If it wasn’t women who shaped the vocabulary and syntax we widely recognize as legible, then following these forms could, for some, feel like another act of docility.

–Emily Critchley and Elizabeth-Jane Burnett, 2018

One of my poems:

MISSISSIPPI

Last night at a Love’s truck stop, a man told me he would like to slice me up, boil and eat my liver and rape me after, I’m pretty sure, in that order. With his eyes he spoke those words, and if you don’t believe me (“How could you know for sure?”) then you’ve never been a woman, or else. The rain and the cows don’t care. The corn doesn’t ask or doubt. And there’s a southern sadness buried in everything I pass down this dark road driving tonight.

–Amy King

CONTRIBUTORS:

KAT ADDIS

SASCHA AURORA AKHTAR

RACHAEL ALLEN

NUAR ALSADIR

RAE ARMANTROUT

MEI-MEI BERSSENBRUGGE

ZOË BRIGLEY THOMPSON

ELIZABETH-JANE BURNETT

MAIRÉAD BYRNE

J.R. CARPENTER

SOPHIE COLLINS

JENNIFER COOKE

EMILY CRITCHLEY

ALISON CROGGON

AMY CUTLER

JEAN DAY

CARRIE ETTER

AMY EVANS

MEGAN FERNANDES

KAI FIERLE-HEDRICK

HEATHER FULLER

ISABEL GALLEYMORE

SUSANA GARDNER

SUSAN GEVIRTZ

ELIZABETH GUTHRIE

SARAH HAYDEN

SUSAN HOWE

JACQUELINE KARI

AMY KING

DEIRDRE KOVAC

LOUISE LANDES LEVI

AGNES LEHOCZKY

JAZMINE LINKLATER

FRANCESCA LISETTE

SO MAYER

CAROL MIRAKOVE

KATHRYN MOCKLER

MARIANNE MORRIS

ERÍN MOURE

CHARLOTTE NEWMAN

SANDEEP PARMAR

FRANCES PRESLEY

JÈSSICA PUJOL DURAN

SINA QUEYRAS

NAT RAHA

NISHA RAMAYYA

JOAN RETALLACK

CHRISTIE ANN REYNOLDS

SUSAN M. SCHULTZ

CONNIE SCOZZARO

SOPHIE SEITA

ZOË SKOULDING

ROSIE ŠNAJDR

VERITY SPOTT

REBECCA TAMÁS

ELIZABETH TREADWELL

CATHERINE WAGNER

ROSMARIE WALDROP

SAMANTHA WALTON

CAROL WATTS

EMILIA WEBER

ELIZABETH WILLIS

SARA WINTZ

ELISABETH WORKMAN

0 notes